User login

Clinical Edge Journal Scan Commentary: Multiple Sclerosis March 2022

Clinical Edge Journal Scan Commentary: Prenatal Testing March 2022

Many neurocognitive disorders only present a phenotype after birth. Sukenik-Halevy et al sought to examine the ability to detect prenatal phenotypes in patients with a postnatally diagnosed neurocognitive syndrome and confirmed genetic diagnosis on ES. The team was not able to identify any specific prenatal phenotype associated with their cases of postnatally diagnosed neurocognitive syndromes. The interesting finding of this study is that, of the 122 patients studied, 35.3% (43) had no abnormal sonographic findings that could have been detected prenatally to suggest the need for ES testing. ES is typically used in a prenatal setting for fetuses with anomalies that have a normal KT and CMA. The results of this study raise the question of offering ES to all patients considering diagnostic genetic testing regardless of the indication, as it may be the only way to diagnose some cases of neurocognitive disorders prenatally.

Cell-free fetal DNA (cff DNA) testing for trisomy 21, 18, and 13 has classically be used for high-risk pregnant patients seeking aneuploidy screening. Dar et al sought to examine this type of testing in a low-risk population. They studied, prospectively, the performance of cff DNA testing for trisomy 21, 18, and 13 in both low and high-risk pregnant women with confirmation of results on diagnostic genetic testing. Negative predictive values (NPV) for both the low and high-risk groups were greater than 99.9%. Positive predictive value (PPV) was lower for the low-risk group in comparison to the high-risk group, with it important to note that PPV drops from 96.4% in the high-risk group to 81.8% in the low-risk group for trisomy 21. This means that low-risk patients with a positive result on cff DNA testing are at a higher risk for a false positive than patients at high-risk for an aneuploid fetus. This study shows the mounting evidence that cff DNA can be used in a low-risk population given the high NPV. Providers do still need to note the lower PPV with low-risk population patients and always offer diagnostic genetic testing with any abnormal cff DNA test result.

Many neurocognitive disorders only present a phenotype after birth. Sukenik-Halevy et al sought to examine the ability to detect prenatal phenotypes in patients with a postnatally diagnosed neurocognitive syndrome and confirmed genetic diagnosis on ES. The team was not able to identify any specific prenatal phenotype associated with their cases of postnatally diagnosed neurocognitive syndromes. The interesting finding of this study is that, of the 122 patients studied, 35.3% (43) had no abnormal sonographic findings that could have been detected prenatally to suggest the need for ES testing. ES is typically used in a prenatal setting for fetuses with anomalies that have a normal KT and CMA. The results of this study raise the question of offering ES to all patients considering diagnostic genetic testing regardless of the indication, as it may be the only way to diagnose some cases of neurocognitive disorders prenatally.

Cell-free fetal DNA (cff DNA) testing for trisomy 21, 18, and 13 has classically be used for high-risk pregnant patients seeking aneuploidy screening. Dar et al sought to examine this type of testing in a low-risk population. They studied, prospectively, the performance of cff DNA testing for trisomy 21, 18, and 13 in both low and high-risk pregnant women with confirmation of results on diagnostic genetic testing. Negative predictive values (NPV) for both the low and high-risk groups were greater than 99.9%. Positive predictive value (PPV) was lower for the low-risk group in comparison to the high-risk group, with it important to note that PPV drops from 96.4% in the high-risk group to 81.8% in the low-risk group for trisomy 21. This means that low-risk patients with a positive result on cff DNA testing are at a higher risk for a false positive than patients at high-risk for an aneuploid fetus. This study shows the mounting evidence that cff DNA can be used in a low-risk population given the high NPV. Providers do still need to note the lower PPV with low-risk population patients and always offer diagnostic genetic testing with any abnormal cff DNA test result.

Many neurocognitive disorders only present a phenotype after birth. Sukenik-Halevy et al sought to examine the ability to detect prenatal phenotypes in patients with a postnatally diagnosed neurocognitive syndrome and confirmed genetic diagnosis on ES. The team was not able to identify any specific prenatal phenotype associated with their cases of postnatally diagnosed neurocognitive syndromes. The interesting finding of this study is that, of the 122 patients studied, 35.3% (43) had no abnormal sonographic findings that could have been detected prenatally to suggest the need for ES testing. ES is typically used in a prenatal setting for fetuses with anomalies that have a normal KT and CMA. The results of this study raise the question of offering ES to all patients considering diagnostic genetic testing regardless of the indication, as it may be the only way to diagnose some cases of neurocognitive disorders prenatally.

Cell-free fetal DNA (cff DNA) testing for trisomy 21, 18, and 13 has classically be used for high-risk pregnant patients seeking aneuploidy screening. Dar et al sought to examine this type of testing in a low-risk population. They studied, prospectively, the performance of cff DNA testing for trisomy 21, 18, and 13 in both low and high-risk pregnant women with confirmation of results on diagnostic genetic testing. Negative predictive values (NPV) for both the low and high-risk groups were greater than 99.9%. Positive predictive value (PPV) was lower for the low-risk group in comparison to the high-risk group, with it important to note that PPV drops from 96.4% in the high-risk group to 81.8% in the low-risk group for trisomy 21. This means that low-risk patients with a positive result on cff DNA testing are at a higher risk for a false positive than patients at high-risk for an aneuploid fetus. This study shows the mounting evidence that cff DNA can be used in a low-risk population given the high NPV. Providers do still need to note the lower PPV with low-risk population patients and always offer diagnostic genetic testing with any abnormal cff DNA test result.

Treatment of Elephantiasic Pretibial Myxedema With Rituximab Therapy

To the Editor:

Pretibial myxedema (PTM) is bilateral, nonpitting, scaly thickening and induration of the skin that most commonly occurs on the anterior aspects of the legs and feet. Pretibial myxedema occurs in approximately 0.5% to 4.3% of patients with hyperthyroidism.1 Thyroid dermopathy often is thought of as the classic nonpitting PTM with skin induration and color change. However, rarer forms of PTM, including plaque, nodular, and elephantiasic, also are important to note.2

Elephantiasic PTM is extremely rare, occurring in less than 1% of patients with PTM.2 Elephantiasic PTM is characterized by the persistent swelling of 1 or both legs; thickening of the skin overlying the dorsum of the feet, ankles, and toes; and verrucous irregular plaques that often are fleshy and flattened. The clinical differential diagnosis of elephantiasic PTM includes elephantiasis nostra verrucosa, a late-stage complication of chronic lymphedema that can be related to a variety of infectious or noninfectious obstructive processes. Few effective therapeutic modalities exist in the treatment of elephantiasic PTM. We present a case of elephantiasic PTM.

A 59-year-old man presented to dermatology with leonine facies with pronounced glabellar creases and indentations of the earlobes. He had diffuse woody induration, hyperpigmentation, and nonpitting edema of the lower extremities as well as several flesh-colored exophytic nodules scattered throughout the anterior shins and dorsal feet (Figure 1). On the left posterior calf, there was a large, 3-cm, exophytic, firm, flesh-colored nodule. Examination of the hands revealed mild hyperpigmentation of the distal digits, clubbing of the distal phalanges, and cheiroarthropathy.

The patient was diagnosed with Graves disease after experiencing the classic symptoms of hyperthyroidism, including heat intolerance, tremor, palpitations, and anxiety. He received thyroid ablation and subsequently was supplemented with levothyroxine 75 mg daily. Twelve years later, he was diagnosed with Graves ophthalmopathy with ocular proptosis requiring multiple courses of retro-orbital irradiation and surgical procedures for decompression. Approximately 1 year later, he noted increased swelling, firmness, and darkening of the pretibial surfaces. Initially, he was referred to vascular surgery and underwent bilateral saphenous vein ablation. He also was referred to a lymphedema specialist, and workup revealed an unremarkable lymphatic system. Minimal improvement was noted following the saphenous vein ablation, and he subsequently was referred to dermatology for further workup.

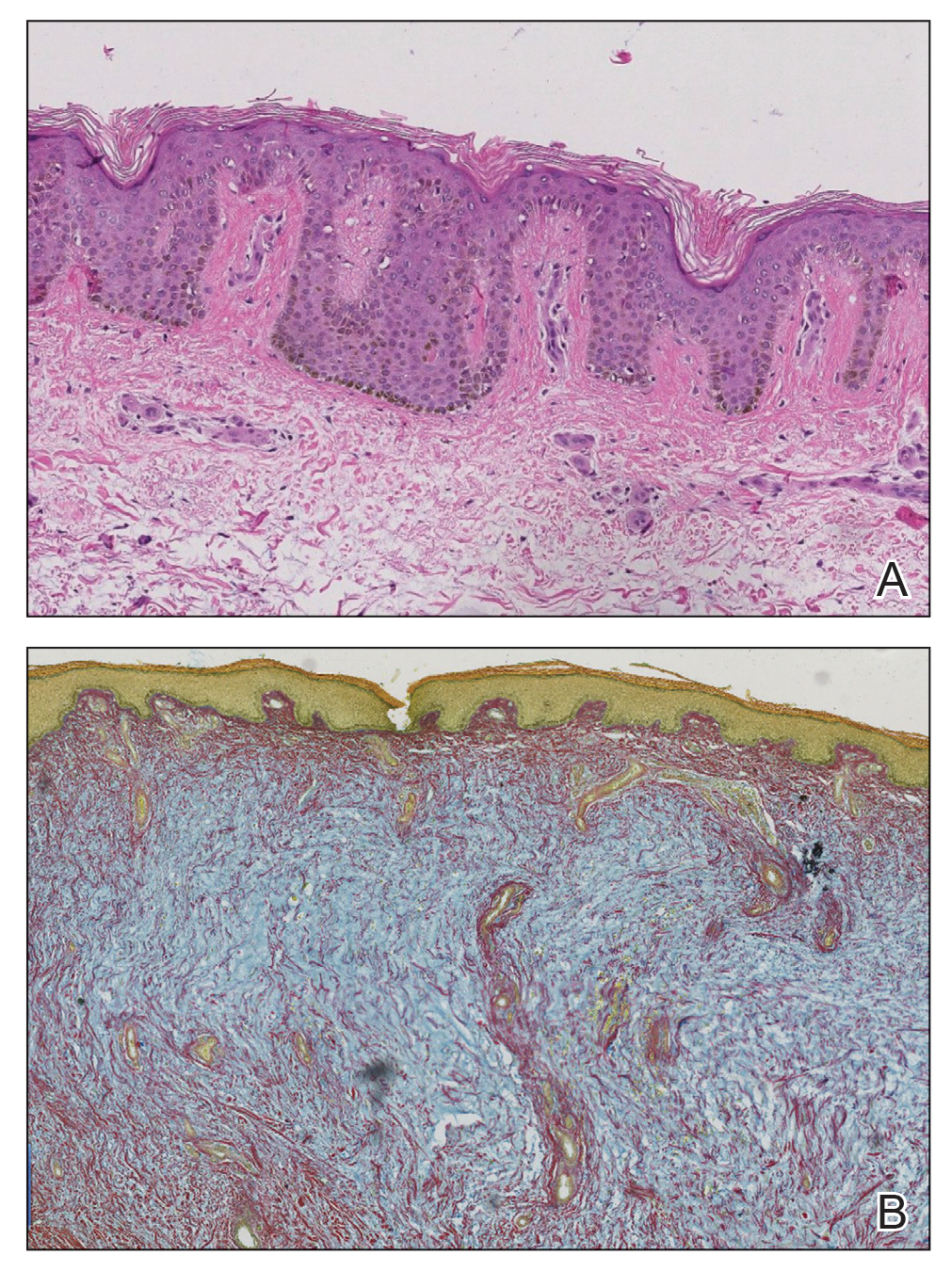

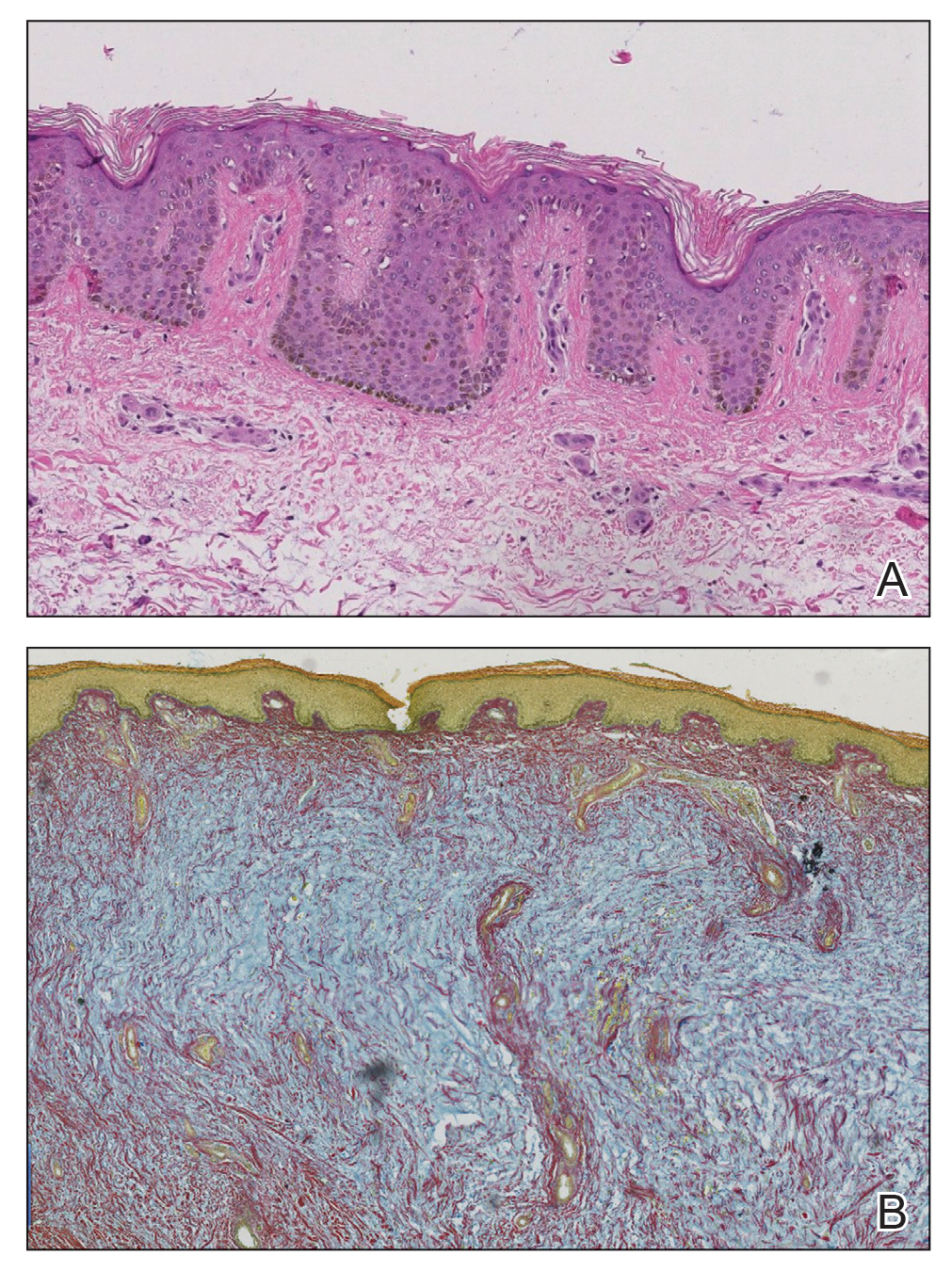

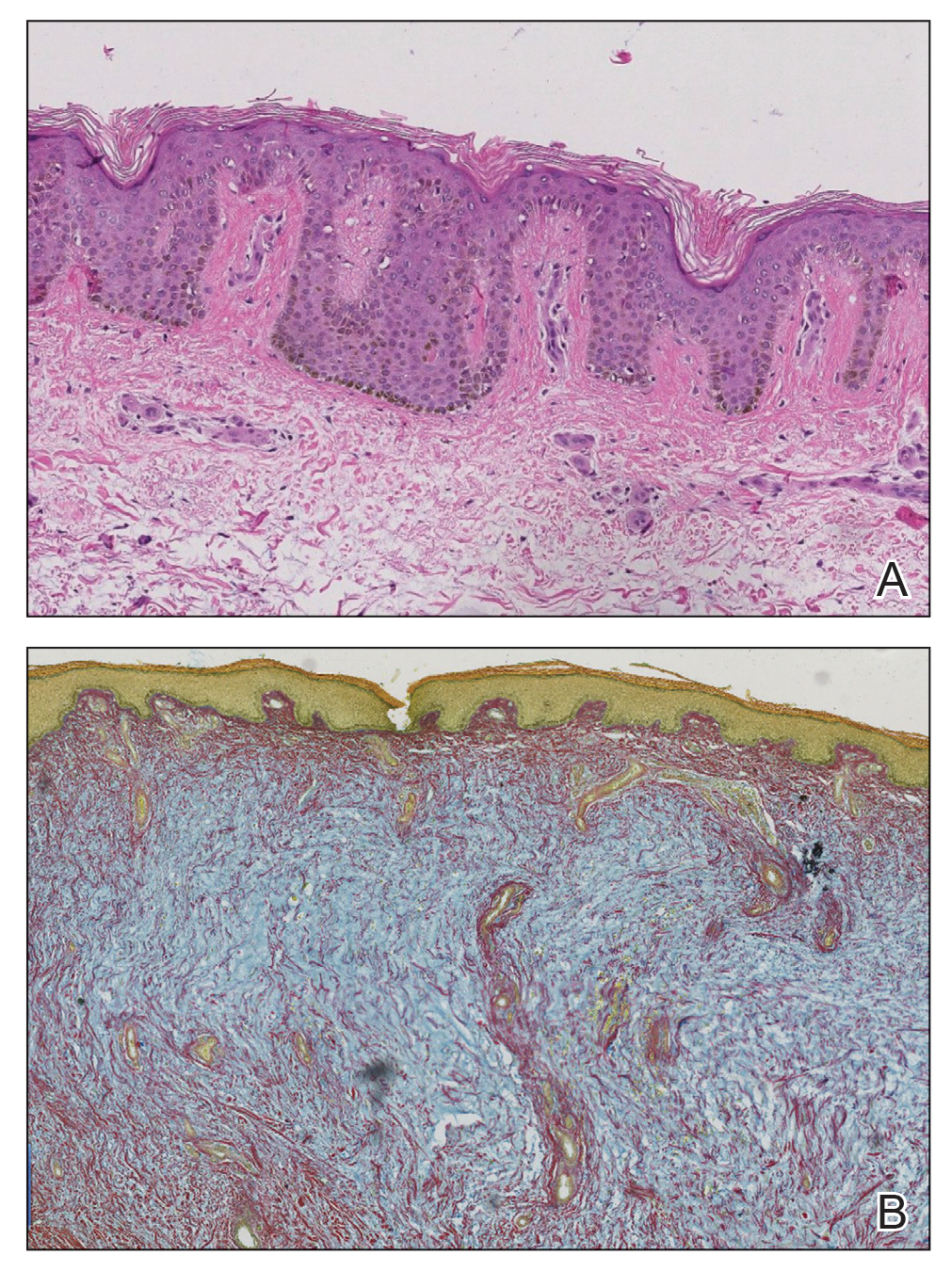

At the current presentation, laboratory analysis revealed a low thyrotropin level (0.03 mIU/L [reference range, 0.4–4.2 mIU/L]), and free thyroxine was within reference range. Radiography of the chest was unremarkable; however, radiography of the hand demonstrated arthrosis of the left fifth proximal interphalangeal joint. Nuclear medicine lymphoscintigraphy and lower extremity ultrasonography were unremarkable. Punch biopsies were performed of the left lateral leg and posterior calf. Hematoxylin and eosin staining demonstrated marked mucin deposition extending to the deep dermis along with deep fibroplasia and was read as consistent with PTM. Colloidal iron highlighted prominent mucin within the dermis (Figure 2).

The patient’s medical history, physical examination, laboratory analysis, imaging, and biopsies were considered, and a diagnosis of elephantiasic PTM was made. Minimal improvement was noted with initial therapeutic interventions including compression therapy and application of super high–potency topical corticosteroids. After further evaluation in our multidisciplinary rheumatology-dermatology clinic, the decision was made to initiate rituximab infusions.

Two months after 1 course of rituximab consisting of two 1000-mg infusions separated by 2 weeks, the patient showed substantial clinical improvement. There was striking improvement of the pretibial surfaces with resolution of the exophytic nodules and improvement of the induration (Figure 3). In addition, there was decreased induration of the glabella and earlobes and decreased fullness of the digital pulp on the hands. The patient also reported subjective improvements in mobility.

Our patient demonstrated all 3 aspects of the Diamond triad: PTM, exophthalmos, and acropachy. Patients present with all 3 features in less than 1% of reported cases of Graves disease.3 Although all 3 features are seen together infrequently, thyroid dermopathy and acropachy often are markers of severe Graves ophthalmopathy. In a study of 114 patients with Graves ophthalmopathy, patients who also had dermopathy and acropachy were more likely to have optic neuropathy or require orbital decompression.4

After overcoming the diagnostic dilemma that the elephantiasic presentation of PTM can present, therapeutic management remains a challenge. Heyes et al5 documented the successful treatment of highly recalcitrant elephantiasic PTM with rituximab and plasmapheresis therapy. In this case, a 44-year-old woman with an 11-year history of Graves disease and elephantiasic PTM received 29 rituximab infusions and 241 plasmapheresis treatments over the course of 3.5 years. Her elephantiasic PTM clinically resolved, and she was able to resume daily activities and wear normal shoes after being nonambulatory for years.5

Rituximab is a monoclonal antibody against CD20, a protein found primarily on the surface of B-cell lymphocytes. Although rituximab initially was approved by the US Food and Drug administration for the treatment of malignant lymphoma, it has had an increasing role in the treatment of autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis. Rituximab is postulated to target B lymphocytes and halt their progression to plasma cells. By limiting the population of long-lasting, antibody-producing plasma cells and decreasing the autoantibodies that cause many of the symptoms in Graves disease, rituximab may be an effective therapy to consider in the treatment of elephantiasic PTM.6

Although the exact mechanism is poorly understood, PTM likely is a sequela of hyperthyroidism because of the expression of thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor proteins found on normal dermal fibroblasts. Thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor autoantibodies are thought to stimulate these fibroblasts to produce glycosaminoglycans. Histopathologically, accumulation of glycosaminoglycans deposited in the reticular dermis with high concentrations of hyaluronic acid is observed in PTM.7

Treatment of elephantiasic PTM remains a therapeutic challenge. Given the rarity of the disease process and limited information on effective therapeutic modalities, rituximab should be viewed as a viable treatment option in the management of recalcitrant elephantiasic PTM.

- Schwartz KM, Fatourechi V, Ahmed DDF, et al. Dermopathy of Graves’ disease (pretibial myxedema): long-term outcome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:438-446.

- Kakati S, Doley B, Pal S, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: a rare thyroid dermopathy in Graves’ disease. J Assoc Physicians India. 2005;53:571-572.

- Anderson CK, Miller OF 3rd. Triad of exophthalmos, pretibial myxedema, and acropachy in a patient with Graves’ disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:970-972.

- Fatourechi V, Bartley GB, Eghbali-Fatourechi GZ, et al. Graves’ dermopathy and acropachy are markers of severe Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Thyroid. 2003;13:1141-1144.

- Heyes C, Nolan R, Leahy M, et al. Treatment‐resistant elephantiasic thyroid dermopathy responding to rituximab and plasmapheresis. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:E1-E4.

- Salvi M, Vannucchi G, Campi I, et al. Treatment of Graves’ disease and associated ophthalmopathy with the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab: an open study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2007;156:33-40.

- Heufelder AE, Dutton CM, Sarkar G, et al. Detection of TSH receptor RNA in cultured fibroblasts from patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy and pretibial dermopathy. Thyroid. 1993;3:297-300.

To the Editor:

Pretibial myxedema (PTM) is bilateral, nonpitting, scaly thickening and induration of the skin that most commonly occurs on the anterior aspects of the legs and feet. Pretibial myxedema occurs in approximately 0.5% to 4.3% of patients with hyperthyroidism.1 Thyroid dermopathy often is thought of as the classic nonpitting PTM with skin induration and color change. However, rarer forms of PTM, including plaque, nodular, and elephantiasic, also are important to note.2

Elephantiasic PTM is extremely rare, occurring in less than 1% of patients with PTM.2 Elephantiasic PTM is characterized by the persistent swelling of 1 or both legs; thickening of the skin overlying the dorsum of the feet, ankles, and toes; and verrucous irregular plaques that often are fleshy and flattened. The clinical differential diagnosis of elephantiasic PTM includes elephantiasis nostra verrucosa, a late-stage complication of chronic lymphedema that can be related to a variety of infectious or noninfectious obstructive processes. Few effective therapeutic modalities exist in the treatment of elephantiasic PTM. We present a case of elephantiasic PTM.

A 59-year-old man presented to dermatology with leonine facies with pronounced glabellar creases and indentations of the earlobes. He had diffuse woody induration, hyperpigmentation, and nonpitting edema of the lower extremities as well as several flesh-colored exophytic nodules scattered throughout the anterior shins and dorsal feet (Figure 1). On the left posterior calf, there was a large, 3-cm, exophytic, firm, flesh-colored nodule. Examination of the hands revealed mild hyperpigmentation of the distal digits, clubbing of the distal phalanges, and cheiroarthropathy.

The patient was diagnosed with Graves disease after experiencing the classic symptoms of hyperthyroidism, including heat intolerance, tremor, palpitations, and anxiety. He received thyroid ablation and subsequently was supplemented with levothyroxine 75 mg daily. Twelve years later, he was diagnosed with Graves ophthalmopathy with ocular proptosis requiring multiple courses of retro-orbital irradiation and surgical procedures for decompression. Approximately 1 year later, he noted increased swelling, firmness, and darkening of the pretibial surfaces. Initially, he was referred to vascular surgery and underwent bilateral saphenous vein ablation. He also was referred to a lymphedema specialist, and workup revealed an unremarkable lymphatic system. Minimal improvement was noted following the saphenous vein ablation, and he subsequently was referred to dermatology for further workup.

At the current presentation, laboratory analysis revealed a low thyrotropin level (0.03 mIU/L [reference range, 0.4–4.2 mIU/L]), and free thyroxine was within reference range. Radiography of the chest was unremarkable; however, radiography of the hand demonstrated arthrosis of the left fifth proximal interphalangeal joint. Nuclear medicine lymphoscintigraphy and lower extremity ultrasonography were unremarkable. Punch biopsies were performed of the left lateral leg and posterior calf. Hematoxylin and eosin staining demonstrated marked mucin deposition extending to the deep dermis along with deep fibroplasia and was read as consistent with PTM. Colloidal iron highlighted prominent mucin within the dermis (Figure 2).

The patient’s medical history, physical examination, laboratory analysis, imaging, and biopsies were considered, and a diagnosis of elephantiasic PTM was made. Minimal improvement was noted with initial therapeutic interventions including compression therapy and application of super high–potency topical corticosteroids. After further evaluation in our multidisciplinary rheumatology-dermatology clinic, the decision was made to initiate rituximab infusions.

Two months after 1 course of rituximab consisting of two 1000-mg infusions separated by 2 weeks, the patient showed substantial clinical improvement. There was striking improvement of the pretibial surfaces with resolution of the exophytic nodules and improvement of the induration (Figure 3). In addition, there was decreased induration of the glabella and earlobes and decreased fullness of the digital pulp on the hands. The patient also reported subjective improvements in mobility.

Our patient demonstrated all 3 aspects of the Diamond triad: PTM, exophthalmos, and acropachy. Patients present with all 3 features in less than 1% of reported cases of Graves disease.3 Although all 3 features are seen together infrequently, thyroid dermopathy and acropachy often are markers of severe Graves ophthalmopathy. In a study of 114 patients with Graves ophthalmopathy, patients who also had dermopathy and acropachy were more likely to have optic neuropathy or require orbital decompression.4

After overcoming the diagnostic dilemma that the elephantiasic presentation of PTM can present, therapeutic management remains a challenge. Heyes et al5 documented the successful treatment of highly recalcitrant elephantiasic PTM with rituximab and plasmapheresis therapy. In this case, a 44-year-old woman with an 11-year history of Graves disease and elephantiasic PTM received 29 rituximab infusions and 241 plasmapheresis treatments over the course of 3.5 years. Her elephantiasic PTM clinically resolved, and she was able to resume daily activities and wear normal shoes after being nonambulatory for years.5

Rituximab is a monoclonal antibody against CD20, a protein found primarily on the surface of B-cell lymphocytes. Although rituximab initially was approved by the US Food and Drug administration for the treatment of malignant lymphoma, it has had an increasing role in the treatment of autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis. Rituximab is postulated to target B lymphocytes and halt their progression to plasma cells. By limiting the population of long-lasting, antibody-producing plasma cells and decreasing the autoantibodies that cause many of the symptoms in Graves disease, rituximab may be an effective therapy to consider in the treatment of elephantiasic PTM.6

Although the exact mechanism is poorly understood, PTM likely is a sequela of hyperthyroidism because of the expression of thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor proteins found on normal dermal fibroblasts. Thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor autoantibodies are thought to stimulate these fibroblasts to produce glycosaminoglycans. Histopathologically, accumulation of glycosaminoglycans deposited in the reticular dermis with high concentrations of hyaluronic acid is observed in PTM.7

Treatment of elephantiasic PTM remains a therapeutic challenge. Given the rarity of the disease process and limited information on effective therapeutic modalities, rituximab should be viewed as a viable treatment option in the management of recalcitrant elephantiasic PTM.

To the Editor:

Pretibial myxedema (PTM) is bilateral, nonpitting, scaly thickening and induration of the skin that most commonly occurs on the anterior aspects of the legs and feet. Pretibial myxedema occurs in approximately 0.5% to 4.3% of patients with hyperthyroidism.1 Thyroid dermopathy often is thought of as the classic nonpitting PTM with skin induration and color change. However, rarer forms of PTM, including plaque, nodular, and elephantiasic, also are important to note.2

Elephantiasic PTM is extremely rare, occurring in less than 1% of patients with PTM.2 Elephantiasic PTM is characterized by the persistent swelling of 1 or both legs; thickening of the skin overlying the dorsum of the feet, ankles, and toes; and verrucous irregular plaques that often are fleshy and flattened. The clinical differential diagnosis of elephantiasic PTM includes elephantiasis nostra verrucosa, a late-stage complication of chronic lymphedema that can be related to a variety of infectious or noninfectious obstructive processes. Few effective therapeutic modalities exist in the treatment of elephantiasic PTM. We present a case of elephantiasic PTM.

A 59-year-old man presented to dermatology with leonine facies with pronounced glabellar creases and indentations of the earlobes. He had diffuse woody induration, hyperpigmentation, and nonpitting edema of the lower extremities as well as several flesh-colored exophytic nodules scattered throughout the anterior shins and dorsal feet (Figure 1). On the left posterior calf, there was a large, 3-cm, exophytic, firm, flesh-colored nodule. Examination of the hands revealed mild hyperpigmentation of the distal digits, clubbing of the distal phalanges, and cheiroarthropathy.

The patient was diagnosed with Graves disease after experiencing the classic symptoms of hyperthyroidism, including heat intolerance, tremor, palpitations, and anxiety. He received thyroid ablation and subsequently was supplemented with levothyroxine 75 mg daily. Twelve years later, he was diagnosed with Graves ophthalmopathy with ocular proptosis requiring multiple courses of retro-orbital irradiation and surgical procedures for decompression. Approximately 1 year later, he noted increased swelling, firmness, and darkening of the pretibial surfaces. Initially, he was referred to vascular surgery and underwent bilateral saphenous vein ablation. He also was referred to a lymphedema specialist, and workup revealed an unremarkable lymphatic system. Minimal improvement was noted following the saphenous vein ablation, and he subsequently was referred to dermatology for further workup.

At the current presentation, laboratory analysis revealed a low thyrotropin level (0.03 mIU/L [reference range, 0.4–4.2 mIU/L]), and free thyroxine was within reference range. Radiography of the chest was unremarkable; however, radiography of the hand demonstrated arthrosis of the left fifth proximal interphalangeal joint. Nuclear medicine lymphoscintigraphy and lower extremity ultrasonography were unremarkable. Punch biopsies were performed of the left lateral leg and posterior calf. Hematoxylin and eosin staining demonstrated marked mucin deposition extending to the deep dermis along with deep fibroplasia and was read as consistent with PTM. Colloidal iron highlighted prominent mucin within the dermis (Figure 2).

The patient’s medical history, physical examination, laboratory analysis, imaging, and biopsies were considered, and a diagnosis of elephantiasic PTM was made. Minimal improvement was noted with initial therapeutic interventions including compression therapy and application of super high–potency topical corticosteroids. After further evaluation in our multidisciplinary rheumatology-dermatology clinic, the decision was made to initiate rituximab infusions.

Two months after 1 course of rituximab consisting of two 1000-mg infusions separated by 2 weeks, the patient showed substantial clinical improvement. There was striking improvement of the pretibial surfaces with resolution of the exophytic nodules and improvement of the induration (Figure 3). In addition, there was decreased induration of the glabella and earlobes and decreased fullness of the digital pulp on the hands. The patient also reported subjective improvements in mobility.

Our patient demonstrated all 3 aspects of the Diamond triad: PTM, exophthalmos, and acropachy. Patients present with all 3 features in less than 1% of reported cases of Graves disease.3 Although all 3 features are seen together infrequently, thyroid dermopathy and acropachy often are markers of severe Graves ophthalmopathy. In a study of 114 patients with Graves ophthalmopathy, patients who also had dermopathy and acropachy were more likely to have optic neuropathy or require orbital decompression.4

After overcoming the diagnostic dilemma that the elephantiasic presentation of PTM can present, therapeutic management remains a challenge. Heyes et al5 documented the successful treatment of highly recalcitrant elephantiasic PTM with rituximab and plasmapheresis therapy. In this case, a 44-year-old woman with an 11-year history of Graves disease and elephantiasic PTM received 29 rituximab infusions and 241 plasmapheresis treatments over the course of 3.5 years. Her elephantiasic PTM clinically resolved, and she was able to resume daily activities and wear normal shoes after being nonambulatory for years.5

Rituximab is a monoclonal antibody against CD20, a protein found primarily on the surface of B-cell lymphocytes. Although rituximab initially was approved by the US Food and Drug administration for the treatment of malignant lymphoma, it has had an increasing role in the treatment of autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis. Rituximab is postulated to target B lymphocytes and halt their progression to plasma cells. By limiting the population of long-lasting, antibody-producing plasma cells and decreasing the autoantibodies that cause many of the symptoms in Graves disease, rituximab may be an effective therapy to consider in the treatment of elephantiasic PTM.6

Although the exact mechanism is poorly understood, PTM likely is a sequela of hyperthyroidism because of the expression of thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor proteins found on normal dermal fibroblasts. Thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor autoantibodies are thought to stimulate these fibroblasts to produce glycosaminoglycans. Histopathologically, accumulation of glycosaminoglycans deposited in the reticular dermis with high concentrations of hyaluronic acid is observed in PTM.7

Treatment of elephantiasic PTM remains a therapeutic challenge. Given the rarity of the disease process and limited information on effective therapeutic modalities, rituximab should be viewed as a viable treatment option in the management of recalcitrant elephantiasic PTM.

- Schwartz KM, Fatourechi V, Ahmed DDF, et al. Dermopathy of Graves’ disease (pretibial myxedema): long-term outcome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:438-446.

- Kakati S, Doley B, Pal S, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: a rare thyroid dermopathy in Graves’ disease. J Assoc Physicians India. 2005;53:571-572.

- Anderson CK, Miller OF 3rd. Triad of exophthalmos, pretibial myxedema, and acropachy in a patient with Graves’ disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:970-972.

- Fatourechi V, Bartley GB, Eghbali-Fatourechi GZ, et al. Graves’ dermopathy and acropachy are markers of severe Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Thyroid. 2003;13:1141-1144.

- Heyes C, Nolan R, Leahy M, et al. Treatment‐resistant elephantiasic thyroid dermopathy responding to rituximab and plasmapheresis. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:E1-E4.

- Salvi M, Vannucchi G, Campi I, et al. Treatment of Graves’ disease and associated ophthalmopathy with the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab: an open study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2007;156:33-40.

- Heufelder AE, Dutton CM, Sarkar G, et al. Detection of TSH receptor RNA in cultured fibroblasts from patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy and pretibial dermopathy. Thyroid. 1993;3:297-300.

- Schwartz KM, Fatourechi V, Ahmed DDF, et al. Dermopathy of Graves’ disease (pretibial myxedema): long-term outcome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:438-446.

- Kakati S, Doley B, Pal S, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: a rare thyroid dermopathy in Graves’ disease. J Assoc Physicians India. 2005;53:571-572.

- Anderson CK, Miller OF 3rd. Triad of exophthalmos, pretibial myxedema, and acropachy in a patient with Graves’ disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:970-972.

- Fatourechi V, Bartley GB, Eghbali-Fatourechi GZ, et al. Graves’ dermopathy and acropachy are markers of severe Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Thyroid. 2003;13:1141-1144.

- Heyes C, Nolan R, Leahy M, et al. Treatment‐resistant elephantiasic thyroid dermopathy responding to rituximab and plasmapheresis. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:E1-E4.

- Salvi M, Vannucchi G, Campi I, et al. Treatment of Graves’ disease and associated ophthalmopathy with the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab: an open study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2007;156:33-40.

- Heufelder AE, Dutton CM, Sarkar G, et al. Detection of TSH receptor RNA in cultured fibroblasts from patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy and pretibial dermopathy. Thyroid. 1993;3:297-300.

Practice Points

- Pretibial myxedema (PTM) is bilateral, nonpitting, scaly thickening and induration of the skin that most commonly occurs on the anterior aspects of the legs and feet.

- Although many therapeutic modalities have been described for the management of the elephantiasis variant of PTM, few treatments have shown notable efficacy.

- Rituximab may be an effective therapy to consider in the treatment of elephantiasic PTM.

Headache and Covid-19: What clinicians should know

Edoardo Caronna, MD and Patricia Pozo-Rosich, MD, PhD, Neurology Department, Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron, Department of Medicine, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain; and Headache and Neurological Pain Research Group, Vall d’Hebron Research Institute, Department of Medicine, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain. Dr. Pozo-Rosich also serves on the boards of the International Headache Society and Council of the European Headache Federation and is an editor for various peer-reviewed journals, including Cephalalgia and Headache.

Headache is a symptom of the coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19), caused by the novel, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Since the pandemic began, researchers have tried to describe, understand, and help clinicians manage headache in the setting of Covid-19.

The reason is simple: Headache is common, often debilitating, and difficult to treat.1

Moreover, headache could manifest both in the acute phase of the infection and, once the infection has resolved, in the post-acute phase.1 Therefore, it is critical for clinicians to know more about headache, as headache can be a common reason that patients seek help, both in the specialized and non-specialized medical care setting.

Definitions and manifestations

While the first step in such a communication would be to define headache attributed to Covid-19, no specific definition exists, as this is a new disease. Therefore, headache attributed to Covid-19 should be defined under the diagnostic criteria, as contained in the International Classification of Headache Disorders-3, as headache attributed to a systemic viral infection.2 As this is a secondary headache appearing with an infection, the treating physician needs to rule out possible underlying meningitis and/or encephalitis in the diagnosis. Moreover, other secondary headaches (eg, cerebral venous thrombosis) may appear, so clinicians need to carefully evaluate patients with headache during Covid-19 to detect signs or symptoms that point to other etiologies.

It is also advisable to know the clinical manifestations of headache attributed to Covid-19. Studies published so far have observed two main phenotypes of headache in the acute phase of the infection: one resembles migraine, the other, a tension-type headache.1,3 Although patients with history of migraine who contract Covid-19 report headache that is more similar to primary headache disorder,4 two relevant aspects should be considered. Namely, migraine-like features can be observed in patients without personal migraine history; and Covid-19 patients with such history may perceive that headache they experience in the infection’s acute phase differs from their usual experience, especially regarding increased severity or duration.5,6 Of note, headache can be a prodromal symptom of the SARS-CoV-2 infection.1

Evolution of a headache

Because headache appearing after the acute phase of the infection can persist, often manifesting migraine-like features, it is inordinately helpful for clinicians to know its evolution.1 This persistent headache, sometimes referred to as post-covid headache, is not aptly named because the post-covid headache is not just one type of headache, but instead can manifest as different headache types.

A recently published case series in Headache discussed three Covid patients who all experienced persistent headache during the infection’s post-acute phase.7 These patients experienced a migraine-like phenotype as have others with mild Covid-19, but their personal history of migraine, as well as their experience with Covid-19 related headache, were substantially different. Some patients had personal migraine history while others did not; some patients experienced no headache in the acute phase but did so in the post-acute phase; and the concomitant symptoms of the post-acute phase, such as insomnia, memory loss, dizziness, fatigue, and brain fog, were differentially expressed by patients.7

This case series introduces the concept that patients with no prior history of migraine or any other primary headache disorder can develop a de novo headache because of their SARS-CoV-2 infection. Moreover, it could manifest as a new daily persistent headache. And patients with personal history of migraine may experience sudden chronification in their headache’s characteristics, rather than develop a new type of headache.7

In another study, soon to be published in Cephalalgia, researchers observed that the median duration of headache in the acute phase is 2 weeks. This multicenter Spanish study, in which data on headache duration were available for 874 patients, found that 16% of these particular patients had persistent headache after 9 months. According to this study, headache that does not resolve within the first 3 months is less likely to do so later on.

Treatment

For clinicians, the significance of these findings is straightforward: Patients with headache experienced in the infection’s acute phase that does not seem to resolve post-infection requires continued medical attention. Patients should be monitored, carefully managed, and treated to avoid the onset of a persisting headache. This applies to patients with or without personal migraine history.

But which treatments should be prescribed? As there are no specific therapies for headache attributed to Covid-19, either in the acute or post-acute phase of the infection, clinicians must turn to existing therapies.

As with patients with migraine, patients with persistent headache post-Covid infection need a headache prevention strategy.

The strategy should be based on the following principles:

- treat headache

- treat comorbidities including mood disorders, insomnia, and so on

- avoid complications such as medication overuse, which may be very common in these patients.

Acute medications

Despite the lack of specific literature on this matter, migraine-like phenotypes may respond to triptans and probably, where available, lasmiditan and gepants. These medications probably represent a therapeutic option for Covid patients with headache, but before prescribing them clinicians should carefully evaluate their use.

Before deciding on the prescription, clinicians should consider not only the medications’ most common contraindications, but also those that are related to Covid-19: the phase of the infection (acute/post-acute); the infection’s severity; and the presence of other Covid-related health problems. The concerns over the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) and corticosteroids, raised when the pandemic first struck, have greatly dissipated.8,9 Some patients with prolonged headache may benefit from a brief cycle of corticosteroids, similar to the treatment given to those patients with status migrainosus. Nerve blocks could also be considered.

Preventive medications

Drugs can be prescribed according to the headache phenotype too, but there are no published studies that specifically evaluate headache prevention treatments in patients with persistent headache post-infection. The case series mentioned earlier in this article recorded that patients whose headaches were treated with amitriptyline and onabotulinumtoxinA had reported variable treatment responses to this regimen, according to the patients’ characteristics.7

However, one important question regarding the safety of Covid patients with migraine – specifically patients on preventive treatments during the infection’s acute phase – has been somewhat resolved.

Medications such as renin-angiotensin system (RAS) blockers, suspected of possible involvement in the SARs-CoV-2 pathogenicity, seem to be safe.8,10 And, in another multicenter Spanish study, researchers found that the use of anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies did not seem to be associated with worse Covid-19 outcomes despite the possible implication of CGRP in modulating inflammatory responses during a viral infection.11

The study of anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies could be important in the future for another reason: To see whether these medications could be effective as a preventive treatment in patients with persistent headache after Covid-19, regardless of whether these patients have personal migraine history.

An interesting and important message to close this article. Although headache experienced in the infection’s acute phase could be extremely disabling for patients, the evidence points to the presence of headache as a marker of a better Covid-19 prognosis, in terms of a shorter infection period and a lower risk of mortality among hospitalized patients.1,3,12

This brief communication contains current information to help clinicians treat and inform their patients with Covid-sourced headache. Yet, we must keep in mind that the majority of the data reported here and published in the literature refer to studies conducted during the first wave of the pandemic. The emergence of new SARS-CoV-2 variants and vaccines have enormously changed the disease’s clinical presentation and course, so future studies are warranted to re-assess the validity of these findings under new conditions.

References

1. Caronna E, Ballvé A, Llauradó A, Gallardo VJ, et al. Headache: A striking prodromal and persistent symptom, predictive of COVID-19 clinical evolution. Cephalalgia. 2020; Nov;40(13):1410-1421.

2. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018; Jan;38(1):1-211.

3. Trigo J, García-Azorín D, Planchuelo-Gómez Á, et al. Factors associated with the presence of headache in hospitalized COVID-19 patients and impact on prognosis: A retrospective cohort study. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):94. https://thejournalofheadacheandpain.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s10194-020-01165-8

4. Porta-Etessam J, Matías-Guiu JA, González-García N, et al. Spectrum of Headaches Associated With SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Study of Healthcare Professionals. Headache. 2020;60(8):1697–1704.

5. Singh J, Ali A. Headache as the Presenting Symptom in 2 Patients With COVID-19 and a History of Migraine: 2 Case Reports. Headache. 2020;60(8):1773–1776.

6. Membrilla JA, de Lorenzo Í, Sastre M, Díaz de Terán J. Headache as a Cardinal Symptom of Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Cross-Sectional Study. Headache. 2020; Nov;60(10):2176-2191.

7. Caronna E, Alpuente A, Torres-Ferrus M, Pozo-Rosich P. Toward a better understanding of persistent headache after mild COVID-19: Three migraine-like yet distinct scenarios. Headache. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.14197

8. Maassenvandenbrink A, De Vries T, Danser AHJ. Headache medication and the COVID-19 pandemic. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1). https://thejournalofheadacheandpain.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s10194-020-01106-5

9. Arca KN, Smith JH, Chiang CC, et al. COVID-19 and Headache Medicine: A Narrative Review of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug (NSAID) and Corticosteroid Use. Headache. 2020; Sep;60(8): 1558–1568.

10. Hippisley-Cox J, Young D, Coupland C, et al. Risk of severe COVID-19 disease with ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers: Cohort study including 8.3 million people. Heart. 2020;Oct;106(19):1503-1511.

11. Caronna E, José Gallardo V, Alpuente A, Torres-Ferrus M, Sánchez-Mateo NM, Viguera-Romero J, et al. Safety of anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies in patients with migraine during the COVID-19 pandemic: Present and future implications. Neurologia. 2021; Mar 19;36(8):611-617.

12. Gonzalez-Martinez A, Fanjul V, Ramos C, Serrano Ballesteros J, et al. Headache during SARS-CoV-2 infection as an early symptom associated with a more benign course of disease: a case–control study. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28(10):3426–36.

Edoardo Caronna, MD and Patricia Pozo-Rosich, MD, PhD, Neurology Department, Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron, Department of Medicine, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain; and Headache and Neurological Pain Research Group, Vall d’Hebron Research Institute, Department of Medicine, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain. Dr. Pozo-Rosich also serves on the boards of the International Headache Society and Council of the European Headache Federation and is an editor for various peer-reviewed journals, including Cephalalgia and Headache.

Headache is a symptom of the coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19), caused by the novel, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Since the pandemic began, researchers have tried to describe, understand, and help clinicians manage headache in the setting of Covid-19.

The reason is simple: Headache is common, often debilitating, and difficult to treat.1

Moreover, headache could manifest both in the acute phase of the infection and, once the infection has resolved, in the post-acute phase.1 Therefore, it is critical for clinicians to know more about headache, as headache can be a common reason that patients seek help, both in the specialized and non-specialized medical care setting.

Definitions and manifestations

While the first step in such a communication would be to define headache attributed to Covid-19, no specific definition exists, as this is a new disease. Therefore, headache attributed to Covid-19 should be defined under the diagnostic criteria, as contained in the International Classification of Headache Disorders-3, as headache attributed to a systemic viral infection.2 As this is a secondary headache appearing with an infection, the treating physician needs to rule out possible underlying meningitis and/or encephalitis in the diagnosis. Moreover, other secondary headaches (eg, cerebral venous thrombosis) may appear, so clinicians need to carefully evaluate patients with headache during Covid-19 to detect signs or symptoms that point to other etiologies.

It is also advisable to know the clinical manifestations of headache attributed to Covid-19. Studies published so far have observed two main phenotypes of headache in the acute phase of the infection: one resembles migraine, the other, a tension-type headache.1,3 Although patients with history of migraine who contract Covid-19 report headache that is more similar to primary headache disorder,4 two relevant aspects should be considered. Namely, migraine-like features can be observed in patients without personal migraine history; and Covid-19 patients with such history may perceive that headache they experience in the infection’s acute phase differs from their usual experience, especially regarding increased severity or duration.5,6 Of note, headache can be a prodromal symptom of the SARS-CoV-2 infection.1

Evolution of a headache

Because headache appearing after the acute phase of the infection can persist, often manifesting migraine-like features, it is inordinately helpful for clinicians to know its evolution.1 This persistent headache, sometimes referred to as post-covid headache, is not aptly named because the post-covid headache is not just one type of headache, but instead can manifest as different headache types.

A recently published case series in Headache discussed three Covid patients who all experienced persistent headache during the infection’s post-acute phase.7 These patients experienced a migraine-like phenotype as have others with mild Covid-19, but their personal history of migraine, as well as their experience with Covid-19 related headache, were substantially different. Some patients had personal migraine history while others did not; some patients experienced no headache in the acute phase but did so in the post-acute phase; and the concomitant symptoms of the post-acute phase, such as insomnia, memory loss, dizziness, fatigue, and brain fog, were differentially expressed by patients.7

This case series introduces the concept that patients with no prior history of migraine or any other primary headache disorder can develop a de novo headache because of their SARS-CoV-2 infection. Moreover, it could manifest as a new daily persistent headache. And patients with personal history of migraine may experience sudden chronification in their headache’s characteristics, rather than develop a new type of headache.7

In another study, soon to be published in Cephalalgia, researchers observed that the median duration of headache in the acute phase is 2 weeks. This multicenter Spanish study, in which data on headache duration were available for 874 patients, found that 16% of these particular patients had persistent headache after 9 months. According to this study, headache that does not resolve within the first 3 months is less likely to do so later on.

Treatment

For clinicians, the significance of these findings is straightforward: Patients with headache experienced in the infection’s acute phase that does not seem to resolve post-infection requires continued medical attention. Patients should be monitored, carefully managed, and treated to avoid the onset of a persisting headache. This applies to patients with or without personal migraine history.

But which treatments should be prescribed? As there are no specific therapies for headache attributed to Covid-19, either in the acute or post-acute phase of the infection, clinicians must turn to existing therapies.

As with patients with migraine, patients with persistent headache post-Covid infection need a headache prevention strategy.

The strategy should be based on the following principles:

- treat headache

- treat comorbidities including mood disorders, insomnia, and so on

- avoid complications such as medication overuse, which may be very common in these patients.

Acute medications

Despite the lack of specific literature on this matter, migraine-like phenotypes may respond to triptans and probably, where available, lasmiditan and gepants. These medications probably represent a therapeutic option for Covid patients with headache, but before prescribing them clinicians should carefully evaluate their use.

Before deciding on the prescription, clinicians should consider not only the medications’ most common contraindications, but also those that are related to Covid-19: the phase of the infection (acute/post-acute); the infection’s severity; and the presence of other Covid-related health problems. The concerns over the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) and corticosteroids, raised when the pandemic first struck, have greatly dissipated.8,9 Some patients with prolonged headache may benefit from a brief cycle of corticosteroids, similar to the treatment given to those patients with status migrainosus. Nerve blocks could also be considered.

Preventive medications

Drugs can be prescribed according to the headache phenotype too, but there are no published studies that specifically evaluate headache prevention treatments in patients with persistent headache post-infection. The case series mentioned earlier in this article recorded that patients whose headaches were treated with amitriptyline and onabotulinumtoxinA had reported variable treatment responses to this regimen, according to the patients’ characteristics.7

However, one important question regarding the safety of Covid patients with migraine – specifically patients on preventive treatments during the infection’s acute phase – has been somewhat resolved.

Medications such as renin-angiotensin system (RAS) blockers, suspected of possible involvement in the SARs-CoV-2 pathogenicity, seem to be safe.8,10 And, in another multicenter Spanish study, researchers found that the use of anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies did not seem to be associated with worse Covid-19 outcomes despite the possible implication of CGRP in modulating inflammatory responses during a viral infection.11

The study of anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies could be important in the future for another reason: To see whether these medications could be effective as a preventive treatment in patients with persistent headache after Covid-19, regardless of whether these patients have personal migraine history.

An interesting and important message to close this article. Although headache experienced in the infection’s acute phase could be extremely disabling for patients, the evidence points to the presence of headache as a marker of a better Covid-19 prognosis, in terms of a shorter infection period and a lower risk of mortality among hospitalized patients.1,3,12

This brief communication contains current information to help clinicians treat and inform their patients with Covid-sourced headache. Yet, we must keep in mind that the majority of the data reported here and published in the literature refer to studies conducted during the first wave of the pandemic. The emergence of new SARS-CoV-2 variants and vaccines have enormously changed the disease’s clinical presentation and course, so future studies are warranted to re-assess the validity of these findings under new conditions.

Edoardo Caronna, MD and Patricia Pozo-Rosich, MD, PhD, Neurology Department, Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron, Department of Medicine, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain; and Headache and Neurological Pain Research Group, Vall d’Hebron Research Institute, Department of Medicine, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain. Dr. Pozo-Rosich also serves on the boards of the International Headache Society and Council of the European Headache Federation and is an editor for various peer-reviewed journals, including Cephalalgia and Headache.

Headache is a symptom of the coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19), caused by the novel, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Since the pandemic began, researchers have tried to describe, understand, and help clinicians manage headache in the setting of Covid-19.

The reason is simple: Headache is common, often debilitating, and difficult to treat.1

Moreover, headache could manifest both in the acute phase of the infection and, once the infection has resolved, in the post-acute phase.1 Therefore, it is critical for clinicians to know more about headache, as headache can be a common reason that patients seek help, both in the specialized and non-specialized medical care setting.

Definitions and manifestations

While the first step in such a communication would be to define headache attributed to Covid-19, no specific definition exists, as this is a new disease. Therefore, headache attributed to Covid-19 should be defined under the diagnostic criteria, as contained in the International Classification of Headache Disorders-3, as headache attributed to a systemic viral infection.2 As this is a secondary headache appearing with an infection, the treating physician needs to rule out possible underlying meningitis and/or encephalitis in the diagnosis. Moreover, other secondary headaches (eg, cerebral venous thrombosis) may appear, so clinicians need to carefully evaluate patients with headache during Covid-19 to detect signs or symptoms that point to other etiologies.

It is also advisable to know the clinical manifestations of headache attributed to Covid-19. Studies published so far have observed two main phenotypes of headache in the acute phase of the infection: one resembles migraine, the other, a tension-type headache.1,3 Although patients with history of migraine who contract Covid-19 report headache that is more similar to primary headache disorder,4 two relevant aspects should be considered. Namely, migraine-like features can be observed in patients without personal migraine history; and Covid-19 patients with such history may perceive that headache they experience in the infection’s acute phase differs from their usual experience, especially regarding increased severity or duration.5,6 Of note, headache can be a prodromal symptom of the SARS-CoV-2 infection.1

Evolution of a headache

Because headache appearing after the acute phase of the infection can persist, often manifesting migraine-like features, it is inordinately helpful for clinicians to know its evolution.1 This persistent headache, sometimes referred to as post-covid headache, is not aptly named because the post-covid headache is not just one type of headache, but instead can manifest as different headache types.

A recently published case series in Headache discussed three Covid patients who all experienced persistent headache during the infection’s post-acute phase.7 These patients experienced a migraine-like phenotype as have others with mild Covid-19, but their personal history of migraine, as well as their experience with Covid-19 related headache, were substantially different. Some patients had personal migraine history while others did not; some patients experienced no headache in the acute phase but did so in the post-acute phase; and the concomitant symptoms of the post-acute phase, such as insomnia, memory loss, dizziness, fatigue, and brain fog, were differentially expressed by patients.7

This case series introduces the concept that patients with no prior history of migraine or any other primary headache disorder can develop a de novo headache because of their SARS-CoV-2 infection. Moreover, it could manifest as a new daily persistent headache. And patients with personal history of migraine may experience sudden chronification in their headache’s characteristics, rather than develop a new type of headache.7

In another study, soon to be published in Cephalalgia, researchers observed that the median duration of headache in the acute phase is 2 weeks. This multicenter Spanish study, in which data on headache duration were available for 874 patients, found that 16% of these particular patients had persistent headache after 9 months. According to this study, headache that does not resolve within the first 3 months is less likely to do so later on.

Treatment

For clinicians, the significance of these findings is straightforward: Patients with headache experienced in the infection’s acute phase that does not seem to resolve post-infection requires continued medical attention. Patients should be monitored, carefully managed, and treated to avoid the onset of a persisting headache. This applies to patients with or without personal migraine history.

But which treatments should be prescribed? As there are no specific therapies for headache attributed to Covid-19, either in the acute or post-acute phase of the infection, clinicians must turn to existing therapies.

As with patients with migraine, patients with persistent headache post-Covid infection need a headache prevention strategy.

The strategy should be based on the following principles:

- treat headache

- treat comorbidities including mood disorders, insomnia, and so on

- avoid complications such as medication overuse, which may be very common in these patients.

Acute medications

Despite the lack of specific literature on this matter, migraine-like phenotypes may respond to triptans and probably, where available, lasmiditan and gepants. These medications probably represent a therapeutic option for Covid patients with headache, but before prescribing them clinicians should carefully evaluate their use.

Before deciding on the prescription, clinicians should consider not only the medications’ most common contraindications, but also those that are related to Covid-19: the phase of the infection (acute/post-acute); the infection’s severity; and the presence of other Covid-related health problems. The concerns over the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) and corticosteroids, raised when the pandemic first struck, have greatly dissipated.8,9 Some patients with prolonged headache may benefit from a brief cycle of corticosteroids, similar to the treatment given to those patients with status migrainosus. Nerve blocks could also be considered.

Preventive medications

Drugs can be prescribed according to the headache phenotype too, but there are no published studies that specifically evaluate headache prevention treatments in patients with persistent headache post-infection. The case series mentioned earlier in this article recorded that patients whose headaches were treated with amitriptyline and onabotulinumtoxinA had reported variable treatment responses to this regimen, according to the patients’ characteristics.7

However, one important question regarding the safety of Covid patients with migraine – specifically patients on preventive treatments during the infection’s acute phase – has been somewhat resolved.

Medications such as renin-angiotensin system (RAS) blockers, suspected of possible involvement in the SARs-CoV-2 pathogenicity, seem to be safe.8,10 And, in another multicenter Spanish study, researchers found that the use of anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies did not seem to be associated with worse Covid-19 outcomes despite the possible implication of CGRP in modulating inflammatory responses during a viral infection.11

The study of anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies could be important in the future for another reason: To see whether these medications could be effective as a preventive treatment in patients with persistent headache after Covid-19, regardless of whether these patients have personal migraine history.

An interesting and important message to close this article. Although headache experienced in the infection’s acute phase could be extremely disabling for patients, the evidence points to the presence of headache as a marker of a better Covid-19 prognosis, in terms of a shorter infection period and a lower risk of mortality among hospitalized patients.1,3,12

This brief communication contains current information to help clinicians treat and inform their patients with Covid-sourced headache. Yet, we must keep in mind that the majority of the data reported here and published in the literature refer to studies conducted during the first wave of the pandemic. The emergence of new SARS-CoV-2 variants and vaccines have enormously changed the disease’s clinical presentation and course, so future studies are warranted to re-assess the validity of these findings under new conditions.

References

1. Caronna E, Ballvé A, Llauradó A, Gallardo VJ, et al. Headache: A striking prodromal and persistent symptom, predictive of COVID-19 clinical evolution. Cephalalgia. 2020; Nov;40(13):1410-1421.

2. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018; Jan;38(1):1-211.

3. Trigo J, García-Azorín D, Planchuelo-Gómez Á, et al. Factors associated with the presence of headache in hospitalized COVID-19 patients and impact on prognosis: A retrospective cohort study. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):94. https://thejournalofheadacheandpain.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s10194-020-01165-8

4. Porta-Etessam J, Matías-Guiu JA, González-García N, et al. Spectrum of Headaches Associated With SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Study of Healthcare Professionals. Headache. 2020;60(8):1697–1704.

5. Singh J, Ali A. Headache as the Presenting Symptom in 2 Patients With COVID-19 and a History of Migraine: 2 Case Reports. Headache. 2020;60(8):1773–1776.

6. Membrilla JA, de Lorenzo Í, Sastre M, Díaz de Terán J. Headache as a Cardinal Symptom of Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Cross-Sectional Study. Headache. 2020; Nov;60(10):2176-2191.

7. Caronna E, Alpuente A, Torres-Ferrus M, Pozo-Rosich P. Toward a better understanding of persistent headache after mild COVID-19: Three migraine-like yet distinct scenarios. Headache. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.14197

8. Maassenvandenbrink A, De Vries T, Danser AHJ. Headache medication and the COVID-19 pandemic. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1). https://thejournalofheadacheandpain.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s10194-020-01106-5

9. Arca KN, Smith JH, Chiang CC, et al. COVID-19 and Headache Medicine: A Narrative Review of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug (NSAID) and Corticosteroid Use. Headache. 2020; Sep;60(8): 1558–1568.

10. Hippisley-Cox J, Young D, Coupland C, et al. Risk of severe COVID-19 disease with ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers: Cohort study including 8.3 million people. Heart. 2020;Oct;106(19):1503-1511.

11. Caronna E, José Gallardo V, Alpuente A, Torres-Ferrus M, Sánchez-Mateo NM, Viguera-Romero J, et al. Safety of anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies in patients with migraine during the COVID-19 pandemic: Present and future implications. Neurologia. 2021; Mar 19;36(8):611-617.

12. Gonzalez-Martinez A, Fanjul V, Ramos C, Serrano Ballesteros J, et al. Headache during SARS-CoV-2 infection as an early symptom associated with a more benign course of disease: a case–control study. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28(10):3426–36.

References

1. Caronna E, Ballvé A, Llauradó A, Gallardo VJ, et al. Headache: A striking prodromal and persistent symptom, predictive of COVID-19 clinical evolution. Cephalalgia. 2020; Nov;40(13):1410-1421.

2. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018; Jan;38(1):1-211.

3. Trigo J, García-Azorín D, Planchuelo-Gómez Á, et al. Factors associated with the presence of headache in hospitalized COVID-19 patients and impact on prognosis: A retrospective cohort study. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):94. https://thejournalofheadacheandpain.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s10194-020-01165-8

4. Porta-Etessam J, Matías-Guiu JA, González-García N, et al. Spectrum of Headaches Associated With SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Study of Healthcare Professionals. Headache. 2020;60(8):1697–1704.

5. Singh J, Ali A. Headache as the Presenting Symptom in 2 Patients With COVID-19 and a History of Migraine: 2 Case Reports. Headache. 2020;60(8):1773–1776.

6. Membrilla JA, de Lorenzo Í, Sastre M, Díaz de Terán J. Headache as a Cardinal Symptom of Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Cross-Sectional Study. Headache. 2020; Nov;60(10):2176-2191.

7. Caronna E, Alpuente A, Torres-Ferrus M, Pozo-Rosich P. Toward a better understanding of persistent headache after mild COVID-19: Three migraine-like yet distinct scenarios. Headache. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.14197

8. Maassenvandenbrink A, De Vries T, Danser AHJ. Headache medication and the COVID-19 pandemic. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1). https://thejournalofheadacheandpain.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s10194-020-01106-5

9. Arca KN, Smith JH, Chiang CC, et al. COVID-19 and Headache Medicine: A Narrative Review of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug (NSAID) and Corticosteroid Use. Headache. 2020; Sep;60(8): 1558–1568.

10. Hippisley-Cox J, Young D, Coupland C, et al. Risk of severe COVID-19 disease with ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers: Cohort study including 8.3 million people. Heart. 2020;Oct;106(19):1503-1511.

11. Caronna E, José Gallardo V, Alpuente A, Torres-Ferrus M, Sánchez-Mateo NM, Viguera-Romero J, et al. Safety of anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies in patients with migraine during the COVID-19 pandemic: Present and future implications. Neurologia. 2021; Mar 19;36(8):611-617.

12. Gonzalez-Martinez A, Fanjul V, Ramos C, Serrano Ballesteros J, et al. Headache during SARS-CoV-2 infection as an early symptom associated with a more benign course of disease: a case–control study. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28(10):3426–36.

Old age and liver stiffness on transient elastography may predict HCC occurrence after HCV eradication

Key clinical point: Advanced age and liver stiffness measurement (LSM) on transient elastography, both pretreatment and at 24-week sustained virological response (SVR24), may aid in predicting the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) who achieved SVR to interferon (IFN)-free direct-acting antivirals (DAA).

Main finding: Multivariate analysis revealed age ≥71 years (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 3.402; P = .005) and LSM ≥9.2 kPa (aHR 6.328; P < .001) to be the significant predictive factors at pretreatment and age ≥71 years (aHR 2.689; P = .014) and LSM ≥8.4 kPa (aHR 6.642; P < .001) at SVR24.

Study details: This was a multicenter retrospective study including 567 patients with no history of HCC but with HCV infection treated with DAAs and who achieved SVR24.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan; Japan Society for the Promotion of Science; Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development; and Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan. Some authors declared receiving speaker fees/research grants from various pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Nakai M et al. Sci Rep. 2022;12:1449 (Jan 27). Doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-05492-5.

Key clinical point: Advanced age and liver stiffness measurement (LSM) on transient elastography, both pretreatment and at 24-week sustained virological response (SVR24), may aid in predicting the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) who achieved SVR to interferon (IFN)-free direct-acting antivirals (DAA).

Main finding: Multivariate analysis revealed age ≥71 years (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 3.402; P = .005) and LSM ≥9.2 kPa (aHR 6.328; P < .001) to be the significant predictive factors at pretreatment and age ≥71 years (aHR 2.689; P = .014) and LSM ≥8.4 kPa (aHR 6.642; P < .001) at SVR24.

Study details: This was a multicenter retrospective study including 567 patients with no history of HCC but with HCV infection treated with DAAs and who achieved SVR24.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan; Japan Society for the Promotion of Science; Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development; and Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan. Some authors declared receiving speaker fees/research grants from various pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Nakai M et al. Sci Rep. 2022;12:1449 (Jan 27). Doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-05492-5.

Key clinical point: Advanced age and liver stiffness measurement (LSM) on transient elastography, both pretreatment and at 24-week sustained virological response (SVR24), may aid in predicting the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) who achieved SVR to interferon (IFN)-free direct-acting antivirals (DAA).

Main finding: Multivariate analysis revealed age ≥71 years (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 3.402; P = .005) and LSM ≥9.2 kPa (aHR 6.328; P < .001) to be the significant predictive factors at pretreatment and age ≥71 years (aHR 2.689; P = .014) and LSM ≥8.4 kPa (aHR 6.642; P < .001) at SVR24.

Study details: This was a multicenter retrospective study including 567 patients with no history of HCC but with HCV infection treated with DAAs and who achieved SVR24.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan; Japan Society for the Promotion of Science; Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development; and Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan. Some authors declared receiving speaker fees/research grants from various pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Nakai M et al. Sci Rep. 2022;12:1449 (Jan 27). Doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-05492-5.

Liver resection in HCC: Robot-assisted and laparoscopic vs. open

Key clinical point: Robot-assisted liver resection (RALR) and laparoscopic liver resection (LLR) show similar long-term oncological outcomes to open liver resection (OLR) in the treatment of Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage 0-A hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) along with allowing faster patient recovery.

Main finding: OLR, LLR, and RALR achieved 5-year overall survival rates of 78.6%, 76.8%, and 74.4% (P = .90) and 5-year disease-free survival rates of 57.9%, 51.3%, and 51.8% (P = .64), respectively. Patients undergoing LLR (6 days) or RALR (8 days) vs. OLR (12 days) recovered faster (both P < .001).

Study details: The data come from a single-center prospective study that compared 3 propensity score-matched cohorts of 56 patients each who were aged 14-75 years and received no previous treatment before undergoing either ALR, LLR, or OLR due to BCLC stage 0-A HCC.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Key Project of Science and Technology in Hubei Province, General Project of Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province, and General Project of Health Commission of Hubei Province. No conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Source: Zhu P et al. Ann Surg. 2022 (Jan 25). Doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005380.

Key clinical point: Robot-assisted liver resection (RALR) and laparoscopic liver resection (LLR) show similar long-term oncological outcomes to open liver resection (OLR) in the treatment of Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage 0-A hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) along with allowing faster patient recovery.

Main finding: OLR, LLR, and RALR achieved 5-year overall survival rates of 78.6%, 76.8%, and 74.4% (P = .90) and 5-year disease-free survival rates of 57.9%, 51.3%, and 51.8% (P = .64), respectively. Patients undergoing LLR (6 days) or RALR (8 days) vs. OLR (12 days) recovered faster (both P < .001).

Study details: The data come from a single-center prospective study that compared 3 propensity score-matched cohorts of 56 patients each who were aged 14-75 years and received no previous treatment before undergoing either ALR, LLR, or OLR due to BCLC stage 0-A HCC.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Key Project of Science and Technology in Hubei Province, General Project of Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province, and General Project of Health Commission of Hubei Province. No conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Source: Zhu P et al. Ann Surg. 2022 (Jan 25). Doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005380.

Key clinical point: Robot-assisted liver resection (RALR) and laparoscopic liver resection (LLR) show similar long-term oncological outcomes to open liver resection (OLR) in the treatment of Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage 0-A hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) along with allowing faster patient recovery.

Main finding: OLR, LLR, and RALR achieved 5-year overall survival rates of 78.6%, 76.8%, and 74.4% (P = .90) and 5-year disease-free survival rates of 57.9%, 51.3%, and 51.8% (P = .64), respectively. Patients undergoing LLR (6 days) or RALR (8 days) vs. OLR (12 days) recovered faster (both P < .001).

Study details: The data come from a single-center prospective study that compared 3 propensity score-matched cohorts of 56 patients each who were aged 14-75 years and received no previous treatment before undergoing either ALR, LLR, or OLR due to BCLC stage 0-A HCC.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Key Project of Science and Technology in Hubei Province, General Project of Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province, and General Project of Health Commission of Hubei Province. No conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Source: Zhu P et al. Ann Surg. 2022 (Jan 25). Doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005380.

Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate vs. entecavir: Curtailing the risk of chronic hepatitis B-induced HCC

Key clinical point: In treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis B, therapy with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) vs. entecavir (ETV) is associated with a lower risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the future.

Main finding: During the follow-up, patients receiving TDF showed a lower crude HCC incidence rate than those receiving ETV (0.30 vs. 0.62 per 100 person-years). TDF vs. ETV was associated with a significantly reduced risk of HCC occurrence (adjusted subdistribution hazard ratio 0.58; P = .01).

Study details: The data come from a retrospective cohort study including 10,061 adult treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis B but no evidence of HCC and who initiated therapy with ETV (n = 3,934) or TDF (n = 6,127).

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Gilead Sciences. WR Kim, M Lu, and S Gordon declared serving as an advisory board member and consultant for or receiving research funding from Gilead Sciences. The rest of the authors are current or former employees and stockholders of Gilead Sciences.

Source: Kim WR et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022 (Feb 8). Doi: 10.1111/apt.16786.

Key clinical point: In treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis B, therapy with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) vs. entecavir (ETV) is associated with a lower risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the future.

Main finding: During the follow-up, patients receiving TDF showed a lower crude HCC incidence rate than those receiving ETV (0.30 vs. 0.62 per 100 person-years). TDF vs. ETV was associated with a significantly reduced risk of HCC occurrence (adjusted subdistribution hazard ratio 0.58; P = .01).

Study details: The data come from a retrospective cohort study including 10,061 adult treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis B but no evidence of HCC and who initiated therapy with ETV (n = 3,934) or TDF (n = 6,127).

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Gilead Sciences. WR Kim, M Lu, and S Gordon declared serving as an advisory board member and consultant for or receiving research funding from Gilead Sciences. The rest of the authors are current or former employees and stockholders of Gilead Sciences.

Source: Kim WR et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022 (Feb 8). Doi: 10.1111/apt.16786.

Key clinical point: In treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis B, therapy with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) vs. entecavir (ETV) is associated with a lower risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the future.

Main finding: During the follow-up, patients receiving TDF showed a lower crude HCC incidence rate than those receiving ETV (0.30 vs. 0.62 per 100 person-years). TDF vs. ETV was associated with a significantly reduced risk of HCC occurrence (adjusted subdistribution hazard ratio 0.58; P = .01).

Study details: The data come from a retrospective cohort study including 10,061 adult treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis B but no evidence of HCC and who initiated therapy with ETV (n = 3,934) or TDF (n = 6,127).

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Gilead Sciences. WR Kim, M Lu, and S Gordon declared serving as an advisory board member and consultant for or receiving research funding from Gilead Sciences. The rest of the authors are current or former employees and stockholders of Gilead Sciences.

Source: Kim WR et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022 (Feb 8). Doi: 10.1111/apt.16786.

Sorafenib plus HAIC a favorable therapeutic option for HCC with major portal vein tumor thrombosis

Key clinical point: Compared with sorafenib alone, its combination with 3cir-OFF hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) offers significantly prolonged survival and an acceptable safety profile in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and major portal vein tumor thrombosis (PVTT).

Main finding: Sorafenib plus HAIC vs. sorafenib alone led to a longer median overall survival (16.3 months vs. 6.5 months; hazard ratio [HR] 0.28; P < .001) and progression-free survival (9.0 months vs. 2.5 months; HR 0.26; P < .001) but more frequent grade 3/4 adverse events.