User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

ACOG updates guidance on pelvic organ prolapse

Using polypropylene mesh to augment surgical repair of anterior vaginal wall prolapse improves anatomic and some subjective outcomes, compared with native tissue repair, but it also comes with increased morbidity, according to new guidance from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

(POP) to incorporate recent systematic review evidence.

When using polypropylene mesh for anterior POP repair, 11% of patients develop mesh erosion, of which 7% require surgical correction, according to the updated practice bulletin (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e234-50).

“Referral to an obstetrician-gynecologist with appropriate training and experience, such as a female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery specialist, is recommended for surgical treatment of prolapse mesh complications,” ACOG and AUGS wrote.

The practice bulletin updates the recommendations on mesh based on a recent systematic review and meta-analysis that concluded that biological graft repair and absorbable mesh offered minimal benefits compared with native tissue repair, and did not significantly reduce rates of prolapse awareness or repeat surgery (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Nov 30;11:CD004014).

Porcine dermis graft, which was used in most of the studies, did not significantly reduce rates of anterior prolapse recurrence compared with native tissue repair. Use of polypropylene mesh also tends to prolong operating times and causes more blood loss than native tissue anterior repair, and is associated with an elevated combined risk of stress urinary incontinence, mesh erosion, and repeat surgery for prolapse, the review concluded.

“Uterosacral and sacrospinous ligament suspension for apical POP with native tissue are equally effective surgical treatments of POP, with comparable anatomic, functional, and adverse outcomes,” the authors wrote in the practice bulletin.

Neither synthetic mesh nor biologic grafts improve outcomes of transvaginal repair of posterior vaginal wall prolapse, they added. As an alternative to surgery, most women can be successfully fitted with a pessary and clinicians should offer them this option, the practice bulletin stated. In up to 9% of cases, pessaries cause local devascularization or erosion, in which case they should be removed for 2-4 weeks while the patient undergoes local estrogen therapy.

Although POP is common and benign, symptomatic cases undermine quality of life by causing vaginal bulge and pressure and problems voiding, defecating, and during sexual activity. Consequently, about 300,000 women in the United States undergo surgery for POP every year. By 2050, population aging in the United States will lead to about a 50% rise in the number of women with POP, according to the practice bulletin.

Using polypropylene mesh to augment surgical repair of anterior vaginal wall prolapse improves anatomic and some subjective outcomes, compared with native tissue repair, but it also comes with increased morbidity, according to new guidance from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

(POP) to incorporate recent systematic review evidence.

When using polypropylene mesh for anterior POP repair, 11% of patients develop mesh erosion, of which 7% require surgical correction, according to the updated practice bulletin (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e234-50).

“Referral to an obstetrician-gynecologist with appropriate training and experience, such as a female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery specialist, is recommended for surgical treatment of prolapse mesh complications,” ACOG and AUGS wrote.

The practice bulletin updates the recommendations on mesh based on a recent systematic review and meta-analysis that concluded that biological graft repair and absorbable mesh offered minimal benefits compared with native tissue repair, and did not significantly reduce rates of prolapse awareness or repeat surgery (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Nov 30;11:CD004014).

Porcine dermis graft, which was used in most of the studies, did not significantly reduce rates of anterior prolapse recurrence compared with native tissue repair. Use of polypropylene mesh also tends to prolong operating times and causes more blood loss than native tissue anterior repair, and is associated with an elevated combined risk of stress urinary incontinence, mesh erosion, and repeat surgery for prolapse, the review concluded.

“Uterosacral and sacrospinous ligament suspension for apical POP with native tissue are equally effective surgical treatments of POP, with comparable anatomic, functional, and adverse outcomes,” the authors wrote in the practice bulletin.

Neither synthetic mesh nor biologic grafts improve outcomes of transvaginal repair of posterior vaginal wall prolapse, they added. As an alternative to surgery, most women can be successfully fitted with a pessary and clinicians should offer them this option, the practice bulletin stated. In up to 9% of cases, pessaries cause local devascularization or erosion, in which case they should be removed for 2-4 weeks while the patient undergoes local estrogen therapy.

Although POP is common and benign, symptomatic cases undermine quality of life by causing vaginal bulge and pressure and problems voiding, defecating, and during sexual activity. Consequently, about 300,000 women in the United States undergo surgery for POP every year. By 2050, population aging in the United States will lead to about a 50% rise in the number of women with POP, according to the practice bulletin.

Using polypropylene mesh to augment surgical repair of anterior vaginal wall prolapse improves anatomic and some subjective outcomes, compared with native tissue repair, but it also comes with increased morbidity, according to new guidance from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

(POP) to incorporate recent systematic review evidence.

When using polypropylene mesh for anterior POP repair, 11% of patients develop mesh erosion, of which 7% require surgical correction, according to the updated practice bulletin (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e234-50).

“Referral to an obstetrician-gynecologist with appropriate training and experience, such as a female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery specialist, is recommended for surgical treatment of prolapse mesh complications,” ACOG and AUGS wrote.

The practice bulletin updates the recommendations on mesh based on a recent systematic review and meta-analysis that concluded that biological graft repair and absorbable mesh offered minimal benefits compared with native tissue repair, and did not significantly reduce rates of prolapse awareness or repeat surgery (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Nov 30;11:CD004014).

Porcine dermis graft, which was used in most of the studies, did not significantly reduce rates of anterior prolapse recurrence compared with native tissue repair. Use of polypropylene mesh also tends to prolong operating times and causes more blood loss than native tissue anterior repair, and is associated with an elevated combined risk of stress urinary incontinence, mesh erosion, and repeat surgery for prolapse, the review concluded.

“Uterosacral and sacrospinous ligament suspension for apical POP with native tissue are equally effective surgical treatments of POP, with comparable anatomic, functional, and adverse outcomes,” the authors wrote in the practice bulletin.

Neither synthetic mesh nor biologic grafts improve outcomes of transvaginal repair of posterior vaginal wall prolapse, they added. As an alternative to surgery, most women can be successfully fitted with a pessary and clinicians should offer them this option, the practice bulletin stated. In up to 9% of cases, pessaries cause local devascularization or erosion, in which case they should be removed for 2-4 weeks while the patient undergoes local estrogen therapy.

Although POP is common and benign, symptomatic cases undermine quality of life by causing vaginal bulge and pressure and problems voiding, defecating, and during sexual activity. Consequently, about 300,000 women in the United States undergo surgery for POP every year. By 2050, population aging in the United States will lead to about a 50% rise in the number of women with POP, according to the practice bulletin.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Use of opioids, SSRIs linked to increased fracture risk in RA

SAN DIEGO – The use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and opioids was associated with an increased osteoporotic fracture risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, results from an analysis of national data showed.

“Osteoporotic fractures are one of the important causes of disability, health-related costs, and mortality in RA, with substantially higher complication and mortality rates than the general population,” study author Gulsen Ozen, MD, said in an interview prior to the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. “Given the burden of osteoporotic fractures and the suboptimal osteoporosis care, identifying the factors associated with fracture risk in RA patients is of paramount importance.”

During a median follow-up of nearly 6 years, 863 patients (7.8%) sustained osteoporotic fractures. Compared with patients who did not develop fractures, those who did were significantly older, had higher disease duration and activity, glucocorticoid use, comorbidity and FRAX, a fracture risk assessment tool, scores at baseline. After adjusting for sociodemographics, comorbidities, body mass index, fracture risk by FRAX, and RA severity measures, the researchers found a significant risk of osteoporotic fractures with use of opioids of any strength (weak agents, hazard ratio, 1.45; strong agents, HR, 1.79; P less than .001 for both), SSRI use (HR, 1.35; P = .003), and glucocorticoid use of 3 months or longer at a dose of at least 7.5 mg per day (HR, 1.74; P less than .05). Osteoporotic fracture risk increase started even after 1-30 days of opioid use (HR, 1.96; P less than .001), whereas SSRI-associated risk increase started after 3 months of use (HR, 1.42; P = .054). No significant association with fracture risk was observed with the use of other disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, statins, antidepressants, proton pump inhibitors, NSAIDs, anticonvulsants, and antipsychotics.

“One of the first surprising findings was that almost 40% of the RA patients older than 40 years of age were at least once exposed to opioid analgesics,” said Dr. Ozen, who is a research fellow in the division of immunology and rheumatology at the medical center. “Another surprising finding was that even very short-term (1-30 days) use of opioids was associated with increased fracture risk.” She went on to note that careful and regular reviewing of patient medications “is an essential part of the RA patient care, as the use of medications not indicated anymore brings harm rather than a benefit. The most well-known example for this is glucocorticoid use. This is valid for all medications, too. Therefore, we hope that our findings provide more awareness about osteoporotic fractures and associated risk factors in RA patients.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its observational design. “Additionally, fracture and the level of the trauma in our cohort were reported by patients,” she said. “Therefore, there might be some misclassification of fractures as osteoporotic fractures. Lastly, we did not have detailed data regarding fall risk, which might explain the associations we observed with opioids and potentially, SSRIs.”

Dr. Ozen reported having no disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and opioids was associated with an increased osteoporotic fracture risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, results from an analysis of national data showed.

“Osteoporotic fractures are one of the important causes of disability, health-related costs, and mortality in RA, with substantially higher complication and mortality rates than the general population,” study author Gulsen Ozen, MD, said in an interview prior to the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. “Given the burden of osteoporotic fractures and the suboptimal osteoporosis care, identifying the factors associated with fracture risk in RA patients is of paramount importance.”

During a median follow-up of nearly 6 years, 863 patients (7.8%) sustained osteoporotic fractures. Compared with patients who did not develop fractures, those who did were significantly older, had higher disease duration and activity, glucocorticoid use, comorbidity and FRAX, a fracture risk assessment tool, scores at baseline. After adjusting for sociodemographics, comorbidities, body mass index, fracture risk by FRAX, and RA severity measures, the researchers found a significant risk of osteoporotic fractures with use of opioids of any strength (weak agents, hazard ratio, 1.45; strong agents, HR, 1.79; P less than .001 for both), SSRI use (HR, 1.35; P = .003), and glucocorticoid use of 3 months or longer at a dose of at least 7.5 mg per day (HR, 1.74; P less than .05). Osteoporotic fracture risk increase started even after 1-30 days of opioid use (HR, 1.96; P less than .001), whereas SSRI-associated risk increase started after 3 months of use (HR, 1.42; P = .054). No significant association with fracture risk was observed with the use of other disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, statins, antidepressants, proton pump inhibitors, NSAIDs, anticonvulsants, and antipsychotics.

“One of the first surprising findings was that almost 40% of the RA patients older than 40 years of age were at least once exposed to opioid analgesics,” said Dr. Ozen, who is a research fellow in the division of immunology and rheumatology at the medical center. “Another surprising finding was that even very short-term (1-30 days) use of opioids was associated with increased fracture risk.” She went on to note that careful and regular reviewing of patient medications “is an essential part of the RA patient care, as the use of medications not indicated anymore brings harm rather than a benefit. The most well-known example for this is glucocorticoid use. This is valid for all medications, too. Therefore, we hope that our findings provide more awareness about osteoporotic fractures and associated risk factors in RA patients.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its observational design. “Additionally, fracture and the level of the trauma in our cohort were reported by patients,” she said. “Therefore, there might be some misclassification of fractures as osteoporotic fractures. Lastly, we did not have detailed data regarding fall risk, which might explain the associations we observed with opioids and potentially, SSRIs.”

Dr. Ozen reported having no disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and opioids was associated with an increased osteoporotic fracture risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, results from an analysis of national data showed.

“Osteoporotic fractures are one of the important causes of disability, health-related costs, and mortality in RA, with substantially higher complication and mortality rates than the general population,” study author Gulsen Ozen, MD, said in an interview prior to the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. “Given the burden of osteoporotic fractures and the suboptimal osteoporosis care, identifying the factors associated with fracture risk in RA patients is of paramount importance.”

During a median follow-up of nearly 6 years, 863 patients (7.8%) sustained osteoporotic fractures. Compared with patients who did not develop fractures, those who did were significantly older, had higher disease duration and activity, glucocorticoid use, comorbidity and FRAX, a fracture risk assessment tool, scores at baseline. After adjusting for sociodemographics, comorbidities, body mass index, fracture risk by FRAX, and RA severity measures, the researchers found a significant risk of osteoporotic fractures with use of opioids of any strength (weak agents, hazard ratio, 1.45; strong agents, HR, 1.79; P less than .001 for both), SSRI use (HR, 1.35; P = .003), and glucocorticoid use of 3 months or longer at a dose of at least 7.5 mg per day (HR, 1.74; P less than .05). Osteoporotic fracture risk increase started even after 1-30 days of opioid use (HR, 1.96; P less than .001), whereas SSRI-associated risk increase started after 3 months of use (HR, 1.42; P = .054). No significant association with fracture risk was observed with the use of other disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, statins, antidepressants, proton pump inhibitors, NSAIDs, anticonvulsants, and antipsychotics.

“One of the first surprising findings was that almost 40% of the RA patients older than 40 years of age were at least once exposed to opioid analgesics,” said Dr. Ozen, who is a research fellow in the division of immunology and rheumatology at the medical center. “Another surprising finding was that even very short-term (1-30 days) use of opioids was associated with increased fracture risk.” She went on to note that careful and regular reviewing of patient medications “is an essential part of the RA patient care, as the use of medications not indicated anymore brings harm rather than a benefit. The most well-known example for this is glucocorticoid use. This is valid for all medications, too. Therefore, we hope that our findings provide more awareness about osteoporotic fractures and associated risk factors in RA patients.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its observational design. “Additionally, fracture and the level of the trauma in our cohort were reported by patients,” she said. “Therefore, there might be some misclassification of fractures as osteoporotic fractures. Lastly, we did not have detailed data regarding fall risk, which might explain the associations we observed with opioids and potentially, SSRIs.”

Dr. Ozen reported having no disclosures.

AT ACR 2017

Key clinical point: When managing with opioids, even in the short-term, clinicians should be aware of the fracture risk.

Major finding: In patients with RA, concomitant use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors was associated with an increased risk of osteoporotic fracture (HR, 1.35; P = .003), as was opioid use (HR, 1.45 and HR, 1.79) for weak and strong agents, respectively; P less than .001 for both).

Study details: An observational study of 11,049 patients from the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases.

Disclosures: Dr. Ozen reported having no disclosures.

Seven days of opioids adequate for most hernia and other general surgery procedures

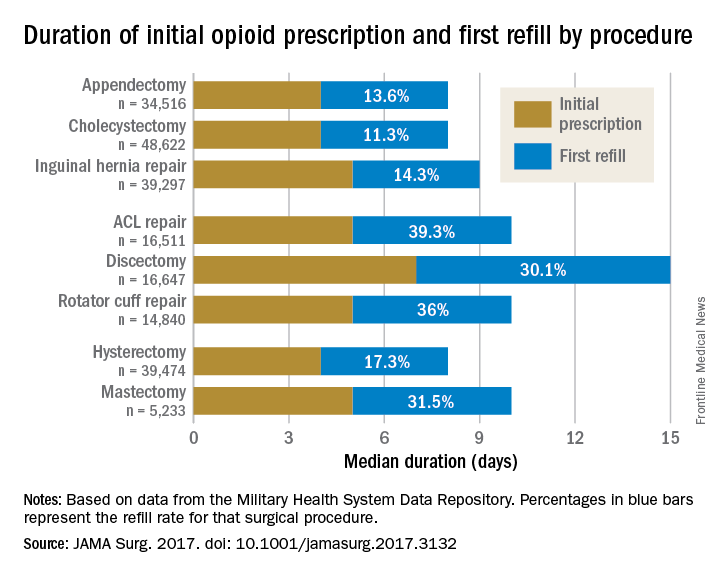

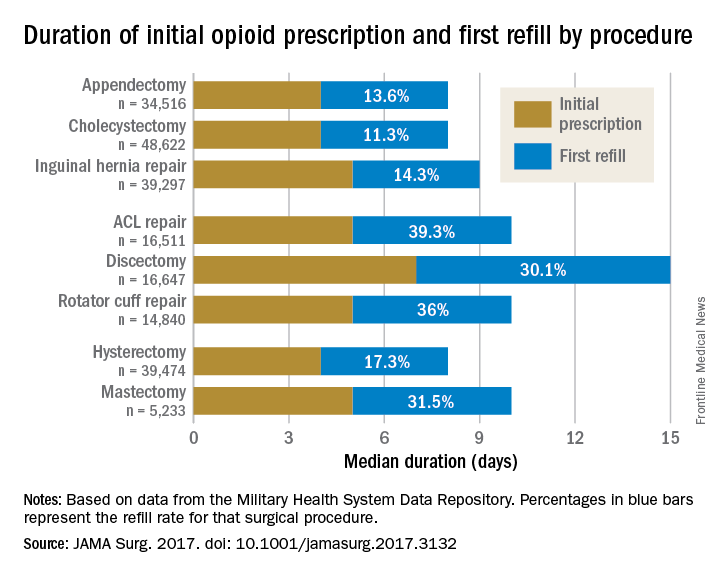

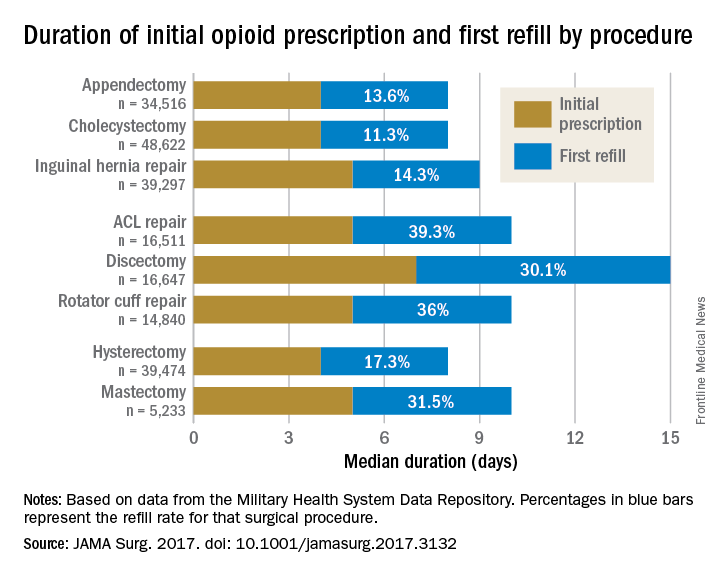

A 7-day limit on the initial opioid prescription may be sufficient for many common general surgery procedures, including hernia surgery and gynecologic procedures, findings of a large retrospective study suggest.

Rebecca E. Scully, MD, of the Center for Surgery and Public Health at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and her associates examined opioid pain medication prescriptions and refills from records of the Military Health System Data Repository and the TRICARE insurance program of 215,140 opioid-naive patients. These patients were aged 18-64 years who underwent either cholecystectomy, appendectomy, inguinal hernia repair, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, rotator cuff tear repair, discectomy, mastectomy, or hysterectomy (JAMA Surg. 2017. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.3132). Only 20% of the covered individuals are active members of the U.S. military. The mean age was 40 years; 50% were male, and 60% were white.

For appendectomy, cholecystectomy, and hysterectomy, the prescription was a median 4 days. For inguinal hernia repair, anterior cruciate ligament repair, rotator cuff repair, and mastectomy, the initial prescription was for 5 days. For discectomy, the median was 7 days.

Refill rates were the least at 11.3% for cholecystectomy and the most at 39.3% after anterior cruciate ligament repair. The time after the initial prescription until a refill was a median 6 days for appendectomy, cholecystectomy, and inguinal hernia repair, compared with a median 10 days for discectomy. The median duration of a refill prescription was 4 days for appendectomy, cholecystectomy, hernia repair, and hysterectomy versus 8 days for discectomy.

“Although 7 days appears to be more than adequate for many patients undergoing common general surgery and gynecologic procedures, prescription lengths likely should be extended to 10 days, particularly after common neurosurgical and musculoskeletal procedures, recognizing that as many as 40% of patients may still require one refill at a 7-day limit,” Dr. Scully and her associates said.

Although this study did not include rates of unused prescriptions or use of nonopioid pain relievers such as acetaminophen or NSAIDs, it did include a large population considered to be nationally representative “in many respects,” and it included a variety of procedures for which patients are commonly discharged to home, the researchers said.

The study was funded in part by the Department of Defense/Henry M. Jackson Foundation. The investigators had no conflict of interests. Adil H. Haider, MD, MPH, is deputy editor of JAMA Surgery, but he was not involved in any of the decisions regarding review of the manuscript or its acceptance.

A 7-day limit on the initial opioid prescription may be sufficient for many common general surgery procedures, including hernia surgery and gynecologic procedures, findings of a large retrospective study suggest.

Rebecca E. Scully, MD, of the Center for Surgery and Public Health at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and her associates examined opioid pain medication prescriptions and refills from records of the Military Health System Data Repository and the TRICARE insurance program of 215,140 opioid-naive patients. These patients were aged 18-64 years who underwent either cholecystectomy, appendectomy, inguinal hernia repair, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, rotator cuff tear repair, discectomy, mastectomy, or hysterectomy (JAMA Surg. 2017. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.3132). Only 20% of the covered individuals are active members of the U.S. military. The mean age was 40 years; 50% were male, and 60% were white.

For appendectomy, cholecystectomy, and hysterectomy, the prescription was a median 4 days. For inguinal hernia repair, anterior cruciate ligament repair, rotator cuff repair, and mastectomy, the initial prescription was for 5 days. For discectomy, the median was 7 days.

Refill rates were the least at 11.3% for cholecystectomy and the most at 39.3% after anterior cruciate ligament repair. The time after the initial prescription until a refill was a median 6 days for appendectomy, cholecystectomy, and inguinal hernia repair, compared with a median 10 days for discectomy. The median duration of a refill prescription was 4 days for appendectomy, cholecystectomy, hernia repair, and hysterectomy versus 8 days for discectomy.

“Although 7 days appears to be more than adequate for many patients undergoing common general surgery and gynecologic procedures, prescription lengths likely should be extended to 10 days, particularly after common neurosurgical and musculoskeletal procedures, recognizing that as many as 40% of patients may still require one refill at a 7-day limit,” Dr. Scully and her associates said.

Although this study did not include rates of unused prescriptions or use of nonopioid pain relievers such as acetaminophen or NSAIDs, it did include a large population considered to be nationally representative “in many respects,” and it included a variety of procedures for which patients are commonly discharged to home, the researchers said.

The study was funded in part by the Department of Defense/Henry M. Jackson Foundation. The investigators had no conflict of interests. Adil H. Haider, MD, MPH, is deputy editor of JAMA Surgery, but he was not involved in any of the decisions regarding review of the manuscript or its acceptance.

A 7-day limit on the initial opioid prescription may be sufficient for many common general surgery procedures, including hernia surgery and gynecologic procedures, findings of a large retrospective study suggest.

Rebecca E. Scully, MD, of the Center for Surgery and Public Health at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and her associates examined opioid pain medication prescriptions and refills from records of the Military Health System Data Repository and the TRICARE insurance program of 215,140 opioid-naive patients. These patients were aged 18-64 years who underwent either cholecystectomy, appendectomy, inguinal hernia repair, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, rotator cuff tear repair, discectomy, mastectomy, or hysterectomy (JAMA Surg. 2017. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.3132). Only 20% of the covered individuals are active members of the U.S. military. The mean age was 40 years; 50% were male, and 60% were white.

For appendectomy, cholecystectomy, and hysterectomy, the prescription was a median 4 days. For inguinal hernia repair, anterior cruciate ligament repair, rotator cuff repair, and mastectomy, the initial prescription was for 5 days. For discectomy, the median was 7 days.

Refill rates were the least at 11.3% for cholecystectomy and the most at 39.3% after anterior cruciate ligament repair. The time after the initial prescription until a refill was a median 6 days for appendectomy, cholecystectomy, and inguinal hernia repair, compared with a median 10 days for discectomy. The median duration of a refill prescription was 4 days for appendectomy, cholecystectomy, hernia repair, and hysterectomy versus 8 days for discectomy.

“Although 7 days appears to be more than adequate for many patients undergoing common general surgery and gynecologic procedures, prescription lengths likely should be extended to 10 days, particularly after common neurosurgical and musculoskeletal procedures, recognizing that as many as 40% of patients may still require one refill at a 7-day limit,” Dr. Scully and her associates said.

Although this study did not include rates of unused prescriptions or use of nonopioid pain relievers such as acetaminophen or NSAIDs, it did include a large population considered to be nationally representative “in many respects,” and it included a variety of procedures for which patients are commonly discharged to home, the researchers said.

The study was funded in part by the Department of Defense/Henry M. Jackson Foundation. The investigators had no conflict of interests. Adil H. Haider, MD, MPH, is deputy editor of JAMA Surgery, but he was not involved in any of the decisions regarding review of the manuscript or its acceptance.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The initial opioid prescription was a median 4 days for appendectomy and cholecystectomy, a median 5 days for inguinal hernia repair and anterior cruciate ligament and rotator cuff repair, and a median 7 days for discectomy.

Data source: A study of opioid prescriptions in 215,140 surgery patients aged 18-64 years.

Disclosures: The study was funded in part by the Department of Defense/Henry M. Jackson Foundation. The investigators had no conflict of interests. Adil H. Haider, MD, MPH, is deputy editor of JAMA Surgery, but he was not involved in any of the decisions regarding review of the manuscript or its acceptance.

Study examines intestinal microbiota role post liver transplant

WASHINGTON – During and after liver transplant, the reaction of the intestinal microbiota may be a critical determinant of outcomes; preliminary data from a cohort study may provide some clarification of what modulates gut microbiota post transplantation and shed light on predictive factors.

Anna-Catrin Uhlemann, MD, PhD, of Columbia University Medical Center, New York, noted that several studies in recent years sought to clarify influences on gut microbiota in people receiving liver transplants, but “there are still a number of important gaps in knowledge, including what exactly is the longitudinal evolution of the host transplant microbiome and what is the predictive value of pre- and early posttransplant dysbiosis on outcomes and complications.”

The researchers collected more than 1,000 samples to screen for colonization by the following MDR organisms: carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), Enterobacteriaceae resistant to third-generation cephalosporins (ESBL), and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE). Over the 1-year follow-up period, 19% (P =.031) of patients had CRE colonization associated with subsequent infection, 41% (P = .003) had ESBL colonization, and 46% (P = .021) had VRE colonization, Dr. Uhlemann said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. The researchers then selected 484 samples for sequencing of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene to determine the composition of gut microbiota.

The study used two indexes to determine the alpha diversity of microbiota: the Chao index to estimate richness and the Shannon diversity index to determine the abundance of species in different settings. “We observed dynamic temporal evolution of alpha diversity and taxa abundance over the 1-year follow-up period,” Dr. Uhlemann said. “The diagnosis, the Child-Pugh class, and changes in perioperative antibiotics were important predictors of posttransplant alpha diversity.”

The study also found that Enterobacteriaceae and enterococci increased post transplant in general and as MDR organisms, and that a patient’s MDR status was an important modulator of the posttransplant microbiome, as was the lack of protective operational taxonomic units (OTUs).

The researchers evaluated the relative abundance of taxa and beta diversity. For example, pretransplant patients with a Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score greater than 25 showed enrichment of Enterobacteriaceae as well as different taxa of the Bacteroidiaceae, while those with MELD scores below 25 showed enrichment of Veillonellaceae. “The significance of this is not clear yet,” Dr. Uhlemann said.

Liver disease severity can also influence gut microbes. Those with Child-Pugh class C disease have the highest numbers in terms of richness and lowest in terms of diversity, Dr. Uhlemann said. “However, at the moment when we are looking at the differential abundance of the taxa, we don’t see quite as clear a pattern, although we noticed in the high group a higher abundance of Bacteroidiaceae,” she said.

Hepatitis B and C patients also presented divergent microbiota profiles. Hepatitis B virus patients “in general are always relatively healthy, and we actually see that these indices are relatively preserved,” Dr. Uhlemann said. “When we look at hepatitis C, however, we see that these patients are starting off quite low and then have an increase in alpha-diversity measures at around month 6.” A subset of patients with alcoholic liver disease also didn’t reach higher Chao and Shannon levels until 6 months after transplant.

“We also find that adjustment of periodic antibiotics for allergy or history of prior infection is significantly associated with a decrease in alpha diversity several months into the posttransplant course,” said Dr. Uhlemann. This is driven by an increase in the abundance of Enterococcaceae and Enterobacteriaceae. “And when we look at MDR colonization as a predictor of alpha diversity, we see that those who have MDR colonization, irrespective of the species, also have the lower alpha diversity.”

The researchers also started to look at pretransplant alpha diversity as a predictor of transplant outcomes, and while the analysis is still in progress, the Shannon indices were significantly different between patients who died and those who survived a year. “There was a trend for significant differences for posttransplant infection and the length of the hospital stay,” Dr. Uhlemann said. “However, we did not see any association with posttransplant ICU readmission, rejection, or VRE complications.”

She added that future analyses are needed to further evaluate the interaction between the clinical comorbidities in the microbiome and vice versa.

Dr. Uhlemann disclosed links to Merck.

WASHINGTON – During and after liver transplant, the reaction of the intestinal microbiota may be a critical determinant of outcomes; preliminary data from a cohort study may provide some clarification of what modulates gut microbiota post transplantation and shed light on predictive factors.

Anna-Catrin Uhlemann, MD, PhD, of Columbia University Medical Center, New York, noted that several studies in recent years sought to clarify influences on gut microbiota in people receiving liver transplants, but “there are still a number of important gaps in knowledge, including what exactly is the longitudinal evolution of the host transplant microbiome and what is the predictive value of pre- and early posttransplant dysbiosis on outcomes and complications.”

The researchers collected more than 1,000 samples to screen for colonization by the following MDR organisms: carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), Enterobacteriaceae resistant to third-generation cephalosporins (ESBL), and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE). Over the 1-year follow-up period, 19% (P =.031) of patients had CRE colonization associated with subsequent infection, 41% (P = .003) had ESBL colonization, and 46% (P = .021) had VRE colonization, Dr. Uhlemann said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. The researchers then selected 484 samples for sequencing of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene to determine the composition of gut microbiota.

The study used two indexes to determine the alpha diversity of microbiota: the Chao index to estimate richness and the Shannon diversity index to determine the abundance of species in different settings. “We observed dynamic temporal evolution of alpha diversity and taxa abundance over the 1-year follow-up period,” Dr. Uhlemann said. “The diagnosis, the Child-Pugh class, and changes in perioperative antibiotics were important predictors of posttransplant alpha diversity.”

The study also found that Enterobacteriaceae and enterococci increased post transplant in general and as MDR organisms, and that a patient’s MDR status was an important modulator of the posttransplant microbiome, as was the lack of protective operational taxonomic units (OTUs).

The researchers evaluated the relative abundance of taxa and beta diversity. For example, pretransplant patients with a Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score greater than 25 showed enrichment of Enterobacteriaceae as well as different taxa of the Bacteroidiaceae, while those with MELD scores below 25 showed enrichment of Veillonellaceae. “The significance of this is not clear yet,” Dr. Uhlemann said.

Liver disease severity can also influence gut microbes. Those with Child-Pugh class C disease have the highest numbers in terms of richness and lowest in terms of diversity, Dr. Uhlemann said. “However, at the moment when we are looking at the differential abundance of the taxa, we don’t see quite as clear a pattern, although we noticed in the high group a higher abundance of Bacteroidiaceae,” she said.

Hepatitis B and C patients also presented divergent microbiota profiles. Hepatitis B virus patients “in general are always relatively healthy, and we actually see that these indices are relatively preserved,” Dr. Uhlemann said. “When we look at hepatitis C, however, we see that these patients are starting off quite low and then have an increase in alpha-diversity measures at around month 6.” A subset of patients with alcoholic liver disease also didn’t reach higher Chao and Shannon levels until 6 months after transplant.

“We also find that adjustment of periodic antibiotics for allergy or history of prior infection is significantly associated with a decrease in alpha diversity several months into the posttransplant course,” said Dr. Uhlemann. This is driven by an increase in the abundance of Enterococcaceae and Enterobacteriaceae. “And when we look at MDR colonization as a predictor of alpha diversity, we see that those who have MDR colonization, irrespective of the species, also have the lower alpha diversity.”

The researchers also started to look at pretransplant alpha diversity as a predictor of transplant outcomes, and while the analysis is still in progress, the Shannon indices were significantly different between patients who died and those who survived a year. “There was a trend for significant differences for posttransplant infection and the length of the hospital stay,” Dr. Uhlemann said. “However, we did not see any association with posttransplant ICU readmission, rejection, or VRE complications.”

She added that future analyses are needed to further evaluate the interaction between the clinical comorbidities in the microbiome and vice versa.

Dr. Uhlemann disclosed links to Merck.

WASHINGTON – During and after liver transplant, the reaction of the intestinal microbiota may be a critical determinant of outcomes; preliminary data from a cohort study may provide some clarification of what modulates gut microbiota post transplantation and shed light on predictive factors.

Anna-Catrin Uhlemann, MD, PhD, of Columbia University Medical Center, New York, noted that several studies in recent years sought to clarify influences on gut microbiota in people receiving liver transplants, but “there are still a number of important gaps in knowledge, including what exactly is the longitudinal evolution of the host transplant microbiome and what is the predictive value of pre- and early posttransplant dysbiosis on outcomes and complications.”

The researchers collected more than 1,000 samples to screen for colonization by the following MDR organisms: carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), Enterobacteriaceae resistant to third-generation cephalosporins (ESBL), and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE). Over the 1-year follow-up period, 19% (P =.031) of patients had CRE colonization associated with subsequent infection, 41% (P = .003) had ESBL colonization, and 46% (P = .021) had VRE colonization, Dr. Uhlemann said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. The researchers then selected 484 samples for sequencing of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene to determine the composition of gut microbiota.

The study used two indexes to determine the alpha diversity of microbiota: the Chao index to estimate richness and the Shannon diversity index to determine the abundance of species in different settings. “We observed dynamic temporal evolution of alpha diversity and taxa abundance over the 1-year follow-up period,” Dr. Uhlemann said. “The diagnosis, the Child-Pugh class, and changes in perioperative antibiotics were important predictors of posttransplant alpha diversity.”

The study also found that Enterobacteriaceae and enterococci increased post transplant in general and as MDR organisms, and that a patient’s MDR status was an important modulator of the posttransplant microbiome, as was the lack of protective operational taxonomic units (OTUs).

The researchers evaluated the relative abundance of taxa and beta diversity. For example, pretransplant patients with a Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score greater than 25 showed enrichment of Enterobacteriaceae as well as different taxa of the Bacteroidiaceae, while those with MELD scores below 25 showed enrichment of Veillonellaceae. “The significance of this is not clear yet,” Dr. Uhlemann said.

Liver disease severity can also influence gut microbes. Those with Child-Pugh class C disease have the highest numbers in terms of richness and lowest in terms of diversity, Dr. Uhlemann said. “However, at the moment when we are looking at the differential abundance of the taxa, we don’t see quite as clear a pattern, although we noticed in the high group a higher abundance of Bacteroidiaceae,” she said.

Hepatitis B and C patients also presented divergent microbiota profiles. Hepatitis B virus patients “in general are always relatively healthy, and we actually see that these indices are relatively preserved,” Dr. Uhlemann said. “When we look at hepatitis C, however, we see that these patients are starting off quite low and then have an increase in alpha-diversity measures at around month 6.” A subset of patients with alcoholic liver disease also didn’t reach higher Chao and Shannon levels until 6 months after transplant.

“We also find that adjustment of periodic antibiotics for allergy or history of prior infection is significantly associated with a decrease in alpha diversity several months into the posttransplant course,” said Dr. Uhlemann. This is driven by an increase in the abundance of Enterococcaceae and Enterobacteriaceae. “And when we look at MDR colonization as a predictor of alpha diversity, we see that those who have MDR colonization, irrespective of the species, also have the lower alpha diversity.”

The researchers also started to look at pretransplant alpha diversity as a predictor of transplant outcomes, and while the analysis is still in progress, the Shannon indices were significantly different between patients who died and those who survived a year. “There was a trend for significant differences for posttransplant infection and the length of the hospital stay,” Dr. Uhlemann said. “However, we did not see any association with posttransplant ICU readmission, rejection, or VRE complications.”

She added that future analyses are needed to further evaluate the interaction between the clinical comorbidities in the microbiome and vice versa.

Dr. Uhlemann disclosed links to Merck.

AT THE LIVER MEETING 2017

Key clinical point: The presence or lack of specific modulators of gut microbiota may influence outcomes of liver transplantation.

Major finding: Over a 1-year follow-up period, 19% of patients had colonization with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, 41% had Enterobacteriaceae resistant to third-generation cephalosporins, and 46% had vancomycin-resistant enterococci associated with subsequent infections.

Data source: A prospective longitudinal cohort study of 323 patients, 125 of whom completed 1 year of follow-up.

Disclosures: Dr. Uhlemann disclosed receiving research funding from Merck.

Inside the Las Vegas crisis: Surgeons answered the call

SAN DIEGO– Long before the horrific night of Oct. 1, the three trauma centers in the Las Vegas region were ready for a mass casualty event. It was understood among hospital leaders that the city could be the scene of a disaster that would demand a coordinated response from the city’s health care centers.

Then came the deadliest mass shooting in modern American history, and the extensive preparation turned out to have been well worth the time and effort, according to four trauma surgeons who spoke about the medical response to the massacre during a session at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

The killing spree was unusual in a variety of ways, including the fact that it occurred at a site “that’s almost strategically surrounded by trauma centers,” Dr. Fildes said.

UMC is Nevada’s only level I trauma center, while Sunrise is a level II. St. Rose Dominican, in the neighboring city of Henderson is a level III. Only one other Nevada hospital, in Reno, is a verified trauma center.

While the trauma centers received hundreds of patients, “every hospital in the valley saw patients from this event,” Dr. Fildes said. “There were 22,000 people on scene, and when the shooting started, they extricated themselves and went to safety by one means or another. Some drove home to their neighborhood and sought care there. Some drove until they found an acute care facility, whether it was a trauma center or not. Others were transported by Uber or taxi. The drivers knew where the trauma centers were, and decided where to go based on how the patients looked.”

According to Dr. Fildes, Las Vegas–area hospitals kept in touch with each other by phone, and UMC accepted some transfers from other hospitals. “We were ready for transfers,” he said, “and we expected more than we got.”

The trauma centers faced a variety of challenges from confusion and false reports to overcrowding and a media onslaught.

“We knew there was a strong possibility this would happen where we live, so we practiced this,” said Sean Dort, MD, medical director of the hospital’s trauma center. “We have talked and walked through it.”

Indeed, all hospitals in the Las Vegas area take part in regional disaster drills twice a year, and UMC runs other drills during the year such as an active shooter drill, Dr. Fildes said in an interview.

Together, the three hospitals treated hundreds of patients. Three weeks later, a handful were still inpatients.

In the aftermath, Las Vegas trauma surgeons are focusing on missed opportunities and lessons learned.

Dr. Fildes said more attention needs to be paid to how to handle situations when tides of patients bring themselves to the emergency department. “The issue of self-delivery has to be reconsidered, restudied,” he said, and he suggested that it may be a good idea to equip taxis with bleeding control kits.

He said his hospital heard from a doctor who’d treated patients during the Pulse nightclub massacre in Orlando last year. “One of their lessons learned was to position all gurneys and wheelchairs near the intake triage area,” he said. “We did that, and it improved the movement of patients to areas of the hospital that were matched to the intensity of care that they required.”

At Sunrise, the flood of unidentified patients overwhelmed the hospital’s trauma patient alias system, and some names were repeated. “In the future, I think a better naming system should be employed,” said trauma surgeon Matthew S. Johnson, MD.

To that end, he said, the hospital has begun examining how hurricanes are named.

And when it comes to planning, he said, there’s no room for excuses or resistance. “Everyone knew their role,” he said. “You can’t start figuring this out when it happens. You have to push people through it when they don’t want to do it, and they’re busy.”

Dr. Fildes said that the UMC staff were physically and emotionally exhausted by the ordeal, but proud of what they were able to do for these patients, and that pride carried them through the experience. “We had support from all over the country; people sent banners with hundreds of signatures. Something like 1,100 pizzas were sent to the UMC staff, and dozens and dozens of surgeons from all over the country offered to come help us.”

Dr. Fildes noted that he is not easily surprised given his daily work, but he was impressed by the generosity and courage of the patients in this crisis situation.

He concluded that, “This was all made possible because of planning, training, commitment by staff and ultimately, the bravery of the patients.”

Dr. Dort, Dr. Fildes, Dr. Kuhls, and Dr. Johnson had no relevant financial disclosures.

I was at home and in bed with a book when my phone went off at 10:22 p.m. on that Sunday. It was a text message from one of my fellow residents who was on call at Sunrise: She wrote: “Mass casualty incident. Shooting on the Strip. You have to come now.”

There were multiple blood trails tracking from various parts of the ambulance bay into the ED. Medics were walking from bedside to bedside putting in lines. Two anesthesia attendings were frantically intubating patients. Two nurses were performing chest compressions.

I picked the nearest bed and started assessing patients. I placed 2 endotracheal tubes and black tagged 4 more patients within minutes of my arrival.

In the initial moments in the ER and in the OR, I focused on caring for the patient and blocked out any other thoughts or emotions. There was no time and no room for my horror or my tears.

As I went bedside to bedside in the ER, I was practically chanting in my head “airway, breathing, circulation, vital signs, other injuries.”

In the OR, I was working on controlling intra-abdominal bleeding from multiple sources, and again, my training became something of a mantra in my head. “Pack, control bleeding, assess injuries, repair.”

We saw well over 200 patients from the Route 91 shooting and operated on 95 of them within the first 24 hours.

Dylan Davey, MD, PhD, General Surgery Resident, PGY-4, Sunrise Hospital & Medical Center.

I was at home and in bed with a book when my phone went off at 10:22 p.m. on that Sunday. It was a text message from one of my fellow residents who was on call at Sunrise: She wrote: “Mass casualty incident. Shooting on the Strip. You have to come now.”

There were multiple blood trails tracking from various parts of the ambulance bay into the ED. Medics were walking from bedside to bedside putting in lines. Two anesthesia attendings were frantically intubating patients. Two nurses were performing chest compressions.

I picked the nearest bed and started assessing patients. I placed 2 endotracheal tubes and black tagged 4 more patients within minutes of my arrival.

In the initial moments in the ER and in the OR, I focused on caring for the patient and blocked out any other thoughts or emotions. There was no time and no room for my horror or my tears.

As I went bedside to bedside in the ER, I was practically chanting in my head “airway, breathing, circulation, vital signs, other injuries.”

In the OR, I was working on controlling intra-abdominal bleeding from multiple sources, and again, my training became something of a mantra in my head. “Pack, control bleeding, assess injuries, repair.”

We saw well over 200 patients from the Route 91 shooting and operated on 95 of them within the first 24 hours.

Dylan Davey, MD, PhD, General Surgery Resident, PGY-4, Sunrise Hospital & Medical Center.

I was at home and in bed with a book when my phone went off at 10:22 p.m. on that Sunday. It was a text message from one of my fellow residents who was on call at Sunrise: She wrote: “Mass casualty incident. Shooting on the Strip. You have to come now.”

There were multiple blood trails tracking from various parts of the ambulance bay into the ED. Medics were walking from bedside to bedside putting in lines. Two anesthesia attendings were frantically intubating patients. Two nurses were performing chest compressions.

I picked the nearest bed and started assessing patients. I placed 2 endotracheal tubes and black tagged 4 more patients within minutes of my arrival.

In the initial moments in the ER and in the OR, I focused on caring for the patient and blocked out any other thoughts or emotions. There was no time and no room for my horror or my tears.

As I went bedside to bedside in the ER, I was practically chanting in my head “airway, breathing, circulation, vital signs, other injuries.”

In the OR, I was working on controlling intra-abdominal bleeding from multiple sources, and again, my training became something of a mantra in my head. “Pack, control bleeding, assess injuries, repair.”

We saw well over 200 patients from the Route 91 shooting and operated on 95 of them within the first 24 hours.

Dylan Davey, MD, PhD, General Surgery Resident, PGY-4, Sunrise Hospital & Medical Center.

SAN DIEGO– Long before the horrific night of Oct. 1, the three trauma centers in the Las Vegas region were ready for a mass casualty event. It was understood among hospital leaders that the city could be the scene of a disaster that would demand a coordinated response from the city’s health care centers.

Then came the deadliest mass shooting in modern American history, and the extensive preparation turned out to have been well worth the time and effort, according to four trauma surgeons who spoke about the medical response to the massacre during a session at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

The killing spree was unusual in a variety of ways, including the fact that it occurred at a site “that’s almost strategically surrounded by trauma centers,” Dr. Fildes said.

UMC is Nevada’s only level I trauma center, while Sunrise is a level II. St. Rose Dominican, in the neighboring city of Henderson is a level III. Only one other Nevada hospital, in Reno, is a verified trauma center.

While the trauma centers received hundreds of patients, “every hospital in the valley saw patients from this event,” Dr. Fildes said. “There were 22,000 people on scene, and when the shooting started, they extricated themselves and went to safety by one means or another. Some drove home to their neighborhood and sought care there. Some drove until they found an acute care facility, whether it was a trauma center or not. Others were transported by Uber or taxi. The drivers knew where the trauma centers were, and decided where to go based on how the patients looked.”

According to Dr. Fildes, Las Vegas–area hospitals kept in touch with each other by phone, and UMC accepted some transfers from other hospitals. “We were ready for transfers,” he said, “and we expected more than we got.”

The trauma centers faced a variety of challenges from confusion and false reports to overcrowding and a media onslaught.

“We knew there was a strong possibility this would happen where we live, so we practiced this,” said Sean Dort, MD, medical director of the hospital’s trauma center. “We have talked and walked through it.”

Indeed, all hospitals in the Las Vegas area take part in regional disaster drills twice a year, and UMC runs other drills during the year such as an active shooter drill, Dr. Fildes said in an interview.

Together, the three hospitals treated hundreds of patients. Three weeks later, a handful were still inpatients.

In the aftermath, Las Vegas trauma surgeons are focusing on missed opportunities and lessons learned.

Dr. Fildes said more attention needs to be paid to how to handle situations when tides of patients bring themselves to the emergency department. “The issue of self-delivery has to be reconsidered, restudied,” he said, and he suggested that it may be a good idea to equip taxis with bleeding control kits.

He said his hospital heard from a doctor who’d treated patients during the Pulse nightclub massacre in Orlando last year. “One of their lessons learned was to position all gurneys and wheelchairs near the intake triage area,” he said. “We did that, and it improved the movement of patients to areas of the hospital that were matched to the intensity of care that they required.”

At Sunrise, the flood of unidentified patients overwhelmed the hospital’s trauma patient alias system, and some names were repeated. “In the future, I think a better naming system should be employed,” said trauma surgeon Matthew S. Johnson, MD.

To that end, he said, the hospital has begun examining how hurricanes are named.

And when it comes to planning, he said, there’s no room for excuses or resistance. “Everyone knew their role,” he said. “You can’t start figuring this out when it happens. You have to push people through it when they don’t want to do it, and they’re busy.”

Dr. Fildes said that the UMC staff were physically and emotionally exhausted by the ordeal, but proud of what they were able to do for these patients, and that pride carried them through the experience. “We had support from all over the country; people sent banners with hundreds of signatures. Something like 1,100 pizzas were sent to the UMC staff, and dozens and dozens of surgeons from all over the country offered to come help us.”

Dr. Fildes noted that he is not easily surprised given his daily work, but he was impressed by the generosity and courage of the patients in this crisis situation.

He concluded that, “This was all made possible because of planning, training, commitment by staff and ultimately, the bravery of the patients.”

Dr. Dort, Dr. Fildes, Dr. Kuhls, and Dr. Johnson had no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO– Long before the horrific night of Oct. 1, the three trauma centers in the Las Vegas region were ready for a mass casualty event. It was understood among hospital leaders that the city could be the scene of a disaster that would demand a coordinated response from the city’s health care centers.

Then came the deadliest mass shooting in modern American history, and the extensive preparation turned out to have been well worth the time and effort, according to four trauma surgeons who spoke about the medical response to the massacre during a session at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

The killing spree was unusual in a variety of ways, including the fact that it occurred at a site “that’s almost strategically surrounded by trauma centers,” Dr. Fildes said.

UMC is Nevada’s only level I trauma center, while Sunrise is a level II. St. Rose Dominican, in the neighboring city of Henderson is a level III. Only one other Nevada hospital, in Reno, is a verified trauma center.

While the trauma centers received hundreds of patients, “every hospital in the valley saw patients from this event,” Dr. Fildes said. “There were 22,000 people on scene, and when the shooting started, they extricated themselves and went to safety by one means or another. Some drove home to their neighborhood and sought care there. Some drove until they found an acute care facility, whether it was a trauma center or not. Others were transported by Uber or taxi. The drivers knew where the trauma centers were, and decided where to go based on how the patients looked.”

According to Dr. Fildes, Las Vegas–area hospitals kept in touch with each other by phone, and UMC accepted some transfers from other hospitals. “We were ready for transfers,” he said, “and we expected more than we got.”

The trauma centers faced a variety of challenges from confusion and false reports to overcrowding and a media onslaught.

“We knew there was a strong possibility this would happen where we live, so we practiced this,” said Sean Dort, MD, medical director of the hospital’s trauma center. “We have talked and walked through it.”

Indeed, all hospitals in the Las Vegas area take part in regional disaster drills twice a year, and UMC runs other drills during the year such as an active shooter drill, Dr. Fildes said in an interview.

Together, the three hospitals treated hundreds of patients. Three weeks later, a handful were still inpatients.

In the aftermath, Las Vegas trauma surgeons are focusing on missed opportunities and lessons learned.

Dr. Fildes said more attention needs to be paid to how to handle situations when tides of patients bring themselves to the emergency department. “The issue of self-delivery has to be reconsidered, restudied,” he said, and he suggested that it may be a good idea to equip taxis with bleeding control kits.

He said his hospital heard from a doctor who’d treated patients during the Pulse nightclub massacre in Orlando last year. “One of their lessons learned was to position all gurneys and wheelchairs near the intake triage area,” he said. “We did that, and it improved the movement of patients to areas of the hospital that were matched to the intensity of care that they required.”

At Sunrise, the flood of unidentified patients overwhelmed the hospital’s trauma patient alias system, and some names were repeated. “In the future, I think a better naming system should be employed,” said trauma surgeon Matthew S. Johnson, MD.

To that end, he said, the hospital has begun examining how hurricanes are named.

And when it comes to planning, he said, there’s no room for excuses or resistance. “Everyone knew their role,” he said. “You can’t start figuring this out when it happens. You have to push people through it when they don’t want to do it, and they’re busy.”

Dr. Fildes said that the UMC staff were physically and emotionally exhausted by the ordeal, but proud of what they were able to do for these patients, and that pride carried them through the experience. “We had support from all over the country; people sent banners with hundreds of signatures. Something like 1,100 pizzas were sent to the UMC staff, and dozens and dozens of surgeons from all over the country offered to come help us.”

Dr. Fildes noted that he is not easily surprised given his daily work, but he was impressed by the generosity and courage of the patients in this crisis situation.

He concluded that, “This was all made possible because of planning, training, commitment by staff and ultimately, the bravery of the patients.”

Dr. Dort, Dr. Fildes, Dr. Kuhls, and Dr. Johnson had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

Genotype-guided warfarin dosing reduced adverse events in arthroplasty patients

The difference in the composite endpoint (major bleeding within 30 days, international normalized ratio [INR] of 4 or greater within 30 days, venous thromboembolism within 60 days, or death within 30 days) in the Genetic Informatics Trial of Warfarin to Prevent Deep Vein Thrombosis (GIFT) trial was mainly driven by a significant difference in episodes of elevated INR, reported Brian F. Gage, MD, and his colleagues (JAMA 2017;318[12]:1115-1124. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11469).

A total of 1,597 patients completed the trial. Of 808 patients in the genotype-guided group, 10.8% met one of the endpoints. Of 789 in the clinically guided warfarin dosing group, 14.7% met at least 1 of the endpoints. There were no deaths in the study.

“Widespread use of genotype-guided dosing will depend on reimbursement, regulations, and logistics. Although several commercial platforms for warfarin-related genes have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency, routine genotyping is not yet recommended,” wrote Dr. Gage of Washington University, St. Louis, and his coauthors.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services used its Coverage with Evidence Development program to fund genotyping in this trial and will review the results to determine future coverage, the researchers added.

In GIFT, patients were randomized to an 11-day regimen of warfarin guided either by a clinical algorithm or by their individual genotype. The team tested for four polymorphisms known to affect warfarin metabolism: VKORC1-1639G>A, CYP2C9*2, CYP2C9*3, and CYP4F2 V433M. The treatment goal was an INR of 1.8-2. After 11 days, physicians could administer warfarin according to their own judgment.

The absolute difference of 3.9% in the composite endpoint was largely driven by a 2.8% absolute difference in the rate of an INR of 4 or greater. The rate difference between the two groups was 0.8% for major bleeding, and 0.7% for VTE.

About 41% of the cohort was considered to be at high risk of bleeding complications, and this group accrued the highest benefit from genotype-based dosing. Among them, the composite endpoint was 11.5% compared with 15.2% in the clinical algorithm group – an absolute difference of 3.76%.

The benefit was consistent among black patients, and those with CYP2C9.

By day 90, one VTE had occurred in each group. An intracranial hemorrhage occurred in one patient in the clinically guided group, 2 months after stopping warfarin.

The clinical benefit of genotype-based dosing influenced 90-day outcomes as well, with the composite endpoint occurring in 11% of the genotype group and 15% of the clinically guided group (absolute difference 3.9%).

Among the 1,588 patients who had their percentage of time in the therapeutic range (PTTR) calculated, genotyping improved PTTR time by 3.4% overall. The effect was especially strong from days 4 to 14, when it improved PTTR by 5.7% relative to clinical guidance.

Three other studies have examined the effect of a genotype-based warfarin dosing regimen, Dr. Gage and his coauthors noted: Two found no benefit, and a third found that such guidance improved INR control. GIFT has several advantages over those trials, which the authors said lend credence to its results.

“Compared with previous studies, this trial was larger, used genotype-guided dosing for a longer duration, and incorporated more genes into the dosing algorithm …The longer period of genotype-guided dosing likely prevented cases of supratherapeutic INR that were common in these trials,” they wrote.

Dr. Gage reported no financial disclosures, but several coauthors reported ties with pharmaceutical and imaging companies.

Warfarin is the most commonly used anticoagulant in the world, and a significant cause of emergency department visits and hospitalizations, especially among older patients. Walking the fine line between dosing too little and too much is not an easy task – especially since warfarin response is influenced by diet, comorbidities, interactions with other medications and – as studies over the last 20 years have confirmed – many genetic variants.

Also, the practicality of genotyping every patient who needs anticoagulation therapy must be questioned. Based on the results of GIFT, 26 patients would need to be genotyped to prevent one event, typically an INR of 4 or greater. Although the cost of genotyping continues to decline, health insurers and publicly funded health systems have not yet been convinced that genotype-guided warfarin prescribing is a cost-effective strategy.

The benefits of genotyping would likely be less in patients with atrial fibrillation, for example, as they run a lower risk of VTE than do arthroplasty patients. The GIFT surgeries were all elective, so there was plenty of time to get back genotyping results before starting warfarin. That is a luxury not afforded to many patients in need of anticoagulation.

It’s possible, however, that the benefits of genotyping might be larger in the real world. GIFT was conducted at academic medical centers and used a clinical dosing algorithm as comparator. As a result, adverse event rates were likely lower in the comparison group than would be expected in other clinical settings with less-intense INR monitoring or empirically based initiation regimens.

Still, GIFT’s results are gaining global attention. Based on prepublication results of the GIFT trial, the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC), an international research network that develops consensus recommendations about the use of pharmacogenomic test results, recently published guidelines about genotype-guided dosing for warfarin. The group now recommends using genotype-guided warfarin dosing based on CYP2C9*2, CYP2C9*3, and VKORC1 variants for adult patients of non-African ancestry. It also recommends that patients with combinations of high-risk variants would benefit from an alternative anticoagulant strategy, because of likely greater risks of poor INR control and bleeding.

A single pharmacogenomic test covering many common variants relevant to multiple prescribing decisions over time is far more likely to be a cost-effective approach; however, there is no evidence for this proposition. Until then, it might be simpler and less expensive to use clinical dosing algorithms to reduce the risks of anticoagulation.

Jon D. Emery, PhD, is the Herman Professor of Primary Care Cancer Research at the University of Melbourne and Western Health, Melbourne. He made these remarks in an accompanying editorial (JAMA 2017;318;110-2 doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11465 ).

Warfarin is the most commonly used anticoagulant in the world, and a significant cause of emergency department visits and hospitalizations, especially among older patients. Walking the fine line between dosing too little and too much is not an easy task – especially since warfarin response is influenced by diet, comorbidities, interactions with other medications and – as studies over the last 20 years have confirmed – many genetic variants.

Also, the practicality of genotyping every patient who needs anticoagulation therapy must be questioned. Based on the results of GIFT, 26 patients would need to be genotyped to prevent one event, typically an INR of 4 or greater. Although the cost of genotyping continues to decline, health insurers and publicly funded health systems have not yet been convinced that genotype-guided warfarin prescribing is a cost-effective strategy.

The benefits of genotyping would likely be less in patients with atrial fibrillation, for example, as they run a lower risk of VTE than do arthroplasty patients. The GIFT surgeries were all elective, so there was plenty of time to get back genotyping results before starting warfarin. That is a luxury not afforded to many patients in need of anticoagulation.

It’s possible, however, that the benefits of genotyping might be larger in the real world. GIFT was conducted at academic medical centers and used a clinical dosing algorithm as comparator. As a result, adverse event rates were likely lower in the comparison group than would be expected in other clinical settings with less-intense INR monitoring or empirically based initiation regimens.

Still, GIFT’s results are gaining global attention. Based on prepublication results of the GIFT trial, the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC), an international research network that develops consensus recommendations about the use of pharmacogenomic test results, recently published guidelines about genotype-guided dosing for warfarin. The group now recommends using genotype-guided warfarin dosing based on CYP2C9*2, CYP2C9*3, and VKORC1 variants for adult patients of non-African ancestry. It also recommends that patients with combinations of high-risk variants would benefit from an alternative anticoagulant strategy, because of likely greater risks of poor INR control and bleeding.

A single pharmacogenomic test covering many common variants relevant to multiple prescribing decisions over time is far more likely to be a cost-effective approach; however, there is no evidence for this proposition. Until then, it might be simpler and less expensive to use clinical dosing algorithms to reduce the risks of anticoagulation.

Jon D. Emery, PhD, is the Herman Professor of Primary Care Cancer Research at the University of Melbourne and Western Health, Melbourne. He made these remarks in an accompanying editorial (JAMA 2017;318;110-2 doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11465 ).

Warfarin is the most commonly used anticoagulant in the world, and a significant cause of emergency department visits and hospitalizations, especially among older patients. Walking the fine line between dosing too little and too much is not an easy task – especially since warfarin response is influenced by diet, comorbidities, interactions with other medications and – as studies over the last 20 years have confirmed – many genetic variants.

Also, the practicality of genotyping every patient who needs anticoagulation therapy must be questioned. Based on the results of GIFT, 26 patients would need to be genotyped to prevent one event, typically an INR of 4 or greater. Although the cost of genotyping continues to decline, health insurers and publicly funded health systems have not yet been convinced that genotype-guided warfarin prescribing is a cost-effective strategy.

The benefits of genotyping would likely be less in patients with atrial fibrillation, for example, as they run a lower risk of VTE than do arthroplasty patients. The GIFT surgeries were all elective, so there was plenty of time to get back genotyping results before starting warfarin. That is a luxury not afforded to many patients in need of anticoagulation.

It’s possible, however, that the benefits of genotyping might be larger in the real world. GIFT was conducted at academic medical centers and used a clinical dosing algorithm as comparator. As a result, adverse event rates were likely lower in the comparison group than would be expected in other clinical settings with less-intense INR monitoring or empirically based initiation regimens.

Still, GIFT’s results are gaining global attention. Based on prepublication results of the GIFT trial, the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC), an international research network that develops consensus recommendations about the use of pharmacogenomic test results, recently published guidelines about genotype-guided dosing for warfarin. The group now recommends using genotype-guided warfarin dosing based on CYP2C9*2, CYP2C9*3, and VKORC1 variants for adult patients of non-African ancestry. It also recommends that patients with combinations of high-risk variants would benefit from an alternative anticoagulant strategy, because of likely greater risks of poor INR control and bleeding.

A single pharmacogenomic test covering many common variants relevant to multiple prescribing decisions over time is far more likely to be a cost-effective approach; however, there is no evidence for this proposition. Until then, it might be simpler and less expensive to use clinical dosing algorithms to reduce the risks of anticoagulation.

Jon D. Emery, PhD, is the Herman Professor of Primary Care Cancer Research at the University of Melbourne and Western Health, Melbourne. He made these remarks in an accompanying editorial (JAMA 2017;318;110-2 doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11465 ).

The difference in the composite endpoint (major bleeding within 30 days, international normalized ratio [INR] of 4 or greater within 30 days, venous thromboembolism within 60 days, or death within 30 days) in the Genetic Informatics Trial of Warfarin to Prevent Deep Vein Thrombosis (GIFT) trial was mainly driven by a significant difference in episodes of elevated INR, reported Brian F. Gage, MD, and his colleagues (JAMA 2017;318[12]:1115-1124. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11469).

A total of 1,597 patients completed the trial. Of 808 patients in the genotype-guided group, 10.8% met one of the endpoints. Of 789 in the clinically guided warfarin dosing group, 14.7% met at least 1 of the endpoints. There were no deaths in the study.

“Widespread use of genotype-guided dosing will depend on reimbursement, regulations, and logistics. Although several commercial platforms for warfarin-related genes have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency, routine genotyping is not yet recommended,” wrote Dr. Gage of Washington University, St. Louis, and his coauthors.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services used its Coverage with Evidence Development program to fund genotyping in this trial and will review the results to determine future coverage, the researchers added.

In GIFT, patients were randomized to an 11-day regimen of warfarin guided either by a clinical algorithm or by their individual genotype. The team tested for four polymorphisms known to affect warfarin metabolism: VKORC1-1639G>A, CYP2C9*2, CYP2C9*3, and CYP4F2 V433M. The treatment goal was an INR of 1.8-2. After 11 days, physicians could administer warfarin according to their own judgment.

The absolute difference of 3.9% in the composite endpoint was largely driven by a 2.8% absolute difference in the rate of an INR of 4 or greater. The rate difference between the two groups was 0.8% for major bleeding, and 0.7% for VTE.

About 41% of the cohort was considered to be at high risk of bleeding complications, and this group accrued the highest benefit from genotype-based dosing. Among them, the composite endpoint was 11.5% compared with 15.2% in the clinical algorithm group – an absolute difference of 3.76%.

The benefit was consistent among black patients, and those with CYP2C9.

By day 90, one VTE had occurred in each group. An intracranial hemorrhage occurred in one patient in the clinically guided group, 2 months after stopping warfarin.

The clinical benefit of genotype-based dosing influenced 90-day outcomes as well, with the composite endpoint occurring in 11% of the genotype group and 15% of the clinically guided group (absolute difference 3.9%).

Among the 1,588 patients who had their percentage of time in the therapeutic range (PTTR) calculated, genotyping improved PTTR time by 3.4% overall. The effect was especially strong from days 4 to 14, when it improved PTTR by 5.7% relative to clinical guidance.

Three other studies have examined the effect of a genotype-based warfarin dosing regimen, Dr. Gage and his coauthors noted: Two found no benefit, and a third found that such guidance improved INR control. GIFT has several advantages over those trials, which the authors said lend credence to its results.

“Compared with previous studies, this trial was larger, used genotype-guided dosing for a longer duration, and incorporated more genes into the dosing algorithm …The longer period of genotype-guided dosing likely prevented cases of supratherapeutic INR that were common in these trials,” they wrote.

Dr. Gage reported no financial disclosures, but several coauthors reported ties with pharmaceutical and imaging companies.

The difference in the composite endpoint (major bleeding within 30 days, international normalized ratio [INR] of 4 or greater within 30 days, venous thromboembolism within 60 days, or death within 30 days) in the Genetic Informatics Trial of Warfarin to Prevent Deep Vein Thrombosis (GIFT) trial was mainly driven by a significant difference in episodes of elevated INR, reported Brian F. Gage, MD, and his colleagues (JAMA 2017;318[12]:1115-1124. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11469).

A total of 1,597 patients completed the trial. Of 808 patients in the genotype-guided group, 10.8% met one of the endpoints. Of 789 in the clinically guided warfarin dosing group, 14.7% met at least 1 of the endpoints. There were no deaths in the study.

“Widespread use of genotype-guided dosing will depend on reimbursement, regulations, and logistics. Although several commercial platforms for warfarin-related genes have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency, routine genotyping is not yet recommended,” wrote Dr. Gage of Washington University, St. Louis, and his coauthors.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services used its Coverage with Evidence Development program to fund genotyping in this trial and will review the results to determine future coverage, the researchers added.