User login

The Most Problematic Warts Have No Sure Treatment

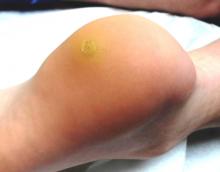

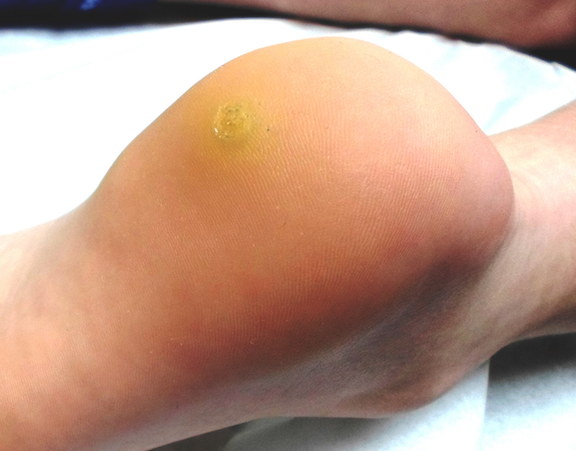

A 23-year-old woman presents with an 18-month history of a lesion on her heel that has persisted despite treatment with an OTC salicylic acid preparation, several attempts with an OTC “freezing unit,” and cryotherapy performed by her primary care provider. The lesion is continually aggravated by weight-bearing.

As a child, she reports, she had several warts on her hands. However, they resolved without treatment.

EXAMINATION

The lesion in question is almost 1 cm in diameter and clearly intradermal in nature. It has a rough, dry feel. On its surface, there are tiny black dots. Normal skin lines flow over the surface of the heel until they reach the lesion; at that point, they curve around its periphery and rejoin on the other side.

DISCUSSION

These features—the black dots, which represent vertically aligned thrombosed capillaries, and the curving skin lines—are diagnostic for plantar warts. This case represents a classic plantar (not “planter”) wart, so named because of its location, not because it has anything to do with planting.

There are good reasons for distinguishing plantar from ordinary warts. For one thing, the outer layer of skin on the sole (the stratum lucidum) is avascular and quite thick, allowing the wart not only to become relatively deep but also to escape detection by the immune system. Since they are almost always on the weight-bearing surface of the sole, even small warts can cause considerable discomfort as they grow.

These same features—the depth and location of the wart—also get in the way of successful treatment, since it may or may not reach the deep margin of the lesion without undue pain and scarring. As in other areas of medicine, we in dermatology strive to avoid treatments that are worse than the disease.

While this is especially true with children, many adults are intolerant of the usual liquid nitrogen treatment (cryotherapy), not only because of the pain associated with the initial application but also because the blistering and pain can persist for days afterward. Perhaps worst of all, no treatment modality is a “sure thing,” so the patient may go through the process and get very little in return.

This combination of issues is why, in dermatology, the first thing we do is to discuss the situation thoroughly with the patient (and parents). My typical conversation starts like this: “You know, you’ve brought us a very difficult problem to treat. This is an infection caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV), which can grow deep and does not elicit much of an immune response. We don’t have drugs or shots to kill the virus. And, as if this were not enough of a problem, none of our treatment choices is remotely perfect. They might not work, and most are sure to cause pain.” Then, of course, I review the treatment options one by one.

TREATMENT

If the patient is lucky and the wart is small and shallow, we typically treat with a liquid nitrogen gun, almost always through a 3 to 5 mm speculum to concentrate the spray. We might shave down the surface of the wart with a #10 blade first, to reduce the thickness and increase the likelihood of successful treatment.

In my opinion, based on many years of treating these warts, using a cotton-tipped applicator to apply the liquid nitrogen is a waste of time and pain. Warts on thin-skinned areas such as arms and legs might be the exception.

Often, with small children, I discuss another option with the parents: that of doing nothing. Warts are warts, not dangerous in any way. Virtually all of them will eventually resolve on their own. The trouble is, of course, that we can’t promise when this will happen, or how big the wart might become in the interim.

There are nonpainful treatment choices, albeit ones with little chance of ultimate success. These include the OTC wart treatment products, virtually all of which contain salicylic acid as their main ingredient. Applied two or three times a week, these products can at least hold smaller warts in check, and could result in a cure.

Much the same could be said for products like cantharidin, a chemical derived from blister beetles, which causes nonpainful and slight blistering at the site. Unfortunately, we can’t prescribe it, which dooms the patient to returning to the office every two or three weeks. As with many such treatment options, it is unlikely to result in a cure.

Another treatment option is dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB) as the main ingredient in a compounded product. DNCB is a potent T-cell stimulator—another way of saying that we can make the patient allergic to the substance, bringing the body’s immune system to bear on the treated area, producing slight blistering and hopefully destroying the wart in the process. It has to be used with caution, lest the substance wind up on unaffected skin. Parents need to understand that DNCB is slow to work (often taking a month or more) and again, by no means a sure thing. Squaric acid is an alternative to DNCB.

Surgical curettage and electrodessication, under local anesthesia, is potentially the most effective treatment we have for plantar warts—but as you might imagine, piercing the sole of a young child’s foot with a 30-gauge needle is rarely our first choice. It’s the method we used before liquid nitrogen was widely available, and it was a nightmare for all involved. Three outcomes were possible, two quite negative: Serious post-procedure pain and scarring were almost certain. But worst of all, the wart could easily return despite all that. The only time I use this is when the plantar wart is totally resistant to treatment and so large as to interfere with walking.

TAKE-AWAY LEARNING POINTS

• The reason there are 20 or more treatments for warts is that none are remotely perfect.

• Plantar warts are a special problem because they develop on weight-bearing portions of the sole, growing inward (endophytic) in a thick skin layer that allows the virus to avoid detection by the immune system. Plantar warts often cause pain, which treatment can worsen.

• Parents/patients need to understand all of this prior to selecting an appropriate treatment choice.

• They also need to understand that warts do not have to be treated. Most will resolve on their own, eventually.

• Terrorizing children is to be avoided if at all possible. Parents may want their child’s warts to be “taken care of,” but they need to understand this may not be possible.

• Consider referral of problematic plantar warts to dermatology.

A 23-year-old woman presents with an 18-month history of a lesion on her heel that has persisted despite treatment with an OTC salicylic acid preparation, several attempts with an OTC “freezing unit,” and cryotherapy performed by her primary care provider. The lesion is continually aggravated by weight-bearing.

As a child, she reports, she had several warts on her hands. However, they resolved without treatment.

EXAMINATION

The lesion in question is almost 1 cm in diameter and clearly intradermal in nature. It has a rough, dry feel. On its surface, there are tiny black dots. Normal skin lines flow over the surface of the heel until they reach the lesion; at that point, they curve around its periphery and rejoin on the other side.

DISCUSSION

These features—the black dots, which represent vertically aligned thrombosed capillaries, and the curving skin lines—are diagnostic for plantar warts. This case represents a classic plantar (not “planter”) wart, so named because of its location, not because it has anything to do with planting.

There are good reasons for distinguishing plantar from ordinary warts. For one thing, the outer layer of skin on the sole (the stratum lucidum) is avascular and quite thick, allowing the wart not only to become relatively deep but also to escape detection by the immune system. Since they are almost always on the weight-bearing surface of the sole, even small warts can cause considerable discomfort as they grow.

These same features—the depth and location of the wart—also get in the way of successful treatment, since it may or may not reach the deep margin of the lesion without undue pain and scarring. As in other areas of medicine, we in dermatology strive to avoid treatments that are worse than the disease.

While this is especially true with children, many adults are intolerant of the usual liquid nitrogen treatment (cryotherapy), not only because of the pain associated with the initial application but also because the blistering and pain can persist for days afterward. Perhaps worst of all, no treatment modality is a “sure thing,” so the patient may go through the process and get very little in return.

This combination of issues is why, in dermatology, the first thing we do is to discuss the situation thoroughly with the patient (and parents). My typical conversation starts like this: “You know, you’ve brought us a very difficult problem to treat. This is an infection caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV), which can grow deep and does not elicit much of an immune response. We don’t have drugs or shots to kill the virus. And, as if this were not enough of a problem, none of our treatment choices is remotely perfect. They might not work, and most are sure to cause pain.” Then, of course, I review the treatment options one by one.

TREATMENT

If the patient is lucky and the wart is small and shallow, we typically treat with a liquid nitrogen gun, almost always through a 3 to 5 mm speculum to concentrate the spray. We might shave down the surface of the wart with a #10 blade first, to reduce the thickness and increase the likelihood of successful treatment.

In my opinion, based on many years of treating these warts, using a cotton-tipped applicator to apply the liquid nitrogen is a waste of time and pain. Warts on thin-skinned areas such as arms and legs might be the exception.

Often, with small children, I discuss another option with the parents: that of doing nothing. Warts are warts, not dangerous in any way. Virtually all of them will eventually resolve on their own. The trouble is, of course, that we can’t promise when this will happen, or how big the wart might become in the interim.

There are nonpainful treatment choices, albeit ones with little chance of ultimate success. These include the OTC wart treatment products, virtually all of which contain salicylic acid as their main ingredient. Applied two or three times a week, these products can at least hold smaller warts in check, and could result in a cure.

Much the same could be said for products like cantharidin, a chemical derived from blister beetles, which causes nonpainful and slight blistering at the site. Unfortunately, we can’t prescribe it, which dooms the patient to returning to the office every two or three weeks. As with many such treatment options, it is unlikely to result in a cure.

Another treatment option is dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB) as the main ingredient in a compounded product. DNCB is a potent T-cell stimulator—another way of saying that we can make the patient allergic to the substance, bringing the body’s immune system to bear on the treated area, producing slight blistering and hopefully destroying the wart in the process. It has to be used with caution, lest the substance wind up on unaffected skin. Parents need to understand that DNCB is slow to work (often taking a month or more) and again, by no means a sure thing. Squaric acid is an alternative to DNCB.

Surgical curettage and electrodessication, under local anesthesia, is potentially the most effective treatment we have for plantar warts—but as you might imagine, piercing the sole of a young child’s foot with a 30-gauge needle is rarely our first choice. It’s the method we used before liquid nitrogen was widely available, and it was a nightmare for all involved. Three outcomes were possible, two quite negative: Serious post-procedure pain and scarring were almost certain. But worst of all, the wart could easily return despite all that. The only time I use this is when the plantar wart is totally resistant to treatment and so large as to interfere with walking.

TAKE-AWAY LEARNING POINTS

• The reason there are 20 or more treatments for warts is that none are remotely perfect.

• Plantar warts are a special problem because they develop on weight-bearing portions of the sole, growing inward (endophytic) in a thick skin layer that allows the virus to avoid detection by the immune system. Plantar warts often cause pain, which treatment can worsen.

• Parents/patients need to understand all of this prior to selecting an appropriate treatment choice.

• They also need to understand that warts do not have to be treated. Most will resolve on their own, eventually.

• Terrorizing children is to be avoided if at all possible. Parents may want their child’s warts to be “taken care of,” but they need to understand this may not be possible.

• Consider referral of problematic plantar warts to dermatology.

A 23-year-old woman presents with an 18-month history of a lesion on her heel that has persisted despite treatment with an OTC salicylic acid preparation, several attempts with an OTC “freezing unit,” and cryotherapy performed by her primary care provider. The lesion is continually aggravated by weight-bearing.

As a child, she reports, she had several warts on her hands. However, they resolved without treatment.

EXAMINATION

The lesion in question is almost 1 cm in diameter and clearly intradermal in nature. It has a rough, dry feel. On its surface, there are tiny black dots. Normal skin lines flow over the surface of the heel until they reach the lesion; at that point, they curve around its periphery and rejoin on the other side.

DISCUSSION

These features—the black dots, which represent vertically aligned thrombosed capillaries, and the curving skin lines—are diagnostic for plantar warts. This case represents a classic plantar (not “planter”) wart, so named because of its location, not because it has anything to do with planting.

There are good reasons for distinguishing plantar from ordinary warts. For one thing, the outer layer of skin on the sole (the stratum lucidum) is avascular and quite thick, allowing the wart not only to become relatively deep but also to escape detection by the immune system. Since they are almost always on the weight-bearing surface of the sole, even small warts can cause considerable discomfort as they grow.

These same features—the depth and location of the wart—also get in the way of successful treatment, since it may or may not reach the deep margin of the lesion without undue pain and scarring. As in other areas of medicine, we in dermatology strive to avoid treatments that are worse than the disease.

While this is especially true with children, many adults are intolerant of the usual liquid nitrogen treatment (cryotherapy), not only because of the pain associated with the initial application but also because the blistering and pain can persist for days afterward. Perhaps worst of all, no treatment modality is a “sure thing,” so the patient may go through the process and get very little in return.

This combination of issues is why, in dermatology, the first thing we do is to discuss the situation thoroughly with the patient (and parents). My typical conversation starts like this: “You know, you’ve brought us a very difficult problem to treat. This is an infection caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV), which can grow deep and does not elicit much of an immune response. We don’t have drugs or shots to kill the virus. And, as if this were not enough of a problem, none of our treatment choices is remotely perfect. They might not work, and most are sure to cause pain.” Then, of course, I review the treatment options one by one.

TREATMENT

If the patient is lucky and the wart is small and shallow, we typically treat with a liquid nitrogen gun, almost always through a 3 to 5 mm speculum to concentrate the spray. We might shave down the surface of the wart with a #10 blade first, to reduce the thickness and increase the likelihood of successful treatment.

In my opinion, based on many years of treating these warts, using a cotton-tipped applicator to apply the liquid nitrogen is a waste of time and pain. Warts on thin-skinned areas such as arms and legs might be the exception.

Often, with small children, I discuss another option with the parents: that of doing nothing. Warts are warts, not dangerous in any way. Virtually all of them will eventually resolve on their own. The trouble is, of course, that we can’t promise when this will happen, or how big the wart might become in the interim.

There are nonpainful treatment choices, albeit ones with little chance of ultimate success. These include the OTC wart treatment products, virtually all of which contain salicylic acid as their main ingredient. Applied two or three times a week, these products can at least hold smaller warts in check, and could result in a cure.

Much the same could be said for products like cantharidin, a chemical derived from blister beetles, which causes nonpainful and slight blistering at the site. Unfortunately, we can’t prescribe it, which dooms the patient to returning to the office every two or three weeks. As with many such treatment options, it is unlikely to result in a cure.

Another treatment option is dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB) as the main ingredient in a compounded product. DNCB is a potent T-cell stimulator—another way of saying that we can make the patient allergic to the substance, bringing the body’s immune system to bear on the treated area, producing slight blistering and hopefully destroying the wart in the process. It has to be used with caution, lest the substance wind up on unaffected skin. Parents need to understand that DNCB is slow to work (often taking a month or more) and again, by no means a sure thing. Squaric acid is an alternative to DNCB.

Surgical curettage and electrodessication, under local anesthesia, is potentially the most effective treatment we have for plantar warts—but as you might imagine, piercing the sole of a young child’s foot with a 30-gauge needle is rarely our first choice. It’s the method we used before liquid nitrogen was widely available, and it was a nightmare for all involved. Three outcomes were possible, two quite negative: Serious post-procedure pain and scarring were almost certain. But worst of all, the wart could easily return despite all that. The only time I use this is when the plantar wart is totally resistant to treatment and so large as to interfere with walking.

TAKE-AWAY LEARNING POINTS

• The reason there are 20 or more treatments for warts is that none are remotely perfect.

• Plantar warts are a special problem because they develop on weight-bearing portions of the sole, growing inward (endophytic) in a thick skin layer that allows the virus to avoid detection by the immune system. Plantar warts often cause pain, which treatment can worsen.

• Parents/patients need to understand all of this prior to selecting an appropriate treatment choice.

• They also need to understand that warts do not have to be treated. Most will resolve on their own, eventually.

• Terrorizing children is to be avoided if at all possible. Parents may want their child’s warts to be “taken care of,” but they need to understand this may not be possible.

• Consider referral of problematic plantar warts to dermatology.

The Truth About Poison Ivy

Picture it: It’s 1948. You’re 12, and you’re itching. Then a rash develops. Your mother says you probably have poison ivy—and sure enough, you’ve been thrashing about in the woods where they told you not to go (but you didn’t listen). It never hurt you before, but now the blisters are coming, in long streaks, on your legs and arms. There’s no sleeping and no holding still, not even in church. The itching is so bad, and vinegar and the pink stuff they put on you don’t help at all; they only call more attention to your rash. Everyone, even your own family, is giving you a wide berth, because they all believe poison ivy is contagious.

Six weeks later, the rash and itching are finally gone—but not the memory of this common condition, for which no effective treatment will exist until topical corticosteroids are introduced in 1951.

All these years later, many myths about poison ivy persist. Some are such powerful misconceptions that many people cannot be swayed from them, even by facts. For example, poison ivy is not in the least contagious. Nor is it caused by any kind of “poison.”

The culprit is an oleoresin known as urushiol. This oily resin is contained in the stems, leaves, and flowers of plants from the Toxicodendron genus, which includes poison ivy (by far the most common source), poison oak (found almost exclusively west of the Rockies) and poison sumac (found in limited areas of the southeastern United States). Similar reactions can be caused by exposure to other botanicals, including ficus, fern, fig, mango, and Japanese lacquer trees. (Another member of the Toxicodendron family is the Rhus tree, found mostly in Australia, where it is notorious for causing rashes.)

A history of recent exposure to the great outdoors can therefore usually be obtained, although exposure can also occur through contact with pets or with the clothing of family members who have been exposed. A live plant is not necessary. Many a victim has acquired poison ivy from clearing brush or handling firewood in the dead of winter. (The antigen can also be acquired through an airborne route, such as from the smoke generated by burning brush—even at a considerable distance.) Repeated exposure to poison ivy over several years’ time is required, which explains why children and city-dwelling adults may appear to be immune.

Typically, the blisters begin to appear within 12 to 48 hours of exposure (with some notable exceptions). Much to the consternation of the patient and family, new lesions can continue to manifest for up to two weeks after initial exposure, which is probably why so many people think poison ivy is contagious. The truth is, there is no urushiol in the fluid from the blisters, nor is the antigen “poison” in any way. In short, poison ivy cannot be transmitted from one person to another.

Poison ivy rashes manifest in several different ways. The most common is a type IV delayed hypersensitivity reaction, with pathognomic linear streaks of erythematous patches of edematous, blistery skin. Figure 1 shows a classic linear lesion on the face of a 69-year-old woman who had cleaned out her fence line a few days previously. This particular patient had a similar rash on her chest.

Figure 2 shows a more atypical form of poison ivy, entirely lacking linear lesions or even blisters. The patient’s rash was widespread, but concentrated on popliteal and antecubital areas and medial thighs. It comprised large sheets of highly erythematous skin, in the centers of which were targetoid reddish blue patches. This is a variant of erythema multiforme, which is by definition a secondary condition usually triggered by bugs (strep, herpes simplex virus) or drugs (sulfa, tetracycline, aspirin, penicillin) but occasionally by an exaggerated reaction to antigens such as poison ivy. In this case, this 185-pound 47-year-old woman and her family acquired poison ivy while picking wildflowers in wet weeds—bringing a rapid end to the family vacation.

The most effective treatment for severe, symptomatic poison ivy is the use of systemic glucocorticoids (eg, prednisone) and/or intramuscular injection of a corticosteroid (eg, triamcinolone). Patient 2’s condition was so severe that she couldn’t sleep, eat, or even drive a car. (Interestingly enough, she was the only one who sought medical evaluation. The rest of her family was content to clean out the local pharmacy’s supply of calamine lotion and diphenhydramine capsules.) Severity of this nature demands serious medication—in this case, a two-week taper of prednisone (from 60 mg down to 20 mg) plus an IM injection of triamcinolone (60 mg).

We made this treatment decision with the knowledge that such doses might produce adverse effects, including an increase in appetite, fluid accumulation, irritability, and sleeplessness. Before prescribing these medications, the potential effects were thoroughly discussed with the patient and a history was taken to rule out antecedent diabetes, severe hypertension, intercurrent infection, peptic ulcer disease, or bipolar affective disorder, all of which could be worsened by the use of corticosteroids.

So-called “dosepaks” of corticosteroids are far too weak for such a serious condition, and topical medications—even the most powerful—will be of little benefit. I gave Patient 2 one more thing: a prescription for hydroxyzine hydrochloride (25 mg tablets, to be taken at bedtime), both for sedative and antipruritic effects. For milder cases of poison ivy, I often advise no treatment except topical because the one thing that can be depended on is that poison ivy will resolve on its own, eventually.

I also educate patients about the appearance of the poison ivy plant (see Figure 3). In my part of the country (Oklahoma), where poison ivy is found in virtually every fence line, every creek bank, and every backyard, most people don’t really know what it looks like. Part of that confusion results from the fact that it can take a number of forms, including a vine, often wrapped around trees, a small tree, or even a root, coursing along the ground. Its distinguishing features include the “leaves of three” in typical shapes (darts, with notches, or “thumbs” along the leaf margins), a shiny surface, and white flowers turning into berries.

TAKE-AWAY LEARNING POINTS

• Poison ivy is predominantly found east of the Rocky Mountains and poison oak almost exclusively to the west of them. Poison sumac is limited to the southeastern United States.

• Poison ivy is also known as a form of phytodermatitis, with other botanical sources such as ficus, fig, fern, mango, rhus, and Japanese lacquer trees.

• Poison ivy can grow in the form of a bush, a vine, or even a small tree. However, it also demonstrates the “leaves of three.”

• Linear blisters on an erythematous base is the classic description of a poison ivy reaction, but it can also present in a more diffuse form that concentrates on the popliteal areas and medial thighs.

• Poison ivy is not “poison.” It is the quintessential contact dermatitis, a type IV delayed hypersensitivity reaction to the oil contained in the plant.

• Poison ivy is not contagious and cannot be spread on the patient’s body or to anyone else.

Picture it: It’s 1948. You’re 12, and you’re itching. Then a rash develops. Your mother says you probably have poison ivy—and sure enough, you’ve been thrashing about in the woods where they told you not to go (but you didn’t listen). It never hurt you before, but now the blisters are coming, in long streaks, on your legs and arms. There’s no sleeping and no holding still, not even in church. The itching is so bad, and vinegar and the pink stuff they put on you don’t help at all; they only call more attention to your rash. Everyone, even your own family, is giving you a wide berth, because they all believe poison ivy is contagious.

Six weeks later, the rash and itching are finally gone—but not the memory of this common condition, for which no effective treatment will exist until topical corticosteroids are introduced in 1951.

All these years later, many myths about poison ivy persist. Some are such powerful misconceptions that many people cannot be swayed from them, even by facts. For example, poison ivy is not in the least contagious. Nor is it caused by any kind of “poison.”

The culprit is an oleoresin known as urushiol. This oily resin is contained in the stems, leaves, and flowers of plants from the Toxicodendron genus, which includes poison ivy (by far the most common source), poison oak (found almost exclusively west of the Rockies) and poison sumac (found in limited areas of the southeastern United States). Similar reactions can be caused by exposure to other botanicals, including ficus, fern, fig, mango, and Japanese lacquer trees. (Another member of the Toxicodendron family is the Rhus tree, found mostly in Australia, where it is notorious for causing rashes.)

A history of recent exposure to the great outdoors can therefore usually be obtained, although exposure can also occur through contact with pets or with the clothing of family members who have been exposed. A live plant is not necessary. Many a victim has acquired poison ivy from clearing brush or handling firewood in the dead of winter. (The antigen can also be acquired through an airborne route, such as from the smoke generated by burning brush—even at a considerable distance.) Repeated exposure to poison ivy over several years’ time is required, which explains why children and city-dwelling adults may appear to be immune.

Typically, the blisters begin to appear within 12 to 48 hours of exposure (with some notable exceptions). Much to the consternation of the patient and family, new lesions can continue to manifest for up to two weeks after initial exposure, which is probably why so many people think poison ivy is contagious. The truth is, there is no urushiol in the fluid from the blisters, nor is the antigen “poison” in any way. In short, poison ivy cannot be transmitted from one person to another.

Poison ivy rashes manifest in several different ways. The most common is a type IV delayed hypersensitivity reaction, with pathognomic linear streaks of erythematous patches of edematous, blistery skin. Figure 1 shows a classic linear lesion on the face of a 69-year-old woman who had cleaned out her fence line a few days previously. This particular patient had a similar rash on her chest.

Figure 2 shows a more atypical form of poison ivy, entirely lacking linear lesions or even blisters. The patient’s rash was widespread, but concentrated on popliteal and antecubital areas and medial thighs. It comprised large sheets of highly erythematous skin, in the centers of which were targetoid reddish blue patches. This is a variant of erythema multiforme, which is by definition a secondary condition usually triggered by bugs (strep, herpes simplex virus) or drugs (sulfa, tetracycline, aspirin, penicillin) but occasionally by an exaggerated reaction to antigens such as poison ivy. In this case, this 185-pound 47-year-old woman and her family acquired poison ivy while picking wildflowers in wet weeds—bringing a rapid end to the family vacation.

The most effective treatment for severe, symptomatic poison ivy is the use of systemic glucocorticoids (eg, prednisone) and/or intramuscular injection of a corticosteroid (eg, triamcinolone). Patient 2’s condition was so severe that she couldn’t sleep, eat, or even drive a car. (Interestingly enough, she was the only one who sought medical evaluation. The rest of her family was content to clean out the local pharmacy’s supply of calamine lotion and diphenhydramine capsules.) Severity of this nature demands serious medication—in this case, a two-week taper of prednisone (from 60 mg down to 20 mg) plus an IM injection of triamcinolone (60 mg).

We made this treatment decision with the knowledge that such doses might produce adverse effects, including an increase in appetite, fluid accumulation, irritability, and sleeplessness. Before prescribing these medications, the potential effects were thoroughly discussed with the patient and a history was taken to rule out antecedent diabetes, severe hypertension, intercurrent infection, peptic ulcer disease, or bipolar affective disorder, all of which could be worsened by the use of corticosteroids.

So-called “dosepaks” of corticosteroids are far too weak for such a serious condition, and topical medications—even the most powerful—will be of little benefit. I gave Patient 2 one more thing: a prescription for hydroxyzine hydrochloride (25 mg tablets, to be taken at bedtime), both for sedative and antipruritic effects. For milder cases of poison ivy, I often advise no treatment except topical because the one thing that can be depended on is that poison ivy will resolve on its own, eventually.

I also educate patients about the appearance of the poison ivy plant (see Figure 3). In my part of the country (Oklahoma), where poison ivy is found in virtually every fence line, every creek bank, and every backyard, most people don’t really know what it looks like. Part of that confusion results from the fact that it can take a number of forms, including a vine, often wrapped around trees, a small tree, or even a root, coursing along the ground. Its distinguishing features include the “leaves of three” in typical shapes (darts, with notches, or “thumbs” along the leaf margins), a shiny surface, and white flowers turning into berries.

TAKE-AWAY LEARNING POINTS

• Poison ivy is predominantly found east of the Rocky Mountains and poison oak almost exclusively to the west of them. Poison sumac is limited to the southeastern United States.

• Poison ivy is also known as a form of phytodermatitis, with other botanical sources such as ficus, fig, fern, mango, rhus, and Japanese lacquer trees.

• Poison ivy can grow in the form of a bush, a vine, or even a small tree. However, it also demonstrates the “leaves of three.”

• Linear blisters on an erythematous base is the classic description of a poison ivy reaction, but it can also present in a more diffuse form that concentrates on the popliteal areas and medial thighs.

• Poison ivy is not “poison.” It is the quintessential contact dermatitis, a type IV delayed hypersensitivity reaction to the oil contained in the plant.

• Poison ivy is not contagious and cannot be spread on the patient’s body or to anyone else.

Picture it: It’s 1948. You’re 12, and you’re itching. Then a rash develops. Your mother says you probably have poison ivy—and sure enough, you’ve been thrashing about in the woods where they told you not to go (but you didn’t listen). It never hurt you before, but now the blisters are coming, in long streaks, on your legs and arms. There’s no sleeping and no holding still, not even in church. The itching is so bad, and vinegar and the pink stuff they put on you don’t help at all; they only call more attention to your rash. Everyone, even your own family, is giving you a wide berth, because they all believe poison ivy is contagious.

Six weeks later, the rash and itching are finally gone—but not the memory of this common condition, for which no effective treatment will exist until topical corticosteroids are introduced in 1951.

All these years later, many myths about poison ivy persist. Some are such powerful misconceptions that many people cannot be swayed from them, even by facts. For example, poison ivy is not in the least contagious. Nor is it caused by any kind of “poison.”

The culprit is an oleoresin known as urushiol. This oily resin is contained in the stems, leaves, and flowers of plants from the Toxicodendron genus, which includes poison ivy (by far the most common source), poison oak (found almost exclusively west of the Rockies) and poison sumac (found in limited areas of the southeastern United States). Similar reactions can be caused by exposure to other botanicals, including ficus, fern, fig, mango, and Japanese lacquer trees. (Another member of the Toxicodendron family is the Rhus tree, found mostly in Australia, where it is notorious for causing rashes.)

A history of recent exposure to the great outdoors can therefore usually be obtained, although exposure can also occur through contact with pets or with the clothing of family members who have been exposed. A live plant is not necessary. Many a victim has acquired poison ivy from clearing brush or handling firewood in the dead of winter. (The antigen can also be acquired through an airborne route, such as from the smoke generated by burning brush—even at a considerable distance.) Repeated exposure to poison ivy over several years’ time is required, which explains why children and city-dwelling adults may appear to be immune.

Typically, the blisters begin to appear within 12 to 48 hours of exposure (with some notable exceptions). Much to the consternation of the patient and family, new lesions can continue to manifest for up to two weeks after initial exposure, which is probably why so many people think poison ivy is contagious. The truth is, there is no urushiol in the fluid from the blisters, nor is the antigen “poison” in any way. In short, poison ivy cannot be transmitted from one person to another.

Poison ivy rashes manifest in several different ways. The most common is a type IV delayed hypersensitivity reaction, with pathognomic linear streaks of erythematous patches of edematous, blistery skin. Figure 1 shows a classic linear lesion on the face of a 69-year-old woman who had cleaned out her fence line a few days previously. This particular patient had a similar rash on her chest.

Figure 2 shows a more atypical form of poison ivy, entirely lacking linear lesions or even blisters. The patient’s rash was widespread, but concentrated on popliteal and antecubital areas and medial thighs. It comprised large sheets of highly erythematous skin, in the centers of which were targetoid reddish blue patches. This is a variant of erythema multiforme, which is by definition a secondary condition usually triggered by bugs (strep, herpes simplex virus) or drugs (sulfa, tetracycline, aspirin, penicillin) but occasionally by an exaggerated reaction to antigens such as poison ivy. In this case, this 185-pound 47-year-old woman and her family acquired poison ivy while picking wildflowers in wet weeds—bringing a rapid end to the family vacation.

The most effective treatment for severe, symptomatic poison ivy is the use of systemic glucocorticoids (eg, prednisone) and/or intramuscular injection of a corticosteroid (eg, triamcinolone). Patient 2’s condition was so severe that she couldn’t sleep, eat, or even drive a car. (Interestingly enough, she was the only one who sought medical evaluation. The rest of her family was content to clean out the local pharmacy’s supply of calamine lotion and diphenhydramine capsules.) Severity of this nature demands serious medication—in this case, a two-week taper of prednisone (from 60 mg down to 20 mg) plus an IM injection of triamcinolone (60 mg).

We made this treatment decision with the knowledge that such doses might produce adverse effects, including an increase in appetite, fluid accumulation, irritability, and sleeplessness. Before prescribing these medications, the potential effects were thoroughly discussed with the patient and a history was taken to rule out antecedent diabetes, severe hypertension, intercurrent infection, peptic ulcer disease, or bipolar affective disorder, all of which could be worsened by the use of corticosteroids.

So-called “dosepaks” of corticosteroids are far too weak for such a serious condition, and topical medications—even the most powerful—will be of little benefit. I gave Patient 2 one more thing: a prescription for hydroxyzine hydrochloride (25 mg tablets, to be taken at bedtime), both for sedative and antipruritic effects. For milder cases of poison ivy, I often advise no treatment except topical because the one thing that can be depended on is that poison ivy will resolve on its own, eventually.

I also educate patients about the appearance of the poison ivy plant (see Figure 3). In my part of the country (Oklahoma), where poison ivy is found in virtually every fence line, every creek bank, and every backyard, most people don’t really know what it looks like. Part of that confusion results from the fact that it can take a number of forms, including a vine, often wrapped around trees, a small tree, or even a root, coursing along the ground. Its distinguishing features include the “leaves of three” in typical shapes (darts, with notches, or “thumbs” along the leaf margins), a shiny surface, and white flowers turning into berries.

TAKE-AWAY LEARNING POINTS

• Poison ivy is predominantly found east of the Rocky Mountains and poison oak almost exclusively to the west of them. Poison sumac is limited to the southeastern United States.

• Poison ivy is also known as a form of phytodermatitis, with other botanical sources such as ficus, fig, fern, mango, rhus, and Japanese lacquer trees.

• Poison ivy can grow in the form of a bush, a vine, or even a small tree. However, it also demonstrates the “leaves of three.”

• Linear blisters on an erythematous base is the classic description of a poison ivy reaction, but it can also present in a more diffuse form that concentrates on the popliteal areas and medial thighs.

• Poison ivy is not “poison.” It is the quintessential contact dermatitis, a type IV delayed hypersensitivity reaction to the oil contained in the plant.

• Poison ivy is not contagious and cannot be spread on the patient’s body or to anyone else.

Lifelong Problem Has Caused Embarrassment

ANSWER

The correct answer is discoid lupus (choice “d”); see discussion for further details.

Sarcoidosis (choice “a”) is a worthy item in this differential, since it can be chronic, often affects the face (especially in African-Americans), and frequently defies ready diagnosis. But the biopsy was totally inconsistent with this diagnosis; in a case of sarcoidosis, it instead would have shown noncaseating granulomas, which are characteristic of the condition.

Lichen planus (choice “b”) is likewise worth consideration, since it can present in a similar fashion (although the chronicity of this patient’s lesions would have been atypical). Moreover, lichen planus is almost invariably symptomatic (itch). Biopsy would have shown obliteration of the dermoepidermal junction by an intense lymphocytic infiltrate—findings totally at odds with what was seen.

Polymorphous light eruption (PMLE; choice “c”) is the name given to a variety of photosensitivities that, true to the term polymorphous (or polymorphic), can present in numerous ways—although the lesions on any given patient tend to be monomorphic. These can take the form of vesicles, papules, and even erythema multiforme–like targetoid lesions, most commonly (as expected) on sun-exposed skin. Curiously, though, PMLE seldom affects the face or hands. It can manifest early in a patient’s life, but it would have been “seasonal,” disappearing in winter, and would have revealed a totally different picture on biopsy.

DISCUSSION

This patient suffered needlessly for more than half his life for lack of one simple thing: a correct diagnosis. Truth be known, the patient and his family probably bear some responsibility—but at some point, one of his many providers should have either obtained a punch biopsy or sent him to someone who would do so.

Instead, as is often the case, the emphasis was on treatment: trying one thing after another. The lack of success with these endeavors speaks loudly for the need for a definitive diagnosis. This could only be established one way: with a biopsy.

All the items mentioned in the above differential were legitimately considered. So was the possibility of infection, especially atypical types such as mycobacterial, deep fungal, or those involving other unusual organisms (eg, Nocardia, Actinomycetes). As in this case, tissue can be collected and submitted for culture, but the usual formalin preservative will kill any organism, necessitating prompt processing in saline.

Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) can be purely cutaneous (as seen here) or can be a manifestation of more serious systemic lupus. In any case, it is an autoimmune process, made worse by the sun, and can be chronic (though this case is exceptional in that regard).

This patient’s chance of developing systemic lupus erythematosus is slight, at most, since his antinuclear antibody test was negative. But his lifetime risk for another autoimmune disease is high.

TREATMENT

DLE is usually treated successfully with a combination of sun avoidance and a course of oral hydroxychloroquine (200 mg QD to bid, depending on the patient’s body habitus and the severity of the disease). Given the advanced state of this patient’s condition, he received the more frequent dosage, which should yield positive results. However, he will likely be on this regimen for some time.

ANSWER

The correct answer is discoid lupus (choice “d”); see discussion for further details.

Sarcoidosis (choice “a”) is a worthy item in this differential, since it can be chronic, often affects the face (especially in African-Americans), and frequently defies ready diagnosis. But the biopsy was totally inconsistent with this diagnosis; in a case of sarcoidosis, it instead would have shown noncaseating granulomas, which are characteristic of the condition.

Lichen planus (choice “b”) is likewise worth consideration, since it can present in a similar fashion (although the chronicity of this patient’s lesions would have been atypical). Moreover, lichen planus is almost invariably symptomatic (itch). Biopsy would have shown obliteration of the dermoepidermal junction by an intense lymphocytic infiltrate—findings totally at odds with what was seen.

Polymorphous light eruption (PMLE; choice “c”) is the name given to a variety of photosensitivities that, true to the term polymorphous (or polymorphic), can present in numerous ways—although the lesions on any given patient tend to be monomorphic. These can take the form of vesicles, papules, and even erythema multiforme–like targetoid lesions, most commonly (as expected) on sun-exposed skin. Curiously, though, PMLE seldom affects the face or hands. It can manifest early in a patient’s life, but it would have been “seasonal,” disappearing in winter, and would have revealed a totally different picture on biopsy.

DISCUSSION

This patient suffered needlessly for more than half his life for lack of one simple thing: a correct diagnosis. Truth be known, the patient and his family probably bear some responsibility—but at some point, one of his many providers should have either obtained a punch biopsy or sent him to someone who would do so.

Instead, as is often the case, the emphasis was on treatment: trying one thing after another. The lack of success with these endeavors speaks loudly for the need for a definitive diagnosis. This could only be established one way: with a biopsy.

All the items mentioned in the above differential were legitimately considered. So was the possibility of infection, especially atypical types such as mycobacterial, deep fungal, or those involving other unusual organisms (eg, Nocardia, Actinomycetes). As in this case, tissue can be collected and submitted for culture, but the usual formalin preservative will kill any organism, necessitating prompt processing in saline.

Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) can be purely cutaneous (as seen here) or can be a manifestation of more serious systemic lupus. In any case, it is an autoimmune process, made worse by the sun, and can be chronic (though this case is exceptional in that regard).

This patient’s chance of developing systemic lupus erythematosus is slight, at most, since his antinuclear antibody test was negative. But his lifetime risk for another autoimmune disease is high.

TREATMENT

DLE is usually treated successfully with a combination of sun avoidance and a course of oral hydroxychloroquine (200 mg QD to bid, depending on the patient’s body habitus and the severity of the disease). Given the advanced state of this patient’s condition, he received the more frequent dosage, which should yield positive results. However, he will likely be on this regimen for some time.

ANSWER

The correct answer is discoid lupus (choice “d”); see discussion for further details.

Sarcoidosis (choice “a”) is a worthy item in this differential, since it can be chronic, often affects the face (especially in African-Americans), and frequently defies ready diagnosis. But the biopsy was totally inconsistent with this diagnosis; in a case of sarcoidosis, it instead would have shown noncaseating granulomas, which are characteristic of the condition.

Lichen planus (choice “b”) is likewise worth consideration, since it can present in a similar fashion (although the chronicity of this patient’s lesions would have been atypical). Moreover, lichen planus is almost invariably symptomatic (itch). Biopsy would have shown obliteration of the dermoepidermal junction by an intense lymphocytic infiltrate—findings totally at odds with what was seen.

Polymorphous light eruption (PMLE; choice “c”) is the name given to a variety of photosensitivities that, true to the term polymorphous (or polymorphic), can present in numerous ways—although the lesions on any given patient tend to be monomorphic. These can take the form of vesicles, papules, and even erythema multiforme–like targetoid lesions, most commonly (as expected) on sun-exposed skin. Curiously, though, PMLE seldom affects the face or hands. It can manifest early in a patient’s life, but it would have been “seasonal,” disappearing in winter, and would have revealed a totally different picture on biopsy.

DISCUSSION

This patient suffered needlessly for more than half his life for lack of one simple thing: a correct diagnosis. Truth be known, the patient and his family probably bear some responsibility—but at some point, one of his many providers should have either obtained a punch biopsy or sent him to someone who would do so.

Instead, as is often the case, the emphasis was on treatment: trying one thing after another. The lack of success with these endeavors speaks loudly for the need for a definitive diagnosis. This could only be established one way: with a biopsy.

All the items mentioned in the above differential were legitimately considered. So was the possibility of infection, especially atypical types such as mycobacterial, deep fungal, or those involving other unusual organisms (eg, Nocardia, Actinomycetes). As in this case, tissue can be collected and submitted for culture, but the usual formalin preservative will kill any organism, necessitating prompt processing in saline.

Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) can be purely cutaneous (as seen here) or can be a manifestation of more serious systemic lupus. In any case, it is an autoimmune process, made worse by the sun, and can be chronic (though this case is exceptional in that regard).

This patient’s chance of developing systemic lupus erythematosus is slight, at most, since his antinuclear antibody test was negative. But his lifetime risk for another autoimmune disease is high.

TREATMENT

DLE is usually treated successfully with a combination of sun avoidance and a course of oral hydroxychloroquine (200 mg QD to bid, depending on the patient’s body habitus and the severity of the disease). Given the advanced state of this patient’s condition, he received the more frequent dosage, which should yield positive results. However, he will likely be on this regimen for some time.

Since the fourth grade, this 22-year-old African-American man has had facial lesions that, although constantly present, worsen in the summer. The problem is so severe that it has greatly affected his quality of life: In school and in his neighborhood, he has been subjected to rumors that his condition might be contagious. Despite numerous treatment attempts—including topical and oral anti-acne medications, topical and oral antifungal medications, and oral antibiotics—the condition has persisted. Once, at his mother’s urging, the patient even sought the assistance of a faith healer at a religious revival. Initially seen by a primary care provider at a free clinic, he was then referred to a dermatology clinician at the same facility. History taking reveals that the lesions are asymptomatic and appear in additional locations (eg, arms, ears, and neck). The patient denies any family history of similar problems, as well as persistent fever, cough, or shortness of breath. Lab studies obtained by his primary care provider, including a complete blood count and chem screen, were within normal limits. Most of the lesions on the patient’s face are round areas of slightly erythematous erosion covered by eschar. They range in size from 3 mm to more than 1 cm. Focal postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is noted (a common finding in those with type V/VI skin). Focal hyperpigmentation is also seen on both ears, in some cases with scaling and faint erosion on the surface. A KOH prep is performed with scale collected from perilesional skin; results are negative for fungal elements. There are no palpable nodes in the adjacent nodal locations. Two punch biopsies are done, with samples taken from the active margins of the lesions. One is submitted for routine H&E (hematoxylin and eosin) handling and the other in saline for bacterial, acid-fast bacilli (AFB), and fungal cultures. The biopsy shows hyperkeratosis, follicular plugging, and epidermal atrophy. Marked vacuolar degeneration of the dermoepidermal junction is also noted, along with mucin deposition. Stains for bacteria, AFB, and fungi yield negative results.

An Itch for Which OTC Creams Fail

A 50-year-old man self-refers to dermatology for an acute-onset, very itchy rash on the bottom of his foot. The rash appeared a week ago and is so symptomatic that he is unable to sleep. The patient tried applying OTC hydrocortisone 0.5% cream, but it only seemed to worsen his condition.

The patient denies any other significant health concerns. There is no personal or family history of skin problems; no one else in his household has been affected by this outbreak. He has not traveled internationally or domestically in the recent past. The only thing new in his life is a kitten that was rescued from a local animal shelter and given to his teenage daughter by a friend.

EXAMINATION

The rash, confined to the right instep, is composed of tiny, low vesicles surrounded by peripheral scaling. No overt inflammation is noted, although several of the vesicles (which appear to be drying up) have a slightly inflamed appearance. No rash is observed between the toes or elsewhere on the feet.

Scale is carefully collected (with a #10 blade) from the periphery of the site, as well as the dried roofs of some of the old vesicles. KOH examination shows abundant hyphae.

With his condition thus diagnosed as fungal in origin, the patient is given a written prescription for oxiconazole cream. But when he takes the script to his pharmacy, he discovers his insurance will not cover the cost. With advice from the pharmacist, he buys tolnaftate cream and applies it twice a day.

Despite the use of this product, his symptoms continue unabated throughout the intervening weekend. Very distressed, the patient calls in bright and early on Monday morning to complain. He is able to come in and get samples of the originally prescribed oxiconazole cream, which clears the problem within a week.

DISCUSSION

While “athlete’s foot” is a common problem, neither diagnosis nor treatment is always as simple as one might think. First of all, there are three types of tinea pedis—although interdigital is, by far, the most common. Almost always caused by Trichophyton rubrum, it manifests with a white, macerated look between the fourth and fifth toes (occasionally the third and fourth).

Although heredity may play a significant role in terms of susceptibility, sweat and heat are the major factors in the acquisition of tinea pedis. Persistent sweating (and the wearing of shoes, such as boots, that encourage it) often results in a chronic condition that is unlikely to be “cured.”

Almost any imidazole cream (eg econazole, oxiconazole, or clotrimazole) will at least control it, as will allylamine topical preparations (eg, terbinafine and naftin). Patients should understand that, no matter how earnestly the TV pitchman promotes an antifungal cream as “fast actin’,” nothing will change the fact that tolnaftate is ineffective compared to the medications mentioned above.

The second-most common type is moccasin-variety tinea pedis, which is usually asymptomatic and chronic, presenting with a powdery white fine scale that covers the sides and bottoms of both feet. It rarely needs treatment, in part because it’s asymptomatic but also because most affected patients don’t complain about it. This is a good thing, because a cure is virtually impossible.

This brings us to our case patient, who has the most unusual type of tinea pedis: the inflammatory type, which can be anthropophilic or zoophilic (contracted from man or animal). As this case illustrates, it is usually of acute origin, affects the instep, and is highly symptomatic. Unlike the other types, it manifests with inflammatory vesicles, from which peripheral scaling spreads as the lesions resolve. Abundant hyphae are reliably found in the roofs of resolved vesicles, confirming the diagnosis—although this relatively thick skin may take time to be digested by the alkaline KOH.

Trichophyton mentagrophytes, a common pathogen shed in cat hair, can be difficult to treat. Had this case been more severe, oral terbinafine (250 mg/d for two weeks) might have been added to the oxiconazole to clear the problem. The good news is that this type of tinea pedis tends to be episodic and not chronic. The bad news? If the cat is the culprit (by no means is this certain), the condition may recur.

The differential for this condition includes dyshidrotic eczema, contact dermatitis, and scabies.

TAKE-AWAY LEARNING POINTS

• The least common form of tinea pedis is the inflammatory type, which tends to be of acute onset and highly symptomatic (itchy), typically affects the instep, and presents with vesicles.

• KOH prep must be performed to diagnose this condition; it will reveal large numbers of obvious hyphae. The richest source of sample material is the roof of dried vesicles.

• The hydrocortisone the patient used probably made the fungal infection worse.

• Tolnaftate cream, available OTC, is a relatively ineffective treatment for tinea pedis, compared to the imidazoles and allylamines (no matter what John Madden says).

• Inflammatory tinea pedis is often of zoophilic origin, with cats being a common source.

A 50-year-old man self-refers to dermatology for an acute-onset, very itchy rash on the bottom of his foot. The rash appeared a week ago and is so symptomatic that he is unable to sleep. The patient tried applying OTC hydrocortisone 0.5% cream, but it only seemed to worsen his condition.

The patient denies any other significant health concerns. There is no personal or family history of skin problems; no one else in his household has been affected by this outbreak. He has not traveled internationally or domestically in the recent past. The only thing new in his life is a kitten that was rescued from a local animal shelter and given to his teenage daughter by a friend.

EXAMINATION

The rash, confined to the right instep, is composed of tiny, low vesicles surrounded by peripheral scaling. No overt inflammation is noted, although several of the vesicles (which appear to be drying up) have a slightly inflamed appearance. No rash is observed between the toes or elsewhere on the feet.

Scale is carefully collected (with a #10 blade) from the periphery of the site, as well as the dried roofs of some of the old vesicles. KOH examination shows abundant hyphae.

With his condition thus diagnosed as fungal in origin, the patient is given a written prescription for oxiconazole cream. But when he takes the script to his pharmacy, he discovers his insurance will not cover the cost. With advice from the pharmacist, he buys tolnaftate cream and applies it twice a day.

Despite the use of this product, his symptoms continue unabated throughout the intervening weekend. Very distressed, the patient calls in bright and early on Monday morning to complain. He is able to come in and get samples of the originally prescribed oxiconazole cream, which clears the problem within a week.

DISCUSSION

While “athlete’s foot” is a common problem, neither diagnosis nor treatment is always as simple as one might think. First of all, there are three types of tinea pedis—although interdigital is, by far, the most common. Almost always caused by Trichophyton rubrum, it manifests with a white, macerated look between the fourth and fifth toes (occasionally the third and fourth).

Although heredity may play a significant role in terms of susceptibility, sweat and heat are the major factors in the acquisition of tinea pedis. Persistent sweating (and the wearing of shoes, such as boots, that encourage it) often results in a chronic condition that is unlikely to be “cured.”

Almost any imidazole cream (eg econazole, oxiconazole, or clotrimazole) will at least control it, as will allylamine topical preparations (eg, terbinafine and naftin). Patients should understand that, no matter how earnestly the TV pitchman promotes an antifungal cream as “fast actin’,” nothing will change the fact that tolnaftate is ineffective compared to the medications mentioned above.

The second-most common type is moccasin-variety tinea pedis, which is usually asymptomatic and chronic, presenting with a powdery white fine scale that covers the sides and bottoms of both feet. It rarely needs treatment, in part because it’s asymptomatic but also because most affected patients don’t complain about it. This is a good thing, because a cure is virtually impossible.

This brings us to our case patient, who has the most unusual type of tinea pedis: the inflammatory type, which can be anthropophilic or zoophilic (contracted from man or animal). As this case illustrates, it is usually of acute origin, affects the instep, and is highly symptomatic. Unlike the other types, it manifests with inflammatory vesicles, from which peripheral scaling spreads as the lesions resolve. Abundant hyphae are reliably found in the roofs of resolved vesicles, confirming the diagnosis—although this relatively thick skin may take time to be digested by the alkaline KOH.

Trichophyton mentagrophytes, a common pathogen shed in cat hair, can be difficult to treat. Had this case been more severe, oral terbinafine (250 mg/d for two weeks) might have been added to the oxiconazole to clear the problem. The good news is that this type of tinea pedis tends to be episodic and not chronic. The bad news? If the cat is the culprit (by no means is this certain), the condition may recur.

The differential for this condition includes dyshidrotic eczema, contact dermatitis, and scabies.

TAKE-AWAY LEARNING POINTS

• The least common form of tinea pedis is the inflammatory type, which tends to be of acute onset and highly symptomatic (itchy), typically affects the instep, and presents with vesicles.

• KOH prep must be performed to diagnose this condition; it will reveal large numbers of obvious hyphae. The richest source of sample material is the roof of dried vesicles.

• The hydrocortisone the patient used probably made the fungal infection worse.

• Tolnaftate cream, available OTC, is a relatively ineffective treatment for tinea pedis, compared to the imidazoles and allylamines (no matter what John Madden says).

• Inflammatory tinea pedis is often of zoophilic origin, with cats being a common source.

A 50-year-old man self-refers to dermatology for an acute-onset, very itchy rash on the bottom of his foot. The rash appeared a week ago and is so symptomatic that he is unable to sleep. The patient tried applying OTC hydrocortisone 0.5% cream, but it only seemed to worsen his condition.

The patient denies any other significant health concerns. There is no personal or family history of skin problems; no one else in his household has been affected by this outbreak. He has not traveled internationally or domestically in the recent past. The only thing new in his life is a kitten that was rescued from a local animal shelter and given to his teenage daughter by a friend.

EXAMINATION

The rash, confined to the right instep, is composed of tiny, low vesicles surrounded by peripheral scaling. No overt inflammation is noted, although several of the vesicles (which appear to be drying up) have a slightly inflamed appearance. No rash is observed between the toes or elsewhere on the feet.

Scale is carefully collected (with a #10 blade) from the periphery of the site, as well as the dried roofs of some of the old vesicles. KOH examination shows abundant hyphae.

With his condition thus diagnosed as fungal in origin, the patient is given a written prescription for oxiconazole cream. But when he takes the script to his pharmacy, he discovers his insurance will not cover the cost. With advice from the pharmacist, he buys tolnaftate cream and applies it twice a day.

Despite the use of this product, his symptoms continue unabated throughout the intervening weekend. Very distressed, the patient calls in bright and early on Monday morning to complain. He is able to come in and get samples of the originally prescribed oxiconazole cream, which clears the problem within a week.

DISCUSSION

While “athlete’s foot” is a common problem, neither diagnosis nor treatment is always as simple as one might think. First of all, there are three types of tinea pedis—although interdigital is, by far, the most common. Almost always caused by Trichophyton rubrum, it manifests with a white, macerated look between the fourth and fifth toes (occasionally the third and fourth).

Although heredity may play a significant role in terms of susceptibility, sweat and heat are the major factors in the acquisition of tinea pedis. Persistent sweating (and the wearing of shoes, such as boots, that encourage it) often results in a chronic condition that is unlikely to be “cured.”

Almost any imidazole cream (eg econazole, oxiconazole, or clotrimazole) will at least control it, as will allylamine topical preparations (eg, terbinafine and naftin). Patients should understand that, no matter how earnestly the TV pitchman promotes an antifungal cream as “fast actin’,” nothing will change the fact that tolnaftate is ineffective compared to the medications mentioned above.

The second-most common type is moccasin-variety tinea pedis, which is usually asymptomatic and chronic, presenting with a powdery white fine scale that covers the sides and bottoms of both feet. It rarely needs treatment, in part because it’s asymptomatic but also because most affected patients don’t complain about it. This is a good thing, because a cure is virtually impossible.

This brings us to our case patient, who has the most unusual type of tinea pedis: the inflammatory type, which can be anthropophilic or zoophilic (contracted from man or animal). As this case illustrates, it is usually of acute origin, affects the instep, and is highly symptomatic. Unlike the other types, it manifests with inflammatory vesicles, from which peripheral scaling spreads as the lesions resolve. Abundant hyphae are reliably found in the roofs of resolved vesicles, confirming the diagnosis—although this relatively thick skin may take time to be digested by the alkaline KOH.

Trichophyton mentagrophytes, a common pathogen shed in cat hair, can be difficult to treat. Had this case been more severe, oral terbinafine (250 mg/d for two weeks) might have been added to the oxiconazole to clear the problem. The good news is that this type of tinea pedis tends to be episodic and not chronic. The bad news? If the cat is the culprit (by no means is this certain), the condition may recur.

The differential for this condition includes dyshidrotic eczema, contact dermatitis, and scabies.

TAKE-AWAY LEARNING POINTS

• The least common form of tinea pedis is the inflammatory type, which tends to be of acute onset and highly symptomatic (itchy), typically affects the instep, and presents with vesicles.

• KOH prep must be performed to diagnose this condition; it will reveal large numbers of obvious hyphae. The richest source of sample material is the roof of dried vesicles.

• The hydrocortisone the patient used probably made the fungal infection worse.

• Tolnaftate cream, available OTC, is a relatively ineffective treatment for tinea pedis, compared to the imidazoles and allylamines (no matter what John Madden says).

• Inflammatory tinea pedis is often of zoophilic origin, with cats being a common source.

Unusual Cause for Asymptomatic Rash

A 52-year-old man is referred to dermatology by his primary care provider for evaluation of an extensive rash. When it first appeared a month ago, the rash was confined to his abdomen. It has subsequently spread—slowly but steadily—to most of his body.

Although it is asymptomatic, the rash is nonetheless of considerable concern to the patient. He denies any history of atopy and has not experienced fever or malaise during the rash’s manifestation. A number of OTC products, including calamine lotion and hydrocortisone 1% cream, have been tried without success.

During history taking, the patient indicates that he is HIV-positive. He was diagnosed more than 10 years ago, and he reports that his disease is well controlled with medication. Homosexually active, he denies having any new contacts.

EXAMINATION

The patient is in no acute distress, although his complexion appears somewhat sallow. The rash is composed of blanchable, erythematous papules and nodules averaging a centimeter in diameter. It is fairly dense, uniformly covering most of his skin but sparing his face and soles. Two 7-mm scaly brown nodules are seen on his right palm. There are no palpable nodes in the usual locations.

Records from his primary care provider are examined. These confirm the patient’s report of his HIV-positive status.

A 4-mm punch biopsy is performed on one of his truncal lesions, with the sample submitted for routine handling.

HISTOPATHOLOGY

Superficial bandlike perivascular infiltrates composed of lymphocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells are noted, along with psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis. Stains for spirochetes are negative.

DISCUSSION

The differential for generalized red rashes is prodigious and includes granuloma annulare, lichen planus, lupus, and pityriasis rosea, just to name a few. However, this case presents a fairly typical clinical picture of secondary syphilis—a diagnosis that requires confirmation with syphilis serology: rapid plasma reagin (RPR) or Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) testing. The latter measures antibodies to the lipids formed by the host against lipids formed on the treponemal cell surface.

In this case, the diagnosis had to be confirmed by more specific treponemal tests, usually conducted by the local health department, to which positive results must be reported. If further testing confirms the diagnosis (as expected), the patient will be treated by the health department. Investigators will question him, attempting to determine the source of the infection and thereby quell an outbreak.

Primary syphilis usually involves development of the characteristic asymptomatic ulcer with rolled edges, called a chancre, on the genitals, lips, or other area. This lesion is often overlooked or (as is often the case) no history of it can be obtained. Four to 10 weeks later, if left untreated, secondary syphilis develops, manifesting with the variable appearance of lesions on the palms and soles, generalized lymphadenopathy, patchy alopecia (termed a “moth-eaten” look), and generalized rash.

Left undiagnosed and treated, secondary syphilis can progress, over several years, to tertiary syphilis, which can manifest in a number of ways (eg, involvement of the heart or nervous system). It may play a role in the formation of “gummatous” lesions, foci of necrotic tissue that can develop in internal organs or in the mouth, where “punched out” defects can manifest.

The causative organism of syphilis is Treponema pallidum, a spirochete usually transmitted directly from the infected individual through breaks in genital or oral tissues. Though it is usually sexually transmitted, syphilis can be acquired congenitally, through direct contact with open lesions, or through exposure to blood products. Since T pallidum only lives for a very short time away from the body, acquiring it from exposure to fomites (eg, toilet seats or door knobs) is virtually impossible.

Huge spikes in rates of this infection occur periodically in the United States. For example, approximately one-tenth of all military draftees in WW1 tested positive for syphilis, a figure that so alarmed public health officials that it lead to the origins of the monitoring of syphilis by governmental agencies. Another spike was noted during WW2, reaching a rate of 66 cases per 100,000 population in 1947. But with the end of warfare and the introduction of penicillin, the rate fell rapidly and today stands at about 4 cases per 100,000 population, 80% of which occur in the South.

There is a high correlation between a history of men having sex with men (MSM) and infection with syphilis, with 64% of new cases currently coming from those ranks. As might be expected, the correlation between syphilis and HIV-positive status is high. The male to female ratio is approximately 6:1.

TREATMENT

Although this man’s treatment is pending as of this writing, he is likely to receive a single dose of benzathine penicillin G (2.4 million units given IM). Penicillin is so much more effective than alternative treatments that it is strongly recommended even when the patient is allergic to it. (In those cases, desensitization is advised if the allergy is confirmed.) Other treatment options include ceftriaxone and doxycycline.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Secondary syphilis can present with a generalized rash, the appearance of which can vary greatly from one case to another.

• Persistent, unexplained generalized rashes require biopsy to attempt to explain their origin.

• The presence of plasma cells predominating in the inflammatory infiltrate of a rash is highly suggestive of secondary syphilis.

• Indiscriminate and unprotected sex, particularly among men who have sex with men, correlates with risk for a number of conditions, including syphilis and HIV; this information must be sought in the history-taking process.

• Secondary syphilis must be reported to the local health department for investigation and definitive treatment.

A 52-year-old man is referred to dermatology by his primary care provider for evaluation of an extensive rash. When it first appeared a month ago, the rash was confined to his abdomen. It has subsequently spread—slowly but steadily—to most of his body.

Although it is asymptomatic, the rash is nonetheless of considerable concern to the patient. He denies any history of atopy and has not experienced fever or malaise during the rash’s manifestation. A number of OTC products, including calamine lotion and hydrocortisone 1% cream, have been tried without success.

During history taking, the patient indicates that he is HIV-positive. He was diagnosed more than 10 years ago, and he reports that his disease is well controlled with medication. Homosexually active, he denies having any new contacts.

EXAMINATION

The patient is in no acute distress, although his complexion appears somewhat sallow. The rash is composed of blanchable, erythematous papules and nodules averaging a centimeter in diameter. It is fairly dense, uniformly covering most of his skin but sparing his face and soles. Two 7-mm scaly brown nodules are seen on his right palm. There are no palpable nodes in the usual locations.

Records from his primary care provider are examined. These confirm the patient’s report of his HIV-positive status.

A 4-mm punch biopsy is performed on one of his truncal lesions, with the sample submitted for routine handling.

HISTOPATHOLOGY

Superficial bandlike perivascular infiltrates composed of lymphocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells are noted, along with psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis. Stains for spirochetes are negative.

DISCUSSION

The differential for generalized red rashes is prodigious and includes granuloma annulare, lichen planus, lupus, and pityriasis rosea, just to name a few. However, this case presents a fairly typical clinical picture of secondary syphilis—a diagnosis that requires confirmation with syphilis serology: rapid plasma reagin (RPR) or Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) testing. The latter measures antibodies to the lipids formed by the host against lipids formed on the treponemal cell surface.

In this case, the diagnosis had to be confirmed by more specific treponemal tests, usually conducted by the local health department, to which positive results must be reported. If further testing confirms the diagnosis (as expected), the patient will be treated by the health department. Investigators will question him, attempting to determine the source of the infection and thereby quell an outbreak.

Primary syphilis usually involves development of the characteristic asymptomatic ulcer with rolled edges, called a chancre, on the genitals, lips, or other area. This lesion is often overlooked or (as is often the case) no history of it can be obtained. Four to 10 weeks later, if left untreated, secondary syphilis develops, manifesting with the variable appearance of lesions on the palms and soles, generalized lymphadenopathy, patchy alopecia (termed a “moth-eaten” look), and generalized rash.

Left undiagnosed and treated, secondary syphilis can progress, over several years, to tertiary syphilis, which can manifest in a number of ways (eg, involvement of the heart or nervous system). It may play a role in the formation of “gummatous” lesions, foci of necrotic tissue that can develop in internal organs or in the mouth, where “punched out” defects can manifest.