User login

ACIP immunization update

Keeping up with the ever-changing immunization schedules recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) can be difficult. The most recent changes are the interim recommendations from the February 2011 ACIP meeting pertaining to tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine immunization and postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) for health care personnel. Updated schedules for routine immunization of children and adults that incorporate additions and changes made in the preceding year were published by the CDC in February.1,2

ACIP widens the scope of pertussis prevention

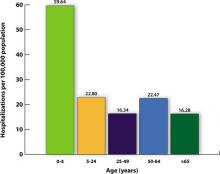

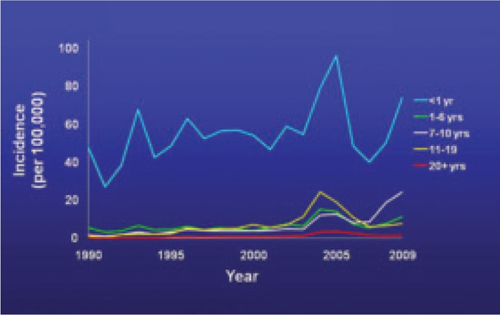

The past decade has seen an increase in pertussis cases, including an increase in the number of cases among infants and adolescents (FIGURE). In 2010, California reported 8383 cases, including 10 infant deaths. This was the highest number and rate of cases reported in more than 50 years.3 Other states have also experienced recent increases.

This evolving epidemiology of pertussis has prompted ACIP to recommend a routine single Tdap dose for adolescents between the ages of 11 and 18 years who have completed the recommended DTP/DTaP (diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and pertussis/diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis) vaccination series and for adults ages 19 to 64 years. ACIP also recommends a single dose for children ages 7 to 10 if they are not fully vaccinated against pertussis and for adults 65 and older who have not previously received Tdap and who are in close contact with infants. The last 2 are off-label recommendations. ACIP has also eliminated any recommended interval between the time of vaccination with tetanus or diphtheriatoxoid (Td) containing vaccine and the administration of Tdap.4

FIGURE

Reported pertussis incidence by age group, 1990-2009

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis (whooping cough): surveillance and reporting. Available at: www.cdc.gov/pertussis/surv-reporting.html. Accessed March 21, 2011.

2 new recommendations for clinician postexposure prophylaxis

Interim recommendations from the most recent ACIP meeting in February 20115 re-emphasize that health care personnel should receive Tdap and recommend that health care facilities take steps to increase adherence, including providing the vaccine at no cost.5

Since health care personnel are at increased risk of exposure to pertussis, ACIP also made 2 recommendations for PEP.

- All health care personnel (vaccinated or not) in close contact with a pertussis patient (as defined in TABLE 1) who are likely to expose patients at high risk for complications from pertussis (infants <1 year of age and those with certain immunodeficiency conditions, chronic lung disease, respiratory insufficiency, or cystic fibrosis) should receive PEP.

- Exposed personnel who do not work with high-risk patients should receive PEP or be monitored daily for 21 days, treated at first signs of infection, and excluded from patient contact for 5 days if symptoms develop. The antimicrobials and doses for treatment and prevention of pertussis have been published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.6 Options for PEP include azithromycin, clarithromycin, erythromycin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.6

TABLE 1

Definition of close contact with a pertussis patient

|

| Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005.6 |

Coming soon: Complete vaccine recommendations for health care workers

Recent experience with pertussis (and influenza) has highlighted the need for health care personnel to be vaccinated against infectious diseases to protect themselves, their patients, and their families. To that end, ACIP plans to publish a compendium later this year that brings together all recommendations regarding immunizations for health care personnel. When it becomes available, family physicians will be able to refer to this document to ensure that they and their staff are immunized in line with CDC recommendations.

The latest on influenza vaccine, PCV13, MCV4, hepatitis B, and HPV

The most notable additions to the routine schedules ACIP announced during the past year are universal, yearly influenza immunization from the age of 6 months on and the replacement of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) with a 13-valent product (PCV13) for infants and children. Details of these recommendations, including how to transition from PCV7 to PCV13, were published late last year by the CDC and described in another Practice Alert.7-9

In addition, changes were made in the schedules for meningococcal conjugate vaccine. A 2-dose primary series, instead of a single dose, of MCV4 is now recommended for those with compromised immunity. A booster of MCV4 is now recommended at age 16 for those vaccinated at 11 or 12 years, and at age 16 to 18 for those vaccinated at 13 to 15 years.10 The MCV4 recommendations are summarized in TABLE 2.

More schedule details in the footnotes. The new schedules contain a number of clarifications in the footnotes that:1,11

- explain the spacing of the 3-dose primary series for hepatitis B vaccine (HepB) for infants if they do not receive a dose immediately after birth

- clarify the circumstances in which children younger than age 9 need 2 doses of influenza vaccine

- describe the availability of both a quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV4) and a bivalent vaccine (HPV2) to prevent precancerous cervical lesions and cancer

- list the option for using HPV4 for males for the prevention of genital warts.

TABLE 2

Meningococcal conjugate vaccine recommendations by risk group, ACIP 2010

| Risk group | Primary series | Booster dose |

|---|---|---|

| Individuals ages 11-18 years | 1 dose, preferably at age 11 or 12 years |

|

| HIV-infected individuals ages 11-18 years | 2 doses, 2 months apart |

|

| Individuals ages 2-55 years with persistent complement component deficiency such as C5-C9, properdin, or factor D, or functional or anatomic asplenia | 2 doses, 2 months apart |

|

| Individuals ages 2-55 years with prolonged increased risk of exposure, such as microbiologists routinely working with Neisseria meningitidis and travelers to, or residents of, countries where meningococcal disease is hyperendemic or epidemic | 1 dose |

|

| Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011.10 | ||

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended immunization schedules for persons aged 0 through 18 years—United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep QuickGuide. 2011;60(5):1-4.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended adult immunization schedule-United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(4):1-4.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis (whooping cough): outbreaks. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/outbreaks.html. Accessed March 19, 2011.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(1):13-15.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ACIP presentation slides: February 2011 meeting. Available at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/acip/slides-feb11.htm#pertussis. Accessed March 19, 2011.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended antimicrobial agents for treatment and postexposure prophylaxis of pertussis: 2005 CDC guidelines. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54(RR-14):1-16.

7. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-8):1-62.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention of pneumococcal disease among infants and children—use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine—recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-11):1-18.

9. Campos-Outcalt D. Your guide to the new pneumococcal vaccine for children. J Fam Pract. 2010;59:394-398.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated recommendations for use of meningococcal conjugate vaccines—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:72-76.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FDA licensure of bivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV2, Cervarix) for use in females and updated HPV vaccination recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:626-629.

Keeping up with the ever-changing immunization schedules recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) can be difficult. The most recent changes are the interim recommendations from the February 2011 ACIP meeting pertaining to tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine immunization and postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) for health care personnel. Updated schedules for routine immunization of children and adults that incorporate additions and changes made in the preceding year were published by the CDC in February.1,2

ACIP widens the scope of pertussis prevention

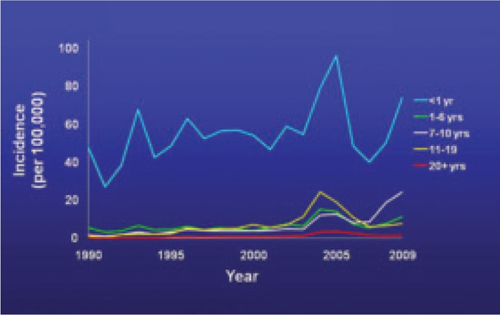

The past decade has seen an increase in pertussis cases, including an increase in the number of cases among infants and adolescents (FIGURE). In 2010, California reported 8383 cases, including 10 infant deaths. This was the highest number and rate of cases reported in more than 50 years.3 Other states have also experienced recent increases.

This evolving epidemiology of pertussis has prompted ACIP to recommend a routine single Tdap dose for adolescents between the ages of 11 and 18 years who have completed the recommended DTP/DTaP (diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and pertussis/diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis) vaccination series and for adults ages 19 to 64 years. ACIP also recommends a single dose for children ages 7 to 10 if they are not fully vaccinated against pertussis and for adults 65 and older who have not previously received Tdap and who are in close contact with infants. The last 2 are off-label recommendations. ACIP has also eliminated any recommended interval between the time of vaccination with tetanus or diphtheriatoxoid (Td) containing vaccine and the administration of Tdap.4

FIGURE

Reported pertussis incidence by age group, 1990-2009

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis (whooping cough): surveillance and reporting. Available at: www.cdc.gov/pertussis/surv-reporting.html. Accessed March 21, 2011.

2 new recommendations for clinician postexposure prophylaxis

Interim recommendations from the most recent ACIP meeting in February 20115 re-emphasize that health care personnel should receive Tdap and recommend that health care facilities take steps to increase adherence, including providing the vaccine at no cost.5

Since health care personnel are at increased risk of exposure to pertussis, ACIP also made 2 recommendations for PEP.

- All health care personnel (vaccinated or not) in close contact with a pertussis patient (as defined in TABLE 1) who are likely to expose patients at high risk for complications from pertussis (infants <1 year of age and those with certain immunodeficiency conditions, chronic lung disease, respiratory insufficiency, or cystic fibrosis) should receive PEP.

- Exposed personnel who do not work with high-risk patients should receive PEP or be monitored daily for 21 days, treated at first signs of infection, and excluded from patient contact for 5 days if symptoms develop. The antimicrobials and doses for treatment and prevention of pertussis have been published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.6 Options for PEP include azithromycin, clarithromycin, erythromycin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.6

TABLE 1

Definition of close contact with a pertussis patient

|

| Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005.6 |

Coming soon: Complete vaccine recommendations for health care workers

Recent experience with pertussis (and influenza) has highlighted the need for health care personnel to be vaccinated against infectious diseases to protect themselves, their patients, and their families. To that end, ACIP plans to publish a compendium later this year that brings together all recommendations regarding immunizations for health care personnel. When it becomes available, family physicians will be able to refer to this document to ensure that they and their staff are immunized in line with CDC recommendations.

The latest on influenza vaccine, PCV13, MCV4, hepatitis B, and HPV

The most notable additions to the routine schedules ACIP announced during the past year are universal, yearly influenza immunization from the age of 6 months on and the replacement of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) with a 13-valent product (PCV13) for infants and children. Details of these recommendations, including how to transition from PCV7 to PCV13, were published late last year by the CDC and described in another Practice Alert.7-9

In addition, changes were made in the schedules for meningococcal conjugate vaccine. A 2-dose primary series, instead of a single dose, of MCV4 is now recommended for those with compromised immunity. A booster of MCV4 is now recommended at age 16 for those vaccinated at 11 or 12 years, and at age 16 to 18 for those vaccinated at 13 to 15 years.10 The MCV4 recommendations are summarized in TABLE 2.

More schedule details in the footnotes. The new schedules contain a number of clarifications in the footnotes that:1,11

- explain the spacing of the 3-dose primary series for hepatitis B vaccine (HepB) for infants if they do not receive a dose immediately after birth

- clarify the circumstances in which children younger than age 9 need 2 doses of influenza vaccine

- describe the availability of both a quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV4) and a bivalent vaccine (HPV2) to prevent precancerous cervical lesions and cancer

- list the option for using HPV4 for males for the prevention of genital warts.

TABLE 2

Meningococcal conjugate vaccine recommendations by risk group, ACIP 2010

| Risk group | Primary series | Booster dose |

|---|---|---|

| Individuals ages 11-18 years | 1 dose, preferably at age 11 or 12 years |

|

| HIV-infected individuals ages 11-18 years | 2 doses, 2 months apart |

|

| Individuals ages 2-55 years with persistent complement component deficiency such as C5-C9, properdin, or factor D, or functional or anatomic asplenia | 2 doses, 2 months apart |

|

| Individuals ages 2-55 years with prolonged increased risk of exposure, such as microbiologists routinely working with Neisseria meningitidis and travelers to, or residents of, countries where meningococcal disease is hyperendemic or epidemic | 1 dose |

|

| Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011.10 | ||

Keeping up with the ever-changing immunization schedules recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) can be difficult. The most recent changes are the interim recommendations from the February 2011 ACIP meeting pertaining to tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine immunization and postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) for health care personnel. Updated schedules for routine immunization of children and adults that incorporate additions and changes made in the preceding year were published by the CDC in February.1,2

ACIP widens the scope of pertussis prevention

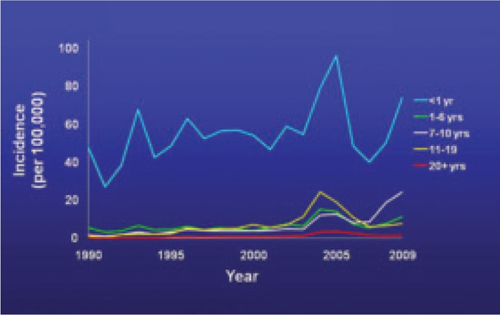

The past decade has seen an increase in pertussis cases, including an increase in the number of cases among infants and adolescents (FIGURE). In 2010, California reported 8383 cases, including 10 infant deaths. This was the highest number and rate of cases reported in more than 50 years.3 Other states have also experienced recent increases.

This evolving epidemiology of pertussis has prompted ACIP to recommend a routine single Tdap dose for adolescents between the ages of 11 and 18 years who have completed the recommended DTP/DTaP (diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and pertussis/diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis) vaccination series and for adults ages 19 to 64 years. ACIP also recommends a single dose for children ages 7 to 10 if they are not fully vaccinated against pertussis and for adults 65 and older who have not previously received Tdap and who are in close contact with infants. The last 2 are off-label recommendations. ACIP has also eliminated any recommended interval between the time of vaccination with tetanus or diphtheriatoxoid (Td) containing vaccine and the administration of Tdap.4

FIGURE

Reported pertussis incidence by age group, 1990-2009

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis (whooping cough): surveillance and reporting. Available at: www.cdc.gov/pertussis/surv-reporting.html. Accessed March 21, 2011.

2 new recommendations for clinician postexposure prophylaxis

Interim recommendations from the most recent ACIP meeting in February 20115 re-emphasize that health care personnel should receive Tdap and recommend that health care facilities take steps to increase adherence, including providing the vaccine at no cost.5

Since health care personnel are at increased risk of exposure to pertussis, ACIP also made 2 recommendations for PEP.

- All health care personnel (vaccinated or not) in close contact with a pertussis patient (as defined in TABLE 1) who are likely to expose patients at high risk for complications from pertussis (infants <1 year of age and those with certain immunodeficiency conditions, chronic lung disease, respiratory insufficiency, or cystic fibrosis) should receive PEP.

- Exposed personnel who do not work with high-risk patients should receive PEP or be monitored daily for 21 days, treated at first signs of infection, and excluded from patient contact for 5 days if symptoms develop. The antimicrobials and doses for treatment and prevention of pertussis have been published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.6 Options for PEP include azithromycin, clarithromycin, erythromycin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.6

TABLE 1

Definition of close contact with a pertussis patient

|

| Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005.6 |

Coming soon: Complete vaccine recommendations for health care workers

Recent experience with pertussis (and influenza) has highlighted the need for health care personnel to be vaccinated against infectious diseases to protect themselves, their patients, and their families. To that end, ACIP plans to publish a compendium later this year that brings together all recommendations regarding immunizations for health care personnel. When it becomes available, family physicians will be able to refer to this document to ensure that they and their staff are immunized in line with CDC recommendations.

The latest on influenza vaccine, PCV13, MCV4, hepatitis B, and HPV

The most notable additions to the routine schedules ACIP announced during the past year are universal, yearly influenza immunization from the age of 6 months on and the replacement of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) with a 13-valent product (PCV13) for infants and children. Details of these recommendations, including how to transition from PCV7 to PCV13, were published late last year by the CDC and described in another Practice Alert.7-9

In addition, changes were made in the schedules for meningococcal conjugate vaccine. A 2-dose primary series, instead of a single dose, of MCV4 is now recommended for those with compromised immunity. A booster of MCV4 is now recommended at age 16 for those vaccinated at 11 or 12 years, and at age 16 to 18 for those vaccinated at 13 to 15 years.10 The MCV4 recommendations are summarized in TABLE 2.

More schedule details in the footnotes. The new schedules contain a number of clarifications in the footnotes that:1,11

- explain the spacing of the 3-dose primary series for hepatitis B vaccine (HepB) for infants if they do not receive a dose immediately after birth

- clarify the circumstances in which children younger than age 9 need 2 doses of influenza vaccine

- describe the availability of both a quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV4) and a bivalent vaccine (HPV2) to prevent precancerous cervical lesions and cancer

- list the option for using HPV4 for males for the prevention of genital warts.

TABLE 2

Meningococcal conjugate vaccine recommendations by risk group, ACIP 2010

| Risk group | Primary series | Booster dose |

|---|---|---|

| Individuals ages 11-18 years | 1 dose, preferably at age 11 or 12 years |

|

| HIV-infected individuals ages 11-18 years | 2 doses, 2 months apart |

|

| Individuals ages 2-55 years with persistent complement component deficiency such as C5-C9, properdin, or factor D, or functional or anatomic asplenia | 2 doses, 2 months apart |

|

| Individuals ages 2-55 years with prolonged increased risk of exposure, such as microbiologists routinely working with Neisseria meningitidis and travelers to, or residents of, countries where meningococcal disease is hyperendemic or epidemic | 1 dose |

|

| Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011.10 | ||

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended immunization schedules for persons aged 0 through 18 years—United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep QuickGuide. 2011;60(5):1-4.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended adult immunization schedule-United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(4):1-4.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis (whooping cough): outbreaks. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/outbreaks.html. Accessed March 19, 2011.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(1):13-15.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ACIP presentation slides: February 2011 meeting. Available at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/acip/slides-feb11.htm#pertussis. Accessed March 19, 2011.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended antimicrobial agents for treatment and postexposure prophylaxis of pertussis: 2005 CDC guidelines. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54(RR-14):1-16.

7. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-8):1-62.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention of pneumococcal disease among infants and children—use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine—recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-11):1-18.

9. Campos-Outcalt D. Your guide to the new pneumococcal vaccine for children. J Fam Pract. 2010;59:394-398.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated recommendations for use of meningococcal conjugate vaccines—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:72-76.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FDA licensure of bivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV2, Cervarix) for use in females and updated HPV vaccination recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:626-629.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended immunization schedules for persons aged 0 through 18 years—United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep QuickGuide. 2011;60(5):1-4.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended adult immunization schedule-United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(4):1-4.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis (whooping cough): outbreaks. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/outbreaks.html. Accessed March 19, 2011.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(1):13-15.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ACIP presentation slides: February 2011 meeting. Available at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/acip/slides-feb11.htm#pertussis. Accessed March 19, 2011.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended antimicrobial agents for treatment and postexposure prophylaxis of pertussis: 2005 CDC guidelines. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54(RR-14):1-16.

7. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-8):1-62.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention of pneumococcal disease among infants and children—use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine—recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-11):1-18.

9. Campos-Outcalt D. Your guide to the new pneumococcal vaccine for children. J Fam Pract. 2010;59:394-398.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated recommendations for use of meningococcal conjugate vaccines—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:72-76.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FDA licensure of bivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV2, Cervarix) for use in females and updated HPV vaccination recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:626-629.

CDC update: Guidelines for treating STDs

In 2010, the CDC released an update of its Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STD) Treatment Guidelines,1 which were last updated in 2006. The guidelines are widely viewed as the most authoritative source of information on the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of STDs, and they are the standard for publicly and privately funded clinics focusing on sexual health.

What’s new

Some of the notable changes made since the last update in 2006 appear in TABLE 1.1,2

Uncomplicated gonorrhea. Cephalosporins are the only class of antibiotic recommended as first-line treatment for gonorrhea. (In a 2007 recommendation revision, the CDC opted to no longer recommend quinolone antibiotics for the treatment of gonorrhea, because of widespread bacterial resistance.3) Preference is now given to ceftriaxone because of its proven effectiveness against pharyngeal infection, which is often asymptomatic, difficult to detect, and difficult to eradicate. Additionally, the 2010 update has increased the recommended dose of ceftriazone from 125 to 250 mg intramuscularly. The larger dose is more effective against pharyngeal infection; it is also a safeguard against decreased bacterial susceptibility to cephalosporins, which, although still very low, has been reported in more cases recently.

The guidelines still recommend that azithromycin, 1 g orally in a single dose, be given with ceftriaxone because of the relatively high rate of co-infection with Chlamydia trachomatis and the potential for azithromycin to assist with eradicating any gonorrhea with decreased susceptibility to ceftriaxone.

Pelvic inflammatory disease. Quinolones have also been removed from the list of options for outpatient treatment of pelvic inflammatory disease. All recommended regimens now specify a parenteral cephalosporin as a single injection with doxycycline 100 mg PO twice a day for 14 days, with or without metronidazole 500 mg PO twice a day for 14 days.

Bacterial vaginosis. Tinidazole, 2 g orally once a day for 2 days or 1 g orally once a day for 5 days, is now an alternative agent for bacterial vaginosis. However, preferred treatments remain metronidazole 500 mg orally twice a day for 7 days, metronidazole gel intravaginally once a day for 5 days, or clindamycin cream intravaginally at bedtime for 7 days.

Newborn gonococcal eye infection. A relatively minor change is the elimination of tetracycline as prophylaxis for newborn gonococcal eye infections, leaving only erythromycin ointment to prevent the condition.

TABLE 1

2010 vs 2006: How have the CDC recommendations for STD treatment changed?1,2

Uncomplicated gonococcal infections of the cervix, urethra, rectum, and pharynx

|

| Pelvic inflammatory disease Parenteral regimens

|

Bacterial vaginosis

|

Prophylaxis for gonococcal eye infection in a newborn

|

Single-dose therapy preferred among equivalent options

Single-dose therapy (TABLE 2), while often more expensive than other options, increases compliance and helps ensure treatment completion. Single-dose therapy administered in your office is essentially directly observed treatment, an intervention that has become the standard of care for other diseases such as tuberculosis. If the single-dose agent is as effective as alternative medications, directly observed on-site administration is the preferred option for treating STDs.

TABLE 2

Single-dose therapies for specific STDs1

| Infection or condition | Single-dose therapy |

|---|---|

| Candida | Miconazole 1200 mg vaginal suppository or Tioconazole 6.5% ointment 5 g intravaginally or Butoconazole 2% cream 5 g intravaginally or Fluconazole 150 mg PO |

| Cervicitis | Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Chancroid | Azithromycin 1 g PO or Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM |

| Chlamydia urogenital infection | Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Gonorrhea: conjunctivitis | Ceftriaxone 1 g IM |

| Gonorrhea: uncomplicated infection of the cervix, urethra, rectum | Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM (preferred) or Cefixime 400 mg PO or Single-dose injectable cephalosporin plus Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Gonorrhea: uncomplicated infection of the pharynx | Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM plus Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Nongonococcal urethritis | Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Post-sexual assault prophylaxis | Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM or Cefixime 400 mg PO plus Metronidazole 2 g PO plus Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Recurrent, persistent nongonococcal urethritis | Metronidazole 2 g PO or Tinidazole 2 g PO plus Azithromycin 1 g PO (if not used for initial episode) |

| Syphilis: primary, secondary, and early latent | Benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units IM |

| Trichomoniasis | Metronidazole 2 g PO or Tinidazole 2 g PO |

Other guideline recommendations

The CDC’s STD treatment guidelines contain a wealth of useful information beyond treatment advice: recommended methods of confirming diagnoses, analyses of the usefulness of various diagnostic tests, recommendations on how to manage sex partners of those infected, guidance on STD prevention counseling, and considerations for special populations and circumstances.

Additionally, there is a section on screening for STDs reflecting recommendations of the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF); it also includes recommendations from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. In at least one instance, though, the USPSTF recommendation on screening for HIV infection contradicts other CDC sources.4,5 Also included is guidance on using vaccines to prevent hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and human papillomavirus (HPV), which follows the recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. When to use DNA testing to detect HPV is described briefly.

A shortcoming of the CDC guidelines

Although the CDC’s STD guidelines remain the most authoritative source of information on the diagnosis and treatment of STDs, they do not seem to use a consistent method for assessing and describing the strength of the evidence behind the recommendations, which family physicians have come to expect. (However, it is sometimes possible to discern the type and strength of evidence for a particular recommendation from the written discussion.)

The new guidelines state that a series of papers to be published in Clinical Infectious Diseases will describe more fully the evidence behind some of the recommendations and include evidence tables. However, in future guideline updates, it would be helpful if the CDC were to include a brief description of the quantity and strength of evidence alongside each recommended treatment option in the tables.

How best to keep up to date

Although the new guidelines summarize the current status of recommendations on the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of STDs and are a useful resource for family physicians, we cannot stay current simply by referring to them alone over the next 4 to 5 years until a new edition is published. As new evidence develops, changes in recommendations will be published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Case in point: new interim HIV recommendations. Interim recommendations were recently released on pre-exposure prophylaxis for men who have sex with men.6 (For more on these recommendations, check out this month’s audiocast at jfponline.com.) Final recommendations are expected later this year. Recommendations for post-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV infection are also expected soon.

1. Workowski KA, Berman S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Workowski KA, Berman SM. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-11):1-94.

3. Campos-Outcalt D. Practice alert: CDC no longer recommends quinolones for treatment of gonorrhea. J Fam Pract. 2007;56:554-558.

4. Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1-17.

5. Campos-Outcalt D. Time to revise your HIV testing routine. J Fam Pract. 2007;56:283-284.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Interim guidance: preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:65-68.

In 2010, the CDC released an update of its Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STD) Treatment Guidelines,1 which were last updated in 2006. The guidelines are widely viewed as the most authoritative source of information on the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of STDs, and they are the standard for publicly and privately funded clinics focusing on sexual health.

What’s new

Some of the notable changes made since the last update in 2006 appear in TABLE 1.1,2

Uncomplicated gonorrhea. Cephalosporins are the only class of antibiotic recommended as first-line treatment for gonorrhea. (In a 2007 recommendation revision, the CDC opted to no longer recommend quinolone antibiotics for the treatment of gonorrhea, because of widespread bacterial resistance.3) Preference is now given to ceftriaxone because of its proven effectiveness against pharyngeal infection, which is often asymptomatic, difficult to detect, and difficult to eradicate. Additionally, the 2010 update has increased the recommended dose of ceftriazone from 125 to 250 mg intramuscularly. The larger dose is more effective against pharyngeal infection; it is also a safeguard against decreased bacterial susceptibility to cephalosporins, which, although still very low, has been reported in more cases recently.

The guidelines still recommend that azithromycin, 1 g orally in a single dose, be given with ceftriaxone because of the relatively high rate of co-infection with Chlamydia trachomatis and the potential for azithromycin to assist with eradicating any gonorrhea with decreased susceptibility to ceftriaxone.

Pelvic inflammatory disease. Quinolones have also been removed from the list of options for outpatient treatment of pelvic inflammatory disease. All recommended regimens now specify a parenteral cephalosporin as a single injection with doxycycline 100 mg PO twice a day for 14 days, with or without metronidazole 500 mg PO twice a day for 14 days.

Bacterial vaginosis. Tinidazole, 2 g orally once a day for 2 days or 1 g orally once a day for 5 days, is now an alternative agent for bacterial vaginosis. However, preferred treatments remain metronidazole 500 mg orally twice a day for 7 days, metronidazole gel intravaginally once a day for 5 days, or clindamycin cream intravaginally at bedtime for 7 days.

Newborn gonococcal eye infection. A relatively minor change is the elimination of tetracycline as prophylaxis for newborn gonococcal eye infections, leaving only erythromycin ointment to prevent the condition.

TABLE 1

2010 vs 2006: How have the CDC recommendations for STD treatment changed?1,2

Uncomplicated gonococcal infections of the cervix, urethra, rectum, and pharynx

|

| Pelvic inflammatory disease Parenteral regimens

|

Bacterial vaginosis

|

Prophylaxis for gonococcal eye infection in a newborn

|

Single-dose therapy preferred among equivalent options

Single-dose therapy (TABLE 2), while often more expensive than other options, increases compliance and helps ensure treatment completion. Single-dose therapy administered in your office is essentially directly observed treatment, an intervention that has become the standard of care for other diseases such as tuberculosis. If the single-dose agent is as effective as alternative medications, directly observed on-site administration is the preferred option for treating STDs.

TABLE 2

Single-dose therapies for specific STDs1

| Infection or condition | Single-dose therapy |

|---|---|

| Candida | Miconazole 1200 mg vaginal suppository or Tioconazole 6.5% ointment 5 g intravaginally or Butoconazole 2% cream 5 g intravaginally or Fluconazole 150 mg PO |

| Cervicitis | Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Chancroid | Azithromycin 1 g PO or Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM |

| Chlamydia urogenital infection | Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Gonorrhea: conjunctivitis | Ceftriaxone 1 g IM |

| Gonorrhea: uncomplicated infection of the cervix, urethra, rectum | Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM (preferred) or Cefixime 400 mg PO or Single-dose injectable cephalosporin plus Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Gonorrhea: uncomplicated infection of the pharynx | Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM plus Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Nongonococcal urethritis | Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Post-sexual assault prophylaxis | Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM or Cefixime 400 mg PO plus Metronidazole 2 g PO plus Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Recurrent, persistent nongonococcal urethritis | Metronidazole 2 g PO or Tinidazole 2 g PO plus Azithromycin 1 g PO (if not used for initial episode) |

| Syphilis: primary, secondary, and early latent | Benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units IM |

| Trichomoniasis | Metronidazole 2 g PO or Tinidazole 2 g PO |

Other guideline recommendations

The CDC’s STD treatment guidelines contain a wealth of useful information beyond treatment advice: recommended methods of confirming diagnoses, analyses of the usefulness of various diagnostic tests, recommendations on how to manage sex partners of those infected, guidance on STD prevention counseling, and considerations for special populations and circumstances.

Additionally, there is a section on screening for STDs reflecting recommendations of the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF); it also includes recommendations from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. In at least one instance, though, the USPSTF recommendation on screening for HIV infection contradicts other CDC sources.4,5 Also included is guidance on using vaccines to prevent hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and human papillomavirus (HPV), which follows the recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. When to use DNA testing to detect HPV is described briefly.

A shortcoming of the CDC guidelines

Although the CDC’s STD guidelines remain the most authoritative source of information on the diagnosis and treatment of STDs, they do not seem to use a consistent method for assessing and describing the strength of the evidence behind the recommendations, which family physicians have come to expect. (However, it is sometimes possible to discern the type and strength of evidence for a particular recommendation from the written discussion.)

The new guidelines state that a series of papers to be published in Clinical Infectious Diseases will describe more fully the evidence behind some of the recommendations and include evidence tables. However, in future guideline updates, it would be helpful if the CDC were to include a brief description of the quantity and strength of evidence alongside each recommended treatment option in the tables.

How best to keep up to date

Although the new guidelines summarize the current status of recommendations on the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of STDs and are a useful resource for family physicians, we cannot stay current simply by referring to them alone over the next 4 to 5 years until a new edition is published. As new evidence develops, changes in recommendations will be published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Case in point: new interim HIV recommendations. Interim recommendations were recently released on pre-exposure prophylaxis for men who have sex with men.6 (For more on these recommendations, check out this month’s audiocast at jfponline.com.) Final recommendations are expected later this year. Recommendations for post-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV infection are also expected soon.

In 2010, the CDC released an update of its Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STD) Treatment Guidelines,1 which were last updated in 2006. The guidelines are widely viewed as the most authoritative source of information on the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of STDs, and they are the standard for publicly and privately funded clinics focusing on sexual health.

What’s new

Some of the notable changes made since the last update in 2006 appear in TABLE 1.1,2

Uncomplicated gonorrhea. Cephalosporins are the only class of antibiotic recommended as first-line treatment for gonorrhea. (In a 2007 recommendation revision, the CDC opted to no longer recommend quinolone antibiotics for the treatment of gonorrhea, because of widespread bacterial resistance.3) Preference is now given to ceftriaxone because of its proven effectiveness against pharyngeal infection, which is often asymptomatic, difficult to detect, and difficult to eradicate. Additionally, the 2010 update has increased the recommended dose of ceftriazone from 125 to 250 mg intramuscularly. The larger dose is more effective against pharyngeal infection; it is also a safeguard against decreased bacterial susceptibility to cephalosporins, which, although still very low, has been reported in more cases recently.

The guidelines still recommend that azithromycin, 1 g orally in a single dose, be given with ceftriaxone because of the relatively high rate of co-infection with Chlamydia trachomatis and the potential for azithromycin to assist with eradicating any gonorrhea with decreased susceptibility to ceftriaxone.

Pelvic inflammatory disease. Quinolones have also been removed from the list of options for outpatient treatment of pelvic inflammatory disease. All recommended regimens now specify a parenteral cephalosporin as a single injection with doxycycline 100 mg PO twice a day for 14 days, with or without metronidazole 500 mg PO twice a day for 14 days.

Bacterial vaginosis. Tinidazole, 2 g orally once a day for 2 days or 1 g orally once a day for 5 days, is now an alternative agent for bacterial vaginosis. However, preferred treatments remain metronidazole 500 mg orally twice a day for 7 days, metronidazole gel intravaginally once a day for 5 days, or clindamycin cream intravaginally at bedtime for 7 days.

Newborn gonococcal eye infection. A relatively minor change is the elimination of tetracycline as prophylaxis for newborn gonococcal eye infections, leaving only erythromycin ointment to prevent the condition.

TABLE 1

2010 vs 2006: How have the CDC recommendations for STD treatment changed?1,2

Uncomplicated gonococcal infections of the cervix, urethra, rectum, and pharynx

|

| Pelvic inflammatory disease Parenteral regimens

|

Bacterial vaginosis

|

Prophylaxis for gonococcal eye infection in a newborn

|

Single-dose therapy preferred among equivalent options

Single-dose therapy (TABLE 2), while often more expensive than other options, increases compliance and helps ensure treatment completion. Single-dose therapy administered in your office is essentially directly observed treatment, an intervention that has become the standard of care for other diseases such as tuberculosis. If the single-dose agent is as effective as alternative medications, directly observed on-site administration is the preferred option for treating STDs.

TABLE 2

Single-dose therapies for specific STDs1

| Infection or condition | Single-dose therapy |

|---|---|

| Candida | Miconazole 1200 mg vaginal suppository or Tioconazole 6.5% ointment 5 g intravaginally or Butoconazole 2% cream 5 g intravaginally or Fluconazole 150 mg PO |

| Cervicitis | Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Chancroid | Azithromycin 1 g PO or Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM |

| Chlamydia urogenital infection | Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Gonorrhea: conjunctivitis | Ceftriaxone 1 g IM |

| Gonorrhea: uncomplicated infection of the cervix, urethra, rectum | Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM (preferred) or Cefixime 400 mg PO or Single-dose injectable cephalosporin plus Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Gonorrhea: uncomplicated infection of the pharynx | Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM plus Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Nongonococcal urethritis | Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Post-sexual assault prophylaxis | Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM or Cefixime 400 mg PO plus Metronidazole 2 g PO plus Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Recurrent, persistent nongonococcal urethritis | Metronidazole 2 g PO or Tinidazole 2 g PO plus Azithromycin 1 g PO (if not used for initial episode) |

| Syphilis: primary, secondary, and early latent | Benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units IM |

| Trichomoniasis | Metronidazole 2 g PO or Tinidazole 2 g PO |

Other guideline recommendations

The CDC’s STD treatment guidelines contain a wealth of useful information beyond treatment advice: recommended methods of confirming diagnoses, analyses of the usefulness of various diagnostic tests, recommendations on how to manage sex partners of those infected, guidance on STD prevention counseling, and considerations for special populations and circumstances.

Additionally, there is a section on screening for STDs reflecting recommendations of the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF); it also includes recommendations from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. In at least one instance, though, the USPSTF recommendation on screening for HIV infection contradicts other CDC sources.4,5 Also included is guidance on using vaccines to prevent hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and human papillomavirus (HPV), which follows the recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. When to use DNA testing to detect HPV is described briefly.

A shortcoming of the CDC guidelines

Although the CDC’s STD guidelines remain the most authoritative source of information on the diagnosis and treatment of STDs, they do not seem to use a consistent method for assessing and describing the strength of the evidence behind the recommendations, which family physicians have come to expect. (However, it is sometimes possible to discern the type and strength of evidence for a particular recommendation from the written discussion.)

The new guidelines state that a series of papers to be published in Clinical Infectious Diseases will describe more fully the evidence behind some of the recommendations and include evidence tables. However, in future guideline updates, it would be helpful if the CDC were to include a brief description of the quantity and strength of evidence alongside each recommended treatment option in the tables.

How best to keep up to date

Although the new guidelines summarize the current status of recommendations on the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of STDs and are a useful resource for family physicians, we cannot stay current simply by referring to them alone over the next 4 to 5 years until a new edition is published. As new evidence develops, changes in recommendations will be published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Case in point: new interim HIV recommendations. Interim recommendations were recently released on pre-exposure prophylaxis for men who have sex with men.6 (For more on these recommendations, check out this month’s audiocast at jfponline.com.) Final recommendations are expected later this year. Recommendations for post-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV infection are also expected soon.

1. Workowski KA, Berman S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Workowski KA, Berman SM. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-11):1-94.

3. Campos-Outcalt D. Practice alert: CDC no longer recommends quinolones for treatment of gonorrhea. J Fam Pract. 2007;56:554-558.

4. Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1-17.

5. Campos-Outcalt D. Time to revise your HIV testing routine. J Fam Pract. 2007;56:283-284.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Interim guidance: preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:65-68.

1. Workowski KA, Berman S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Workowski KA, Berman SM. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-11):1-94.

3. Campos-Outcalt D. Practice alert: CDC no longer recommends quinolones for treatment of gonorrhea. J Fam Pract. 2007;56:554-558.

4. Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1-17.

5. Campos-Outcalt D. Time to revise your HIV testing routine. J Fam Pract. 2007;56:283-284.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Interim guidance: preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:65-68.

ACIP update: 2 new recommendations for meningococcal vaccine

At its October 2010 meeting, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) made 2 additions to its recommendations for quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MCV4), based on evolving knowledge of the vaccine and its duration of protection.

- A booster dose at age 16 has been added to the routine schedule for those vaccinated at ages 11 to 12 years. A booster dose has also been added for those vaccinated at ages 13 to 15 years, although the recommended timing of this booster had not been finalized at press time.

- A 2-dose primary series, 2 months apart, is now recommended for patients at higher risk of meningococcal disease. The high-risk category includes those with persistent complement component deficiency, asplenia, or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). High-risk patients who were previously vaccinated should receive a booster dose at the earliest opportunity and continue to receive boosters at the appropriate interval (3-5 years).

Meningitis is rare but serious

Meningococcal meningitis is a potentially devastating disease in adolescents and young adults. It has a case fatality rate of about 20%, and the sequelae for survivors can be severe: 3.1% require limb amputations and another 10.9% suffer neurological deficits.1 Thankfully, meningococcal disease is rare, occurring at rates below 1 in 200,000 in the 11- to 15-year-old age group and less than 1 in 100,000 in the 16- to 21-year-old age group.2

Routine immunization with MCV4 is recommended for adolescents

In 2007, ACIP recommended routine use of MCV4 for adolescents between the ages of 11 and 18 years. The recommendation gave preference to immunization at ages 11 to 12 years, along with the other adolescent vaccines given at that time.3 Updated recommendations in effect in 2010 state that those at highest risk for meningococcal infection (those with functional or anatomic asplenia, C3 complement deficiency, or HIV infection) should be vaccinated with MCV4 starting at age 2 and revaccinated every 3 years if last vaccinated at 2 to 6 years, and every 5 years if last vaccinated at or after age 7.4,5 TABLE 1 lists the recommendations for MCV4 in place prior to the October 2010 ACIP meeting.

Two MCV4 products are licensed for use in the United States: Menactra (Sanofi Pasteur) and Menveo (Novartis). Both contain antigens against 4 serotypes, A, C, Y, and W-135. Neither protects against type B, which causes a majority of the disease in infants.6 In recent years, serotype A disease has become extremely rare in the United States.6 MCV4 coverage for adolescents ages 13 to 17 years is increasing, going from 41.8% in 2008 to 53.6% in 2009.7

TABLE 1

Recommendations for MCV4 prior to October 20103-5

|

|

|

| MCV4, meningococcal conjugate vaccine. |

The new recommendations: One is more controversial than the other

The recommendation for a 2-dose primary series in high-risk groups was not controversial. The same conditions that place individuals at highest risk for meningococcal infection also result in a less robust response to a single dose of the vaccine, and a 2-dose series is needed to achieve protective antibody levels in a high proportion of those vaccine recipients.8 This recommendation will affect relatively few patients.

The recommendation for booster doses in the general adolescent population generated a lot more debate. Studies performed since the licensure of MCV4 have shown that levels of protective antibodies decline over time. Five years after vaccination, 50% of vaccine recipients have levels below that considered fully protective.2 One small case-control study of 107 cases suggested that the number of years from receipt of the vaccine was a risk factor for meningococcal disease.2

However, rates of meningococcal meningitis in adolescents have been declining over the past few years (TABLE 2), and there are no surveillance data to support the conclusion that teens vaccinated at ages 11 to 12 years are at increased risk as they age. In addition, the number of cases is very low (TABLE 3) and the cost benefit analysis of a booster dose of MCV4 is very unfavorable.1,2

TABLE 2

Rates* of serogroup C, Y, and W-135 meningococcal disease†

| Age group (y) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | 11-19 | ≥20 |

| 2004-2005 | 0.23 | 0.16 |

| 2006-2007 | 0.27 | 0.22 |

| 2008-2009 | 0.14 | 0.21 |

| *Annual rate per 100,000. †Serogroup A disease is too rare for inclusion here. Source: Cohn A. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Meeting; October 27, 2010.2 | ||

TABLE 3

Average annual number of cases of C, Y, and W-135 meningococcal disease

| Age group (y) | 2000-2004 | 2005-2009 | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11-14 | 46 | 12 | -74% |

| 15-18 | 106 | 77 | -27% |

| 19-22 | 62 | 52 | -16% |

| Total (11-22) | 214 | 141 | -34% |

| Source: Cohn A. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Meeting; October 27, 2010.2 | |||

ACIP weighed the options for a booster dose

Three options were presented at the October 2010 ACIP meeting:

- Option 1: No change to the current recommendation for vaccination of 11- to 12-year-olds. Wait and see what happens to disease incidence over several more years.

- Option 2: Move the age of vaccination to 15 years with no booster. This would allow protection to persist through the years of highest risk (16-21 years).

- Option 3: Keep the recommendation for vaccination at ages 11 to 12 years, and add a booster dose at age 16.

The first option was the least cost effective: $281,000/quality-adjusted life year (QALY). The second option was the most cost effective at $121,000/QALY. The last option came out in the middle: $157,000/QALY, but it would save the most lives—9 more per year compared with Option 2.1 There is, however, a caveat with regard to the cost-effectiveness estimates. The numbers were obtained using incidence data from the year 2000; incidence has declined since then, and cost-effectiveness estimates would be much less favorable using today’s rates.

These issues were discussed at length, and the decision to add a booster dose at age 16 was made on a close vote. This decision illustrates how difficult vaccine policy-making has become in recent years, when choices must be made about recommending safe, effective, and expensive vaccines to prevent illnesses that are both rare and serious.

The new MCV4 recommendations will be added to the child immunization schedule for 2011.

The take-home message for family physicians is to strive to increase the proportion of 11- to 12-year-olds who are fully vaccinated and in 2011 to begin to advise those who are between the ages of 16 and 20 years of the recommendation for a booster dose of MCV4.

1. Ortega-Sanchez I. Cost-effectiveness of meningococcal vaccination strategies for adolescents in the United States. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Meeting; October 27, 2010; Atlanta, Ga.

2. Cohn A. Optimizing the adolescent meningococcal vaccination program. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Meeting; October 27, 2010; Atlanta, Ga.

3. CDC. Revised recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices to vaccinate all persons aged 11-18 years with meningococcal conjugate vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:794-795.

4. CDC.Updated recommendation from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for revaccination of persons at prolonged increased risk for meningococcal disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:1042-1043.

5. CDC. Recommended immunization schedules for persons aged 0 through 18 years—United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;58:1-4.

6. Schaffner W, Harrison LH, Kaplan SL, et al. The changing epidemiology of meningococcal disease among U.S. children, adolescents and young adults. National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. November 2004. Available at: www.nfid.org/pdf/meningitis/FINALChanging_Epidemiology_of_Meningococcal_Disease.pdf. Accessed November 4, 2010.

7. CDC. National, state, and local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1018-1023.

8. Cohn A. Rationale and proposed recommendations for two dose primary vaccination for persons at increased risk for meningococcal disease. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Meeting; October 27, 2010; Atlanta, Ga.

At its October 2010 meeting, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) made 2 additions to its recommendations for quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MCV4), based on evolving knowledge of the vaccine and its duration of protection.

- A booster dose at age 16 has been added to the routine schedule for those vaccinated at ages 11 to 12 years. A booster dose has also been added for those vaccinated at ages 13 to 15 years, although the recommended timing of this booster had not been finalized at press time.

- A 2-dose primary series, 2 months apart, is now recommended for patients at higher risk of meningococcal disease. The high-risk category includes those with persistent complement component deficiency, asplenia, or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). High-risk patients who were previously vaccinated should receive a booster dose at the earliest opportunity and continue to receive boosters at the appropriate interval (3-5 years).

Meningitis is rare but serious

Meningococcal meningitis is a potentially devastating disease in adolescents and young adults. It has a case fatality rate of about 20%, and the sequelae for survivors can be severe: 3.1% require limb amputations and another 10.9% suffer neurological deficits.1 Thankfully, meningococcal disease is rare, occurring at rates below 1 in 200,000 in the 11- to 15-year-old age group and less than 1 in 100,000 in the 16- to 21-year-old age group.2

Routine immunization with MCV4 is recommended for adolescents

In 2007, ACIP recommended routine use of MCV4 for adolescents between the ages of 11 and 18 years. The recommendation gave preference to immunization at ages 11 to 12 years, along with the other adolescent vaccines given at that time.3 Updated recommendations in effect in 2010 state that those at highest risk for meningococcal infection (those with functional or anatomic asplenia, C3 complement deficiency, or HIV infection) should be vaccinated with MCV4 starting at age 2 and revaccinated every 3 years if last vaccinated at 2 to 6 years, and every 5 years if last vaccinated at or after age 7.4,5 TABLE 1 lists the recommendations for MCV4 in place prior to the October 2010 ACIP meeting.

Two MCV4 products are licensed for use in the United States: Menactra (Sanofi Pasteur) and Menveo (Novartis). Both contain antigens against 4 serotypes, A, C, Y, and W-135. Neither protects against type B, which causes a majority of the disease in infants.6 In recent years, serotype A disease has become extremely rare in the United States.6 MCV4 coverage for adolescents ages 13 to 17 years is increasing, going from 41.8% in 2008 to 53.6% in 2009.7

TABLE 1

Recommendations for MCV4 prior to October 20103-5

|

|

|

| MCV4, meningococcal conjugate vaccine. |

The new recommendations: One is more controversial than the other

The recommendation for a 2-dose primary series in high-risk groups was not controversial. The same conditions that place individuals at highest risk for meningococcal infection also result in a less robust response to a single dose of the vaccine, and a 2-dose series is needed to achieve protective antibody levels in a high proportion of those vaccine recipients.8 This recommendation will affect relatively few patients.

The recommendation for booster doses in the general adolescent population generated a lot more debate. Studies performed since the licensure of MCV4 have shown that levels of protective antibodies decline over time. Five years after vaccination, 50% of vaccine recipients have levels below that considered fully protective.2 One small case-control study of 107 cases suggested that the number of years from receipt of the vaccine was a risk factor for meningococcal disease.2

However, rates of meningococcal meningitis in adolescents have been declining over the past few years (TABLE 2), and there are no surveillance data to support the conclusion that teens vaccinated at ages 11 to 12 years are at increased risk as they age. In addition, the number of cases is very low (TABLE 3) and the cost benefit analysis of a booster dose of MCV4 is very unfavorable.1,2

TABLE 2

Rates* of serogroup C, Y, and W-135 meningococcal disease†

| Age group (y) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | 11-19 | ≥20 |

| 2004-2005 | 0.23 | 0.16 |

| 2006-2007 | 0.27 | 0.22 |

| 2008-2009 | 0.14 | 0.21 |

| *Annual rate per 100,000. †Serogroup A disease is too rare for inclusion here. Source: Cohn A. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Meeting; October 27, 2010.2 | ||

TABLE 3

Average annual number of cases of C, Y, and W-135 meningococcal disease

| Age group (y) | 2000-2004 | 2005-2009 | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11-14 | 46 | 12 | -74% |

| 15-18 | 106 | 77 | -27% |

| 19-22 | 62 | 52 | -16% |

| Total (11-22) | 214 | 141 | -34% |

| Source: Cohn A. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Meeting; October 27, 2010.2 | |||

ACIP weighed the options for a booster dose

Three options were presented at the October 2010 ACIP meeting:

- Option 1: No change to the current recommendation for vaccination of 11- to 12-year-olds. Wait and see what happens to disease incidence over several more years.

- Option 2: Move the age of vaccination to 15 years with no booster. This would allow protection to persist through the years of highest risk (16-21 years).

- Option 3: Keep the recommendation for vaccination at ages 11 to 12 years, and add a booster dose at age 16.

The first option was the least cost effective: $281,000/quality-adjusted life year (QALY). The second option was the most cost effective at $121,000/QALY. The last option came out in the middle: $157,000/QALY, but it would save the most lives—9 more per year compared with Option 2.1 There is, however, a caveat with regard to the cost-effectiveness estimates. The numbers were obtained using incidence data from the year 2000; incidence has declined since then, and cost-effectiveness estimates would be much less favorable using today’s rates.

These issues were discussed at length, and the decision to add a booster dose at age 16 was made on a close vote. This decision illustrates how difficult vaccine policy-making has become in recent years, when choices must be made about recommending safe, effective, and expensive vaccines to prevent illnesses that are both rare and serious.

The new MCV4 recommendations will be added to the child immunization schedule for 2011.

The take-home message for family physicians is to strive to increase the proportion of 11- to 12-year-olds who are fully vaccinated and in 2011 to begin to advise those who are between the ages of 16 and 20 years of the recommendation for a booster dose of MCV4.

At its October 2010 meeting, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) made 2 additions to its recommendations for quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MCV4), based on evolving knowledge of the vaccine and its duration of protection.

- A booster dose at age 16 has been added to the routine schedule for those vaccinated at ages 11 to 12 years. A booster dose has also been added for those vaccinated at ages 13 to 15 years, although the recommended timing of this booster had not been finalized at press time.

- A 2-dose primary series, 2 months apart, is now recommended for patients at higher risk of meningococcal disease. The high-risk category includes those with persistent complement component deficiency, asplenia, or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). High-risk patients who were previously vaccinated should receive a booster dose at the earliest opportunity and continue to receive boosters at the appropriate interval (3-5 years).

Meningitis is rare but serious

Meningococcal meningitis is a potentially devastating disease in adolescents and young adults. It has a case fatality rate of about 20%, and the sequelae for survivors can be severe: 3.1% require limb amputations and another 10.9% suffer neurological deficits.1 Thankfully, meningococcal disease is rare, occurring at rates below 1 in 200,000 in the 11- to 15-year-old age group and less than 1 in 100,000 in the 16- to 21-year-old age group.2

Routine immunization with MCV4 is recommended for adolescents

In 2007, ACIP recommended routine use of MCV4 for adolescents between the ages of 11 and 18 years. The recommendation gave preference to immunization at ages 11 to 12 years, along with the other adolescent vaccines given at that time.3 Updated recommendations in effect in 2010 state that those at highest risk for meningococcal infection (those with functional or anatomic asplenia, C3 complement deficiency, or HIV infection) should be vaccinated with MCV4 starting at age 2 and revaccinated every 3 years if last vaccinated at 2 to 6 years, and every 5 years if last vaccinated at or after age 7.4,5 TABLE 1 lists the recommendations for MCV4 in place prior to the October 2010 ACIP meeting.

Two MCV4 products are licensed for use in the United States: Menactra (Sanofi Pasteur) and Menveo (Novartis). Both contain antigens against 4 serotypes, A, C, Y, and W-135. Neither protects against type B, which causes a majority of the disease in infants.6 In recent years, serotype A disease has become extremely rare in the United States.6 MCV4 coverage for adolescents ages 13 to 17 years is increasing, going from 41.8% in 2008 to 53.6% in 2009.7

TABLE 1

Recommendations for MCV4 prior to October 20103-5

|

|

|

| MCV4, meningococcal conjugate vaccine. |

The new recommendations: One is more controversial than the other

The recommendation for a 2-dose primary series in high-risk groups was not controversial. The same conditions that place individuals at highest risk for meningococcal infection also result in a less robust response to a single dose of the vaccine, and a 2-dose series is needed to achieve protective antibody levels in a high proportion of those vaccine recipients.8 This recommendation will affect relatively few patients.

The recommendation for booster doses in the general adolescent population generated a lot more debate. Studies performed since the licensure of MCV4 have shown that levels of protective antibodies decline over time. Five years after vaccination, 50% of vaccine recipients have levels below that considered fully protective.2 One small case-control study of 107 cases suggested that the number of years from receipt of the vaccine was a risk factor for meningococcal disease.2

However, rates of meningococcal meningitis in adolescents have been declining over the past few years (TABLE 2), and there are no surveillance data to support the conclusion that teens vaccinated at ages 11 to 12 years are at increased risk as they age. In addition, the number of cases is very low (TABLE 3) and the cost benefit analysis of a booster dose of MCV4 is very unfavorable.1,2

TABLE 2

Rates* of serogroup C, Y, and W-135 meningococcal disease†

| Age group (y) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | 11-19 | ≥20 |

| 2004-2005 | 0.23 | 0.16 |

| 2006-2007 | 0.27 | 0.22 |

| 2008-2009 | 0.14 | 0.21 |

| *Annual rate per 100,000. †Serogroup A disease is too rare for inclusion here. Source: Cohn A. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Meeting; October 27, 2010.2 | ||

TABLE 3

Average annual number of cases of C, Y, and W-135 meningococcal disease

| Age group (y) | 2000-2004 | 2005-2009 | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11-14 | 46 | 12 | -74% |

| 15-18 | 106 | 77 | -27% |

| 19-22 | 62 | 52 | -16% |

| Total (11-22) | 214 | 141 | -34% |

| Source: Cohn A. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Meeting; October 27, 2010.2 | |||

ACIP weighed the options for a booster dose

Three options were presented at the October 2010 ACIP meeting:

- Option 1: No change to the current recommendation for vaccination of 11- to 12-year-olds. Wait and see what happens to disease incidence over several more years.

- Option 2: Move the age of vaccination to 15 years with no booster. This would allow protection to persist through the years of highest risk (16-21 years).

- Option 3: Keep the recommendation for vaccination at ages 11 to 12 years, and add a booster dose at age 16.

The first option was the least cost effective: $281,000/quality-adjusted life year (QALY). The second option was the most cost effective at $121,000/QALY. The last option came out in the middle: $157,000/QALY, but it would save the most lives—9 more per year compared with Option 2.1 There is, however, a caveat with regard to the cost-effectiveness estimates. The numbers were obtained using incidence data from the year 2000; incidence has declined since then, and cost-effectiveness estimates would be much less favorable using today’s rates.

These issues were discussed at length, and the decision to add a booster dose at age 16 was made on a close vote. This decision illustrates how difficult vaccine policy-making has become in recent years, when choices must be made about recommending safe, effective, and expensive vaccines to prevent illnesses that are both rare and serious.

The new MCV4 recommendations will be added to the child immunization schedule for 2011.

The take-home message for family physicians is to strive to increase the proportion of 11- to 12-year-olds who are fully vaccinated and in 2011 to begin to advise those who are between the ages of 16 and 20 years of the recommendation for a booster dose of MCV4.

1. Ortega-Sanchez I. Cost-effectiveness of meningococcal vaccination strategies for adolescents in the United States. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Meeting; October 27, 2010; Atlanta, Ga.

2. Cohn A. Optimizing the adolescent meningococcal vaccination program. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Meeting; October 27, 2010; Atlanta, Ga.

3. CDC. Revised recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices to vaccinate all persons aged 11-18 years with meningococcal conjugate vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:794-795.

4. CDC.Updated recommendation from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for revaccination of persons at prolonged increased risk for meningococcal disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:1042-1043.

5. CDC. Recommended immunization schedules for persons aged 0 through 18 years—United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;58:1-4.

6. Schaffner W, Harrison LH, Kaplan SL, et al. The changing epidemiology of meningococcal disease among U.S. children, adolescents and young adults. National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. November 2004. Available at: www.nfid.org/pdf/meningitis/FINALChanging_Epidemiology_of_Meningococcal_Disease.pdf. Accessed November 4, 2010.

7. CDC. National, state, and local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1018-1023.

8. Cohn A. Rationale and proposed recommendations for two dose primary vaccination for persons at increased risk for meningococcal disease. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Meeting; October 27, 2010; Atlanta, Ga.

1. Ortega-Sanchez I. Cost-effectiveness of meningococcal vaccination strategies for adolescents in the United States. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Meeting; October 27, 2010; Atlanta, Ga.

2. Cohn A. Optimizing the adolescent meningococcal vaccination program. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Meeting; October 27, 2010; Atlanta, Ga.

3. CDC. Revised recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices to vaccinate all persons aged 11-18 years with meningococcal conjugate vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:794-795.

4. CDC.Updated recommendation from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for revaccination of persons at prolonged increased risk for meningococcal disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:1042-1043.

5. CDC. Recommended immunization schedules for persons aged 0 through 18 years—United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;58:1-4.

6. Schaffner W, Harrison LH, Kaplan SL, et al. The changing epidemiology of meningococcal disease among U.S. children, adolescents and young adults. National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. November 2004. Available at: www.nfid.org/pdf/meningitis/FINALChanging_Epidemiology_of_Meningococcal_Disease.pdf. Accessed November 4, 2010.

7. CDC. National, state, and local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1018-1023.

8. Cohn A. Rationale and proposed recommendations for two dose primary vaccination for persons at increased risk for meningococcal disease. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Meeting; October 27, 2010; Atlanta, Ga.

Flu season’s almost here: Are you ready?

Influenza pandemics like the one we had last year are uncommon, and mounting an effective response was a difficult challenge. The pandemic hit early and hard. Physicians and the public health system responded well, administering a seasonal flu vaccine as well as a new H1N1 vaccine that was approved, produced, and distributed in record time. Before the end of the season, approximately 30% of the population had received an H1N1 vaccine and 40% a seasonal vaccine.1

What happened last year