User login

What is your diagnosis? - January 2019

Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia

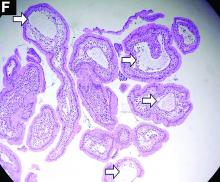

Histologic examination shows chronic inflammation of the ileum characterized by increased lymphoplasma cell infiltration of lamina propria without malignancy. Moreover, marked dilatation of lymphatic ducts that involved the mucosa was identified (Figure F, arrows; stain: hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification, ×100). On the basis of pathologic examinations, a diagnosis of primary intestinal lymphangiectasia (PIL) was made.

PIL is an extremely rare cause of protein-losing enteropathy characterized by the presence of dilated lymphatic channels in the mucosa, submucosa, or subserosa leading to protein-losing enteropathy.1 The true incidence and prevalence of this disease remains unclear. The disease affects males and females equally, and usually occurs in children and young adults. To date, less than 200 cases of PIL have been reported in the literature. The clinical manifestations of PIL may be asymptomatic or symptomatic such as abdominal pain, edema, diarrhea, and dyspnea. The diagnosis is based on the typical endoscopic findings of diffuse scattered mucosal white blebs with characteristic histologic findings of abnormal lymphatic dilatation. Double-balloon enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy are powerful modalities to evaluate the entire affected area of PIL.2 Although diet modification is a major treatment of PIL, several medicines have been reported to be useful such as corticosteroids, octreotide, and antiplasmin.3 Moreover, in patients with segmental lesions, surgery with local bowel resection is a useful treatment.3 In addition, PIL had a 5% risk of malignant transformation into lymphoma.3

References

1. Waldmann TA, Steinfeld JL, Dutcher TF, et al. The role of the gastrointestinal system in “idiopathic hypoproteinemia.” Gastroenterology. 1961;41:197-207.

2. Oh TG, Chung JW, Kim HM, et al. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia diagnosed by capsule endoscopy and double balloon enteroscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;3:235-40.

3. Wen J, Tang Q, Wu, J. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia: four case reports and a review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3466-72.

Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia

Histologic examination shows chronic inflammation of the ileum characterized by increased lymphoplasma cell infiltration of lamina propria without malignancy. Moreover, marked dilatation of lymphatic ducts that involved the mucosa was identified (Figure F, arrows; stain: hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification, ×100). On the basis of pathologic examinations, a diagnosis of primary intestinal lymphangiectasia (PIL) was made.

PIL is an extremely rare cause of protein-losing enteropathy characterized by the presence of dilated lymphatic channels in the mucosa, submucosa, or subserosa leading to protein-losing enteropathy.1 The true incidence and prevalence of this disease remains unclear. The disease affects males and females equally, and usually occurs in children and young adults. To date, less than 200 cases of PIL have been reported in the literature. The clinical manifestations of PIL may be asymptomatic or symptomatic such as abdominal pain, edema, diarrhea, and dyspnea. The diagnosis is based on the typical endoscopic findings of diffuse scattered mucosal white blebs with characteristic histologic findings of abnormal lymphatic dilatation. Double-balloon enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy are powerful modalities to evaluate the entire affected area of PIL.2 Although diet modification is a major treatment of PIL, several medicines have been reported to be useful such as corticosteroids, octreotide, and antiplasmin.3 Moreover, in patients with segmental lesions, surgery with local bowel resection is a useful treatment.3 In addition, PIL had a 5% risk of malignant transformation into lymphoma.3

References

1. Waldmann TA, Steinfeld JL, Dutcher TF, et al. The role of the gastrointestinal system in “idiopathic hypoproteinemia.” Gastroenterology. 1961;41:197-207.

2. Oh TG, Chung JW, Kim HM, et al. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia diagnosed by capsule endoscopy and double balloon enteroscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;3:235-40.

3. Wen J, Tang Q, Wu, J. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia: four case reports and a review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3466-72.

Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia

Histologic examination shows chronic inflammation of the ileum characterized by increased lymphoplasma cell infiltration of lamina propria without malignancy. Moreover, marked dilatation of lymphatic ducts that involved the mucosa was identified (Figure F, arrows; stain: hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification, ×100). On the basis of pathologic examinations, a diagnosis of primary intestinal lymphangiectasia (PIL) was made.

PIL is an extremely rare cause of protein-losing enteropathy characterized by the presence of dilated lymphatic channels in the mucosa, submucosa, or subserosa leading to protein-losing enteropathy.1 The true incidence and prevalence of this disease remains unclear. The disease affects males and females equally, and usually occurs in children and young adults. To date, less than 200 cases of PIL have been reported in the literature. The clinical manifestations of PIL may be asymptomatic or symptomatic such as abdominal pain, edema, diarrhea, and dyspnea. The diagnosis is based on the typical endoscopic findings of diffuse scattered mucosal white blebs with characteristic histologic findings of abnormal lymphatic dilatation. Double-balloon enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy are powerful modalities to evaluate the entire affected area of PIL.2 Although diet modification is a major treatment of PIL, several medicines have been reported to be useful such as corticosteroids, octreotide, and antiplasmin.3 Moreover, in patients with segmental lesions, surgery with local bowel resection is a useful treatment.3 In addition, PIL had a 5% risk of malignant transformation into lymphoma.3

References

1. Waldmann TA, Steinfeld JL, Dutcher TF, et al. The role of the gastrointestinal system in “idiopathic hypoproteinemia.” Gastroenterology. 1961;41:197-207.

2. Oh TG, Chung JW, Kim HM, et al. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia diagnosed by capsule endoscopy and double balloon enteroscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;3:235-40.

3. Wen J, Tang Q, Wu, J. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia: four case reports and a review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3466-72.

A 19-year-old boy presented to our hospital because of a 6-month history of progressive dyspnea and generalized edema. He developed cough, abdominal fullness, diarrhea, and leg edema 5 years ago.

Liver cirrhosis was suspected at that time. However, he seemed to have a poor response to medical treatment. Physical examination showed decreased breathing sounds and rales of the bilateral lower chest area, a distended abdomen with multiple purple striae, and edema of bilateral lower legs.

Laboratory tests showed a low serum total protein of 3.8 g/dL (normal range, 5.5–8), albumin of 2.0 g/dL (normal range, 3.8–5.4), total calcium of 7 mg/dL (normal range, 8.4–10.8), C-reactive protein of 11.02 mg/dL (normal, below 0.8). His hemogram showed a white blood cell count of 13,310 × 109/L (normal range, 3.5–11 × 109/L) with lymphocytopenia (9.8%).

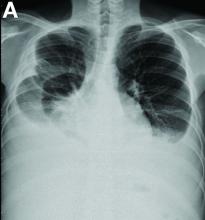

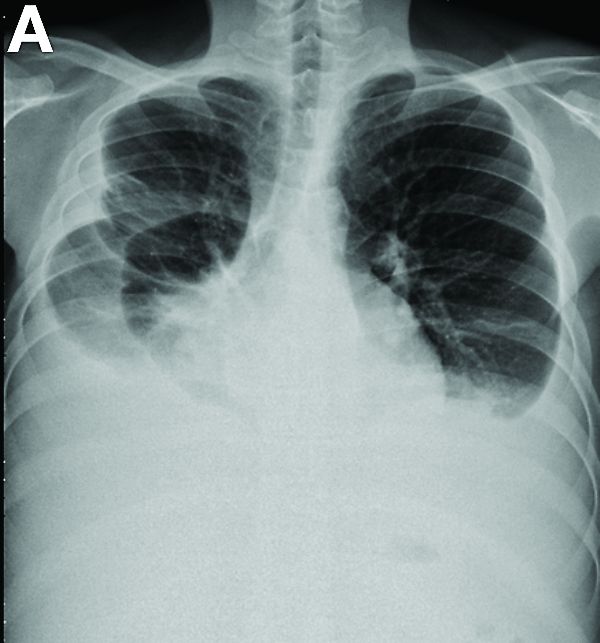

Other blood tests were within normal limits. The urinalysis and stool analysis were normal. Chest radiography showed bilateral pleural effusions (Figure A). Abdominal computed tomography demonstrated large ascites (Figure B). Paracentesis showed his serum ascites albumin gradient was 1.9 g/dL.

Subsequently, antegrade double-balloon enteroscopy (Fujinon EN-450T5; Fujinon, Saitama, Japan) demonstrated nodular mucosal lesions with a milk-like surface in the duodenum (Figure C).

Moreover, a snowflake appearance of mucosa was found in the jejunum and proximal ileum (Figure D). However, normal appearance of mucosa was identified in the middle ileum (Figure E). Biopsy specimens from these abnormal mucosal lesions were taken for pathology.

What is the diagnosis?

The SVS is working for you on burnout

Following a series of Vascular Specialist pieces highlighting the crisis of surgeon burnout and the unique challenges that face vascular surgeons, the SVS Wellness Task Force was formed in 2017. Recognizing that burnout may compromise recruitment and retention into our specialty, a particular threat at a time when our specialty faces projected increasing physician workforce needs, and that data suggests physician burnout compromises both patient quality of care and overall satisfaction, the task force was charged with proactively addressing vascular surgeon burnout. Our task force, comprising 21 engaged SVS members from across the country, has been working with strong support from leadership and administration to identify potential SVS targets for meaningful change.

The year 2018 was one of information gathering as we attempted clarify the severity of the problem and perceived member needs. We are grateful to our membership that have helped with this effort – for their time, for their insight, and for sharing their stories (some of which have been deeply personal). Two large-scale surveys were circulated to active SVS membership, both created with the assistance of the Mayo Clinic’s Division of Health Policy and Research.

The first survey was designed with a framework of validated wellness tools and well-described risk factors for burnout, then further “personalized” to incorporate unique challenges to the vascular surgeon. About 32% of our membership responded to this survey and alarmingly, when considering nonretired active SVS members, approximately one-third self-described depressive symptoms, 35% met criteria for burnout, and 8% self-reported suicidal thoughts in the last 12 months.

The second survey has only recently closed, focusing on the ergonomic challenges that we face across the spectrum of complex open and endovascular cases. Recognizing existing data that chronic pain and physical disability are associated with burnout, this data will be linked back to the original survey responses for association. Certainly there is more to come.

Concurrent with our survey initiatives, many of you participated in a Wellness Focus Group during VAM 2018. These focus groups intentionally considered the diversity of our membership across age, gender, practice setting, and region, revealing several important themes that threaten our wellness. It was no surprise that the EMR was identified as a clear threat to vascular surgery well-being and that this is not unique to our specialty. Importantly, our membership collectively feels “undervalued” at an institutional level. Specifically given the scope of comprehensive vascular care that we provide patients, a large part of our work includes both unpredictable acute vascular surgical care (such as intraoperative consultations for vascular trauma) and remedial salvage operations to manage vascular complications inflicted during care received from other physicians. This effort leaves us with little control over our time, often without perceived reciprocal clinical support, institutional support, or compensation.

Given this data, the Wellness Task Force is now strategizing efforts for change and supporting ongoing SVS initiatives. Our Task Force is currently:

- Collaborating with key EMR stakeholders with the goal of creating tools that can be shared across the specialty and addressing best practices for system-level support.

- Drafting a “public reply” to the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology’s “Strategy on Reducing Burden Relating to the Use of Health IT and EHRs” initiative.

- Collaborating with national experts to establish peer support tools and SVS networking opportunities that may help members cope with adverse outcomes and strategize the delivery of complex care.

- Identifying institutional best practices for surgeon wellness for broad dissemination.

- Supporting existing SVS initiatives that include the PAC/APM task force, branding initiatives through the PPO as we work to “own our space” and leverage our specialty and the community practice committee as the Society works proactively to optimize workload, fairness, and reward on a larger scale for membership.

We encourage everyone to stay tuned for periodic Vascular Specialist “Wellness Features” and to attend the Wellness Session at the 2019 VAM for interim progress that will feature the following discussions.

- (Re)Finding a meaningful career in vascular surgery.

- Ergonomic challenges to the vascular surgeon and strategies to mitigate the resulting threat of disability.

- EMR best practices to optimize efficiency.

- The role of peer support in vascular surgery, including the mitigation of second victim syndrome.

Surgeon burnout is a real threat to our workforce and the well-being of our colleagues and friends. Risk factors are multifactorial and will require broad, system-level change. The SVS remains fully committed to enhancing vascular surgeon wellness and this Task Force is grateful for your ongoing engagement and support.

Dr. Coleman is an associate professor of vascular surgery at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Following a series of Vascular Specialist pieces highlighting the crisis of surgeon burnout and the unique challenges that face vascular surgeons, the SVS Wellness Task Force was formed in 2017. Recognizing that burnout may compromise recruitment and retention into our specialty, a particular threat at a time when our specialty faces projected increasing physician workforce needs, and that data suggests physician burnout compromises both patient quality of care and overall satisfaction, the task force was charged with proactively addressing vascular surgeon burnout. Our task force, comprising 21 engaged SVS members from across the country, has been working with strong support from leadership and administration to identify potential SVS targets for meaningful change.

The year 2018 was one of information gathering as we attempted clarify the severity of the problem and perceived member needs. We are grateful to our membership that have helped with this effort – for their time, for their insight, and for sharing their stories (some of which have been deeply personal). Two large-scale surveys were circulated to active SVS membership, both created with the assistance of the Mayo Clinic’s Division of Health Policy and Research.

The first survey was designed with a framework of validated wellness tools and well-described risk factors for burnout, then further “personalized” to incorporate unique challenges to the vascular surgeon. About 32% of our membership responded to this survey and alarmingly, when considering nonretired active SVS members, approximately one-third self-described depressive symptoms, 35% met criteria for burnout, and 8% self-reported suicidal thoughts in the last 12 months.

The second survey has only recently closed, focusing on the ergonomic challenges that we face across the spectrum of complex open and endovascular cases. Recognizing existing data that chronic pain and physical disability are associated with burnout, this data will be linked back to the original survey responses for association. Certainly there is more to come.

Concurrent with our survey initiatives, many of you participated in a Wellness Focus Group during VAM 2018. These focus groups intentionally considered the diversity of our membership across age, gender, practice setting, and region, revealing several important themes that threaten our wellness. It was no surprise that the EMR was identified as a clear threat to vascular surgery well-being and that this is not unique to our specialty. Importantly, our membership collectively feels “undervalued” at an institutional level. Specifically given the scope of comprehensive vascular care that we provide patients, a large part of our work includes both unpredictable acute vascular surgical care (such as intraoperative consultations for vascular trauma) and remedial salvage operations to manage vascular complications inflicted during care received from other physicians. This effort leaves us with little control over our time, often without perceived reciprocal clinical support, institutional support, or compensation.

Given this data, the Wellness Task Force is now strategizing efforts for change and supporting ongoing SVS initiatives. Our Task Force is currently:

- Collaborating with key EMR stakeholders with the goal of creating tools that can be shared across the specialty and addressing best practices for system-level support.

- Drafting a “public reply” to the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology’s “Strategy on Reducing Burden Relating to the Use of Health IT and EHRs” initiative.

- Collaborating with national experts to establish peer support tools and SVS networking opportunities that may help members cope with adverse outcomes and strategize the delivery of complex care.

- Identifying institutional best practices for surgeon wellness for broad dissemination.

- Supporting existing SVS initiatives that include the PAC/APM task force, branding initiatives through the PPO as we work to “own our space” and leverage our specialty and the community practice committee as the Society works proactively to optimize workload, fairness, and reward on a larger scale for membership.

We encourage everyone to stay tuned for periodic Vascular Specialist “Wellness Features” and to attend the Wellness Session at the 2019 VAM for interim progress that will feature the following discussions.

- (Re)Finding a meaningful career in vascular surgery.

- Ergonomic challenges to the vascular surgeon and strategies to mitigate the resulting threat of disability.

- EMR best practices to optimize efficiency.

- The role of peer support in vascular surgery, including the mitigation of second victim syndrome.

Surgeon burnout is a real threat to our workforce and the well-being of our colleagues and friends. Risk factors are multifactorial and will require broad, system-level change. The SVS remains fully committed to enhancing vascular surgeon wellness and this Task Force is grateful for your ongoing engagement and support.

Dr. Coleman is an associate professor of vascular surgery at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Following a series of Vascular Specialist pieces highlighting the crisis of surgeon burnout and the unique challenges that face vascular surgeons, the SVS Wellness Task Force was formed in 2017. Recognizing that burnout may compromise recruitment and retention into our specialty, a particular threat at a time when our specialty faces projected increasing physician workforce needs, and that data suggests physician burnout compromises both patient quality of care and overall satisfaction, the task force was charged with proactively addressing vascular surgeon burnout. Our task force, comprising 21 engaged SVS members from across the country, has been working with strong support from leadership and administration to identify potential SVS targets for meaningful change.

The year 2018 was one of information gathering as we attempted clarify the severity of the problem and perceived member needs. We are grateful to our membership that have helped with this effort – for their time, for their insight, and for sharing their stories (some of which have been deeply personal). Two large-scale surveys were circulated to active SVS membership, both created with the assistance of the Mayo Clinic’s Division of Health Policy and Research.

The first survey was designed with a framework of validated wellness tools and well-described risk factors for burnout, then further “personalized” to incorporate unique challenges to the vascular surgeon. About 32% of our membership responded to this survey and alarmingly, when considering nonretired active SVS members, approximately one-third self-described depressive symptoms, 35% met criteria for burnout, and 8% self-reported suicidal thoughts in the last 12 months.

The second survey has only recently closed, focusing on the ergonomic challenges that we face across the spectrum of complex open and endovascular cases. Recognizing existing data that chronic pain and physical disability are associated with burnout, this data will be linked back to the original survey responses for association. Certainly there is more to come.

Concurrent with our survey initiatives, many of you participated in a Wellness Focus Group during VAM 2018. These focus groups intentionally considered the diversity of our membership across age, gender, practice setting, and region, revealing several important themes that threaten our wellness. It was no surprise that the EMR was identified as a clear threat to vascular surgery well-being and that this is not unique to our specialty. Importantly, our membership collectively feels “undervalued” at an institutional level. Specifically given the scope of comprehensive vascular care that we provide patients, a large part of our work includes both unpredictable acute vascular surgical care (such as intraoperative consultations for vascular trauma) and remedial salvage operations to manage vascular complications inflicted during care received from other physicians. This effort leaves us with little control over our time, often without perceived reciprocal clinical support, institutional support, or compensation.

Given this data, the Wellness Task Force is now strategizing efforts for change and supporting ongoing SVS initiatives. Our Task Force is currently:

- Collaborating with key EMR stakeholders with the goal of creating tools that can be shared across the specialty and addressing best practices for system-level support.

- Drafting a “public reply” to the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology’s “Strategy on Reducing Burden Relating to the Use of Health IT and EHRs” initiative.

- Collaborating with national experts to establish peer support tools and SVS networking opportunities that may help members cope with adverse outcomes and strategize the delivery of complex care.

- Identifying institutional best practices for surgeon wellness for broad dissemination.

- Supporting existing SVS initiatives that include the PAC/APM task force, branding initiatives through the PPO as we work to “own our space” and leverage our specialty and the community practice committee as the Society works proactively to optimize workload, fairness, and reward on a larger scale for membership.

We encourage everyone to stay tuned for periodic Vascular Specialist “Wellness Features” and to attend the Wellness Session at the 2019 VAM for interim progress that will feature the following discussions.

- (Re)Finding a meaningful career in vascular surgery.

- Ergonomic challenges to the vascular surgeon and strategies to mitigate the resulting threat of disability.

- EMR best practices to optimize efficiency.

- The role of peer support in vascular surgery, including the mitigation of second victim syndrome.

Surgeon burnout is a real threat to our workforce and the well-being of our colleagues and friends. Risk factors are multifactorial and will require broad, system-level change. The SVS remains fully committed to enhancing vascular surgeon wellness and this Task Force is grateful for your ongoing engagement and support.

Dr. Coleman is an associate professor of vascular surgery at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Physician value thyself!

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines value as “the regard that something is held to deserve; the importance, worth, or usefulness of something” and “relative worth, utility, or importance.” We usually assess our professional worth by how we are treated at work. In social valuing framework, we are given social status based on how others regard us for who we are, what we do, and what we are worth. This is described as “felt worth,” which encapsulates our feelings about how we are regarded by others, in contrast to self-esteem, which is more of an internally held belief.

Our power came from our relationship with our patients and our ability to communicate and influence our patients, peers and administrators. As owners of our practices and small businesses, our currency with hospitals and lawmakers was our ability to bring revenue to hospitals and patient concerns directly to legislators. Practicing in more than one hospital made us more valuable and hospitals battled with each other to provide us and our patients the latest tools and conveniences. In return, we gave our valuable time freely without compensation to hospitals as committee members, task force members, and sounding boards for the betterment of the community. If I were a conspiracy theorist, which I am not, and wanted to devalue physicians I would seek to weaken the physician-patient bond. The way to implement this would be for a single hospital employer to put us on a treadmill chasing work relative value units, give us hard-to-accomplish goals, and keep moving the goalpost. Like I said, I do not believe in conspiracies.

The tsunami of byzantine regulations, Stark laws, and complicated reimbursement formulas has sapped our energy to counter the devaluation. Some are glad to see physicians, particularly surgeons, get their comeuppance because we are perceived as having large egos. This may be true in some instances. Yet, it turns out that the top three job titles with the largest egos are: private household cooks, chief executives, and farm and ranch managers.1

Physicians are also reputed to be possessing dominant leadership styles and seen as bossy and disruptive. Hence, we are made to have frequent training in how to ameliorate our disruptive behavior tendencies. Again, this may be true in a few cases. However, while reports mention how many people witness such unacceptable behavior, there is no valid data about the incidence in practicing physicians. Research also does not support the view that physicians have dominant and aggressive personalities leading to such behavior.

One of the leading interpersonal skills model is Social Styles. We happen to teach this to our faculty at the Ohio State Medical Center’s Faculty Leadership Institute. Turns out that physicians and nurses are almost equally placed into the four quadrants of leadership styles: driving, expressive, amiable, and analytical. I found similar findings in our society members participating in a leadership session I moderated. Indeed, we rank very high on “versatility,” a measure that enables us to adapt our behaviors to fit with our patients and coworkers.

Reported burnout rates of 50% in physicians may or may not be accurate, but burnout is real and so is depression and so are physician suicides. I have witnessed six physician suicides in my career thus far. Teaching resilience, celebrating doctor’s day, and giving out a few awards are all interventions after the fact. Preventive measures like employers and hospitals prioritizing removing daily obstacles eliminating meaningless work, providing more resources to deal with EMRs, and making our lives easier at work, so we can get to our loved ones sooner would help.

Physicians have been largely excluded themselves from participating in the health care debate. We want to see empirical evidence before we sign on to every new proposed care model. Otherwise, we cling on to the status quo and therefore, decision makers tend to leave us out. More important, value-based payment models have not thus far led to reduction in the cost of health care. Despite poor engagement scores at major health systems, physicians are “managed” and sidelined, and mandates are “done to them, not with them.”

In my 40-year career, our devaluation has been a slow and painful process. It started with being called a “provider.” This devalues me. Call me by what I am and do. Physician. Doctor. That is what our patients call us. But, we have been pushed to acquiesce. So, why do physicians undervalue themselves and are unable to be confident of their value to employers and hospital executives?

Some have theorized that physicians have low self-esteem and that denial and rationalization are simply defense mechanisms. The low self-esteem is traced back to medical student days and considered “posttraumatic” disorder. In one study of 189 medical students, 50% reported a decrease in their self-esteem/confidence. The students blamed their residents and attendings for this reaction. Some degree of intimidation may continue into training and employment where it may be part of the culture. We need to change this cycle and treat our students, residents, and mentees with respect as future peers.

Another aspect is related to our own well-being. Most physicians value their patient’s health more than their own. That concept is drilled into us throughout our life. Our spouses complain that we care more about our patients than we do for our families. We often ignore warning signs of serious issues in our own health, always downplaying textbook symptoms of burnout, depression, and even MI. Being too busy is a badge of honor to indicate how successful and wanted we are. This also needs to change.

Sheryl Sandberg in her book “Lean in” discusses the “tiara syndrome,” mainly referring to women. I would suggest that this applies to a lot of physicians, both men and women. Physicians tend to keep their heads down, work hard, and expect someone to come compliment them and place a “tiara” over their head. We may be wary of being called “self-promoters.” Sometimes it is cultural baggage for immigrant physicians who are taught to not brag about their accomplishments. It may behoove us to judiciously make peers and leadership aware of our positive activities in and outside the health system.

Some see physicians not as “pillars of any community,” but as “technicians on an assembly line” or “pawns in a money-making game for hospital administrators.” This degree of pessimism among physicians in surveys is well known but there is good news.

In a 2016 survey based upon responses by 17,236 physicians, 63% were pessimistic or very pessimistic about the medical profession, down from 77% in 2012.2 In another poll, medical doctors were rated as having very high or high ratings of honesty and ethical standards by 65%, higher than all except nurses, military officers, and grade school teachers.3 When the health care debate was at its peak in 2009, a public poll on who they trusted to recommend the right thing for reforming the healthcare system placed physicians at the very top (73%)ahead of health care professors, researchers, hospitals, the President, and politicians. Gallup surveyed 7,000 physicians about engagement in four hierarchical levels: Confidence, Integrity, Pride and Passion. Physicians scored highly on the Pride items in the survey (feel proud to work and being treated with respect).4 In other words, if we are treated well, we feel proud to tell others where we work.

Finally, like many I may consider myself an expert in all sorts of things not relevant to practicing medicine. Yet, I respectfully suggest we stay away from political hot potatoes like nuclear disarmament, gun control, climate change, immigration, and other controversial issues because they distract us from our primary mission. I would hate to see us viewed like Hollywood.

References

1. www.chicagotribune.com/business/ct-payscale-ego-survey-0830-biz-20160829-story.html

2. www.medpagetoday.com/primarycare/generalprimarycare/60446

3. https://nurse.org/articles/gallup-ethical-standards-poll-nurses-rank-highest/

4.https://news.gallup.com/poll/120890/healthcare-americans-trust-physicians-politicians.aspx

Bhagwan Satiani, MD, MBA, is professor of clinical surgery in the division of vascular diseases and surgery at Ohio State University, Columbus. He blogs at www.savvy-medicine.com . Reach him on Twitter @savvycutter.

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines value as “the regard that something is held to deserve; the importance, worth, or usefulness of something” and “relative worth, utility, or importance.” We usually assess our professional worth by how we are treated at work. In social valuing framework, we are given social status based on how others regard us for who we are, what we do, and what we are worth. This is described as “felt worth,” which encapsulates our feelings about how we are regarded by others, in contrast to self-esteem, which is more of an internally held belief.

Our power came from our relationship with our patients and our ability to communicate and influence our patients, peers and administrators. As owners of our practices and small businesses, our currency with hospitals and lawmakers was our ability to bring revenue to hospitals and patient concerns directly to legislators. Practicing in more than one hospital made us more valuable and hospitals battled with each other to provide us and our patients the latest tools and conveniences. In return, we gave our valuable time freely without compensation to hospitals as committee members, task force members, and sounding boards for the betterment of the community. If I were a conspiracy theorist, which I am not, and wanted to devalue physicians I would seek to weaken the physician-patient bond. The way to implement this would be for a single hospital employer to put us on a treadmill chasing work relative value units, give us hard-to-accomplish goals, and keep moving the goalpost. Like I said, I do not believe in conspiracies.

The tsunami of byzantine regulations, Stark laws, and complicated reimbursement formulas has sapped our energy to counter the devaluation. Some are glad to see physicians, particularly surgeons, get their comeuppance because we are perceived as having large egos. This may be true in some instances. Yet, it turns out that the top three job titles with the largest egos are: private household cooks, chief executives, and farm and ranch managers.1

Physicians are also reputed to be possessing dominant leadership styles and seen as bossy and disruptive. Hence, we are made to have frequent training in how to ameliorate our disruptive behavior tendencies. Again, this may be true in a few cases. However, while reports mention how many people witness such unacceptable behavior, there is no valid data about the incidence in practicing physicians. Research also does not support the view that physicians have dominant and aggressive personalities leading to such behavior.

One of the leading interpersonal skills model is Social Styles. We happen to teach this to our faculty at the Ohio State Medical Center’s Faculty Leadership Institute. Turns out that physicians and nurses are almost equally placed into the four quadrants of leadership styles: driving, expressive, amiable, and analytical. I found similar findings in our society members participating in a leadership session I moderated. Indeed, we rank very high on “versatility,” a measure that enables us to adapt our behaviors to fit with our patients and coworkers.

Reported burnout rates of 50% in physicians may or may not be accurate, but burnout is real and so is depression and so are physician suicides. I have witnessed six physician suicides in my career thus far. Teaching resilience, celebrating doctor’s day, and giving out a few awards are all interventions after the fact. Preventive measures like employers and hospitals prioritizing removing daily obstacles eliminating meaningless work, providing more resources to deal with EMRs, and making our lives easier at work, so we can get to our loved ones sooner would help.

Physicians have been largely excluded themselves from participating in the health care debate. We want to see empirical evidence before we sign on to every new proposed care model. Otherwise, we cling on to the status quo and therefore, decision makers tend to leave us out. More important, value-based payment models have not thus far led to reduction in the cost of health care. Despite poor engagement scores at major health systems, physicians are “managed” and sidelined, and mandates are “done to them, not with them.”

In my 40-year career, our devaluation has been a slow and painful process. It started with being called a “provider.” This devalues me. Call me by what I am and do. Physician. Doctor. That is what our patients call us. But, we have been pushed to acquiesce. So, why do physicians undervalue themselves and are unable to be confident of their value to employers and hospital executives?

Some have theorized that physicians have low self-esteem and that denial and rationalization are simply defense mechanisms. The low self-esteem is traced back to medical student days and considered “posttraumatic” disorder. In one study of 189 medical students, 50% reported a decrease in their self-esteem/confidence. The students blamed their residents and attendings for this reaction. Some degree of intimidation may continue into training and employment where it may be part of the culture. We need to change this cycle and treat our students, residents, and mentees with respect as future peers.

Another aspect is related to our own well-being. Most physicians value their patient’s health more than their own. That concept is drilled into us throughout our life. Our spouses complain that we care more about our patients than we do for our families. We often ignore warning signs of serious issues in our own health, always downplaying textbook symptoms of burnout, depression, and even MI. Being too busy is a badge of honor to indicate how successful and wanted we are. This also needs to change.

Sheryl Sandberg in her book “Lean in” discusses the “tiara syndrome,” mainly referring to women. I would suggest that this applies to a lot of physicians, both men and women. Physicians tend to keep their heads down, work hard, and expect someone to come compliment them and place a “tiara” over their head. We may be wary of being called “self-promoters.” Sometimes it is cultural baggage for immigrant physicians who are taught to not brag about their accomplishments. It may behoove us to judiciously make peers and leadership aware of our positive activities in and outside the health system.

Some see physicians not as “pillars of any community,” but as “technicians on an assembly line” or “pawns in a money-making game for hospital administrators.” This degree of pessimism among physicians in surveys is well known but there is good news.

In a 2016 survey based upon responses by 17,236 physicians, 63% were pessimistic or very pessimistic about the medical profession, down from 77% in 2012.2 In another poll, medical doctors were rated as having very high or high ratings of honesty and ethical standards by 65%, higher than all except nurses, military officers, and grade school teachers.3 When the health care debate was at its peak in 2009, a public poll on who they trusted to recommend the right thing for reforming the healthcare system placed physicians at the very top (73%)ahead of health care professors, researchers, hospitals, the President, and politicians. Gallup surveyed 7,000 physicians about engagement in four hierarchical levels: Confidence, Integrity, Pride and Passion. Physicians scored highly on the Pride items in the survey (feel proud to work and being treated with respect).4 In other words, if we are treated well, we feel proud to tell others where we work.

Finally, like many I may consider myself an expert in all sorts of things not relevant to practicing medicine. Yet, I respectfully suggest we stay away from political hot potatoes like nuclear disarmament, gun control, climate change, immigration, and other controversial issues because they distract us from our primary mission. I would hate to see us viewed like Hollywood.

References

1. www.chicagotribune.com/business/ct-payscale-ego-survey-0830-biz-20160829-story.html

2. www.medpagetoday.com/primarycare/generalprimarycare/60446

3. https://nurse.org/articles/gallup-ethical-standards-poll-nurses-rank-highest/

4.https://news.gallup.com/poll/120890/healthcare-americans-trust-physicians-politicians.aspx

Bhagwan Satiani, MD, MBA, is professor of clinical surgery in the division of vascular diseases and surgery at Ohio State University, Columbus. He blogs at www.savvy-medicine.com . Reach him on Twitter @savvycutter.

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines value as “the regard that something is held to deserve; the importance, worth, or usefulness of something” and “relative worth, utility, or importance.” We usually assess our professional worth by how we are treated at work. In social valuing framework, we are given social status based on how others regard us for who we are, what we do, and what we are worth. This is described as “felt worth,” which encapsulates our feelings about how we are regarded by others, in contrast to self-esteem, which is more of an internally held belief.

Our power came from our relationship with our patients and our ability to communicate and influence our patients, peers and administrators. As owners of our practices and small businesses, our currency with hospitals and lawmakers was our ability to bring revenue to hospitals and patient concerns directly to legislators. Practicing in more than one hospital made us more valuable and hospitals battled with each other to provide us and our patients the latest tools and conveniences. In return, we gave our valuable time freely without compensation to hospitals as committee members, task force members, and sounding boards for the betterment of the community. If I were a conspiracy theorist, which I am not, and wanted to devalue physicians I would seek to weaken the physician-patient bond. The way to implement this would be for a single hospital employer to put us on a treadmill chasing work relative value units, give us hard-to-accomplish goals, and keep moving the goalpost. Like I said, I do not believe in conspiracies.

The tsunami of byzantine regulations, Stark laws, and complicated reimbursement formulas has sapped our energy to counter the devaluation. Some are glad to see physicians, particularly surgeons, get their comeuppance because we are perceived as having large egos. This may be true in some instances. Yet, it turns out that the top three job titles with the largest egos are: private household cooks, chief executives, and farm and ranch managers.1

Physicians are also reputed to be possessing dominant leadership styles and seen as bossy and disruptive. Hence, we are made to have frequent training in how to ameliorate our disruptive behavior tendencies. Again, this may be true in a few cases. However, while reports mention how many people witness such unacceptable behavior, there is no valid data about the incidence in practicing physicians. Research also does not support the view that physicians have dominant and aggressive personalities leading to such behavior.

One of the leading interpersonal skills model is Social Styles. We happen to teach this to our faculty at the Ohio State Medical Center’s Faculty Leadership Institute. Turns out that physicians and nurses are almost equally placed into the four quadrants of leadership styles: driving, expressive, amiable, and analytical. I found similar findings in our society members participating in a leadership session I moderated. Indeed, we rank very high on “versatility,” a measure that enables us to adapt our behaviors to fit with our patients and coworkers.

Reported burnout rates of 50% in physicians may or may not be accurate, but burnout is real and so is depression and so are physician suicides. I have witnessed six physician suicides in my career thus far. Teaching resilience, celebrating doctor’s day, and giving out a few awards are all interventions after the fact. Preventive measures like employers and hospitals prioritizing removing daily obstacles eliminating meaningless work, providing more resources to deal with EMRs, and making our lives easier at work, so we can get to our loved ones sooner would help.

Physicians have been largely excluded themselves from participating in the health care debate. We want to see empirical evidence before we sign on to every new proposed care model. Otherwise, we cling on to the status quo and therefore, decision makers tend to leave us out. More important, value-based payment models have not thus far led to reduction in the cost of health care. Despite poor engagement scores at major health systems, physicians are “managed” and sidelined, and mandates are “done to them, not with them.”

In my 40-year career, our devaluation has been a slow and painful process. It started with being called a “provider.” This devalues me. Call me by what I am and do. Physician. Doctor. That is what our patients call us. But, we have been pushed to acquiesce. So, why do physicians undervalue themselves and are unable to be confident of their value to employers and hospital executives?

Some have theorized that physicians have low self-esteem and that denial and rationalization are simply defense mechanisms. The low self-esteem is traced back to medical student days and considered “posttraumatic” disorder. In one study of 189 medical students, 50% reported a decrease in their self-esteem/confidence. The students blamed their residents and attendings for this reaction. Some degree of intimidation may continue into training and employment where it may be part of the culture. We need to change this cycle and treat our students, residents, and mentees with respect as future peers.

Another aspect is related to our own well-being. Most physicians value their patient’s health more than their own. That concept is drilled into us throughout our life. Our spouses complain that we care more about our patients than we do for our families. We often ignore warning signs of serious issues in our own health, always downplaying textbook symptoms of burnout, depression, and even MI. Being too busy is a badge of honor to indicate how successful and wanted we are. This also needs to change.

Sheryl Sandberg in her book “Lean in” discusses the “tiara syndrome,” mainly referring to women. I would suggest that this applies to a lot of physicians, both men and women. Physicians tend to keep their heads down, work hard, and expect someone to come compliment them and place a “tiara” over their head. We may be wary of being called “self-promoters.” Sometimes it is cultural baggage for immigrant physicians who are taught to not brag about their accomplishments. It may behoove us to judiciously make peers and leadership aware of our positive activities in and outside the health system.

Some see physicians not as “pillars of any community,” but as “technicians on an assembly line” or “pawns in a money-making game for hospital administrators.” This degree of pessimism among physicians in surveys is well known but there is good news.

In a 2016 survey based upon responses by 17,236 physicians, 63% were pessimistic or very pessimistic about the medical profession, down from 77% in 2012.2 In another poll, medical doctors were rated as having very high or high ratings of honesty and ethical standards by 65%, higher than all except nurses, military officers, and grade school teachers.3 When the health care debate was at its peak in 2009, a public poll on who they trusted to recommend the right thing for reforming the healthcare system placed physicians at the very top (73%)ahead of health care professors, researchers, hospitals, the President, and politicians. Gallup surveyed 7,000 physicians about engagement in four hierarchical levels: Confidence, Integrity, Pride and Passion. Physicians scored highly on the Pride items in the survey (feel proud to work and being treated with respect).4 In other words, if we are treated well, we feel proud to tell others where we work.

Finally, like many I may consider myself an expert in all sorts of things not relevant to practicing medicine. Yet, I respectfully suggest we stay away from political hot potatoes like nuclear disarmament, gun control, climate change, immigration, and other controversial issues because they distract us from our primary mission. I would hate to see us viewed like Hollywood.

References

1. www.chicagotribune.com/business/ct-payscale-ego-survey-0830-biz-20160829-story.html

2. www.medpagetoday.com/primarycare/generalprimarycare/60446

3. https://nurse.org/articles/gallup-ethical-standards-poll-nurses-rank-highest/

4.https://news.gallup.com/poll/120890/healthcare-americans-trust-physicians-politicians.aspx

Bhagwan Satiani, MD, MBA, is professor of clinical surgery in the division of vascular diseases and surgery at Ohio State University, Columbus. He blogs at www.savvy-medicine.com . Reach him on Twitter @savvycutter.

Knee and elbow rejuvenation

The cosmetic industry improves techniques for tightening faces, hands, necks, and decolletes; meanwhile, sagging elbows and knees, once ignored, also are a visible sign of aging. Modifying techniques commonly used for the face and neck can yield significant improvements in the elbows and knees. The elbows and knees naturally have looser skin to allow for joint movement; over time, the skin over these joints is exposed to sun damage, friction, and recurrent extension and flexion, which cause skin laxity and aging.

A combination approach addressing skin texture, collagen damage, rhytides, and fat deposition is the most effective method for knee and elbow rejuvenation.

For knees and elbows with loose skin and rhytides, in-office noninvasive and minimally invasive radio-frequency and light energy treatments are helpful in increasing collagen production and tissue tightening. Similarly, microfocused ultrasound has been shown to be a safe and effective skin tightening treatment for the knees. In comparison to the face, however, the skin around the elbows and knees can be thinner and has fewer sebaceous glands. Caution should be used particularly with minimally invasive radio-frequency techniques in order to protect the epidermal skin. Often, treatments have to be repeated to give optimal results, which are not apparent until 3-6 months after the initial procedure.

For knee skin with severe laxity, a comprehensive approach using polydioxanone (PDO) or poly-l-lactic acid (PLLA) threads in both the upper thighs and circumferentially around the knees provides collagen production and tightening of the loose skin. Treatment of the upper thighs is essential in providing a vector that lifts the skin of the knees. Treatments can be repeated, with results seen after 90 days. Thread lifts of the knees and thighs are highly effective, noninvasive procedures with little to no downtime and can be used for severe skin laxity, wrinkling, and thinning of the knee skin.

Loose, roughened knee and elbow skin can also be treated with nonablative factional resurfacing, radio-frequency microneedling, or a series of monthly treatments with PLLA and hyaluronic acid fillers injected in the superficial to mid-dermis. Both fractional resurfacing and dermal filler injections help stimulate collagen production and improve both fine rhytides and dermatoheliosis.

Adipose tissue around the knees can be treated with monthly deoxycholic acid injections (for a video of this procedure, go to https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rhw-nESy15AoDhKUrc25DDjKEun7RL4i/view). The volume of injection, however, is significantly higher than that recommended in the submental area. Two to four times the volume is needed per knee over a series of 3-6 treatments, depending on the amount of fat in the knees.

Cryolipolysis is also an effective option for fat pockets around the knees; however, in my experience, it can be difficult to fit the applicators onto the area of concern appropriately unless smaller applicators are applied.

With the increasing demand for body rejuvenation techniques, providers are adapting techniques used for the face and neck to lift, tighten, thin, and sculpt the knees and elbows. A combination approach using lasers, ultrasound, fillers, threads, and cryolipolysis can be effective for these areas. Results are obtainable when repeat treatments are performed; however, one must be patient because results are not seen for 6 months or more.

Dr. Lily Talakoub and Dr. Naissan Wesley are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

Macedo O. et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(Suppl 1), Abstract P800, page AB193.

The cosmetic industry improves techniques for tightening faces, hands, necks, and decolletes; meanwhile, sagging elbows and knees, once ignored, also are a visible sign of aging. Modifying techniques commonly used for the face and neck can yield significant improvements in the elbows and knees. The elbows and knees naturally have looser skin to allow for joint movement; over time, the skin over these joints is exposed to sun damage, friction, and recurrent extension and flexion, which cause skin laxity and aging.

A combination approach addressing skin texture, collagen damage, rhytides, and fat deposition is the most effective method for knee and elbow rejuvenation.

For knees and elbows with loose skin and rhytides, in-office noninvasive and minimally invasive radio-frequency and light energy treatments are helpful in increasing collagen production and tissue tightening. Similarly, microfocused ultrasound has been shown to be a safe and effective skin tightening treatment for the knees. In comparison to the face, however, the skin around the elbows and knees can be thinner and has fewer sebaceous glands. Caution should be used particularly with minimally invasive radio-frequency techniques in order to protect the epidermal skin. Often, treatments have to be repeated to give optimal results, which are not apparent until 3-6 months after the initial procedure.

For knee skin with severe laxity, a comprehensive approach using polydioxanone (PDO) or poly-l-lactic acid (PLLA) threads in both the upper thighs and circumferentially around the knees provides collagen production and tightening of the loose skin. Treatment of the upper thighs is essential in providing a vector that lifts the skin of the knees. Treatments can be repeated, with results seen after 90 days. Thread lifts of the knees and thighs are highly effective, noninvasive procedures with little to no downtime and can be used for severe skin laxity, wrinkling, and thinning of the knee skin.

Loose, roughened knee and elbow skin can also be treated with nonablative factional resurfacing, radio-frequency microneedling, or a series of monthly treatments with PLLA and hyaluronic acid fillers injected in the superficial to mid-dermis. Both fractional resurfacing and dermal filler injections help stimulate collagen production and improve both fine rhytides and dermatoheliosis.

Adipose tissue around the knees can be treated with monthly deoxycholic acid injections (for a video of this procedure, go to https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rhw-nESy15AoDhKUrc25DDjKEun7RL4i/view). The volume of injection, however, is significantly higher than that recommended in the submental area. Two to four times the volume is needed per knee over a series of 3-6 treatments, depending on the amount of fat in the knees.

Cryolipolysis is also an effective option for fat pockets around the knees; however, in my experience, it can be difficult to fit the applicators onto the area of concern appropriately unless smaller applicators are applied.

With the increasing demand for body rejuvenation techniques, providers are adapting techniques used for the face and neck to lift, tighten, thin, and sculpt the knees and elbows. A combination approach using lasers, ultrasound, fillers, threads, and cryolipolysis can be effective for these areas. Results are obtainable when repeat treatments are performed; however, one must be patient because results are not seen for 6 months or more.

Dr. Lily Talakoub and Dr. Naissan Wesley are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

Macedo O. et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(Suppl 1), Abstract P800, page AB193.

The cosmetic industry improves techniques for tightening faces, hands, necks, and decolletes; meanwhile, sagging elbows and knees, once ignored, also are a visible sign of aging. Modifying techniques commonly used for the face and neck can yield significant improvements in the elbows and knees. The elbows and knees naturally have looser skin to allow for joint movement; over time, the skin over these joints is exposed to sun damage, friction, and recurrent extension and flexion, which cause skin laxity and aging.

A combination approach addressing skin texture, collagen damage, rhytides, and fat deposition is the most effective method for knee and elbow rejuvenation.

For knees and elbows with loose skin and rhytides, in-office noninvasive and minimally invasive radio-frequency and light energy treatments are helpful in increasing collagen production and tissue tightening. Similarly, microfocused ultrasound has been shown to be a safe and effective skin tightening treatment for the knees. In comparison to the face, however, the skin around the elbows and knees can be thinner and has fewer sebaceous glands. Caution should be used particularly with minimally invasive radio-frequency techniques in order to protect the epidermal skin. Often, treatments have to be repeated to give optimal results, which are not apparent until 3-6 months after the initial procedure.

For knee skin with severe laxity, a comprehensive approach using polydioxanone (PDO) or poly-l-lactic acid (PLLA) threads in both the upper thighs and circumferentially around the knees provides collagen production and tightening of the loose skin. Treatment of the upper thighs is essential in providing a vector that lifts the skin of the knees. Treatments can be repeated, with results seen after 90 days. Thread lifts of the knees and thighs are highly effective, noninvasive procedures with little to no downtime and can be used for severe skin laxity, wrinkling, and thinning of the knee skin.

Loose, roughened knee and elbow skin can also be treated with nonablative factional resurfacing, radio-frequency microneedling, or a series of monthly treatments with PLLA and hyaluronic acid fillers injected in the superficial to mid-dermis. Both fractional resurfacing and dermal filler injections help stimulate collagen production and improve both fine rhytides and dermatoheliosis.

Adipose tissue around the knees can be treated with monthly deoxycholic acid injections (for a video of this procedure, go to https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rhw-nESy15AoDhKUrc25DDjKEun7RL4i/view). The volume of injection, however, is significantly higher than that recommended in the submental area. Two to four times the volume is needed per knee over a series of 3-6 treatments, depending on the amount of fat in the knees.

Cryolipolysis is also an effective option for fat pockets around the knees; however, in my experience, it can be difficult to fit the applicators onto the area of concern appropriately unless smaller applicators are applied.

With the increasing demand for body rejuvenation techniques, providers are adapting techniques used for the face and neck to lift, tighten, thin, and sculpt the knees and elbows. A combination approach using lasers, ultrasound, fillers, threads, and cryolipolysis can be effective for these areas. Results are obtainable when repeat treatments are performed; however, one must be patient because results are not seen for 6 months or more.

Dr. Lily Talakoub and Dr. Naissan Wesley are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

Macedo O. et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(Suppl 1), Abstract P800, page AB193.

Report criticizes VA’s suicide prevention efforts; author shares depression-fighting strategies

The suicide rate among veterans is almost double that of the general American population. It has been rising among those who served in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Rep. Tim Walz, the Minnesota Democrat who requested the investigation, reportedly said in a statement. “Unfortunately, VA failed to do that.”

Mr. Walz was referring to a failure in prevention efforts that was detailed in a Government Accountability Office report released recently and was the subject of an article in the New York Times. The report blames bureaucratic confusion and an absence of leadership – epitomized by several department vacancies.

“This is such an important issue; we need to be throwing everything we can at it,” said Caitin Thompson, PhD. She was director of the VA’s suicide prevention efforts but resigned in frustration in mid-2017. “It’s so ludicrous that money would be sitting on the table. Outreach is one of the first ways to engage with veterans and families about ways to get help. If we don’t have that, what do we have?”

Surviving the holidays with depression

The postcard image of the Christmas season is that of joyous celebration with family and friends. For many people, however, this image is false. Many complain about feelings of stress imposed by familial obligations, pressure to conform to those postcard myths, and the financial toll that all of that holiday largesse can exact.

Now add depression to this mix. How can those burdened by depression find some joy at this time of year? In a recent article in the Huffington Post, author Andrea Loewen advises staying away from social media and focusing on the positive.

“[Social media] is a double-edged sword: Either I see all the amazing things everyone else is doing and feel jealous/insignificant/left out, or I see that no one else is really posting and assume they must be too busy having incredible quality time with their families while I’m the unengaged loser scrolling Instagram,” Ms. Loewen wrote. “Either way, it’s bad news.”

One concrete practice that she engages in is taking a few minutes to think about and write down the positive things that happened each day.

“The list includes everything, big and small: from the thoughtful gift I wasn’t expecting to the simple observation that a friend seemed happy to see me,” Ms. Loewen wrote. “Depending on where I’m at in my depression, those seemingly tiny details can be vital reminders I hold a valuable place in the world.”

Artist perpetuates persistent myth

In some ways, Kanye West embraces his diagnosis of bipolar disorder. He calls the illness his “superpower,” and the art on his new album, “Ye,” includes the phrase: “I hate being Bi-Polar/it’s awesome.” But his decision to abandon his medications promotes a myth, Amanda Mull wrote in an opinion piece in the Atlantic.

“In apparently quitting his psychiatric medication for the sake of his creativity, Mr. West is promoting one of mental health’s most persistent and dangerous myths: that suffering is necessary for great art,” Ms. Mull wrote.

Philip R. Muskin, MD, who is affiliated with the department of psychiatry at Columbia University in New York, agreed that linking mental turmoil with creative genius is indeed problematic. “Creative people are not creative when they’re depressed, or so manic that no one can tolerate being with them and they start to merge into psychosis, or when they’re filled with numbing anxiety,” he said in the Atlantic article.

Esmé Weijun Wang concurred and offered a counterview to that of Mr. West. A novelist who has written about living with schizoaffective disorder, she said: “It may be true that mental illness has given me insights with which to work, creatively speaking, but it’s also made me too sick to use that creativity. The voice in my head that says, ‘Die, die, die’ is not a voice that encourages putting together a short story.”

For his part, Mr. West’s decision to stop taking his medicine threatens to undermine his own mental health. And his public musings could drive others away from treatment.

“Antiopioid backlash” causes pain

An article by Fox News has highlighted the daily toll that opioid addiction is exacting on Americans. Government efforts aimed at quelling the use of opioids by targeting availability have had the unintended consequence of the cut-off of prescriptions by many physicians. With that route turned off, many people are turning to other sources for pain relief – or are being left with no relief.

One person in the article related how his wife is unable to obtain pain relief for her neurologic and spinal diseases. “A welcome death has become a discussion,” he said.

Meanwhile, a 69-year-old veteran said the Department of Veterans Affairs ended his pain medication. “I now buy heroin on the street.”

Another person in the article, Herb Erne III, wrote: “As a nurse, I have seen addicts and the other end of opioid abuse. But there is another side to this crisis that people are not talking about, those that actually need pain medications but cannot get them because of the ‘fear factor’ of running afoul of the antiopioid – including legal ones taken safely under medical supervision – backlash.

“The chronically ill who do not abuse, who do not divert, have become the unintended victims of misguided and overzealous efforts by policy- and regulation-making bodies in the government,” he said.

Grandparents filling void

An article in the Detroit News reported on more carnage of the opioid crisis. In Michigan and elsewhere nationwide, increasing numbers of parents with opioid addiction are unable to safely care for their children or have died because of an overdose. Grandparents are stepping in to assume care.

Results of a national survey involving more than 1,000 grandparents found that 20% are the daily caregivers to their grandchildren. They can be on their own, without any financial aid from state or national programs. Other children without grandparents can be diverted to foster care.

It’s a role few grandparents anticipated. “Our system as a whole is messed up. It tears at my heart,” 47-year-old Christina Wasilewski said in the article. “Everyone keeps saying children are resilient, but only to a point.”

Ms. Wasilewski and her husband assumed care for their granddaughter when they discovered her in physical distress from lack of care.

In Michigan, the increase in the rate of opioid-related deaths slowed in 2017 but deaths still rose 9% from 2016 , according to the Michigan Department of Health & Human Services. The prior year the death rate was 35%. In Michigan, grandparents raising their grandchildren do not have legal parental rights for this care, including the right to seek medical care and to pursue educational options.

Ms. Wasilewski’s concern about these trends led her to launch the Caregiver Cafe, a support group for grandparents raising their grandchildren.

The suicide rate among veterans is almost double that of the general American population. It has been rising among those who served in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Rep. Tim Walz, the Minnesota Democrat who requested the investigation, reportedly said in a statement. “Unfortunately, VA failed to do that.”

Mr. Walz was referring to a failure in prevention efforts that was detailed in a Government Accountability Office report released recently and was the subject of an article in the New York Times. The report blames bureaucratic confusion and an absence of leadership – epitomized by several department vacancies.

“This is such an important issue; we need to be throwing everything we can at it,” said Caitin Thompson, PhD. She was director of the VA’s suicide prevention efforts but resigned in frustration in mid-2017. “It’s so ludicrous that money would be sitting on the table. Outreach is one of the first ways to engage with veterans and families about ways to get help. If we don’t have that, what do we have?”

Surviving the holidays with depression

The postcard image of the Christmas season is that of joyous celebration with family and friends. For many people, however, this image is false. Many complain about feelings of stress imposed by familial obligations, pressure to conform to those postcard myths, and the financial toll that all of that holiday largesse can exact.

Now add depression to this mix. How can those burdened by depression find some joy at this time of year? In a recent article in the Huffington Post, author Andrea Loewen advises staying away from social media and focusing on the positive.

“[Social media] is a double-edged sword: Either I see all the amazing things everyone else is doing and feel jealous/insignificant/left out, or I see that no one else is really posting and assume they must be too busy having incredible quality time with their families while I’m the unengaged loser scrolling Instagram,” Ms. Loewen wrote. “Either way, it’s bad news.”

One concrete practice that she engages in is taking a few minutes to think about and write down the positive things that happened each day.

“The list includes everything, big and small: from the thoughtful gift I wasn’t expecting to the simple observation that a friend seemed happy to see me,” Ms. Loewen wrote. “Depending on where I’m at in my depression, those seemingly tiny details can be vital reminders I hold a valuable place in the world.”

Artist perpetuates persistent myth

In some ways, Kanye West embraces his diagnosis of bipolar disorder. He calls the illness his “superpower,” and the art on his new album, “Ye,” includes the phrase: “I hate being Bi-Polar/it’s awesome.” But his decision to abandon his medications promotes a myth, Amanda Mull wrote in an opinion piece in the Atlantic.

“In apparently quitting his psychiatric medication for the sake of his creativity, Mr. West is promoting one of mental health’s most persistent and dangerous myths: that suffering is necessary for great art,” Ms. Mull wrote.

Philip R. Muskin, MD, who is affiliated with the department of psychiatry at Columbia University in New York, agreed that linking mental turmoil with creative genius is indeed problematic. “Creative people are not creative when they’re depressed, or so manic that no one can tolerate being with them and they start to merge into psychosis, or when they’re filled with numbing anxiety,” he said in the Atlantic article.

Esmé Weijun Wang concurred and offered a counterview to that of Mr. West. A novelist who has written about living with schizoaffective disorder, she said: “It may be true that mental illness has given me insights with which to work, creatively speaking, but it’s also made me too sick to use that creativity. The voice in my head that says, ‘Die, die, die’ is not a voice that encourages putting together a short story.”

For his part, Mr. West’s decision to stop taking his medicine threatens to undermine his own mental health. And his public musings could drive others away from treatment.

“Antiopioid backlash” causes pain

An article by Fox News has highlighted the daily toll that opioid addiction is exacting on Americans. Government efforts aimed at quelling the use of opioids by targeting availability have had the unintended consequence of the cut-off of prescriptions by many physicians. With that route turned off, many people are turning to other sources for pain relief – or are being left with no relief.

One person in the article related how his wife is unable to obtain pain relief for her neurologic and spinal diseases. “A welcome death has become a discussion,” he said.

Meanwhile, a 69-year-old veteran said the Department of Veterans Affairs ended his pain medication. “I now buy heroin on the street.”

Another person in the article, Herb Erne III, wrote: “As a nurse, I have seen addicts and the other end of opioid abuse. But there is another side to this crisis that people are not talking about, those that actually need pain medications but cannot get them because of the ‘fear factor’ of running afoul of the antiopioid – including legal ones taken safely under medical supervision – backlash.

“The chronically ill who do not abuse, who do not divert, have become the unintended victims of misguided and overzealous efforts by policy- and regulation-making bodies in the government,” he said.

Grandparents filling void

An article in the Detroit News reported on more carnage of the opioid crisis. In Michigan and elsewhere nationwide, increasing numbers of parents with opioid addiction are unable to safely care for their children or have died because of an overdose. Grandparents are stepping in to assume care.

Results of a national survey involving more than 1,000 grandparents found that 20% are the daily caregivers to their grandchildren. They can be on their own, without any financial aid from state or national programs. Other children without grandparents can be diverted to foster care.

It’s a role few grandparents anticipated. “Our system as a whole is messed up. It tears at my heart,” 47-year-old Christina Wasilewski said in the article. “Everyone keeps saying children are resilient, but only to a point.”

Ms. Wasilewski and her husband assumed care for their granddaughter when they discovered her in physical distress from lack of care.

In Michigan, the increase in the rate of opioid-related deaths slowed in 2017 but deaths still rose 9% from 2016 , according to the Michigan Department of Health & Human Services. The prior year the death rate was 35%. In Michigan, grandparents raising their grandchildren do not have legal parental rights for this care, including the right to seek medical care and to pursue educational options.

Ms. Wasilewski’s concern about these trends led her to launch the Caregiver Cafe, a support group for grandparents raising their grandchildren.

The suicide rate among veterans is almost double that of the general American population. It has been rising among those who served in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Rep. Tim Walz, the Minnesota Democrat who requested the investigation, reportedly said in a statement. “Unfortunately, VA failed to do that.”

Mr. Walz was referring to a failure in prevention efforts that was detailed in a Government Accountability Office report released recently and was the subject of an article in the New York Times. The report blames bureaucratic confusion and an absence of leadership – epitomized by several department vacancies.

“This is such an important issue; we need to be throwing everything we can at it,” said Caitin Thompson, PhD. She was director of the VA’s suicide prevention efforts but resigned in frustration in mid-2017. “It’s so ludicrous that money would be sitting on the table. Outreach is one of the first ways to engage with veterans and families about ways to get help. If we don’t have that, what do we have?”

Surviving the holidays with depression

The postcard image of the Christmas season is that of joyous celebration with family and friends. For many people, however, this image is false. Many complain about feelings of stress imposed by familial obligations, pressure to conform to those postcard myths, and the financial toll that all of that holiday largesse can exact.

Now add depression to this mix. How can those burdened by depression find some joy at this time of year? In a recent article in the Huffington Post, author Andrea Loewen advises staying away from social media and focusing on the positive.

“[Social media] is a double-edged sword: Either I see all the amazing things everyone else is doing and feel jealous/insignificant/left out, or I see that no one else is really posting and assume they must be too busy having incredible quality time with their families while I’m the unengaged loser scrolling Instagram,” Ms. Loewen wrote. “Either way, it’s bad news.”

One concrete practice that she engages in is taking a few minutes to think about and write down the positive things that happened each day.

“The list includes everything, big and small: from the thoughtful gift I wasn’t expecting to the simple observation that a friend seemed happy to see me,” Ms. Loewen wrote. “Depending on where I’m at in my depression, those seemingly tiny details can be vital reminders I hold a valuable place in the world.”

Artist perpetuates persistent myth

In some ways, Kanye West embraces his diagnosis of bipolar disorder. He calls the illness his “superpower,” and the art on his new album, “Ye,” includes the phrase: “I hate being Bi-Polar/it’s awesome.” But his decision to abandon his medications promotes a myth, Amanda Mull wrote in an opinion piece in the Atlantic.

“In apparently quitting his psychiatric medication for the sake of his creativity, Mr. West is promoting one of mental health’s most persistent and dangerous myths: that suffering is necessary for great art,” Ms. Mull wrote.

Philip R. Muskin, MD, who is affiliated with the department of psychiatry at Columbia University in New York, agreed that linking mental turmoil with creative genius is indeed problematic. “Creative people are not creative when they’re depressed, or so manic that no one can tolerate being with them and they start to merge into psychosis, or when they’re filled with numbing anxiety,” he said in the Atlantic article.

Esmé Weijun Wang concurred and offered a counterview to that of Mr. West. A novelist who has written about living with schizoaffective disorder, she said: “It may be true that mental illness has given me insights with which to work, creatively speaking, but it’s also made me too sick to use that creativity. The voice in my head that says, ‘Die, die, die’ is not a voice that encourages putting together a short story.”

For his part, Mr. West’s decision to stop taking his medicine threatens to undermine his own mental health. And his public musings could drive others away from treatment.

“Antiopioid backlash” causes pain