User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

Drug-eluting stent edges drug-eluting balloon

SAN FRANCISCO – Treating bare metal stent in-stent restenosis using a drug-eluting stent yielded a significantly larger minimal lumen diameter 1 year later, compared with treatment using a drug-eluting balloon in a study of 189 patients.

A second-generation everolimus-eluting stent bested a paclitaxel-eluting balloon in the primary outcome of the prospective, randomized trial after adjusting for age, smoking history, stenosis, and the presence of diabetes.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The in-segment minimal lumen diameter was 2.36 mm for the 94 patients in the stent group and 2.01 mm for the 95 patients in the balloon group. The in-lesion minimal lumen diameter was 2.44 mm in the stent group and 2.03 mm in the balloon group. Both differences were statistically significant, Dr. Fernando Alfonso and his associates reported at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting.

The rate of restenosis (greater than 50% lumen diameter narrowing) at the 1-year follow-up point was very low in both groups: 4.7% in the stent group and 9.5% in the balloon group. That difference was not statistically significant between groups.

Median in-segment late loss (the difference between minimal lumen diameter at completion of the procedure and at 1 year follow-up) was strikingly small and did not differ significantly between groups, reported Dr. Alfonso, an interventional cardiologist at Hospital Universitario Clinico San Carlos, Madrid.

Late loss in the stent group was 0.04 mm and in the balloon group was 0.14 mm, he added.

Rates of major adverse cardiac events were similar between groups: 94% in the stent group and 91% in the balloon group died of cardiac-related causes or had an MI or target vessel revascularization within a year of treatment. Rates of major adverse events also were statistically similar between groups in the RIBS V (Restenosis Intra-Stent of Bare Metal Stents: Paclitaxel-Eluting Balloon vs. Everolimus-Eluting Stent) trial.

A total of 6% of patients in the stent group and 12% in the balloon group developed a major adverse event; these rates were statistically similar. Four patients in the balloon group and none in the stent group died; three of the deaths were from noncardiac causes. Four patients in the stent group and three in the balloon group had an acute MI. Two patients in the stent group and six in the balloon group underwent target vessel revascularization. (Some patients had more than one adverse event.)

"In patients with bare metal stent in-stent restenosis, both drug-eluting balloons and everolimus-eluting stents provide excellent clinical outcomes" and excellent angiographic findings with very low late loss and low restenosis rates, Dr. Alfonso said at the meeting, cosponsored by the American College of Cardiology. "Further studies with larger numbers of patients and longer follow-up are required to elucidate if these superior late angiographic findings may eventually translate into a clinical benefit." In the meantime, drug-eluting balloons appear to offer "a very good alternative" for patients who may not be good candidates for drug-eluting stents, he said.

The study included patients aged 20-85 years at 25 Spanish centers who had more than 50% stenosis in a bare metal stent and angina or silent ischemia. In-segment quantitative coronary angiography measurements were similar between groups at baseline: the reference diameter was 2.63 mm in the stent group and 2.62 mm in the balloon group, and the lesion length was 13.8 mm in the stent group and 13.7 mm in the balloon group.

Patients who were randomized in 2010-2012 to receive Xience Prime everolimus-eluting stents (by Abbott Vascular) were significantly younger, compared with those who got SeQuent Please paclitaxel-eluting balloons (by B. Braun Surgical) – 64 vs. 67 years, respectively. Those in the stent group also were more likely to have ever smoked (75% vs. 59%, respectively). Eight patients in the balloon group eventually crossed over to stent implantation, and no patients in the stent group crossed over to balloons.

One-year follow-up was available for 170 patients (92%), and results were calculated in intent-to-treat analyses.

Dr. Alfonso reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

It seemed to me, as I was looking at the data, that drug-eluting balloons were pretty much going to be stuck in the peripheries. Yet these data, which are probably the best set of data that I’ve seen, tend to open the door. Maybe drug-eluting balloons have a role in the coronaries. There are lots of times that we don’t want to put in a drug-eluting stent, particularly in small vessels with long lesions. So I view this as a positive sign that there may be more choices for us that are meaningful.

Dr. Michael R. Mooney of the Minneapolis Heart Institute gave these comments during a panel discussion of the study at the meeting. He reported having no financial disclosures.

It seemed to me, as I was looking at the data, that drug-eluting balloons were pretty much going to be stuck in the peripheries. Yet these data, which are probably the best set of data that I’ve seen, tend to open the door. Maybe drug-eluting balloons have a role in the coronaries. There are lots of times that we don’t want to put in a drug-eluting stent, particularly in small vessels with long lesions. So I view this as a positive sign that there may be more choices for us that are meaningful.

Dr. Michael R. Mooney of the Minneapolis Heart Institute gave these comments during a panel discussion of the study at the meeting. He reported having no financial disclosures.

It seemed to me, as I was looking at the data, that drug-eluting balloons were pretty much going to be stuck in the peripheries. Yet these data, which are probably the best set of data that I’ve seen, tend to open the door. Maybe drug-eluting balloons have a role in the coronaries. There are lots of times that we don’t want to put in a drug-eluting stent, particularly in small vessels with long lesions. So I view this as a positive sign that there may be more choices for us that are meaningful.

Dr. Michael R. Mooney of the Minneapolis Heart Institute gave these comments during a panel discussion of the study at the meeting. He reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Treating bare metal stent in-stent restenosis using a drug-eluting stent yielded a significantly larger minimal lumen diameter 1 year later, compared with treatment using a drug-eluting balloon in a study of 189 patients.

A second-generation everolimus-eluting stent bested a paclitaxel-eluting balloon in the primary outcome of the prospective, randomized trial after adjusting for age, smoking history, stenosis, and the presence of diabetes.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The in-segment minimal lumen diameter was 2.36 mm for the 94 patients in the stent group and 2.01 mm for the 95 patients in the balloon group. The in-lesion minimal lumen diameter was 2.44 mm in the stent group and 2.03 mm in the balloon group. Both differences were statistically significant, Dr. Fernando Alfonso and his associates reported at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting.

The rate of restenosis (greater than 50% lumen diameter narrowing) at the 1-year follow-up point was very low in both groups: 4.7% in the stent group and 9.5% in the balloon group. That difference was not statistically significant between groups.

Median in-segment late loss (the difference between minimal lumen diameter at completion of the procedure and at 1 year follow-up) was strikingly small and did not differ significantly between groups, reported Dr. Alfonso, an interventional cardiologist at Hospital Universitario Clinico San Carlos, Madrid.

Late loss in the stent group was 0.04 mm and in the balloon group was 0.14 mm, he added.

Rates of major adverse cardiac events were similar between groups: 94% in the stent group and 91% in the balloon group died of cardiac-related causes or had an MI or target vessel revascularization within a year of treatment. Rates of major adverse events also were statistically similar between groups in the RIBS V (Restenosis Intra-Stent of Bare Metal Stents: Paclitaxel-Eluting Balloon vs. Everolimus-Eluting Stent) trial.

A total of 6% of patients in the stent group and 12% in the balloon group developed a major adverse event; these rates were statistically similar. Four patients in the balloon group and none in the stent group died; three of the deaths were from noncardiac causes. Four patients in the stent group and three in the balloon group had an acute MI. Two patients in the stent group and six in the balloon group underwent target vessel revascularization. (Some patients had more than one adverse event.)

"In patients with bare metal stent in-stent restenosis, both drug-eluting balloons and everolimus-eluting stents provide excellent clinical outcomes" and excellent angiographic findings with very low late loss and low restenosis rates, Dr. Alfonso said at the meeting, cosponsored by the American College of Cardiology. "Further studies with larger numbers of patients and longer follow-up are required to elucidate if these superior late angiographic findings may eventually translate into a clinical benefit." In the meantime, drug-eluting balloons appear to offer "a very good alternative" for patients who may not be good candidates for drug-eluting stents, he said.

The study included patients aged 20-85 years at 25 Spanish centers who had more than 50% stenosis in a bare metal stent and angina or silent ischemia. In-segment quantitative coronary angiography measurements were similar between groups at baseline: the reference diameter was 2.63 mm in the stent group and 2.62 mm in the balloon group, and the lesion length was 13.8 mm in the stent group and 13.7 mm in the balloon group.

Patients who were randomized in 2010-2012 to receive Xience Prime everolimus-eluting stents (by Abbott Vascular) were significantly younger, compared with those who got SeQuent Please paclitaxel-eluting balloons (by B. Braun Surgical) – 64 vs. 67 years, respectively. Those in the stent group also were more likely to have ever smoked (75% vs. 59%, respectively). Eight patients in the balloon group eventually crossed over to stent implantation, and no patients in the stent group crossed over to balloons.

One-year follow-up was available for 170 patients (92%), and results were calculated in intent-to-treat analyses.

Dr. Alfonso reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN FRANCISCO – Treating bare metal stent in-stent restenosis using a drug-eluting stent yielded a significantly larger minimal lumen diameter 1 year later, compared with treatment using a drug-eluting balloon in a study of 189 patients.

A second-generation everolimus-eluting stent bested a paclitaxel-eluting balloon in the primary outcome of the prospective, randomized trial after adjusting for age, smoking history, stenosis, and the presence of diabetes.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The in-segment minimal lumen diameter was 2.36 mm for the 94 patients in the stent group and 2.01 mm for the 95 patients in the balloon group. The in-lesion minimal lumen diameter was 2.44 mm in the stent group and 2.03 mm in the balloon group. Both differences were statistically significant, Dr. Fernando Alfonso and his associates reported at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting.

The rate of restenosis (greater than 50% lumen diameter narrowing) at the 1-year follow-up point was very low in both groups: 4.7% in the stent group and 9.5% in the balloon group. That difference was not statistically significant between groups.

Median in-segment late loss (the difference between minimal lumen diameter at completion of the procedure and at 1 year follow-up) was strikingly small and did not differ significantly between groups, reported Dr. Alfonso, an interventional cardiologist at Hospital Universitario Clinico San Carlos, Madrid.

Late loss in the stent group was 0.04 mm and in the balloon group was 0.14 mm, he added.

Rates of major adverse cardiac events were similar between groups: 94% in the stent group and 91% in the balloon group died of cardiac-related causes or had an MI or target vessel revascularization within a year of treatment. Rates of major adverse events also were statistically similar between groups in the RIBS V (Restenosis Intra-Stent of Bare Metal Stents: Paclitaxel-Eluting Balloon vs. Everolimus-Eluting Stent) trial.

A total of 6% of patients in the stent group and 12% in the balloon group developed a major adverse event; these rates were statistically similar. Four patients in the balloon group and none in the stent group died; three of the deaths were from noncardiac causes. Four patients in the stent group and three in the balloon group had an acute MI. Two patients in the stent group and six in the balloon group underwent target vessel revascularization. (Some patients had more than one adverse event.)

"In patients with bare metal stent in-stent restenosis, both drug-eluting balloons and everolimus-eluting stents provide excellent clinical outcomes" and excellent angiographic findings with very low late loss and low restenosis rates, Dr. Alfonso said at the meeting, cosponsored by the American College of Cardiology. "Further studies with larger numbers of patients and longer follow-up are required to elucidate if these superior late angiographic findings may eventually translate into a clinical benefit." In the meantime, drug-eluting balloons appear to offer "a very good alternative" for patients who may not be good candidates for drug-eluting stents, he said.

The study included patients aged 20-85 years at 25 Spanish centers who had more than 50% stenosis in a bare metal stent and angina or silent ischemia. In-segment quantitative coronary angiography measurements were similar between groups at baseline: the reference diameter was 2.63 mm in the stent group and 2.62 mm in the balloon group, and the lesion length was 13.8 mm in the stent group and 13.7 mm in the balloon group.

Patients who were randomized in 2010-2012 to receive Xience Prime everolimus-eluting stents (by Abbott Vascular) were significantly younger, compared with those who got SeQuent Please paclitaxel-eluting balloons (by B. Braun Surgical) – 64 vs. 67 years, respectively. Those in the stent group also were more likely to have ever smoked (75% vs. 59%, respectively). Eight patients in the balloon group eventually crossed over to stent implantation, and no patients in the stent group crossed over to balloons.

One-year follow-up was available for 170 patients (92%), and results were calculated in intent-to-treat analyses.

Dr. Alfonso reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

AT TCT 2013

Major finding: The in-segment minimal lumen diameter at 1 year was 2.36 mm with the second-generation everolimus-eluting stent and 2.01 mm with the paclitaxel-eluting balloon.

Data source: A prospective, multicenter, randomized trial in 189 patients treated for bare-metal stent in-stent restenosis.

Disclosures: Dr. Alfonso reported having no financial disclosures.

Emergency department electronic record systems fell short in Boston bombings

The massive number of injured patients from the April 2013 Boston Marathon bombings overwhelmed electronic medical records and information systems in some Boston emergency departments.

Their experiences offer an important lesson at a time when most hospitals have switched to electronic systems and providers are soon to face financial penalties for not doing so.

During mass-casualty events, paper and pen might be best, said Dr. Andrew Ulrich, executive vice chair of emergency medicine at the Boston Medical Center (BMC).

"The ability to get names into the system fast enough to order tests and establish a medical record limited us" on April 15, he noted. "There were so many patients coming through so quickly [23 at BMC right after the bombs went off] that it was difficult to know exactly who had what done and where they were going. You couldn’t leave the patient to" go to a computer, log on, get an update, and place orders, Dr. Ulrich said.

Other hospitals "had similar experiences. Communication was one of the more difficult components of this event," he said.

At Brigham and Women’s Hospital, "the first issue was our naming convention. We found that when every patient is ‘unidentified’ with a string of numbers, there’s a lot of confusion and many near misses. [Also,] if your system is inundated with multiple patients at once, it takes more time to register them so you can" go to work, said Dr. Eric Goralnick, the hospital’s medical director of emergency preparedness, who helped care for the 19 blast victims his ED received in the first half hour, and more later.

Now, at Brigham and Women’s, unknown patients are identified with a color, state, or other quickly recognized word.

Since the bombings, the EDs at Boston Medical Center and Brigham and Women’s have stocked up on old-school paper-and-pen trauma packets – an envelope with a wrist band, presigned orders, and other care documents all prestamped with a unique identifier – so that they are ready for the next mass-casualty event.

"We are much more flexible, much more adaptable if we go back to basics on this one, and that’s paper and pen. We are preparing to do that" for the next disaster, so "we can pull a bracelet out of the packet, throw it on the wrist," and start to work. It’s "much faster than getting [patients] onto the [electronic] medical record," Dr. Ulrich said.

Also from the old school department: "We [may also] have a clipboard attached to the patient’s bed, so when the patient rolls somewhere else, whoever gets them just has to look at the paperwork" to know what’s going on "instead of separating information from the patient" with the computer system, he said. "In a situation where there’s so much going on, it’s a clearer way of exchanging information."

Electronic record problems aren’t uncommon in EDs.

"There are many places where the computer system is a barrier to care. If you are trying to handle [an event] like this with a system that’s optimized for internal medicine clinics, it’s not going to work," said Dr. Larry Nathanson, who helped tend to the 22 bombing victims Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center received in the first hour, almost half of whom were in critical condition.

Things went more smoothly at Beth Israel, where the electronic information system worked well. Part of the reason is that the hospital uses a home-grown system designed by Dr. Nathanson, a computer programmer as well as an emergency physician. The system is quick and provides patient information with few clicks. To identify unknown patients, the system uses a convention similar to the one used to name hurricanes (Annie, Bruce, Candace, etc.); the record can be easily updated once a patient’s identity is known.

The system had been tested prior to the bombings via simulation including 500 patients. "We made sure beforehand that [it] could handle the influx and quickly register large volumes of critical patients," said Dr. Nathanson, who serves as the ED’s director of emergency medical informatics.

"The reason it worked well in a disaster is because it works well every day," he said.

Based on feedback from his colleagues, he’s since added an interface that pops up when two or more mass-casualty victims are in the ED. Pressing it displays them all with a summary of their situations, so providers can home in on them.

Dr. Ulrich and Dr. Goralnick have no relevant disclosures. Dr. Nathanson owns stock in Forerun Inc., the commercialized version of the system he developed for Beth Israel.

The massive number of injured patients from the April 2013 Boston Marathon bombings overwhelmed electronic medical records and information systems in some Boston emergency departments.

Their experiences offer an important lesson at a time when most hospitals have switched to electronic systems and providers are soon to face financial penalties for not doing so.

During mass-casualty events, paper and pen might be best, said Dr. Andrew Ulrich, executive vice chair of emergency medicine at the Boston Medical Center (BMC).

"The ability to get names into the system fast enough to order tests and establish a medical record limited us" on April 15, he noted. "There were so many patients coming through so quickly [23 at BMC right after the bombs went off] that it was difficult to know exactly who had what done and where they were going. You couldn’t leave the patient to" go to a computer, log on, get an update, and place orders, Dr. Ulrich said.

Other hospitals "had similar experiences. Communication was one of the more difficult components of this event," he said.

At Brigham and Women’s Hospital, "the first issue was our naming convention. We found that when every patient is ‘unidentified’ with a string of numbers, there’s a lot of confusion and many near misses. [Also,] if your system is inundated with multiple patients at once, it takes more time to register them so you can" go to work, said Dr. Eric Goralnick, the hospital’s medical director of emergency preparedness, who helped care for the 19 blast victims his ED received in the first half hour, and more later.

Now, at Brigham and Women’s, unknown patients are identified with a color, state, or other quickly recognized word.

Since the bombings, the EDs at Boston Medical Center and Brigham and Women’s have stocked up on old-school paper-and-pen trauma packets – an envelope with a wrist band, presigned orders, and other care documents all prestamped with a unique identifier – so that they are ready for the next mass-casualty event.

"We are much more flexible, much more adaptable if we go back to basics on this one, and that’s paper and pen. We are preparing to do that" for the next disaster, so "we can pull a bracelet out of the packet, throw it on the wrist," and start to work. It’s "much faster than getting [patients] onto the [electronic] medical record," Dr. Ulrich said.

Also from the old school department: "We [may also] have a clipboard attached to the patient’s bed, so when the patient rolls somewhere else, whoever gets them just has to look at the paperwork" to know what’s going on "instead of separating information from the patient" with the computer system, he said. "In a situation where there’s so much going on, it’s a clearer way of exchanging information."

Electronic record problems aren’t uncommon in EDs.

"There are many places where the computer system is a barrier to care. If you are trying to handle [an event] like this with a system that’s optimized for internal medicine clinics, it’s not going to work," said Dr. Larry Nathanson, who helped tend to the 22 bombing victims Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center received in the first hour, almost half of whom were in critical condition.

Things went more smoothly at Beth Israel, where the electronic information system worked well. Part of the reason is that the hospital uses a home-grown system designed by Dr. Nathanson, a computer programmer as well as an emergency physician. The system is quick and provides patient information with few clicks. To identify unknown patients, the system uses a convention similar to the one used to name hurricanes (Annie, Bruce, Candace, etc.); the record can be easily updated once a patient’s identity is known.

The system had been tested prior to the bombings via simulation including 500 patients. "We made sure beforehand that [it] could handle the influx and quickly register large volumes of critical patients," said Dr. Nathanson, who serves as the ED’s director of emergency medical informatics.

"The reason it worked well in a disaster is because it works well every day," he said.

Based on feedback from his colleagues, he’s since added an interface that pops up when two or more mass-casualty victims are in the ED. Pressing it displays them all with a summary of their situations, so providers can home in on them.

Dr. Ulrich and Dr. Goralnick have no relevant disclosures. Dr. Nathanson owns stock in Forerun Inc., the commercialized version of the system he developed for Beth Israel.

The massive number of injured patients from the April 2013 Boston Marathon bombings overwhelmed electronic medical records and information systems in some Boston emergency departments.

Their experiences offer an important lesson at a time when most hospitals have switched to electronic systems and providers are soon to face financial penalties for not doing so.

During mass-casualty events, paper and pen might be best, said Dr. Andrew Ulrich, executive vice chair of emergency medicine at the Boston Medical Center (BMC).

"The ability to get names into the system fast enough to order tests and establish a medical record limited us" on April 15, he noted. "There were so many patients coming through so quickly [23 at BMC right after the bombs went off] that it was difficult to know exactly who had what done and where they were going. You couldn’t leave the patient to" go to a computer, log on, get an update, and place orders, Dr. Ulrich said.

Other hospitals "had similar experiences. Communication was one of the more difficult components of this event," he said.

At Brigham and Women’s Hospital, "the first issue was our naming convention. We found that when every patient is ‘unidentified’ with a string of numbers, there’s a lot of confusion and many near misses. [Also,] if your system is inundated with multiple patients at once, it takes more time to register them so you can" go to work, said Dr. Eric Goralnick, the hospital’s medical director of emergency preparedness, who helped care for the 19 blast victims his ED received in the first half hour, and more later.

Now, at Brigham and Women’s, unknown patients are identified with a color, state, or other quickly recognized word.

Since the bombings, the EDs at Boston Medical Center and Brigham and Women’s have stocked up on old-school paper-and-pen trauma packets – an envelope with a wrist band, presigned orders, and other care documents all prestamped with a unique identifier – so that they are ready for the next mass-casualty event.

"We are much more flexible, much more adaptable if we go back to basics on this one, and that’s paper and pen. We are preparing to do that" for the next disaster, so "we can pull a bracelet out of the packet, throw it on the wrist," and start to work. It’s "much faster than getting [patients] onto the [electronic] medical record," Dr. Ulrich said.

Also from the old school department: "We [may also] have a clipboard attached to the patient’s bed, so when the patient rolls somewhere else, whoever gets them just has to look at the paperwork" to know what’s going on "instead of separating information from the patient" with the computer system, he said. "In a situation where there’s so much going on, it’s a clearer way of exchanging information."

Electronic record problems aren’t uncommon in EDs.

"There are many places where the computer system is a barrier to care. If you are trying to handle [an event] like this with a system that’s optimized for internal medicine clinics, it’s not going to work," said Dr. Larry Nathanson, who helped tend to the 22 bombing victims Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center received in the first hour, almost half of whom were in critical condition.

Things went more smoothly at Beth Israel, where the electronic information system worked well. Part of the reason is that the hospital uses a home-grown system designed by Dr. Nathanson, a computer programmer as well as an emergency physician. The system is quick and provides patient information with few clicks. To identify unknown patients, the system uses a convention similar to the one used to name hurricanes (Annie, Bruce, Candace, etc.); the record can be easily updated once a patient’s identity is known.

The system had been tested prior to the bombings via simulation including 500 patients. "We made sure beforehand that [it] could handle the influx and quickly register large volumes of critical patients," said Dr. Nathanson, who serves as the ED’s director of emergency medical informatics.

"The reason it worked well in a disaster is because it works well every day," he said.

Based on feedback from his colleagues, he’s since added an interface that pops up when two or more mass-casualty victims are in the ED. Pressing it displays them all with a summary of their situations, so providers can home in on them.

Dr. Ulrich and Dr. Goralnick have no relevant disclosures. Dr. Nathanson owns stock in Forerun Inc., the commercialized version of the system he developed for Beth Israel.

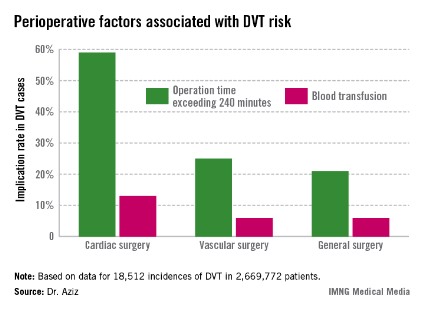

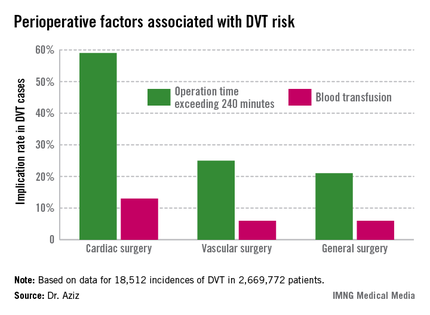

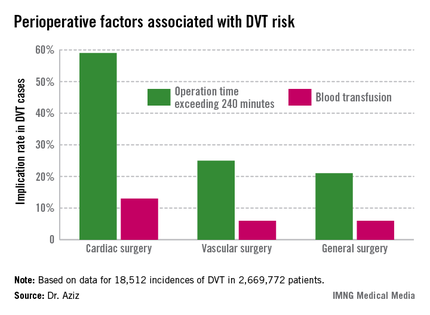

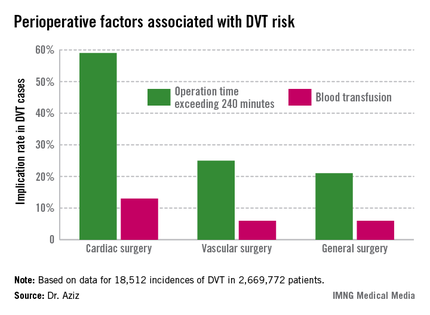

DVT risk higher in cardiac and vascular surgery patients

WASHINGTON – Cardiac and vascular surgery patients are at higher risk for deep vein thrombosis than are general surgery patients, according to data presented at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

In a retrospective analysis of 2,669,772 patients with a median age of 64 years, 43% of whom were males, in the ACS-National Surgery Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) during 2005-2009, Dr. Faisal Aziz of Penn State Hershey (Pa.) Heart and Vascular Institute and his colleagues sought to determine the actual rate of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) during revascularization procedures, compared with general surgery. They also investigated the relationship between the type of operation and the DVT incidence rate.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality considers the incidence rate of DVT a patient safety indicator. Dr. Aziz cited data indicating that one in four patients who develop DVT postoperatively before discharge has an additional venous thromboembolic event–related event in the subsequent 21 months requiring hospitalization, at a cost of approximately $15,000, or roughly 21% higher than the original DVT event (J. Manag. Care. Pharm. 2007;13:475-86).

The researchers sorted patients according to DVT risk factors such as age, gender, body mass index over 40 kg/m2, and whether the surgery was acute. They then assessed intraoperative factors such as total time to completion and its American Society of Anesthesiology score. They then considered the postoperative factors associated with DVT, such as blood transfusions, return to the operating room, deep wound infection, cardiac arrest, and mortality.

Dr. Aziz and his team determined that there were 18,512 incidences of DVT, equaling 0.69% of all patients studied. Of those, 0.66% occurred during general surgery, 2.08% occurred during cardiac surgery, and 1% occurred during vascular surgery.

"The implications of our study are that, contrary to popular belief, the incidence of postoperative DVT is actually higher after cardiac surgery and vascular surgery procedures," he said.

The cardiac surgery procedures associated with the highest DVT incidence rate were tricuspid valve replacement (8%), thoracic endovascular aortic repair (5%), thoracic aortic graft replacement (4%), and pericardial window (4%).

In a comparison of cardiac procedures, tricuspid valve replacement vs. aortic valve replacement had a risk ratio of 3.5 (P < .001). In tricuspid valve replacement vs. coronary artery bypass, the former had a risk ratio of 11.24 (P < .001).

Vascular surgeries with the highest DVT incidence rates were peripheral bypass (1%), amputation (trans-metatarsal, 0.75%; below knee, 1%; above the knee, 1%), and ruptured aortic aneurysms (3.5%), Dr. Aziz reported.

Intra-and postoperative factors associated with DVT risk included operation times exceeding 240 minutes and previous DVT. Compared with 21% of general surgery patients, operation time was implicated in 59% of cardiac surgery patients (relative risk, 2.72; P < .001) and 25% of vascular surgery patients (RR, 1.14; P <.001). Blood transfusions affected 13% of cardiac surgery patients (RR, 2.3; P < .001), 6% of vascular surgery patients (RR, 1.3; P < .001), and 6% of general surgery patients.

Compared with 24% for general surgery patients, returning to the operating room was implicated in 27% of cardiac patients (RR, 1.4; P = .27) and 32% of vascular surgery patients (RR, 1.3; P < .001).

"Procedures and perioperative factors associated with high risk of postoperative DVT should be identified, and adequate DVT prophylaxis should be ensured for these patients," he concluded.

Dr. Aziz and his associates had no disclosures.

WASHINGTON – Cardiac and vascular surgery patients are at higher risk for deep vein thrombosis than are general surgery patients, according to data presented at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

In a retrospective analysis of 2,669,772 patients with a median age of 64 years, 43% of whom were males, in the ACS-National Surgery Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) during 2005-2009, Dr. Faisal Aziz of Penn State Hershey (Pa.) Heart and Vascular Institute and his colleagues sought to determine the actual rate of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) during revascularization procedures, compared with general surgery. They also investigated the relationship between the type of operation and the DVT incidence rate.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality considers the incidence rate of DVT a patient safety indicator. Dr. Aziz cited data indicating that one in four patients who develop DVT postoperatively before discharge has an additional venous thromboembolic event–related event in the subsequent 21 months requiring hospitalization, at a cost of approximately $15,000, or roughly 21% higher than the original DVT event (J. Manag. Care. Pharm. 2007;13:475-86).

The researchers sorted patients according to DVT risk factors such as age, gender, body mass index over 40 kg/m2, and whether the surgery was acute. They then assessed intraoperative factors such as total time to completion and its American Society of Anesthesiology score. They then considered the postoperative factors associated with DVT, such as blood transfusions, return to the operating room, deep wound infection, cardiac arrest, and mortality.

Dr. Aziz and his team determined that there were 18,512 incidences of DVT, equaling 0.69% of all patients studied. Of those, 0.66% occurred during general surgery, 2.08% occurred during cardiac surgery, and 1% occurred during vascular surgery.

"The implications of our study are that, contrary to popular belief, the incidence of postoperative DVT is actually higher after cardiac surgery and vascular surgery procedures," he said.

The cardiac surgery procedures associated with the highest DVT incidence rate were tricuspid valve replacement (8%), thoracic endovascular aortic repair (5%), thoracic aortic graft replacement (4%), and pericardial window (4%).

In a comparison of cardiac procedures, tricuspid valve replacement vs. aortic valve replacement had a risk ratio of 3.5 (P < .001). In tricuspid valve replacement vs. coronary artery bypass, the former had a risk ratio of 11.24 (P < .001).

Vascular surgeries with the highest DVT incidence rates were peripheral bypass (1%), amputation (trans-metatarsal, 0.75%; below knee, 1%; above the knee, 1%), and ruptured aortic aneurysms (3.5%), Dr. Aziz reported.

Intra-and postoperative factors associated with DVT risk included operation times exceeding 240 minutes and previous DVT. Compared with 21% of general surgery patients, operation time was implicated in 59% of cardiac surgery patients (relative risk, 2.72; P < .001) and 25% of vascular surgery patients (RR, 1.14; P <.001). Blood transfusions affected 13% of cardiac surgery patients (RR, 2.3; P < .001), 6% of vascular surgery patients (RR, 1.3; P < .001), and 6% of general surgery patients.

Compared with 24% for general surgery patients, returning to the operating room was implicated in 27% of cardiac patients (RR, 1.4; P = .27) and 32% of vascular surgery patients (RR, 1.3; P < .001).

"Procedures and perioperative factors associated with high risk of postoperative DVT should be identified, and adequate DVT prophylaxis should be ensured for these patients," he concluded.

Dr. Aziz and his associates had no disclosures.

WASHINGTON – Cardiac and vascular surgery patients are at higher risk for deep vein thrombosis than are general surgery patients, according to data presented at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

In a retrospective analysis of 2,669,772 patients with a median age of 64 years, 43% of whom were males, in the ACS-National Surgery Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) during 2005-2009, Dr. Faisal Aziz of Penn State Hershey (Pa.) Heart and Vascular Institute and his colleagues sought to determine the actual rate of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) during revascularization procedures, compared with general surgery. They also investigated the relationship between the type of operation and the DVT incidence rate.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality considers the incidence rate of DVT a patient safety indicator. Dr. Aziz cited data indicating that one in four patients who develop DVT postoperatively before discharge has an additional venous thromboembolic event–related event in the subsequent 21 months requiring hospitalization, at a cost of approximately $15,000, or roughly 21% higher than the original DVT event (J. Manag. Care. Pharm. 2007;13:475-86).

The researchers sorted patients according to DVT risk factors such as age, gender, body mass index over 40 kg/m2, and whether the surgery was acute. They then assessed intraoperative factors such as total time to completion and its American Society of Anesthesiology score. They then considered the postoperative factors associated with DVT, such as blood transfusions, return to the operating room, deep wound infection, cardiac arrest, and mortality.

Dr. Aziz and his team determined that there were 18,512 incidences of DVT, equaling 0.69% of all patients studied. Of those, 0.66% occurred during general surgery, 2.08% occurred during cardiac surgery, and 1% occurred during vascular surgery.

"The implications of our study are that, contrary to popular belief, the incidence of postoperative DVT is actually higher after cardiac surgery and vascular surgery procedures," he said.

The cardiac surgery procedures associated with the highest DVT incidence rate were tricuspid valve replacement (8%), thoracic endovascular aortic repair (5%), thoracic aortic graft replacement (4%), and pericardial window (4%).

In a comparison of cardiac procedures, tricuspid valve replacement vs. aortic valve replacement had a risk ratio of 3.5 (P < .001). In tricuspid valve replacement vs. coronary artery bypass, the former had a risk ratio of 11.24 (P < .001).

Vascular surgeries with the highest DVT incidence rates were peripheral bypass (1%), amputation (trans-metatarsal, 0.75%; below knee, 1%; above the knee, 1%), and ruptured aortic aneurysms (3.5%), Dr. Aziz reported.

Intra-and postoperative factors associated with DVT risk included operation times exceeding 240 minutes and previous DVT. Compared with 21% of general surgery patients, operation time was implicated in 59% of cardiac surgery patients (relative risk, 2.72; P < .001) and 25% of vascular surgery patients (RR, 1.14; P <.001). Blood transfusions affected 13% of cardiac surgery patients (RR, 2.3; P < .001), 6% of vascular surgery patients (RR, 1.3; P < .001), and 6% of general surgery patients.

Compared with 24% for general surgery patients, returning to the operating room was implicated in 27% of cardiac patients (RR, 1.4; P = .27) and 32% of vascular surgery patients (RR, 1.3; P < .001).

"Procedures and perioperative factors associated with high risk of postoperative DVT should be identified, and adequate DVT prophylaxis should be ensured for these patients," he concluded.

Dr. Aziz and his associates had no disclosures.

AT THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

Major finding: Of the 2,669,772 patients studied, 18,512 (0.69%) had DVTs during surgery. The rate was 0.66% for general surgery, 2.08% for cardiac surgery, and 1% for vascular surgery.

Data source: Retrospective analysis of NSQIP 2005-2009 database analyzed according to surgical specialty.

Disclosures: Dr. Aziz and his associates had no disclosures.

The personal dimension of informed consent

Recently, a medical student assigned to my service spent a day in the outpatient office seeing patients with me. After seeing two consecutive patients who needed thyroidectomies, this student commented on the differences in how I obtained informed consent for thyroidectomy from the two patients. Why, she asked, had I spent relatively little time emphasizing the risks of the operation with one patient and so much more time discussing risks with the second patient?

In order to understand why there appeared to be such a dramatic difference between the discussions with the two patients, it is helpful to understand the different indications for surgery. The first patient had recently been diagnosed with a 2.3-cm papillary thyroid cancer. I had explained that the first step in the treatment was to remove the thyroid, and I detailed the risks to the recurrent laryngeal nerves and the parathyroid glands.

The second patient had been treated for Graves’ disease for the last 3 years. She had many cycles of hyper- and hypothyroidism and had now decided that she needed definitive treatment. Although she had discussed the option of radioactive iodine with her endocrinologist, she had a significant fear of radiation and also was hoping to become pregnant in the next several months. I had discussed the risks of thyroidectomy with this patient. However, even though the risk I quoted of having a complication from the thyroidectomy was just the same as in the first case, I deliberately spent more time discussing the ramifications of the complications and the alternatives with the second patient.

My student was initially perplexed by this description. As she correctly stated, if the risks are the same for the same operation between the two patients, why emphasize the risks so much more for the second patient, compared with the first?

To most surgeons, the reason for this difference is clear. The first patient needed to know the risks, but there were few options to total thyroidectomy as the initial step in the treatment. The second patient had the clear option of getting radioactive iodine instead of surgery. Although the risks of the surgical procedure are the same with the two operations, I felt that the second patient needed to clearly understand the alternative to surgery and to fully consider the implications of the potential complications should one occur in her case.

As I think back over this interchange with my student, it is clear that the informed consent discussion for any operation cannot be fully standardized for every patient. Even if the risks remain the same, the indications for surgery are different and, of course, the patients are different.

More than 30 years ago, Dr. C. Rollins Hanlon, then executive director of the American College of Surgeons wrote, "Both ethics and surgery are inexact disciplines, in definition, practice, and in relation to one another." The more years I have been in practice, the more I am convinced of the truth of these words. Although my two patients both needed the same operation, it was important for me to emphasize the choices that the second patient had. In so doing, I felt it was essential to ensure that in evaluating the choices, the patient fully understood the implications of the risks. Although the patient with thyroid cancer had the same risks of the procedure, she did not have a good alternative choice to surgery. The difference between these two patients, and in how I altered my discussions of the proposed thyroidectomy, reveal the personal dimension of informed consent that goes beyond a simple statement of risks.

In obtaining informed consent from my patients, I should be providing them with much more than "just the facts." Patients can (and often do) obtain the data about the risks of surgical procedures from the Internet prior to seeing me. I believe that I should be giving them something more than they could obtain from reading about the risks of a procedure. I should provide them with a context in which to consider the risks, relative to their particular condition. Even small risks may be very significant if there are alternatives that have no risks. In contrast, patients often quickly agree to high-risk operations when there is no good nonoperative alternative. As surgeons, we must be cognizant of the critical personal dimension of the informed consent process and thereby be sure to put the discussion of risks in the appropriate context to help our patients make good decisions.

Dr. Angelos is an ACS Fellow; the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics; chief, endocrine surgery; and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

Recently, a medical student assigned to my service spent a day in the outpatient office seeing patients with me. After seeing two consecutive patients who needed thyroidectomies, this student commented on the differences in how I obtained informed consent for thyroidectomy from the two patients. Why, she asked, had I spent relatively little time emphasizing the risks of the operation with one patient and so much more time discussing risks with the second patient?

In order to understand why there appeared to be such a dramatic difference between the discussions with the two patients, it is helpful to understand the different indications for surgery. The first patient had recently been diagnosed with a 2.3-cm papillary thyroid cancer. I had explained that the first step in the treatment was to remove the thyroid, and I detailed the risks to the recurrent laryngeal nerves and the parathyroid glands.

The second patient had been treated for Graves’ disease for the last 3 years. She had many cycles of hyper- and hypothyroidism and had now decided that she needed definitive treatment. Although she had discussed the option of radioactive iodine with her endocrinologist, she had a significant fear of radiation and also was hoping to become pregnant in the next several months. I had discussed the risks of thyroidectomy with this patient. However, even though the risk I quoted of having a complication from the thyroidectomy was just the same as in the first case, I deliberately spent more time discussing the ramifications of the complications and the alternatives with the second patient.

My student was initially perplexed by this description. As she correctly stated, if the risks are the same for the same operation between the two patients, why emphasize the risks so much more for the second patient, compared with the first?

To most surgeons, the reason for this difference is clear. The first patient needed to know the risks, but there were few options to total thyroidectomy as the initial step in the treatment. The second patient had the clear option of getting radioactive iodine instead of surgery. Although the risks of the surgical procedure are the same with the two operations, I felt that the second patient needed to clearly understand the alternative to surgery and to fully consider the implications of the potential complications should one occur in her case.

As I think back over this interchange with my student, it is clear that the informed consent discussion for any operation cannot be fully standardized for every patient. Even if the risks remain the same, the indications for surgery are different and, of course, the patients are different.

More than 30 years ago, Dr. C. Rollins Hanlon, then executive director of the American College of Surgeons wrote, "Both ethics and surgery are inexact disciplines, in definition, practice, and in relation to one another." The more years I have been in practice, the more I am convinced of the truth of these words. Although my two patients both needed the same operation, it was important for me to emphasize the choices that the second patient had. In so doing, I felt it was essential to ensure that in evaluating the choices, the patient fully understood the implications of the risks. Although the patient with thyroid cancer had the same risks of the procedure, she did not have a good alternative choice to surgery. The difference between these two patients, and in how I altered my discussions of the proposed thyroidectomy, reveal the personal dimension of informed consent that goes beyond a simple statement of risks.

In obtaining informed consent from my patients, I should be providing them with much more than "just the facts." Patients can (and often do) obtain the data about the risks of surgical procedures from the Internet prior to seeing me. I believe that I should be giving them something more than they could obtain from reading about the risks of a procedure. I should provide them with a context in which to consider the risks, relative to their particular condition. Even small risks may be very significant if there are alternatives that have no risks. In contrast, patients often quickly agree to high-risk operations when there is no good nonoperative alternative. As surgeons, we must be cognizant of the critical personal dimension of the informed consent process and thereby be sure to put the discussion of risks in the appropriate context to help our patients make good decisions.

Dr. Angelos is an ACS Fellow; the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics; chief, endocrine surgery; and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

Recently, a medical student assigned to my service spent a day in the outpatient office seeing patients with me. After seeing two consecutive patients who needed thyroidectomies, this student commented on the differences in how I obtained informed consent for thyroidectomy from the two patients. Why, she asked, had I spent relatively little time emphasizing the risks of the operation with one patient and so much more time discussing risks with the second patient?

In order to understand why there appeared to be such a dramatic difference between the discussions with the two patients, it is helpful to understand the different indications for surgery. The first patient had recently been diagnosed with a 2.3-cm papillary thyroid cancer. I had explained that the first step in the treatment was to remove the thyroid, and I detailed the risks to the recurrent laryngeal nerves and the parathyroid glands.

The second patient had been treated for Graves’ disease for the last 3 years. She had many cycles of hyper- and hypothyroidism and had now decided that she needed definitive treatment. Although she had discussed the option of radioactive iodine with her endocrinologist, she had a significant fear of radiation and also was hoping to become pregnant in the next several months. I had discussed the risks of thyroidectomy with this patient. However, even though the risk I quoted of having a complication from the thyroidectomy was just the same as in the first case, I deliberately spent more time discussing the ramifications of the complications and the alternatives with the second patient.

My student was initially perplexed by this description. As she correctly stated, if the risks are the same for the same operation between the two patients, why emphasize the risks so much more for the second patient, compared with the first?

To most surgeons, the reason for this difference is clear. The first patient needed to know the risks, but there were few options to total thyroidectomy as the initial step in the treatment. The second patient had the clear option of getting radioactive iodine instead of surgery. Although the risks of the surgical procedure are the same with the two operations, I felt that the second patient needed to clearly understand the alternative to surgery and to fully consider the implications of the potential complications should one occur in her case.

As I think back over this interchange with my student, it is clear that the informed consent discussion for any operation cannot be fully standardized for every patient. Even if the risks remain the same, the indications for surgery are different and, of course, the patients are different.

More than 30 years ago, Dr. C. Rollins Hanlon, then executive director of the American College of Surgeons wrote, "Both ethics and surgery are inexact disciplines, in definition, practice, and in relation to one another." The more years I have been in practice, the more I am convinced of the truth of these words. Although my two patients both needed the same operation, it was important for me to emphasize the choices that the second patient had. In so doing, I felt it was essential to ensure that in evaluating the choices, the patient fully understood the implications of the risks. Although the patient with thyroid cancer had the same risks of the procedure, she did not have a good alternative choice to surgery. The difference between these two patients, and in how I altered my discussions of the proposed thyroidectomy, reveal the personal dimension of informed consent that goes beyond a simple statement of risks.

In obtaining informed consent from my patients, I should be providing them with much more than "just the facts." Patients can (and often do) obtain the data about the risks of surgical procedures from the Internet prior to seeing me. I believe that I should be giving them something more than they could obtain from reading about the risks of a procedure. I should provide them with a context in which to consider the risks, relative to their particular condition. Even small risks may be very significant if there are alternatives that have no risks. In contrast, patients often quickly agree to high-risk operations when there is no good nonoperative alternative. As surgeons, we must be cognizant of the critical personal dimension of the informed consent process and thereby be sure to put the discussion of risks in the appropriate context to help our patients make good decisions.

Dr. Angelos is an ACS Fellow; the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics; chief, endocrine surgery; and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

New podcast reviews ACS NSQIP® Surgical Risk Calculator

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) has launched a new podcast episode of its Recovery Room Show featuring a discussion of the new ACS National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP®) Surgical Risk Calculator. In the podcast, host Frederick L. Greene, MD, FACS, a surgical oncologist from Charlotte, NC, and a member of the Commission on Cancer, interviews two surgeons, Clifford Y. Ko, MD, FACS, and Karl Bilimoria, MD, FACS, who developed the risk calculator. The guest surgeons share their thoughts on the ability of the surgical risk calculator to create an important dialogue between surgeons and patients about surgical risks and the how the tool may be used to deliver individualized patient care.

Dr. Ko is a colorectal surgeon at the University of California-Los Angeles and Director of the ACS Division of Research and Optimal Patient Care and ACS NSQIP. Dr. Bilimoria is a surgical oncologist in the department of surgery and director of the Surgical Outcomes and Quality Improvement Center at the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University, Chicago, IL.

Current and past episodes of the Recovery Room may be downloaded at no charge through the College’s website at http://www.facs.org/recoveryroom.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) has launched a new podcast episode of its Recovery Room Show featuring a discussion of the new ACS National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP®) Surgical Risk Calculator. In the podcast, host Frederick L. Greene, MD, FACS, a surgical oncologist from Charlotte, NC, and a member of the Commission on Cancer, interviews two surgeons, Clifford Y. Ko, MD, FACS, and Karl Bilimoria, MD, FACS, who developed the risk calculator. The guest surgeons share their thoughts on the ability of the surgical risk calculator to create an important dialogue between surgeons and patients about surgical risks and the how the tool may be used to deliver individualized patient care.

Dr. Ko is a colorectal surgeon at the University of California-Los Angeles and Director of the ACS Division of Research and Optimal Patient Care and ACS NSQIP. Dr. Bilimoria is a surgical oncologist in the department of surgery and director of the Surgical Outcomes and Quality Improvement Center at the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University, Chicago, IL.

Current and past episodes of the Recovery Room may be downloaded at no charge through the College’s website at http://www.facs.org/recoveryroom.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) has launched a new podcast episode of its Recovery Room Show featuring a discussion of the new ACS National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP®) Surgical Risk Calculator. In the podcast, host Frederick L. Greene, MD, FACS, a surgical oncologist from Charlotte, NC, and a member of the Commission on Cancer, interviews two surgeons, Clifford Y. Ko, MD, FACS, and Karl Bilimoria, MD, FACS, who developed the risk calculator. The guest surgeons share their thoughts on the ability of the surgical risk calculator to create an important dialogue between surgeons and patients about surgical risks and the how the tool may be used to deliver individualized patient care.

Dr. Ko is a colorectal surgeon at the University of California-Los Angeles and Director of the ACS Division of Research and Optimal Patient Care and ACS NSQIP. Dr. Bilimoria is a surgical oncologist in the department of surgery and director of the Surgical Outcomes and Quality Improvement Center at the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University, Chicago, IL.

Current and past episodes of the Recovery Room may be downloaded at no charge through the College’s website at http://www.facs.org/recoveryroom.

ACS leadership in Hartford Consensus receives national media attention

The American College of Surgeons’ (ACS) leadership in the Hartford Consensus recently received significant media coverage with articles running in The Wall Street Journal (Tourniquets Gain New Respect, Oct. 23), The Hartford Courant (FEMA Adopts Active-Shooter Guidelines Calling for "Warm Zones," Tourniquets, Oct. 21), as well as Medscape, Family Practice News, and ELsGlobalMedicalNews.

The Wall Street Journal article cited recommendations by members of the Hartford Consensus at the "Mass-Casualty Shootings: Saving the Patients," session at this year’s Clinical Congress. The group, led by the ACS, advocates for tourniquet use to control hemorrhage as a core component of the emergency response to mass-casualty events. The article quotes Hartford Consensus members ACS Regent Lenworth M. Jacobs, MD, MPH, FACS, vice-president of academic affairs and chief academic officer and director, Trauma Institute, at Hartford Hospital, CT; and Alexander Eastman, MD, MPH, FACS, chief of trauma at the University of Texas Southwestern/Parkland Memorial Hospital, and Lieutenant/Deputy Medical Director, Dallas Police Department. The Wall Street Journal article is at http://on.wsj.com/161KJTi (subscribers only). View the ACS news release on topics covered at the Clinical Congress session at http://www.facs.org/news/2013/hartford1013.html.

The American College of Surgeons’ (ACS) leadership in the Hartford Consensus recently received significant media coverage with articles running in The Wall Street Journal (Tourniquets Gain New Respect, Oct. 23), The Hartford Courant (FEMA Adopts Active-Shooter Guidelines Calling for "Warm Zones," Tourniquets, Oct. 21), as well as Medscape, Family Practice News, and ELsGlobalMedicalNews.

The Wall Street Journal article cited recommendations by members of the Hartford Consensus at the "Mass-Casualty Shootings: Saving the Patients," session at this year’s Clinical Congress. The group, led by the ACS, advocates for tourniquet use to control hemorrhage as a core component of the emergency response to mass-casualty events. The article quotes Hartford Consensus members ACS Regent Lenworth M. Jacobs, MD, MPH, FACS, vice-president of academic affairs and chief academic officer and director, Trauma Institute, at Hartford Hospital, CT; and Alexander Eastman, MD, MPH, FACS, chief of trauma at the University of Texas Southwestern/Parkland Memorial Hospital, and Lieutenant/Deputy Medical Director, Dallas Police Department. The Wall Street Journal article is at http://on.wsj.com/161KJTi (subscribers only). View the ACS news release on topics covered at the Clinical Congress session at http://www.facs.org/news/2013/hartford1013.html.

The American College of Surgeons’ (ACS) leadership in the Hartford Consensus recently received significant media coverage with articles running in The Wall Street Journal (Tourniquets Gain New Respect, Oct. 23), The Hartford Courant (FEMA Adopts Active-Shooter Guidelines Calling for "Warm Zones," Tourniquets, Oct. 21), as well as Medscape, Family Practice News, and ELsGlobalMedicalNews.

The Wall Street Journal article cited recommendations by members of the Hartford Consensus at the "Mass-Casualty Shootings: Saving the Patients," session at this year’s Clinical Congress. The group, led by the ACS, advocates for tourniquet use to control hemorrhage as a core component of the emergency response to mass-casualty events. The article quotes Hartford Consensus members ACS Regent Lenworth M. Jacobs, MD, MPH, FACS, vice-president of academic affairs and chief academic officer and director, Trauma Institute, at Hartford Hospital, CT; and Alexander Eastman, MD, MPH, FACS, chief of trauma at the University of Texas Southwestern/Parkland Memorial Hospital, and Lieutenant/Deputy Medical Director, Dallas Police Department. The Wall Street Journal article is at http://on.wsj.com/161KJTi (subscribers only). View the ACS news release on topics covered at the Clinical Congress session at http://www.facs.org/news/2013/hartford1013.html.

The RUC – A surgeon’s perspective

Recent changes in the Relative Value Update Committee process are going to have an impact on the committee’s work and output. Surgeons need to know what these changes may mean for our profession.

The RUC is a committee convened by the American Medical Association and composed of representatives of all the major medical specialties who meet to analyze in medical procedures and other work of physicians. Most specialties have four committee members: a delegate and alternate delegate who help deliberate the relative value of CPT codes, and an advisor and alternate advisor who present codes pertinent to the specialty they represent. The RUC does not determine monetary value of the work it reviews. The job of assigning payment rates is left to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid. CMS takes into consideration the recommendation of relative work by the RUC and applies a complex algorithm to arrive at a payment schedule.

A forceful argument against the current RUC process is that of "the fox guarding the henhouse." In other words, the physicians are seen as setting their own payment. This is a misunderstanding or perhaps a misrepresentation of the way the RUC works. The RUC recommends, but CMS may or may not accept the recommendations. In the past CMS has accepted the RUC recommendations 90%-95% of the time. Last year CMS accepted only 75% of the recommendations. This trend is of interest to surgeons because most of the recommendations concerned surgical procedures. Many were "bread and butter" general surgical procedures such as thyroid, and as one might guess, CMS lowered the values.

The work done by the RUC is extremely deliberative and requires careful consideration and fairness by dedicated committee members. In addition, physicians’ work is very technical and requires specialized knowledge that only physicians can bring to the process. I cannot imagine an economist trying to determine the work, the intensity, the number of hospital visits, or the number of office visits for any procedure. Who can analyze the amount and type of work involved in medical practice better than those who actually do the work?

The RUC has proposed and implemented new rules in regard to transparency. Transparency in this context, however, is a double-edged sword. While transparency allows citizens and leaders to get a feel for the process, full disclosure of the discussions and debates involved runs the risk of interfering with that process. There can be tremendous medical, legal, financial and political consequences of the recommendations of the RUC, and it would not be unreasonable to expect significant attempts by a variety of actors to influence the process.

Making the RUC votes public may improve understanding of the RUC, but it could also work to the detriment of the committee’s process.

A two-thirds majority is needed for passage of a work value, and many specialties must agree each time a code passes. If individual votes are made public, the committee members are not protected from pressure from outside actors. Often specialties will vote to increase a code of another specialty. In a budget-neutral system, if your codes go up, mine go down.

Making the vote transparent may prevent a delegate from truly being deliberative to appear more supportive of his or her own specialty. Indeed, the specialty groups could monitor the votes to ensure the codes are "protected," and this has the potential to change the delegate from a "deliberator" to a protector of his or her specialty. That is not the role of the delegate. While I support the publication of the votes in aggregate, I do not support the individual votes for this reason.

There is no doubt that changes are needed. The idea that a survey of 50 specialists will accurately reflect the work may be at times incorrect. If a procedure is performed a few thousand times a year, 50 surveys may be sufficient, but other codes performed millions of times a year such as cardiac catheterization, colonoscopy, or hernia repair I believe need more evaluation than 50 surveys.

The proposed change to make the survey uniform is problematic. There is great variation in procedures, and I find it difficult to think a psychiatric session could be evaluated with the same form as a pediatric cardiac procedure. Regularly, an "expert panel," usually the coding and reimbursement committee of the medical specialties, reviews work and can often help tease out the type of survey and the numbers needed for a particular code. With the process now being undertaken by the AMA with a centralized online tool, the specialties will lose that ability.

Clearly the RUC is far from perfect. Many of the objections, however, are based on perceptions, not the realities, of the process. The chair of the RUC has stated that she has never turned down a request to attend an RUC meeting. Transparency may appear as a solution to perceptions of secrecy and self-interest of specialties, but comes with its own set of problems. Using a group of surveys to value work is less than perfect and making the survey uniform will, in my opinion, make accurate valuation more difficult. That said, I do not believe any other body in existence or proposed could assume the work of the RUC. The specialties and the AMA pay for the whole process and then present the many hours of work to CMS without charge. I seriously doubt a group of economists, public health experts, or even other health care providers could accurately determine the amount of work required for a specific procedure. Only physicians have the skill set, experience, and knowledge to do this.

Dr. Rubin is an ACS Fellow, chair of the ACS General Surgery Coding and Reimbursement Committee and alternate delegate of the AMA Relative Value Update Committee.

Recent changes in the Relative Value Update Committee process are going to have an impact on the committee’s work and output. Surgeons need to know what these changes may mean for our profession.

The RUC is a committee convened by the American Medical Association and composed of representatives of all the major medical specialties who meet to analyze in medical procedures and other work of physicians. Most specialties have four committee members: a delegate and alternate delegate who help deliberate the relative value of CPT codes, and an advisor and alternate advisor who present codes pertinent to the specialty they represent. The RUC does not determine monetary value of the work it reviews. The job of assigning payment rates is left to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid. CMS takes into consideration the recommendation of relative work by the RUC and applies a complex algorithm to arrive at a payment schedule.

A forceful argument against the current RUC process is that of "the fox guarding the henhouse." In other words, the physicians are seen as setting their own payment. This is a misunderstanding or perhaps a misrepresentation of the way the RUC works. The RUC recommends, but CMS may or may not accept the recommendations. In the past CMS has accepted the RUC recommendations 90%-95% of the time. Last year CMS accepted only 75% of the recommendations. This trend is of interest to surgeons because most of the recommendations concerned surgical procedures. Many were "bread and butter" general surgical procedures such as thyroid, and as one might guess, CMS lowered the values.

The work done by the RUC is extremely deliberative and requires careful consideration and fairness by dedicated committee members. In addition, physicians’ work is very technical and requires specialized knowledge that only physicians can bring to the process. I cannot imagine an economist trying to determine the work, the intensity, the number of hospital visits, or the number of office visits for any procedure. Who can analyze the amount and type of work involved in medical practice better than those who actually do the work?

The RUC has proposed and implemented new rules in regard to transparency. Transparency in this context, however, is a double-edged sword. While transparency allows citizens and leaders to get a feel for the process, full disclosure of the discussions and debates involved runs the risk of interfering with that process. There can be tremendous medical, legal, financial and political consequences of the recommendations of the RUC, and it would not be unreasonable to expect significant attempts by a variety of actors to influence the process.

Making the RUC votes public may improve understanding of the RUC, but it could also work to the detriment of the committee’s process.

A two-thirds majority is needed for passage of a work value, and many specialties must agree each time a code passes. If individual votes are made public, the committee members are not protected from pressure from outside actors. Often specialties will vote to increase a code of another specialty. In a budget-neutral system, if your codes go up, mine go down.

Making the vote transparent may prevent a delegate from truly being deliberative to appear more supportive of his or her own specialty. Indeed, the specialty groups could monitor the votes to ensure the codes are "protected," and this has the potential to change the delegate from a "deliberator" to a protector of his or her specialty. That is not the role of the delegate. While I support the publication of the votes in aggregate, I do not support the individual votes for this reason.

There is no doubt that changes are needed. The idea that a survey of 50 specialists will accurately reflect the work may be at times incorrect. If a procedure is performed a few thousand times a year, 50 surveys may be sufficient, but other codes performed millions of times a year such as cardiac catheterization, colonoscopy, or hernia repair I believe need more evaluation than 50 surveys.

The proposed change to make the survey uniform is problematic. There is great variation in procedures, and I find it difficult to think a psychiatric session could be evaluated with the same form as a pediatric cardiac procedure. Regularly, an "expert panel," usually the coding and reimbursement committee of the medical specialties, reviews work and can often help tease out the type of survey and the numbers needed for a particular code. With the process now being undertaken by the AMA with a centralized online tool, the specialties will lose that ability.

Clearly the RUC is far from perfect. Many of the objections, however, are based on perceptions, not the realities, of the process. The chair of the RUC has stated that she has never turned down a request to attend an RUC meeting. Transparency may appear as a solution to perceptions of secrecy and self-interest of specialties, but comes with its own set of problems. Using a group of surveys to value work is less than perfect and making the survey uniform will, in my opinion, make accurate valuation more difficult. That said, I do not believe any other body in existence or proposed could assume the work of the RUC. The specialties and the AMA pay for the whole process and then present the many hours of work to CMS without charge. I seriously doubt a group of economists, public health experts, or even other health care providers could accurately determine the amount of work required for a specific procedure. Only physicians have the skill set, experience, and knowledge to do this.

Dr. Rubin is an ACS Fellow, chair of the ACS General Surgery Coding and Reimbursement Committee and alternate delegate of the AMA Relative Value Update Committee.

Recent changes in the Relative Value Update Committee process are going to have an impact on the committee’s work and output. Surgeons need to know what these changes may mean for our profession.

The RUC is a committee convened by the American Medical Association and composed of representatives of all the major medical specialties who meet to analyze in medical procedures and other work of physicians. Most specialties have four committee members: a delegate and alternate delegate who help deliberate the relative value of CPT codes, and an advisor and alternate advisor who present codes pertinent to the specialty they represent. The RUC does not determine monetary value of the work it reviews. The job of assigning payment rates is left to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid. CMS takes into consideration the recommendation of relative work by the RUC and applies a complex algorithm to arrive at a payment schedule.

A forceful argument against the current RUC process is that of "the fox guarding the henhouse." In other words, the physicians are seen as setting their own payment. This is a misunderstanding or perhaps a misrepresentation of the way the RUC works. The RUC recommends, but CMS may or may not accept the recommendations. In the past CMS has accepted the RUC recommendations 90%-95% of the time. Last year CMS accepted only 75% of the recommendations. This trend is of interest to surgeons because most of the recommendations concerned surgical procedures. Many were "bread and butter" general surgical procedures such as thyroid, and as one might guess, CMS lowered the values.

The work done by the RUC is extremely deliberative and requires careful consideration and fairness by dedicated committee members. In addition, physicians’ work is very technical and requires specialized knowledge that only physicians can bring to the process. I cannot imagine an economist trying to determine the work, the intensity, the number of hospital visits, or the number of office visits for any procedure. Who can analyze the amount and type of work involved in medical practice better than those who actually do the work?

The RUC has proposed and implemented new rules in regard to transparency. Transparency in this context, however, is a double-edged sword. While transparency allows citizens and leaders to get a feel for the process, full disclosure of the discussions and debates involved runs the risk of interfering with that process. There can be tremendous medical, legal, financial and political consequences of the recommendations of the RUC, and it would not be unreasonable to expect significant attempts by a variety of actors to influence the process.

Making the RUC votes public may improve understanding of the RUC, but it could also work to the detriment of the committee’s process.

A two-thirds majority is needed for passage of a work value, and many specialties must agree each time a code passes. If individual votes are made public, the committee members are not protected from pressure from outside actors. Often specialties will vote to increase a code of another specialty. In a budget-neutral system, if your codes go up, mine go down.

Making the vote transparent may prevent a delegate from truly being deliberative to appear more supportive of his or her own specialty. Indeed, the specialty groups could monitor the votes to ensure the codes are "protected," and this has the potential to change the delegate from a "deliberator" to a protector of his or her specialty. That is not the role of the delegate. While I support the publication of the votes in aggregate, I do not support the individual votes for this reason.

There is no doubt that changes are needed. The idea that a survey of 50 specialists will accurately reflect the work may be at times incorrect. If a procedure is performed a few thousand times a year, 50 surveys may be sufficient, but other codes performed millions of times a year such as cardiac catheterization, colonoscopy, or hernia repair I believe need more evaluation than 50 surveys.