User login

Skin is skin, no matter the location

HISTORY

A 26-year-old man presents with a lesion on his penis that has existed for many years—at least 10—without significant change and with no attendant symptoms. His new girlfriend, having heard that penile lesions can be dangerous, or even represent contagious disease, insisted that he seek medical evaluation.

He first went to his primary care provider (PCP), who admitted he had no idea what the lesion was; however, he agreed that the longstanding, constant nature of it was reassuring. The PCP advised the patient to consult a urologist. However, the staff at the urology office he contacted advised the patient to consult dermatology instead.

In the dermatology office, a thorough history is taken, including a sexual history that is negative for high-risk factors for HIV or other STDs. Aside from his lesion, the patient has no health-related complaints or causes for concern.

EXAMINATION

The lesion is actually composed of four grouped purple papules, each about 1 to 1.5 mm in diameter, in aggregate measuring about 8 mm. It is located within 6 mm of the urethral meatus, on the penile glans. The papules are soft and compressible, but barely palpable. Looking elsewhere, no other lesions are seen on the genitals or elsewhere on the body. Notably, the patient is circumcised.

DISCUSSION

I’ve seen these lesions in this exact location several times over a 25-year period. The first was in the early HIV era, and produced enough concern that a biopsy was indicated to rule out things such as Kaposi’s sarcoma or bacillary angiomatosis. What that lesion proved to be is almost certainly what this patient has: angiokeratoma of Fordyce, a totally benign lesion.

These types of angiokeratomas are ectatic, thin-walled vessels in the superficial dermis, with overlying epidermal hyperplasia that forms secondary to normal friction. When they are seen on the scrotum, vulva, or penis, they are usually referred to as angiokeratoma of Fordyce, a type of localized angiokeratoma, other types of which can appear on the legs or hands.

These totally benign lesions must be distinguished from generalized types of angiokeratomata, such as those seen in Fabry disease (angiokeratoma corporis diffusum), an inheritable metabolic disorder. With our patient’s history, his lesion was clearly benign.

Had his lesion been new or changing in any substantive way, additional testing, including a biopsy, might have been necessary to rule out entities such as squamous cell carcinoma (which is almost unknown in circumcised patients), condyloma, melanoma, the aforementioned Kaposi’s sarcoma, or even angiosarcoma.

This case highlights several useful points:

(1) Odd skin lesions need to be sent to the “odd skin lesion” specialist, also known as a dermatology provider. Just because the lesion is on the penis does not mean the patient needs to see a urologist. By the same token, neither does a patient with an odd skin lesion on a foot need to see a podiatrist.

(2) It pays to be a “collector” of anatomic differentials, as in “What lesions might I expect to see on (a given area of the body)?” This concept is valid for any area of the body, and certainly no less true for the penis.

(3) It’s been said that being an effective dermatology provider is as much about “sales” as it is about being an astute diagnostician. In other words, as this case demonstrates, it’s not enough for the provider to be convinced of the identity of the lesion—he must be able to “sell” the concept to a potentially skeptical patient. And in order to do that, the first person he needs to convince is himself.

TAKE-AWAY LEARNING POINTS

• Referral to dermatology is the correct step for any visible lesion or condition, regardless of location—the only exception being internal lesions.

• Just because a lesion is on the penis doesn’t mean it needs to be referred to urology. Skin is skin, irrespective of location.

• It’s not enough to “know” what a given lesion is. Knowing what it isn’t is just as important. And knowing what it means (or doesn’t mean) is often the most important thing of all.

• Anatomic differentials—what types of lesions/conditions are commonly seen in a given anatomic location—are often extremely useful.

HISTORY

A 26-year-old man presents with a lesion on his penis that has existed for many years—at least 10—without significant change and with no attendant symptoms. His new girlfriend, having heard that penile lesions can be dangerous, or even represent contagious disease, insisted that he seek medical evaluation.

He first went to his primary care provider (PCP), who admitted he had no idea what the lesion was; however, he agreed that the longstanding, constant nature of it was reassuring. The PCP advised the patient to consult a urologist. However, the staff at the urology office he contacted advised the patient to consult dermatology instead.

In the dermatology office, a thorough history is taken, including a sexual history that is negative for high-risk factors for HIV or other STDs. Aside from his lesion, the patient has no health-related complaints or causes for concern.

EXAMINATION

The lesion is actually composed of four grouped purple papules, each about 1 to 1.5 mm in diameter, in aggregate measuring about 8 mm. It is located within 6 mm of the urethral meatus, on the penile glans. The papules are soft and compressible, but barely palpable. Looking elsewhere, no other lesions are seen on the genitals or elsewhere on the body. Notably, the patient is circumcised.

DISCUSSION

I’ve seen these lesions in this exact location several times over a 25-year period. The first was in the early HIV era, and produced enough concern that a biopsy was indicated to rule out things such as Kaposi’s sarcoma or bacillary angiomatosis. What that lesion proved to be is almost certainly what this patient has: angiokeratoma of Fordyce, a totally benign lesion.

These types of angiokeratomas are ectatic, thin-walled vessels in the superficial dermis, with overlying epidermal hyperplasia that forms secondary to normal friction. When they are seen on the scrotum, vulva, or penis, they are usually referred to as angiokeratoma of Fordyce, a type of localized angiokeratoma, other types of which can appear on the legs or hands.

These totally benign lesions must be distinguished from generalized types of angiokeratomata, such as those seen in Fabry disease (angiokeratoma corporis diffusum), an inheritable metabolic disorder. With our patient’s history, his lesion was clearly benign.

Had his lesion been new or changing in any substantive way, additional testing, including a biopsy, might have been necessary to rule out entities such as squamous cell carcinoma (which is almost unknown in circumcised patients), condyloma, melanoma, the aforementioned Kaposi’s sarcoma, or even angiosarcoma.

This case highlights several useful points:

(1) Odd skin lesions need to be sent to the “odd skin lesion” specialist, also known as a dermatology provider. Just because the lesion is on the penis does not mean the patient needs to see a urologist. By the same token, neither does a patient with an odd skin lesion on a foot need to see a podiatrist.

(2) It pays to be a “collector” of anatomic differentials, as in “What lesions might I expect to see on (a given area of the body)?” This concept is valid for any area of the body, and certainly no less true for the penis.

(3) It’s been said that being an effective dermatology provider is as much about “sales” as it is about being an astute diagnostician. In other words, as this case demonstrates, it’s not enough for the provider to be convinced of the identity of the lesion—he must be able to “sell” the concept to a potentially skeptical patient. And in order to do that, the first person he needs to convince is himself.

TAKE-AWAY LEARNING POINTS

• Referral to dermatology is the correct step for any visible lesion or condition, regardless of location—the only exception being internal lesions.

• Just because a lesion is on the penis doesn’t mean it needs to be referred to urology. Skin is skin, irrespective of location.

• It’s not enough to “know” what a given lesion is. Knowing what it isn’t is just as important. And knowing what it means (or doesn’t mean) is often the most important thing of all.

• Anatomic differentials—what types of lesions/conditions are commonly seen in a given anatomic location—are often extremely useful.

HISTORY

A 26-year-old man presents with a lesion on his penis that has existed for many years—at least 10—without significant change and with no attendant symptoms. His new girlfriend, having heard that penile lesions can be dangerous, or even represent contagious disease, insisted that he seek medical evaluation.

He first went to his primary care provider (PCP), who admitted he had no idea what the lesion was; however, he agreed that the longstanding, constant nature of it was reassuring. The PCP advised the patient to consult a urologist. However, the staff at the urology office he contacted advised the patient to consult dermatology instead.

In the dermatology office, a thorough history is taken, including a sexual history that is negative for high-risk factors for HIV or other STDs. Aside from his lesion, the patient has no health-related complaints or causes for concern.

EXAMINATION

The lesion is actually composed of four grouped purple papules, each about 1 to 1.5 mm in diameter, in aggregate measuring about 8 mm. It is located within 6 mm of the urethral meatus, on the penile glans. The papules are soft and compressible, but barely palpable. Looking elsewhere, no other lesions are seen on the genitals or elsewhere on the body. Notably, the patient is circumcised.

DISCUSSION

I’ve seen these lesions in this exact location several times over a 25-year period. The first was in the early HIV era, and produced enough concern that a biopsy was indicated to rule out things such as Kaposi’s sarcoma or bacillary angiomatosis. What that lesion proved to be is almost certainly what this patient has: angiokeratoma of Fordyce, a totally benign lesion.

These types of angiokeratomas are ectatic, thin-walled vessels in the superficial dermis, with overlying epidermal hyperplasia that forms secondary to normal friction. When they are seen on the scrotum, vulva, or penis, they are usually referred to as angiokeratoma of Fordyce, a type of localized angiokeratoma, other types of which can appear on the legs or hands.

These totally benign lesions must be distinguished from generalized types of angiokeratomata, such as those seen in Fabry disease (angiokeratoma corporis diffusum), an inheritable metabolic disorder. With our patient’s history, his lesion was clearly benign.

Had his lesion been new or changing in any substantive way, additional testing, including a biopsy, might have been necessary to rule out entities such as squamous cell carcinoma (which is almost unknown in circumcised patients), condyloma, melanoma, the aforementioned Kaposi’s sarcoma, or even angiosarcoma.

This case highlights several useful points:

(1) Odd skin lesions need to be sent to the “odd skin lesion” specialist, also known as a dermatology provider. Just because the lesion is on the penis does not mean the patient needs to see a urologist. By the same token, neither does a patient with an odd skin lesion on a foot need to see a podiatrist.

(2) It pays to be a “collector” of anatomic differentials, as in “What lesions might I expect to see on (a given area of the body)?” This concept is valid for any area of the body, and certainly no less true for the penis.

(3) It’s been said that being an effective dermatology provider is as much about “sales” as it is about being an astute diagnostician. In other words, as this case demonstrates, it’s not enough for the provider to be convinced of the identity of the lesion—he must be able to “sell” the concept to a potentially skeptical patient. And in order to do that, the first person he needs to convince is himself.

TAKE-AWAY LEARNING POINTS

• Referral to dermatology is the correct step for any visible lesion or condition, regardless of location—the only exception being internal lesions.

• Just because a lesion is on the penis doesn’t mean it needs to be referred to urology. Skin is skin, irrespective of location.

• It’s not enough to “know” what a given lesion is. Knowing what it isn’t is just as important. And knowing what it means (or doesn’t mean) is often the most important thing of all.

• Anatomic differentials—what types of lesions/conditions are commonly seen in a given anatomic location—are often extremely useful.

2013;23(6):W5

A little girl with big skin problems

HISTORY

A 6-year-old girl is brought to dermatology for evaluation of several problems: “dry skin” present since birth, as well as new “bumps” that her family has noted recently. There are additional questions about her skin, mostly revolving around its sensitivity (illustrated by overreaction to mosquito bites) and whether there is a connection to food allergy.

She has seen an allergist, who ordered testing that revealed a sensitivity to airborne allergens (eg, dust, pollen, mold). However, the allergist assured the patient and her family that none of these had any relation to her skin complaints.

The child’s two older siblings have similar dermatologic problems, and one also has asthma. All three had terrible diaper rashes as infants.

The parents, who were both allergy-prone as children, wonder if there is a connection between their children’s skin problems and stress. They have noticed a worsening of the itching and scratching with increased levels of anxiety or tension.

EXAMINATION

The child has extremely dry skin all over her body, but especially on her extremities. Her palms exhibit an excessive number of lines. The “bumps” on her skin are widely scattered and firm and average 1 to 1.5 mm in diameter. Several have umbilicated centers.

Her periorbital skin is dark, slightly scaly, and edematous, especially beneath the eyes, where extra lines have been created by the edema.

A faint but definite transverse white line is evident on her nose. Transverse ridging is seen on several fingernails.

DISCUSSION

This child and her family could serve as walking textbooks on an extremely common diagnosis: atopic dermatitis (AD), which involves a constellation of skin issues combined with an allergic constitution.

Major diagnostic criteria include a low threshold for pruritus, a personal and/or family history of eczema and atopy, and chronic or chronically relapsing eczematous dermatitis occurring in characteristic distributive patterns (the face and extensor surfaces on children; flexural surfaces on older children and adults).

Minor diagnostic criteria number at least 23, and include several of our patient’s signs: Dennie-Morgan folds, dry skin (xerosis), onset of problems early in life, susceptibility to skin infections such as molluscum, periorbital darkening (so-called allergic shiners), hyperlinearity of the palms, and the transverse nasal crease between the upper two-thirds and lower one-third of her nose, created by years of habitual upward rubbing. The observation by her parents that stress exacerbates the problem is yet another corroborative finding.

It’s important to note that in families like this one, not every child experiences the full measure of allergic and cutaneous problems. It’s not at all unusual, for example, to see one child with dry, sensitive skin and no obvious allergic phenomena, while a sibling might have minimal skin issues but major problems with asthma and seasonal allergies. It’s no wonder families are often quite confused, particularly when they are being told contradictory things by well-meaning medical providers and family members.

It’s critical for us, as medical providers, to have an accurate overview of how utterly common atopic dermatitis is, along with its myriad manifestations. This problem already affects at least 15% of the population to one degree or another, and its incidence is growing rapidly worldwide, primarily among the relatively affluent.

Much research has been done regarding the genetic and physiologic bases of AD, but those issues remain far from settled. What we do know is that AD patients have two basic problems: First, their skin is too thin and dry to serve as an effective barrier. Second, they have a dysfunctional and overreactive immune response to a multitude of allergens that present minor issues to the rest of us. One theory holds that the thin skin is what allows antigens to penetrate and set off the dysfunctional immune response.

In any case, it’s important to be able to recognize this common condition, and to be able to educate patients and parents. The inherited nature of the problem must be stressed, as the manifestations will likely continue (in one form or another) despite any treatment that is attempted. These are key pieces of information, without which patients and parents worry needlessly about the wrong things (often, food is blamed, though it is almost never the cause), to the neglect of potentially effective measures that could be taken.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Dennie-Morgan folds represent one of many minor diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis (AD).

• It is difficult to overstate the pervasive nature of AD, both because it affects so many people (at least 15% of the population) and because it has a variety of manifestations (eg, dry and/or sensitive skin, eczema, hives, asthma).

• The tendency to develop AD is inherited, but it is frequently (and erroneously) blamed on food allergies, too-frequent bathing, or laundry detergent.

• Dry winter weather, long hot showers, and use of colored/perfumed soaps are common triggers for eczema.

• Emotional stress is a major trigger for eczema flares.

HISTORY

A 6-year-old girl is brought to dermatology for evaluation of several problems: “dry skin” present since birth, as well as new “bumps” that her family has noted recently. There are additional questions about her skin, mostly revolving around its sensitivity (illustrated by overreaction to mosquito bites) and whether there is a connection to food allergy.

She has seen an allergist, who ordered testing that revealed a sensitivity to airborne allergens (eg, dust, pollen, mold). However, the allergist assured the patient and her family that none of these had any relation to her skin complaints.

The child’s two older siblings have similar dermatologic problems, and one also has asthma. All three had terrible diaper rashes as infants.

The parents, who were both allergy-prone as children, wonder if there is a connection between their children’s skin problems and stress. They have noticed a worsening of the itching and scratching with increased levels of anxiety or tension.

EXAMINATION

The child has extremely dry skin all over her body, but especially on her extremities. Her palms exhibit an excessive number of lines. The “bumps” on her skin are widely scattered and firm and average 1 to 1.5 mm in diameter. Several have umbilicated centers.

Her periorbital skin is dark, slightly scaly, and edematous, especially beneath the eyes, where extra lines have been created by the edema.

A faint but definite transverse white line is evident on her nose. Transverse ridging is seen on several fingernails.

DISCUSSION

This child and her family could serve as walking textbooks on an extremely common diagnosis: atopic dermatitis (AD), which involves a constellation of skin issues combined with an allergic constitution.

Major diagnostic criteria include a low threshold for pruritus, a personal and/or family history of eczema and atopy, and chronic or chronically relapsing eczematous dermatitis occurring in characteristic distributive patterns (the face and extensor surfaces on children; flexural surfaces on older children and adults).

Minor diagnostic criteria number at least 23, and include several of our patient’s signs: Dennie-Morgan folds, dry skin (xerosis), onset of problems early in life, susceptibility to skin infections such as molluscum, periorbital darkening (so-called allergic shiners), hyperlinearity of the palms, and the transverse nasal crease between the upper two-thirds and lower one-third of her nose, created by years of habitual upward rubbing. The observation by her parents that stress exacerbates the problem is yet another corroborative finding.

It’s important to note that in families like this one, not every child experiences the full measure of allergic and cutaneous problems. It’s not at all unusual, for example, to see one child with dry, sensitive skin and no obvious allergic phenomena, while a sibling might have minimal skin issues but major problems with asthma and seasonal allergies. It’s no wonder families are often quite confused, particularly when they are being told contradictory things by well-meaning medical providers and family members.

It’s critical for us, as medical providers, to have an accurate overview of how utterly common atopic dermatitis is, along with its myriad manifestations. This problem already affects at least 15% of the population to one degree or another, and its incidence is growing rapidly worldwide, primarily among the relatively affluent.

Much research has been done regarding the genetic and physiologic bases of AD, but those issues remain far from settled. What we do know is that AD patients have two basic problems: First, their skin is too thin and dry to serve as an effective barrier. Second, they have a dysfunctional and overreactive immune response to a multitude of allergens that present minor issues to the rest of us. One theory holds that the thin skin is what allows antigens to penetrate and set off the dysfunctional immune response.

In any case, it’s important to be able to recognize this common condition, and to be able to educate patients and parents. The inherited nature of the problem must be stressed, as the manifestations will likely continue (in one form or another) despite any treatment that is attempted. These are key pieces of information, without which patients and parents worry needlessly about the wrong things (often, food is blamed, though it is almost never the cause), to the neglect of potentially effective measures that could be taken.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Dennie-Morgan folds represent one of many minor diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis (AD).

• It is difficult to overstate the pervasive nature of AD, both because it affects so many people (at least 15% of the population) and because it has a variety of manifestations (eg, dry and/or sensitive skin, eczema, hives, asthma).

• The tendency to develop AD is inherited, but it is frequently (and erroneously) blamed on food allergies, too-frequent bathing, or laundry detergent.

• Dry winter weather, long hot showers, and use of colored/perfumed soaps are common triggers for eczema.

• Emotional stress is a major trigger for eczema flares.

HISTORY

A 6-year-old girl is brought to dermatology for evaluation of several problems: “dry skin” present since birth, as well as new “bumps” that her family has noted recently. There are additional questions about her skin, mostly revolving around its sensitivity (illustrated by overreaction to mosquito bites) and whether there is a connection to food allergy.

She has seen an allergist, who ordered testing that revealed a sensitivity to airborne allergens (eg, dust, pollen, mold). However, the allergist assured the patient and her family that none of these had any relation to her skin complaints.

The child’s two older siblings have similar dermatologic problems, and one also has asthma. All three had terrible diaper rashes as infants.

The parents, who were both allergy-prone as children, wonder if there is a connection between their children’s skin problems and stress. They have noticed a worsening of the itching and scratching with increased levels of anxiety or tension.

EXAMINATION

The child has extremely dry skin all over her body, but especially on her extremities. Her palms exhibit an excessive number of lines. The “bumps” on her skin are widely scattered and firm and average 1 to 1.5 mm in diameter. Several have umbilicated centers.

Her periorbital skin is dark, slightly scaly, and edematous, especially beneath the eyes, where extra lines have been created by the edema.

A faint but definite transverse white line is evident on her nose. Transverse ridging is seen on several fingernails.

DISCUSSION

This child and her family could serve as walking textbooks on an extremely common diagnosis: atopic dermatitis (AD), which involves a constellation of skin issues combined with an allergic constitution.

Major diagnostic criteria include a low threshold for pruritus, a personal and/or family history of eczema and atopy, and chronic or chronically relapsing eczematous dermatitis occurring in characteristic distributive patterns (the face and extensor surfaces on children; flexural surfaces on older children and adults).

Minor diagnostic criteria number at least 23, and include several of our patient’s signs: Dennie-Morgan folds, dry skin (xerosis), onset of problems early in life, susceptibility to skin infections such as molluscum, periorbital darkening (so-called allergic shiners), hyperlinearity of the palms, and the transverse nasal crease between the upper two-thirds and lower one-third of her nose, created by years of habitual upward rubbing. The observation by her parents that stress exacerbates the problem is yet another corroborative finding.

It’s important to note that in families like this one, not every child experiences the full measure of allergic and cutaneous problems. It’s not at all unusual, for example, to see one child with dry, sensitive skin and no obvious allergic phenomena, while a sibling might have minimal skin issues but major problems with asthma and seasonal allergies. It’s no wonder families are often quite confused, particularly when they are being told contradictory things by well-meaning medical providers and family members.

It’s critical for us, as medical providers, to have an accurate overview of how utterly common atopic dermatitis is, along with its myriad manifestations. This problem already affects at least 15% of the population to one degree or another, and its incidence is growing rapidly worldwide, primarily among the relatively affluent.

Much research has been done regarding the genetic and physiologic bases of AD, but those issues remain far from settled. What we do know is that AD patients have two basic problems: First, their skin is too thin and dry to serve as an effective barrier. Second, they have a dysfunctional and overreactive immune response to a multitude of allergens that present minor issues to the rest of us. One theory holds that the thin skin is what allows antigens to penetrate and set off the dysfunctional immune response.

In any case, it’s important to be able to recognize this common condition, and to be able to educate patients and parents. The inherited nature of the problem must be stressed, as the manifestations will likely continue (in one form or another) despite any treatment that is attempted. These are key pieces of information, without which patients and parents worry needlessly about the wrong things (often, food is blamed, though it is almost never the cause), to the neglect of potentially effective measures that could be taken.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Dennie-Morgan folds represent one of many minor diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis (AD).

• It is difficult to overstate the pervasive nature of AD, both because it affects so many people (at least 15% of the population) and because it has a variety of manifestations (eg, dry and/or sensitive skin, eczema, hives, asthma).

• The tendency to develop AD is inherited, but it is frequently (and erroneously) blamed on food allergies, too-frequent bathing, or laundry detergent.

• Dry winter weather, long hot showers, and use of colored/perfumed soaps are common triggers for eczema.

• Emotional stress is a major trigger for eczema flares.

Let’s see you pull that out of my back!

HISTORY

This 50-year-old man first noticed a bulge in his low back several years ago. Every time he brings it to the attention of his medical providers, he is told it is, and will remain, benign and that the best thing he can do is leave it alone.

But it finally grows to a bothersome size, causing pain at times—such as when he leans against hard surfaces—and actually becoming visible under certain clothes. And so he seeks evaluation from a dermatology provider.

His health is otherwise excellent, with no family history of such lesions and no personal history of similar manifestations elsewhere on his body.

EXAMINATION

An ill-defined subcutaneous mass is felt in the L4 area of the patient’s mid-low back; no overlying skin changes can be seen or felt. The mass is rubbery, with a smooth surface, and not at all tender to palpation. The patient’s skin is otherwise free of such lesions.

PROCEDURE

After a thorough discussion of the options available to this patient, the decision is made to excise the lesion. As is customary, this conversation includes disclosure of the anticipated procedure (excision), the indications for the procedure, alternatives, and risks involved in removal.

Under local anesthesia (1% lidocaine with epinephrine) and sterile conditions, a horizontal incision is made. This effectively creates an elliptical window through which the lesion can be visualized, freed by blunt dissection, and then removed in one large piece, which turns out to be in excess of 6 cm—larger than anticipated.

The lesion is consistent in every way with the anticipated diagnosis of lipoma, including the presence of the expected “capsule” (extremely thin web of connective tissue) surrounding the tumor. The defect’s size and depth require three layers to close it, leaving the patient with a 5-cm transverse wound. As is always the case with excised lesions, this one is sent for pathologic examination, which confirms the diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

Obviously, the presentation and history of this lesion were quite consistent with an extremely common diagnosis: lipoma. The other main item in the differential is epidermal cyst, although additional diagnostic possibilities include liposarcoma, glomus tumor, and leiomyoma.

Lipomas are the most common tumor of mesenchymal origin. They are composed of mature fat cells, but differ from normal fat by the demonstration of increased levels of lipoprotein lipase and by the presence of larger numbers of precursor cells.

Lipomas can appear almost anywhere—including internal organs and even the spinal cord—though most commonly, by far, in subcutaneous locations on the trunk and extremities. As in this case, they come to the patient’s attention because of growth or discomfort (or both).

Occasionally, lipomas, even after several years, become painful, and on removal may prove to be a benign innervated variant called angiolipoma. While many other subtypes exist, the vast majority is completely benign. Obviously, rapid growth or other change could signal malignant transformation.

Lipomas are often seen in the context of an inherited condition in which multiple asymptomatic lipomas appear in the third decade of life, usually in forearms and thighs. Termed familial benign lipomatosis, its mode of inheritance is autosomal dominance.

Protease inhibitors given for HIV can cause lipodystrophy of several types, including the appearance of lipomas, as well as the well-known buccal atrophy.

Had this patient’s lipoma undergone rapid growth or had it been accompanied by other significant findings (the so-called fawn’s tail, a tuft of hair, unusual tags, hemangiomas and others in the sacral region), it might well have required pre-operative imaging to rule out spinal dysraphism or other occult embryonic malformation.

This patient made a rapid and uneventful recovery from his surgery. Complications could have included hematoma formation, infection, bleeding, or dysfunctional scarring.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Lipomas are extremely common and are often seen in the context of an inherited trait called benign familial lipomatosis.

• Epidermal cysts and lipomas can present in similar fashion, though the cysts tend to be more firm and have an overlying punctum. Lipomas tend to be more rubbery and have no overlying punctum.

• Lipomas can be found almost anywhere in the body, including internally.

• Lipomas frequently prove to be larger on removal than would be expected from outward appearance.

• With large lipomas in certain locations—such as in the medial epicondylar area, deep in the forehead, in the scalp, or in the upper trapezius area, for example—consider referral to a surgeon.

HISTORY

This 50-year-old man first noticed a bulge in his low back several years ago. Every time he brings it to the attention of his medical providers, he is told it is, and will remain, benign and that the best thing he can do is leave it alone.

But it finally grows to a bothersome size, causing pain at times—such as when he leans against hard surfaces—and actually becoming visible under certain clothes. And so he seeks evaluation from a dermatology provider.

His health is otherwise excellent, with no family history of such lesions and no personal history of similar manifestations elsewhere on his body.

EXAMINATION

An ill-defined subcutaneous mass is felt in the L4 area of the patient’s mid-low back; no overlying skin changes can be seen or felt. The mass is rubbery, with a smooth surface, and not at all tender to palpation. The patient’s skin is otherwise free of such lesions.

PROCEDURE

After a thorough discussion of the options available to this patient, the decision is made to excise the lesion. As is customary, this conversation includes disclosure of the anticipated procedure (excision), the indications for the procedure, alternatives, and risks involved in removal.

Under local anesthesia (1% lidocaine with epinephrine) and sterile conditions, a horizontal incision is made. This effectively creates an elliptical window through which the lesion can be visualized, freed by blunt dissection, and then removed in one large piece, which turns out to be in excess of 6 cm—larger than anticipated.

The lesion is consistent in every way with the anticipated diagnosis of lipoma, including the presence of the expected “capsule” (extremely thin web of connective tissue) surrounding the tumor. The defect’s size and depth require three layers to close it, leaving the patient with a 5-cm transverse wound. As is always the case with excised lesions, this one is sent for pathologic examination, which confirms the diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

Obviously, the presentation and history of this lesion were quite consistent with an extremely common diagnosis: lipoma. The other main item in the differential is epidermal cyst, although additional diagnostic possibilities include liposarcoma, glomus tumor, and leiomyoma.

Lipomas are the most common tumor of mesenchymal origin. They are composed of mature fat cells, but differ from normal fat by the demonstration of increased levels of lipoprotein lipase and by the presence of larger numbers of precursor cells.

Lipomas can appear almost anywhere—including internal organs and even the spinal cord—though most commonly, by far, in subcutaneous locations on the trunk and extremities. As in this case, they come to the patient’s attention because of growth or discomfort (or both).

Occasionally, lipomas, even after several years, become painful, and on removal may prove to be a benign innervated variant called angiolipoma. While many other subtypes exist, the vast majority is completely benign. Obviously, rapid growth or other change could signal malignant transformation.

Lipomas are often seen in the context of an inherited condition in which multiple asymptomatic lipomas appear in the third decade of life, usually in forearms and thighs. Termed familial benign lipomatosis, its mode of inheritance is autosomal dominance.

Protease inhibitors given for HIV can cause lipodystrophy of several types, including the appearance of lipomas, as well as the well-known buccal atrophy.

Had this patient’s lipoma undergone rapid growth or had it been accompanied by other significant findings (the so-called fawn’s tail, a tuft of hair, unusual tags, hemangiomas and others in the sacral region), it might well have required pre-operative imaging to rule out spinal dysraphism or other occult embryonic malformation.

This patient made a rapid and uneventful recovery from his surgery. Complications could have included hematoma formation, infection, bleeding, or dysfunctional scarring.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Lipomas are extremely common and are often seen in the context of an inherited trait called benign familial lipomatosis.

• Epidermal cysts and lipomas can present in similar fashion, though the cysts tend to be more firm and have an overlying punctum. Lipomas tend to be more rubbery and have no overlying punctum.

• Lipomas can be found almost anywhere in the body, including internally.

• Lipomas frequently prove to be larger on removal than would be expected from outward appearance.

• With large lipomas in certain locations—such as in the medial epicondylar area, deep in the forehead, in the scalp, or in the upper trapezius area, for example—consider referral to a surgeon.

HISTORY

This 50-year-old man first noticed a bulge in his low back several years ago. Every time he brings it to the attention of his medical providers, he is told it is, and will remain, benign and that the best thing he can do is leave it alone.

But it finally grows to a bothersome size, causing pain at times—such as when he leans against hard surfaces—and actually becoming visible under certain clothes. And so he seeks evaluation from a dermatology provider.

His health is otherwise excellent, with no family history of such lesions and no personal history of similar manifestations elsewhere on his body.

EXAMINATION

An ill-defined subcutaneous mass is felt in the L4 area of the patient’s mid-low back; no overlying skin changes can be seen or felt. The mass is rubbery, with a smooth surface, and not at all tender to palpation. The patient’s skin is otherwise free of such lesions.

PROCEDURE

After a thorough discussion of the options available to this patient, the decision is made to excise the lesion. As is customary, this conversation includes disclosure of the anticipated procedure (excision), the indications for the procedure, alternatives, and risks involved in removal.

Under local anesthesia (1% lidocaine with epinephrine) and sterile conditions, a horizontal incision is made. This effectively creates an elliptical window through which the lesion can be visualized, freed by blunt dissection, and then removed in one large piece, which turns out to be in excess of 6 cm—larger than anticipated.

The lesion is consistent in every way with the anticipated diagnosis of lipoma, including the presence of the expected “capsule” (extremely thin web of connective tissue) surrounding the tumor. The defect’s size and depth require three layers to close it, leaving the patient with a 5-cm transverse wound. As is always the case with excised lesions, this one is sent for pathologic examination, which confirms the diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

Obviously, the presentation and history of this lesion were quite consistent with an extremely common diagnosis: lipoma. The other main item in the differential is epidermal cyst, although additional diagnostic possibilities include liposarcoma, glomus tumor, and leiomyoma.

Lipomas are the most common tumor of mesenchymal origin. They are composed of mature fat cells, but differ from normal fat by the demonstration of increased levels of lipoprotein lipase and by the presence of larger numbers of precursor cells.

Lipomas can appear almost anywhere—including internal organs and even the spinal cord—though most commonly, by far, in subcutaneous locations on the trunk and extremities. As in this case, they come to the patient’s attention because of growth or discomfort (or both).

Occasionally, lipomas, even after several years, become painful, and on removal may prove to be a benign innervated variant called angiolipoma. While many other subtypes exist, the vast majority is completely benign. Obviously, rapid growth or other change could signal malignant transformation.

Lipomas are often seen in the context of an inherited condition in which multiple asymptomatic lipomas appear in the third decade of life, usually in forearms and thighs. Termed familial benign lipomatosis, its mode of inheritance is autosomal dominance.

Protease inhibitors given for HIV can cause lipodystrophy of several types, including the appearance of lipomas, as well as the well-known buccal atrophy.

Had this patient’s lipoma undergone rapid growth or had it been accompanied by other significant findings (the so-called fawn’s tail, a tuft of hair, unusual tags, hemangiomas and others in the sacral region), it might well have required pre-operative imaging to rule out spinal dysraphism or other occult embryonic malformation.

This patient made a rapid and uneventful recovery from his surgery. Complications could have included hematoma formation, infection, bleeding, or dysfunctional scarring.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Lipomas are extremely common and are often seen in the context of an inherited trait called benign familial lipomatosis.

• Epidermal cysts and lipomas can present in similar fashion, though the cysts tend to be more firm and have an overlying punctum. Lipomas tend to be more rubbery and have no overlying punctum.

• Lipomas can be found almost anywhere in the body, including internally.

• Lipomas frequently prove to be larger on removal than would be expected from outward appearance.

• With large lipomas in certain locations—such as in the medial epicondylar area, deep in the forehead, in the scalp, or in the upper trapezius area, for example—consider referral to a surgeon.

An Encounter With Unflattering Light

ANSWER

The correct answer is dermatoheliosis (choice “d”), also correctly termed photoaging. This condition manifests as a number of specific skin changes, including the items named (choices “a,” “b,” and “c”)—all of which were present on this patient.

DISCUSSION

The consequences of chronic overexposure to UV radiation constitute the most common reason patients present to dermatology practices in the United States. The bulk of this damage takes decades to appear, by which time patients have forgotten about their earlier sun exposure (in fact, they often deny any exposure) and even the painful sunburns that taught them to avoid the sun in the first place.

In general, the effects of sunburns sustained in childhood or young adulthood do not usually manifest until the patient is in his/her 50s or 60s, although patients who are less sun-tolerant (our definition of “fair”) may show signs of damage considerably earlier.

However, with the popularity of artificial tanning among teenagers (and even preteens in some cases), evidence of sun damage is being seen at younger ages than ever. Basal cell carcinomas, once unheard of in teenagers, are being found with increasing frequency in this age-group. In patients ages 12 to 15, there has been a 100-fold increase in the incidence of melanoma—theorized to be due, in part, to the effects of artificial tanning.

This particular patient is typical of cases in which sun damage was obtained more passively. At one time in the US, having a tan was decidedly unfashionable; it marked one as a member of “the lower classes.” But that all began to change after WWI: Hemlines and hairlines rose, Prohibition created a new generation of drinkers and scofflaws, clothing began to be more revealing, and suddenly it was fashionable for women to shave their legs and get a tan.

About that same time, many men began to ignore the long-held tradition of wearing hats and long sleeves when outside, inevitably tanned, and thus gained approval from the opposite sex. Most went off to war in the 1940s, many to the Pacific theater, where they had even more exposure to the sun.

Following WWII, a great number of these men returned to their jobs as farmers, ranchers, or construction workers. Golfing became the “in” sport during leisure time. It’s this generation we’re seeing now for sun-related pathology. Even if they had been inclined to use it, effective sunscreen was not generally available until the early 1970s.

The patient depicted here has a typical collection of the pre-cancerous sun damage known as dermatoheliosis: solar elastosis, actinic keratoses, telangiectasias, and solar atrophy (which affects the arms more than the face). The latter, along with the effects of wind, heat, cold, smoking, and drinking alcohol, constitute the main causes of extrinsic aging.

TREATMENT

Short of heroic efforts, not much will be done for this patient’s dermatoheliosis. However, he was strongly advised to return to dermatology twice a year to watch for the arrival of the basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas that are almost certainly headed his way.

ANSWER

The correct answer is dermatoheliosis (choice “d”), also correctly termed photoaging. This condition manifests as a number of specific skin changes, including the items named (choices “a,” “b,” and “c”)—all of which were present on this patient.

DISCUSSION

The consequences of chronic overexposure to UV radiation constitute the most common reason patients present to dermatology practices in the United States. The bulk of this damage takes decades to appear, by which time patients have forgotten about their earlier sun exposure (in fact, they often deny any exposure) and even the painful sunburns that taught them to avoid the sun in the first place.

In general, the effects of sunburns sustained in childhood or young adulthood do not usually manifest until the patient is in his/her 50s or 60s, although patients who are less sun-tolerant (our definition of “fair”) may show signs of damage considerably earlier.

However, with the popularity of artificial tanning among teenagers (and even preteens in some cases), evidence of sun damage is being seen at younger ages than ever. Basal cell carcinomas, once unheard of in teenagers, are being found with increasing frequency in this age-group. In patients ages 12 to 15, there has been a 100-fold increase in the incidence of melanoma—theorized to be due, in part, to the effects of artificial tanning.

This particular patient is typical of cases in which sun damage was obtained more passively. At one time in the US, having a tan was decidedly unfashionable; it marked one as a member of “the lower classes.” But that all began to change after WWI: Hemlines and hairlines rose, Prohibition created a new generation of drinkers and scofflaws, clothing began to be more revealing, and suddenly it was fashionable for women to shave their legs and get a tan.

About that same time, many men began to ignore the long-held tradition of wearing hats and long sleeves when outside, inevitably tanned, and thus gained approval from the opposite sex. Most went off to war in the 1940s, many to the Pacific theater, where they had even more exposure to the sun.

Following WWII, a great number of these men returned to their jobs as farmers, ranchers, or construction workers. Golfing became the “in” sport during leisure time. It’s this generation we’re seeing now for sun-related pathology. Even if they had been inclined to use it, effective sunscreen was not generally available until the early 1970s.

The patient depicted here has a typical collection of the pre-cancerous sun damage known as dermatoheliosis: solar elastosis, actinic keratoses, telangiectasias, and solar atrophy (which affects the arms more than the face). The latter, along with the effects of wind, heat, cold, smoking, and drinking alcohol, constitute the main causes of extrinsic aging.

TREATMENT

Short of heroic efforts, not much will be done for this patient’s dermatoheliosis. However, he was strongly advised to return to dermatology twice a year to watch for the arrival of the basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas that are almost certainly headed his way.

ANSWER

The correct answer is dermatoheliosis (choice “d”), also correctly termed photoaging. This condition manifests as a number of specific skin changes, including the items named (choices “a,” “b,” and “c”)—all of which were present on this patient.

DISCUSSION

The consequences of chronic overexposure to UV radiation constitute the most common reason patients present to dermatology practices in the United States. The bulk of this damage takes decades to appear, by which time patients have forgotten about their earlier sun exposure (in fact, they often deny any exposure) and even the painful sunburns that taught them to avoid the sun in the first place.

In general, the effects of sunburns sustained in childhood or young adulthood do not usually manifest until the patient is in his/her 50s or 60s, although patients who are less sun-tolerant (our definition of “fair”) may show signs of damage considerably earlier.

However, with the popularity of artificial tanning among teenagers (and even preteens in some cases), evidence of sun damage is being seen at younger ages than ever. Basal cell carcinomas, once unheard of in teenagers, are being found with increasing frequency in this age-group. In patients ages 12 to 15, there has been a 100-fold increase in the incidence of melanoma—theorized to be due, in part, to the effects of artificial tanning.

This particular patient is typical of cases in which sun damage was obtained more passively. At one time in the US, having a tan was decidedly unfashionable; it marked one as a member of “the lower classes.” But that all began to change after WWI: Hemlines and hairlines rose, Prohibition created a new generation of drinkers and scofflaws, clothing began to be more revealing, and suddenly it was fashionable for women to shave their legs and get a tan.

About that same time, many men began to ignore the long-held tradition of wearing hats and long sleeves when outside, inevitably tanned, and thus gained approval from the opposite sex. Most went off to war in the 1940s, many to the Pacific theater, where they had even more exposure to the sun.

Following WWII, a great number of these men returned to their jobs as farmers, ranchers, or construction workers. Golfing became the “in” sport during leisure time. It’s this generation we’re seeing now for sun-related pathology. Even if they had been inclined to use it, effective sunscreen was not generally available until the early 1970s.

The patient depicted here has a typical collection of the pre-cancerous sun damage known as dermatoheliosis: solar elastosis, actinic keratoses, telangiectasias, and solar atrophy (which affects the arms more than the face). The latter, along with the effects of wind, heat, cold, smoking, and drinking alcohol, constitute the main causes of extrinsic aging.

TREATMENT

Short of heroic efforts, not much will be done for this patient’s dermatoheliosis. However, he was strongly advised to return to dermatology twice a year to watch for the arrival of the basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas that are almost certainly headed his way.

During a recent trip, this 77-year-old man stayed in a hotel in which the bathroom lighting was considerably brighter than that at home—allowing him to see a number of skin changes he hadn’t noticed before. As a result, he presents to dermatology for an evaluation. The patient’s forehead, as well as his cheeks and nose, look curiously mottled (pink and white), with a rough, scar-like, pebbly surface that resembles chicken skin. There are also numerous 1- to 3-mm rough, scaly, papular lesions and multiple faint telangiectasias. In sun-exposed areas, such as his hands and arms, the skin is rough, dry, and exceptionally thin, with light and dark color changes; this is in sharp contrast to the relatively pristine texture and uniformly light color of the volar forearms and other areas that are not exposed to the sun. History taking reveals that, as a young man, the patient spent a great deal of time outdoors, both at work and in his free time. He never wore a hat or used any other form of sun protection. Since age 50, he has had several skin cancers removed from his face and back. Despite this, he is not seeing a dermatology provider regularly.

Wife Wants Husband’s “Zits” Gone!

ANSWER

The correct answer is dilated pore of Winer (choice “b”), a hair structure anomaly discussed below. Sebaceous cysts (choice “a”) often present with a surface punctum, but the depth and appearance of this pore are not consistent with a simple punctum. The same could be said of the other two choices: ice-pick scar secondary to acne (choice “c”) and ingrown hair (choice “d”).

DISCUSSION

Dilated pore of Winer is actually a tumor of the intraepidermal follicle and related infundibulum of the pilosebaceous apparatus, a fact confirmed by immunohistochemical studies. It has no implication for health, but its appearance is occasionally distressing. Unfortunately, this patient has matching dilated pores on either side of his nose.

These scar-like pits are most commonly seen on the face, especially the maxillae. Even though they resemble one another, dilated pore of Winer differs significantly from a simple comedone: The former is considerably deeper, as well as markedly different in structure.

TREATMENT

The only effective treatment for dilated pore of Winer is surgical excision, which is easily accomplished under local anesthesia. A 4- to 5-mm punch biopsy tool is introduced into the skin at the same angle as the course of the pore, then taken down to adipose tissue, which ensures complete removal. Two interrupted skin sutures serve to convert the round punch defect into a linear wound, preferably matching skin tension lines. The tissue thus removed is always sent for pathologic examination to rule out basal cell carcinoma.

But for the vast majority of patients affected by dilated pore of Winer, the best treatment is to leave the lesions alone.

ANSWER

The correct answer is dilated pore of Winer (choice “b”), a hair structure anomaly discussed below. Sebaceous cysts (choice “a”) often present with a surface punctum, but the depth and appearance of this pore are not consistent with a simple punctum. The same could be said of the other two choices: ice-pick scar secondary to acne (choice “c”) and ingrown hair (choice “d”).

DISCUSSION

Dilated pore of Winer is actually a tumor of the intraepidermal follicle and related infundibulum of the pilosebaceous apparatus, a fact confirmed by immunohistochemical studies. It has no implication for health, but its appearance is occasionally distressing. Unfortunately, this patient has matching dilated pores on either side of his nose.

These scar-like pits are most commonly seen on the face, especially the maxillae. Even though they resemble one another, dilated pore of Winer differs significantly from a simple comedone: The former is considerably deeper, as well as markedly different in structure.

TREATMENT

The only effective treatment for dilated pore of Winer is surgical excision, which is easily accomplished under local anesthesia. A 4- to 5-mm punch biopsy tool is introduced into the skin at the same angle as the course of the pore, then taken down to adipose tissue, which ensures complete removal. Two interrupted skin sutures serve to convert the round punch defect into a linear wound, preferably matching skin tension lines. The tissue thus removed is always sent for pathologic examination to rule out basal cell carcinoma.

But for the vast majority of patients affected by dilated pore of Winer, the best treatment is to leave the lesions alone.

ANSWER

The correct answer is dilated pore of Winer (choice “b”), a hair structure anomaly discussed below. Sebaceous cysts (choice “a”) often present with a surface punctum, but the depth and appearance of this pore are not consistent with a simple punctum. The same could be said of the other two choices: ice-pick scar secondary to acne (choice “c”) and ingrown hair (choice “d”).

DISCUSSION

Dilated pore of Winer is actually a tumor of the intraepidermal follicle and related infundibulum of the pilosebaceous apparatus, a fact confirmed by immunohistochemical studies. It has no implication for health, but its appearance is occasionally distressing. Unfortunately, this patient has matching dilated pores on either side of his nose.

These scar-like pits are most commonly seen on the face, especially the maxillae. Even though they resemble one another, dilated pore of Winer differs significantly from a simple comedone: The former is considerably deeper, as well as markedly different in structure.

TREATMENT

The only effective treatment for dilated pore of Winer is surgical excision, which is easily accomplished under local anesthesia. A 4- to 5-mm punch biopsy tool is introduced into the skin at the same angle as the course of the pore, then taken down to adipose tissue, which ensures complete removal. Two interrupted skin sutures serve to convert the round punch defect into a linear wound, preferably matching skin tension lines. The tissue thus removed is always sent for pathologic examination to rule out basal cell carcinoma.

But for the vast majority of patients affected by dilated pore of Winer, the best treatment is to leave the lesions alone.

A 52-year-old man self-refers to dermatology, at his wife’s insistence, for evaluation of “big black-heads” that have been present on his maxillae for as long as he can remember. Periodically, he ex-presses cheesy, odoriferous material from them. He denies ever experiencing trauma in the area, and there is no history of other skin problems (eg, acne). His wife wants him to get these “black-heads” removed, because there is “dirt” in them. Small “holes” are seen on each side of the nose, about 3 cm lateral to midline. Each lesion is 2 to 3 mm wide and obviously deep. There is no comedonal material or protruding hair seen in the lesions; the surrounding skin is unchanged. Induration is absent in or around the lesions. No signs of active acne are seen elsewhere.

A persistent, nonhealing lesion in a transplant patient

HISTORY

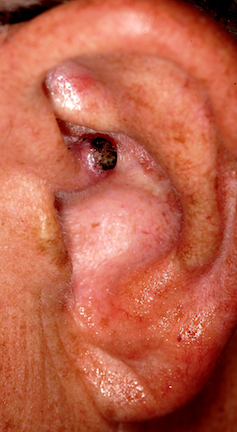

A 64 year-old man is referred to dermatology for investigation of a non-healing asymptomatic lesion present on his left ear for slightly less than a year. His history included his having had a number of basal cell carcinomas removed from his face over the years, and, of course, a history of excessive sun exposure as a young man.

Additional history-taking revealed his having had a kidney transplant 5 years previously, for which he was still under the care of the transplant team, including taking immunosuppressive medications. He had been warned by his transplant providers of the increased risk of skin cancers associated with these medications.

EXAMINATION

A 1 cm friable nodule on the left helical crus could readily be seen, covered by thin eschar, with a faintly red base. Abundant evidence of ancient sun damage could be seen on the ear and face, including telangiectasias and solar lentigines. No nodes or other masses could be detected on palpation of the periauricular and neck regions. A generous shave biopsy of this lesion showed clear evidence of a moderately well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma.

DISCUSSION

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second-most common skin cancer, after basal cell carcinoma (BCC), but unlike the latter, SCC has a very real chance of leading to metastasis and death. 8,000 cases of nodal involvement occur in this country every year, 3,000 of which result in death from metastasis to the brain and/or lung. In general, the more well-differentiated the cancer (similar-appearing cells), the better the prognosis, but the more poorly differentiated the cells are (dissimilar appearance), the greater the chance for invasion and spread.

But several other factors determine the prognosis for any given SCC. Each anatomic site has its own pattern of spread and prognosis. In this particular case, the proximity of the cancer to the external auditory meatus predicts an increased potential for local or nodal spread. Moreover, the patient’s suppressed immune system increases the risk even further.

Approximately 15% of all SCCs occur on upper extremities, but these tend to be relatively safe, especially when sun-caused. Non-solar causation of SCC, such as from HPV, chronic arsenic exposure, or over-exposure to ionizing radiation, tends to have a worse prognosis, especially if it occurs near orifices such as the ear, vagina, mouth or in anogential regions. The size of the tumor matters as well, with tumors greater than 2 cm being increasingly prone to local invasion and metastasis compared to smaller lesions. Beyond these factors, variations in the biologic activity of individual SCCs can be unpredictable, making all SCCs considerably more worrisome than BCCs.

Relatively safe forms of SCC are common, and include intraepidermal SCC in situ, also known as Bowen’s disease, which presents as a slowly growing, fixed papulosquamous plaque on sun-exposed skin. As with all forms of sun-caused SCC, Bowen’s in more common in older, chronically sun-damaged patients.

The lateral and vertical dimensions of this man’s SCC were determined by the Mohs surgeon who excised the lesion, examining the margins of the excised tissue to insure complete removal and to detect any deeper involvement of cartilage or potential perineural involvement. Fortunately, these were not seen in his case, but the operative site was treated with radiation of the site because of the uncertainty caused by his immunosuppressive state.

Obviously, SCCs are not confined to the skin, occurring in a wide variety of areas such as the cervix, lung and oral cavity. The comments made above regarding SCC of the skin have little if any bearing on the diagnosis and treatment of internal squamous cell carcinoma, a subject far beyond the scope of this article.

LEARNING POINTS

1) Any cell in human skin can undergo malignant transformation

2) The tendency to develop SCC is held in check in part by an intact immune system.

3) Non-solar causes of SCC include HPV, chronic exposure to arsenic, and ionizing radiation exposure.

4) SCC, because of its potential for metastasis, is considered more dangerous than BCC.

5) Transplant patients are especially prone to SCC.

HISTORY

A 64 year-old man is referred to dermatology for investigation of a non-healing asymptomatic lesion present on his left ear for slightly less than a year. His history included his having had a number of basal cell carcinomas removed from his face over the years, and, of course, a history of excessive sun exposure as a young man.

Additional history-taking revealed his having had a kidney transplant 5 years previously, for which he was still under the care of the transplant team, including taking immunosuppressive medications. He had been warned by his transplant providers of the increased risk of skin cancers associated with these medications.

EXAMINATION

A 1 cm friable nodule on the left helical crus could readily be seen, covered by thin eschar, with a faintly red base. Abundant evidence of ancient sun damage could be seen on the ear and face, including telangiectasias and solar lentigines. No nodes or other masses could be detected on palpation of the periauricular and neck regions. A generous shave biopsy of this lesion showed clear evidence of a moderately well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma.

DISCUSSION

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second-most common skin cancer, after basal cell carcinoma (BCC), but unlike the latter, SCC has a very real chance of leading to metastasis and death. 8,000 cases of nodal involvement occur in this country every year, 3,000 of which result in death from metastasis to the brain and/or lung. In general, the more well-differentiated the cancer (similar-appearing cells), the better the prognosis, but the more poorly differentiated the cells are (dissimilar appearance), the greater the chance for invasion and spread.

But several other factors determine the prognosis for any given SCC. Each anatomic site has its own pattern of spread and prognosis. In this particular case, the proximity of the cancer to the external auditory meatus predicts an increased potential for local or nodal spread. Moreover, the patient’s suppressed immune system increases the risk even further.

Approximately 15% of all SCCs occur on upper extremities, but these tend to be relatively safe, especially when sun-caused. Non-solar causation of SCC, such as from HPV, chronic arsenic exposure, or over-exposure to ionizing radiation, tends to have a worse prognosis, especially if it occurs near orifices such as the ear, vagina, mouth or in anogential regions. The size of the tumor matters as well, with tumors greater than 2 cm being increasingly prone to local invasion and metastasis compared to smaller lesions. Beyond these factors, variations in the biologic activity of individual SCCs can be unpredictable, making all SCCs considerably more worrisome than BCCs.

Relatively safe forms of SCC are common, and include intraepidermal SCC in situ, also known as Bowen’s disease, which presents as a slowly growing, fixed papulosquamous plaque on sun-exposed skin. As with all forms of sun-caused SCC, Bowen’s in more common in older, chronically sun-damaged patients.

The lateral and vertical dimensions of this man’s SCC were determined by the Mohs surgeon who excised the lesion, examining the margins of the excised tissue to insure complete removal and to detect any deeper involvement of cartilage or potential perineural involvement. Fortunately, these were not seen in his case, but the operative site was treated with radiation of the site because of the uncertainty caused by his immunosuppressive state.

Obviously, SCCs are not confined to the skin, occurring in a wide variety of areas such as the cervix, lung and oral cavity. The comments made above regarding SCC of the skin have little if any bearing on the diagnosis and treatment of internal squamous cell carcinoma, a subject far beyond the scope of this article.

LEARNING POINTS

1) Any cell in human skin can undergo malignant transformation

2) The tendency to develop SCC is held in check in part by an intact immune system.

3) Non-solar causes of SCC include HPV, chronic exposure to arsenic, and ionizing radiation exposure.

4) SCC, because of its potential for metastasis, is considered more dangerous than BCC.

5) Transplant patients are especially prone to SCC.

HISTORY

A 64 year-old man is referred to dermatology for investigation of a non-healing asymptomatic lesion present on his left ear for slightly less than a year. His history included his having had a number of basal cell carcinomas removed from his face over the years, and, of course, a history of excessive sun exposure as a young man.

Additional history-taking revealed his having had a kidney transplant 5 years previously, for which he was still under the care of the transplant team, including taking immunosuppressive medications. He had been warned by his transplant providers of the increased risk of skin cancers associated with these medications.

EXAMINATION

A 1 cm friable nodule on the left helical crus could readily be seen, covered by thin eschar, with a faintly red base. Abundant evidence of ancient sun damage could be seen on the ear and face, including telangiectasias and solar lentigines. No nodes or other masses could be detected on palpation of the periauricular and neck regions. A generous shave biopsy of this lesion showed clear evidence of a moderately well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma.

DISCUSSION

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second-most common skin cancer, after basal cell carcinoma (BCC), but unlike the latter, SCC has a very real chance of leading to metastasis and death. 8,000 cases of nodal involvement occur in this country every year, 3,000 of which result in death from metastasis to the brain and/or lung. In general, the more well-differentiated the cancer (similar-appearing cells), the better the prognosis, but the more poorly differentiated the cells are (dissimilar appearance), the greater the chance for invasion and spread.

But several other factors determine the prognosis for any given SCC. Each anatomic site has its own pattern of spread and prognosis. In this particular case, the proximity of the cancer to the external auditory meatus predicts an increased potential for local or nodal spread. Moreover, the patient’s suppressed immune system increases the risk even further.

Approximately 15% of all SCCs occur on upper extremities, but these tend to be relatively safe, especially when sun-caused. Non-solar causation of SCC, such as from HPV, chronic arsenic exposure, or over-exposure to ionizing radiation, tends to have a worse prognosis, especially if it occurs near orifices such as the ear, vagina, mouth or in anogential regions. The size of the tumor matters as well, with tumors greater than 2 cm being increasingly prone to local invasion and metastasis compared to smaller lesions. Beyond these factors, variations in the biologic activity of individual SCCs can be unpredictable, making all SCCs considerably more worrisome than BCCs.

Relatively safe forms of SCC are common, and include intraepidermal SCC in situ, also known as Bowen’s disease, which presents as a slowly growing, fixed papulosquamous plaque on sun-exposed skin. As with all forms of sun-caused SCC, Bowen’s in more common in older, chronically sun-damaged patients.

The lateral and vertical dimensions of this man’s SCC were determined by the Mohs surgeon who excised the lesion, examining the margins of the excised tissue to insure complete removal and to detect any deeper involvement of cartilage or potential perineural involvement. Fortunately, these were not seen in his case, but the operative site was treated with radiation of the site because of the uncertainty caused by his immunosuppressive state.

Obviously, SCCs are not confined to the skin, occurring in a wide variety of areas such as the cervix, lung and oral cavity. The comments made above regarding SCC of the skin have little if any bearing on the diagnosis and treatment of internal squamous cell carcinoma, a subject far beyond the scope of this article.

LEARNING POINTS

1) Any cell in human skin can undergo malignant transformation

2) The tendency to develop SCC is held in check in part by an intact immune system.

3) Non-solar causes of SCC include HPV, chronic exposure to arsenic, and ionizing radiation exposure.

4) SCC, because of its potential for metastasis, is considered more dangerous than BCC.

5) Transplant patients are especially prone to SCC.

After 15 Years, Still Losing Hair, Only Faster

ANSWER

This is a classic clinical picture of androgenetic alopecia (choice “a”). See discussion for more details.

Alopecia areata (choice “b”) usually manifests acutely and leads to complete hair loss in a well-defined, annular pattern. It typically resolves on its own, with or without treatment.

Telogen effluvium (choice “c”) involves generalized hair loss without a pattern. The hair is actually “lost,” meaning markedly increased amounts of hair are seen in the comb, brush, sink, or shower. This results in an increasingly visible scalp.

Without a clear clinical picture of alopecia, a biopsy might have been indicated—primarily to rule out conditions such as lupus erythematosus (choice “d”), which can involve hair loss of various kinds. The negative ANA result obtained by the patient’s primary care provider helped rule out this diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

Androgenetic alopecia (AGA) affects both men and women, though the latter begin to develop it about 10 years later, on average, than men do. Among women, 13% develop AGA before menopause, while 75% note its appearance postmenopausally.

In both sexes, AGA results from the gradual conversion of terminal hairs to vellus hairs, with miniaturization of the follicles. Hair loss in men starts in the vertex, followed by bitemporal recession. In women, AGA primarily affects the crown of the scalp, often with partial preservation of the frontal hairline.

Dihydrotestosterone (DHT) appears to be the main culprit; testosterone is converted to DHT by means of the enzyme 5α-reductase. One of the most effective medications for AGA in men has been finasteride, which blocks the effects of 5α-reductase and can at least slow the rate of hair loss. Unfortunately, finasteride does not appear to be effective in treating AGA in women.

Women do, however, appear to respond to minoxidil, a topically applied solution, better than men. The response is moderate at best, and any hair gained is lost if the treatment is discontinued. Interestingly, the stronger 5% solution of minoxidil in women does not produce any demonstrable improvement over that seen with the 2% solution.

From a practical diagnostic standpoint, it is quite common for women with longstanding mild to moderate AGA to present with an acute episode of telogen effluvium (TE), in which hair all over the scalp falls out. Careful history taking is necessary to tease these stories apart, since TE will typically resolve on its own. The most common causes of TE, in my experience, are stress, extreme weight loss, and as a consequence of general anesthesia. For unknown reasons, TE is almost nonexistent in men.

TREATMENT

This patient chose to use 5% OTC minoxidil, an antihypertensive with an unknown mode of action in AGA. She’ll confine its application to the affected areas of the scalp, since unwanted hair growth has been reported on the face with the use of this medication.

ANSWER

This is a classic clinical picture of androgenetic alopecia (choice “a”). See discussion for more details.

Alopecia areata (choice “b”) usually manifests acutely and leads to complete hair loss in a well-defined, annular pattern. It typically resolves on its own, with or without treatment.

Telogen effluvium (choice “c”) involves generalized hair loss without a pattern. The hair is actually “lost,” meaning markedly increased amounts of hair are seen in the comb, brush, sink, or shower. This results in an increasingly visible scalp.

Without a clear clinical picture of alopecia, a biopsy might have been indicated—primarily to rule out conditions such as lupus erythematosus (choice “d”), which can involve hair loss of various kinds. The negative ANA result obtained by the patient’s primary care provider helped rule out this diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

Androgenetic alopecia (AGA) affects both men and women, though the latter begin to develop it about 10 years later, on average, than men do. Among women, 13% develop AGA before menopause, while 75% note its appearance postmenopausally.

In both sexes, AGA results from the gradual conversion of terminal hairs to vellus hairs, with miniaturization of the follicles. Hair loss in men starts in the vertex, followed by bitemporal recession. In women, AGA primarily affects the crown of the scalp, often with partial preservation of the frontal hairline.

Dihydrotestosterone (DHT) appears to be the main culprit; testosterone is converted to DHT by means of the enzyme 5α-reductase. One of the most effective medications for AGA in men has been finasteride, which blocks the effects of 5α-reductase and can at least slow the rate of hair loss. Unfortunately, finasteride does not appear to be effective in treating AGA in women.

Women do, however, appear to respond to minoxidil, a topically applied solution, better than men. The response is moderate at best, and any hair gained is lost if the treatment is discontinued. Interestingly, the stronger 5% solution of minoxidil in women does not produce any demonstrable improvement over that seen with the 2% solution.

From a practical diagnostic standpoint, it is quite common for women with longstanding mild to moderate AGA to present with an acute episode of telogen effluvium (TE), in which hair all over the scalp falls out. Careful history taking is necessary to tease these stories apart, since TE will typically resolve on its own. The most common causes of TE, in my experience, are stress, extreme weight loss, and as a consequence of general anesthesia. For unknown reasons, TE is almost nonexistent in men.

TREATMENT

This patient chose to use 5% OTC minoxidil, an antihypertensive with an unknown mode of action in AGA. She’ll confine its application to the affected areas of the scalp, since unwanted hair growth has been reported on the face with the use of this medication.

ANSWER

This is a classic clinical picture of androgenetic alopecia (choice “a”). See discussion for more details.

Alopecia areata (choice “b”) usually manifests acutely and leads to complete hair loss in a well-defined, annular pattern. It typically resolves on its own, with or without treatment.

Telogen effluvium (choice “c”) involves generalized hair loss without a pattern. The hair is actually “lost,” meaning markedly increased amounts of hair are seen in the comb, brush, sink, or shower. This results in an increasingly visible scalp.

Without a clear clinical picture of alopecia, a biopsy might have been indicated—primarily to rule out conditions such as lupus erythematosus (choice “d”), which can involve hair loss of various kinds. The negative ANA result obtained by the patient’s primary care provider helped rule out this diagnosis.

DISCUSSION