User login

Laxative Use with Patient-Controlled Analgesia in the Hospital and Associated Outcomes

From the Division of General Internal Medicine (Dr. Lenz), Division of Biomedical Statistics and Informatics (Mr. Schroeder), and the Division of Hospital Internal Medicine (Ms. Lawson and Dr. Yu), Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe prophylactic laxative effectiveness and prescribing patterns in patients initiated on intravenous (IV) opioid analgesia.

- Design: Retrospective cohort study.

- Setting and participants: All patients who were on IV narcotics with a patient-controlled pump while admitted to a general medicine service at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester in 2011 and 2012 were identified. Patients were excluded if constipation or diarrhea were diagnosed prior to IV opioid analgesia initiation.

- Measurements: Prophylactic laxatives were defined as laxatives prescribed within 24 hours of IV opioid analgesia initiation to be given even in the absence of constipation. Constipation was recorded when diagnosed during the hospitalization. Severe constipation was defined as constipation resulting in an abdominal CT or X-ray; abdominal distension, pain, or bloating; or if an enema was performed during the hospitalization.

- Results: Of 283 patients, 101 (36%) received prophylactic laxatives and 182 (64%) did not. Constipation occurred in 61 (34%) not on prophylactic laxatives and in 49 (49%) on prophylactic laxatives (P = 0.015). Severe constipation occurred in 23 (13%) not on prophylactic laxatives and in 33 (33%) on prophylactic laxatives (P < 0.001).

- Conclusion: A large percentage of patients are not receiving prophylactic laxatives when receiving IV opioid analgesia in the hospital. Current laxative strategies are not effectively preventing constipation in patients when prescribed.

Key words: constipation; opioids; hospital medicine; patient-controlled analgesia; laxatives.

Opioid-induced constipation (OIC) is defined as a change, when initiating opioid therapy, from baseline bowel habits and defecation patterns that is characterized by any of the following: reduced bowel frequency; development or worsening of straining; a sense of incomplete evacuation; or a patient’s perception of distress related to bowel habits [1]. It is an important side effect to consider when initiating narcotic analgesia. It has been estimated that approximately 3% to 4% of the population is on chronic narcotic pain relievers in the outpatient setting [2,3], and 37% to 81% of these patients will experience constipation [3–9]. Because of the high incidence of constipation, the prophylactic prescription of laxatives with initiation of opioid pain relievers is frequently recommended [10–15]. Furthermore, it has been shown that among patients admitted to the hospital with cancer, there is a lower incidence of constipation amongst those who have received prophylactic laxatives [16]. However, there is no evidence in the literature that prophylactic laxatives improve outcomes in patients on opioid analgesia in the general medicine inpatient setting. Furthermore, studies have illustrated that recommendations for prophylactic laxative use are not reliably followed [3,9].

While the incidence of OIC is well described in the outpatient setting [17,18], there are few studies looking at the incidence of OIC in the hospital setting. It has been shown, however, that occurrence during even a brief hospitalization is possible [4,6]. Acute constipation while hospitalized can theoretically lead to longer hospitalizations, increased pain, and decreased quality of life [6,7,19]. Recent research has focused heavily on the use of novel agents such as peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonists in the treatment of OIC [20–23]. However, the expense of these agents makes them less than ideal in the prophylactic setting. This study will assess the effectiveness and prescribing patterns of prophylactic laxatives in the inpatient general medicine setting over a 2-year period at our institution in patients initiated on patient-controlled analgesia with hydromorphone, morphine, or fentanyl.

Methods

This study was approved by the institutional review board at the Mayo Clinic Rochester. All patients who were initiated on intravenous analgesia with an electronic patient-controlled opioid pump (PCA) while admitted to a general medicine service in 2011 and 2012 were identified. Patients who received PCA therapy were identified through a pharmacy database. Only patients older than 18 years of age were included in the study. PCA therapy was selected for our analysis because PCA therapy is not regularly administered on an outpatient basis. All of these patients, therefore, had a change in their narcotic regimen on admission to the hospital. Patients were excluded from the study if they were on a PCA for less than 24 hours; had a PCA initiated on a service other than a general medicine service; were on a scheduled laxative regimen prior to admission; or carried a diagnosis of bowel obstruction, chronic diarrhea, constipation, or intestinal discontinuity (eg, those with previous diversions or ostomies).

A retrospective review of each patient’s chart was conducted with the assistance of a team of nurse abstractors. Basic demographic data were recorded for each patient. Date of hospital admission and discharge; scheduled laxatives ordered and administered (any dose of sennosides, polyethylene glycol, docusate, bisacodyl, lactulose, or magnesium citrate); abdominal X-rays and abdominal CT scans performed for constipation; and any administration of enemas were recorded. Fiber supplements were not considered laxatives. If a patient was documented to have constipation during their hospitalization this was recorded. Patients were classified as having severe constipation if an abdominal CT or x-ray was performed for the indication of constipation; if abdominal distension, pain, or bloating were documented due to constipation; or if an enema was performed during the hospitalization.

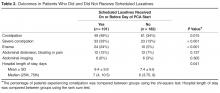

For analysis purposes, patients who started receiving scheduled laxatives (as opposed to laxatives “as needed”)on or before the day of PCA initiation were classified as receiving prophylactic laxatives. Baseline patient characteristics and outcomes were compared using the chi-square test for nominal variables and the rank sum test for continuous variables. In all cases, 2-tailed tests were performed with P values ≤ 0.05 considered statistically significant. A nominal logistic regression model was utilized to assess for independent association of risk factors with the outcome of constipation.

Results

Discussion

Patients initiated on opioid therapy were not prescribed prophylactic laxatives in 64% of our cohort in the inpatient setting. When prescribed, current laxative strategies did not effectively prevent constipation with 49% experiencing OIC. Our data serves as a strong reminder of the magnitude of the problem of OIC in the inpatient setting.

The strength of our paper lies in its role as a magnitude assessment. This retrospective review reveals for that among a diverse group of patients hospitalized within a large academic institution, OIC remains prevalent. Furthermore, the high incidence of severe constipation indicates the potential for increased health care costs and patient discomfort secondary to OIC emphasizing the importance of prevention of OIC. Recent guidelines have made a push toward prophylactic laxative utilization earlier. Specifically, the European Palliative Research Collaborative offers a “strong recommendation to routinely prescribe laxatives for the management or prophylaxis of opioid-induced constipation” [10]. Additionally, the American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians suggests that “a physician should consider the initiation of a bowel regimen even before the development of constipation and definitely after the development of constipation” [11]. Our manuscript serves as a reminder that OIC remains a very prevalent problem and that prophylactic laxatives are still being underutilized.

This is a retrospective study and thus has inherent limitations. Specifically, we are limited to those cases of constipation that were documented in the medical record. The presentation of constipation is varied between patients. This variation in presentation of OIC is inherent to the disease process as is demonstrated in the broad definition for OIC [1]. The cases of constipation that we are reporting clearly were bothersome enough to warrant documentation in the medical record, and while there may have been cases that escaped documentation, we can be confident that the cases of OIC we are reporting are true cases of OIC. The numbers we report can therefore be taken to represent a minimum number of cases of constipation occurring in our study population.

It has been suggested that OIC prevalence varies with type of opioid and duration of opioid therapy [24]. We did not compare dose, type, or duration of opioid therapy in this study. This could certainly account for the seemingly higher rate of constipation within the group treated with prophylactic laxatives as compared with those not treated with prophylactic laxatives. Physicians likely have a higher propensity to prescribe prophylactic laxatives to patients receiving high doses of opioids who are in turn at higher risk for OIC. We cannot say whether differences in efficacy exist between prophylactic laxative regimens or which opioids (dose and duration) cause the most constipation based upon our data. Future studies incorporating dose, duration, and opioid type along with the variables we collected in this study could potentially construct successful logistic regression models with predictive power to identify those at highest risk of OIC.

Our rate of OIC is consistent with previously published figures [3–9]. However, we demonstrate for the first time that prophylactic laxatives are prescribed infrequently and unsuccessfully in the inpatient setting. This is consistent with prescribing rates in the outpatient setting [9,25]. Furthermore, we observed a higher rate of constipation in those treated with prophylactic laxatives compared to those that did not receive prophylactic laxatives. Pottegard et al similarly demonstrated an increased rate of constipation in those utilizing laxative therapy [25]. This is likely secondary to providers recommending prophylactic laxatives to those patients most likely to develop constipation. Despite being able to recognize high-risk patients, providers are unable to prevent OIC as little is known regarding optimal laxative strategies. Previous studies comparing treatment regimens for the relief of constipation in the palliative care population have been largely inconclusive [26]. There have been no studies to date comparing different prophylactic laxatives in the inpatient setting.

Future directions for research in this area would ideally take the form of randomized controlled trials investigating efficacy of different prophylactic laxatives in the inpatient setting. These trials would ideally include well-defined patient groups receiving specific narcotics for specific reasons. These studies would be best if powered to assess the effect of narcotic dosage and duration of therapy as well. Alternatively, larger retrospective chart reviews could be performed including narcotic dosage, type, and duration of therapy with a planned logistic regression model attempting to account for likely independent variables.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates for the first time that prophylactic laxatives are not being prescribed frequently to patients on opioid analgesia in the inpatient general medicine setting. Additionally, while providers seem to be identifying patients at higher risk of constipation, they are still unable to prevent constipation in a high percentage of patients. Further research into this area would be beneficial to prevent this uncomfortable, costly, and preventable complication of opioid analgesia.

Corresponding author: Roger Yu, MD, Mayo Clinic, 200 First St. SW, Rochester, MN 55905, [email protected].

Funding/support: This research was supported by the Mayo Clinic Return to Work program nurses for data abstraction.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Mearin F, Lacy BE, Chang L, et al. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2016.

2. Boudreau D, Von Korff M, Rutter CM, et al. Trends in long-term opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2009;18:1166–75.

3. Choung RS, Locke GR 3rd, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Opioid bowel dysfunction and narcotic bowel syndrome: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:1199–204.

4. Droney J, Ross J, Gretton S, et al. Constipation in cancer patients on morphine. Support Care Cancer 2008;16:453–9.

5. Sykes NP. The relationship between opioid use and laxative use in terminally ill cancer patients. Palliat Med 1998;12:375–82.

6. Bell TJ, Panchal SJ, Miaskowski C, et al. The prevalence, severity, and impact of opioid-induced bowel dysfunction: results of a US and European Patient Survey (PROBE 1). Pain Med 2009;10:35–42.

7. Cook SF, Lanza L, Zhou X, et al. Gastrointestinal side effects in chronic opioid users: results from a population-based survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008;27:1224–32.

8. Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Prevalence of opioid adverse events in chronic non-malignant pain: systematic review of randomised trials of oral opioids. Arthritis Res Ther 2005:7:R1046–51.

9. Bouvy ML, Buurma H, Egberts TC. Laxative prescribing in relation to opioid use and the influence of pharmacy-based intervention. J Clin Pharm Ther 2002;27:107–10.

10. Caraceni A, Hanks G, Kaasa S, et al. Use of opioid analgesics in the treatment of cancer pain: evidence-based recommendations from the EAPC. Lancet Oncol 2012:13:e58–68.

11. Manchikanti L, Abdi S, Atluri S, et al. American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) guidelines for responsible opioid prescribing in chronic non-cancer pain: Part 2--guidance. Pain Physician 2012;15(3 Suppl):S67–116.

12. Cameron JC. Constipation related to narcotic therapy. A protocol for nurses and patients. Cancer Nurs 1992;15:372–7.

13. Levy MH. Pharmacologic treatment of cancer pain. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1124–32.

14. Swegle JM, Logemann D. Management of common opioid-induced adverse effects. Am Fam Physician 2006;74:1347–54.

15. Donnelly S, Davis MP, Walsh D, Naughton M. Morphine in cancer pain management: a practical guide. Support Care Cancer 2002;10:13–35.

16. Ishihara M, Ikesue H Matsunaga H, et al. A multi-institutional study analyzing effect of prophylactic medication for prevention of opioid-induced gastrointestinal dysfunction. Clin J Pain 2012;28:373–81.

17. Kalso E, Edwards JE, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Opioids in chronic non-cancer pain: systematic review of efficacy and safety. Pain 2004;112:372–80.

18. Tuteja AK, Biskupiak J, Stoddard GJ, Lipman AG. Opioid-induced bowel disorders and narcotic bowel syndrome in patients with chronic non-cancer pain. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2010; 22:424–30, e96.

19. Brock C, Olesen SS, Olesen AE, et al. Opioid-induced bowel dysfunction: pathophysiology and management. Drugs 2012;72:1847–65.

20. Camilleri M. Opioid-induced constipation: challenges and therapeutic opportunities. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:835–42.

21. Candy B, Jones L, Goodman ML, et al. Laxatives or methylnaltrexone for the management of constipation in palliative care patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011(1):CD003448.

22. Ford AC, Brenner DM, Schoenfeld PS. Efficacy of pharmacological therapies for the treatment of opioid-induced constipation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:1566–74.

23. Jansen JP, Lorch D, Langan J, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial (Study SB-767905/012) of alvimopan for opioid-induced bowel dysfunction in patients with non-cancer pain. J Pain 2011;12:185–93.

24. Camilleri M, Drossman DA, Becker G, et al. Emerging treatments in neurogastroenterology: a multidisciplinary working group consensus statement on opioid-induced constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2014;26:1386–95.

25. Pottegard A, Knudsen TB, van Heesch K, et al. Information on risk of constipation for Danish users of opioids, and their laxative use. Int J Clin Pharm 2014;36:291–4.

26. Candy B, Jones L, Larkin PJ, et al. Laxatives for the management of constipation in people receiving palliative care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015(5):CD003448.

From the Division of General Internal Medicine (Dr. Lenz), Division of Biomedical Statistics and Informatics (Mr. Schroeder), and the Division of Hospital Internal Medicine (Ms. Lawson and Dr. Yu), Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe prophylactic laxative effectiveness and prescribing patterns in patients initiated on intravenous (IV) opioid analgesia.

- Design: Retrospective cohort study.

- Setting and participants: All patients who were on IV narcotics with a patient-controlled pump while admitted to a general medicine service at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester in 2011 and 2012 were identified. Patients were excluded if constipation or diarrhea were diagnosed prior to IV opioid analgesia initiation.

- Measurements: Prophylactic laxatives were defined as laxatives prescribed within 24 hours of IV opioid analgesia initiation to be given even in the absence of constipation. Constipation was recorded when diagnosed during the hospitalization. Severe constipation was defined as constipation resulting in an abdominal CT or X-ray; abdominal distension, pain, or bloating; or if an enema was performed during the hospitalization.

- Results: Of 283 patients, 101 (36%) received prophylactic laxatives and 182 (64%) did not. Constipation occurred in 61 (34%) not on prophylactic laxatives and in 49 (49%) on prophylactic laxatives (P = 0.015). Severe constipation occurred in 23 (13%) not on prophylactic laxatives and in 33 (33%) on prophylactic laxatives (P < 0.001).

- Conclusion: A large percentage of patients are not receiving prophylactic laxatives when receiving IV opioid analgesia in the hospital. Current laxative strategies are not effectively preventing constipation in patients when prescribed.

Key words: constipation; opioids; hospital medicine; patient-controlled analgesia; laxatives.

Opioid-induced constipation (OIC) is defined as a change, when initiating opioid therapy, from baseline bowel habits and defecation patterns that is characterized by any of the following: reduced bowel frequency; development or worsening of straining; a sense of incomplete evacuation; or a patient’s perception of distress related to bowel habits [1]. It is an important side effect to consider when initiating narcotic analgesia. It has been estimated that approximately 3% to 4% of the population is on chronic narcotic pain relievers in the outpatient setting [2,3], and 37% to 81% of these patients will experience constipation [3–9]. Because of the high incidence of constipation, the prophylactic prescription of laxatives with initiation of opioid pain relievers is frequently recommended [10–15]. Furthermore, it has been shown that among patients admitted to the hospital with cancer, there is a lower incidence of constipation amongst those who have received prophylactic laxatives [16]. However, there is no evidence in the literature that prophylactic laxatives improve outcomes in patients on opioid analgesia in the general medicine inpatient setting. Furthermore, studies have illustrated that recommendations for prophylactic laxative use are not reliably followed [3,9].

While the incidence of OIC is well described in the outpatient setting [17,18], there are few studies looking at the incidence of OIC in the hospital setting. It has been shown, however, that occurrence during even a brief hospitalization is possible [4,6]. Acute constipation while hospitalized can theoretically lead to longer hospitalizations, increased pain, and decreased quality of life [6,7,19]. Recent research has focused heavily on the use of novel agents such as peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonists in the treatment of OIC [20–23]. However, the expense of these agents makes them less than ideal in the prophylactic setting. This study will assess the effectiveness and prescribing patterns of prophylactic laxatives in the inpatient general medicine setting over a 2-year period at our institution in patients initiated on patient-controlled analgesia with hydromorphone, morphine, or fentanyl.

Methods

This study was approved by the institutional review board at the Mayo Clinic Rochester. All patients who were initiated on intravenous analgesia with an electronic patient-controlled opioid pump (PCA) while admitted to a general medicine service in 2011 and 2012 were identified. Patients who received PCA therapy were identified through a pharmacy database. Only patients older than 18 years of age were included in the study. PCA therapy was selected for our analysis because PCA therapy is not regularly administered on an outpatient basis. All of these patients, therefore, had a change in their narcotic regimen on admission to the hospital. Patients were excluded from the study if they were on a PCA for less than 24 hours; had a PCA initiated on a service other than a general medicine service; were on a scheduled laxative regimen prior to admission; or carried a diagnosis of bowel obstruction, chronic diarrhea, constipation, or intestinal discontinuity (eg, those with previous diversions or ostomies).

A retrospective review of each patient’s chart was conducted with the assistance of a team of nurse abstractors. Basic demographic data were recorded for each patient. Date of hospital admission and discharge; scheduled laxatives ordered and administered (any dose of sennosides, polyethylene glycol, docusate, bisacodyl, lactulose, or magnesium citrate); abdominal X-rays and abdominal CT scans performed for constipation; and any administration of enemas were recorded. Fiber supplements were not considered laxatives. If a patient was documented to have constipation during their hospitalization this was recorded. Patients were classified as having severe constipation if an abdominal CT or x-ray was performed for the indication of constipation; if abdominal distension, pain, or bloating were documented due to constipation; or if an enema was performed during the hospitalization.

For analysis purposes, patients who started receiving scheduled laxatives (as opposed to laxatives “as needed”)on or before the day of PCA initiation were classified as receiving prophylactic laxatives. Baseline patient characteristics and outcomes were compared using the chi-square test for nominal variables and the rank sum test for continuous variables. In all cases, 2-tailed tests were performed with P values ≤ 0.05 considered statistically significant. A nominal logistic regression model was utilized to assess for independent association of risk factors with the outcome of constipation.

Results

Discussion

Patients initiated on opioid therapy were not prescribed prophylactic laxatives in 64% of our cohort in the inpatient setting. When prescribed, current laxative strategies did not effectively prevent constipation with 49% experiencing OIC. Our data serves as a strong reminder of the magnitude of the problem of OIC in the inpatient setting.

The strength of our paper lies in its role as a magnitude assessment. This retrospective review reveals for that among a diverse group of patients hospitalized within a large academic institution, OIC remains prevalent. Furthermore, the high incidence of severe constipation indicates the potential for increased health care costs and patient discomfort secondary to OIC emphasizing the importance of prevention of OIC. Recent guidelines have made a push toward prophylactic laxative utilization earlier. Specifically, the European Palliative Research Collaborative offers a “strong recommendation to routinely prescribe laxatives for the management or prophylaxis of opioid-induced constipation” [10]. Additionally, the American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians suggests that “a physician should consider the initiation of a bowel regimen even before the development of constipation and definitely after the development of constipation” [11]. Our manuscript serves as a reminder that OIC remains a very prevalent problem and that prophylactic laxatives are still being underutilized.

This is a retrospective study and thus has inherent limitations. Specifically, we are limited to those cases of constipation that were documented in the medical record. The presentation of constipation is varied between patients. This variation in presentation of OIC is inherent to the disease process as is demonstrated in the broad definition for OIC [1]. The cases of constipation that we are reporting clearly were bothersome enough to warrant documentation in the medical record, and while there may have been cases that escaped documentation, we can be confident that the cases of OIC we are reporting are true cases of OIC. The numbers we report can therefore be taken to represent a minimum number of cases of constipation occurring in our study population.

It has been suggested that OIC prevalence varies with type of opioid and duration of opioid therapy [24]. We did not compare dose, type, or duration of opioid therapy in this study. This could certainly account for the seemingly higher rate of constipation within the group treated with prophylactic laxatives as compared with those not treated with prophylactic laxatives. Physicians likely have a higher propensity to prescribe prophylactic laxatives to patients receiving high doses of opioids who are in turn at higher risk for OIC. We cannot say whether differences in efficacy exist between prophylactic laxative regimens or which opioids (dose and duration) cause the most constipation based upon our data. Future studies incorporating dose, duration, and opioid type along with the variables we collected in this study could potentially construct successful logistic regression models with predictive power to identify those at highest risk of OIC.

Our rate of OIC is consistent with previously published figures [3–9]. However, we demonstrate for the first time that prophylactic laxatives are prescribed infrequently and unsuccessfully in the inpatient setting. This is consistent with prescribing rates in the outpatient setting [9,25]. Furthermore, we observed a higher rate of constipation in those treated with prophylactic laxatives compared to those that did not receive prophylactic laxatives. Pottegard et al similarly demonstrated an increased rate of constipation in those utilizing laxative therapy [25]. This is likely secondary to providers recommending prophylactic laxatives to those patients most likely to develop constipation. Despite being able to recognize high-risk patients, providers are unable to prevent OIC as little is known regarding optimal laxative strategies. Previous studies comparing treatment regimens for the relief of constipation in the palliative care population have been largely inconclusive [26]. There have been no studies to date comparing different prophylactic laxatives in the inpatient setting.

Future directions for research in this area would ideally take the form of randomized controlled trials investigating efficacy of different prophylactic laxatives in the inpatient setting. These trials would ideally include well-defined patient groups receiving specific narcotics for specific reasons. These studies would be best if powered to assess the effect of narcotic dosage and duration of therapy as well. Alternatively, larger retrospective chart reviews could be performed including narcotic dosage, type, and duration of therapy with a planned logistic regression model attempting to account for likely independent variables.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates for the first time that prophylactic laxatives are not being prescribed frequently to patients on opioid analgesia in the inpatient general medicine setting. Additionally, while providers seem to be identifying patients at higher risk of constipation, they are still unable to prevent constipation in a high percentage of patients. Further research into this area would be beneficial to prevent this uncomfortable, costly, and preventable complication of opioid analgesia.

Corresponding author: Roger Yu, MD, Mayo Clinic, 200 First St. SW, Rochester, MN 55905, [email protected].

Funding/support: This research was supported by the Mayo Clinic Return to Work program nurses for data abstraction.

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Division of General Internal Medicine (Dr. Lenz), Division of Biomedical Statistics and Informatics (Mr. Schroeder), and the Division of Hospital Internal Medicine (Ms. Lawson and Dr. Yu), Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe prophylactic laxative effectiveness and prescribing patterns in patients initiated on intravenous (IV) opioid analgesia.

- Design: Retrospective cohort study.

- Setting and participants: All patients who were on IV narcotics with a patient-controlled pump while admitted to a general medicine service at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester in 2011 and 2012 were identified. Patients were excluded if constipation or diarrhea were diagnosed prior to IV opioid analgesia initiation.

- Measurements: Prophylactic laxatives were defined as laxatives prescribed within 24 hours of IV opioid analgesia initiation to be given even in the absence of constipation. Constipation was recorded when diagnosed during the hospitalization. Severe constipation was defined as constipation resulting in an abdominal CT or X-ray; abdominal distension, pain, or bloating; or if an enema was performed during the hospitalization.

- Results: Of 283 patients, 101 (36%) received prophylactic laxatives and 182 (64%) did not. Constipation occurred in 61 (34%) not on prophylactic laxatives and in 49 (49%) on prophylactic laxatives (P = 0.015). Severe constipation occurred in 23 (13%) not on prophylactic laxatives and in 33 (33%) on prophylactic laxatives (P < 0.001).

- Conclusion: A large percentage of patients are not receiving prophylactic laxatives when receiving IV opioid analgesia in the hospital. Current laxative strategies are not effectively preventing constipation in patients when prescribed.

Key words: constipation; opioids; hospital medicine; patient-controlled analgesia; laxatives.

Opioid-induced constipation (OIC) is defined as a change, when initiating opioid therapy, from baseline bowel habits and defecation patterns that is characterized by any of the following: reduced bowel frequency; development or worsening of straining; a sense of incomplete evacuation; or a patient’s perception of distress related to bowel habits [1]. It is an important side effect to consider when initiating narcotic analgesia. It has been estimated that approximately 3% to 4% of the population is on chronic narcotic pain relievers in the outpatient setting [2,3], and 37% to 81% of these patients will experience constipation [3–9]. Because of the high incidence of constipation, the prophylactic prescription of laxatives with initiation of opioid pain relievers is frequently recommended [10–15]. Furthermore, it has been shown that among patients admitted to the hospital with cancer, there is a lower incidence of constipation amongst those who have received prophylactic laxatives [16]. However, there is no evidence in the literature that prophylactic laxatives improve outcomes in patients on opioid analgesia in the general medicine inpatient setting. Furthermore, studies have illustrated that recommendations for prophylactic laxative use are not reliably followed [3,9].

While the incidence of OIC is well described in the outpatient setting [17,18], there are few studies looking at the incidence of OIC in the hospital setting. It has been shown, however, that occurrence during even a brief hospitalization is possible [4,6]. Acute constipation while hospitalized can theoretically lead to longer hospitalizations, increased pain, and decreased quality of life [6,7,19]. Recent research has focused heavily on the use of novel agents such as peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonists in the treatment of OIC [20–23]. However, the expense of these agents makes them less than ideal in the prophylactic setting. This study will assess the effectiveness and prescribing patterns of prophylactic laxatives in the inpatient general medicine setting over a 2-year period at our institution in patients initiated on patient-controlled analgesia with hydromorphone, morphine, or fentanyl.

Methods

This study was approved by the institutional review board at the Mayo Clinic Rochester. All patients who were initiated on intravenous analgesia with an electronic patient-controlled opioid pump (PCA) while admitted to a general medicine service in 2011 and 2012 were identified. Patients who received PCA therapy were identified through a pharmacy database. Only patients older than 18 years of age were included in the study. PCA therapy was selected for our analysis because PCA therapy is not regularly administered on an outpatient basis. All of these patients, therefore, had a change in their narcotic regimen on admission to the hospital. Patients were excluded from the study if they were on a PCA for less than 24 hours; had a PCA initiated on a service other than a general medicine service; were on a scheduled laxative regimen prior to admission; or carried a diagnosis of bowel obstruction, chronic diarrhea, constipation, or intestinal discontinuity (eg, those with previous diversions or ostomies).

A retrospective review of each patient’s chart was conducted with the assistance of a team of nurse abstractors. Basic demographic data were recorded for each patient. Date of hospital admission and discharge; scheduled laxatives ordered and administered (any dose of sennosides, polyethylene glycol, docusate, bisacodyl, lactulose, or magnesium citrate); abdominal X-rays and abdominal CT scans performed for constipation; and any administration of enemas were recorded. Fiber supplements were not considered laxatives. If a patient was documented to have constipation during their hospitalization this was recorded. Patients were classified as having severe constipation if an abdominal CT or x-ray was performed for the indication of constipation; if abdominal distension, pain, or bloating were documented due to constipation; or if an enema was performed during the hospitalization.

For analysis purposes, patients who started receiving scheduled laxatives (as opposed to laxatives “as needed”)on or before the day of PCA initiation were classified as receiving prophylactic laxatives. Baseline patient characteristics and outcomes were compared using the chi-square test for nominal variables and the rank sum test for continuous variables. In all cases, 2-tailed tests were performed with P values ≤ 0.05 considered statistically significant. A nominal logistic regression model was utilized to assess for independent association of risk factors with the outcome of constipation.

Results

Discussion

Patients initiated on opioid therapy were not prescribed prophylactic laxatives in 64% of our cohort in the inpatient setting. When prescribed, current laxative strategies did not effectively prevent constipation with 49% experiencing OIC. Our data serves as a strong reminder of the magnitude of the problem of OIC in the inpatient setting.

The strength of our paper lies in its role as a magnitude assessment. This retrospective review reveals for that among a diverse group of patients hospitalized within a large academic institution, OIC remains prevalent. Furthermore, the high incidence of severe constipation indicates the potential for increased health care costs and patient discomfort secondary to OIC emphasizing the importance of prevention of OIC. Recent guidelines have made a push toward prophylactic laxative utilization earlier. Specifically, the European Palliative Research Collaborative offers a “strong recommendation to routinely prescribe laxatives for the management or prophylaxis of opioid-induced constipation” [10]. Additionally, the American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians suggests that “a physician should consider the initiation of a bowel regimen even before the development of constipation and definitely after the development of constipation” [11]. Our manuscript serves as a reminder that OIC remains a very prevalent problem and that prophylactic laxatives are still being underutilized.

This is a retrospective study and thus has inherent limitations. Specifically, we are limited to those cases of constipation that were documented in the medical record. The presentation of constipation is varied between patients. This variation in presentation of OIC is inherent to the disease process as is demonstrated in the broad definition for OIC [1]. The cases of constipation that we are reporting clearly were bothersome enough to warrant documentation in the medical record, and while there may have been cases that escaped documentation, we can be confident that the cases of OIC we are reporting are true cases of OIC. The numbers we report can therefore be taken to represent a minimum number of cases of constipation occurring in our study population.

It has been suggested that OIC prevalence varies with type of opioid and duration of opioid therapy [24]. We did not compare dose, type, or duration of opioid therapy in this study. This could certainly account for the seemingly higher rate of constipation within the group treated with prophylactic laxatives as compared with those not treated with prophylactic laxatives. Physicians likely have a higher propensity to prescribe prophylactic laxatives to patients receiving high doses of opioids who are in turn at higher risk for OIC. We cannot say whether differences in efficacy exist between prophylactic laxative regimens or which opioids (dose and duration) cause the most constipation based upon our data. Future studies incorporating dose, duration, and opioid type along with the variables we collected in this study could potentially construct successful logistic regression models with predictive power to identify those at highest risk of OIC.

Our rate of OIC is consistent with previously published figures [3–9]. However, we demonstrate for the first time that prophylactic laxatives are prescribed infrequently and unsuccessfully in the inpatient setting. This is consistent with prescribing rates in the outpatient setting [9,25]. Furthermore, we observed a higher rate of constipation in those treated with prophylactic laxatives compared to those that did not receive prophylactic laxatives. Pottegard et al similarly demonstrated an increased rate of constipation in those utilizing laxative therapy [25]. This is likely secondary to providers recommending prophylactic laxatives to those patients most likely to develop constipation. Despite being able to recognize high-risk patients, providers are unable to prevent OIC as little is known regarding optimal laxative strategies. Previous studies comparing treatment regimens for the relief of constipation in the palliative care population have been largely inconclusive [26]. There have been no studies to date comparing different prophylactic laxatives in the inpatient setting.

Future directions for research in this area would ideally take the form of randomized controlled trials investigating efficacy of different prophylactic laxatives in the inpatient setting. These trials would ideally include well-defined patient groups receiving specific narcotics for specific reasons. These studies would be best if powered to assess the effect of narcotic dosage and duration of therapy as well. Alternatively, larger retrospective chart reviews could be performed including narcotic dosage, type, and duration of therapy with a planned logistic regression model attempting to account for likely independent variables.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates for the first time that prophylactic laxatives are not being prescribed frequently to patients on opioid analgesia in the inpatient general medicine setting. Additionally, while providers seem to be identifying patients at higher risk of constipation, they are still unable to prevent constipation in a high percentage of patients. Further research into this area would be beneficial to prevent this uncomfortable, costly, and preventable complication of opioid analgesia.

Corresponding author: Roger Yu, MD, Mayo Clinic, 200 First St. SW, Rochester, MN 55905, [email protected].

Funding/support: This research was supported by the Mayo Clinic Return to Work program nurses for data abstraction.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Mearin F, Lacy BE, Chang L, et al. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2016.

2. Boudreau D, Von Korff M, Rutter CM, et al. Trends in long-term opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2009;18:1166–75.

3. Choung RS, Locke GR 3rd, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Opioid bowel dysfunction and narcotic bowel syndrome: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:1199–204.

4. Droney J, Ross J, Gretton S, et al. Constipation in cancer patients on morphine. Support Care Cancer 2008;16:453–9.

5. Sykes NP. The relationship between opioid use and laxative use in terminally ill cancer patients. Palliat Med 1998;12:375–82.

6. Bell TJ, Panchal SJ, Miaskowski C, et al. The prevalence, severity, and impact of opioid-induced bowel dysfunction: results of a US and European Patient Survey (PROBE 1). Pain Med 2009;10:35–42.

7. Cook SF, Lanza L, Zhou X, et al. Gastrointestinal side effects in chronic opioid users: results from a population-based survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008;27:1224–32.

8. Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Prevalence of opioid adverse events in chronic non-malignant pain: systematic review of randomised trials of oral opioids. Arthritis Res Ther 2005:7:R1046–51.

9. Bouvy ML, Buurma H, Egberts TC. Laxative prescribing in relation to opioid use and the influence of pharmacy-based intervention. J Clin Pharm Ther 2002;27:107–10.

10. Caraceni A, Hanks G, Kaasa S, et al. Use of opioid analgesics in the treatment of cancer pain: evidence-based recommendations from the EAPC. Lancet Oncol 2012:13:e58–68.

11. Manchikanti L, Abdi S, Atluri S, et al. American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) guidelines for responsible opioid prescribing in chronic non-cancer pain: Part 2--guidance. Pain Physician 2012;15(3 Suppl):S67–116.

12. Cameron JC. Constipation related to narcotic therapy. A protocol for nurses and patients. Cancer Nurs 1992;15:372–7.

13. Levy MH. Pharmacologic treatment of cancer pain. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1124–32.

14. Swegle JM, Logemann D. Management of common opioid-induced adverse effects. Am Fam Physician 2006;74:1347–54.

15. Donnelly S, Davis MP, Walsh D, Naughton M. Morphine in cancer pain management: a practical guide. Support Care Cancer 2002;10:13–35.

16. Ishihara M, Ikesue H Matsunaga H, et al. A multi-institutional study analyzing effect of prophylactic medication for prevention of opioid-induced gastrointestinal dysfunction. Clin J Pain 2012;28:373–81.

17. Kalso E, Edwards JE, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Opioids in chronic non-cancer pain: systematic review of efficacy and safety. Pain 2004;112:372–80.

18. Tuteja AK, Biskupiak J, Stoddard GJ, Lipman AG. Opioid-induced bowel disorders and narcotic bowel syndrome in patients with chronic non-cancer pain. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2010; 22:424–30, e96.

19. Brock C, Olesen SS, Olesen AE, et al. Opioid-induced bowel dysfunction: pathophysiology and management. Drugs 2012;72:1847–65.

20. Camilleri M. Opioid-induced constipation: challenges and therapeutic opportunities. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:835–42.

21. Candy B, Jones L, Goodman ML, et al. Laxatives or methylnaltrexone for the management of constipation in palliative care patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011(1):CD003448.

22. Ford AC, Brenner DM, Schoenfeld PS. Efficacy of pharmacological therapies for the treatment of opioid-induced constipation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:1566–74.

23. Jansen JP, Lorch D, Langan J, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial (Study SB-767905/012) of alvimopan for opioid-induced bowel dysfunction in patients with non-cancer pain. J Pain 2011;12:185–93.

24. Camilleri M, Drossman DA, Becker G, et al. Emerging treatments in neurogastroenterology: a multidisciplinary working group consensus statement on opioid-induced constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2014;26:1386–95.

25. Pottegard A, Knudsen TB, van Heesch K, et al. Information on risk of constipation for Danish users of opioids, and their laxative use. Int J Clin Pharm 2014;36:291–4.

26. Candy B, Jones L, Larkin PJ, et al. Laxatives for the management of constipation in people receiving palliative care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015(5):CD003448.

1. Mearin F, Lacy BE, Chang L, et al. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2016.

2. Boudreau D, Von Korff M, Rutter CM, et al. Trends in long-term opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2009;18:1166–75.

3. Choung RS, Locke GR 3rd, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Opioid bowel dysfunction and narcotic bowel syndrome: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:1199–204.

4. Droney J, Ross J, Gretton S, et al. Constipation in cancer patients on morphine. Support Care Cancer 2008;16:453–9.

5. Sykes NP. The relationship between opioid use and laxative use in terminally ill cancer patients. Palliat Med 1998;12:375–82.

6. Bell TJ, Panchal SJ, Miaskowski C, et al. The prevalence, severity, and impact of opioid-induced bowel dysfunction: results of a US and European Patient Survey (PROBE 1). Pain Med 2009;10:35–42.

7. Cook SF, Lanza L, Zhou X, et al. Gastrointestinal side effects in chronic opioid users: results from a population-based survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008;27:1224–32.

8. Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Prevalence of opioid adverse events in chronic non-malignant pain: systematic review of randomised trials of oral opioids. Arthritis Res Ther 2005:7:R1046–51.

9. Bouvy ML, Buurma H, Egberts TC. Laxative prescribing in relation to opioid use and the influence of pharmacy-based intervention. J Clin Pharm Ther 2002;27:107–10.

10. Caraceni A, Hanks G, Kaasa S, et al. Use of opioid analgesics in the treatment of cancer pain: evidence-based recommendations from the EAPC. Lancet Oncol 2012:13:e58–68.

11. Manchikanti L, Abdi S, Atluri S, et al. American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) guidelines for responsible opioid prescribing in chronic non-cancer pain: Part 2--guidance. Pain Physician 2012;15(3 Suppl):S67–116.

12. Cameron JC. Constipation related to narcotic therapy. A protocol for nurses and patients. Cancer Nurs 1992;15:372–7.

13. Levy MH. Pharmacologic treatment of cancer pain. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1124–32.

14. Swegle JM, Logemann D. Management of common opioid-induced adverse effects. Am Fam Physician 2006;74:1347–54.

15. Donnelly S, Davis MP, Walsh D, Naughton M. Morphine in cancer pain management: a practical guide. Support Care Cancer 2002;10:13–35.

16. Ishihara M, Ikesue H Matsunaga H, et al. A multi-institutional study analyzing effect of prophylactic medication for prevention of opioid-induced gastrointestinal dysfunction. Clin J Pain 2012;28:373–81.

17. Kalso E, Edwards JE, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Opioids in chronic non-cancer pain: systematic review of efficacy and safety. Pain 2004;112:372–80.

18. Tuteja AK, Biskupiak J, Stoddard GJ, Lipman AG. Opioid-induced bowel disorders and narcotic bowel syndrome in patients with chronic non-cancer pain. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2010; 22:424–30, e96.

19. Brock C, Olesen SS, Olesen AE, et al. Opioid-induced bowel dysfunction: pathophysiology and management. Drugs 2012;72:1847–65.

20. Camilleri M. Opioid-induced constipation: challenges and therapeutic opportunities. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:835–42.

21. Candy B, Jones L, Goodman ML, et al. Laxatives or methylnaltrexone for the management of constipation in palliative care patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011(1):CD003448.

22. Ford AC, Brenner DM, Schoenfeld PS. Efficacy of pharmacological therapies for the treatment of opioid-induced constipation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:1566–74.

23. Jansen JP, Lorch D, Langan J, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial (Study SB-767905/012) of alvimopan for opioid-induced bowel dysfunction in patients with non-cancer pain. J Pain 2011;12:185–93.

24. Camilleri M, Drossman DA, Becker G, et al. Emerging treatments in neurogastroenterology: a multidisciplinary working group consensus statement on opioid-induced constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2014;26:1386–95.

25. Pottegard A, Knudsen TB, van Heesch K, et al. Information on risk of constipation for Danish users of opioids, and their laxative use. Int J Clin Pharm 2014;36:291–4.

26. Candy B, Jones L, Larkin PJ, et al. Laxatives for the management of constipation in people receiving palliative care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015(5):CD003448.