User login

Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor: Reflecting on 2 Decades of Clinical Advancements

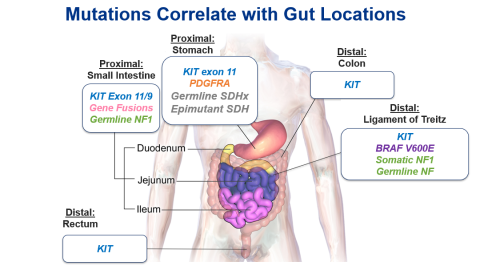

Since the early 2000s, new discoveries about GIST genomics have contributed to better, more targeted treatments. Some genomic mutations have been linked to specific gut regions,7 which may further help guide therapy as well.

GIST: What Is It, Who Gets It, and How Is It Diagnosed?

What, How Many, Where?

Even though GIST is considered rare—representing less than 1% of gastrointestinal tumors8—it is the most common sarcoma, which is a family of mesenchymal neoplasms. GISTs are thought to arise from the interstitial cells of Cajal, or the pacemaker cells of the gut that control peristalsis. In the United States, the incidence of GIST is roughly 4,000 to 6,000 new cases diagnosed per year, with most cases found in the stomach (60%) or small intestine (35%). Other gut regions in which GISTs may be identified include the rectum and esophagus.8

Although asymptomatic tumors are often discovered incidentally, GISTs that originate in the stomach—the most common primary tumor site—may present with nonspecific subjective symptoms such as pain, nausea, loss of appetite, early satiety, or bloating.9 Symptoms may vary according to tumor location (eg, stomach vs rectum vs esophagus), size, and pattern of growth. More objective signs could include anemia related to gastrointestinal bleeding, weight loss, or a palpable mass.9

Who?

Most cases of GIST occur in patients later in life, with a median age of 64 years at diagnosis. A slight predominance of men has been noted, along with African American and Asian individuals affected somewhat more frequently than White or Hispanic populations.10 GIST is rare in children and adolescents, and the symptoms and pathology differ from those in most adults.9 Previously age was considered a determining factor in the differences in GIST, with cases in children classified as “pediatric-type” GIST or “wild-type” GIST. These cases generally present in the stomach, are more likely to include lymph node involvement, and can also spread to the liver and abdominal lining. Importantly, they are usually not associated with the tyrosine-protein kinase (KIT) or platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA) gene mutations found in most adults.9 About 80% of these cases have hereditary mutations of the succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) enzyme complex. Because some adult cases of GIST share the distinct characteristics found in most pediatric cases, distinguishing them based on age, rather than on the specific genetic characteristics of the tumor, is unwarranted.9

How?

When GIST is suspected or when symptoms mandate further investigation, coordination among colleagues in imaging, gastroenterology, pathology, surgery, and oncology is critical for accurate diagnosis, staging, and treatment. Abdominal imaging may be ordered using modalities such as ultrasound, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and, occasionally, positron emission tomography.11 Endoscopic ultrasound is useful to identify and biopsy lesions in the stomach or rectum, as these tumors arise below the lining of the stomach or rectum. GIST diagnosis can be confirmed by biopsy during endoscopic ultrasound, which is the preferred approach, or by percutaneous biopsy when endoscopic biopsy is not feasible or safe.11

According to the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) and European Reference Group for Rare Adult Solid Cancers (EURACAN) Clinical Practice Guidelines, the “standard approach to tumors ≥ 2 cm in size is excision, because they are associated with a higher risk of progression if confirmed as GIST. If there is an abdominal nodule not amenable to endoscopic assessment, laparoscopic or laparotomic excision is the standard approach.”11

Genetic Mutations

A diagnosis of GIST is made based on the combination of the clinical scenario, the tumor’s anatomic location, immunohistochemistry patterns, and molecular features.12 Research has shown that genetic mutations in the KIT, PDGFRA, or SDH genes are present in most cases of GIST (70-80%,13 10%,12 and less than 10% of cases12,14 respectively) and their presence can be used for diagnosis. A growing number of rarer mutations have also been discovered,13 meaning that gene-based diagnosis of GIST is becoming increasingly sensitive. In addition, antigens on the surface of cancer cells can help classify them as GIST. For example, researchers have discovered that most GIST cells have the marker CD117, the protein product of the KIT gene that is commonly mutated in GIST, on their surfaces. A different marker, DOG1 (ie, Discovered On GIST 1), is also present on the vast majority of GISTs, but not unanimously overlapping with CD117. A tumor that is positive for both CD117 and DOG1 has a high probability (> 97%) of being GIST.15

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) is considered the best tool for determining both germline and somatic mutations in patients with GIST, and NGS is recommended by both the NCCN6 and the ESMO11 for individualizing systemic therapy. Despite these recommendations, most patients do not undergo genetic testing, both in the United States16 and internationally.17 Several barriers to genetic testing have been cited, predominately inadequate tissue and high cost. However, a study demonstrated that costs of up to $3,730 for genetic testing were ultimately cost-effective for tailoring therapy with first-line imatinib for patients with newly diagnosed metastatic GIST.18 Moreover, genetic testing also should be strongly considered for patients with nonmetastatic disease in whom systemic therapy is being considered.

Increasing evidence has emerged that gastric GIST mutations are related to tumor location within the gastrointestinal tract (Figure).7 The anatomic location of the GIST may provide clues for clinical decision-making and may guide selective confirmatory genomic testing when access to testing is limited.

Treatment of GIST

Surgery

Surgery remains the main treatment for localized GIST, especially if the tumor is discovered at an early stage. Unfortunately, up to a quarter of patients present with metastatic disease at diagnosis. The goal of surgery is to resect the tumor with histologically negative margins. Every effort should be made to avoid rupturing the tumor capsule during resection. Studies have shown that laparoscopic resection is feasible and safe for gastric GISTs and is less invasive than traditional open surgery, with similar oncological outcomes.19

Debulking surgery is sometimes considered for patients with metastatic disease, especially for patients who demonstrate sensitivity to TKI and whose disease has not yet progressed.20,21 Other interventions, such as microwave ablation or transhepatic arterial embolization, are sometimes used to control hepatic metastases.

Systemic Therapies

Whether systemic therapy is being considered in the neoadjuvant (preoperative), adjuvant (postoperative), or advanced disease setting, mutations in GIST determine the likelihood of treatment success. Both NCCN6 and ESMO11 strongly encourage use of mutational analyses and genetic testing for patients with GIST before systemic therapy is initiated.

In some cases of locally advanced GIST, tumors may be situated in particularly challenging anatomic locations(eg, esophagus, duodenum, rectum) or may require a highly morbid, multivisceral resection. In such situations, neoadjuvant treatment with imatinib,22,23 if deemed appropriate per mutational profiling, should be considered.

Patients who are determined to be at high risk for recurrence after surgery, based on tumor size, mitotic index determined by pathologist review of dividing cells, tumor location, and tumor rupture, may be eligible for adjuvant treatment with imatinib.24 Although the ideal duration of adjuvant therapy is not yet known, the current standard is at least 3 years,25 but many practitioners advocate for lifelong therapy.

Imatinib. Because chemotherapy was ineffective against GIST, prognosis was dismal for patients diagnosed with advanced disease before the approval of imatinib in the early 2000s.2 A selective TKI, imatinib targets the KIT and PDGFRA receptor kinases, and most patients experience clinical benefit,26 at least initially. Unfortunately, many tumors eventually develop resistance, and discontinuation of imatinib is associated with a risk for disease progression.27

Sunitinib. The emergence of resistance to imatinib spurred the search for second-line agents that might be useful after disease progression. Another TKI, sunitinib, which has both antitumor and antiangiogenic activity, was approved in 2006 for management of advanced imatinib-resistant GIST.28 Knowledge of a tumor’s driver mutation(s) can help optimize use of sunitinib.29

Regorafenib. In 2013, the FDA approved regorafenib, another TKI, as a third-line agent for patients with advanced GIST that is refractory to imatinib and sunitinib.30 Regorafenib exerts its activity against multiple targets, including VEGFR1-3, TIE2 (ie, antiangiogenic activity), PDGFR-β, FGFR (ie, stromal targets), and KIT, RET, and RAF (ie, oncogenic targets). As with other TKIs, common adverse effects associated with regorafenib treatment include hypertension, hand-foot skin reaction, rash, diarrhea, and fatigue.

Larotrectinib/entrectinib. The FDA approved larotrectinib31 (2018) and entrectinib32 (2019) as the first tumor-agnostic agents, whose use is based on the presence of specific genomic alteration, in this case NTRK. If a tumor, including a GIST, harbors a specific, albeit rare, gene fusion, it may be considered for treatment with one of these small-molecule TRK family inhibitors. Although these agents are not specifically indicated for GIST, some subjects enrolled in the trials had GIST harboring the target NTRK gene fusion and their tumors responded to treatment.

Ripretinib. FDA-approved in 2020,33 ripretinib is a novel TKI indicated for adult patients with advanced GIST who have received prior treatment with 3 or more kinase inhibitors, including imatinib. A phase 3 trial demonstrated improved progression-free and overall survival when ripretinib was compared with placebo in patients who had disease progression after treatment with imatinib, sunitinib, or regorafenib.34 Ripretinib is now being investigated in the second-line setting in selected patients with KIT mutations.

Avapritinib. Cases of GIST with PDGFRA D842V-mutant tumors often demonstrate primary resistance to imatinib and sunitinib. In 2020, avapritinib, a selective TKI that targets both KIT and PDGFRA, was approved35 for treatment of patients with unresectable or metastatic GIST harboring a PDGFRA exon 18 mutation, including D842V mutations. However, it is noteworthy that many of the non-D842V mutations in PDGFRA respond to imatinib.

Dabrafenib/trametinib. In 2022, the FDA issued an approval for treatment based on a driver mutation rather than tumor type. Acknowledging that a BRAF mutation—specifically a V600E mutation—appears to be a critical target in several cancers, the FDA granted accelerated approval for the use of dabrafenib plus trametinib in adults and children 6 years of age and older with unresectable or metastatic solid tumors with BRAF V600E mutation who have progressed following prior treatment and have no satisfactory alternative treatment options.36

Researchers have studied additional TKIs in the setting of unresectable, metastatic disease due to the varied genomic landscape of GIST. The NCCN Guidelines include evidence of some benefit for agents such as dasatinib, cabozantinib, everolimus (plus a TKI), nilotinib, pazopanib, and sorafenib “in certain circumstances.”6

The Future of GIST

The most critical step toward optimal treatment decision-making when a patient has been diagnosed with GIST is identification of physicians with expertise in the care of patients with GIST. With increasing knowledge of genomic variations in GIST, patient care has become less prescripted and much more personalized. To that end, determination of the tumor’s genetic mutational profile is critical to guiding treatment. Although factors such as cost, availability/accessibility, and insufficient tissue continue to represent substantial obstacles, pursing this information may be the most important way that clinicians can advocate for their patients. Moreover, now that the anatomic location of GIST has been linked to specific driver mutations, the ability to select and refine treatments may improve significantly.

Likewise, in view of the increasing complexity and multidisciplinary management of patients with GIST, efficient coordination is paramount among surgical and medical oncologists, as well as radiologists, gastroenterologists, and pathologists.

- Miettinen M, Virolainen M, Maarit-Sarlomo-Rikala. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors—value of CD34 antigen in their identification and separation from true leiomyomas and schwannomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19(2):207-216. doi:10.1097/00000478-199502000-00009

- Dagher R, Cohen M, Williams G, et al. Approval summary: imatinib mesylate in the treatment of metastatic and/or unresectable malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(10):3034-3038. PMID:12374669

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves larotrectinib for solid tumors with NTRK gene fusions [press release]. Published November 26, 2018. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/fda-approves-larotrectinib-solid-tumors-ntrk-gene-fusions

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves entrectinib for NTRK solid tumors and ROS-1 NSCLC [press release]. Published August 15, 2019. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-entrectinib-ntrk-solid-tumors-and-ros-1-nsclc

- Winstead W. Dabrafenib-trametinib combination approved for solid tumors with BRAF mutations. National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. Published July 21, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2022/fda-dabrafenib-trametinib-braf-solid-tumors

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinic practice guidelines in oncology: gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Version 1.2023. March 13, 2023. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/gist.pdf

- Sharma AK, de la Torre J, IJzerman NS, et al. Location of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) in the stomach predicts tumor mutation profile and drug sensitivity. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(19):5334-5342. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-1221

- Gastrointestinal stromal tumor—GIST: statistics. Cancer.net. Published March 2023. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/gastrointestinal-stromal-tumor-gist/statistics

- Sicklick J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors - symptoms, causes, treatment: NORD. National Organization for Rare Disorders. Published January 12, 2023. Accessed March 28, 2023. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/gastrointestinal-stromal-tumors/

- Ma GL, Murphy JD, Martinez ME, Sicklick JK. Epidemiology of gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the era of histology codes: results of a population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;24(1):298-302. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-1002

- Casali PG, Abecassis N, Aro HT, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMOEURACAN Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(suppl 4):iv68-iv78. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdy095

- Kelly CM, Sainz LG, Chi P. The management of metastatic GIST: current standard and investigational therapeutics. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14(1):2. doi:10.1186/s13045-020-01026-6

- Shi E, Chmielecki J, Tang CM, et al. FGR1 and NTRK3 actionable alterations in “wild-type” gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Translat Med. 2016;14(1):339. doi:10.1186/s12967-016-1075-6

- Bannon AE, Klug LR, Corless CL, Heinrich MC. Using molecular diagnostic testing to personalize the treatment of patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2017;17(5):445-457. doi:10.1080/14737159.2017.1308826

- Wu CE, Tzen CY, Wang SY, Yeh CN. Clinical diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST): from the molecular genetic point of view. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(5):679. doi:10.3390/cancers11050679

- Florindez J, Trent J. Low frequency of mutation testing in the United States: an analysis of 3866 GIST patients. Am J Clin Oncol. 2020;43(4):270-278. doi:10.1097/COC.0000000000000659

- Verschoor AJ, Bovée JVMG, Overbeek LIH, PALGA group; Hogendoorn PCW, Gelderblom H. The incidence, mutational status, risk classification and referral pattern of gastrointestinal stromal tumours in the Netherlands: a nationwide pathology registry (PALGA) study. Virchows Arch. 2018;472(2):221-229. doi:10.1007/s00428-017-2285-x

- Banerjee S, Kumar A, Lopez N, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of genetic testing and tailored first-line therapy for patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2013565. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.1356519

- Chen K, Zhou YC, Mou YP, Xu XW, Jin WW, Ajoodhea H. Systematic review and meta-analysis of safety and efficacy of laparoscopic resection of gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:355-367. doi:10.1007/s00464-014-3676-6

- Fairweather M, Balachandran VP, Li GZ, et al. Cytoreductive surgery for metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: a 2-institutional analysis. Ann Surg. 2018;268(2):296-302. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000002281

- Bauer S, Rutkowski P, Hohenberger P, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with GIST undergoing metastasectomy in the era of imatinib—analysis of prognostic factors (EORTC-STBSG collaborative study). Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40(4):412-419. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2013.12.020

- Rutkowski P, Gronchi A, Hohenberger P, et al. Neoadjuvant imatinib in locally advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST): the EORTC STBSG experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(9):2937-2943. doi:10.1245/s10434-013-3013-7

- Cavnar MJ, Seier K, Gönen M, et al. Prognostic factors after neoadjuvant imatinib for newly diagnosed primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Gastrointest Surg. 2021;25(7):1828-1836. doi:10.1007/s11605-020-04843-9

- Joensuu H. Risk stratification of patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Hum Pathol. 2008;39(10):1411-1419. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2008.06.025

- Joensuu H, Eriksson M, Sundby Hall K, et al. Survival outcomes associated with 3 years vs 1 year of adjuvant imatinib for patients with high-risk gastrointestinal stromal tumors: an analysis of a randomized clinical trial after 10-year follow-up. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(8):1241-1246. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.2091

- Heinrich MC, Rankin C, Blanke CD, et al. Correlation of long-term results of imatinib in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors with next-generation sequencing results: analysis of phase 3 SWOG Intergroup Trial S0033. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(7):944-952. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6728

- Le Cesne A, Ray-Coquard I, Bui BN, et al. Discontinuation of imatinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumours after 3 years of treatment: an open-label multicentre randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;11(10):942-949. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70222-9

- Demetri GD, van Oosterom AT, Garrett CR, et al. Efficacy and safety of sunitinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumour after failure of imatinib: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;368(9544):1329-1338. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69446-4

- Heinrich MC, Maki RG, Corless CL, et al. Primary and secondary kinase genotypes correlate with the biological and clinical activity of sunitinib in imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(33):5352-5359. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.15.7461

- Crona DJ, Keisler MD, Walko CM. Regorafenib: a novel multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor for colorectal and gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(12):1685-1696. doi:10.1177/1060028013509792

- Drilon A, Laetsch TW, Kummar S, et al. Efficacy of larotrectinib in TRK fusion-positive cancers in adults and children. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(8):731-739. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1714448

- Doebele RC, Drilon A, Paz-Ares L, et al. Entrectinib in patients with advanced or metastatic NTRK fusion-positive solid tumours: integrated analysis of three phase 1-2 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(2):271-282. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30691-6

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves ripretinib for advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor [press release]. Published May 15, 2020. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-ripretinib-advanced-gastrointestinal-stromal-tumor

- Blay JY, Serrano C, Heinrich MC, et al. Ripretinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumours (INVICTUS): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(7):923-934. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30168-6

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves avapritinib for gastrointestinal stromal tumor with a rare mutation [press release]. Published January 9, 2020. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-avapritinib-gastrointestinal-stromal-tumor-rare-mutation

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA grants accelerated approval to dabrafenib in combination with trametinib for unresectable or metastatic solid tumors with BRAF V600E mutation [press release]. Published June 22, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-dabrafenib-combination-trametinib-unresectable-or-metastatic-solid

Since the early 2000s, new discoveries about GIST genomics have contributed to better, more targeted treatments. Some genomic mutations have been linked to specific gut regions,7 which may further help guide therapy as well.

GIST: What Is It, Who Gets It, and How Is It Diagnosed?

What, How Many, Where?

Even though GIST is considered rare—representing less than 1% of gastrointestinal tumors8—it is the most common sarcoma, which is a family of mesenchymal neoplasms. GISTs are thought to arise from the interstitial cells of Cajal, or the pacemaker cells of the gut that control peristalsis. In the United States, the incidence of GIST is roughly 4,000 to 6,000 new cases diagnosed per year, with most cases found in the stomach (60%) or small intestine (35%). Other gut regions in which GISTs may be identified include the rectum and esophagus.8

Although asymptomatic tumors are often discovered incidentally, GISTs that originate in the stomach—the most common primary tumor site—may present with nonspecific subjective symptoms such as pain, nausea, loss of appetite, early satiety, or bloating.9 Symptoms may vary according to tumor location (eg, stomach vs rectum vs esophagus), size, and pattern of growth. More objective signs could include anemia related to gastrointestinal bleeding, weight loss, or a palpable mass.9

Who?

Most cases of GIST occur in patients later in life, with a median age of 64 years at diagnosis. A slight predominance of men has been noted, along with African American and Asian individuals affected somewhat more frequently than White or Hispanic populations.10 GIST is rare in children and adolescents, and the symptoms and pathology differ from those in most adults.9 Previously age was considered a determining factor in the differences in GIST, with cases in children classified as “pediatric-type” GIST or “wild-type” GIST. These cases generally present in the stomach, are more likely to include lymph node involvement, and can also spread to the liver and abdominal lining. Importantly, they are usually not associated with the tyrosine-protein kinase (KIT) or platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA) gene mutations found in most adults.9 About 80% of these cases have hereditary mutations of the succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) enzyme complex. Because some adult cases of GIST share the distinct characteristics found in most pediatric cases, distinguishing them based on age, rather than on the specific genetic characteristics of the tumor, is unwarranted.9

How?

When GIST is suspected or when symptoms mandate further investigation, coordination among colleagues in imaging, gastroenterology, pathology, surgery, and oncology is critical for accurate diagnosis, staging, and treatment. Abdominal imaging may be ordered using modalities such as ultrasound, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and, occasionally, positron emission tomography.11 Endoscopic ultrasound is useful to identify and biopsy lesions in the stomach or rectum, as these tumors arise below the lining of the stomach or rectum. GIST diagnosis can be confirmed by biopsy during endoscopic ultrasound, which is the preferred approach, or by percutaneous biopsy when endoscopic biopsy is not feasible or safe.11

According to the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) and European Reference Group for Rare Adult Solid Cancers (EURACAN) Clinical Practice Guidelines, the “standard approach to tumors ≥ 2 cm in size is excision, because they are associated with a higher risk of progression if confirmed as GIST. If there is an abdominal nodule not amenable to endoscopic assessment, laparoscopic or laparotomic excision is the standard approach.”11

Genetic Mutations

A diagnosis of GIST is made based on the combination of the clinical scenario, the tumor’s anatomic location, immunohistochemistry patterns, and molecular features.12 Research has shown that genetic mutations in the KIT, PDGFRA, or SDH genes are present in most cases of GIST (70-80%,13 10%,12 and less than 10% of cases12,14 respectively) and their presence can be used for diagnosis. A growing number of rarer mutations have also been discovered,13 meaning that gene-based diagnosis of GIST is becoming increasingly sensitive. In addition, antigens on the surface of cancer cells can help classify them as GIST. For example, researchers have discovered that most GIST cells have the marker CD117, the protein product of the KIT gene that is commonly mutated in GIST, on their surfaces. A different marker, DOG1 (ie, Discovered On GIST 1), is also present on the vast majority of GISTs, but not unanimously overlapping with CD117. A tumor that is positive for both CD117 and DOG1 has a high probability (> 97%) of being GIST.15

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) is considered the best tool for determining both germline and somatic mutations in patients with GIST, and NGS is recommended by both the NCCN6 and the ESMO11 for individualizing systemic therapy. Despite these recommendations, most patients do not undergo genetic testing, both in the United States16 and internationally.17 Several barriers to genetic testing have been cited, predominately inadequate tissue and high cost. However, a study demonstrated that costs of up to $3,730 for genetic testing were ultimately cost-effective for tailoring therapy with first-line imatinib for patients with newly diagnosed metastatic GIST.18 Moreover, genetic testing also should be strongly considered for patients with nonmetastatic disease in whom systemic therapy is being considered.

Increasing evidence has emerged that gastric GIST mutations are related to tumor location within the gastrointestinal tract (Figure).7 The anatomic location of the GIST may provide clues for clinical decision-making and may guide selective confirmatory genomic testing when access to testing is limited.

Treatment of GIST

Surgery

Surgery remains the main treatment for localized GIST, especially if the tumor is discovered at an early stage. Unfortunately, up to a quarter of patients present with metastatic disease at diagnosis. The goal of surgery is to resect the tumor with histologically negative margins. Every effort should be made to avoid rupturing the tumor capsule during resection. Studies have shown that laparoscopic resection is feasible and safe for gastric GISTs and is less invasive than traditional open surgery, with similar oncological outcomes.19

Debulking surgery is sometimes considered for patients with metastatic disease, especially for patients who demonstrate sensitivity to TKI and whose disease has not yet progressed.20,21 Other interventions, such as microwave ablation or transhepatic arterial embolization, are sometimes used to control hepatic metastases.

Systemic Therapies

Whether systemic therapy is being considered in the neoadjuvant (preoperative), adjuvant (postoperative), or advanced disease setting, mutations in GIST determine the likelihood of treatment success. Both NCCN6 and ESMO11 strongly encourage use of mutational analyses and genetic testing for patients with GIST before systemic therapy is initiated.

In some cases of locally advanced GIST, tumors may be situated in particularly challenging anatomic locations(eg, esophagus, duodenum, rectum) or may require a highly morbid, multivisceral resection. In such situations, neoadjuvant treatment with imatinib,22,23 if deemed appropriate per mutational profiling, should be considered.

Patients who are determined to be at high risk for recurrence after surgery, based on tumor size, mitotic index determined by pathologist review of dividing cells, tumor location, and tumor rupture, may be eligible for adjuvant treatment with imatinib.24 Although the ideal duration of adjuvant therapy is not yet known, the current standard is at least 3 years,25 but many practitioners advocate for lifelong therapy.

Imatinib. Because chemotherapy was ineffective against GIST, prognosis was dismal for patients diagnosed with advanced disease before the approval of imatinib in the early 2000s.2 A selective TKI, imatinib targets the KIT and PDGFRA receptor kinases, and most patients experience clinical benefit,26 at least initially. Unfortunately, many tumors eventually develop resistance, and discontinuation of imatinib is associated with a risk for disease progression.27

Sunitinib. The emergence of resistance to imatinib spurred the search for second-line agents that might be useful after disease progression. Another TKI, sunitinib, which has both antitumor and antiangiogenic activity, was approved in 2006 for management of advanced imatinib-resistant GIST.28 Knowledge of a tumor’s driver mutation(s) can help optimize use of sunitinib.29

Regorafenib. In 2013, the FDA approved regorafenib, another TKI, as a third-line agent for patients with advanced GIST that is refractory to imatinib and sunitinib.30 Regorafenib exerts its activity against multiple targets, including VEGFR1-3, TIE2 (ie, antiangiogenic activity), PDGFR-β, FGFR (ie, stromal targets), and KIT, RET, and RAF (ie, oncogenic targets). As with other TKIs, common adverse effects associated with regorafenib treatment include hypertension, hand-foot skin reaction, rash, diarrhea, and fatigue.

Larotrectinib/entrectinib. The FDA approved larotrectinib31 (2018) and entrectinib32 (2019) as the first tumor-agnostic agents, whose use is based on the presence of specific genomic alteration, in this case NTRK. If a tumor, including a GIST, harbors a specific, albeit rare, gene fusion, it may be considered for treatment with one of these small-molecule TRK family inhibitors. Although these agents are not specifically indicated for GIST, some subjects enrolled in the trials had GIST harboring the target NTRK gene fusion and their tumors responded to treatment.

Ripretinib. FDA-approved in 2020,33 ripretinib is a novel TKI indicated for adult patients with advanced GIST who have received prior treatment with 3 or more kinase inhibitors, including imatinib. A phase 3 trial demonstrated improved progression-free and overall survival when ripretinib was compared with placebo in patients who had disease progression after treatment with imatinib, sunitinib, or regorafenib.34 Ripretinib is now being investigated in the second-line setting in selected patients with KIT mutations.

Avapritinib. Cases of GIST with PDGFRA D842V-mutant tumors often demonstrate primary resistance to imatinib and sunitinib. In 2020, avapritinib, a selective TKI that targets both KIT and PDGFRA, was approved35 for treatment of patients with unresectable or metastatic GIST harboring a PDGFRA exon 18 mutation, including D842V mutations. However, it is noteworthy that many of the non-D842V mutations in PDGFRA respond to imatinib.

Dabrafenib/trametinib. In 2022, the FDA issued an approval for treatment based on a driver mutation rather than tumor type. Acknowledging that a BRAF mutation—specifically a V600E mutation—appears to be a critical target in several cancers, the FDA granted accelerated approval for the use of dabrafenib plus trametinib in adults and children 6 years of age and older with unresectable or metastatic solid tumors with BRAF V600E mutation who have progressed following prior treatment and have no satisfactory alternative treatment options.36

Researchers have studied additional TKIs in the setting of unresectable, metastatic disease due to the varied genomic landscape of GIST. The NCCN Guidelines include evidence of some benefit for agents such as dasatinib, cabozantinib, everolimus (plus a TKI), nilotinib, pazopanib, and sorafenib “in certain circumstances.”6

The Future of GIST

The most critical step toward optimal treatment decision-making when a patient has been diagnosed with GIST is identification of physicians with expertise in the care of patients with GIST. With increasing knowledge of genomic variations in GIST, patient care has become less prescripted and much more personalized. To that end, determination of the tumor’s genetic mutational profile is critical to guiding treatment. Although factors such as cost, availability/accessibility, and insufficient tissue continue to represent substantial obstacles, pursing this information may be the most important way that clinicians can advocate for their patients. Moreover, now that the anatomic location of GIST has been linked to specific driver mutations, the ability to select and refine treatments may improve significantly.

Likewise, in view of the increasing complexity and multidisciplinary management of patients with GIST, efficient coordination is paramount among surgical and medical oncologists, as well as radiologists, gastroenterologists, and pathologists.

Since the early 2000s, new discoveries about GIST genomics have contributed to better, more targeted treatments. Some genomic mutations have been linked to specific gut regions,7 which may further help guide therapy as well.

GIST: What Is It, Who Gets It, and How Is It Diagnosed?

What, How Many, Where?

Even though GIST is considered rare—representing less than 1% of gastrointestinal tumors8—it is the most common sarcoma, which is a family of mesenchymal neoplasms. GISTs are thought to arise from the interstitial cells of Cajal, or the pacemaker cells of the gut that control peristalsis. In the United States, the incidence of GIST is roughly 4,000 to 6,000 new cases diagnosed per year, with most cases found in the stomach (60%) or small intestine (35%). Other gut regions in which GISTs may be identified include the rectum and esophagus.8

Although asymptomatic tumors are often discovered incidentally, GISTs that originate in the stomach—the most common primary tumor site—may present with nonspecific subjective symptoms such as pain, nausea, loss of appetite, early satiety, or bloating.9 Symptoms may vary according to tumor location (eg, stomach vs rectum vs esophagus), size, and pattern of growth. More objective signs could include anemia related to gastrointestinal bleeding, weight loss, or a palpable mass.9

Who?

Most cases of GIST occur in patients later in life, with a median age of 64 years at diagnosis. A slight predominance of men has been noted, along with African American and Asian individuals affected somewhat more frequently than White or Hispanic populations.10 GIST is rare in children and adolescents, and the symptoms and pathology differ from those in most adults.9 Previously age was considered a determining factor in the differences in GIST, with cases in children classified as “pediatric-type” GIST or “wild-type” GIST. These cases generally present in the stomach, are more likely to include lymph node involvement, and can also spread to the liver and abdominal lining. Importantly, they are usually not associated with the tyrosine-protein kinase (KIT) or platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA) gene mutations found in most adults.9 About 80% of these cases have hereditary mutations of the succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) enzyme complex. Because some adult cases of GIST share the distinct characteristics found in most pediatric cases, distinguishing them based on age, rather than on the specific genetic characteristics of the tumor, is unwarranted.9

How?

When GIST is suspected or when symptoms mandate further investigation, coordination among colleagues in imaging, gastroenterology, pathology, surgery, and oncology is critical for accurate diagnosis, staging, and treatment. Abdominal imaging may be ordered using modalities such as ultrasound, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and, occasionally, positron emission tomography.11 Endoscopic ultrasound is useful to identify and biopsy lesions in the stomach or rectum, as these tumors arise below the lining of the stomach or rectum. GIST diagnosis can be confirmed by biopsy during endoscopic ultrasound, which is the preferred approach, or by percutaneous biopsy when endoscopic biopsy is not feasible or safe.11

According to the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) and European Reference Group for Rare Adult Solid Cancers (EURACAN) Clinical Practice Guidelines, the “standard approach to tumors ≥ 2 cm in size is excision, because they are associated with a higher risk of progression if confirmed as GIST. If there is an abdominal nodule not amenable to endoscopic assessment, laparoscopic or laparotomic excision is the standard approach.”11

Genetic Mutations

A diagnosis of GIST is made based on the combination of the clinical scenario, the tumor’s anatomic location, immunohistochemistry patterns, and molecular features.12 Research has shown that genetic mutations in the KIT, PDGFRA, or SDH genes are present in most cases of GIST (70-80%,13 10%,12 and less than 10% of cases12,14 respectively) and their presence can be used for diagnosis. A growing number of rarer mutations have also been discovered,13 meaning that gene-based diagnosis of GIST is becoming increasingly sensitive. In addition, antigens on the surface of cancer cells can help classify them as GIST. For example, researchers have discovered that most GIST cells have the marker CD117, the protein product of the KIT gene that is commonly mutated in GIST, on their surfaces. A different marker, DOG1 (ie, Discovered On GIST 1), is also present on the vast majority of GISTs, but not unanimously overlapping with CD117. A tumor that is positive for both CD117 and DOG1 has a high probability (> 97%) of being GIST.15

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) is considered the best tool for determining both germline and somatic mutations in patients with GIST, and NGS is recommended by both the NCCN6 and the ESMO11 for individualizing systemic therapy. Despite these recommendations, most patients do not undergo genetic testing, both in the United States16 and internationally.17 Several barriers to genetic testing have been cited, predominately inadequate tissue and high cost. However, a study demonstrated that costs of up to $3,730 for genetic testing were ultimately cost-effective for tailoring therapy with first-line imatinib for patients with newly diagnosed metastatic GIST.18 Moreover, genetic testing also should be strongly considered for patients with nonmetastatic disease in whom systemic therapy is being considered.

Increasing evidence has emerged that gastric GIST mutations are related to tumor location within the gastrointestinal tract (Figure).7 The anatomic location of the GIST may provide clues for clinical decision-making and may guide selective confirmatory genomic testing when access to testing is limited.

Treatment of GIST

Surgery

Surgery remains the main treatment for localized GIST, especially if the tumor is discovered at an early stage. Unfortunately, up to a quarter of patients present with metastatic disease at diagnosis. The goal of surgery is to resect the tumor with histologically negative margins. Every effort should be made to avoid rupturing the tumor capsule during resection. Studies have shown that laparoscopic resection is feasible and safe for gastric GISTs and is less invasive than traditional open surgery, with similar oncological outcomes.19

Debulking surgery is sometimes considered for patients with metastatic disease, especially for patients who demonstrate sensitivity to TKI and whose disease has not yet progressed.20,21 Other interventions, such as microwave ablation or transhepatic arterial embolization, are sometimes used to control hepatic metastases.

Systemic Therapies

Whether systemic therapy is being considered in the neoadjuvant (preoperative), adjuvant (postoperative), or advanced disease setting, mutations in GIST determine the likelihood of treatment success. Both NCCN6 and ESMO11 strongly encourage use of mutational analyses and genetic testing for patients with GIST before systemic therapy is initiated.

In some cases of locally advanced GIST, tumors may be situated in particularly challenging anatomic locations(eg, esophagus, duodenum, rectum) or may require a highly morbid, multivisceral resection. In such situations, neoadjuvant treatment with imatinib,22,23 if deemed appropriate per mutational profiling, should be considered.

Patients who are determined to be at high risk for recurrence after surgery, based on tumor size, mitotic index determined by pathologist review of dividing cells, tumor location, and tumor rupture, may be eligible for adjuvant treatment with imatinib.24 Although the ideal duration of adjuvant therapy is not yet known, the current standard is at least 3 years,25 but many practitioners advocate for lifelong therapy.

Imatinib. Because chemotherapy was ineffective against GIST, prognosis was dismal for patients diagnosed with advanced disease before the approval of imatinib in the early 2000s.2 A selective TKI, imatinib targets the KIT and PDGFRA receptor kinases, and most patients experience clinical benefit,26 at least initially. Unfortunately, many tumors eventually develop resistance, and discontinuation of imatinib is associated with a risk for disease progression.27

Sunitinib. The emergence of resistance to imatinib spurred the search for second-line agents that might be useful after disease progression. Another TKI, sunitinib, which has both antitumor and antiangiogenic activity, was approved in 2006 for management of advanced imatinib-resistant GIST.28 Knowledge of a tumor’s driver mutation(s) can help optimize use of sunitinib.29

Regorafenib. In 2013, the FDA approved regorafenib, another TKI, as a third-line agent for patients with advanced GIST that is refractory to imatinib and sunitinib.30 Regorafenib exerts its activity against multiple targets, including VEGFR1-3, TIE2 (ie, antiangiogenic activity), PDGFR-β, FGFR (ie, stromal targets), and KIT, RET, and RAF (ie, oncogenic targets). As with other TKIs, common adverse effects associated with regorafenib treatment include hypertension, hand-foot skin reaction, rash, diarrhea, and fatigue.

Larotrectinib/entrectinib. The FDA approved larotrectinib31 (2018) and entrectinib32 (2019) as the first tumor-agnostic agents, whose use is based on the presence of specific genomic alteration, in this case NTRK. If a tumor, including a GIST, harbors a specific, albeit rare, gene fusion, it may be considered for treatment with one of these small-molecule TRK family inhibitors. Although these agents are not specifically indicated for GIST, some subjects enrolled in the trials had GIST harboring the target NTRK gene fusion and their tumors responded to treatment.

Ripretinib. FDA-approved in 2020,33 ripretinib is a novel TKI indicated for adult patients with advanced GIST who have received prior treatment with 3 or more kinase inhibitors, including imatinib. A phase 3 trial demonstrated improved progression-free and overall survival when ripretinib was compared with placebo in patients who had disease progression after treatment with imatinib, sunitinib, or regorafenib.34 Ripretinib is now being investigated in the second-line setting in selected patients with KIT mutations.

Avapritinib. Cases of GIST with PDGFRA D842V-mutant tumors often demonstrate primary resistance to imatinib and sunitinib. In 2020, avapritinib, a selective TKI that targets both KIT and PDGFRA, was approved35 for treatment of patients with unresectable or metastatic GIST harboring a PDGFRA exon 18 mutation, including D842V mutations. However, it is noteworthy that many of the non-D842V mutations in PDGFRA respond to imatinib.

Dabrafenib/trametinib. In 2022, the FDA issued an approval for treatment based on a driver mutation rather than tumor type. Acknowledging that a BRAF mutation—specifically a V600E mutation—appears to be a critical target in several cancers, the FDA granted accelerated approval for the use of dabrafenib plus trametinib in adults and children 6 years of age and older with unresectable or metastatic solid tumors with BRAF V600E mutation who have progressed following prior treatment and have no satisfactory alternative treatment options.36

Researchers have studied additional TKIs in the setting of unresectable, metastatic disease due to the varied genomic landscape of GIST. The NCCN Guidelines include evidence of some benefit for agents such as dasatinib, cabozantinib, everolimus (plus a TKI), nilotinib, pazopanib, and sorafenib “in certain circumstances.”6

The Future of GIST

The most critical step toward optimal treatment decision-making when a patient has been diagnosed with GIST is identification of physicians with expertise in the care of patients with GIST. With increasing knowledge of genomic variations in GIST, patient care has become less prescripted and much more personalized. To that end, determination of the tumor’s genetic mutational profile is critical to guiding treatment. Although factors such as cost, availability/accessibility, and insufficient tissue continue to represent substantial obstacles, pursing this information may be the most important way that clinicians can advocate for their patients. Moreover, now that the anatomic location of GIST has been linked to specific driver mutations, the ability to select and refine treatments may improve significantly.

Likewise, in view of the increasing complexity and multidisciplinary management of patients with GIST, efficient coordination is paramount among surgical and medical oncologists, as well as radiologists, gastroenterologists, and pathologists.

- Miettinen M, Virolainen M, Maarit-Sarlomo-Rikala. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors—value of CD34 antigen in their identification and separation from true leiomyomas and schwannomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19(2):207-216. doi:10.1097/00000478-199502000-00009

- Dagher R, Cohen M, Williams G, et al. Approval summary: imatinib mesylate in the treatment of metastatic and/or unresectable malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(10):3034-3038. PMID:12374669

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves larotrectinib for solid tumors with NTRK gene fusions [press release]. Published November 26, 2018. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/fda-approves-larotrectinib-solid-tumors-ntrk-gene-fusions

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves entrectinib for NTRK solid tumors and ROS-1 NSCLC [press release]. Published August 15, 2019. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-entrectinib-ntrk-solid-tumors-and-ros-1-nsclc

- Winstead W. Dabrafenib-trametinib combination approved for solid tumors with BRAF mutations. National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. Published July 21, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2022/fda-dabrafenib-trametinib-braf-solid-tumors

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinic practice guidelines in oncology: gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Version 1.2023. March 13, 2023. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/gist.pdf

- Sharma AK, de la Torre J, IJzerman NS, et al. Location of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) in the stomach predicts tumor mutation profile and drug sensitivity. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(19):5334-5342. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-1221

- Gastrointestinal stromal tumor—GIST: statistics. Cancer.net. Published March 2023. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/gastrointestinal-stromal-tumor-gist/statistics

- Sicklick J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors - symptoms, causes, treatment: NORD. National Organization for Rare Disorders. Published January 12, 2023. Accessed March 28, 2023. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/gastrointestinal-stromal-tumors/

- Ma GL, Murphy JD, Martinez ME, Sicklick JK. Epidemiology of gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the era of histology codes: results of a population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;24(1):298-302. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-1002

- Casali PG, Abecassis N, Aro HT, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMOEURACAN Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(suppl 4):iv68-iv78. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdy095

- Kelly CM, Sainz LG, Chi P. The management of metastatic GIST: current standard and investigational therapeutics. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14(1):2. doi:10.1186/s13045-020-01026-6

- Shi E, Chmielecki J, Tang CM, et al. FGR1 and NTRK3 actionable alterations in “wild-type” gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Translat Med. 2016;14(1):339. doi:10.1186/s12967-016-1075-6

- Bannon AE, Klug LR, Corless CL, Heinrich MC. Using molecular diagnostic testing to personalize the treatment of patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2017;17(5):445-457. doi:10.1080/14737159.2017.1308826

- Wu CE, Tzen CY, Wang SY, Yeh CN. Clinical diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST): from the molecular genetic point of view. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(5):679. doi:10.3390/cancers11050679

- Florindez J, Trent J. Low frequency of mutation testing in the United States: an analysis of 3866 GIST patients. Am J Clin Oncol. 2020;43(4):270-278. doi:10.1097/COC.0000000000000659

- Verschoor AJ, Bovée JVMG, Overbeek LIH, PALGA group; Hogendoorn PCW, Gelderblom H. The incidence, mutational status, risk classification and referral pattern of gastrointestinal stromal tumours in the Netherlands: a nationwide pathology registry (PALGA) study. Virchows Arch. 2018;472(2):221-229. doi:10.1007/s00428-017-2285-x

- Banerjee S, Kumar A, Lopez N, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of genetic testing and tailored first-line therapy for patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2013565. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.1356519

- Chen K, Zhou YC, Mou YP, Xu XW, Jin WW, Ajoodhea H. Systematic review and meta-analysis of safety and efficacy of laparoscopic resection of gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:355-367. doi:10.1007/s00464-014-3676-6

- Fairweather M, Balachandran VP, Li GZ, et al. Cytoreductive surgery for metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: a 2-institutional analysis. Ann Surg. 2018;268(2):296-302. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000002281

- Bauer S, Rutkowski P, Hohenberger P, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with GIST undergoing metastasectomy in the era of imatinib—analysis of prognostic factors (EORTC-STBSG collaborative study). Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40(4):412-419. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2013.12.020

- Rutkowski P, Gronchi A, Hohenberger P, et al. Neoadjuvant imatinib in locally advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST): the EORTC STBSG experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(9):2937-2943. doi:10.1245/s10434-013-3013-7

- Cavnar MJ, Seier K, Gönen M, et al. Prognostic factors after neoadjuvant imatinib for newly diagnosed primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Gastrointest Surg. 2021;25(7):1828-1836. doi:10.1007/s11605-020-04843-9

- Joensuu H. Risk stratification of patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Hum Pathol. 2008;39(10):1411-1419. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2008.06.025

- Joensuu H, Eriksson M, Sundby Hall K, et al. Survival outcomes associated with 3 years vs 1 year of adjuvant imatinib for patients with high-risk gastrointestinal stromal tumors: an analysis of a randomized clinical trial after 10-year follow-up. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(8):1241-1246. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.2091

- Heinrich MC, Rankin C, Blanke CD, et al. Correlation of long-term results of imatinib in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors with next-generation sequencing results: analysis of phase 3 SWOG Intergroup Trial S0033. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(7):944-952. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6728

- Le Cesne A, Ray-Coquard I, Bui BN, et al. Discontinuation of imatinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumours after 3 years of treatment: an open-label multicentre randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;11(10):942-949. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70222-9

- Demetri GD, van Oosterom AT, Garrett CR, et al. Efficacy and safety of sunitinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumour after failure of imatinib: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;368(9544):1329-1338. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69446-4

- Heinrich MC, Maki RG, Corless CL, et al. Primary and secondary kinase genotypes correlate with the biological and clinical activity of sunitinib in imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(33):5352-5359. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.15.7461

- Crona DJ, Keisler MD, Walko CM. Regorafenib: a novel multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor for colorectal and gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(12):1685-1696. doi:10.1177/1060028013509792

- Drilon A, Laetsch TW, Kummar S, et al. Efficacy of larotrectinib in TRK fusion-positive cancers in adults and children. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(8):731-739. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1714448

- Doebele RC, Drilon A, Paz-Ares L, et al. Entrectinib in patients with advanced or metastatic NTRK fusion-positive solid tumours: integrated analysis of three phase 1-2 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(2):271-282. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30691-6

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves ripretinib for advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor [press release]. Published May 15, 2020. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-ripretinib-advanced-gastrointestinal-stromal-tumor

- Blay JY, Serrano C, Heinrich MC, et al. Ripretinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumours (INVICTUS): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(7):923-934. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30168-6

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves avapritinib for gastrointestinal stromal tumor with a rare mutation [press release]. Published January 9, 2020. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-avapritinib-gastrointestinal-stromal-tumor-rare-mutation

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA grants accelerated approval to dabrafenib in combination with trametinib for unresectable or metastatic solid tumors with BRAF V600E mutation [press release]. Published June 22, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-dabrafenib-combination-trametinib-unresectable-or-metastatic-solid

- Miettinen M, Virolainen M, Maarit-Sarlomo-Rikala. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors—value of CD34 antigen in their identification and separation from true leiomyomas and schwannomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19(2):207-216. doi:10.1097/00000478-199502000-00009

- Dagher R, Cohen M, Williams G, et al. Approval summary: imatinib mesylate in the treatment of metastatic and/or unresectable malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(10):3034-3038. PMID:12374669

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves larotrectinib for solid tumors with NTRK gene fusions [press release]. Published November 26, 2018. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/fda-approves-larotrectinib-solid-tumors-ntrk-gene-fusions

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves entrectinib for NTRK solid tumors and ROS-1 NSCLC [press release]. Published August 15, 2019. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-entrectinib-ntrk-solid-tumors-and-ros-1-nsclc

- Winstead W. Dabrafenib-trametinib combination approved for solid tumors with BRAF mutations. National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. Published July 21, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2022/fda-dabrafenib-trametinib-braf-solid-tumors

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinic practice guidelines in oncology: gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Version 1.2023. March 13, 2023. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/gist.pdf

- Sharma AK, de la Torre J, IJzerman NS, et al. Location of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) in the stomach predicts tumor mutation profile and drug sensitivity. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(19):5334-5342. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-1221

- Gastrointestinal stromal tumor—GIST: statistics. Cancer.net. Published March 2023. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/gastrointestinal-stromal-tumor-gist/statistics

- Sicklick J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors - symptoms, causes, treatment: NORD. National Organization for Rare Disorders. Published January 12, 2023. Accessed March 28, 2023. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/gastrointestinal-stromal-tumors/

- Ma GL, Murphy JD, Martinez ME, Sicklick JK. Epidemiology of gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the era of histology codes: results of a population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;24(1):298-302. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-1002

- Casali PG, Abecassis N, Aro HT, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMOEURACAN Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(suppl 4):iv68-iv78. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdy095

- Kelly CM, Sainz LG, Chi P. The management of metastatic GIST: current standard and investigational therapeutics. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14(1):2. doi:10.1186/s13045-020-01026-6

- Shi E, Chmielecki J, Tang CM, et al. FGR1 and NTRK3 actionable alterations in “wild-type” gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Translat Med. 2016;14(1):339. doi:10.1186/s12967-016-1075-6

- Bannon AE, Klug LR, Corless CL, Heinrich MC. Using molecular diagnostic testing to personalize the treatment of patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2017;17(5):445-457. doi:10.1080/14737159.2017.1308826

- Wu CE, Tzen CY, Wang SY, Yeh CN. Clinical diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST): from the molecular genetic point of view. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(5):679. doi:10.3390/cancers11050679

- Florindez J, Trent J. Low frequency of mutation testing in the United States: an analysis of 3866 GIST patients. Am J Clin Oncol. 2020;43(4):270-278. doi:10.1097/COC.0000000000000659

- Verschoor AJ, Bovée JVMG, Overbeek LIH, PALGA group; Hogendoorn PCW, Gelderblom H. The incidence, mutational status, risk classification and referral pattern of gastrointestinal stromal tumours in the Netherlands: a nationwide pathology registry (PALGA) study. Virchows Arch. 2018;472(2):221-229. doi:10.1007/s00428-017-2285-x

- Banerjee S, Kumar A, Lopez N, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of genetic testing and tailored first-line therapy for patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2013565. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.1356519

- Chen K, Zhou YC, Mou YP, Xu XW, Jin WW, Ajoodhea H. Systematic review and meta-analysis of safety and efficacy of laparoscopic resection of gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:355-367. doi:10.1007/s00464-014-3676-6

- Fairweather M, Balachandran VP, Li GZ, et al. Cytoreductive surgery for metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: a 2-institutional analysis. Ann Surg. 2018;268(2):296-302. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000002281

- Bauer S, Rutkowski P, Hohenberger P, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with GIST undergoing metastasectomy in the era of imatinib—analysis of prognostic factors (EORTC-STBSG collaborative study). Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40(4):412-419. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2013.12.020

- Rutkowski P, Gronchi A, Hohenberger P, et al. Neoadjuvant imatinib in locally advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST): the EORTC STBSG experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(9):2937-2943. doi:10.1245/s10434-013-3013-7

- Cavnar MJ, Seier K, Gönen M, et al. Prognostic factors after neoadjuvant imatinib for newly diagnosed primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Gastrointest Surg. 2021;25(7):1828-1836. doi:10.1007/s11605-020-04843-9

- Joensuu H. Risk stratification of patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Hum Pathol. 2008;39(10):1411-1419. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2008.06.025

- Joensuu H, Eriksson M, Sundby Hall K, et al. Survival outcomes associated with 3 years vs 1 year of adjuvant imatinib for patients with high-risk gastrointestinal stromal tumors: an analysis of a randomized clinical trial after 10-year follow-up. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(8):1241-1246. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.2091

- Heinrich MC, Rankin C, Blanke CD, et al. Correlation of long-term results of imatinib in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors with next-generation sequencing results: analysis of phase 3 SWOG Intergroup Trial S0033. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(7):944-952. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6728

- Le Cesne A, Ray-Coquard I, Bui BN, et al. Discontinuation of imatinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumours after 3 years of treatment: an open-label multicentre randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;11(10):942-949. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70222-9

- Demetri GD, van Oosterom AT, Garrett CR, et al. Efficacy and safety of sunitinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumour after failure of imatinib: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;368(9544):1329-1338. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69446-4

- Heinrich MC, Maki RG, Corless CL, et al. Primary and secondary kinase genotypes correlate with the biological and clinical activity of sunitinib in imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(33):5352-5359. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.15.7461

- Crona DJ, Keisler MD, Walko CM. Regorafenib: a novel multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor for colorectal and gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(12):1685-1696. doi:10.1177/1060028013509792

- Drilon A, Laetsch TW, Kummar S, et al. Efficacy of larotrectinib in TRK fusion-positive cancers in adults and children. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(8):731-739. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1714448

- Doebele RC, Drilon A, Paz-Ares L, et al. Entrectinib in patients with advanced or metastatic NTRK fusion-positive solid tumours: integrated analysis of three phase 1-2 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(2):271-282. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30691-6

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves ripretinib for advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor [press release]. Published May 15, 2020. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-ripretinib-advanced-gastrointestinal-stromal-tumor

- Blay JY, Serrano C, Heinrich MC, et al. Ripretinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumours (INVICTUS): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(7):923-934. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30168-6

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves avapritinib for gastrointestinal stromal tumor with a rare mutation [press release]. Published January 9, 2020. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-avapritinib-gastrointestinal-stromal-tumor-rare-mutation

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA grants accelerated approval to dabrafenib in combination with trametinib for unresectable or metastatic solid tumors with BRAF V600E mutation [press release]. Published June 22, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-dabrafenib-combination-trametinib-unresectable-or-metastatic-solid