User login

How to avert postoperative wound complication—and treat it when it occurs

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Despite advances in medicine and surgery over the past century, postoperative wound complication remains a serious challenge. When a complication occurs, it translates into prolonged hospitalization, lost time from work, and greater cost to the patient and the health-care system.

Prevention of wound complication begins well before surgery. Requirements include:

- understanding of wound healing (see below) and the classification of wounds (TABLE 1)

- thorough assessment of the patient for risk factors for impaired wound healing, such as diabetes or use of corticosteroid medication (TABLE 2)

- antibiotic prophylaxis, if indicated (TABLE 3)

- good surgical technique, gentle tissue handling, and meticulous hemostasis

- placement of a drain, when appropriate

- awareness of technology that can enhance healing

- close monitoring in the postoperative period

- intervention at the first hint of abnormality.

In this article, we describe predisposing factors and preventive techniques and measures, and outline the most common wound complications, from seroma to dehiscence, including effective management strategies.

It was pioneering Scottish surgeon John Hunter who noted that “injury alone has in all cases the tendency to produce the disposition and means of a cure.”15

Unlike the tissue regeneration that occurs primarily in lower animals, human wound healing is mediated by collagen deposition, or scarring, which provides structural support to the wound. This scarring process may itself cause a variety of clinical problems.

Wound healing is characterized by overlapping, largely interdependent phases, with no clear demarcation between them. Failure in one phase may have a negative impact on the overall outcome.

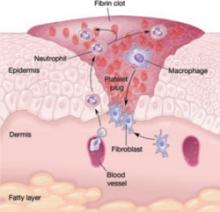

In general, wound healing involves two phases: inflammation and proliferation. Within these phases, the following processes occur: scar maturation, wound contraction, and epithelialization. These repair mechanisms are activated in response to tissue injury even when it is surgically induced.

Inflammatory phase

The initial response to tissue injury is inflammation, which is mediated by various amines, enzymes, and other substances. This inflammation can be further broken down into vascular and cellular responses.

Inflammation triggers increased blood flow and migration of neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, and other cells into the wound.

The first burst of blood acts to cleanse the wound of foreign debris. It is followed by vasoconstriction, which is mediated by thromboxane 2, to decrease blood loss. Vasodilation then occurs once histamine and serotonin are released, permitting increased blood flow to the wound. The surge in blood flow accounts for the increased warmth and redness of the wound. Vasodilation also increases capillary permeability, allowing the migration of red blood cells, platelets, leukocytes, plasma, and other tissue fluids into the interstitium of the wound. This migration accounts for wound edema.

In the cellular response, which is facilitated by increased blood flow, cell migration occurs as part of an immune response. Neutrophils, the first cells to enter the wound, engage in phagocytosis of bacteria and debris. Subsequently, there is migration of monocytes, macrophages, and other cells. This nonspecific immune response is sustained by prostaglandins, aided by complement factors and cytokines. A specific immune response follows, aimed at destroying specific antigens, and involves both B- and T-lymphocytes.

Proliferative phase

Proliferation is characterized by the infiltration of endothelial cells and fibroblasts and subsequent collagen deposition along a previously formed fibrin network. This new, highly vascularized tissue assumes a granular appearance—hence, the term “granulation tissue.”

Collagen that is deposited in the wound undergoes maturation and remodeling, increasing the tensile strength of the wound. The process continues for months after the initial insult.

All wounds undergo some degree of contraction, but the process is more relevant in wounds that remain open or involve significant tissue loss.

Last, the external covering of the wound is restored by epithelialization.

TABLE 1

Classification of surgical wounds

| CLASS I – Clean wounds (infection rate <5%) |

|

| CLASS II – Clean–contaminated wounds (infection rate 2–10%) |

|

| CLASS III – Contaminated wounds (infection rate 15–20%) |

|

| CLASS IV – Dirty or infected wounds (infection rate >30%) |

|

| SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Surgeons |

TABLE 2

Risk factors for poor wound healing and dehiscence

| Poor wound healing |

|

| Abdominal wound dehiscence |

|

| SOURCE: Carlson,11 Cliby12. |

Conditions and drugs that impair healing

Preexisting medical conditions may limit healing, especially conditions associated with diminished delivery of oxygen and nutrients to healing tissues.

Diabetes can damage the vasculature and may impair healing if the blood glucose level is markedly elevated in the perioperative period. Such an elevation impedes transport of vitamin C, a key component of collagen synthesis.

Malignancy and immunosuppressive disorders may prevent optimal healing by compromising the immune response.

Bacterial vaginosis, a common polymicrobial infection involving aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, appears to be associated with postoperative febrile morbidity and surgical-site infection, particularly after hysterectomy.1 Current guidelines recommend that medical therapy for bacterial vaginosis be instituted at least 4 days before surgery and continued postoperatively.

Because steroids, NSAIDs, and chemotherapy agents impede wound healing, and anticoagulants may interfere with granulation, it is crucial to review the patient’s medications well in advance of surgery.

Nutrition plays a critical role

The importance of nutrition cannot be overstated. A significant percentage of patients are thought to have some degree of nutritional deficiency preoperatively. This deficiency may alter the inflammatory response, impair collagen synthesis, and reduce the tensile strength of the wound.

Because healing requires energy, deficits in carbohydrates may limit protein utilization, and deficiencies of vitamins and micronutrients can also interfere with healing.2

Obesity, too, increases the risk of postoperative wound complication. Markedly obese patients have a thick, avascular, subcutaneous layer of fat that compromises healing.3

Meticulous technique required

Good surgical technique and appropriate use of antibiotics are critical components of successful wound healing.

When placing the incision, avoid the moist, bacteria-laden subpannicular crease in the markedly obese.

During a procedure, handle tissue gently, keep it moist, and make minimal use of electrocautery to reduce tissue injury and promote healing. Keep operating time and blood loss to a minimum, and debride the wound of any foreign material and devitalized tissue.

Multiple studies have demonstrated that judicious use of prophylactic antibiotics significantly decreases the incidence of wound infection, particularly in relation to hysterectomy and vaginal procedures and when entry into bowel is anticipated.4,5 A number of prophylactic regimens are given in TABLE 3.

Meticulous hemostasis at the time of closure is imperative. When complete hemostasis cannot be confirmed, place a small drain in the subcutaneous space (or subfascial space, if there is oozing on the muscle bed) and apply a pressure dressing to help prevent hematoma. Although a drain is not a substitute for precise hemostasis or careful surgical technique, it may be helpful when there is concern about oozing or a “wet” surface, or when the patient is markedly obese.

Some practitioners have expressed concern over the risk of bacterial migration and infection with placement of a drain, but others, including us, advocate use of a drain in the subcutaneous space to help remove residual blood, fluid, and other debris to prevent the formation of dead space and infection and promote wound closure and healing. In a small study, Gallup and associates demonstrated a decreased incidence of wound breakdown when a drain was placed.6

A closed-suction drain, such as a Jackson-Pratt or Hemovac model, helps minimize wound complication when it is placed in the subcutaneous layer. (Avoid a rubber Penrose drain because it may allow bacteria to enter the wound.) It is imperative that the drain exit the body via a separate site and not through the incision itself. We advocate removal when less than 30 mL of fluid accumulates in the reservoir over 24 hours.

TABLE 3

3 prophylactic antibiotic regimens

| Procedure | Antibiotic | Single intravenous dose |

|---|---|---|

| Hysterectomy and urogynecologic procedures, including those that involve mesh | Cefazolin | 1 g or 2 g |

| Clindamycin plus gentamicin, a quinolone, or aztreonam | 600 mg plus 1.5 mg/kg, 400 mg, or 1 g, respectively | |

| Metronidazole plus gentamicin or a quinolone | 500 mg plus 1.5 mg/kg or 400 mg, respectively | |

| SOURCE: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists5 | ||

Fluid within the wound does not always indicate infection

Wound collections are not necessarily indicative of infection; collections of fluid within the wound may represent a serous transudate, blood, pus, or a combination of these. If the fluid is not addressed, however, fulminant infection may be the result.

Seroma is usually painless

A seroma is a collection of wound exudates within the dead space. Seroma typically involves thin, pink, watery discharge and minimal edge separation. In some cases, there may be surrounding edema but generally little to no tenderness.

When a seroma is detected, remove the staples or stitches in the area of concern and explore the wound. It is essential to ensure fascial integrity, as serous wound drainage may be a sign of impending evisceration. After these measures are taken, cleanse and lightly pack the wound to permit drainage.

Hematoma requires identification of the source of bleeding

Hematoma represents blood or a blood clot within the tissues beneath the skin. It may be caused by persistent bleeding of a vessel, although the pressure within the wound and the pressure produced by the dressing often provide tamponade on the bleeding source, in which case the hematoma forms with no active bleeding.

Hematoma is usually caused by small bleeding vessels that were not apparent at the time of surgery or were not cauterized or ligated at the time of closure. For this reason, it is important to achieve good hemostasis and a “dry” wound before closing the skin.

When hematoma is suspected, open the wound enough to permit adequate exposure and identify the source of bleeding. Evacuate as much blood and clot as possible because blood is an ideal medium for bacterial growth. If active bleeding is found, use a silver nitrate applicator or handheld cautery pen to accomplish hemostasis at bedside. If bleeding is more severe, or the source cannot be visualized, consider returning to the operating room for more extensive exploration.

Once hemostasis is achieved, irrigate the wound copiously and institute local wound care.

How common is infection?

Before it is possible to address this question, it is necessary to clarify the terminology of infection. Contamination and colonization are different entities. The first refers to the presence of bacteria without multiplication. The latter describes the multiplication of bacteria in the absence of a host response. When infection is present, bacterial proliferation produces clinical signs and symptoms.

Postoperative abdominal wound infection occurs in about 5% of cases but may be more common in procedures that involve a greater level of contamination.7 One study found a 12% incidence of wound infection, but the rate declined to 8% when antibiotic prophylaxis was instituted.4

Several other studies have examined determinants of infection. For example, a large Cochrane review found no real differences in infection rate by preoperative skin preparation technique or agent, but it did observe that one study had demonstrated the superiority of chlorhexidine to other cleansing agents.8

Cruse and Foord also noted the slight superiority of chlorhexidine, as well as the efficacy of clipping abdominal hair immediately before surgery.7

When identifying organisms, look for the usual suspects

The offending pathogens in infection are usually endogenous flora found on the patient’s skin and within hollow organs (vagina, bowel). The organisms most commonly responsible for infection are Staphylococcus (aureus, epidermidis), enterococci, and Escherichia coli. However, the bacteria identified in the wound may not be the causative organism.

Most infections typically become clinically apparent between the fifth and 10th postoperative days, often after the patient has been discharged, although they may appear much earlier or much later. One of us (Dr. Perkins) had a patient who presented with a suppurative infection after undergoing hysterectomy for endometrial carcinoma 5 months earlier.

Cellulitis is common

Wound cellulitis, a common, nonsuppurative infection of skin and underlying connective tissue, is generally not severe. The wound assumes a brawny, reddish brown appearance associated with edema, warmth, and erythema. Fever is not always present.

It is important to remember that cellulitis may surround a deeper infection. Although needle aspiration of the leading edge has been advocated, it yields a positive culture in only 20% to 40% of cases.

In the absence of purulent drainage, treat cellulitis with antibiotics, utilizing sulfamethoxazole-trimethroprim, a cephalosporin, or augmented penicillin, and apply warm packs to the wound.

If purulent drainage is seen, or the patient fails to improve significantly within 24 hours, suspect an abscess or resistant organism.

- During preoperative evaluation, assess the patient for risk factors, comorbid conditions, and medications that can impair healing

- If the patient is morbidly obese and planning to undergo an elective, nonurgent procedure, consider instituting a plan for preoperative weight loss

- Advise smokers to “kick the habit” 1 or 2 months before surgery

- Avoid using electrocautery in the “coagulation current” setting when incising the fascia

- When approximating the fascia, take wide bites of tissue (1.5 to 2 cm from the edge)

- Avoid excessive suture tension when closing the fascial layer (“Approximate, don’t strangulate”)

- Obtain good hemostasis before closing the wound; consider placing a drain in an obese patient

- In a high-risk patient who has multiple risk factors, consider retention sutures

- Minimize or avoid abdominal distention during the postoperative period with:

- Assess the wound for infection early, and treat infection promptly

- Remember to administer prophylactic antibiotics

Most wound infections are superficial

Approximately 75% of all wound infections involve the skin and subcutaneous tissue layers. Superficial infection is more likely to occur when there is an undrained hematoma, excessively tight sutures, tissue trauma, or a retained foreign material. Edema, erythema, and pain and tenderness may be more pronounced than with cellulitis. A low-grade fever may be present, and incisional discharge typically occurs.

Drainage is the cornerstone of management and requires the removal of staples or sutures from the area. Local exploration is mandatory, and fascial integrity must be confirmed. If a pocket of pus is found, open the wound liberally to determine the extent of the pocket and permit as much evacuation as possible. Wound culture is optional. Institute local wound care and consider adjuvant antibiotics in selected cases.

Ensure fascial integrity

Any infection that arises immediately adjacent to the fascia may have an intra-abdominal component, although that is unlikely. Extensive exploration is warranted to assess fascial integrity.

If intra-abdominal infection is suspected, order appropriate imaging.

Patients who have deep infection usually exhibit frank, purulent discharge; fever; and severe pain. Marked separation of wound edges is often present as well, as is an elevated white blood cell count.

As with superficial infection, the key to therapy is liberal exploration, drainage of the abscess cavity, and mechanical wound debridement. Irrigate the wound copiously using a dilute mixture of saline and hydrogen peroxide to remove any remaining debris. Avoid povidone-iodine solution because it inhibits normal tissue granulation.

The wound may be left open to heal by secondary intention, or it may be closed secondarily after 3 to 6 days, provided there is no evidence of infection and a healthy granulating bed is present.

Consider adjuvant antibiotics, especially when the patient is immunocompromised.

If the wound has pronounced edema and unusual discoloration, consider a serious infection such as necrotizing fasciitis.

Wound dehiscence raises risk of evisceration

Dehiscence of the abdominal incision occurs when the various layers separate. Dehiscence may be extrafascial (superficial disruption of the skin and subcutaneous tissue only) or may involve all layers, including peritoneum (complete fascial dehiscence or burst abdomen).

When bowel or omentum extrudes, the term evisceration is appropriate.

In several reviews of the literature, the incidence of dehiscence ranged from 0.4% in earlier studies to 1% to 3% in later reviews.9-12 Despite advances in preoperative and postoperative care, suture materials, surgical technique, and antibiotics, fascial dehiscence remains a serious problem in abdominal surgery.

What causes wound disruption?

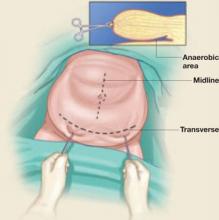

To a great extent, abdominal wound breakdown is a function of surgical technique and method of closure. Although the conventional wisdom is that dehiscence occurs less frequently with a transverse incision than with a vertical one, this assumption is being challenged. A small study by Hendrix and associates found no differences in the rate of dehiscence by type of incision.13 That finding suggests that the incidence of dehiscence is inversely related to the strength of closure.

Selection of the appropriate suture material also is important. In addition, use of electrocautery in the “cutting current” mode when the abdomen is opened causes less tissue injury than “coagulation current.” The latter has a greater thermal effect, thereby weakening the fascial layer.

Patient characteristics that influence wound integrity include comorbidities such as diabetes and malignancy, recent corticosteroid administration, and malnutrition.

Although infection may accompany superficial wound separation, its role in complete dehiscence is unclear.

Conditions that cause abdominal distention, such as severe coughing, vomiting, ileus, and ascites, may contribute to dehiscence, particularly when the closure method is less than satisfactory.

Some authors have found a greater incidence of wound disruption when multiple risk factors are present. In patients who had eight or more risk factors, wound disruption was universal.11,12

Management entails debridement, irrigation, and closure

When extrafascial dehiscence occurs, mechanical debridement and irrigation are usually the only measures necessary before deciding how to close the wound—even if infection is present. Remove all foreign material and excise any devitalized tissue.

As for the method of closure, the choice is usually between secondary closure and leaving the wound open to heal by secondary intention. An alternative to the latter is wound closure after several days, once a healthy granulating bed develops.

Dodson and colleagues described a technique of superficial wound closure that can be performed at the bedside using local anesthesia, with little discomfort to the patient.14 Wound separation caused by a small hematoma or sterile seroma especially lends itself to this type of immediate closure.

Vacuum-assisted closure

The vacuum-assisted wound closure system is a device that speeds healing and reduces the risk of complication. It consists of a sponge dressing that can be sized to fit an open wound and connected to an apparatus that generates negative pressure. The device enhances healing by removing excess fluid and debris and decreasing wound edema.

Argenta and associates reported successful use of this system to expedite healing in three cases of wound failure.16 It can be employed in the home-health setting by nurses trained in its use.

Human acellular dermal matrix

Occasionally, breakdown of a wound creates marked fascial defects that preclude secondary closure. Synthetic materials—both absorbable and nonabsorbable varieties—have been employed to bridge the defect, but their use sometimes leads to adhesions, infection, and cutaneous fistula. These risks are of special concern when the wound is already contaminated or otherwise compromised.

One alternative is human acellular dermal matrix (AlloDerm, LifeCell Corp). Tung and colleagues described its use for repair of a fascial defect in a previously irradiated cancer patient whose postoperative course was complicated by pelvic infection.17 This dermal matrix, a basement membrane taken from cadaveric skin, promotes neovascularization and is thought to be associated with a lower incidence of infection and adhesions than is traditional mesh. It is widely used in the burn setting and in the repair of ventral hernia, but is a relatively new addition to the management of fascial defects associated with wound breakdown.

Growth factors

Wound healing is regulated by a number of entities, including cytokines and growth factors, so it is no surprise that research has turned its focus on them. In a preliminary study, investigators found that separated abdominal wounds closed faster when recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor BB was topically administered than they did when they were left open to close by secondary intention.18

Although their use is not commonplace in wound management, research suggests that growth factors may one day be helpful adjuncts in the care of wound complications.

Complete fascial dehiscence is a “catastrophic” complication

Complete dehiscence of the fascia and extrusion of intra-abdominal contents is a serious catastrophic complication that is associated with a mortality rate of about 20%. It typically occurs between the third and seventh postoperative days, although later occurrences have been reported.

Warning signs of impending evisceration include serous drainage in the absence of obvious infection, and a “popping” sensation on the part of the patient—a feeling that something is “giving way.”

If evisceration occurs, cover exposed bowel with packs soaked in saline or povidone-iodine and prepare the patient for emergency surgery. Institute both hydration and broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Before replacing the abdominal contents, thoroughly irrigate the peritoneal cavity and inspect the bowel carefully, excising any necrotic tissue.

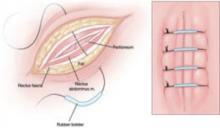

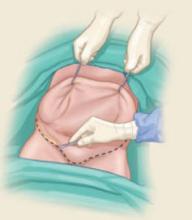

Reapproximate the fascia using interrupted #1 or #2 monofilament suture. Also consider placing retention sutures, particularly when the patient has multiple risk factors for wound complications (FIGURE). Leave the wound open, prepared for later closure.

If the abdomen cannot be closed because of peritonitis or bowel edema, or there is an insufficient amount of fascia remaining, approximate the abdominal wall using bridging sutures over a gauze pack as a temporizing measure until reconstruction can be performed. Consultation with a plastic surgeon or trauma specialist is recommended.

FIGURE Consider retention sutures for high-risk patients

Retention sutures are placed in interrupted fashion to support the primary suture line and are carried through the full thickness of the tissue, from the abdominal wall skin through the fascia and, if possible, the peritoneum. A rubber bolster placed across each suture keeps the suture from cutting into the skin (inset).

Necrotizing fasciitis: Worst of the worst

Necrotizing fasciitis is a dangerous, synergistic, bacterial infection involving the fascia, subcutaneous tissue, and skin. The culprits are multiple bacterial pathogens that include Streptococcus pyogenes, staphylococcal species, gram-negative aerobes, and anaerobes. The infection typically originates at a localized area, spreads along the fascial planes, and ultimately causes septic thrombosis of the vessels penetrating the skin and deeper layers. The result is necrosis. The associated mortality rate is approximately 20%.

The patient who has necrotizing fasciitis typically displays severe pain; anesthetic, edematous skin; purple, necrotic wound edges; hemorrhagic bullae; and crepitus.

Frank necrosis subsequently develops, with surrounding inflammation and edema, and leads to systemic toxicity, with fever, hemodynamic abnormality, and shock. In advanced stages, gangrene is present.

Laboratory evaluation includes a white blood cell count. Biopsy also is recommended. If necrotizing fasciitis is present, biopsy will reveal necrosis and thrombi of vessels passing through the fascia.

Treatment of necrotizing fasciitis requires intravenous, broad-spectrum antibiotics, including penicillin, that are adjusted according to the findings of the wound culture and sensitivity test. Cardiovascular and fluid-volume support is critical, as is wide surgical debridement of all necrosed skin and fascia. The latter, in fact, is the cornerstone of therapy.

1. Lin L, Song J, Kimber N, et al. The role of bacterial vaginosis in infection after major gynecologic surgery. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1999;7:169-174.

2. Williams JZ, Barbul A. Nutrition and wound healing. Surg Clin North Am. 2003;83:571-596.

3. Perkins JD, Jackson RA. Risks and remedies when your surgical patient is obese. OBG Management. 2007;19(10)34-54.

4. Kamat AA, Brancazio L, Gibson M. Wound infection in gynecologic surgery. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2000;8:230-234.

5. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Antibiotic prophylaxis for gynecologic procedures. ACOG Practice Bulletin #104. Washington, DC: ACOG; 2009.

6. Gallup DC, Gallup DG, Nolan TE, Smith RP, Messing MF, Kline KL. Use of a subcutaneous closed drainage system and antibiotics in obese gynecologic patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:358-362.

7. Cruse PJE, Foord R. The epidemiology of wound infection. A 10-year prospective study of 62,639 wounds. Surg Clin North Am. 1980;60:27-40.

8. Edwards PS, Lipp A, Holmes A. Preoperative skin antiseptics for preventing surgical wound infections after clean surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD003949.-

9. Baggish MS, Lee WK. Abdominal wound disruption. Obstet Gynecol. 1975;46:530-534.

10. Poole GV, Jr. Mechanical factors in abdominal wound closure: the prevention of fascial dehiscence. Surgery. 1985;97:631-640.

11. Carlson MA. Acute wound failure. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77:607-636.

12. Cliby WA. Abdominal incision wound breakdown. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;45:507-517.

13. Hendrix SL, Schimp V, Martin J, Singh A, Kruger M, McNeeley SG. The legendary superior strength of the Pfannenstiel incision: a myth? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:1446-1451.

14. Dodson MK, Magann EF, Sullivan DL, Meeks GR. Extrafascial wound dehiscence: deep en bloc closure versus superficial skin closure. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:142-145.

15. Brunicardi FC, Andersen DK, Billiar TR, Dunn DL, Hunter JG, Pollock RE. Chapter 8: Wound healing. In: Schwartz’s Principles of Surgery. 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005.

16. Argenta PA, Rahaman J, Gretz HF, 3rd, Nezhat F, Cohen CJ. Vacuum-assisted closure in the treatment of complex gynecologic wound failures. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:497-501.

17. Tung CS, Zighelboim I, Scott B, Anderson ML. Human acellular dermal matrix for closure of a contaminated gynecologic wound. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103:354-356.

18. Shackelford DP, Fackler E, Hoffman MK, Atkinson S. Use of topical recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor BB in abdominal wound separation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:701-704.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Despite advances in medicine and surgery over the past century, postoperative wound complication remains a serious challenge. When a complication occurs, it translates into prolonged hospitalization, lost time from work, and greater cost to the patient and the health-care system.

Prevention of wound complication begins well before surgery. Requirements include:

- understanding of wound healing (see below) and the classification of wounds (TABLE 1)

- thorough assessment of the patient for risk factors for impaired wound healing, such as diabetes or use of corticosteroid medication (TABLE 2)

- antibiotic prophylaxis, if indicated (TABLE 3)

- good surgical technique, gentle tissue handling, and meticulous hemostasis

- placement of a drain, when appropriate

- awareness of technology that can enhance healing

- close monitoring in the postoperative period

- intervention at the first hint of abnormality.

In this article, we describe predisposing factors and preventive techniques and measures, and outline the most common wound complications, from seroma to dehiscence, including effective management strategies.

It was pioneering Scottish surgeon John Hunter who noted that “injury alone has in all cases the tendency to produce the disposition and means of a cure.”15

Unlike the tissue regeneration that occurs primarily in lower animals, human wound healing is mediated by collagen deposition, or scarring, which provides structural support to the wound. This scarring process may itself cause a variety of clinical problems.

Wound healing is characterized by overlapping, largely interdependent phases, with no clear demarcation between them. Failure in one phase may have a negative impact on the overall outcome.

In general, wound healing involves two phases: inflammation and proliferation. Within these phases, the following processes occur: scar maturation, wound contraction, and epithelialization. These repair mechanisms are activated in response to tissue injury even when it is surgically induced.

Inflammatory phase

The initial response to tissue injury is inflammation, which is mediated by various amines, enzymes, and other substances. This inflammation can be further broken down into vascular and cellular responses.

Inflammation triggers increased blood flow and migration of neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, and other cells into the wound.

The first burst of blood acts to cleanse the wound of foreign debris. It is followed by vasoconstriction, which is mediated by thromboxane 2, to decrease blood loss. Vasodilation then occurs once histamine and serotonin are released, permitting increased blood flow to the wound. The surge in blood flow accounts for the increased warmth and redness of the wound. Vasodilation also increases capillary permeability, allowing the migration of red blood cells, platelets, leukocytes, plasma, and other tissue fluids into the interstitium of the wound. This migration accounts for wound edema.

In the cellular response, which is facilitated by increased blood flow, cell migration occurs as part of an immune response. Neutrophils, the first cells to enter the wound, engage in phagocytosis of bacteria and debris. Subsequently, there is migration of monocytes, macrophages, and other cells. This nonspecific immune response is sustained by prostaglandins, aided by complement factors and cytokines. A specific immune response follows, aimed at destroying specific antigens, and involves both B- and T-lymphocytes.

Proliferative phase

Proliferation is characterized by the infiltration of endothelial cells and fibroblasts and subsequent collagen deposition along a previously formed fibrin network. This new, highly vascularized tissue assumes a granular appearance—hence, the term “granulation tissue.”

Collagen that is deposited in the wound undergoes maturation and remodeling, increasing the tensile strength of the wound. The process continues for months after the initial insult.

All wounds undergo some degree of contraction, but the process is more relevant in wounds that remain open or involve significant tissue loss.

Last, the external covering of the wound is restored by epithelialization.

TABLE 1

Classification of surgical wounds

| CLASS I – Clean wounds (infection rate <5%) |

|

| CLASS II – Clean–contaminated wounds (infection rate 2–10%) |

|

| CLASS III – Contaminated wounds (infection rate 15–20%) |

|

| CLASS IV – Dirty or infected wounds (infection rate >30%) |

|

| SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Surgeons |

TABLE 2

Risk factors for poor wound healing and dehiscence

| Poor wound healing |

|

| Abdominal wound dehiscence |

|

| SOURCE: Carlson,11 Cliby12. |

Conditions and drugs that impair healing

Preexisting medical conditions may limit healing, especially conditions associated with diminished delivery of oxygen and nutrients to healing tissues.

Diabetes can damage the vasculature and may impair healing if the blood glucose level is markedly elevated in the perioperative period. Such an elevation impedes transport of vitamin C, a key component of collagen synthesis.

Malignancy and immunosuppressive disorders may prevent optimal healing by compromising the immune response.

Bacterial vaginosis, a common polymicrobial infection involving aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, appears to be associated with postoperative febrile morbidity and surgical-site infection, particularly after hysterectomy.1 Current guidelines recommend that medical therapy for bacterial vaginosis be instituted at least 4 days before surgery and continued postoperatively.

Because steroids, NSAIDs, and chemotherapy agents impede wound healing, and anticoagulants may interfere with granulation, it is crucial to review the patient’s medications well in advance of surgery.

Nutrition plays a critical role

The importance of nutrition cannot be overstated. A significant percentage of patients are thought to have some degree of nutritional deficiency preoperatively. This deficiency may alter the inflammatory response, impair collagen synthesis, and reduce the tensile strength of the wound.

Because healing requires energy, deficits in carbohydrates may limit protein utilization, and deficiencies of vitamins and micronutrients can also interfere with healing.2

Obesity, too, increases the risk of postoperative wound complication. Markedly obese patients have a thick, avascular, subcutaneous layer of fat that compromises healing.3

Meticulous technique required

Good surgical technique and appropriate use of antibiotics are critical components of successful wound healing.

When placing the incision, avoid the moist, bacteria-laden subpannicular crease in the markedly obese.

During a procedure, handle tissue gently, keep it moist, and make minimal use of electrocautery to reduce tissue injury and promote healing. Keep operating time and blood loss to a minimum, and debride the wound of any foreign material and devitalized tissue.

Multiple studies have demonstrated that judicious use of prophylactic antibiotics significantly decreases the incidence of wound infection, particularly in relation to hysterectomy and vaginal procedures and when entry into bowel is anticipated.4,5 A number of prophylactic regimens are given in TABLE 3.

Meticulous hemostasis at the time of closure is imperative. When complete hemostasis cannot be confirmed, place a small drain in the subcutaneous space (or subfascial space, if there is oozing on the muscle bed) and apply a pressure dressing to help prevent hematoma. Although a drain is not a substitute for precise hemostasis or careful surgical technique, it may be helpful when there is concern about oozing or a “wet” surface, or when the patient is markedly obese.

Some practitioners have expressed concern over the risk of bacterial migration and infection with placement of a drain, but others, including us, advocate use of a drain in the subcutaneous space to help remove residual blood, fluid, and other debris to prevent the formation of dead space and infection and promote wound closure and healing. In a small study, Gallup and associates demonstrated a decreased incidence of wound breakdown when a drain was placed.6

A closed-suction drain, such as a Jackson-Pratt or Hemovac model, helps minimize wound complication when it is placed in the subcutaneous layer. (Avoid a rubber Penrose drain because it may allow bacteria to enter the wound.) It is imperative that the drain exit the body via a separate site and not through the incision itself. We advocate removal when less than 30 mL of fluid accumulates in the reservoir over 24 hours.

TABLE 3

3 prophylactic antibiotic regimens

| Procedure | Antibiotic | Single intravenous dose |

|---|---|---|

| Hysterectomy and urogynecologic procedures, including those that involve mesh | Cefazolin | 1 g or 2 g |

| Clindamycin plus gentamicin, a quinolone, or aztreonam | 600 mg plus 1.5 mg/kg, 400 mg, or 1 g, respectively | |

| Metronidazole plus gentamicin or a quinolone | 500 mg plus 1.5 mg/kg or 400 mg, respectively | |

| SOURCE: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists5 | ||

Fluid within the wound does not always indicate infection

Wound collections are not necessarily indicative of infection; collections of fluid within the wound may represent a serous transudate, blood, pus, or a combination of these. If the fluid is not addressed, however, fulminant infection may be the result.

Seroma is usually painless

A seroma is a collection of wound exudates within the dead space. Seroma typically involves thin, pink, watery discharge and minimal edge separation. In some cases, there may be surrounding edema but generally little to no tenderness.

When a seroma is detected, remove the staples or stitches in the area of concern and explore the wound. It is essential to ensure fascial integrity, as serous wound drainage may be a sign of impending evisceration. After these measures are taken, cleanse and lightly pack the wound to permit drainage.

Hematoma requires identification of the source of bleeding

Hematoma represents blood or a blood clot within the tissues beneath the skin. It may be caused by persistent bleeding of a vessel, although the pressure within the wound and the pressure produced by the dressing often provide tamponade on the bleeding source, in which case the hematoma forms with no active bleeding.

Hematoma is usually caused by small bleeding vessels that were not apparent at the time of surgery or were not cauterized or ligated at the time of closure. For this reason, it is important to achieve good hemostasis and a “dry” wound before closing the skin.

When hematoma is suspected, open the wound enough to permit adequate exposure and identify the source of bleeding. Evacuate as much blood and clot as possible because blood is an ideal medium for bacterial growth. If active bleeding is found, use a silver nitrate applicator or handheld cautery pen to accomplish hemostasis at bedside. If bleeding is more severe, or the source cannot be visualized, consider returning to the operating room for more extensive exploration.

Once hemostasis is achieved, irrigate the wound copiously and institute local wound care.

How common is infection?

Before it is possible to address this question, it is necessary to clarify the terminology of infection. Contamination and colonization are different entities. The first refers to the presence of bacteria without multiplication. The latter describes the multiplication of bacteria in the absence of a host response. When infection is present, bacterial proliferation produces clinical signs and symptoms.

Postoperative abdominal wound infection occurs in about 5% of cases but may be more common in procedures that involve a greater level of contamination.7 One study found a 12% incidence of wound infection, but the rate declined to 8% when antibiotic prophylaxis was instituted.4

Several other studies have examined determinants of infection. For example, a large Cochrane review found no real differences in infection rate by preoperative skin preparation technique or agent, but it did observe that one study had demonstrated the superiority of chlorhexidine to other cleansing agents.8

Cruse and Foord also noted the slight superiority of chlorhexidine, as well as the efficacy of clipping abdominal hair immediately before surgery.7

When identifying organisms, look for the usual suspects

The offending pathogens in infection are usually endogenous flora found on the patient’s skin and within hollow organs (vagina, bowel). The organisms most commonly responsible for infection are Staphylococcus (aureus, epidermidis), enterococci, and Escherichia coli. However, the bacteria identified in the wound may not be the causative organism.

Most infections typically become clinically apparent between the fifth and 10th postoperative days, often after the patient has been discharged, although they may appear much earlier or much later. One of us (Dr. Perkins) had a patient who presented with a suppurative infection after undergoing hysterectomy for endometrial carcinoma 5 months earlier.

Cellulitis is common

Wound cellulitis, a common, nonsuppurative infection of skin and underlying connective tissue, is generally not severe. The wound assumes a brawny, reddish brown appearance associated with edema, warmth, and erythema. Fever is not always present.

It is important to remember that cellulitis may surround a deeper infection. Although needle aspiration of the leading edge has been advocated, it yields a positive culture in only 20% to 40% of cases.

In the absence of purulent drainage, treat cellulitis with antibiotics, utilizing sulfamethoxazole-trimethroprim, a cephalosporin, or augmented penicillin, and apply warm packs to the wound.

If purulent drainage is seen, or the patient fails to improve significantly within 24 hours, suspect an abscess or resistant organism.

- During preoperative evaluation, assess the patient for risk factors, comorbid conditions, and medications that can impair healing

- If the patient is morbidly obese and planning to undergo an elective, nonurgent procedure, consider instituting a plan for preoperative weight loss

- Advise smokers to “kick the habit” 1 or 2 months before surgery

- Avoid using electrocautery in the “coagulation current” setting when incising the fascia

- When approximating the fascia, take wide bites of tissue (1.5 to 2 cm from the edge)

- Avoid excessive suture tension when closing the fascial layer (“Approximate, don’t strangulate”)

- Obtain good hemostasis before closing the wound; consider placing a drain in an obese patient

- In a high-risk patient who has multiple risk factors, consider retention sutures

- Minimize or avoid abdominal distention during the postoperative period with:

- Assess the wound for infection early, and treat infection promptly

- Remember to administer prophylactic antibiotics

Most wound infections are superficial

Approximately 75% of all wound infections involve the skin and subcutaneous tissue layers. Superficial infection is more likely to occur when there is an undrained hematoma, excessively tight sutures, tissue trauma, or a retained foreign material. Edema, erythema, and pain and tenderness may be more pronounced than with cellulitis. A low-grade fever may be present, and incisional discharge typically occurs.

Drainage is the cornerstone of management and requires the removal of staples or sutures from the area. Local exploration is mandatory, and fascial integrity must be confirmed. If a pocket of pus is found, open the wound liberally to determine the extent of the pocket and permit as much evacuation as possible. Wound culture is optional. Institute local wound care and consider adjuvant antibiotics in selected cases.

Ensure fascial integrity

Any infection that arises immediately adjacent to the fascia may have an intra-abdominal component, although that is unlikely. Extensive exploration is warranted to assess fascial integrity.

If intra-abdominal infection is suspected, order appropriate imaging.

Patients who have deep infection usually exhibit frank, purulent discharge; fever; and severe pain. Marked separation of wound edges is often present as well, as is an elevated white blood cell count.

As with superficial infection, the key to therapy is liberal exploration, drainage of the abscess cavity, and mechanical wound debridement. Irrigate the wound copiously using a dilute mixture of saline and hydrogen peroxide to remove any remaining debris. Avoid povidone-iodine solution because it inhibits normal tissue granulation.

The wound may be left open to heal by secondary intention, or it may be closed secondarily after 3 to 6 days, provided there is no evidence of infection and a healthy granulating bed is present.

Consider adjuvant antibiotics, especially when the patient is immunocompromised.

If the wound has pronounced edema and unusual discoloration, consider a serious infection such as necrotizing fasciitis.

Wound dehiscence raises risk of evisceration

Dehiscence of the abdominal incision occurs when the various layers separate. Dehiscence may be extrafascial (superficial disruption of the skin and subcutaneous tissue only) or may involve all layers, including peritoneum (complete fascial dehiscence or burst abdomen).

When bowel or omentum extrudes, the term evisceration is appropriate.

In several reviews of the literature, the incidence of dehiscence ranged from 0.4% in earlier studies to 1% to 3% in later reviews.9-12 Despite advances in preoperative and postoperative care, suture materials, surgical technique, and antibiotics, fascial dehiscence remains a serious problem in abdominal surgery.

What causes wound disruption?

To a great extent, abdominal wound breakdown is a function of surgical technique and method of closure. Although the conventional wisdom is that dehiscence occurs less frequently with a transverse incision than with a vertical one, this assumption is being challenged. A small study by Hendrix and associates found no differences in the rate of dehiscence by type of incision.13 That finding suggests that the incidence of dehiscence is inversely related to the strength of closure.

Selection of the appropriate suture material also is important. In addition, use of electrocautery in the “cutting current” mode when the abdomen is opened causes less tissue injury than “coagulation current.” The latter has a greater thermal effect, thereby weakening the fascial layer.

Patient characteristics that influence wound integrity include comorbidities such as diabetes and malignancy, recent corticosteroid administration, and malnutrition.

Although infection may accompany superficial wound separation, its role in complete dehiscence is unclear.

Conditions that cause abdominal distention, such as severe coughing, vomiting, ileus, and ascites, may contribute to dehiscence, particularly when the closure method is less than satisfactory.

Some authors have found a greater incidence of wound disruption when multiple risk factors are present. In patients who had eight or more risk factors, wound disruption was universal.11,12

Management entails debridement, irrigation, and closure

When extrafascial dehiscence occurs, mechanical debridement and irrigation are usually the only measures necessary before deciding how to close the wound—even if infection is present. Remove all foreign material and excise any devitalized tissue.

As for the method of closure, the choice is usually between secondary closure and leaving the wound open to heal by secondary intention. An alternative to the latter is wound closure after several days, once a healthy granulating bed develops.

Dodson and colleagues described a technique of superficial wound closure that can be performed at the bedside using local anesthesia, with little discomfort to the patient.14 Wound separation caused by a small hematoma or sterile seroma especially lends itself to this type of immediate closure.

Vacuum-assisted closure

The vacuum-assisted wound closure system is a device that speeds healing and reduces the risk of complication. It consists of a sponge dressing that can be sized to fit an open wound and connected to an apparatus that generates negative pressure. The device enhances healing by removing excess fluid and debris and decreasing wound edema.

Argenta and associates reported successful use of this system to expedite healing in three cases of wound failure.16 It can be employed in the home-health setting by nurses trained in its use.

Human acellular dermal matrix

Occasionally, breakdown of a wound creates marked fascial defects that preclude secondary closure. Synthetic materials—both absorbable and nonabsorbable varieties—have been employed to bridge the defect, but their use sometimes leads to adhesions, infection, and cutaneous fistula. These risks are of special concern when the wound is already contaminated or otherwise compromised.

One alternative is human acellular dermal matrix (AlloDerm, LifeCell Corp). Tung and colleagues described its use for repair of a fascial defect in a previously irradiated cancer patient whose postoperative course was complicated by pelvic infection.17 This dermal matrix, a basement membrane taken from cadaveric skin, promotes neovascularization and is thought to be associated with a lower incidence of infection and adhesions than is traditional mesh. It is widely used in the burn setting and in the repair of ventral hernia, but is a relatively new addition to the management of fascial defects associated with wound breakdown.

Growth factors

Wound healing is regulated by a number of entities, including cytokines and growth factors, so it is no surprise that research has turned its focus on them. In a preliminary study, investigators found that separated abdominal wounds closed faster when recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor BB was topically administered than they did when they were left open to close by secondary intention.18

Although their use is not commonplace in wound management, research suggests that growth factors may one day be helpful adjuncts in the care of wound complications.

Complete fascial dehiscence is a “catastrophic” complication

Complete dehiscence of the fascia and extrusion of intra-abdominal contents is a serious catastrophic complication that is associated with a mortality rate of about 20%. It typically occurs between the third and seventh postoperative days, although later occurrences have been reported.

Warning signs of impending evisceration include serous drainage in the absence of obvious infection, and a “popping” sensation on the part of the patient—a feeling that something is “giving way.”

If evisceration occurs, cover exposed bowel with packs soaked in saline or povidone-iodine and prepare the patient for emergency surgery. Institute both hydration and broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Before replacing the abdominal contents, thoroughly irrigate the peritoneal cavity and inspect the bowel carefully, excising any necrotic tissue.

Reapproximate the fascia using interrupted #1 or #2 monofilament suture. Also consider placing retention sutures, particularly when the patient has multiple risk factors for wound complications (FIGURE). Leave the wound open, prepared for later closure.

If the abdomen cannot be closed because of peritonitis or bowel edema, or there is an insufficient amount of fascia remaining, approximate the abdominal wall using bridging sutures over a gauze pack as a temporizing measure until reconstruction can be performed. Consultation with a plastic surgeon or trauma specialist is recommended.

FIGURE Consider retention sutures for high-risk patients

Retention sutures are placed in interrupted fashion to support the primary suture line and are carried through the full thickness of the tissue, from the abdominal wall skin through the fascia and, if possible, the peritoneum. A rubber bolster placed across each suture keeps the suture from cutting into the skin (inset).

Necrotizing fasciitis: Worst of the worst

Necrotizing fasciitis is a dangerous, synergistic, bacterial infection involving the fascia, subcutaneous tissue, and skin. The culprits are multiple bacterial pathogens that include Streptococcus pyogenes, staphylococcal species, gram-negative aerobes, and anaerobes. The infection typically originates at a localized area, spreads along the fascial planes, and ultimately causes septic thrombosis of the vessels penetrating the skin and deeper layers. The result is necrosis. The associated mortality rate is approximately 20%.

The patient who has necrotizing fasciitis typically displays severe pain; anesthetic, edematous skin; purple, necrotic wound edges; hemorrhagic bullae; and crepitus.

Frank necrosis subsequently develops, with surrounding inflammation and edema, and leads to systemic toxicity, with fever, hemodynamic abnormality, and shock. In advanced stages, gangrene is present.

Laboratory evaluation includes a white blood cell count. Biopsy also is recommended. If necrotizing fasciitis is present, biopsy will reveal necrosis and thrombi of vessels passing through the fascia.

Treatment of necrotizing fasciitis requires intravenous, broad-spectrum antibiotics, including penicillin, that are adjusted according to the findings of the wound culture and sensitivity test. Cardiovascular and fluid-volume support is critical, as is wide surgical debridement of all necrosed skin and fascia. The latter, in fact, is the cornerstone of therapy.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Despite advances in medicine and surgery over the past century, postoperative wound complication remains a serious challenge. When a complication occurs, it translates into prolonged hospitalization, lost time from work, and greater cost to the patient and the health-care system.

Prevention of wound complication begins well before surgery. Requirements include:

- understanding of wound healing (see below) and the classification of wounds (TABLE 1)

- thorough assessment of the patient for risk factors for impaired wound healing, such as diabetes or use of corticosteroid medication (TABLE 2)

- antibiotic prophylaxis, if indicated (TABLE 3)

- good surgical technique, gentle tissue handling, and meticulous hemostasis

- placement of a drain, when appropriate

- awareness of technology that can enhance healing

- close monitoring in the postoperative period

- intervention at the first hint of abnormality.

In this article, we describe predisposing factors and preventive techniques and measures, and outline the most common wound complications, from seroma to dehiscence, including effective management strategies.

It was pioneering Scottish surgeon John Hunter who noted that “injury alone has in all cases the tendency to produce the disposition and means of a cure.”15

Unlike the tissue regeneration that occurs primarily in lower animals, human wound healing is mediated by collagen deposition, or scarring, which provides structural support to the wound. This scarring process may itself cause a variety of clinical problems.

Wound healing is characterized by overlapping, largely interdependent phases, with no clear demarcation between them. Failure in one phase may have a negative impact on the overall outcome.

In general, wound healing involves two phases: inflammation and proliferation. Within these phases, the following processes occur: scar maturation, wound contraction, and epithelialization. These repair mechanisms are activated in response to tissue injury even when it is surgically induced.

Inflammatory phase

The initial response to tissue injury is inflammation, which is mediated by various amines, enzymes, and other substances. This inflammation can be further broken down into vascular and cellular responses.

Inflammation triggers increased blood flow and migration of neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, and other cells into the wound.

The first burst of blood acts to cleanse the wound of foreign debris. It is followed by vasoconstriction, which is mediated by thromboxane 2, to decrease blood loss. Vasodilation then occurs once histamine and serotonin are released, permitting increased blood flow to the wound. The surge in blood flow accounts for the increased warmth and redness of the wound. Vasodilation also increases capillary permeability, allowing the migration of red blood cells, platelets, leukocytes, plasma, and other tissue fluids into the interstitium of the wound. This migration accounts for wound edema.

In the cellular response, which is facilitated by increased blood flow, cell migration occurs as part of an immune response. Neutrophils, the first cells to enter the wound, engage in phagocytosis of bacteria and debris. Subsequently, there is migration of monocytes, macrophages, and other cells. This nonspecific immune response is sustained by prostaglandins, aided by complement factors and cytokines. A specific immune response follows, aimed at destroying specific antigens, and involves both B- and T-lymphocytes.

Proliferative phase

Proliferation is characterized by the infiltration of endothelial cells and fibroblasts and subsequent collagen deposition along a previously formed fibrin network. This new, highly vascularized tissue assumes a granular appearance—hence, the term “granulation tissue.”

Collagen that is deposited in the wound undergoes maturation and remodeling, increasing the tensile strength of the wound. The process continues for months after the initial insult.

All wounds undergo some degree of contraction, but the process is more relevant in wounds that remain open or involve significant tissue loss.

Last, the external covering of the wound is restored by epithelialization.

TABLE 1

Classification of surgical wounds

| CLASS I – Clean wounds (infection rate <5%) |

|

| CLASS II – Clean–contaminated wounds (infection rate 2–10%) |

|

| CLASS III – Contaminated wounds (infection rate 15–20%) |

|

| CLASS IV – Dirty or infected wounds (infection rate >30%) |

|

| SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Surgeons |

TABLE 2

Risk factors for poor wound healing and dehiscence

| Poor wound healing |

|

| Abdominal wound dehiscence |

|

| SOURCE: Carlson,11 Cliby12. |

Conditions and drugs that impair healing

Preexisting medical conditions may limit healing, especially conditions associated with diminished delivery of oxygen and nutrients to healing tissues.

Diabetes can damage the vasculature and may impair healing if the blood glucose level is markedly elevated in the perioperative period. Such an elevation impedes transport of vitamin C, a key component of collagen synthesis.

Malignancy and immunosuppressive disorders may prevent optimal healing by compromising the immune response.

Bacterial vaginosis, a common polymicrobial infection involving aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, appears to be associated with postoperative febrile morbidity and surgical-site infection, particularly after hysterectomy.1 Current guidelines recommend that medical therapy for bacterial vaginosis be instituted at least 4 days before surgery and continued postoperatively.

Because steroids, NSAIDs, and chemotherapy agents impede wound healing, and anticoagulants may interfere with granulation, it is crucial to review the patient’s medications well in advance of surgery.

Nutrition plays a critical role

The importance of nutrition cannot be overstated. A significant percentage of patients are thought to have some degree of nutritional deficiency preoperatively. This deficiency may alter the inflammatory response, impair collagen synthesis, and reduce the tensile strength of the wound.

Because healing requires energy, deficits in carbohydrates may limit protein utilization, and deficiencies of vitamins and micronutrients can also interfere with healing.2

Obesity, too, increases the risk of postoperative wound complication. Markedly obese patients have a thick, avascular, subcutaneous layer of fat that compromises healing.3

Meticulous technique required

Good surgical technique and appropriate use of antibiotics are critical components of successful wound healing.

When placing the incision, avoid the moist, bacteria-laden subpannicular crease in the markedly obese.

During a procedure, handle tissue gently, keep it moist, and make minimal use of electrocautery to reduce tissue injury and promote healing. Keep operating time and blood loss to a minimum, and debride the wound of any foreign material and devitalized tissue.

Multiple studies have demonstrated that judicious use of prophylactic antibiotics significantly decreases the incidence of wound infection, particularly in relation to hysterectomy and vaginal procedures and when entry into bowel is anticipated.4,5 A number of prophylactic regimens are given in TABLE 3.

Meticulous hemostasis at the time of closure is imperative. When complete hemostasis cannot be confirmed, place a small drain in the subcutaneous space (or subfascial space, if there is oozing on the muscle bed) and apply a pressure dressing to help prevent hematoma. Although a drain is not a substitute for precise hemostasis or careful surgical technique, it may be helpful when there is concern about oozing or a “wet” surface, or when the patient is markedly obese.

Some practitioners have expressed concern over the risk of bacterial migration and infection with placement of a drain, but others, including us, advocate use of a drain in the subcutaneous space to help remove residual blood, fluid, and other debris to prevent the formation of dead space and infection and promote wound closure and healing. In a small study, Gallup and associates demonstrated a decreased incidence of wound breakdown when a drain was placed.6

A closed-suction drain, such as a Jackson-Pratt or Hemovac model, helps minimize wound complication when it is placed in the subcutaneous layer. (Avoid a rubber Penrose drain because it may allow bacteria to enter the wound.) It is imperative that the drain exit the body via a separate site and not through the incision itself. We advocate removal when less than 30 mL of fluid accumulates in the reservoir over 24 hours.

TABLE 3

3 prophylactic antibiotic regimens

| Procedure | Antibiotic | Single intravenous dose |

|---|---|---|

| Hysterectomy and urogynecologic procedures, including those that involve mesh | Cefazolin | 1 g or 2 g |

| Clindamycin plus gentamicin, a quinolone, or aztreonam | 600 mg plus 1.5 mg/kg, 400 mg, or 1 g, respectively | |

| Metronidazole plus gentamicin or a quinolone | 500 mg plus 1.5 mg/kg or 400 mg, respectively | |

| SOURCE: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists5 | ||

Fluid within the wound does not always indicate infection

Wound collections are not necessarily indicative of infection; collections of fluid within the wound may represent a serous transudate, blood, pus, or a combination of these. If the fluid is not addressed, however, fulminant infection may be the result.

Seroma is usually painless

A seroma is a collection of wound exudates within the dead space. Seroma typically involves thin, pink, watery discharge and minimal edge separation. In some cases, there may be surrounding edema but generally little to no tenderness.

When a seroma is detected, remove the staples or stitches in the area of concern and explore the wound. It is essential to ensure fascial integrity, as serous wound drainage may be a sign of impending evisceration. After these measures are taken, cleanse and lightly pack the wound to permit drainage.

Hematoma requires identification of the source of bleeding

Hematoma represents blood or a blood clot within the tissues beneath the skin. It may be caused by persistent bleeding of a vessel, although the pressure within the wound and the pressure produced by the dressing often provide tamponade on the bleeding source, in which case the hematoma forms with no active bleeding.

Hematoma is usually caused by small bleeding vessels that were not apparent at the time of surgery or were not cauterized or ligated at the time of closure. For this reason, it is important to achieve good hemostasis and a “dry” wound before closing the skin.

When hematoma is suspected, open the wound enough to permit adequate exposure and identify the source of bleeding. Evacuate as much blood and clot as possible because blood is an ideal medium for bacterial growth. If active bleeding is found, use a silver nitrate applicator or handheld cautery pen to accomplish hemostasis at bedside. If bleeding is more severe, or the source cannot be visualized, consider returning to the operating room for more extensive exploration.

Once hemostasis is achieved, irrigate the wound copiously and institute local wound care.

How common is infection?

Before it is possible to address this question, it is necessary to clarify the terminology of infection. Contamination and colonization are different entities. The first refers to the presence of bacteria without multiplication. The latter describes the multiplication of bacteria in the absence of a host response. When infection is present, bacterial proliferation produces clinical signs and symptoms.

Postoperative abdominal wound infection occurs in about 5% of cases but may be more common in procedures that involve a greater level of contamination.7 One study found a 12% incidence of wound infection, but the rate declined to 8% when antibiotic prophylaxis was instituted.4

Several other studies have examined determinants of infection. For example, a large Cochrane review found no real differences in infection rate by preoperative skin preparation technique or agent, but it did observe that one study had demonstrated the superiority of chlorhexidine to other cleansing agents.8

Cruse and Foord also noted the slight superiority of chlorhexidine, as well as the efficacy of clipping abdominal hair immediately before surgery.7

When identifying organisms, look for the usual suspects

The offending pathogens in infection are usually endogenous flora found on the patient’s skin and within hollow organs (vagina, bowel). The organisms most commonly responsible for infection are Staphylococcus (aureus, epidermidis), enterococci, and Escherichia coli. However, the bacteria identified in the wound may not be the causative organism.

Most infections typically become clinically apparent between the fifth and 10th postoperative days, often after the patient has been discharged, although they may appear much earlier or much later. One of us (Dr. Perkins) had a patient who presented with a suppurative infection after undergoing hysterectomy for endometrial carcinoma 5 months earlier.

Cellulitis is common

Wound cellulitis, a common, nonsuppurative infection of skin and underlying connective tissue, is generally not severe. The wound assumes a brawny, reddish brown appearance associated with edema, warmth, and erythema. Fever is not always present.

It is important to remember that cellulitis may surround a deeper infection. Although needle aspiration of the leading edge has been advocated, it yields a positive culture in only 20% to 40% of cases.

In the absence of purulent drainage, treat cellulitis with antibiotics, utilizing sulfamethoxazole-trimethroprim, a cephalosporin, or augmented penicillin, and apply warm packs to the wound.

If purulent drainage is seen, or the patient fails to improve significantly within 24 hours, suspect an abscess or resistant organism.

- During preoperative evaluation, assess the patient for risk factors, comorbid conditions, and medications that can impair healing

- If the patient is morbidly obese and planning to undergo an elective, nonurgent procedure, consider instituting a plan for preoperative weight loss

- Advise smokers to “kick the habit” 1 or 2 months before surgery

- Avoid using electrocautery in the “coagulation current” setting when incising the fascia

- When approximating the fascia, take wide bites of tissue (1.5 to 2 cm from the edge)

- Avoid excessive suture tension when closing the fascial layer (“Approximate, don’t strangulate”)

- Obtain good hemostasis before closing the wound; consider placing a drain in an obese patient

- In a high-risk patient who has multiple risk factors, consider retention sutures

- Minimize or avoid abdominal distention during the postoperative period with:

- Assess the wound for infection early, and treat infection promptly

- Remember to administer prophylactic antibiotics

Most wound infections are superficial

Approximately 75% of all wound infections involve the skin and subcutaneous tissue layers. Superficial infection is more likely to occur when there is an undrained hematoma, excessively tight sutures, tissue trauma, or a retained foreign material. Edema, erythema, and pain and tenderness may be more pronounced than with cellulitis. A low-grade fever may be present, and incisional discharge typically occurs.

Drainage is the cornerstone of management and requires the removal of staples or sutures from the area. Local exploration is mandatory, and fascial integrity must be confirmed. If a pocket of pus is found, open the wound liberally to determine the extent of the pocket and permit as much evacuation as possible. Wound culture is optional. Institute local wound care and consider adjuvant antibiotics in selected cases.

Ensure fascial integrity

Any infection that arises immediately adjacent to the fascia may have an intra-abdominal component, although that is unlikely. Extensive exploration is warranted to assess fascial integrity.

If intra-abdominal infection is suspected, order appropriate imaging.

Patients who have deep infection usually exhibit frank, purulent discharge; fever; and severe pain. Marked separation of wound edges is often present as well, as is an elevated white blood cell count.

As with superficial infection, the key to therapy is liberal exploration, drainage of the abscess cavity, and mechanical wound debridement. Irrigate the wound copiously using a dilute mixture of saline and hydrogen peroxide to remove any remaining debris. Avoid povidone-iodine solution because it inhibits normal tissue granulation.

The wound may be left open to heal by secondary intention, or it may be closed secondarily after 3 to 6 days, provided there is no evidence of infection and a healthy granulating bed is present.

Consider adjuvant antibiotics, especially when the patient is immunocompromised.

If the wound has pronounced edema and unusual discoloration, consider a serious infection such as necrotizing fasciitis.

Wound dehiscence raises risk of evisceration

Dehiscence of the abdominal incision occurs when the various layers separate. Dehiscence may be extrafascial (superficial disruption of the skin and subcutaneous tissue only) or may involve all layers, including peritoneum (complete fascial dehiscence or burst abdomen).

When bowel or omentum extrudes, the term evisceration is appropriate.

In several reviews of the literature, the incidence of dehiscence ranged from 0.4% in earlier studies to 1% to 3% in later reviews.9-12 Despite advances in preoperative and postoperative care, suture materials, surgical technique, and antibiotics, fascial dehiscence remains a serious problem in abdominal surgery.

What causes wound disruption?

To a great extent, abdominal wound breakdown is a function of surgical technique and method of closure. Although the conventional wisdom is that dehiscence occurs less frequently with a transverse incision than with a vertical one, this assumption is being challenged. A small study by Hendrix and associates found no differences in the rate of dehiscence by type of incision.13 That finding suggests that the incidence of dehiscence is inversely related to the strength of closure.

Selection of the appropriate suture material also is important. In addition, use of electrocautery in the “cutting current” mode when the abdomen is opened causes less tissue injury than “coagulation current.” The latter has a greater thermal effect, thereby weakening the fascial layer.

Patient characteristics that influence wound integrity include comorbidities such as diabetes and malignancy, recent corticosteroid administration, and malnutrition.

Although infection may accompany superficial wound separation, its role in complete dehiscence is unclear.

Conditions that cause abdominal distention, such as severe coughing, vomiting, ileus, and ascites, may contribute to dehiscence, particularly when the closure method is less than satisfactory.

Some authors have found a greater incidence of wound disruption when multiple risk factors are present. In patients who had eight or more risk factors, wound disruption was universal.11,12

Management entails debridement, irrigation, and closure

When extrafascial dehiscence occurs, mechanical debridement and irrigation are usually the only measures necessary before deciding how to close the wound—even if infection is present. Remove all foreign material and excise any devitalized tissue.

As for the method of closure, the choice is usually between secondary closure and leaving the wound open to heal by secondary intention. An alternative to the latter is wound closure after several days, once a healthy granulating bed develops.

Dodson and colleagues described a technique of superficial wound closure that can be performed at the bedside using local anesthesia, with little discomfort to the patient.14 Wound separation caused by a small hematoma or sterile seroma especially lends itself to this type of immediate closure.

Vacuum-assisted closure

The vacuum-assisted wound closure system is a device that speeds healing and reduces the risk of complication. It consists of a sponge dressing that can be sized to fit an open wound and connected to an apparatus that generates negative pressure. The device enhances healing by removing excess fluid and debris and decreasing wound edema.

Argenta and associates reported successful use of this system to expedite healing in three cases of wound failure.16 It can be employed in the home-health setting by nurses trained in its use.

Human acellular dermal matrix

Occasionally, breakdown of a wound creates marked fascial defects that preclude secondary closure. Synthetic materials—both absorbable and nonabsorbable varieties—have been employed to bridge the defect, but their use sometimes leads to adhesions, infection, and cutaneous fistula. These risks are of special concern when the wound is already contaminated or otherwise compromised.

One alternative is human acellular dermal matrix (AlloDerm, LifeCell Corp). Tung and colleagues described its use for repair of a fascial defect in a previously irradiated cancer patient whose postoperative course was complicated by pelvic infection.17 This dermal matrix, a basement membrane taken from cadaveric skin, promotes neovascularization and is thought to be associated with a lower incidence of infection and adhesions than is traditional mesh. It is widely used in the burn setting and in the repair of ventral hernia, but is a relatively new addition to the management of fascial defects associated with wound breakdown.

Growth factors

Wound healing is regulated by a number of entities, including cytokines and growth factors, so it is no surprise that research has turned its focus on them. In a preliminary study, investigators found that separated abdominal wounds closed faster when recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor BB was topically administered than they did when they were left open to close by secondary intention.18

Although their use is not commonplace in wound management, research suggests that growth factors may one day be helpful adjuncts in the care of wound complications.

Complete fascial dehiscence is a “catastrophic” complication

Complete dehiscence of the fascia and extrusion of intra-abdominal contents is a serious catastrophic complication that is associated with a mortality rate of about 20%. It typically occurs between the third and seventh postoperative days, although later occurrences have been reported.

Warning signs of impending evisceration include serous drainage in the absence of obvious infection, and a “popping” sensation on the part of the patient—a feeling that something is “giving way.”

If evisceration occurs, cover exposed bowel with packs soaked in saline or povidone-iodine and prepare the patient for emergency surgery. Institute both hydration and broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Before replacing the abdominal contents, thoroughly irrigate the peritoneal cavity and inspect the bowel carefully, excising any necrotic tissue.