User login

Reduction in Iatrogenic Pneumothorax

Iatrogenic pneumothorax (IAP) is a complication of invasive procedures that is associated with substantial morbidity and some mortality.[1] IAP is often avoidable, and in many cases can be prevented through adherence to evidence‐based guidelines and procedural techniques known to reduce the incidence of IAP.[2] IAP may occur with a subclavian (SC) or internal jugular (IJ) central venous catheter (CVC) insertion, but is more frequently associated with the SC approach.[3] Ultrasound guidance during IJ CVC insertion is associated with a lower risk as compared to guidance by anatomical landmarks.[4, 5] Other bedside procedures that are known to cause IAP include thoracentesis. This risk can also be reduced with the use of ultrasound guidance.[6]

Including simulation in training for CVC insertion has been demonstrated in meta‐analyses to improve both learner outcomes, including simulator performance and perceived confidence, and patient outcomes, including fewer failed CVC attempts and reduced incidence of IAP.[7] Even brief simulation workshops lasting less than two hours can improve patient safety during CVC insertion.[8]

The implementation of ultrasound‐based simulation and improved adherence to the actual use of ultrasound at the bedside can be motivated by tying competency‐based educational objectives (eg, CVC insertion) to clinical outcomes (ie, rates of IAP) and tracking both as part of a continuous quality‐improvement cycle.[9] Adherence to best practices for CVC insertion can also be improved through standardizing hospital‐wide policies and hands‐on training.[10] Involving many stakeholders, including nurses, physicians, nurse practioners and physician assistants, in a multidisciplinary team has been shown to help alter entrenched behaviors and reduce the incidence of central‐line associated bloodstream infections through long‐term adherence to evidence‐based interventions.[11]

LOCAL PROBLEM

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has designed Patient Safety Indicators (PSIs) (

Our hospital is a member of the University HealthSystem Consortium (UHC) (

Despite this, the PSI can highlight areas where quality‐improvement efforts might be best directed. In 2005 and 2006, our hospital was ranked within the lowest UHC performance quartile for all‐cause IAP PSI.

During FY 2006 (September 2005August 2006), root‐cause analysis on cases of IAP at our hospital found that CVC insertion (40%) was the most common procedure associated with IAP, with SC insertion causing 69% of CVC‐associated IAP. Other common procedures associated with IAP were operative/pacemaker (30%), thoracentesis (25%), and ventilator associated (5%). Ultrasound was not used in 2/5 cases of IJ CVC placement and 3/5 thoracentesis cases. Only 44% of CVC insertions had a procedure note.

Intended Improvement/Study Question

Our team set out to plan and implement a set of multifaceted interventions within 90 days. The short‐term goal was a 50% reduction in the CVC IAP and all‐cause IAP rate within 18 months, and the long‐term goal was sustained reduction of CVC IAP and all‐cause IAP rate.

METHODS

The format of this article is based on the standards for quality‐improvement reporting excellence guidelines for the reporting of studies on the effectiveness of quality‐improvement interventions.[14]

Setting

Stanford University Medical Center is an academic medical center with 465 beds and over 25,000 inpatient admissions per year, providing both general acute care services and tertiary medical care. Residents perform CVC bedside procedures when central venous access is needed, in the intensive care unit (ICU), operating room (OR), and inpatient units. Prior to this project, ultrasound equipment was only available in the emergency department (ED) and ICUs. There was no formal CVC procedure supervision policy, CVC training curriculum, and procedure note templates for documentation of CVC insertion.

Planning the Interventions

A multidisciplinary quality‐improvement team met weekly during the 90‐day design period from January 2007 to March 2007. Our team included representatives from the departments of medicine, anesthesia and critical care, surgery, nursing, and emergency medicine. We also partnered with our institution's clinical and administrative leaders, experts in simulation, and the hospital quality department.

We hypothesized that a standardized set of education and training interventions promoting ultrasound‐guided IJ CVC insertion as the method of choice at our hospital would significantly reduce our rate of CVC‐associated IAP. Our multifaceted intervention included: (1) clinical and documentation standards based on evidence, (2) cognitive aids, (3) simulation training, (4) purchase and deployment of ultrasound equipment, and (5) feedback to clinical services.

Our team followed the define, measure, analyze, improve, control (DMAIC) framework.[15] We set interval goals with target completion dates throughout the 90‐day period, identified owners of each goal, and tracked progress with a shared spreadsheet.

In the 90‐day intervention, we accomplished the following: (1) conducted root‐cause analysis of IAP cases for fiscal year 2006, (2) created clinical and documentation standards around CVC placement, (3) created cognitive aids and procedure note templates, (4) developed simulation training courses, and (5) requested purchase of additional ultrasound equipment.

Data Collection

To evaluate our progress in reducing the rates of IAP, we tracked the incidence of IAP using UHC and AHRQ PSI methodology. In collaboration with our hospital's quality department, we manually reviewed every PSI‐identified case of IAP. This review has focused on identifying whether or not pneumothorax actually occurred, and whether it was associated with CVC insertion. For those associated with CVC, data were collected for patient location and service, the procedure site, whether ultrasound was used, whether a chest tube was required, and the final disposition of the patient.

Demographic data (age, gender, case mix index [CMI]) shown in Table 1 were obtained through MIDAS+ Solutions (Tucson, Arizona), a proprietary database that contains healthcare management coded data. Total hospital CVC insertion rates were calculated using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD‐9) coding for 38.93 and 38.97. ICU central lineassociated blood stream infections (CLABSI) data were obtained from internal collection by our infection control team. Number and location of CVCs placed in the ICU data were obtained from nursing flow sheets in our electronic medical record (EMR). Cost information was provided by our finance department using internal accounting.

| Patients With CVC Insertion | Year | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

| |||||||||

| Age, y (mean) | 55.0 | 55.5 | 55.0 | 57.0 | 56.5 | 58.5 | 57.5 | 59.0 | 58.5 |

| % female | 47.0 | 49.5 | 47.0 | 48.8 | 46.2 | 46.1 | 45.7 | 46.2 | 45.7 |

| Case‐mix index | 3.08 | 3.35 | 3.21 | 3.40 | 3.71 | 3.91 | 3.92 | 3.92 | 4.08 |

| Total no. of CVCs/year* | 1,593 | 1,141 | 1,589 | 2,250 | 2,441 | 2,774 | 2,754 | 2,722 | 2,845 |

| No. of CVCs/year in ICU | NA | NA | NA | 1,502 | 1,357 | 1,345 | 1,316 | 1,421 | 1,590 |

| No. of subclavians/year in ICU | NA | NA | NA | 167 | 75 | 70 | 83 | 75 | 97 |

| No. of IJs/year in ICU | NA | NA | NA | 898 | 773 | 681 | 677 | 713 | 876 |

| No. of femorals/year in ICU | NA | NA | NA | 212 | 152 | 203 | 171 | 198 | 206 |

| No. of PICCs/year in ICU | NA | NA | NA | 225 | 357 | 391 | 385 | 435 | 411 |

| Preintervention (2006) | Postintervention (20082014) | P Value | |||||||

| Age, y (mean) | 55.2 | 58.7 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| % female | 47.0% | 46.4% | 0.642 | ||||||

| Case‐mix index | 3.08 | 3.73 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| CVC insertion rate | 8.1% | 11.4% | <0.0001 | ||||||

| All Inpatients | Year | ||||||||

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

| Age, y (mean) | 57.1 | 57.2 | 56.8 | 57.2 | 57.5 | 58.0 | 58.0 | 57.9 | 58.3 |

| % female | 51.6 | 51.2 | 52.4 | 51.7 | 51.1 | 51.5 | 50.3 | 49.9 | 50.1 |

| Case‐mix index | 1.86 | 1.98 | 1.96 | 1.99 | 1.96 | 2.02 | 2.03 | 2.07 | 2.23 |

| Preintervention (2006) | Postintervention (20082014) | P Value | |||||||

| Age, y (mean) | 57.1 | 57.6 | <0.01 | ||||||

| % female | 51.6% | 50.9% | 0.07 | ||||||

| Case‐mix index | 1.86 | 2.03 | 0.13 | ||||||

| Central Line‐Associated Bloodstream Infections per 1,000 Central Line Days | |||||||||

| Preintervention | Postintervention | P Value | |||||||

| Short term (2006 vs 2008) | 1.8 | 0.60 | 0.004 | ||||||

| Long term (2006 vs 20082014) | 1.8 | 0.68 | <0.0001 | ||||||

The project granted a Notice of Determination of Approval from the Stanford Administrative Panels for the Protection of Human Subjects (institutional review board).

Methods of Evaluation/Analysis

For the purpose of this analysis, the preintervention period was defined as January 1, 2006 through December 31, 2006, our first year of IAP case review. We defined the intervention period as January 1, 2007 through December 31, 2007, during which we planned and implemented hospital‐wide standardization of CVC insertion practices and incorporated CVC insertion training simulation into resident orientation in July 2007. The postintervention period was defined as January 1, 2008 through December 31, 2014.

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). [2] tests were used to determine statistical differences in pre‐ versus postintervention patient demographic data (age, gender, CMI), CVC insertion rates, and CLABSI rates. Because IAP is a rare event, a statistical process control g‐chart was created using QI Macros (KnowWare International, Inc., Denver, CO) to show the number of CVC procedures between IAP. [2] and Fisher exact tests were used to determine statistical differences in CVC anatomic location and use of ultrasound pre‐ and postintervention. A 2‐sided Z test to show a difference in proportions was used to determine statistical differences in CVC‐related IAP rate and all‐cause IAP rate pre‐ and postintervention.

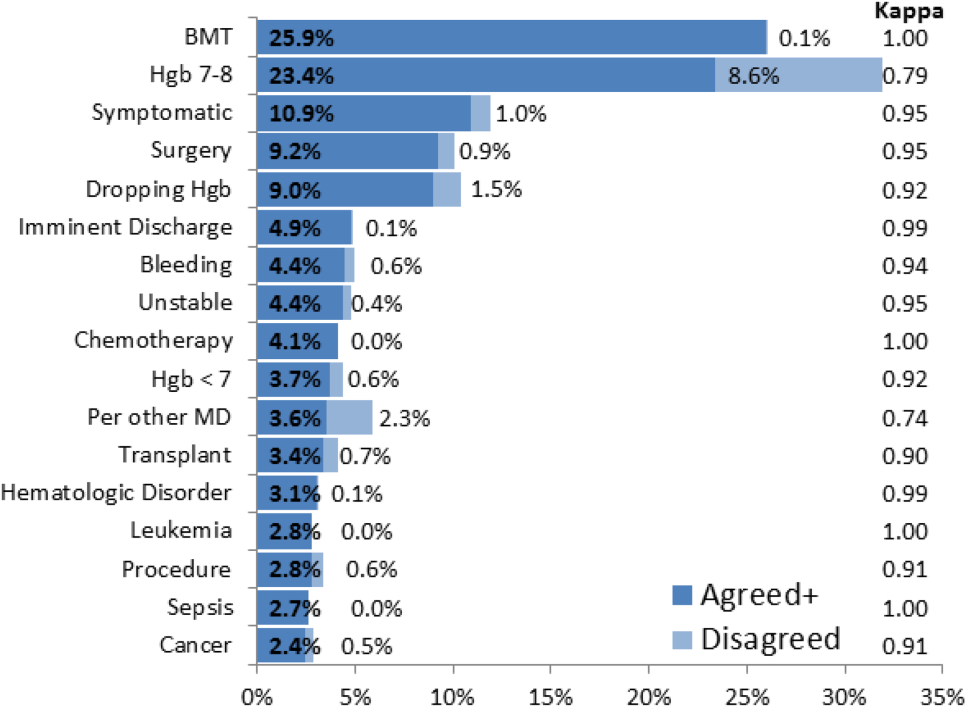

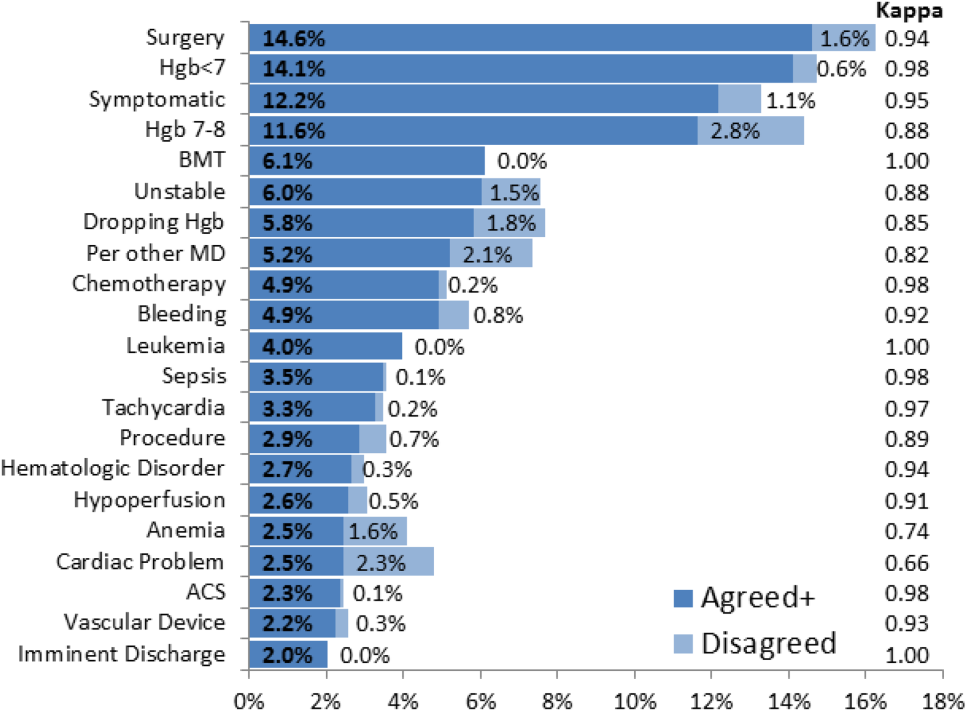

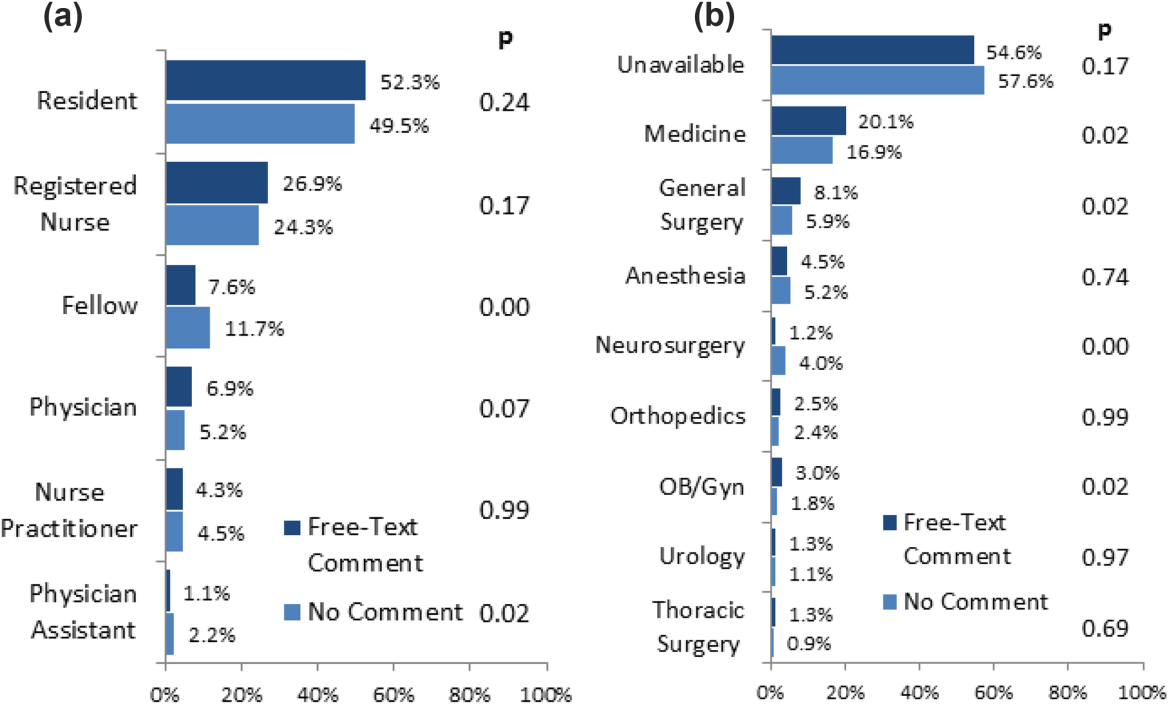

Measuring Adherence to Intervention

Location of CVC Placement and Ultrasound Guidance Pre‐ Versus Postintervention

We utilized the Stanford Clinical Informatics Center (SCCI) services for obtaining counts of patients. Custom queries were performed on SCCI's Stanford Translational Research Integrated Database Environment (STRIDE) platform[16] to search Stanford Hospital electronic heath records for patients. This search primarily involved getting counts for the number of patients with clinical notes that contained the keywords of interest. To identify documentation for placement of CVC from 2006 to 2014, procedure or operative notes containing the words central line or CVC were counted. Further subcounts were obtained by searching for additional keywords such as PICC [peripherally inserted central catheters], femoral, jugular, subclavian, and ultrasound.

Adherence to Intervention in the ICU in 2014

A total of 100 charts were reviewed from patients in our medical and surgical ICU with a CVC in 2014 to evaluate the current trend of central line placement and sustainability of our intervention. Fifty charts were initially randomly selected from the ICU cohort. For those who had multiple lines placed, only the first line was reviewed. Because the initial audit did not provide enough SC lines and we wanted to review more IJ lines, we randomly selected an additional 25 patients who had SC and 25 patients who had IJ to review. The following was collected during chart review: primary team, location of line placement, usage of ultrasound, usage of standard procedure template, supervision, level of training for supervisor, and level of training for staff who performed procedure.

Outcomes

The rate of CVC‐associated IAP was calculated as the total number of IAPs attributed to CVCs divided by the total number of CVCs inserted determined by ICD‐9 coding for 38.93 and 38.97. The total IAP rate was calculated as the total number of IAP/1000 discharges.

RESULTS

Interventions

Our team began the intervention in early 2007 with promotion of ultrasound‐guided IJ catheterization. Clinical exceptions included: (1) trauma or code situations where access to the neck is limited, (2) suspected or confirmed neck injuries, (3) presence of a tracheostomy, and (4) bilateral internal jugular sites unsuitable for catheterization.

Our hospital adopted new formal CVC insertion policies consistent with the above training and education efforts. All physicians were required to document CVC insertions using the template available in the EMR. To be certified to perform CVC insertion independently, trainee physicians were required to complete the simulation training and successfully place a minimum of 5 CVCs directly supervised by an already‐certified physician. This was consistent with the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education suggested minimum requirement in 2007. In our critical care units, all CVC insertions must be supervised by an ICU fellow or attending.

To reinforce the on‐the‐ground work by our physician leaders, we created 2 education tools to embed best practices into our CVC insertion workflow. A checklist with best practices for CVC insertion that was distributed throughout the hospital via central line kits and educational flyers, and a CVC insertion procedure note template consistent with California Department of Public Health documentation requirements was made available in our EMR.

In June 2007, we integrated CVC insertion simulation training into procedure workshops required for all medicine, surgery, anesthesia, and emergency medicine trainees during their intern year. These workshops promoted ultrasound‐guided IJ catheterization and supporting evidence for the new IJ site preference. Training sessions were 2 to 3 hours, and included a demonstration of best‐practice CVC insertion, as well as training with simulation models supervised by an instructor using a standardized CVC checklist. These trainings used both the Blue Phantom human torso model (

Hospital administration provided funds to purchase ultrasound machines for patient units such as medicine, cardiology, ED, and ICU). A total of 4 Site‐Rite (Bard Access Systems, Inc., Salt Lake City, UT) ultrasounds were purchased in 2007. The hospital has continued to purchase ultrasound units yearly, and had 53 ultrasound units in 2014

Cases of IAP were continuously reviewed throughout the intervention period. Based on their higher CVC‐associated IAP rates, the ORs and catheterization lab were identified as having opportunities for improvement. In 2008, Hospital quality‐improvement leadership met with physician leaders in these areas to review their CVC‐related IAP data and to discuss strategies to reduce their IAP rates. These strategies included lessons learned from other services that had successfully decreased their IAP rates.

To sustain our gains, we continue to review all IAP through our coding quality, clinical documentation, quality reporting departments, and peer review. We have implemented other strategies to decrease IAP, such as the use of ultrasound guidance for bedside thoracentesis procedures, which became possible after the availability of more ultrasound devices. Training for ultrasound‐guided thoracentesis was done by our procedure‐team attending during supervision of residents.

Outcomes

Preintervention (January 1, 2006 to December 31, 2006)

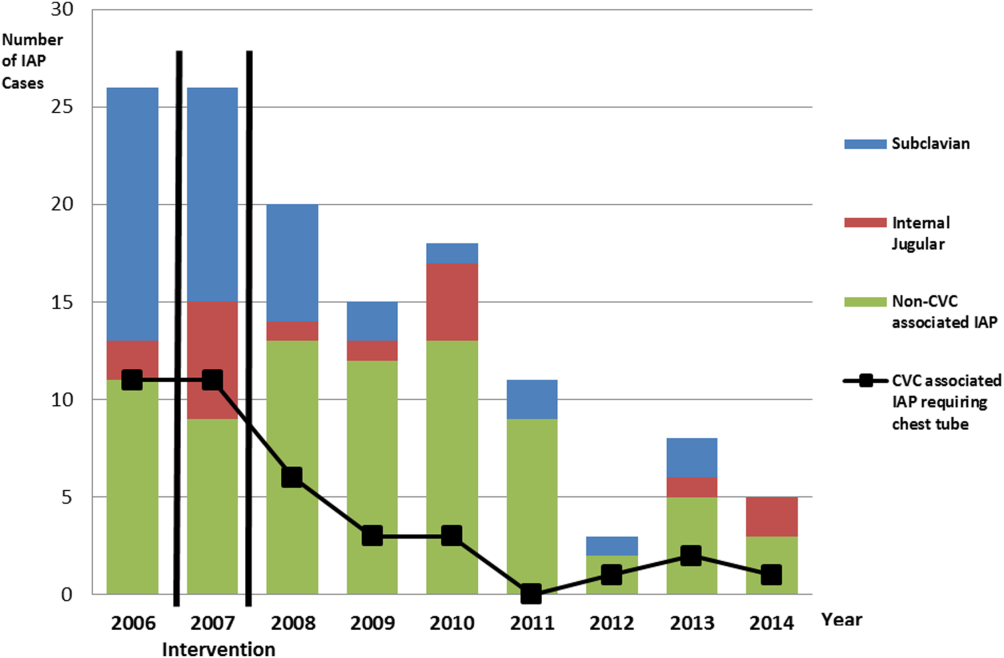

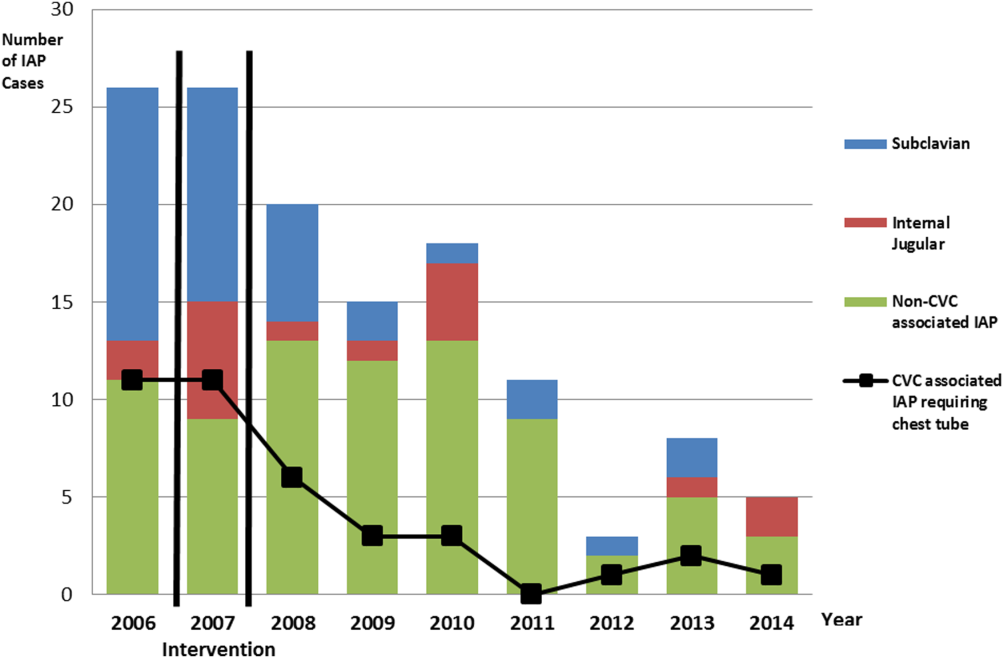

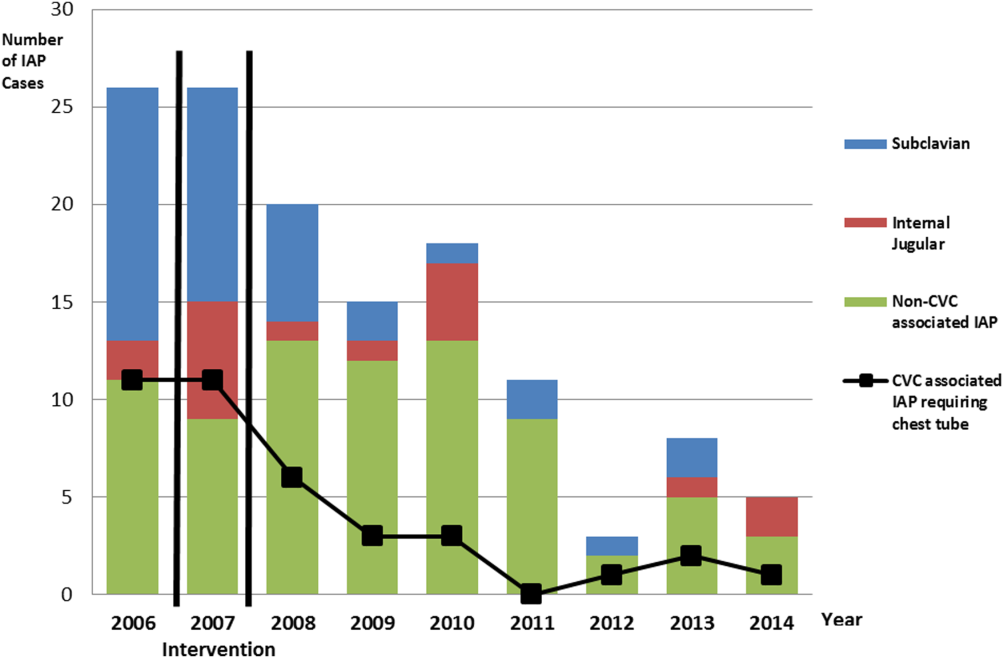

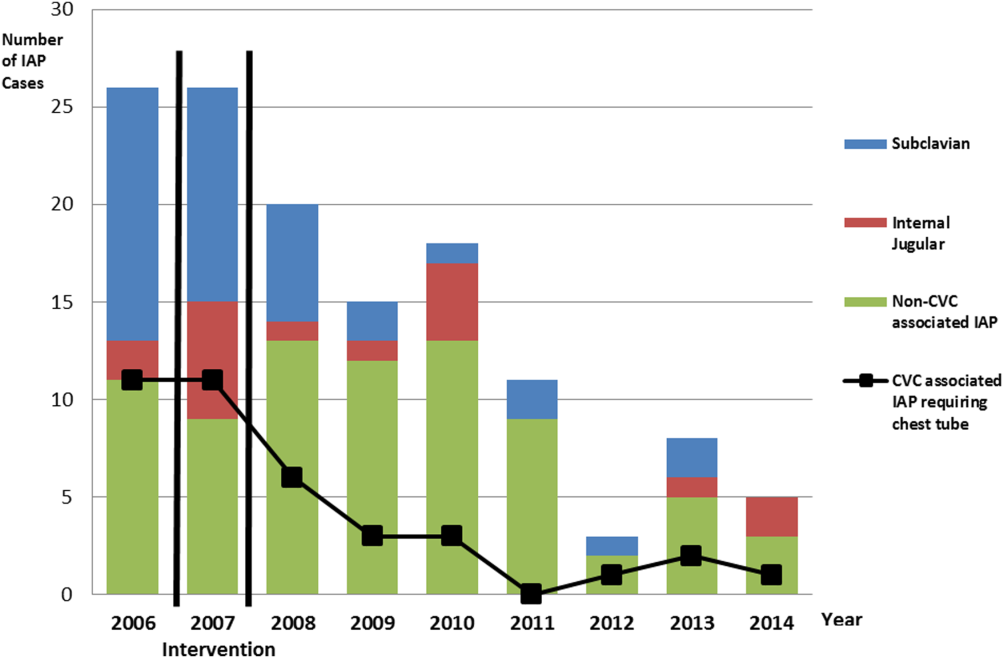

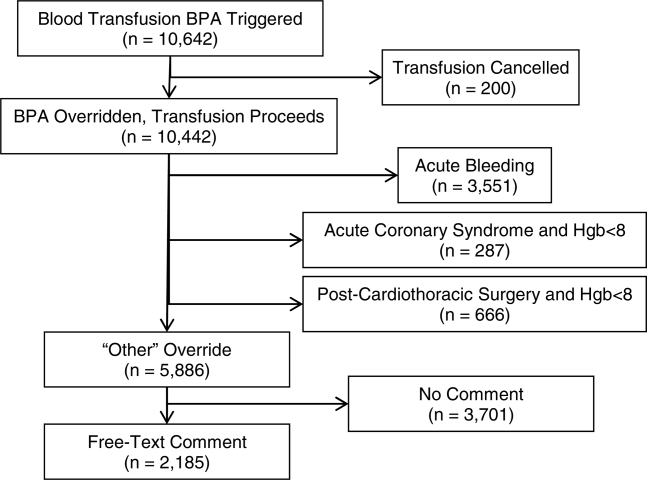

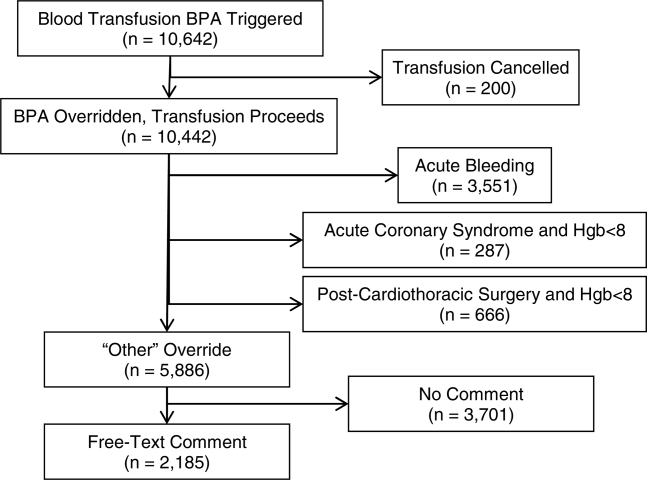

There were a total of 26 cases of IAP in 2006. Of these, 15 (58%) were associated with CVC insertion (Figure 1). The single procedure associated with the largest proportion of IAP was SC CVC insertion (11 cases, 42% of all IAP cases). Eleven CVC‐associated IAPs were significant enough to require chest tube placement. Our hospital recorded a total of 1593 CVC insertions (ICD‐9 codes 38.93 and 38.97) in 2006.

Postintervention (January 1, 2008 to December 31, 2014)

There were a total of 80 cases of IAP over 7 years, of which 24 (30%) were associated with CVC insertion. Of these, 16 required chest tube placement. In the last 4 years of the postintervention period (20112014), there were only 5 cases of CVC‐associated IAP requiring chest tube placement (Figure 1). There were a total of 12,000 CVC insertions recorded over the same period.

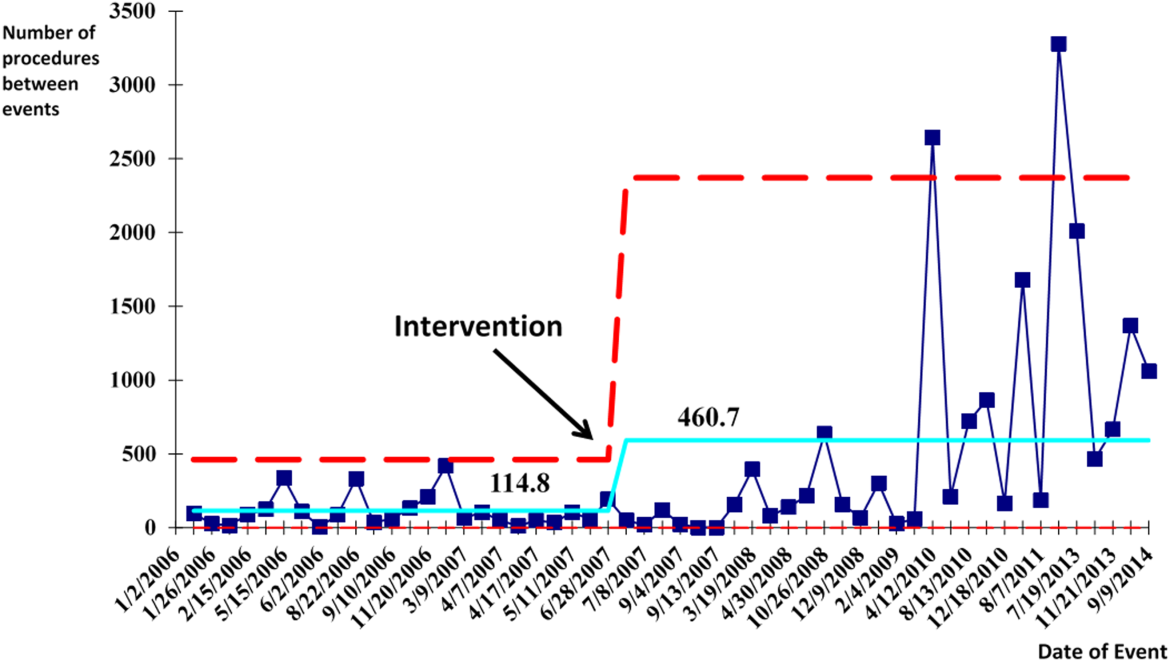

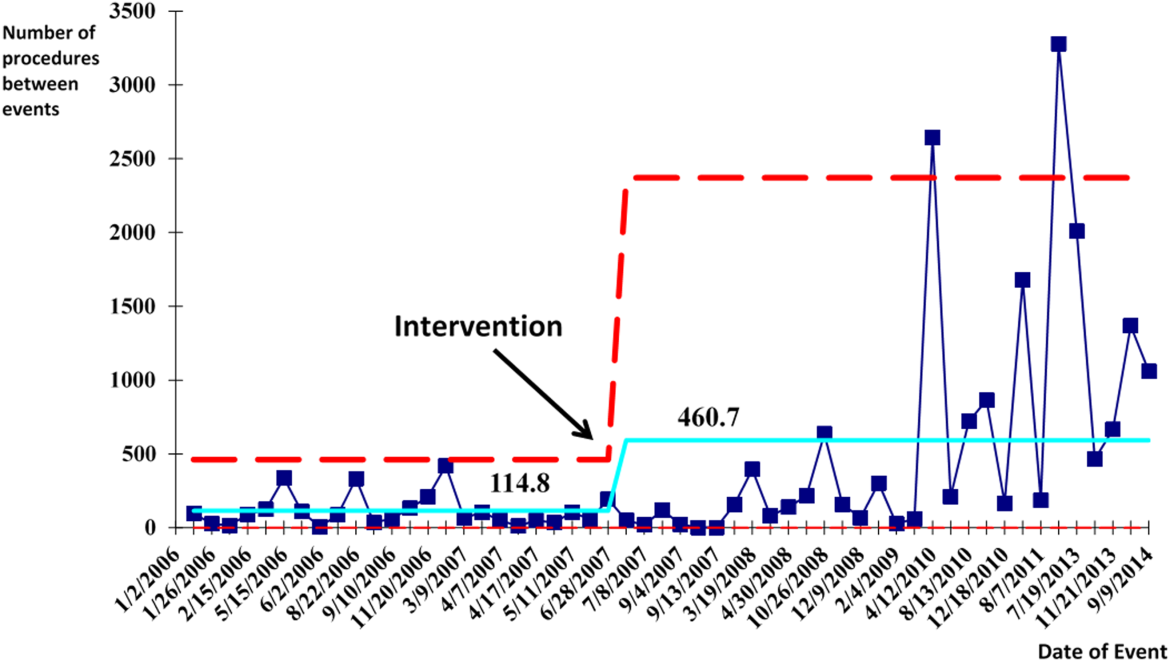

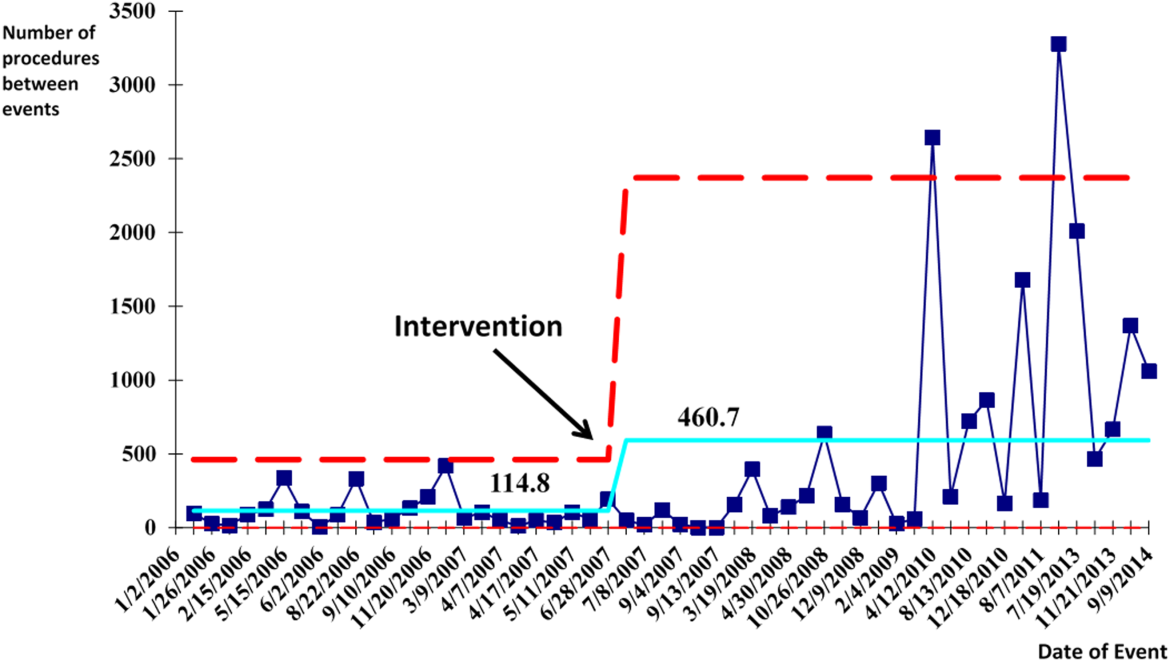

We successfully met both our short‐ and long‐term goals. Our preintervention CVC‐associated IAP rate was 0.94%, and our post‐intervention rate during 2008 was 0.44%, a short‐term reduction of 53% (P=0.088). Our average postintervention CVC‐associated IAP rate for the years 2008 through 2014 was 0.13%, a significant long‐term reduction of 86% (P<0.0001) (Table 2). The decrease in CVC‐associated IAP rates occurred despite an older patient population (P<0.001) and a higher CMI (P<0.001) in postintervention patients who received a CVC (Table 1). Special cause variation corresponding to a change in our process is demonstrated in Figure 2. The preintervention average number of procedures between IAP was 114.8 and increased to 460.7 in the postintervention period.

| Total CVC (n=95) | Subclavian (n=29) | Internal Jugular (n=58) | Femoral (n=8) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||

| Compliance to intervention | |||||||||||||

| US guided | 68.1% | 20.7% | 86.2% | 100.0% | |||||||||

| Procedure note completion | 90.4% | 93.1% | 86.2% | 100.0% | |||||||||

| Supervision | 70.2% | 77.8% | 73.1% | 87.5% | |||||||||

| Level of training | |||||||||||||

| Resident | 61.1% | 58.6% | 60.3% | 75.0% | |||||||||

| Fellow | 25.3% | 27.6% | 24.1% | 25.0% | |||||||||

| Attending | 4.2% | 6.9% | 3.4% | 0.0% | |||||||||

| Advance practitioner | 3.2% | 3.4% | 3.4% | 0.0% | |||||||||

| Unknown | 6.3% | 3.4% | 8.6% | 0.0% | |||||||||

| Supervisor type | |||||||||||||

| Resident | 3.0% | 4.8% | 2.6% | 0.0% | |||||||||

| Fellow | 54.5% | 33.3% | 57.9% | 100.0% | |||||||||

| Attending | 42.4% | 61.9% | 39.5% | 0.0% | |||||||||

| Location of CVC Placement | Internal Jugular (n=25) | Subclavian (n=25) | |||||||||||

| MICU | 32.0% | 32.0% | |||||||||||

| SICU* | 40.0% | 52.0% | |||||||||||

| Operating room | 28.0% | 16.0% | |||||||||||

| Average no. of attempts/procedure | 1.4 | 1.5 | |||||||||||

| Indications for subclavian insertion (n=25) | |||||||||||||

| Trauma/surgical site | 60.0% | ||||||||||||

| Need for additional access | 16.0% | ||||||||||||

| Unsuccessful IJ placement | 4.0% | ||||||||||||

| Unclear | 20.0% | ||||||||||||

| Iatrogenic Pneumothorax Rate (20062014) | Year | ||||||||||||

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |||||

| % of CVC insertions associated with IAP | 0.94 | 1.49 | 0.44 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.07 | ||||

| All‐cause IAP per 1,000 discharges | 1.32 | 1.29 | 0.98 | 0.71 | 0.83 | 0.49 | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.23 | ||||

| Preintervention | Postintervention | P Value | |||||||||||

| CVC‐ associated IAP short term (2006 vs 2008) | 0.94% | 0.44% | 0.088 | ||||||||||

| CVC‐associated IAP long term (2006 vs 20082014) | 0.94% | 0.13% | <0.0001 | ||||||||||

| All‐cause IAP per 1,000 discharges short term (2006 vs 2008) | 1.32 | 0.98 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||

| All‐cause IAP per 1,000 discharges long term (2006 vs 2008‐14) | 1.32 | 0.52 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||

With the decrease in CVC‐associated IAP, we also saw a decrease in our all‐cause IAP rate per 1000 discharges from 1.32 in 2006 to 0.98 in 2008. This represents a 26% short‐term reduction (P<0.0001). We also saw a decrease in our all‐cause IAP rate per 1000 discharges to 0.52 from 2008 to 2014, representing a 61% long‐term reduction (P<0.0001). This decrease in all‐cause IAP postintervention occurred despite an older patient population (P<0.01) for all discharges. Our hospital is now in the highest performance UHC quartile for all‐cause IAP in 2012 to 2014.

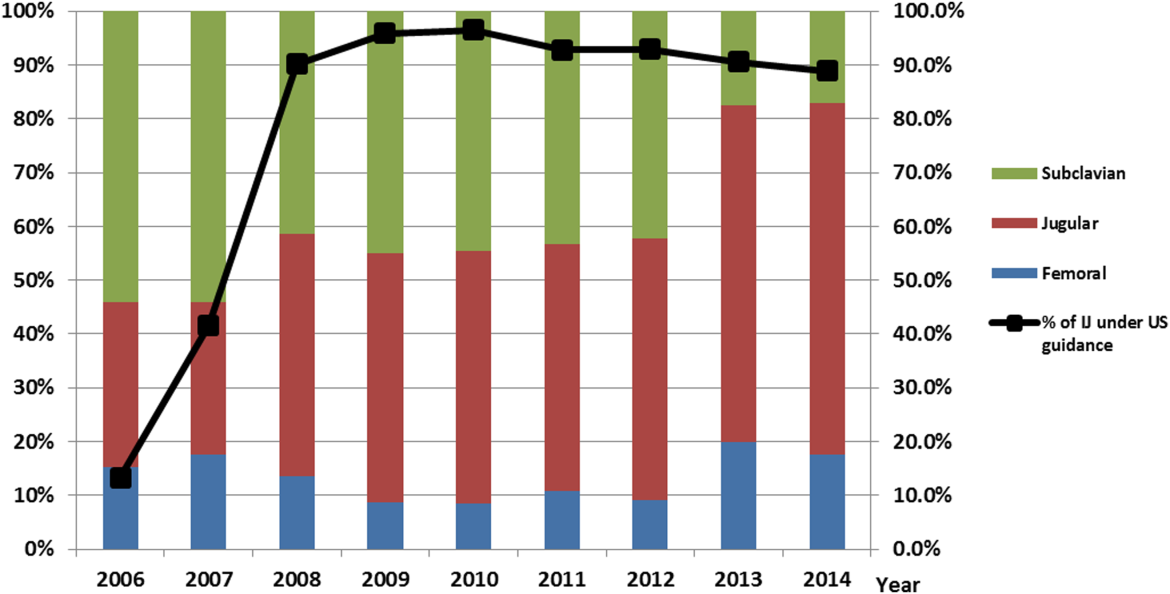

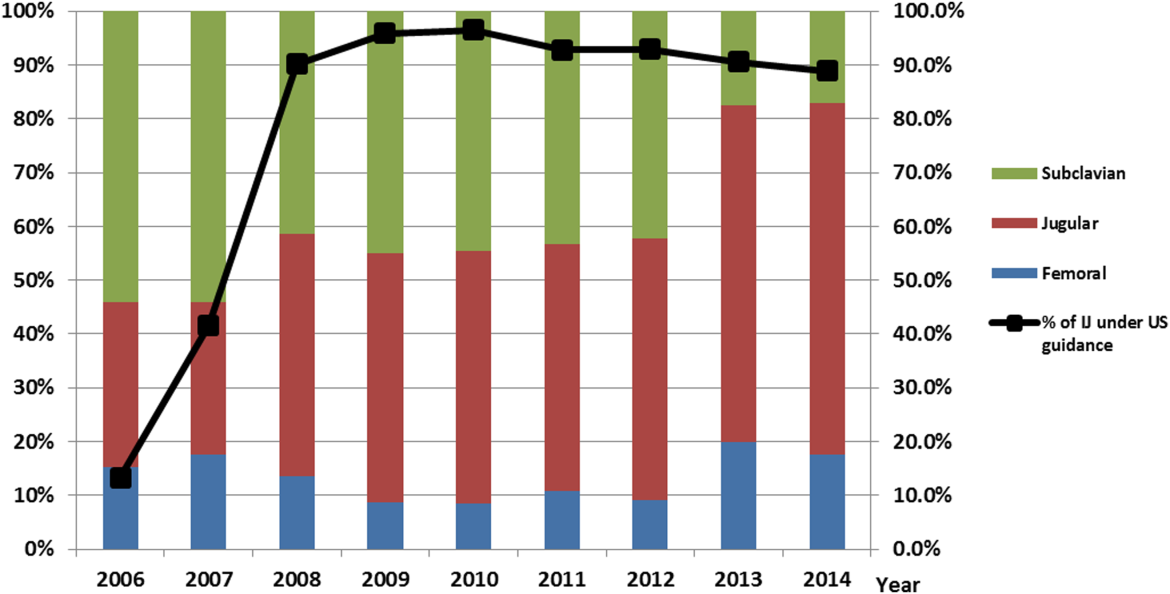

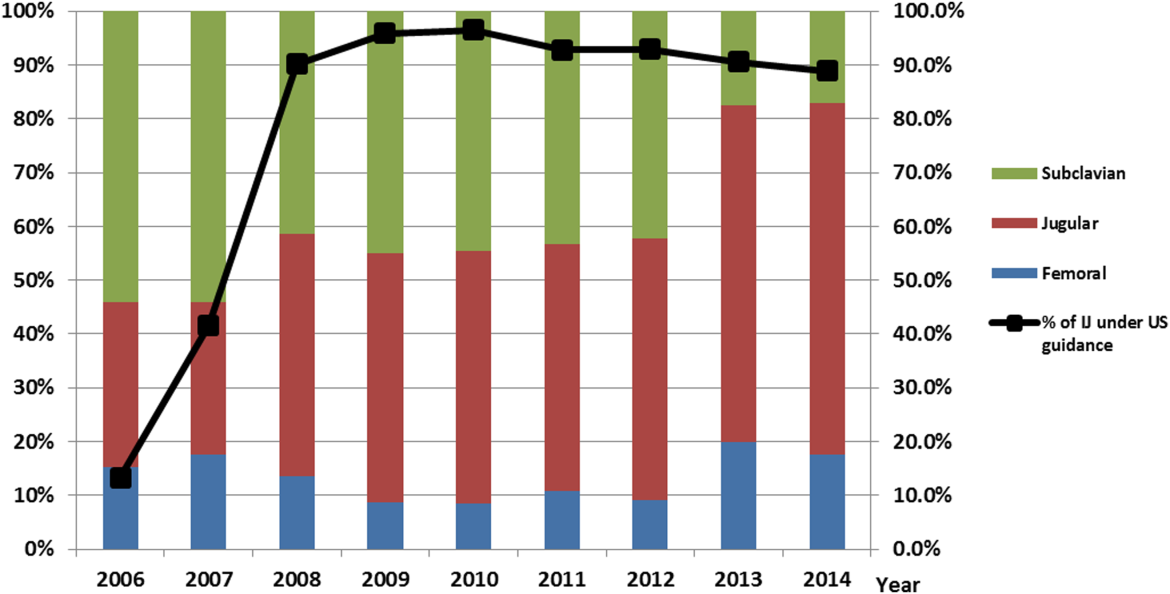

After our multifaceted intervention in 2007, there was substantially more and consistent documentation of CVC procedure notes from less than 500 in 2006 to greater than 2000 in 2009. The distribution of CVC procedure notes in the pre‐ (2006) versus postintervention (20082014) period showed a decrease in the proportion of femoral lines from 15% to 11%, increase in IJ lines from 31% to 49%, and a decrease in SC from 54% to 40% (P=0.001). The distribution of IJ CVC procedure notes in the pre‐ (2006) versus postintervention (20082014) period showed an increase in the proportion of procedures with ultrasound documentation from 13% to 93% (P<0.001) (Figure 3).

In our ICU 2014 audit, the majority of CVC lines were placed by residents under supervision (>70%), and most used the standard CVC note template to document the procedure (90%). Of the total CVC approach, 66% were IJ and 4% were SC. Eighty‐six percent used ultrasound during IJ placement. The majority of SC insertions were placed in the surgical ICU and had clear indications (80%) for placement. Of those, 75% were due to trauma (limited access to neck) or surgery (interfering with surgical site) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Summary

This quality‐improvement intervention demonstrates that a multidisciplinary team can successfully implement a multifaceted intervention that sustainably reduces the rate of IAP complications from CVC placement and improves patient safety over 7 years. We found high compliance with our intervention, which included an increase in CVC notes and documentation of ultrasound guidance. There was also an increase in the IJ approach in our postintervention period. We showed statistically significant long‐term reductions in both CVC‐associated and all‐cause IAP rates. From 2011 to 2014, there were only 5 cases of CVC‐associated IAP requiring chest tube placement. Post hoc analysis showed a statistically significant decrease in CLABSI rates (P<0.0001) from a preintervention rate of 1.6 infections per 1000 central line days to postintervention average rate of 0.68 infections per 1000 central line days. This decrease may be related to the incorporation of wide sterile barrier techniques in our CVC training workshops, checklists, and template procedure notes.

A strength of this study is the sustained significant long‐term reduction in IAP. There are few data that exist to describe sustained interventions in this area. Sustainability was achieved by integrating our interventions into ongoing programs that already existed in the hospital; we incorporated our simulation training into the existing new resident orientation, increased the availability of existing ultrasound equipment, and continued our IAP chart review through coding quality with feedback to involved services. The procedure note template continues to be easily available in our EMR, and the SC approach to CVC placement is limited to select cases.

Based on a post hoc cost‐benefit analysis, the financial benefits of decreasing the rate of IAP outweigh the costs associated with implementation of this initiative. The purchase cost for a Site‐Rite (Bard Access Systems) ultrasound machine was $18,000. The cost of materials for 1 workshop is $5000 annually. Cases from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample that were flagged by this PSI had 7.0% excess mortality, 4.4 days of excess hospitalization, and approximately $18,000 in excess hospital charges.[17, 18] Based on these data, if we had continued at our preintervention rate of CVC‐associated IAP requiring chest tube placement, we would estimate 9 additional CVC‐associated IAPs requiring chest tube insertion per year. This would result in over $180,000 of additional costs annually. Based on an initial cost of $100,000 for 4 workshops and the necessary equipment, we would have realized our cost savings in less than 1 year postintervention. These are all approximate costs, and further detailed analysis is needed.

One challenge with this intervention is the culture change away from using the SC approach, and the concern from trainees of how they would learn to perform SC CVC if needed. We would suggest dedicated SC CVC ultrasound training for those services who may need to use this approach (eg, neuroanesthesia and trauma).

Interpretation/Relation to Other Evidence

The field of implementation science can help explain why some projects are successful and others fail. We can further dissect the success of this project using an implementation science model similar to that described by French et al.[19] French et al. describe 4 behavior‐change techniques. These steps include (1) who needs to do what differently, (2) which barriers and enablers need to be addressed, (3) which intervention component could overcome the barriers and enhance enablers, and (4) how can behavior change be measured and understood. Barriers included suboptimal skills of residents, low awareness of evidence‐based guidelines, and entrenched practices inconsistent with best evidence. There was also a belief that IJ lines were more likely to become infected. Targeted behaviors needing to be done differently were the choice of CVC placement site and insertion technique. Barriers to change were assessed by asking members of the project team to explore with members of their service what led them to do CVC lines without ultrasound guidance. Enhancements focused on information provision, simulation practice, and persuasive communication. Behavior change was measured by tracking the number of IAPs, site of CVC, and documentation of technique. Continuation of these interventions based on this theoretical framework drove maintenance of gains.

We completed our main intervention planning in 90 days, and met our short‐term goal on schedule. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) advocates that such short timelines are efficient mechanisms for developing and acting on projects. Other institutions have reported on similar rapid‐cycle planning and short‐term goal setting[20]

Limitations

Our study captures the experience of a quality‐improvement team at a single academic center, and our results may not be generalizable to other institutions. Our chart review process only occurred once a case had been identified through AHRQ PSI methodology. It is possible that the PSI does not capture all cases of IAP, although we believe our coding department has a very rigorous process to look for all IAP evidence in the patient's record. We used administrative data to determine the number of hospital‐wide CVC procedures.

Our compliance data with interventions from STRIDE are based on looking for key words in procedure note documentation (so undocumented notes are not captured). To validate this, we performed a manual audit of our adherence to our intervention in 2014, and those data are consistent with the results from our STRIDE data.

Our study's observational design also cannot control for exogenous effects on physician practice relating to CVC insertion or the overall risk of IAP. Some of our decrease in complications may be from the increase in PICC line use. Nevertheless, our CVC‐associated IAP rate has decreased despite >6000 non‐PICC CVCs in our ICU over the past 5 years, and a rising CMI (18% increase in postintervention period) and older population of patients with CVC insertion (P<0.0001)

CONCLUSIONS

We are the first, to our knowledge, to report a measurable improvement in reducing IAP patient outcomes that has been sustained for over 7 years. Our hospital is in the highest performance UHC quartile for all‐cause IAP in 2012 to 2014. A multidisciplinary quality‐improvement team, focused on evidence, patient safety, and standardization, can use a multifaceted intervention to sustainably improve patient outcomes. Promoting ultrasound‐guided IJ catheterization as the CVC insertion method of choice significantly reduced our hospital's rate of CVC‐associated IAP.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge many who have contributed to this quality‐improvement project:

Irina Tokareva, Jay Lee, Kourt Bowes, and Gomathi Krishnan for data analysis; Laura Meinke for significant website curriculum; Fred Mihm, Sarah Williams, and John Kugler for leadership in ultrasound training; Kevin Tabb and Norm Rizk for hospital financial support of simulation workshops and ultrasound machines; Pooja Loftus and Helene Grossman for statistical analysis; Eric Hadhazy for data support; Joan Hendershott for cost information; Nancy Szaflarski for project management and manuscript review; and Isabella Chu for manuscript review.

Disclosures: STRIDE (Stanford Translational Research Integrated Database Environment) is a research and development project at Stanford University to create a standards‐based informatics platform supporting clinical and translational research. This STRIDE project was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through grant UL1 RR025744. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , . Significance of iatrogenic pneumothoraces. Chest. 1994;105(4):1147–1150.

- , , , , , . How to avoid and manage a pneumothorax. J Vasc Access. 2006;7(1):7–14.

- , , , . Iatrogenic pneumothorax: etiology, incidence and risk factors. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;57(5):286–290.

- , , , et al. Real‐time ultrasound‐guided catheterisation of the internal jugular vein: a prospective comparison with the landmark technique in critical care patients. Crit Care. 2006;10(6):R162.

- , , . Safe placement of central venous catheters: a measured approach. J Intens Care Med. 2011;26(6):392–396.

- , , , . Reducing iatrogenic risk in thoracentesis: establishing best practice via experiential training in a zero‐risk environment. Chest. 2009;135(5):1315–1320.

- , , , , , . Use of simulation‐based education to improve outcomes of central venous catheterization: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acad Med. 2011;86(9):1137–1147.

- , , , , , . A prerotational, simulation‐based workshop improves the safety of central venous catheter insertion: results of a successful internal medicine house staff training program. Chest. 2011;140(3):652–658.

- , , , , . Linking residency training effectiveness to clinical outcomes: a quality improvement approach. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010;36(5):203–208.

- , , , et al. Education of physicians‐in‐training can decrease the risk for vascular catheter infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(8):641–648.

- , , , et al. A multidisciplinary approach to reduce central line‐associated bloodstream infections. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2013;39(2):61–69.

- , , , et al. Validity of selected Patient Safety Indicators: opportunities and concerns. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212(6):924–934.

- , , , et al. Cases of iatrogenic pneumothorax can be identified from ICD‐9‐CM coded data. Am J Med Qual. 2010;25(3):218–224.

- , , , , ; SQUIRE development group. Publication guidelines for quality improvement studies in health care: evolution of the SQUIRE project. BMJ. 2009;338:a3152.

- . The Quality Toolbox. 2nd ed. Milwaukee, WI: ASQ Quality Press; 2005.

- , , , . STRIDE—an integrated standards‐based translational research informatics platform. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2009;2009:391–395.

- , , . Accidental iatrogenic pneumothorax in hospitalized patients. Med Care. 2006;44(2):182–186.

- , . Excess length of stay, charges, and mortality attributable to medical injuries during hospitalization. JAMA. 2003;290(14):1868–1874.

- , , , et al. Developing theory‐informed behaviour change interventions to implement evidence into practice: a systematic approach using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Implement Sci. 2012;7:38.

- , . Using rapid‐cycle quality improvement methodology to reduce feeding tubes in patients with advanced dementia: before and after study. BMJ. 2004;329(7464):491–494.

Iatrogenic pneumothorax (IAP) is a complication of invasive procedures that is associated with substantial morbidity and some mortality.[1] IAP is often avoidable, and in many cases can be prevented through adherence to evidence‐based guidelines and procedural techniques known to reduce the incidence of IAP.[2] IAP may occur with a subclavian (SC) or internal jugular (IJ) central venous catheter (CVC) insertion, but is more frequently associated with the SC approach.[3] Ultrasound guidance during IJ CVC insertion is associated with a lower risk as compared to guidance by anatomical landmarks.[4, 5] Other bedside procedures that are known to cause IAP include thoracentesis. This risk can also be reduced with the use of ultrasound guidance.[6]

Including simulation in training for CVC insertion has been demonstrated in meta‐analyses to improve both learner outcomes, including simulator performance and perceived confidence, and patient outcomes, including fewer failed CVC attempts and reduced incidence of IAP.[7] Even brief simulation workshops lasting less than two hours can improve patient safety during CVC insertion.[8]

The implementation of ultrasound‐based simulation and improved adherence to the actual use of ultrasound at the bedside can be motivated by tying competency‐based educational objectives (eg, CVC insertion) to clinical outcomes (ie, rates of IAP) and tracking both as part of a continuous quality‐improvement cycle.[9] Adherence to best practices for CVC insertion can also be improved through standardizing hospital‐wide policies and hands‐on training.[10] Involving many stakeholders, including nurses, physicians, nurse practioners and physician assistants, in a multidisciplinary team has been shown to help alter entrenched behaviors and reduce the incidence of central‐line associated bloodstream infections through long‐term adherence to evidence‐based interventions.[11]

LOCAL PROBLEM

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has designed Patient Safety Indicators (PSIs) (

Our hospital is a member of the University HealthSystem Consortium (UHC) (

Despite this, the PSI can highlight areas where quality‐improvement efforts might be best directed. In 2005 and 2006, our hospital was ranked within the lowest UHC performance quartile for all‐cause IAP PSI.

During FY 2006 (September 2005August 2006), root‐cause analysis on cases of IAP at our hospital found that CVC insertion (40%) was the most common procedure associated with IAP, with SC insertion causing 69% of CVC‐associated IAP. Other common procedures associated with IAP were operative/pacemaker (30%), thoracentesis (25%), and ventilator associated (5%). Ultrasound was not used in 2/5 cases of IJ CVC placement and 3/5 thoracentesis cases. Only 44% of CVC insertions had a procedure note.

Intended Improvement/Study Question

Our team set out to plan and implement a set of multifaceted interventions within 90 days. The short‐term goal was a 50% reduction in the CVC IAP and all‐cause IAP rate within 18 months, and the long‐term goal was sustained reduction of CVC IAP and all‐cause IAP rate.

METHODS

The format of this article is based on the standards for quality‐improvement reporting excellence guidelines for the reporting of studies on the effectiveness of quality‐improvement interventions.[14]

Setting

Stanford University Medical Center is an academic medical center with 465 beds and over 25,000 inpatient admissions per year, providing both general acute care services and tertiary medical care. Residents perform CVC bedside procedures when central venous access is needed, in the intensive care unit (ICU), operating room (OR), and inpatient units. Prior to this project, ultrasound equipment was only available in the emergency department (ED) and ICUs. There was no formal CVC procedure supervision policy, CVC training curriculum, and procedure note templates for documentation of CVC insertion.

Planning the Interventions

A multidisciplinary quality‐improvement team met weekly during the 90‐day design period from January 2007 to March 2007. Our team included representatives from the departments of medicine, anesthesia and critical care, surgery, nursing, and emergency medicine. We also partnered with our institution's clinical and administrative leaders, experts in simulation, and the hospital quality department.

We hypothesized that a standardized set of education and training interventions promoting ultrasound‐guided IJ CVC insertion as the method of choice at our hospital would significantly reduce our rate of CVC‐associated IAP. Our multifaceted intervention included: (1) clinical and documentation standards based on evidence, (2) cognitive aids, (3) simulation training, (4) purchase and deployment of ultrasound equipment, and (5) feedback to clinical services.

Our team followed the define, measure, analyze, improve, control (DMAIC) framework.[15] We set interval goals with target completion dates throughout the 90‐day period, identified owners of each goal, and tracked progress with a shared spreadsheet.

In the 90‐day intervention, we accomplished the following: (1) conducted root‐cause analysis of IAP cases for fiscal year 2006, (2) created clinical and documentation standards around CVC placement, (3) created cognitive aids and procedure note templates, (4) developed simulation training courses, and (5) requested purchase of additional ultrasound equipment.

Data Collection

To evaluate our progress in reducing the rates of IAP, we tracked the incidence of IAP using UHC and AHRQ PSI methodology. In collaboration with our hospital's quality department, we manually reviewed every PSI‐identified case of IAP. This review has focused on identifying whether or not pneumothorax actually occurred, and whether it was associated with CVC insertion. For those associated with CVC, data were collected for patient location and service, the procedure site, whether ultrasound was used, whether a chest tube was required, and the final disposition of the patient.

Demographic data (age, gender, case mix index [CMI]) shown in Table 1 were obtained through MIDAS+ Solutions (Tucson, Arizona), a proprietary database that contains healthcare management coded data. Total hospital CVC insertion rates were calculated using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD‐9) coding for 38.93 and 38.97. ICU central lineassociated blood stream infections (CLABSI) data were obtained from internal collection by our infection control team. Number and location of CVCs placed in the ICU data were obtained from nursing flow sheets in our electronic medical record (EMR). Cost information was provided by our finance department using internal accounting.

| Patients With CVC Insertion | Year | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

| |||||||||

| Age, y (mean) | 55.0 | 55.5 | 55.0 | 57.0 | 56.5 | 58.5 | 57.5 | 59.0 | 58.5 |

| % female | 47.0 | 49.5 | 47.0 | 48.8 | 46.2 | 46.1 | 45.7 | 46.2 | 45.7 |

| Case‐mix index | 3.08 | 3.35 | 3.21 | 3.40 | 3.71 | 3.91 | 3.92 | 3.92 | 4.08 |

| Total no. of CVCs/year* | 1,593 | 1,141 | 1,589 | 2,250 | 2,441 | 2,774 | 2,754 | 2,722 | 2,845 |

| No. of CVCs/year in ICU | NA | NA | NA | 1,502 | 1,357 | 1,345 | 1,316 | 1,421 | 1,590 |

| No. of subclavians/year in ICU | NA | NA | NA | 167 | 75 | 70 | 83 | 75 | 97 |

| No. of IJs/year in ICU | NA | NA | NA | 898 | 773 | 681 | 677 | 713 | 876 |

| No. of femorals/year in ICU | NA | NA | NA | 212 | 152 | 203 | 171 | 198 | 206 |

| No. of PICCs/year in ICU | NA | NA | NA | 225 | 357 | 391 | 385 | 435 | 411 |

| Preintervention (2006) | Postintervention (20082014) | P Value | |||||||

| Age, y (mean) | 55.2 | 58.7 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| % female | 47.0% | 46.4% | 0.642 | ||||||

| Case‐mix index | 3.08 | 3.73 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| CVC insertion rate | 8.1% | 11.4% | <0.0001 | ||||||

| All Inpatients | Year | ||||||||

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

| Age, y (mean) | 57.1 | 57.2 | 56.8 | 57.2 | 57.5 | 58.0 | 58.0 | 57.9 | 58.3 |

| % female | 51.6 | 51.2 | 52.4 | 51.7 | 51.1 | 51.5 | 50.3 | 49.9 | 50.1 |

| Case‐mix index | 1.86 | 1.98 | 1.96 | 1.99 | 1.96 | 2.02 | 2.03 | 2.07 | 2.23 |

| Preintervention (2006) | Postintervention (20082014) | P Value | |||||||

| Age, y (mean) | 57.1 | 57.6 | <0.01 | ||||||

| % female | 51.6% | 50.9% | 0.07 | ||||||

| Case‐mix index | 1.86 | 2.03 | 0.13 | ||||||

| Central Line‐Associated Bloodstream Infections per 1,000 Central Line Days | |||||||||

| Preintervention | Postintervention | P Value | |||||||

| Short term (2006 vs 2008) | 1.8 | 0.60 | 0.004 | ||||||

| Long term (2006 vs 20082014) | 1.8 | 0.68 | <0.0001 | ||||||

The project granted a Notice of Determination of Approval from the Stanford Administrative Panels for the Protection of Human Subjects (institutional review board).

Methods of Evaluation/Analysis

For the purpose of this analysis, the preintervention period was defined as January 1, 2006 through December 31, 2006, our first year of IAP case review. We defined the intervention period as January 1, 2007 through December 31, 2007, during which we planned and implemented hospital‐wide standardization of CVC insertion practices and incorporated CVC insertion training simulation into resident orientation in July 2007. The postintervention period was defined as January 1, 2008 through December 31, 2014.

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). [2] tests were used to determine statistical differences in pre‐ versus postintervention patient demographic data (age, gender, CMI), CVC insertion rates, and CLABSI rates. Because IAP is a rare event, a statistical process control g‐chart was created using QI Macros (KnowWare International, Inc., Denver, CO) to show the number of CVC procedures between IAP. [2] and Fisher exact tests were used to determine statistical differences in CVC anatomic location and use of ultrasound pre‐ and postintervention. A 2‐sided Z test to show a difference in proportions was used to determine statistical differences in CVC‐related IAP rate and all‐cause IAP rate pre‐ and postintervention.

Measuring Adherence to Intervention

Location of CVC Placement and Ultrasound Guidance Pre‐ Versus Postintervention

We utilized the Stanford Clinical Informatics Center (SCCI) services for obtaining counts of patients. Custom queries were performed on SCCI's Stanford Translational Research Integrated Database Environment (STRIDE) platform[16] to search Stanford Hospital electronic heath records for patients. This search primarily involved getting counts for the number of patients with clinical notes that contained the keywords of interest. To identify documentation for placement of CVC from 2006 to 2014, procedure or operative notes containing the words central line or CVC were counted. Further subcounts were obtained by searching for additional keywords such as PICC [peripherally inserted central catheters], femoral, jugular, subclavian, and ultrasound.

Adherence to Intervention in the ICU in 2014

A total of 100 charts were reviewed from patients in our medical and surgical ICU with a CVC in 2014 to evaluate the current trend of central line placement and sustainability of our intervention. Fifty charts were initially randomly selected from the ICU cohort. For those who had multiple lines placed, only the first line was reviewed. Because the initial audit did not provide enough SC lines and we wanted to review more IJ lines, we randomly selected an additional 25 patients who had SC and 25 patients who had IJ to review. The following was collected during chart review: primary team, location of line placement, usage of ultrasound, usage of standard procedure template, supervision, level of training for supervisor, and level of training for staff who performed procedure.

Outcomes

The rate of CVC‐associated IAP was calculated as the total number of IAPs attributed to CVCs divided by the total number of CVCs inserted determined by ICD‐9 coding for 38.93 and 38.97. The total IAP rate was calculated as the total number of IAP/1000 discharges.

RESULTS

Interventions

Our team began the intervention in early 2007 with promotion of ultrasound‐guided IJ catheterization. Clinical exceptions included: (1) trauma or code situations where access to the neck is limited, (2) suspected or confirmed neck injuries, (3) presence of a tracheostomy, and (4) bilateral internal jugular sites unsuitable for catheterization.

Our hospital adopted new formal CVC insertion policies consistent with the above training and education efforts. All physicians were required to document CVC insertions using the template available in the EMR. To be certified to perform CVC insertion independently, trainee physicians were required to complete the simulation training and successfully place a minimum of 5 CVCs directly supervised by an already‐certified physician. This was consistent with the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education suggested minimum requirement in 2007. In our critical care units, all CVC insertions must be supervised by an ICU fellow or attending.

To reinforce the on‐the‐ground work by our physician leaders, we created 2 education tools to embed best practices into our CVC insertion workflow. A checklist with best practices for CVC insertion that was distributed throughout the hospital via central line kits and educational flyers, and a CVC insertion procedure note template consistent with California Department of Public Health documentation requirements was made available in our EMR.

In June 2007, we integrated CVC insertion simulation training into procedure workshops required for all medicine, surgery, anesthesia, and emergency medicine trainees during their intern year. These workshops promoted ultrasound‐guided IJ catheterization and supporting evidence for the new IJ site preference. Training sessions were 2 to 3 hours, and included a demonstration of best‐practice CVC insertion, as well as training with simulation models supervised by an instructor using a standardized CVC checklist. These trainings used both the Blue Phantom human torso model (

Hospital administration provided funds to purchase ultrasound machines for patient units such as medicine, cardiology, ED, and ICU). A total of 4 Site‐Rite (Bard Access Systems, Inc., Salt Lake City, UT) ultrasounds were purchased in 2007. The hospital has continued to purchase ultrasound units yearly, and had 53 ultrasound units in 2014

Cases of IAP were continuously reviewed throughout the intervention period. Based on their higher CVC‐associated IAP rates, the ORs and catheterization lab were identified as having opportunities for improvement. In 2008, Hospital quality‐improvement leadership met with physician leaders in these areas to review their CVC‐related IAP data and to discuss strategies to reduce their IAP rates. These strategies included lessons learned from other services that had successfully decreased their IAP rates.

To sustain our gains, we continue to review all IAP through our coding quality, clinical documentation, quality reporting departments, and peer review. We have implemented other strategies to decrease IAP, such as the use of ultrasound guidance for bedside thoracentesis procedures, which became possible after the availability of more ultrasound devices. Training for ultrasound‐guided thoracentesis was done by our procedure‐team attending during supervision of residents.

Outcomes

Preintervention (January 1, 2006 to December 31, 2006)

There were a total of 26 cases of IAP in 2006. Of these, 15 (58%) were associated with CVC insertion (Figure 1). The single procedure associated with the largest proportion of IAP was SC CVC insertion (11 cases, 42% of all IAP cases). Eleven CVC‐associated IAPs were significant enough to require chest tube placement. Our hospital recorded a total of 1593 CVC insertions (ICD‐9 codes 38.93 and 38.97) in 2006.

Postintervention (January 1, 2008 to December 31, 2014)

There were a total of 80 cases of IAP over 7 years, of which 24 (30%) were associated with CVC insertion. Of these, 16 required chest tube placement. In the last 4 years of the postintervention period (20112014), there were only 5 cases of CVC‐associated IAP requiring chest tube placement (Figure 1). There were a total of 12,000 CVC insertions recorded over the same period.

We successfully met both our short‐ and long‐term goals. Our preintervention CVC‐associated IAP rate was 0.94%, and our post‐intervention rate during 2008 was 0.44%, a short‐term reduction of 53% (P=0.088). Our average postintervention CVC‐associated IAP rate for the years 2008 through 2014 was 0.13%, a significant long‐term reduction of 86% (P<0.0001) (Table 2). The decrease in CVC‐associated IAP rates occurred despite an older patient population (P<0.001) and a higher CMI (P<0.001) in postintervention patients who received a CVC (Table 1). Special cause variation corresponding to a change in our process is demonstrated in Figure 2. The preintervention average number of procedures between IAP was 114.8 and increased to 460.7 in the postintervention period.

| Total CVC (n=95) | Subclavian (n=29) | Internal Jugular (n=58) | Femoral (n=8) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||

| Compliance to intervention | |||||||||||||

| US guided | 68.1% | 20.7% | 86.2% | 100.0% | |||||||||

| Procedure note completion | 90.4% | 93.1% | 86.2% | 100.0% | |||||||||

| Supervision | 70.2% | 77.8% | 73.1% | 87.5% | |||||||||

| Level of training | |||||||||||||

| Resident | 61.1% | 58.6% | 60.3% | 75.0% | |||||||||

| Fellow | 25.3% | 27.6% | 24.1% | 25.0% | |||||||||

| Attending | 4.2% | 6.9% | 3.4% | 0.0% | |||||||||

| Advance practitioner | 3.2% | 3.4% | 3.4% | 0.0% | |||||||||

| Unknown | 6.3% | 3.4% | 8.6% | 0.0% | |||||||||

| Supervisor type | |||||||||||||

| Resident | 3.0% | 4.8% | 2.6% | 0.0% | |||||||||

| Fellow | 54.5% | 33.3% | 57.9% | 100.0% | |||||||||

| Attending | 42.4% | 61.9% | 39.5% | 0.0% | |||||||||

| Location of CVC Placement | Internal Jugular (n=25) | Subclavian (n=25) | |||||||||||

| MICU | 32.0% | 32.0% | |||||||||||

| SICU* | 40.0% | 52.0% | |||||||||||

| Operating room | 28.0% | 16.0% | |||||||||||

| Average no. of attempts/procedure | 1.4 | 1.5 | |||||||||||

| Indications for subclavian insertion (n=25) | |||||||||||||

| Trauma/surgical site | 60.0% | ||||||||||||

| Need for additional access | 16.0% | ||||||||||||

| Unsuccessful IJ placement | 4.0% | ||||||||||||

| Unclear | 20.0% | ||||||||||||

| Iatrogenic Pneumothorax Rate (20062014) | Year | ||||||||||||

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |||||

| % of CVC insertions associated with IAP | 0.94 | 1.49 | 0.44 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.07 | ||||

| All‐cause IAP per 1,000 discharges | 1.32 | 1.29 | 0.98 | 0.71 | 0.83 | 0.49 | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.23 | ||||

| Preintervention | Postintervention | P Value | |||||||||||

| CVC‐ associated IAP short term (2006 vs 2008) | 0.94% | 0.44% | 0.088 | ||||||||||

| CVC‐associated IAP long term (2006 vs 20082014) | 0.94% | 0.13% | <0.0001 | ||||||||||

| All‐cause IAP per 1,000 discharges short term (2006 vs 2008) | 1.32 | 0.98 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||

| All‐cause IAP per 1,000 discharges long term (2006 vs 2008‐14) | 1.32 | 0.52 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||

With the decrease in CVC‐associated IAP, we also saw a decrease in our all‐cause IAP rate per 1000 discharges from 1.32 in 2006 to 0.98 in 2008. This represents a 26% short‐term reduction (P<0.0001). We also saw a decrease in our all‐cause IAP rate per 1000 discharges to 0.52 from 2008 to 2014, representing a 61% long‐term reduction (P<0.0001). This decrease in all‐cause IAP postintervention occurred despite an older patient population (P<0.01) for all discharges. Our hospital is now in the highest performance UHC quartile for all‐cause IAP in 2012 to 2014.

After our multifaceted intervention in 2007, there was substantially more and consistent documentation of CVC procedure notes from less than 500 in 2006 to greater than 2000 in 2009. The distribution of CVC procedure notes in the pre‐ (2006) versus postintervention (20082014) period showed a decrease in the proportion of femoral lines from 15% to 11%, increase in IJ lines from 31% to 49%, and a decrease in SC from 54% to 40% (P=0.001). The distribution of IJ CVC procedure notes in the pre‐ (2006) versus postintervention (20082014) period showed an increase in the proportion of procedures with ultrasound documentation from 13% to 93% (P<0.001) (Figure 3).

In our ICU 2014 audit, the majority of CVC lines were placed by residents under supervision (>70%), and most used the standard CVC note template to document the procedure (90%). Of the total CVC approach, 66% were IJ and 4% were SC. Eighty‐six percent used ultrasound during IJ placement. The majority of SC insertions were placed in the surgical ICU and had clear indications (80%) for placement. Of those, 75% were due to trauma (limited access to neck) or surgery (interfering with surgical site) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Summary

This quality‐improvement intervention demonstrates that a multidisciplinary team can successfully implement a multifaceted intervention that sustainably reduces the rate of IAP complications from CVC placement and improves patient safety over 7 years. We found high compliance with our intervention, which included an increase in CVC notes and documentation of ultrasound guidance. There was also an increase in the IJ approach in our postintervention period. We showed statistically significant long‐term reductions in both CVC‐associated and all‐cause IAP rates. From 2011 to 2014, there were only 5 cases of CVC‐associated IAP requiring chest tube placement. Post hoc analysis showed a statistically significant decrease in CLABSI rates (P<0.0001) from a preintervention rate of 1.6 infections per 1000 central line days to postintervention average rate of 0.68 infections per 1000 central line days. This decrease may be related to the incorporation of wide sterile barrier techniques in our CVC training workshops, checklists, and template procedure notes.

A strength of this study is the sustained significant long‐term reduction in IAP. There are few data that exist to describe sustained interventions in this area. Sustainability was achieved by integrating our interventions into ongoing programs that already existed in the hospital; we incorporated our simulation training into the existing new resident orientation, increased the availability of existing ultrasound equipment, and continued our IAP chart review through coding quality with feedback to involved services. The procedure note template continues to be easily available in our EMR, and the SC approach to CVC placement is limited to select cases.

Based on a post hoc cost‐benefit analysis, the financial benefits of decreasing the rate of IAP outweigh the costs associated with implementation of this initiative. The purchase cost for a Site‐Rite (Bard Access Systems) ultrasound machine was $18,000. The cost of materials for 1 workshop is $5000 annually. Cases from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample that were flagged by this PSI had 7.0% excess mortality, 4.4 days of excess hospitalization, and approximately $18,000 in excess hospital charges.[17, 18] Based on these data, if we had continued at our preintervention rate of CVC‐associated IAP requiring chest tube placement, we would estimate 9 additional CVC‐associated IAPs requiring chest tube insertion per year. This would result in over $180,000 of additional costs annually. Based on an initial cost of $100,000 for 4 workshops and the necessary equipment, we would have realized our cost savings in less than 1 year postintervention. These are all approximate costs, and further detailed analysis is needed.

One challenge with this intervention is the culture change away from using the SC approach, and the concern from trainees of how they would learn to perform SC CVC if needed. We would suggest dedicated SC CVC ultrasound training for those services who may need to use this approach (eg, neuroanesthesia and trauma).

Interpretation/Relation to Other Evidence

The field of implementation science can help explain why some projects are successful and others fail. We can further dissect the success of this project using an implementation science model similar to that described by French et al.[19] French et al. describe 4 behavior‐change techniques. These steps include (1) who needs to do what differently, (2) which barriers and enablers need to be addressed, (3) which intervention component could overcome the barriers and enhance enablers, and (4) how can behavior change be measured and understood. Barriers included suboptimal skills of residents, low awareness of evidence‐based guidelines, and entrenched practices inconsistent with best evidence. There was also a belief that IJ lines were more likely to become infected. Targeted behaviors needing to be done differently were the choice of CVC placement site and insertion technique. Barriers to change were assessed by asking members of the project team to explore with members of their service what led them to do CVC lines without ultrasound guidance. Enhancements focused on information provision, simulation practice, and persuasive communication. Behavior change was measured by tracking the number of IAPs, site of CVC, and documentation of technique. Continuation of these interventions based on this theoretical framework drove maintenance of gains.

We completed our main intervention planning in 90 days, and met our short‐term goal on schedule. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) advocates that such short timelines are efficient mechanisms for developing and acting on projects. Other institutions have reported on similar rapid‐cycle planning and short‐term goal setting[20]

Limitations

Our study captures the experience of a quality‐improvement team at a single academic center, and our results may not be generalizable to other institutions. Our chart review process only occurred once a case had been identified through AHRQ PSI methodology. It is possible that the PSI does not capture all cases of IAP, although we believe our coding department has a very rigorous process to look for all IAP evidence in the patient's record. We used administrative data to determine the number of hospital‐wide CVC procedures.

Our compliance data with interventions from STRIDE are based on looking for key words in procedure note documentation (so undocumented notes are not captured). To validate this, we performed a manual audit of our adherence to our intervention in 2014, and those data are consistent with the results from our STRIDE data.

Our study's observational design also cannot control for exogenous effects on physician practice relating to CVC insertion or the overall risk of IAP. Some of our decrease in complications may be from the increase in PICC line use. Nevertheless, our CVC‐associated IAP rate has decreased despite >6000 non‐PICC CVCs in our ICU over the past 5 years, and a rising CMI (18% increase in postintervention period) and older population of patients with CVC insertion (P<0.0001)

CONCLUSIONS

We are the first, to our knowledge, to report a measurable improvement in reducing IAP patient outcomes that has been sustained for over 7 years. Our hospital is in the highest performance UHC quartile for all‐cause IAP in 2012 to 2014. A multidisciplinary quality‐improvement team, focused on evidence, patient safety, and standardization, can use a multifaceted intervention to sustainably improve patient outcomes. Promoting ultrasound‐guided IJ catheterization as the CVC insertion method of choice significantly reduced our hospital's rate of CVC‐associated IAP.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge many who have contributed to this quality‐improvement project:

Irina Tokareva, Jay Lee, Kourt Bowes, and Gomathi Krishnan for data analysis; Laura Meinke for significant website curriculum; Fred Mihm, Sarah Williams, and John Kugler for leadership in ultrasound training; Kevin Tabb and Norm Rizk for hospital financial support of simulation workshops and ultrasound machines; Pooja Loftus and Helene Grossman for statistical analysis; Eric Hadhazy for data support; Joan Hendershott for cost information; Nancy Szaflarski for project management and manuscript review; and Isabella Chu for manuscript review.

Disclosures: STRIDE (Stanford Translational Research Integrated Database Environment) is a research and development project at Stanford University to create a standards‐based informatics platform supporting clinical and translational research. This STRIDE project was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through grant UL1 RR025744. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Iatrogenic pneumothorax (IAP) is a complication of invasive procedures that is associated with substantial morbidity and some mortality.[1] IAP is often avoidable, and in many cases can be prevented through adherence to evidence‐based guidelines and procedural techniques known to reduce the incidence of IAP.[2] IAP may occur with a subclavian (SC) or internal jugular (IJ) central venous catheter (CVC) insertion, but is more frequently associated with the SC approach.[3] Ultrasound guidance during IJ CVC insertion is associated with a lower risk as compared to guidance by anatomical landmarks.[4, 5] Other bedside procedures that are known to cause IAP include thoracentesis. This risk can also be reduced with the use of ultrasound guidance.[6]

Including simulation in training for CVC insertion has been demonstrated in meta‐analyses to improve both learner outcomes, including simulator performance and perceived confidence, and patient outcomes, including fewer failed CVC attempts and reduced incidence of IAP.[7] Even brief simulation workshops lasting less than two hours can improve patient safety during CVC insertion.[8]

The implementation of ultrasound‐based simulation and improved adherence to the actual use of ultrasound at the bedside can be motivated by tying competency‐based educational objectives (eg, CVC insertion) to clinical outcomes (ie, rates of IAP) and tracking both as part of a continuous quality‐improvement cycle.[9] Adherence to best practices for CVC insertion can also be improved through standardizing hospital‐wide policies and hands‐on training.[10] Involving many stakeholders, including nurses, physicians, nurse practioners and physician assistants, in a multidisciplinary team has been shown to help alter entrenched behaviors and reduce the incidence of central‐line associated bloodstream infections through long‐term adherence to evidence‐based interventions.[11]

LOCAL PROBLEM

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has designed Patient Safety Indicators (PSIs) (

Our hospital is a member of the University HealthSystem Consortium (UHC) (

Despite this, the PSI can highlight areas where quality‐improvement efforts might be best directed. In 2005 and 2006, our hospital was ranked within the lowest UHC performance quartile for all‐cause IAP PSI.

During FY 2006 (September 2005August 2006), root‐cause analysis on cases of IAP at our hospital found that CVC insertion (40%) was the most common procedure associated with IAP, with SC insertion causing 69% of CVC‐associated IAP. Other common procedures associated with IAP were operative/pacemaker (30%), thoracentesis (25%), and ventilator associated (5%). Ultrasound was not used in 2/5 cases of IJ CVC placement and 3/5 thoracentesis cases. Only 44% of CVC insertions had a procedure note.

Intended Improvement/Study Question

Our team set out to plan and implement a set of multifaceted interventions within 90 days. The short‐term goal was a 50% reduction in the CVC IAP and all‐cause IAP rate within 18 months, and the long‐term goal was sustained reduction of CVC IAP and all‐cause IAP rate.

METHODS

The format of this article is based on the standards for quality‐improvement reporting excellence guidelines for the reporting of studies on the effectiveness of quality‐improvement interventions.[14]

Setting

Stanford University Medical Center is an academic medical center with 465 beds and over 25,000 inpatient admissions per year, providing both general acute care services and tertiary medical care. Residents perform CVC bedside procedures when central venous access is needed, in the intensive care unit (ICU), operating room (OR), and inpatient units. Prior to this project, ultrasound equipment was only available in the emergency department (ED) and ICUs. There was no formal CVC procedure supervision policy, CVC training curriculum, and procedure note templates for documentation of CVC insertion.

Planning the Interventions

A multidisciplinary quality‐improvement team met weekly during the 90‐day design period from January 2007 to March 2007. Our team included representatives from the departments of medicine, anesthesia and critical care, surgery, nursing, and emergency medicine. We also partnered with our institution's clinical and administrative leaders, experts in simulation, and the hospital quality department.

We hypothesized that a standardized set of education and training interventions promoting ultrasound‐guided IJ CVC insertion as the method of choice at our hospital would significantly reduce our rate of CVC‐associated IAP. Our multifaceted intervention included: (1) clinical and documentation standards based on evidence, (2) cognitive aids, (3) simulation training, (4) purchase and deployment of ultrasound equipment, and (5) feedback to clinical services.

Our team followed the define, measure, analyze, improve, control (DMAIC) framework.[15] We set interval goals with target completion dates throughout the 90‐day period, identified owners of each goal, and tracked progress with a shared spreadsheet.

In the 90‐day intervention, we accomplished the following: (1) conducted root‐cause analysis of IAP cases for fiscal year 2006, (2) created clinical and documentation standards around CVC placement, (3) created cognitive aids and procedure note templates, (4) developed simulation training courses, and (5) requested purchase of additional ultrasound equipment.

Data Collection

To evaluate our progress in reducing the rates of IAP, we tracked the incidence of IAP using UHC and AHRQ PSI methodology. In collaboration with our hospital's quality department, we manually reviewed every PSI‐identified case of IAP. This review has focused on identifying whether or not pneumothorax actually occurred, and whether it was associated with CVC insertion. For those associated with CVC, data were collected for patient location and service, the procedure site, whether ultrasound was used, whether a chest tube was required, and the final disposition of the patient.

Demographic data (age, gender, case mix index [CMI]) shown in Table 1 were obtained through MIDAS+ Solutions (Tucson, Arizona), a proprietary database that contains healthcare management coded data. Total hospital CVC insertion rates were calculated using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD‐9) coding for 38.93 and 38.97. ICU central lineassociated blood stream infections (CLABSI) data were obtained from internal collection by our infection control team. Number and location of CVCs placed in the ICU data were obtained from nursing flow sheets in our electronic medical record (EMR). Cost information was provided by our finance department using internal accounting.

| Patients With CVC Insertion | Year | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

| |||||||||

| Age, y (mean) | 55.0 | 55.5 | 55.0 | 57.0 | 56.5 | 58.5 | 57.5 | 59.0 | 58.5 |

| % female | 47.0 | 49.5 | 47.0 | 48.8 | 46.2 | 46.1 | 45.7 | 46.2 | 45.7 |

| Case‐mix index | 3.08 | 3.35 | 3.21 | 3.40 | 3.71 | 3.91 | 3.92 | 3.92 | 4.08 |

| Total no. of CVCs/year* | 1,593 | 1,141 | 1,589 | 2,250 | 2,441 | 2,774 | 2,754 | 2,722 | 2,845 |

| No. of CVCs/year in ICU | NA | NA | NA | 1,502 | 1,357 | 1,345 | 1,316 | 1,421 | 1,590 |

| No. of subclavians/year in ICU | NA | NA | NA | 167 | 75 | 70 | 83 | 75 | 97 |

| No. of IJs/year in ICU | NA | NA | NA | 898 | 773 | 681 | 677 | 713 | 876 |

| No. of femorals/year in ICU | NA | NA | NA | 212 | 152 | 203 | 171 | 198 | 206 |

| No. of PICCs/year in ICU | NA | NA | NA | 225 | 357 | 391 | 385 | 435 | 411 |

| Preintervention (2006) | Postintervention (20082014) | P Value | |||||||

| Age, y (mean) | 55.2 | 58.7 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| % female | 47.0% | 46.4% | 0.642 | ||||||

| Case‐mix index | 3.08 | 3.73 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| CVC insertion rate | 8.1% | 11.4% | <0.0001 | ||||||

| All Inpatients | Year | ||||||||

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

| Age, y (mean) | 57.1 | 57.2 | 56.8 | 57.2 | 57.5 | 58.0 | 58.0 | 57.9 | 58.3 |

| % female | 51.6 | 51.2 | 52.4 | 51.7 | 51.1 | 51.5 | 50.3 | 49.9 | 50.1 |

| Case‐mix index | 1.86 | 1.98 | 1.96 | 1.99 | 1.96 | 2.02 | 2.03 | 2.07 | 2.23 |

| Preintervention (2006) | Postintervention (20082014) | P Value | |||||||

| Age, y (mean) | 57.1 | 57.6 | <0.01 | ||||||

| % female | 51.6% | 50.9% | 0.07 | ||||||

| Case‐mix index | 1.86 | 2.03 | 0.13 | ||||||

| Central Line‐Associated Bloodstream Infections per 1,000 Central Line Days | |||||||||

| Preintervention | Postintervention | P Value | |||||||

| Short term (2006 vs 2008) | 1.8 | 0.60 | 0.004 | ||||||

| Long term (2006 vs 20082014) | 1.8 | 0.68 | <0.0001 | ||||||

The project granted a Notice of Determination of Approval from the Stanford Administrative Panels for the Protection of Human Subjects (institutional review board).

Methods of Evaluation/Analysis

For the purpose of this analysis, the preintervention period was defined as January 1, 2006 through December 31, 2006, our first year of IAP case review. We defined the intervention period as January 1, 2007 through December 31, 2007, during which we planned and implemented hospital‐wide standardization of CVC insertion practices and incorporated CVC insertion training simulation into resident orientation in July 2007. The postintervention period was defined as January 1, 2008 through December 31, 2014.

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). [2] tests were used to determine statistical differences in pre‐ versus postintervention patient demographic data (age, gender, CMI), CVC insertion rates, and CLABSI rates. Because IAP is a rare event, a statistical process control g‐chart was created using QI Macros (KnowWare International, Inc., Denver, CO) to show the number of CVC procedures between IAP. [2] and Fisher exact tests were used to determine statistical differences in CVC anatomic location and use of ultrasound pre‐ and postintervention. A 2‐sided Z test to show a difference in proportions was used to determine statistical differences in CVC‐related IAP rate and all‐cause IAP rate pre‐ and postintervention.

Measuring Adherence to Intervention

Location of CVC Placement and Ultrasound Guidance Pre‐ Versus Postintervention

We utilized the Stanford Clinical Informatics Center (SCCI) services for obtaining counts of patients. Custom queries were performed on SCCI's Stanford Translational Research Integrated Database Environment (STRIDE) platform[16] to search Stanford Hospital electronic heath records for patients. This search primarily involved getting counts for the number of patients with clinical notes that contained the keywords of interest. To identify documentation for placement of CVC from 2006 to 2014, procedure or operative notes containing the words central line or CVC were counted. Further subcounts were obtained by searching for additional keywords such as PICC [peripherally inserted central catheters], femoral, jugular, subclavian, and ultrasound.

Adherence to Intervention in the ICU in 2014

A total of 100 charts were reviewed from patients in our medical and surgical ICU with a CVC in 2014 to evaluate the current trend of central line placement and sustainability of our intervention. Fifty charts were initially randomly selected from the ICU cohort. For those who had multiple lines placed, only the first line was reviewed. Because the initial audit did not provide enough SC lines and we wanted to review more IJ lines, we randomly selected an additional 25 patients who had SC and 25 patients who had IJ to review. The following was collected during chart review: primary team, location of line placement, usage of ultrasound, usage of standard procedure template, supervision, level of training for supervisor, and level of training for staff who performed procedure.

Outcomes

The rate of CVC‐associated IAP was calculated as the total number of IAPs attributed to CVCs divided by the total number of CVCs inserted determined by ICD‐9 coding for 38.93 and 38.97. The total IAP rate was calculated as the total number of IAP/1000 discharges.

RESULTS

Interventions

Our team began the intervention in early 2007 with promotion of ultrasound‐guided IJ catheterization. Clinical exceptions included: (1) trauma or code situations where access to the neck is limited, (2) suspected or confirmed neck injuries, (3) presence of a tracheostomy, and (4) bilateral internal jugular sites unsuitable for catheterization.

Our hospital adopted new formal CVC insertion policies consistent with the above training and education efforts. All physicians were required to document CVC insertions using the template available in the EMR. To be certified to perform CVC insertion independently, trainee physicians were required to complete the simulation training and successfully place a minimum of 5 CVCs directly supervised by an already‐certified physician. This was consistent with the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education suggested minimum requirement in 2007. In our critical care units, all CVC insertions must be supervised by an ICU fellow or attending.

To reinforce the on‐the‐ground work by our physician leaders, we created 2 education tools to embed best practices into our CVC insertion workflow. A checklist with best practices for CVC insertion that was distributed throughout the hospital via central line kits and educational flyers, and a CVC insertion procedure note template consistent with California Department of Public Health documentation requirements was made available in our EMR.

In June 2007, we integrated CVC insertion simulation training into procedure workshops required for all medicine, surgery, anesthesia, and emergency medicine trainees during their intern year. These workshops promoted ultrasound‐guided IJ catheterization and supporting evidence for the new IJ site preference. Training sessions were 2 to 3 hours, and included a demonstration of best‐practice CVC insertion, as well as training with simulation models supervised by an instructor using a standardized CVC checklist. These trainings used both the Blue Phantom human torso model (

Hospital administration provided funds to purchase ultrasound machines for patient units such as medicine, cardiology, ED, and ICU). A total of 4 Site‐Rite (Bard Access Systems, Inc., Salt Lake City, UT) ultrasounds were purchased in 2007. The hospital has continued to purchase ultrasound units yearly, and had 53 ultrasound units in 2014

Cases of IAP were continuously reviewed throughout the intervention period. Based on their higher CVC‐associated IAP rates, the ORs and catheterization lab were identified as having opportunities for improvement. In 2008, Hospital quality‐improvement leadership met with physician leaders in these areas to review their CVC‐related IAP data and to discuss strategies to reduce their IAP rates. These strategies included lessons learned from other services that had successfully decreased their IAP rates.

To sustain our gains, we continue to review all IAP through our coding quality, clinical documentation, quality reporting departments, and peer review. We have implemented other strategies to decrease IAP, such as the use of ultrasound guidance for bedside thoracentesis procedures, which became possible after the availability of more ultrasound devices. Training for ultrasound‐guided thoracentesis was done by our procedure‐team attending during supervision of residents.

Outcomes

Preintervention (January 1, 2006 to December 31, 2006)

There were a total of 26 cases of IAP in 2006. Of these, 15 (58%) were associated with CVC insertion (Figure 1). The single procedure associated with the largest proportion of IAP was SC CVC insertion (11 cases, 42% of all IAP cases). Eleven CVC‐associated IAPs were significant enough to require chest tube placement. Our hospital recorded a total of 1593 CVC insertions (ICD‐9 codes 38.93 and 38.97) in 2006.

Postintervention (January 1, 2008 to December 31, 2014)

There were a total of 80 cases of IAP over 7 years, of which 24 (30%) were associated with CVC insertion. Of these, 16 required chest tube placement. In the last 4 years of the postintervention period (20112014), there were only 5 cases of CVC‐associated IAP requiring chest tube placement (Figure 1). There were a total of 12,000 CVC insertions recorded over the same period.