User login

Get ready for high-sensitivity troponin tests in the ED

SAN DIEGO – The rule-in cutoff level for high-sensitivity cardiac troponin measures in the diagnosis of acute MI have been established by the European Society of Cardiology, but the value might not be applicable to a U.S. population.

In a video interview at the annual scientific assembly of the American College of Emergency Physicians, Richard M. Nowak, MD, of the department of emergency medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, explains why the rule-in cutoff is not likely to apply to American patients and may be associated with a higher risk of false positives.

Since high-sensitivity troponin measures will soon be coming to every ED, each institution may have to arrive at their own rule-in cutoff value in order to diagnose acute MI with an acceptable number of false positives, he said. Dr. Nowak explains how to begin addressing that process.

SAN DIEGO – The rule-in cutoff level for high-sensitivity cardiac troponin measures in the diagnosis of acute MI have been established by the European Society of Cardiology, but the value might not be applicable to a U.S. population.

In a video interview at the annual scientific assembly of the American College of Emergency Physicians, Richard M. Nowak, MD, of the department of emergency medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, explains why the rule-in cutoff is not likely to apply to American patients and may be associated with a higher risk of false positives.

Since high-sensitivity troponin measures will soon be coming to every ED, each institution may have to arrive at their own rule-in cutoff value in order to diagnose acute MI with an acceptable number of false positives, he said. Dr. Nowak explains how to begin addressing that process.

SAN DIEGO – The rule-in cutoff level for high-sensitivity cardiac troponin measures in the diagnosis of acute MI have been established by the European Society of Cardiology, but the value might not be applicable to a U.S. population.

In a video interview at the annual scientific assembly of the American College of Emergency Physicians, Richard M. Nowak, MD, of the department of emergency medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, explains why the rule-in cutoff is not likely to apply to American patients and may be associated with a higher risk of false positives.

Since high-sensitivity troponin measures will soon be coming to every ED, each institution may have to arrive at their own rule-in cutoff value in order to diagnose acute MI with an acceptable number of false positives, he said. Dr. Nowak explains how to begin addressing that process.

REPORTING FROM ACEP18

How to manage difficult dislocations

SAN DIEGO – Being prepared to manage difficult dislocations is key to maintaining the flow of patient care in any emergency department.

In a video interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians, Danielle D. Campagne, MD, FACEP, shared her clinical pearls for managing dislocations of the jaw, hip, ankle, and shoulder.

Dr. Campagne is an emergency medicine physician who practices at Community Regional Medical Center in Fresno, Calif. She is also vice chief of emergency medicine at University of California, San Francisco, Fresno. She reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Being prepared to manage difficult dislocations is key to maintaining the flow of patient care in any emergency department.

In a video interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians, Danielle D. Campagne, MD, FACEP, shared her clinical pearls for managing dislocations of the jaw, hip, ankle, and shoulder.

Dr. Campagne is an emergency medicine physician who practices at Community Regional Medical Center in Fresno, Calif. She is also vice chief of emergency medicine at University of California, San Francisco, Fresno. She reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Being prepared to manage difficult dislocations is key to maintaining the flow of patient care in any emergency department.

In a video interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians, Danielle D. Campagne, MD, FACEP, shared her clinical pearls for managing dislocations of the jaw, hip, ankle, and shoulder.

Dr. Campagne is an emergency medicine physician who practices at Community Regional Medical Center in Fresno, Calif. She is also vice chief of emergency medicine at University of California, San Francisco, Fresno. She reported having no financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM ACEP18

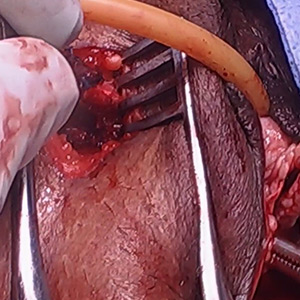

Vaginal and bilateral thigh removal of a transobturator sling

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

- Morcellation at the time of vaginal hysterectomy

- Surgical management of non-tubal ectopic pregnancies

- Size can matter: Laparoscopic hysterectomy for the very large uterus

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

- Morcellation at the time of vaginal hysterectomy

- Surgical management of non-tubal ectopic pregnancies

- Size can matter: Laparoscopic hysterectomy for the very large uterus

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

- Morcellation at the time of vaginal hysterectomy

- Surgical management of non-tubal ectopic pregnancies

- Size can matter: Laparoscopic hysterectomy for the very large uterus

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

This video is brought to you by

Swings in four metabolic measures predicted death in healthy people

, based on data from a 5.5-year population-based study in Korea.

In a model adjusted for age, sex, smoking, alcohol consumption, regular exercise, and income status the group with high variability for all four parameters had a significantly higher risk for all-cause mortality (hazard ratio, 2.27; 95% confidence interval, 2.13-2.42), for MI (HR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.25-1.64), and for stroke (HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.25-1.60), compared with the group with low variability for all four parameters. The association with risk was graded and persisted after multivariable adjustment.

“Variability in metabolic parameters may be prognostic surrogate markers for predicting mortality and cardiovascular outcomes,” wrote senior author Seung-Hwan Lee, MD, PhD, and professor of endocrinology at the College of Medicine of the Catholic University of Korea in Seoul, South Korea, and colleagues. “High variability in metabolic parameters (may be) associated with adverse health outcomes not only in a diseased population, but also in the relatively healthy population although the mechanism could be somewhat different.”

Korea has a single-payer system, the Korean National Health Insurance system, that includes health information on its entire population. The researchers selected data from 6,748,773 people who were free of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, and who underwent three or more health examinations during 2005-2012 that documented body mass index (BMI), fasting blood glucose, systolic blood pressure, and total cholesterol. Participants were followed to the end of 2015, for a median follow-up of 5.5 years. There were 54,785 deaths (0.8%), 22,498 cases of stroke (0.3%), and 21,452 MIs (0.3%).

The research team defined high variability as the highest quartile, classifying participants according to the number of high-variability parameters. A score of 4 indicated high variability in all four metabolic parameters – body weight, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, and fasting blood glucose.

In the highest quartile in fasting blood glucose variability, compared with the lowest quartile, the risk of all-cause mortality increased by 20% (HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.18-1.23), MI by 16% (HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.12-1.21), and stroke by 13% (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.09-1.17).

For the highest quartile in total cholesterol variability, compared with the lowest quartile, the risk of all-cause mortality increased by 31% (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.28-1.34), MI by 10% (HR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.06-1.14), and stroke by 6% (HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.03-1.10).

For the highest quartile in systolic BP variability, compared with the lowest quartile, the risk of all-cause mortality increased by 19% (HR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.16-1.22), MI by 7% (HR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.03-1.11), and stroke by 14% (HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.10-1.18).

For the highest quartile in BMI variability, compared with the lowest quartile, the risk of all-cause mortality increased by 53% (HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.50-1.57), MI by 14% (HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.09-1.18), and stroke by 14% (HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.10-1.18).

“It is not certain whether these results from Korea would apply to the United States. However, several previous studies on variability were performed in other populations, suggesting that it is likely to be a common phenomenon,” the authors wrote.

The study was supported in part by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government. The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

SOURCE: Lee S-H et al. Circulation. 2018 Oct.

, based on data from a 5.5-year population-based study in Korea.

In a model adjusted for age, sex, smoking, alcohol consumption, regular exercise, and income status the group with high variability for all four parameters had a significantly higher risk for all-cause mortality (hazard ratio, 2.27; 95% confidence interval, 2.13-2.42), for MI (HR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.25-1.64), and for stroke (HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.25-1.60), compared with the group with low variability for all four parameters. The association with risk was graded and persisted after multivariable adjustment.

“Variability in metabolic parameters may be prognostic surrogate markers for predicting mortality and cardiovascular outcomes,” wrote senior author Seung-Hwan Lee, MD, PhD, and professor of endocrinology at the College of Medicine of the Catholic University of Korea in Seoul, South Korea, and colleagues. “High variability in metabolic parameters (may be) associated with adverse health outcomes not only in a diseased population, but also in the relatively healthy population although the mechanism could be somewhat different.”

Korea has a single-payer system, the Korean National Health Insurance system, that includes health information on its entire population. The researchers selected data from 6,748,773 people who were free of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, and who underwent three or more health examinations during 2005-2012 that documented body mass index (BMI), fasting blood glucose, systolic blood pressure, and total cholesterol. Participants were followed to the end of 2015, for a median follow-up of 5.5 years. There were 54,785 deaths (0.8%), 22,498 cases of stroke (0.3%), and 21,452 MIs (0.3%).

The research team defined high variability as the highest quartile, classifying participants according to the number of high-variability parameters. A score of 4 indicated high variability in all four metabolic parameters – body weight, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, and fasting blood glucose.

In the highest quartile in fasting blood glucose variability, compared with the lowest quartile, the risk of all-cause mortality increased by 20% (HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.18-1.23), MI by 16% (HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.12-1.21), and stroke by 13% (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.09-1.17).

For the highest quartile in total cholesterol variability, compared with the lowest quartile, the risk of all-cause mortality increased by 31% (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.28-1.34), MI by 10% (HR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.06-1.14), and stroke by 6% (HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.03-1.10).

For the highest quartile in systolic BP variability, compared with the lowest quartile, the risk of all-cause mortality increased by 19% (HR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.16-1.22), MI by 7% (HR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.03-1.11), and stroke by 14% (HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.10-1.18).

For the highest quartile in BMI variability, compared with the lowest quartile, the risk of all-cause mortality increased by 53% (HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.50-1.57), MI by 14% (HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.09-1.18), and stroke by 14% (HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.10-1.18).

“It is not certain whether these results from Korea would apply to the United States. However, several previous studies on variability were performed in other populations, suggesting that it is likely to be a common phenomenon,” the authors wrote.

The study was supported in part by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government. The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

SOURCE: Lee S-H et al. Circulation. 2018 Oct.

, based on data from a 5.5-year population-based study in Korea.

In a model adjusted for age, sex, smoking, alcohol consumption, regular exercise, and income status the group with high variability for all four parameters had a significantly higher risk for all-cause mortality (hazard ratio, 2.27; 95% confidence interval, 2.13-2.42), for MI (HR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.25-1.64), and for stroke (HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.25-1.60), compared with the group with low variability for all four parameters. The association with risk was graded and persisted after multivariable adjustment.

“Variability in metabolic parameters may be prognostic surrogate markers for predicting mortality and cardiovascular outcomes,” wrote senior author Seung-Hwan Lee, MD, PhD, and professor of endocrinology at the College of Medicine of the Catholic University of Korea in Seoul, South Korea, and colleagues. “High variability in metabolic parameters (may be) associated with adverse health outcomes not only in a diseased population, but also in the relatively healthy population although the mechanism could be somewhat different.”

Korea has a single-payer system, the Korean National Health Insurance system, that includes health information on its entire population. The researchers selected data from 6,748,773 people who were free of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, and who underwent three or more health examinations during 2005-2012 that documented body mass index (BMI), fasting blood glucose, systolic blood pressure, and total cholesterol. Participants were followed to the end of 2015, for a median follow-up of 5.5 years. There were 54,785 deaths (0.8%), 22,498 cases of stroke (0.3%), and 21,452 MIs (0.3%).

The research team defined high variability as the highest quartile, classifying participants according to the number of high-variability parameters. A score of 4 indicated high variability in all four metabolic parameters – body weight, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, and fasting blood glucose.

In the highest quartile in fasting blood glucose variability, compared with the lowest quartile, the risk of all-cause mortality increased by 20% (HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.18-1.23), MI by 16% (HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.12-1.21), and stroke by 13% (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.09-1.17).

For the highest quartile in total cholesterol variability, compared with the lowest quartile, the risk of all-cause mortality increased by 31% (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.28-1.34), MI by 10% (HR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.06-1.14), and stroke by 6% (HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.03-1.10).

For the highest quartile in systolic BP variability, compared with the lowest quartile, the risk of all-cause mortality increased by 19% (HR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.16-1.22), MI by 7% (HR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.03-1.11), and stroke by 14% (HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.10-1.18).

For the highest quartile in BMI variability, compared with the lowest quartile, the risk of all-cause mortality increased by 53% (HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.50-1.57), MI by 14% (HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.09-1.18), and stroke by 14% (HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.10-1.18).

“It is not certain whether these results from Korea would apply to the United States. However, several previous studies on variability were performed in other populations, suggesting that it is likely to be a common phenomenon,” the authors wrote.

The study was supported in part by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government. The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

SOURCE: Lee S-H et al. Circulation. 2018 Oct.

FROM CIRCULATION

Key clinical point: Fluctuations in fasting glucose and cholesterol levels, systolic blood pressure, and body mass index are associated with a higher risk for all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, and stroke in otherwise healthy people.

Major finding: The hazard ratios were 2.27 (95% CI, 2.13-2.42) for all-cause mortality, 1.43 (95% CI, 1.25-1.64) for MI, and 1.41 (95% CI, 1.25-1.60) for stroke.

Study details: An observational population-based study involving more than 6.7 million Koreans age 20 and older.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea. The authors had no relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Source: Lee S-H et al. Circulation. 2018 Oct.

Get on top of home BP monitoring now

CHICAGO – Home BP monitoring has proved its worth, and it’s now time to integrate it into health care and get insurers to pay for it, according to Hayden Bosworth, PhD, a population health sciences professor and health services researcher at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

The devices are on the shelves of pharmacies and discount stores nationwide, sometimes for less than $50, but what to do with them in the clinic hasn’t been worked out. It’s likely patients are soon going to want help interpreting the results, if they aren’t already, but a leap in technology has left clinicians and payors scratching their heads.

There’s more than enough evidence of benefit. Dr. Bosworth has been involved with several trials of home BP monitoring with good results. He was one of the many authors on a recent meta-analysis that found when patients check their BP at home, it can lead to a “clinically significant” reduction “which persists for at least 12 months” (PLoS Med. 2017 Sep 19;14[9]:e1002389).

“Are we talking about efficacy or proof of concept? I think we are beyond that. Now we have to think about how we put it into the system, how do we integrate it, what’s the best way of delivery. I think that’s where the future is,” he said in an interview at the joint scientific sessions of the American Heart Association Council on Hypertension, AHA Council on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, and American Society of Hypertension.

Home monitoring came up far more often at this year’s joint sessions than in 2017, which might indicate growing interest, but reimbursement remains a challenge. American Medical Association staff said at this year’s meeting that they are working with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for coverage of the devices and their use. It seemed likely to them.

In the meantime, Dr. Bosworth had some useful advice for those who are thinking about incorporating home BP monitoring into their practices.

He shared his tips on how to pick out a device – there’s actually a journal called Blood Pressure Monitoring that can help – as well as his thoughts on how often people should monitor themselves and what to do with the numbers.

He envisions a future when patients routinely check their BP at home; it’s even possible they could adjust their medications based on the results, much like diabetes patients track their blood glucose and adjust their insulin. It’s been shown to work in Britain (JAMA. 2014 Aug 27;312[8]:799-808).

Dr. Bosworth reported no relevant disclosures.

CHICAGO – Home BP monitoring has proved its worth, and it’s now time to integrate it into health care and get insurers to pay for it, according to Hayden Bosworth, PhD, a population health sciences professor and health services researcher at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

The devices are on the shelves of pharmacies and discount stores nationwide, sometimes for less than $50, but what to do with them in the clinic hasn’t been worked out. It’s likely patients are soon going to want help interpreting the results, if they aren’t already, but a leap in technology has left clinicians and payors scratching their heads.

There’s more than enough evidence of benefit. Dr. Bosworth has been involved with several trials of home BP monitoring with good results. He was one of the many authors on a recent meta-analysis that found when patients check their BP at home, it can lead to a “clinically significant” reduction “which persists for at least 12 months” (PLoS Med. 2017 Sep 19;14[9]:e1002389).

“Are we talking about efficacy or proof of concept? I think we are beyond that. Now we have to think about how we put it into the system, how do we integrate it, what’s the best way of delivery. I think that’s where the future is,” he said in an interview at the joint scientific sessions of the American Heart Association Council on Hypertension, AHA Council on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, and American Society of Hypertension.

Home monitoring came up far more often at this year’s joint sessions than in 2017, which might indicate growing interest, but reimbursement remains a challenge. American Medical Association staff said at this year’s meeting that they are working with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for coverage of the devices and their use. It seemed likely to them.

In the meantime, Dr. Bosworth had some useful advice for those who are thinking about incorporating home BP monitoring into their practices.

He shared his tips on how to pick out a device – there’s actually a journal called Blood Pressure Monitoring that can help – as well as his thoughts on how often people should monitor themselves and what to do with the numbers.

He envisions a future when patients routinely check their BP at home; it’s even possible they could adjust their medications based on the results, much like diabetes patients track their blood glucose and adjust their insulin. It’s been shown to work in Britain (JAMA. 2014 Aug 27;312[8]:799-808).

Dr. Bosworth reported no relevant disclosures.

CHICAGO – Home BP monitoring has proved its worth, and it’s now time to integrate it into health care and get insurers to pay for it, according to Hayden Bosworth, PhD, a population health sciences professor and health services researcher at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

The devices are on the shelves of pharmacies and discount stores nationwide, sometimes for less than $50, but what to do with them in the clinic hasn’t been worked out. It’s likely patients are soon going to want help interpreting the results, if they aren’t already, but a leap in technology has left clinicians and payors scratching their heads.

There’s more than enough evidence of benefit. Dr. Bosworth has been involved with several trials of home BP monitoring with good results. He was one of the many authors on a recent meta-analysis that found when patients check their BP at home, it can lead to a “clinically significant” reduction “which persists for at least 12 months” (PLoS Med. 2017 Sep 19;14[9]:e1002389).

“Are we talking about efficacy or proof of concept? I think we are beyond that. Now we have to think about how we put it into the system, how do we integrate it, what’s the best way of delivery. I think that’s where the future is,” he said in an interview at the joint scientific sessions of the American Heart Association Council on Hypertension, AHA Council on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, and American Society of Hypertension.

Home monitoring came up far more often at this year’s joint sessions than in 2017, which might indicate growing interest, but reimbursement remains a challenge. American Medical Association staff said at this year’s meeting that they are working with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for coverage of the devices and their use. It seemed likely to them.

In the meantime, Dr. Bosworth had some useful advice for those who are thinking about incorporating home BP monitoring into their practices.

He shared his tips on how to pick out a device – there’s actually a journal called Blood Pressure Monitoring that can help – as well as his thoughts on how often people should monitor themselves and what to do with the numbers.

He envisions a future when patients routinely check their BP at home; it’s even possible they could adjust their medications based on the results, much like diabetes patients track their blood glucose and adjust their insulin. It’s been shown to work in Britain (JAMA. 2014 Aug 27;312[8]:799-808).

Dr. Bosworth reported no relevant disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM JOINT HYPERTENSION 2018

U.S. perspective: Euro hypertension guidelines look a lot like ours

MUNICH – The “overwhelming impression” that Paul K. Whelton, MD, has of the newly revised hypertension diagnosis and management guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology is their similarity to hypertension guidelines released by the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association in November 2017.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

“We both recommend the same treatment target, of less than 130/80 mm Hg,” noted Dr. Whelton, professor at Tulane University in New Orleans, although the European guidelines (Euro J Cardiology. 2018 Sep 1; 39[33]:3021-104) put more qualifications on this target and specify treating to no lower than 130 mm Hg systolic pressure in patients who are at least 65 years old as well as in patients with chronic kidney disease at any age. In a video interview, Dr. Whelton also cited areas of disagreement, such as how patients with an untreated blood pressure of 130-139 mm Hg are classified (high normal in the European guidelines, stage 1 hypertension in the U.S. guidelines), and whether initial drug monotherapy is a reasonable treatment strategy (U.S. says yes, Europe says no).

Dr. Whelton noted that recent modeling studies have documented the potential public health benefits from following the diagnosis and management approaches set forth in the 2017 U.S. guidelines (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 May;71[19]:e127-e248). For example, an analysis based on data collected by the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey during 2013-2016 showed that following the 2017 guidelines for diagnosing and treating hypertension would have resulted in prevention of more than twice the number of cardiovascular disease events nationally as compared with application of the prior, 2014 U.S. hypertension guideline (JAMA. 2014 Feb 5;311[5]:507-20): 610,000 events prevented, compared with 270,000 events prevented. The same study showed that the 2017 guidelines would have nearly doubled the number of all-cause deaths prevented, with 334,000 deaths prevented, compared with 177,000 prevented by applying the 2014 guidelines (JAMA Cardiology. 2018 July;3[7]:572-81).

Dr. Whelton had no commercial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

MUNICH – The “overwhelming impression” that Paul K. Whelton, MD, has of the newly revised hypertension diagnosis and management guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology is their similarity to hypertension guidelines released by the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association in November 2017.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

“We both recommend the same treatment target, of less than 130/80 mm Hg,” noted Dr. Whelton, professor at Tulane University in New Orleans, although the European guidelines (Euro J Cardiology. 2018 Sep 1; 39[33]:3021-104) put more qualifications on this target and specify treating to no lower than 130 mm Hg systolic pressure in patients who are at least 65 years old as well as in patients with chronic kidney disease at any age. In a video interview, Dr. Whelton also cited areas of disagreement, such as how patients with an untreated blood pressure of 130-139 mm Hg are classified (high normal in the European guidelines, stage 1 hypertension in the U.S. guidelines), and whether initial drug monotherapy is a reasonable treatment strategy (U.S. says yes, Europe says no).

Dr. Whelton noted that recent modeling studies have documented the potential public health benefits from following the diagnosis and management approaches set forth in the 2017 U.S. guidelines (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 May;71[19]:e127-e248). For example, an analysis based on data collected by the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey during 2013-2016 showed that following the 2017 guidelines for diagnosing and treating hypertension would have resulted in prevention of more than twice the number of cardiovascular disease events nationally as compared with application of the prior, 2014 U.S. hypertension guideline (JAMA. 2014 Feb 5;311[5]:507-20): 610,000 events prevented, compared with 270,000 events prevented. The same study showed that the 2017 guidelines would have nearly doubled the number of all-cause deaths prevented, with 334,000 deaths prevented, compared with 177,000 prevented by applying the 2014 guidelines (JAMA Cardiology. 2018 July;3[7]:572-81).

Dr. Whelton had no commercial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

MUNICH – The “overwhelming impression” that Paul K. Whelton, MD, has of the newly revised hypertension diagnosis and management guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology is their similarity to hypertension guidelines released by the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association in November 2017.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

“We both recommend the same treatment target, of less than 130/80 mm Hg,” noted Dr. Whelton, professor at Tulane University in New Orleans, although the European guidelines (Euro J Cardiology. 2018 Sep 1; 39[33]:3021-104) put more qualifications on this target and specify treating to no lower than 130 mm Hg systolic pressure in patients who are at least 65 years old as well as in patients with chronic kidney disease at any age. In a video interview, Dr. Whelton also cited areas of disagreement, such as how patients with an untreated blood pressure of 130-139 mm Hg are classified (high normal in the European guidelines, stage 1 hypertension in the U.S. guidelines), and whether initial drug monotherapy is a reasonable treatment strategy (U.S. says yes, Europe says no).

Dr. Whelton noted that recent modeling studies have documented the potential public health benefits from following the diagnosis and management approaches set forth in the 2017 U.S. guidelines (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 May;71[19]:e127-e248). For example, an analysis based on data collected by the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey during 2013-2016 showed that following the 2017 guidelines for diagnosing and treating hypertension would have resulted in prevention of more than twice the number of cardiovascular disease events nationally as compared with application of the prior, 2014 U.S. hypertension guideline (JAMA. 2014 Feb 5;311[5]:507-20): 610,000 events prevented, compared with 270,000 events prevented. The same study showed that the 2017 guidelines would have nearly doubled the number of all-cause deaths prevented, with 334,000 deaths prevented, compared with 177,000 prevented by applying the 2014 guidelines (JAMA Cardiology. 2018 July;3[7]:572-81).

Dr. Whelton had no commercial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

REPORTING FROM THE ESC CONGRESS 2018

New Euro hypertension guidelines target most adults to less than 130/80 mm Hg

MUNICH – The European Society of Cardiology joined other international cardiology groups in endorsing lower targets for blood pressure treatment and lower pressure thresholds for starting drug treatment in its revised hypertension diagnosis and management guidelines released in August during the Society’s annual congress here.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

“Provided that treatment is well tolerated, treated blood pressure should be targeted to 130/80 mm Hg or lower in most patients,” Giuseppe Mancia, MD, said as he and his colleagues presented the new guidelines at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Although the new European guidelines further buttress this more aggressive approach to blood pressure management that first appeared almost a year ago in U.S. guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, an approach that remains controversial among U.S. primary care physicians, the European strategy (Eur Heart J. 2018 Sep 1;39[33]:3021-104) was generally more cautious than the broader endorsement of lower blood pressure goals advanced by the U.S. recommendations (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 May;71[19]:e127-e248).

In the European approach, “the first objective is to treat to less than 140/90 mm Hg. If this is well tolerated, then treat to less than 130/80 mm Hg in most patients,” said Dr. Mancia, cochair of the European writing panel. Further pressure reductions to less than 130/80 mm Hg are usually harder, the incremental benefit from further reduction is less than when pressures first fall below 140/90 mm Hg, and the evidence for incremental benefit of any size from further pressure reduction is less strong for certain key patient subgroups: people at least 80 years old, and patients with diabetes, chronic kidney disease, or coronary artery disease, said Dr. Mancia, an emeritus professor at the University of Milan.

“The consistency between two major guidelines is important, but there are differences that may look subtle but are not subtle,” he said in a video interview. “If a patient gets to less than 140 mm Hg, the doctor should not think that’s a failure; it’s a very important result.”

One striking example of how the two guidelines differ on treatment targets is for people at least 80 years old. The overall blood pressure threshold for starting drug treatment in patients this age in the European guidelines is 160/90 mm Hg, although it remains at 140/90 for people aged 65-79 years old “provided that treatment is well tolerated” and the patients are “fit.” The 2017 U.S. guidelines, by contrast, say that considering drug treatment for everyone with a pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg is a class I recommendation regardless of age as long as the person is “noninstitutionalized, ambulatory, [and] community-dwelling.” Once an older patient of any age, 65 years or older, starts drug treatment to reduce blood pressure, the European guidelines allow for treating to a target systolic blood pressure of 130-139 mm Hg as long as the regimen is well tolerated, and the guidelines say that a diastolic pressure target of less than 80 mm Hg should be considered for all adults regardless of age.

The new European guidelines also define adults with an untreated pressure of 130-139/85-89 mm Hg as “high normal,” rather than the “stage 1 hypertension” designation given to people with pressures of 130-139/80-89 mm Hg in the U.S. guidelines. Robert M. Carey, MD, vice chair of the U.S. guidelines panel, minimized this as a “semantic” difference, and he highlighted that management of people with pressures in this range is roughly similar in the two sets of recommendations. “The name is different, but treatment is the same,” Dr. Carey said.

The European guidelines call for initial lifestyle interventions, followed by drug treatment “that may be considered” for patients who have “very-high” cardiovascular risk because of established cardiovascular disease, especially coronary artery disease, and detail the specific clinical conditions that fall into the very-high-risk category. The U.S. guidelines say that stage 1 hypertension patients should get lifestyle interventions, followed by drug treatment for the roughly 30% of patients in this category who score at least a 10% 10-year risk on the American College of Cardiology’s Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk Estimator Plus.The new European guidelines are a “validation” of the ACC/AHA 2017 guidelines, commented Dr. Carey, a professor of medicine at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. “Overall, we’re delighted to have these two major groups” agree, he said in an interview. “There is a tremendous amount of concurrence.”

Other areas of agreement between the two guidelines include their emphasis on careful and repeated blood pressure measurement, including out-of-office measurement, before settling on a diagnosis of hypertension; systematic assessment of possible masked or white-coat hypertension in selected people; and frequent use of combined drug treatment including initiation of a dual-drug, single-pill regimen when starting drug treatment and aggressive follow-up by adding a third drug when needed. However, in another divergence the U.S. guidelines give a much stronger endorsement to starting treatment with monotherapy, a strategy the European guidelines scrapped.

Dr. Carey also noted that the European endorsement of three antihypertensives formulated into a single pill for patients who need more than two drugs would be difficult for American clinicians to follow as virtually no such formulations are approved for U.S. use.

Dr. Mancini has received honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, CVRx, Daiichi Sankyo, Ferrer, Medtronic, Menarini, Merck, Novartis, Recordati, and Servier. Dr. Williams has been a consultant to Novartis, Relypsa, and Vascular Dynamics, and he has spoken on behalf of Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Novartis, and Servier. Dr. Carey and Dr. Whelton had no commercial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

MUNICH – The European Society of Cardiology joined other international cardiology groups in endorsing lower targets for blood pressure treatment and lower pressure thresholds for starting drug treatment in its revised hypertension diagnosis and management guidelines released in August during the Society’s annual congress here.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

“Provided that treatment is well tolerated, treated blood pressure should be targeted to 130/80 mm Hg or lower in most patients,” Giuseppe Mancia, MD, said as he and his colleagues presented the new guidelines at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Although the new European guidelines further buttress this more aggressive approach to blood pressure management that first appeared almost a year ago in U.S. guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, an approach that remains controversial among U.S. primary care physicians, the European strategy (Eur Heart J. 2018 Sep 1;39[33]:3021-104) was generally more cautious than the broader endorsement of lower blood pressure goals advanced by the U.S. recommendations (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 May;71[19]:e127-e248).

In the European approach, “the first objective is to treat to less than 140/90 mm Hg. If this is well tolerated, then treat to less than 130/80 mm Hg in most patients,” said Dr. Mancia, cochair of the European writing panel. Further pressure reductions to less than 130/80 mm Hg are usually harder, the incremental benefit from further reduction is less than when pressures first fall below 140/90 mm Hg, and the evidence for incremental benefit of any size from further pressure reduction is less strong for certain key patient subgroups: people at least 80 years old, and patients with diabetes, chronic kidney disease, or coronary artery disease, said Dr. Mancia, an emeritus professor at the University of Milan.

“The consistency between two major guidelines is important, but there are differences that may look subtle but are not subtle,” he said in a video interview. “If a patient gets to less than 140 mm Hg, the doctor should not think that’s a failure; it’s a very important result.”

One striking example of how the two guidelines differ on treatment targets is for people at least 80 years old. The overall blood pressure threshold for starting drug treatment in patients this age in the European guidelines is 160/90 mm Hg, although it remains at 140/90 for people aged 65-79 years old “provided that treatment is well tolerated” and the patients are “fit.” The 2017 U.S. guidelines, by contrast, say that considering drug treatment for everyone with a pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg is a class I recommendation regardless of age as long as the person is “noninstitutionalized, ambulatory, [and] community-dwelling.” Once an older patient of any age, 65 years or older, starts drug treatment to reduce blood pressure, the European guidelines allow for treating to a target systolic blood pressure of 130-139 mm Hg as long as the regimen is well tolerated, and the guidelines say that a diastolic pressure target of less than 80 mm Hg should be considered for all adults regardless of age.

The new European guidelines also define adults with an untreated pressure of 130-139/85-89 mm Hg as “high normal,” rather than the “stage 1 hypertension” designation given to people with pressures of 130-139/80-89 mm Hg in the U.S. guidelines. Robert M. Carey, MD, vice chair of the U.S. guidelines panel, minimized this as a “semantic” difference, and he highlighted that management of people with pressures in this range is roughly similar in the two sets of recommendations. “The name is different, but treatment is the same,” Dr. Carey said.

The European guidelines call for initial lifestyle interventions, followed by drug treatment “that may be considered” for patients who have “very-high” cardiovascular risk because of established cardiovascular disease, especially coronary artery disease, and detail the specific clinical conditions that fall into the very-high-risk category. The U.S. guidelines say that stage 1 hypertension patients should get lifestyle interventions, followed by drug treatment for the roughly 30% of patients in this category who score at least a 10% 10-year risk on the American College of Cardiology’s Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk Estimator Plus.The new European guidelines are a “validation” of the ACC/AHA 2017 guidelines, commented Dr. Carey, a professor of medicine at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. “Overall, we’re delighted to have these two major groups” agree, he said in an interview. “There is a tremendous amount of concurrence.”

Other areas of agreement between the two guidelines include their emphasis on careful and repeated blood pressure measurement, including out-of-office measurement, before settling on a diagnosis of hypertension; systematic assessment of possible masked or white-coat hypertension in selected people; and frequent use of combined drug treatment including initiation of a dual-drug, single-pill regimen when starting drug treatment and aggressive follow-up by adding a third drug when needed. However, in another divergence the U.S. guidelines give a much stronger endorsement to starting treatment with monotherapy, a strategy the European guidelines scrapped.

Dr. Carey also noted that the European endorsement of three antihypertensives formulated into a single pill for patients who need more than two drugs would be difficult for American clinicians to follow as virtually no such formulations are approved for U.S. use.

Dr. Mancini has received honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, CVRx, Daiichi Sankyo, Ferrer, Medtronic, Menarini, Merck, Novartis, Recordati, and Servier. Dr. Williams has been a consultant to Novartis, Relypsa, and Vascular Dynamics, and he has spoken on behalf of Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Novartis, and Servier. Dr. Carey and Dr. Whelton had no commercial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

MUNICH – The European Society of Cardiology joined other international cardiology groups in endorsing lower targets for blood pressure treatment and lower pressure thresholds for starting drug treatment in its revised hypertension diagnosis and management guidelines released in August during the Society’s annual congress here.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

“Provided that treatment is well tolerated, treated blood pressure should be targeted to 130/80 mm Hg or lower in most patients,” Giuseppe Mancia, MD, said as he and his colleagues presented the new guidelines at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Although the new European guidelines further buttress this more aggressive approach to blood pressure management that first appeared almost a year ago in U.S. guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, an approach that remains controversial among U.S. primary care physicians, the European strategy (Eur Heart J. 2018 Sep 1;39[33]:3021-104) was generally more cautious than the broader endorsement of lower blood pressure goals advanced by the U.S. recommendations (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 May;71[19]:e127-e248).

In the European approach, “the first objective is to treat to less than 140/90 mm Hg. If this is well tolerated, then treat to less than 130/80 mm Hg in most patients,” said Dr. Mancia, cochair of the European writing panel. Further pressure reductions to less than 130/80 mm Hg are usually harder, the incremental benefit from further reduction is less than when pressures first fall below 140/90 mm Hg, and the evidence for incremental benefit of any size from further pressure reduction is less strong for certain key patient subgroups: people at least 80 years old, and patients with diabetes, chronic kidney disease, or coronary artery disease, said Dr. Mancia, an emeritus professor at the University of Milan.

“The consistency between two major guidelines is important, but there are differences that may look subtle but are not subtle,” he said in a video interview. “If a patient gets to less than 140 mm Hg, the doctor should not think that’s a failure; it’s a very important result.”

One striking example of how the two guidelines differ on treatment targets is for people at least 80 years old. The overall blood pressure threshold for starting drug treatment in patients this age in the European guidelines is 160/90 mm Hg, although it remains at 140/90 for people aged 65-79 years old “provided that treatment is well tolerated” and the patients are “fit.” The 2017 U.S. guidelines, by contrast, say that considering drug treatment for everyone with a pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg is a class I recommendation regardless of age as long as the person is “noninstitutionalized, ambulatory, [and] community-dwelling.” Once an older patient of any age, 65 years or older, starts drug treatment to reduce blood pressure, the European guidelines allow for treating to a target systolic blood pressure of 130-139 mm Hg as long as the regimen is well tolerated, and the guidelines say that a diastolic pressure target of less than 80 mm Hg should be considered for all adults regardless of age.

The new European guidelines also define adults with an untreated pressure of 130-139/85-89 mm Hg as “high normal,” rather than the “stage 1 hypertension” designation given to people with pressures of 130-139/80-89 mm Hg in the U.S. guidelines. Robert M. Carey, MD, vice chair of the U.S. guidelines panel, minimized this as a “semantic” difference, and he highlighted that management of people with pressures in this range is roughly similar in the two sets of recommendations. “The name is different, but treatment is the same,” Dr. Carey said.

The European guidelines call for initial lifestyle interventions, followed by drug treatment “that may be considered” for patients who have “very-high” cardiovascular risk because of established cardiovascular disease, especially coronary artery disease, and detail the specific clinical conditions that fall into the very-high-risk category. The U.S. guidelines say that stage 1 hypertension patients should get lifestyle interventions, followed by drug treatment for the roughly 30% of patients in this category who score at least a 10% 10-year risk on the American College of Cardiology’s Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk Estimator Plus.The new European guidelines are a “validation” of the ACC/AHA 2017 guidelines, commented Dr. Carey, a professor of medicine at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. “Overall, we’re delighted to have these two major groups” agree, he said in an interview. “There is a tremendous amount of concurrence.”

Other areas of agreement between the two guidelines include their emphasis on careful and repeated blood pressure measurement, including out-of-office measurement, before settling on a diagnosis of hypertension; systematic assessment of possible masked or white-coat hypertension in selected people; and frequent use of combined drug treatment including initiation of a dual-drug, single-pill regimen when starting drug treatment and aggressive follow-up by adding a third drug when needed. However, in another divergence the U.S. guidelines give a much stronger endorsement to starting treatment with monotherapy, a strategy the European guidelines scrapped.

Dr. Carey also noted that the European endorsement of three antihypertensives formulated into a single pill for patients who need more than two drugs would be difficult for American clinicians to follow as virtually no such formulations are approved for U.S. use.

Dr. Mancini has received honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, CVRx, Daiichi Sankyo, Ferrer, Medtronic, Menarini, Merck, Novartis, Recordati, and Servier. Dr. Williams has been a consultant to Novartis, Relypsa, and Vascular Dynamics, and he has spoken on behalf of Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Novartis, and Servier. Dr. Carey and Dr. Whelton had no commercial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

REPORTING FROM THE ESC CONGRESS 2018

ARRIVE: What are the perinatal and maternal consequences of labor induction at 39 weeks compared with expectant management?

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR PRACTICE?

- Induction of labor at 39 weeks in low-risk nulliparas, irrespective of Bishop score, seems to be a reasonable option to be included in route of delivery discussions with patients as part of the principle of shared decision-making.

- The data in this trial would suggest that such an approach not only reduces adverse perinatal outcomes but also may reduce the need for subsequent cesarean delivery.

September 2018 Issue Highlights

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Click here to view the articles published in September 2018.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Click here to view the articles published in September 2018.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Click here to view the articles published in September 2018.

A postgraduate tour through the biliary tree, pancreas, and liver

For the pancreatobiliary session, Michelle Ann Anderson, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, reminded us about appropriate patient selection given the risk of pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis, also known as post-ERCP pancreatitis. Strategies to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis include using pancreatic duct stents and using wire rather than contrast for cannulation. She recommended rectal indomethacin for all patients. Because of encouraging data, she recommended 2-3 L of lactated Ringer’s solution during the procedure and recovery.

Katie Morgan, MD, from the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, reviewed her group’s experience with 195 total pancreatectomies with islet autotransplants for chronic pancreatitis. Quality of life improved with major reductions in narcotic use, and 25% of patients were insulin free.

Bret Petersen, MD, of Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., discussed multidrug resistant infection in ERCP endoscopes. He reminded us of the risk of lapses in endoscope reprocessing steps and the need for monitoring. He commented on recent Food and Drug Administration’s culture guidance and new technologies in development.

James Scheiman, MD, from the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, discussed pancreatic cysts. He reviewed the controversy between the more conservative American Gastroenterological Association guidelines and the more aggressive International Consensus guidelines. He advised considering patient preferences with a multidisciplinary approach.

For the liver session, Guadalupe García-Tsao, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., discussed the controversy regarding nonselective beta-blockers. She advised caution if refractory ascites are present because of risk for renal dysfunction, but she also highlighted the benefits including reduced first and recurrent variceal hemorrhage.

Rohit Loomba, MD, from the University of California at San Diego addressed fibrosis assessments in fatty liver. In his algorithm, patients with low Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Fibrosis Score or Fibrosis-4 scores would have continued observation, while patients with medium or high scores would undergo transient elastography or magnetic resonance elastography.

Patrick Northup, MD, from the University of Virginia discussed anticoagulation for portal vein thrombosis. He also discussed consideration of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt if there are high-risk varices. Duration of anticoagulation is controversial, but this strategy may prevent decompensation and affect transplant outcomes.

Daryl Lau, MD, MSc, MPH, from Harvard Medical School, Boston, reviewed the hepatitis B virus therapy controversy for e-antigen–negative patients with prolonged viral suppression. She recommended caution in general and emphasized that stage 3-4 fibrosis patients should not discontinue therapy.

The final talk was my review of hepatitis C virus treatment. I emphasized that pretreatment fibrosis assessments are critical given continued risk of hepatocellular carcinoma after cure. Challenges include identifying the remaining patients and supporting them through treatment. HCV therapies demonstrate what is possible when breakthroughs are translated to clinical care, and I was honored to participate in this course that highlighted many advances in our field.

Dr. Muir is a professor of medicine, director of gastroenterology & hepatology research at Duke Clinical Research Institute, and chief of the division of gastroenterology in the department of medicine at Duke University, all in Durham, N.C. He has received research grants from and served on the advisory boards for AbbVie, Gilead Sciences, Merck, and several other pharmaceutical companies. This is a summary provided by the moderator of one of the spring postgraduate course sessions held at DDW 2018.

For the pancreatobiliary session, Michelle Ann Anderson, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, reminded us about appropriate patient selection given the risk of pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis, also known as post-ERCP pancreatitis. Strategies to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis include using pancreatic duct stents and using wire rather than contrast for cannulation. She recommended rectal indomethacin for all patients. Because of encouraging data, she recommended 2-3 L of lactated Ringer’s solution during the procedure and recovery.

Katie Morgan, MD, from the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, reviewed her group’s experience with 195 total pancreatectomies with islet autotransplants for chronic pancreatitis. Quality of life improved with major reductions in narcotic use, and 25% of patients were insulin free.

Bret Petersen, MD, of Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., discussed multidrug resistant infection in ERCP endoscopes. He reminded us of the risk of lapses in endoscope reprocessing steps and the need for monitoring. He commented on recent Food and Drug Administration’s culture guidance and new technologies in development.

James Scheiman, MD, from the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, discussed pancreatic cysts. He reviewed the controversy between the more conservative American Gastroenterological Association guidelines and the more aggressive International Consensus guidelines. He advised considering patient preferences with a multidisciplinary approach.

For the liver session, Guadalupe García-Tsao, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., discussed the controversy regarding nonselective beta-blockers. She advised caution if refractory ascites are present because of risk for renal dysfunction, but she also highlighted the benefits including reduced first and recurrent variceal hemorrhage.

Rohit Loomba, MD, from the University of California at San Diego addressed fibrosis assessments in fatty liver. In his algorithm, patients with low Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Fibrosis Score or Fibrosis-4 scores would have continued observation, while patients with medium or high scores would undergo transient elastography or magnetic resonance elastography.

Patrick Northup, MD, from the University of Virginia discussed anticoagulation for portal vein thrombosis. He also discussed consideration of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt if there are high-risk varices. Duration of anticoagulation is controversial, but this strategy may prevent decompensation and affect transplant outcomes.

Daryl Lau, MD, MSc, MPH, from Harvard Medical School, Boston, reviewed the hepatitis B virus therapy controversy for e-antigen–negative patients with prolonged viral suppression. She recommended caution in general and emphasized that stage 3-4 fibrosis patients should not discontinue therapy.

The final talk was my review of hepatitis C virus treatment. I emphasized that pretreatment fibrosis assessments are critical given continued risk of hepatocellular carcinoma after cure. Challenges include identifying the remaining patients and supporting them through treatment. HCV therapies demonstrate what is possible when breakthroughs are translated to clinical care, and I was honored to participate in this course that highlighted many advances in our field.

Dr. Muir is a professor of medicine, director of gastroenterology & hepatology research at Duke Clinical Research Institute, and chief of the division of gastroenterology in the department of medicine at Duke University, all in Durham, N.C. He has received research grants from and served on the advisory boards for AbbVie, Gilead Sciences, Merck, and several other pharmaceutical companies. This is a summary provided by the moderator of one of the spring postgraduate course sessions held at DDW 2018.

For the pancreatobiliary session, Michelle Ann Anderson, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, reminded us about appropriate patient selection given the risk of pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis, also known as post-ERCP pancreatitis. Strategies to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis include using pancreatic duct stents and using wire rather than contrast for cannulation. She recommended rectal indomethacin for all patients. Because of encouraging data, she recommended 2-3 L of lactated Ringer’s solution during the procedure and recovery.

Katie Morgan, MD, from the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, reviewed her group’s experience with 195 total pancreatectomies with islet autotransplants for chronic pancreatitis. Quality of life improved with major reductions in narcotic use, and 25% of patients were insulin free.

Bret Petersen, MD, of Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., discussed multidrug resistant infection in ERCP endoscopes. He reminded us of the risk of lapses in endoscope reprocessing steps and the need for monitoring. He commented on recent Food and Drug Administration’s culture guidance and new technologies in development.

James Scheiman, MD, from the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, discussed pancreatic cysts. He reviewed the controversy between the more conservative American Gastroenterological Association guidelines and the more aggressive International Consensus guidelines. He advised considering patient preferences with a multidisciplinary approach.

For the liver session, Guadalupe García-Tsao, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., discussed the controversy regarding nonselective beta-blockers. She advised caution if refractory ascites are present because of risk for renal dysfunction, but she also highlighted the benefits including reduced first and recurrent variceal hemorrhage.

Rohit Loomba, MD, from the University of California at San Diego addressed fibrosis assessments in fatty liver. In his algorithm, patients with low Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Fibrosis Score or Fibrosis-4 scores would have continued observation, while patients with medium or high scores would undergo transient elastography or magnetic resonance elastography.

Patrick Northup, MD, from the University of Virginia discussed anticoagulation for portal vein thrombosis. He also discussed consideration of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt if there are high-risk varices. Duration of anticoagulation is controversial, but this strategy may prevent decompensation and affect transplant outcomes.

Daryl Lau, MD, MSc, MPH, from Harvard Medical School, Boston, reviewed the hepatitis B virus therapy controversy for e-antigen–negative patients with prolonged viral suppression. She recommended caution in general and emphasized that stage 3-4 fibrosis patients should not discontinue therapy.

The final talk was my review of hepatitis C virus treatment. I emphasized that pretreatment fibrosis assessments are critical given continued risk of hepatocellular carcinoma after cure. Challenges include identifying the remaining patients and supporting them through treatment. HCV therapies demonstrate what is possible when breakthroughs are translated to clinical care, and I was honored to participate in this course that highlighted many advances in our field.

Dr. Muir is a professor of medicine, director of gastroenterology & hepatology research at Duke Clinical Research Institute, and chief of the division of gastroenterology in the department of medicine at Duke University, all in Durham, N.C. He has received research grants from and served on the advisory boards for AbbVie, Gilead Sciences, Merck, and several other pharmaceutical companies. This is a summary provided by the moderator of one of the spring postgraduate course sessions held at DDW 2018.