User login

Transgender women on HT have lower bone density, more fat mass than men

CHICAGO – according to findings from a recent Brazilian study.

“Lumbar spine density was lower than in reference men but similar to that of reference women,” said Tayane Muniz Fighera, MD, speaking at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Lower lumbar spine density in transgender women was associated with lower appendicular lean mass and higher total fat mass, with correlation coefficients of 0.327 and 0.334, respectively (P = .0001 for both).

Dr. Fighera and her colleagues looked at the independent contribution of age, estradiol level, appendicular lean mass, and fat mass to bone mineral density (BMD) in the transgender patients, using linear regression analysis. Total fat mass and appendicular lean mass were both independent predictors of bone mineral density (P = .001 and P = .022, respectively). For femur BMD, age, and total fat mass were predictors (P = .001 and P = .000, respectively).

The study aimed to assess bone mineral density as well as other aspects of body composition within a cohort of transgender women initiating hormone therapy in order to determine how estrogen therapy affected BMD and assess the prevalence of low bone mass among this population.

The hypothesis, said Dr. Fighera, was that hormone therapy for transgender women might decrease muscle mass and increase fat mass, “leading to less bone surface strain and smaller bone size over time,” said Dr. Fighera, of the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil.

Previous work has shown conflicting results, she said. “While some studies report that estrogen therapy is able to increase bone mass, others have observed no difference in BMD” despite the use of hormone therapy. The studies showing an association between estrogen therapy and decreased bone mass were those that followed patients for longer periods of time – 2 years or longer, she said.

Dr. Fighera explained that in Brazil, individuals with gender dysphoria have free access to hormone therapy and gender-affirming surgery through the public health service.

A total of 142 transgender women enrolled in the study, conducted at outpatient endocrine clinics for transgender people in Porto Alegre, Brazil. The clinics’ standardized hormone therapy protocol used daily estradiol valerate 1-4 mg, daily conjugated equine estrogen 0.625-2.5 mg, or daily transdermal 17 beta estradiol 0.5-2 mg. The estrogen therapy was accompanied by either spironolactone 50-150 mg per day, or cyproterone acetate 50-100 mg per day.

For comparison, the investigators enrolled 22 men and 17 women aged 18-40 years. All participants received a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan 3 months after those in the transgender arm began hormone therapy, and a second scan at 12 months. For the first year, participants were seen for clinical evaluation and lab studies every 3 months; they were seen every 6 months thereafter.

Although ranges were wide, estradiol levels in transgender women were, on average, approximately intermediate between the female and male control values. Total testosterone for transgender women was an average 1.17 nmol/L, closer to female (0.79 nmol/L) than male (16.39 nmol/L) values.

In a subgroup of 46 participants, Dr. Fighera and her colleagues also examined change over time for transgender women who remained on hormone therapy. Though they did find that appendicular lean mass declined and total fat mass increased from baseline, these changes in body composition were not associated with significant decreases in any BMD measurement when the DXA scan was repeated at 31 months.

Participants’ mean age was 33.7 years, and the mean BMI was 25.4 kg/m2. One-third of participants had already undergone gender-affirming surgery , and most (86.6%) had some previous exposure to hormone therapy. Almost all (96%) of study participants were white.

At 18%, “the prevalence of low bone mass for age was fairly high in this sample of [transgender women] from southern Brazil,” said Dr. Fighera. She called for more work to track change over time in hormone therapy–related bone loss for transgender women. “Until then, monitoring of bone mass should be considered in this population; nonpharmacological lifestyle-related strategies for preventing bone loss may benefit transgender women” who receive long-term hormone therapy, she said.

None of the study authors had disclosures to report.

SOURCE: Fighera T et al. ENDO 2018, Abstract OR 25-5.

CHICAGO – according to findings from a recent Brazilian study.

“Lumbar spine density was lower than in reference men but similar to that of reference women,” said Tayane Muniz Fighera, MD, speaking at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Lower lumbar spine density in transgender women was associated with lower appendicular lean mass and higher total fat mass, with correlation coefficients of 0.327 and 0.334, respectively (P = .0001 for both).

Dr. Fighera and her colleagues looked at the independent contribution of age, estradiol level, appendicular lean mass, and fat mass to bone mineral density (BMD) in the transgender patients, using linear regression analysis. Total fat mass and appendicular lean mass were both independent predictors of bone mineral density (P = .001 and P = .022, respectively). For femur BMD, age, and total fat mass were predictors (P = .001 and P = .000, respectively).

The study aimed to assess bone mineral density as well as other aspects of body composition within a cohort of transgender women initiating hormone therapy in order to determine how estrogen therapy affected BMD and assess the prevalence of low bone mass among this population.

The hypothesis, said Dr. Fighera, was that hormone therapy for transgender women might decrease muscle mass and increase fat mass, “leading to less bone surface strain and smaller bone size over time,” said Dr. Fighera, of the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil.

Previous work has shown conflicting results, she said. “While some studies report that estrogen therapy is able to increase bone mass, others have observed no difference in BMD” despite the use of hormone therapy. The studies showing an association between estrogen therapy and decreased bone mass were those that followed patients for longer periods of time – 2 years or longer, she said.

Dr. Fighera explained that in Brazil, individuals with gender dysphoria have free access to hormone therapy and gender-affirming surgery through the public health service.

A total of 142 transgender women enrolled in the study, conducted at outpatient endocrine clinics for transgender people in Porto Alegre, Brazil. The clinics’ standardized hormone therapy protocol used daily estradiol valerate 1-4 mg, daily conjugated equine estrogen 0.625-2.5 mg, or daily transdermal 17 beta estradiol 0.5-2 mg. The estrogen therapy was accompanied by either spironolactone 50-150 mg per day, or cyproterone acetate 50-100 mg per day.

For comparison, the investigators enrolled 22 men and 17 women aged 18-40 years. All participants received a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan 3 months after those in the transgender arm began hormone therapy, and a second scan at 12 months. For the first year, participants were seen for clinical evaluation and lab studies every 3 months; they were seen every 6 months thereafter.

Although ranges were wide, estradiol levels in transgender women were, on average, approximately intermediate between the female and male control values. Total testosterone for transgender women was an average 1.17 nmol/L, closer to female (0.79 nmol/L) than male (16.39 nmol/L) values.

In a subgroup of 46 participants, Dr. Fighera and her colleagues also examined change over time for transgender women who remained on hormone therapy. Though they did find that appendicular lean mass declined and total fat mass increased from baseline, these changes in body composition were not associated with significant decreases in any BMD measurement when the DXA scan was repeated at 31 months.

Participants’ mean age was 33.7 years, and the mean BMI was 25.4 kg/m2. One-third of participants had already undergone gender-affirming surgery , and most (86.6%) had some previous exposure to hormone therapy. Almost all (96%) of study participants were white.

At 18%, “the prevalence of low bone mass for age was fairly high in this sample of [transgender women] from southern Brazil,” said Dr. Fighera. She called for more work to track change over time in hormone therapy–related bone loss for transgender women. “Until then, monitoring of bone mass should be considered in this population; nonpharmacological lifestyle-related strategies for preventing bone loss may benefit transgender women” who receive long-term hormone therapy, she said.

None of the study authors had disclosures to report.

SOURCE: Fighera T et al. ENDO 2018, Abstract OR 25-5.

CHICAGO – according to findings from a recent Brazilian study.

“Lumbar spine density was lower than in reference men but similar to that of reference women,” said Tayane Muniz Fighera, MD, speaking at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Lower lumbar spine density in transgender women was associated with lower appendicular lean mass and higher total fat mass, with correlation coefficients of 0.327 and 0.334, respectively (P = .0001 for both).

Dr. Fighera and her colleagues looked at the independent contribution of age, estradiol level, appendicular lean mass, and fat mass to bone mineral density (BMD) in the transgender patients, using linear regression analysis. Total fat mass and appendicular lean mass were both independent predictors of bone mineral density (P = .001 and P = .022, respectively). For femur BMD, age, and total fat mass were predictors (P = .001 and P = .000, respectively).

The study aimed to assess bone mineral density as well as other aspects of body composition within a cohort of transgender women initiating hormone therapy in order to determine how estrogen therapy affected BMD and assess the prevalence of low bone mass among this population.

The hypothesis, said Dr. Fighera, was that hormone therapy for transgender women might decrease muscle mass and increase fat mass, “leading to less bone surface strain and smaller bone size over time,” said Dr. Fighera, of the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil.

Previous work has shown conflicting results, she said. “While some studies report that estrogen therapy is able to increase bone mass, others have observed no difference in BMD” despite the use of hormone therapy. The studies showing an association between estrogen therapy and decreased bone mass were those that followed patients for longer periods of time – 2 years or longer, she said.

Dr. Fighera explained that in Brazil, individuals with gender dysphoria have free access to hormone therapy and gender-affirming surgery through the public health service.

A total of 142 transgender women enrolled in the study, conducted at outpatient endocrine clinics for transgender people in Porto Alegre, Brazil. The clinics’ standardized hormone therapy protocol used daily estradiol valerate 1-4 mg, daily conjugated equine estrogen 0.625-2.5 mg, or daily transdermal 17 beta estradiol 0.5-2 mg. The estrogen therapy was accompanied by either spironolactone 50-150 mg per day, or cyproterone acetate 50-100 mg per day.

For comparison, the investigators enrolled 22 men and 17 women aged 18-40 years. All participants received a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan 3 months after those in the transgender arm began hormone therapy, and a second scan at 12 months. For the first year, participants were seen for clinical evaluation and lab studies every 3 months; they were seen every 6 months thereafter.

Although ranges were wide, estradiol levels in transgender women were, on average, approximately intermediate between the female and male control values. Total testosterone for transgender women was an average 1.17 nmol/L, closer to female (0.79 nmol/L) than male (16.39 nmol/L) values.

In a subgroup of 46 participants, Dr. Fighera and her colleagues also examined change over time for transgender women who remained on hormone therapy. Though they did find that appendicular lean mass declined and total fat mass increased from baseline, these changes in body composition were not associated with significant decreases in any BMD measurement when the DXA scan was repeated at 31 months.

Participants’ mean age was 33.7 years, and the mean BMI was 25.4 kg/m2. One-third of participants had already undergone gender-affirming surgery , and most (86.6%) had some previous exposure to hormone therapy. Almost all (96%) of study participants were white.

At 18%, “the prevalence of low bone mass for age was fairly high in this sample of [transgender women] from southern Brazil,” said Dr. Fighera. She called for more work to track change over time in hormone therapy–related bone loss for transgender women. “Until then, monitoring of bone mass should be considered in this population; nonpharmacological lifestyle-related strategies for preventing bone loss may benefit transgender women” who receive long-term hormone therapy, she said.

None of the study authors had disclosures to report.

SOURCE: Fighera T et al. ENDO 2018, Abstract OR 25-5.

REPORTING FROM ENDO 2018

Key clinical point: Transgender women on hormone therapy have bone mass more similar to women than men.

Major finding: Lower lumbar spine density was associated with higher total fat mass (P = .001).

Study details: Study of 142 transgender women receiving hormone therapy, tracked over time and compared with 22 men and 17 women for reference.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the Brazilian government. The authors reported that they have no conflicts of interest.

Source: Fighera T et al. ENDO 2018, Abstract OR 25-5.

Neuro updates: Longer stroke window; hold the fresh frozen plasma

ORLANDO – Hospitalists in attendance at a Rapid Fire session at the Society of Hospital Medicine’s annual conference came away with updated information about stroke and intracranial hemorrhage, among the neurologic emergencies commonly seen in hospitalized patients.

Aaron Lord, MD, chief of neurocritical care at New York University Langone Health, provided hopeful news about thrombectomy for ischemic stroke and confirmed the importance of blood pressure management in intracranial hemorrhage in his review of several common neurologic emergencies.

Dr. Lord said that, for ischemic stroke, the evidence is now very good for mechanical thrombectomy, with newer data pointing to a prolonged treatment window for some patients.

Though IV tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) is the only Food and Drug Administration–approved pharmacologic treatment for acute stroke, said Dr. Lord, “It’s good, but it’s not perfect. It doesn’t necessarily target the clot or concentrate in it. ... The big kicker is that not all patients are candidates for IV TPA. They either present too late or have comorbidities.”

“Frustratingly, even for those who do present on time, TPA doesn’t work for everyone. This is especially true for large or long clots,” said Dr. Lord. In 2015, he said, a half-dozen trials examining mechanical thrombectomy for acute stroke were all positive, giving assurance to physicians and patients of this therapy’s efficacy within the 6-8 hour acute stroke window. Pooled analysis of the 2015 trials showed a number needed to treat (NNT) of 5 for regaining functional independence, and a NNT of 2.6 for decreased disability.

Further, he said, two additional trials have examined thrombectomy’s utility when patients have a large stroke penumbra, with a relatively small core infarct, using “tissue-based parameters rather than time” to select patients for thrombectomy. “These trials were just as positive as the initial trials,” said Dr. Lord; the trials showed NNTs of 2.9 and 3.6 for reduced disability in a population of patients who were 6-24 hours poststroke.

The takeaway for hospitalists? Even when it’s unknown how much time has passed since the onset of stroke symptoms, step No. 1 is still to activate the stroke team’s resources, giving patients the best hope for recovery. “We now have the luxury of treating patients up to 24 hours. This has revolutionized the way that we treat acute stroke,” said Dr. Lord.

For intracranial hemorrhage, the story is a little different. Here, “initial management focuses on preventing hematoma expansion,” said Dr. Lord.

After tending to airway, breathing, and circulation and activation of the stroke team, the managing clinician should turn to blood pressure management and reversal of any anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy.

The medical literature gives some guidance about goal blood pressures, he said. Although all of the trials did not use the same parameters for “highest” or “lower” systolic blood pressures, the best data available point toward a systolic goal of about 140.

“Blood pressure treatment is still important,” said Dr. Lord. In larger hemorrhages or with hydrocephalus, he advised always at least considering placement of an intracranial pressure monitor.

If a patient is anticoagulated with a vitamin K antagonist, he said, the INCH trial showed that intracranial bleeds are best reversed by use of prothrombin complex concentration (PCC), rather than fresh frozen plasma (FFP). The trial, stopped early for safety, showed that the primary outcome of internationalized normal ratio of less than 1.2 by the 3-hour mark was reached by just 9% of the FFP group, compared with 67% of those who received PCC. Mortality was 35% for the FFP cohort, compared with 19% who received PCC.

Dr. Lord finds these data compelling. “When I ask my residents what the appropriate agent is for vitamin K reversal in acute ICH, and they answer FFP, I tell them, ‘That’s a great answer ... for 2012.’ ”

ORLANDO – Hospitalists in attendance at a Rapid Fire session at the Society of Hospital Medicine’s annual conference came away with updated information about stroke and intracranial hemorrhage, among the neurologic emergencies commonly seen in hospitalized patients.

Aaron Lord, MD, chief of neurocritical care at New York University Langone Health, provided hopeful news about thrombectomy for ischemic stroke and confirmed the importance of blood pressure management in intracranial hemorrhage in his review of several common neurologic emergencies.

Dr. Lord said that, for ischemic stroke, the evidence is now very good for mechanical thrombectomy, with newer data pointing to a prolonged treatment window for some patients.

Though IV tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) is the only Food and Drug Administration–approved pharmacologic treatment for acute stroke, said Dr. Lord, “It’s good, but it’s not perfect. It doesn’t necessarily target the clot or concentrate in it. ... The big kicker is that not all patients are candidates for IV TPA. They either present too late or have comorbidities.”

“Frustratingly, even for those who do present on time, TPA doesn’t work for everyone. This is especially true for large or long clots,” said Dr. Lord. In 2015, he said, a half-dozen trials examining mechanical thrombectomy for acute stroke were all positive, giving assurance to physicians and patients of this therapy’s efficacy within the 6-8 hour acute stroke window. Pooled analysis of the 2015 trials showed a number needed to treat (NNT) of 5 for regaining functional independence, and a NNT of 2.6 for decreased disability.

Further, he said, two additional trials have examined thrombectomy’s utility when patients have a large stroke penumbra, with a relatively small core infarct, using “tissue-based parameters rather than time” to select patients for thrombectomy. “These trials were just as positive as the initial trials,” said Dr. Lord; the trials showed NNTs of 2.9 and 3.6 for reduced disability in a population of patients who were 6-24 hours poststroke.

The takeaway for hospitalists? Even when it’s unknown how much time has passed since the onset of stroke symptoms, step No. 1 is still to activate the stroke team’s resources, giving patients the best hope for recovery. “We now have the luxury of treating patients up to 24 hours. This has revolutionized the way that we treat acute stroke,” said Dr. Lord.

For intracranial hemorrhage, the story is a little different. Here, “initial management focuses on preventing hematoma expansion,” said Dr. Lord.

After tending to airway, breathing, and circulation and activation of the stroke team, the managing clinician should turn to blood pressure management and reversal of any anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy.

The medical literature gives some guidance about goal blood pressures, he said. Although all of the trials did not use the same parameters for “highest” or “lower” systolic blood pressures, the best data available point toward a systolic goal of about 140.

“Blood pressure treatment is still important,” said Dr. Lord. In larger hemorrhages or with hydrocephalus, he advised always at least considering placement of an intracranial pressure monitor.

If a patient is anticoagulated with a vitamin K antagonist, he said, the INCH trial showed that intracranial bleeds are best reversed by use of prothrombin complex concentration (PCC), rather than fresh frozen plasma (FFP). The trial, stopped early for safety, showed that the primary outcome of internationalized normal ratio of less than 1.2 by the 3-hour mark was reached by just 9% of the FFP group, compared with 67% of those who received PCC. Mortality was 35% for the FFP cohort, compared with 19% who received PCC.

Dr. Lord finds these data compelling. “When I ask my residents what the appropriate agent is for vitamin K reversal in acute ICH, and they answer FFP, I tell them, ‘That’s a great answer ... for 2012.’ ”

ORLANDO – Hospitalists in attendance at a Rapid Fire session at the Society of Hospital Medicine’s annual conference came away with updated information about stroke and intracranial hemorrhage, among the neurologic emergencies commonly seen in hospitalized patients.

Aaron Lord, MD, chief of neurocritical care at New York University Langone Health, provided hopeful news about thrombectomy for ischemic stroke and confirmed the importance of blood pressure management in intracranial hemorrhage in his review of several common neurologic emergencies.

Dr. Lord said that, for ischemic stroke, the evidence is now very good for mechanical thrombectomy, with newer data pointing to a prolonged treatment window for some patients.

Though IV tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) is the only Food and Drug Administration–approved pharmacologic treatment for acute stroke, said Dr. Lord, “It’s good, but it’s not perfect. It doesn’t necessarily target the clot or concentrate in it. ... The big kicker is that not all patients are candidates for IV TPA. They either present too late or have comorbidities.”

“Frustratingly, even for those who do present on time, TPA doesn’t work for everyone. This is especially true for large or long clots,” said Dr. Lord. In 2015, he said, a half-dozen trials examining mechanical thrombectomy for acute stroke were all positive, giving assurance to physicians and patients of this therapy’s efficacy within the 6-8 hour acute stroke window. Pooled analysis of the 2015 trials showed a number needed to treat (NNT) of 5 for regaining functional independence, and a NNT of 2.6 for decreased disability.

Further, he said, two additional trials have examined thrombectomy’s utility when patients have a large stroke penumbra, with a relatively small core infarct, using “tissue-based parameters rather than time” to select patients for thrombectomy. “These trials were just as positive as the initial trials,” said Dr. Lord; the trials showed NNTs of 2.9 and 3.6 for reduced disability in a population of patients who were 6-24 hours poststroke.

The takeaway for hospitalists? Even when it’s unknown how much time has passed since the onset of stroke symptoms, step No. 1 is still to activate the stroke team’s resources, giving patients the best hope for recovery. “We now have the luxury of treating patients up to 24 hours. This has revolutionized the way that we treat acute stroke,” said Dr. Lord.

For intracranial hemorrhage, the story is a little different. Here, “initial management focuses on preventing hematoma expansion,” said Dr. Lord.

After tending to airway, breathing, and circulation and activation of the stroke team, the managing clinician should turn to blood pressure management and reversal of any anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy.

The medical literature gives some guidance about goal blood pressures, he said. Although all of the trials did not use the same parameters for “highest” or “lower” systolic blood pressures, the best data available point toward a systolic goal of about 140.

“Blood pressure treatment is still important,” said Dr. Lord. In larger hemorrhages or with hydrocephalus, he advised always at least considering placement of an intracranial pressure monitor.

If a patient is anticoagulated with a vitamin K antagonist, he said, the INCH trial showed that intracranial bleeds are best reversed by use of prothrombin complex concentration (PCC), rather than fresh frozen plasma (FFP). The trial, stopped early for safety, showed that the primary outcome of internationalized normal ratio of less than 1.2 by the 3-hour mark was reached by just 9% of the FFP group, compared with 67% of those who received PCC. Mortality was 35% for the FFP cohort, compared with 19% who received PCC.

Dr. Lord finds these data compelling. “When I ask my residents what the appropriate agent is for vitamin K reversal in acute ICH, and they answer FFP, I tell them, ‘That’s a great answer ... for 2012.’ ”

REPORTING FROM HM18

‘Update in HM’ to highlight practice pearls

Barbara Slawski, MD, MS, SFHM, and Cynthia Cooper, MD, hadn’t met in person until early 2018. But that doesn’t mean they haven’t spent a lot of time together.

Once a month, the two hospitalists checked in with one another through wide-ranging phone calls. Together, they have combed the medical literature and conferred over the past year, making long lists of candidate studies for the “Top 20” journal articles of the year for practicing hospitalists.

The two physicians will comoderate Tuesday’s “Update in Hospital Medicine” session, where they will summarize research findings of these “Top 20” articles. Their hope is to present research that each attendee can bring home to improve patient outcomes on a daily basis, while making for a smoother and more efficient practice.

Dr. Slawski, chief of the section of perioperative medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, said the presentations will not simply summarize study results but also will help attendees focus on the key findings – the clinical pearls – that represent real opportunities to update practice.

Since hospital medicine crosses so many disciplines, each physician said, in separate interviews, that doing justice to the literature has been time consuming and intellectually challenging – but worthwhile.

Dr. Cooper, a hospitalist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said that, although she and Dr. Slawski practice in geographically diverse areas, their practice settings – academic medical centers – have many similarities. She said that, as she reviewed the medical literature over the past year, she gave considerable thought to the particular challenges and demands of hospitalists who practice in community hospitals and rural settings, where the level of support and access to subspecialty consults might be very different from the academic milieu.

“We hope that our unique approaches lend more breadth to the session,” said Dr. Slawski. “We want to make sure we have a good representation of SHM’s constituency, and that we present high-impact studies.”

To hit the mark of articles that are relevant for all, Dr. Cooper said she wants to make sure to focus on the practicalities of hospital-based practice – possible topics include prediction scores, hepatic encephalopathy, and the management of sepsis.

Neither Dr. Slawski nor Dr. Cooper reported any relevant conflicts of interest.

Update in Hospital Medicine

Tuesday, 1:40-2:40 p.m.

Palms Ballroom

Barbara Slawski, MD, MS, SFHM, and Cynthia Cooper, MD, hadn’t met in person until early 2018. But that doesn’t mean they haven’t spent a lot of time together.

Once a month, the two hospitalists checked in with one another through wide-ranging phone calls. Together, they have combed the medical literature and conferred over the past year, making long lists of candidate studies for the “Top 20” journal articles of the year for practicing hospitalists.

The two physicians will comoderate Tuesday’s “Update in Hospital Medicine” session, where they will summarize research findings of these “Top 20” articles. Their hope is to present research that each attendee can bring home to improve patient outcomes on a daily basis, while making for a smoother and more efficient practice.

Dr. Slawski, chief of the section of perioperative medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, said the presentations will not simply summarize study results but also will help attendees focus on the key findings – the clinical pearls – that represent real opportunities to update practice.

Since hospital medicine crosses so many disciplines, each physician said, in separate interviews, that doing justice to the literature has been time consuming and intellectually challenging – but worthwhile.

Dr. Cooper, a hospitalist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said that, although she and Dr. Slawski practice in geographically diverse areas, their practice settings – academic medical centers – have many similarities. She said that, as she reviewed the medical literature over the past year, she gave considerable thought to the particular challenges and demands of hospitalists who practice in community hospitals and rural settings, where the level of support and access to subspecialty consults might be very different from the academic milieu.

“We hope that our unique approaches lend more breadth to the session,” said Dr. Slawski. “We want to make sure we have a good representation of SHM’s constituency, and that we present high-impact studies.”

To hit the mark of articles that are relevant for all, Dr. Cooper said she wants to make sure to focus on the practicalities of hospital-based practice – possible topics include prediction scores, hepatic encephalopathy, and the management of sepsis.

Neither Dr. Slawski nor Dr. Cooper reported any relevant conflicts of interest.

Update in Hospital Medicine

Tuesday, 1:40-2:40 p.m.

Palms Ballroom

Barbara Slawski, MD, MS, SFHM, and Cynthia Cooper, MD, hadn’t met in person until early 2018. But that doesn’t mean they haven’t spent a lot of time together.

Once a month, the two hospitalists checked in with one another through wide-ranging phone calls. Together, they have combed the medical literature and conferred over the past year, making long lists of candidate studies for the “Top 20” journal articles of the year for practicing hospitalists.

The two physicians will comoderate Tuesday’s “Update in Hospital Medicine” session, where they will summarize research findings of these “Top 20” articles. Their hope is to present research that each attendee can bring home to improve patient outcomes on a daily basis, while making for a smoother and more efficient practice.

Dr. Slawski, chief of the section of perioperative medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, said the presentations will not simply summarize study results but also will help attendees focus on the key findings – the clinical pearls – that represent real opportunities to update practice.

Since hospital medicine crosses so many disciplines, each physician said, in separate interviews, that doing justice to the literature has been time consuming and intellectually challenging – but worthwhile.

Dr. Cooper, a hospitalist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said that, although she and Dr. Slawski practice in geographically diverse areas, their practice settings – academic medical centers – have many similarities. She said that, as she reviewed the medical literature over the past year, she gave considerable thought to the particular challenges and demands of hospitalists who practice in community hospitals and rural settings, where the level of support and access to subspecialty consults might be very different from the academic milieu.

“We hope that our unique approaches lend more breadth to the session,” said Dr. Slawski. “We want to make sure we have a good representation of SHM’s constituency, and that we present high-impact studies.”

To hit the mark of articles that are relevant for all, Dr. Cooper said she wants to make sure to focus on the practicalities of hospital-based practice – possible topics include prediction scores, hepatic encephalopathy, and the management of sepsis.

Neither Dr. Slawski nor Dr. Cooper reported any relevant conflicts of interest.

Update in Hospital Medicine

Tuesday, 1:40-2:40 p.m.

Palms Ballroom

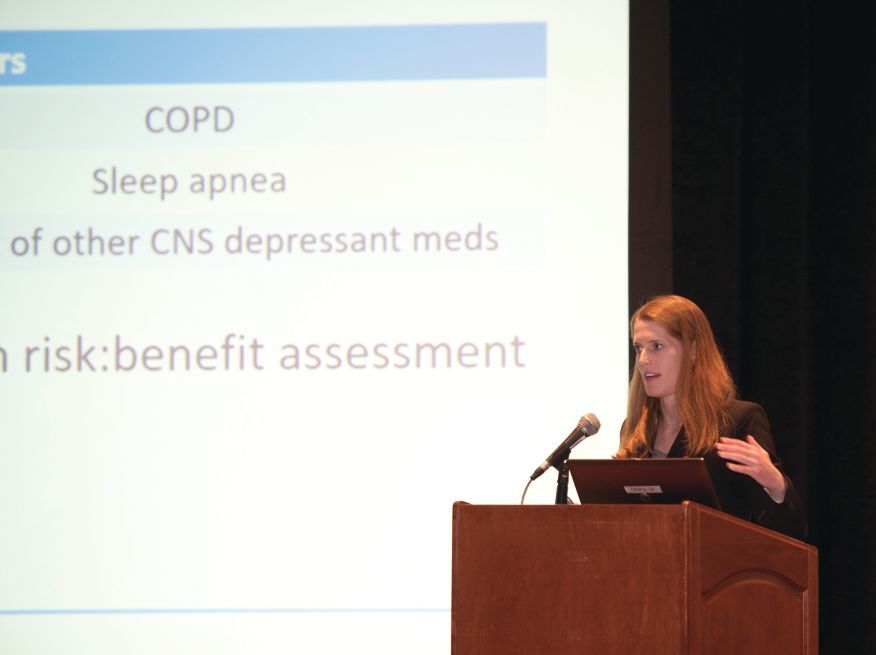

New guidance for inpatient opioid prescribing

ORLANDO – A new guidance statement for opioid prescribing for hospitalized adults who have acute noncancer pain has been issued by the Society for Hospital Medicine.

The statement comes after an exhaustive systematic review that found just four existing guidelines met inclusion criteria, though none focused specifically on acute pain in hospitalized adults.

Among the key issues taken from the existing guidelines and addressed in the new SHM guidance statement are deciding when opioids – or a nonopioid alternative – should be used, as well as selection of appropriate dose, route, and duration of administration. The guidance statement advises that clinicians prescribe the lowest effective opioid dose for the shortest duration possible.

Best practices for screening and monitoring before and during opioid initiation is another major focus, as is minimizing opioid-related adverse events, both by careful patient selection and by judicious prescribing.

Finally, the statement acknowledges that, when a discharge medication list includes an opioid prescription, there is potential risk for misuse or diversion. Accordingly, the recommendation is to limit the duration of outpatient prescribing to 7 days of medication, with consideration of a 3-5 day prescription.

An interactive session at the 2018 SHM annual meeting presenting the guidance statement focused less on marching through the guidance’s 16 specific statements, and more on teasing out the why, when, how – and how long – of inpatient opioid prescribing.

The well-attended session, led by two of the guideline authors, Shoshana Herzig, MD, MPH, and Teryl K. Nuckols, MD, FHM, began with Dr. Herzig, director of hospital medicine research at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, making a compelling case for why guidance is needed for inpatient opioid prescribing for acute pain.

“Few would disagree that, at the end of the day, we are the final common pathway” for hospitalized patients who receive opioids, said Dr. Herzig. And there’s ample evidence that troublesome opioid prescribing is widespread, she said, adding that associated problems aren’t limited to such inpatient adverse events as falls, respiratory arrest, and acute kidney injury; plenty of opioid-exposed patients who leave the hospital continue to use opioids in problematic ways after discharge.

Of patients who were opioid naive and filled outpatient opioid prescriptions on discharge, “Almost half of patients were still using opioids 90 days later,” Dr. Herzig said. “Hospitals contribute to opioid initiation in millions of patients each year, so our prescribing patterns in the hospital do matter.”

“We tend to prescribe high doses,” said Dr. Herzig – an average of a 68-mg oral morphine equivalent (OME) dose on days that opioids were received, according to a 2014 study she coauthored. Overall, Dr. Herzig and her colleagues found that about 40% of patients who received opioids had a daily dose of at least 50 mg OME, and about a quarter received a daily dose at or exceeding 100 mg OME (Herzig et al. J Hosp Med. 2014 Feb;9[2]:73-81).

Further, she said, “We tend to prescribe a bit haphazardly.” The same study found wide variation in regional inpatient opioid-prescribing practices, with inpatients in the U.S. Midwest, South, and West seeing adjusted relative rates of exposure to opioids of 1.26, 1.33, and 1.37, compared with the Northeast, she said.

Among the more concerning findings, she said, was that “hospitals that prescribe opioids more frequently appear to do so less safely.” In hospitals that fell into the top quartile for inpatient opioid exposure, the overall rate of opioid-related adverse events was 0.39%, compared with 0.21% for hospitals in the bottom quartile of opioid prescribing, for an overall adjusted relative risk of 1.23 in opioid-exposed patients in the hospitals with the highest prescribing, said Dr. Herzig.

Dr. Nuckols, director of the division of general internal medicine at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, engaged attendees to identify challenges in acute pain management among hospitalized adults.

The audience was quick and prolific with answers, which included varying physician standards for opioid prescribing; patient expectations for pain management – and sometimes denial that opioid use has become a disorder; varying expectations for pain management among care team members who may be reluctant to let go of pain as “the fifth vital sign;” difficulty accessing and being reimbursed for nonpharmacologic strategies; and, acknowledged by all, patient satisfaction scores.

To this last point, Dr. Nuckols said that there have been “a few recent changes for the better.” The Joint Commission is revising its standards to move away from pain as a vital sign, toward a focused assessment of pain that considers how patients are responding to pain, as well as functional status. However, she said, “There aren’t any validated measures yet for how we’re going to do this.”

Similar shifts are underway with pain-related HCAHPS (the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) questions, which have undergone a “big pullback” from an emphasis on complete control of pain, and now put more focus on whether caregivers asked about pain and talked with inpatients about ways to treat pain, said Dr. Nuckols.

Speaking to the process of developing the guidance statement, Dr. Nuckols said that “I think it’s important to note that the empirical literature about managing pain for inpatients … is almost nonexistent.” Of the four criteria that met inclusion criteria – “and we were tough raters when it comes to the guidelines” – most were based on expert consensus, she said, and most had primarily an outpatient focus.

Themes that emerged from the review process included consideration of a nonopioid strategy before initiating an opioid. These might include pharmacologic interventions such as acetaminophen or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory for nociceptive pain, pregabalin, gabapentin, or other medication to manage neuropathic pain, or nonpharmacologic interventions such as heat, ice, or distraction. All of these should also be considered as adjuncts to minimize opioid dosing as well, said Dr. Nuckols, citing well-documented synergy with multiple modalities of pain treatment.

Careful patient selection is also key, said Dr. Nuckols. She noted that she asks herself, “How likely is this patient to get into trouble?” with inpatient opioid administration. A concept that goes hand-in-hand, she said, is choosing the appropriate dose and route.

Dr. Herzig picked up this theme, noting that route of administration matters. A speedy route, such as intravenous administration, has been shown to reinforce the potentially addictive effect of opioids. There are times when IV is the route to use, such as when the patient can’t take medication by mouth or when immediate pain control truly is needed. However, oral medication is just as effective, albeit slightly slower acting, she said.

Conversion from IV to oral opioids is a potential time for trouble, said Dr. Herzig. “Always use an opioid conversion chart,” she said. Cross-tolerance can be incomplete between opioids, so safe practice is to begin with about 50% of the OME dose with the new medication and titrate up. And don’t use a long-acting opioid for acute pain, she said, noting that not only will there be a long half-life and washout period if the dose is too high, but patient risk for later opioid use disorder is also upped with this strategy. “You can always add more, but it’s hard to take away,” said Dr. Herzig.

On discharge, consider whether an opioid should be prescribed at all, said Dr. Herzig. The guidance statement advises generally prescribing less than a 7-day supply, with the rationale that, if posthospitalization acute pain is severe enough to require an opioid at that point, the patient should have outpatient follow-up.

This approach doesn’t undertreat outpatient pain, said Dr. Herzig, pointing to studies that show that, at discharge, “the majority of opioids that patients are getting, they are not taking – which tells us that by definition we are overprescribing.”

The authors of the guidance statement wanted to address two important topics that were not sufficiently evidence backed, Dr. Herzig said. They had hoped to give clear guidance about best practices for communication and follow-up with outpatient providers after hospital discharge. Though they didn’t find clear guidance in this area, “We do believe that outpatient providers need to be kept in the loop.”

A second area, currently a hot button topic both in the medical community and in the lay press, is whether a naloxone prescription should accompany an opioid prescription at discharge. “There just aren’t studies for this,” said Dr. Herzig.

The full text of the guidance statement may be found here: https://www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com/jhospmed/article/161927/hospital-medicine/improving-safety-opioid-use-acute-noncancer-pain.

ORLANDO – A new guidance statement for opioid prescribing for hospitalized adults who have acute noncancer pain has been issued by the Society for Hospital Medicine.

The statement comes after an exhaustive systematic review that found just four existing guidelines met inclusion criteria, though none focused specifically on acute pain in hospitalized adults.

Among the key issues taken from the existing guidelines and addressed in the new SHM guidance statement are deciding when opioids – or a nonopioid alternative – should be used, as well as selection of appropriate dose, route, and duration of administration. The guidance statement advises that clinicians prescribe the lowest effective opioid dose for the shortest duration possible.

Best practices for screening and monitoring before and during opioid initiation is another major focus, as is minimizing opioid-related adverse events, both by careful patient selection and by judicious prescribing.

Finally, the statement acknowledges that, when a discharge medication list includes an opioid prescription, there is potential risk for misuse or diversion. Accordingly, the recommendation is to limit the duration of outpatient prescribing to 7 days of medication, with consideration of a 3-5 day prescription.

An interactive session at the 2018 SHM annual meeting presenting the guidance statement focused less on marching through the guidance’s 16 specific statements, and more on teasing out the why, when, how – and how long – of inpatient opioid prescribing.

The well-attended session, led by two of the guideline authors, Shoshana Herzig, MD, MPH, and Teryl K. Nuckols, MD, FHM, began with Dr. Herzig, director of hospital medicine research at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, making a compelling case for why guidance is needed for inpatient opioid prescribing for acute pain.

“Few would disagree that, at the end of the day, we are the final common pathway” for hospitalized patients who receive opioids, said Dr. Herzig. And there’s ample evidence that troublesome opioid prescribing is widespread, she said, adding that associated problems aren’t limited to such inpatient adverse events as falls, respiratory arrest, and acute kidney injury; plenty of opioid-exposed patients who leave the hospital continue to use opioids in problematic ways after discharge.

Of patients who were opioid naive and filled outpatient opioid prescriptions on discharge, “Almost half of patients were still using opioids 90 days later,” Dr. Herzig said. “Hospitals contribute to opioid initiation in millions of patients each year, so our prescribing patterns in the hospital do matter.”

“We tend to prescribe high doses,” said Dr. Herzig – an average of a 68-mg oral morphine equivalent (OME) dose on days that opioids were received, according to a 2014 study she coauthored. Overall, Dr. Herzig and her colleagues found that about 40% of patients who received opioids had a daily dose of at least 50 mg OME, and about a quarter received a daily dose at or exceeding 100 mg OME (Herzig et al. J Hosp Med. 2014 Feb;9[2]:73-81).

Further, she said, “We tend to prescribe a bit haphazardly.” The same study found wide variation in regional inpatient opioid-prescribing practices, with inpatients in the U.S. Midwest, South, and West seeing adjusted relative rates of exposure to opioids of 1.26, 1.33, and 1.37, compared with the Northeast, she said.

Among the more concerning findings, she said, was that “hospitals that prescribe opioids more frequently appear to do so less safely.” In hospitals that fell into the top quartile for inpatient opioid exposure, the overall rate of opioid-related adverse events was 0.39%, compared with 0.21% for hospitals in the bottom quartile of opioid prescribing, for an overall adjusted relative risk of 1.23 in opioid-exposed patients in the hospitals with the highest prescribing, said Dr. Herzig.

Dr. Nuckols, director of the division of general internal medicine at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, engaged attendees to identify challenges in acute pain management among hospitalized adults.

The audience was quick and prolific with answers, which included varying physician standards for opioid prescribing; patient expectations for pain management – and sometimes denial that opioid use has become a disorder; varying expectations for pain management among care team members who may be reluctant to let go of pain as “the fifth vital sign;” difficulty accessing and being reimbursed for nonpharmacologic strategies; and, acknowledged by all, patient satisfaction scores.

To this last point, Dr. Nuckols said that there have been “a few recent changes for the better.” The Joint Commission is revising its standards to move away from pain as a vital sign, toward a focused assessment of pain that considers how patients are responding to pain, as well as functional status. However, she said, “There aren’t any validated measures yet for how we’re going to do this.”

Similar shifts are underway with pain-related HCAHPS (the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) questions, which have undergone a “big pullback” from an emphasis on complete control of pain, and now put more focus on whether caregivers asked about pain and talked with inpatients about ways to treat pain, said Dr. Nuckols.

Speaking to the process of developing the guidance statement, Dr. Nuckols said that “I think it’s important to note that the empirical literature about managing pain for inpatients … is almost nonexistent.” Of the four criteria that met inclusion criteria – “and we were tough raters when it comes to the guidelines” – most were based on expert consensus, she said, and most had primarily an outpatient focus.

Themes that emerged from the review process included consideration of a nonopioid strategy before initiating an opioid. These might include pharmacologic interventions such as acetaminophen or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory for nociceptive pain, pregabalin, gabapentin, or other medication to manage neuropathic pain, or nonpharmacologic interventions such as heat, ice, or distraction. All of these should also be considered as adjuncts to minimize opioid dosing as well, said Dr. Nuckols, citing well-documented synergy with multiple modalities of pain treatment.

Careful patient selection is also key, said Dr. Nuckols. She noted that she asks herself, “How likely is this patient to get into trouble?” with inpatient opioid administration. A concept that goes hand-in-hand, she said, is choosing the appropriate dose and route.

Dr. Herzig picked up this theme, noting that route of administration matters. A speedy route, such as intravenous administration, has been shown to reinforce the potentially addictive effect of opioids. There are times when IV is the route to use, such as when the patient can’t take medication by mouth or when immediate pain control truly is needed. However, oral medication is just as effective, albeit slightly slower acting, she said.

Conversion from IV to oral opioids is a potential time for trouble, said Dr. Herzig. “Always use an opioid conversion chart,” she said. Cross-tolerance can be incomplete between opioids, so safe practice is to begin with about 50% of the OME dose with the new medication and titrate up. And don’t use a long-acting opioid for acute pain, she said, noting that not only will there be a long half-life and washout period if the dose is too high, but patient risk for later opioid use disorder is also upped with this strategy. “You can always add more, but it’s hard to take away,” said Dr. Herzig.

On discharge, consider whether an opioid should be prescribed at all, said Dr. Herzig. The guidance statement advises generally prescribing less than a 7-day supply, with the rationale that, if posthospitalization acute pain is severe enough to require an opioid at that point, the patient should have outpatient follow-up.

This approach doesn’t undertreat outpatient pain, said Dr. Herzig, pointing to studies that show that, at discharge, “the majority of opioids that patients are getting, they are not taking – which tells us that by definition we are overprescribing.”

The authors of the guidance statement wanted to address two important topics that were not sufficiently evidence backed, Dr. Herzig said. They had hoped to give clear guidance about best practices for communication and follow-up with outpatient providers after hospital discharge. Though they didn’t find clear guidance in this area, “We do believe that outpatient providers need to be kept in the loop.”

A second area, currently a hot button topic both in the medical community and in the lay press, is whether a naloxone prescription should accompany an opioid prescription at discharge. “There just aren’t studies for this,” said Dr. Herzig.

The full text of the guidance statement may be found here: https://www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com/jhospmed/article/161927/hospital-medicine/improving-safety-opioid-use-acute-noncancer-pain.

ORLANDO – A new guidance statement for opioid prescribing for hospitalized adults who have acute noncancer pain has been issued by the Society for Hospital Medicine.

The statement comes after an exhaustive systematic review that found just four existing guidelines met inclusion criteria, though none focused specifically on acute pain in hospitalized adults.

Among the key issues taken from the existing guidelines and addressed in the new SHM guidance statement are deciding when opioids – or a nonopioid alternative – should be used, as well as selection of appropriate dose, route, and duration of administration. The guidance statement advises that clinicians prescribe the lowest effective opioid dose for the shortest duration possible.

Best practices for screening and monitoring before and during opioid initiation is another major focus, as is minimizing opioid-related adverse events, both by careful patient selection and by judicious prescribing.

Finally, the statement acknowledges that, when a discharge medication list includes an opioid prescription, there is potential risk for misuse or diversion. Accordingly, the recommendation is to limit the duration of outpatient prescribing to 7 days of medication, with consideration of a 3-5 day prescription.

An interactive session at the 2018 SHM annual meeting presenting the guidance statement focused less on marching through the guidance’s 16 specific statements, and more on teasing out the why, when, how – and how long – of inpatient opioid prescribing.

The well-attended session, led by two of the guideline authors, Shoshana Herzig, MD, MPH, and Teryl K. Nuckols, MD, FHM, began with Dr. Herzig, director of hospital medicine research at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, making a compelling case for why guidance is needed for inpatient opioid prescribing for acute pain.

“Few would disagree that, at the end of the day, we are the final common pathway” for hospitalized patients who receive opioids, said Dr. Herzig. And there’s ample evidence that troublesome opioid prescribing is widespread, she said, adding that associated problems aren’t limited to such inpatient adverse events as falls, respiratory arrest, and acute kidney injury; plenty of opioid-exposed patients who leave the hospital continue to use opioids in problematic ways after discharge.

Of patients who were opioid naive and filled outpatient opioid prescriptions on discharge, “Almost half of patients were still using opioids 90 days later,” Dr. Herzig said. “Hospitals contribute to opioid initiation in millions of patients each year, so our prescribing patterns in the hospital do matter.”

“We tend to prescribe high doses,” said Dr. Herzig – an average of a 68-mg oral morphine equivalent (OME) dose on days that opioids were received, according to a 2014 study she coauthored. Overall, Dr. Herzig and her colleagues found that about 40% of patients who received opioids had a daily dose of at least 50 mg OME, and about a quarter received a daily dose at or exceeding 100 mg OME (Herzig et al. J Hosp Med. 2014 Feb;9[2]:73-81).

Further, she said, “We tend to prescribe a bit haphazardly.” The same study found wide variation in regional inpatient opioid-prescribing practices, with inpatients in the U.S. Midwest, South, and West seeing adjusted relative rates of exposure to opioids of 1.26, 1.33, and 1.37, compared with the Northeast, she said.

Among the more concerning findings, she said, was that “hospitals that prescribe opioids more frequently appear to do so less safely.” In hospitals that fell into the top quartile for inpatient opioid exposure, the overall rate of opioid-related adverse events was 0.39%, compared with 0.21% for hospitals in the bottom quartile of opioid prescribing, for an overall adjusted relative risk of 1.23 in opioid-exposed patients in the hospitals with the highest prescribing, said Dr. Herzig.

Dr. Nuckols, director of the division of general internal medicine at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, engaged attendees to identify challenges in acute pain management among hospitalized adults.

The audience was quick and prolific with answers, which included varying physician standards for opioid prescribing; patient expectations for pain management – and sometimes denial that opioid use has become a disorder; varying expectations for pain management among care team members who may be reluctant to let go of pain as “the fifth vital sign;” difficulty accessing and being reimbursed for nonpharmacologic strategies; and, acknowledged by all, patient satisfaction scores.

To this last point, Dr. Nuckols said that there have been “a few recent changes for the better.” The Joint Commission is revising its standards to move away from pain as a vital sign, toward a focused assessment of pain that considers how patients are responding to pain, as well as functional status. However, she said, “There aren’t any validated measures yet for how we’re going to do this.”

Similar shifts are underway with pain-related HCAHPS (the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) questions, which have undergone a “big pullback” from an emphasis on complete control of pain, and now put more focus on whether caregivers asked about pain and talked with inpatients about ways to treat pain, said Dr. Nuckols.

Speaking to the process of developing the guidance statement, Dr. Nuckols said that “I think it’s important to note that the empirical literature about managing pain for inpatients … is almost nonexistent.” Of the four criteria that met inclusion criteria – “and we were tough raters when it comes to the guidelines” – most were based on expert consensus, she said, and most had primarily an outpatient focus.

Themes that emerged from the review process included consideration of a nonopioid strategy before initiating an opioid. These might include pharmacologic interventions such as acetaminophen or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory for nociceptive pain, pregabalin, gabapentin, or other medication to manage neuropathic pain, or nonpharmacologic interventions such as heat, ice, or distraction. All of these should also be considered as adjuncts to minimize opioid dosing as well, said Dr. Nuckols, citing well-documented synergy with multiple modalities of pain treatment.

Careful patient selection is also key, said Dr. Nuckols. She noted that she asks herself, “How likely is this patient to get into trouble?” with inpatient opioid administration. A concept that goes hand-in-hand, she said, is choosing the appropriate dose and route.

Dr. Herzig picked up this theme, noting that route of administration matters. A speedy route, such as intravenous administration, has been shown to reinforce the potentially addictive effect of opioids. There are times when IV is the route to use, such as when the patient can’t take medication by mouth or when immediate pain control truly is needed. However, oral medication is just as effective, albeit slightly slower acting, she said.

Conversion from IV to oral opioids is a potential time for trouble, said Dr. Herzig. “Always use an opioid conversion chart,” she said. Cross-tolerance can be incomplete between opioids, so safe practice is to begin with about 50% of the OME dose with the new medication and titrate up. And don’t use a long-acting opioid for acute pain, she said, noting that not only will there be a long half-life and washout period if the dose is too high, but patient risk for later opioid use disorder is also upped with this strategy. “You can always add more, but it’s hard to take away,” said Dr. Herzig.

On discharge, consider whether an opioid should be prescribed at all, said Dr. Herzig. The guidance statement advises generally prescribing less than a 7-day supply, with the rationale that, if posthospitalization acute pain is severe enough to require an opioid at that point, the patient should have outpatient follow-up.

This approach doesn’t undertreat outpatient pain, said Dr. Herzig, pointing to studies that show that, at discharge, “the majority of opioids that patients are getting, they are not taking – which tells us that by definition we are overprescribing.”

The authors of the guidance statement wanted to address two important topics that were not sufficiently evidence backed, Dr. Herzig said. They had hoped to give clear guidance about best practices for communication and follow-up with outpatient providers after hospital discharge. Though they didn’t find clear guidance in this area, “We do believe that outpatient providers need to be kept in the loop.”

A second area, currently a hot button topic both in the medical community and in the lay press, is whether a naloxone prescription should accompany an opioid prescription at discharge. “There just aren’t studies for this,” said Dr. Herzig.

The full text of the guidance statement may be found here: https://www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com/jhospmed/article/161927/hospital-medicine/improving-safety-opioid-use-acute-noncancer-pain.

REPORTING FROM HM18

SHM presidents: Innovate and avoid complacency

ORLANDO – In a time of tumult in American health care, hospital medicine can expect to see a reimagined – but not reduced – role, said the outgoing and current presidents of the Society of Hospital Medicine at Monday’s HM18 opening plenary.

Despite the many successes of the relatively young field of hospital medicine, there’s no room for complacency, said SHM’s immediate past president Ron Greeno, MD, MHM.

Dr. Greeno drew on his 25-year career in hospital medicine to frame past successes and upcoming challenges for hospital medicine in the 21st century.

As the profession defined itself and grew from the 1980s onward, “the model was challenged, and challenged significantly, mostly by our physician colleagues,” who either feared or didn’t understand the model, he said. All along, though, pioneers in hospital medicine were just trying “to figure out a way to take better care of patients in the hospital.”

The result, said Dr. Greeno, is that hospital medicine stands unique among physician specialties. “We as a specialty are in a very enviable position as we move into the post–health care reform era. More than any other specialty in the history of medicine, we are not expected to p

“Colleagues honor us by trusting us with their patients’ care … but we need to be aware that they are watching us and judging whether we are living up to our promises,” Dr. Greeno said. “So we need to be asking ourselves some tough questions. Perhaps we’re becoming too self-satisfied. Perhaps we are starting to believe our own press.”

Without an appetite for innovation as well as hard work, hospitalists could risk becoming “highly paid worker bees,” said Dr. Greeno.

“There are people who think this is happening. I know because I have talked to them while traveling around the country” as SHM president, he said. “I am not among that group. I think the best is yet to come … that we will become more integrated and have ever more impact and influence in the redesign of the U.S. health care system.”

More than anything, Dr. Greeno’s faith in the profession’s future is grounded in its human capital. Addressing the plenary attendees, he said, “You come here just to become better, to try to make things better. I see all of you who refuse to let the urgent get in the way of the important.”

In her first address as the new SHM president, Nasim Afsar, MD, SFHM, agreed that the people really do make the profession. “We will prevail because of our perseverance and our passion to be part of the solution for challenges in health care,” she said.

Dr. Afsar is chief ambulatory officer and chief medical officer for ACOs at UC Irvine Health. She said that earlier this year, she’d never felt more sure of her job security. Serving on the inpatient hospitalist service during the height of this year’s surging influenza season, Dr. Afsar saw a packed emergency department and a completely full house for her hospital. “We had to create a new hospitalist service” just to handle the volume, she said.

A sobering experience later that month, though, had her rethinking things. At a meeting of chief executive officers of health care systems, leaders spoke of hospitals transitioning from profit centers to cost centers. Some of the proposed innovations were startling: “When I heard talk of hospitals at home, and of virtual hospitals, I got a very different sense of our specialty,” said Dr. Afsar.

Still, she said, she’s confident there will be jobs for hospitalists in the future. “We can’t ignore the significant, irrefutable fact that has emerged: Value will prevail. And the only way to deliver that is population health management,” meaning the delivery of high value care at fair cost across the entire human lifespan, she said.

This call can be answered in two ways, said Dr. Afsar. “First, we have to define and deliver value for hospitalized patients every single day. Second, we have to look at what population health management means for our specialty.”

“I encourage us not to be confined by our names,” Dr. Afsar said. Rather, hospitalists will be defined by the attributes that they’ve become known for over the years: “Innovators. Problem solvers. Collaborators. Patient advocates.”

ORLANDO – In a time of tumult in American health care, hospital medicine can expect to see a reimagined – but not reduced – role, said the outgoing and current presidents of the Society of Hospital Medicine at Monday’s HM18 opening plenary.

Despite the many successes of the relatively young field of hospital medicine, there’s no room for complacency, said SHM’s immediate past president Ron Greeno, MD, MHM.

Dr. Greeno drew on his 25-year career in hospital medicine to frame past successes and upcoming challenges for hospital medicine in the 21st century.

As the profession defined itself and grew from the 1980s onward, “the model was challenged, and challenged significantly, mostly by our physician colleagues,” who either feared or didn’t understand the model, he said. All along, though, pioneers in hospital medicine were just trying “to figure out a way to take better care of patients in the hospital.”

The result, said Dr. Greeno, is that hospital medicine stands unique among physician specialties. “We as a specialty are in a very enviable position as we move into the post–health care reform era. More than any other specialty in the history of medicine, we are not expected to p

“Colleagues honor us by trusting us with their patients’ care … but we need to be aware that they are watching us and judging whether we are living up to our promises,” Dr. Greeno said. “So we need to be asking ourselves some tough questions. Perhaps we’re becoming too self-satisfied. Perhaps we are starting to believe our own press.”

Without an appetite for innovation as well as hard work, hospitalists could risk becoming “highly paid worker bees,” said Dr. Greeno.

“There are people who think this is happening. I know because I have talked to them while traveling around the country” as SHM president, he said. “I am not among that group. I think the best is yet to come … that we will become more integrated and have ever more impact and influence in the redesign of the U.S. health care system.”

More than anything, Dr. Greeno’s faith in the profession’s future is grounded in its human capital. Addressing the plenary attendees, he said, “You come here just to become better, to try to make things better. I see all of you who refuse to let the urgent get in the way of the important.”

In her first address as the new SHM president, Nasim Afsar, MD, SFHM, agreed that the people really do make the profession. “We will prevail because of our perseverance and our passion to be part of the solution for challenges in health care,” she said.

Dr. Afsar is chief ambulatory officer and chief medical officer for ACOs at UC Irvine Health. She said that earlier this year, she’d never felt more sure of her job security. Serving on the inpatient hospitalist service during the height of this year’s surging influenza season, Dr. Afsar saw a packed emergency department and a completely full house for her hospital. “We had to create a new hospitalist service” just to handle the volume, she said.

A sobering experience later that month, though, had her rethinking things. At a meeting of chief executive officers of health care systems, leaders spoke of hospitals transitioning from profit centers to cost centers. Some of the proposed innovations were startling: “When I heard talk of hospitals at home, and of virtual hospitals, I got a very different sense of our specialty,” said Dr. Afsar.

Still, she said, she’s confident there will be jobs for hospitalists in the future. “We can’t ignore the significant, irrefutable fact that has emerged: Value will prevail. And the only way to deliver that is population health management,” meaning the delivery of high value care at fair cost across the entire human lifespan, she said.

This call can be answered in two ways, said Dr. Afsar. “First, we have to define and deliver value for hospitalized patients every single day. Second, we have to look at what population health management means for our specialty.”

“I encourage us not to be confined by our names,” Dr. Afsar said. Rather, hospitalists will be defined by the attributes that they’ve become known for over the years: “Innovators. Problem solvers. Collaborators. Patient advocates.”

ORLANDO – In a time of tumult in American health care, hospital medicine can expect to see a reimagined – but not reduced – role, said the outgoing and current presidents of the Society of Hospital Medicine at Monday’s HM18 opening plenary.

Despite the many successes of the relatively young field of hospital medicine, there’s no room for complacency, said SHM’s immediate past president Ron Greeno, MD, MHM.

Dr. Greeno drew on his 25-year career in hospital medicine to frame past successes and upcoming challenges for hospital medicine in the 21st century.

As the profession defined itself and grew from the 1980s onward, “the model was challenged, and challenged significantly, mostly by our physician colleagues,” who either feared or didn’t understand the model, he said. All along, though, pioneers in hospital medicine were just trying “to figure out a way to take better care of patients in the hospital.”

The result, said Dr. Greeno, is that hospital medicine stands unique among physician specialties. “We as a specialty are in a very enviable position as we move into the post–health care reform era. More than any other specialty in the history of medicine, we are not expected to p

“Colleagues honor us by trusting us with their patients’ care … but we need to be aware that they are watching us and judging whether we are living up to our promises,” Dr. Greeno said. “So we need to be asking ourselves some tough questions. Perhaps we’re becoming too self-satisfied. Perhaps we are starting to believe our own press.”

Without an appetite for innovation as well as hard work, hospitalists could risk becoming “highly paid worker bees,” said Dr. Greeno.

“There are people who think this is happening. I know because I have talked to them while traveling around the country” as SHM president, he said. “I am not among that group. I think the best is yet to come … that we will become more integrated and have ever more impact and influence in the redesign of the U.S. health care system.”

More than anything, Dr. Greeno’s faith in the profession’s future is grounded in its human capital. Addressing the plenary attendees, he said, “You come here just to become better, to try to make things better. I see all of you who refuse to let the urgent get in the way of the important.”

In her first address as the new SHM president, Nasim Afsar, MD, SFHM, agreed that the people really do make the profession. “We will prevail because of our perseverance and our passion to be part of the solution for challenges in health care,” she said.

Dr. Afsar is chief ambulatory officer and chief medical officer for ACOs at UC Irvine Health. She said that earlier this year, she’d never felt more sure of her job security. Serving on the inpatient hospitalist service during the height of this year’s surging influenza season, Dr. Afsar saw a packed emergency department and a completely full house for her hospital. “We had to create a new hospitalist service” just to handle the volume, she said.

A sobering experience later that month, though, had her rethinking things. At a meeting of chief executive officers of health care systems, leaders spoke of hospitals transitioning from profit centers to cost centers. Some of the proposed innovations were startling: “When I heard talk of hospitals at home, and of virtual hospitals, I got a very different sense of our specialty,” said Dr. Afsar.

Still, she said, she’s confident there will be jobs for hospitalists in the future. “We can’t ignore the significant, irrefutable fact that has emerged: Value will prevail. And the only way to deliver that is population health management,” meaning the delivery of high value care at fair cost across the entire human lifespan, she said.

This call can be answered in two ways, said Dr. Afsar. “First, we have to define and deliver value for hospitalized patients every single day. Second, we have to look at what population health management means for our specialty.”

“I encourage us not to be confined by our names,” Dr. Afsar said. Rather, hospitalists will be defined by the attributes that they’ve become known for over the years: “Innovators. Problem solvers. Collaborators. Patient advocates.”

VIDEO: Poorer cardiometabolic health seen in men with low sperm count

CHICAGO – Low testosterone levels alone didn’t account for the finding, said Alberto Ferlin, MD, PhD, professor of reproductive endocrinology at the University of Brescia, Italy.

“So at the end, we showed that, independent of testosterone, low sperm count could be a marker of general male health, in particular for cardiovascular risk factors or metabolic derangement,” said Dr. Ferlin in an interview following a press conference at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The Italian study, which Dr. Ferlin said was the largest of its kind to date, studied 5,177 males who were part of an infertile couple, comparing men with low sperm count (less than 39 million sperm per ejaculate) with those with normal sperm count (at least 39 million sperm per ejaculate). In all, 2,583 of the participants had low sperm counts.

“Our main aim was to understand if semen analysis and, in general, the reproductive function of a man, could be a marker of his general cardiovascular and metabolic health,” said Dr. Ferlin.

Only men with a comprehensive work-up were included, so all participants had a medical history and physical exam, and semen analysis and culture. Additional components of the evaluation included blood lipid and glucose metabolism testing, reproductive hormone levels, ultrasound of the testes and, for men diagnosed with hypogonadism, bone densitometry.

The study, said Dr. Ferlin, found that among men with a low total sperm count, there was a high prevalence of hypogonadism, defined as both low testosterone and elevated levels of luteinizing hormone. Additionally, these men had a high prevalence of elevated luteinizing hormones with normal testosterone – “so-called subclinical hypogonadism,” said Dr. Ferlin.

In men with a low sperm count – defined as fewer than 39 million sperm per ejaculate – the prevalence of biochemical hypogonadism was about 45%, compared with just 6% in men with normal sperm counts, said Dr. Ferlin. Men with infertility had an odds ratio for hypogonadism of 12.2, said Dr. Ferlin (95% confidence interval, 10.2-14.6).

Additionally, Dr. Ferlin reported that 35% of men with hypogonadism had osteopenia, and 17% met criteria for osteoporosis. The numbers surprised the investigators. “These are very young men – about 30 years old,” said Dr. Ferlin.

Dr. Ferlin and his collaborators also looked at the subset of eugonadal men in the study, comparing those with normal sperm counts (n = 2,431) to those who had low sperm counts, (n = 1,423). They found that men with low sperm counts had significantly higher body mass index, waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, hemoglobin A1c, and homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) levels (P less than .001 for all).

High density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, testosterone, and follicle stimulating hormone levels were also significantly lower for men with low sperm count. “Men with oligozoospermia … have an increased risk of metabolic derangement – so, altered lipid profile with higher LDL cholesterol and lower HDL [cholesterol], higher triglycerides, higher insulin resistance,” said Dr. Ferlin.

The findings have implications for reproductive endocrinologists caring for couples with infertility, said Dr. Ferlin. “Infertile men should be studied comprehensively, and the diagnosis cannot be limited to just one semen analysis,” given the study’s findings, he said. “All these men should be counseled, should be treated … for worsening of these cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors that are present in such frequency in oligozoospermic men.”

Dr. Ferlin reported no conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – Low testosterone levels alone didn’t account for the finding, said Alberto Ferlin, MD, PhD, professor of reproductive endocrinology at the University of Brescia, Italy.

“So at the end, we showed that, independent of testosterone, low sperm count could be a marker of general male health, in particular for cardiovascular risk factors or metabolic derangement,” said Dr. Ferlin in an interview following a press conference at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The Italian study, which Dr. Ferlin said was the largest of its kind to date, studied 5,177 males who were part of an infertile couple, comparing men with low sperm count (less than 39 million sperm per ejaculate) with those with normal sperm count (at least 39 million sperm per ejaculate). In all, 2,583 of the participants had low sperm counts.

“Our main aim was to understand if semen analysis and, in general, the reproductive function of a man, could be a marker of his general cardiovascular and metabolic health,” said Dr. Ferlin.