User login

Implementation and Impact of a β -Lactam Allergy Assessment Protocol in a Veteran Population

Allergies to β-lactam antibiotics are among the most documented drug allergies, and approximately 10% of the US population reports an allergy specifically to penicillin.1,2 Many allergic reactions are mediated via the antibody immunoglobulin E (IgE), producing an immediate hypersensitivity response, such as hives or anaphylaxis, which can be life threatening. Reactions also may be mediated by T cells of the immune system, which target various cell lines and can cause a drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms or Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN).3Although β-lactam and penicillin allergies are frequently reported, < 5% manifest as either an IgE or T-cell–mediated response.4Furthermore, for the small proportion of patients who once had a true IgE-mediated reaction, including anaphylaxis, 80% experience a decrease in IgE antibodies over time, resulting in a loss of allergic response after about 10 years.2 Due to this decline in IgE response and the initial mislabeling of mild non-IgE penicillin reactions, 95% of patients who are labeled as penicillin-allergic can eventually tolerate a penicillin.2

When a patient’s β-lactam allergy is never reevaluated, negative consequences can ensue. This allergy in a patient’s medical record can lead to the inappropriate avoidance of the entire β-lactam antibiotic class, which includes all penicillins, cephalosporins, and carbapenems. Withholding these antibiotics in certain situations can lead to negative patient outcomes.5-7 For example, the drugs of choice for the infections syphilis and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (S aureus) are a penicillin or cephalosporin, and patients labeled as penicillin-allergic are more likely to experience treatment failure from using second-line therapies.8 Additionally, receiving non-β-lactam antibiotics puts patients at risk of multidrug-resistant pathogens like methicillin-resistant S aureus and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) as well as adverse effects, such as Clostridioides difficile infection.9 Using alternative, and likely broad-spectrum, antibiotics also can be financially detrimental: These medications often are more costly than their β-lactam alternatives, and the inappropriate use of therapies can result in longer hospital courses.9-11

Penicillin allergies can complicate the antibiotic treatment strategy. The Memphis Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MVAMC) in Tennessee recently examined the negative sequelae of β-lactam allergies and found that more than half the patients received inappropriate antibiotics based on guideline recommendations, allergy history, and culture and sensitivity data.12 To mitigate the problems for patients with β-lactam allergies, the 2016 guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) on the Implementation of Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs (ASP) recommend that these patients undergo allergy assessment and penicillin skin testing.13In November 2017, MVAMC implemented such a process. The purpose of this study was to describe our pharmacist-run β-lactam allergy assessment (BLAA) protocol and penicillin allergy clinic (PAC) and evaluate their overall outcomes: the proportion of patients who have been cleared to receive an alternative β-lactam antibiotic or who have had their allergy removed altogether.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective, observational study with approval from the institutional review board at MVAMC. This institution is an academic teaching center with 240 acute care beds and a variety of outpatient clinics available at the main campus, serving veterans in Memphis and the Mid-South area, including west Tennessee, northern Mississippi, and northeastern Arkansas. Patients were consecutively evaluated from November 2017 through February 2020. All MVAMC patients with a documented β-lactam allergy were eligible for inclusion; there were no exclusion criteria. Electronic health record data were assessed and included basic patient demographics, allergy history, and the outcome of the BLAA and PAC. Descriptive statistics were used for data analysis.

The purpose of the BLAA process is to evaluate, clarify, and potentially clear patients of their β-lactam allergies. Started in November 2017, the process includes appropriate patient screening with documentation of the β-lactam allergy. When patients with a β-lactam allergy are admitted to the hospital, they are interviewed by an inpatient CPS. This pharmacist then enters an assessment into the patient’s chart, which includes details of the allergen, reaction, and timing of the event. Based on this information, the CPS provides recommendations: clearance for alternative β-lactams, avoidance of all β-lactams, or removal of the allergy.

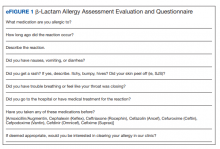

In January 2019, the pharmacist-driven penicillin allergy clinic (PAC) was started. Eligible patients receive a skin test to confirm or rule out their allergy after hospital discharge. To facilitate patient identification and screening, the ASP/infectious diseases (ID) clinical pharmacist runs a daily report of hospitalized patients with documented β-lactam allergies. All inpatient CPSs had access to this report and could easily identify and interview patients. Following the interview, the pharmacist enters a note in the patient’s chart, using the BLAA template (eFigures 1 and 2). On completion, a note is viewable in the Notes section adjacent to the patient’s allergies. The pharmacist then can enter a PAC consult for eligible patients. Although most patients qualify for PAC, exclusion criteria include non–IgE-mediated allergies (ie, SJS/TEN), allergies to β-lactams other than penicillins, or recent reactions (ie, within the past 5 years). Each inpatient CPS is trained on this BLAA process, which includes patient screening, chart review, patient interviewing, and the BLAA template and note completion. Pharmacists must demonstrate competency in completing 5 BLAA notes with review from the ASP/ID pharmacist. Once training is completed, this process is integrated into the pharmacist’s everyday workflow.

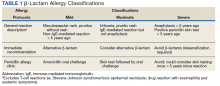

On receipt of the PAC consult, the ASP/ID pharmacist reviews the patient chart to further assess for eligibility and to determine whether oral challenge alone or skin testing followed by the oral challenge is required based on patient risk stratification (Table 1).3Relative contraindications to PAC include severe or unstable lung disease that requires home oxygen, frequent or recurrent heart failure exacerbations, or patients with acute or unstable cardiopulmonary, neurologic, or mental health conditions. These scenarios are discussed case by case with the allergy/immunology (A/I) physician.

The ASP/ID pharmacist also reviews the patient’s chart for medications that may blunt the histamine response during drug testing. The need to hold these medications before PAC also are individually assessed in conjunction with the A/I physician. The ASP/ID pharmacist and 3 other CPS involved in the creation of the BLAA and PAC have received formal hands-on training on penicillin allergy testing. The PAC process consists of a penicillin skin test, followed by the amoxicillin oral challenge.3The ASP/ID clinical pharmacist who is trained in penicillin skin testing performs all duties in PAC, with oversight from the A/I attending physician as needed. Currently, the ASP/ID pharmacist runs the PAC once a week with the A/I physician available if needed. Along with documenting an A/I clinic note detailing the events of PAC, the ASP/ID pharmacist also will add an addendum to the original BLAA note. If the allergy is removed through direct testing, it also can be removed from the patient’s profile after discussion with the A/I physician. Therefore, the full details necessary to evaluate, clarify, and clear the patient of their β-lactam allergy are in one place.

Results

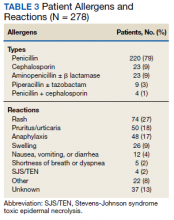

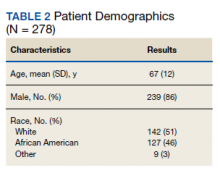

We evaluated 278 patients, using the BLAA protocol. In this veteran population, patients were generally older males and evenly split between African American and White patients (Table 2). Most patients reported an allergy to penicillin, with a rash being the most common reaction (Table 3).

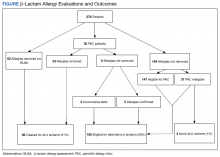

Of the 278 assessed, 246 patients were evaluated via our BLAA alone and were not seen in PAC. We were able to remove 25% of these patients’ allergies by performing a thorough assessment. Of the 184 patients whose allergies could not be removed via the BLAA alone, 147 (80%) were still eligible for PAC but are awaiting scheduling. Patients ineligible for PAC included those with a cephalosporin allergy or a severe and non–IgE-mediated reaction. Other ineligible patients who were not eligible included those with diseases where risk of testing outweighed the benefits.

Of the 32 patients who were seen in PAC, 75% of allergies were removed through direct testing. No differences between race or gender were observed. Of the 8 patients (25%) whose allergies were not removed, 5 had confirmed penicillin allergies with a positive reaction; 4 of these patients have since tolerated an alternative β-lactam (either a cephalosporin or carbapenem). Three patients had inconclusive tests, most often because their positive control was nonreactive during the percutaneous portion of the skin test; these allergies could neither be confirmed nor removed. Two of these patients have since tolerated alternative β-lactams (both cephalosporins). Although these 8 patients should not be rechallenged with a penicillin antibiotic, they could still be considered for alternative β-lactams, based on the nature and histories of their allergies.

In total, we removed 86 allergies (31% of our patient population) using both BLAA and PAC (Figure). These patients were cleared for all β-lactams. One hundred eighty-eight patients (68%) were cleared to receive an alternative β-lactam based on the nature or history of the allergic reaction. β-lactam avoidance was recommended for only 4 patients (1%), as they had no exposure to any β-lactams, and they had a recent or severe reaction: 2 patients with anaphylaxis in the past 5 years, 1 with SJS/TEN, and 1 with recent convulsions after receiving cefepime. Combining patients whose penicillin allergies were removed with those who had been cleared for alternative β-lactam antibiotics, 99% of patients were cleared for a β-lactam antibiotic.

Discussion

We have implemented a unique and efficient way to evaluate, clarify, and clear β-lactam allergies. Our BLAA protocol allows for a smooth process by distributing the workload of evaluating and clarifying patients’ allergies over many inpatient CPS. Furthermore, the BLAA is readily accessible to health care providers (HCPs), allowing for optimal clinical decision making. HCPs can quickly gather further information on the β-lactam allergy, while seeing actionable recommendations, along with documentation of the PAC visit and subsequent events, if the patient has been seen.

This study demonstrated the promotion of alternative β-lactam use for nearly all patients: 99% of our patient population were deemed candidates for a β-lactam type antibiotic. This percentage included patients whose allergies have been fully cleared, both through BLAA alone and in PAC. Also included are patients who have been cleared for an alternative β-lactam and not necessarily a penicillin.

In our PAC, 8 patients were not cleared for penicillins: 5 had penicillin allergies confirmed, and 3 had inconclusive results. Based on the nature of their reactions and previous tolerance of alternative β-lactams, those 5 patients are still eligible for alternative β-lactams. Additionally, the 3 patients with inconclusive results are also eligible for alternative β-lactams for the same reasons. The patients for whom

Accounting for those patients who have not been seen in PAC, our results are in concordance with previous studies, which demonstrated that implementation of a similar BLAA process results in clearance of ≥ 90% of penicillin allergies.13-17Other studies have evaluated inpatient implementation of penicillin skin testing or oral challenges; in this study, however, BLAAs were completed while the patient was hospitalized, and patients were seen in PAC after discharge. Completing BLAA during hospitalization not only allows for faster assessment and facilitates decision making regarding most patients’ antibiotic regimens, but also provides a tool that can be used by many pharmacists and HCPs. The addition of our PAC to the BLAA protocol further strengthens the impact on clearance of patients’ penicillin allergies.

Limitations

Although our study demonstrates many benefits of implementation of a BLAA protocol and PAC, it has several limitations. This analysis was a retrospective review of the limited number of patients who had assessments completed. Additionally, many patients were waiting to be seen in PAC. This delay is largely due to the length of time to establish our pharmacist-run PAC, the limited number of pharmacists trained and available for skin testing, the time constraints of our staff, and COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, only pharmacists administer the BLAA questionnaire, but this process could be expanded to other professionals such as nursing staff. Also, this study was not set up as a before-and-after analysis that examined outcomes associated with individual patients. Future directions include assessing the clinical impact of this protocol, such as evaluating provider utilization of β-lactam antibiotics for patients with penicillin allergies and determining associated cost savings.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that implementation of a pharmacist-driven BLAA protocol and PAC can effectively remove inaccurate penicillin allergy labels and clear patients for alternative β-lactam antibiotic use. The BLAA process in conjunction with PAC will continue to be used to better evaluate, clarify, and clear patient allergies to optimize their care.

1. Lee CE, Zembower TR, Fotis MA, et al. The incidence of antimicrobial allergies in hospitalized patients: implications regarding prescribing patterns and emerging bacterial resistance. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(18):2819-2822. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.18.2819

2. Shenoy ES, Macy E, Rowe T, Blumenthal KG. Evaluation and management of penicillin allergy: a review. JAMA. 2019;321(2):188-199. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.19283

3. Castells M, Khan DA, Phillips EJ. Penicillin allergy. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(24):2338-2351. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1807761

4. Park M, Markus P, Matesic D, Li JTC. Safety and effectiveness of a preoperative allergy clinic in decreasing vancomycin use in patients with a history of penicillin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97(5):681-687. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61100-3

5. McDanel JS, Perencevich EN, Diekema DJ, et al. Comparative effectiveness of beta-lactams versus vancomycin for treatment of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections among 122 hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(3):361-367. doi:10.1093/cid/civ308

6. Blumenthal KG, Shenoy ES, Varughese CA, Hurwitz S, Hooper DC, Banerji A. Impact of a clinical guideline for prescribing antibiotics to inpatients reporting penicillin or cephalosporin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115(4):294-300.e2. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2015.05.011

7. Blumenthal KG, Parker RA, Shenoy ES, Walensky RP. Improving clinical outcomes in patients with methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and reported penicillin allergy. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(5):741-749. doi:10.1093/cid/civ394

8. Jeffres MN, Narayanan PP, Shuster JE, Schramm GE. Consequences of avoiding β-lactams in patients with β-lactam allergies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(4):1148-1153. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2015.10.026

9. Macy E, Contreras R. Health care use and serious infection prevalence associated with penicillin “allergy” in hospitalized patients: a cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(3):790-796. doi:10.1016/j.jaci2013.09.021

10. Charneski L, Deshpande G, Smith SW. Impact of an antimicrobial allergy label in the medical record on clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31(8):742-747. doi:10.1592/phco.31.8.742

11. Sade K, Holtzer I, Levo Y, Kivity S. The economic burden of antibiotic treatment of penicillin-allergic patients in internal medicine wards of a general tertiary care hospital. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33(4):501-506. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2222.2003.01638.x

12. Ness RA, Bennett JG, Elliott WV, Gillion AR, Pattanaik DN. Impact of β-lactam allergies on antimicrobial selection in an outpatient setting. South Med J. 2019;112(11):591-597. doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000001037

13. Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, et al. Implementing an antibiotic stewardship program: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(10):e51-e77. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw118

14. King EA, Challa S, Curtin P, Bielory L. Penicillin skin testing in hospitalized patients with beta-lactam allergies: effect on antibiotic selection and cost. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;117(1):67-71. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2016.04.021

15. Chen JR, Tarver SA, Alvarez KS, Tran T, Khan DA. A proactive approach to penicillin allergy testing in hospitalized patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(3):686-693. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2016.09.045

16. Rimawi RH, Cook PP, Gooch M, et al. The impact of penicillin skin testing of clinical practice and antimicrobial stewardship. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(6):341-345. doi:10.1002/jhm.2036

17. Heil EL, Bork JT, Schmalzle SA, et al. Implementation of an infectious disease fellow-managed penicillin allergy skin testing service. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3(3):155-161. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofw155

Allergies to β-lactam antibiotics are among the most documented drug allergies, and approximately 10% of the US population reports an allergy specifically to penicillin.1,2 Many allergic reactions are mediated via the antibody immunoglobulin E (IgE), producing an immediate hypersensitivity response, such as hives or anaphylaxis, which can be life threatening. Reactions also may be mediated by T cells of the immune system, which target various cell lines and can cause a drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms or Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN).3Although β-lactam and penicillin allergies are frequently reported, < 5% manifest as either an IgE or T-cell–mediated response.4Furthermore, for the small proportion of patients who once had a true IgE-mediated reaction, including anaphylaxis, 80% experience a decrease in IgE antibodies over time, resulting in a loss of allergic response after about 10 years.2 Due to this decline in IgE response and the initial mislabeling of mild non-IgE penicillin reactions, 95% of patients who are labeled as penicillin-allergic can eventually tolerate a penicillin.2

When a patient’s β-lactam allergy is never reevaluated, negative consequences can ensue. This allergy in a patient’s medical record can lead to the inappropriate avoidance of the entire β-lactam antibiotic class, which includes all penicillins, cephalosporins, and carbapenems. Withholding these antibiotics in certain situations can lead to negative patient outcomes.5-7 For example, the drugs of choice for the infections syphilis and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (S aureus) are a penicillin or cephalosporin, and patients labeled as penicillin-allergic are more likely to experience treatment failure from using second-line therapies.8 Additionally, receiving non-β-lactam antibiotics puts patients at risk of multidrug-resistant pathogens like methicillin-resistant S aureus and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) as well as adverse effects, such as Clostridioides difficile infection.9 Using alternative, and likely broad-spectrum, antibiotics also can be financially detrimental: These medications often are more costly than their β-lactam alternatives, and the inappropriate use of therapies can result in longer hospital courses.9-11

Penicillin allergies can complicate the antibiotic treatment strategy. The Memphis Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MVAMC) in Tennessee recently examined the negative sequelae of β-lactam allergies and found that more than half the patients received inappropriate antibiotics based on guideline recommendations, allergy history, and culture and sensitivity data.12 To mitigate the problems for patients with β-lactam allergies, the 2016 guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) on the Implementation of Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs (ASP) recommend that these patients undergo allergy assessment and penicillin skin testing.13In November 2017, MVAMC implemented such a process. The purpose of this study was to describe our pharmacist-run β-lactam allergy assessment (BLAA) protocol and penicillin allergy clinic (PAC) and evaluate their overall outcomes: the proportion of patients who have been cleared to receive an alternative β-lactam antibiotic or who have had their allergy removed altogether.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective, observational study with approval from the institutional review board at MVAMC. This institution is an academic teaching center with 240 acute care beds and a variety of outpatient clinics available at the main campus, serving veterans in Memphis and the Mid-South area, including west Tennessee, northern Mississippi, and northeastern Arkansas. Patients were consecutively evaluated from November 2017 through February 2020. All MVAMC patients with a documented β-lactam allergy were eligible for inclusion; there were no exclusion criteria. Electronic health record data were assessed and included basic patient demographics, allergy history, and the outcome of the BLAA and PAC. Descriptive statistics were used for data analysis.

The purpose of the BLAA process is to evaluate, clarify, and potentially clear patients of their β-lactam allergies. Started in November 2017, the process includes appropriate patient screening with documentation of the β-lactam allergy. When patients with a β-lactam allergy are admitted to the hospital, they are interviewed by an inpatient CPS. This pharmacist then enters an assessment into the patient’s chart, which includes details of the allergen, reaction, and timing of the event. Based on this information, the CPS provides recommendations: clearance for alternative β-lactams, avoidance of all β-lactams, or removal of the allergy.

In January 2019, the pharmacist-driven penicillin allergy clinic (PAC) was started. Eligible patients receive a skin test to confirm or rule out their allergy after hospital discharge. To facilitate patient identification and screening, the ASP/infectious diseases (ID) clinical pharmacist runs a daily report of hospitalized patients with documented β-lactam allergies. All inpatient CPSs had access to this report and could easily identify and interview patients. Following the interview, the pharmacist enters a note in the patient’s chart, using the BLAA template (eFigures 1 and 2). On completion, a note is viewable in the Notes section adjacent to the patient’s allergies. The pharmacist then can enter a PAC consult for eligible patients. Although most patients qualify for PAC, exclusion criteria include non–IgE-mediated allergies (ie, SJS/TEN), allergies to β-lactams other than penicillins, or recent reactions (ie, within the past 5 years). Each inpatient CPS is trained on this BLAA process, which includes patient screening, chart review, patient interviewing, and the BLAA template and note completion. Pharmacists must demonstrate competency in completing 5 BLAA notes with review from the ASP/ID pharmacist. Once training is completed, this process is integrated into the pharmacist’s everyday workflow.

On receipt of the PAC consult, the ASP/ID pharmacist reviews the patient chart to further assess for eligibility and to determine whether oral challenge alone or skin testing followed by the oral challenge is required based on patient risk stratification (Table 1).3Relative contraindications to PAC include severe or unstable lung disease that requires home oxygen, frequent or recurrent heart failure exacerbations, or patients with acute or unstable cardiopulmonary, neurologic, or mental health conditions. These scenarios are discussed case by case with the allergy/immunology (A/I) physician.

The ASP/ID pharmacist also reviews the patient’s chart for medications that may blunt the histamine response during drug testing. The need to hold these medications before PAC also are individually assessed in conjunction with the A/I physician. The ASP/ID pharmacist and 3 other CPS involved in the creation of the BLAA and PAC have received formal hands-on training on penicillin allergy testing. The PAC process consists of a penicillin skin test, followed by the amoxicillin oral challenge.3The ASP/ID clinical pharmacist who is trained in penicillin skin testing performs all duties in PAC, with oversight from the A/I attending physician as needed. Currently, the ASP/ID pharmacist runs the PAC once a week with the A/I physician available if needed. Along with documenting an A/I clinic note detailing the events of PAC, the ASP/ID pharmacist also will add an addendum to the original BLAA note. If the allergy is removed through direct testing, it also can be removed from the patient’s profile after discussion with the A/I physician. Therefore, the full details necessary to evaluate, clarify, and clear the patient of their β-lactam allergy are in one place.

Results

We evaluated 278 patients, using the BLAA protocol. In this veteran population, patients were generally older males and evenly split between African American and White patients (Table 2). Most patients reported an allergy to penicillin, with a rash being the most common reaction (Table 3).

Of the 278 assessed, 246 patients were evaluated via our BLAA alone and were not seen in PAC. We were able to remove 25% of these patients’ allergies by performing a thorough assessment. Of the 184 patients whose allergies could not be removed via the BLAA alone, 147 (80%) were still eligible for PAC but are awaiting scheduling. Patients ineligible for PAC included those with a cephalosporin allergy or a severe and non–IgE-mediated reaction. Other ineligible patients who were not eligible included those with diseases where risk of testing outweighed the benefits.

Of the 32 patients who were seen in PAC, 75% of allergies were removed through direct testing. No differences between race or gender were observed. Of the 8 patients (25%) whose allergies were not removed, 5 had confirmed penicillin allergies with a positive reaction; 4 of these patients have since tolerated an alternative β-lactam (either a cephalosporin or carbapenem). Three patients had inconclusive tests, most often because their positive control was nonreactive during the percutaneous portion of the skin test; these allergies could neither be confirmed nor removed. Two of these patients have since tolerated alternative β-lactams (both cephalosporins). Although these 8 patients should not be rechallenged with a penicillin antibiotic, they could still be considered for alternative β-lactams, based on the nature and histories of their allergies.

In total, we removed 86 allergies (31% of our patient population) using both BLAA and PAC (Figure). These patients were cleared for all β-lactams. One hundred eighty-eight patients (68%) were cleared to receive an alternative β-lactam based on the nature or history of the allergic reaction. β-lactam avoidance was recommended for only 4 patients (1%), as they had no exposure to any β-lactams, and they had a recent or severe reaction: 2 patients with anaphylaxis in the past 5 years, 1 with SJS/TEN, and 1 with recent convulsions after receiving cefepime. Combining patients whose penicillin allergies were removed with those who had been cleared for alternative β-lactam antibiotics, 99% of patients were cleared for a β-lactam antibiotic.

Discussion

We have implemented a unique and efficient way to evaluate, clarify, and clear β-lactam allergies. Our BLAA protocol allows for a smooth process by distributing the workload of evaluating and clarifying patients’ allergies over many inpatient CPS. Furthermore, the BLAA is readily accessible to health care providers (HCPs), allowing for optimal clinical decision making. HCPs can quickly gather further information on the β-lactam allergy, while seeing actionable recommendations, along with documentation of the PAC visit and subsequent events, if the patient has been seen.

This study demonstrated the promotion of alternative β-lactam use for nearly all patients: 99% of our patient population were deemed candidates for a β-lactam type antibiotic. This percentage included patients whose allergies have been fully cleared, both through BLAA alone and in PAC. Also included are patients who have been cleared for an alternative β-lactam and not necessarily a penicillin.

In our PAC, 8 patients were not cleared for penicillins: 5 had penicillin allergies confirmed, and 3 had inconclusive results. Based on the nature of their reactions and previous tolerance of alternative β-lactams, those 5 patients are still eligible for alternative β-lactams. Additionally, the 3 patients with inconclusive results are also eligible for alternative β-lactams for the same reasons. The patients for whom

Accounting for those patients who have not been seen in PAC, our results are in concordance with previous studies, which demonstrated that implementation of a similar BLAA process results in clearance of ≥ 90% of penicillin allergies.13-17Other studies have evaluated inpatient implementation of penicillin skin testing or oral challenges; in this study, however, BLAAs were completed while the patient was hospitalized, and patients were seen in PAC after discharge. Completing BLAA during hospitalization not only allows for faster assessment and facilitates decision making regarding most patients’ antibiotic regimens, but also provides a tool that can be used by many pharmacists and HCPs. The addition of our PAC to the BLAA protocol further strengthens the impact on clearance of patients’ penicillin allergies.

Limitations

Although our study demonstrates many benefits of implementation of a BLAA protocol and PAC, it has several limitations. This analysis was a retrospective review of the limited number of patients who had assessments completed. Additionally, many patients were waiting to be seen in PAC. This delay is largely due to the length of time to establish our pharmacist-run PAC, the limited number of pharmacists trained and available for skin testing, the time constraints of our staff, and COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, only pharmacists administer the BLAA questionnaire, but this process could be expanded to other professionals such as nursing staff. Also, this study was not set up as a before-and-after analysis that examined outcomes associated with individual patients. Future directions include assessing the clinical impact of this protocol, such as evaluating provider utilization of β-lactam antibiotics for patients with penicillin allergies and determining associated cost savings.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that implementation of a pharmacist-driven BLAA protocol and PAC can effectively remove inaccurate penicillin allergy labels and clear patients for alternative β-lactam antibiotic use. The BLAA process in conjunction with PAC will continue to be used to better evaluate, clarify, and clear patient allergies to optimize their care.

Allergies to β-lactam antibiotics are among the most documented drug allergies, and approximately 10% of the US population reports an allergy specifically to penicillin.1,2 Many allergic reactions are mediated via the antibody immunoglobulin E (IgE), producing an immediate hypersensitivity response, such as hives or anaphylaxis, which can be life threatening. Reactions also may be mediated by T cells of the immune system, which target various cell lines and can cause a drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms or Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN).3Although β-lactam and penicillin allergies are frequently reported, < 5% manifest as either an IgE or T-cell–mediated response.4Furthermore, for the small proportion of patients who once had a true IgE-mediated reaction, including anaphylaxis, 80% experience a decrease in IgE antibodies over time, resulting in a loss of allergic response after about 10 years.2 Due to this decline in IgE response and the initial mislabeling of mild non-IgE penicillin reactions, 95% of patients who are labeled as penicillin-allergic can eventually tolerate a penicillin.2

When a patient’s β-lactam allergy is never reevaluated, negative consequences can ensue. This allergy in a patient’s medical record can lead to the inappropriate avoidance of the entire β-lactam antibiotic class, which includes all penicillins, cephalosporins, and carbapenems. Withholding these antibiotics in certain situations can lead to negative patient outcomes.5-7 For example, the drugs of choice for the infections syphilis and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (S aureus) are a penicillin or cephalosporin, and patients labeled as penicillin-allergic are more likely to experience treatment failure from using second-line therapies.8 Additionally, receiving non-β-lactam antibiotics puts patients at risk of multidrug-resistant pathogens like methicillin-resistant S aureus and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) as well as adverse effects, such as Clostridioides difficile infection.9 Using alternative, and likely broad-spectrum, antibiotics also can be financially detrimental: These medications often are more costly than their β-lactam alternatives, and the inappropriate use of therapies can result in longer hospital courses.9-11

Penicillin allergies can complicate the antibiotic treatment strategy. The Memphis Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MVAMC) in Tennessee recently examined the negative sequelae of β-lactam allergies and found that more than half the patients received inappropriate antibiotics based on guideline recommendations, allergy history, and culture and sensitivity data.12 To mitigate the problems for patients with β-lactam allergies, the 2016 guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) on the Implementation of Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs (ASP) recommend that these patients undergo allergy assessment and penicillin skin testing.13In November 2017, MVAMC implemented such a process. The purpose of this study was to describe our pharmacist-run β-lactam allergy assessment (BLAA) protocol and penicillin allergy clinic (PAC) and evaluate their overall outcomes: the proportion of patients who have been cleared to receive an alternative β-lactam antibiotic or who have had their allergy removed altogether.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective, observational study with approval from the institutional review board at MVAMC. This institution is an academic teaching center with 240 acute care beds and a variety of outpatient clinics available at the main campus, serving veterans in Memphis and the Mid-South area, including west Tennessee, northern Mississippi, and northeastern Arkansas. Patients were consecutively evaluated from November 2017 through February 2020. All MVAMC patients with a documented β-lactam allergy were eligible for inclusion; there were no exclusion criteria. Electronic health record data were assessed and included basic patient demographics, allergy history, and the outcome of the BLAA and PAC. Descriptive statistics were used for data analysis.

The purpose of the BLAA process is to evaluate, clarify, and potentially clear patients of their β-lactam allergies. Started in November 2017, the process includes appropriate patient screening with documentation of the β-lactam allergy. When patients with a β-lactam allergy are admitted to the hospital, they are interviewed by an inpatient CPS. This pharmacist then enters an assessment into the patient’s chart, which includes details of the allergen, reaction, and timing of the event. Based on this information, the CPS provides recommendations: clearance for alternative β-lactams, avoidance of all β-lactams, or removal of the allergy.

In January 2019, the pharmacist-driven penicillin allergy clinic (PAC) was started. Eligible patients receive a skin test to confirm or rule out their allergy after hospital discharge. To facilitate patient identification and screening, the ASP/infectious diseases (ID) clinical pharmacist runs a daily report of hospitalized patients with documented β-lactam allergies. All inpatient CPSs had access to this report and could easily identify and interview patients. Following the interview, the pharmacist enters a note in the patient’s chart, using the BLAA template (eFigures 1 and 2). On completion, a note is viewable in the Notes section adjacent to the patient’s allergies. The pharmacist then can enter a PAC consult for eligible patients. Although most patients qualify for PAC, exclusion criteria include non–IgE-mediated allergies (ie, SJS/TEN), allergies to β-lactams other than penicillins, or recent reactions (ie, within the past 5 years). Each inpatient CPS is trained on this BLAA process, which includes patient screening, chart review, patient interviewing, and the BLAA template and note completion. Pharmacists must demonstrate competency in completing 5 BLAA notes with review from the ASP/ID pharmacist. Once training is completed, this process is integrated into the pharmacist’s everyday workflow.

On receipt of the PAC consult, the ASP/ID pharmacist reviews the patient chart to further assess for eligibility and to determine whether oral challenge alone or skin testing followed by the oral challenge is required based on patient risk stratification (Table 1).3Relative contraindications to PAC include severe or unstable lung disease that requires home oxygen, frequent or recurrent heart failure exacerbations, or patients with acute or unstable cardiopulmonary, neurologic, or mental health conditions. These scenarios are discussed case by case with the allergy/immunology (A/I) physician.

The ASP/ID pharmacist also reviews the patient’s chart for medications that may blunt the histamine response during drug testing. The need to hold these medications before PAC also are individually assessed in conjunction with the A/I physician. The ASP/ID pharmacist and 3 other CPS involved in the creation of the BLAA and PAC have received formal hands-on training on penicillin allergy testing. The PAC process consists of a penicillin skin test, followed by the amoxicillin oral challenge.3The ASP/ID clinical pharmacist who is trained in penicillin skin testing performs all duties in PAC, with oversight from the A/I attending physician as needed. Currently, the ASP/ID pharmacist runs the PAC once a week with the A/I physician available if needed. Along with documenting an A/I clinic note detailing the events of PAC, the ASP/ID pharmacist also will add an addendum to the original BLAA note. If the allergy is removed through direct testing, it also can be removed from the patient’s profile after discussion with the A/I physician. Therefore, the full details necessary to evaluate, clarify, and clear the patient of their β-lactam allergy are in one place.

Results

We evaluated 278 patients, using the BLAA protocol. In this veteran population, patients were generally older males and evenly split between African American and White patients (Table 2). Most patients reported an allergy to penicillin, with a rash being the most common reaction (Table 3).

Of the 278 assessed, 246 patients were evaluated via our BLAA alone and were not seen in PAC. We were able to remove 25% of these patients’ allergies by performing a thorough assessment. Of the 184 patients whose allergies could not be removed via the BLAA alone, 147 (80%) were still eligible for PAC but are awaiting scheduling. Patients ineligible for PAC included those with a cephalosporin allergy or a severe and non–IgE-mediated reaction. Other ineligible patients who were not eligible included those with diseases where risk of testing outweighed the benefits.

Of the 32 patients who were seen in PAC, 75% of allergies were removed through direct testing. No differences between race or gender were observed. Of the 8 patients (25%) whose allergies were not removed, 5 had confirmed penicillin allergies with a positive reaction; 4 of these patients have since tolerated an alternative β-lactam (either a cephalosporin or carbapenem). Three patients had inconclusive tests, most often because their positive control was nonreactive during the percutaneous portion of the skin test; these allergies could neither be confirmed nor removed. Two of these patients have since tolerated alternative β-lactams (both cephalosporins). Although these 8 patients should not be rechallenged with a penicillin antibiotic, they could still be considered for alternative β-lactams, based on the nature and histories of their allergies.

In total, we removed 86 allergies (31% of our patient population) using both BLAA and PAC (Figure). These patients were cleared for all β-lactams. One hundred eighty-eight patients (68%) were cleared to receive an alternative β-lactam based on the nature or history of the allergic reaction. β-lactam avoidance was recommended for only 4 patients (1%), as they had no exposure to any β-lactams, and they had a recent or severe reaction: 2 patients with anaphylaxis in the past 5 years, 1 with SJS/TEN, and 1 with recent convulsions after receiving cefepime. Combining patients whose penicillin allergies were removed with those who had been cleared for alternative β-lactam antibiotics, 99% of patients were cleared for a β-lactam antibiotic.

Discussion

We have implemented a unique and efficient way to evaluate, clarify, and clear β-lactam allergies. Our BLAA protocol allows for a smooth process by distributing the workload of evaluating and clarifying patients’ allergies over many inpatient CPS. Furthermore, the BLAA is readily accessible to health care providers (HCPs), allowing for optimal clinical decision making. HCPs can quickly gather further information on the β-lactam allergy, while seeing actionable recommendations, along with documentation of the PAC visit and subsequent events, if the patient has been seen.

This study demonstrated the promotion of alternative β-lactam use for nearly all patients: 99% of our patient population were deemed candidates for a β-lactam type antibiotic. This percentage included patients whose allergies have been fully cleared, both through BLAA alone and in PAC. Also included are patients who have been cleared for an alternative β-lactam and not necessarily a penicillin.

In our PAC, 8 patients were not cleared for penicillins: 5 had penicillin allergies confirmed, and 3 had inconclusive results. Based on the nature of their reactions and previous tolerance of alternative β-lactams, those 5 patients are still eligible for alternative β-lactams. Additionally, the 3 patients with inconclusive results are also eligible for alternative β-lactams for the same reasons. The patients for whom

Accounting for those patients who have not been seen in PAC, our results are in concordance with previous studies, which demonstrated that implementation of a similar BLAA process results in clearance of ≥ 90% of penicillin allergies.13-17Other studies have evaluated inpatient implementation of penicillin skin testing or oral challenges; in this study, however, BLAAs were completed while the patient was hospitalized, and patients were seen in PAC after discharge. Completing BLAA during hospitalization not only allows for faster assessment and facilitates decision making regarding most patients’ antibiotic regimens, but also provides a tool that can be used by many pharmacists and HCPs. The addition of our PAC to the BLAA protocol further strengthens the impact on clearance of patients’ penicillin allergies.

Limitations

Although our study demonstrates many benefits of implementation of a BLAA protocol and PAC, it has several limitations. This analysis was a retrospective review of the limited number of patients who had assessments completed. Additionally, many patients were waiting to be seen in PAC. This delay is largely due to the length of time to establish our pharmacist-run PAC, the limited number of pharmacists trained and available for skin testing, the time constraints of our staff, and COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, only pharmacists administer the BLAA questionnaire, but this process could be expanded to other professionals such as nursing staff. Also, this study was not set up as a before-and-after analysis that examined outcomes associated with individual patients. Future directions include assessing the clinical impact of this protocol, such as evaluating provider utilization of β-lactam antibiotics for patients with penicillin allergies and determining associated cost savings.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that implementation of a pharmacist-driven BLAA protocol and PAC can effectively remove inaccurate penicillin allergy labels and clear patients for alternative β-lactam antibiotic use. The BLAA process in conjunction with PAC will continue to be used to better evaluate, clarify, and clear patient allergies to optimize their care.

1. Lee CE, Zembower TR, Fotis MA, et al. The incidence of antimicrobial allergies in hospitalized patients: implications regarding prescribing patterns and emerging bacterial resistance. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(18):2819-2822. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.18.2819

2. Shenoy ES, Macy E, Rowe T, Blumenthal KG. Evaluation and management of penicillin allergy: a review. JAMA. 2019;321(2):188-199. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.19283

3. Castells M, Khan DA, Phillips EJ. Penicillin allergy. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(24):2338-2351. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1807761

4. Park M, Markus P, Matesic D, Li JTC. Safety and effectiveness of a preoperative allergy clinic in decreasing vancomycin use in patients with a history of penicillin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97(5):681-687. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61100-3

5. McDanel JS, Perencevich EN, Diekema DJ, et al. Comparative effectiveness of beta-lactams versus vancomycin for treatment of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections among 122 hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(3):361-367. doi:10.1093/cid/civ308

6. Blumenthal KG, Shenoy ES, Varughese CA, Hurwitz S, Hooper DC, Banerji A. Impact of a clinical guideline for prescribing antibiotics to inpatients reporting penicillin or cephalosporin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115(4):294-300.e2. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2015.05.011

7. Blumenthal KG, Parker RA, Shenoy ES, Walensky RP. Improving clinical outcomes in patients with methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and reported penicillin allergy. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(5):741-749. doi:10.1093/cid/civ394

8. Jeffres MN, Narayanan PP, Shuster JE, Schramm GE. Consequences of avoiding β-lactams in patients with β-lactam allergies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(4):1148-1153. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2015.10.026

9. Macy E, Contreras R. Health care use and serious infection prevalence associated with penicillin “allergy” in hospitalized patients: a cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(3):790-796. doi:10.1016/j.jaci2013.09.021

10. Charneski L, Deshpande G, Smith SW. Impact of an antimicrobial allergy label in the medical record on clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31(8):742-747. doi:10.1592/phco.31.8.742

11. Sade K, Holtzer I, Levo Y, Kivity S. The economic burden of antibiotic treatment of penicillin-allergic patients in internal medicine wards of a general tertiary care hospital. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33(4):501-506. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2222.2003.01638.x

12. Ness RA, Bennett JG, Elliott WV, Gillion AR, Pattanaik DN. Impact of β-lactam allergies on antimicrobial selection in an outpatient setting. South Med J. 2019;112(11):591-597. doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000001037

13. Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, et al. Implementing an antibiotic stewardship program: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(10):e51-e77. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw118

14. King EA, Challa S, Curtin P, Bielory L. Penicillin skin testing in hospitalized patients with beta-lactam allergies: effect on antibiotic selection and cost. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;117(1):67-71. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2016.04.021

15. Chen JR, Tarver SA, Alvarez KS, Tran T, Khan DA. A proactive approach to penicillin allergy testing in hospitalized patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(3):686-693. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2016.09.045

16. Rimawi RH, Cook PP, Gooch M, et al. The impact of penicillin skin testing of clinical practice and antimicrobial stewardship. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(6):341-345. doi:10.1002/jhm.2036

17. Heil EL, Bork JT, Schmalzle SA, et al. Implementation of an infectious disease fellow-managed penicillin allergy skin testing service. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3(3):155-161. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofw155

1. Lee CE, Zembower TR, Fotis MA, et al. The incidence of antimicrobial allergies in hospitalized patients: implications regarding prescribing patterns and emerging bacterial resistance. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(18):2819-2822. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.18.2819

2. Shenoy ES, Macy E, Rowe T, Blumenthal KG. Evaluation and management of penicillin allergy: a review. JAMA. 2019;321(2):188-199. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.19283

3. Castells M, Khan DA, Phillips EJ. Penicillin allergy. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(24):2338-2351. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1807761

4. Park M, Markus P, Matesic D, Li JTC. Safety and effectiveness of a preoperative allergy clinic in decreasing vancomycin use in patients with a history of penicillin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97(5):681-687. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61100-3

5. McDanel JS, Perencevich EN, Diekema DJ, et al. Comparative effectiveness of beta-lactams versus vancomycin for treatment of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections among 122 hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(3):361-367. doi:10.1093/cid/civ308

6. Blumenthal KG, Shenoy ES, Varughese CA, Hurwitz S, Hooper DC, Banerji A. Impact of a clinical guideline for prescribing antibiotics to inpatients reporting penicillin or cephalosporin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115(4):294-300.e2. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2015.05.011

7. Blumenthal KG, Parker RA, Shenoy ES, Walensky RP. Improving clinical outcomes in patients with methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and reported penicillin allergy. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(5):741-749. doi:10.1093/cid/civ394

8. Jeffres MN, Narayanan PP, Shuster JE, Schramm GE. Consequences of avoiding β-lactams in patients with β-lactam allergies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(4):1148-1153. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2015.10.026

9. Macy E, Contreras R. Health care use and serious infection prevalence associated with penicillin “allergy” in hospitalized patients: a cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(3):790-796. doi:10.1016/j.jaci2013.09.021

10. Charneski L, Deshpande G, Smith SW. Impact of an antimicrobial allergy label in the medical record on clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31(8):742-747. doi:10.1592/phco.31.8.742

11. Sade K, Holtzer I, Levo Y, Kivity S. The economic burden of antibiotic treatment of penicillin-allergic patients in internal medicine wards of a general tertiary care hospital. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33(4):501-506. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2222.2003.01638.x

12. Ness RA, Bennett JG, Elliott WV, Gillion AR, Pattanaik DN. Impact of β-lactam allergies on antimicrobial selection in an outpatient setting. South Med J. 2019;112(11):591-597. doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000001037

13. Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, et al. Implementing an antibiotic stewardship program: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(10):e51-e77. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw118

14. King EA, Challa S, Curtin P, Bielory L. Penicillin skin testing in hospitalized patients with beta-lactam allergies: effect on antibiotic selection and cost. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;117(1):67-71. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2016.04.021

15. Chen JR, Tarver SA, Alvarez KS, Tran T, Khan DA. A proactive approach to penicillin allergy testing in hospitalized patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(3):686-693. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2016.09.045

16. Rimawi RH, Cook PP, Gooch M, et al. The impact of penicillin skin testing of clinical practice and antimicrobial stewardship. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(6):341-345. doi:10.1002/jhm.2036

17. Heil EL, Bork JT, Schmalzle SA, et al. Implementation of an infectious disease fellow-managed penicillin allergy skin testing service. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3(3):155-161. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofw155