User login

Psychotic and needing prayer

CASE: Psychotic and assaultive

Mr. A, age 34, is involuntarily admitted to a psychiatric hospital after assaulting a family member and a police officer. He is charged with 2 counts of first-degree assault. He describes auditory hallucinations and believes God is telling him to refuse medication. One year earlier he was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Mr. A informs hospital staff that he is a Christian Scientist, and his religion precludes him from taking any medications. The local parish of the First Church of Christ, Scientist confirms that he is an active member. One day after admission, Mr. A is threatening and belligerent, and he continues to refuse any treatment.

How would you initially treat Mr. A?a) seek emergency guardianship

b) seek help from the Christian Science community

c) order the appropriate medication to effectively treat his symptoms

TREATMENT: Involuntary treatment

While in the hospital, Mr. A’s psychotic symptoms and aggressive behavior toward the staff and other patients lead to several psychiatric emergencies being declared and involuntary administration of antipsychotic medication. Because IM haloperidol, 5 mg/d, rapidly alleviates his symptoms, there is no need to pursue guardianship. Mr. A asks to meet with a member of the Christian Science community before his discharge, which is arranged. Upon being discharged, Mr. A schedules outpatient treatment at the community mental health center.

The author's observations

Mr. A’s case challenged staff to balance his clinical needs with his religious philosophy. Although psychotic, Mr. A provided a reason for refusing treatment—his belief in Christian Science—which would be considered a valid spiritual choice based on his values. However, his psychiatric symptoms created a dangerous situation for himself and others, which lead to emergency administration of antipsychotics against his will. Resolution of his symptoms did not warrant a petition for guardianship or a long-term involuntary hospitalization (Table 1). Allowing Mr. A to meet with a member of his church was crucial because it validated Mr. A’s religious practices and showed the staff’s willingness to respect his Christian Science beliefs.1,2

Honoring religious beliefs

Christian Science is based on the writings of Mary Baker Eddy and the Bible. Adherents believe that any form of evil, such as sin, disease, or death, is the opposite of God and is an illusion. Health care and treatment within the Christian Science community do not focus on what is wrong with the physical body, but rather what is wrong with the mind. Christian Scientists attempt healing through specific forms of prayer, not conventional methods such as medications or surgery.3 Christian Scientists believe there are no limits to the type of medical conditions that can be healed through prayer. Community members go to Christian Science practitioners for healing via prayer, focusing on the Bible and Mary Baker Eddy’s writings to alleviate their suffering.

The Christian Science church does not forbid its members from receiving conventional medical treatments, although prayer clearly is the preferred method of healing.4 Members can make their own choice about obtaining medical treatment. If they choose medical care, they cannot receive simultaneous treatment from Christian Science practitioners, but they can participate in other church activities. However, members compelled to get medical or psychiatric treatment via a guardianship or a court order can receive concurrent treatment from a Christian Science practitioner.

Other faith traditions generally do not draw such a clear line between medical treatment and religious healing. For example, Jehovah’s Witnesses have no prohibition against obtaining medical care, but they refuse blood transfusions, although they do accept medical alternatives to blood.5

ASSESSMENT: Remorse, reluctance

Mr. A stops taking his medication a few days after discharge, becomes psychotic, assaults his landlord, and is involuntarily readmitted to the hospital. His symptoms again are alleviated with IM haloperidol, 5 mg/d, and Mr. A is remorseful about his behavior while psychotic. He repeats his belief that his illness can be cured with prayer. The staff is reluctant to discharge Mr. A because of his history of nonadherence to treatment and assaultive episodes.

What are the next steps to consider in Mr. A’s treatment?a) seek guardianship because Mr. A does not appreciate the need for treatment

b) obtain a long-term commitment to the hospital with plans to conditionally release Mr. A when he is clinically stable

c) begin treatment with a long-acting injectable antipsychotic

EVALUATION: Next steps

The psychiatrist requests and receives a 3-year commitment for Mr. A from the probate court. The psychiatrist works with Mr. A and the community mental health center clinician to develop a conditional discharge plan in which Mr. A agrees to take medications as prescribed as a condition of his release. Mr. A initially is resistant to this plan. He is allowed to meet frequently with his Christian Science practitioner to discuss ways to continue treatment. Hospital staff supports these meetings, while explaining the importance of adhering to medication and how this will effectively treat his psychotic symptoms. Hospital staff does not negate or minimize Mr. A’s religious beliefs. The Christian Science practitioner allows Mr. A to continue his religious healing while receiving psychiatric care because he is a under court-ordered involuntary commitment. This leads Mr. A to find common ground between his religious beliefs and need for psychiatric treatment. Mr. A maintains his belief that he can be healed by prayer, but agrees to accept medications under the law of the probate commitment. To maximize adherence, he agrees to haloperidol decanoate, a long-acting injectable antipsychotic. He is conditionally discharged to continuing outpatient treatment at the community mental health center.

Mr. A adheres to treatment but begins to develop early signs of tardive dyskinesia (mild lip smacking and some tongue protrusion). Therefore, haloperidol decanoate is discontinued and replaced with oral olanzapine, 20 mg/d. Mr. A is no longer psychotic, and his psychotic symptoms are in remission. He continues to hold fast to his Christian Science beliefs.

One month before the end of his 3-year commitment, Mr. A informs his psychiatrist that he plans to stop his antipsychotic when the commitment ends and to pursue treatment with his Christian Science practitioner via prayer. He wants to prove to everyone that medications are no longer necessary.

What should Mr. A’s treating psychiatrist do?a) immediately readmit Mr. A involuntarily because of his potential dangerousness and impending treatment nonadherence

b) pursue guardianship because Mr. A is incapable of understanding that he has a serious mental illness

c) not pursue legal action but continue to treat Mr. A with antipsychotics and encourage compliance

d) readmit Mr. A to the hospital, request an extension of the commitment order, and consider a medication holiday in a safe setting to address Mr. A’s religious beliefs

OUTCOME: Court-ordered treatment

Mr. A agrees to hospitalization and at a court hearing is committed to the hospital for a period not to exceed 5 years. The judge also orders that Mr. A undergo a period of reducing or stopping his antipsychotic to see if he decompensates. The judicial order states that if it is determined that Mr. A no longer needs medication, the judge may reconsider the terms of the long-term commitment.

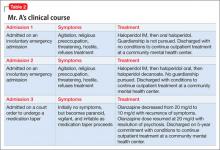

Mr. A, his inpatient and outpatient psychiatrists, and a Christian Science practitioner work together to develop a plan to taper his medication. Over 2 weeks, olanzapine is tapered from 20 mg/d to 10 mg/d. Two weeks into the taper, Mr. A becomes increasingly irritable, paranoid, and vigilant. The staff gives him prompt feedback about his apparent decompensation. Mr. A accepts this. He resumes taking olanzapine, 20 mg/d, and his symptoms resolve. He feels discouraged because taking medication is against his religious values. Nevertheless, he accepts the 5-year commitment as a court-mandated treatment that he must abide by. He is conditionally discharged from the hospital. For a summary of Mr. A’s clinical course, see Table 2.

Mr. A continues to do well in the community. New Hampshire’s law allowing up to a 5-year commitment to the hospital has been effective in maximizing Mr. A’s treatment adherence (Table 3).6 He has not been rehospitalized and his psychotic symptoms are in remission. Mr. A still believes his symptoms can be best treated with Christian Science prayer, but sees the state-imposed conditional discharge as a necessary “evil” that he must adhere to. He continues to be an active member of his church.

The author's observations

With the support of his outpatient and inpatient psychiatrists, treatment teams, and Christian Science practitioner, Mr. A has successfully integrated 2 seemingly opposing views regarding treatment, allowing him to live successfully in the community.

From this case, we learned that clinicians:

- need to understand patients’ religious beliefs and how these beliefs can impact their care

- must be aware that caring for patients from different religious traditions may present unique treatment challenges

- need to put their personal views regarding a patient’s religious beliefs aside and work with the patient to alleviate suffering

- must give patients ample opportunity to meet with their faith community, allowing adequate time for discussion and problem solving

Bottom Line

Balancing a patient’s clinical and spiritual needs can be challenging when those needs seem mutually exclusive. Clear communication, legal guidance, careful planning, and a strong therapeutic alliance can create opportunities for the patient to make both needs work to his advantage.

Related Resources

- Christian Science. www.christianscience.com.

- de Nesnera A, Vidaver RM. New Hampshire’s commitment law: treatment implications. New Hampshire Bar Journal. 2007;48(2):68-73.

- Ehman J. Religious diversity: practical points for health care

providers: www.uphs.upenn.edu/pastoral/resed/diversity_points.html.

Drug Brand Names

Haloperidol • Haldol

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Disclosure

Dr. de Nesnera reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Pavlo AM, Bursztajn H, Gutheil T. Christian Science and competence to make treatment choices: clinical challenges in assessing values. Int J Law Psych. 1987;10(4):395-401.

2. Pavlo AM, Bursztajn H, Gutheil T, et al. Weighing religious beliefs in determining competence. Hosp Comm Psych. 1987;38(4):350-352.

3. Eddy MB. Science and health with key to the scriptures. Boston, MA: Christian Science Publishing Company; 1875:1-17.

4. Eddy M. Science and health with key to the scriptures. Boston, MA: Christian Science Publishing Company; 1875: 167.

5. The growing demand for bloodless medicine and surgery. Awake! January 8, 2000:4-6. http://wol.jw.org/en/wol/d/r1/lp-e/102000003. Accessed June 4, 2013.

6. NH Rev Stat Ann § 135-C:27-46.

CASE: Psychotic and assaultive

Mr. A, age 34, is involuntarily admitted to a psychiatric hospital after assaulting a family member and a police officer. He is charged with 2 counts of first-degree assault. He describes auditory hallucinations and believes God is telling him to refuse medication. One year earlier he was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Mr. A informs hospital staff that he is a Christian Scientist, and his religion precludes him from taking any medications. The local parish of the First Church of Christ, Scientist confirms that he is an active member. One day after admission, Mr. A is threatening and belligerent, and he continues to refuse any treatment.

How would you initially treat Mr. A?a) seek emergency guardianship

b) seek help from the Christian Science community

c) order the appropriate medication to effectively treat his symptoms

TREATMENT: Involuntary treatment

While in the hospital, Mr. A’s psychotic symptoms and aggressive behavior toward the staff and other patients lead to several psychiatric emergencies being declared and involuntary administration of antipsychotic medication. Because IM haloperidol, 5 mg/d, rapidly alleviates his symptoms, there is no need to pursue guardianship. Mr. A asks to meet with a member of the Christian Science community before his discharge, which is arranged. Upon being discharged, Mr. A schedules outpatient treatment at the community mental health center.

The author's observations

Mr. A’s case challenged staff to balance his clinical needs with his religious philosophy. Although psychotic, Mr. A provided a reason for refusing treatment—his belief in Christian Science—which would be considered a valid spiritual choice based on his values. However, his psychiatric symptoms created a dangerous situation for himself and others, which lead to emergency administration of antipsychotics against his will. Resolution of his symptoms did not warrant a petition for guardianship or a long-term involuntary hospitalization (Table 1). Allowing Mr. A to meet with a member of his church was crucial because it validated Mr. A’s religious practices and showed the staff’s willingness to respect his Christian Science beliefs.1,2

Honoring religious beliefs

Christian Science is based on the writings of Mary Baker Eddy and the Bible. Adherents believe that any form of evil, such as sin, disease, or death, is the opposite of God and is an illusion. Health care and treatment within the Christian Science community do not focus on what is wrong with the physical body, but rather what is wrong with the mind. Christian Scientists attempt healing through specific forms of prayer, not conventional methods such as medications or surgery.3 Christian Scientists believe there are no limits to the type of medical conditions that can be healed through prayer. Community members go to Christian Science practitioners for healing via prayer, focusing on the Bible and Mary Baker Eddy’s writings to alleviate their suffering.

The Christian Science church does not forbid its members from receiving conventional medical treatments, although prayer clearly is the preferred method of healing.4 Members can make their own choice about obtaining medical treatment. If they choose medical care, they cannot receive simultaneous treatment from Christian Science practitioners, but they can participate in other church activities. However, members compelled to get medical or psychiatric treatment via a guardianship or a court order can receive concurrent treatment from a Christian Science practitioner.

Other faith traditions generally do not draw such a clear line between medical treatment and religious healing. For example, Jehovah’s Witnesses have no prohibition against obtaining medical care, but they refuse blood transfusions, although they do accept medical alternatives to blood.5

ASSESSMENT: Remorse, reluctance

Mr. A stops taking his medication a few days after discharge, becomes psychotic, assaults his landlord, and is involuntarily readmitted to the hospital. His symptoms again are alleviated with IM haloperidol, 5 mg/d, and Mr. A is remorseful about his behavior while psychotic. He repeats his belief that his illness can be cured with prayer. The staff is reluctant to discharge Mr. A because of his history of nonadherence to treatment and assaultive episodes.

What are the next steps to consider in Mr. A’s treatment?a) seek guardianship because Mr. A does not appreciate the need for treatment

b) obtain a long-term commitment to the hospital with plans to conditionally release Mr. A when he is clinically stable

c) begin treatment with a long-acting injectable antipsychotic

EVALUATION: Next steps

The psychiatrist requests and receives a 3-year commitment for Mr. A from the probate court. The psychiatrist works with Mr. A and the community mental health center clinician to develop a conditional discharge plan in which Mr. A agrees to take medications as prescribed as a condition of his release. Mr. A initially is resistant to this plan. He is allowed to meet frequently with his Christian Science practitioner to discuss ways to continue treatment. Hospital staff supports these meetings, while explaining the importance of adhering to medication and how this will effectively treat his psychotic symptoms. Hospital staff does not negate or minimize Mr. A’s religious beliefs. The Christian Science practitioner allows Mr. A to continue his religious healing while receiving psychiatric care because he is a under court-ordered involuntary commitment. This leads Mr. A to find common ground between his religious beliefs and need for psychiatric treatment. Mr. A maintains his belief that he can be healed by prayer, but agrees to accept medications under the law of the probate commitment. To maximize adherence, he agrees to haloperidol decanoate, a long-acting injectable antipsychotic. He is conditionally discharged to continuing outpatient treatment at the community mental health center.

Mr. A adheres to treatment but begins to develop early signs of tardive dyskinesia (mild lip smacking and some tongue protrusion). Therefore, haloperidol decanoate is discontinued and replaced with oral olanzapine, 20 mg/d. Mr. A is no longer psychotic, and his psychotic symptoms are in remission. He continues to hold fast to his Christian Science beliefs.

One month before the end of his 3-year commitment, Mr. A informs his psychiatrist that he plans to stop his antipsychotic when the commitment ends and to pursue treatment with his Christian Science practitioner via prayer. He wants to prove to everyone that medications are no longer necessary.

What should Mr. A’s treating psychiatrist do?a) immediately readmit Mr. A involuntarily because of his potential dangerousness and impending treatment nonadherence

b) pursue guardianship because Mr. A is incapable of understanding that he has a serious mental illness

c) not pursue legal action but continue to treat Mr. A with antipsychotics and encourage compliance

d) readmit Mr. A to the hospital, request an extension of the commitment order, and consider a medication holiday in a safe setting to address Mr. A’s religious beliefs

OUTCOME: Court-ordered treatment

Mr. A agrees to hospitalization and at a court hearing is committed to the hospital for a period not to exceed 5 years. The judge also orders that Mr. A undergo a period of reducing or stopping his antipsychotic to see if he decompensates. The judicial order states that if it is determined that Mr. A no longer needs medication, the judge may reconsider the terms of the long-term commitment.

Mr. A, his inpatient and outpatient psychiatrists, and a Christian Science practitioner work together to develop a plan to taper his medication. Over 2 weeks, olanzapine is tapered from 20 mg/d to 10 mg/d. Two weeks into the taper, Mr. A becomes increasingly irritable, paranoid, and vigilant. The staff gives him prompt feedback about his apparent decompensation. Mr. A accepts this. He resumes taking olanzapine, 20 mg/d, and his symptoms resolve. He feels discouraged because taking medication is against his religious values. Nevertheless, he accepts the 5-year commitment as a court-mandated treatment that he must abide by. He is conditionally discharged from the hospital. For a summary of Mr. A’s clinical course, see Table 2.

Mr. A continues to do well in the community. New Hampshire’s law allowing up to a 5-year commitment to the hospital has been effective in maximizing Mr. A’s treatment adherence (Table 3).6 He has not been rehospitalized and his psychotic symptoms are in remission. Mr. A still believes his symptoms can be best treated with Christian Science prayer, but sees the state-imposed conditional discharge as a necessary “evil” that he must adhere to. He continues to be an active member of his church.

The author's observations

With the support of his outpatient and inpatient psychiatrists, treatment teams, and Christian Science practitioner, Mr. A has successfully integrated 2 seemingly opposing views regarding treatment, allowing him to live successfully in the community.

From this case, we learned that clinicians:

- need to understand patients’ religious beliefs and how these beliefs can impact their care

- must be aware that caring for patients from different religious traditions may present unique treatment challenges

- need to put their personal views regarding a patient’s religious beliefs aside and work with the patient to alleviate suffering

- must give patients ample opportunity to meet with their faith community, allowing adequate time for discussion and problem solving

Bottom Line

Balancing a patient’s clinical and spiritual needs can be challenging when those needs seem mutually exclusive. Clear communication, legal guidance, careful planning, and a strong therapeutic alliance can create opportunities for the patient to make both needs work to his advantage.

Related Resources

- Christian Science. www.christianscience.com.

- de Nesnera A, Vidaver RM. New Hampshire’s commitment law: treatment implications. New Hampshire Bar Journal. 2007;48(2):68-73.

- Ehman J. Religious diversity: practical points for health care

providers: www.uphs.upenn.edu/pastoral/resed/diversity_points.html.

Drug Brand Names

Haloperidol • Haldol

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Disclosure

Dr. de Nesnera reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE: Psychotic and assaultive

Mr. A, age 34, is involuntarily admitted to a psychiatric hospital after assaulting a family member and a police officer. He is charged with 2 counts of first-degree assault. He describes auditory hallucinations and believes God is telling him to refuse medication. One year earlier he was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Mr. A informs hospital staff that he is a Christian Scientist, and his religion precludes him from taking any medications. The local parish of the First Church of Christ, Scientist confirms that he is an active member. One day after admission, Mr. A is threatening and belligerent, and he continues to refuse any treatment.

How would you initially treat Mr. A?a) seek emergency guardianship

b) seek help from the Christian Science community

c) order the appropriate medication to effectively treat his symptoms

TREATMENT: Involuntary treatment

While in the hospital, Mr. A’s psychotic symptoms and aggressive behavior toward the staff and other patients lead to several psychiatric emergencies being declared and involuntary administration of antipsychotic medication. Because IM haloperidol, 5 mg/d, rapidly alleviates his symptoms, there is no need to pursue guardianship. Mr. A asks to meet with a member of the Christian Science community before his discharge, which is arranged. Upon being discharged, Mr. A schedules outpatient treatment at the community mental health center.

The author's observations

Mr. A’s case challenged staff to balance his clinical needs with his religious philosophy. Although psychotic, Mr. A provided a reason for refusing treatment—his belief in Christian Science—which would be considered a valid spiritual choice based on his values. However, his psychiatric symptoms created a dangerous situation for himself and others, which lead to emergency administration of antipsychotics against his will. Resolution of his symptoms did not warrant a petition for guardianship or a long-term involuntary hospitalization (Table 1). Allowing Mr. A to meet with a member of his church was crucial because it validated Mr. A’s religious practices and showed the staff’s willingness to respect his Christian Science beliefs.1,2

Honoring religious beliefs

Christian Science is based on the writings of Mary Baker Eddy and the Bible. Adherents believe that any form of evil, such as sin, disease, or death, is the opposite of God and is an illusion. Health care and treatment within the Christian Science community do not focus on what is wrong with the physical body, but rather what is wrong with the mind. Christian Scientists attempt healing through specific forms of prayer, not conventional methods such as medications or surgery.3 Christian Scientists believe there are no limits to the type of medical conditions that can be healed through prayer. Community members go to Christian Science practitioners for healing via prayer, focusing on the Bible and Mary Baker Eddy’s writings to alleviate their suffering.

The Christian Science church does not forbid its members from receiving conventional medical treatments, although prayer clearly is the preferred method of healing.4 Members can make their own choice about obtaining medical treatment. If they choose medical care, they cannot receive simultaneous treatment from Christian Science practitioners, but they can participate in other church activities. However, members compelled to get medical or psychiatric treatment via a guardianship or a court order can receive concurrent treatment from a Christian Science practitioner.

Other faith traditions generally do not draw such a clear line between medical treatment and religious healing. For example, Jehovah’s Witnesses have no prohibition against obtaining medical care, but they refuse blood transfusions, although they do accept medical alternatives to blood.5

ASSESSMENT: Remorse, reluctance

Mr. A stops taking his medication a few days after discharge, becomes psychotic, assaults his landlord, and is involuntarily readmitted to the hospital. His symptoms again are alleviated with IM haloperidol, 5 mg/d, and Mr. A is remorseful about his behavior while psychotic. He repeats his belief that his illness can be cured with prayer. The staff is reluctant to discharge Mr. A because of his history of nonadherence to treatment and assaultive episodes.

What are the next steps to consider in Mr. A’s treatment?a) seek guardianship because Mr. A does not appreciate the need for treatment

b) obtain a long-term commitment to the hospital with plans to conditionally release Mr. A when he is clinically stable

c) begin treatment with a long-acting injectable antipsychotic

EVALUATION: Next steps

The psychiatrist requests and receives a 3-year commitment for Mr. A from the probate court. The psychiatrist works with Mr. A and the community mental health center clinician to develop a conditional discharge plan in which Mr. A agrees to take medications as prescribed as a condition of his release. Mr. A initially is resistant to this plan. He is allowed to meet frequently with his Christian Science practitioner to discuss ways to continue treatment. Hospital staff supports these meetings, while explaining the importance of adhering to medication and how this will effectively treat his psychotic symptoms. Hospital staff does not negate or minimize Mr. A’s religious beliefs. The Christian Science practitioner allows Mr. A to continue his religious healing while receiving psychiatric care because he is a under court-ordered involuntary commitment. This leads Mr. A to find common ground between his religious beliefs and need for psychiatric treatment. Mr. A maintains his belief that he can be healed by prayer, but agrees to accept medications under the law of the probate commitment. To maximize adherence, he agrees to haloperidol decanoate, a long-acting injectable antipsychotic. He is conditionally discharged to continuing outpatient treatment at the community mental health center.

Mr. A adheres to treatment but begins to develop early signs of tardive dyskinesia (mild lip smacking and some tongue protrusion). Therefore, haloperidol decanoate is discontinued and replaced with oral olanzapine, 20 mg/d. Mr. A is no longer psychotic, and his psychotic symptoms are in remission. He continues to hold fast to his Christian Science beliefs.

One month before the end of his 3-year commitment, Mr. A informs his psychiatrist that he plans to stop his antipsychotic when the commitment ends and to pursue treatment with his Christian Science practitioner via prayer. He wants to prove to everyone that medications are no longer necessary.

What should Mr. A’s treating psychiatrist do?a) immediately readmit Mr. A involuntarily because of his potential dangerousness and impending treatment nonadherence

b) pursue guardianship because Mr. A is incapable of understanding that he has a serious mental illness

c) not pursue legal action but continue to treat Mr. A with antipsychotics and encourage compliance

d) readmit Mr. A to the hospital, request an extension of the commitment order, and consider a medication holiday in a safe setting to address Mr. A’s religious beliefs

OUTCOME: Court-ordered treatment

Mr. A agrees to hospitalization and at a court hearing is committed to the hospital for a period not to exceed 5 years. The judge also orders that Mr. A undergo a period of reducing or stopping his antipsychotic to see if he decompensates. The judicial order states that if it is determined that Mr. A no longer needs medication, the judge may reconsider the terms of the long-term commitment.

Mr. A, his inpatient and outpatient psychiatrists, and a Christian Science practitioner work together to develop a plan to taper his medication. Over 2 weeks, olanzapine is tapered from 20 mg/d to 10 mg/d. Two weeks into the taper, Mr. A becomes increasingly irritable, paranoid, and vigilant. The staff gives him prompt feedback about his apparent decompensation. Mr. A accepts this. He resumes taking olanzapine, 20 mg/d, and his symptoms resolve. He feels discouraged because taking medication is against his religious values. Nevertheless, he accepts the 5-year commitment as a court-mandated treatment that he must abide by. He is conditionally discharged from the hospital. For a summary of Mr. A’s clinical course, see Table 2.

Mr. A continues to do well in the community. New Hampshire’s law allowing up to a 5-year commitment to the hospital has been effective in maximizing Mr. A’s treatment adherence (Table 3).6 He has not been rehospitalized and his psychotic symptoms are in remission. Mr. A still believes his symptoms can be best treated with Christian Science prayer, but sees the state-imposed conditional discharge as a necessary “evil” that he must adhere to. He continues to be an active member of his church.

The author's observations

With the support of his outpatient and inpatient psychiatrists, treatment teams, and Christian Science practitioner, Mr. A has successfully integrated 2 seemingly opposing views regarding treatment, allowing him to live successfully in the community.

From this case, we learned that clinicians:

- need to understand patients’ religious beliefs and how these beliefs can impact their care

- must be aware that caring for patients from different religious traditions may present unique treatment challenges

- need to put their personal views regarding a patient’s religious beliefs aside and work with the patient to alleviate suffering

- must give patients ample opportunity to meet with their faith community, allowing adequate time for discussion and problem solving

Bottom Line

Balancing a patient’s clinical and spiritual needs can be challenging when those needs seem mutually exclusive. Clear communication, legal guidance, careful planning, and a strong therapeutic alliance can create opportunities for the patient to make both needs work to his advantage.

Related Resources

- Christian Science. www.christianscience.com.

- de Nesnera A, Vidaver RM. New Hampshire’s commitment law: treatment implications. New Hampshire Bar Journal. 2007;48(2):68-73.

- Ehman J. Religious diversity: practical points for health care

providers: www.uphs.upenn.edu/pastoral/resed/diversity_points.html.

Drug Brand Names

Haloperidol • Haldol

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Disclosure

Dr. de Nesnera reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Pavlo AM, Bursztajn H, Gutheil T. Christian Science and competence to make treatment choices: clinical challenges in assessing values. Int J Law Psych. 1987;10(4):395-401.

2. Pavlo AM, Bursztajn H, Gutheil T, et al. Weighing religious beliefs in determining competence. Hosp Comm Psych. 1987;38(4):350-352.

3. Eddy MB. Science and health with key to the scriptures. Boston, MA: Christian Science Publishing Company; 1875:1-17.

4. Eddy M. Science and health with key to the scriptures. Boston, MA: Christian Science Publishing Company; 1875: 167.

5. The growing demand for bloodless medicine and surgery. Awake! January 8, 2000:4-6. http://wol.jw.org/en/wol/d/r1/lp-e/102000003. Accessed June 4, 2013.

6. NH Rev Stat Ann § 135-C:27-46.

1. Pavlo AM, Bursztajn H, Gutheil T. Christian Science and competence to make treatment choices: clinical challenges in assessing values. Int J Law Psych. 1987;10(4):395-401.

2. Pavlo AM, Bursztajn H, Gutheil T, et al. Weighing religious beliefs in determining competence. Hosp Comm Psych. 1987;38(4):350-352.

3. Eddy MB. Science and health with key to the scriptures. Boston, MA: Christian Science Publishing Company; 1875:1-17.

4. Eddy M. Science and health with key to the scriptures. Boston, MA: Christian Science Publishing Company; 1875: 167.

5. The growing demand for bloodless medicine and surgery. Awake! January 8, 2000:4-6. http://wol.jw.org/en/wol/d/r1/lp-e/102000003. Accessed June 4, 2013.

6. NH Rev Stat Ann § 135-C:27-46.

Gasping for relief

CASE: Food issues

Ms. A, age 62, has a 40-year history of paranoid schizophrenia, which has been well controlled with olanzapine, 20 mg/d, for many years. Two weeks ago, she stops taking her medication and is brought to a state-run psychiatric hospital by law enforcement officers because of worsening paranoia and hostility. She is disheveled, intermittently denudative, and confused. Ms. A has type II diabetes, gastroesophageal reflux disease, obesity (body mass index of 34.75 kg/m2), and poor dentition. She has no history of substance abuse.

During the first 2 days in the hospital Ms. A refuses to eat, stating that the food is “poisoned,” but accepts 1 oral dose of aripiprazole, 25 mg. On hospital day 3, Ms. A is less hostile and eats dinner with the other patients. A few minutes after beginning her meal, Ms. A abruptly stands up and puts her hands to her throat. She looks frightened, and cannot speak.

A staff member asks Ms. A if she is choking and she nods. Because the psychiatric hospital does not have an emergency room, the staff call 911, and a staff member gives Ms. A back blows, but no food is forced out. Next, nursing staff start abdominal thrusts (Heimlich maneuver) without success. Ms. A then loses consciousness and the staff lowers her to the ground. The nurse looks in Ms. A’s mouth, but can’t see what is blocking her throat. Attempts to provide rescue breathing are unproductive because a foreign body obstructs Ms. A’s airway. A staff member continues abdominal thrusts once Ms. A is on the ground. She has no pulse, and CPR is initiated.

Emergency medical technicians arrive within 7 minutes and suction a piece of hot dog from Ms. A’s trachea. She is then taken to a nearby emergency department, where neurologic examination reveals signs of brain death.

Ms. A dies a few days later. The cause of death is respiratory and cardiac failure secondary to choking and foreign body obstruction. A review of Ms. A’s history reveals she had past episodes of choking and a habit of rapidly ingesting large amounts of food (tachyphagia).

The authors’ observations

The term “café coronary” describes sudden unexpected death caused by airway obstruction by food.1 In 1975, Henry Heimlich described the abdominal thrusting maneuver recommended to prevent these fatalities.2 For more than a century, choking has been recognized as a cause of death in individuals with severe mental illness.3 An analysis of sudden deaths among psychiatric in-patients in Ireland found that choking accounted for 10% of deaths over 10 years.4 An Australian study reported that individuals with schizophrenia had 20-fold greater risk of death by choking than the general population.5 Another study found the mortality rate attributable to choking was 8-fold higher for psychiatric inpatients than the general population,6 and a study in the United States reported that for every 1,000 deaths among psychiatric inpatients, 0.6 were caused by asphyxia,7 which is 100 times greater than the general population reported in the same time.8

Physiological mechanisms associated with impaired swallowing include:

- dopamine blockade, which could produce central and peripheral impairment of swallowing9

- anticholinergic effect leading to impaired esophageal motility

- impaired gag reflex.10

Multiple factors increase mentally ill individuals’ risk of death by choking (Table 1).11 Patients with schizophrenia may exhibit impaired swallowing mechanism, irrespective of psychotropic medications.12 Schizophrenia patients also could exhibit pica behavior—persistent and culturally and developmentally inappropriate ingestion of non-nutritive substances. Examples of pica behavior include ingesting rolled can lids13 and coins14,15 and coprophagia.16 Pica behavior increases the risk for choking, and has been implicated in deaths of individuals with schizophrenia.17

Medications with dopamine blocking and anticholinergic effects may increase choking risk.18 These medications could produce extrapyramidal side effects and parkinsonism, which might impair swallowing. Psychotropic medications could increase appetite and food craving, which in turn may lead to overeating and tachyphagia. In addition, many individuals suffering from severe mental illness have poor dentition, which could make chewing food difficult.19 Psychiatric patients are more likely to be obese, which also increases the risk of choking.

Table 1

Risk factors for choking in mentally ill patients

| Age (>60) |

| Impaired swallowing (schizophrenia patients are at greater risk) |

| Parkinsonism |

| Poor dentition |

| Schizophrenia |

| Tachyphagia (rapid eating) |

| Tardive dyskinesia |

| Obesity |

| Source: Reference 11 |

OUTCOME: Prevention strategies

New Hampshire Hospital’s administration implemented a plan to increase the staff’s awareness of choking risks in mentally ill patients. Nurses complete nutrition screens along with the initial nursing database assessment on all patients during the admission process, and are encouraged to contact registered dieticians for a nutrition review and assessment if a psychiatric patient is thought to be at risk for choking. Registered dieticians work with nursing staff to promptly complete nutrition assessments and address eating-related problems.

Direct care staff were reminded that all inpatient units have a battery-powered, portable compact suction unit available that can be used in a choking emergency. The hospital’s cardiopulmonary resuscitation instructors emphasize the importance of the abdominal thrust maneuver during all staff training sessions.

The hospital’s administration and staff did not reach a consensus on whether physicians should attempt a tracheotomy when other measures to dislodge a foreign object from a patient’s throat fail. Instead, the focus remains on assessing and treating the clinical emergency and obtaining rapid intervention by emergency medical technicians.

The authors’ observations

The following recommendations may help minimize or prevent choking events in inpatient units:

- Ensure all staff who care for patients are trained regularly on emergency first aid for choking victims, including proper use of abdominal thrusts (Heimlich maneuver) (Table 2).20

- Educate staff about which patients may be at higher risk for choking.

- Assess for a history of choking incidents and/or the presence of swallowing problems in patients at risk for choking.

- Supervise meals and instruct staff to look for patients who display dysphagia.

- Consider ordering a swallowing evaluation performed by a speech therapist in patients who manifest dysphagia.

- Avoid polypharmacy of drugs with anticholinergic and/or potent dopamine blocking effects, such as olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol.

- Teach safe eating habits to patients who are at risk for choking.

- Contact outpatient care providers of patients at risk for choking and inform them of the need for further education on safe eating habits, a dietary evaluation, and/or a swallowing evaluation.

Implementing these measures may reduce choking incidents and could save lives.

Table 2

American Red Cross guidelines for treating a conscious, choking adult

| Send someone to call 911 |

| Lean person forward and give 5 back blows with heel of your hand |

| Give 5 quick abdominal thrusts by placing the thumbside of your fist against the middle of the victim’s abdomen, just above the navel. Grab your fist with the other hand. In obese or pregnant adults, place your fist in the middle of the breastbone |

| Continue giving 5 back blows and 5 abdominal thrusts until the object is forced out or the person breathes or coughs on his or her own |

| Source: Reference 20 |

Related Resources

- Hwang SJ, Tsai SJ, Chen IJ, et al. Choking incidents among psychiatric inpatients: a retrospective study in Chutung Veterans General Hospital. J Chin Med Assoc. 2010;73(8):419-424.

- American College of Emergency Physicians Foundation. What to do in a medical emergency. Choking. www.emergencycareforyou.org/EmergencyManual/WhatToDoInMedicalEmergency/Default.aspx?id=224.

Drug Brand Names

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Risperidone • Risperdal

Disclosures

Dr. de Nesnera reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. Dr. Folks is a consultant and speaker for Pfizer Inc., a speaker for Forest Pharmaceuticals, and has received a research grant from Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

1. Haugen RK. The café coronary: sudden deaths in restaurants. JAMA. 1963;186:142-143.

2. Heimlich HJ. A life-saving maneuver to prevent food-choking. JAMA. 1975;234:398-401.

3. Hammond WA. A treatise on insanity and its medical relations. New York, NY: D. Appleton and Company; 1883:724.

4. Corcoran E, Walsh D. Obstructive asphyxia: a cause of excess mortality in psychiatric patients. Ir J Psychol Med. 2003;20:88-90.

5. Ruschena D, Mullen PE, Palmer S, et al. Choking deaths: the role of antipsychotic medication. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:446-450.

6. Yim PHW, Chong CSY. Choking in psychiatric patients: associations and outcomes. Hong Kong Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;19:145-149.

7. Craig TJ. Medication use and deaths attributed to asphyxia among psychiatric patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137:1366-1373.

8. Mittleman RE, Wetli CV. The fatal café coronary. Foreign-body airway obstruction. JAMA. 1982;247:1285-1288.

9. Bieger D, Giles SA, Hockman CH. Dopaminergic influences on swallowing. Neuropharmacology. 1977;16:243-252.

10. Bettarello A, Tuttle SG, Grossman MI. Effects of autonomic drugs on gastroesophageal reflux. Gastroenterology. 1960;39:340-346.

11. Fioritti A, Giaccotto L, Melega V. Choking incidents among psychiatric patients: retrospective analysis of thirty-one cases from the west Bologna psychiatric wards. Can J Psychiatry. 1997;42:515-520.

12. Hussar AE, Bragg DG. The effect of chlorpromazine on the swallowing function in schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1969;126:570-573.

13. Abraham B, Alao AO. An unusual body ingestion in a schizophrenic patient: case report. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2005;35(3):313-318.

14. Beecroft N, Bach L, Tunstall N, et al. An unusual case of pica. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998;13(9):638-641.

15. Pawa S, Khalifa AJ, Ehrinpreis MN, et al. Zinc toxicity from massive and prolonged coin ingestion in an adult. Am J Med Sci. 2008;336(5):430-433.

16. Beck DA, Frohberg NR. Coprophagia in an elderly man: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2005;35(4):417-427.

17. Dumaguing NI, Singh I, Sethi M, et al. Pica in the geriatric mentally ill: unrelenting and potentially fatal. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2003;16(3):189-191.

18. Bazemore H, Tonkonogy J, Ananth R. Dysphagia in psychiatric patients: clinical videofluoroscopic study. Dysphagia. 1991;6:62-65.

19. von Brauchitsch H, May W. Deaths from aspiration and asphyxiation in a mental hospital. Arch Gen Psych. 1968;18:129-136.

20. American Red Cross. Treatment for a conscious choking adult. Available at: http://www.redcross.org/flash/brr/English-html/conscious-choking.asp. Accessed August 27, 2010.

CASE: Food issues

Ms. A, age 62, has a 40-year history of paranoid schizophrenia, which has been well controlled with olanzapine, 20 mg/d, for many years. Two weeks ago, she stops taking her medication and is brought to a state-run psychiatric hospital by law enforcement officers because of worsening paranoia and hostility. She is disheveled, intermittently denudative, and confused. Ms. A has type II diabetes, gastroesophageal reflux disease, obesity (body mass index of 34.75 kg/m2), and poor dentition. She has no history of substance abuse.

During the first 2 days in the hospital Ms. A refuses to eat, stating that the food is “poisoned,” but accepts 1 oral dose of aripiprazole, 25 mg. On hospital day 3, Ms. A is less hostile and eats dinner with the other patients. A few minutes after beginning her meal, Ms. A abruptly stands up and puts her hands to her throat. She looks frightened, and cannot speak.

A staff member asks Ms. A if she is choking and she nods. Because the psychiatric hospital does not have an emergency room, the staff call 911, and a staff member gives Ms. A back blows, but no food is forced out. Next, nursing staff start abdominal thrusts (Heimlich maneuver) without success. Ms. A then loses consciousness and the staff lowers her to the ground. The nurse looks in Ms. A’s mouth, but can’t see what is blocking her throat. Attempts to provide rescue breathing are unproductive because a foreign body obstructs Ms. A’s airway. A staff member continues abdominal thrusts once Ms. A is on the ground. She has no pulse, and CPR is initiated.

Emergency medical technicians arrive within 7 minutes and suction a piece of hot dog from Ms. A’s trachea. She is then taken to a nearby emergency department, where neurologic examination reveals signs of brain death.

Ms. A dies a few days later. The cause of death is respiratory and cardiac failure secondary to choking and foreign body obstruction. A review of Ms. A’s history reveals she had past episodes of choking and a habit of rapidly ingesting large amounts of food (tachyphagia).

The authors’ observations

The term “café coronary” describes sudden unexpected death caused by airway obstruction by food.1 In 1975, Henry Heimlich described the abdominal thrusting maneuver recommended to prevent these fatalities.2 For more than a century, choking has been recognized as a cause of death in individuals with severe mental illness.3 An analysis of sudden deaths among psychiatric in-patients in Ireland found that choking accounted for 10% of deaths over 10 years.4 An Australian study reported that individuals with schizophrenia had 20-fold greater risk of death by choking than the general population.5 Another study found the mortality rate attributable to choking was 8-fold higher for psychiatric inpatients than the general population,6 and a study in the United States reported that for every 1,000 deaths among psychiatric inpatients, 0.6 were caused by asphyxia,7 which is 100 times greater than the general population reported in the same time.8

Physiological mechanisms associated with impaired swallowing include:

- dopamine blockade, which could produce central and peripheral impairment of swallowing9

- anticholinergic effect leading to impaired esophageal motility

- impaired gag reflex.10

Multiple factors increase mentally ill individuals’ risk of death by choking (Table 1).11 Patients with schizophrenia may exhibit impaired swallowing mechanism, irrespective of psychotropic medications.12 Schizophrenia patients also could exhibit pica behavior—persistent and culturally and developmentally inappropriate ingestion of non-nutritive substances. Examples of pica behavior include ingesting rolled can lids13 and coins14,15 and coprophagia.16 Pica behavior increases the risk for choking, and has been implicated in deaths of individuals with schizophrenia.17

Medications with dopamine blocking and anticholinergic effects may increase choking risk.18 These medications could produce extrapyramidal side effects and parkinsonism, which might impair swallowing. Psychotropic medications could increase appetite and food craving, which in turn may lead to overeating and tachyphagia. In addition, many individuals suffering from severe mental illness have poor dentition, which could make chewing food difficult.19 Psychiatric patients are more likely to be obese, which also increases the risk of choking.

Table 1

Risk factors for choking in mentally ill patients

| Age (>60) |

| Impaired swallowing (schizophrenia patients are at greater risk) |

| Parkinsonism |

| Poor dentition |

| Schizophrenia |

| Tachyphagia (rapid eating) |

| Tardive dyskinesia |

| Obesity |

| Source: Reference 11 |

OUTCOME: Prevention strategies

New Hampshire Hospital’s administration implemented a plan to increase the staff’s awareness of choking risks in mentally ill patients. Nurses complete nutrition screens along with the initial nursing database assessment on all patients during the admission process, and are encouraged to contact registered dieticians for a nutrition review and assessment if a psychiatric patient is thought to be at risk for choking. Registered dieticians work with nursing staff to promptly complete nutrition assessments and address eating-related problems.

Direct care staff were reminded that all inpatient units have a battery-powered, portable compact suction unit available that can be used in a choking emergency. The hospital’s cardiopulmonary resuscitation instructors emphasize the importance of the abdominal thrust maneuver during all staff training sessions.

The hospital’s administration and staff did not reach a consensus on whether physicians should attempt a tracheotomy when other measures to dislodge a foreign object from a patient’s throat fail. Instead, the focus remains on assessing and treating the clinical emergency and obtaining rapid intervention by emergency medical technicians.

The authors’ observations

The following recommendations may help minimize or prevent choking events in inpatient units:

- Ensure all staff who care for patients are trained regularly on emergency first aid for choking victims, including proper use of abdominal thrusts (Heimlich maneuver) (Table 2).20

- Educate staff about which patients may be at higher risk for choking.

- Assess for a history of choking incidents and/or the presence of swallowing problems in patients at risk for choking.

- Supervise meals and instruct staff to look for patients who display dysphagia.

- Consider ordering a swallowing evaluation performed by a speech therapist in patients who manifest dysphagia.

- Avoid polypharmacy of drugs with anticholinergic and/or potent dopamine blocking effects, such as olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol.

- Teach safe eating habits to patients who are at risk for choking.

- Contact outpatient care providers of patients at risk for choking and inform them of the need for further education on safe eating habits, a dietary evaluation, and/or a swallowing evaluation.

Implementing these measures may reduce choking incidents and could save lives.

Table 2

American Red Cross guidelines for treating a conscious, choking adult

| Send someone to call 911 |

| Lean person forward and give 5 back blows with heel of your hand |

| Give 5 quick abdominal thrusts by placing the thumbside of your fist against the middle of the victim’s abdomen, just above the navel. Grab your fist with the other hand. In obese or pregnant adults, place your fist in the middle of the breastbone |

| Continue giving 5 back blows and 5 abdominal thrusts until the object is forced out or the person breathes or coughs on his or her own |

| Source: Reference 20 |

Related Resources

- Hwang SJ, Tsai SJ, Chen IJ, et al. Choking incidents among psychiatric inpatients: a retrospective study in Chutung Veterans General Hospital. J Chin Med Assoc. 2010;73(8):419-424.

- American College of Emergency Physicians Foundation. What to do in a medical emergency. Choking. www.emergencycareforyou.org/EmergencyManual/WhatToDoInMedicalEmergency/Default.aspx?id=224.

Drug Brand Names

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Risperidone • Risperdal

Disclosures

Dr. de Nesnera reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. Dr. Folks is a consultant and speaker for Pfizer Inc., a speaker for Forest Pharmaceuticals, and has received a research grant from Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

CASE: Food issues

Ms. A, age 62, has a 40-year history of paranoid schizophrenia, which has been well controlled with olanzapine, 20 mg/d, for many years. Two weeks ago, she stops taking her medication and is brought to a state-run psychiatric hospital by law enforcement officers because of worsening paranoia and hostility. She is disheveled, intermittently denudative, and confused. Ms. A has type II diabetes, gastroesophageal reflux disease, obesity (body mass index of 34.75 kg/m2), and poor dentition. She has no history of substance abuse.

During the first 2 days in the hospital Ms. A refuses to eat, stating that the food is “poisoned,” but accepts 1 oral dose of aripiprazole, 25 mg. On hospital day 3, Ms. A is less hostile and eats dinner with the other patients. A few minutes after beginning her meal, Ms. A abruptly stands up and puts her hands to her throat. She looks frightened, and cannot speak.

A staff member asks Ms. A if she is choking and she nods. Because the psychiatric hospital does not have an emergency room, the staff call 911, and a staff member gives Ms. A back blows, but no food is forced out. Next, nursing staff start abdominal thrusts (Heimlich maneuver) without success. Ms. A then loses consciousness and the staff lowers her to the ground. The nurse looks in Ms. A’s mouth, but can’t see what is blocking her throat. Attempts to provide rescue breathing are unproductive because a foreign body obstructs Ms. A’s airway. A staff member continues abdominal thrusts once Ms. A is on the ground. She has no pulse, and CPR is initiated.

Emergency medical technicians arrive within 7 minutes and suction a piece of hot dog from Ms. A’s trachea. She is then taken to a nearby emergency department, where neurologic examination reveals signs of brain death.

Ms. A dies a few days later. The cause of death is respiratory and cardiac failure secondary to choking and foreign body obstruction. A review of Ms. A’s history reveals she had past episodes of choking and a habit of rapidly ingesting large amounts of food (tachyphagia).

The authors’ observations

The term “café coronary” describes sudden unexpected death caused by airway obstruction by food.1 In 1975, Henry Heimlich described the abdominal thrusting maneuver recommended to prevent these fatalities.2 For more than a century, choking has been recognized as a cause of death in individuals with severe mental illness.3 An analysis of sudden deaths among psychiatric in-patients in Ireland found that choking accounted for 10% of deaths over 10 years.4 An Australian study reported that individuals with schizophrenia had 20-fold greater risk of death by choking than the general population.5 Another study found the mortality rate attributable to choking was 8-fold higher for psychiatric inpatients than the general population,6 and a study in the United States reported that for every 1,000 deaths among psychiatric inpatients, 0.6 were caused by asphyxia,7 which is 100 times greater than the general population reported in the same time.8

Physiological mechanisms associated with impaired swallowing include:

- dopamine blockade, which could produce central and peripheral impairment of swallowing9

- anticholinergic effect leading to impaired esophageal motility

- impaired gag reflex.10

Multiple factors increase mentally ill individuals’ risk of death by choking (Table 1).11 Patients with schizophrenia may exhibit impaired swallowing mechanism, irrespective of psychotropic medications.12 Schizophrenia patients also could exhibit pica behavior—persistent and culturally and developmentally inappropriate ingestion of non-nutritive substances. Examples of pica behavior include ingesting rolled can lids13 and coins14,15 and coprophagia.16 Pica behavior increases the risk for choking, and has been implicated in deaths of individuals with schizophrenia.17

Medications with dopamine blocking and anticholinergic effects may increase choking risk.18 These medications could produce extrapyramidal side effects and parkinsonism, which might impair swallowing. Psychotropic medications could increase appetite and food craving, which in turn may lead to overeating and tachyphagia. In addition, many individuals suffering from severe mental illness have poor dentition, which could make chewing food difficult.19 Psychiatric patients are more likely to be obese, which also increases the risk of choking.

Table 1

Risk factors for choking in mentally ill patients

| Age (>60) |

| Impaired swallowing (schizophrenia patients are at greater risk) |

| Parkinsonism |

| Poor dentition |

| Schizophrenia |

| Tachyphagia (rapid eating) |

| Tardive dyskinesia |

| Obesity |

| Source: Reference 11 |

OUTCOME: Prevention strategies

New Hampshire Hospital’s administration implemented a plan to increase the staff’s awareness of choking risks in mentally ill patients. Nurses complete nutrition screens along with the initial nursing database assessment on all patients during the admission process, and are encouraged to contact registered dieticians for a nutrition review and assessment if a psychiatric patient is thought to be at risk for choking. Registered dieticians work with nursing staff to promptly complete nutrition assessments and address eating-related problems.

Direct care staff were reminded that all inpatient units have a battery-powered, portable compact suction unit available that can be used in a choking emergency. The hospital’s cardiopulmonary resuscitation instructors emphasize the importance of the abdominal thrust maneuver during all staff training sessions.

The hospital’s administration and staff did not reach a consensus on whether physicians should attempt a tracheotomy when other measures to dislodge a foreign object from a patient’s throat fail. Instead, the focus remains on assessing and treating the clinical emergency and obtaining rapid intervention by emergency medical technicians.

The authors’ observations

The following recommendations may help minimize or prevent choking events in inpatient units:

- Ensure all staff who care for patients are trained regularly on emergency first aid for choking victims, including proper use of abdominal thrusts (Heimlich maneuver) (Table 2).20

- Educate staff about which patients may be at higher risk for choking.

- Assess for a history of choking incidents and/or the presence of swallowing problems in patients at risk for choking.

- Supervise meals and instruct staff to look for patients who display dysphagia.

- Consider ordering a swallowing evaluation performed by a speech therapist in patients who manifest dysphagia.

- Avoid polypharmacy of drugs with anticholinergic and/or potent dopamine blocking effects, such as olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol.

- Teach safe eating habits to patients who are at risk for choking.

- Contact outpatient care providers of patients at risk for choking and inform them of the need for further education on safe eating habits, a dietary evaluation, and/or a swallowing evaluation.

Implementing these measures may reduce choking incidents and could save lives.

Table 2

American Red Cross guidelines for treating a conscious, choking adult

| Send someone to call 911 |

| Lean person forward and give 5 back blows with heel of your hand |

| Give 5 quick abdominal thrusts by placing the thumbside of your fist against the middle of the victim’s abdomen, just above the navel. Grab your fist with the other hand. In obese or pregnant adults, place your fist in the middle of the breastbone |

| Continue giving 5 back blows and 5 abdominal thrusts until the object is forced out or the person breathes or coughs on his or her own |

| Source: Reference 20 |

Related Resources

- Hwang SJ, Tsai SJ, Chen IJ, et al. Choking incidents among psychiatric inpatients: a retrospective study in Chutung Veterans General Hospital. J Chin Med Assoc. 2010;73(8):419-424.

- American College of Emergency Physicians Foundation. What to do in a medical emergency. Choking. www.emergencycareforyou.org/EmergencyManual/WhatToDoInMedicalEmergency/Default.aspx?id=224.

Drug Brand Names

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Risperidone • Risperdal

Disclosures

Dr. de Nesnera reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. Dr. Folks is a consultant and speaker for Pfizer Inc., a speaker for Forest Pharmaceuticals, and has received a research grant from Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

1. Haugen RK. The café coronary: sudden deaths in restaurants. JAMA. 1963;186:142-143.

2. Heimlich HJ. A life-saving maneuver to prevent food-choking. JAMA. 1975;234:398-401.

3. Hammond WA. A treatise on insanity and its medical relations. New York, NY: D. Appleton and Company; 1883:724.

4. Corcoran E, Walsh D. Obstructive asphyxia: a cause of excess mortality in psychiatric patients. Ir J Psychol Med. 2003;20:88-90.

5. Ruschena D, Mullen PE, Palmer S, et al. Choking deaths: the role of antipsychotic medication. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:446-450.

6. Yim PHW, Chong CSY. Choking in psychiatric patients: associations and outcomes. Hong Kong Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;19:145-149.

7. Craig TJ. Medication use and deaths attributed to asphyxia among psychiatric patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137:1366-1373.

8. Mittleman RE, Wetli CV. The fatal café coronary. Foreign-body airway obstruction. JAMA. 1982;247:1285-1288.

9. Bieger D, Giles SA, Hockman CH. Dopaminergic influences on swallowing. Neuropharmacology. 1977;16:243-252.

10. Bettarello A, Tuttle SG, Grossman MI. Effects of autonomic drugs on gastroesophageal reflux. Gastroenterology. 1960;39:340-346.

11. Fioritti A, Giaccotto L, Melega V. Choking incidents among psychiatric patients: retrospective analysis of thirty-one cases from the west Bologna psychiatric wards. Can J Psychiatry. 1997;42:515-520.

12. Hussar AE, Bragg DG. The effect of chlorpromazine on the swallowing function in schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1969;126:570-573.

13. Abraham B, Alao AO. An unusual body ingestion in a schizophrenic patient: case report. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2005;35(3):313-318.

14. Beecroft N, Bach L, Tunstall N, et al. An unusual case of pica. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998;13(9):638-641.

15. Pawa S, Khalifa AJ, Ehrinpreis MN, et al. Zinc toxicity from massive and prolonged coin ingestion in an adult. Am J Med Sci. 2008;336(5):430-433.

16. Beck DA, Frohberg NR. Coprophagia in an elderly man: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2005;35(4):417-427.

17. Dumaguing NI, Singh I, Sethi M, et al. Pica in the geriatric mentally ill: unrelenting and potentially fatal. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2003;16(3):189-191.

18. Bazemore H, Tonkonogy J, Ananth R. Dysphagia in psychiatric patients: clinical videofluoroscopic study. Dysphagia. 1991;6:62-65.

19. von Brauchitsch H, May W. Deaths from aspiration and asphyxiation in a mental hospital. Arch Gen Psych. 1968;18:129-136.

20. American Red Cross. Treatment for a conscious choking adult. Available at: http://www.redcross.org/flash/brr/English-html/conscious-choking.asp. Accessed August 27, 2010.

1. Haugen RK. The café coronary: sudden deaths in restaurants. JAMA. 1963;186:142-143.

2. Heimlich HJ. A life-saving maneuver to prevent food-choking. JAMA. 1975;234:398-401.

3. Hammond WA. A treatise on insanity and its medical relations. New York, NY: D. Appleton and Company; 1883:724.

4. Corcoran E, Walsh D. Obstructive asphyxia: a cause of excess mortality in psychiatric patients. Ir J Psychol Med. 2003;20:88-90.

5. Ruschena D, Mullen PE, Palmer S, et al. Choking deaths: the role of antipsychotic medication. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:446-450.

6. Yim PHW, Chong CSY. Choking in psychiatric patients: associations and outcomes. Hong Kong Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;19:145-149.

7. Craig TJ. Medication use and deaths attributed to asphyxia among psychiatric patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137:1366-1373.

8. Mittleman RE, Wetli CV. The fatal café coronary. Foreign-body airway obstruction. JAMA. 1982;247:1285-1288.

9. Bieger D, Giles SA, Hockman CH. Dopaminergic influences on swallowing. Neuropharmacology. 1977;16:243-252.

10. Bettarello A, Tuttle SG, Grossman MI. Effects of autonomic drugs on gastroesophageal reflux. Gastroenterology. 1960;39:340-346.

11. Fioritti A, Giaccotto L, Melega V. Choking incidents among psychiatric patients: retrospective analysis of thirty-one cases from the west Bologna psychiatric wards. Can J Psychiatry. 1997;42:515-520.

12. Hussar AE, Bragg DG. The effect of chlorpromazine on the swallowing function in schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1969;126:570-573.

13. Abraham B, Alao AO. An unusual body ingestion in a schizophrenic patient: case report. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2005;35(3):313-318.

14. Beecroft N, Bach L, Tunstall N, et al. An unusual case of pica. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998;13(9):638-641.

15. Pawa S, Khalifa AJ, Ehrinpreis MN, et al. Zinc toxicity from massive and prolonged coin ingestion in an adult. Am J Med Sci. 2008;336(5):430-433.

16. Beck DA, Frohberg NR. Coprophagia in an elderly man: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2005;35(4):417-427.

17. Dumaguing NI, Singh I, Sethi M, et al. Pica in the geriatric mentally ill: unrelenting and potentially fatal. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2003;16(3):189-191.

18. Bazemore H, Tonkonogy J, Ananth R. Dysphagia in psychiatric patients: clinical videofluoroscopic study. Dysphagia. 1991;6:62-65.

19. von Brauchitsch H, May W. Deaths from aspiration and asphyxiation in a mental hospital. Arch Gen Psych. 1968;18:129-136.

20. American Red Cross. Treatment for a conscious choking adult. Available at: http://www.redcross.org/flash/brr/English-html/conscious-choking.asp. Accessed August 27, 2010.