User login

Pediatricians partner with hospitals for value-based models

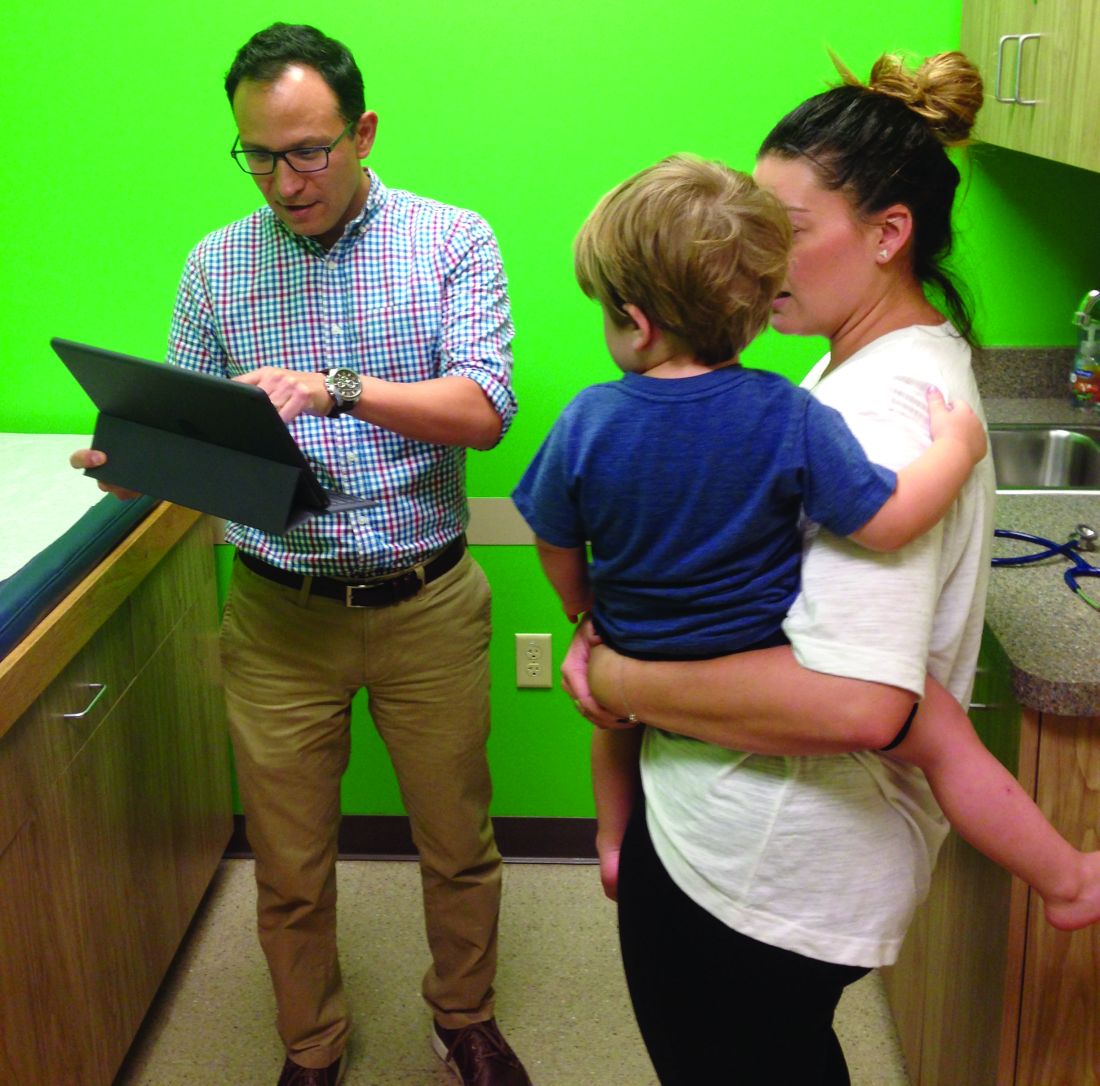

When Jason Vargas, MD, first moved to the Phoenix area 13 years ago, he found an atmosphere of distant relationships between general pediatricians like him, subspecialists, and hospitals. Getting patients a referral to a subspecialist could take months, and communication among providers was often weak, Dr. Vargas said.

Today, things are vastly different thanks in large part to the clinically integrated network of which Dr. Vargas and 950 area providers are a part.

Phoenix Children’s Care Network (PCCN), established in 2014, coordinates health care across multiple providers and settings in the Phoenix area, including half of all general pediatricians and 80% of pediatric subspecialists practicing in Maricopa County. The network is a value- and risk-based system that provides financial incentives to participating providers and health systems that meet established quality metrics. Patients have access to 950 providers within the network, including primary and specialty care sites of service, urgent care locations, surgery centers, and Phoenix Children’s Hospital.

Meanwhile, 2,000 miles away, another unique payment model is changing the way pediatric care is delivered in the Columbus, Ohio area. Partners For Kids (PFK) is a pediatric accountable care organization (ACO) that coordinates care between Nationwide Children’s Hospital and more than 1,000 doctors. Through its 20-year evolution, PFK has successfully assumed full financial and clinical risk for children under age 19 enrolled in Medicaid managed care. This means PFK is responsible for paying for the costs of all patient care, no matter how much or where that care occurs.

The two models illustrate how pediatricians are affiliating with value-centric networks while keeping their independence, said Timothy Johnson, senior vice president of pediatrics at Valence Health, a consulting firm that helps health providers transition to value-based care.

With MACRA (the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015) “it’s going to be difficult for individual pediatricians to do what is required in a value-based medical system because they just don’t have the resources,” Mr. Johnson said in an interview. “That doesn’t mean they can’t be independent. It means they are going to have to band together in some way, whether with a health system, with other practices. It is extremely important for pediatricians to start thinking about how to do that.”

Going from splintered to unified

Like most communities, care delivery in the Phoenix area was relatively fractured prior to 2014. To bring everyone together, Phoenix Children’s started with community outreach and education.

Along with building trust among providers, project leaders had to overcome operational hurdles. This included creating a process for 110 practices to collectively negotiate contracts, operate under a new structure, and adhere to quality metrics, he said.

“Operationally, you have to take 110 different ways of doing things and try merge them into one common way as you develop these new contractual risk-based models,” he said. “At the same time, we had to transition people away from what they were used to as a purely fee-for-service model. It was a very big operational transition.”

To bolster engagement by community pediatricians, PCCN developed a physician-governance approach, assigning participating providers leadership responsibilities. Participating physicians then worked to create the benchmarks by which doctors are measured against. To date, provider performance is tracked against 14 primary care and 34 specialist metrics encompassing engagement, safety, quality, and transparency.

PCCN leaders also had to ensure that participating in such a network was beneficial for busy doctors, said Dr. Vargas, who is chair of the PCCN Network and Utilization committee and a member of the network’s board of managers.

Asking physicians to change their framework, track patient data, and meet metrics, all while potentially losing money if they fail to hit benchmarks is not the most popular proposition, he said. So PCCN created advantages for member doctors, such as nighttime pediatric triage, a negotiated discount for professional services, IT support, streamlined access to specialists, and more avenues to communicate with subspecialists.

“With so many schedules, professional, and academic pressures on our daily professional lives, we have wanted to make sure that there were practical value added benefits to members,” he said. “I think right now that the benefits outweigh the administrative burdens.”

A changing payer relationship

As a network, PCCN works with payers to assume the risk that insurers have historically taken. Payers continue to handle the administrative and billing side of the equation, while the network controls the medical management and care coordination of the patient population, Mr. Johnson said.

“We feel we can do it much more efficiently, much more effectively, and we feel it’s better care for the patient when we’re the one controlling that,” he said. “The insurance companies don’t disagree.”

The network partners with Medicaid and commercial payers and has a direct-to-employer agreement with a major employer in conjunction with an adult partner system/network. Early performance efforts by the PCCN have been rewarded by shared savings disbursements from two payers, according to PCCN officials. The network has also met or exceeded state Medicaid pediatric quality targets and consistently contained medical expenses below expected medical cost trends for its managed pediatric populations.

Building a population health model

For more than 2 decades, PFK in Ohio has taken a novel care delivery approach that has focused on value and community partnerships.

Back in 1994, Nationwide Children’s Hospital partnered with community pediatricians to create PFK, a physician/hospital organization with governance shared equally. Today, PFK has assumed full financial and clinical risk for pediatric managed Medicaid enrollees, and is the largest and oldest known pediatric ACO.

A key hurdle was collecting timely, complete, and accurate data for the patient population, Dr. Gleeson said, adding that working with data and understanding changing trends is an everyday challenge. Interacting with busy physicians and securing their time and cooperation also has been an obstacle.

“The lessons learned for us is that we really need to approach them understanding that there is a limited amount of time that practices can invest in infrastructure or invest in the processes of care,” he said. “We have to approach things knowing that [doctors] are going to struggle with the amount of time necessary to engage in large projects, so it needs to be chopped up into bite-sized pieces that they can consume on the run, so they can keep their practices running well.”

PFK efforts have paid off in terms of lowering costs and improving care. Between 2008 and 2013, PFK achieved lower cost growth than Medicaid fee-for-service programs and managed care plans in the Columbus, Ohio, area (Pediatrics. 2015 Mar;135[3];e582-9).

Fundamentally, the model has remained the same over the years, Dr. Gleeson said, but in 2005, PFK made the decision to expand and take responsibility for all the Medicaid-enrolled children in the region.

“It really gives a much broader field of view and perspective on patients in the region,” he said. “We know that they are all our responsibility so we take more of a population health type of approach, working with any physician who is caring for those children.”

Guidance for other practices

Dr. Gleeson encouraged other pediatricians interested in transitioning to value-based care to start by evaluating their data. Take a hard look at the quality of care you provide and begin to measure it, he said. For smaller practices, consider joining a larger group or network that will allow pediatricians to engage in collaborative work, he added.

Dr. Vargas stressed that change is coming whether pediatricians are prepared or not. Aligning with the right partners will be the difference between sinking or staying afloat in the value-based landscape.

“Payers are moving toward value-based models and it is not practical for the general pediatrician to be able to provide the infrastructure and professional resources necessary,” he said. “To maintain our professional livelihood as independent pediatricians, and to continue to provide the individually crafted, quality care our families are accustomed to, we will have to align ourselves with organizations that value the experience and insight of the independent pediatrician to deliver that care.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

When Jason Vargas, MD, first moved to the Phoenix area 13 years ago, he found an atmosphere of distant relationships between general pediatricians like him, subspecialists, and hospitals. Getting patients a referral to a subspecialist could take months, and communication among providers was often weak, Dr. Vargas said.

Today, things are vastly different thanks in large part to the clinically integrated network of which Dr. Vargas and 950 area providers are a part.

Phoenix Children’s Care Network (PCCN), established in 2014, coordinates health care across multiple providers and settings in the Phoenix area, including half of all general pediatricians and 80% of pediatric subspecialists practicing in Maricopa County. The network is a value- and risk-based system that provides financial incentives to participating providers and health systems that meet established quality metrics. Patients have access to 950 providers within the network, including primary and specialty care sites of service, urgent care locations, surgery centers, and Phoenix Children’s Hospital.

Meanwhile, 2,000 miles away, another unique payment model is changing the way pediatric care is delivered in the Columbus, Ohio area. Partners For Kids (PFK) is a pediatric accountable care organization (ACO) that coordinates care between Nationwide Children’s Hospital and more than 1,000 doctors. Through its 20-year evolution, PFK has successfully assumed full financial and clinical risk for children under age 19 enrolled in Medicaid managed care. This means PFK is responsible for paying for the costs of all patient care, no matter how much or where that care occurs.

The two models illustrate how pediatricians are affiliating with value-centric networks while keeping their independence, said Timothy Johnson, senior vice president of pediatrics at Valence Health, a consulting firm that helps health providers transition to value-based care.

With MACRA (the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015) “it’s going to be difficult for individual pediatricians to do what is required in a value-based medical system because they just don’t have the resources,” Mr. Johnson said in an interview. “That doesn’t mean they can’t be independent. It means they are going to have to band together in some way, whether with a health system, with other practices. It is extremely important for pediatricians to start thinking about how to do that.”

Going from splintered to unified

Like most communities, care delivery in the Phoenix area was relatively fractured prior to 2014. To bring everyone together, Phoenix Children’s started with community outreach and education.

Along with building trust among providers, project leaders had to overcome operational hurdles. This included creating a process for 110 practices to collectively negotiate contracts, operate under a new structure, and adhere to quality metrics, he said.

“Operationally, you have to take 110 different ways of doing things and try merge them into one common way as you develop these new contractual risk-based models,” he said. “At the same time, we had to transition people away from what they were used to as a purely fee-for-service model. It was a very big operational transition.”

To bolster engagement by community pediatricians, PCCN developed a physician-governance approach, assigning participating providers leadership responsibilities. Participating physicians then worked to create the benchmarks by which doctors are measured against. To date, provider performance is tracked against 14 primary care and 34 specialist metrics encompassing engagement, safety, quality, and transparency.

PCCN leaders also had to ensure that participating in such a network was beneficial for busy doctors, said Dr. Vargas, who is chair of the PCCN Network and Utilization committee and a member of the network’s board of managers.

Asking physicians to change their framework, track patient data, and meet metrics, all while potentially losing money if they fail to hit benchmarks is not the most popular proposition, he said. So PCCN created advantages for member doctors, such as nighttime pediatric triage, a negotiated discount for professional services, IT support, streamlined access to specialists, and more avenues to communicate with subspecialists.

“With so many schedules, professional, and academic pressures on our daily professional lives, we have wanted to make sure that there were practical value added benefits to members,” he said. “I think right now that the benefits outweigh the administrative burdens.”

A changing payer relationship

As a network, PCCN works with payers to assume the risk that insurers have historically taken. Payers continue to handle the administrative and billing side of the equation, while the network controls the medical management and care coordination of the patient population, Mr. Johnson said.

“We feel we can do it much more efficiently, much more effectively, and we feel it’s better care for the patient when we’re the one controlling that,” he said. “The insurance companies don’t disagree.”

The network partners with Medicaid and commercial payers and has a direct-to-employer agreement with a major employer in conjunction with an adult partner system/network. Early performance efforts by the PCCN have been rewarded by shared savings disbursements from two payers, according to PCCN officials. The network has also met or exceeded state Medicaid pediatric quality targets and consistently contained medical expenses below expected medical cost trends for its managed pediatric populations.

Building a population health model

For more than 2 decades, PFK in Ohio has taken a novel care delivery approach that has focused on value and community partnerships.

Back in 1994, Nationwide Children’s Hospital partnered with community pediatricians to create PFK, a physician/hospital organization with governance shared equally. Today, PFK has assumed full financial and clinical risk for pediatric managed Medicaid enrollees, and is the largest and oldest known pediatric ACO.

A key hurdle was collecting timely, complete, and accurate data for the patient population, Dr. Gleeson said, adding that working with data and understanding changing trends is an everyday challenge. Interacting with busy physicians and securing their time and cooperation also has been an obstacle.

“The lessons learned for us is that we really need to approach them understanding that there is a limited amount of time that practices can invest in infrastructure or invest in the processes of care,” he said. “We have to approach things knowing that [doctors] are going to struggle with the amount of time necessary to engage in large projects, so it needs to be chopped up into bite-sized pieces that they can consume on the run, so they can keep their practices running well.”

PFK efforts have paid off in terms of lowering costs and improving care. Between 2008 and 2013, PFK achieved lower cost growth than Medicaid fee-for-service programs and managed care plans in the Columbus, Ohio, area (Pediatrics. 2015 Mar;135[3];e582-9).

Fundamentally, the model has remained the same over the years, Dr. Gleeson said, but in 2005, PFK made the decision to expand and take responsibility for all the Medicaid-enrolled children in the region.

“It really gives a much broader field of view and perspective on patients in the region,” he said. “We know that they are all our responsibility so we take more of a population health type of approach, working with any physician who is caring for those children.”

Guidance for other practices

Dr. Gleeson encouraged other pediatricians interested in transitioning to value-based care to start by evaluating their data. Take a hard look at the quality of care you provide and begin to measure it, he said. For smaller practices, consider joining a larger group or network that will allow pediatricians to engage in collaborative work, he added.

Dr. Vargas stressed that change is coming whether pediatricians are prepared or not. Aligning with the right partners will be the difference between sinking or staying afloat in the value-based landscape.

“Payers are moving toward value-based models and it is not practical for the general pediatrician to be able to provide the infrastructure and professional resources necessary,” he said. “To maintain our professional livelihood as independent pediatricians, and to continue to provide the individually crafted, quality care our families are accustomed to, we will have to align ourselves with organizations that value the experience and insight of the independent pediatrician to deliver that care.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

When Jason Vargas, MD, first moved to the Phoenix area 13 years ago, he found an atmosphere of distant relationships between general pediatricians like him, subspecialists, and hospitals. Getting patients a referral to a subspecialist could take months, and communication among providers was often weak, Dr. Vargas said.

Today, things are vastly different thanks in large part to the clinically integrated network of which Dr. Vargas and 950 area providers are a part.

Phoenix Children’s Care Network (PCCN), established in 2014, coordinates health care across multiple providers and settings in the Phoenix area, including half of all general pediatricians and 80% of pediatric subspecialists practicing in Maricopa County. The network is a value- and risk-based system that provides financial incentives to participating providers and health systems that meet established quality metrics. Patients have access to 950 providers within the network, including primary and specialty care sites of service, urgent care locations, surgery centers, and Phoenix Children’s Hospital.

Meanwhile, 2,000 miles away, another unique payment model is changing the way pediatric care is delivered in the Columbus, Ohio area. Partners For Kids (PFK) is a pediatric accountable care organization (ACO) that coordinates care between Nationwide Children’s Hospital and more than 1,000 doctors. Through its 20-year evolution, PFK has successfully assumed full financial and clinical risk for children under age 19 enrolled in Medicaid managed care. This means PFK is responsible for paying for the costs of all patient care, no matter how much or where that care occurs.

The two models illustrate how pediatricians are affiliating with value-centric networks while keeping their independence, said Timothy Johnson, senior vice president of pediatrics at Valence Health, a consulting firm that helps health providers transition to value-based care.

With MACRA (the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015) “it’s going to be difficult for individual pediatricians to do what is required in a value-based medical system because they just don’t have the resources,” Mr. Johnson said in an interview. “That doesn’t mean they can’t be independent. It means they are going to have to band together in some way, whether with a health system, with other practices. It is extremely important for pediatricians to start thinking about how to do that.”

Going from splintered to unified

Like most communities, care delivery in the Phoenix area was relatively fractured prior to 2014. To bring everyone together, Phoenix Children’s started with community outreach and education.

Along with building trust among providers, project leaders had to overcome operational hurdles. This included creating a process for 110 practices to collectively negotiate contracts, operate under a new structure, and adhere to quality metrics, he said.

“Operationally, you have to take 110 different ways of doing things and try merge them into one common way as you develop these new contractual risk-based models,” he said. “At the same time, we had to transition people away from what they were used to as a purely fee-for-service model. It was a very big operational transition.”

To bolster engagement by community pediatricians, PCCN developed a physician-governance approach, assigning participating providers leadership responsibilities. Participating physicians then worked to create the benchmarks by which doctors are measured against. To date, provider performance is tracked against 14 primary care and 34 specialist metrics encompassing engagement, safety, quality, and transparency.

PCCN leaders also had to ensure that participating in such a network was beneficial for busy doctors, said Dr. Vargas, who is chair of the PCCN Network and Utilization committee and a member of the network’s board of managers.

Asking physicians to change their framework, track patient data, and meet metrics, all while potentially losing money if they fail to hit benchmarks is not the most popular proposition, he said. So PCCN created advantages for member doctors, such as nighttime pediatric triage, a negotiated discount for professional services, IT support, streamlined access to specialists, and more avenues to communicate with subspecialists.

“With so many schedules, professional, and academic pressures on our daily professional lives, we have wanted to make sure that there were practical value added benefits to members,” he said. “I think right now that the benefits outweigh the administrative burdens.”

A changing payer relationship

As a network, PCCN works with payers to assume the risk that insurers have historically taken. Payers continue to handle the administrative and billing side of the equation, while the network controls the medical management and care coordination of the patient population, Mr. Johnson said.

“We feel we can do it much more efficiently, much more effectively, and we feel it’s better care for the patient when we’re the one controlling that,” he said. “The insurance companies don’t disagree.”

The network partners with Medicaid and commercial payers and has a direct-to-employer agreement with a major employer in conjunction with an adult partner system/network. Early performance efforts by the PCCN have been rewarded by shared savings disbursements from two payers, according to PCCN officials. The network has also met or exceeded state Medicaid pediatric quality targets and consistently contained medical expenses below expected medical cost trends for its managed pediatric populations.

Building a population health model

For more than 2 decades, PFK in Ohio has taken a novel care delivery approach that has focused on value and community partnerships.

Back in 1994, Nationwide Children’s Hospital partnered with community pediatricians to create PFK, a physician/hospital organization with governance shared equally. Today, PFK has assumed full financial and clinical risk for pediatric managed Medicaid enrollees, and is the largest and oldest known pediatric ACO.

A key hurdle was collecting timely, complete, and accurate data for the patient population, Dr. Gleeson said, adding that working with data and understanding changing trends is an everyday challenge. Interacting with busy physicians and securing their time and cooperation also has been an obstacle.

“The lessons learned for us is that we really need to approach them understanding that there is a limited amount of time that practices can invest in infrastructure or invest in the processes of care,” he said. “We have to approach things knowing that [doctors] are going to struggle with the amount of time necessary to engage in large projects, so it needs to be chopped up into bite-sized pieces that they can consume on the run, so they can keep their practices running well.”

PFK efforts have paid off in terms of lowering costs and improving care. Between 2008 and 2013, PFK achieved lower cost growth than Medicaid fee-for-service programs and managed care plans in the Columbus, Ohio, area (Pediatrics. 2015 Mar;135[3];e582-9).

Fundamentally, the model has remained the same over the years, Dr. Gleeson said, but in 2005, PFK made the decision to expand and take responsibility for all the Medicaid-enrolled children in the region.

“It really gives a much broader field of view and perspective on patients in the region,” he said. “We know that they are all our responsibility so we take more of a population health type of approach, working with any physician who is caring for those children.”

Guidance for other practices

Dr. Gleeson encouraged other pediatricians interested in transitioning to value-based care to start by evaluating their data. Take a hard look at the quality of care you provide and begin to measure it, he said. For smaller practices, consider joining a larger group or network that will allow pediatricians to engage in collaborative work, he added.

Dr. Vargas stressed that change is coming whether pediatricians are prepared or not. Aligning with the right partners will be the difference between sinking or staying afloat in the value-based landscape.

“Payers are moving toward value-based models and it is not practical for the general pediatrician to be able to provide the infrastructure and professional resources necessary,” he said. “To maintain our professional livelihood as independent pediatricians, and to continue to provide the individually crafted, quality care our families are accustomed to, we will have to align ourselves with organizations that value the experience and insight of the independent pediatrician to deliver that care.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

GAO report calls out HHS for misdirecting ACA reinsurance funds

The Health and Human Services department is failing to properly administer a reinsurance program under the Affordable Care Act by unlawfully diverting funds intended for the U.S. Treasury, according to a nonpartisan watchdog report.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) report, released Sept. 29, finds that HHS is breaking ACA regulations that require a portion of funds collected under its Transitional Reinsurance Program to go to the Treasury. Instead, the agency has redirected $5 billion so far to pay health insurers that enroll high-cost patients under the program.

“In light of the foregoing analysis, we conclude that HHS lacks authority to ignore the statute’s directive to deposit amounts from collections under the Transitional Reinsurance Program to the Treasury and instead make deposits in the Treasury only if its collections reach the amounts for reinsurance payments specified in section 1341,” Susan A. Poling, GAO general counsel, wrote in a legal opinion. “The agency is not authorized to prioritize collections in this manner.”

Republican lawmakers, including Sen. John Barrasso III (Wyo.), chair of the Senate Republican Policy Committee, praised the legal opinion, saying it shows the Obama administration is bending the rules when it comes to rolling out the ACA.

“This is a major victory for the American people who are suffering with higher premiums and fewer choices because of this failed law,” said Sen. Barrasso, who with several fellow Republican legislators requested the GAO investigation. “The administration should end this illegal scheme immediately, and focus on providing relief from the burdens of this law.”

At press time, neither the White House nor HHS had responded to request for comment on the report.

The Transitional Reinsurance Program is a 3-year initiative under the ACA that collects fees from employers and other private health insurance plans and directs the funds to health plans that face large claims for patients with high-cost medical conditions. The ACA specifies that between 2014 and 2016, HHS would collect $25 billion in fees, of which $5 billion would go into the Treasury.

But when HHS was unable to collect the full amount over the 3 years, it did not distribute funds into the Treasury, but instead used it pay the health plans. To justify that decision, HHS officials announced that the department would allocate all collections first for reinsurance payments until collections totaled the target amount set forth for reinsurance payments under the law, and that any remaining collections would go toward to administrative expenses and the Treasury, according to the GAO report.

But the GAO argues that HHS falling short of the projected collections does not alter the meaning of the statute.

“Specifically, where actual funding has fallen short of an agency’s original expectations, courts have directed the agency to distribute available funds to approximate the allocation plan Congress designed in anticipation of full funding,” Ms. Poling wrote. The HHS “assertion that the statute is silent with respect to allocation of collections overlooks the fact that section 1341 expressly directs HHS to collect amounts for the Treasury and prohibits the use of these amounts for any purpose other than deposit in the Treasury. HHS’s analysis focuses on words and phrases in the statute in isolation rather than in their appropriate context.”

While the GAO cannot force HHS to act with the opinion, lawmakers could use the report to craft legislation forcing HHS to repay the Treasury.

“This issue has been brewing for a while, and is another example of a series of attempts to challenge or limit payments being made to carriers under the ACA,” Katherine Hempstead, senior adviser to vice president at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, said in an interview. “It’s no mystery why making these payments is a pretty high priority for the [Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services] right now, given the losses sustained by many market participants. My guess is that the can will probably be kicked down the road on this and a number of other issues for the next administration and Congress to resolve.”

The reinsurance program was one of three programs intended to protect against the negative impacts of adverse selection and risk selection, while working to stabilize premiums during the initial years of the health law’s implementation. The program aims to protect against premium increases in the individual market by offsetting expenses of high-cost patients.

On Twitter @legal_med

The Health and Human Services department is failing to properly administer a reinsurance program under the Affordable Care Act by unlawfully diverting funds intended for the U.S. Treasury, according to a nonpartisan watchdog report.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) report, released Sept. 29, finds that HHS is breaking ACA regulations that require a portion of funds collected under its Transitional Reinsurance Program to go to the Treasury. Instead, the agency has redirected $5 billion so far to pay health insurers that enroll high-cost patients under the program.

“In light of the foregoing analysis, we conclude that HHS lacks authority to ignore the statute’s directive to deposit amounts from collections under the Transitional Reinsurance Program to the Treasury and instead make deposits in the Treasury only if its collections reach the amounts for reinsurance payments specified in section 1341,” Susan A. Poling, GAO general counsel, wrote in a legal opinion. “The agency is not authorized to prioritize collections in this manner.”

Republican lawmakers, including Sen. John Barrasso III (Wyo.), chair of the Senate Republican Policy Committee, praised the legal opinion, saying it shows the Obama administration is bending the rules when it comes to rolling out the ACA.

“This is a major victory for the American people who are suffering with higher premiums and fewer choices because of this failed law,” said Sen. Barrasso, who with several fellow Republican legislators requested the GAO investigation. “The administration should end this illegal scheme immediately, and focus on providing relief from the burdens of this law.”

At press time, neither the White House nor HHS had responded to request for comment on the report.

The Transitional Reinsurance Program is a 3-year initiative under the ACA that collects fees from employers and other private health insurance plans and directs the funds to health plans that face large claims for patients with high-cost medical conditions. The ACA specifies that between 2014 and 2016, HHS would collect $25 billion in fees, of which $5 billion would go into the Treasury.

But when HHS was unable to collect the full amount over the 3 years, it did not distribute funds into the Treasury, but instead used it pay the health plans. To justify that decision, HHS officials announced that the department would allocate all collections first for reinsurance payments until collections totaled the target amount set forth for reinsurance payments under the law, and that any remaining collections would go toward to administrative expenses and the Treasury, according to the GAO report.

But the GAO argues that HHS falling short of the projected collections does not alter the meaning of the statute.

“Specifically, where actual funding has fallen short of an agency’s original expectations, courts have directed the agency to distribute available funds to approximate the allocation plan Congress designed in anticipation of full funding,” Ms. Poling wrote. The HHS “assertion that the statute is silent with respect to allocation of collections overlooks the fact that section 1341 expressly directs HHS to collect amounts for the Treasury and prohibits the use of these amounts for any purpose other than deposit in the Treasury. HHS’s analysis focuses on words and phrases in the statute in isolation rather than in their appropriate context.”

While the GAO cannot force HHS to act with the opinion, lawmakers could use the report to craft legislation forcing HHS to repay the Treasury.

“This issue has been brewing for a while, and is another example of a series of attempts to challenge or limit payments being made to carriers under the ACA,” Katherine Hempstead, senior adviser to vice president at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, said in an interview. “It’s no mystery why making these payments is a pretty high priority for the [Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services] right now, given the losses sustained by many market participants. My guess is that the can will probably be kicked down the road on this and a number of other issues for the next administration and Congress to resolve.”

The reinsurance program was one of three programs intended to protect against the negative impacts of adverse selection and risk selection, while working to stabilize premiums during the initial years of the health law’s implementation. The program aims to protect against premium increases in the individual market by offsetting expenses of high-cost patients.

On Twitter @legal_med

The Health and Human Services department is failing to properly administer a reinsurance program under the Affordable Care Act by unlawfully diverting funds intended for the U.S. Treasury, according to a nonpartisan watchdog report.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) report, released Sept. 29, finds that HHS is breaking ACA regulations that require a portion of funds collected under its Transitional Reinsurance Program to go to the Treasury. Instead, the agency has redirected $5 billion so far to pay health insurers that enroll high-cost patients under the program.

“In light of the foregoing analysis, we conclude that HHS lacks authority to ignore the statute’s directive to deposit amounts from collections under the Transitional Reinsurance Program to the Treasury and instead make deposits in the Treasury only if its collections reach the amounts for reinsurance payments specified in section 1341,” Susan A. Poling, GAO general counsel, wrote in a legal opinion. “The agency is not authorized to prioritize collections in this manner.”

Republican lawmakers, including Sen. John Barrasso III (Wyo.), chair of the Senate Republican Policy Committee, praised the legal opinion, saying it shows the Obama administration is bending the rules when it comes to rolling out the ACA.

“This is a major victory for the American people who are suffering with higher premiums and fewer choices because of this failed law,” said Sen. Barrasso, who with several fellow Republican legislators requested the GAO investigation. “The administration should end this illegal scheme immediately, and focus on providing relief from the burdens of this law.”

At press time, neither the White House nor HHS had responded to request for comment on the report.

The Transitional Reinsurance Program is a 3-year initiative under the ACA that collects fees from employers and other private health insurance plans and directs the funds to health plans that face large claims for patients with high-cost medical conditions. The ACA specifies that between 2014 and 2016, HHS would collect $25 billion in fees, of which $5 billion would go into the Treasury.

But when HHS was unable to collect the full amount over the 3 years, it did not distribute funds into the Treasury, but instead used it pay the health plans. To justify that decision, HHS officials announced that the department would allocate all collections first for reinsurance payments until collections totaled the target amount set forth for reinsurance payments under the law, and that any remaining collections would go toward to administrative expenses and the Treasury, according to the GAO report.

But the GAO argues that HHS falling short of the projected collections does not alter the meaning of the statute.

“Specifically, where actual funding has fallen short of an agency’s original expectations, courts have directed the agency to distribute available funds to approximate the allocation plan Congress designed in anticipation of full funding,” Ms. Poling wrote. The HHS “assertion that the statute is silent with respect to allocation of collections overlooks the fact that section 1341 expressly directs HHS to collect amounts for the Treasury and prohibits the use of these amounts for any purpose other than deposit in the Treasury. HHS’s analysis focuses on words and phrases in the statute in isolation rather than in their appropriate context.”

While the GAO cannot force HHS to act with the opinion, lawmakers could use the report to craft legislation forcing HHS to repay the Treasury.

“This issue has been brewing for a while, and is another example of a series of attempts to challenge or limit payments being made to carriers under the ACA,” Katherine Hempstead, senior adviser to vice president at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, said in an interview. “It’s no mystery why making these payments is a pretty high priority for the [Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services] right now, given the losses sustained by many market participants. My guess is that the can will probably be kicked down the road on this and a number of other issues for the next administration and Congress to resolve.”

The reinsurance program was one of three programs intended to protect against the negative impacts of adverse selection and risk selection, while working to stabilize premiums during the initial years of the health law’s implementation. The program aims to protect against premium increases in the individual market by offsetting expenses of high-cost patients.

On Twitter @legal_med

Congress sends Zika funding bill to President

In a move that narrowly avoids a government shutdown, Congress has passed a long-awaited bill that keeps the government afloat and provides $1.1 billion in funding to combat the Zika virus.

The House cleared H.R. 5325 late Sept. 28 by a 342-85 tally, following a 72-26 vote by the Senate earlier in the day. The final package, which keeps the government operating through Dec. 9, also includes $37 million for opioid addiction and $500 million for flooding in Louisiana. The White House has indicated that President Obama will sign the bill into law.

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists praised Congress for passing the long-delayed comprehensive Zika funding package.

“Congress has finally treated Zika like the emergency it is and shown the American people that it is capable of rising above partisanship for the health of its citizens,” Thomas Gellhaus, MD, ACOG president, said in a statement. “ACOG stands with peer organizations and government agencies in the fight to prevent and respond to the Zika virus and support the care and treatment of all people affected by it. ... The fight against the spread of Zika cannot be won without the resources to support responsive and proactive solutions. This comprehensive funding package is essential to our success and the health of women and babies.”

The bill’s passage caps months of fiery debate within Congress over what to include in the measure. The bill stalled earlier this week largely over whether to direct funds to Flint, Mich., to deal with the crisis over lead-tainted water. Leaders agreed to provide aid to Flint residents in a separate water projects bill. Legislators will address final approval of the Flint measure in December.

Of the $1.1 billion included in the final package to fight Zika, $15 million would go to Florida and $60 million to the territory of Puerto Rico to respond to Zika outbreaks in those areas. The remainder of the funding would be used to prevent, prepare for, and respond to Zika; health conditions related to such virus; and other vector-borne diseases, domestically and internationally.

If signed by the President, the money would also go toward developing necessary countermeasures and vaccines, including the development and purchase of vaccines, therapeutics, diagnostics, and necessary medical supplies. Additionally, the funding would aid research on the virology, natural history, and pathogenesis of the Zika virus infection and preclinical and clinical development of vaccines and other medical countermeasures for the Zika virus.

The American Medical Association expressed relief that Congress had finally taken action to provide resources for fighting Zika.

“It has been clear over the past several months that the U.S. has needed additional resources to combat the Zika virus,” AMA president Andrew W. Gurman, MD, said in a statement. “With the threat of the virus continuing to loom, this funding will help protect more people – particularly pregnant women and their children – from the virus’s lasting negative health effects.”

On Twitter @legal_med

In a move that narrowly avoids a government shutdown, Congress has passed a long-awaited bill that keeps the government afloat and provides $1.1 billion in funding to combat the Zika virus.

The House cleared H.R. 5325 late Sept. 28 by a 342-85 tally, following a 72-26 vote by the Senate earlier in the day. The final package, which keeps the government operating through Dec. 9, also includes $37 million for opioid addiction and $500 million for flooding in Louisiana. The White House has indicated that President Obama will sign the bill into law.

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists praised Congress for passing the long-delayed comprehensive Zika funding package.

“Congress has finally treated Zika like the emergency it is and shown the American people that it is capable of rising above partisanship for the health of its citizens,” Thomas Gellhaus, MD, ACOG president, said in a statement. “ACOG stands with peer organizations and government agencies in the fight to prevent and respond to the Zika virus and support the care and treatment of all people affected by it. ... The fight against the spread of Zika cannot be won without the resources to support responsive and proactive solutions. This comprehensive funding package is essential to our success and the health of women and babies.”

The bill’s passage caps months of fiery debate within Congress over what to include in the measure. The bill stalled earlier this week largely over whether to direct funds to Flint, Mich., to deal with the crisis over lead-tainted water. Leaders agreed to provide aid to Flint residents in a separate water projects bill. Legislators will address final approval of the Flint measure in December.

Of the $1.1 billion included in the final package to fight Zika, $15 million would go to Florida and $60 million to the territory of Puerto Rico to respond to Zika outbreaks in those areas. The remainder of the funding would be used to prevent, prepare for, and respond to Zika; health conditions related to such virus; and other vector-borne diseases, domestically and internationally.

If signed by the President, the money would also go toward developing necessary countermeasures and vaccines, including the development and purchase of vaccines, therapeutics, diagnostics, and necessary medical supplies. Additionally, the funding would aid research on the virology, natural history, and pathogenesis of the Zika virus infection and preclinical and clinical development of vaccines and other medical countermeasures for the Zika virus.

The American Medical Association expressed relief that Congress had finally taken action to provide resources for fighting Zika.

“It has been clear over the past several months that the U.S. has needed additional resources to combat the Zika virus,” AMA president Andrew W. Gurman, MD, said in a statement. “With the threat of the virus continuing to loom, this funding will help protect more people – particularly pregnant women and their children – from the virus’s lasting negative health effects.”

On Twitter @legal_med

In a move that narrowly avoids a government shutdown, Congress has passed a long-awaited bill that keeps the government afloat and provides $1.1 billion in funding to combat the Zika virus.

The House cleared H.R. 5325 late Sept. 28 by a 342-85 tally, following a 72-26 vote by the Senate earlier in the day. The final package, which keeps the government operating through Dec. 9, also includes $37 million for opioid addiction and $500 million for flooding in Louisiana. The White House has indicated that President Obama will sign the bill into law.

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists praised Congress for passing the long-delayed comprehensive Zika funding package.

“Congress has finally treated Zika like the emergency it is and shown the American people that it is capable of rising above partisanship for the health of its citizens,” Thomas Gellhaus, MD, ACOG president, said in a statement. “ACOG stands with peer organizations and government agencies in the fight to prevent and respond to the Zika virus and support the care and treatment of all people affected by it. ... The fight against the spread of Zika cannot be won without the resources to support responsive and proactive solutions. This comprehensive funding package is essential to our success and the health of women and babies.”

The bill’s passage caps months of fiery debate within Congress over what to include in the measure. The bill stalled earlier this week largely over whether to direct funds to Flint, Mich., to deal with the crisis over lead-tainted water. Leaders agreed to provide aid to Flint residents in a separate water projects bill. Legislators will address final approval of the Flint measure in December.

Of the $1.1 billion included in the final package to fight Zika, $15 million would go to Florida and $60 million to the territory of Puerto Rico to respond to Zika outbreaks in those areas. The remainder of the funding would be used to prevent, prepare for, and respond to Zika; health conditions related to such virus; and other vector-borne diseases, domestically and internationally.

If signed by the President, the money would also go toward developing necessary countermeasures and vaccines, including the development and purchase of vaccines, therapeutics, diagnostics, and necessary medical supplies. Additionally, the funding would aid research on the virology, natural history, and pathogenesis of the Zika virus infection and preclinical and clinical development of vaccines and other medical countermeasures for the Zika virus.

The American Medical Association expressed relief that Congress had finally taken action to provide resources for fighting Zika.

“It has been clear over the past several months that the U.S. has needed additional resources to combat the Zika virus,” AMA president Andrew W. Gurman, MD, said in a statement. “With the threat of the virus continuing to loom, this funding will help protect more people – particularly pregnant women and their children – from the virus’s lasting negative health effects.”

On Twitter @legal_med

CMS: Bundled payment initiative shows savings

The majority of clinical episode groups participating in the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement initiative are generating Medicare savings, according to a CMS analysis.

The study showed that orthopedic surgery under Model 2 generated savings of $864 per episode, while improving postdischarge outcomes. Cardiovascular surgery episodes under Model 2 did not show any savings, but quality of care was preserved, according to the analysis. In total, 11 out of the 15 clinical episode groups analyzed showed potential savings to Medicare.

“While there is more work to be done, CMS continues to move forward to achieving the administration’s goal to have 50% of traditional Medicare payments tied to alternative payment models by 2018,” Patrick Conway, MD, CMS acting principal deputy administrator and chief medical officer wrote in a blog post. “Bundled payments continue to be an integral part of transforming our health care system by creating innovative care delivery models that support hospitals, doctors, and other providers in their efforts to deliver better care for patients while spending taxpayer dollars more wisely.”

The Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative was designed to test whether linking payments for all providers involved in an episode of care reduces Medicare costs, while maintaining or improving quality of care. To participate, BPCI awardees – which include hospitals, physician groups, post-acute care (PAC) providers, and other entities – enter into agreements with the CMS that hold them accountable for total Medicare episode payments. Such agreements specify choices among four payment models, 48 clinical episodes, three episode lengths, and waiver options.

From October 2013 through September 2014, the first full year of the initiative, 94 awardees, including hospitals, physician groups, and post–acute care providers, entered into agreements with the CMS to be held accountable for total Medicare episode payments. Under the initiative, nearly 60,000 episodes of care were initiated, according to the CMS. BPCI-participating providers tended to be larger, operate in more affluent urban areas, and have higher episode costs than providers who did not participate.

An analysis of Model 2 showed that:

• Average standardized Medicare payments for hospitalization and 90 days post discharge were estimated to have declined by $864 per orthopedic surgery episode at BPCI-participating hospitals, compared with nonparticipating hospitals.

• For cardiovascular surgery, there was no statistically significant difference in Medicare payments for the index hospitalization and the 90-day post discharge period between the BPCI and comparison episodes.

• For cardiovascular surgery, there were no statistically significant changes in hospital readmissions within the 30 or 90 days post discharge, or any of the assessment-based quality measures between the BPCI and comparison populations.

For most clinical episode groups in Model 3, there were no statistically significant differences between BPCI and comparison episodes from the baseline to the intervention period in total Medicare standardized allowed payments during the qualifying inpatient stay and 90-day postdischarge period or in quality measures, the analysis found.

Over the next year, the CMS plans to have significantly more data available on the initiative, enabling the agency to better estimate effects on costs and quality, according to Dr. Conway. Future evaluation reports are expected to have greater ability to detect changes in payment and quality because of larger sample sizes and the recent growth in participation in the initiative.

On Twitter @legal_med

The majority of clinical episode groups participating in the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement initiative are generating Medicare savings, according to a CMS analysis.

The study showed that orthopedic surgery under Model 2 generated savings of $864 per episode, while improving postdischarge outcomes. Cardiovascular surgery episodes under Model 2 did not show any savings, but quality of care was preserved, according to the analysis. In total, 11 out of the 15 clinical episode groups analyzed showed potential savings to Medicare.

“While there is more work to be done, CMS continues to move forward to achieving the administration’s goal to have 50% of traditional Medicare payments tied to alternative payment models by 2018,” Patrick Conway, MD, CMS acting principal deputy administrator and chief medical officer wrote in a blog post. “Bundled payments continue to be an integral part of transforming our health care system by creating innovative care delivery models that support hospitals, doctors, and other providers in their efforts to deliver better care for patients while spending taxpayer dollars more wisely.”

The Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative was designed to test whether linking payments for all providers involved in an episode of care reduces Medicare costs, while maintaining or improving quality of care. To participate, BPCI awardees – which include hospitals, physician groups, post-acute care (PAC) providers, and other entities – enter into agreements with the CMS that hold them accountable for total Medicare episode payments. Such agreements specify choices among four payment models, 48 clinical episodes, three episode lengths, and waiver options.

From October 2013 through September 2014, the first full year of the initiative, 94 awardees, including hospitals, physician groups, and post–acute care providers, entered into agreements with the CMS to be held accountable for total Medicare episode payments. Under the initiative, nearly 60,000 episodes of care were initiated, according to the CMS. BPCI-participating providers tended to be larger, operate in more affluent urban areas, and have higher episode costs than providers who did not participate.

An analysis of Model 2 showed that:

• Average standardized Medicare payments for hospitalization and 90 days post discharge were estimated to have declined by $864 per orthopedic surgery episode at BPCI-participating hospitals, compared with nonparticipating hospitals.

• For cardiovascular surgery, there was no statistically significant difference in Medicare payments for the index hospitalization and the 90-day post discharge period between the BPCI and comparison episodes.

• For cardiovascular surgery, there were no statistically significant changes in hospital readmissions within the 30 or 90 days post discharge, or any of the assessment-based quality measures between the BPCI and comparison populations.

For most clinical episode groups in Model 3, there were no statistically significant differences between BPCI and comparison episodes from the baseline to the intervention period in total Medicare standardized allowed payments during the qualifying inpatient stay and 90-day postdischarge period or in quality measures, the analysis found.

Over the next year, the CMS plans to have significantly more data available on the initiative, enabling the agency to better estimate effects on costs and quality, according to Dr. Conway. Future evaluation reports are expected to have greater ability to detect changes in payment and quality because of larger sample sizes and the recent growth in participation in the initiative.

On Twitter @legal_med

The majority of clinical episode groups participating in the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement initiative are generating Medicare savings, according to a CMS analysis.

The study showed that orthopedic surgery under Model 2 generated savings of $864 per episode, while improving postdischarge outcomes. Cardiovascular surgery episodes under Model 2 did not show any savings, but quality of care was preserved, according to the analysis. In total, 11 out of the 15 clinical episode groups analyzed showed potential savings to Medicare.

“While there is more work to be done, CMS continues to move forward to achieving the administration’s goal to have 50% of traditional Medicare payments tied to alternative payment models by 2018,” Patrick Conway, MD, CMS acting principal deputy administrator and chief medical officer wrote in a blog post. “Bundled payments continue to be an integral part of transforming our health care system by creating innovative care delivery models that support hospitals, doctors, and other providers in their efforts to deliver better care for patients while spending taxpayer dollars more wisely.”

The Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative was designed to test whether linking payments for all providers involved in an episode of care reduces Medicare costs, while maintaining or improving quality of care. To participate, BPCI awardees – which include hospitals, physician groups, post-acute care (PAC) providers, and other entities – enter into agreements with the CMS that hold them accountable for total Medicare episode payments. Such agreements specify choices among four payment models, 48 clinical episodes, three episode lengths, and waiver options.

From October 2013 through September 2014, the first full year of the initiative, 94 awardees, including hospitals, physician groups, and post–acute care providers, entered into agreements with the CMS to be held accountable for total Medicare episode payments. Under the initiative, nearly 60,000 episodes of care were initiated, according to the CMS. BPCI-participating providers tended to be larger, operate in more affluent urban areas, and have higher episode costs than providers who did not participate.

An analysis of Model 2 showed that:

• Average standardized Medicare payments for hospitalization and 90 days post discharge were estimated to have declined by $864 per orthopedic surgery episode at BPCI-participating hospitals, compared with nonparticipating hospitals.

• For cardiovascular surgery, there was no statistically significant difference in Medicare payments for the index hospitalization and the 90-day post discharge period between the BPCI and comparison episodes.

• For cardiovascular surgery, there were no statistically significant changes in hospital readmissions within the 30 or 90 days post discharge, or any of the assessment-based quality measures between the BPCI and comparison populations.

For most clinical episode groups in Model 3, there were no statistically significant differences between BPCI and comparison episodes from the baseline to the intervention period in total Medicare standardized allowed payments during the qualifying inpatient stay and 90-day postdischarge period or in quality measures, the analysis found.

Over the next year, the CMS plans to have significantly more data available on the initiative, enabling the agency to better estimate effects on costs and quality, according to Dr. Conway. Future evaluation reports are expected to have greater ability to detect changes in payment and quality because of larger sample sizes and the recent growth in participation in the initiative.

On Twitter @legal_med

Legislators: Investigate Medicare fraud before paying doctors

Republican leaders in Congress are calling on CMS to impose stricter safeguards against fraudulent Medicare billing by physicians.

The chairmen of the Senate Finance Committee, the House Ways and Means and Energy and Commerce Committees, and the chairmen of key House subcommittees said that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services relies too heavily on the “outdated” pay and chase method and should focus more energy on preventing payment for potential fraudulent claims.

“Improper payments remain an enormous problem for the Medicare program,” the chairmen wrote in a Sept. 12 letter to Acting CMS Administrator Andy Slavitt. “In 2015, the Medicare program had an error rate of 12.1% or $43.3 billion dollars. The billions of dollars lost to Medicare fraud each year underscore the importance of stopping potentially fraudulent payments before they’re made,”

Some health law experts, however, argue that CMS already has a process for in place for pre-identifying inaccurate claims via prepayment audits and reviews. Such efforts can be devastating for physicians who come under scrutiny for unintentional mistakes, said Daniel F. Shay, a Philadelphia health law attorney.

“I can understand why, particularly in an election year, elected officials might send a letter reiterating the need to curb ‘waste, fraud, and abuse,’” Mr. Shay said in an interview. “It’s true that it’s more efficient for the government to investigate a physician’s claim for reimbursement first, and then pay. However, I think we have to take into account the physicians’ perspective, especially physicians in smaller, independent practices.”

The legislators’ letter acknowledges that CMS has taken some proactive steps to prevent health fraud, including creation of the Fraud Prevention System (FPS), which highlights questionable billing patterns and identifies providers who pose high risk to the program. FPS runs analytics on 4.5 million claims daily and has led to more than $820 million in savings, according to CMS. However, legislators said they are still concerned that CMS too often pays claims before investigating whether they’re false. The letter requests that CMS clarify its implementation of the FPS program, including details on fraud investigations and how the agency monitors FPS’s effectiveness.

Houston, Tex.–based health law attorney Michael E. Clark disagrees that CMS is overusing the pay-and-chase method. Quite the contrary, he said.

“The federal government cannot seem to find the right balance on how to address program fraud,” Mr. Clark said in an interview. “While ‘pay and chase’ once was a problem, now the government can effectively destroy health care service providers under a very low threshold without the businesses having a meaningful right to appeal that determination.”

Specifically, CMS can withhold Medicare reimbursement from health providers under an amended 2011 law that permits payments to be suppressed when “credible” allegations of fraud have been made, but are disputed. The term “credible” is a new, lower standard for the administrative action, which was meant to address the pay-and-chase problem, Mr. Clark said. The law defines a “credible allegation of fraud” as an allegation from any source, including but not limited to fraud hotline complaints, data mining of claims, patterns identified through provider audits, civil false claims cases, and law enforcement investigations.

“That standard is easy to meet and agencies have every incentive to claim they’ve got so-called credible allegations of fraud in order to avoid being criticized later on for not preventing the monies from being dissipated,” he said. Because the law precludes health providers from appealing the fraud allegation to a federal court until all administrative remedies have been exhausted, “a health care services provider can quickly be put out of business, even if it turns out that the investigation proves not to be actionable.”

Prepayment reviews of claims can drag on for months, severely impacting a physician’s income, Mr. Shay added. In his experience, the majority of physicians under investigation are not trying to game the system, but rather don’t understand all of the administrative requirements related to filing claims. In some cases, the physicians’ notes are not complete, their bills are too high for services provided, or not enough documentation exists to support medical necessity.

“In the midst of that, you have doctors who are likely well-meaning, who have provided a service to a patient in need, and who are facing real economic hardship without an effective mechanism to challenge or end the prepayment review process,” he said.

Rather than more prepayment investigations, Mr. Shay would like to see CMS focus on physician education.

There needs to be “more emphasis on provider education in terms of compliance with program requirements,” he said. “It shouldn’t require a lawyer getting involved to find out what specifically [CMS] wants them to do. That should be part of the process as a standard.”

On Twitter @legal_med

Republican leaders in Congress are calling on CMS to impose stricter safeguards against fraudulent Medicare billing by physicians.

The chairmen of the Senate Finance Committee, the House Ways and Means and Energy and Commerce Committees, and the chairmen of key House subcommittees said that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services relies too heavily on the “outdated” pay and chase method and should focus more energy on preventing payment for potential fraudulent claims.

“Improper payments remain an enormous problem for the Medicare program,” the chairmen wrote in a Sept. 12 letter to Acting CMS Administrator Andy Slavitt. “In 2015, the Medicare program had an error rate of 12.1% or $43.3 billion dollars. The billions of dollars lost to Medicare fraud each year underscore the importance of stopping potentially fraudulent payments before they’re made,”

Some health law experts, however, argue that CMS already has a process for in place for pre-identifying inaccurate claims via prepayment audits and reviews. Such efforts can be devastating for physicians who come under scrutiny for unintentional mistakes, said Daniel F. Shay, a Philadelphia health law attorney.

“I can understand why, particularly in an election year, elected officials might send a letter reiterating the need to curb ‘waste, fraud, and abuse,’” Mr. Shay said in an interview. “It’s true that it’s more efficient for the government to investigate a physician’s claim for reimbursement first, and then pay. However, I think we have to take into account the physicians’ perspective, especially physicians in smaller, independent practices.”

The legislators’ letter acknowledges that CMS has taken some proactive steps to prevent health fraud, including creation of the Fraud Prevention System (FPS), which highlights questionable billing patterns and identifies providers who pose high risk to the program. FPS runs analytics on 4.5 million claims daily and has led to more than $820 million in savings, according to CMS. However, legislators said they are still concerned that CMS too often pays claims before investigating whether they’re false. The letter requests that CMS clarify its implementation of the FPS program, including details on fraud investigations and how the agency monitors FPS’s effectiveness.

Houston, Tex.–based health law attorney Michael E. Clark disagrees that CMS is overusing the pay-and-chase method. Quite the contrary, he said.

“The federal government cannot seem to find the right balance on how to address program fraud,” Mr. Clark said in an interview. “While ‘pay and chase’ once was a problem, now the government can effectively destroy health care service providers under a very low threshold without the businesses having a meaningful right to appeal that determination.”

Specifically, CMS can withhold Medicare reimbursement from health providers under an amended 2011 law that permits payments to be suppressed when “credible” allegations of fraud have been made, but are disputed. The term “credible” is a new, lower standard for the administrative action, which was meant to address the pay-and-chase problem, Mr. Clark said. The law defines a “credible allegation of fraud” as an allegation from any source, including but not limited to fraud hotline complaints, data mining of claims, patterns identified through provider audits, civil false claims cases, and law enforcement investigations.

“That standard is easy to meet and agencies have every incentive to claim they’ve got so-called credible allegations of fraud in order to avoid being criticized later on for not preventing the monies from being dissipated,” he said. Because the law precludes health providers from appealing the fraud allegation to a federal court until all administrative remedies have been exhausted, “a health care services provider can quickly be put out of business, even if it turns out that the investigation proves not to be actionable.”

Prepayment reviews of claims can drag on for months, severely impacting a physician’s income, Mr. Shay added. In his experience, the majority of physicians under investigation are not trying to game the system, but rather don’t understand all of the administrative requirements related to filing claims. In some cases, the physicians’ notes are not complete, their bills are too high for services provided, or not enough documentation exists to support medical necessity.

“In the midst of that, you have doctors who are likely well-meaning, who have provided a service to a patient in need, and who are facing real economic hardship without an effective mechanism to challenge or end the prepayment review process,” he said.

Rather than more prepayment investigations, Mr. Shay would like to see CMS focus on physician education.

There needs to be “more emphasis on provider education in terms of compliance with program requirements,” he said. “It shouldn’t require a lawyer getting involved to find out what specifically [CMS] wants them to do. That should be part of the process as a standard.”

On Twitter @legal_med

Republican leaders in Congress are calling on CMS to impose stricter safeguards against fraudulent Medicare billing by physicians.

The chairmen of the Senate Finance Committee, the House Ways and Means and Energy and Commerce Committees, and the chairmen of key House subcommittees said that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services relies too heavily on the “outdated” pay and chase method and should focus more energy on preventing payment for potential fraudulent claims.

“Improper payments remain an enormous problem for the Medicare program,” the chairmen wrote in a Sept. 12 letter to Acting CMS Administrator Andy Slavitt. “In 2015, the Medicare program had an error rate of 12.1% or $43.3 billion dollars. The billions of dollars lost to Medicare fraud each year underscore the importance of stopping potentially fraudulent payments before they’re made,”

Some health law experts, however, argue that CMS already has a process for in place for pre-identifying inaccurate claims via prepayment audits and reviews. Such efforts can be devastating for physicians who come under scrutiny for unintentional mistakes, said Daniel F. Shay, a Philadelphia health law attorney.

“I can understand why, particularly in an election year, elected officials might send a letter reiterating the need to curb ‘waste, fraud, and abuse,’” Mr. Shay said in an interview. “It’s true that it’s more efficient for the government to investigate a physician’s claim for reimbursement first, and then pay. However, I think we have to take into account the physicians’ perspective, especially physicians in smaller, independent practices.”

The legislators’ letter acknowledges that CMS has taken some proactive steps to prevent health fraud, including creation of the Fraud Prevention System (FPS), which highlights questionable billing patterns and identifies providers who pose high risk to the program. FPS runs analytics on 4.5 million claims daily and has led to more than $820 million in savings, according to CMS. However, legislators said they are still concerned that CMS too often pays claims before investigating whether they’re false. The letter requests that CMS clarify its implementation of the FPS program, including details on fraud investigations and how the agency monitors FPS’s effectiveness.

Houston, Tex.–based health law attorney Michael E. Clark disagrees that CMS is overusing the pay-and-chase method. Quite the contrary, he said.

“The federal government cannot seem to find the right balance on how to address program fraud,” Mr. Clark said in an interview. “While ‘pay and chase’ once was a problem, now the government can effectively destroy health care service providers under a very low threshold without the businesses having a meaningful right to appeal that determination.”

Specifically, CMS can withhold Medicare reimbursement from health providers under an amended 2011 law that permits payments to be suppressed when “credible” allegations of fraud have been made, but are disputed. The term “credible” is a new, lower standard for the administrative action, which was meant to address the pay-and-chase problem, Mr. Clark said. The law defines a “credible allegation of fraud” as an allegation from any source, including but not limited to fraud hotline complaints, data mining of claims, patterns identified through provider audits, civil false claims cases, and law enforcement investigations.

“That standard is easy to meet and agencies have every incentive to claim they’ve got so-called credible allegations of fraud in order to avoid being criticized later on for not preventing the monies from being dissipated,” he said. Because the law precludes health providers from appealing the fraud allegation to a federal court until all administrative remedies have been exhausted, “a health care services provider can quickly be put out of business, even if it turns out that the investigation proves not to be actionable.”

Prepayment reviews of claims can drag on for months, severely impacting a physician’s income, Mr. Shay added. In his experience, the majority of physicians under investigation are not trying to game the system, but rather don’t understand all of the administrative requirements related to filing claims. In some cases, the physicians’ notes are not complete, their bills are too high for services provided, or not enough documentation exists to support medical necessity.

“In the midst of that, you have doctors who are likely well-meaning, who have provided a service to a patient in need, and who are facing real economic hardship without an effective mechanism to challenge or end the prepayment review process,” he said.

Rather than more prepayment investigations, Mr. Shay would like to see CMS focus on physician education.

There needs to be “more emphasis on provider education in terms of compliance with program requirements,” he said. “It shouldn’t require a lawyer getting involved to find out what specifically [CMS] wants them to do. That should be part of the process as a standard.”

On Twitter @legal_med

Poll: Patients oppose extended resident work hours

The majority of patients support work-hour limits for medical residents and want tighter shift caps for second-year residents and above, according to a national poll published Sept. 13 by Public Citizen.

The survey of 500 consumers by Lake Research Partners found that 86% of respondents were opposed to eliminating the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s (ACGME) current 16-hour shift limit for first-year residents. Most respondents (80%) also favor decreasing the shift limit from 28 hours to 16 hours for second-year residents and above. More than three-quarters of respondents said hospital patients should be informed if a medical resident treating them has been working more than 16 hours without sleep.

“The public’s apprehension about resident shifts longer than 16 hours comports with the long-standing evidence on the risks of long resident work shifts for both the residents and their patients,” Michael Carome, MD, director of Public Citizen’s Health Research Group, said during a press conference. “Medical residents are not superhuman and, when sleep-deprived, put themselves, their patients, and others in harm’s way. This is not a partisan political issue, but one of public health and safety.”

But some physicians called the findings “obvious” and said they fail to address the full picture of work-hour limitations for residents. Evaluating only one aspect of a complex problem risks causing harm through unintended consequences, said Sharmila Dissanaike, MD, Peter C. Canizaro Chair of Surgery at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center in Lubbock.

“The poll reflects that the public would prefer a well-rested physician over a sleep-deprived one – an obvious finding – since we would all prefer our physicians, nurses, police officers, firemen, and anyone who provides essential care or services to us to be well rested,” Dr. Dissanaike said in an interview. “However, interpreting this result as a mandate from the public to increase restrictions on resident duty hours, while well intentioned, is shortsighted and neglects many salient aspects of the problem, including the high risk of increased handoffs and adverse impact on GME training as a whole.”

The poll is the latest development in an ongoing debate about resident work hours and whether cutting shift time for new doctors aids or undermines patient safety. Earlier this year, a host of physician associations called on ACGME to roll back its work limits on first-year residents. The medical associations say current duty-hour restrictions are not improving care, and that the limits are negatively impacting physician training. The American College of Surgeons (ACS) for example, recommends the only restrictions on resident duty hours be a total of 80 hours per week, averaged over a 4-week period, with no other limitations.