User login

Mpox (Monkeypox) Clinical Pearls

The 2022 mpox (monkeypox) virus outbreak represents the latest example of how infectious diseases with previously limited reach can spread in a globalized society. More than 86,000 cases have been reported worldwide, with more than 30,000 cases in the United States as of March 15, 2023.1 Herein, we summarize the key features of mpox infection for the dermatologist.

Mpox Transmission

The mpox virus is a double-stranded DNA virus of the Orthopoxvirus genus and Poxviridae family.2,3 There are 2 types of the mpox virus: clade I (formerly the Congo Basin clade) and clade II (formerly the West African clade). Clade I causes more severe disease (10% mortality rate), while clade II is associated with lower mortality (1%–3%) and has been split into subclades of IIa (exhibits zoonotic transmission) and IIb (exhibits human-to-human spread).3,4 The current outbreak is caused by clade IIb, and patients typically have no travel history to classic endemic regions.5,6

In endemic countries, mpox transmission is zoonotic from small forest animals. In nonendemic countries, sporadic cases rarely have been reported, including a cluster in the United States in 2003 related to pet prairie dogs. In stark contrast, human-to-human transmission is occurring in the current epidemic mainly via intimate skin-to-skin contact and possibly via sexual fluids, meeting the criteria for a sexually transmitted infection. However, nonsexual transmission does still occur, though it is less common.7 Many of the reported cases so far are in young to middle-aged men who have sex with men (MSM).2,8 However, it is crucial to understand that mpox is not exclusive to the MSM population; the virus has been transmitted to heterosexual males, females, children, and even household pets of infected individuals.2,9,10 Labeling mpox as exclusive to the MSM community is both inaccurate and inappropriately stigmatizing.

Cutaneous Presentation and Diagnosis of Mpox

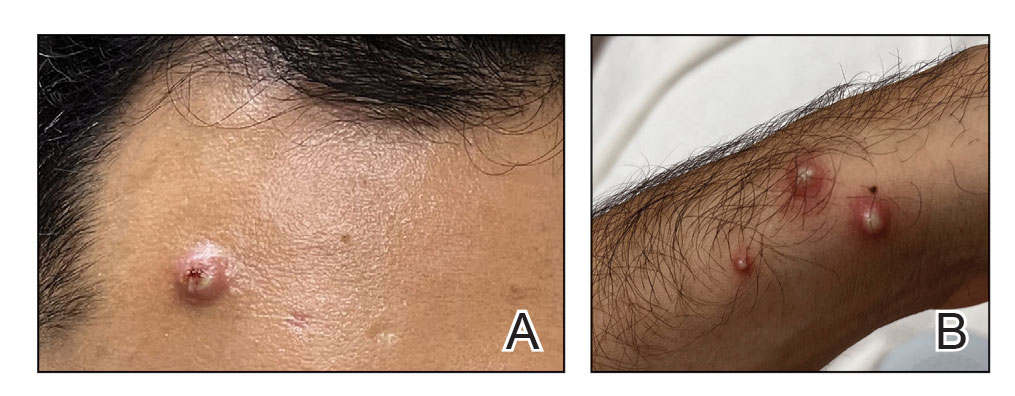

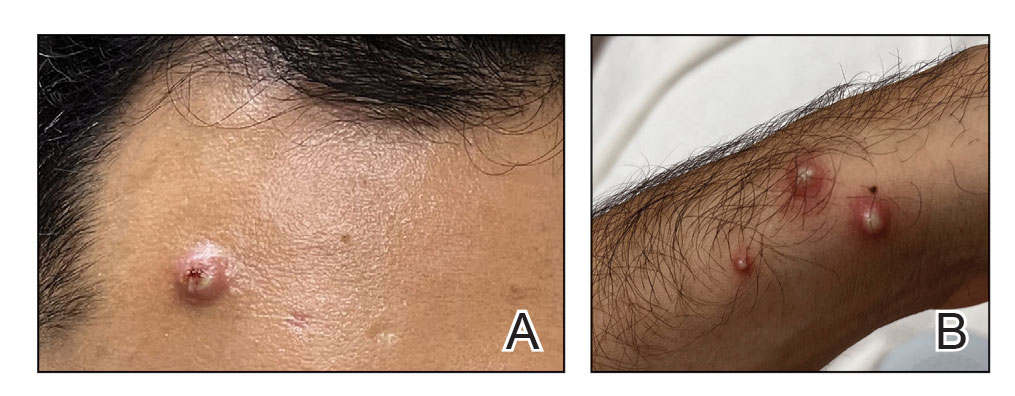

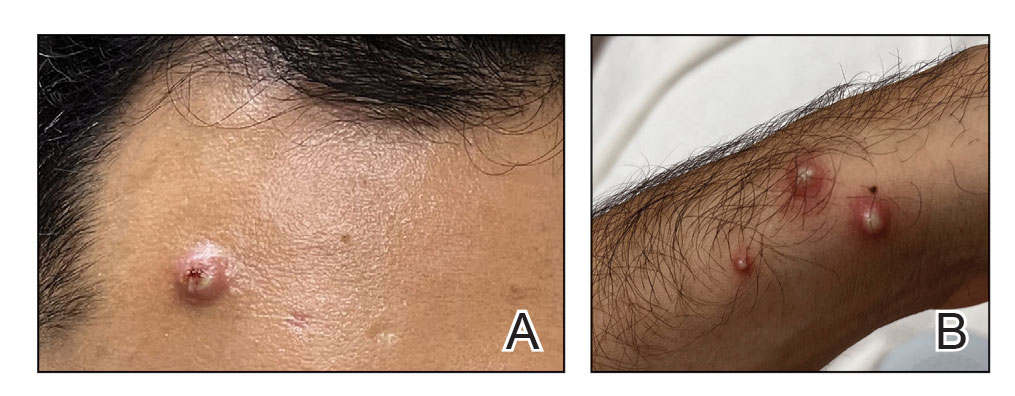

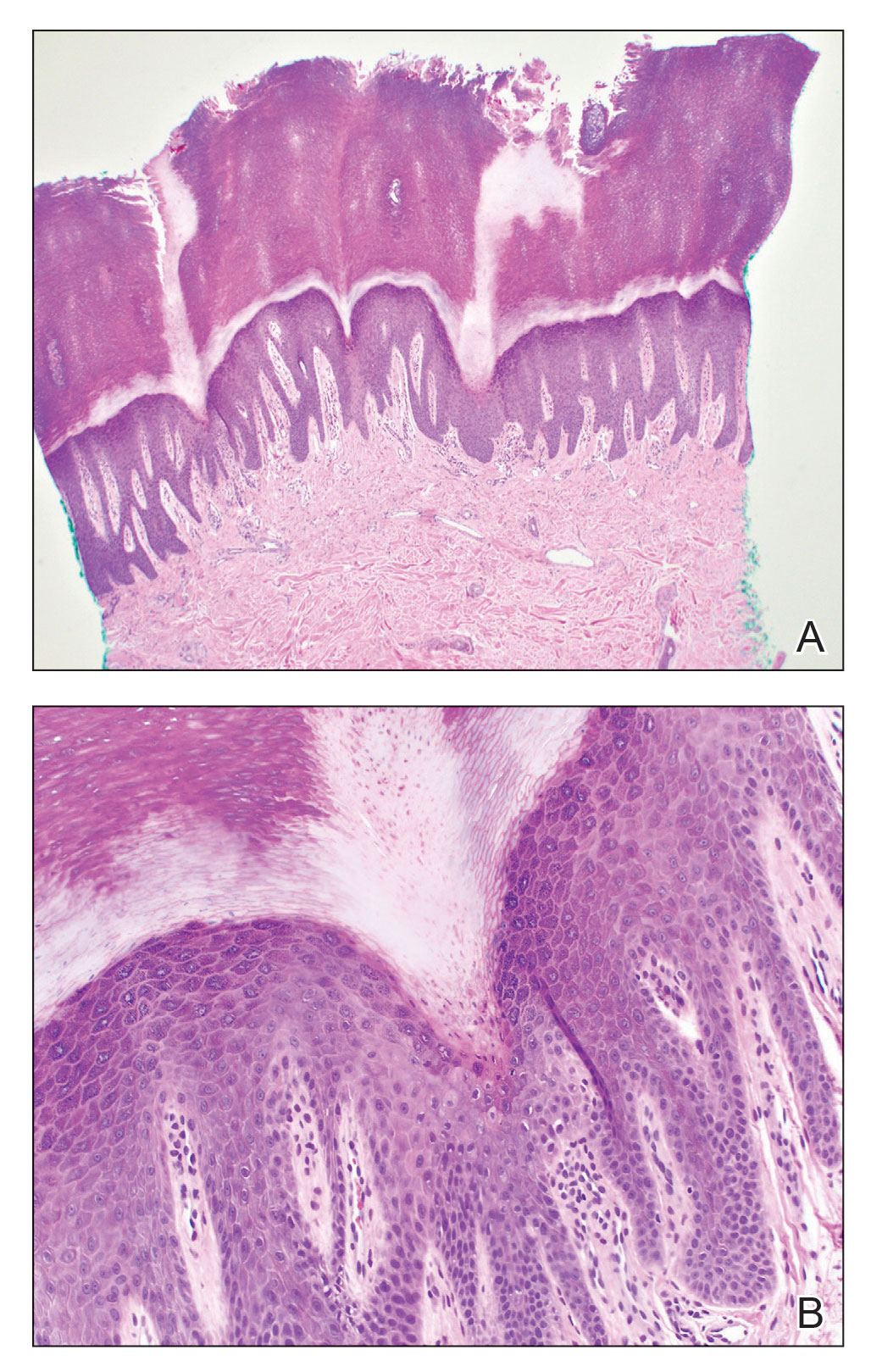

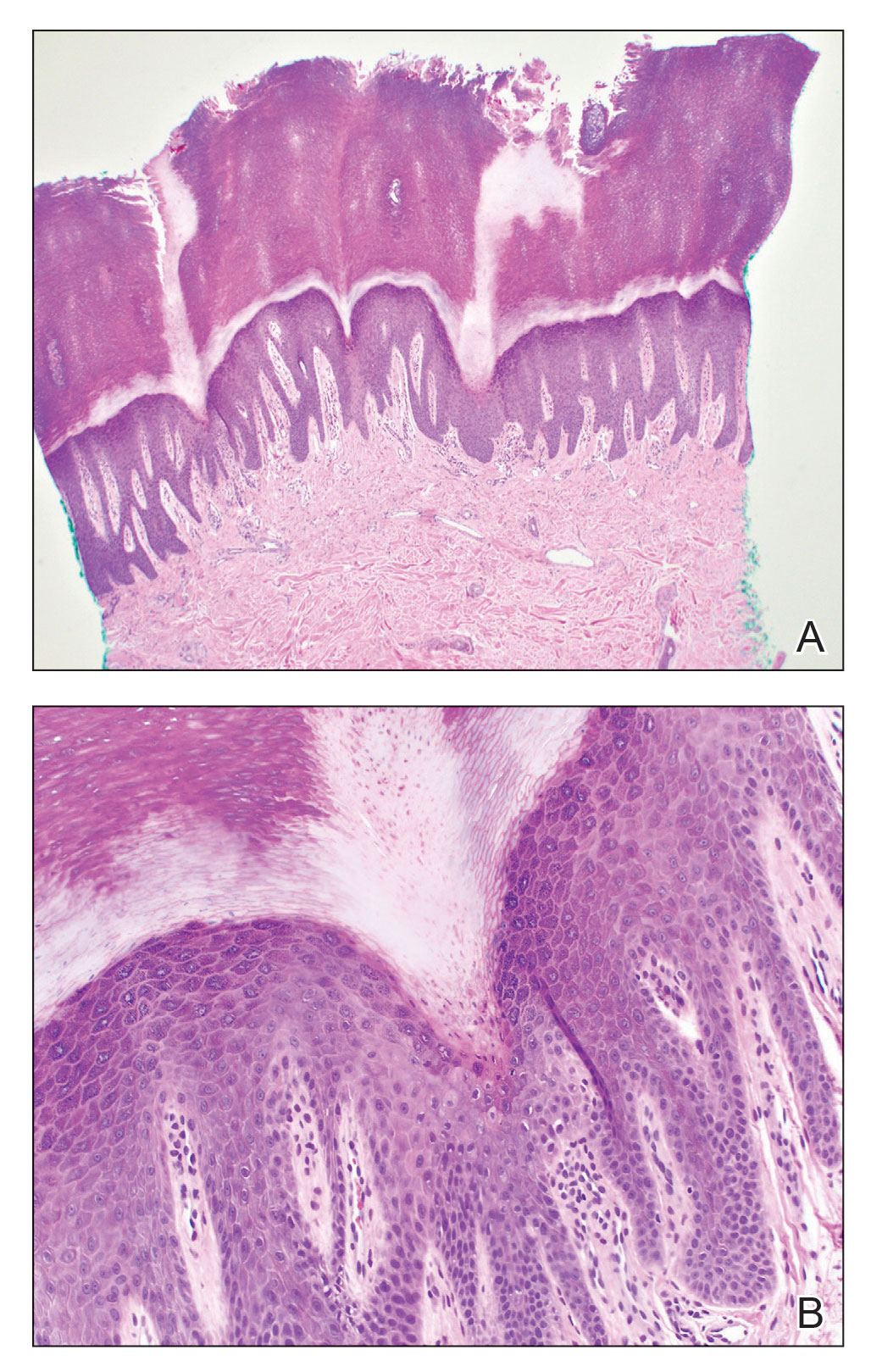

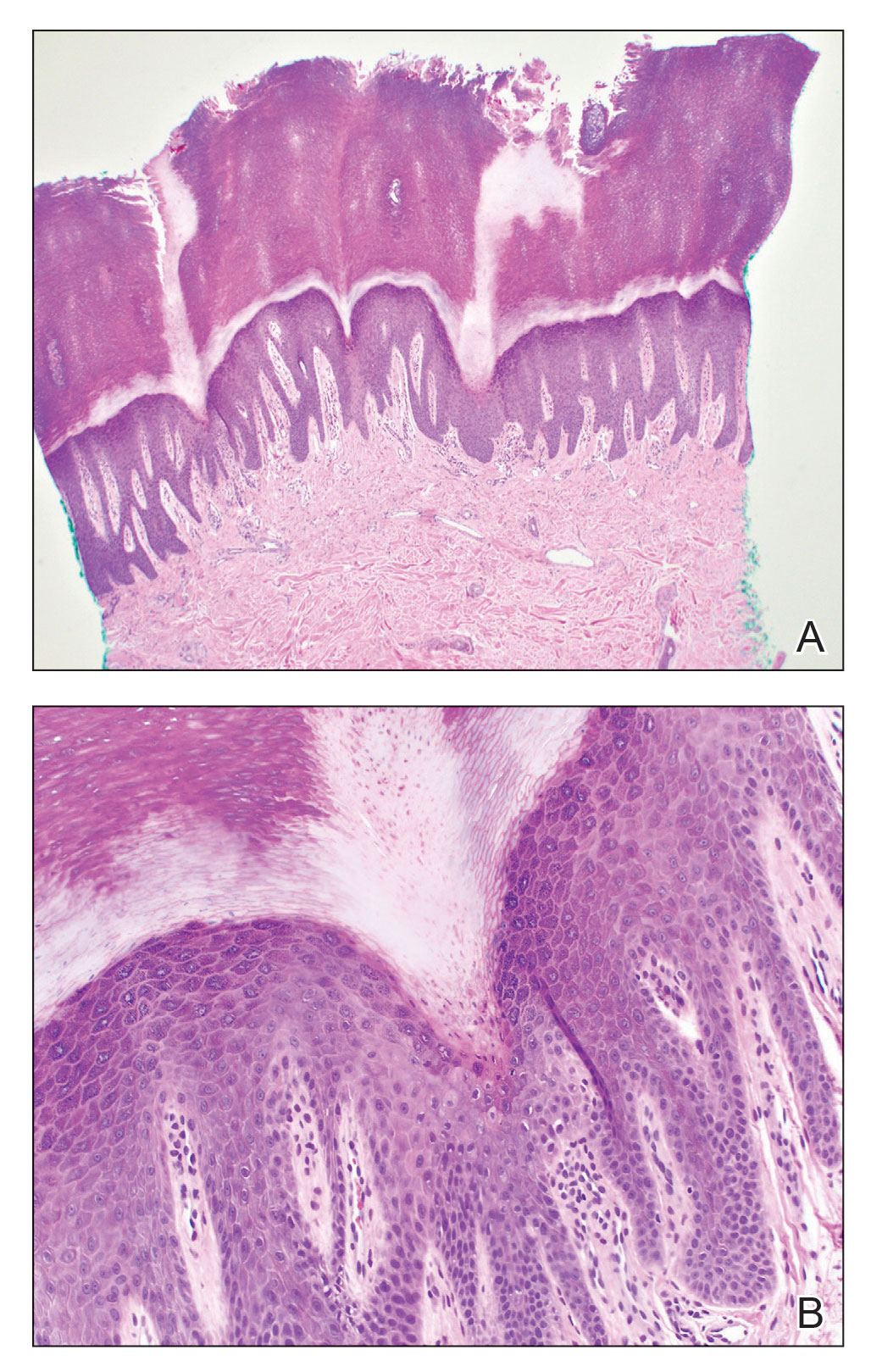

Mpox has an incubation time of approximately 9 days (range, 7–21 days), after which affected persons develop macular lesions that evolve over 2 to 4 weeks into papules, vesicles, and deep-seated pustules before crusting over and resolving with possible residual scarring.2,3,5,9,11,12 Palmoplantar involvement is a key feature.11 Although in some cases there will be multiple lesions with centrifugal progression, the lesions also may be few in number, with some patients presenting with a single lesion in the anogenital region or on the face, hand, or foot (Figure).6,9 Systemic symptoms such as prodromal fever, lymphadenopathy, and headache are common but not universal.9,13 Potential complications include penile edema, proctitis, bacterial superinfection, tonsillitis, conjunctivitis, encephalitis, and pneumonia.5,9,13

A high index of suspicion is needed to diagnose mpox infection. The differential diagnosis includes smallpox; varicella-zoster virus (primary or reactivation); secondary syphilis; measles; herpes simplex virus; molluscum contagiosum; hand, foot, and mouth disease; and disseminated gonococcal infection.2,3 For lesions confined to the genital area, sexually transmitted infections (eg, chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum) as well as non–sexually related acute genital ulcers (Lipschütz ulcers) should be considered.2

Certain clinical features may help in distinguishing mpox from other diseases. Mpox exhibits synchronous progression and centrifugal distribution when multiple lesions are present; in contrast, the lesions of primary varicella (chickenpox) appear in multiple different stages, and those of localized herpes zoster (shingles) exhibit a dermatomal distribution. When these features are present, mpox causes a greater degree of lymphadenopathy and systemic symptoms than primary varicella.3Clinical diagnosis of mpox is more than 90% sensitive but only 9% to 26% specific.3 To confirm the diagnosis, a viral swab vigorously obtained from active skin lesions should be sent in viral transport media for mpox DNA-specific polymerase chain reaction testing, which is available from major laboratories.2,3 Other supportive tests include serum studies for anti–mpox virus immunoglobulins and immunohistochemical staining for viral antigens on skin biopsy specimens.2 When evaluating suspected and confirmed mpox cases, dermatologists should wear a gown, gloves, a fitted N95 mask, and eye protection to prevent infection.5

Treating Mpox

Symptomatic mpox infection can last for up to 2 to 5 weeks.3 The patient is no longer infectious once the lesions have crusted over.3,11 The majority of cases require supportive care only.2,3,5,14 However, mpox remains a potentially fatal disease, with 38 deaths to date in the current outbreak.1 High-risk populations include children younger than 8 years, pregnant women, and individuals who are immunocompromised.15 Tecovirimat, an antiviral medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for smallpox, is available via the expanded access Investigational New Drug (EA-IND) protocol to treat severe mpox cases but is not widely available in the United States.6,16-18 Brincidofovir, a prodrug of the antiviral cidofovir, possesses single-patient emergency use Investigational New Drug (e-IND) status for treatment of mpox but also is not widely available in the United States.17 Intravenous vaccinia immune globulin is under consideration for high-risk individuals, but little is known regarding its efficacy against mpox.5,16,17

Two smallpox vaccines—JYNNEOS (Bavarian Nordic) and ACAM2000 (Emergent Bio Solutions)—are available for both preexposure and postexposure prophylaxis against mpox virus.19 At this time, only JYNNEOS is FDA approved for the prevention of mpox; ACAM2000 can be used against mpox under the FDA’s EA-IND protocol, which involves additional requirements, including informed consent from the patient.20 ACAM2000 is a live, replication-competent vaccine that carries a warning of increased risk for side effects in patients with cardiac disease, pregnancy, immunocompromise, and a history or presence of eczema and other skin conditions.3,21,22 JYNNEOS is a live but replication-deficient virus and therefore does not carry these warnings.3,21,22

Final Thoughts

Mpox is no longer an obscure illness occurring in limited geographic areas. Dermatologists must remain highly vigilant when evaluating any patient for new-onset vesicular or pustular eruptions to combat this ongoing public health threat. This issue of Cutis® also features a thorough mpox update on the clinical presentation, vaccine guidance, and management.23

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mpox: 2022 Outbreak Cases and Data. Updated March 15, 2023. Accessed March 121, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/response/2022/

- Srivastava G. Human monkeypox disease [published online August 10, 2022]. Clin Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2022.08.009

- Bryer J, Freeman EE, Rosenbach M. Monkeypox emerges on a global scale: a historical review and dermatologic primer [published online July 8, 2022]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.07.007

- Americo JL, Earl PL, Moss B. Virulence differences of mpox (monkeypox) virus clades I, IIa, and IIb.1 in a small animal model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120:E2220415120. doi:10.1073 /pnas.2220415120

- Guarner J, Del Rio C, Malani PN. Monkeypox in 2022—what clinicians need to know. JAMA. 2022;328:139-140. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.10802

- Looi MK. Monkeypox: what we know about the 2022 outbreak so far [published online August 23, 2022]. BMJ. doi:10.1136/bmj.o2058

- Allan-Blitz LT, Gandhi M, Adamson P, et al. A position statement on mpox as a sexually transmitted disease [published online December 22, 2022]. Clin Infect Dis. doi:10.1093/cid/ciac960

- Cabanillas B, Murdaca G, Guemari A, et al. A compilation answering 50 questions on monkeypox virus and the current monkeypox outbreak. Allergy. 2023;78:639-662. doi:10.1111/all.15633

- Tarín-Vicente EJ, Alemany A, Agud-Dios M, et al. Clinical presentation and virological assessment of confirmed human monkeypox virus cases in Spain: a prospective observational cohort study [published online August 8, 2022]. Lancet. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01436-2

- Seang S, Burrel S, Todesco E, et al. Evidence of human-to-dog transmission of monkeypox virus. Lancet. 2022;400:658-659. doi:10.1016 /s0140-6736(22)01487-8

- Ramdass P, Mullick S, Farber HF. Viral skin diseases. Prim Care. 2015;42:517-67. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2015.08.006

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mpox: Clinical Recognition. Updated August 23, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cdc .gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/clinicians/clinical-recognition.html

- Mpox Cases by Age and Gender, Race/Ethnicity, and Symptoms. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated March 15, 2023. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox /response/2022/demographics.html

- Kawsar A, Hussain K, Roberts N. The return of monkeypox: key pointers for dermatologists [published online July 29, 2022]. Clin Exp Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ced.15357

- Khanna U, Bishnoi A, Vinay K. Current outbreak of monkeypox— essentials for the dermatologist [published online June 23, 2022]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.1170

- Fox T, Gould S, Princy N, et al. Therapeutics for treating mpox in humans. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;3:CD015769. doi:10.1002/14651858 .CD015769

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Treatment information for healthcare professionals. Updated March 3, 2023. Accessed March 24, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/clinicians /treatment.html#anchor_1666886364947

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidance for tecovirimat use. Updated February 23, 2023. Accessed March 24, 2023. https://www .cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/clinicians/Tecovirimat.html

- Interim Clinical Considerations for Use of JYNNEOS and ACAM2000 Vaccines During the 2022 U.S. Monkeypox Outbreak. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated October 19, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/health-departments/vaccine-considerations.html

- Key Facts About Vaccines to Prevent Monkeypox Disease. US Food and Drug Administration. Updated August 18, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/vaccines/key-facts-aboutvaccines-prevent-monkeypox-disease

- Smallpox: Vaccines. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated August 8, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/clinicians/vaccines.html

- ACAM2000. Package insert. Emergent Product Development Gaithersburg Inc; 2019.

- Cices A, Prasad S, Akselrad M, et al. Mpox update: clinical presentation, vaccination guidance, and management. Cutis. 2023;111:197-202. doi:10.12788/cutis.0745

The 2022 mpox (monkeypox) virus outbreak represents the latest example of how infectious diseases with previously limited reach can spread in a globalized society. More than 86,000 cases have been reported worldwide, with more than 30,000 cases in the United States as of March 15, 2023.1 Herein, we summarize the key features of mpox infection for the dermatologist.

Mpox Transmission

The mpox virus is a double-stranded DNA virus of the Orthopoxvirus genus and Poxviridae family.2,3 There are 2 types of the mpox virus: clade I (formerly the Congo Basin clade) and clade II (formerly the West African clade). Clade I causes more severe disease (10% mortality rate), while clade II is associated with lower mortality (1%–3%) and has been split into subclades of IIa (exhibits zoonotic transmission) and IIb (exhibits human-to-human spread).3,4 The current outbreak is caused by clade IIb, and patients typically have no travel history to classic endemic regions.5,6

In endemic countries, mpox transmission is zoonotic from small forest animals. In nonendemic countries, sporadic cases rarely have been reported, including a cluster in the United States in 2003 related to pet prairie dogs. In stark contrast, human-to-human transmission is occurring in the current epidemic mainly via intimate skin-to-skin contact and possibly via sexual fluids, meeting the criteria for a sexually transmitted infection. However, nonsexual transmission does still occur, though it is less common.7 Many of the reported cases so far are in young to middle-aged men who have sex with men (MSM).2,8 However, it is crucial to understand that mpox is not exclusive to the MSM population; the virus has been transmitted to heterosexual males, females, children, and even household pets of infected individuals.2,9,10 Labeling mpox as exclusive to the MSM community is both inaccurate and inappropriately stigmatizing.

Cutaneous Presentation and Diagnosis of Mpox

Mpox has an incubation time of approximately 9 days (range, 7–21 days), after which affected persons develop macular lesions that evolve over 2 to 4 weeks into papules, vesicles, and deep-seated pustules before crusting over and resolving with possible residual scarring.2,3,5,9,11,12 Palmoplantar involvement is a key feature.11 Although in some cases there will be multiple lesions with centrifugal progression, the lesions also may be few in number, with some patients presenting with a single lesion in the anogenital region or on the face, hand, or foot (Figure).6,9 Systemic symptoms such as prodromal fever, lymphadenopathy, and headache are common but not universal.9,13 Potential complications include penile edema, proctitis, bacterial superinfection, tonsillitis, conjunctivitis, encephalitis, and pneumonia.5,9,13

A high index of suspicion is needed to diagnose mpox infection. The differential diagnosis includes smallpox; varicella-zoster virus (primary or reactivation); secondary syphilis; measles; herpes simplex virus; molluscum contagiosum; hand, foot, and mouth disease; and disseminated gonococcal infection.2,3 For lesions confined to the genital area, sexually transmitted infections (eg, chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum) as well as non–sexually related acute genital ulcers (Lipschütz ulcers) should be considered.2

Certain clinical features may help in distinguishing mpox from other diseases. Mpox exhibits synchronous progression and centrifugal distribution when multiple lesions are present; in contrast, the lesions of primary varicella (chickenpox) appear in multiple different stages, and those of localized herpes zoster (shingles) exhibit a dermatomal distribution. When these features are present, mpox causes a greater degree of lymphadenopathy and systemic symptoms than primary varicella.3Clinical diagnosis of mpox is more than 90% sensitive but only 9% to 26% specific.3 To confirm the diagnosis, a viral swab vigorously obtained from active skin lesions should be sent in viral transport media for mpox DNA-specific polymerase chain reaction testing, which is available from major laboratories.2,3 Other supportive tests include serum studies for anti–mpox virus immunoglobulins and immunohistochemical staining for viral antigens on skin biopsy specimens.2 When evaluating suspected and confirmed mpox cases, dermatologists should wear a gown, gloves, a fitted N95 mask, and eye protection to prevent infection.5

Treating Mpox

Symptomatic mpox infection can last for up to 2 to 5 weeks.3 The patient is no longer infectious once the lesions have crusted over.3,11 The majority of cases require supportive care only.2,3,5,14 However, mpox remains a potentially fatal disease, with 38 deaths to date in the current outbreak.1 High-risk populations include children younger than 8 years, pregnant women, and individuals who are immunocompromised.15 Tecovirimat, an antiviral medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for smallpox, is available via the expanded access Investigational New Drug (EA-IND) protocol to treat severe mpox cases but is not widely available in the United States.6,16-18 Brincidofovir, a prodrug of the antiviral cidofovir, possesses single-patient emergency use Investigational New Drug (e-IND) status for treatment of mpox but also is not widely available in the United States.17 Intravenous vaccinia immune globulin is under consideration for high-risk individuals, but little is known regarding its efficacy against mpox.5,16,17

Two smallpox vaccines—JYNNEOS (Bavarian Nordic) and ACAM2000 (Emergent Bio Solutions)—are available for both preexposure and postexposure prophylaxis against mpox virus.19 At this time, only JYNNEOS is FDA approved for the prevention of mpox; ACAM2000 can be used against mpox under the FDA’s EA-IND protocol, which involves additional requirements, including informed consent from the patient.20 ACAM2000 is a live, replication-competent vaccine that carries a warning of increased risk for side effects in patients with cardiac disease, pregnancy, immunocompromise, and a history or presence of eczema and other skin conditions.3,21,22 JYNNEOS is a live but replication-deficient virus and therefore does not carry these warnings.3,21,22

Final Thoughts

Mpox is no longer an obscure illness occurring in limited geographic areas. Dermatologists must remain highly vigilant when evaluating any patient for new-onset vesicular or pustular eruptions to combat this ongoing public health threat. This issue of Cutis® also features a thorough mpox update on the clinical presentation, vaccine guidance, and management.23

The 2022 mpox (monkeypox) virus outbreak represents the latest example of how infectious diseases with previously limited reach can spread in a globalized society. More than 86,000 cases have been reported worldwide, with more than 30,000 cases in the United States as of March 15, 2023.1 Herein, we summarize the key features of mpox infection for the dermatologist.

Mpox Transmission

The mpox virus is a double-stranded DNA virus of the Orthopoxvirus genus and Poxviridae family.2,3 There are 2 types of the mpox virus: clade I (formerly the Congo Basin clade) and clade II (formerly the West African clade). Clade I causes more severe disease (10% mortality rate), while clade II is associated with lower mortality (1%–3%) and has been split into subclades of IIa (exhibits zoonotic transmission) and IIb (exhibits human-to-human spread).3,4 The current outbreak is caused by clade IIb, and patients typically have no travel history to classic endemic regions.5,6

In endemic countries, mpox transmission is zoonotic from small forest animals. In nonendemic countries, sporadic cases rarely have been reported, including a cluster in the United States in 2003 related to pet prairie dogs. In stark contrast, human-to-human transmission is occurring in the current epidemic mainly via intimate skin-to-skin contact and possibly via sexual fluids, meeting the criteria for a sexually transmitted infection. However, nonsexual transmission does still occur, though it is less common.7 Many of the reported cases so far are in young to middle-aged men who have sex with men (MSM).2,8 However, it is crucial to understand that mpox is not exclusive to the MSM population; the virus has been transmitted to heterosexual males, females, children, and even household pets of infected individuals.2,9,10 Labeling mpox as exclusive to the MSM community is both inaccurate and inappropriately stigmatizing.

Cutaneous Presentation and Diagnosis of Mpox

Mpox has an incubation time of approximately 9 days (range, 7–21 days), after which affected persons develop macular lesions that evolve over 2 to 4 weeks into papules, vesicles, and deep-seated pustules before crusting over and resolving with possible residual scarring.2,3,5,9,11,12 Palmoplantar involvement is a key feature.11 Although in some cases there will be multiple lesions with centrifugal progression, the lesions also may be few in number, with some patients presenting with a single lesion in the anogenital region or on the face, hand, or foot (Figure).6,9 Systemic symptoms such as prodromal fever, lymphadenopathy, and headache are common but not universal.9,13 Potential complications include penile edema, proctitis, bacterial superinfection, tonsillitis, conjunctivitis, encephalitis, and pneumonia.5,9,13

A high index of suspicion is needed to diagnose mpox infection. The differential diagnosis includes smallpox; varicella-zoster virus (primary or reactivation); secondary syphilis; measles; herpes simplex virus; molluscum contagiosum; hand, foot, and mouth disease; and disseminated gonococcal infection.2,3 For lesions confined to the genital area, sexually transmitted infections (eg, chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum) as well as non–sexually related acute genital ulcers (Lipschütz ulcers) should be considered.2

Certain clinical features may help in distinguishing mpox from other diseases. Mpox exhibits synchronous progression and centrifugal distribution when multiple lesions are present; in contrast, the lesions of primary varicella (chickenpox) appear in multiple different stages, and those of localized herpes zoster (shingles) exhibit a dermatomal distribution. When these features are present, mpox causes a greater degree of lymphadenopathy and systemic symptoms than primary varicella.3Clinical diagnosis of mpox is more than 90% sensitive but only 9% to 26% specific.3 To confirm the diagnosis, a viral swab vigorously obtained from active skin lesions should be sent in viral transport media for mpox DNA-specific polymerase chain reaction testing, which is available from major laboratories.2,3 Other supportive tests include serum studies for anti–mpox virus immunoglobulins and immunohistochemical staining for viral antigens on skin biopsy specimens.2 When evaluating suspected and confirmed mpox cases, dermatologists should wear a gown, gloves, a fitted N95 mask, and eye protection to prevent infection.5

Treating Mpox

Symptomatic mpox infection can last for up to 2 to 5 weeks.3 The patient is no longer infectious once the lesions have crusted over.3,11 The majority of cases require supportive care only.2,3,5,14 However, mpox remains a potentially fatal disease, with 38 deaths to date in the current outbreak.1 High-risk populations include children younger than 8 years, pregnant women, and individuals who are immunocompromised.15 Tecovirimat, an antiviral medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for smallpox, is available via the expanded access Investigational New Drug (EA-IND) protocol to treat severe mpox cases but is not widely available in the United States.6,16-18 Brincidofovir, a prodrug of the antiviral cidofovir, possesses single-patient emergency use Investigational New Drug (e-IND) status for treatment of mpox but also is not widely available in the United States.17 Intravenous vaccinia immune globulin is under consideration for high-risk individuals, but little is known regarding its efficacy against mpox.5,16,17

Two smallpox vaccines—JYNNEOS (Bavarian Nordic) and ACAM2000 (Emergent Bio Solutions)—are available for both preexposure and postexposure prophylaxis against mpox virus.19 At this time, only JYNNEOS is FDA approved for the prevention of mpox; ACAM2000 can be used against mpox under the FDA’s EA-IND protocol, which involves additional requirements, including informed consent from the patient.20 ACAM2000 is a live, replication-competent vaccine that carries a warning of increased risk for side effects in patients with cardiac disease, pregnancy, immunocompromise, and a history or presence of eczema and other skin conditions.3,21,22 JYNNEOS is a live but replication-deficient virus and therefore does not carry these warnings.3,21,22

Final Thoughts

Mpox is no longer an obscure illness occurring in limited geographic areas. Dermatologists must remain highly vigilant when evaluating any patient for new-onset vesicular or pustular eruptions to combat this ongoing public health threat. This issue of Cutis® also features a thorough mpox update on the clinical presentation, vaccine guidance, and management.23

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mpox: 2022 Outbreak Cases and Data. Updated March 15, 2023. Accessed March 121, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/response/2022/

- Srivastava G. Human monkeypox disease [published online August 10, 2022]. Clin Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2022.08.009

- Bryer J, Freeman EE, Rosenbach M. Monkeypox emerges on a global scale: a historical review and dermatologic primer [published online July 8, 2022]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.07.007

- Americo JL, Earl PL, Moss B. Virulence differences of mpox (monkeypox) virus clades I, IIa, and IIb.1 in a small animal model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120:E2220415120. doi:10.1073 /pnas.2220415120

- Guarner J, Del Rio C, Malani PN. Monkeypox in 2022—what clinicians need to know. JAMA. 2022;328:139-140. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.10802

- Looi MK. Monkeypox: what we know about the 2022 outbreak so far [published online August 23, 2022]. BMJ. doi:10.1136/bmj.o2058

- Allan-Blitz LT, Gandhi M, Adamson P, et al. A position statement on mpox as a sexually transmitted disease [published online December 22, 2022]. Clin Infect Dis. doi:10.1093/cid/ciac960

- Cabanillas B, Murdaca G, Guemari A, et al. A compilation answering 50 questions on monkeypox virus and the current monkeypox outbreak. Allergy. 2023;78:639-662. doi:10.1111/all.15633

- Tarín-Vicente EJ, Alemany A, Agud-Dios M, et al. Clinical presentation and virological assessment of confirmed human monkeypox virus cases in Spain: a prospective observational cohort study [published online August 8, 2022]. Lancet. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01436-2

- Seang S, Burrel S, Todesco E, et al. Evidence of human-to-dog transmission of monkeypox virus. Lancet. 2022;400:658-659. doi:10.1016 /s0140-6736(22)01487-8

- Ramdass P, Mullick S, Farber HF. Viral skin diseases. Prim Care. 2015;42:517-67. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2015.08.006

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mpox: Clinical Recognition. Updated August 23, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cdc .gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/clinicians/clinical-recognition.html

- Mpox Cases by Age and Gender, Race/Ethnicity, and Symptoms. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated March 15, 2023. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox /response/2022/demographics.html

- Kawsar A, Hussain K, Roberts N. The return of monkeypox: key pointers for dermatologists [published online July 29, 2022]. Clin Exp Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ced.15357

- Khanna U, Bishnoi A, Vinay K. Current outbreak of monkeypox— essentials for the dermatologist [published online June 23, 2022]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.1170

- Fox T, Gould S, Princy N, et al. Therapeutics for treating mpox in humans. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;3:CD015769. doi:10.1002/14651858 .CD015769

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Treatment information for healthcare professionals. Updated March 3, 2023. Accessed March 24, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/clinicians /treatment.html#anchor_1666886364947

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidance for tecovirimat use. Updated February 23, 2023. Accessed March 24, 2023. https://www .cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/clinicians/Tecovirimat.html

- Interim Clinical Considerations for Use of JYNNEOS and ACAM2000 Vaccines During the 2022 U.S. Monkeypox Outbreak. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated October 19, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/health-departments/vaccine-considerations.html

- Key Facts About Vaccines to Prevent Monkeypox Disease. US Food and Drug Administration. Updated August 18, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/vaccines/key-facts-aboutvaccines-prevent-monkeypox-disease

- Smallpox: Vaccines. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated August 8, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/clinicians/vaccines.html

- ACAM2000. Package insert. Emergent Product Development Gaithersburg Inc; 2019.

- Cices A, Prasad S, Akselrad M, et al. Mpox update: clinical presentation, vaccination guidance, and management. Cutis. 2023;111:197-202. doi:10.12788/cutis.0745

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mpox: 2022 Outbreak Cases and Data. Updated March 15, 2023. Accessed March 121, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/response/2022/

- Srivastava G. Human monkeypox disease [published online August 10, 2022]. Clin Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2022.08.009

- Bryer J, Freeman EE, Rosenbach M. Monkeypox emerges on a global scale: a historical review and dermatologic primer [published online July 8, 2022]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.07.007

- Americo JL, Earl PL, Moss B. Virulence differences of mpox (monkeypox) virus clades I, IIa, and IIb.1 in a small animal model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120:E2220415120. doi:10.1073 /pnas.2220415120

- Guarner J, Del Rio C, Malani PN. Monkeypox in 2022—what clinicians need to know. JAMA. 2022;328:139-140. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.10802

- Looi MK. Monkeypox: what we know about the 2022 outbreak so far [published online August 23, 2022]. BMJ. doi:10.1136/bmj.o2058

- Allan-Blitz LT, Gandhi M, Adamson P, et al. A position statement on mpox as a sexually transmitted disease [published online December 22, 2022]. Clin Infect Dis. doi:10.1093/cid/ciac960

- Cabanillas B, Murdaca G, Guemari A, et al. A compilation answering 50 questions on monkeypox virus and the current monkeypox outbreak. Allergy. 2023;78:639-662. doi:10.1111/all.15633

- Tarín-Vicente EJ, Alemany A, Agud-Dios M, et al. Clinical presentation and virological assessment of confirmed human monkeypox virus cases in Spain: a prospective observational cohort study [published online August 8, 2022]. Lancet. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01436-2

- Seang S, Burrel S, Todesco E, et al. Evidence of human-to-dog transmission of monkeypox virus. Lancet. 2022;400:658-659. doi:10.1016 /s0140-6736(22)01487-8

- Ramdass P, Mullick S, Farber HF. Viral skin diseases. Prim Care. 2015;42:517-67. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2015.08.006

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mpox: Clinical Recognition. Updated August 23, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cdc .gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/clinicians/clinical-recognition.html

- Mpox Cases by Age and Gender, Race/Ethnicity, and Symptoms. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated March 15, 2023. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox /response/2022/demographics.html

- Kawsar A, Hussain K, Roberts N. The return of monkeypox: key pointers for dermatologists [published online July 29, 2022]. Clin Exp Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ced.15357

- Khanna U, Bishnoi A, Vinay K. Current outbreak of monkeypox— essentials for the dermatologist [published online June 23, 2022]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.1170

- Fox T, Gould S, Princy N, et al. Therapeutics for treating mpox in humans. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;3:CD015769. doi:10.1002/14651858 .CD015769

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Treatment information for healthcare professionals. Updated March 3, 2023. Accessed March 24, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/clinicians /treatment.html#anchor_1666886364947

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidance for tecovirimat use. Updated February 23, 2023. Accessed March 24, 2023. https://www .cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/clinicians/Tecovirimat.html

- Interim Clinical Considerations for Use of JYNNEOS and ACAM2000 Vaccines During the 2022 U.S. Monkeypox Outbreak. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated October 19, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/health-departments/vaccine-considerations.html

- Key Facts About Vaccines to Prevent Monkeypox Disease. US Food and Drug Administration. Updated August 18, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/vaccines/key-facts-aboutvaccines-prevent-monkeypox-disease

- Smallpox: Vaccines. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated August 8, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/clinicians/vaccines.html

- ACAM2000. Package insert. Emergent Product Development Gaithersburg Inc; 2019.

- Cices A, Prasad S, Akselrad M, et al. Mpox update: clinical presentation, vaccination guidance, and management. Cutis. 2023;111:197-202. doi:10.12788/cutis.0745

Lip Reconstruction After Mohs Micrographic Surgery: A Guide on Flaps

The lip is commonly affected by skin cancer because of increased sun exposure and actinic damage, with basal cell carcinoma typically occurring on the upper lip and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) on the lower lip. The risk for metastatic spread of SCC on the lip is higher than cutaneous SCC on other facial locations but lower than SCC of the oral mucosa.1,2 If the tumor is operable and the patient has no contraindications to surgery, Mohs micrographic surgery is the preferred treatment, as it allows for maximal healthy tissue preservation and has the lowest recurrence rates.1-3 Once the tumor is removed and margins are confirmed to be negative, one must consider the options for defect closure, including healing by secondary intention, primary/direct closure, full-thickness skin grafts, local flaps, or free flaps.4 Secondary intention may lead to wound contracture and suboptimal functional and cosmetic outcomes. Primary wedge closure can be utilized for optimal functional and cosmetic outcomes when the defect involves less than one-third of the horizontal width of the vermilion. For larger defects, the surgeon must consider a flap or graft. Skin grafts are less favorable than local flaps because they may have different skin color, texture, and hair-bearing properties than the recipient area.3,5 In addition, grafts require a separate donor site, which means more pain, recovery time, and risk for complications for the patient.3 Free flaps similarly utilize tissue and blood supply from a donor site to repair major tissue loss. Radial forearm free flaps commonly are used for large lip defects but are more extensive, risky, and costly compared to local flaps for smaller defects under local anesthesia or nerve blocks.6,7 With these considerations, a local lip flap often is the most ideal repair method.

When performing a local lip flap, it is important to consider the functional and aesthetic aspects of the lips. The lower face is more susceptible to distortion and wound contraction after defect repair because it lacks a substantial supportive fibrous network. The dynamics of opposing lip elevator and depressor muscles make the lips a visual focal point and a crucial structure for facial expression, mastication, oral continence, speech phonation, and mouth opening and closing.2,4,8,9 Aesthetics and symmetry of the lips also are a large part of facial recognition and self-image.9

Lip defects are classified as partial thickness involving skin and muscle or full thickness involving skin, muscle, and mucosa. Partial-thickness wounds less than one-third the width of the horizontal lip can be repaired with a primary wedge resection or left to heal by secondary intention if the defect only involves the superficial vermilion.2 For defects larger than one-third the width of the horizontal lip, local flaps are favored to allow for closely matched skin and lip mucosa to fill in the defect.9 Full-thickness defects are further classified based on defect width compared to total lip width (ie, less than one-third, between one-third and two-thirds, and greater than two-thirds) as well as location (ie, medial, lateral, upper lip, lower lip).2,10

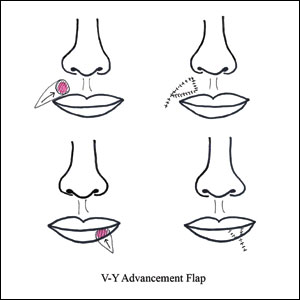

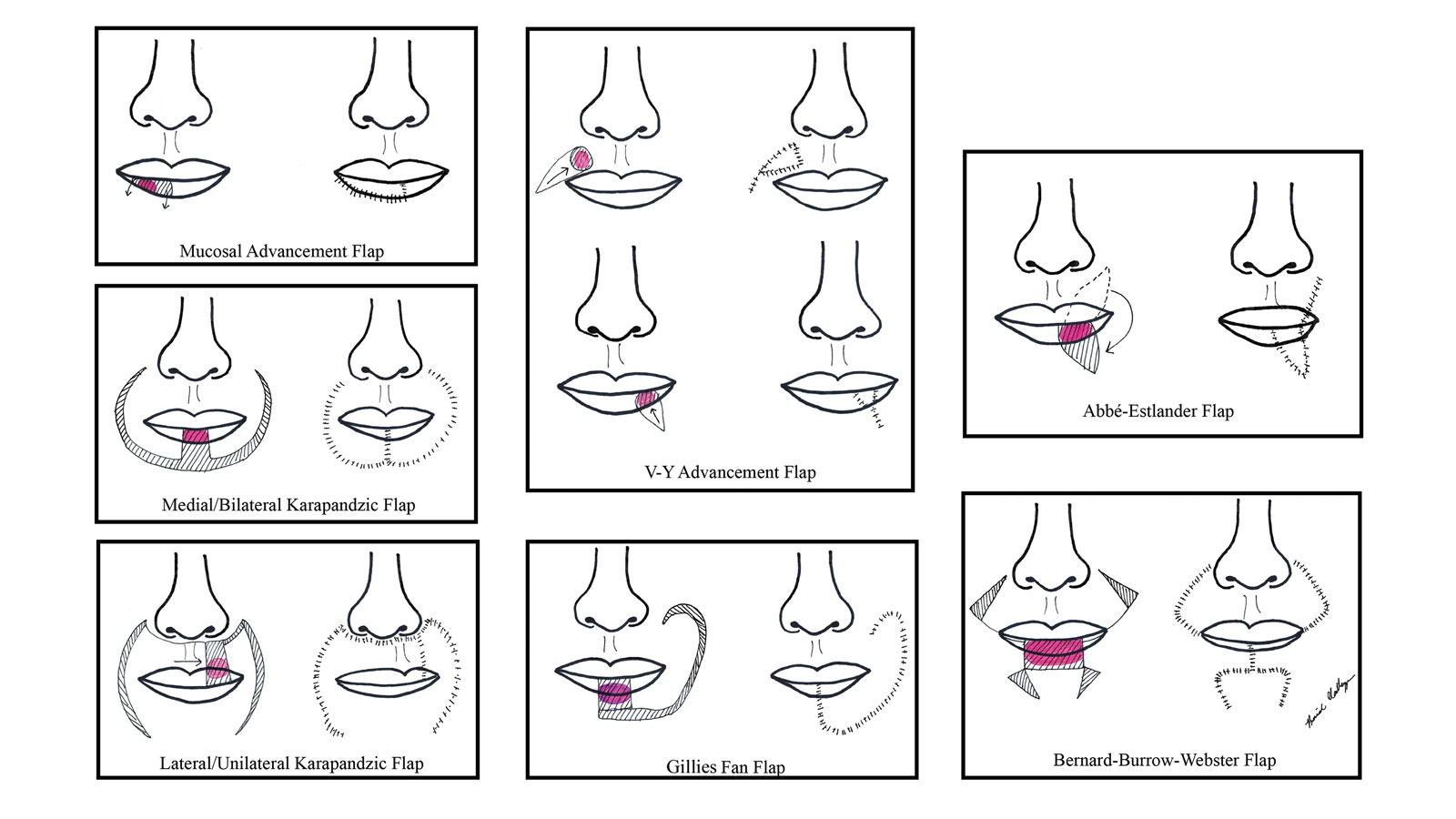

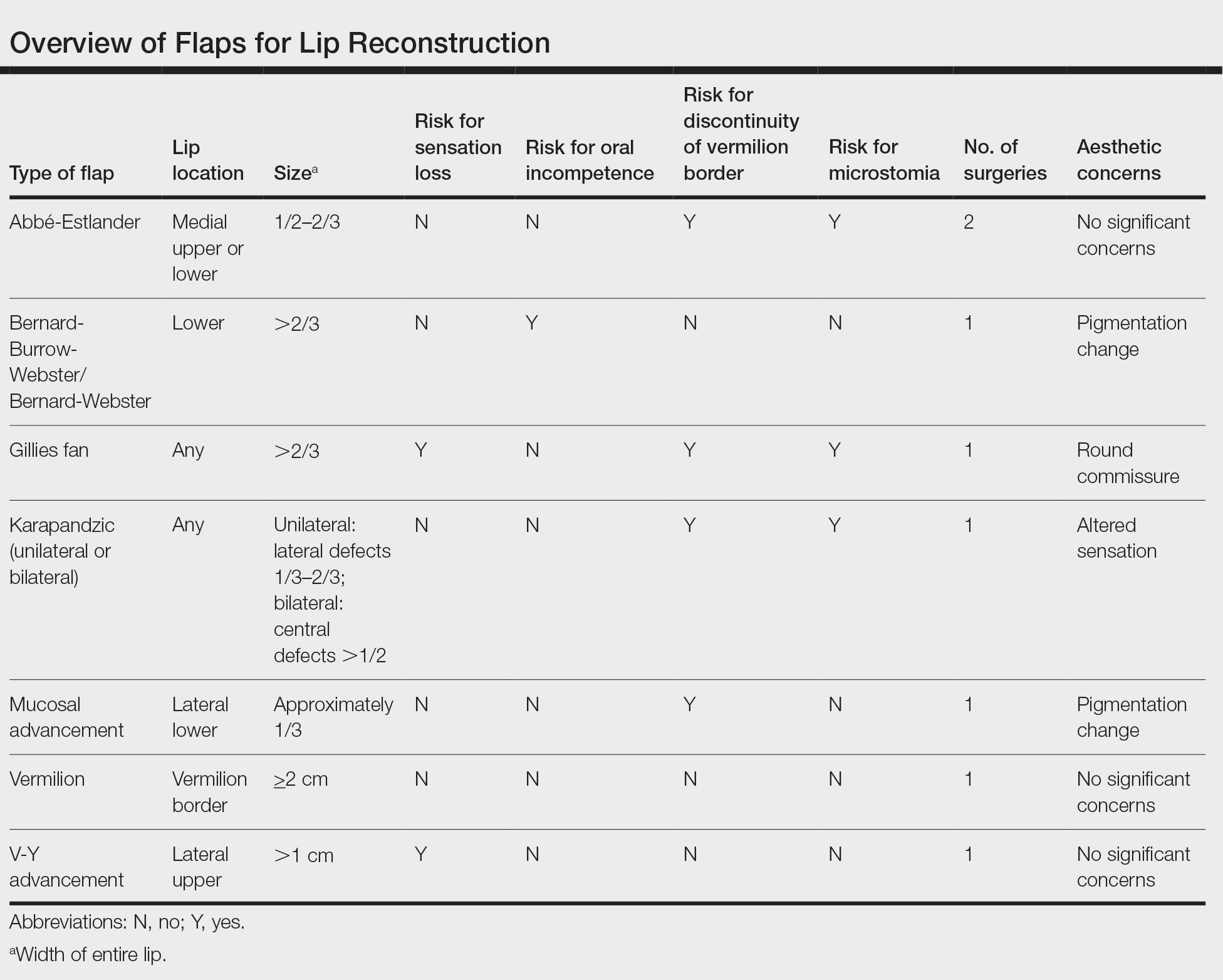

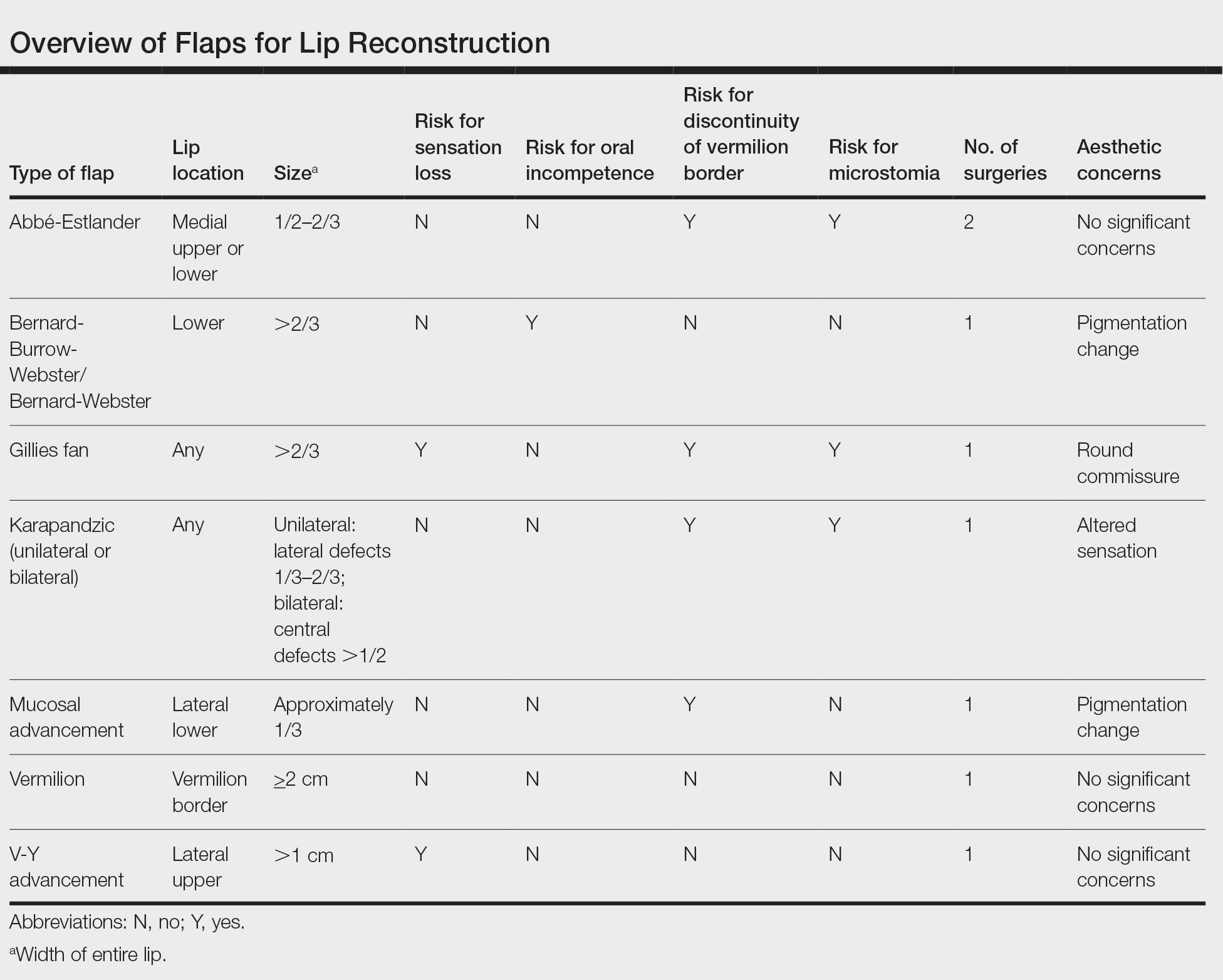

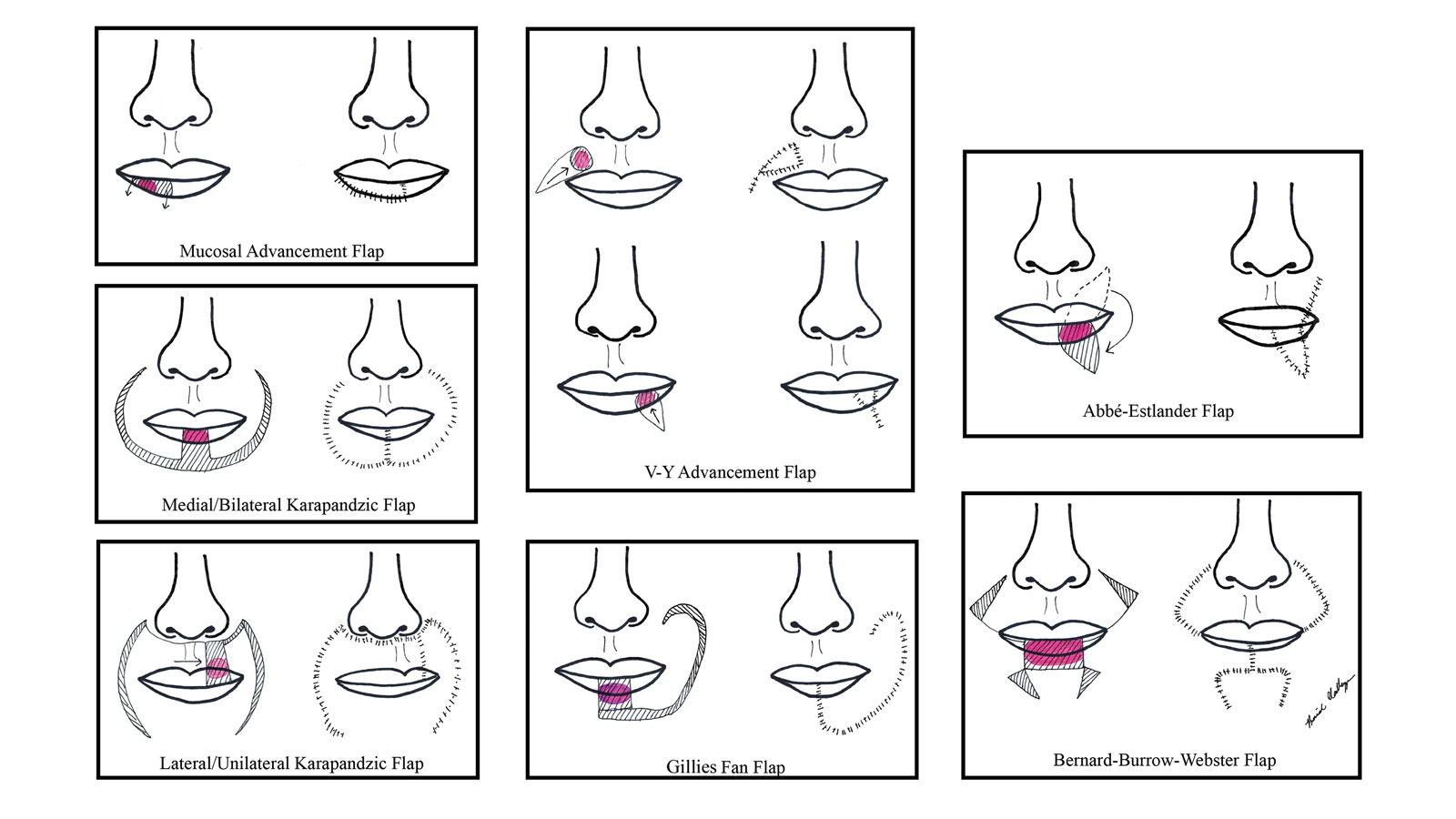

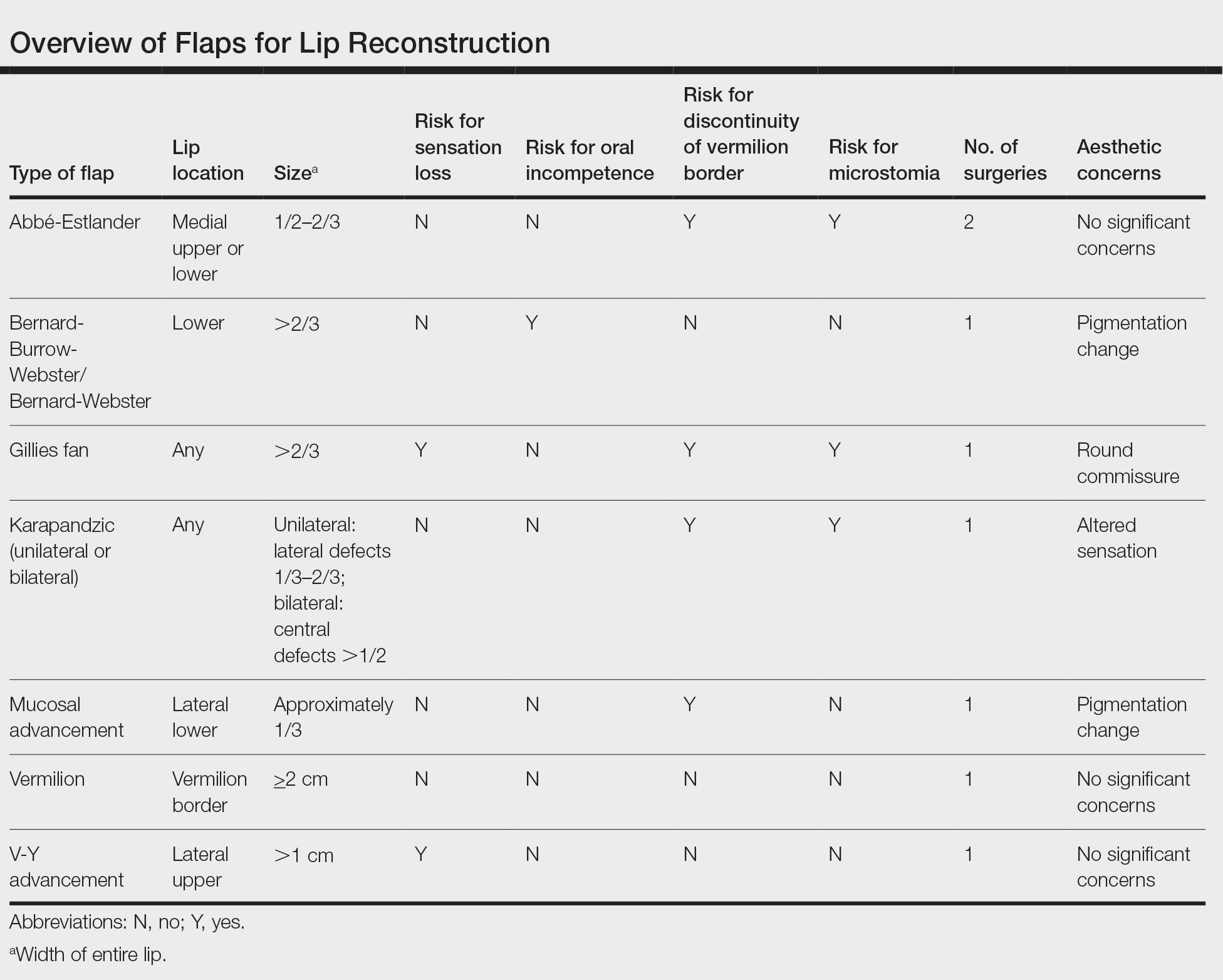

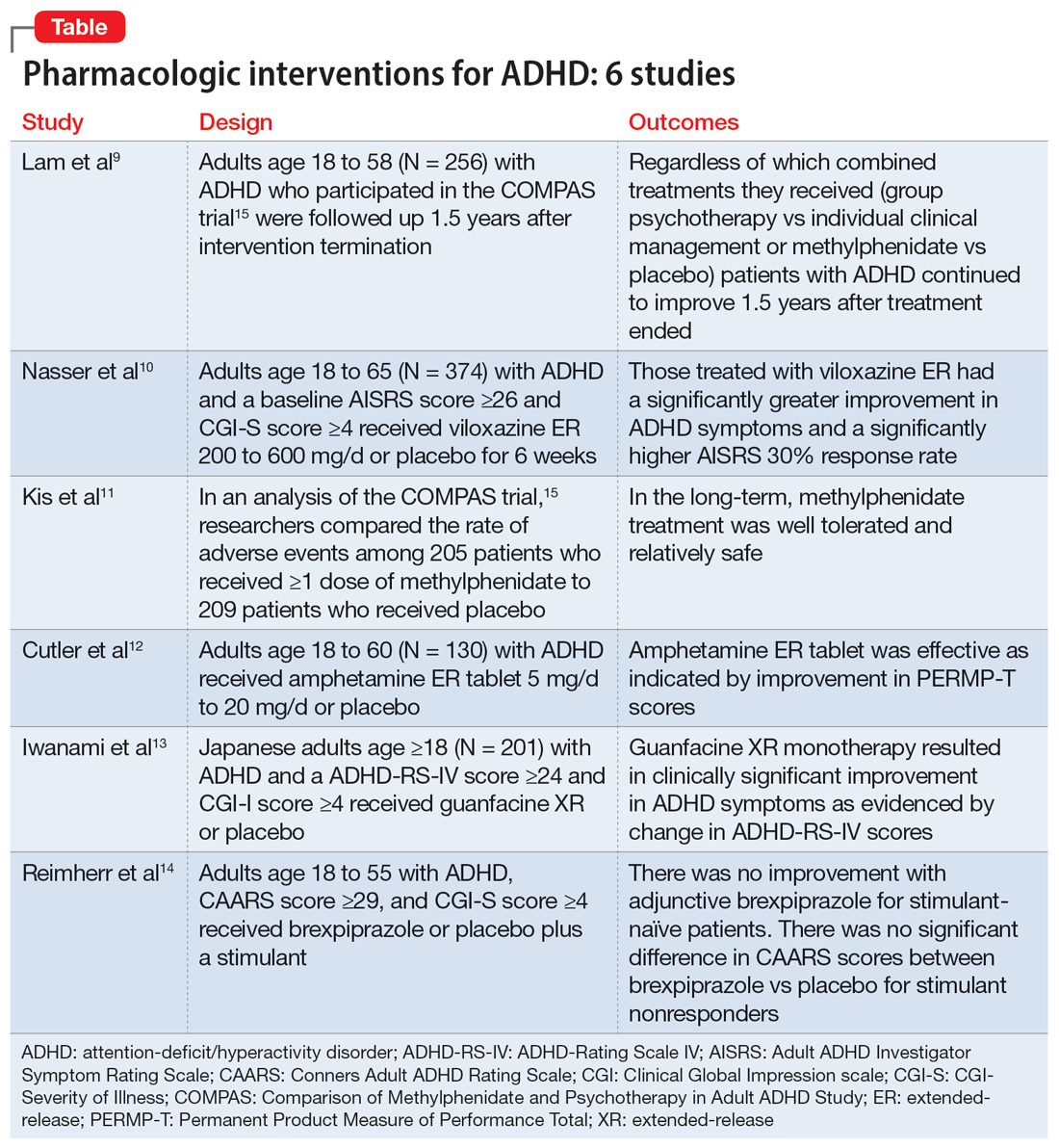

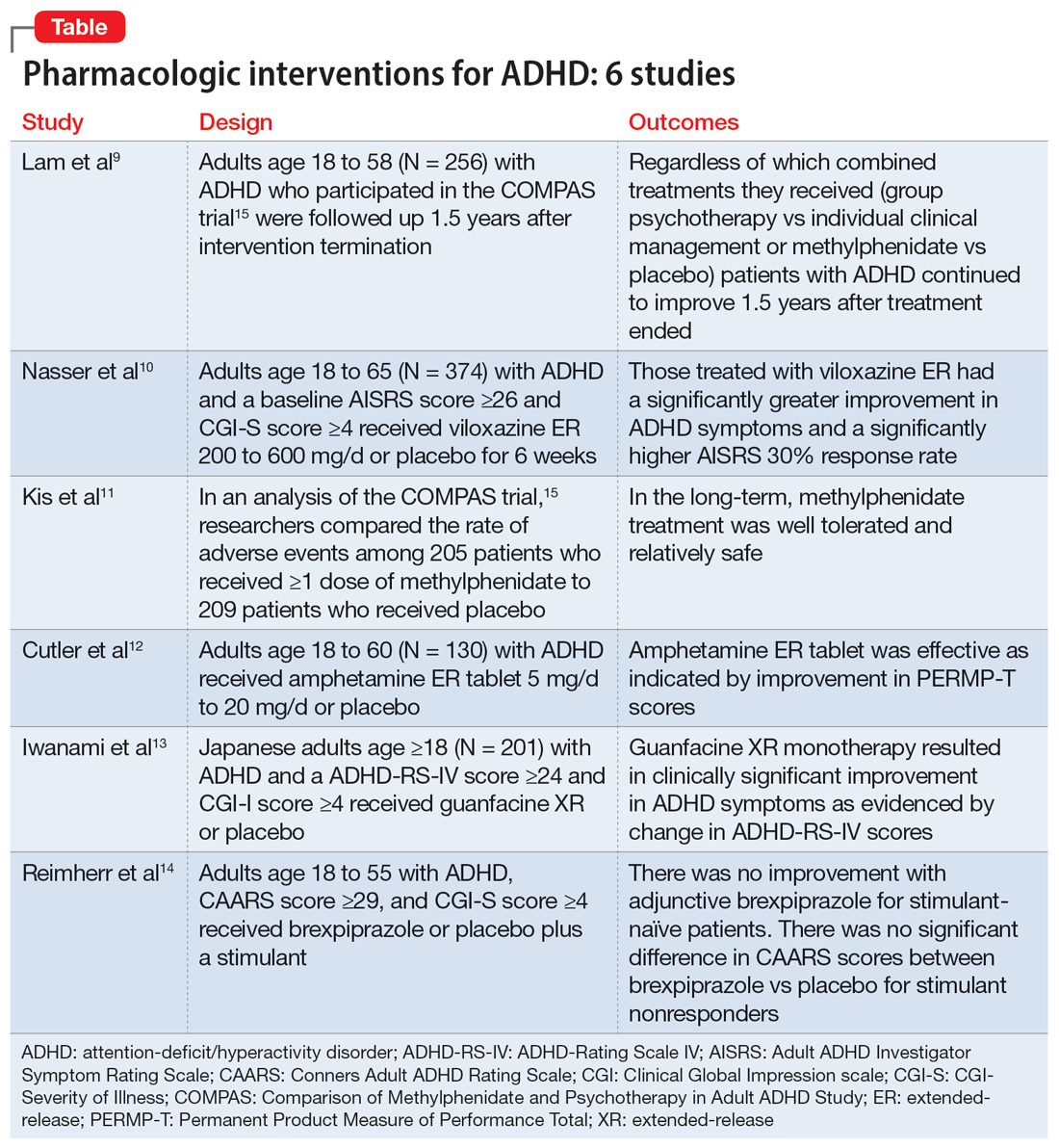

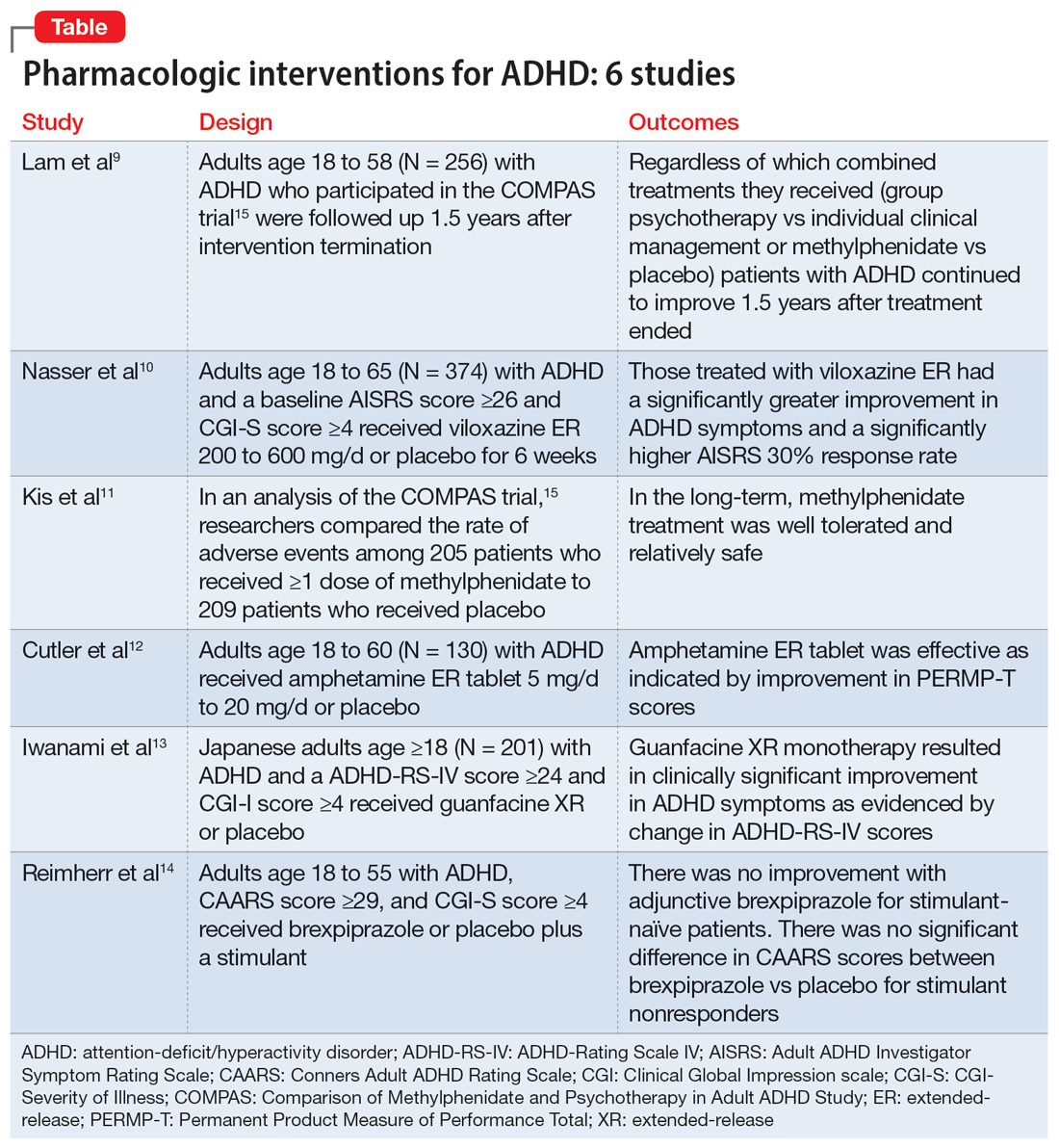

There are several local lip flap reconstruction options available, and choosing one is based on defect size and location. We provide a succinct review of the indications, risks, and benefits of commonly utilized flaps (Table), as well as artist renderings of all of the flaps (Figure).

Vermilion Flaps

Vermilion flaps are used to close partial-thickness defects of the vermilion border, an area that poses unique obstacles of repair with blending distant tissues to match the surroundings.8 Goldstein11 developed an adjacent ipsilateral vermilion flap utilizing an arterialized myocutaneous flap for reconstruction of vermilion defects. Later, this technique was modified by Sawada et al12 into a bilateral adjacent advancement flap for closure of central vermilion defects and may be preferred for defects 2 cm in size or larger. Bilateral flaps are smaller and therefore more viable than unilateral or larger flaps, allowing for a more aesthetic alignment of the vermilion border and preservation of muscle activity because muscle fibers are not cut. This technique also allows for more efficient stretching or medial advancement of the tissue while generating less tension on the distal flap portions. Burow triangles can be utilized if necessary for improved aesthetic outcome.1

Mucosal Advancement and Split Myomucosal Advancement Flap

The mucosal advancement technique can be considered for tumors that do not involve the adjacent cutaneous skin or the orbicularis oris muscle; thus, the reconstruction involves only the superficial vermilion area.7,13 Mucosal incisions are made at the gingivobuccal sulcus, and the mucosal flap is elevated off the orbicularis oris muscle and advanced into the defect.10 A plane of dissection is maintained while preserving the labial artery. Undermining effectively advances wet mucosa into the dry mucosal lip to create a neovermilion. However, the reconstructed lip often appears thinner and will possibly be a different shade compared to the adjacent native lip. These discrepancies become more evident with deeper defects.7

There is a risk for cosmetic distortion and scar contraction with advancing the entire mucosa. Eirís et al13 described a solution—a bilateral mucosal rotation flap in which the primary incision is made along the entire vermilion border and tissue is undermined to allow advancement of the mucosa. Because the wound closure tension lays across the entire lip, there is less risk for scar contraction, even if the flap movement is unequal on either side of the defect.13

Although mucosal advancement flaps are a classic choice for reconstruction following a vermilion defect, other techniques, such as primary closure, should be considered in elderly patients and patients taking anticoagulants because of the risks for flap necrosis, swelling, bruising, hematoma, and dysesthesia, as well as a decrease in the anterior-posterior dimension of the lip. These risks can be attributed to trauma of surrounding tissue and stress secondary to longer overall operating times.14

Split myomucosal advancement flaps are used in similar scenarios as myomucosal advancement flaps but for larger red lip defects that are less than 50% the length of the upper or lower lip. Split myomucosal advancement flaps utilize an axial flap based on the labial artery, which provides robust vascular supply to the reconstructed area. This vascularity, along with lateral motor innervation of the orbicularis oris, allows for split myomucosal advancement flaps to restore the resected volume, preserve lip function, and minimize postoperative microstomia.7

V-Y Advancement Flaps

V-Y advancement flaps are based on a subcutaneous tissue pedicle and are optimal for partial- and full-thickness defects larger than 1 cm on the lateral upper lips, whereas bilateral V-Y advancement flaps are recommended for central lip defects.15-17 Advantages of V-Y advancement flaps are preserved facial symmetry and maintenance of the oral sphincter and facial nerve function. The undermining portions allow for advancement of a skin flap of similar thickness and contour into the upper or lower lip.15 Disadvantages include facial asymmetry with larger defects involving the melolabial fold as well as paresthesia after closure. However, in one study, no paresthesia was reported more than 12 months postprocedure.4 The biggest disadvantage of the V-Y advancement flap is the kite-shaped scar and possible trapdoor deformity.5,15 When working medially, the addition of the pincer modification helps avoid blunting of the philtrum and recreates a Cupid’s bow by curling the lateral flap edges medially to resemble a teardrop shape.17 V-Y advancement flaps for defects of skin and adipose tissue less than 5 mm in size have the highest need for revision surgery; thus, defects of this small size should be repaired primarily.4

When using a V-Y advancement flap to correct large defects, there are 3 common complications that may arise: fullness medial to the commissure, a depressed vermilion lip, and a standing cutaneous deformity along the trailing edge of the flap where the Y is formed upon closure of the donor site. To decrease the fullness, a skin excision from the inferior border of the flap along the vermiliocutaneous border can be made to debulk the area. A vermilion advancement can be used to optimize the vermiliocutaneous junction. Potential standing cutaneous deformity is addressed by excising a small ellipse of skin oriented along the axis of the relaxed skin tension lines.15

Abbé-Estlander Flap

The Abbé-Estlander flap (also known as a transoral cross-lip flap) is a full-thickness myocutaneous interpolation flap with blood supply from the labial artery. It is used for lower lip tumors that have deep invasion into muscle and are 30% to 60% of the horizontal lip.8,9 Abbé transposition flaps are used for defects medial to the oral commissure and are best suited for philtrum reconstruction, whereas Estlander flaps are for defects that involve the oral commissure.9,18 Interpolation flaps usually are performed in 2 stages, but some dermatologic surgeons have reported success with single-stage procedures.1 The second-stage division usually is performed 2 to 3 weeks after flap insetting to allow time for neovascularization, which is crucial for pedicle survival.8,9,19

Advantages of this type of flap are the preservation of orbicularis oris strength and a functional and aesthetic result with minimal change in appearance for defects sized from one-third to two-thirds the width of the lip.20 This aesthetic effect is particularly notable when the donor flap is taken from the mediolateral upper lip, allowing the scarred area to blend into the nasolabial fold.8 Disadvantages of this flap are a risk for microstomia, lip vermilion misalignment, and lip adhesion.21 It is important that patients are educated on the need for multiple surgeries when using this type of flap, as patients favor single-step procedures.1 The Abbé flap requires 2 surgeries, whereas the Estlander flap requires only 1. However, patients commonly require commissuroplasty with the Estlander flap alone.21

Gillies Fan Flap, Karapandzic Flap, Bernard-Webster Flap, and Bernard-Burrow-Webster Flap

The Gillies fan flap, Karapandzic flap, Bernard-Webster (BW) flap, and modified Bernard-Burrow-Webster flap are the likely choices for repair of lip defects that encompass more than two-thirds of the lip.9,10,22 The Karapandzic and BW flaps are the 2 most frequently used for reconstruction of larger lower lip defects and only require 1 surgery.

Upper lip full-thickness defects that are too big for an Abbé-Estlander flap are closed with the Gillies fan flap.18 These defects involve 70% to 80% of the horizontal lip.9 The Gillies fan flap design redistributes the remaining lip to provide similar tissue quality and texture to fill the large defects.9,23 Compared to Karapandzic and Bernard flaps, Gillies fan incision closures are hidden well in the nasolabial folds, and the degree of microstomy is decreased because of the rotation of the flaps. However, rotation of medial cheek flaps can distort the orbicular muscular fibers and the anatomy of the commissure, which may require repair with commissurotomy. Drawbacks include a risk for denervation that can result in temporary oral sphincter incompetence.23 The bilateral Gillies fan flap carries a risk for microstomy as well as misalignment of the lip vermilion and round commissures.21

The Karapandzic flap is similar to the Gillies fan flap but only involves the skin and mucosa.9 This flap can be used for lateral or medial upper lip defects greater than one-third the width of the entire lip. This single-procedure flap allows for labial continuity, preserved sensation, and motor function; however, microstomia and misalignment of the oral commissure are common.1,18,21 In a retrospective study by Nicholas et al,4 the only flap reported to have a poor functional outcome was the Karapandzic flap, with 3 patients reporting altered sensation and 1 patient reporting persistent stiffness while smiling.

The BW flap can be applied for extensive full-thickness defects greater than one-third the lower lip and for defects with limited residual lip. This flap also can be used in cases where only skin is excised, as the flap does not depend on reminiscent lip tissue for reconstruction of the new lower lip. Sensory function is maintained given adequate visualization and preservation of the local vascular, nervous, and muscular systems. Disadvantages of the BW flap include an incision notch in the region of the lower lip; blunting of the alveolobuccal sulcus; and functional deficits, such as lip incontinence to liquids during the postoperative period.21

The Bernard-Burrow-Webster flap is used for large lower lip defects and preserves the oral commissures by advancing adjacent cheek tissue and remaining lip tissue medially.10 It allows for larger site mobilization, but it is possible to see some resulting oral incontinence.1,10 The Burow wedge flap is a variant of the advancement flap, with the Burow triangle located lateral to the oral commissure. Caution must be taken to avoid intraoperative bleeding from the labial and angular arteries. In addition, there also may be downward displacement of the vermilion border.5

How to Choose a Flap

The orbicularis oris is a circular muscle that surrounds both the upper and lower lips. It is pulled into an oval, allowing for sphincter function by radially oriented muscles, all of which are innervated by the facial nerve. Other key anatomical structures of the lips include the tubercle (vermilion prominence), Cupid’s bow and philtrum, nasolabial folds, white roll, hair-bearing area, and vermilion border. The lips are divided into cutaneous, mucosal, and vermilion parts, with the vermilion area divided into dry/external and wet/internal areas. Sensation to the upper lip is provided by the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve via the infraorbital nerve. The lower lip is innervated by the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve via the inferior alveolar nerve. The labial artery, a branch of the facial artery, is responsible for blood supply to the lips.3,9 Because of the complex anatomy of the lips, careful reconstruction is crucial for functional and aesthetic preservation.

There are a variety of lip defect repairs, but all local flaps aim to preserve aesthetics and function. The Table summarizes the key risks and benefits of each flap. Local flap techniques can be used in combination for more complex defects.3 For example, Nadiminti et al19 described the combination of the Abbé flap and V-Y advancement flap to restore function and create a new symmetric nasolabial fold. Dermatologic surgeons will determine the most suitable technique based on tumor location, tumor stage or depth of invasion (partial or full thickness), and preservation of function and aesthetics.1

Other factors to consider when choosing a local flap are the patient’s age, tissue laxity, dentition/need for dentures, and any prior treatments.7 Scar revision surgery may be needed after reconstruction, especially with longer vertical scars in areas without other rhytides. In addition, paresthesia is common after Mohs micrographic surgery of the face; however, new neural networks are created postoperatively, and most paresthesia resolves within 1 year of the repair.4 Dermabrasion and Z-plasty also may be considered, as they have been shown to be successful in improving final outcomes.9 Overall, local flaps have risks for infection, flap necrosis, and bleeding, though the incidence is low in reconstructions of the face.

Final Thoughts

There are several mechanisms to repair upper and lower lip defects resulting from surgical removal of cutaneous cancers. This review of specific flaps used in lip reconstruction provides a comprehensive overview of indications, advantages, and disadvantages of available lip flaps.

- Goldman A, Wollina U, França K, et al. Lip repair after Mohs surgery for squamous cell carcinoma by bilateral tissue expanding vermillion myocutaneous flap (Goldstein technique modified by Sawada). Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018;6:93-95.

- Faulhaber J, Géraud C, Goerdt S, et al. Functional and aesthetic reconstruction of full-thickness defects of the lower lip after tumor resection: analysis of 59 cases and discussion of a surgical approach. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:859-867.

- Skaria AM. The transposition advancement flap for repair of postsurgical defects on the upper lip. Dermatology. 2011;223:203-206.

- Nicholas MN, Liu A, Chan AR, et al. Postoperative outcomes of local skin flaps used in oncologic reconstructive surgery of the upper cutaneous lip: a systematic review. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1047-1051.

- Wu W, Ibrahimi OA, Eisen DB. Cheek advancement flap with retained standing cone for reconstruction of a defect involving the upper lip, nasal sill, alar insertion, and medial cheek. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:1077-1082.

- Cook JL. The reconstruction of two large full-thickness wounds of the upper lip with different operative techniques: when possible, a local flap repair is preferable to reconstruction with free tissue transfer. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:281-289.

- Glenn CJ, Adelson RT, Flowers FP. Split myomucosal advancement flap for reconstruction of a lower lip defect. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:1725-1728.

- Hahn HJ, Kim HJ, Choi JY, et al. Transoral cross-lip (Abbé-Estlander) flap as a viable and effective reconstructive option in middle lower lip defect reconstruction. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:210-214.

- Larrabee YC, Moyer JS. Reconstruction of Mohs defects of the lips and chin. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2017;25:427-442.

- Campos MA, Varela P, Marques C. Near-total lower lip reconstruction: combined Karapandzic and Bernard-Burrow-Webster flap. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2017;26:19-20.

- Goldstein MH. A tissue-expanding vermillion myocutaneous flap for lip repair. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;73:768–770.

- Sawada Y, Ara M, Nomura K. Bilateral vermilion flap—a modification of Goldstein’s technique. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;17:257–259.

- Eirís N, Suarez-Valladares MJ, Cocunubo Blanco HA, et al. Bilateral mucosal rotation flap for repair of lower lip defect. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:E81-E82.

- Sand M, Altmeyer P, Bechara FG. Mucosal advancement flap versus primary closure after vermilionectomy of the lower lip. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1987-1992.

- Griffin GR, Weber S, Baker SR. Outcomes following V-Y advancement flap reconstruction of large upper lip defects. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2012;14:193-197.

- Zhang WC, Liu Z, Zeng A, et al. Repair of cutaneous and mucosal upper lip defects using double V-Y advancement flaps. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:211-217.

- Tolkachjov SN. Bilateral V-Y advancement flaps with pincer modification for re-creation of large philtrum lip defect. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:E187-E188.

- García de Marcos JA, Heras Rincón I, González Córcoles C, et al. Bilateral reverse Yu flap for upper lip reconstruction after oncologic resection. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:193-196.

- Nadiminti H, Carucci JA. Repair of a through-and-through defect on the upper cutaneous lip. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:58-61.

- Kumar A, Shetty PM, Bhambar RS, et al. Versatility of Abbe-Estlander flap in lip reconstruction—a prospective clinical study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:NC18-NC21.

- Denadai R, Raposo-Amaral CE, Buzzo CL, et al. Functional lower lip reconstruction with the modified Bernard-Webster flap. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2015;68:1522-1528.

- Salgarelli AC, Bellini P, Magnoni C, et al. Synergistic use of local flaps for total lower lip reconstruction. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1666-1670.

- Moreno-Ramirez D, Ferrandiz L, Vasquez-Chinchay F, et al. Uncompleted fan flap for full-thickness lower lip defect. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1426-1429.

The lip is commonly affected by skin cancer because of increased sun exposure and actinic damage, with basal cell carcinoma typically occurring on the upper lip and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) on the lower lip. The risk for metastatic spread of SCC on the lip is higher than cutaneous SCC on other facial locations but lower than SCC of the oral mucosa.1,2 If the tumor is operable and the patient has no contraindications to surgery, Mohs micrographic surgery is the preferred treatment, as it allows for maximal healthy tissue preservation and has the lowest recurrence rates.1-3 Once the tumor is removed and margins are confirmed to be negative, one must consider the options for defect closure, including healing by secondary intention, primary/direct closure, full-thickness skin grafts, local flaps, or free flaps.4 Secondary intention may lead to wound contracture and suboptimal functional and cosmetic outcomes. Primary wedge closure can be utilized for optimal functional and cosmetic outcomes when the defect involves less than one-third of the horizontal width of the vermilion. For larger defects, the surgeon must consider a flap or graft. Skin grafts are less favorable than local flaps because they may have different skin color, texture, and hair-bearing properties than the recipient area.3,5 In addition, grafts require a separate donor site, which means more pain, recovery time, and risk for complications for the patient.3 Free flaps similarly utilize tissue and blood supply from a donor site to repair major tissue loss. Radial forearm free flaps commonly are used for large lip defects but are more extensive, risky, and costly compared to local flaps for smaller defects under local anesthesia or nerve blocks.6,7 With these considerations, a local lip flap often is the most ideal repair method.

When performing a local lip flap, it is important to consider the functional and aesthetic aspects of the lips. The lower face is more susceptible to distortion and wound contraction after defect repair because it lacks a substantial supportive fibrous network. The dynamics of opposing lip elevator and depressor muscles make the lips a visual focal point and a crucial structure for facial expression, mastication, oral continence, speech phonation, and mouth opening and closing.2,4,8,9 Aesthetics and symmetry of the lips also are a large part of facial recognition and self-image.9

Lip defects are classified as partial thickness involving skin and muscle or full thickness involving skin, muscle, and mucosa. Partial-thickness wounds less than one-third the width of the horizontal lip can be repaired with a primary wedge resection or left to heal by secondary intention if the defect only involves the superficial vermilion.2 For defects larger than one-third the width of the horizontal lip, local flaps are favored to allow for closely matched skin and lip mucosa to fill in the defect.9 Full-thickness defects are further classified based on defect width compared to total lip width (ie, less than one-third, between one-third and two-thirds, and greater than two-thirds) as well as location (ie, medial, lateral, upper lip, lower lip).2,10

There are several local lip flap reconstruction options available, and choosing one is based on defect size and location. We provide a succinct review of the indications, risks, and benefits of commonly utilized flaps (Table), as well as artist renderings of all of the flaps (Figure).

Vermilion Flaps

Vermilion flaps are used to close partial-thickness defects of the vermilion border, an area that poses unique obstacles of repair with blending distant tissues to match the surroundings.8 Goldstein11 developed an adjacent ipsilateral vermilion flap utilizing an arterialized myocutaneous flap for reconstruction of vermilion defects. Later, this technique was modified by Sawada et al12 into a bilateral adjacent advancement flap for closure of central vermilion defects and may be preferred for defects 2 cm in size or larger. Bilateral flaps are smaller and therefore more viable than unilateral or larger flaps, allowing for a more aesthetic alignment of the vermilion border and preservation of muscle activity because muscle fibers are not cut. This technique also allows for more efficient stretching or medial advancement of the tissue while generating less tension on the distal flap portions. Burow triangles can be utilized if necessary for improved aesthetic outcome.1

Mucosal Advancement and Split Myomucosal Advancement Flap

The mucosal advancement technique can be considered for tumors that do not involve the adjacent cutaneous skin or the orbicularis oris muscle; thus, the reconstruction involves only the superficial vermilion area.7,13 Mucosal incisions are made at the gingivobuccal sulcus, and the mucosal flap is elevated off the orbicularis oris muscle and advanced into the defect.10 A plane of dissection is maintained while preserving the labial artery. Undermining effectively advances wet mucosa into the dry mucosal lip to create a neovermilion. However, the reconstructed lip often appears thinner and will possibly be a different shade compared to the adjacent native lip. These discrepancies become more evident with deeper defects.7

There is a risk for cosmetic distortion and scar contraction with advancing the entire mucosa. Eirís et al13 described a solution—a bilateral mucosal rotation flap in which the primary incision is made along the entire vermilion border and tissue is undermined to allow advancement of the mucosa. Because the wound closure tension lays across the entire lip, there is less risk for scar contraction, even if the flap movement is unequal on either side of the defect.13

Although mucosal advancement flaps are a classic choice for reconstruction following a vermilion defect, other techniques, such as primary closure, should be considered in elderly patients and patients taking anticoagulants because of the risks for flap necrosis, swelling, bruising, hematoma, and dysesthesia, as well as a decrease in the anterior-posterior dimension of the lip. These risks can be attributed to trauma of surrounding tissue and stress secondary to longer overall operating times.14

Split myomucosal advancement flaps are used in similar scenarios as myomucosal advancement flaps but for larger red lip defects that are less than 50% the length of the upper or lower lip. Split myomucosal advancement flaps utilize an axial flap based on the labial artery, which provides robust vascular supply to the reconstructed area. This vascularity, along with lateral motor innervation of the orbicularis oris, allows for split myomucosal advancement flaps to restore the resected volume, preserve lip function, and minimize postoperative microstomia.7

V-Y Advancement Flaps

V-Y advancement flaps are based on a subcutaneous tissue pedicle and are optimal for partial- and full-thickness defects larger than 1 cm on the lateral upper lips, whereas bilateral V-Y advancement flaps are recommended for central lip defects.15-17 Advantages of V-Y advancement flaps are preserved facial symmetry and maintenance of the oral sphincter and facial nerve function. The undermining portions allow for advancement of a skin flap of similar thickness and contour into the upper or lower lip.15 Disadvantages include facial asymmetry with larger defects involving the melolabial fold as well as paresthesia after closure. However, in one study, no paresthesia was reported more than 12 months postprocedure.4 The biggest disadvantage of the V-Y advancement flap is the kite-shaped scar and possible trapdoor deformity.5,15 When working medially, the addition of the pincer modification helps avoid blunting of the philtrum and recreates a Cupid’s bow by curling the lateral flap edges medially to resemble a teardrop shape.17 V-Y advancement flaps for defects of skin and adipose tissue less than 5 mm in size have the highest need for revision surgery; thus, defects of this small size should be repaired primarily.4

When using a V-Y advancement flap to correct large defects, there are 3 common complications that may arise: fullness medial to the commissure, a depressed vermilion lip, and a standing cutaneous deformity along the trailing edge of the flap where the Y is formed upon closure of the donor site. To decrease the fullness, a skin excision from the inferior border of the flap along the vermiliocutaneous border can be made to debulk the area. A vermilion advancement can be used to optimize the vermiliocutaneous junction. Potential standing cutaneous deformity is addressed by excising a small ellipse of skin oriented along the axis of the relaxed skin tension lines.15

Abbé-Estlander Flap

The Abbé-Estlander flap (also known as a transoral cross-lip flap) is a full-thickness myocutaneous interpolation flap with blood supply from the labial artery. It is used for lower lip tumors that have deep invasion into muscle and are 30% to 60% of the horizontal lip.8,9 Abbé transposition flaps are used for defects medial to the oral commissure and are best suited for philtrum reconstruction, whereas Estlander flaps are for defects that involve the oral commissure.9,18 Interpolation flaps usually are performed in 2 stages, but some dermatologic surgeons have reported success with single-stage procedures.1 The second-stage division usually is performed 2 to 3 weeks after flap insetting to allow time for neovascularization, which is crucial for pedicle survival.8,9,19

Advantages of this type of flap are the preservation of orbicularis oris strength and a functional and aesthetic result with minimal change in appearance for defects sized from one-third to two-thirds the width of the lip.20 This aesthetic effect is particularly notable when the donor flap is taken from the mediolateral upper lip, allowing the scarred area to blend into the nasolabial fold.8 Disadvantages of this flap are a risk for microstomia, lip vermilion misalignment, and lip adhesion.21 It is important that patients are educated on the need for multiple surgeries when using this type of flap, as patients favor single-step procedures.1 The Abbé flap requires 2 surgeries, whereas the Estlander flap requires only 1. However, patients commonly require commissuroplasty with the Estlander flap alone.21

Gillies Fan Flap, Karapandzic Flap, Bernard-Webster Flap, and Bernard-Burrow-Webster Flap

The Gillies fan flap, Karapandzic flap, Bernard-Webster (BW) flap, and modified Bernard-Burrow-Webster flap are the likely choices for repair of lip defects that encompass more than two-thirds of the lip.9,10,22 The Karapandzic and BW flaps are the 2 most frequently used for reconstruction of larger lower lip defects and only require 1 surgery.

Upper lip full-thickness defects that are too big for an Abbé-Estlander flap are closed with the Gillies fan flap.18 These defects involve 70% to 80% of the horizontal lip.9 The Gillies fan flap design redistributes the remaining lip to provide similar tissue quality and texture to fill the large defects.9,23 Compared to Karapandzic and Bernard flaps, Gillies fan incision closures are hidden well in the nasolabial folds, and the degree of microstomy is decreased because of the rotation of the flaps. However, rotation of medial cheek flaps can distort the orbicular muscular fibers and the anatomy of the commissure, which may require repair with commissurotomy. Drawbacks include a risk for denervation that can result in temporary oral sphincter incompetence.23 The bilateral Gillies fan flap carries a risk for microstomy as well as misalignment of the lip vermilion and round commissures.21

The Karapandzic flap is similar to the Gillies fan flap but only involves the skin and mucosa.9 This flap can be used for lateral or medial upper lip defects greater than one-third the width of the entire lip. This single-procedure flap allows for labial continuity, preserved sensation, and motor function; however, microstomia and misalignment of the oral commissure are common.1,18,21 In a retrospective study by Nicholas et al,4 the only flap reported to have a poor functional outcome was the Karapandzic flap, with 3 patients reporting altered sensation and 1 patient reporting persistent stiffness while smiling.

The BW flap can be applied for extensive full-thickness defects greater than one-third the lower lip and for defects with limited residual lip. This flap also can be used in cases where only skin is excised, as the flap does not depend on reminiscent lip tissue for reconstruction of the new lower lip. Sensory function is maintained given adequate visualization and preservation of the local vascular, nervous, and muscular systems. Disadvantages of the BW flap include an incision notch in the region of the lower lip; blunting of the alveolobuccal sulcus; and functional deficits, such as lip incontinence to liquids during the postoperative period.21

The Bernard-Burrow-Webster flap is used for large lower lip defects and preserves the oral commissures by advancing adjacent cheek tissue and remaining lip tissue medially.10 It allows for larger site mobilization, but it is possible to see some resulting oral incontinence.1,10 The Burow wedge flap is a variant of the advancement flap, with the Burow triangle located lateral to the oral commissure. Caution must be taken to avoid intraoperative bleeding from the labial and angular arteries. In addition, there also may be downward displacement of the vermilion border.5

How to Choose a Flap

The orbicularis oris is a circular muscle that surrounds both the upper and lower lips. It is pulled into an oval, allowing for sphincter function by radially oriented muscles, all of which are innervated by the facial nerve. Other key anatomical structures of the lips include the tubercle (vermilion prominence), Cupid’s bow and philtrum, nasolabial folds, white roll, hair-bearing area, and vermilion border. The lips are divided into cutaneous, mucosal, and vermilion parts, with the vermilion area divided into dry/external and wet/internal areas. Sensation to the upper lip is provided by the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve via the infraorbital nerve. The lower lip is innervated by the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve via the inferior alveolar nerve. The labial artery, a branch of the facial artery, is responsible for blood supply to the lips.3,9 Because of the complex anatomy of the lips, careful reconstruction is crucial for functional and aesthetic preservation.

There are a variety of lip defect repairs, but all local flaps aim to preserve aesthetics and function. The Table summarizes the key risks and benefits of each flap. Local flap techniques can be used in combination for more complex defects.3 For example, Nadiminti et al19 described the combination of the Abbé flap and V-Y advancement flap to restore function and create a new symmetric nasolabial fold. Dermatologic surgeons will determine the most suitable technique based on tumor location, tumor stage or depth of invasion (partial or full thickness), and preservation of function and aesthetics.1

Other factors to consider when choosing a local flap are the patient’s age, tissue laxity, dentition/need for dentures, and any prior treatments.7 Scar revision surgery may be needed after reconstruction, especially with longer vertical scars in areas without other rhytides. In addition, paresthesia is common after Mohs micrographic surgery of the face; however, new neural networks are created postoperatively, and most paresthesia resolves within 1 year of the repair.4 Dermabrasion and Z-plasty also may be considered, as they have been shown to be successful in improving final outcomes.9 Overall, local flaps have risks for infection, flap necrosis, and bleeding, though the incidence is low in reconstructions of the face.

Final Thoughts

There are several mechanisms to repair upper and lower lip defects resulting from surgical removal of cutaneous cancers. This review of specific flaps used in lip reconstruction provides a comprehensive overview of indications, advantages, and disadvantages of available lip flaps.

The lip is commonly affected by skin cancer because of increased sun exposure and actinic damage, with basal cell carcinoma typically occurring on the upper lip and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) on the lower lip. The risk for metastatic spread of SCC on the lip is higher than cutaneous SCC on other facial locations but lower than SCC of the oral mucosa.1,2 If the tumor is operable and the patient has no contraindications to surgery, Mohs micrographic surgery is the preferred treatment, as it allows for maximal healthy tissue preservation and has the lowest recurrence rates.1-3 Once the tumor is removed and margins are confirmed to be negative, one must consider the options for defect closure, including healing by secondary intention, primary/direct closure, full-thickness skin grafts, local flaps, or free flaps.4 Secondary intention may lead to wound contracture and suboptimal functional and cosmetic outcomes. Primary wedge closure can be utilized for optimal functional and cosmetic outcomes when the defect involves less than one-third of the horizontal width of the vermilion. For larger defects, the surgeon must consider a flap or graft. Skin grafts are less favorable than local flaps because they may have different skin color, texture, and hair-bearing properties than the recipient area.3,5 In addition, grafts require a separate donor site, which means more pain, recovery time, and risk for complications for the patient.3 Free flaps similarly utilize tissue and blood supply from a donor site to repair major tissue loss. Radial forearm free flaps commonly are used for large lip defects but are more extensive, risky, and costly compared to local flaps for smaller defects under local anesthesia or nerve blocks.6,7 With these considerations, a local lip flap often is the most ideal repair method.

When performing a local lip flap, it is important to consider the functional and aesthetic aspects of the lips. The lower face is more susceptible to distortion and wound contraction after defect repair because it lacks a substantial supportive fibrous network. The dynamics of opposing lip elevator and depressor muscles make the lips a visual focal point and a crucial structure for facial expression, mastication, oral continence, speech phonation, and mouth opening and closing.2,4,8,9 Aesthetics and symmetry of the lips also are a large part of facial recognition and self-image.9

Lip defects are classified as partial thickness involving skin and muscle or full thickness involving skin, muscle, and mucosa. Partial-thickness wounds less than one-third the width of the horizontal lip can be repaired with a primary wedge resection or left to heal by secondary intention if the defect only involves the superficial vermilion.2 For defects larger than one-third the width of the horizontal lip, local flaps are favored to allow for closely matched skin and lip mucosa to fill in the defect.9 Full-thickness defects are further classified based on defect width compared to total lip width (ie, less than one-third, between one-third and two-thirds, and greater than two-thirds) as well as location (ie, medial, lateral, upper lip, lower lip).2,10

There are several local lip flap reconstruction options available, and choosing one is based on defect size and location. We provide a succinct review of the indications, risks, and benefits of commonly utilized flaps (Table), as well as artist renderings of all of the flaps (Figure).

Vermilion Flaps

Vermilion flaps are used to close partial-thickness defects of the vermilion border, an area that poses unique obstacles of repair with blending distant tissues to match the surroundings.8 Goldstein11 developed an adjacent ipsilateral vermilion flap utilizing an arterialized myocutaneous flap for reconstruction of vermilion defects. Later, this technique was modified by Sawada et al12 into a bilateral adjacent advancement flap for closure of central vermilion defects and may be preferred for defects 2 cm in size or larger. Bilateral flaps are smaller and therefore more viable than unilateral or larger flaps, allowing for a more aesthetic alignment of the vermilion border and preservation of muscle activity because muscle fibers are not cut. This technique also allows for more efficient stretching or medial advancement of the tissue while generating less tension on the distal flap portions. Burow triangles can be utilized if necessary for improved aesthetic outcome.1

Mucosal Advancement and Split Myomucosal Advancement Flap

The mucosal advancement technique can be considered for tumors that do not involve the adjacent cutaneous skin or the orbicularis oris muscle; thus, the reconstruction involves only the superficial vermilion area.7,13 Mucosal incisions are made at the gingivobuccal sulcus, and the mucosal flap is elevated off the orbicularis oris muscle and advanced into the defect.10 A plane of dissection is maintained while preserving the labial artery. Undermining effectively advances wet mucosa into the dry mucosal lip to create a neovermilion. However, the reconstructed lip often appears thinner and will possibly be a different shade compared to the adjacent native lip. These discrepancies become more evident with deeper defects.7

There is a risk for cosmetic distortion and scar contraction with advancing the entire mucosa. Eirís et al13 described a solution—a bilateral mucosal rotation flap in which the primary incision is made along the entire vermilion border and tissue is undermined to allow advancement of the mucosa. Because the wound closure tension lays across the entire lip, there is less risk for scar contraction, even if the flap movement is unequal on either side of the defect.13

Although mucosal advancement flaps are a classic choice for reconstruction following a vermilion defect, other techniques, such as primary closure, should be considered in elderly patients and patients taking anticoagulants because of the risks for flap necrosis, swelling, bruising, hematoma, and dysesthesia, as well as a decrease in the anterior-posterior dimension of the lip. These risks can be attributed to trauma of surrounding tissue and stress secondary to longer overall operating times.14

Split myomucosal advancement flaps are used in similar scenarios as myomucosal advancement flaps but for larger red lip defects that are less than 50% the length of the upper or lower lip. Split myomucosal advancement flaps utilize an axial flap based on the labial artery, which provides robust vascular supply to the reconstructed area. This vascularity, along with lateral motor innervation of the orbicularis oris, allows for split myomucosal advancement flaps to restore the resected volume, preserve lip function, and minimize postoperative microstomia.7

V-Y Advancement Flaps

V-Y advancement flaps are based on a subcutaneous tissue pedicle and are optimal for partial- and full-thickness defects larger than 1 cm on the lateral upper lips, whereas bilateral V-Y advancement flaps are recommended for central lip defects.15-17 Advantages of V-Y advancement flaps are preserved facial symmetry and maintenance of the oral sphincter and facial nerve function. The undermining portions allow for advancement of a skin flap of similar thickness and contour into the upper or lower lip.15 Disadvantages include facial asymmetry with larger defects involving the melolabial fold as well as paresthesia after closure. However, in one study, no paresthesia was reported more than 12 months postprocedure.4 The biggest disadvantage of the V-Y advancement flap is the kite-shaped scar and possible trapdoor deformity.5,15 When working medially, the addition of the pincer modification helps avoid blunting of the philtrum and recreates a Cupid’s bow by curling the lateral flap edges medially to resemble a teardrop shape.17 V-Y advancement flaps for defects of skin and adipose tissue less than 5 mm in size have the highest need for revision surgery; thus, defects of this small size should be repaired primarily.4

When using a V-Y advancement flap to correct large defects, there are 3 common complications that may arise: fullness medial to the commissure, a depressed vermilion lip, and a standing cutaneous deformity along the trailing edge of the flap where the Y is formed upon closure of the donor site. To decrease the fullness, a skin excision from the inferior border of the flap along the vermiliocutaneous border can be made to debulk the area. A vermilion advancement can be used to optimize the vermiliocutaneous junction. Potential standing cutaneous deformity is addressed by excising a small ellipse of skin oriented along the axis of the relaxed skin tension lines.15

Abbé-Estlander Flap

The Abbé-Estlander flap (also known as a transoral cross-lip flap) is a full-thickness myocutaneous interpolation flap with blood supply from the labial artery. It is used for lower lip tumors that have deep invasion into muscle and are 30% to 60% of the horizontal lip.8,9 Abbé transposition flaps are used for defects medial to the oral commissure and are best suited for philtrum reconstruction, whereas Estlander flaps are for defects that involve the oral commissure.9,18 Interpolation flaps usually are performed in 2 stages, but some dermatologic surgeons have reported success with single-stage procedures.1 The second-stage division usually is performed 2 to 3 weeks after flap insetting to allow time for neovascularization, which is crucial for pedicle survival.8,9,19