User login

AGA Clinical Practice Update: Opioids in gastroenterology

Physicians should consistently rule out opioid therapy as the cause of gastrointestinal symptoms, states a new clinical practice update published in the September 2017 issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.05.014).

About 4% of Americans receive long-term opioid therapy, primarily for musculoskeletal, postsurgical, or vascular pain, as well as nonsurgical abdominal pain, writes Michael Camilleri, MD, AGAF, of Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and his associates. Because opioid receptors thickly populate the gastrointestinal tract, exogenous opioids can trigger a variety of gastrointestinal symptoms. Examples include achalasia, gastroparesis, nausea, postsurgical ileus, constipation, and narcotic bowel syndrome.

In the stomach, opioid use can cause gastroparesis, early satiety, and postprandial nausea and emesis, especially in the postoperative setting. Even novel opioid agents that are less likely to cause constipation can retard gastric emptying. For example, tapentadol, a mu-opioid agonist and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, delays emptying to the same extent as oxycodone. Tramadol also appears to slow overall orocecal transit. Although gastroparesis itself can cause nausea and emesis, opioids also directly stimulate the chemoreceptor trigger zone in the area postrema in the floor of the fourth ventricle. Options for preventive therapy include using a prokinetic, such as metoclopramide, prochlorperazine, or a 5-hydroxytryptamine3 antagonist, especially if patients are receiving opioids for postoperative pain control.

Exogenous opioids also can cause ileus, especially after abdominal surgery. These patients are already at risk of ileus because of surgical stress from bowel handling, secretion of inflammatory mediators and endogenous opioids, and fluctuating hormone and electrolyte levels. Postoperative analgesia with mu-opioids adds to the risk of ileus by increasing fluid absorption and inhibiting colonic motility.

Both postsurgical and nonsurgical opioid use also can trigger opioid-induced constipation (OIC), in which patients have less than three spontaneous bowel movements a week, harder stools, increased straining, and a feeling of incomplete evacuation. Patients may also report nausea, emesis, and gastroesophageal reflux. Even low-dose and short-term opioid therapy can lead to OIC. Symptoms and treatment response can be assessed with the bowel function index, in which patients rate ease of defecation, completeness of bowel evacuation, and severity of constipation over the past week on a scale of 0-100. Scores of 0-29 suggest no OIC. Patients who score above 30 despite over-the-counter laxatives are candidates for stepped-up treatments, including prolonged-release naloxone and oxycodone, the intestinal secretagogue lubiprostone, or peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonists (PAMORAs), such as methylnaltrexone (12 mg subcutaneously) and naloxegol (12.5 mg or 25 mg per day orally). Additionally, tapentadol controls pain at lower doses than oxycodone and is less likely to cause constipation.

Narcotic bowel syndrome typically presents as moderate to severe daily abdominal pain lasting more than 3 months in patients on long-term opioids equating to a dosage of more than 100 mg morphine daily. Typically, patients report generalized, persistent, colicky abdominal pain that does not respond to dose escalation and worsens with dose tapering. Work-up is negative for differentials such as kidney stones or bowel obstruction. One epidemiological study estimated that 4% of patients on long-term opiates develop narcotic bowel syndrome, but the true prevalence may be higher according to the experts who authored this update. Mechanisms remain unclear but may include neuroplastic changes that favor the facilitation of pain signals rather than their inhibition, inflammation of spinal glial cells through activation of toll-like receptors, abnormal function of the N-methyl-D aspartate receptor at the level of the spinal cord, and central nociceptive abnormalities related to certain psychological traits or a history of trauma.

Treating narcotic bowel syndrome requires detoxification with appropriate nonopioid therapies for pain, anxiety, and withdrawal symptoms, including the use of clonidine. “This is best handled through specialists or centers with expertise in opiate dependence,” the experts stated. Patients who are able to stay off narcotics report improvements in pain, but the recidivism rate is about 50%.

The practice update also covers opioid therapy for gastrointestinal disorders. The PAMORA alvimopan shortens time to first postoperative stool without counteracting opioid analgesia during recovery. Alvimopan also has been found to hasten recovery of gastrointestinal function in patients with postoperative ileus after bowel resection. There is no evidence for using mu-opioid agonists for pain associated with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), but the synthetic peripheral mu-opioid receptor agonist loperamide can improve stool consistency and urgency. A typical dose is 2 mg after each loose bowel movement or 2-4 mg before eating in cases of postprandial diarrhea. The mixed mu- and kappa-opioid receptor agonist and delta-opioid receptor antagonist eluxadoline also can potentially improve stool consistency and urgency, global IBS symptoms, IBS symptom severity score, and quality of life. However, the FDA warns against using eluxadoline in patients who do not have a gallbladder because of the risk of severe outcomes – including death – related to sphincter of Oddi spasm and pancreatitis. Eluxadoline has been linked to at least two such fatalities in cholecystectomized patients. In each case, symptoms began after a single dose.

Dr. Camilleri is funded by the National Institutes of Health. He disclosed ties to AstraZeneca and Shionogi. The two coauthors disclosed ties to Forest Research Labs, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Prometheus, and Salix.

Physicians should consistently rule out opioid therapy as the cause of gastrointestinal symptoms, states a new clinical practice update published in the September 2017 issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.05.014).

About 4% of Americans receive long-term opioid therapy, primarily for musculoskeletal, postsurgical, or vascular pain, as well as nonsurgical abdominal pain, writes Michael Camilleri, MD, AGAF, of Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and his associates. Because opioid receptors thickly populate the gastrointestinal tract, exogenous opioids can trigger a variety of gastrointestinal symptoms. Examples include achalasia, gastroparesis, nausea, postsurgical ileus, constipation, and narcotic bowel syndrome.

In the stomach, opioid use can cause gastroparesis, early satiety, and postprandial nausea and emesis, especially in the postoperative setting. Even novel opioid agents that are less likely to cause constipation can retard gastric emptying. For example, tapentadol, a mu-opioid agonist and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, delays emptying to the same extent as oxycodone. Tramadol also appears to slow overall orocecal transit. Although gastroparesis itself can cause nausea and emesis, opioids also directly stimulate the chemoreceptor trigger zone in the area postrema in the floor of the fourth ventricle. Options for preventive therapy include using a prokinetic, such as metoclopramide, prochlorperazine, or a 5-hydroxytryptamine3 antagonist, especially if patients are receiving opioids for postoperative pain control.

Exogenous opioids also can cause ileus, especially after abdominal surgery. These patients are already at risk of ileus because of surgical stress from bowel handling, secretion of inflammatory mediators and endogenous opioids, and fluctuating hormone and electrolyte levels. Postoperative analgesia with mu-opioids adds to the risk of ileus by increasing fluid absorption and inhibiting colonic motility.

Both postsurgical and nonsurgical opioid use also can trigger opioid-induced constipation (OIC), in which patients have less than three spontaneous bowel movements a week, harder stools, increased straining, and a feeling of incomplete evacuation. Patients may also report nausea, emesis, and gastroesophageal reflux. Even low-dose and short-term opioid therapy can lead to OIC. Symptoms and treatment response can be assessed with the bowel function index, in which patients rate ease of defecation, completeness of bowel evacuation, and severity of constipation over the past week on a scale of 0-100. Scores of 0-29 suggest no OIC. Patients who score above 30 despite over-the-counter laxatives are candidates for stepped-up treatments, including prolonged-release naloxone and oxycodone, the intestinal secretagogue lubiprostone, or peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonists (PAMORAs), such as methylnaltrexone (12 mg subcutaneously) and naloxegol (12.5 mg or 25 mg per day orally). Additionally, tapentadol controls pain at lower doses than oxycodone and is less likely to cause constipation.

Narcotic bowel syndrome typically presents as moderate to severe daily abdominal pain lasting more than 3 months in patients on long-term opioids equating to a dosage of more than 100 mg morphine daily. Typically, patients report generalized, persistent, colicky abdominal pain that does not respond to dose escalation and worsens with dose tapering. Work-up is negative for differentials such as kidney stones or bowel obstruction. One epidemiological study estimated that 4% of patients on long-term opiates develop narcotic bowel syndrome, but the true prevalence may be higher according to the experts who authored this update. Mechanisms remain unclear but may include neuroplastic changes that favor the facilitation of pain signals rather than their inhibition, inflammation of spinal glial cells through activation of toll-like receptors, abnormal function of the N-methyl-D aspartate receptor at the level of the spinal cord, and central nociceptive abnormalities related to certain psychological traits or a history of trauma.

Treating narcotic bowel syndrome requires detoxification with appropriate nonopioid therapies for pain, anxiety, and withdrawal symptoms, including the use of clonidine. “This is best handled through specialists or centers with expertise in opiate dependence,” the experts stated. Patients who are able to stay off narcotics report improvements in pain, but the recidivism rate is about 50%.

The practice update also covers opioid therapy for gastrointestinal disorders. The PAMORA alvimopan shortens time to first postoperative stool without counteracting opioid analgesia during recovery. Alvimopan also has been found to hasten recovery of gastrointestinal function in patients with postoperative ileus after bowel resection. There is no evidence for using mu-opioid agonists for pain associated with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), but the synthetic peripheral mu-opioid receptor agonist loperamide can improve stool consistency and urgency. A typical dose is 2 mg after each loose bowel movement or 2-4 mg before eating in cases of postprandial diarrhea. The mixed mu- and kappa-opioid receptor agonist and delta-opioid receptor antagonist eluxadoline also can potentially improve stool consistency and urgency, global IBS symptoms, IBS symptom severity score, and quality of life. However, the FDA warns against using eluxadoline in patients who do not have a gallbladder because of the risk of severe outcomes – including death – related to sphincter of Oddi spasm and pancreatitis. Eluxadoline has been linked to at least two such fatalities in cholecystectomized patients. In each case, symptoms began after a single dose.

Dr. Camilleri is funded by the National Institutes of Health. He disclosed ties to AstraZeneca and Shionogi. The two coauthors disclosed ties to Forest Research Labs, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Prometheus, and Salix.

Physicians should consistently rule out opioid therapy as the cause of gastrointestinal symptoms, states a new clinical practice update published in the September 2017 issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.05.014).

About 4% of Americans receive long-term opioid therapy, primarily for musculoskeletal, postsurgical, or vascular pain, as well as nonsurgical abdominal pain, writes Michael Camilleri, MD, AGAF, of Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and his associates. Because opioid receptors thickly populate the gastrointestinal tract, exogenous opioids can trigger a variety of gastrointestinal symptoms. Examples include achalasia, gastroparesis, nausea, postsurgical ileus, constipation, and narcotic bowel syndrome.

In the stomach, opioid use can cause gastroparesis, early satiety, and postprandial nausea and emesis, especially in the postoperative setting. Even novel opioid agents that are less likely to cause constipation can retard gastric emptying. For example, tapentadol, a mu-opioid agonist and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, delays emptying to the same extent as oxycodone. Tramadol also appears to slow overall orocecal transit. Although gastroparesis itself can cause nausea and emesis, opioids also directly stimulate the chemoreceptor trigger zone in the area postrema in the floor of the fourth ventricle. Options for preventive therapy include using a prokinetic, such as metoclopramide, prochlorperazine, or a 5-hydroxytryptamine3 antagonist, especially if patients are receiving opioids for postoperative pain control.

Exogenous opioids also can cause ileus, especially after abdominal surgery. These patients are already at risk of ileus because of surgical stress from bowel handling, secretion of inflammatory mediators and endogenous opioids, and fluctuating hormone and electrolyte levels. Postoperative analgesia with mu-opioids adds to the risk of ileus by increasing fluid absorption and inhibiting colonic motility.

Both postsurgical and nonsurgical opioid use also can trigger opioid-induced constipation (OIC), in which patients have less than three spontaneous bowel movements a week, harder stools, increased straining, and a feeling of incomplete evacuation. Patients may also report nausea, emesis, and gastroesophageal reflux. Even low-dose and short-term opioid therapy can lead to OIC. Symptoms and treatment response can be assessed with the bowel function index, in which patients rate ease of defecation, completeness of bowel evacuation, and severity of constipation over the past week on a scale of 0-100. Scores of 0-29 suggest no OIC. Patients who score above 30 despite over-the-counter laxatives are candidates for stepped-up treatments, including prolonged-release naloxone and oxycodone, the intestinal secretagogue lubiprostone, or peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonists (PAMORAs), such as methylnaltrexone (12 mg subcutaneously) and naloxegol (12.5 mg or 25 mg per day orally). Additionally, tapentadol controls pain at lower doses than oxycodone and is less likely to cause constipation.

Narcotic bowel syndrome typically presents as moderate to severe daily abdominal pain lasting more than 3 months in patients on long-term opioids equating to a dosage of more than 100 mg morphine daily. Typically, patients report generalized, persistent, colicky abdominal pain that does not respond to dose escalation and worsens with dose tapering. Work-up is negative for differentials such as kidney stones or bowel obstruction. One epidemiological study estimated that 4% of patients on long-term opiates develop narcotic bowel syndrome, but the true prevalence may be higher according to the experts who authored this update. Mechanisms remain unclear but may include neuroplastic changes that favor the facilitation of pain signals rather than their inhibition, inflammation of spinal glial cells through activation of toll-like receptors, abnormal function of the N-methyl-D aspartate receptor at the level of the spinal cord, and central nociceptive abnormalities related to certain psychological traits or a history of trauma.

Treating narcotic bowel syndrome requires detoxification with appropriate nonopioid therapies for pain, anxiety, and withdrawal symptoms, including the use of clonidine. “This is best handled through specialists or centers with expertise in opiate dependence,” the experts stated. Patients who are able to stay off narcotics report improvements in pain, but the recidivism rate is about 50%.

The practice update also covers opioid therapy for gastrointestinal disorders. The PAMORA alvimopan shortens time to first postoperative stool without counteracting opioid analgesia during recovery. Alvimopan also has been found to hasten recovery of gastrointestinal function in patients with postoperative ileus after bowel resection. There is no evidence for using mu-opioid agonists for pain associated with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), but the synthetic peripheral mu-opioid receptor agonist loperamide can improve stool consistency and urgency. A typical dose is 2 mg after each loose bowel movement or 2-4 mg before eating in cases of postprandial diarrhea. The mixed mu- and kappa-opioid receptor agonist and delta-opioid receptor antagonist eluxadoline also can potentially improve stool consistency and urgency, global IBS symptoms, IBS symptom severity score, and quality of life. However, the FDA warns against using eluxadoline in patients who do not have a gallbladder because of the risk of severe outcomes – including death – related to sphincter of Oddi spasm and pancreatitis. Eluxadoline has been linked to at least two such fatalities in cholecystectomized patients. In each case, symptoms began after a single dose.

Dr. Camilleri is funded by the National Institutes of Health. He disclosed ties to AstraZeneca and Shionogi. The two coauthors disclosed ties to Forest Research Labs, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Prometheus, and Salix.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Colonic microbiota encroachment linked to diabetes

Bacterial infiltration into the colonic mucosa was associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus in humans, confirming prior findings in mice, investigators said.

Unlike in mice, however, microbiota encroachment did not correlate with human adiposity per se, reported Benoit Chassaing, PhD, of Georgia State University, Atlanta, and his associates. Their mouse models all have involved low-grade inflammation, which might impair insulin/leptin signaling and thereby promote both adiposity and dysglycemia, they said. In contrast, “we presume that humans can become obese for other reasons not involving the microbiota,” they added. The findings were published in the September issue of Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2017;2[4]:205-21. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.04.001).

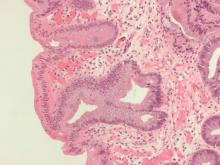

For the study, the investigators analyzed colonic mucosal biopsies from 42 middle-aged diabetic adults who underwent screening colonoscopies at a single Veteran’s Affairs hospital. All but one of the patients were men, 86% were overweight, 45% were obese, and 33% (14 patients) had diabetes. The researchers measured the shortest distance between bacteria and the epithelium using confocal microscopy and fluorescent in situ hybridization.

Nonobese, nondiabetic patients had residual bacteria “almost exclusively” in outer regions of the mucus layer, while obese diabetic patients had bacteria in the dense inner mucus near the epithelium, said the investigators. Unlike in mice, bacterial-epithelial distances did not correlate with adiposity per se among individuals without diabetes (P = .4). Conversely, patients with diabetes had bacterial-epithelial distances that were about one-third of those in euglycemic individuals (P less than .0001), even when they were not obese (P less than .001).

“We conclude that microbiota encroachment is a feature of insulin resistance–associated dysglycemia in humans,” Dr. Chassaing and his associates wrote. Microbiota encroachment did not correlate with ethnicity, use of antibiotics or diabetes treatments, or low-density lipoprotein levels, but it did correlate with a rise in CD19+ cells, probably mucosal B cells, they said. Defining connections among microbiota encroachment, B-cell responses, and metabolic disease might clarify the pathophysiology and treatment of metabolic syndrome, they concluded.

The investigators also induced hyperglycemia in wild-type mice by giving them water with 10% sucrose and intraperitoneal streptozotocin injections. Ten days after the last injection, they measured fasting blood glucose, fecal glucose, and colonic bacterial-epithelial distances. Even though fecal glucose rose as expected, they found no evidence of microbiota encroachment. They concluded that short-term (2-week) hyperglycemia was not enough to cause encroachment. Thus, microbiota encroachment is a characteristic of type 2 diabetes, not of adiposity per se, correlates with disease severity, and might stem from chronic inflammatory processes that drive insulin resistance, they concluded.

Funders included the National Institutes of Health, VA-MERIT, and the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America. The investigators had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Dr. Chassaing and his colleagues examined the possible importance of the bacteria-free layer adjacent to the colonic epithelium in metabolic syndrome. A shrinking of this layer, termed “bacterial encroachment,” has been associated with human inflammatory bowel disease as well as mouse models of both colitis and metabolic syndrome, but the current study represents its first clear demonstration in human diabetes. In a cohort of 42 patients, the authors found that the epithelial-bacterial distance was inversely correlated with body mass index, fasting glucose, and hemoglobin A1c levels.

Interestingly, the primary predictor of encroachment in these patients was dysglycemia, not body mass index. This could not have been tested in standard mouse models where, because of the nature of the experimental insult, obesity and dysglycemia are essentially linked. Comparing obese human patients with and without dysglycemia, on the other hand, showed that encroachment is only clearly correlated with failed glucose regulation. This, however, is not the end of the story: In coordinated experiments with a short-term murine dysglycemia model, high glucose levels were not sufficient to elicit encroachment, suggesting a more complex metabolic circuit as the driver.

Mark R. Frey, PhD, is associate professor of pediatrics and biochemistry and molecular medicine at the Saban Research Institute, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, University of Southern California.

Dr. Chassaing and his colleagues examined the possible importance of the bacteria-free layer adjacent to the colonic epithelium in metabolic syndrome. A shrinking of this layer, termed “bacterial encroachment,” has been associated with human inflammatory bowel disease as well as mouse models of both colitis and metabolic syndrome, but the current study represents its first clear demonstration in human diabetes. In a cohort of 42 patients, the authors found that the epithelial-bacterial distance was inversely correlated with body mass index, fasting glucose, and hemoglobin A1c levels.

Interestingly, the primary predictor of encroachment in these patients was dysglycemia, not body mass index. This could not have been tested in standard mouse models where, because of the nature of the experimental insult, obesity and dysglycemia are essentially linked. Comparing obese human patients with and without dysglycemia, on the other hand, showed that encroachment is only clearly correlated with failed glucose regulation. This, however, is not the end of the story: In coordinated experiments with a short-term murine dysglycemia model, high glucose levels were not sufficient to elicit encroachment, suggesting a more complex metabolic circuit as the driver.

Mark R. Frey, PhD, is associate professor of pediatrics and biochemistry and molecular medicine at the Saban Research Institute, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, University of Southern California.

Dr. Chassaing and his colleagues examined the possible importance of the bacteria-free layer adjacent to the colonic epithelium in metabolic syndrome. A shrinking of this layer, termed “bacterial encroachment,” has been associated with human inflammatory bowel disease as well as mouse models of both colitis and metabolic syndrome, but the current study represents its first clear demonstration in human diabetes. In a cohort of 42 patients, the authors found that the epithelial-bacterial distance was inversely correlated with body mass index, fasting glucose, and hemoglobin A1c levels.

Interestingly, the primary predictor of encroachment in these patients was dysglycemia, not body mass index. This could not have been tested in standard mouse models where, because of the nature of the experimental insult, obesity and dysglycemia are essentially linked. Comparing obese human patients with and without dysglycemia, on the other hand, showed that encroachment is only clearly correlated with failed glucose regulation. This, however, is not the end of the story: In coordinated experiments with a short-term murine dysglycemia model, high glucose levels were not sufficient to elicit encroachment, suggesting a more complex metabolic circuit as the driver.

Mark R. Frey, PhD, is associate professor of pediatrics and biochemistry and molecular medicine at the Saban Research Institute, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, University of Southern California.

Bacterial infiltration into the colonic mucosa was associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus in humans, confirming prior findings in mice, investigators said.

Unlike in mice, however, microbiota encroachment did not correlate with human adiposity per se, reported Benoit Chassaing, PhD, of Georgia State University, Atlanta, and his associates. Their mouse models all have involved low-grade inflammation, which might impair insulin/leptin signaling and thereby promote both adiposity and dysglycemia, they said. In contrast, “we presume that humans can become obese for other reasons not involving the microbiota,” they added. The findings were published in the September issue of Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2017;2[4]:205-21. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.04.001).

For the study, the investigators analyzed colonic mucosal biopsies from 42 middle-aged diabetic adults who underwent screening colonoscopies at a single Veteran’s Affairs hospital. All but one of the patients were men, 86% were overweight, 45% were obese, and 33% (14 patients) had diabetes. The researchers measured the shortest distance between bacteria and the epithelium using confocal microscopy and fluorescent in situ hybridization.

Nonobese, nondiabetic patients had residual bacteria “almost exclusively” in outer regions of the mucus layer, while obese diabetic patients had bacteria in the dense inner mucus near the epithelium, said the investigators. Unlike in mice, bacterial-epithelial distances did not correlate with adiposity per se among individuals without diabetes (P = .4). Conversely, patients with diabetes had bacterial-epithelial distances that were about one-third of those in euglycemic individuals (P less than .0001), even when they were not obese (P less than .001).

“We conclude that microbiota encroachment is a feature of insulin resistance–associated dysglycemia in humans,” Dr. Chassaing and his associates wrote. Microbiota encroachment did not correlate with ethnicity, use of antibiotics or diabetes treatments, or low-density lipoprotein levels, but it did correlate with a rise in CD19+ cells, probably mucosal B cells, they said. Defining connections among microbiota encroachment, B-cell responses, and metabolic disease might clarify the pathophysiology and treatment of metabolic syndrome, they concluded.

The investigators also induced hyperglycemia in wild-type mice by giving them water with 10% sucrose and intraperitoneal streptozotocin injections. Ten days after the last injection, they measured fasting blood glucose, fecal glucose, and colonic bacterial-epithelial distances. Even though fecal glucose rose as expected, they found no evidence of microbiota encroachment. They concluded that short-term (2-week) hyperglycemia was not enough to cause encroachment. Thus, microbiota encroachment is a characteristic of type 2 diabetes, not of adiposity per se, correlates with disease severity, and might stem from chronic inflammatory processes that drive insulin resistance, they concluded.

Funders included the National Institutes of Health, VA-MERIT, and the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America. The investigators had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Bacterial infiltration into the colonic mucosa was associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus in humans, confirming prior findings in mice, investigators said.

Unlike in mice, however, microbiota encroachment did not correlate with human adiposity per se, reported Benoit Chassaing, PhD, of Georgia State University, Atlanta, and his associates. Their mouse models all have involved low-grade inflammation, which might impair insulin/leptin signaling and thereby promote both adiposity and dysglycemia, they said. In contrast, “we presume that humans can become obese for other reasons not involving the microbiota,” they added. The findings were published in the September issue of Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2017;2[4]:205-21. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.04.001).

For the study, the investigators analyzed colonic mucosal biopsies from 42 middle-aged diabetic adults who underwent screening colonoscopies at a single Veteran’s Affairs hospital. All but one of the patients were men, 86% were overweight, 45% were obese, and 33% (14 patients) had diabetes. The researchers measured the shortest distance between bacteria and the epithelium using confocal microscopy and fluorescent in situ hybridization.

Nonobese, nondiabetic patients had residual bacteria “almost exclusively” in outer regions of the mucus layer, while obese diabetic patients had bacteria in the dense inner mucus near the epithelium, said the investigators. Unlike in mice, bacterial-epithelial distances did not correlate with adiposity per se among individuals without diabetes (P = .4). Conversely, patients with diabetes had bacterial-epithelial distances that were about one-third of those in euglycemic individuals (P less than .0001), even when they were not obese (P less than .001).

“We conclude that microbiota encroachment is a feature of insulin resistance–associated dysglycemia in humans,” Dr. Chassaing and his associates wrote. Microbiota encroachment did not correlate with ethnicity, use of antibiotics or diabetes treatments, or low-density lipoprotein levels, but it did correlate with a rise in CD19+ cells, probably mucosal B cells, they said. Defining connections among microbiota encroachment, B-cell responses, and metabolic disease might clarify the pathophysiology and treatment of metabolic syndrome, they concluded.

The investigators also induced hyperglycemia in wild-type mice by giving them water with 10% sucrose and intraperitoneal streptozotocin injections. Ten days after the last injection, they measured fasting blood glucose, fecal glucose, and colonic bacterial-epithelial distances. Even though fecal glucose rose as expected, they found no evidence of microbiota encroachment. They concluded that short-term (2-week) hyperglycemia was not enough to cause encroachment. Thus, microbiota encroachment is a characteristic of type 2 diabetes, not of adiposity per se, correlates with disease severity, and might stem from chronic inflammatory processes that drive insulin resistance, they concluded.

Funders included the National Institutes of Health, VA-MERIT, and the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America. The investigators had no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM CELLULAR AND MOLECULAR GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Microbiota encroachment into colonic mucosa characterizes type 2 diabetes in humans.

Major finding: Regardless of whether they were obese or normal weight, patients with diabetes had bacterial-epithelial colonic distances that were one-third of those in euglycemic individuals (P less than .001).

Data source: A study of 42 Veterans Affairs patients with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Disclosures: Funders included the National Institutes of Health, VA-MERIT, and the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America. The investigators had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Small study advances noninvasive ICP monitoring

A device that noninvasively measures intracranial pressure (ICP) had a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 89%, compared with standard invasive monitoring, based on the results of an industry-sponsored study of 14 patients with traumatic brain injury or subarachnoid hemorrhage.

“This study provides the first clinical data on the accuracy of the HS-1000 noninvasive ICP monitor, which uses advanced signal analysis algorithms to evaluate properties of acoustic signals traveling through the brain,” wrote Oliver Ganslandt, MD, of Klinikum Stuttgart (Germany) and his associates. The findings were published online Aug. 8 in the Journal of Neurosurgery.

The noninvasive and invasive measurements produced more than 2,500 parallel ICP data points. Notably, each of the two methods produced the same number of data points. Readings averaged 10 (standard deviation, 6.1) mm Hg with invasive monitoring and 9.5 (SD, 4.7) mm Hg for noninvasive monitoring with the HS-1000. Compared with invasive ICP monitoring, the HS-1000 had a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 89% at an arbitrary cutoff of at least 17 mm Hg. Linear regression showed a “strong positive relationship between the [noninvasive and invasive] measurements,” the investigators said. In all, 63% of paired data points fell within 3 mm Hg of each other, and 85% fell within 5 mm Hg of each other. A receiver operating characteristic area under the curve analysis of the two methods generated an area under the curve of almost 90%.

The study did not include children or patients who were pregnant or had ear disease or ear injuries, rhinorrhea or otorrhea, or skull defects, the researchers said. If the HS-1000 holds up in other ongoing studies (NCT02284217, NCT02773901), physicians might be able to use it to decide if patients needs invasive ICP monitoring, they added. Use of the noninvasive method could also help prevent infections and other morbidity associated with invasive ICP monitoring in both neurocritical intensive care units and low-resource settings, they said.

HeadSense Medical sponsored the study. The researchers had no relevant disclosures.

A device that noninvasively measures intracranial pressure (ICP) had a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 89%, compared with standard invasive monitoring, based on the results of an industry-sponsored study of 14 patients with traumatic brain injury or subarachnoid hemorrhage.

“This study provides the first clinical data on the accuracy of the HS-1000 noninvasive ICP monitor, which uses advanced signal analysis algorithms to evaluate properties of acoustic signals traveling through the brain,” wrote Oliver Ganslandt, MD, of Klinikum Stuttgart (Germany) and his associates. The findings were published online Aug. 8 in the Journal of Neurosurgery.

The noninvasive and invasive measurements produced more than 2,500 parallel ICP data points. Notably, each of the two methods produced the same number of data points. Readings averaged 10 (standard deviation, 6.1) mm Hg with invasive monitoring and 9.5 (SD, 4.7) mm Hg for noninvasive monitoring with the HS-1000. Compared with invasive ICP monitoring, the HS-1000 had a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 89% at an arbitrary cutoff of at least 17 mm Hg. Linear regression showed a “strong positive relationship between the [noninvasive and invasive] measurements,” the investigators said. In all, 63% of paired data points fell within 3 mm Hg of each other, and 85% fell within 5 mm Hg of each other. A receiver operating characteristic area under the curve analysis of the two methods generated an area under the curve of almost 90%.

The study did not include children or patients who were pregnant or had ear disease or ear injuries, rhinorrhea or otorrhea, or skull defects, the researchers said. If the HS-1000 holds up in other ongoing studies (NCT02284217, NCT02773901), physicians might be able to use it to decide if patients needs invasive ICP monitoring, they added. Use of the noninvasive method could also help prevent infections and other morbidity associated with invasive ICP monitoring in both neurocritical intensive care units and low-resource settings, they said.

HeadSense Medical sponsored the study. The researchers had no relevant disclosures.

A device that noninvasively measures intracranial pressure (ICP) had a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 89%, compared with standard invasive monitoring, based on the results of an industry-sponsored study of 14 patients with traumatic brain injury or subarachnoid hemorrhage.

“This study provides the first clinical data on the accuracy of the HS-1000 noninvasive ICP monitor, which uses advanced signal analysis algorithms to evaluate properties of acoustic signals traveling through the brain,” wrote Oliver Ganslandt, MD, of Klinikum Stuttgart (Germany) and his associates. The findings were published online Aug. 8 in the Journal of Neurosurgery.

The noninvasive and invasive measurements produced more than 2,500 parallel ICP data points. Notably, each of the two methods produced the same number of data points. Readings averaged 10 (standard deviation, 6.1) mm Hg with invasive monitoring and 9.5 (SD, 4.7) mm Hg for noninvasive monitoring with the HS-1000. Compared with invasive ICP monitoring, the HS-1000 had a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 89% at an arbitrary cutoff of at least 17 mm Hg. Linear regression showed a “strong positive relationship between the [noninvasive and invasive] measurements,” the investigators said. In all, 63% of paired data points fell within 3 mm Hg of each other, and 85% fell within 5 mm Hg of each other. A receiver operating characteristic area under the curve analysis of the two methods generated an area under the curve of almost 90%.

The study did not include children or patients who were pregnant or had ear disease or ear injuries, rhinorrhea or otorrhea, or skull defects, the researchers said. If the HS-1000 holds up in other ongoing studies (NCT02284217, NCT02773901), physicians might be able to use it to decide if patients needs invasive ICP monitoring, they added. Use of the noninvasive method could also help prevent infections and other morbidity associated with invasive ICP monitoring in both neurocritical intensive care units and low-resource settings, they said.

HeadSense Medical sponsored the study. The researchers had no relevant disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF NEUROSURGERY

Key clinical point: A noninvasive device that measures intracranial pressure generated data that was comparable with standard invasive methods.

Major finding: Sensitivity was 75%, and specificity was 89%, compared with standard invasive monitoring at an arbitrary cutoff of at least 17 mm Hg.

Data source: Noninvasive and invasive intracranial pressure monitoring of 14 patients with traumatic brain injury or subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Disclosures: HeadSense Medical sponsored the study. The researchers had no relevant disclosures.

VIDEO: Study highlights risks of postponing cholecystectomy

Almost half of patients who underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) did not undergo cholecystectomy (CCY) within the next 60 days according to the results of a large, retrospective cohort study reported in the September issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.048).

“Although early and delayed CCY equally reduce the risk of subsequent recurrent biliary events, patients are at 10-fold higher risk of a recurrent biliary event while waiting for a delayed CCY, compared with patients who underwent early CCY,” wrote Robert J. Huang, MD, and his associates of Stanford (Calif.) University Medical Center. Delayed CCY is cost effective, but that benefit must be weighed against the risk of loss to follow-up, especially if patients have “little or no health insurance,” they said.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

Gallstone disease affects up to 15% of adults in developed societies, including about 20-25 million Americans. Yearly costs of treatment tally at more than $6.2 billion and have risen by more than 20% in 3 decades, according to multiple studies. Approximately 20% of patients with gallstone disease have choledocholithiasis, mainly because gallstones can pass from the gallbladder into the common bile duct. After undergoing ERCP, such patients are typically referred for CCY, but there are no “societal guidelines” on timing the referral, the researchers said. Practice patterns remain “largely institution based and may be subject to the vagaries of surgeon availability and other institutional resource constraints.” One prior study linked a median 7-week wait time for CCY with a 20% rate of recurrent biliary events. To evaluate large-scale practice patterns, the researchers studied 4,516 patients who had undergone ERCP for choledocholithiasis in California (during 2009-2011), New York (during 2011-2013), and Florida (during 2012-2014) and calculated timing and rates of subsequent CCY, recurrent biliary events, and deaths. Patients were followed for up to 365 days after ERCP.

Of the 4,516 patients studied, 1,859 (41.2%) patients underwent CCY during their index hospital admission (early CCY). Of the 2,657 (58.8%) patients who were discharged without CCY, only 491 (18%) had a planned CCY within 60 days (delayed CCY), 350 (71.3%) of which were done in an outpatient setting. Of the patients in the study, 2,168 (48.0%) did not have a CCY (no CCY) during their index visit or within 60 days. Over 365 days of follow-up, 10% of patients who did not have a CCY had recurrent biliary events, compared with 1.3% of patients who underwent early or delayed CCY. The risk of recurrent biliary events for patients who underwent early or delayed CCY was about 88% lower than if they had had no CCY within 60 days of ERCP (P less than .001 for each comparison). Performing CCY during index admission cut the risk of recurrent biliary events occurring within 60 days by 92%, compared with delayed or no CCY (P less than .001).

In all, 15 (0.7%) patients who did not undergo CCY died after subsequent hospitalization for a recurrent biliary event, compared with 1 patient who underwent early CCY (0.1%; P less than .001). There were no deaths associated with recurrent biliary events in the delayed-CCY group. Rates of all-cause mortality over 365 days were 3.1% in the no-CCY group, 0.6% in the early-CCY group, and 0% in the delayed-CCY group. Thus, cumulative death rates were about seven times higher among patients who did not undergo CCY compared with those who did (P less than .001).

Patients who did not undergo CCY tended to be older than delayed- and early-CCY patients (mean ages 66 years, 58 years, and 52 years, respectively). No-CCY patients also tended to have more comorbidities. Nonetheless, having an early CCY retained a “robust” protective effect against recurrent biliary events after accounting for age, sex, comorbidities, stent placement, facility volume, and state of residence. Even after researchers adjusted for those factors, the protective effect of early CCY dropped by less than 5% (from 92% to about 87%), the investigators said.

They also noted that the overall cohort averaged 60 years of age and that 64% were female, which is consistent with the epidemiology of biliary stone disease. Just over half were non-Hispanic whites. Medicare was the single largest primary payer (46%), followed by private insurance (28%) and Medicaid (16%).

“A strategy of delayed CCY performed on an outpatient basis was least costly,” the researchers said. “Performance of early CCY was inversely associated with low facility volume. Hispanic race, Asian race, Medicaid insurance, and no insurance associated inversely with performance of delayed CCY.”

Funders included a seed grant from the Stanford division of gastroenterology and hepatology and the National Institutes of Health. The investigators had no conflicts of interest.

Almost half of patients who underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) did not undergo cholecystectomy (CCY) within the next 60 days according to the results of a large, retrospective cohort study reported in the September issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.048).

“Although early and delayed CCY equally reduce the risk of subsequent recurrent biliary events, patients are at 10-fold higher risk of a recurrent biliary event while waiting for a delayed CCY, compared with patients who underwent early CCY,” wrote Robert J. Huang, MD, and his associates of Stanford (Calif.) University Medical Center. Delayed CCY is cost effective, but that benefit must be weighed against the risk of loss to follow-up, especially if patients have “little or no health insurance,” they said.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

Gallstone disease affects up to 15% of adults in developed societies, including about 20-25 million Americans. Yearly costs of treatment tally at more than $6.2 billion and have risen by more than 20% in 3 decades, according to multiple studies. Approximately 20% of patients with gallstone disease have choledocholithiasis, mainly because gallstones can pass from the gallbladder into the common bile duct. After undergoing ERCP, such patients are typically referred for CCY, but there are no “societal guidelines” on timing the referral, the researchers said. Practice patterns remain “largely institution based and may be subject to the vagaries of surgeon availability and other institutional resource constraints.” One prior study linked a median 7-week wait time for CCY with a 20% rate of recurrent biliary events. To evaluate large-scale practice patterns, the researchers studied 4,516 patients who had undergone ERCP for choledocholithiasis in California (during 2009-2011), New York (during 2011-2013), and Florida (during 2012-2014) and calculated timing and rates of subsequent CCY, recurrent biliary events, and deaths. Patients were followed for up to 365 days after ERCP.

Of the 4,516 patients studied, 1,859 (41.2%) patients underwent CCY during their index hospital admission (early CCY). Of the 2,657 (58.8%) patients who were discharged without CCY, only 491 (18%) had a planned CCY within 60 days (delayed CCY), 350 (71.3%) of which were done in an outpatient setting. Of the patients in the study, 2,168 (48.0%) did not have a CCY (no CCY) during their index visit or within 60 days. Over 365 days of follow-up, 10% of patients who did not have a CCY had recurrent biliary events, compared with 1.3% of patients who underwent early or delayed CCY. The risk of recurrent biliary events for patients who underwent early or delayed CCY was about 88% lower than if they had had no CCY within 60 days of ERCP (P less than .001 for each comparison). Performing CCY during index admission cut the risk of recurrent biliary events occurring within 60 days by 92%, compared with delayed or no CCY (P less than .001).

In all, 15 (0.7%) patients who did not undergo CCY died after subsequent hospitalization for a recurrent biliary event, compared with 1 patient who underwent early CCY (0.1%; P less than .001). There were no deaths associated with recurrent biliary events in the delayed-CCY group. Rates of all-cause mortality over 365 days were 3.1% in the no-CCY group, 0.6% in the early-CCY group, and 0% in the delayed-CCY group. Thus, cumulative death rates were about seven times higher among patients who did not undergo CCY compared with those who did (P less than .001).

Patients who did not undergo CCY tended to be older than delayed- and early-CCY patients (mean ages 66 years, 58 years, and 52 years, respectively). No-CCY patients also tended to have more comorbidities. Nonetheless, having an early CCY retained a “robust” protective effect against recurrent biliary events after accounting for age, sex, comorbidities, stent placement, facility volume, and state of residence. Even after researchers adjusted for those factors, the protective effect of early CCY dropped by less than 5% (from 92% to about 87%), the investigators said.

They also noted that the overall cohort averaged 60 years of age and that 64% were female, which is consistent with the epidemiology of biliary stone disease. Just over half were non-Hispanic whites. Medicare was the single largest primary payer (46%), followed by private insurance (28%) and Medicaid (16%).

“A strategy of delayed CCY performed on an outpatient basis was least costly,” the researchers said. “Performance of early CCY was inversely associated with low facility volume. Hispanic race, Asian race, Medicaid insurance, and no insurance associated inversely with performance of delayed CCY.”

Funders included a seed grant from the Stanford division of gastroenterology and hepatology and the National Institutes of Health. The investigators had no conflicts of interest.

Almost half of patients who underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) did not undergo cholecystectomy (CCY) within the next 60 days according to the results of a large, retrospective cohort study reported in the September issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.048).

“Although early and delayed CCY equally reduce the risk of subsequent recurrent biliary events, patients are at 10-fold higher risk of a recurrent biliary event while waiting for a delayed CCY, compared with patients who underwent early CCY,” wrote Robert J. Huang, MD, and his associates of Stanford (Calif.) University Medical Center. Delayed CCY is cost effective, but that benefit must be weighed against the risk of loss to follow-up, especially if patients have “little or no health insurance,” they said.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

Gallstone disease affects up to 15% of adults in developed societies, including about 20-25 million Americans. Yearly costs of treatment tally at more than $6.2 billion and have risen by more than 20% in 3 decades, according to multiple studies. Approximately 20% of patients with gallstone disease have choledocholithiasis, mainly because gallstones can pass from the gallbladder into the common bile duct. After undergoing ERCP, such patients are typically referred for CCY, but there are no “societal guidelines” on timing the referral, the researchers said. Practice patterns remain “largely institution based and may be subject to the vagaries of surgeon availability and other institutional resource constraints.” One prior study linked a median 7-week wait time for CCY with a 20% rate of recurrent biliary events. To evaluate large-scale practice patterns, the researchers studied 4,516 patients who had undergone ERCP for choledocholithiasis in California (during 2009-2011), New York (during 2011-2013), and Florida (during 2012-2014) and calculated timing and rates of subsequent CCY, recurrent biliary events, and deaths. Patients were followed for up to 365 days after ERCP.

Of the 4,516 patients studied, 1,859 (41.2%) patients underwent CCY during their index hospital admission (early CCY). Of the 2,657 (58.8%) patients who were discharged without CCY, only 491 (18%) had a planned CCY within 60 days (delayed CCY), 350 (71.3%) of which were done in an outpatient setting. Of the patients in the study, 2,168 (48.0%) did not have a CCY (no CCY) during their index visit or within 60 days. Over 365 days of follow-up, 10% of patients who did not have a CCY had recurrent biliary events, compared with 1.3% of patients who underwent early or delayed CCY. The risk of recurrent biliary events for patients who underwent early or delayed CCY was about 88% lower than if they had had no CCY within 60 days of ERCP (P less than .001 for each comparison). Performing CCY during index admission cut the risk of recurrent biliary events occurring within 60 days by 92%, compared with delayed or no CCY (P less than .001).

In all, 15 (0.7%) patients who did not undergo CCY died after subsequent hospitalization for a recurrent biliary event, compared with 1 patient who underwent early CCY (0.1%; P less than .001). There were no deaths associated with recurrent biliary events in the delayed-CCY group. Rates of all-cause mortality over 365 days were 3.1% in the no-CCY group, 0.6% in the early-CCY group, and 0% in the delayed-CCY group. Thus, cumulative death rates were about seven times higher among patients who did not undergo CCY compared with those who did (P less than .001).

Patients who did not undergo CCY tended to be older than delayed- and early-CCY patients (mean ages 66 years, 58 years, and 52 years, respectively). No-CCY patients also tended to have more comorbidities. Nonetheless, having an early CCY retained a “robust” protective effect against recurrent biliary events after accounting for age, sex, comorbidities, stent placement, facility volume, and state of residence. Even after researchers adjusted for those factors, the protective effect of early CCY dropped by less than 5% (from 92% to about 87%), the investigators said.

They also noted that the overall cohort averaged 60 years of age and that 64% were female, which is consistent with the epidemiology of biliary stone disease. Just over half were non-Hispanic whites. Medicare was the single largest primary payer (46%), followed by private insurance (28%) and Medicaid (16%).

“A strategy of delayed CCY performed on an outpatient basis was least costly,” the researchers said. “Performance of early CCY was inversely associated with low facility volume. Hispanic race, Asian race, Medicaid insurance, and no insurance associated inversely with performance of delayed CCY.”

Funders included a seed grant from the Stanford division of gastroenterology and hepatology and the National Institutes of Health. The investigators had no conflicts of interest.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Almost half of patients who underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) did not undergo cholecystectomy within 60 days.

Major finding: A total of 48% had no cholecystectomy within 60 days. Performing cholecystectomy during index admission cut the risk of recurrent biliary events within 60 days by 92%, compared with delayed or no cholecystectomy (P less than .001).

Data source: A multistate, retrospective study of 4,516 patients hospitalized with choledocholithiasis.

Disclosures: Funders included a Stanford division of gastroenterology and hepatology divisional seed grant and the National Institutes of Health. The investigators had no conflicts of interest.

Minimally invasive screening for Barrett’s esophagus offers cost-effective alternative

The high costs of endoscopy make screening patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) for Barrett’s esophagus a costly endeavor. But using a minimally invasive test followed by endoscopy only if results are positive could cut costs by up to 41%, according to investigators.

The report is in the September issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.02.017).

The findings mirror those from a prior study (Gastroenterology. 2013 Jan;144[1]:62-73.e60) of the new cytosponge device, which tests surface esophageal tissue for trefoil factor 3, a biomarker for Barrett’s esophagus, said Curtis R. Heberle, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and his associates. In addition, two separate models found the cytosponge strategy cost effective compared with no screening (incremental cost-effectiveness ratios [ICERs], about $26,000-$33,000). However, using the cytosponge instead of screening all GERD patients with endoscopy would reduce quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) by about 1.8-5.5 years for every 1,000 patients.

Rates of esophageal adenocarcinoma have climbed more than sixfold in the United States in 4 decades, and 5-year survival rates remain below 20%. Nonetheless, the high cost of endoscopy and 10%-20% prevalence of GERD makes screening all patients for Barrett’s esophagus infeasible. To evaluate the cytosponge strategy, the researchers fit data from the multicenter BEST2 study (PLoS Med. 2015 Jan; 12[1]: e1001780) into two validated models calibrated to high-quality Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data on esophageal cancer. Both models compared no screening with a one-time screen by either endoscopy alone or cytosponge with follow-up endoscopy in the event of a positive test. The models assumed patients were male, were 60 years old, and had GERD but not esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Without screening, there were about 14-16 cancer cases and about 15,077 quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) for every 1,000 patients. The cytosponge strategy was associated with about 8-13 cancer cases and about 15,105 QALYs. Endoscopic screening produced the most benefit overall – only about 7-12 cancer cases, with more than 15,100 QALYs. “However, greater benefits were accompanied by higher total costs,” the researchers said. For every 1,000 patients, no screening cost about $704,000 to $762,000, the cytosponge strategy cost about $1.5 to $1.6 million, and population-wide endoscopy cost about $2.1 to $2.2 million. Thus, the cytosponge method would lower the cost of screening by 37%-41% compared with endoscopically screening all men with GERD. The cytosponge was also cost effective in a model of 60-year-old women with GERD.

Using only endoscopic screening was not cost effective in either model, exceeding a $100,000 threshold of willingness to pay by anywhere from $107,000 to $330,000. The cytosponge is not yet available commercially, but the investigators assumed it cost $182 based on information from the manufacturer (Medtronic) and Medicare payments for similar devices. Although the findings withstood variations in indirect costs and age at initial screening, they were “somewhat sensitive” to variations in costs of the cytosponge and its presumed sensitivity and specificity in clinical settings. However, endoscopic screening only became cost effective when the cytosponge test cost at least $225.

The models assumed perfect adherence to screening, which probably exaggerated the effectiveness of the cytosponge and endoscopic screening, the investigators said. They noted that cytosponge screening can be performed without sedation during a short outpatient visit.

The National Institutes of Health provided funding. The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

The high costs of endoscopy make screening patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) for Barrett’s esophagus a costly endeavor. But using a minimally invasive test followed by endoscopy only if results are positive could cut costs by up to 41%, according to investigators.

The report is in the September issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.02.017).

The findings mirror those from a prior study (Gastroenterology. 2013 Jan;144[1]:62-73.e60) of the new cytosponge device, which tests surface esophageal tissue for trefoil factor 3, a biomarker for Barrett’s esophagus, said Curtis R. Heberle, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and his associates. In addition, two separate models found the cytosponge strategy cost effective compared with no screening (incremental cost-effectiveness ratios [ICERs], about $26,000-$33,000). However, using the cytosponge instead of screening all GERD patients with endoscopy would reduce quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) by about 1.8-5.5 years for every 1,000 patients.

Rates of esophageal adenocarcinoma have climbed more than sixfold in the United States in 4 decades, and 5-year survival rates remain below 20%. Nonetheless, the high cost of endoscopy and 10%-20% prevalence of GERD makes screening all patients for Barrett’s esophagus infeasible. To evaluate the cytosponge strategy, the researchers fit data from the multicenter BEST2 study (PLoS Med. 2015 Jan; 12[1]: e1001780) into two validated models calibrated to high-quality Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data on esophageal cancer. Both models compared no screening with a one-time screen by either endoscopy alone or cytosponge with follow-up endoscopy in the event of a positive test. The models assumed patients were male, were 60 years old, and had GERD but not esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Without screening, there were about 14-16 cancer cases and about 15,077 quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) for every 1,000 patients. The cytosponge strategy was associated with about 8-13 cancer cases and about 15,105 QALYs. Endoscopic screening produced the most benefit overall – only about 7-12 cancer cases, with more than 15,100 QALYs. “However, greater benefits were accompanied by higher total costs,” the researchers said. For every 1,000 patients, no screening cost about $704,000 to $762,000, the cytosponge strategy cost about $1.5 to $1.6 million, and population-wide endoscopy cost about $2.1 to $2.2 million. Thus, the cytosponge method would lower the cost of screening by 37%-41% compared with endoscopically screening all men with GERD. The cytosponge was also cost effective in a model of 60-year-old women with GERD.

Using only endoscopic screening was not cost effective in either model, exceeding a $100,000 threshold of willingness to pay by anywhere from $107,000 to $330,000. The cytosponge is not yet available commercially, but the investigators assumed it cost $182 based on information from the manufacturer (Medtronic) and Medicare payments for similar devices. Although the findings withstood variations in indirect costs and age at initial screening, they were “somewhat sensitive” to variations in costs of the cytosponge and its presumed sensitivity and specificity in clinical settings. However, endoscopic screening only became cost effective when the cytosponge test cost at least $225.

The models assumed perfect adherence to screening, which probably exaggerated the effectiveness of the cytosponge and endoscopic screening, the investigators said. They noted that cytosponge screening can be performed without sedation during a short outpatient visit.

The National Institutes of Health provided funding. The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

The high costs of endoscopy make screening patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) for Barrett’s esophagus a costly endeavor. But using a minimally invasive test followed by endoscopy only if results are positive could cut costs by up to 41%, according to investigators.

The report is in the September issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.02.017).

The findings mirror those from a prior study (Gastroenterology. 2013 Jan;144[1]:62-73.e60) of the new cytosponge device, which tests surface esophageal tissue for trefoil factor 3, a biomarker for Barrett’s esophagus, said Curtis R. Heberle, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and his associates. In addition, two separate models found the cytosponge strategy cost effective compared with no screening (incremental cost-effectiveness ratios [ICERs], about $26,000-$33,000). However, using the cytosponge instead of screening all GERD patients with endoscopy would reduce quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) by about 1.8-5.5 years for every 1,000 patients.

Rates of esophageal adenocarcinoma have climbed more than sixfold in the United States in 4 decades, and 5-year survival rates remain below 20%. Nonetheless, the high cost of endoscopy and 10%-20% prevalence of GERD makes screening all patients for Barrett’s esophagus infeasible. To evaluate the cytosponge strategy, the researchers fit data from the multicenter BEST2 study (PLoS Med. 2015 Jan; 12[1]: e1001780) into two validated models calibrated to high-quality Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data on esophageal cancer. Both models compared no screening with a one-time screen by either endoscopy alone or cytosponge with follow-up endoscopy in the event of a positive test. The models assumed patients were male, were 60 years old, and had GERD but not esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Without screening, there were about 14-16 cancer cases and about 15,077 quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) for every 1,000 patients. The cytosponge strategy was associated with about 8-13 cancer cases and about 15,105 QALYs. Endoscopic screening produced the most benefit overall – only about 7-12 cancer cases, with more than 15,100 QALYs. “However, greater benefits were accompanied by higher total costs,” the researchers said. For every 1,000 patients, no screening cost about $704,000 to $762,000, the cytosponge strategy cost about $1.5 to $1.6 million, and population-wide endoscopy cost about $2.1 to $2.2 million. Thus, the cytosponge method would lower the cost of screening by 37%-41% compared with endoscopically screening all men with GERD. The cytosponge was also cost effective in a model of 60-year-old women with GERD.

Using only endoscopic screening was not cost effective in either model, exceeding a $100,000 threshold of willingness to pay by anywhere from $107,000 to $330,000. The cytosponge is not yet available commercially, but the investigators assumed it cost $182 based on information from the manufacturer (Medtronic) and Medicare payments for similar devices. Although the findings withstood variations in indirect costs and age at initial screening, they were “somewhat sensitive” to variations in costs of the cytosponge and its presumed sensitivity and specificity in clinical settings. However, endoscopic screening only became cost effective when the cytosponge test cost at least $225.

The models assumed perfect adherence to screening, which probably exaggerated the effectiveness of the cytosponge and endoscopic screening, the investigators said. They noted that cytosponge screening can be performed without sedation during a short outpatient visit.

The National Institutes of Health provided funding. The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Using a minimally invasive screen for Barrett’s esophagus and following up with endoscopy if results are positive is a cost-effective alternative to endoscopy alone in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Major finding: The two-step screening strategy cut screening costs by 37%-41% but was associated with 1.8-5.5 fewer quality-adjusted life years for every 1,000 patients with GERD.

Data source: Two validated models based on Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data, and data from the multicenter BEST2 trial.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health provided funding. The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

VIDEO: Large distal nongranular colorectal polyps were most likely to contain occult invasive cancers

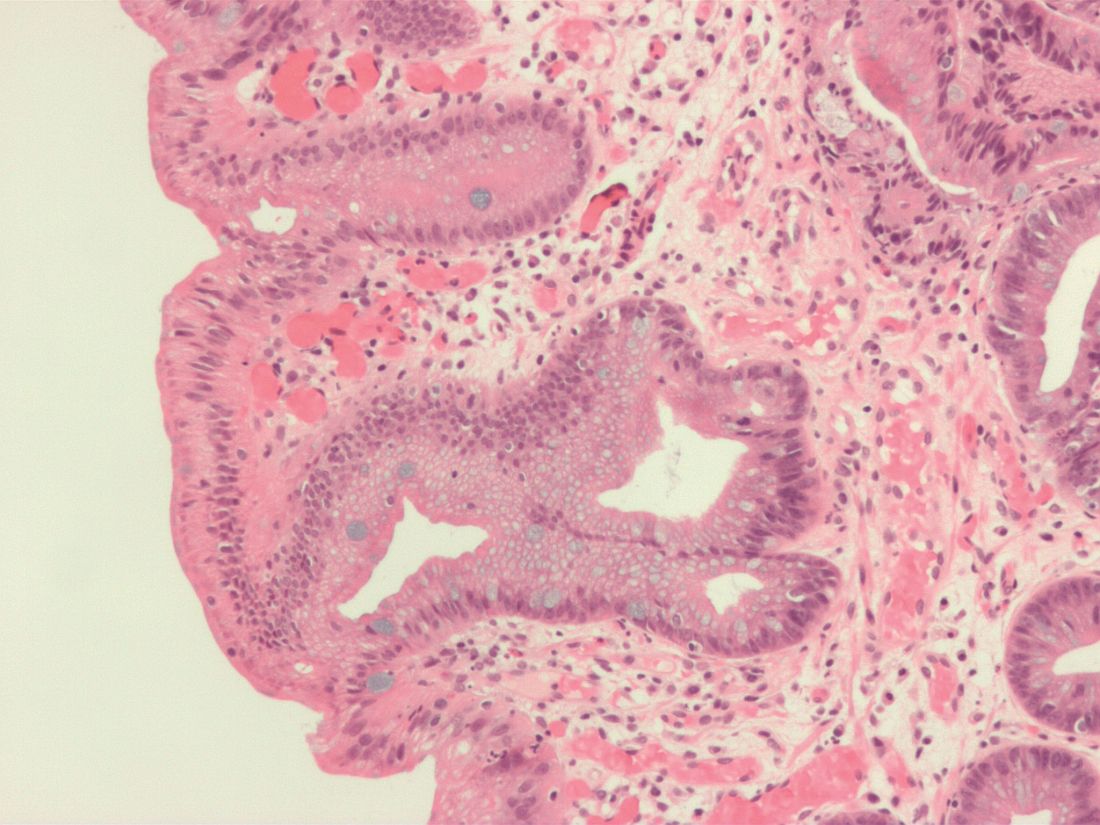

Large sessile or flat colorectal polyps or laterally spreading lesions were most likely to contain covert malignancies when their location was rectosigmoid, their Paris classification was 0-Is or 0-IIa+Is, and they were nongranular, according to the results of a multicenter prospective cohort study of 2,106 consecutive patients reported in the September issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.047).

“Distal nongranular lesions have a high risk of occult SMIC [submucosal invasive cancer], whereas proximal, granular 0-IIa lesions, after a careful assessment for features associated with SMIC, have a very low risk,” wrote Nicholas G. Burgess, MD, of Westmead Hospital, Sydney, with his associates. “These findings can be used to inform decisions [about] which patients should undergo endoscopic submucosal dissection, endoscopic mucosal resection, or surgery.”

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

Many studies of colonic lesions have examined predictors of SMIC. Nonetheless, clinicians need more information on factors that improve clinical decision making, especially as colonic endoscopic submucosal dissection becomes more accessible, the researchers said. Large colonic lesions can contain submucosal invasive SMICs that are not visible on endoscopy, and characterizing predictors of this occurrence could help patients and clinicians decide between endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection. To do so, the researchers analyzed histologic specimens from 2,277 colonic lesions above 20 mm (average size, 37 mm) that lacked overt endoscopic high-risk features. The study ran from 2008 through 2016, study participants averaged 68 years of age, and 53% were male. A total of 171 lesions (8%) had evidence of SMIC on pathologic review, and 138 lesions had covert SMIC. Predictors of overt and occult SMIC included Kudo pit pattern V, a depressed component (0-IIc), rectosigmoid location, 0-Is or 0-IIa+Is Paris classification, nongranular surface morphology, and larger size. After excluding lesions with obvious SMIC features – including serrated lesions and those with depressed components (Kudo pit pattern of V and Paris 0-IIc) – the strongest predictors of occult SMIC included Paris classification, surface morphology, size, and location.

“Proximal 0-IIa G or 0-Is granular lesions had the lowest risk of SMIC (0.7% and 2.3%), whereas distal 0-Is nongranular lesions had the highest risk (21.4%),” the investigators added. Lesion location, size, and combined Paris classification and surface topography showed the best fit in a multivariable model. Notably, rectosigmoid lesions had nearly twice the odds of containing covert SMIC, compared with proximal lesions (odds ratio, 1.9; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-3.0; P = .01). Other significant predictors of covert SMIC in the multivariable model included combined Paris classification, surface morphology (OR, 4.0; 95% CI, 1.2-12.7; P = .02), and increasing size (OR, 1.2 per 10-mm increase; 95% CI, 1.04-1.3; P = .01). Increased size showed an even greater effect in lesions exceeding 50 mm.

Clinicians can use these factors to help evaluate risk of invasive cancer in lesions without overt SMIC, the researchers said. “One lesion type that differs from the pattern is 0-IIa nongranular lesions,” they noted. “Once lesions with overt evidence of SMIC are excluded, these lesions have a low risk (4.2%) of harboring underlying cancer.” Although 42% of lesions with covert SMIC were SM1 (potentially curable by endoscopic resection), no predictor of covert SMIC also predicted SMI status.

Funders included Cancer Institute of New South Wales and Gallipoli Medical Research Foundation. The investigators had no conflicts of interest.

In recent years, substantial efforts have been made to improve both colonoscopy preparation and endoscopic image quality to achieve improved polyp detection. In addition, while large, complex colon polyps (typically greater than 20 mm in size) previously were often referred for surgical resection, improved polyp resection techniques and equipment have led to the ability to remove many such lesions in a piecemeal fashion or en bloc via endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD).

The authors are to be congratulated for their meticulous and sustained efforts in acquiring and analyzing this data. These results provide endoscopists with some important, practical, and entirely visual criteria to assess upon identification of large colon polyps that can aid in determining which type of endoscopy therapy, if any, to embark upon. Avoiding EMR when there is a reasonably high probability of invasive disease will allow for choosing a more appropriate technique such as ESD (which is becoming increasingly available in the West) or surgery. In addition, patients can avoid the unnecessary EMR-related risks of bleeding and perforation when this technique is likely to result in an inadequate resection. Future work should assess whether this information can be widely adopted and utilized to achieve similar predictive accuracy in nonexpert settings.

V. Raman Muthusamy, MD, is director, interventional and general endoscopy, clinical professor of medicine, digestive diseases/gastroenterology, University of California, Los Angeles School of Medicine. He is a consultant for Medtronic and Boston Scientific.

In recent years, substantial efforts have been made to improve both colonoscopy preparation and endoscopic image quality to achieve improved polyp detection. In addition, while large, complex colon polyps (typically greater than 20 mm in size) previously were often referred for surgical resection, improved polyp resection techniques and equipment have led to the ability to remove many such lesions in a piecemeal fashion or en bloc via endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD).

The authors are to be congratulated for their meticulous and sustained efforts in acquiring and analyzing this data. These results provide endoscopists with some important, practical, and entirely visual criteria to assess upon identification of large colon polyps that can aid in determining which type of endoscopy therapy, if any, to embark upon. Avoiding EMR when there is a reasonably high probability of invasive disease will allow for choosing a more appropriate technique such as ESD (which is becoming increasingly available in the West) or surgery. In addition, patients can avoid the unnecessary EMR-related risks of bleeding and perforation when this technique is likely to result in an inadequate resection. Future work should assess whether this information can be widely adopted and utilized to achieve similar predictive accuracy in nonexpert settings.

V. Raman Muthusamy, MD, is director, interventional and general endoscopy, clinical professor of medicine, digestive diseases/gastroenterology, University of California, Los Angeles School of Medicine. He is a consultant for Medtronic and Boston Scientific.

In recent years, substantial efforts have been made to improve both colonoscopy preparation and endoscopic image quality to achieve improved polyp detection. In addition, while large, complex colon polyps (typically greater than 20 mm in size) previously were often referred for surgical resection, improved polyp resection techniques and equipment have led to the ability to remove many such lesions in a piecemeal fashion or en bloc via endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD).

The authors are to be congratulated for their meticulous and sustained efforts in acquiring and analyzing this data. These results provide endoscopists with some important, practical, and entirely visual criteria to assess upon identification of large colon polyps that can aid in determining which type of endoscopy therapy, if any, to embark upon. Avoiding EMR when there is a reasonably high probability of invasive disease will allow for choosing a more appropriate technique such as ESD (which is becoming increasingly available in the West) or surgery. In addition, patients can avoid the unnecessary EMR-related risks of bleeding and perforation when this technique is likely to result in an inadequate resection. Future work should assess whether this information can be widely adopted and utilized to achieve similar predictive accuracy in nonexpert settings.

V. Raman Muthusamy, MD, is director, interventional and general endoscopy, clinical professor of medicine, digestive diseases/gastroenterology, University of California, Los Angeles School of Medicine. He is a consultant for Medtronic and Boston Scientific.

Large sessile or flat colorectal polyps or laterally spreading lesions were most likely to contain covert malignancies when their location was rectosigmoid, their Paris classification was 0-Is or 0-IIa+Is, and they were nongranular, according to the results of a multicenter prospective cohort study of 2,106 consecutive patients reported in the September issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.047).

“Distal nongranular lesions have a high risk of occult SMIC [submucosal invasive cancer], whereas proximal, granular 0-IIa lesions, after a careful assessment for features associated with SMIC, have a very low risk,” wrote Nicholas G. Burgess, MD, of Westmead Hospital, Sydney, with his associates. “These findings can be used to inform decisions [about] which patients should undergo endoscopic submucosal dissection, endoscopic mucosal resection, or surgery.”

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

Many studies of colonic lesions have examined predictors of SMIC. Nonetheless, clinicians need more information on factors that improve clinical decision making, especially as colonic endoscopic submucosal dissection becomes more accessible, the researchers said. Large colonic lesions can contain submucosal invasive SMICs that are not visible on endoscopy, and characterizing predictors of this occurrence could help patients and clinicians decide between endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection. To do so, the researchers analyzed histologic specimens from 2,277 colonic lesions above 20 mm (average size, 37 mm) that lacked overt endoscopic high-risk features. The study ran from 2008 through 2016, study participants averaged 68 years of age, and 53% were male. A total of 171 lesions (8%) had evidence of SMIC on pathologic review, and 138 lesions had covert SMIC. Predictors of overt and occult SMIC included Kudo pit pattern V, a depressed component (0-IIc), rectosigmoid location, 0-Is or 0-IIa+Is Paris classification, nongranular surface morphology, and larger size. After excluding lesions with obvious SMIC features – including serrated lesions and those with depressed components (Kudo pit pattern of V and Paris 0-IIc) – the strongest predictors of occult SMIC included Paris classification, surface morphology, size, and location.