User login

The Enhanced Care Program: Impact of a Care Transition Program on 30-Day Hospital Readmissions for Patients Discharged From an Acute Care Facility to Skilled Nursing Facilities

Public reporting of readmission rates on the Nursing Home Compare website is mandated to begin on October 1, 2017, with skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) set to receive a Medicare bonus or penalty beginning a year later.1 The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) began public reporting of hospitals’ 30-day readmission rates for selected conditions in 2009, and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 mandated financial penalties for excess readmissions through the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program.2 In response, most hospitals have focused on patients who return home following discharge. Innovative interventions have proven successful, such as the Transitional Care model developed by Naylor and Coleman’s Care Transitions Intervention.3-5 Approximately 20% of Medicare beneficiaries are discharged from hospitals to SNFs, and these patients have higher readmission rates than those discharged home. CMS reported that in 2010, 23.3% of those with an SNF stay were readmitted within 30 days, compared with 18.8% for those with other discharge dispositions.6

Some work has been undertaken in this arena. In 2012, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) and the Medicare-Medicaid Coordination Office jointly launched the Initiative to Reduce Avoidable Hospitalizations among Nursing Facility Residents.7 This partnership established 7 Enhanced Care and Coordination Provider organizations and was designed to improve care by reducing hospitalizations among long-stay, dual-eligible nursing facility residents at 143 nursing homes in 7 states.8 At the time of the most recent project report, there were mixed results regarding program effects on hospitalizations and spending, with 2 states showing strongly positive patterns, 3 states with reductions that were consistent though not statistically strong, and mixed results in the remaining states. Quality measures did not show any pattern suggesting a program effect.9 Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers (INTERACT) II was a 6-month, collaborative, quality-improvement project implemented in 2009 at 30 nursing homes in 3 states.10 The project evaluation found a statistically significant, 17% decrease in self-reported hospital admissions among the 25 SNFs that completed the intervention, compared with the same 6 months in the prior year. The Cleveland Clinic recently reported favorable results implementing its Connected Care model, which relied on staff physicians and advanced practice professionals to visit patients 4 to 5 times per week and be on call 24/7 at 7 intervention SNFs.11 Through this intervention, it successfully reduced its 30-day hospital readmission rate from SNFs from 28.1% to 21.7% (P < 0.001), and the authors posed the question as to whether its model and results were reproducible in other healthcare systems.

Herein, we report on the results of a collaborative initiative named the Enhanced Care Program (ECP), which offers the services of clinical providers and administrative staff to assist with the care of patients at 8 partner SNFs. The 3 components of ECP (described below) were specifically designed to address commonly recognized gaps and opportunities in routine SNF care. In contrast to the Cleveland Clinic’s Connected Care model (which involved hospital-employed physicians serving as the SNF attendings and excluded patients followed by their own physicians), ECP was designed to integrate into a pluralistic, community model whereby independent physicians continued to follow their own patients at the SNFs. The Connected Care analysis compared participating versus nonparticipating SNFs; both the Connected Care model and the INTERACT II evaluation relied on pre–post comparisons; the CMMI evaluation used a difference-in-differences model to compare the outcomes of the program SNFs with those of a matched comparison group of nonparticipating SNFs. The evaluation of ECP differs from these other initiatives, using a concurrent comparison group of patients discharged to the same SNFs but who were not enrolled in ECP.

METHODS

Setting

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center (CSMC) is an 850-bed, acute care facility located in an urban area of Los Angeles. Eight SNFs, ranging in size from 49 to 150 beds and located between 0.6 and 2.2 miles from CSMC, were invited to partner with the ECP. The physician community encompasses more than 2000 physicians on the medical staff, including private practitioners, nonteaching hospitalists, full-time faculty hospitalists, and faculty specialists.

Study Design and Patients

This was an observational, retrospective cohort analysis of 30-day same-hospital readmissions among 3951 patients discharged from CSMC to 8 SNFs between January 1, 2014, and June 30, 2015. A total of 2394 patients were enrolled in the ECP, and 1557 patients were not enrolled.

ECP Enrollment Protocol

Every patient discharged from CSMC to 1 of the 8 partner SNFs was eligible to participate in the program. To respect the autonomy of the SNF attending physicians and to facilitate a collaborative relationship, the decision to enroll a patient in the ECP rested with the SNF attending physician. The ECP team maintained a database that tracked whether each SNF attending physician (1) opted to automatically enroll all his or her patients in the ECP, (2) opted to enroll patients on a case-by-case basis (in which case an ECP nurse practitioner [N

Program Description

Patients enrolled in the ECP experienced the standard care provided by the SNF staff and attending physicians plus a clinical care program delivered by 9 full-time NPs, 1 full-time pharmacist, 1 pharmacy technician, 1 full-time nurse educator, a program administrator, and a medical director.

The program included the following 3 major components:

1. Direct patient care and 24/7 NP availability: Program enrollment began with an on-site, bedside evaluation by an ECP NP at the SNF within 24 hours of arrival and continued with weekly NP rounding (or more frequently, if clinically indicated) on the patient. Each encounter included a review of the medical record; a dialogue with the patient’s SNF attending physician to formulate treatment plans and place orders; discussions with nurses, family members, and other caregivers; and documentation in the medical record. The ECP team was on-site at the SNFs 7 days a week and on call 24/7 to address questions and concerns. Patients remained enrolled in the ECP from SNF admission to discharge even if their stay extended beyond 30 days.

2. Medication reconciliation: The ECP pharmacy team completed a review of a patient’s SNF medication administration record (MAR) within 72 hours of SNF admission. This process involved the pharmacy technician gathering medication lists from the SNFs and CSMC and providing this information to the pharmacist for a medication reconciliation and clinical evaluation. Discrepancies and pharmacist recommendations were communicated to the ECP NPs, and all identified issues were resolved.

3. Educational in-services: Building upon the INTERACT II model, the ECP team identified high-yield, clinically relevant topics, which the ECP nurse educator turned into monthly educational sessions for the SNF nursing staff at each of the participating SNFs.10

Primary Outcome Measure

An inpatient readmission to CSMC within 30 days of the hospital discharge date was counted as a readmission, whether the patient returned directly from an SNF or was readmitted from home after an SNF discharge.

Data

ECP patients were identified using a log maintained by the ECP program manager. Non-ECP patients discharged to the same SNFs during the study period were identified from CSMC’s electronic registry of SNF discharges. Covariates known to be associated with increased risk of 30-day readmission were obtained from CSMC’s electronic data warehouse, including demographic information, length of stay (LOS) of index hospitalization, and payer.12 Eleven clinical service lines represented patients’ clinical conditions based on Medicare-Severity Diagnosis-Related groupings. The discharge severity of illness score was calculated using 3M All Patients Refined Diagnosis Related Group software, version 33.13

Analysis

Characteristics of the ECP and non-ECP patients were compared using the χ2 test. A multivariable logistic regression model with fixed effects for SNF was created to determine the program’s impact on 30-day hospital readmission, adjusting for patient characteristics. The Pearson χ2 goodness-of-fit test and the link test for model specification were used to evaluate model specification. The sensitivity of the results to differences in patient characteristics was assessed in 2 ways. First, the ECP and non-ECP populations were stratified based on race and/or ethnicity and payer, and the multivariable regression model was run within the strata associated with the highest readmission rates. Second, a propensity analysis using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) was performed to control for group differences. Results of all comparisons were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05. Stata version 13 was used to perform the main analyses.14 The propensity analysis was conducted using R version 3.2.3. The CSMC Institutional Review Board (IRB) determined that this study qualified as a quality-improvement activity and did not require IRB approval or exemption.

RESULTS

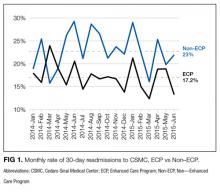

The average unadjusted 30-day readmission rate for ECP patients over the 18-month study period was 17.2%, compared to 23.0% for patients not enrolled in ECP (P < 0.001) (Figure 1). After adjusting for patient characteristics, ECP patients had 29% lower odds (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.60-0.85) of being readmitted to the medical center within 30 days than non-ECP patients at the same SNFs. The characteristics of the ECP and comparison patient cohorts are shown in Table 1. There were significant differences in sociodemographic characteristics: The ECP group had a higher proportion of non-Hispanic white patients, while the comparison group had a higher proportion of patients who were African American or Hispanic. ECP patients were more likely to prefer speaking English, while Russian, Farsi, and Spanish were preferred more frequently in the comparison group. There were also differences in payer mix, with the ECP group including proportionately more Medicare fee-for-service (52.9% vs 35.0%, P < 0.001), while the comparison group had a correspondingly larger proportion of dual-eligible (Medicare and Medicaid) patients (55.0% vs 35.1%, P < 0.001).

The largest clinical differences observed between the ECP and non-ECP groups were the proportions of patients in the clinical service lines of orthopedic surgery (28.7% vs 21.1%, P < 0.001), medical cardiology (7.4% vs 9.7%, P < 0.001), and surgery other than general surgery (5.8% vs 9.2%, P < 0.001). Despite these differences in case mix, no differences were seen between the 2 groups in discharge severity of illness or LOS of the index hospitalization. The distribution of index hospital LOS by quartile was the same, with the exception that the ECP group had a higher proportion of patients with longer LOS.

Sensitivity Analyses

The results were robust when tested within strata of the study population, including analyses limited to dual-eligible patients, African American patients, patients admitted to all except the highest volume facility, and patients admitted to any service line other than orthopedic surgery. Similar results were obtained when the study population was restricted to patients living within the medical center’s primary service area and to patients living in zip codes in which the proportion of adults living in households with income below 100% of the poverty level was 15% or greater (see Supplementary Material for results).

The effect of the program on readmission was also consistent when the full logistic regression model was run with IPTW using the propensity score. The evaluation of standardized cluster differences between the ECP and non-ECP groups before and after IPTW showed that the differences were reduced to <10% for being African American; speaking Russian or Farsi; having dual-eligible insurance coverage; having orthopedic surgery; being discharged from the clinical service lines of gastroenterology, pulmonary, other surgery, and other services; and having an index hospital LOS of 4 to 5 days or 10 or more days (results are provided in the Supplementary Material).

DISCUSSION

Hospitals continue to experience significant pressure to manage LOS, and SNFs and hospitals are being held accountable for readmission rates. The setting of this study is representative of many large, urban hospitals in the United States whose communities include a heterogeneous mix of hospitalists, primary care physicians who follow their patients in SNFs, and independent SNFs.15 The current regulations have not kept up with the increasing acuity and complexity of SNF patients. Specifically, Medicare guidelines allow the SNF attending physician up to 72 hours to complete a history and physical (or 7 days if he or she was the hospital attending physician for the index hospitalization) and only require monthly follow-up visits. It is the opinion of the ECP designers that these relatively lax requirements present unnecessary risk for vulnerable patients. While the INTERACT II model was focused largely on educational initiatives (with an advanced practice nurse available in a consultative role, as needed), the central tenet of ECP was similar to the Connected Care model in that the focus was on adding an extra layer of direct clinical support. Protocols that provided timely initial assessments by an NP (within 24 hours), weekly NP rounding (at a minimum), and 24/7 on-call availability all contributed to helping patients stay on track. Although the ECP had patients visited less frequently than the Connected Care model, and the Cleveland Clinic started with a higher baseline 30-day readmission rate from SNFs, similar overall reductions in 30-day readmissions were observed. The key point from both initiatives is that an increase in clinical touchpoints and ease of access to clinicians generates myriad opportunities to identify and address small issues before they become clinical emergencies requiring hospital transfers and readmissions.

Correcting medication discrepancies between hospital discharge summaries and SNF admission orders through a systematic medication reconciliation using a clinical pharmacist has previously been shown to improve outcomes.16-18 The ECP pharmacy technician and ECP clinical pharmacist discovered and corrected errors on a daily basis that ranged from incidental to potentially life-threatening. If the SNF staff does not provide the patient’s MAR within 48 hours of arrival, the pharmacy technician contacts the facility to obtain the information. As a result, all patients enrolled in the ECP during the study period received this intervention (unless they were rehospitalized or left the SNF before the process was completed), and 54% of ECP patients required some form of intervention after medication reconciliation was completed (data not shown).

This type of program requires hospital leadership and SNF administrators to be fully committed to developing strong working relationships, and in fact, there is evidence that SNF baseline readmission rates have a greater influence on patients’ risk of rehospitalization than the discharging hospital itself.19-21 Monthly educational in-services are delivered at the partner SNFs to enhance SNF nursing staff knowledge and clinical acumen. High-impact topics identified by the ECP team include the following: fall prevention, hand hygiene, venous thromboembolism, cardiovascular health, how to report change in condition, and advanced care planning, among others. While no formal pre–post assessments of the SNF nurses’ knowledge were conducted, a log of in-services was kept, subjective feedback was collected for performance improvement purposes, and continuing educational units were provided to the SNF nurses who attended.

This study has limitations. As a single-hospital study, generalizability may be limited. While adherence to the program components was closely monitored daily, service gaps may have occurred that were not captured. The program design makes it difficult to quantify the relative impact of the 3 program components on the outcome. Furthermore, the study was observational, so the differences in readmission rates may have been due to unmeasured variables. The decision to enroll patients in the ECP was made by each patient’s SNF attending physician, and those who chose to (or not to) participate in the program may manifest other, unmeasured practice patterns that made readmissions more or less likely. Participating physicians also had the option to enroll their patients on a case-by-case basis, introducing further potential bias in patient selection; however, <5% of physicians exercised this option. Patients may have also been readmitted to hospitals other than CSMC, producing an observed readmission rate for 1 or both groups that underrepresents the true outcome. On this point, while we did not systematically track these other-hospital readmissions for both groups, there is no reason to believe that this occurred preferentially for ECP or non-ECP patients.

Multiple sensitivity analyses were performed to address the observed differences between ECP and non-ECP patients. These included stratified examinations of variables differing between populations, examination of clustering effects between SNFs, and an analysis adjusted for the propensity to be included in the ECP. The calculated effect of the intervention on readmission remained robust, although we acknowledge that differences in the populations may persist and have influenced the outcomes even after controlling for multiple variables.22-25

In conclusion, the results of this intervention are compelling and add to the growing body of literature suggesting that a comprehensive, multipronged effort to enhance clinical oversight and coordination of care for SNF patients can improve outcomes. Given CMS’s plans to report SNF readmission rates in 2017 followed by the application of financial incentives in 2018, a favorable climate currently exists for greater coordination between hospitals and SNFs.26 We are currently undertaking an economic evaluation of the program.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following people for their contributions: Mae Saunders, Rita Shane, Dr. Jon Kea, Miranda Li, the ECP NPs, the ECP pharmacy team, CSMC’s performance improvement team, and Alan Matus.

Disclosure

No conflicts of interest or disclosures.

1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS. Medicare Program; Prospective Payment System and Consolidated Billing for Skilled Nursing Facilities (SNFs) for FY 2016, SNF Value-Based Purchasing Program, SNF Quality Reporting Program, and Staffing Data Collection. Final Rule. Fed Regist. 2015;80(149):46389-46477. PubMed

2. “Readmissions Reduction Program,” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html. Accessed November 5, 2015.

3. Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 1999;281:613-620. PubMed

4. Naylor MD, Brooten DA, Campbell RL, Maislin G, McCauley KM, Schwartz JS. Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:675-684. PubMed

5. Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1822-1828. PubMed

6. CMS Office of Information Products and Data Analytics. National Medicare Readmission Findings: Recent Data and Trends. 2012. http://www.academyhealth.org/files/2012/sunday/brennan.pdf. Accessed on September 21, 2015.

7. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, CMS Innovation Center. Initiative to Reduce Avoidable Hospitalizations among Nursing Facility Residents. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/rahnfr/. Accessed on November 5, 2015.

8. Unroe KT, Nazir A, Holtz LR, et al. The Optimizing Patient Transfers, Impacting Medical Quality and Improving Symptoms: Transforming Institutional Care Approach: Preliminary data from the implementation of a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services nursing facility demonstration project. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;65:165-169. PubMed

9. Ingber MJ, Feng Z, Khatstsky G, et al. Evaluation of the Initiative to Reduce Avoidable Hospitalizations among Nursing Facility Residents: Final Annual Report Project Year 3. Waltham, MA: RTI International, RTI Project Number 0212790.006, January 2016.

10. Ouslander JG, Lamb G, Tappen R, et al. Interventions to reduce hospitalizations from nursing homes: Evaluation of the INTERACT II collaborative quality improvement project. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011:59:745-753. PubMed

11. Kim L, Kou L, Hu B, Gorodeski EZ, Rothberg M. Impact of a Connected Care Model on 30-Day Readmission Rates from Skilled Nursing Facilities. J Hosp Med. 2017;12:238-244. PubMed

12. Kansagara D, Englander H, Salanitro A, et al. Risk Prediction Models for Hospital Readmission: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2011;306(15):1688-1698. PubMed

13. Averill RF, Goldfield N, Hughes JS, et al. All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (APR-DRGs): Methodology Overview. 3M Health Information Systems Document GRP-041 (2003). https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/APR-DRGsV20MethodologyOverviewandBibliography.pdf. Accessed on November 5, 2015.

14. StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.

15. Cebul RD, Rebitzer JB, Taylor LJ, Votruba ME. Organizational fragmentation and care quality in the U.S. healthcare system. J Econ Perspect. 2008;22(4):93-113. PubMed

16. Tjia J, Bonner A, Briesacher BA, McGee S, Terrill E, Miller K. Medication discrepancies upon hospital to skilled nursing facility transitions. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:630-635. PubMed

17. Desai R, Williams CE, Greene SB, Pierson S, Hansen RA. Medication errors during patient transitions into nursing homes: characteristics and association with patient harm. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2011;9:413-422. PubMed

18. Chhabra PT, Rattinger GB, Dutcher SK, Hare ME, Parsons KL, Zuckerman IH. Medication reconciliation during the transition to and from long-term care settings: a systematic review. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2012;8(1):60-75. PubMed

19. Rahman M, Foster AD, Grabowski DC, Zinn JS, Mor V. Effect of hospital-SNF referral linkages on rehospitalization. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6, pt 1):1898-1919. PubMed

20. Schoenfeld AJ, Zhang X, Grabowski DC, Mor V, Weissman JS, Rahman M. Hospital-skilled nursing facility referral linkage reduces readmission rates among Medicare patients receiving major surgery. Surgery. 2016;159(5):1461-1468. PubMed

21. Rahman M, McHugh J, Gozalo P, Ackerly DC, Mor V. The Contribution of Skilled Nursing Facilities to Hospitals’ Readmission Rate. HSR: Health Services Research. 2017;52(2):656-675. PubMed

22. Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. New Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418-1428. PubMed

23. Hasan O, Meltzer DO, Shaykevich SA, et al. Hospital readmission in general medicine patients: a prediction model. J Hosp Med. 2010;25(3)211-219. PubMed

24. Allaudeen N, Vidyarhi A, Masella J, Auerbach A. Redefining readmission risk factors for general medicine patients. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(2):54-60. PubMed

25. Van Walraven C, Wong J, Forster AJ. LACE+ index: extension of a validated index to predict early death or urgent readmission after discharge using administrative data. Open Med. 2012;6(3):e80-e90. PubMed

26. Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014, Pub. L. No. 113-93, 128 Stat. 1040 (April 1, 2014). https://www.congress.gov/113/plaws/publ93/PLAW-113publ93.pdf. Accessed on October 3, 2015.

Public reporting of readmission rates on the Nursing Home Compare website is mandated to begin on October 1, 2017, with skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) set to receive a Medicare bonus or penalty beginning a year later.1 The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) began public reporting of hospitals’ 30-day readmission rates for selected conditions in 2009, and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 mandated financial penalties for excess readmissions through the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program.2 In response, most hospitals have focused on patients who return home following discharge. Innovative interventions have proven successful, such as the Transitional Care model developed by Naylor and Coleman’s Care Transitions Intervention.3-5 Approximately 20% of Medicare beneficiaries are discharged from hospitals to SNFs, and these patients have higher readmission rates than those discharged home. CMS reported that in 2010, 23.3% of those with an SNF stay were readmitted within 30 days, compared with 18.8% for those with other discharge dispositions.6

Some work has been undertaken in this arena. In 2012, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) and the Medicare-Medicaid Coordination Office jointly launched the Initiative to Reduce Avoidable Hospitalizations among Nursing Facility Residents.7 This partnership established 7 Enhanced Care and Coordination Provider organizations and was designed to improve care by reducing hospitalizations among long-stay, dual-eligible nursing facility residents at 143 nursing homes in 7 states.8 At the time of the most recent project report, there were mixed results regarding program effects on hospitalizations and spending, with 2 states showing strongly positive patterns, 3 states with reductions that were consistent though not statistically strong, and mixed results in the remaining states. Quality measures did not show any pattern suggesting a program effect.9 Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers (INTERACT) II was a 6-month, collaborative, quality-improvement project implemented in 2009 at 30 nursing homes in 3 states.10 The project evaluation found a statistically significant, 17% decrease in self-reported hospital admissions among the 25 SNFs that completed the intervention, compared with the same 6 months in the prior year. The Cleveland Clinic recently reported favorable results implementing its Connected Care model, which relied on staff physicians and advanced practice professionals to visit patients 4 to 5 times per week and be on call 24/7 at 7 intervention SNFs.11 Through this intervention, it successfully reduced its 30-day hospital readmission rate from SNFs from 28.1% to 21.7% (P < 0.001), and the authors posed the question as to whether its model and results were reproducible in other healthcare systems.

Herein, we report on the results of a collaborative initiative named the Enhanced Care Program (ECP), which offers the services of clinical providers and administrative staff to assist with the care of patients at 8 partner SNFs. The 3 components of ECP (described below) were specifically designed to address commonly recognized gaps and opportunities in routine SNF care. In contrast to the Cleveland Clinic’s Connected Care model (which involved hospital-employed physicians serving as the SNF attendings and excluded patients followed by their own physicians), ECP was designed to integrate into a pluralistic, community model whereby independent physicians continued to follow their own patients at the SNFs. The Connected Care analysis compared participating versus nonparticipating SNFs; both the Connected Care model and the INTERACT II evaluation relied on pre–post comparisons; the CMMI evaluation used a difference-in-differences model to compare the outcomes of the program SNFs with those of a matched comparison group of nonparticipating SNFs. The evaluation of ECP differs from these other initiatives, using a concurrent comparison group of patients discharged to the same SNFs but who were not enrolled in ECP.

METHODS

Setting

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center (CSMC) is an 850-bed, acute care facility located in an urban area of Los Angeles. Eight SNFs, ranging in size from 49 to 150 beds and located between 0.6 and 2.2 miles from CSMC, were invited to partner with the ECP. The physician community encompasses more than 2000 physicians on the medical staff, including private practitioners, nonteaching hospitalists, full-time faculty hospitalists, and faculty specialists.

Study Design and Patients

This was an observational, retrospective cohort analysis of 30-day same-hospital readmissions among 3951 patients discharged from CSMC to 8 SNFs between January 1, 2014, and June 30, 2015. A total of 2394 patients were enrolled in the ECP, and 1557 patients were not enrolled.

ECP Enrollment Protocol

Every patient discharged from CSMC to 1 of the 8 partner SNFs was eligible to participate in the program. To respect the autonomy of the SNF attending physicians and to facilitate a collaborative relationship, the decision to enroll a patient in the ECP rested with the SNF attending physician. The ECP team maintained a database that tracked whether each SNF attending physician (1) opted to automatically enroll all his or her patients in the ECP, (2) opted to enroll patients on a case-by-case basis (in which case an ECP nurse practitioner [N

Program Description

Patients enrolled in the ECP experienced the standard care provided by the SNF staff and attending physicians plus a clinical care program delivered by 9 full-time NPs, 1 full-time pharmacist, 1 pharmacy technician, 1 full-time nurse educator, a program administrator, and a medical director.

The program included the following 3 major components:

1. Direct patient care and 24/7 NP availability: Program enrollment began with an on-site, bedside evaluation by an ECP NP at the SNF within 24 hours of arrival and continued with weekly NP rounding (or more frequently, if clinically indicated) on the patient. Each encounter included a review of the medical record; a dialogue with the patient’s SNF attending physician to formulate treatment plans and place orders; discussions with nurses, family members, and other caregivers; and documentation in the medical record. The ECP team was on-site at the SNFs 7 days a week and on call 24/7 to address questions and concerns. Patients remained enrolled in the ECP from SNF admission to discharge even if their stay extended beyond 30 days.

2. Medication reconciliation: The ECP pharmacy team completed a review of a patient’s SNF medication administration record (MAR) within 72 hours of SNF admission. This process involved the pharmacy technician gathering medication lists from the SNFs and CSMC and providing this information to the pharmacist for a medication reconciliation and clinical evaluation. Discrepancies and pharmacist recommendations were communicated to the ECP NPs, and all identified issues were resolved.

3. Educational in-services: Building upon the INTERACT II model, the ECP team identified high-yield, clinically relevant topics, which the ECP nurse educator turned into monthly educational sessions for the SNF nursing staff at each of the participating SNFs.10

Primary Outcome Measure

An inpatient readmission to CSMC within 30 days of the hospital discharge date was counted as a readmission, whether the patient returned directly from an SNF or was readmitted from home after an SNF discharge.

Data

ECP patients were identified using a log maintained by the ECP program manager. Non-ECP patients discharged to the same SNFs during the study period were identified from CSMC’s electronic registry of SNF discharges. Covariates known to be associated with increased risk of 30-day readmission were obtained from CSMC’s electronic data warehouse, including demographic information, length of stay (LOS) of index hospitalization, and payer.12 Eleven clinical service lines represented patients’ clinical conditions based on Medicare-Severity Diagnosis-Related groupings. The discharge severity of illness score was calculated using 3M All Patients Refined Diagnosis Related Group software, version 33.13

Analysis

Characteristics of the ECP and non-ECP patients were compared using the χ2 test. A multivariable logistic regression model with fixed effects for SNF was created to determine the program’s impact on 30-day hospital readmission, adjusting for patient characteristics. The Pearson χ2 goodness-of-fit test and the link test for model specification were used to evaluate model specification. The sensitivity of the results to differences in patient characteristics was assessed in 2 ways. First, the ECP and non-ECP populations were stratified based on race and/or ethnicity and payer, and the multivariable regression model was run within the strata associated with the highest readmission rates. Second, a propensity analysis using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) was performed to control for group differences. Results of all comparisons were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05. Stata version 13 was used to perform the main analyses.14 The propensity analysis was conducted using R version 3.2.3. The CSMC Institutional Review Board (IRB) determined that this study qualified as a quality-improvement activity and did not require IRB approval or exemption.

RESULTS

The average unadjusted 30-day readmission rate for ECP patients over the 18-month study period was 17.2%, compared to 23.0% for patients not enrolled in ECP (P < 0.001) (Figure 1). After adjusting for patient characteristics, ECP patients had 29% lower odds (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.60-0.85) of being readmitted to the medical center within 30 days than non-ECP patients at the same SNFs. The characteristics of the ECP and comparison patient cohorts are shown in Table 1. There were significant differences in sociodemographic characteristics: The ECP group had a higher proportion of non-Hispanic white patients, while the comparison group had a higher proportion of patients who were African American or Hispanic. ECP patients were more likely to prefer speaking English, while Russian, Farsi, and Spanish were preferred more frequently in the comparison group. There were also differences in payer mix, with the ECP group including proportionately more Medicare fee-for-service (52.9% vs 35.0%, P < 0.001), while the comparison group had a correspondingly larger proportion of dual-eligible (Medicare and Medicaid) patients (55.0% vs 35.1%, P < 0.001).

The largest clinical differences observed between the ECP and non-ECP groups were the proportions of patients in the clinical service lines of orthopedic surgery (28.7% vs 21.1%, P < 0.001), medical cardiology (7.4% vs 9.7%, P < 0.001), and surgery other than general surgery (5.8% vs 9.2%, P < 0.001). Despite these differences in case mix, no differences were seen between the 2 groups in discharge severity of illness or LOS of the index hospitalization. The distribution of index hospital LOS by quartile was the same, with the exception that the ECP group had a higher proportion of patients with longer LOS.

Sensitivity Analyses

The results were robust when tested within strata of the study population, including analyses limited to dual-eligible patients, African American patients, patients admitted to all except the highest volume facility, and patients admitted to any service line other than orthopedic surgery. Similar results were obtained when the study population was restricted to patients living within the medical center’s primary service area and to patients living in zip codes in which the proportion of adults living in households with income below 100% of the poverty level was 15% or greater (see Supplementary Material for results).

The effect of the program on readmission was also consistent when the full logistic regression model was run with IPTW using the propensity score. The evaluation of standardized cluster differences between the ECP and non-ECP groups before and after IPTW showed that the differences were reduced to <10% for being African American; speaking Russian or Farsi; having dual-eligible insurance coverage; having orthopedic surgery; being discharged from the clinical service lines of gastroenterology, pulmonary, other surgery, and other services; and having an index hospital LOS of 4 to 5 days or 10 or more days (results are provided in the Supplementary Material).

DISCUSSION

Hospitals continue to experience significant pressure to manage LOS, and SNFs and hospitals are being held accountable for readmission rates. The setting of this study is representative of many large, urban hospitals in the United States whose communities include a heterogeneous mix of hospitalists, primary care physicians who follow their patients in SNFs, and independent SNFs.15 The current regulations have not kept up with the increasing acuity and complexity of SNF patients. Specifically, Medicare guidelines allow the SNF attending physician up to 72 hours to complete a history and physical (or 7 days if he or she was the hospital attending physician for the index hospitalization) and only require monthly follow-up visits. It is the opinion of the ECP designers that these relatively lax requirements present unnecessary risk for vulnerable patients. While the INTERACT II model was focused largely on educational initiatives (with an advanced practice nurse available in a consultative role, as needed), the central tenet of ECP was similar to the Connected Care model in that the focus was on adding an extra layer of direct clinical support. Protocols that provided timely initial assessments by an NP (within 24 hours), weekly NP rounding (at a minimum), and 24/7 on-call availability all contributed to helping patients stay on track. Although the ECP had patients visited less frequently than the Connected Care model, and the Cleveland Clinic started with a higher baseline 30-day readmission rate from SNFs, similar overall reductions in 30-day readmissions were observed. The key point from both initiatives is that an increase in clinical touchpoints and ease of access to clinicians generates myriad opportunities to identify and address small issues before they become clinical emergencies requiring hospital transfers and readmissions.

Correcting medication discrepancies between hospital discharge summaries and SNF admission orders through a systematic medication reconciliation using a clinical pharmacist has previously been shown to improve outcomes.16-18 The ECP pharmacy technician and ECP clinical pharmacist discovered and corrected errors on a daily basis that ranged from incidental to potentially life-threatening. If the SNF staff does not provide the patient’s MAR within 48 hours of arrival, the pharmacy technician contacts the facility to obtain the information. As a result, all patients enrolled in the ECP during the study period received this intervention (unless they were rehospitalized or left the SNF before the process was completed), and 54% of ECP patients required some form of intervention after medication reconciliation was completed (data not shown).

This type of program requires hospital leadership and SNF administrators to be fully committed to developing strong working relationships, and in fact, there is evidence that SNF baseline readmission rates have a greater influence on patients’ risk of rehospitalization than the discharging hospital itself.19-21 Monthly educational in-services are delivered at the partner SNFs to enhance SNF nursing staff knowledge and clinical acumen. High-impact topics identified by the ECP team include the following: fall prevention, hand hygiene, venous thromboembolism, cardiovascular health, how to report change in condition, and advanced care planning, among others. While no formal pre–post assessments of the SNF nurses’ knowledge were conducted, a log of in-services was kept, subjective feedback was collected for performance improvement purposes, and continuing educational units were provided to the SNF nurses who attended.

This study has limitations. As a single-hospital study, generalizability may be limited. While adherence to the program components was closely monitored daily, service gaps may have occurred that were not captured. The program design makes it difficult to quantify the relative impact of the 3 program components on the outcome. Furthermore, the study was observational, so the differences in readmission rates may have been due to unmeasured variables. The decision to enroll patients in the ECP was made by each patient’s SNF attending physician, and those who chose to (or not to) participate in the program may manifest other, unmeasured practice patterns that made readmissions more or less likely. Participating physicians also had the option to enroll their patients on a case-by-case basis, introducing further potential bias in patient selection; however, <5% of physicians exercised this option. Patients may have also been readmitted to hospitals other than CSMC, producing an observed readmission rate for 1 or both groups that underrepresents the true outcome. On this point, while we did not systematically track these other-hospital readmissions for both groups, there is no reason to believe that this occurred preferentially for ECP or non-ECP patients.

Multiple sensitivity analyses were performed to address the observed differences between ECP and non-ECP patients. These included stratified examinations of variables differing between populations, examination of clustering effects between SNFs, and an analysis adjusted for the propensity to be included in the ECP. The calculated effect of the intervention on readmission remained robust, although we acknowledge that differences in the populations may persist and have influenced the outcomes even after controlling for multiple variables.22-25

In conclusion, the results of this intervention are compelling and add to the growing body of literature suggesting that a comprehensive, multipronged effort to enhance clinical oversight and coordination of care for SNF patients can improve outcomes. Given CMS’s plans to report SNF readmission rates in 2017 followed by the application of financial incentives in 2018, a favorable climate currently exists for greater coordination between hospitals and SNFs.26 We are currently undertaking an economic evaluation of the program.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following people for their contributions: Mae Saunders, Rita Shane, Dr. Jon Kea, Miranda Li, the ECP NPs, the ECP pharmacy team, CSMC’s performance improvement team, and Alan Matus.

Disclosure

No conflicts of interest or disclosures.

Public reporting of readmission rates on the Nursing Home Compare website is mandated to begin on October 1, 2017, with skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) set to receive a Medicare bonus or penalty beginning a year later.1 The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) began public reporting of hospitals’ 30-day readmission rates for selected conditions in 2009, and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 mandated financial penalties for excess readmissions through the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program.2 In response, most hospitals have focused on patients who return home following discharge. Innovative interventions have proven successful, such as the Transitional Care model developed by Naylor and Coleman’s Care Transitions Intervention.3-5 Approximately 20% of Medicare beneficiaries are discharged from hospitals to SNFs, and these patients have higher readmission rates than those discharged home. CMS reported that in 2010, 23.3% of those with an SNF stay were readmitted within 30 days, compared with 18.8% for those with other discharge dispositions.6

Some work has been undertaken in this arena. In 2012, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) and the Medicare-Medicaid Coordination Office jointly launched the Initiative to Reduce Avoidable Hospitalizations among Nursing Facility Residents.7 This partnership established 7 Enhanced Care and Coordination Provider organizations and was designed to improve care by reducing hospitalizations among long-stay, dual-eligible nursing facility residents at 143 nursing homes in 7 states.8 At the time of the most recent project report, there were mixed results regarding program effects on hospitalizations and spending, with 2 states showing strongly positive patterns, 3 states with reductions that were consistent though not statistically strong, and mixed results in the remaining states. Quality measures did not show any pattern suggesting a program effect.9 Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers (INTERACT) II was a 6-month, collaborative, quality-improvement project implemented in 2009 at 30 nursing homes in 3 states.10 The project evaluation found a statistically significant, 17% decrease in self-reported hospital admissions among the 25 SNFs that completed the intervention, compared with the same 6 months in the prior year. The Cleveland Clinic recently reported favorable results implementing its Connected Care model, which relied on staff physicians and advanced practice professionals to visit patients 4 to 5 times per week and be on call 24/7 at 7 intervention SNFs.11 Through this intervention, it successfully reduced its 30-day hospital readmission rate from SNFs from 28.1% to 21.7% (P < 0.001), and the authors posed the question as to whether its model and results were reproducible in other healthcare systems.

Herein, we report on the results of a collaborative initiative named the Enhanced Care Program (ECP), which offers the services of clinical providers and administrative staff to assist with the care of patients at 8 partner SNFs. The 3 components of ECP (described below) were specifically designed to address commonly recognized gaps and opportunities in routine SNF care. In contrast to the Cleveland Clinic’s Connected Care model (which involved hospital-employed physicians serving as the SNF attendings and excluded patients followed by their own physicians), ECP was designed to integrate into a pluralistic, community model whereby independent physicians continued to follow their own patients at the SNFs. The Connected Care analysis compared participating versus nonparticipating SNFs; both the Connected Care model and the INTERACT II evaluation relied on pre–post comparisons; the CMMI evaluation used a difference-in-differences model to compare the outcomes of the program SNFs with those of a matched comparison group of nonparticipating SNFs. The evaluation of ECP differs from these other initiatives, using a concurrent comparison group of patients discharged to the same SNFs but who were not enrolled in ECP.

METHODS

Setting

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center (CSMC) is an 850-bed, acute care facility located in an urban area of Los Angeles. Eight SNFs, ranging in size from 49 to 150 beds and located between 0.6 and 2.2 miles from CSMC, were invited to partner with the ECP. The physician community encompasses more than 2000 physicians on the medical staff, including private practitioners, nonteaching hospitalists, full-time faculty hospitalists, and faculty specialists.

Study Design and Patients

This was an observational, retrospective cohort analysis of 30-day same-hospital readmissions among 3951 patients discharged from CSMC to 8 SNFs between January 1, 2014, and June 30, 2015. A total of 2394 patients were enrolled in the ECP, and 1557 patients were not enrolled.

ECP Enrollment Protocol

Every patient discharged from CSMC to 1 of the 8 partner SNFs was eligible to participate in the program. To respect the autonomy of the SNF attending physicians and to facilitate a collaborative relationship, the decision to enroll a patient in the ECP rested with the SNF attending physician. The ECP team maintained a database that tracked whether each SNF attending physician (1) opted to automatically enroll all his or her patients in the ECP, (2) opted to enroll patients on a case-by-case basis (in which case an ECP nurse practitioner [N

Program Description

Patients enrolled in the ECP experienced the standard care provided by the SNF staff and attending physicians plus a clinical care program delivered by 9 full-time NPs, 1 full-time pharmacist, 1 pharmacy technician, 1 full-time nurse educator, a program administrator, and a medical director.

The program included the following 3 major components:

1. Direct patient care and 24/7 NP availability: Program enrollment began with an on-site, bedside evaluation by an ECP NP at the SNF within 24 hours of arrival and continued with weekly NP rounding (or more frequently, if clinically indicated) on the patient. Each encounter included a review of the medical record; a dialogue with the patient’s SNF attending physician to formulate treatment plans and place orders; discussions with nurses, family members, and other caregivers; and documentation in the medical record. The ECP team was on-site at the SNFs 7 days a week and on call 24/7 to address questions and concerns. Patients remained enrolled in the ECP from SNF admission to discharge even if their stay extended beyond 30 days.

2. Medication reconciliation: The ECP pharmacy team completed a review of a patient’s SNF medication administration record (MAR) within 72 hours of SNF admission. This process involved the pharmacy technician gathering medication lists from the SNFs and CSMC and providing this information to the pharmacist for a medication reconciliation and clinical evaluation. Discrepancies and pharmacist recommendations were communicated to the ECP NPs, and all identified issues were resolved.

3. Educational in-services: Building upon the INTERACT II model, the ECP team identified high-yield, clinically relevant topics, which the ECP nurse educator turned into monthly educational sessions for the SNF nursing staff at each of the participating SNFs.10

Primary Outcome Measure

An inpatient readmission to CSMC within 30 days of the hospital discharge date was counted as a readmission, whether the patient returned directly from an SNF or was readmitted from home after an SNF discharge.

Data

ECP patients were identified using a log maintained by the ECP program manager. Non-ECP patients discharged to the same SNFs during the study period were identified from CSMC’s electronic registry of SNF discharges. Covariates known to be associated with increased risk of 30-day readmission were obtained from CSMC’s electronic data warehouse, including demographic information, length of stay (LOS) of index hospitalization, and payer.12 Eleven clinical service lines represented patients’ clinical conditions based on Medicare-Severity Diagnosis-Related groupings. The discharge severity of illness score was calculated using 3M All Patients Refined Diagnosis Related Group software, version 33.13

Analysis

Characteristics of the ECP and non-ECP patients were compared using the χ2 test. A multivariable logistic regression model with fixed effects for SNF was created to determine the program’s impact on 30-day hospital readmission, adjusting for patient characteristics. The Pearson χ2 goodness-of-fit test and the link test for model specification were used to evaluate model specification. The sensitivity of the results to differences in patient characteristics was assessed in 2 ways. First, the ECP and non-ECP populations were stratified based on race and/or ethnicity and payer, and the multivariable regression model was run within the strata associated with the highest readmission rates. Second, a propensity analysis using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) was performed to control for group differences. Results of all comparisons were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05. Stata version 13 was used to perform the main analyses.14 The propensity analysis was conducted using R version 3.2.3. The CSMC Institutional Review Board (IRB) determined that this study qualified as a quality-improvement activity and did not require IRB approval or exemption.

RESULTS

The average unadjusted 30-day readmission rate for ECP patients over the 18-month study period was 17.2%, compared to 23.0% for patients not enrolled in ECP (P < 0.001) (Figure 1). After adjusting for patient characteristics, ECP patients had 29% lower odds (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.60-0.85) of being readmitted to the medical center within 30 days than non-ECP patients at the same SNFs. The characteristics of the ECP and comparison patient cohorts are shown in Table 1. There were significant differences in sociodemographic characteristics: The ECP group had a higher proportion of non-Hispanic white patients, while the comparison group had a higher proportion of patients who were African American or Hispanic. ECP patients were more likely to prefer speaking English, while Russian, Farsi, and Spanish were preferred more frequently in the comparison group. There were also differences in payer mix, with the ECP group including proportionately more Medicare fee-for-service (52.9% vs 35.0%, P < 0.001), while the comparison group had a correspondingly larger proportion of dual-eligible (Medicare and Medicaid) patients (55.0% vs 35.1%, P < 0.001).

The largest clinical differences observed between the ECP and non-ECP groups were the proportions of patients in the clinical service lines of orthopedic surgery (28.7% vs 21.1%, P < 0.001), medical cardiology (7.4% vs 9.7%, P < 0.001), and surgery other than general surgery (5.8% vs 9.2%, P < 0.001). Despite these differences in case mix, no differences were seen between the 2 groups in discharge severity of illness or LOS of the index hospitalization. The distribution of index hospital LOS by quartile was the same, with the exception that the ECP group had a higher proportion of patients with longer LOS.

Sensitivity Analyses

The results were robust when tested within strata of the study population, including analyses limited to dual-eligible patients, African American patients, patients admitted to all except the highest volume facility, and patients admitted to any service line other than orthopedic surgery. Similar results were obtained when the study population was restricted to patients living within the medical center’s primary service area and to patients living in zip codes in which the proportion of adults living in households with income below 100% of the poverty level was 15% or greater (see Supplementary Material for results).

The effect of the program on readmission was also consistent when the full logistic regression model was run with IPTW using the propensity score. The evaluation of standardized cluster differences between the ECP and non-ECP groups before and after IPTW showed that the differences were reduced to <10% for being African American; speaking Russian or Farsi; having dual-eligible insurance coverage; having orthopedic surgery; being discharged from the clinical service lines of gastroenterology, pulmonary, other surgery, and other services; and having an index hospital LOS of 4 to 5 days or 10 or more days (results are provided in the Supplementary Material).

DISCUSSION

Hospitals continue to experience significant pressure to manage LOS, and SNFs and hospitals are being held accountable for readmission rates. The setting of this study is representative of many large, urban hospitals in the United States whose communities include a heterogeneous mix of hospitalists, primary care physicians who follow their patients in SNFs, and independent SNFs.15 The current regulations have not kept up with the increasing acuity and complexity of SNF patients. Specifically, Medicare guidelines allow the SNF attending physician up to 72 hours to complete a history and physical (or 7 days if he or she was the hospital attending physician for the index hospitalization) and only require monthly follow-up visits. It is the opinion of the ECP designers that these relatively lax requirements present unnecessary risk for vulnerable patients. While the INTERACT II model was focused largely on educational initiatives (with an advanced practice nurse available in a consultative role, as needed), the central tenet of ECP was similar to the Connected Care model in that the focus was on adding an extra layer of direct clinical support. Protocols that provided timely initial assessments by an NP (within 24 hours), weekly NP rounding (at a minimum), and 24/7 on-call availability all contributed to helping patients stay on track. Although the ECP had patients visited less frequently than the Connected Care model, and the Cleveland Clinic started with a higher baseline 30-day readmission rate from SNFs, similar overall reductions in 30-day readmissions were observed. The key point from both initiatives is that an increase in clinical touchpoints and ease of access to clinicians generates myriad opportunities to identify and address small issues before they become clinical emergencies requiring hospital transfers and readmissions.

Correcting medication discrepancies between hospital discharge summaries and SNF admission orders through a systematic medication reconciliation using a clinical pharmacist has previously been shown to improve outcomes.16-18 The ECP pharmacy technician and ECP clinical pharmacist discovered and corrected errors on a daily basis that ranged from incidental to potentially life-threatening. If the SNF staff does not provide the patient’s MAR within 48 hours of arrival, the pharmacy technician contacts the facility to obtain the information. As a result, all patients enrolled in the ECP during the study period received this intervention (unless they were rehospitalized or left the SNF before the process was completed), and 54% of ECP patients required some form of intervention after medication reconciliation was completed (data not shown).

This type of program requires hospital leadership and SNF administrators to be fully committed to developing strong working relationships, and in fact, there is evidence that SNF baseline readmission rates have a greater influence on patients’ risk of rehospitalization than the discharging hospital itself.19-21 Monthly educational in-services are delivered at the partner SNFs to enhance SNF nursing staff knowledge and clinical acumen. High-impact topics identified by the ECP team include the following: fall prevention, hand hygiene, venous thromboembolism, cardiovascular health, how to report change in condition, and advanced care planning, among others. While no formal pre–post assessments of the SNF nurses’ knowledge were conducted, a log of in-services was kept, subjective feedback was collected for performance improvement purposes, and continuing educational units were provided to the SNF nurses who attended.

This study has limitations. As a single-hospital study, generalizability may be limited. While adherence to the program components was closely monitored daily, service gaps may have occurred that were not captured. The program design makes it difficult to quantify the relative impact of the 3 program components on the outcome. Furthermore, the study was observational, so the differences in readmission rates may have been due to unmeasured variables. The decision to enroll patients in the ECP was made by each patient’s SNF attending physician, and those who chose to (or not to) participate in the program may manifest other, unmeasured practice patterns that made readmissions more or less likely. Participating physicians also had the option to enroll their patients on a case-by-case basis, introducing further potential bias in patient selection; however, <5% of physicians exercised this option. Patients may have also been readmitted to hospitals other than CSMC, producing an observed readmission rate for 1 or both groups that underrepresents the true outcome. On this point, while we did not systematically track these other-hospital readmissions for both groups, there is no reason to believe that this occurred preferentially for ECP or non-ECP patients.

Multiple sensitivity analyses were performed to address the observed differences between ECP and non-ECP patients. These included stratified examinations of variables differing between populations, examination of clustering effects between SNFs, and an analysis adjusted for the propensity to be included in the ECP. The calculated effect of the intervention on readmission remained robust, although we acknowledge that differences in the populations may persist and have influenced the outcomes even after controlling for multiple variables.22-25

In conclusion, the results of this intervention are compelling and add to the growing body of literature suggesting that a comprehensive, multipronged effort to enhance clinical oversight and coordination of care for SNF patients can improve outcomes. Given CMS’s plans to report SNF readmission rates in 2017 followed by the application of financial incentives in 2018, a favorable climate currently exists for greater coordination between hospitals and SNFs.26 We are currently undertaking an economic evaluation of the program.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following people for their contributions: Mae Saunders, Rita Shane, Dr. Jon Kea, Miranda Li, the ECP NPs, the ECP pharmacy team, CSMC’s performance improvement team, and Alan Matus.

Disclosure

No conflicts of interest or disclosures.

1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS. Medicare Program; Prospective Payment System and Consolidated Billing for Skilled Nursing Facilities (SNFs) for FY 2016, SNF Value-Based Purchasing Program, SNF Quality Reporting Program, and Staffing Data Collection. Final Rule. Fed Regist. 2015;80(149):46389-46477. PubMed

2. “Readmissions Reduction Program,” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html. Accessed November 5, 2015.

3. Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 1999;281:613-620. PubMed

4. Naylor MD, Brooten DA, Campbell RL, Maislin G, McCauley KM, Schwartz JS. Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:675-684. PubMed

5. Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1822-1828. PubMed

6. CMS Office of Information Products and Data Analytics. National Medicare Readmission Findings: Recent Data and Trends. 2012. http://www.academyhealth.org/files/2012/sunday/brennan.pdf. Accessed on September 21, 2015.

7. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, CMS Innovation Center. Initiative to Reduce Avoidable Hospitalizations among Nursing Facility Residents. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/rahnfr/. Accessed on November 5, 2015.

8. Unroe KT, Nazir A, Holtz LR, et al. The Optimizing Patient Transfers, Impacting Medical Quality and Improving Symptoms: Transforming Institutional Care Approach: Preliminary data from the implementation of a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services nursing facility demonstration project. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;65:165-169. PubMed

9. Ingber MJ, Feng Z, Khatstsky G, et al. Evaluation of the Initiative to Reduce Avoidable Hospitalizations among Nursing Facility Residents: Final Annual Report Project Year 3. Waltham, MA: RTI International, RTI Project Number 0212790.006, January 2016.

10. Ouslander JG, Lamb G, Tappen R, et al. Interventions to reduce hospitalizations from nursing homes: Evaluation of the INTERACT II collaborative quality improvement project. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011:59:745-753. PubMed

11. Kim L, Kou L, Hu B, Gorodeski EZ, Rothberg M. Impact of a Connected Care Model on 30-Day Readmission Rates from Skilled Nursing Facilities. J Hosp Med. 2017;12:238-244. PubMed

12. Kansagara D, Englander H, Salanitro A, et al. Risk Prediction Models for Hospital Readmission: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2011;306(15):1688-1698. PubMed

13. Averill RF, Goldfield N, Hughes JS, et al. All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (APR-DRGs): Methodology Overview. 3M Health Information Systems Document GRP-041 (2003). https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/APR-DRGsV20MethodologyOverviewandBibliography.pdf. Accessed on November 5, 2015.

14. StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.

15. Cebul RD, Rebitzer JB, Taylor LJ, Votruba ME. Organizational fragmentation and care quality in the U.S. healthcare system. J Econ Perspect. 2008;22(4):93-113. PubMed

16. Tjia J, Bonner A, Briesacher BA, McGee S, Terrill E, Miller K. Medication discrepancies upon hospital to skilled nursing facility transitions. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:630-635. PubMed

17. Desai R, Williams CE, Greene SB, Pierson S, Hansen RA. Medication errors during patient transitions into nursing homes: characteristics and association with patient harm. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2011;9:413-422. PubMed

18. Chhabra PT, Rattinger GB, Dutcher SK, Hare ME, Parsons KL, Zuckerman IH. Medication reconciliation during the transition to and from long-term care settings: a systematic review. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2012;8(1):60-75. PubMed

19. Rahman M, Foster AD, Grabowski DC, Zinn JS, Mor V. Effect of hospital-SNF referral linkages on rehospitalization. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6, pt 1):1898-1919. PubMed

20. Schoenfeld AJ, Zhang X, Grabowski DC, Mor V, Weissman JS, Rahman M. Hospital-skilled nursing facility referral linkage reduces readmission rates among Medicare patients receiving major surgery. Surgery. 2016;159(5):1461-1468. PubMed

21. Rahman M, McHugh J, Gozalo P, Ackerly DC, Mor V. The Contribution of Skilled Nursing Facilities to Hospitals’ Readmission Rate. HSR: Health Services Research. 2017;52(2):656-675. PubMed

22. Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. New Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418-1428. PubMed

23. Hasan O, Meltzer DO, Shaykevich SA, et al. Hospital readmission in general medicine patients: a prediction model. J Hosp Med. 2010;25(3)211-219. PubMed

24. Allaudeen N, Vidyarhi A, Masella J, Auerbach A. Redefining readmission risk factors for general medicine patients. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(2):54-60. PubMed

25. Van Walraven C, Wong J, Forster AJ. LACE+ index: extension of a validated index to predict early death or urgent readmission after discharge using administrative data. Open Med. 2012;6(3):e80-e90. PubMed

26. Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014, Pub. L. No. 113-93, 128 Stat. 1040 (April 1, 2014). https://www.congress.gov/113/plaws/publ93/PLAW-113publ93.pdf. Accessed on October 3, 2015.

1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS. Medicare Program; Prospective Payment System and Consolidated Billing for Skilled Nursing Facilities (SNFs) for FY 2016, SNF Value-Based Purchasing Program, SNF Quality Reporting Program, and Staffing Data Collection. Final Rule. Fed Regist. 2015;80(149):46389-46477. PubMed

2. “Readmissions Reduction Program,” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html. Accessed November 5, 2015.

3. Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 1999;281:613-620. PubMed

4. Naylor MD, Brooten DA, Campbell RL, Maislin G, McCauley KM, Schwartz JS. Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:675-684. PubMed

5. Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1822-1828. PubMed

6. CMS Office of Information Products and Data Analytics. National Medicare Readmission Findings: Recent Data and Trends. 2012. http://www.academyhealth.org/files/2012/sunday/brennan.pdf. Accessed on September 21, 2015.

7. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, CMS Innovation Center. Initiative to Reduce Avoidable Hospitalizations among Nursing Facility Residents. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/rahnfr/. Accessed on November 5, 2015.

8. Unroe KT, Nazir A, Holtz LR, et al. The Optimizing Patient Transfers, Impacting Medical Quality and Improving Symptoms: Transforming Institutional Care Approach: Preliminary data from the implementation of a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services nursing facility demonstration project. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;65:165-169. PubMed

9. Ingber MJ, Feng Z, Khatstsky G, et al. Evaluation of the Initiative to Reduce Avoidable Hospitalizations among Nursing Facility Residents: Final Annual Report Project Year 3. Waltham, MA: RTI International, RTI Project Number 0212790.006, January 2016.

10. Ouslander JG, Lamb G, Tappen R, et al. Interventions to reduce hospitalizations from nursing homes: Evaluation of the INTERACT II collaborative quality improvement project. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011:59:745-753. PubMed

11. Kim L, Kou L, Hu B, Gorodeski EZ, Rothberg M. Impact of a Connected Care Model on 30-Day Readmission Rates from Skilled Nursing Facilities. J Hosp Med. 2017;12:238-244. PubMed

12. Kansagara D, Englander H, Salanitro A, et al. Risk Prediction Models for Hospital Readmission: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2011;306(15):1688-1698. PubMed

13. Averill RF, Goldfield N, Hughes JS, et al. All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (APR-DRGs): Methodology Overview. 3M Health Information Systems Document GRP-041 (2003). https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/APR-DRGsV20MethodologyOverviewandBibliography.pdf. Accessed on November 5, 2015.

14. StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.

15. Cebul RD, Rebitzer JB, Taylor LJ, Votruba ME. Organizational fragmentation and care quality in the U.S. healthcare system. J Econ Perspect. 2008;22(4):93-113. PubMed

16. Tjia J, Bonner A, Briesacher BA, McGee S, Terrill E, Miller K. Medication discrepancies upon hospital to skilled nursing facility transitions. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:630-635. PubMed

17. Desai R, Williams CE, Greene SB, Pierson S, Hansen RA. Medication errors during patient transitions into nursing homes: characteristics and association with patient harm. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2011;9:413-422. PubMed

18. Chhabra PT, Rattinger GB, Dutcher SK, Hare ME, Parsons KL, Zuckerman IH. Medication reconciliation during the transition to and from long-term care settings: a systematic review. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2012;8(1):60-75. PubMed

19. Rahman M, Foster AD, Grabowski DC, Zinn JS, Mor V. Effect of hospital-SNF referral linkages on rehospitalization. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6, pt 1):1898-1919. PubMed

20. Schoenfeld AJ, Zhang X, Grabowski DC, Mor V, Weissman JS, Rahman M. Hospital-skilled nursing facility referral linkage reduces readmission rates among Medicare patients receiving major surgery. Surgery. 2016;159(5):1461-1468. PubMed

21. Rahman M, McHugh J, Gozalo P, Ackerly DC, Mor V. The Contribution of Skilled Nursing Facilities to Hospitals’ Readmission Rate. HSR: Health Services Research. 2017;52(2):656-675. PubMed

22. Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. New Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418-1428. PubMed

23. Hasan O, Meltzer DO, Shaykevich SA, et al. Hospital readmission in general medicine patients: a prediction model. J Hosp Med. 2010;25(3)211-219. PubMed

24. Allaudeen N, Vidyarhi A, Masella J, Auerbach A. Redefining readmission risk factors for general medicine patients. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(2):54-60. PubMed

25. Van Walraven C, Wong J, Forster AJ. LACE+ index: extension of a validated index to predict early death or urgent readmission after discharge using administrative data. Open Med. 2012;6(3):e80-e90. PubMed

26. Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014, Pub. L. No. 113-93, 128 Stat. 1040 (April 1, 2014). https://www.congress.gov/113/plaws/publ93/PLAW-113publ93.pdf. Accessed on October 3, 2015.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Personalized Vascular Access Training

The Accreditation Counsel for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) states in its Program Requirements for Residency Education in Internal Medicine that all residents must develop technical proficiency in several procedures, including central venous line placement.1 Developing competency in common procedural skills has long been a part of medical training. The philosophy of see‐1, do‐1, teach‐1 is still the most common means by which most residents seek to obtain this proficiency, even though serious concerns have been raised about this approach.2 A typical first experience in central line placement usually involves an eager (or terrified) trainee making several clumsy attempts on an actual patient, under the hurried guidance of a senior resident who themselves received an unknown degree of training. In this scenario, rarely does standardized instruction, formal evaluation, or structured follow‐up occur.

A revitalized emphasis is now being placed on patient safety in healthcare, including an industry‐wide commitment to minimizing procedural complications. The most common complications associated to central line placement include vascular damage and catheter‐related bloodstream infections. A number of creative approaches are being developed to improve the quality of instruction on proper procedural techniques, all varying considerably in sophistication, scope, and rigor. Examples include the use of computer‐assisted methods for training ultrasound‐guided needle insertion techniques and ureteroscopy training, hands‐on training with synthetic models for thoracentesis training, video training, and uterine aspiration using papayas.311 Implicit in this trend is recognition that we, as educators, healthcare providers, and patient advocates, must design more cost effective and efficient ways to teach medical and surgical procedural techniques to clinicians.

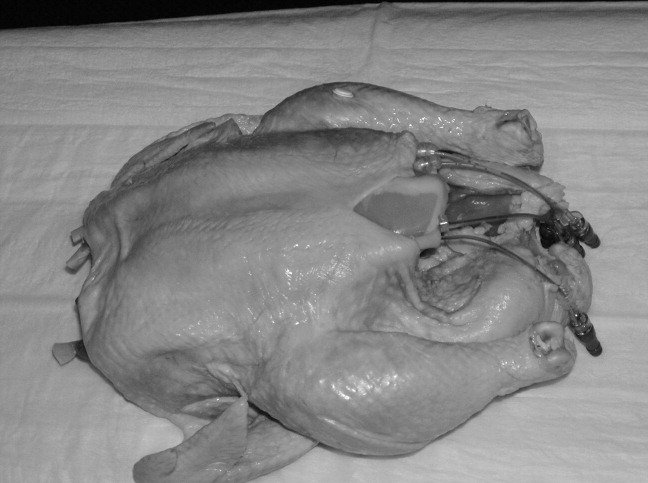

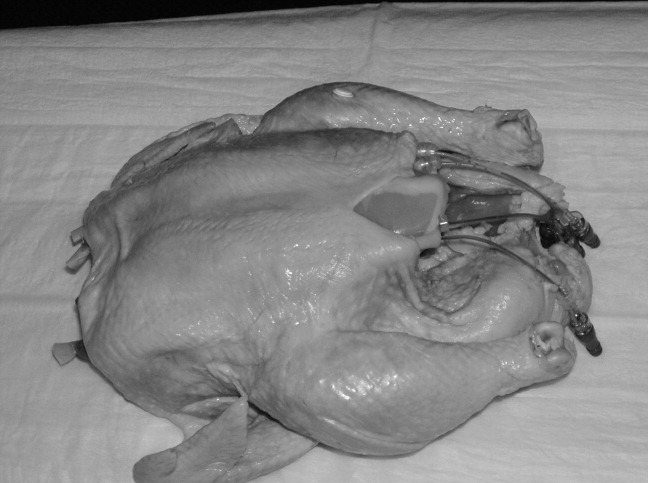

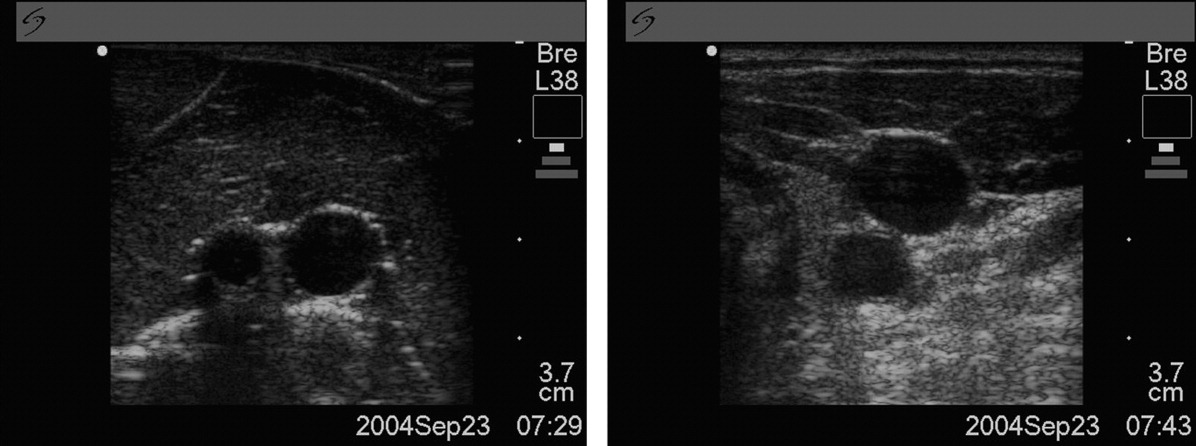

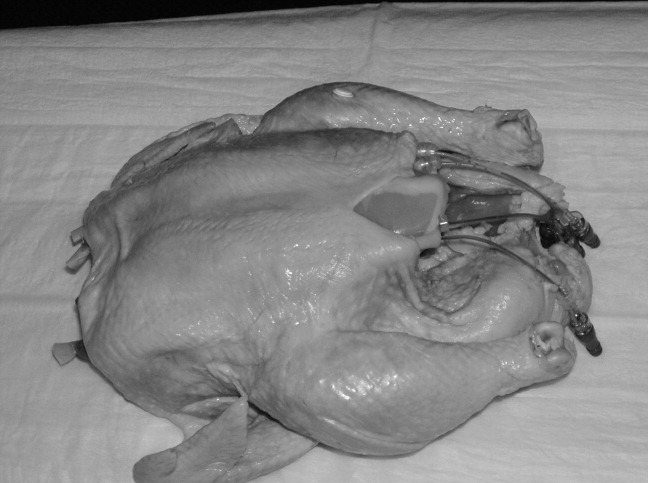

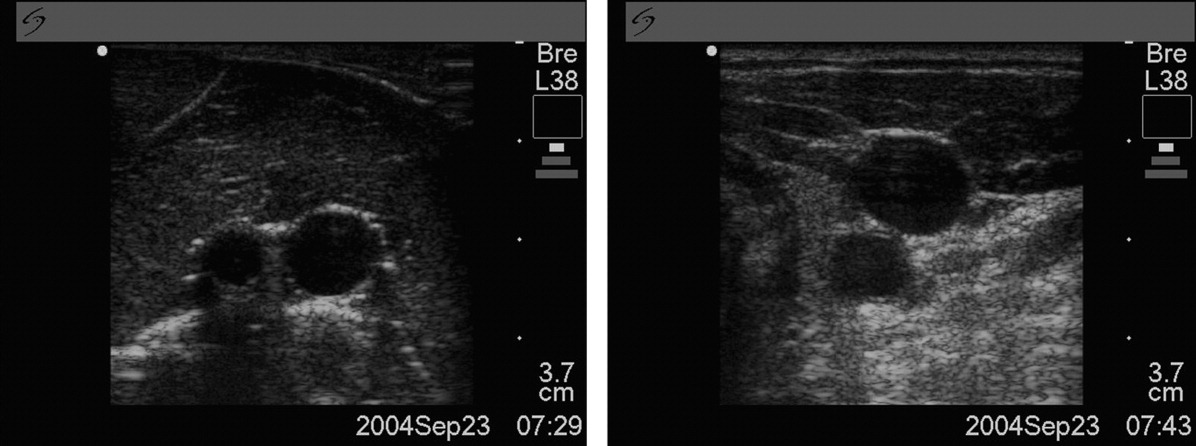

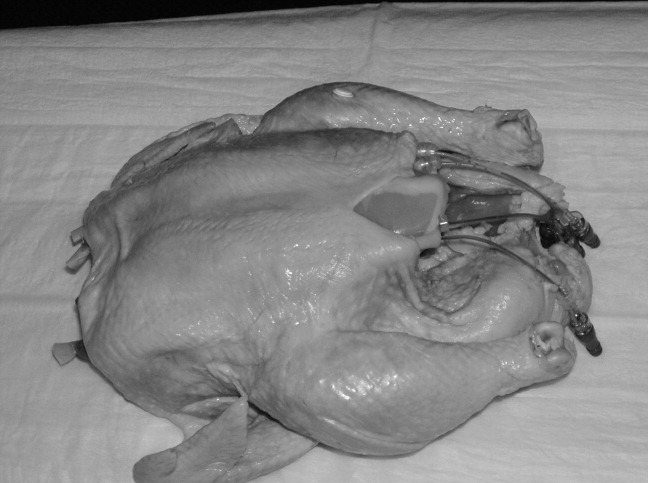

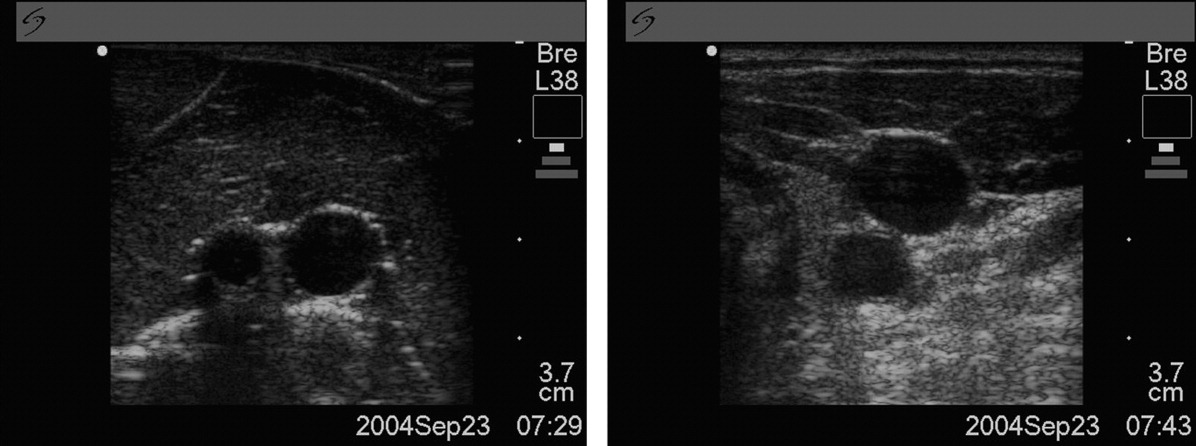

Our approach was previously described in phase I of the Procedural Patient Safety Initiative (PPSI).12 In PPSI‐I, we introduced a nonhuman tissue model (NHTM; Figure 1) as the basis for teaching physicians a more rigorous curriculum of essential central line placement skills. By way of brief review, the NHTMs were constructed by tunneling 0.2‐mm‐thick rubber tubing (vessels) lengthwise through raw, whole chickens purchased at the grocery store. The vessels were filled with colored water to simulate blood. The NHTM has several unique features, including: (1) realistic‐appearing vessels when viewed under ultrasound, which mimic the appearance of human internal jugular veins and carotid arteries (Figure 2); (2) tissue turgor and vessel composition that produce realistic pops and flashes upon puncture and allow for multiple cannulations; (3) the ability to perform a complete central line placement (including wire advancement, dilation, line insertion, suturing, and sterile dressing placement); (4) cost effectiveness relative to other commercially‐available products (each NHTM costs $120 and can withstand multiple cannulations over 2 days).1317 During the training sessions of Phase I, participants were oriented to the ultrasound machines, shown the contents of our central line kit, and taught the principles of wide sterile barriers (WSBs), sharps safety, and vascular access under real‐time ultrasound guidance. A self‐completed survey tool was filled out by the participants before and after the session that contained questions about their precourse baseline procedural experience, and their subjective comfort level with specific skills after the course. The results of our intervention, as measured by the responses to the survey, were significantly positive. We recognized the limitations of these results based on using subjective criteria to measure efficacy, a lack of follow‐up on participants' skill retention, and with no ultimate evaluation of procedural competency evaluations on actual patients (compared to an untrained control group).

Our ultimate goal is to validate a curriculum that will give trainees the necessary education and skills that enables them to make a smooth, competent, and complication‐free transition to live patient procedures. Phase II of PPSI is our next step toward this goal. In this study, we sought to measure the impact of intensive, 1:1 central line placement training with a proceduralist, objectively validate the efficacy of the NHTM and our training curriculum using a standardized 6‐point scoring scale and skilled evaluators, and to evaluate the degree of skill retention over time (decay). Our hypothesis was that the depth of skills' imprinting from a single, standardized training session would result in a significant improvement in measured procedure skills immediately after the trainee is taught the skills, and that the retention of these skills would be demonstrable when participants were reevaluated at a future date.

Methods