User login

Thumb: Scaling with Pitted Nail Plate

ANSWER

The most likely diagnosis is psoriasis (choice “d”), which can manifest with localized involvement (see discussion below).

Fungal infection (choice “a”) is unlikely, given the negative results of the KOH prep and total lack of response to treatment for that diagnosis.

Eczema (choice “b”) does not manifest as such thick, adherent scale. If any nail changes were involved, they would likely consist of transverse nail ridges.

A variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC; choice “c”)—caused by human papillomavirus (HPV), for example—can produce somewhat similar changes in the skin. But it would be unlikely to lead to nail changes, and it would not be intermittent, as this rash was in apparent response to OTC cream.

DISCUSSION

A punch biopsy is sometimes required to confirm the diagnosis of psoriasis, but this combination of skin and nail changes is quite suggestive of that entity. In this case, the confirmation was made by a different route: The rheumatologist judged that the patient’s arthritis was psoriatic in nature. The arthritis was treated with methotrexate, which soon cleared the skin disease without any help from dermatology.

This case serves to reinforce the possible mind-body role of stress in the genesis of this disease; however, at least 30% of the time, there is a positive family history. It also demonstrates the seemingly contradictory fact that the severity of the psoriasis doesn’t always correlate with the presence or absence of psoriatic arthritis.

Adding to the difficulty of making the diagnosis of psoriasis is the localized distribution of the scales, since it can usually be corroborated by finding lesions in their usual haunts—such as the extensor surfaces of arms, legs, on the trunk, or in the scalp. Cases such as this one force the provider to carefully consider the differential, which includes fungal infection. But the dermatophytes that cause ordinary fungal infections have to come from predictable sources (eg, children, pets, or farm animals), all missing from this patient’s history.

Had the rash been “fixed” (unchanging), the diagnosis of SCC would have to be considered more carefully. Superficial SCC is called Bowen’s disease, which, in cases such as this, is usually caused by HPV, not by the more typical overexposure to UV light. Though superficial, Bowen’s disease can become focally invasive and can even metastasize.

Had this patient not been treated with methotrexate, we would probably have used topical class 1 corticosteroid creams, which would have had a good chance to improve his skin but not his nail. The patient was also counseled regarding the role of stress and increased alcohol intake in the worsening of his disease. His prognosis for skin and joint disease is decent, though he will probably experience recurrences.

ANSWER

The most likely diagnosis is psoriasis (choice “d”), which can manifest with localized involvement (see discussion below).

Fungal infection (choice “a”) is unlikely, given the negative results of the KOH prep and total lack of response to treatment for that diagnosis.

Eczema (choice “b”) does not manifest as such thick, adherent scale. If any nail changes were involved, they would likely consist of transverse nail ridges.

A variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC; choice “c”)—caused by human papillomavirus (HPV), for example—can produce somewhat similar changes in the skin. But it would be unlikely to lead to nail changes, and it would not be intermittent, as this rash was in apparent response to OTC cream.

DISCUSSION

A punch biopsy is sometimes required to confirm the diagnosis of psoriasis, but this combination of skin and nail changes is quite suggestive of that entity. In this case, the confirmation was made by a different route: The rheumatologist judged that the patient’s arthritis was psoriatic in nature. The arthritis was treated with methotrexate, which soon cleared the skin disease without any help from dermatology.

This case serves to reinforce the possible mind-body role of stress in the genesis of this disease; however, at least 30% of the time, there is a positive family history. It also demonstrates the seemingly contradictory fact that the severity of the psoriasis doesn’t always correlate with the presence or absence of psoriatic arthritis.

Adding to the difficulty of making the diagnosis of psoriasis is the localized distribution of the scales, since it can usually be corroborated by finding lesions in their usual haunts—such as the extensor surfaces of arms, legs, on the trunk, or in the scalp. Cases such as this one force the provider to carefully consider the differential, which includes fungal infection. But the dermatophytes that cause ordinary fungal infections have to come from predictable sources (eg, children, pets, or farm animals), all missing from this patient’s history.

Had the rash been “fixed” (unchanging), the diagnosis of SCC would have to be considered more carefully. Superficial SCC is called Bowen’s disease, which, in cases such as this, is usually caused by HPV, not by the more typical overexposure to UV light. Though superficial, Bowen’s disease can become focally invasive and can even metastasize.

Had this patient not been treated with methotrexate, we would probably have used topical class 1 corticosteroid creams, which would have had a good chance to improve his skin but not his nail. The patient was also counseled regarding the role of stress and increased alcohol intake in the worsening of his disease. His prognosis for skin and joint disease is decent, though he will probably experience recurrences.

ANSWER

The most likely diagnosis is psoriasis (choice “d”), which can manifest with localized involvement (see discussion below).

Fungal infection (choice “a”) is unlikely, given the negative results of the KOH prep and total lack of response to treatment for that diagnosis.

Eczema (choice “b”) does not manifest as such thick, adherent scale. If any nail changes were involved, they would likely consist of transverse nail ridges.

A variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC; choice “c”)—caused by human papillomavirus (HPV), for example—can produce somewhat similar changes in the skin. But it would be unlikely to lead to nail changes, and it would not be intermittent, as this rash was in apparent response to OTC cream.

DISCUSSION

A punch biopsy is sometimes required to confirm the diagnosis of psoriasis, but this combination of skin and nail changes is quite suggestive of that entity. In this case, the confirmation was made by a different route: The rheumatologist judged that the patient’s arthritis was psoriatic in nature. The arthritis was treated with methotrexate, which soon cleared the skin disease without any help from dermatology.

This case serves to reinforce the possible mind-body role of stress in the genesis of this disease; however, at least 30% of the time, there is a positive family history. It also demonstrates the seemingly contradictory fact that the severity of the psoriasis doesn’t always correlate with the presence or absence of psoriatic arthritis.

Adding to the difficulty of making the diagnosis of psoriasis is the localized distribution of the scales, since it can usually be corroborated by finding lesions in their usual haunts—such as the extensor surfaces of arms, legs, on the trunk, or in the scalp. Cases such as this one force the provider to carefully consider the differential, which includes fungal infection. But the dermatophytes that cause ordinary fungal infections have to come from predictable sources (eg, children, pets, or farm animals), all missing from this patient’s history.

Had the rash been “fixed” (unchanging), the diagnosis of SCC would have to be considered more carefully. Superficial SCC is called Bowen’s disease, which, in cases such as this, is usually caused by HPV, not by the more typical overexposure to UV light. Though superficial, Bowen’s disease can become focally invasive and can even metastasize.

Had this patient not been treated with methotrexate, we would probably have used topical class 1 corticosteroid creams, which would have had a good chance to improve his skin but not his nail. The patient was also counseled regarding the role of stress and increased alcohol intake in the worsening of his disease. His prognosis for skin and joint disease is decent, though he will probably experience recurrences.

About a year ago, this 40-year-old man developed scaling on the distal one-third of his thumbnail. After an ini-tial apparent response to OTC hydrocortisone 1% cream, the condition began to worsen, spreading to more of the thumb. The patient’s primary care provider diagnosed fungal infection and prescribed a combination clotrima-zole/betamethasone cream, which had no effect. A subsequent four-month course of terbinafine (250 mg/d) also yielded no improvement. The patient then requested referral to dermatology. The patient considers himself “quite healthy,” aside from having moderately severe arthritis, for which he takes nabumetone (750 mg bid). His arthritis recently worsened, and he is scheduled to see a rheumatologist in two months. He admits to being under a great deal of stress shortly before his skin condition developed. As a result, he in-creased his alcohol intake for a few months, but he quit drinking altogether soon afterward. He denies any family history of skin disease and has no children or contact with animals. On examination, most of his thumb is covered by thick adherent white scales on a pinkish base. The margins are sharply defined. A KOH prep is performed, but no fungal elements are seen. The adjacent thumbnail has focal areas of pitting in the nail plate, as well as yellowish discoloration on the dis-tal edge. No such changes are seen on his other nails, and examination of his elbows, knees, trunk, and scalp fails to reveal any significant abnormalities.

Hair loss comes and goes, always causing distress

HISTORY

This 38-year-old man has had recurrent episodes of focal hair loss. His scalp has been the most affected area, but he has also noticed hair loss in his beard and in the suprapubic area. Although the problem resolves in weeks to months, it is very distressing for him.

Early in each episode, he experiences a slight tingling in the area, followed by noticeable hair loss—usually in a round pattern. He has consulted a number of providers, but no one in dermatology (until now, that is).

Additional history taking reveals a strong connection between stress and these episodes of hair loss. Moreover, there is a family history of similar hair loss, as well as of thyroid disease.

EXAMINATION

Several areas of complete hair loss, in annular configuration, are noted in the patient's scalp. No epidermal changes (eg, scaling, redness, edema) are present. Two of the sites are slightly larger than 5 cm in diameter.

DISCUSSION

Hair loss (alopecia) is an exceedingly common complaint, but alopecia areata (AA) is one of the more prolific types. Stress appears to trigger the episodes. Ironically, many patients find the hair loss itself to be extremely stressful, which of course compounds the problem.

The most widely accepted theory is that AA is an autoimmune phenomenon, mediated by T-cells and occurring in genetically predisposed individuals. Support for this theory is abundant: increased levels of antibodies directed to various hair follicle structures and a perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate seen histologically.

Likewise, the genetic basis for predisposition to AA appears valid. For example, 10% to 20% of AA patients report a positive family history. (The more severe the AA, the more likely the patient is to have that family history.) When one twin has AA, the other is quite likely to develop it during his/her lifetime. The high association of Down's syndrome with AA suggests the involvement of a gene located on chromosome 21, but other genes have also been implicated.

PROGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

In the majority of cases, AA resolves, with or without treatment, within weeks to months. As this particular case illustrates, recurrences are quite common. In a study of more than 700 patients, 90% experienced a recurrence of AA within five years.

A tiny percentage of AA patients will progress to the permanent loss of all scalp hair (termed alopecia totalis), and a small percentage of those patients will go on to lose every hair on their body (alopecia universalis). In addition to a family history of such problems, other factors that predict this outcome include youth, atopy, and the extent of involvement of the peripheral scalp (ophiasis).

Local intralesional steroid injection (triamcinolone 5 mg/cc) usually stimulates modest hair regrowth, but must be continued at regular intervals for maintenance. Many other systemic and topically applied medications have been tried, but none appear to have a curative effect.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Aside from androgenetic alopecia (the so-called male pattern baldness seen in both men and women), the next most common type of hair loss is telogen effluvium. Seen almost exclusively in women, TE involves uniform hair loss from all over the scalp; the lost hair can be found in the comb, brush, or sink.

Occasionally, AA can be so atypical as to require biopsy to distinguish it from another major item in the differential: trichotillomania. The latter condition is characterized by focal hair loss caused by obsessive twirling or other digital manipulation by the patient, who often has an obsessive-compulsive disorder. This process usually leaves hairs of unequal lengths in the affected location (whereas in AA, total hair loss is typical).

The process of evaluating patients for hair loss is often complicated by the presence of more than one diagnosis. For example, it's quite common for a woman to have longstanding, mild androgenetic alopecia, with thinning mostly confined to the crown of the scalp, but then to experience the onset of AA or TE superimposed on the chronic hair loss. This can make for a confusing clinical picture.

The potential for hair loss due to other conditions—such as connective tissue diseases (lupus is a prime example), secondary syphilis, thyroid disease, or any number of inflammatory conditions, including lichen planopilaris—further complicates the process. And as if all this were not enough, alopecia patients are usually, and understandably, anxious about their problem. Prompt referral of these patients to dermatology is often advisable.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Localized, complete hair loss in a well-defined annular pattern is probably alopecia areata (AA).

• One of the more common types of hair loss, AA is polygenic in origin, with an autoimmune basis, and manifests in a genetically predisposed patient.

• No treatment has been shown to influence the long-term outcome of AA, which is usually self-limiting.

• Recurrences of AA are quite common; stress appears to be the triggering factor in many cases.

• The fact that AA is common in patients with Down's syndrome suggests the possible involvement of a gene located on chromosome 21.

• Alopecia patients are often quite anxious and therefore may benefit from referral to dermatology for evaluation of what can be a complex problem.

HISTORY

This 38-year-old man has had recurrent episodes of focal hair loss. His scalp has been the most affected area, but he has also noticed hair loss in his beard and in the suprapubic area. Although the problem resolves in weeks to months, it is very distressing for him.

Early in each episode, he experiences a slight tingling in the area, followed by noticeable hair loss—usually in a round pattern. He has consulted a number of providers, but no one in dermatology (until now, that is).

Additional history taking reveals a strong connection between stress and these episodes of hair loss. Moreover, there is a family history of similar hair loss, as well as of thyroid disease.

EXAMINATION

Several areas of complete hair loss, in annular configuration, are noted in the patient's scalp. No epidermal changes (eg, scaling, redness, edema) are present. Two of the sites are slightly larger than 5 cm in diameter.

DISCUSSION

Hair loss (alopecia) is an exceedingly common complaint, but alopecia areata (AA) is one of the more prolific types. Stress appears to trigger the episodes. Ironically, many patients find the hair loss itself to be extremely stressful, which of course compounds the problem.

The most widely accepted theory is that AA is an autoimmune phenomenon, mediated by T-cells and occurring in genetically predisposed individuals. Support for this theory is abundant: increased levels of antibodies directed to various hair follicle structures and a perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate seen histologically.

Likewise, the genetic basis for predisposition to AA appears valid. For example, 10% to 20% of AA patients report a positive family history. (The more severe the AA, the more likely the patient is to have that family history.) When one twin has AA, the other is quite likely to develop it during his/her lifetime. The high association of Down's syndrome with AA suggests the involvement of a gene located on chromosome 21, but other genes have also been implicated.

PROGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

In the majority of cases, AA resolves, with or without treatment, within weeks to months. As this particular case illustrates, recurrences are quite common. In a study of more than 700 patients, 90% experienced a recurrence of AA within five years.

A tiny percentage of AA patients will progress to the permanent loss of all scalp hair (termed alopecia totalis), and a small percentage of those patients will go on to lose every hair on their body (alopecia universalis). In addition to a family history of such problems, other factors that predict this outcome include youth, atopy, and the extent of involvement of the peripheral scalp (ophiasis).

Local intralesional steroid injection (triamcinolone 5 mg/cc) usually stimulates modest hair regrowth, but must be continued at regular intervals for maintenance. Many other systemic and topically applied medications have been tried, but none appear to have a curative effect.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Aside from androgenetic alopecia (the so-called male pattern baldness seen in both men and women), the next most common type of hair loss is telogen effluvium. Seen almost exclusively in women, TE involves uniform hair loss from all over the scalp; the lost hair can be found in the comb, brush, or sink.

Occasionally, AA can be so atypical as to require biopsy to distinguish it from another major item in the differential: trichotillomania. The latter condition is characterized by focal hair loss caused by obsessive twirling or other digital manipulation by the patient, who often has an obsessive-compulsive disorder. This process usually leaves hairs of unequal lengths in the affected location (whereas in AA, total hair loss is typical).

The process of evaluating patients for hair loss is often complicated by the presence of more than one diagnosis. For example, it's quite common for a woman to have longstanding, mild androgenetic alopecia, with thinning mostly confined to the crown of the scalp, but then to experience the onset of AA or TE superimposed on the chronic hair loss. This can make for a confusing clinical picture.

The potential for hair loss due to other conditions—such as connective tissue diseases (lupus is a prime example), secondary syphilis, thyroid disease, or any number of inflammatory conditions, including lichen planopilaris—further complicates the process. And as if all this were not enough, alopecia patients are usually, and understandably, anxious about their problem. Prompt referral of these patients to dermatology is often advisable.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Localized, complete hair loss in a well-defined annular pattern is probably alopecia areata (AA).

• One of the more common types of hair loss, AA is polygenic in origin, with an autoimmune basis, and manifests in a genetically predisposed patient.

• No treatment has been shown to influence the long-term outcome of AA, which is usually self-limiting.

• Recurrences of AA are quite common; stress appears to be the triggering factor in many cases.

• The fact that AA is common in patients with Down's syndrome suggests the possible involvement of a gene located on chromosome 21.

• Alopecia patients are often quite anxious and therefore may benefit from referral to dermatology for evaluation of what can be a complex problem.

HISTORY

This 38-year-old man has had recurrent episodes of focal hair loss. His scalp has been the most affected area, but he has also noticed hair loss in his beard and in the suprapubic area. Although the problem resolves in weeks to months, it is very distressing for him.

Early in each episode, he experiences a slight tingling in the area, followed by noticeable hair loss—usually in a round pattern. He has consulted a number of providers, but no one in dermatology (until now, that is).

Additional history taking reveals a strong connection between stress and these episodes of hair loss. Moreover, there is a family history of similar hair loss, as well as of thyroid disease.

EXAMINATION

Several areas of complete hair loss, in annular configuration, are noted in the patient's scalp. No epidermal changes (eg, scaling, redness, edema) are present. Two of the sites are slightly larger than 5 cm in diameter.

DISCUSSION

Hair loss (alopecia) is an exceedingly common complaint, but alopecia areata (AA) is one of the more prolific types. Stress appears to trigger the episodes. Ironically, many patients find the hair loss itself to be extremely stressful, which of course compounds the problem.

The most widely accepted theory is that AA is an autoimmune phenomenon, mediated by T-cells and occurring in genetically predisposed individuals. Support for this theory is abundant: increased levels of antibodies directed to various hair follicle structures and a perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate seen histologically.

Likewise, the genetic basis for predisposition to AA appears valid. For example, 10% to 20% of AA patients report a positive family history. (The more severe the AA, the more likely the patient is to have that family history.) When one twin has AA, the other is quite likely to develop it during his/her lifetime. The high association of Down's syndrome with AA suggests the involvement of a gene located on chromosome 21, but other genes have also been implicated.

PROGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

In the majority of cases, AA resolves, with or without treatment, within weeks to months. As this particular case illustrates, recurrences are quite common. In a study of more than 700 patients, 90% experienced a recurrence of AA within five years.

A tiny percentage of AA patients will progress to the permanent loss of all scalp hair (termed alopecia totalis), and a small percentage of those patients will go on to lose every hair on their body (alopecia universalis). In addition to a family history of such problems, other factors that predict this outcome include youth, atopy, and the extent of involvement of the peripheral scalp (ophiasis).

Local intralesional steroid injection (triamcinolone 5 mg/cc) usually stimulates modest hair regrowth, but must be continued at regular intervals for maintenance. Many other systemic and topically applied medications have been tried, but none appear to have a curative effect.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Aside from androgenetic alopecia (the so-called male pattern baldness seen in both men and women), the next most common type of hair loss is telogen effluvium. Seen almost exclusively in women, TE involves uniform hair loss from all over the scalp; the lost hair can be found in the comb, brush, or sink.

Occasionally, AA can be so atypical as to require biopsy to distinguish it from another major item in the differential: trichotillomania. The latter condition is characterized by focal hair loss caused by obsessive twirling or other digital manipulation by the patient, who often has an obsessive-compulsive disorder. This process usually leaves hairs of unequal lengths in the affected location (whereas in AA, total hair loss is typical).

The process of evaluating patients for hair loss is often complicated by the presence of more than one diagnosis. For example, it's quite common for a woman to have longstanding, mild androgenetic alopecia, with thinning mostly confined to the crown of the scalp, but then to experience the onset of AA or TE superimposed on the chronic hair loss. This can make for a confusing clinical picture.

The potential for hair loss due to other conditions—such as connective tissue diseases (lupus is a prime example), secondary syphilis, thyroid disease, or any number of inflammatory conditions, including lichen planopilaris—further complicates the process. And as if all this were not enough, alopecia patients are usually, and understandably, anxious about their problem. Prompt referral of these patients to dermatology is often advisable.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Localized, complete hair loss in a well-defined annular pattern is probably alopecia areata (AA).

• One of the more common types of hair loss, AA is polygenic in origin, with an autoimmune basis, and manifests in a genetically predisposed patient.

• No treatment has been shown to influence the long-term outcome of AA, which is usually self-limiting.

• Recurrences of AA are quite common; stress appears to be the triggering factor in many cases.

• The fact that AA is common in patients with Down's syndrome suggests the possible involvement of a gene located on chromosome 21.

• Alopecia patients are often quite anxious and therefore may benefit from referral to dermatology for evaluation of what can be a complex problem.

Giving providers a (diagnostic) hand with rash

HISTORY

Rashes of the hand are commonly seen in both primary care and dermatology practices. Their location makes them problematic, in terms of interference with normal activities and difficulty with treatment.

This 51-year-old man’s rash appeared about a month ago, with no premonitory signs. He has consulted numerous providers about it, including his primary care clinician. That practitioner diagnosed a probable “fungal infection” and prescribed a combination clotrimazole/betamethasone dipropionate cream. The rash subsequently improved, though not substantially.

The patient recalls developing a similar rash several other times during adulthood, but says it was never this severe. His mother has had similar eruptions, as well as sensitive skin in general. Both the patient and his mother are plagued by seasonal allergies, asthma, and sweating of the palms.

EXAMINATION

The distal portions of the second through fourth fingers of the right hand are affected. This is typical, according to the patient. The cuticles of all four affected nails are detached from the nail plates, with two of the three nail plates showing mild transverse ridging.

There is circumferential involvement of the distal half of all four fingers, with a well-defined margin and a blistery look to the papulosquamous process. Neither the left hand nor the feet are impacted.

DISCUSSION

This is a classic picture of a condition that goes by several names, most commonly pompholyx, also known as dishidrotic eczema. Despite the efforts of many investigators, with much information gleaned, it remains quite mysterious. It can be chronic or acute and can closely resemble what is known simply as hand dermatitis.

Pompholyx is associated with atopy in at least 50% of cases (such as this one). Hyperhidrosis of the palms is also common, and resolution of difficult cases has been achieved with injection of botulinum toxin A. This hypothesis is bolstered by the fact that many patients report onset in summer months; however, there are many whose history fails to follow this pattern.

Research has revealed that more than a few patients with pompholyx are allergic to one of several ingested metals, such as nickel and cobalt. But challenge tests with those substances have failed to consistently replicate the eruption.

Stress is another reported factor in the genesis of this condition. It is well known to exacerbate related conditions (eg, atopic dermatitis), but again, many patients deny any such connection.

When confronted with this clinical picture, dermatology providers are trained to look at the patient’s feet, where a flare of tinea pedis can sometimes be found. This common foot infection can, under certain circumstances, trigger a clinically indistinguishable pompholyx-like eruption on the hands, called an id reaction. In these cases, the tinea pedis always precedes the hand rash. Both resolve with adequate treatment (ie, oral antifungals).

The differential also includes irritant or contact dermatitis. However, patients are likely to report a contributing factor early on, lessening the clinical mystery.

A major diagnostic clue in this and similar cases is the effect on the cuticles and nails. Both are good indicators of the chronicity and nature of the problem.

TREATMENT

Treatment of pompholyx is notoriously difficult. Potent topical corticosteroids (eg, clobetasol cream), applied under occlusion to dampened skin at bedtime, are the cornerstone. In this and many such cases, while not curative by themselves, oral antibiotics can help to reduce colonization by staphylococcus.

A two-week course of prednisone (eg, 20 mg bid for a week, then 20 mg/d for another week) can be extremely helpful. Alternatively, an intramuscular injection of triamcinolone (40 to 60 mg) can be used, especially if the patient has a history of reflux or peptic ulcer. Relative contraindications to systemic steroid use include diabetes, poorly controlled hypertension, congestive heart failure, and dementia.

Phototherapy has also been used, but botulinum injection is becoming common in cases in which hyperhidrosis is the major culprit.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Pompholyx manifests as a papulosquamous, well-defined rash, often composed of tiny fluid-filled blisters, on the fingers and hand.

• The cause of this condition is unknown, but potential triggers include atopy, stress, hyperhidrosis, and ingestion of metals (eg, nickel or cobalt).

• Since acute tinea pedis can trigger a similar eruption on the hands (and responds to oral antifungals, as does pompholyx), checking the patient’s feet can provide a diagnostic clue.

• Patients may find it helpful to apply a potent topical corticosteroid cream (eg, clobetasol) to dampened hands (which allows for increased penetration of the medication) and cover with cotton gloves overnight.

HISTORY

Rashes of the hand are commonly seen in both primary care and dermatology practices. Their location makes them problematic, in terms of interference with normal activities and difficulty with treatment.

This 51-year-old man’s rash appeared about a month ago, with no premonitory signs. He has consulted numerous providers about it, including his primary care clinician. That practitioner diagnosed a probable “fungal infection” and prescribed a combination clotrimazole/betamethasone dipropionate cream. The rash subsequently improved, though not substantially.

The patient recalls developing a similar rash several other times during adulthood, but says it was never this severe. His mother has had similar eruptions, as well as sensitive skin in general. Both the patient and his mother are plagued by seasonal allergies, asthma, and sweating of the palms.

EXAMINATION

The distal portions of the second through fourth fingers of the right hand are affected. This is typical, according to the patient. The cuticles of all four affected nails are detached from the nail plates, with two of the three nail plates showing mild transverse ridging.

There is circumferential involvement of the distal half of all four fingers, with a well-defined margin and a blistery look to the papulosquamous process. Neither the left hand nor the feet are impacted.

DISCUSSION

This is a classic picture of a condition that goes by several names, most commonly pompholyx, also known as dishidrotic eczema. Despite the efforts of many investigators, with much information gleaned, it remains quite mysterious. It can be chronic or acute and can closely resemble what is known simply as hand dermatitis.

Pompholyx is associated with atopy in at least 50% of cases (such as this one). Hyperhidrosis of the palms is also common, and resolution of difficult cases has been achieved with injection of botulinum toxin A. This hypothesis is bolstered by the fact that many patients report onset in summer months; however, there are many whose history fails to follow this pattern.

Research has revealed that more than a few patients with pompholyx are allergic to one of several ingested metals, such as nickel and cobalt. But challenge tests with those substances have failed to consistently replicate the eruption.

Stress is another reported factor in the genesis of this condition. It is well known to exacerbate related conditions (eg, atopic dermatitis), but again, many patients deny any such connection.

When confronted with this clinical picture, dermatology providers are trained to look at the patient’s feet, where a flare of tinea pedis can sometimes be found. This common foot infection can, under certain circumstances, trigger a clinically indistinguishable pompholyx-like eruption on the hands, called an id reaction. In these cases, the tinea pedis always precedes the hand rash. Both resolve with adequate treatment (ie, oral antifungals).

The differential also includes irritant or contact dermatitis. However, patients are likely to report a contributing factor early on, lessening the clinical mystery.

A major diagnostic clue in this and similar cases is the effect on the cuticles and nails. Both are good indicators of the chronicity and nature of the problem.

TREATMENT

Treatment of pompholyx is notoriously difficult. Potent topical corticosteroids (eg, clobetasol cream), applied under occlusion to dampened skin at bedtime, are the cornerstone. In this and many such cases, while not curative by themselves, oral antibiotics can help to reduce colonization by staphylococcus.

A two-week course of prednisone (eg, 20 mg bid for a week, then 20 mg/d for another week) can be extremely helpful. Alternatively, an intramuscular injection of triamcinolone (40 to 60 mg) can be used, especially if the patient has a history of reflux or peptic ulcer. Relative contraindications to systemic steroid use include diabetes, poorly controlled hypertension, congestive heart failure, and dementia.

Phototherapy has also been used, but botulinum injection is becoming common in cases in which hyperhidrosis is the major culprit.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Pompholyx manifests as a papulosquamous, well-defined rash, often composed of tiny fluid-filled blisters, on the fingers and hand.

• The cause of this condition is unknown, but potential triggers include atopy, stress, hyperhidrosis, and ingestion of metals (eg, nickel or cobalt).

• Since acute tinea pedis can trigger a similar eruption on the hands (and responds to oral antifungals, as does pompholyx), checking the patient’s feet can provide a diagnostic clue.

• Patients may find it helpful to apply a potent topical corticosteroid cream (eg, clobetasol) to dampened hands (which allows for increased penetration of the medication) and cover with cotton gloves overnight.

HISTORY

Rashes of the hand are commonly seen in both primary care and dermatology practices. Their location makes them problematic, in terms of interference with normal activities and difficulty with treatment.

This 51-year-old man’s rash appeared about a month ago, with no premonitory signs. He has consulted numerous providers about it, including his primary care clinician. That practitioner diagnosed a probable “fungal infection” and prescribed a combination clotrimazole/betamethasone dipropionate cream. The rash subsequently improved, though not substantially.

The patient recalls developing a similar rash several other times during adulthood, but says it was never this severe. His mother has had similar eruptions, as well as sensitive skin in general. Both the patient and his mother are plagued by seasonal allergies, asthma, and sweating of the palms.

EXAMINATION

The distal portions of the second through fourth fingers of the right hand are affected. This is typical, according to the patient. The cuticles of all four affected nails are detached from the nail plates, with two of the three nail plates showing mild transverse ridging.

There is circumferential involvement of the distal half of all four fingers, with a well-defined margin and a blistery look to the papulosquamous process. Neither the left hand nor the feet are impacted.

DISCUSSION

This is a classic picture of a condition that goes by several names, most commonly pompholyx, also known as dishidrotic eczema. Despite the efforts of many investigators, with much information gleaned, it remains quite mysterious. It can be chronic or acute and can closely resemble what is known simply as hand dermatitis.

Pompholyx is associated with atopy in at least 50% of cases (such as this one). Hyperhidrosis of the palms is also common, and resolution of difficult cases has been achieved with injection of botulinum toxin A. This hypothesis is bolstered by the fact that many patients report onset in summer months; however, there are many whose history fails to follow this pattern.

Research has revealed that more than a few patients with pompholyx are allergic to one of several ingested metals, such as nickel and cobalt. But challenge tests with those substances have failed to consistently replicate the eruption.

Stress is another reported factor in the genesis of this condition. It is well known to exacerbate related conditions (eg, atopic dermatitis), but again, many patients deny any such connection.

When confronted with this clinical picture, dermatology providers are trained to look at the patient’s feet, where a flare of tinea pedis can sometimes be found. This common foot infection can, under certain circumstances, trigger a clinically indistinguishable pompholyx-like eruption on the hands, called an id reaction. In these cases, the tinea pedis always precedes the hand rash. Both resolve with adequate treatment (ie, oral antifungals).

The differential also includes irritant or contact dermatitis. However, patients are likely to report a contributing factor early on, lessening the clinical mystery.

A major diagnostic clue in this and similar cases is the effect on the cuticles and nails. Both are good indicators of the chronicity and nature of the problem.

TREATMENT

Treatment of pompholyx is notoriously difficult. Potent topical corticosteroids (eg, clobetasol cream), applied under occlusion to dampened skin at bedtime, are the cornerstone. In this and many such cases, while not curative by themselves, oral antibiotics can help to reduce colonization by staphylococcus.

A two-week course of prednisone (eg, 20 mg bid for a week, then 20 mg/d for another week) can be extremely helpful. Alternatively, an intramuscular injection of triamcinolone (40 to 60 mg) can be used, especially if the patient has a history of reflux or peptic ulcer. Relative contraindications to systemic steroid use include diabetes, poorly controlled hypertension, congestive heart failure, and dementia.

Phototherapy has also been used, but botulinum injection is becoming common in cases in which hyperhidrosis is the major culprit.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Pompholyx manifests as a papulosquamous, well-defined rash, often composed of tiny fluid-filled blisters, on the fingers and hand.

• The cause of this condition is unknown, but potential triggers include atopy, stress, hyperhidrosis, and ingestion of metals (eg, nickel or cobalt).

• Since acute tinea pedis can trigger a similar eruption on the hands (and responds to oral antifungals, as does pompholyx), checking the patient’s feet can provide a diagnostic clue.

• Patients may find it helpful to apply a potent topical corticosteroid cream (eg, clobetasol) to dampened hands (which allows for increased penetration of the medication) and cover with cotton gloves overnight.

All of Her Friends Say She Has Ringworm

ANSWER

The correct answer is pityriasis rosea (PR; choice “d”), which is commonly seen in patients ages 10 to 35 and is about twice as likely to occur in women as in men.

Lichen planus (LP; choice “a”) can mimic PR but lacks the peculiar centripetal scale and oval shape. Furthermore, it does not present with a herald patch.

Guttate psoriasis (choice “b”) could easily be confused for PR. However, it displays heavier white uniform scales with a salmon-pink base, tends to have a distinctly round configuration, and does not involve the appearance of a herald patch.

Secondary syphilis (choice “c”) can usually be ruled out by the sexual history, but also by the lack of a herald patch and the absence of centripetal scaling. Highly variable in appearance, the lesions of secondary syphilis are often seen on the palms.

DISCUSSION

PR was first described in 1860 by Camille Gibert, who used the term pityriasis to describe the fine scale seen with this condition, and chose the term rosea to denote the rosy or pink color.

For a variety of reasons, PR is assumed to be a viral exanthema since, as with many such eruptions, its incidence clusters in the fall and spring, it occurs in close contacts and families, and it is commonly seen in immunocompromised patients. In addition, acquiring the condition appears to confer lifelong immunity.

However, the jury is still out with regard to the exact virus responsible for the disease. Human herpesviruses 6 and 7 are the strongest candidates in terms of antibody production, but no herpesviral particles have been detected in tissue samples.

The so-called herald patch appears initially, in a majority of cases, as a salmon-pink patch that can become as large as 5 to 10 cm, on the trunk or arms. The smaller oval lesions begin to appear within a week or two, averaging 1 to 2 cm in diameter; most display the characteristic “centripetal” scaling, clearly sparing the lesions’ periphery and serving as an essentially pathognomic finding.

On darker-skinned patients, the lesions (including the herald patch) will tend to be brown to black. The examiner must then look for the other characteristic aspects of PR, including the oval (as opposed to round) shape, the long axes of which will often parallel the skin tension lines on the back to produce what is termed the “Christmas tree pattern.” In the author’s experience, the most consistent diagnostic finding is the centripetal scaling seen in at least a few lesions.

Since secondary syphilis is a major item in the differential, obtaining a careful sexual history is essential. If this is uncertain, or if the lesions are not a good fit for PR, obtaining a punch biopsy and serum rapid plasma reagin is necessary. The biopsy in secondary syphilis will show an infiltrate largely composed of plasma cells.

TREATMENT

Once the diagnosis of PR is made, patient education is essential. Affected patients should be reassured about the benign and self-limiting nature of the problem, but also about the likelihood that the condition will persist for up to nine weeks. Darker-skinned patients need to understand that the hyperpigmentation will last for months after the condition has resolved.

Relief of the itching experienced by 75% of PR patients can be achieved with topical steroids (eg, triamcinolone 0.1% cream) and oral antihistamines at bedtime (eg, hydroxyzine 25 to 50 mg) and/or during the daytime (cetirizine 10 mg/d), plus the liberal use of soothing OTC lotions (eg, those containing camphor and menthol). Systemic steroids appear to prolong the condition and are not terribly helpful in controlling the symptoms. In severe cases, phototherapy (narrow-band UVB) can be useful in controlling the itching.

ANSWER

The correct answer is pityriasis rosea (PR; choice “d”), which is commonly seen in patients ages 10 to 35 and is about twice as likely to occur in women as in men.

Lichen planus (LP; choice “a”) can mimic PR but lacks the peculiar centripetal scale and oval shape. Furthermore, it does not present with a herald patch.

Guttate psoriasis (choice “b”) could easily be confused for PR. However, it displays heavier white uniform scales with a salmon-pink base, tends to have a distinctly round configuration, and does not involve the appearance of a herald patch.

Secondary syphilis (choice “c”) can usually be ruled out by the sexual history, but also by the lack of a herald patch and the absence of centripetal scaling. Highly variable in appearance, the lesions of secondary syphilis are often seen on the palms.

DISCUSSION

PR was first described in 1860 by Camille Gibert, who used the term pityriasis to describe the fine scale seen with this condition, and chose the term rosea to denote the rosy or pink color.

For a variety of reasons, PR is assumed to be a viral exanthema since, as with many such eruptions, its incidence clusters in the fall and spring, it occurs in close contacts and families, and it is commonly seen in immunocompromised patients. In addition, acquiring the condition appears to confer lifelong immunity.

However, the jury is still out with regard to the exact virus responsible for the disease. Human herpesviruses 6 and 7 are the strongest candidates in terms of antibody production, but no herpesviral particles have been detected in tissue samples.

The so-called herald patch appears initially, in a majority of cases, as a salmon-pink patch that can become as large as 5 to 10 cm, on the trunk or arms. The smaller oval lesions begin to appear within a week or two, averaging 1 to 2 cm in diameter; most display the characteristic “centripetal” scaling, clearly sparing the lesions’ periphery and serving as an essentially pathognomic finding.

On darker-skinned patients, the lesions (including the herald patch) will tend to be brown to black. The examiner must then look for the other characteristic aspects of PR, including the oval (as opposed to round) shape, the long axes of which will often parallel the skin tension lines on the back to produce what is termed the “Christmas tree pattern.” In the author’s experience, the most consistent diagnostic finding is the centripetal scaling seen in at least a few lesions.

Since secondary syphilis is a major item in the differential, obtaining a careful sexual history is essential. If this is uncertain, or if the lesions are not a good fit for PR, obtaining a punch biopsy and serum rapid plasma reagin is necessary. The biopsy in secondary syphilis will show an infiltrate largely composed of plasma cells.

TREATMENT

Once the diagnosis of PR is made, patient education is essential. Affected patients should be reassured about the benign and self-limiting nature of the problem, but also about the likelihood that the condition will persist for up to nine weeks. Darker-skinned patients need to understand that the hyperpigmentation will last for months after the condition has resolved.

Relief of the itching experienced by 75% of PR patients can be achieved with topical steroids (eg, triamcinolone 0.1% cream) and oral antihistamines at bedtime (eg, hydroxyzine 25 to 50 mg) and/or during the daytime (cetirizine 10 mg/d), plus the liberal use of soothing OTC lotions (eg, those containing camphor and menthol). Systemic steroids appear to prolong the condition and are not terribly helpful in controlling the symptoms. In severe cases, phototherapy (narrow-band UVB) can be useful in controlling the itching.

ANSWER

The correct answer is pityriasis rosea (PR; choice “d”), which is commonly seen in patients ages 10 to 35 and is about twice as likely to occur in women as in men.

Lichen planus (LP; choice “a”) can mimic PR but lacks the peculiar centripetal scale and oval shape. Furthermore, it does not present with a herald patch.

Guttate psoriasis (choice “b”) could easily be confused for PR. However, it displays heavier white uniform scales with a salmon-pink base, tends to have a distinctly round configuration, and does not involve the appearance of a herald patch.

Secondary syphilis (choice “c”) can usually be ruled out by the sexual history, but also by the lack of a herald patch and the absence of centripetal scaling. Highly variable in appearance, the lesions of secondary syphilis are often seen on the palms.

DISCUSSION

PR was first described in 1860 by Camille Gibert, who used the term pityriasis to describe the fine scale seen with this condition, and chose the term rosea to denote the rosy or pink color.

For a variety of reasons, PR is assumed to be a viral exanthema since, as with many such eruptions, its incidence clusters in the fall and spring, it occurs in close contacts and families, and it is commonly seen in immunocompromised patients. In addition, acquiring the condition appears to confer lifelong immunity.

However, the jury is still out with regard to the exact virus responsible for the disease. Human herpesviruses 6 and 7 are the strongest candidates in terms of antibody production, but no herpesviral particles have been detected in tissue samples.

The so-called herald patch appears initially, in a majority of cases, as a salmon-pink patch that can become as large as 5 to 10 cm, on the trunk or arms. The smaller oval lesions begin to appear within a week or two, averaging 1 to 2 cm in diameter; most display the characteristic “centripetal” scaling, clearly sparing the lesions’ periphery and serving as an essentially pathognomic finding.

On darker-skinned patients, the lesions (including the herald patch) will tend to be brown to black. The examiner must then look for the other characteristic aspects of PR, including the oval (as opposed to round) shape, the long axes of which will often parallel the skin tension lines on the back to produce what is termed the “Christmas tree pattern.” In the author’s experience, the most consistent diagnostic finding is the centripetal scaling seen in at least a few lesions.

Since secondary syphilis is a major item in the differential, obtaining a careful sexual history is essential. If this is uncertain, or if the lesions are not a good fit for PR, obtaining a punch biopsy and serum rapid plasma reagin is necessary. The biopsy in secondary syphilis will show an infiltrate largely composed of plasma cells.

TREATMENT

Once the diagnosis of PR is made, patient education is essential. Affected patients should be reassured about the benign and self-limiting nature of the problem, but also about the likelihood that the condition will persist for up to nine weeks. Darker-skinned patients need to understand that the hyperpigmentation will last for months after the condition has resolved.

Relief of the itching experienced by 75% of PR patients can be achieved with topical steroids (eg, triamcinolone 0.1% cream) and oral antihistamines at bedtime (eg, hydroxyzine 25 to 50 mg) and/or during the daytime (cetirizine 10 mg/d), plus the liberal use of soothing OTC lotions (eg, those containing camphor and menthol). Systemic steroids appear to prolong the condition and are not terribly helpful in controlling the symptoms. In severe cases, phototherapy (narrow-band UVB) can be useful in controlling the itching.

Three weeks ago, a 25-year-old woman noticed an asymp¬tomatic lesion of unknown origin on her chest. Since then, smaller versions have appeared in “crops” on her trunk, arms, and lower neck. Friends were unanimous in their opinion that she had “ringworm,” so she consulted her pharmacist, who recommended clotrimazole cream. Despite her use of it, however, the lesions continue to increase in number. Her original lesion has become less red and scaly, though. The patient has felt fine from the outset and maintains that she is “quite healthy” in other respects. Employed as an IT technician, she denies any exposure to children, pets, or sexually transmitted diseases. The patient, who is African-American, has type V skin. Her original lesion—located on her left inframammary chest—is dark brown, macular, oval to round, and measures about 3.8 cm. On her trunk, arms, and lower neck, 15 to 20 oval, papulosquamous lesions are seen; these are widely scattered, all hyperpigmented (brown), and average 1.5 cm in diameter. Several of these smaller lesions have scaly centers that spare the peripheral margins. The long axes of her oval back lesions are parallel with natural lines of cleavage in the skin.

Why This Child Hates to Put On Socks

ANSWER

The correct answer is juvenile plantar dermatosis (JPD; choice “b”). It is a condition related to having thin, dry, hyperreactive skin exposed to friction, wetting and drying, and constant exposure to the nonpermeable surfaces of shoes.

Pitted keratolysis (choice “a”) is a condition caused by sweating and increased warmth. The plantar keratin is broken down with the help of bacteria that overgrow in affected areas; this eventuates in focal loss of keratin in arcuate patterns. It is quite unlikely to occur prior to puberty.

Tinea pedis (choice “c”) is dermatophytosis, or fungal infection of the foot. It is also unusual prior to puberty, unlikely to present in the manner seen in this case, and likely to have responded at least partially to antifungal creams.

Psoriasis (choice “d”) seldom presents with fissuring, would not be confined to weight-bearing surfaces, and would probably have involved other areas, such as the scalp, elbows, knees, or nails.

DISCUSSION

JPD, also known as juvenile plantar dermatitis, is found almost exclusively on the weight-bearing surfaces of the feet of children ages 4 to 8—mostly boys, for whom this represents a manifestation of the atopic diathesis. Seen mostly in the summer, it is thought to be triggered by friction, wetting and drying, and shoe selection (ie, plastic rather than leather soles).

Affected children not only have dry, sensitive skin; their skin is actually thin and fragile as well. Plastic or other synthetic shoe surfaces worn in the summertime are thought to contribute to the friction, heat, and sweating necessary to produce these changes.

As in this case, JPD is often mistaken for tinea pedis but has nothing to do with infection of any kind. Tinea pedis is uncommon in children this young, and it would present in completely different ways, such as between the toes (especially the fourth and fifth) or with blisters on the instep.

Psoriasis, though not unknown in this age-group, does not resemble JPD clinically at all. When suspected, the diagnosis of psoriasis can be corroborated by finding it elsewhere (eg, through a positive family history or biopsy).

Pitted keratolyis is common enough, but is seen in older teens and men whose feet are prone to sweat a great deal. The choice of shoes and occupation are often crucial factors in its development. The clinical hallmark is arcuate whitish maceration on weight-bearing surfaces, which are often malodorous as well.

TREATMENT

The first treatment for JPD is education of parents and patients, reassuring them about the relatively benign nature of the problem. Moisturizing frequently with petrolatum-based moisturizers is necessary for prevention, but changing the type of shoes worn is the most effective step to take; it is also the most difficult, since children this age favor cheap, plastic flip-flops or shoes in the summer.

For the fissures, spraying on a flexible spray bandage can be helpful in protecting them and allowing them to heal. With significant inflammation, the use of mild steroid ointments, such as hydrocortisone 2.5%, can help. But by far, the best relief comes with the change in season and the choice of shoe (leather-soled).

ANSWER

The correct answer is juvenile plantar dermatosis (JPD; choice “b”). It is a condition related to having thin, dry, hyperreactive skin exposed to friction, wetting and drying, and constant exposure to the nonpermeable surfaces of shoes.

Pitted keratolysis (choice “a”) is a condition caused by sweating and increased warmth. The plantar keratin is broken down with the help of bacteria that overgrow in affected areas; this eventuates in focal loss of keratin in arcuate patterns. It is quite unlikely to occur prior to puberty.

Tinea pedis (choice “c”) is dermatophytosis, or fungal infection of the foot. It is also unusual prior to puberty, unlikely to present in the manner seen in this case, and likely to have responded at least partially to antifungal creams.

Psoriasis (choice “d”) seldom presents with fissuring, would not be confined to weight-bearing surfaces, and would probably have involved other areas, such as the scalp, elbows, knees, or nails.

DISCUSSION

JPD, also known as juvenile plantar dermatitis, is found almost exclusively on the weight-bearing surfaces of the feet of children ages 4 to 8—mostly boys, for whom this represents a manifestation of the atopic diathesis. Seen mostly in the summer, it is thought to be triggered by friction, wetting and drying, and shoe selection (ie, plastic rather than leather soles).

Affected children not only have dry, sensitive skin; their skin is actually thin and fragile as well. Plastic or other synthetic shoe surfaces worn in the summertime are thought to contribute to the friction, heat, and sweating necessary to produce these changes.

As in this case, JPD is often mistaken for tinea pedis but has nothing to do with infection of any kind. Tinea pedis is uncommon in children this young, and it would present in completely different ways, such as between the toes (especially the fourth and fifth) or with blisters on the instep.

Psoriasis, though not unknown in this age-group, does not resemble JPD clinically at all. When suspected, the diagnosis of psoriasis can be corroborated by finding it elsewhere (eg, through a positive family history or biopsy).

Pitted keratolyis is common enough, but is seen in older teens and men whose feet are prone to sweat a great deal. The choice of shoes and occupation are often crucial factors in its development. The clinical hallmark is arcuate whitish maceration on weight-bearing surfaces, which are often malodorous as well.

TREATMENT

The first treatment for JPD is education of parents and patients, reassuring them about the relatively benign nature of the problem. Moisturizing frequently with petrolatum-based moisturizers is necessary for prevention, but changing the type of shoes worn is the most effective step to take; it is also the most difficult, since children this age favor cheap, plastic flip-flops or shoes in the summer.

For the fissures, spraying on a flexible spray bandage can be helpful in protecting them and allowing them to heal. With significant inflammation, the use of mild steroid ointments, such as hydrocortisone 2.5%, can help. But by far, the best relief comes with the change in season and the choice of shoe (leather-soled).

ANSWER

The correct answer is juvenile plantar dermatosis (JPD; choice “b”). It is a condition related to having thin, dry, hyperreactive skin exposed to friction, wetting and drying, and constant exposure to the nonpermeable surfaces of shoes.

Pitted keratolysis (choice “a”) is a condition caused by sweating and increased warmth. The plantar keratin is broken down with the help of bacteria that overgrow in affected areas; this eventuates in focal loss of keratin in arcuate patterns. It is quite unlikely to occur prior to puberty.

Tinea pedis (choice “c”) is dermatophytosis, or fungal infection of the foot. It is also unusual prior to puberty, unlikely to present in the manner seen in this case, and likely to have responded at least partially to antifungal creams.

Psoriasis (choice “d”) seldom presents with fissuring, would not be confined to weight-bearing surfaces, and would probably have involved other areas, such as the scalp, elbows, knees, or nails.

DISCUSSION

JPD, also known as juvenile plantar dermatitis, is found almost exclusively on the weight-bearing surfaces of the feet of children ages 4 to 8—mostly boys, for whom this represents a manifestation of the atopic diathesis. Seen mostly in the summer, it is thought to be triggered by friction, wetting and drying, and shoe selection (ie, plastic rather than leather soles).

Affected children not only have dry, sensitive skin; their skin is actually thin and fragile as well. Plastic or other synthetic shoe surfaces worn in the summertime are thought to contribute to the friction, heat, and sweating necessary to produce these changes.

As in this case, JPD is often mistaken for tinea pedis but has nothing to do with infection of any kind. Tinea pedis is uncommon in children this young, and it would present in completely different ways, such as between the toes (especially the fourth and fifth) or with blisters on the instep.

Psoriasis, though not unknown in this age-group, does not resemble JPD clinically at all. When suspected, the diagnosis of psoriasis can be corroborated by finding it elsewhere (eg, through a positive family history or biopsy).

Pitted keratolyis is common enough, but is seen in older teens and men whose feet are prone to sweat a great deal. The choice of shoes and occupation are often crucial factors in its development. The clinical hallmark is arcuate whitish maceration on weight-bearing surfaces, which are often malodorous as well.

TREATMENT

The first treatment for JPD is education of parents and patients, reassuring them about the relatively benign nature of the problem. Moisturizing frequently with petrolatum-based moisturizers is necessary for prevention, but changing the type of shoes worn is the most effective step to take; it is also the most difficult, since children this age favor cheap, plastic flip-flops or shoes in the summer.

For the fissures, spraying on a flexible spray bandage can be helpful in protecting them and allowing them to heal. With significant inflammation, the use of mild steroid ointments, such as hydrocortisone 2.5%, can help. But by far, the best relief comes with the change in season and the choice of shoe (leather-soled).

The distraught mother of an 8-year-old boy brings him urgently to dermatology for evaluation of a condition that has affected his feet for the past two summers. Convinced he has “caught” athlete’s foot, she tried several OTC antifungal creams and sprays, with no good effect. The patient denies symptoms except occasional stinging. In his view, the biggest problem is that the bottoms of his feet are so rough that he hates to put on socks. Additional history taking reveals that the child is markedly atopic, with seasonal allergies, asthma, dry, sensitive skin, and eczema. As an infant, his diaper rashes were so severe that he was hospitalized twice. On inspection, the weight-bearing surfaces of both feet are fissured and shiny, with modest inflammation evident. The plantar aspects of both big toes are especially affected. Though these areas are rough and dry, there is no edema, increased warmth, or tenderness on palpation. His skin elsewhere, though dry, is free of obvious lesions.

Edematous Changes Coincide with New Job

ANSWER

The correct answer is gram-negative bacteria (choice “d”); Pseudomonas is the most likely culprit. Candida albicans (choice “a”), a yeast, is an unlikely cause of this problem and even more unlikely to show up on a bacterial culture. Coagulase-positive staph aureus (choice “b”) is typically associated with infections involving the acute onset of redness, pain, swelling, and pus formation, not the indolent, chronic, low-grade process seen in this case. Trichophyton rubrum (choice “c”) is a dermatophyte, the most common fungal cause of athlete’s feet. The bacterial culture could not have grown a dermatophyte, which needs special media and conditions to grow.

DISCUSSSION

Gram-negative interweb impetigo is a relatively common dermatologic entity, which can be caused by any number of organisms found in fecal material. Pseudomonas, Klebsiella, Proteus, and Acinetobacter are among the more common culprits. These types of infections tend to be much more indolent than the more common staph- and strep-caused cellulitis, which are more likely to create acute redness, swelling, pain, and pus.

Both types of bacterial infections need certain conditions in order to develop. These include excessive heat, sweat, and perhaps most significantly, a break in the skin barrier. Ironically, these fissures are often caused by dermatophytes, in the form of tinea pedis, which is, of course, far better known for causing rashes of the foot.

But tinea pedis is more likely to be found between the third and fourth or the fourth and fifth toes. It creates itching and maceration but rarely causes diffuse redness or edema, and even more rarely leads to pain (unless there is a secondary bacterial infection). As mentioned, given the indolence of this infective process, a culture result showing staph or strep was unlikely.

The culture in this case showed Proteus, for which the minocycline was predictably effective. The rationale for obtaining the acid-fast culture was the possibility of finding Mycobacteria species such as M fortuitum, which is known to cause chronic indolent infections in feet and legs. These, however, more typically manifest with solitary eroded or ulcerated lesions. (Minocycline would have been effective against this organism.)

The use of the topical econazole served two purposes: While this was clearly not classic tinea pedis, it was still possible a dermatophyte or a yeast could have played a role in the creation of the initial fissuring; econazole will help control this, long term. Econazole also has significant antibacterial action and is particularly useful to help prevent future flares.

ANSWER

The correct answer is gram-negative bacteria (choice “d”); Pseudomonas is the most likely culprit. Candida albicans (choice “a”), a yeast, is an unlikely cause of this problem and even more unlikely to show up on a bacterial culture. Coagulase-positive staph aureus (choice “b”) is typically associated with infections involving the acute onset of redness, pain, swelling, and pus formation, not the indolent, chronic, low-grade process seen in this case. Trichophyton rubrum (choice “c”) is a dermatophyte, the most common fungal cause of athlete’s feet. The bacterial culture could not have grown a dermatophyte, which needs special media and conditions to grow.

DISCUSSSION

Gram-negative interweb impetigo is a relatively common dermatologic entity, which can be caused by any number of organisms found in fecal material. Pseudomonas, Klebsiella, Proteus, and Acinetobacter are among the more common culprits. These types of infections tend to be much more indolent than the more common staph- and strep-caused cellulitis, which are more likely to create acute redness, swelling, pain, and pus.

Both types of bacterial infections need certain conditions in order to develop. These include excessive heat, sweat, and perhaps most significantly, a break in the skin barrier. Ironically, these fissures are often caused by dermatophytes, in the form of tinea pedis, which is, of course, far better known for causing rashes of the foot.

But tinea pedis is more likely to be found between the third and fourth or the fourth and fifth toes. It creates itching and maceration but rarely causes diffuse redness or edema, and even more rarely leads to pain (unless there is a secondary bacterial infection). As mentioned, given the indolence of this infective process, a culture result showing staph or strep was unlikely.

The culture in this case showed Proteus, for which the minocycline was predictably effective. The rationale for obtaining the acid-fast culture was the possibility of finding Mycobacteria species such as M fortuitum, which is known to cause chronic indolent infections in feet and legs. These, however, more typically manifest with solitary eroded or ulcerated lesions. (Minocycline would have been effective against this organism.)

The use of the topical econazole served two purposes: While this was clearly not classic tinea pedis, it was still possible a dermatophyte or a yeast could have played a role in the creation of the initial fissuring; econazole will help control this, long term. Econazole also has significant antibacterial action and is particularly useful to help prevent future flares.

ANSWER

The correct answer is gram-negative bacteria (choice “d”); Pseudomonas is the most likely culprit. Candida albicans (choice “a”), a yeast, is an unlikely cause of this problem and even more unlikely to show up on a bacterial culture. Coagulase-positive staph aureus (choice “b”) is typically associated with infections involving the acute onset of redness, pain, swelling, and pus formation, not the indolent, chronic, low-grade process seen in this case. Trichophyton rubrum (choice “c”) is a dermatophyte, the most common fungal cause of athlete’s feet. The bacterial culture could not have grown a dermatophyte, which needs special media and conditions to grow.

DISCUSSSION

Gram-negative interweb impetigo is a relatively common dermatologic entity, which can be caused by any number of organisms found in fecal material. Pseudomonas, Klebsiella, Proteus, and Acinetobacter are among the more common culprits. These types of infections tend to be much more indolent than the more common staph- and strep-caused cellulitis, which are more likely to create acute redness, swelling, pain, and pus.

Both types of bacterial infections need certain conditions in order to develop. These include excessive heat, sweat, and perhaps most significantly, a break in the skin barrier. Ironically, these fissures are often caused by dermatophytes, in the form of tinea pedis, which is, of course, far better known for causing rashes of the foot.

But tinea pedis is more likely to be found between the third and fourth or the fourth and fifth toes. It creates itching and maceration but rarely causes diffuse redness or edema, and even more rarely leads to pain (unless there is a secondary bacterial infection). As mentioned, given the indolence of this infective process, a culture result showing staph or strep was unlikely.

The culture in this case showed Proteus, for which the minocycline was predictably effective. The rationale for obtaining the acid-fast culture was the possibility of finding Mycobacteria species such as M fortuitum, which is known to cause chronic indolent infections in feet and legs. These, however, more typically manifest with solitary eroded or ulcerated lesions. (Minocycline would have been effective against this organism.)

The use of the topical econazole served two purposes: While this was clearly not classic tinea pedis, it was still possible a dermatophyte or a yeast could have played a role in the creation of the initial fissuring; econazole will help control this, long term. Econazole also has significant antibacterial action and is particularly useful to help prevent future flares.

A 50-year-old man presents with a six-month history of worsening redness, swelling, and pain in the interdigital web spaces of both feet. Numerous treatments—most recently, a two-month course of terbinafine 250 mg/d—have not induced any change. The problem manifested as mild cracking between the first and second toes, dorsal aspect, and slowly spread laterally to involve all four web spaces. This pro-cess coincided with the start of a new job in which the patient is on his feet, wearing steel-toed boots, for 12 hours per day in a hot environment. Assuming the problem was athlete’s foot, he tried OTC clotrimazole and terbinafine creams; neither helped at all. In fact, the patient’s pain is now so bad that he has difficult walking. There is no history of smoking, diabetes, or other serious health problems. Examination shows distinct demarcated, dusky-red, edematous changes largely confined to the dorsal aspect. The actual deep interdigital space and the volar aspects of these areas are spared. Slight epidermal fissuring is seen on the dorsal aspect of each web space, from which a small amount of fluid can be coaxed. The fluid is sent for bacterial and acid-fast cultures. In the meantime, the patient is prescribed oral minocycline 100 bid and topical econazole cream and in-structed to return in two weeks. At that time, his condition is almost completely resolved.

Topical Steroids: the Solution or the Cause?

ANSWER

The correct answer is all of the above (choice “d”). Prolonged injudicious use of topical steroids can cause a number of problems, including these; they are collectively termed iatrogenic since they are ultimately caused by prescribed medication. One of the more difficult aspects of this problem to deal with is the “addictive” state, in which withdrawal symptoms compel the patient to continue applying the offending steroid cream.

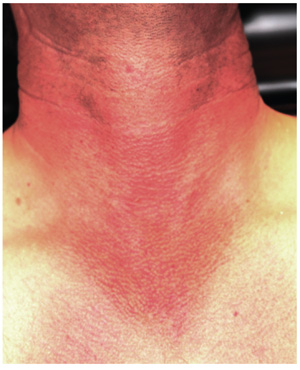

DISCUSSION

This is a relatively common scenario in dermatology offices. The misuse of topical steroids is well known, and something we strive to prevent—but with mixed results. It’s one of the reasons we’re stingy with refills of such medications, requiring the patient to be seen at least once a year. Unfortunately, this patient had been getting “refills” from friends in Mexico; patients often “borrow” steroid creams from household members or friends, or use products prescribed for one condition to treat others for which they were not intended.

The primary mode of action of topical steroids is vasoconstriction, a positive thing in terms of reduction of inflammation. The bad news is that continuous use of class 1 (the most powerful) steroids, such as clobetasol, can cause such profound and prolonged vasoconstriction that the skin effectively loses its blood supply and withers, sometimes down to adipose tissue. As one might suspect, this is more likely in already thin-skinned areas, including the antecubital area, face, neck, eyelids, and genitals, where the creation of striae is especially common.

Fairly early on in this process, before frank atrophy occurs, the condition being treated usually resolves. However, when the steroid is stopped, stinging and itching immediately return—which, of course, causes the patient to reapply the medication, perpetuating the vicious cycle.

The cycle is ultimately broken by gradual reduction in the frequency of application of successively weaker steroids. Usually, the skin gradually regenerates and returns to normal. In this case, the process will be lengthy and will almost certainly result in significant scarring.

Even injudicious application of weaker classes of steroids (eg, hydrocortisone 2.5% cream) to areas such as the face can result in a range of deleterious effects, including localized rosacea-like eruption or erythema. It has been reported that approximately 75% of cases of perioral dermatitis are either caused by or exacerbated by the application of topical steroids.

Topical application of even mid-strength steroids can also have systemic effects (eg, adrenal suppression, hyperglycemia) if applied over large areas. This is especially true when pediatric patients are involved.

Prevention of these iatrogenic effects lies in selecting the lowest strength steroid for the condition and area in question, then using them sparingly: no more than twice a day, and for no more than five days in a row, stopping for two consecutive days to allow the skin to regenerate. Even more caution should be exercised in treating children and when applying the product to intertriginous areas (skin-on-skin areas, such as the groin, in axillae, or under the breasts). Covering steroid-treated areas with anything—bandages, socks, even skin—effectively potentiates the positive and negative effects of steroids.

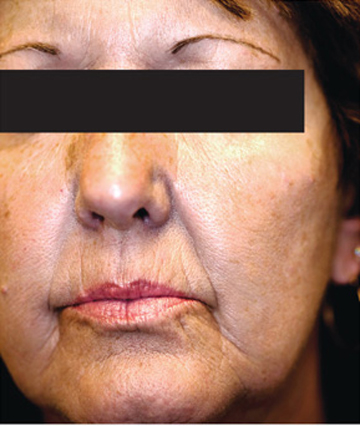

ANSWER

The correct answer is all of the above (choice “d”). Prolonged injudicious use of topical steroids can cause a number of problems, including these; they are collectively termed iatrogenic since they are ultimately caused by prescribed medication. One of the more difficult aspects of this problem to deal with is the “addictive” state, in which withdrawal symptoms compel the patient to continue applying the offending steroid cream.

DISCUSSION

This is a relatively common scenario in dermatology offices. The misuse of topical steroids is well known, and something we strive to prevent—but with mixed results. It’s one of the reasons we’re stingy with refills of such medications, requiring the patient to be seen at least once a year. Unfortunately, this patient had been getting “refills” from friends in Mexico; patients often “borrow” steroid creams from household members or friends, or use products prescribed for one condition to treat others for which they were not intended.

The primary mode of action of topical steroids is vasoconstriction, a positive thing in terms of reduction of inflammation. The bad news is that continuous use of class 1 (the most powerful) steroids, such as clobetasol, can cause such profound and prolonged vasoconstriction that the skin effectively loses its blood supply and withers, sometimes down to adipose tissue. As one might suspect, this is more likely in already thin-skinned areas, including the antecubital area, face, neck, eyelids, and genitals, where the creation of striae is especially common.

Fairly early on in this process, before frank atrophy occurs, the condition being treated usually resolves. However, when the steroid is stopped, stinging and itching immediately return—which, of course, causes the patient to reapply the medication, perpetuating the vicious cycle.