User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

Obesity increases risk of complications with hernia repair

Both obese and underweight patients undergoing ventral hernia repair have a significantly greater risk of complications, particularly if they have strangulated/reducible hernias, according to data published online in Surgery.

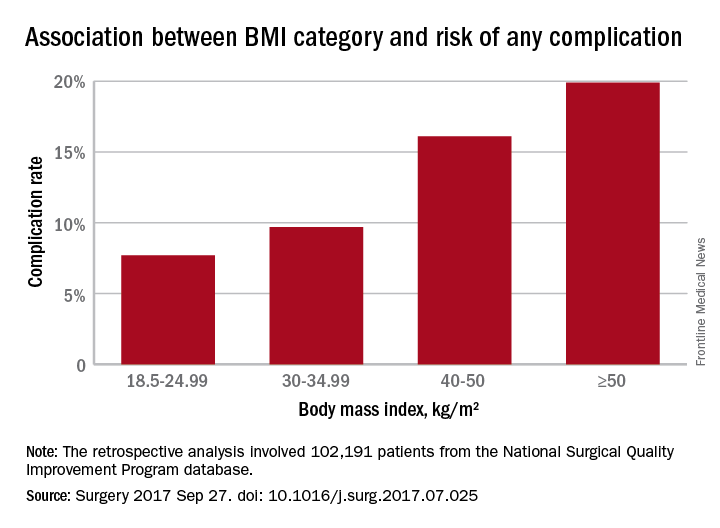

In a retrospective analysis, researchers examined data from 102,191 patients – 58.5% of whom were obese – who underwent ventral hernia repair, and found a J-shaped curve in the association between complication rates and body mass index.

Underweight patients with a BMI less than 18.5kg/m2 had a 10% risk of complications, while those of normal BMI (18.5-24.99) had the lowest complication risk: 7.7%. Complication rates then increased steadily with increasing BMI; 8.2% for overweight patients, 9.7% for the obese, 12.2% for the severely obese, 16.1% for the morbidly obese, and 19.9% for the super obese (Surgery 2017, Sep 27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2017.07.025).

Analysis by individual medical complications showed that postoperative pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, acute renal failure, and urinary tract infection were all statistically significantly more common with increasing BMI. The risk of myocardial infarction did not differ significantly with BMI.

The researchers also examined the effects of different hernia types. The 70.3% of patients who had reducible hernias had lower complication rates overall, as well as lower rates of complications in each category of operative, medical, and respiratory, compared with the 29.7% of patients with strangulated/incarcerated hernias.

Nearly one-quarter of the patients in the study were undergoing recurrent ventral hernia repair, and these patients were more likely to have a higher BMI.

After taking into account variables such as age, smoking comorbidities, type of hernia, and type of repair, the authors concluded that the odds of having any complication increased significantly above a BMI of 30 kg/m2, using normal weight BMI as a reference. The odds were 22% higher in those with BMIs in the 30-34.99 range, 54% higher for those in the 35-39.99 range, twofold higher for those with a BMI between 40 and 50, and 2.6-fold higher above 50 kg/m2.

“Surgeons are presented with increasing numbers of obese patients, and the best way to manage ventral hernias in this population remains unclear,” the authors wrote, although they raised the possibility that laparoscopic procedures reduce the risk of some complications.

“Although the majority of VHRs performed utilize an open technique, studies have found decreased duration of stay, morbidity, and, in selected studies, even decreased recurrence using the laparoscopic approach.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

Both obese and underweight patients undergoing ventral hernia repair have a significantly greater risk of complications, particularly if they have strangulated/reducible hernias, according to data published online in Surgery.

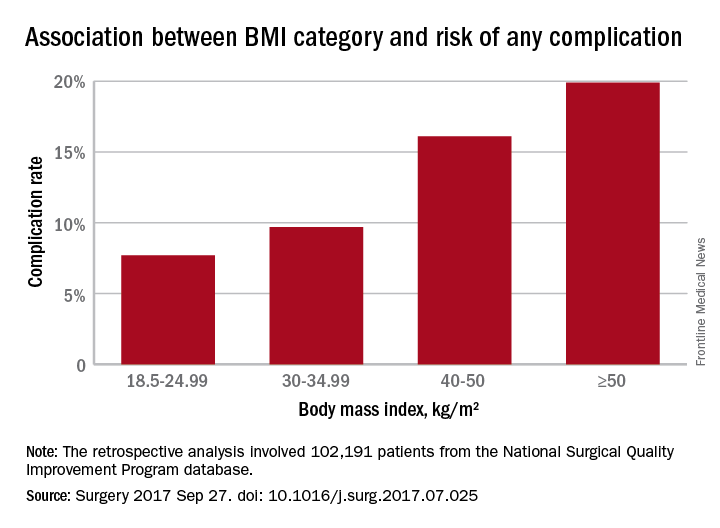

In a retrospective analysis, researchers examined data from 102,191 patients – 58.5% of whom were obese – who underwent ventral hernia repair, and found a J-shaped curve in the association between complication rates and body mass index.

Underweight patients with a BMI less than 18.5kg/m2 had a 10% risk of complications, while those of normal BMI (18.5-24.99) had the lowest complication risk: 7.7%. Complication rates then increased steadily with increasing BMI; 8.2% for overweight patients, 9.7% for the obese, 12.2% for the severely obese, 16.1% for the morbidly obese, and 19.9% for the super obese (Surgery 2017, Sep 27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2017.07.025).

Analysis by individual medical complications showed that postoperative pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, acute renal failure, and urinary tract infection were all statistically significantly more common with increasing BMI. The risk of myocardial infarction did not differ significantly with BMI.

The researchers also examined the effects of different hernia types. The 70.3% of patients who had reducible hernias had lower complication rates overall, as well as lower rates of complications in each category of operative, medical, and respiratory, compared with the 29.7% of patients with strangulated/incarcerated hernias.

Nearly one-quarter of the patients in the study were undergoing recurrent ventral hernia repair, and these patients were more likely to have a higher BMI.

After taking into account variables such as age, smoking comorbidities, type of hernia, and type of repair, the authors concluded that the odds of having any complication increased significantly above a BMI of 30 kg/m2, using normal weight BMI as a reference. The odds were 22% higher in those with BMIs in the 30-34.99 range, 54% higher for those in the 35-39.99 range, twofold higher for those with a BMI between 40 and 50, and 2.6-fold higher above 50 kg/m2.

“Surgeons are presented with increasing numbers of obese patients, and the best way to manage ventral hernias in this population remains unclear,” the authors wrote, although they raised the possibility that laparoscopic procedures reduce the risk of some complications.

“Although the majority of VHRs performed utilize an open technique, studies have found decreased duration of stay, morbidity, and, in selected studies, even decreased recurrence using the laparoscopic approach.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

Both obese and underweight patients undergoing ventral hernia repair have a significantly greater risk of complications, particularly if they have strangulated/reducible hernias, according to data published online in Surgery.

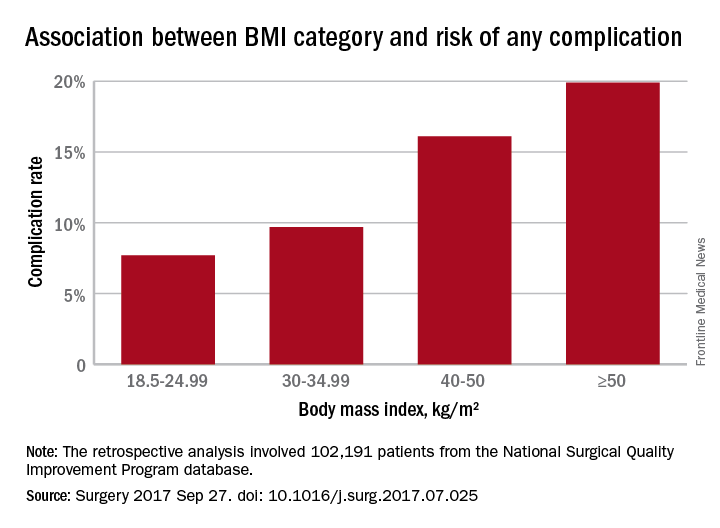

In a retrospective analysis, researchers examined data from 102,191 patients – 58.5% of whom were obese – who underwent ventral hernia repair, and found a J-shaped curve in the association between complication rates and body mass index.

Underweight patients with a BMI less than 18.5kg/m2 had a 10% risk of complications, while those of normal BMI (18.5-24.99) had the lowest complication risk: 7.7%. Complication rates then increased steadily with increasing BMI; 8.2% for overweight patients, 9.7% for the obese, 12.2% for the severely obese, 16.1% for the morbidly obese, and 19.9% for the super obese (Surgery 2017, Sep 27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2017.07.025).

Analysis by individual medical complications showed that postoperative pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, acute renal failure, and urinary tract infection were all statistically significantly more common with increasing BMI. The risk of myocardial infarction did not differ significantly with BMI.

The researchers also examined the effects of different hernia types. The 70.3% of patients who had reducible hernias had lower complication rates overall, as well as lower rates of complications in each category of operative, medical, and respiratory, compared with the 29.7% of patients with strangulated/incarcerated hernias.

Nearly one-quarter of the patients in the study were undergoing recurrent ventral hernia repair, and these patients were more likely to have a higher BMI.

After taking into account variables such as age, smoking comorbidities, type of hernia, and type of repair, the authors concluded that the odds of having any complication increased significantly above a BMI of 30 kg/m2, using normal weight BMI as a reference. The odds were 22% higher in those with BMIs in the 30-34.99 range, 54% higher for those in the 35-39.99 range, twofold higher for those with a BMI between 40 and 50, and 2.6-fold higher above 50 kg/m2.

“Surgeons are presented with increasing numbers of obese patients, and the best way to manage ventral hernias in this population remains unclear,” the authors wrote, although they raised the possibility that laparoscopic procedures reduce the risk of some complications.

“Although the majority of VHRs performed utilize an open technique, studies have found decreased duration of stay, morbidity, and, in selected studies, even decreased recurrence using the laparoscopic approach.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM SURGERY

Key clinical point: Obesity, as well as underweight, are associated with significantly higher rates of complications with ventral repair.

Major finding: Complication rates increased with increasing BMI; 8.2% for overweight patients, 9.7% for the obese, 12.2% for the severely obese, 16.1% for the morbidly obese, and 19.9% for the super obese.

Data source: Retrospective analysis of 102,191 patients who underwent ventral hernia repair.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest were declared.

Clinical trial: Mesh weights compared for ventral hernia repair

A clinical trial comparing heavy- and medium-weight surgical mesh for ventral hernia repairs is recruiting patients.

The Long-term Results of Heavy Weight Versus Medium Weight Mesh in Ventral Hernia Repair trial will determine if mesh weight has an impact on postoperative pain, ventral hernia recurrence, incidence of deep wound infection, and overall quality of life following ventral hernia repair with mesh.

Patients will be included if they have a ventral hernia, are 18 years of age or older, have a defect classified as CDC wound class 1, are able to achieve midline fascial closure, have a hernia defect width less than or equal to 20 cm, can tolerate general anesthesia, and can give informed consent. Patients will be excluded if they have undergone emergent ventral hernia repair, undergone laparoscopic or robotic ventral hernia repair, undergone staged repair of their ventral hernia, or are pregnant at the time of the surgery.

The primary outcome of this trial is pain that will be measured via the NIH Promis 3A Pain instrument in 1 year postoperatively. Other outcomes include hernia recurrence, to be determined via the Ventral Hernia Recurrence Inventory; the occurrence of a deep wound infection, to be determined by physical examination and/or computed tomography scanning; and quality of life measured by the HerQLes questionnaire.

Find more information at clinicaltrials.gov.

A clinical trial comparing heavy- and medium-weight surgical mesh for ventral hernia repairs is recruiting patients.

The Long-term Results of Heavy Weight Versus Medium Weight Mesh in Ventral Hernia Repair trial will determine if mesh weight has an impact on postoperative pain, ventral hernia recurrence, incidence of deep wound infection, and overall quality of life following ventral hernia repair with mesh.

Patients will be included if they have a ventral hernia, are 18 years of age or older, have a defect classified as CDC wound class 1, are able to achieve midline fascial closure, have a hernia defect width less than or equal to 20 cm, can tolerate general anesthesia, and can give informed consent. Patients will be excluded if they have undergone emergent ventral hernia repair, undergone laparoscopic or robotic ventral hernia repair, undergone staged repair of their ventral hernia, or are pregnant at the time of the surgery.

The primary outcome of this trial is pain that will be measured via the NIH Promis 3A Pain instrument in 1 year postoperatively. Other outcomes include hernia recurrence, to be determined via the Ventral Hernia Recurrence Inventory; the occurrence of a deep wound infection, to be determined by physical examination and/or computed tomography scanning; and quality of life measured by the HerQLes questionnaire.

Find more information at clinicaltrials.gov.

A clinical trial comparing heavy- and medium-weight surgical mesh for ventral hernia repairs is recruiting patients.

The Long-term Results of Heavy Weight Versus Medium Weight Mesh in Ventral Hernia Repair trial will determine if mesh weight has an impact on postoperative pain, ventral hernia recurrence, incidence of deep wound infection, and overall quality of life following ventral hernia repair with mesh.

Patients will be included if they have a ventral hernia, are 18 years of age or older, have a defect classified as CDC wound class 1, are able to achieve midline fascial closure, have a hernia defect width less than or equal to 20 cm, can tolerate general anesthesia, and can give informed consent. Patients will be excluded if they have undergone emergent ventral hernia repair, undergone laparoscopic or robotic ventral hernia repair, undergone staged repair of their ventral hernia, or are pregnant at the time of the surgery.

The primary outcome of this trial is pain that will be measured via the NIH Promis 3A Pain instrument in 1 year postoperatively. Other outcomes include hernia recurrence, to be determined via the Ventral Hernia Recurrence Inventory; the occurrence of a deep wound infection, to be determined by physical examination and/or computed tomography scanning; and quality of life measured by the HerQLes questionnaire.

Find more information at clinicaltrials.gov.

FROM CLINICALTRIALS.GOV

Many new cancer drugs lack evidence of survival or QoL benefit

Even after several years on the market, only about half of cancer drug indications recently approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) had conclusive evidence that they can extend or improve quality of life, according to results of a retrospective cohort study.

With a median of 5.4 years of follow-up, significant improvements in overall survival or quality of life had been published for 35 of 68 (51%) cancer drug indications approved by the EMA, according to the report by Courtney Davis, MD, senior lecturer in the department of global health and social medicine, King’s College London, United Kingdom, and colleagues.

Furthermore, not all survival benefits were clinically meaningful, according to an analysis published in the report.

The dearth of evidence for survival or quality-of-life benefits has “negative implications” for both patients and public health, Dr. Davis and colleagues said in their article (BMJ 2017 Oct 5. doi:10.1136/bmj.j4530).

“When expensive drugs that lack clinically meaningful benefits are approved and paid for within publicly funded healthcare systems, individual patients can be harmed, important societal resources wasted, and the delivery of equitable and affordable care undermined,” they wrote.

Dr. Davis and associates systematically evaluated the evidence base for regulatory and scientific reports on 48 cancer drugs approved for 68 indications by the EMA between 2009-2013. Of those indications, 17 were for hematologic malignancies and 51 were for solid tumors.

Only 18 of 68 indications (26%) were supported by pivotal studies that had a primary outcome of overall survival, according to the investigators. That was an important finding for the investigators, who wrote that that EMA commonly accepts use of surrogate measures of drug benefit despite their own statements that overall survival is the “most persuasive outcome” in studies of new oncology drugs.

“To a large extent, regulatory evidence standards determine the clinical value of … new oncology drugs,” Dr. Davis and co-authors wrote. “Our study suggests these standards are failing to incentivize drug development that best meets the needs of patients, clinicians, and healthcare systems.”

The investigators also assessed the clinical value of reported improvements using the European Society for Medical Oncology-Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale (ESMO-MCBS). According to investigators, only 11 of the 23 drugs used to treat solid tumors (48%) reached the threshold for a meaningful survival benefit.

This report in BMJ echoes findings of an earlier study by Chul Kim, MD, and colleagues looking at cancer drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) between 2008 and 2012 (JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(12):1992-4).

Dr. Kim, of the medical oncology service, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md., and colleagues found that 36 of 54 FDA approvals (67%) occurred with no evidence of survival or quality of life benefit. After a median of 4.4 years of follow-up, only 5 of those 36 (14%) had additional randomized study data that showed an improvement in overall survival, according to the published report.

The study was supported by Health Action International, which did not have a role in study design or data collection, analysis, or interpretation. The authors did not give financial disclosures.

The expense and toxicity of cancer drugs mean we have an obligation to expose patients to treatment only when they can reasonably expect an improvement in survival or quality of life. The study by Davis and colleagues suggests we may be falling far short of this important benchmark.

Few cancer drugs come to market with good evidence that they improve patient centered outcomes. If they do, they often offer marginal benefits that may be lost in the heterogeneous patients of the real world. Most approvals of cancer drugs are based on flimsy or untested surrogate endpoints, and postmarketing studies rarely validate the efficacy and safety of these drugs on patient centered endpoints.

In the United States, this broken system means huge expenditures on cancer drugs with certain toxicity but uncertain benefit. In Europe, payers yield the stick left unused by lax regulatoers. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) excludes from reimbursement drugs that provide only marginal or uncertain benefits at high cost. Their decisions are continually subjected to political scrutiny and public criticism.

What can be done? The default path to market for all cancer drugs should include rigorous testing against the best standard of care in randomized trials powered to rule in or rule out a clinically meaningful difference in patient centered outcomes in a representative population. The use of uncontrolled study designs or surrogate endpoints should be the exception, not the rule.

Vinay Prasad, MD, MPH, is assistant professor of medicine at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland. He declared a competing interest (royalties from his book Ending Medical Reversal). These comments are from his editorial (BMJ 2017 Oct 5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4528 )

The expense and toxicity of cancer drugs mean we have an obligation to expose patients to treatment only when they can reasonably expect an improvement in survival or quality of life. The study by Davis and colleagues suggests we may be falling far short of this important benchmark.

Few cancer drugs come to market with good evidence that they improve patient centered outcomes. If they do, they often offer marginal benefits that may be lost in the heterogeneous patients of the real world. Most approvals of cancer drugs are based on flimsy or untested surrogate endpoints, and postmarketing studies rarely validate the efficacy and safety of these drugs on patient centered endpoints.

In the United States, this broken system means huge expenditures on cancer drugs with certain toxicity but uncertain benefit. In Europe, payers yield the stick left unused by lax regulatoers. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) excludes from reimbursement drugs that provide only marginal or uncertain benefits at high cost. Their decisions are continually subjected to political scrutiny and public criticism.

What can be done? The default path to market for all cancer drugs should include rigorous testing against the best standard of care in randomized trials powered to rule in or rule out a clinically meaningful difference in patient centered outcomes in a representative population. The use of uncontrolled study designs or surrogate endpoints should be the exception, not the rule.

Vinay Prasad, MD, MPH, is assistant professor of medicine at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland. He declared a competing interest (royalties from his book Ending Medical Reversal). These comments are from his editorial (BMJ 2017 Oct 5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4528 )

The expense and toxicity of cancer drugs mean we have an obligation to expose patients to treatment only when they can reasonably expect an improvement in survival or quality of life. The study by Davis and colleagues suggests we may be falling far short of this important benchmark.

Few cancer drugs come to market with good evidence that they improve patient centered outcomes. If they do, they often offer marginal benefits that may be lost in the heterogeneous patients of the real world. Most approvals of cancer drugs are based on flimsy or untested surrogate endpoints, and postmarketing studies rarely validate the efficacy and safety of these drugs on patient centered endpoints.

In the United States, this broken system means huge expenditures on cancer drugs with certain toxicity but uncertain benefit. In Europe, payers yield the stick left unused by lax regulatoers. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) excludes from reimbursement drugs that provide only marginal or uncertain benefits at high cost. Their decisions are continually subjected to political scrutiny and public criticism.

What can be done? The default path to market for all cancer drugs should include rigorous testing against the best standard of care in randomized trials powered to rule in or rule out a clinically meaningful difference in patient centered outcomes in a representative population. The use of uncontrolled study designs or surrogate endpoints should be the exception, not the rule.

Vinay Prasad, MD, MPH, is assistant professor of medicine at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland. He declared a competing interest (royalties from his book Ending Medical Reversal). These comments are from his editorial (BMJ 2017 Oct 5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4528 )

Even after several years on the market, only about half of cancer drug indications recently approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) had conclusive evidence that they can extend or improve quality of life, according to results of a retrospective cohort study.

With a median of 5.4 years of follow-up, significant improvements in overall survival or quality of life had been published for 35 of 68 (51%) cancer drug indications approved by the EMA, according to the report by Courtney Davis, MD, senior lecturer in the department of global health and social medicine, King’s College London, United Kingdom, and colleagues.

Furthermore, not all survival benefits were clinically meaningful, according to an analysis published in the report.

The dearth of evidence for survival or quality-of-life benefits has “negative implications” for both patients and public health, Dr. Davis and colleagues said in their article (BMJ 2017 Oct 5. doi:10.1136/bmj.j4530).

“When expensive drugs that lack clinically meaningful benefits are approved and paid for within publicly funded healthcare systems, individual patients can be harmed, important societal resources wasted, and the delivery of equitable and affordable care undermined,” they wrote.

Dr. Davis and associates systematically evaluated the evidence base for regulatory and scientific reports on 48 cancer drugs approved for 68 indications by the EMA between 2009-2013. Of those indications, 17 were for hematologic malignancies and 51 were for solid tumors.

Only 18 of 68 indications (26%) were supported by pivotal studies that had a primary outcome of overall survival, according to the investigators. That was an important finding for the investigators, who wrote that that EMA commonly accepts use of surrogate measures of drug benefit despite their own statements that overall survival is the “most persuasive outcome” in studies of new oncology drugs.

“To a large extent, regulatory evidence standards determine the clinical value of … new oncology drugs,” Dr. Davis and co-authors wrote. “Our study suggests these standards are failing to incentivize drug development that best meets the needs of patients, clinicians, and healthcare systems.”

The investigators also assessed the clinical value of reported improvements using the European Society for Medical Oncology-Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale (ESMO-MCBS). According to investigators, only 11 of the 23 drugs used to treat solid tumors (48%) reached the threshold for a meaningful survival benefit.

This report in BMJ echoes findings of an earlier study by Chul Kim, MD, and colleagues looking at cancer drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) between 2008 and 2012 (JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(12):1992-4).

Dr. Kim, of the medical oncology service, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md., and colleagues found that 36 of 54 FDA approvals (67%) occurred with no evidence of survival or quality of life benefit. After a median of 4.4 years of follow-up, only 5 of those 36 (14%) had additional randomized study data that showed an improvement in overall survival, according to the published report.

The study was supported by Health Action International, which did not have a role in study design or data collection, analysis, or interpretation. The authors did not give financial disclosures.

Even after several years on the market, only about half of cancer drug indications recently approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) had conclusive evidence that they can extend or improve quality of life, according to results of a retrospective cohort study.

With a median of 5.4 years of follow-up, significant improvements in overall survival or quality of life had been published for 35 of 68 (51%) cancer drug indications approved by the EMA, according to the report by Courtney Davis, MD, senior lecturer in the department of global health and social medicine, King’s College London, United Kingdom, and colleagues.

Furthermore, not all survival benefits were clinically meaningful, according to an analysis published in the report.

The dearth of evidence for survival or quality-of-life benefits has “negative implications” for both patients and public health, Dr. Davis and colleagues said in their article (BMJ 2017 Oct 5. doi:10.1136/bmj.j4530).

“When expensive drugs that lack clinically meaningful benefits are approved and paid for within publicly funded healthcare systems, individual patients can be harmed, important societal resources wasted, and the delivery of equitable and affordable care undermined,” they wrote.

Dr. Davis and associates systematically evaluated the evidence base for regulatory and scientific reports on 48 cancer drugs approved for 68 indications by the EMA between 2009-2013. Of those indications, 17 were for hematologic malignancies and 51 were for solid tumors.

Only 18 of 68 indications (26%) were supported by pivotal studies that had a primary outcome of overall survival, according to the investigators. That was an important finding for the investigators, who wrote that that EMA commonly accepts use of surrogate measures of drug benefit despite their own statements that overall survival is the “most persuasive outcome” in studies of new oncology drugs.

“To a large extent, regulatory evidence standards determine the clinical value of … new oncology drugs,” Dr. Davis and co-authors wrote. “Our study suggests these standards are failing to incentivize drug development that best meets the needs of patients, clinicians, and healthcare systems.”

The investigators also assessed the clinical value of reported improvements using the European Society for Medical Oncology-Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale (ESMO-MCBS). According to investigators, only 11 of the 23 drugs used to treat solid tumors (48%) reached the threshold for a meaningful survival benefit.

This report in BMJ echoes findings of an earlier study by Chul Kim, MD, and colleagues looking at cancer drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) between 2008 and 2012 (JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(12):1992-4).

Dr. Kim, of the medical oncology service, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md., and colleagues found that 36 of 54 FDA approvals (67%) occurred with no evidence of survival or quality of life benefit. After a median of 4.4 years of follow-up, only 5 of those 36 (14%) had additional randomized study data that showed an improvement in overall survival, according to the published report.

The study was supported by Health Action International, which did not have a role in study design or data collection, analysis, or interpretation. The authors did not give financial disclosures.

From BMJ

Key clinical point: Even after several years on the market, only about half of cancer drug indications recently approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) lacked conclusive evidence that they can extend or improve quality of life.

Major finding: With a median of 5.4 years of follow-up, significant improvements in overall survival or quality of life had been published for 35 of 68 (51%) cancer drug indications approved by the EMA.

Data source: Retrospective cohort study of regulatory and scientific reports on 48 cancer drugs approved for 68 indications by the EMA between 2009-2013.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Health Action International, which did not have a role in study design or data collection, analysis, or interpretation.

Duty vs. confidentiality

Question: During an office visit, a patient confided in his primary care provider his intention to go on a shooting spree. When pressed, he admitted he owned a firearm, but did not truly intend to carry out the act. He denied having a specific target location or victim in mind. The primary care provider (PCP) opted to counsel the patient, and continued him on his antidepressant medication. The PCP did not make a referral to a psychiatrist. Several weeks later, the patient put his threat into action, shooting and injuring several innocent shoppers at a mall.

In a lawsuit against the PCP, which of the following is best?

A. It is unethical for the PCP to report this threat, because it violates the principle of confidentiality.

B. Failure to warn under the circumstances definitely makes the physician liable.

C. The PCP is liable under the Tarasoff doctrine.

D. Without a named victim, there is no one to warn.

E. Whether the PCP is liable may turn on the issue of foreseeability, and an immediate referral to a psychiatrist would have been a more prudent course of action.

Answer: E. One of the physician’s sacred promises is to maintain patient confidentiality. It is more than an unspoken contractual agreement; it’s a central component of trust, without which the doctor-patient relationship cannot exist. Indeed, Hippocrates had cautioned, “whatever in connection with my professional practice, or not in connection with it, I see or hear, in the life of men, which ought not to be spoken of abroad, I will not divulge as reckoning that all should be kept secret.”

Thus, the recent expansive decision handed down by the Washington state Supreme Court stunned many mental health professionals.1 In Volk v. DeMeerleer, a clinic patient had confided in his psychiatrist over 9 years of therapy his suicidal and homicidal ideations. He eventually went on to kill his former girlfriend and one of her sons, and then committed suicide. The psychiatrist did not have full control of this clinic patient, nor had the patient named a specific victim. Nevertheless, the Volk court held that the doctor’s duty extended to any foreseeable harm by the patient, leaving it up to the jury to decide on the issue of foreseeability.

The court held that the psychiatrist had a “special relationship” with the victims, because he had a duty to exercise reasonable care to act, consistent with the standards of the mental health profession, in order to protect the foreseeable victims.

The court reasoned that some ability to control the patient’s conduct is sufficient for the “special relationship” and the consequent duty of care to exist, writing: “We find that absolute control is unnecessary, and the actions available to mental health professionals, even in the outpatient setting, weigh in favor of imposing a duty.” The court also noted that a psychiatrist’s obligation to protect third parties against patients’ violence would normally set aside confidentiality and yield to greater societal interests.

The vexing issue of compromising confidentiality in the name of protecting public safety had its genesis in the famous Tarasoff v. Regents of University of California case.2

In Tarasoff, the California court imposed a legal duty on a college psychologist to warn an intended victim of harm, even though that meant breaching confidentiality in a professional relationship. A jilted patient had confided in the university psychologist his intention to kill his ex-girlfriend. The information, though shared with campus security, was not released to the intended victim, whom the patient stabbed to death 2 months later.

The court reasoned that the protection of public safety was more important than the sanctity of the doctor-patient confidentiality relationship, pointing out: “We recognize the public interest in supporting effective treatment of mental illness and in protecting the rights of patients to privacy and the consequent public importance of safeguarding the confidential character of psychotherapeutic communication. Against this interest, however, we must weigh the public interest in safety from violent assault. ... In this risk-infested society, we can hardly tolerate the further exposure to danger that would result from a concealed knowledge of the therapist that his patient was lethal.”

Following Tarasoff, it is generally accepted that there is no affirmative duty to warn where there is no readily identifiable victim. In a subsequent case, the same court explained that “the duty to warn depends upon and arises from the existence of a prior threat to a specific identifiable victim. In those instances in which the released offender poses a predictable threat of harm to a named or readily identifiable victim or group of victims who can be effectively warned of the danger, a releasing agent may well be liable for failure to warn such persons. Despite the tragic events underlying the present complaint, plaintiffs’ decedent was not a known, identifiable victim, but rather a member of a large, amorphous public group of potential targets. Under these circumstances, we hold that County had no affirmative duty to warn plaintiffs, the police, the mother of the juvenile offender, or other local parents.”3

Commentators have suggested that such post-Tarasoff cases, coupled with the advent of state statutes that codify Tarasoff, have witnessed a retreat from imposing on clinicians a duty to warn.4 By dispensing with the control and “readily identifiable victim” elements, Volk appears to contradict this perceived trend. Foreseeability may turn out to be the dispositive issue.

Some have speculated whether Volk’s expanded view will apply to other professionals such as a family practitioner or even a school counselor. Physicians who are not experienced in treating mental health patients will do well to promptly refer their unstable patients to a specialist psychiatrist.

Volk can also be read as offering judicial insight into patients who pose a health hazard by insisting on operating a vehicle against medical advice. In its 2012 Code of Medical Ethics, the American Medical Association had this to say: “In situations where clear evidence of substantial driving impairment implies a strong threat to patient and public safety, and where the physician’s advice to discontinue driving privileges is ignored, it is desirable and ethical to notify the department of motor vehicles.”5

That is now replaced in the AMA code with a broader version covering the duty to disclose: “Physicians may disclose personal health information without the specific consent of the patient ... to other third parties situated to mitigate the threat when in the physician’s judgment there is a reasonable probability that: (i) the patient will seriously harm him/herself; or (ii) the patient will inflict serious physical harm on an identifiable individual or individuals.”6

Under Volk, physicians are now more likely to forsake confidentiality in the name of public safety – even in the absence of a readily identifiable potential victim.

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some of the materials have been taken from earlier columns in Internal Medicine News. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

References

1. Volk v. DeMeerleer, 386 P.3d 254 (Wa. 2016).

2. Tarasoff v. Regents of University of California, 551 P.2d 334 (Cal. 1976).

3. Thompson v. County of Alameda, 167 Cal. Rptr. 70, 76 (1980).

4. Behav Sci Law. 2001;19(3):325-43.

5. AMA Code of Medical Ethics [2.24 (3), 2012-2013 ed].

6. AMA Code of Medical Ethics, 2017 ed. [3.2.1 Confidentiality].

Question: During an office visit, a patient confided in his primary care provider his intention to go on a shooting spree. When pressed, he admitted he owned a firearm, but did not truly intend to carry out the act. He denied having a specific target location or victim in mind. The primary care provider (PCP) opted to counsel the patient, and continued him on his antidepressant medication. The PCP did not make a referral to a psychiatrist. Several weeks later, the patient put his threat into action, shooting and injuring several innocent shoppers at a mall.

In a lawsuit against the PCP, which of the following is best?

A. It is unethical for the PCP to report this threat, because it violates the principle of confidentiality.

B. Failure to warn under the circumstances definitely makes the physician liable.

C. The PCP is liable under the Tarasoff doctrine.

D. Without a named victim, there is no one to warn.

E. Whether the PCP is liable may turn on the issue of foreseeability, and an immediate referral to a psychiatrist would have been a more prudent course of action.

Answer: E. One of the physician’s sacred promises is to maintain patient confidentiality. It is more than an unspoken contractual agreement; it’s a central component of trust, without which the doctor-patient relationship cannot exist. Indeed, Hippocrates had cautioned, “whatever in connection with my professional practice, or not in connection with it, I see or hear, in the life of men, which ought not to be spoken of abroad, I will not divulge as reckoning that all should be kept secret.”

Thus, the recent expansive decision handed down by the Washington state Supreme Court stunned many mental health professionals.1 In Volk v. DeMeerleer, a clinic patient had confided in his psychiatrist over 9 years of therapy his suicidal and homicidal ideations. He eventually went on to kill his former girlfriend and one of her sons, and then committed suicide. The psychiatrist did not have full control of this clinic patient, nor had the patient named a specific victim. Nevertheless, the Volk court held that the doctor’s duty extended to any foreseeable harm by the patient, leaving it up to the jury to decide on the issue of foreseeability.

The court held that the psychiatrist had a “special relationship” with the victims, because he had a duty to exercise reasonable care to act, consistent with the standards of the mental health profession, in order to protect the foreseeable victims.

The court reasoned that some ability to control the patient’s conduct is sufficient for the “special relationship” and the consequent duty of care to exist, writing: “We find that absolute control is unnecessary, and the actions available to mental health professionals, even in the outpatient setting, weigh in favor of imposing a duty.” The court also noted that a psychiatrist’s obligation to protect third parties against patients’ violence would normally set aside confidentiality and yield to greater societal interests.

The vexing issue of compromising confidentiality in the name of protecting public safety had its genesis in the famous Tarasoff v. Regents of University of California case.2

In Tarasoff, the California court imposed a legal duty on a college psychologist to warn an intended victim of harm, even though that meant breaching confidentiality in a professional relationship. A jilted patient had confided in the university psychologist his intention to kill his ex-girlfriend. The information, though shared with campus security, was not released to the intended victim, whom the patient stabbed to death 2 months later.

The court reasoned that the protection of public safety was more important than the sanctity of the doctor-patient confidentiality relationship, pointing out: “We recognize the public interest in supporting effective treatment of mental illness and in protecting the rights of patients to privacy and the consequent public importance of safeguarding the confidential character of psychotherapeutic communication. Against this interest, however, we must weigh the public interest in safety from violent assault. ... In this risk-infested society, we can hardly tolerate the further exposure to danger that would result from a concealed knowledge of the therapist that his patient was lethal.”

Following Tarasoff, it is generally accepted that there is no affirmative duty to warn where there is no readily identifiable victim. In a subsequent case, the same court explained that “the duty to warn depends upon and arises from the existence of a prior threat to a specific identifiable victim. In those instances in which the released offender poses a predictable threat of harm to a named or readily identifiable victim or group of victims who can be effectively warned of the danger, a releasing agent may well be liable for failure to warn such persons. Despite the tragic events underlying the present complaint, plaintiffs’ decedent was not a known, identifiable victim, but rather a member of a large, amorphous public group of potential targets. Under these circumstances, we hold that County had no affirmative duty to warn plaintiffs, the police, the mother of the juvenile offender, or other local parents.”3

Commentators have suggested that such post-Tarasoff cases, coupled with the advent of state statutes that codify Tarasoff, have witnessed a retreat from imposing on clinicians a duty to warn.4 By dispensing with the control and “readily identifiable victim” elements, Volk appears to contradict this perceived trend. Foreseeability may turn out to be the dispositive issue.

Some have speculated whether Volk’s expanded view will apply to other professionals such as a family practitioner or even a school counselor. Physicians who are not experienced in treating mental health patients will do well to promptly refer their unstable patients to a specialist psychiatrist.

Volk can also be read as offering judicial insight into patients who pose a health hazard by insisting on operating a vehicle against medical advice. In its 2012 Code of Medical Ethics, the American Medical Association had this to say: “In situations where clear evidence of substantial driving impairment implies a strong threat to patient and public safety, and where the physician’s advice to discontinue driving privileges is ignored, it is desirable and ethical to notify the department of motor vehicles.”5

That is now replaced in the AMA code with a broader version covering the duty to disclose: “Physicians may disclose personal health information without the specific consent of the patient ... to other third parties situated to mitigate the threat when in the physician’s judgment there is a reasonable probability that: (i) the patient will seriously harm him/herself; or (ii) the patient will inflict serious physical harm on an identifiable individual or individuals.”6

Under Volk, physicians are now more likely to forsake confidentiality in the name of public safety – even in the absence of a readily identifiable potential victim.

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some of the materials have been taken from earlier columns in Internal Medicine News. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

References

1. Volk v. DeMeerleer, 386 P.3d 254 (Wa. 2016).

2. Tarasoff v. Regents of University of California, 551 P.2d 334 (Cal. 1976).

3. Thompson v. County of Alameda, 167 Cal. Rptr. 70, 76 (1980).

4. Behav Sci Law. 2001;19(3):325-43.

5. AMA Code of Medical Ethics [2.24 (3), 2012-2013 ed].

6. AMA Code of Medical Ethics, 2017 ed. [3.2.1 Confidentiality].

Question: During an office visit, a patient confided in his primary care provider his intention to go on a shooting spree. When pressed, he admitted he owned a firearm, but did not truly intend to carry out the act. He denied having a specific target location or victim in mind. The primary care provider (PCP) opted to counsel the patient, and continued him on his antidepressant medication. The PCP did not make a referral to a psychiatrist. Several weeks later, the patient put his threat into action, shooting and injuring several innocent shoppers at a mall.

In a lawsuit against the PCP, which of the following is best?

A. It is unethical for the PCP to report this threat, because it violates the principle of confidentiality.

B. Failure to warn under the circumstances definitely makes the physician liable.

C. The PCP is liable under the Tarasoff doctrine.

D. Without a named victim, there is no one to warn.

E. Whether the PCP is liable may turn on the issue of foreseeability, and an immediate referral to a psychiatrist would have been a more prudent course of action.

Answer: E. One of the physician’s sacred promises is to maintain patient confidentiality. It is more than an unspoken contractual agreement; it’s a central component of trust, without which the doctor-patient relationship cannot exist. Indeed, Hippocrates had cautioned, “whatever in connection with my professional practice, or not in connection with it, I see or hear, in the life of men, which ought not to be spoken of abroad, I will not divulge as reckoning that all should be kept secret.”

Thus, the recent expansive decision handed down by the Washington state Supreme Court stunned many mental health professionals.1 In Volk v. DeMeerleer, a clinic patient had confided in his psychiatrist over 9 years of therapy his suicidal and homicidal ideations. He eventually went on to kill his former girlfriend and one of her sons, and then committed suicide. The psychiatrist did not have full control of this clinic patient, nor had the patient named a specific victim. Nevertheless, the Volk court held that the doctor’s duty extended to any foreseeable harm by the patient, leaving it up to the jury to decide on the issue of foreseeability.

The court held that the psychiatrist had a “special relationship” with the victims, because he had a duty to exercise reasonable care to act, consistent with the standards of the mental health profession, in order to protect the foreseeable victims.

The court reasoned that some ability to control the patient’s conduct is sufficient for the “special relationship” and the consequent duty of care to exist, writing: “We find that absolute control is unnecessary, and the actions available to mental health professionals, even in the outpatient setting, weigh in favor of imposing a duty.” The court also noted that a psychiatrist’s obligation to protect third parties against patients’ violence would normally set aside confidentiality and yield to greater societal interests.

The vexing issue of compromising confidentiality in the name of protecting public safety had its genesis in the famous Tarasoff v. Regents of University of California case.2

In Tarasoff, the California court imposed a legal duty on a college psychologist to warn an intended victim of harm, even though that meant breaching confidentiality in a professional relationship. A jilted patient had confided in the university psychologist his intention to kill his ex-girlfriend. The information, though shared with campus security, was not released to the intended victim, whom the patient stabbed to death 2 months later.

The court reasoned that the protection of public safety was more important than the sanctity of the doctor-patient confidentiality relationship, pointing out: “We recognize the public interest in supporting effective treatment of mental illness and in protecting the rights of patients to privacy and the consequent public importance of safeguarding the confidential character of psychotherapeutic communication. Against this interest, however, we must weigh the public interest in safety from violent assault. ... In this risk-infested society, we can hardly tolerate the further exposure to danger that would result from a concealed knowledge of the therapist that his patient was lethal.”

Following Tarasoff, it is generally accepted that there is no affirmative duty to warn where there is no readily identifiable victim. In a subsequent case, the same court explained that “the duty to warn depends upon and arises from the existence of a prior threat to a specific identifiable victim. In those instances in which the released offender poses a predictable threat of harm to a named or readily identifiable victim or group of victims who can be effectively warned of the danger, a releasing agent may well be liable for failure to warn such persons. Despite the tragic events underlying the present complaint, plaintiffs’ decedent was not a known, identifiable victim, but rather a member of a large, amorphous public group of potential targets. Under these circumstances, we hold that County had no affirmative duty to warn plaintiffs, the police, the mother of the juvenile offender, or other local parents.”3

Commentators have suggested that such post-Tarasoff cases, coupled with the advent of state statutes that codify Tarasoff, have witnessed a retreat from imposing on clinicians a duty to warn.4 By dispensing with the control and “readily identifiable victim” elements, Volk appears to contradict this perceived trend. Foreseeability may turn out to be the dispositive issue.

Some have speculated whether Volk’s expanded view will apply to other professionals such as a family practitioner or even a school counselor. Physicians who are not experienced in treating mental health patients will do well to promptly refer their unstable patients to a specialist psychiatrist.

Volk can also be read as offering judicial insight into patients who pose a health hazard by insisting on operating a vehicle against medical advice. In its 2012 Code of Medical Ethics, the American Medical Association had this to say: “In situations where clear evidence of substantial driving impairment implies a strong threat to patient and public safety, and where the physician’s advice to discontinue driving privileges is ignored, it is desirable and ethical to notify the department of motor vehicles.”5

That is now replaced in the AMA code with a broader version covering the duty to disclose: “Physicians may disclose personal health information without the specific consent of the patient ... to other third parties situated to mitigate the threat when in the physician’s judgment there is a reasonable probability that: (i) the patient will seriously harm him/herself; or (ii) the patient will inflict serious physical harm on an identifiable individual or individuals.”6

Under Volk, physicians are now more likely to forsake confidentiality in the name of public safety – even in the absence of a readily identifiable potential victim.

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some of the materials have been taken from earlier columns in Internal Medicine News. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

References

1. Volk v. DeMeerleer, 386 P.3d 254 (Wa. 2016).

2. Tarasoff v. Regents of University of California, 551 P.2d 334 (Cal. 1976).

3. Thompson v. County of Alameda, 167 Cal. Rptr. 70, 76 (1980).

4. Behav Sci Law. 2001;19(3):325-43.

5. AMA Code of Medical Ethics [2.24 (3), 2012-2013 ed].

6. AMA Code of Medical Ethics, 2017 ed. [3.2.1 Confidentiality].

Hospital mortality for emergency bowel resection linked to failure to rescue

BALTIMORE – The variation among hospitals in mortality for emergent bowel resection may be explained in part by failure-to-rescue (FTR) rates, according to a study presented at the American Association for Surgery of Trauma annual meeting.

Ambar Mehta, a medical student at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, and a team of colleagues reviewed case data on 105,925 bowel resections that occurred between 2010 and 2013 using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Nationwide Inpatient Sample.

Hospitals included were ranked by mortality for emergency bowel resection with the top quintile representing lowest mortality (1.5%) and bottom quintile representing the highest (14.9%).

Failure to rescue was defined as death after a major postoperative complication, according to Mr. Mehta. Overall failure-to-rescue rates were 9.8-fold higher in the bottom quintile hospitals, compared with those in the top quintile (33.4% vs. 3.4%). Patients studied were majority white (78.9%), female (53.9%), and younger than 65 years (52%).

Although FTR rates were significantly higher in the bottom quintile hospitals, complication rates were comparable (41.6% for bottom vs. 33.3% for top), suggesting that it was not complications per se that drove mortality but other postop factors.

Complications measured were acute renal failure, pulmonary failure, pneumonia, hemorrhage, gastrointestinal bleeding, pulmonary embolism, surgical site infections, and myocardial infarction.

Risk ratios for failure to rescue showed a similar increasing trend in correlation with mortality, with the hospitals in the lowest quintile showing a risk of 13 (P less than .01), compared with a risk of 3.2 (P less than .01) among hospitals in the highest quintile.

Correlation between failure to rescue and mortality was still evident when investigators adjusted analysis to compare hospitals that conducted more than 10 resections annually, causing investigators to suggest a need for changes in resection procedures.

“Our data suggest rates of failure to rescue correlate to rates of hospital mortality and we believe that system-level initiatives such as focusing on teamwork and team culture can reduce nationwide variations in mortality,” said Mr. Mehta.

Discussant Andrew Peitzman, MD, FACS, vice president for Trauma and Surgical Services at the University of Pittsburgh, acknowledged the link between mortality and failure to rescue among bowel resection patients and brought up the question of how to avoid such issues in the first place.

“This study validates the principle that a patient will generally tolerate an operation but not the first complication,” said Dr. Peitzman. “How do we avoid the first complication [and] what do you recommend in our acute care surgery practices and hospital structures to rescue our patients?”

Understanding why the complications happen at all is the first step to preventing them, Mr. Mehta said. Emergency general surgery–specific programs or mentorship programs may be a good start to cutting down on the inherent risk increase of emergent procedures.

Having greater than 20 beds designated to the intensive care unit and having a greater ratio of nursing staff to patients may be other viable solutions, according to a study Mr. Mehta cited; however, he asserted, focusing on team protocols seems to be the most successful course.

When asked by audience members about the idea of regionalizing care, Dr. Mehta said more data would be needed. “Regionalization has definitely shown benefits in a trauma setting,” said Mr. Mehta. “Copying a model of that idea for nontrauma [emergency general surgery] procedures may work, but it would require studies in a multicenter program.”

The study was limited by the use of administrative claims data, including being unable to determine if deaths were caused by a failure to rescue or whether families determined to end care after an initial complication. Investigators were also unable to identify which surgical diagnoses led to the procedure, nor could they adjust for varying hospital resources.

Investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

BALTIMORE – The variation among hospitals in mortality for emergent bowel resection may be explained in part by failure-to-rescue (FTR) rates, according to a study presented at the American Association for Surgery of Trauma annual meeting.

Ambar Mehta, a medical student at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, and a team of colleagues reviewed case data on 105,925 bowel resections that occurred between 2010 and 2013 using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Nationwide Inpatient Sample.

Hospitals included were ranked by mortality for emergency bowel resection with the top quintile representing lowest mortality (1.5%) and bottom quintile representing the highest (14.9%).

Failure to rescue was defined as death after a major postoperative complication, according to Mr. Mehta. Overall failure-to-rescue rates were 9.8-fold higher in the bottom quintile hospitals, compared with those in the top quintile (33.4% vs. 3.4%). Patients studied were majority white (78.9%), female (53.9%), and younger than 65 years (52%).

Although FTR rates were significantly higher in the bottom quintile hospitals, complication rates were comparable (41.6% for bottom vs. 33.3% for top), suggesting that it was not complications per se that drove mortality but other postop factors.

Complications measured were acute renal failure, pulmonary failure, pneumonia, hemorrhage, gastrointestinal bleeding, pulmonary embolism, surgical site infections, and myocardial infarction.

Risk ratios for failure to rescue showed a similar increasing trend in correlation with mortality, with the hospitals in the lowest quintile showing a risk of 13 (P less than .01), compared with a risk of 3.2 (P less than .01) among hospitals in the highest quintile.

Correlation between failure to rescue and mortality was still evident when investigators adjusted analysis to compare hospitals that conducted more than 10 resections annually, causing investigators to suggest a need for changes in resection procedures.

“Our data suggest rates of failure to rescue correlate to rates of hospital mortality and we believe that system-level initiatives such as focusing on teamwork and team culture can reduce nationwide variations in mortality,” said Mr. Mehta.

Discussant Andrew Peitzman, MD, FACS, vice president for Trauma and Surgical Services at the University of Pittsburgh, acknowledged the link between mortality and failure to rescue among bowel resection patients and brought up the question of how to avoid such issues in the first place.

“This study validates the principle that a patient will generally tolerate an operation but not the first complication,” said Dr. Peitzman. “How do we avoid the first complication [and] what do you recommend in our acute care surgery practices and hospital structures to rescue our patients?”

Understanding why the complications happen at all is the first step to preventing them, Mr. Mehta said. Emergency general surgery–specific programs or mentorship programs may be a good start to cutting down on the inherent risk increase of emergent procedures.

Having greater than 20 beds designated to the intensive care unit and having a greater ratio of nursing staff to patients may be other viable solutions, according to a study Mr. Mehta cited; however, he asserted, focusing on team protocols seems to be the most successful course.

When asked by audience members about the idea of regionalizing care, Dr. Mehta said more data would be needed. “Regionalization has definitely shown benefits in a trauma setting,” said Mr. Mehta. “Copying a model of that idea for nontrauma [emergency general surgery] procedures may work, but it would require studies in a multicenter program.”

The study was limited by the use of administrative claims data, including being unable to determine if deaths were caused by a failure to rescue or whether families determined to end care after an initial complication. Investigators were also unable to identify which surgical diagnoses led to the procedure, nor could they adjust for varying hospital resources.

Investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

BALTIMORE – The variation among hospitals in mortality for emergent bowel resection may be explained in part by failure-to-rescue (FTR) rates, according to a study presented at the American Association for Surgery of Trauma annual meeting.

Ambar Mehta, a medical student at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, and a team of colleagues reviewed case data on 105,925 bowel resections that occurred between 2010 and 2013 using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Nationwide Inpatient Sample.

Hospitals included were ranked by mortality for emergency bowel resection with the top quintile representing lowest mortality (1.5%) and bottom quintile representing the highest (14.9%).

Failure to rescue was defined as death after a major postoperative complication, according to Mr. Mehta. Overall failure-to-rescue rates were 9.8-fold higher in the bottom quintile hospitals, compared with those in the top quintile (33.4% vs. 3.4%). Patients studied were majority white (78.9%), female (53.9%), and younger than 65 years (52%).

Although FTR rates were significantly higher in the bottom quintile hospitals, complication rates were comparable (41.6% for bottom vs. 33.3% for top), suggesting that it was not complications per se that drove mortality but other postop factors.

Complications measured were acute renal failure, pulmonary failure, pneumonia, hemorrhage, gastrointestinal bleeding, pulmonary embolism, surgical site infections, and myocardial infarction.

Risk ratios for failure to rescue showed a similar increasing trend in correlation with mortality, with the hospitals in the lowest quintile showing a risk of 13 (P less than .01), compared with a risk of 3.2 (P less than .01) among hospitals in the highest quintile.

Correlation between failure to rescue and mortality was still evident when investigators adjusted analysis to compare hospitals that conducted more than 10 resections annually, causing investigators to suggest a need for changes in resection procedures.

“Our data suggest rates of failure to rescue correlate to rates of hospital mortality and we believe that system-level initiatives such as focusing on teamwork and team culture can reduce nationwide variations in mortality,” said Mr. Mehta.

Discussant Andrew Peitzman, MD, FACS, vice president for Trauma and Surgical Services at the University of Pittsburgh, acknowledged the link between mortality and failure to rescue among bowel resection patients and brought up the question of how to avoid such issues in the first place.

“This study validates the principle that a patient will generally tolerate an operation but not the first complication,” said Dr. Peitzman. “How do we avoid the first complication [and] what do you recommend in our acute care surgery practices and hospital structures to rescue our patients?”

Understanding why the complications happen at all is the first step to preventing them, Mr. Mehta said. Emergency general surgery–specific programs or mentorship programs may be a good start to cutting down on the inherent risk increase of emergent procedures.

Having greater than 20 beds designated to the intensive care unit and having a greater ratio of nursing staff to patients may be other viable solutions, according to a study Mr. Mehta cited; however, he asserted, focusing on team protocols seems to be the most successful course.

When asked by audience members about the idea of regionalizing care, Dr. Mehta said more data would be needed. “Regionalization has definitely shown benefits in a trauma setting,” said Mr. Mehta. “Copying a model of that idea for nontrauma [emergency general surgery] procedures may work, but it would require studies in a multicenter program.”

The study was limited by the use of administrative claims data, including being unable to determine if deaths were caused by a failure to rescue or whether families determined to end care after an initial complication. Investigators were also unable to identify which surgical diagnoses led to the procedure, nor could they adjust for varying hospital resources.

Investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

FROM AAST

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Risk-adjusted failure-to-rescue rates were 9.8 times higher in hospitals with the highest mortality than in those with the lowest (33.4% vs. 3.1%).

Data source: Study of 105,925 bowel resections that occurred between 2010 and 2013 collected from the AHRQ Nationwide Inpatient Sample.

Disclosures: Investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Prehospital tourniquets in civilian settings significantly decreased mortality

BALTIMORE – Prehospital tourniquet use on injured civilians in trauma situations was associated with a nearly sixfold decrease in mortality, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for Surgery of Trauma.

While tourniquets have been an effective tool in military settings, data on successful applications in civilian settings have been scarce.

Dr. Teixeira and his coinvestigators conducted a multicenter, retrospective study of 1,026 peripheral–vascular injury patients admitted to level I trauma centers between January 2011 and December 2016. Among the patients studied, 181 (17.6%) received a tourniquet prior to hospital admission.

A majority of tourniquets were applied to the limbs, with the most common application sites on the arm (49%) and the thigh (29%).Tourniquets were held in place for an average 77 minutes.

Of the patients in the study, 98 (9.6%) underwent an amputation; 35 of these patients had received a tourniquet.

After adjusting for confounding factors, such as age and mechanism of injury, investigators found patients who received tourniquets were nearly six times more likely to survive than were their nontourniquet counterparts (odds ratio, 5.86; 95% confidence interval, 1.41-24.47; P = .015).

While the overall mortality rate among those with a tourniquet – compared with those without a tourniquet – was significantly lower, the comparative mortality rate among amputee patients was not significant, which investigators hypothesized could be because of the smaller number of patients in this subgroup.

Additionally, patients who did not receive a tourniquet had lower injury severity scores, had better vital signs, and needed less blood, according to investigators.

The findings of this study mirror what many military medical professionals have historically, and adamantly, supported, according to discussant Jay J. Doucet, MD, FACS, medical director for the surgical intensive care unit at the University of California San Diego Medical Center and a former combat surgeon.

“The medical lessons on our battlefields that hold such great promise have to be carefully relearned, brought home, and fearlessly applied here,” said Dr. Doucet. “I have yet to meet an employed military surgeon who does not believe the tourniquet is an indispensable tool.” While Dr. Doucet did acknowledge the benefit of tourniquets outside military use and addressed the need for increased implementation among civilian hospitals, he did pose a query about the mortality rate that investigators had found.

“The no-tourniquet group has an adjusted odds of death at a rate that is 5.86 times higher, yet they had better vitals, needed less blood, had lower [injury severity scores], had less head injury, fewer traumatic amputations, and fewer complications,” said Dr. Doucet. “So why do they die?”

Investigators were not able to pinpoint the cause of death among patients because of the limitations of their study; however, Dr. Teixeira and his colleagues were able to determine the presence of cardiac complications, pulmonary complications, and acute kidney injury, none of which had a significantly different presence between the two study groups.

The data gathered from this study are strong enough to support the use of tourniquets in civilian situations, asserted Dr. Teixeira, which means the next hurdle is to integrate it into the health system.

“What’s important from our perspective as leaders of this issue is what we are doing to increase the rate [of tourniquet use],” said Dr. Teixeira. “I think one of the important things is the Stop the Bleed program, [in which] we are actually teaching the Austin police department, and we are trying to increase the use of the tourniquet and demonstrate its importance.”

Investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

BALTIMORE – Prehospital tourniquet use on injured civilians in trauma situations was associated with a nearly sixfold decrease in mortality, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for Surgery of Trauma.

While tourniquets have been an effective tool in military settings, data on successful applications in civilian settings have been scarce.

Dr. Teixeira and his coinvestigators conducted a multicenter, retrospective study of 1,026 peripheral–vascular injury patients admitted to level I trauma centers between January 2011 and December 2016. Among the patients studied, 181 (17.6%) received a tourniquet prior to hospital admission.

A majority of tourniquets were applied to the limbs, with the most common application sites on the arm (49%) and the thigh (29%).Tourniquets were held in place for an average 77 minutes.

Of the patients in the study, 98 (9.6%) underwent an amputation; 35 of these patients had received a tourniquet.

After adjusting for confounding factors, such as age and mechanism of injury, investigators found patients who received tourniquets were nearly six times more likely to survive than were their nontourniquet counterparts (odds ratio, 5.86; 95% confidence interval, 1.41-24.47; P = .015).

While the overall mortality rate among those with a tourniquet – compared with those without a tourniquet – was significantly lower, the comparative mortality rate among amputee patients was not significant, which investigators hypothesized could be because of the smaller number of patients in this subgroup.

Additionally, patients who did not receive a tourniquet had lower injury severity scores, had better vital signs, and needed less blood, according to investigators.

The findings of this study mirror what many military medical professionals have historically, and adamantly, supported, according to discussant Jay J. Doucet, MD, FACS, medical director for the surgical intensive care unit at the University of California San Diego Medical Center and a former combat surgeon.

“The medical lessons on our battlefields that hold such great promise have to be carefully relearned, brought home, and fearlessly applied here,” said Dr. Doucet. “I have yet to meet an employed military surgeon who does not believe the tourniquet is an indispensable tool.” While Dr. Doucet did acknowledge the benefit of tourniquets outside military use and addressed the need for increased implementation among civilian hospitals, he did pose a query about the mortality rate that investigators had found.

“The no-tourniquet group has an adjusted odds of death at a rate that is 5.86 times higher, yet they had better vitals, needed less blood, had lower [injury severity scores], had less head injury, fewer traumatic amputations, and fewer complications,” said Dr. Doucet. “So why do they die?”

Investigators were not able to pinpoint the cause of death among patients because of the limitations of their study; however, Dr. Teixeira and his colleagues were able to determine the presence of cardiac complications, pulmonary complications, and acute kidney injury, none of which had a significantly different presence between the two study groups.

The data gathered from this study are strong enough to support the use of tourniquets in civilian situations, asserted Dr. Teixeira, which means the next hurdle is to integrate it into the health system.

“What’s important from our perspective as leaders of this issue is what we are doing to increase the rate [of tourniquet use],” said Dr. Teixeira. “I think one of the important things is the Stop the Bleed program, [in which] we are actually teaching the Austin police department, and we are trying to increase the use of the tourniquet and demonstrate its importance.”

Investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

BALTIMORE – Prehospital tourniquet use on injured civilians in trauma situations was associated with a nearly sixfold decrease in mortality, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for Surgery of Trauma.

While tourniquets have been an effective tool in military settings, data on successful applications in civilian settings have been scarce.

Dr. Teixeira and his coinvestigators conducted a multicenter, retrospective study of 1,026 peripheral–vascular injury patients admitted to level I trauma centers between January 2011 and December 2016. Among the patients studied, 181 (17.6%) received a tourniquet prior to hospital admission.

A majority of tourniquets were applied to the limbs, with the most common application sites on the arm (49%) and the thigh (29%).Tourniquets were held in place for an average 77 minutes.

Of the patients in the study, 98 (9.6%) underwent an amputation; 35 of these patients had received a tourniquet.

After adjusting for confounding factors, such as age and mechanism of injury, investigators found patients who received tourniquets were nearly six times more likely to survive than were their nontourniquet counterparts (odds ratio, 5.86; 95% confidence interval, 1.41-24.47; P = .015).

While the overall mortality rate among those with a tourniquet – compared with those without a tourniquet – was significantly lower, the comparative mortality rate among amputee patients was not significant, which investigators hypothesized could be because of the smaller number of patients in this subgroup.

Additionally, patients who did not receive a tourniquet had lower injury severity scores, had better vital signs, and needed less blood, according to investigators.

The findings of this study mirror what many military medical professionals have historically, and adamantly, supported, according to discussant Jay J. Doucet, MD, FACS, medical director for the surgical intensive care unit at the University of California San Diego Medical Center and a former combat surgeon.

“The medical lessons on our battlefields that hold such great promise have to be carefully relearned, brought home, and fearlessly applied here,” said Dr. Doucet. “I have yet to meet an employed military surgeon who does not believe the tourniquet is an indispensable tool.” While Dr. Doucet did acknowledge the benefit of tourniquets outside military use and addressed the need for increased implementation among civilian hospitals, he did pose a query about the mortality rate that investigators had found.

“The no-tourniquet group has an adjusted odds of death at a rate that is 5.86 times higher, yet they had better vitals, needed less blood, had lower [injury severity scores], had less head injury, fewer traumatic amputations, and fewer complications,” said Dr. Doucet. “So why do they die?”

Investigators were not able to pinpoint the cause of death among patients because of the limitations of their study; however, Dr. Teixeira and his colleagues were able to determine the presence of cardiac complications, pulmonary complications, and acute kidney injury, none of which had a significantly different presence between the two study groups.

The data gathered from this study are strong enough to support the use of tourniquets in civilian situations, asserted Dr. Teixeira, which means the next hurdle is to integrate it into the health system.

“What’s important from our perspective as leaders of this issue is what we are doing to increase the rate [of tourniquet use],” said Dr. Teixeira. “I think one of the important things is the Stop the Bleed program, [in which] we are actually teaching the Austin police department, and we are trying to increase the use of the tourniquet and demonstrate its importance.”

Investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

At the AAST Annual Meeting

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Patients who were given a prehospital tourniquet were associated with a survival odds ratio nearly sixfold higher than those without (odds ratio, 5.86; 95% confidence interval, 1.41-24.47; P = .015).

Data source: Multicenter retrospective study of 1,026 patients with peripheral vascular injuries admitted to a level I trauma facility between January 2011 and December 2016.

Disclosures: Investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

HCA is the country’s highest-volume health system

HCA of Nashville, Tenn., had more discharges in 2016 than any other health system in the United States, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.