User login

CASE: Psychotic and assaultive

Mr. A, age 34, is involuntarily admitted to a psychiatric hospital after assaulting a family member and a police officer. He is charged with 2 counts of first-degree assault. He describes auditory hallucinations and believes God is telling him to refuse medication. One year earlier he was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Mr. A informs hospital staff that he is a Christian Scientist, and his religion precludes him from taking any medications. The local parish of the First Church of Christ, Scientist confirms that he is an active member. One day after admission, Mr. A is threatening and belligerent, and he continues to refuse any treatment.

How would you initially treat Mr. A?a) seek emergency guardianship

b) seek help from the Christian Science community

c) order the appropriate medication to effectively treat his symptoms

TREATMENT: Involuntary treatment

While in the hospital, Mr. A’s psychotic symptoms and aggressive behavior toward the staff and other patients lead to several psychiatric emergencies being declared and involuntary administration of antipsychotic medication. Because IM haloperidol, 5 mg/d, rapidly alleviates his symptoms, there is no need to pursue guardianship. Mr. A asks to meet with a member of the Christian Science community before his discharge, which is arranged. Upon being discharged, Mr. A schedules outpatient treatment at the community mental health center.

The author's observations

Mr. A’s case challenged staff to balance his clinical needs with his religious philosophy. Although psychotic, Mr. A provided a reason for refusing treatment—his belief in Christian Science—which would be considered a valid spiritual choice based on his values. However, his psychiatric symptoms created a dangerous situation for himself and others, which lead to emergency administration of antipsychotics against his will. Resolution of his symptoms did not warrant a petition for guardianship or a long-term involuntary hospitalization (Table 1). Allowing Mr. A to meet with a member of his church was crucial because it validated Mr. A’s religious practices and showed the staff’s willingness to respect his Christian Science beliefs.1,2

Honoring religious beliefs

Christian Science is based on the writings of Mary Baker Eddy and the Bible. Adherents believe that any form of evil, such as sin, disease, or death, is the opposite of God and is an illusion. Health care and treatment within the Christian Science community do not focus on what is wrong with the physical body, but rather what is wrong with the mind. Christian Scientists attempt healing through specific forms of prayer, not conventional methods such as medications or surgery.3 Christian Scientists believe there are no limits to the type of medical conditions that can be healed through prayer. Community members go to Christian Science practitioners for healing via prayer, focusing on the Bible and Mary Baker Eddy’s writings to alleviate their suffering.

The Christian Science church does not forbid its members from receiving conventional medical treatments, although prayer clearly is the preferred method of healing.4 Members can make their own choice about obtaining medical treatment. If they choose medical care, they cannot receive simultaneous treatment from Christian Science practitioners, but they can participate in other church activities. However, members compelled to get medical or psychiatric treatment via a guardianship or a court order can receive concurrent treatment from a Christian Science practitioner.

Other faith traditions generally do not draw such a clear line between medical treatment and religious healing. For example, Jehovah’s Witnesses have no prohibition against obtaining medical care, but they refuse blood transfusions, although they do accept medical alternatives to blood.5

ASSESSMENT: Remorse, reluctance

Mr. A stops taking his medication a few days after discharge, becomes psychotic, assaults his landlord, and is involuntarily readmitted to the hospital. His symptoms again are alleviated with IM haloperidol, 5 mg/d, and Mr. A is remorseful about his behavior while psychotic. He repeats his belief that his illness can be cured with prayer. The staff is reluctant to discharge Mr. A because of his history of nonadherence to treatment and assaultive episodes.

What are the next steps to consider in Mr. A’s treatment?a) seek guardianship because Mr. A does not appreciate the need for treatment

b) obtain a long-term commitment to the hospital with plans to conditionally release Mr. A when he is clinically stable

c) begin treatment with a long-acting injectable antipsychotic

EVALUATION: Next steps

The psychiatrist requests and receives a 3-year commitment for Mr. A from the probate court. The psychiatrist works with Mr. A and the community mental health center clinician to develop a conditional discharge plan in which Mr. A agrees to take medications as prescribed as a condition of his release. Mr. A initially is resistant to this plan. He is allowed to meet frequently with his Christian Science practitioner to discuss ways to continue treatment. Hospital staff supports these meetings, while explaining the importance of adhering to medication and how this will effectively treat his psychotic symptoms. Hospital staff does not negate or minimize Mr. A’s religious beliefs. The Christian Science practitioner allows Mr. A to continue his religious healing while receiving psychiatric care because he is a under court-ordered involuntary commitment. This leads Mr. A to find common ground between his religious beliefs and need for psychiatric treatment. Mr. A maintains his belief that he can be healed by prayer, but agrees to accept medications under the law of the probate commitment. To maximize adherence, he agrees to haloperidol decanoate, a long-acting injectable antipsychotic. He is conditionally discharged to continuing outpatient treatment at the community mental health center.

Mr. A adheres to treatment but begins to develop early signs of tardive dyskinesia (mild lip smacking and some tongue protrusion). Therefore, haloperidol decanoate is discontinued and replaced with oral olanzapine, 20 mg/d. Mr. A is no longer psychotic, and his psychotic symptoms are in remission. He continues to hold fast to his Christian Science beliefs.

One month before the end of his 3-year commitment, Mr. A informs his psychiatrist that he plans to stop his antipsychotic when the commitment ends and to pursue treatment with his Christian Science practitioner via prayer. He wants to prove to everyone that medications are no longer necessary.

What should Mr. A’s treating psychiatrist do?a) immediately readmit Mr. A involuntarily because of his potential dangerousness and impending treatment nonadherence

b) pursue guardianship because Mr. A is incapable of understanding that he has a serious mental illness

c) not pursue legal action but continue to treat Mr. A with antipsychotics and encourage compliance

d) readmit Mr. A to the hospital, request an extension of the commitment order, and consider a medication holiday in a safe setting to address Mr. A’s religious beliefs

OUTCOME: Court-ordered treatment

Mr. A agrees to hospitalization and at a court hearing is committed to the hospital for a period not to exceed 5 years. The judge also orders that Mr. A undergo a period of reducing or stopping his antipsychotic to see if he decompensates. The judicial order states that if it is determined that Mr. A no longer needs medication, the judge may reconsider the terms of the long-term commitment.

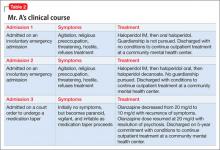

Mr. A, his inpatient and outpatient psychiatrists, and a Christian Science practitioner work together to develop a plan to taper his medication. Over 2 weeks, olanzapine is tapered from 20 mg/d to 10 mg/d. Two weeks into the taper, Mr. A becomes increasingly irritable, paranoid, and vigilant. The staff gives him prompt feedback about his apparent decompensation. Mr. A accepts this. He resumes taking olanzapine, 20 mg/d, and his symptoms resolve. He feels discouraged because taking medication is against his religious values. Nevertheless, he accepts the 5-year commitment as a court-mandated treatment that he must abide by. He is conditionally discharged from the hospital. For a summary of Mr. A’s clinical course, see Table 2.

Mr. A continues to do well in the community. New Hampshire’s law allowing up to a 5-year commitment to the hospital has been effective in maximizing Mr. A’s treatment adherence (Table 3).6 He has not been rehospitalized and his psychotic symptoms are in remission. Mr. A still believes his symptoms can be best treated with Christian Science prayer, but sees the state-imposed conditional discharge as a necessary “evil” that he must adhere to. He continues to be an active member of his church.

The author's observations

With the support of his outpatient and inpatient psychiatrists, treatment teams, and Christian Science practitioner, Mr. A has successfully integrated 2 seemingly opposing views regarding treatment, allowing him to live successfully in the community.

From this case, we learned that clinicians:

- need to understand patients’ religious beliefs and how these beliefs can impact their care

- must be aware that caring for patients from different religious traditions may present unique treatment challenges

- need to put their personal views regarding a patient’s religious beliefs aside and work with the patient to alleviate suffering

- must give patients ample opportunity to meet with their faith community, allowing adequate time for discussion and problem solving

Bottom Line

Balancing a patient’s clinical and spiritual needs can be challenging when those needs seem mutually exclusive. Clear communication, legal guidance, careful planning, and a strong therapeutic alliance can create opportunities for the patient to make both needs work to his advantage.

Related Resources

- Christian Science. www.christianscience.com.

- de Nesnera A, Vidaver RM. New Hampshire’s commitment law: treatment implications. New Hampshire Bar Journal. 2007;48(2):68-73.

- Ehman J. Religious diversity: practical points for health care

providers: www.uphs.upenn.edu/pastoral/resed/diversity_points.html.

Drug Brand Names

Haloperidol • Haldol

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Disclosure

Dr. de Nesnera reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Pavlo AM, Bursztajn H, Gutheil T. Christian Science and competence to make treatment choices: clinical challenges in assessing values. Int J Law Psych. 1987;10(4):395-401.

2. Pavlo AM, Bursztajn H, Gutheil T, et al. Weighing religious beliefs in determining competence. Hosp Comm Psych. 1987;38(4):350-352.

3. Eddy MB. Science and health with key to the scriptures. Boston, MA: Christian Science Publishing Company; 1875:1-17.

4. Eddy M. Science and health with key to the scriptures. Boston, MA: Christian Science Publishing Company; 1875: 167.

5. The growing demand for bloodless medicine and surgery. Awake! January 8, 2000:4-6. http://wol.jw.org/en/wol/d/r1/lp-e/102000003. Accessed June 4, 2013.

6. NH Rev Stat Ann § 135-C:27-46.

CASE: Psychotic and assaultive

Mr. A, age 34, is involuntarily admitted to a psychiatric hospital after assaulting a family member and a police officer. He is charged with 2 counts of first-degree assault. He describes auditory hallucinations and believes God is telling him to refuse medication. One year earlier he was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Mr. A informs hospital staff that he is a Christian Scientist, and his religion precludes him from taking any medications. The local parish of the First Church of Christ, Scientist confirms that he is an active member. One day after admission, Mr. A is threatening and belligerent, and he continues to refuse any treatment.

How would you initially treat Mr. A?a) seek emergency guardianship

b) seek help from the Christian Science community

c) order the appropriate medication to effectively treat his symptoms

TREATMENT: Involuntary treatment

While in the hospital, Mr. A’s psychotic symptoms and aggressive behavior toward the staff and other patients lead to several psychiatric emergencies being declared and involuntary administration of antipsychotic medication. Because IM haloperidol, 5 mg/d, rapidly alleviates his symptoms, there is no need to pursue guardianship. Mr. A asks to meet with a member of the Christian Science community before his discharge, which is arranged. Upon being discharged, Mr. A schedules outpatient treatment at the community mental health center.

The author's observations

Mr. A’s case challenged staff to balance his clinical needs with his religious philosophy. Although psychotic, Mr. A provided a reason for refusing treatment—his belief in Christian Science—which would be considered a valid spiritual choice based on his values. However, his psychiatric symptoms created a dangerous situation for himself and others, which lead to emergency administration of antipsychotics against his will. Resolution of his symptoms did not warrant a petition for guardianship or a long-term involuntary hospitalization (Table 1). Allowing Mr. A to meet with a member of his church was crucial because it validated Mr. A’s religious practices and showed the staff’s willingness to respect his Christian Science beliefs.1,2

Honoring religious beliefs

Christian Science is based on the writings of Mary Baker Eddy and the Bible. Adherents believe that any form of evil, such as sin, disease, or death, is the opposite of God and is an illusion. Health care and treatment within the Christian Science community do not focus on what is wrong with the physical body, but rather what is wrong with the mind. Christian Scientists attempt healing through specific forms of prayer, not conventional methods such as medications or surgery.3 Christian Scientists believe there are no limits to the type of medical conditions that can be healed through prayer. Community members go to Christian Science practitioners for healing via prayer, focusing on the Bible and Mary Baker Eddy’s writings to alleviate their suffering.

The Christian Science church does not forbid its members from receiving conventional medical treatments, although prayer clearly is the preferred method of healing.4 Members can make their own choice about obtaining medical treatment. If they choose medical care, they cannot receive simultaneous treatment from Christian Science practitioners, but they can participate in other church activities. However, members compelled to get medical or psychiatric treatment via a guardianship or a court order can receive concurrent treatment from a Christian Science practitioner.

Other faith traditions generally do not draw such a clear line between medical treatment and religious healing. For example, Jehovah’s Witnesses have no prohibition against obtaining medical care, but they refuse blood transfusions, although they do accept medical alternatives to blood.5

ASSESSMENT: Remorse, reluctance

Mr. A stops taking his medication a few days after discharge, becomes psychotic, assaults his landlord, and is involuntarily readmitted to the hospital. His symptoms again are alleviated with IM haloperidol, 5 mg/d, and Mr. A is remorseful about his behavior while psychotic. He repeats his belief that his illness can be cured with prayer. The staff is reluctant to discharge Mr. A because of his history of nonadherence to treatment and assaultive episodes.

What are the next steps to consider in Mr. A’s treatment?a) seek guardianship because Mr. A does not appreciate the need for treatment

b) obtain a long-term commitment to the hospital with plans to conditionally release Mr. A when he is clinically stable

c) begin treatment with a long-acting injectable antipsychotic

EVALUATION: Next steps

The psychiatrist requests and receives a 3-year commitment for Mr. A from the probate court. The psychiatrist works with Mr. A and the community mental health center clinician to develop a conditional discharge plan in which Mr. A agrees to take medications as prescribed as a condition of his release. Mr. A initially is resistant to this plan. He is allowed to meet frequently with his Christian Science practitioner to discuss ways to continue treatment. Hospital staff supports these meetings, while explaining the importance of adhering to medication and how this will effectively treat his psychotic symptoms. Hospital staff does not negate or minimize Mr. A’s religious beliefs. The Christian Science practitioner allows Mr. A to continue his religious healing while receiving psychiatric care because he is a under court-ordered involuntary commitment. This leads Mr. A to find common ground between his religious beliefs and need for psychiatric treatment. Mr. A maintains his belief that he can be healed by prayer, but agrees to accept medications under the law of the probate commitment. To maximize adherence, he agrees to haloperidol decanoate, a long-acting injectable antipsychotic. He is conditionally discharged to continuing outpatient treatment at the community mental health center.

Mr. A adheres to treatment but begins to develop early signs of tardive dyskinesia (mild lip smacking and some tongue protrusion). Therefore, haloperidol decanoate is discontinued and replaced with oral olanzapine, 20 mg/d. Mr. A is no longer psychotic, and his psychotic symptoms are in remission. He continues to hold fast to his Christian Science beliefs.

One month before the end of his 3-year commitment, Mr. A informs his psychiatrist that he plans to stop his antipsychotic when the commitment ends and to pursue treatment with his Christian Science practitioner via prayer. He wants to prove to everyone that medications are no longer necessary.

What should Mr. A’s treating psychiatrist do?a) immediately readmit Mr. A involuntarily because of his potential dangerousness and impending treatment nonadherence

b) pursue guardianship because Mr. A is incapable of understanding that he has a serious mental illness

c) not pursue legal action but continue to treat Mr. A with antipsychotics and encourage compliance

d) readmit Mr. A to the hospital, request an extension of the commitment order, and consider a medication holiday in a safe setting to address Mr. A’s religious beliefs

OUTCOME: Court-ordered treatment

Mr. A agrees to hospitalization and at a court hearing is committed to the hospital for a period not to exceed 5 years. The judge also orders that Mr. A undergo a period of reducing or stopping his antipsychotic to see if he decompensates. The judicial order states that if it is determined that Mr. A no longer needs medication, the judge may reconsider the terms of the long-term commitment.

Mr. A, his inpatient and outpatient psychiatrists, and a Christian Science practitioner work together to develop a plan to taper his medication. Over 2 weeks, olanzapine is tapered from 20 mg/d to 10 mg/d. Two weeks into the taper, Mr. A becomes increasingly irritable, paranoid, and vigilant. The staff gives him prompt feedback about his apparent decompensation. Mr. A accepts this. He resumes taking olanzapine, 20 mg/d, and his symptoms resolve. He feels discouraged because taking medication is against his religious values. Nevertheless, he accepts the 5-year commitment as a court-mandated treatment that he must abide by. He is conditionally discharged from the hospital. For a summary of Mr. A’s clinical course, see Table 2.

Mr. A continues to do well in the community. New Hampshire’s law allowing up to a 5-year commitment to the hospital has been effective in maximizing Mr. A’s treatment adherence (Table 3).6 He has not been rehospitalized and his psychotic symptoms are in remission. Mr. A still believes his symptoms can be best treated with Christian Science prayer, but sees the state-imposed conditional discharge as a necessary “evil” that he must adhere to. He continues to be an active member of his church.

The author's observations

With the support of his outpatient and inpatient psychiatrists, treatment teams, and Christian Science practitioner, Mr. A has successfully integrated 2 seemingly opposing views regarding treatment, allowing him to live successfully in the community.

From this case, we learned that clinicians:

- need to understand patients’ religious beliefs and how these beliefs can impact their care

- must be aware that caring for patients from different religious traditions may present unique treatment challenges

- need to put their personal views regarding a patient’s religious beliefs aside and work with the patient to alleviate suffering

- must give patients ample opportunity to meet with their faith community, allowing adequate time for discussion and problem solving

Bottom Line

Balancing a patient’s clinical and spiritual needs can be challenging when those needs seem mutually exclusive. Clear communication, legal guidance, careful planning, and a strong therapeutic alliance can create opportunities for the patient to make both needs work to his advantage.

Related Resources

- Christian Science. www.christianscience.com.

- de Nesnera A, Vidaver RM. New Hampshire’s commitment law: treatment implications. New Hampshire Bar Journal. 2007;48(2):68-73.

- Ehman J. Religious diversity: practical points for health care

providers: www.uphs.upenn.edu/pastoral/resed/diversity_points.html.

Drug Brand Names

Haloperidol • Haldol

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Disclosure

Dr. de Nesnera reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE: Psychotic and assaultive

Mr. A, age 34, is involuntarily admitted to a psychiatric hospital after assaulting a family member and a police officer. He is charged with 2 counts of first-degree assault. He describes auditory hallucinations and believes God is telling him to refuse medication. One year earlier he was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Mr. A informs hospital staff that he is a Christian Scientist, and his religion precludes him from taking any medications. The local parish of the First Church of Christ, Scientist confirms that he is an active member. One day after admission, Mr. A is threatening and belligerent, and he continues to refuse any treatment.

How would you initially treat Mr. A?a) seek emergency guardianship

b) seek help from the Christian Science community

c) order the appropriate medication to effectively treat his symptoms

TREATMENT: Involuntary treatment

While in the hospital, Mr. A’s psychotic symptoms and aggressive behavior toward the staff and other patients lead to several psychiatric emergencies being declared and involuntary administration of antipsychotic medication. Because IM haloperidol, 5 mg/d, rapidly alleviates his symptoms, there is no need to pursue guardianship. Mr. A asks to meet with a member of the Christian Science community before his discharge, which is arranged. Upon being discharged, Mr. A schedules outpatient treatment at the community mental health center.

The author's observations

Mr. A’s case challenged staff to balance his clinical needs with his religious philosophy. Although psychotic, Mr. A provided a reason for refusing treatment—his belief in Christian Science—which would be considered a valid spiritual choice based on his values. However, his psychiatric symptoms created a dangerous situation for himself and others, which lead to emergency administration of antipsychotics against his will. Resolution of his symptoms did not warrant a petition for guardianship or a long-term involuntary hospitalization (Table 1). Allowing Mr. A to meet with a member of his church was crucial because it validated Mr. A’s religious practices and showed the staff’s willingness to respect his Christian Science beliefs.1,2

Honoring religious beliefs

Christian Science is based on the writings of Mary Baker Eddy and the Bible. Adherents believe that any form of evil, such as sin, disease, or death, is the opposite of God and is an illusion. Health care and treatment within the Christian Science community do not focus on what is wrong with the physical body, but rather what is wrong with the mind. Christian Scientists attempt healing through specific forms of prayer, not conventional methods such as medications or surgery.3 Christian Scientists believe there are no limits to the type of medical conditions that can be healed through prayer. Community members go to Christian Science practitioners for healing via prayer, focusing on the Bible and Mary Baker Eddy’s writings to alleviate their suffering.

The Christian Science church does not forbid its members from receiving conventional medical treatments, although prayer clearly is the preferred method of healing.4 Members can make their own choice about obtaining medical treatment. If they choose medical care, they cannot receive simultaneous treatment from Christian Science practitioners, but they can participate in other church activities. However, members compelled to get medical or psychiatric treatment via a guardianship or a court order can receive concurrent treatment from a Christian Science practitioner.

Other faith traditions generally do not draw such a clear line between medical treatment and religious healing. For example, Jehovah’s Witnesses have no prohibition against obtaining medical care, but they refuse blood transfusions, although they do accept medical alternatives to blood.5

ASSESSMENT: Remorse, reluctance

Mr. A stops taking his medication a few days after discharge, becomes psychotic, assaults his landlord, and is involuntarily readmitted to the hospital. His symptoms again are alleviated with IM haloperidol, 5 mg/d, and Mr. A is remorseful about his behavior while psychotic. He repeats his belief that his illness can be cured with prayer. The staff is reluctant to discharge Mr. A because of his history of nonadherence to treatment and assaultive episodes.

What are the next steps to consider in Mr. A’s treatment?a) seek guardianship because Mr. A does not appreciate the need for treatment

b) obtain a long-term commitment to the hospital with plans to conditionally release Mr. A when he is clinically stable

c) begin treatment with a long-acting injectable antipsychotic

EVALUATION: Next steps

The psychiatrist requests and receives a 3-year commitment for Mr. A from the probate court. The psychiatrist works with Mr. A and the community mental health center clinician to develop a conditional discharge plan in which Mr. A agrees to take medications as prescribed as a condition of his release. Mr. A initially is resistant to this plan. He is allowed to meet frequently with his Christian Science practitioner to discuss ways to continue treatment. Hospital staff supports these meetings, while explaining the importance of adhering to medication and how this will effectively treat his psychotic symptoms. Hospital staff does not negate or minimize Mr. A’s religious beliefs. The Christian Science practitioner allows Mr. A to continue his religious healing while receiving psychiatric care because he is a under court-ordered involuntary commitment. This leads Mr. A to find common ground between his religious beliefs and need for psychiatric treatment. Mr. A maintains his belief that he can be healed by prayer, but agrees to accept medications under the law of the probate commitment. To maximize adherence, he agrees to haloperidol decanoate, a long-acting injectable antipsychotic. He is conditionally discharged to continuing outpatient treatment at the community mental health center.

Mr. A adheres to treatment but begins to develop early signs of tardive dyskinesia (mild lip smacking and some tongue protrusion). Therefore, haloperidol decanoate is discontinued and replaced with oral olanzapine, 20 mg/d. Mr. A is no longer psychotic, and his psychotic symptoms are in remission. He continues to hold fast to his Christian Science beliefs.

One month before the end of his 3-year commitment, Mr. A informs his psychiatrist that he plans to stop his antipsychotic when the commitment ends and to pursue treatment with his Christian Science practitioner via prayer. He wants to prove to everyone that medications are no longer necessary.

What should Mr. A’s treating psychiatrist do?a) immediately readmit Mr. A involuntarily because of his potential dangerousness and impending treatment nonadherence

b) pursue guardianship because Mr. A is incapable of understanding that he has a serious mental illness

c) not pursue legal action but continue to treat Mr. A with antipsychotics and encourage compliance

d) readmit Mr. A to the hospital, request an extension of the commitment order, and consider a medication holiday in a safe setting to address Mr. A’s religious beliefs

OUTCOME: Court-ordered treatment

Mr. A agrees to hospitalization and at a court hearing is committed to the hospital for a period not to exceed 5 years. The judge also orders that Mr. A undergo a period of reducing or stopping his antipsychotic to see if he decompensates. The judicial order states that if it is determined that Mr. A no longer needs medication, the judge may reconsider the terms of the long-term commitment.

Mr. A, his inpatient and outpatient psychiatrists, and a Christian Science practitioner work together to develop a plan to taper his medication. Over 2 weeks, olanzapine is tapered from 20 mg/d to 10 mg/d. Two weeks into the taper, Mr. A becomes increasingly irritable, paranoid, and vigilant. The staff gives him prompt feedback about his apparent decompensation. Mr. A accepts this. He resumes taking olanzapine, 20 mg/d, and his symptoms resolve. He feels discouraged because taking medication is against his religious values. Nevertheless, he accepts the 5-year commitment as a court-mandated treatment that he must abide by. He is conditionally discharged from the hospital. For a summary of Mr. A’s clinical course, see Table 2.

Mr. A continues to do well in the community. New Hampshire’s law allowing up to a 5-year commitment to the hospital has been effective in maximizing Mr. A’s treatment adherence (Table 3).6 He has not been rehospitalized and his psychotic symptoms are in remission. Mr. A still believes his symptoms can be best treated with Christian Science prayer, but sees the state-imposed conditional discharge as a necessary “evil” that he must adhere to. He continues to be an active member of his church.

The author's observations

With the support of his outpatient and inpatient psychiatrists, treatment teams, and Christian Science practitioner, Mr. A has successfully integrated 2 seemingly opposing views regarding treatment, allowing him to live successfully in the community.

From this case, we learned that clinicians:

- need to understand patients’ religious beliefs and how these beliefs can impact their care

- must be aware that caring for patients from different religious traditions may present unique treatment challenges

- need to put their personal views regarding a patient’s religious beliefs aside and work with the patient to alleviate suffering

- must give patients ample opportunity to meet with their faith community, allowing adequate time for discussion and problem solving

Bottom Line

Balancing a patient’s clinical and spiritual needs can be challenging when those needs seem mutually exclusive. Clear communication, legal guidance, careful planning, and a strong therapeutic alliance can create opportunities for the patient to make both needs work to his advantage.

Related Resources

- Christian Science. www.christianscience.com.

- de Nesnera A, Vidaver RM. New Hampshire’s commitment law: treatment implications. New Hampshire Bar Journal. 2007;48(2):68-73.

- Ehman J. Religious diversity: practical points for health care

providers: www.uphs.upenn.edu/pastoral/resed/diversity_points.html.

Drug Brand Names

Haloperidol • Haldol

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Disclosure

Dr. de Nesnera reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Pavlo AM, Bursztajn H, Gutheil T. Christian Science and competence to make treatment choices: clinical challenges in assessing values. Int J Law Psych. 1987;10(4):395-401.

2. Pavlo AM, Bursztajn H, Gutheil T, et al. Weighing religious beliefs in determining competence. Hosp Comm Psych. 1987;38(4):350-352.

3. Eddy MB. Science and health with key to the scriptures. Boston, MA: Christian Science Publishing Company; 1875:1-17.

4. Eddy M. Science and health with key to the scriptures. Boston, MA: Christian Science Publishing Company; 1875: 167.

5. The growing demand for bloodless medicine and surgery. Awake! January 8, 2000:4-6. http://wol.jw.org/en/wol/d/r1/lp-e/102000003. Accessed June 4, 2013.

6. NH Rev Stat Ann § 135-C:27-46.

1. Pavlo AM, Bursztajn H, Gutheil T. Christian Science and competence to make treatment choices: clinical challenges in assessing values. Int J Law Psych. 1987;10(4):395-401.

2. Pavlo AM, Bursztajn H, Gutheil T, et al. Weighing religious beliefs in determining competence. Hosp Comm Psych. 1987;38(4):350-352.

3. Eddy MB. Science and health with key to the scriptures. Boston, MA: Christian Science Publishing Company; 1875:1-17.

4. Eddy M. Science and health with key to the scriptures. Boston, MA: Christian Science Publishing Company; 1875: 167.

5. The growing demand for bloodless medicine and surgery. Awake! January 8, 2000:4-6. http://wol.jw.org/en/wol/d/r1/lp-e/102000003. Accessed June 4, 2013.

6. NH Rev Stat Ann § 135-C:27-46.