User login

A physician who feels hopeless and worthless and complains of pain

CASE Feeling hopeless

Dr. D, age 33, a white, male physician, presents with worsening depression, suicidal ideation, and somatic complaints. Dr. D says his personal life has become increasingly unhappy. He describes the pressures of a busy practice and conflict with his wife about his availability to her. He is feeling financial pressure and general disappointment about practicing medicine. Lack of recreational activities and close friends and absent spiritual life has led to feelings of isolation and depression.

Dr. D reports difficulty falling asleep, waking up early, and feeling fatigued. He describes obsessive, negative thoughts about his work and his personal life; he is anxious and tense. Dissatisfied and exhausted, he says he feels hopeless and empty and has become preoccupied with thoughts of death.

Dr. D describes musculoskeletal tension in the neck, shoulders, and face, with pain in the back of the neck. When the depressive symptoms or pain are particularly severe, he admits that his attention to critical information lapses. When interacting with his patients, he has missed important nuances about medication side effects, for example, frustrating his patients and himself.

Dr. D and his wife do not have children. His mother and paternal grandfather had depression, but Dr. D has no family history of suicide or drug or alcohol abuse. He has no significant medical conditions, and is not taking any medications. Dr. D drinks 1 or 2 cups of caffeinated coffee a day. He does not smoke, use recreational drugs, or drink alcohol regularly.

What would be your next step in treating Dr. D?

a) alert the state medical board about his suicidal ideation

b) recommend inpatient treatment

c) refer Dr. D to a clinician who has experience treating physicians

d) formulate a suicide risk assessment

The authors’ observation

Assessment of the suicidal physician is complex. It requires patience and ability to understand the source and the extent of the physician’s desperation and suffering. Not all psychiatrists are well suited to working with patients who also are peers. An experienced clinician, who has confronted the challenges of practice and treated individuals from many professions, could be better equipped than a recent graduate. Physician− patients might not be forthcoming about the extent of their suicidal thinking, because they fear involuntary hospitalization and jeopardizing their career.1

The evaluating clinician must be thorough and clear, and able to facilitate a trusting relationship. The ill physician should be encouraged to express suicidal ideation freely—without judgments, restrictions, or threats—to a trusted psychiatrist. Questions should be clear without possibility of misinterpretation. Ask:

• “Do you have thoughts of death, dying, or wanting to be dead?”

• “Do you think about suicide?”

• “Do you feel you might act on those thoughts?”

• “What keeps you safe?”

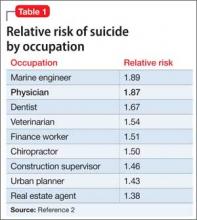

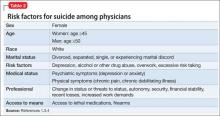

Physicians and other health professional have a higher relative risk of suicide (Table 1).2 Hospitalization should be considered and the decision based on the severity of the illness and the associated risk. Dr. D has several risk factors for suicide, including marital discord, pain, professional demands, and access to lethal means (Table 2).1,3,4

HISTORY Pain and disappointment

After medical school, Dr. D completed residency and joined a large clinic with outpatient and inpatient services. His supervisor was pleased with his work and encouraged him to take on more responsibility. However, within the first years of practice, his mood slowly deteriorated; he came to realize that he was deeply sad and, likely, clinically depressed.

Dr. D describes his parents as detached and emotionally unavailable to him. His mother’s depression sometimes was severe enough that she stayed in her bedroom, isolating herself from her son. Dr. D did not feel close to either of his parents; his mother continued to work despite the depression, which meant that both parents were away from home for long hours. Dr. D became interested in service to others and found that those he served responded to him in a positive way. Service to others became a way to feel recognized, appreciated, respected, and even loved.

Dr. D’s depressive symptoms became worse when he discovered his wife was having an affair. The depression became so debilitating that he requested, and was granted, an 8-week medical leave. Once away from the daily pressures of work, his depression improved somewhat, but conflict with his wife intensified and thoughts of suicide became more frequent. Soon afterward, Dr. D and his wife separated and he moved out. His supervisor recommended that Dr. D obtain treatment, but it was only after the separation that Dr. D decided to seek psychiatric care.

What type of psychotherapy is recommended for physicians with suicidal ideation?

a) psychodynamic psychotherapy

b) person-centered therapy

c) cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)

d) dialectical behavior therapy (DBT)

The authors’ observation

Reassure your physician−patients that it is safe and reasonable to take personal time off from work to recover from any illness, whether physical or mental. Consider the best treatment approaches to ensure patient’s safety, comfort, and rapid recovery. A critical part of treatment is exploring and identifying changes needed to achieve a life that is compatible with the ideal self, the patient’s view of himself, his beliefs, goals, and life’s meaning.

Physicians are at particular risk of losing the ideal self.5 Loss of the ideal self is common, and can be life threatening. Person-centered psychotherapy, CBT, supportive psychotherapy, DBT, and pharmacotherapy are used to lessen emotional distress and promote adaptive coping strategies, but approaches are different. Short-term counseling can reduce the effects of job stress,6 but a longer-term intervention likely is necessary for a mood disorder with thoughts of self-harm.

CBT emphasizes helping physicians recognize cognitive distortions and finding solutions. The behavioral aspects of CBT promote physical and mental relaxation, which is helpful in easing muscle tension, lowering heart rate, and decreasing the tendency to hyperventilate during stress.7 Mindfulness-based stress reduction programs can provide physical and mental benefits.8 DBT, a type of behavioral therapy, combines mindfulness, acceptance of the current state, skills to regulate emotion, and positive interpersonal relationship strategies.9

Pharmacotherapy should be focused on improving sleep, anxiety, appetite, and mood. Your patient may have other symptoms that need to be addressed: Ask what symptom bothers your patient the most, then work to provide solutions. Some interventions could promote adaptive coping strategies to identify ways to increase perceived control over the work day.10

TREATMENT Self-exploration

The treatment team instructs Dr. D to take a personal inventory of the elements of his ideal self, along the lines suggested in person-centered therapy.11,12 How did Dr. D envision his practice when he was in residency? What other domains of life were important to him? When Dr. D comes back with his list, the need for change is discussed and the process for incorporating these elements into his life begins. He begins to realize that returning to the elements of his ideal self brought opportunities, friendship, love, and faith back into his life.13,14

Maintaining balance between work responsibilities and pleasurable activities is part of achieving the ideal self. Recreation, social support, and exercise decrease the experience of stress and promote wellness.15,16

An important discussion centers on Dr. D’s risk of losing meaning in life after distancing himself from his original motivation to help people though practicing medicine. Dr. D understands that the distance between his expectations and dreams as a student and his current reality contributed to his depression.17 These conversations and changes in behavior brings Dr. D’s actual life closer to this ideal self, reducing self-discrepancy and lessening negative mood.18

The treating psychiatrist is aware of the reporting requirements to the state medical board, which are discussed with Dr. D. No report is deemed necessary.

The authors’ observation

Dr. D’s treatment course was challenging and required a multi-component approach. Establishing trust, while defining the limits of confidentiality, formed the foundation for the therapeutic relationship. The treatment provider asked for names of colleagues or friends to be contacted in case of an emergency. Dr. D chose his physician supervisor and agreed that the psychiatrist could contact the supervisor and vice versa.

Medication was prescribed at the end of the first session to begin to address anxiety and sleep problems. The initial medication was fluvoxamine, 50 mg/d, for anxiety and depression, clonazepam, 0.5 mg/d for anxiety, and zolpidem, 10 mg/d, for sleep. Adjustments were made in the dosage of antidepressant and responses monitored closely until the therapeutic dosage was reached with minimal side effects. Sleep improved, irritability lessened, and Dr. D’s obsessive, negative thinking and depression improved. Deeper, restorative sleep also began to reduce physical tension and pain. Improved sleep and decreased measures of depression are associated with significantly reduced risk of suicide.19

A treating psychiatrist should be aware of the state medical board requirements. In Ohio, where this case unfolded, reporting is required when the physician−patient is deemed unable to practice medicine according to acceptable and prevailing standards of care.20

Relieving tension and somatic complaints

An important part of the treatment plan consisted of managing chronic muscle tension and pain. We decided to front-load treatment, addressing the severe depression, anxiety, and pain simultaneously. Even moderate pain relief would give Dr. D a greater sense of control and improve his mood.

Dr. D understood that a return to normal biorhythms was necessary to form the foundation for the next step of therapy.21 The treatment team introduced mindful breathing, but Dr. D questioned how something so simple could lift severe depression. Focused, mindful breathing was not a cure, but a first step in regaining control over the current disarray of physical and emotional variations. We encouraged daily practice and he agreed to 5 practice sessions per week.

Next, the treatment team introduced progressive relaxation. Again, the simplicity of this process of tensing and relaxing groups of muscles was met with disbelief. Our therapist explained that voluntarily producing muscle tension facilitates the relaxation response of both the mind and the body. The mind first commands the muscles to do what it does easily— “tense”; then is asked to elicit what is more difficult—“relax.” Repetition of the simple commands “tense—relax” in the arms, legs, back, abdomen, shoulders, neck, and face establishes a calming rhythm, again increasing the sense of control.22 We strongly encouraged daily practice of this exercise and Dr. D committed to the mindful breathing and relaxation exercise.

OUTCOME Recovery, maintenance

Dr. D and his psychotherapist address his anger, all-or-nothing thinking, and loneliness. Grief over his failed marriage was identified, giving them an opportunity to explore this loss and past, perceived losses of his parents’ affection in the context of the therapeutic relationship. Supportive therapy promoted ways to fulfill his ideal self.

Treatment lasted 2 years. Dr. D’s prior depressive episode indicates a need for maintenance medication. The antidepressant is continued and, with help from supportive psychotherapy, stress management, 8 weeks away from work, and the life changes mentioned above, our patient has not had a relapse.

Bottom Line

Depression and thoughts of suicide are common among physicians. Grant time off from work and reassure the physician that he (she) is entitled to seek medical treatment without repercussions. Adapt the type of psychotherapy to the physician’s specific concerns. Because physicians are at particular risk for loss of the ideal self, first consider person-centered therapy.

Related Resources

• Vanderbilt Center for Professional Health. www.mc.vanderbilt.edu/cph.

• Federation of State Physician Health Programs, Inc. www.fsphp.org.

Drug Brand Names

Clonazepam • Klonopin Fluvoxamine • Luvox Zolpidem • Ambien

AcknowledgementThe authors wish to acknowledge the contribution of Rachel Sieke, BS, Research Assistant, Department of Psychiatry, University of Toledo Medical Center, Toledo, Ohio.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Bright RP, Krahn L. Depression and suicide among physicians. Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(4):16-17,25-26,30.

2. Burnett C, Maurer J, Dosemecl M. Mortality by occupation, industry, and cause of death: 24 reporting states (1984-1988). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www. cdc.gov/niosh/docs/97-114. Published June 1997. Accessed October 3, 2014.

3. Silverman MM. Physicians and suicide. In: Goldman LS, Myers M, Dickstein LJ, eds. The handbook of physician health: essential guide to understanding the health care needs of physicians. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2000:95-117.

4. Lindeman S, Laara E, Hakko H, et al. A systematic review on gender-specific suicide mortality in medical doctors. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;168(3):274-279.

5. Baumeister RF. Suicide as escape from self. Psychol Rev. 1990;97(1):90-113.

6. Rø KE, Gude T, Tyssen R, et al. Counselling for burnout in Norwegian doctors: one year cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a2004. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2004.

7. Broquet KE, Rockey PH. Teaching residents and program directors about physician impairment. Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28(3):221-225.

8. Irving JA, Dobkin PL, Park J. Cultivating mindfulness in health care professionals: a review of empirical studies of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2009;15(2):61-66.

9. Robins C, Schmidt H, Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy synthesizing radical acceptance with skillful means. In: Hayes S, Follette V, Linehan M, eds. Mindfulness and acceptance: expanding the cognitive-behavioral tradition. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2004:30-44.

10. Dunn PM, Arnetz BB, Christensen JF, et al. Meeting the imperative to improve physician well-being: assessment of an innovative program. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(11):1544-1552.

11. Nevid JS, Rathus SA, Greene B. Abnormal psychology in a changing world, 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice- Hall; 2008:111-112.

12. Rogers CR. Client-centered therapy. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin; 1951.

13. Selimbegovic´ L, Chatard A. The mirror effect: self-awareness alone increases suicide thought accessibility. Conscious Cogn. 2013;22(3):756-764.

14. Cornette M. Staff perspective: self-discrepancy and suicidal ideation. Center for Deployment Psychology. http:// www.deploymentpsych.org/blog/staff-perspective-self-discrepancy-and-suicidal-ideation. Published February 19, 2014. Accessed August 7, 2014.

15. Shanafelt TD, Novotny P, Johnson ME, et al. The well-being and personal wellness promotion strategies of medical oncologists in the North Central Cancer Treatment Group. Oncology. 2005;68(1):23-32.

16. Meldrum H. Exemplary physicians’ strategies for avoiding burnout. Health Care Manag (Frederick). 2010;29(4):324-331.

17. Orbach I, Mikulincer M, Stein D, et al. Self-representation of suicidal adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107(3):435-439.

18. Higgins ET. Self-discrepancy: a theory related self and affect. Psychol Rev. 1987;94(3):319-340.

19. Christensen H, Batterham PJ, Mackinnon AJ, et al. Predictors of the risk factors for suicide identified by the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behaviour. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219(2):290-297.

20. Ohio State Medical Board. Section 4731.22 (B), Rule 4731-18- 01. 2014.

21. McGrady A, Moss D. Pathways to illness, pathways to health. New York, NY: Springer; 2013.

22. Davis M, Eshelman ER, McKay M. The relaxation and stress reduction workbook, 6th ed. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, Inc; 2008.

CASE Feeling hopeless

Dr. D, age 33, a white, male physician, presents with worsening depression, suicidal ideation, and somatic complaints. Dr. D says his personal life has become increasingly unhappy. He describes the pressures of a busy practice and conflict with his wife about his availability to her. He is feeling financial pressure and general disappointment about practicing medicine. Lack of recreational activities and close friends and absent spiritual life has led to feelings of isolation and depression.

Dr. D reports difficulty falling asleep, waking up early, and feeling fatigued. He describes obsessive, negative thoughts about his work and his personal life; he is anxious and tense. Dissatisfied and exhausted, he says he feels hopeless and empty and has become preoccupied with thoughts of death.

Dr. D describes musculoskeletal tension in the neck, shoulders, and face, with pain in the back of the neck. When the depressive symptoms or pain are particularly severe, he admits that his attention to critical information lapses. When interacting with his patients, he has missed important nuances about medication side effects, for example, frustrating his patients and himself.

Dr. D and his wife do not have children. His mother and paternal grandfather had depression, but Dr. D has no family history of suicide or drug or alcohol abuse. He has no significant medical conditions, and is not taking any medications. Dr. D drinks 1 or 2 cups of caffeinated coffee a day. He does not smoke, use recreational drugs, or drink alcohol regularly.

What would be your next step in treating Dr. D?

a) alert the state medical board about his suicidal ideation

b) recommend inpatient treatment

c) refer Dr. D to a clinician who has experience treating physicians

d) formulate a suicide risk assessment

The authors’ observation

Assessment of the suicidal physician is complex. It requires patience and ability to understand the source and the extent of the physician’s desperation and suffering. Not all psychiatrists are well suited to working with patients who also are peers. An experienced clinician, who has confronted the challenges of practice and treated individuals from many professions, could be better equipped than a recent graduate. Physician− patients might not be forthcoming about the extent of their suicidal thinking, because they fear involuntary hospitalization and jeopardizing their career.1

The evaluating clinician must be thorough and clear, and able to facilitate a trusting relationship. The ill physician should be encouraged to express suicidal ideation freely—without judgments, restrictions, or threats—to a trusted psychiatrist. Questions should be clear without possibility of misinterpretation. Ask:

• “Do you have thoughts of death, dying, or wanting to be dead?”

• “Do you think about suicide?”

• “Do you feel you might act on those thoughts?”

• “What keeps you safe?”

Physicians and other health professional have a higher relative risk of suicide (Table 1).2 Hospitalization should be considered and the decision based on the severity of the illness and the associated risk. Dr. D has several risk factors for suicide, including marital discord, pain, professional demands, and access to lethal means (Table 2).1,3,4

HISTORY Pain and disappointment

After medical school, Dr. D completed residency and joined a large clinic with outpatient and inpatient services. His supervisor was pleased with his work and encouraged him to take on more responsibility. However, within the first years of practice, his mood slowly deteriorated; he came to realize that he was deeply sad and, likely, clinically depressed.

Dr. D describes his parents as detached and emotionally unavailable to him. His mother’s depression sometimes was severe enough that she stayed in her bedroom, isolating herself from her son. Dr. D did not feel close to either of his parents; his mother continued to work despite the depression, which meant that both parents were away from home for long hours. Dr. D became interested in service to others and found that those he served responded to him in a positive way. Service to others became a way to feel recognized, appreciated, respected, and even loved.

Dr. D’s depressive symptoms became worse when he discovered his wife was having an affair. The depression became so debilitating that he requested, and was granted, an 8-week medical leave. Once away from the daily pressures of work, his depression improved somewhat, but conflict with his wife intensified and thoughts of suicide became more frequent. Soon afterward, Dr. D and his wife separated and he moved out. His supervisor recommended that Dr. D obtain treatment, but it was only after the separation that Dr. D decided to seek psychiatric care.

What type of psychotherapy is recommended for physicians with suicidal ideation?

a) psychodynamic psychotherapy

b) person-centered therapy

c) cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)

d) dialectical behavior therapy (DBT)

The authors’ observation

Reassure your physician−patients that it is safe and reasonable to take personal time off from work to recover from any illness, whether physical or mental. Consider the best treatment approaches to ensure patient’s safety, comfort, and rapid recovery. A critical part of treatment is exploring and identifying changes needed to achieve a life that is compatible with the ideal self, the patient’s view of himself, his beliefs, goals, and life’s meaning.

Physicians are at particular risk of losing the ideal self.5 Loss of the ideal self is common, and can be life threatening. Person-centered psychotherapy, CBT, supportive psychotherapy, DBT, and pharmacotherapy are used to lessen emotional distress and promote adaptive coping strategies, but approaches are different. Short-term counseling can reduce the effects of job stress,6 but a longer-term intervention likely is necessary for a mood disorder with thoughts of self-harm.

CBT emphasizes helping physicians recognize cognitive distortions and finding solutions. The behavioral aspects of CBT promote physical and mental relaxation, which is helpful in easing muscle tension, lowering heart rate, and decreasing the tendency to hyperventilate during stress.7 Mindfulness-based stress reduction programs can provide physical and mental benefits.8 DBT, a type of behavioral therapy, combines mindfulness, acceptance of the current state, skills to regulate emotion, and positive interpersonal relationship strategies.9

Pharmacotherapy should be focused on improving sleep, anxiety, appetite, and mood. Your patient may have other symptoms that need to be addressed: Ask what symptom bothers your patient the most, then work to provide solutions. Some interventions could promote adaptive coping strategies to identify ways to increase perceived control over the work day.10

TREATMENT Self-exploration

The treatment team instructs Dr. D to take a personal inventory of the elements of his ideal self, along the lines suggested in person-centered therapy.11,12 How did Dr. D envision his practice when he was in residency? What other domains of life were important to him? When Dr. D comes back with his list, the need for change is discussed and the process for incorporating these elements into his life begins. He begins to realize that returning to the elements of his ideal self brought opportunities, friendship, love, and faith back into his life.13,14

Maintaining balance between work responsibilities and pleasurable activities is part of achieving the ideal self. Recreation, social support, and exercise decrease the experience of stress and promote wellness.15,16

An important discussion centers on Dr. D’s risk of losing meaning in life after distancing himself from his original motivation to help people though practicing medicine. Dr. D understands that the distance between his expectations and dreams as a student and his current reality contributed to his depression.17 These conversations and changes in behavior brings Dr. D’s actual life closer to this ideal self, reducing self-discrepancy and lessening negative mood.18

The treating psychiatrist is aware of the reporting requirements to the state medical board, which are discussed with Dr. D. No report is deemed necessary.

The authors’ observation

Dr. D’s treatment course was challenging and required a multi-component approach. Establishing trust, while defining the limits of confidentiality, formed the foundation for the therapeutic relationship. The treatment provider asked for names of colleagues or friends to be contacted in case of an emergency. Dr. D chose his physician supervisor and agreed that the psychiatrist could contact the supervisor and vice versa.

Medication was prescribed at the end of the first session to begin to address anxiety and sleep problems. The initial medication was fluvoxamine, 50 mg/d, for anxiety and depression, clonazepam, 0.5 mg/d for anxiety, and zolpidem, 10 mg/d, for sleep. Adjustments were made in the dosage of antidepressant and responses monitored closely until the therapeutic dosage was reached with minimal side effects. Sleep improved, irritability lessened, and Dr. D’s obsessive, negative thinking and depression improved. Deeper, restorative sleep also began to reduce physical tension and pain. Improved sleep and decreased measures of depression are associated with significantly reduced risk of suicide.19

A treating psychiatrist should be aware of the state medical board requirements. In Ohio, where this case unfolded, reporting is required when the physician−patient is deemed unable to practice medicine according to acceptable and prevailing standards of care.20

Relieving tension and somatic complaints

An important part of the treatment plan consisted of managing chronic muscle tension and pain. We decided to front-load treatment, addressing the severe depression, anxiety, and pain simultaneously. Even moderate pain relief would give Dr. D a greater sense of control and improve his mood.

Dr. D understood that a return to normal biorhythms was necessary to form the foundation for the next step of therapy.21 The treatment team introduced mindful breathing, but Dr. D questioned how something so simple could lift severe depression. Focused, mindful breathing was not a cure, but a first step in regaining control over the current disarray of physical and emotional variations. We encouraged daily practice and he agreed to 5 practice sessions per week.

Next, the treatment team introduced progressive relaxation. Again, the simplicity of this process of tensing and relaxing groups of muscles was met with disbelief. Our therapist explained that voluntarily producing muscle tension facilitates the relaxation response of both the mind and the body. The mind first commands the muscles to do what it does easily— “tense”; then is asked to elicit what is more difficult—“relax.” Repetition of the simple commands “tense—relax” in the arms, legs, back, abdomen, shoulders, neck, and face establishes a calming rhythm, again increasing the sense of control.22 We strongly encouraged daily practice of this exercise and Dr. D committed to the mindful breathing and relaxation exercise.

OUTCOME Recovery, maintenance

Dr. D and his psychotherapist address his anger, all-or-nothing thinking, and loneliness. Grief over his failed marriage was identified, giving them an opportunity to explore this loss and past, perceived losses of his parents’ affection in the context of the therapeutic relationship. Supportive therapy promoted ways to fulfill his ideal self.

Treatment lasted 2 years. Dr. D’s prior depressive episode indicates a need for maintenance medication. The antidepressant is continued and, with help from supportive psychotherapy, stress management, 8 weeks away from work, and the life changes mentioned above, our patient has not had a relapse.

Bottom Line

Depression and thoughts of suicide are common among physicians. Grant time off from work and reassure the physician that he (she) is entitled to seek medical treatment without repercussions. Adapt the type of psychotherapy to the physician’s specific concerns. Because physicians are at particular risk for loss of the ideal self, first consider person-centered therapy.

Related Resources

• Vanderbilt Center for Professional Health. www.mc.vanderbilt.edu/cph.

• Federation of State Physician Health Programs, Inc. www.fsphp.org.

Drug Brand Names

Clonazepam • Klonopin Fluvoxamine • Luvox Zolpidem • Ambien

AcknowledgementThe authors wish to acknowledge the contribution of Rachel Sieke, BS, Research Assistant, Department of Psychiatry, University of Toledo Medical Center, Toledo, Ohio.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE Feeling hopeless

Dr. D, age 33, a white, male physician, presents with worsening depression, suicidal ideation, and somatic complaints. Dr. D says his personal life has become increasingly unhappy. He describes the pressures of a busy practice and conflict with his wife about his availability to her. He is feeling financial pressure and general disappointment about practicing medicine. Lack of recreational activities and close friends and absent spiritual life has led to feelings of isolation and depression.

Dr. D reports difficulty falling asleep, waking up early, and feeling fatigued. He describes obsessive, negative thoughts about his work and his personal life; he is anxious and tense. Dissatisfied and exhausted, he says he feels hopeless and empty and has become preoccupied with thoughts of death.

Dr. D describes musculoskeletal tension in the neck, shoulders, and face, with pain in the back of the neck. When the depressive symptoms or pain are particularly severe, he admits that his attention to critical information lapses. When interacting with his patients, he has missed important nuances about medication side effects, for example, frustrating his patients and himself.

Dr. D and his wife do not have children. His mother and paternal grandfather had depression, but Dr. D has no family history of suicide or drug or alcohol abuse. He has no significant medical conditions, and is not taking any medications. Dr. D drinks 1 or 2 cups of caffeinated coffee a day. He does not smoke, use recreational drugs, or drink alcohol regularly.

What would be your next step in treating Dr. D?

a) alert the state medical board about his suicidal ideation

b) recommend inpatient treatment

c) refer Dr. D to a clinician who has experience treating physicians

d) formulate a suicide risk assessment

The authors’ observation

Assessment of the suicidal physician is complex. It requires patience and ability to understand the source and the extent of the physician’s desperation and suffering. Not all psychiatrists are well suited to working with patients who also are peers. An experienced clinician, who has confronted the challenges of practice and treated individuals from many professions, could be better equipped than a recent graduate. Physician− patients might not be forthcoming about the extent of their suicidal thinking, because they fear involuntary hospitalization and jeopardizing their career.1

The evaluating clinician must be thorough and clear, and able to facilitate a trusting relationship. The ill physician should be encouraged to express suicidal ideation freely—without judgments, restrictions, or threats—to a trusted psychiatrist. Questions should be clear without possibility of misinterpretation. Ask:

• “Do you have thoughts of death, dying, or wanting to be dead?”

• “Do you think about suicide?”

• “Do you feel you might act on those thoughts?”

• “What keeps you safe?”

Physicians and other health professional have a higher relative risk of suicide (Table 1).2 Hospitalization should be considered and the decision based on the severity of the illness and the associated risk. Dr. D has several risk factors for suicide, including marital discord, pain, professional demands, and access to lethal means (Table 2).1,3,4

HISTORY Pain and disappointment

After medical school, Dr. D completed residency and joined a large clinic with outpatient and inpatient services. His supervisor was pleased with his work and encouraged him to take on more responsibility. However, within the first years of practice, his mood slowly deteriorated; he came to realize that he was deeply sad and, likely, clinically depressed.

Dr. D describes his parents as detached and emotionally unavailable to him. His mother’s depression sometimes was severe enough that she stayed in her bedroom, isolating herself from her son. Dr. D did not feel close to either of his parents; his mother continued to work despite the depression, which meant that both parents were away from home for long hours. Dr. D became interested in service to others and found that those he served responded to him in a positive way. Service to others became a way to feel recognized, appreciated, respected, and even loved.

Dr. D’s depressive symptoms became worse when he discovered his wife was having an affair. The depression became so debilitating that he requested, and was granted, an 8-week medical leave. Once away from the daily pressures of work, his depression improved somewhat, but conflict with his wife intensified and thoughts of suicide became more frequent. Soon afterward, Dr. D and his wife separated and he moved out. His supervisor recommended that Dr. D obtain treatment, but it was only after the separation that Dr. D decided to seek psychiatric care.

What type of psychotherapy is recommended for physicians with suicidal ideation?

a) psychodynamic psychotherapy

b) person-centered therapy

c) cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)

d) dialectical behavior therapy (DBT)

The authors’ observation

Reassure your physician−patients that it is safe and reasonable to take personal time off from work to recover from any illness, whether physical or mental. Consider the best treatment approaches to ensure patient’s safety, comfort, and rapid recovery. A critical part of treatment is exploring and identifying changes needed to achieve a life that is compatible with the ideal self, the patient’s view of himself, his beliefs, goals, and life’s meaning.

Physicians are at particular risk of losing the ideal self.5 Loss of the ideal self is common, and can be life threatening. Person-centered psychotherapy, CBT, supportive psychotherapy, DBT, and pharmacotherapy are used to lessen emotional distress and promote adaptive coping strategies, but approaches are different. Short-term counseling can reduce the effects of job stress,6 but a longer-term intervention likely is necessary for a mood disorder with thoughts of self-harm.

CBT emphasizes helping physicians recognize cognitive distortions and finding solutions. The behavioral aspects of CBT promote physical and mental relaxation, which is helpful in easing muscle tension, lowering heart rate, and decreasing the tendency to hyperventilate during stress.7 Mindfulness-based stress reduction programs can provide physical and mental benefits.8 DBT, a type of behavioral therapy, combines mindfulness, acceptance of the current state, skills to regulate emotion, and positive interpersonal relationship strategies.9

Pharmacotherapy should be focused on improving sleep, anxiety, appetite, and mood. Your patient may have other symptoms that need to be addressed: Ask what symptom bothers your patient the most, then work to provide solutions. Some interventions could promote adaptive coping strategies to identify ways to increase perceived control over the work day.10

TREATMENT Self-exploration

The treatment team instructs Dr. D to take a personal inventory of the elements of his ideal self, along the lines suggested in person-centered therapy.11,12 How did Dr. D envision his practice when he was in residency? What other domains of life were important to him? When Dr. D comes back with his list, the need for change is discussed and the process for incorporating these elements into his life begins. He begins to realize that returning to the elements of his ideal self brought opportunities, friendship, love, and faith back into his life.13,14

Maintaining balance between work responsibilities and pleasurable activities is part of achieving the ideal self. Recreation, social support, and exercise decrease the experience of stress and promote wellness.15,16

An important discussion centers on Dr. D’s risk of losing meaning in life after distancing himself from his original motivation to help people though practicing medicine. Dr. D understands that the distance between his expectations and dreams as a student and his current reality contributed to his depression.17 These conversations and changes in behavior brings Dr. D’s actual life closer to this ideal self, reducing self-discrepancy and lessening negative mood.18

The treating psychiatrist is aware of the reporting requirements to the state medical board, which are discussed with Dr. D. No report is deemed necessary.

The authors’ observation

Dr. D’s treatment course was challenging and required a multi-component approach. Establishing trust, while defining the limits of confidentiality, formed the foundation for the therapeutic relationship. The treatment provider asked for names of colleagues or friends to be contacted in case of an emergency. Dr. D chose his physician supervisor and agreed that the psychiatrist could contact the supervisor and vice versa.

Medication was prescribed at the end of the first session to begin to address anxiety and sleep problems. The initial medication was fluvoxamine, 50 mg/d, for anxiety and depression, clonazepam, 0.5 mg/d for anxiety, and zolpidem, 10 mg/d, for sleep. Adjustments were made in the dosage of antidepressant and responses monitored closely until the therapeutic dosage was reached with minimal side effects. Sleep improved, irritability lessened, and Dr. D’s obsessive, negative thinking and depression improved. Deeper, restorative sleep also began to reduce physical tension and pain. Improved sleep and decreased measures of depression are associated with significantly reduced risk of suicide.19

A treating psychiatrist should be aware of the state medical board requirements. In Ohio, where this case unfolded, reporting is required when the physician−patient is deemed unable to practice medicine according to acceptable and prevailing standards of care.20

Relieving tension and somatic complaints

An important part of the treatment plan consisted of managing chronic muscle tension and pain. We decided to front-load treatment, addressing the severe depression, anxiety, and pain simultaneously. Even moderate pain relief would give Dr. D a greater sense of control and improve his mood.

Dr. D understood that a return to normal biorhythms was necessary to form the foundation for the next step of therapy.21 The treatment team introduced mindful breathing, but Dr. D questioned how something so simple could lift severe depression. Focused, mindful breathing was not a cure, but a first step in regaining control over the current disarray of physical and emotional variations. We encouraged daily practice and he agreed to 5 practice sessions per week.

Next, the treatment team introduced progressive relaxation. Again, the simplicity of this process of tensing and relaxing groups of muscles was met with disbelief. Our therapist explained that voluntarily producing muscle tension facilitates the relaxation response of both the mind and the body. The mind first commands the muscles to do what it does easily— “tense”; then is asked to elicit what is more difficult—“relax.” Repetition of the simple commands “tense—relax” in the arms, legs, back, abdomen, shoulders, neck, and face establishes a calming rhythm, again increasing the sense of control.22 We strongly encouraged daily practice of this exercise and Dr. D committed to the mindful breathing and relaxation exercise.

OUTCOME Recovery, maintenance

Dr. D and his psychotherapist address his anger, all-or-nothing thinking, and loneliness. Grief over his failed marriage was identified, giving them an opportunity to explore this loss and past, perceived losses of his parents’ affection in the context of the therapeutic relationship. Supportive therapy promoted ways to fulfill his ideal self.

Treatment lasted 2 years. Dr. D’s prior depressive episode indicates a need for maintenance medication. The antidepressant is continued and, with help from supportive psychotherapy, stress management, 8 weeks away from work, and the life changes mentioned above, our patient has not had a relapse.

Bottom Line

Depression and thoughts of suicide are common among physicians. Grant time off from work and reassure the physician that he (she) is entitled to seek medical treatment without repercussions. Adapt the type of psychotherapy to the physician’s specific concerns. Because physicians are at particular risk for loss of the ideal self, first consider person-centered therapy.

Related Resources

• Vanderbilt Center for Professional Health. www.mc.vanderbilt.edu/cph.

• Federation of State Physician Health Programs, Inc. www.fsphp.org.

Drug Brand Names

Clonazepam • Klonopin Fluvoxamine • Luvox Zolpidem • Ambien

AcknowledgementThe authors wish to acknowledge the contribution of Rachel Sieke, BS, Research Assistant, Department of Psychiatry, University of Toledo Medical Center, Toledo, Ohio.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Bright RP, Krahn L. Depression and suicide among physicians. Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(4):16-17,25-26,30.

2. Burnett C, Maurer J, Dosemecl M. Mortality by occupation, industry, and cause of death: 24 reporting states (1984-1988). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www. cdc.gov/niosh/docs/97-114. Published June 1997. Accessed October 3, 2014.

3. Silverman MM. Physicians and suicide. In: Goldman LS, Myers M, Dickstein LJ, eds. The handbook of physician health: essential guide to understanding the health care needs of physicians. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2000:95-117.

4. Lindeman S, Laara E, Hakko H, et al. A systematic review on gender-specific suicide mortality in medical doctors. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;168(3):274-279.

5. Baumeister RF. Suicide as escape from self. Psychol Rev. 1990;97(1):90-113.

6. Rø KE, Gude T, Tyssen R, et al. Counselling for burnout in Norwegian doctors: one year cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a2004. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2004.

7. Broquet KE, Rockey PH. Teaching residents and program directors about physician impairment. Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28(3):221-225.

8. Irving JA, Dobkin PL, Park J. Cultivating mindfulness in health care professionals: a review of empirical studies of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2009;15(2):61-66.

9. Robins C, Schmidt H, Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy synthesizing radical acceptance with skillful means. In: Hayes S, Follette V, Linehan M, eds. Mindfulness and acceptance: expanding the cognitive-behavioral tradition. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2004:30-44.

10. Dunn PM, Arnetz BB, Christensen JF, et al. Meeting the imperative to improve physician well-being: assessment of an innovative program. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(11):1544-1552.

11. Nevid JS, Rathus SA, Greene B. Abnormal psychology in a changing world, 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice- Hall; 2008:111-112.

12. Rogers CR. Client-centered therapy. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin; 1951.

13. Selimbegovic´ L, Chatard A. The mirror effect: self-awareness alone increases suicide thought accessibility. Conscious Cogn. 2013;22(3):756-764.

14. Cornette M. Staff perspective: self-discrepancy and suicidal ideation. Center for Deployment Psychology. http:// www.deploymentpsych.org/blog/staff-perspective-self-discrepancy-and-suicidal-ideation. Published February 19, 2014. Accessed August 7, 2014.

15. Shanafelt TD, Novotny P, Johnson ME, et al. The well-being and personal wellness promotion strategies of medical oncologists in the North Central Cancer Treatment Group. Oncology. 2005;68(1):23-32.

16. Meldrum H. Exemplary physicians’ strategies for avoiding burnout. Health Care Manag (Frederick). 2010;29(4):324-331.

17. Orbach I, Mikulincer M, Stein D, et al. Self-representation of suicidal adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107(3):435-439.

18. Higgins ET. Self-discrepancy: a theory related self and affect. Psychol Rev. 1987;94(3):319-340.

19. Christensen H, Batterham PJ, Mackinnon AJ, et al. Predictors of the risk factors for suicide identified by the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behaviour. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219(2):290-297.

20. Ohio State Medical Board. Section 4731.22 (B), Rule 4731-18- 01. 2014.

21. McGrady A, Moss D. Pathways to illness, pathways to health. New York, NY: Springer; 2013.

22. Davis M, Eshelman ER, McKay M. The relaxation and stress reduction workbook, 6th ed. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, Inc; 2008.

1. Bright RP, Krahn L. Depression and suicide among physicians. Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(4):16-17,25-26,30.

2. Burnett C, Maurer J, Dosemecl M. Mortality by occupation, industry, and cause of death: 24 reporting states (1984-1988). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www. cdc.gov/niosh/docs/97-114. Published June 1997. Accessed October 3, 2014.

3. Silverman MM. Physicians and suicide. In: Goldman LS, Myers M, Dickstein LJ, eds. The handbook of physician health: essential guide to understanding the health care needs of physicians. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2000:95-117.

4. Lindeman S, Laara E, Hakko H, et al. A systematic review on gender-specific suicide mortality in medical doctors. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;168(3):274-279.

5. Baumeister RF. Suicide as escape from self. Psychol Rev. 1990;97(1):90-113.

6. Rø KE, Gude T, Tyssen R, et al. Counselling for burnout in Norwegian doctors: one year cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a2004. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2004.

7. Broquet KE, Rockey PH. Teaching residents and program directors about physician impairment. Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28(3):221-225.

8. Irving JA, Dobkin PL, Park J. Cultivating mindfulness in health care professionals: a review of empirical studies of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2009;15(2):61-66.

9. Robins C, Schmidt H, Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy synthesizing radical acceptance with skillful means. In: Hayes S, Follette V, Linehan M, eds. Mindfulness and acceptance: expanding the cognitive-behavioral tradition. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2004:30-44.

10. Dunn PM, Arnetz BB, Christensen JF, et al. Meeting the imperative to improve physician well-being: assessment of an innovative program. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(11):1544-1552.

11. Nevid JS, Rathus SA, Greene B. Abnormal psychology in a changing world, 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice- Hall; 2008:111-112.

12. Rogers CR. Client-centered therapy. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin; 1951.

13. Selimbegovic´ L, Chatard A. The mirror effect: self-awareness alone increases suicide thought accessibility. Conscious Cogn. 2013;22(3):756-764.

14. Cornette M. Staff perspective: self-discrepancy and suicidal ideation. Center for Deployment Psychology. http:// www.deploymentpsych.org/blog/staff-perspective-self-discrepancy-and-suicidal-ideation. Published February 19, 2014. Accessed August 7, 2014.

15. Shanafelt TD, Novotny P, Johnson ME, et al. The well-being and personal wellness promotion strategies of medical oncologists in the North Central Cancer Treatment Group. Oncology. 2005;68(1):23-32.

16. Meldrum H. Exemplary physicians’ strategies for avoiding burnout. Health Care Manag (Frederick). 2010;29(4):324-331.

17. Orbach I, Mikulincer M, Stein D, et al. Self-representation of suicidal adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107(3):435-439.

18. Higgins ET. Self-discrepancy: a theory related self and affect. Psychol Rev. 1987;94(3):319-340.

19. Christensen H, Batterham PJ, Mackinnon AJ, et al. Predictors of the risk factors for suicide identified by the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behaviour. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219(2):290-297.

20. Ohio State Medical Board. Section 4731.22 (B), Rule 4731-18- 01. 2014.

21. McGrady A, Moss D. Pathways to illness, pathways to health. New York, NY: Springer; 2013.

22. Davis M, Eshelman ER, McKay M. The relaxation and stress reduction workbook, 6th ed. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, Inc; 2008.