User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

Mobile health validation efforts in infancy

Hardly a day goes by anymore without an announcement of a new mobile health app, but there are precious few data to show which apps are useful in clinical or financial terms. Lots of people would like to change that, but how?

Three experts offered ideas in a recent opinion article in the Journal of the American Medical Association, and some partnerships between academia and industry may be laying the groundwork for greater validation of new mobile health (mHealth) tools.

Of the more than 40,000 health, fitness, and medical apps on the market, reviews "have largely focused on personal impressions, rather than evidence-based, unbiased assessments of clinical performance and data security," Adam C. Powell, Ph.D., Dr. Adam B. Landman, and Dr. David W. Bates wrote in their article, "In Search of a Few Good Apps" (JAMA 2014;311:1851-2).

The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) could play a greater role supporting development of mHealth app guidelines and, eventually, commission non-profit or for-profit entities to certify apps, as it does now for electronic health records, they suggested.

Dr. Powell is a Boston-based consultant. Dr. Landman, an emergency medicine specialist, is chief medical information officer for health information innovation and integration at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. Dr. Bates is chief of general internal medicine and the chief quality officer at Brigham and Women’s. Dr. Landman and Dr. Bates are both at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

The National Institutes of Health mHealth Training Institute is educating an interdisciplinary group of researchers about the potential of mHealth and the need to evaluate these new tools. "If this effort is coupled with increased funding for mHealth research, it may help galvanize a larger body of evidence to inform mHealth app development and certification," the authors wrote.

Meanwhile, a new partnership between the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), and Samsung Electronics aims to validate and commercialize promising digital tools for health care, including apps, in a Digital Health Innovation Lab. A few other universities recently entered into similar partnerships with industry.

Both UCSF and Samsung are making a "significant investment" to fund the lab but are not ready to release financial details, Dr. Michael Blum said in an interview.

The partnership initially will focus on preventive health, said Dr. Blum, who will direct the lab to be located at UCSF’s Mission Bay campus. "There is no better way to treat disease than by avoiding it in the first place. [Moe than] 70% of our health care dollars are spent on avoidable disease," said Dr. Blum, a cardiologist who has been leading UCSF’s relatively new Center for Digital Health Innovation.

UCSF already has begun testing medical apps in clinical trials, such as a smoking cessation app, and will pursue clinical testing of tools including health sensors, wearable computing, and cloud-based analytics.

"There are many sites designing medical apps but very few are rigorously validated," Dr. Blum said. "We believe that validation is critical to the success of these apps and products. It is important for health care providers to know that they can trust the data and information which will lead to more consistent use and, hopefully, better outcomes for the users."

In Michigan, the William Davidson Foundation in January 2014 awarded $3 million to the Henry Ford Health System to create the William Davidson Center for Entrepreneurs in Digital Health. The center hopes to attract corporate partners and others to create, clinically validate, and commercialize digital health tools and to create a curriculum integrating health care, digital technologies, and entrepreneurship, according to a statement released by the Henry Ford Innovation Institute.

At the University of Colorado, Denver, the Center for Information Technology Innovation recently launched a Digital Health Consortium to bring its business school faculty together with entrepreneurs, health care providers, researchers, educators, and others to develop and clinically validate the next generation of digital health tools. The Center is funded by its members, which include the university and more than 30 Colorado information technology business leaders.

As each of these initiatives and others like them report results from their validation efforts, we’ll bring you the latest news on medical apps. Watch this space.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

Hardly a day goes by anymore without an announcement of a new mobile health app, but there are precious few data to show which apps are useful in clinical or financial terms. Lots of people would like to change that, but how?

Three experts offered ideas in a recent opinion article in the Journal of the American Medical Association, and some partnerships between academia and industry may be laying the groundwork for greater validation of new mobile health (mHealth) tools.

Of the more than 40,000 health, fitness, and medical apps on the market, reviews "have largely focused on personal impressions, rather than evidence-based, unbiased assessments of clinical performance and data security," Adam C. Powell, Ph.D., Dr. Adam B. Landman, and Dr. David W. Bates wrote in their article, "In Search of a Few Good Apps" (JAMA 2014;311:1851-2).

The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) could play a greater role supporting development of mHealth app guidelines and, eventually, commission non-profit or for-profit entities to certify apps, as it does now for electronic health records, they suggested.

Dr. Powell is a Boston-based consultant. Dr. Landman, an emergency medicine specialist, is chief medical information officer for health information innovation and integration at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. Dr. Bates is chief of general internal medicine and the chief quality officer at Brigham and Women’s. Dr. Landman and Dr. Bates are both at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

The National Institutes of Health mHealth Training Institute is educating an interdisciplinary group of researchers about the potential of mHealth and the need to evaluate these new tools. "If this effort is coupled with increased funding for mHealth research, it may help galvanize a larger body of evidence to inform mHealth app development and certification," the authors wrote.

Meanwhile, a new partnership between the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), and Samsung Electronics aims to validate and commercialize promising digital tools for health care, including apps, in a Digital Health Innovation Lab. A few other universities recently entered into similar partnerships with industry.

Both UCSF and Samsung are making a "significant investment" to fund the lab but are not ready to release financial details, Dr. Michael Blum said in an interview.

The partnership initially will focus on preventive health, said Dr. Blum, who will direct the lab to be located at UCSF’s Mission Bay campus. "There is no better way to treat disease than by avoiding it in the first place. [Moe than] 70% of our health care dollars are spent on avoidable disease," said Dr. Blum, a cardiologist who has been leading UCSF’s relatively new Center for Digital Health Innovation.

UCSF already has begun testing medical apps in clinical trials, such as a smoking cessation app, and will pursue clinical testing of tools including health sensors, wearable computing, and cloud-based analytics.

"There are many sites designing medical apps but very few are rigorously validated," Dr. Blum said. "We believe that validation is critical to the success of these apps and products. It is important for health care providers to know that they can trust the data and information which will lead to more consistent use and, hopefully, better outcomes for the users."

In Michigan, the William Davidson Foundation in January 2014 awarded $3 million to the Henry Ford Health System to create the William Davidson Center for Entrepreneurs in Digital Health. The center hopes to attract corporate partners and others to create, clinically validate, and commercialize digital health tools and to create a curriculum integrating health care, digital technologies, and entrepreneurship, according to a statement released by the Henry Ford Innovation Institute.

At the University of Colorado, Denver, the Center for Information Technology Innovation recently launched a Digital Health Consortium to bring its business school faculty together with entrepreneurs, health care providers, researchers, educators, and others to develop and clinically validate the next generation of digital health tools. The Center is funded by its members, which include the university and more than 30 Colorado information technology business leaders.

As each of these initiatives and others like them report results from their validation efforts, we’ll bring you the latest news on medical apps. Watch this space.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

Hardly a day goes by anymore without an announcement of a new mobile health app, but there are precious few data to show which apps are useful in clinical or financial terms. Lots of people would like to change that, but how?

Three experts offered ideas in a recent opinion article in the Journal of the American Medical Association, and some partnerships between academia and industry may be laying the groundwork for greater validation of new mobile health (mHealth) tools.

Of the more than 40,000 health, fitness, and medical apps on the market, reviews "have largely focused on personal impressions, rather than evidence-based, unbiased assessments of clinical performance and data security," Adam C. Powell, Ph.D., Dr. Adam B. Landman, and Dr. David W. Bates wrote in their article, "In Search of a Few Good Apps" (JAMA 2014;311:1851-2).

The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) could play a greater role supporting development of mHealth app guidelines and, eventually, commission non-profit or for-profit entities to certify apps, as it does now for electronic health records, they suggested.

Dr. Powell is a Boston-based consultant. Dr. Landman, an emergency medicine specialist, is chief medical information officer for health information innovation and integration at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. Dr. Bates is chief of general internal medicine and the chief quality officer at Brigham and Women’s. Dr. Landman and Dr. Bates are both at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

The National Institutes of Health mHealth Training Institute is educating an interdisciplinary group of researchers about the potential of mHealth and the need to evaluate these new tools. "If this effort is coupled with increased funding for mHealth research, it may help galvanize a larger body of evidence to inform mHealth app development and certification," the authors wrote.

Meanwhile, a new partnership between the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), and Samsung Electronics aims to validate and commercialize promising digital tools for health care, including apps, in a Digital Health Innovation Lab. A few other universities recently entered into similar partnerships with industry.

Both UCSF and Samsung are making a "significant investment" to fund the lab but are not ready to release financial details, Dr. Michael Blum said in an interview.

The partnership initially will focus on preventive health, said Dr. Blum, who will direct the lab to be located at UCSF’s Mission Bay campus. "There is no better way to treat disease than by avoiding it in the first place. [Moe than] 70% of our health care dollars are spent on avoidable disease," said Dr. Blum, a cardiologist who has been leading UCSF’s relatively new Center for Digital Health Innovation.

UCSF already has begun testing medical apps in clinical trials, such as a smoking cessation app, and will pursue clinical testing of tools including health sensors, wearable computing, and cloud-based analytics.

"There are many sites designing medical apps but very few are rigorously validated," Dr. Blum said. "We believe that validation is critical to the success of these apps and products. It is important for health care providers to know that they can trust the data and information which will lead to more consistent use and, hopefully, better outcomes for the users."

In Michigan, the William Davidson Foundation in January 2014 awarded $3 million to the Henry Ford Health System to create the William Davidson Center for Entrepreneurs in Digital Health. The center hopes to attract corporate partners and others to create, clinically validate, and commercialize digital health tools and to create a curriculum integrating health care, digital technologies, and entrepreneurship, according to a statement released by the Henry Ford Innovation Institute.

At the University of Colorado, Denver, the Center for Information Technology Innovation recently launched a Digital Health Consortium to bring its business school faculty together with entrepreneurs, health care providers, researchers, educators, and others to develop and clinically validate the next generation of digital health tools. The Center is funded by its members, which include the university and more than 30 Colorado information technology business leaders.

As each of these initiatives and others like them report results from their validation efforts, we’ll bring you the latest news on medical apps. Watch this space.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

AMA calls for ‘course correction’ on meaningful use

Doctors will continue to drop out of the federal government’s Electronic Health Records Incentive Programs unless officials ease some program requirements, the American Medical Association warned in a May 8 letter to government officials.

The AMA offered a laundry list of needed changes from abandoning the "all-or-nothing" approach for meeting meaningful use standards to removing requirements that are outside the control of physicians.

"In any other grading system a 99% is an A+, but it’s a fail in the meaningful use program, which just seems entirely inconsistent with what Congress intended, which was to foster the adoption of these tools," Dr. Steven J. Stack, an emergency physician and immediate past chairman of the AMA’s board of trustees, said in an interview.

In the letter to officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), the AMA advocated for ending the "all-or-nothing" approach, which requires physicians to successfully meet all meaningful use requirements to earn incentives. The AMA instead recommended a 75% threshold for qualifying for incentives and a 50% threshold to avoid penalties.

The AMA also urged the government not to measure activities outside of the physician’s control, such as whether a patient views or downloads information from a portal.

While the government has been touting widespread participation in the Electronic Health Records Incentive Programs, the AMA said that physicians are beginning to abandon the program. The AMA said that partial data from 2013 showed that there was already a 20% drop out rate in the meaningful use program. It will only grow if the program continues as is, Dr. Stack said.

But there’s time to make changes both to Stage 2 and Stage 3 of the program, Dr. Stack added.

"We don’t see this as a done deal. We see this as a live program that requires ongoing adjustment and tailoring," he said. "The federal government, in order to advance the policy objective of fostering electronic health record adoption and health information exchange, should have a mid-course correction immediately for Stage 2 to make it more possible to have flexibility and a better opportunity for success for the clinicians and the hospitals."

On Twitter @maryellenny

Doctors will continue to drop out of the federal government’s Electronic Health Records Incentive Programs unless officials ease some program requirements, the American Medical Association warned in a May 8 letter to government officials.

The AMA offered a laundry list of needed changes from abandoning the "all-or-nothing" approach for meeting meaningful use standards to removing requirements that are outside the control of physicians.

"In any other grading system a 99% is an A+, but it’s a fail in the meaningful use program, which just seems entirely inconsistent with what Congress intended, which was to foster the adoption of these tools," Dr. Steven J. Stack, an emergency physician and immediate past chairman of the AMA’s board of trustees, said in an interview.

In the letter to officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), the AMA advocated for ending the "all-or-nothing" approach, which requires physicians to successfully meet all meaningful use requirements to earn incentives. The AMA instead recommended a 75% threshold for qualifying for incentives and a 50% threshold to avoid penalties.

The AMA also urged the government not to measure activities outside of the physician’s control, such as whether a patient views or downloads information from a portal.

While the government has been touting widespread participation in the Electronic Health Records Incentive Programs, the AMA said that physicians are beginning to abandon the program. The AMA said that partial data from 2013 showed that there was already a 20% drop out rate in the meaningful use program. It will only grow if the program continues as is, Dr. Stack said.

But there’s time to make changes both to Stage 2 and Stage 3 of the program, Dr. Stack added.

"We don’t see this as a done deal. We see this as a live program that requires ongoing adjustment and tailoring," he said. "The federal government, in order to advance the policy objective of fostering electronic health record adoption and health information exchange, should have a mid-course correction immediately for Stage 2 to make it more possible to have flexibility and a better opportunity for success for the clinicians and the hospitals."

On Twitter @maryellenny

Doctors will continue to drop out of the federal government’s Electronic Health Records Incentive Programs unless officials ease some program requirements, the American Medical Association warned in a May 8 letter to government officials.

The AMA offered a laundry list of needed changes from abandoning the "all-or-nothing" approach for meeting meaningful use standards to removing requirements that are outside the control of physicians.

"In any other grading system a 99% is an A+, but it’s a fail in the meaningful use program, which just seems entirely inconsistent with what Congress intended, which was to foster the adoption of these tools," Dr. Steven J. Stack, an emergency physician and immediate past chairman of the AMA’s board of trustees, said in an interview.

In the letter to officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), the AMA advocated for ending the "all-or-nothing" approach, which requires physicians to successfully meet all meaningful use requirements to earn incentives. The AMA instead recommended a 75% threshold for qualifying for incentives and a 50% threshold to avoid penalties.

The AMA also urged the government not to measure activities outside of the physician’s control, such as whether a patient views or downloads information from a portal.

While the government has been touting widespread participation in the Electronic Health Records Incentive Programs, the AMA said that physicians are beginning to abandon the program. The AMA said that partial data from 2013 showed that there was already a 20% drop out rate in the meaningful use program. It will only grow if the program continues as is, Dr. Stack said.

But there’s time to make changes both to Stage 2 and Stage 3 of the program, Dr. Stack added.

"We don’t see this as a done deal. We see this as a live program that requires ongoing adjustment and tailoring," he said. "The federal government, in order to advance the policy objective of fostering electronic health record adoption and health information exchange, should have a mid-course correction immediately for Stage 2 to make it more possible to have flexibility and a better opportunity for success for the clinicians and the hospitals."

On Twitter @maryellenny

Law & Medicine: Antitrust issues in health care, part 2

Question: On antitrust, the U.S. courts have made the following statements, except:

A. To agree to prices is to fix them.

B. There is no learned profession exception to the antitrust laws.

C. To fix maximum price may amount to a fix of minimum price.

D. A group boycott of chiropractors violates the Sherman Act.

E. Tying arrangement in the health care industry is per se illegal.

Answer: E (see Jefferson Parish Hospital below). In the second part of the 20th century, the U.S. Supreme Court and other appellate courts began issuing a number of landmark opinions regarding health care economics and antitrust. Group boycotts were a major target, as was price fixing. This article briefly reviews a few of these decisions to impart a sense of how the judicial system views free market competition in health care.

In AMA v. United States (317 U.S. 519 [1943]), the issue was whether the medical profession’s leading organization, the American Medical Association, could be allowed to expel its salaried doctors or those who associated professionally with salaried doctors. Those who were denied AMA membership were naturally less able to compete (hospital privileges, consultations, etc.).

The U.S. Supreme Court held that such a group boycott of all salaried doctors was illegal because of its anticompetitive purpose, even if it allegedly promoted professional competence and public welfare.

Wilk v. AMA (895 F.2d 352 [1990]) was the culmination of a number of lawsuits surrounding the AMA and chiropractic. In 1963, the AMA had formed a Committee on Quackery aimed at eliminating chiropractic as a profession. The AMA Code of Ethics, Principle 3, opined that it was unethical for a physician to associate professionally with chiropractors. In 1976, Dr. Wilk and four other licensed chiropractors filed suit against the AMA, and a jury trial found that the purpose of the boycott was to eliminate substantial competition without corresponding procompetitive benefits.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit subsequently affirmed the lower court’s finding that the AMA violated Section 1 of the Sherman Act in its illegal boycott of chiropractors, although the court did not answer the question as to whether chiropractic theory was in fact scientific. The court inquired into whether there was a genuine reasonable concern for the use of the scientific method in the doctor-patient relationship, and whether that concern was the dominating, motivating factor in the boycott, and if so, whether it could have been satisfied without restraining competition.

The court found that the AMA’s motive for the boycott was anticompetitive, believing that concern for patient care could be expressed, for example, through public-education campaigns. Although the AMA had formally removed Principle 3 in 1980, it nonetheless appealed this adverse decision to the U.S. Supreme Court on three separate occasions, but the latter declined to hear the case.

In Goldfarb v. Virginia State Bar (421 U.S. 773 [1975]), the Virginia State Bar enforced an "advisory" minimum fee schedule for legal services. The U.S. Supreme Court found that this was an agreement to fix prices, holding, "This is not merely a case of an agreement that may be inferred from an exchange of price information ... for here a naked agreement was clearly shown, and the effect on prices is plain."

The court rejected the defendant’s argument that the practice of law was not a trade or commerce intended to be under Sherman Act scrutiny, declaring there was to be no "learned profession" exemption.

However, it noted that special considerations might apply, holding that "It would be unrealistic to view the practice of professions as interchangeable with other business activities, and automatically to apply to the professions antitrust concepts, which originated in other areas. The public service aspect, and other features of the professions, may require that a particular practice, which could properly be viewed as a violation of the Sherman Act in another context, be treated differently."

Following Goldfarb, there remains no doubt that professional services – legal, medical, and other services – are all to be governed by the antitrust laws.

A flurry of health care–related antitrust cases, including Patrick v. Burget (to be discussed in part 3), reached the courts in the 1980s. In Arizona v. Maricopa County Medical Society (457 U.S. 332 [1982]), the county medical society set maximum allowable fees that member physicians could charge their patients, presumably to guard against price gouging. However, the U.S. Supreme Court, using the tough illegal per se standard, characterized the agreement as price fixing, despite it being for maximum rather than minimum fees.

The court ruled, "Maximum and minimum price fixing may have different consequences in many situations. But schemes to fix maximum prices, by substituting perhaps the erroneous judgment of a seller for the forces of the competitive market, may severely intrude upon the ability of buyers to compete and survive in that market. ... Maximum prices may be fixed too low ... may channel distribution through a few large or specifically advantaged dealers. ... Moreover, if the actual price charged under a maximum price scheme is nearly always the fixed maximum price, which is increasingly likely as the maximum price approaches the actual cost of the dealer, the scheme tends to acquire all the attributes of an arrangement fixing minimum prices."

At issue in Jefferson Parish Hospital District No. 2 v. Hyde (466 U.S. 2 [1984]) was an exclusive contract between a group of four anesthesiologists and Jefferson Parish Hospital in the New Orleans area. Dr. Hyde was an independent board-certified anesthesiologist who was denied medical staff privileges at the hospital because of this exclusive contract. The exclusive arrangement in effect required patients at the hospital to use the services of the four anesthesiologists and none others, raising the issue of unlawful "tying," where a seller requires a customer to purchase one product or service as a condition of being allowed to purchase another.

In a rare unanimous decision, the U.S. Supreme Court, while agreeing that the contract was a tying arrangement, nonetheless rejected the argument that it was per se illegal or that it unreasonably restrained competition among anesthesiologists. The court reasoned that the hospital’s 30% share of the market did not amount to sufficient market power in the provision of hospital services in the Jefferson Parish area. Pointing out that every patient undergoing surgery needed anesthesia, the court found no evidence that any patient received unnecessary services, and it noted that the tying arrangement that was generally employed in the health care industry improved patient care and promoted hospital efficiency.

Tying arrangements in health care are frequently analyzed under a rule of reason standard instead of the strict per se standard, and the favorable decision in this specific case depended heavily on the hospitals’ relatively small market power.

Finally, consider a case on insurance reimbursement and a group boycott against a third-party payer. In Federal Trade Commission v. Indiana Federation of Dentists (476 U.S. 447 [1986]), dental health insurers in Indiana attempted to contain the cost of dental treatment by limiting payments to the least expensive yet adequate treatment suitable to the needs of the patient. The insurers required the submission of x-rays by treating dentists for review of their insurance claims.

Viewing such review of diagnostic and treatment decisions as a threat to their professional independence and economic well-being, members of the Indiana Dental Association and later the Indiana Federation of Dentists agreed collectively to refuse to submit the requested x-rays. These concerted activities resulted in the denial of information that dental customers had requested and had a right to know, and forced them to choose between acquiring the information in a more costly manner or forgoing it altogether.

The lower court had ruled in favor of the dentists, but the U.S. Supreme Court reversed. It agreed that in the absence of concerted behavior, an individual dentist would have been subject to market forces of competition, creating incentives for him or her to comply with the requests of patients’ third-party insurers. But the conduct of the federation was tantamount to a group boycott, which unreasonably restrained trade. The court noted that while this was not price fixing as such, no elaborate industry analysis was required to demonstrate the anticompetitive character of such an agreement.

Dr. Tan is professor emeritus of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some of the articles in this series are adapted from the author’s 2006 book, "Medical Malpractice: Understanding the Law, Managing the Risk", and his 2012 Halsbury treatise, "Medical Negligence and Professional Misconduct." For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

Question: On antitrust, the U.S. courts have made the following statements, except:

A. To agree to prices is to fix them.

B. There is no learned profession exception to the antitrust laws.

C. To fix maximum price may amount to a fix of minimum price.

D. A group boycott of chiropractors violates the Sherman Act.

E. Tying arrangement in the health care industry is per se illegal.

Answer: E (see Jefferson Parish Hospital below). In the second part of the 20th century, the U.S. Supreme Court and other appellate courts began issuing a number of landmark opinions regarding health care economics and antitrust. Group boycotts were a major target, as was price fixing. This article briefly reviews a few of these decisions to impart a sense of how the judicial system views free market competition in health care.

In AMA v. United States (317 U.S. 519 [1943]), the issue was whether the medical profession’s leading organization, the American Medical Association, could be allowed to expel its salaried doctors or those who associated professionally with salaried doctors. Those who were denied AMA membership were naturally less able to compete (hospital privileges, consultations, etc.).

The U.S. Supreme Court held that such a group boycott of all salaried doctors was illegal because of its anticompetitive purpose, even if it allegedly promoted professional competence and public welfare.

Wilk v. AMA (895 F.2d 352 [1990]) was the culmination of a number of lawsuits surrounding the AMA and chiropractic. In 1963, the AMA had formed a Committee on Quackery aimed at eliminating chiropractic as a profession. The AMA Code of Ethics, Principle 3, opined that it was unethical for a physician to associate professionally with chiropractors. In 1976, Dr. Wilk and four other licensed chiropractors filed suit against the AMA, and a jury trial found that the purpose of the boycott was to eliminate substantial competition without corresponding procompetitive benefits.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit subsequently affirmed the lower court’s finding that the AMA violated Section 1 of the Sherman Act in its illegal boycott of chiropractors, although the court did not answer the question as to whether chiropractic theory was in fact scientific. The court inquired into whether there was a genuine reasonable concern for the use of the scientific method in the doctor-patient relationship, and whether that concern was the dominating, motivating factor in the boycott, and if so, whether it could have been satisfied without restraining competition.

The court found that the AMA’s motive for the boycott was anticompetitive, believing that concern for patient care could be expressed, for example, through public-education campaigns. Although the AMA had formally removed Principle 3 in 1980, it nonetheless appealed this adverse decision to the U.S. Supreme Court on three separate occasions, but the latter declined to hear the case.

In Goldfarb v. Virginia State Bar (421 U.S. 773 [1975]), the Virginia State Bar enforced an "advisory" minimum fee schedule for legal services. The U.S. Supreme Court found that this was an agreement to fix prices, holding, "This is not merely a case of an agreement that may be inferred from an exchange of price information ... for here a naked agreement was clearly shown, and the effect on prices is plain."

The court rejected the defendant’s argument that the practice of law was not a trade or commerce intended to be under Sherman Act scrutiny, declaring there was to be no "learned profession" exemption.

However, it noted that special considerations might apply, holding that "It would be unrealistic to view the practice of professions as interchangeable with other business activities, and automatically to apply to the professions antitrust concepts, which originated in other areas. The public service aspect, and other features of the professions, may require that a particular practice, which could properly be viewed as a violation of the Sherman Act in another context, be treated differently."

Following Goldfarb, there remains no doubt that professional services – legal, medical, and other services – are all to be governed by the antitrust laws.

A flurry of health care–related antitrust cases, including Patrick v. Burget (to be discussed in part 3), reached the courts in the 1980s. In Arizona v. Maricopa County Medical Society (457 U.S. 332 [1982]), the county medical society set maximum allowable fees that member physicians could charge their patients, presumably to guard against price gouging. However, the U.S. Supreme Court, using the tough illegal per se standard, characterized the agreement as price fixing, despite it being for maximum rather than minimum fees.

The court ruled, "Maximum and minimum price fixing may have different consequences in many situations. But schemes to fix maximum prices, by substituting perhaps the erroneous judgment of a seller for the forces of the competitive market, may severely intrude upon the ability of buyers to compete and survive in that market. ... Maximum prices may be fixed too low ... may channel distribution through a few large or specifically advantaged dealers. ... Moreover, if the actual price charged under a maximum price scheme is nearly always the fixed maximum price, which is increasingly likely as the maximum price approaches the actual cost of the dealer, the scheme tends to acquire all the attributes of an arrangement fixing minimum prices."

At issue in Jefferson Parish Hospital District No. 2 v. Hyde (466 U.S. 2 [1984]) was an exclusive contract between a group of four anesthesiologists and Jefferson Parish Hospital in the New Orleans area. Dr. Hyde was an independent board-certified anesthesiologist who was denied medical staff privileges at the hospital because of this exclusive contract. The exclusive arrangement in effect required patients at the hospital to use the services of the four anesthesiologists and none others, raising the issue of unlawful "tying," where a seller requires a customer to purchase one product or service as a condition of being allowed to purchase another.

In a rare unanimous decision, the U.S. Supreme Court, while agreeing that the contract was a tying arrangement, nonetheless rejected the argument that it was per se illegal or that it unreasonably restrained competition among anesthesiologists. The court reasoned that the hospital’s 30% share of the market did not amount to sufficient market power in the provision of hospital services in the Jefferson Parish area. Pointing out that every patient undergoing surgery needed anesthesia, the court found no evidence that any patient received unnecessary services, and it noted that the tying arrangement that was generally employed in the health care industry improved patient care and promoted hospital efficiency.

Tying arrangements in health care are frequently analyzed under a rule of reason standard instead of the strict per se standard, and the favorable decision in this specific case depended heavily on the hospitals’ relatively small market power.

Finally, consider a case on insurance reimbursement and a group boycott against a third-party payer. In Federal Trade Commission v. Indiana Federation of Dentists (476 U.S. 447 [1986]), dental health insurers in Indiana attempted to contain the cost of dental treatment by limiting payments to the least expensive yet adequate treatment suitable to the needs of the patient. The insurers required the submission of x-rays by treating dentists for review of their insurance claims.

Viewing such review of diagnostic and treatment decisions as a threat to their professional independence and economic well-being, members of the Indiana Dental Association and later the Indiana Federation of Dentists agreed collectively to refuse to submit the requested x-rays. These concerted activities resulted in the denial of information that dental customers had requested and had a right to know, and forced them to choose between acquiring the information in a more costly manner or forgoing it altogether.

The lower court had ruled in favor of the dentists, but the U.S. Supreme Court reversed. It agreed that in the absence of concerted behavior, an individual dentist would have been subject to market forces of competition, creating incentives for him or her to comply with the requests of patients’ third-party insurers. But the conduct of the federation was tantamount to a group boycott, which unreasonably restrained trade. The court noted that while this was not price fixing as such, no elaborate industry analysis was required to demonstrate the anticompetitive character of such an agreement.

Dr. Tan is professor emeritus of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some of the articles in this series are adapted from the author’s 2006 book, "Medical Malpractice: Understanding the Law, Managing the Risk", and his 2012 Halsbury treatise, "Medical Negligence and Professional Misconduct." For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

Question: On antitrust, the U.S. courts have made the following statements, except:

A. To agree to prices is to fix them.

B. There is no learned profession exception to the antitrust laws.

C. To fix maximum price may amount to a fix of minimum price.

D. A group boycott of chiropractors violates the Sherman Act.

E. Tying arrangement in the health care industry is per se illegal.

Answer: E (see Jefferson Parish Hospital below). In the second part of the 20th century, the U.S. Supreme Court and other appellate courts began issuing a number of landmark opinions regarding health care economics and antitrust. Group boycotts were a major target, as was price fixing. This article briefly reviews a few of these decisions to impart a sense of how the judicial system views free market competition in health care.

In AMA v. United States (317 U.S. 519 [1943]), the issue was whether the medical profession’s leading organization, the American Medical Association, could be allowed to expel its salaried doctors or those who associated professionally with salaried doctors. Those who were denied AMA membership were naturally less able to compete (hospital privileges, consultations, etc.).

The U.S. Supreme Court held that such a group boycott of all salaried doctors was illegal because of its anticompetitive purpose, even if it allegedly promoted professional competence and public welfare.

Wilk v. AMA (895 F.2d 352 [1990]) was the culmination of a number of lawsuits surrounding the AMA and chiropractic. In 1963, the AMA had formed a Committee on Quackery aimed at eliminating chiropractic as a profession. The AMA Code of Ethics, Principle 3, opined that it was unethical for a physician to associate professionally with chiropractors. In 1976, Dr. Wilk and four other licensed chiropractors filed suit against the AMA, and a jury trial found that the purpose of the boycott was to eliminate substantial competition without corresponding procompetitive benefits.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit subsequently affirmed the lower court’s finding that the AMA violated Section 1 of the Sherman Act in its illegal boycott of chiropractors, although the court did not answer the question as to whether chiropractic theory was in fact scientific. The court inquired into whether there was a genuine reasonable concern for the use of the scientific method in the doctor-patient relationship, and whether that concern was the dominating, motivating factor in the boycott, and if so, whether it could have been satisfied without restraining competition.

The court found that the AMA’s motive for the boycott was anticompetitive, believing that concern for patient care could be expressed, for example, through public-education campaigns. Although the AMA had formally removed Principle 3 in 1980, it nonetheless appealed this adverse decision to the U.S. Supreme Court on three separate occasions, but the latter declined to hear the case.

In Goldfarb v. Virginia State Bar (421 U.S. 773 [1975]), the Virginia State Bar enforced an "advisory" minimum fee schedule for legal services. The U.S. Supreme Court found that this was an agreement to fix prices, holding, "This is not merely a case of an agreement that may be inferred from an exchange of price information ... for here a naked agreement was clearly shown, and the effect on prices is plain."

The court rejected the defendant’s argument that the practice of law was not a trade or commerce intended to be under Sherman Act scrutiny, declaring there was to be no "learned profession" exemption.

However, it noted that special considerations might apply, holding that "It would be unrealistic to view the practice of professions as interchangeable with other business activities, and automatically to apply to the professions antitrust concepts, which originated in other areas. The public service aspect, and other features of the professions, may require that a particular practice, which could properly be viewed as a violation of the Sherman Act in another context, be treated differently."

Following Goldfarb, there remains no doubt that professional services – legal, medical, and other services – are all to be governed by the antitrust laws.

A flurry of health care–related antitrust cases, including Patrick v. Burget (to be discussed in part 3), reached the courts in the 1980s. In Arizona v. Maricopa County Medical Society (457 U.S. 332 [1982]), the county medical society set maximum allowable fees that member physicians could charge their patients, presumably to guard against price gouging. However, the U.S. Supreme Court, using the tough illegal per se standard, characterized the agreement as price fixing, despite it being for maximum rather than minimum fees.

The court ruled, "Maximum and minimum price fixing may have different consequences in many situations. But schemes to fix maximum prices, by substituting perhaps the erroneous judgment of a seller for the forces of the competitive market, may severely intrude upon the ability of buyers to compete and survive in that market. ... Maximum prices may be fixed too low ... may channel distribution through a few large or specifically advantaged dealers. ... Moreover, if the actual price charged under a maximum price scheme is nearly always the fixed maximum price, which is increasingly likely as the maximum price approaches the actual cost of the dealer, the scheme tends to acquire all the attributes of an arrangement fixing minimum prices."

At issue in Jefferson Parish Hospital District No. 2 v. Hyde (466 U.S. 2 [1984]) was an exclusive contract between a group of four anesthesiologists and Jefferson Parish Hospital in the New Orleans area. Dr. Hyde was an independent board-certified anesthesiologist who was denied medical staff privileges at the hospital because of this exclusive contract. The exclusive arrangement in effect required patients at the hospital to use the services of the four anesthesiologists and none others, raising the issue of unlawful "tying," where a seller requires a customer to purchase one product or service as a condition of being allowed to purchase another.

In a rare unanimous decision, the U.S. Supreme Court, while agreeing that the contract was a tying arrangement, nonetheless rejected the argument that it was per se illegal or that it unreasonably restrained competition among anesthesiologists. The court reasoned that the hospital’s 30% share of the market did not amount to sufficient market power in the provision of hospital services in the Jefferson Parish area. Pointing out that every patient undergoing surgery needed anesthesia, the court found no evidence that any patient received unnecessary services, and it noted that the tying arrangement that was generally employed in the health care industry improved patient care and promoted hospital efficiency.

Tying arrangements in health care are frequently analyzed under a rule of reason standard instead of the strict per se standard, and the favorable decision in this specific case depended heavily on the hospitals’ relatively small market power.

Finally, consider a case on insurance reimbursement and a group boycott against a third-party payer. In Federal Trade Commission v. Indiana Federation of Dentists (476 U.S. 447 [1986]), dental health insurers in Indiana attempted to contain the cost of dental treatment by limiting payments to the least expensive yet adequate treatment suitable to the needs of the patient. The insurers required the submission of x-rays by treating dentists for review of their insurance claims.

Viewing such review of diagnostic and treatment decisions as a threat to their professional independence and economic well-being, members of the Indiana Dental Association and later the Indiana Federation of Dentists agreed collectively to refuse to submit the requested x-rays. These concerted activities resulted in the denial of information that dental customers had requested and had a right to know, and forced them to choose between acquiring the information in a more costly manner or forgoing it altogether.

The lower court had ruled in favor of the dentists, but the U.S. Supreme Court reversed. It agreed that in the absence of concerted behavior, an individual dentist would have been subject to market forces of competition, creating incentives for him or her to comply with the requests of patients’ third-party insurers. But the conduct of the federation was tantamount to a group boycott, which unreasonably restrained trade. The court noted that while this was not price fixing as such, no elaborate industry analysis was required to demonstrate the anticompetitive character of such an agreement.

Dr. Tan is professor emeritus of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some of the articles in this series are adapted from the author’s 2006 book, "Medical Malpractice: Understanding the Law, Managing the Risk", and his 2012 Halsbury treatise, "Medical Negligence and Professional Misconduct." For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

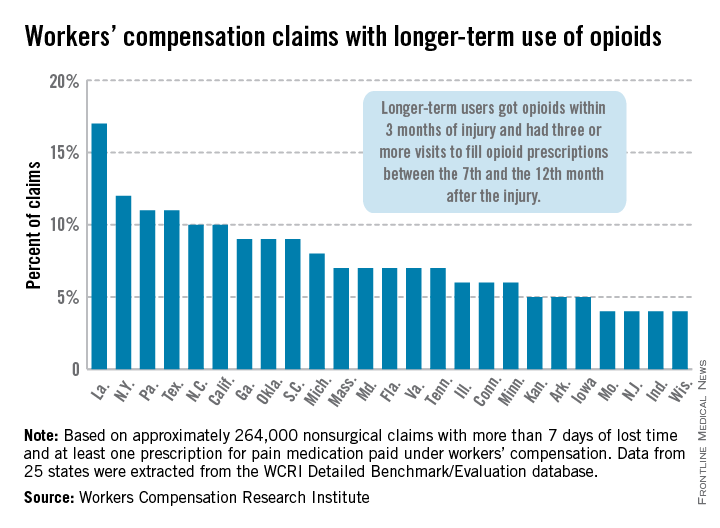

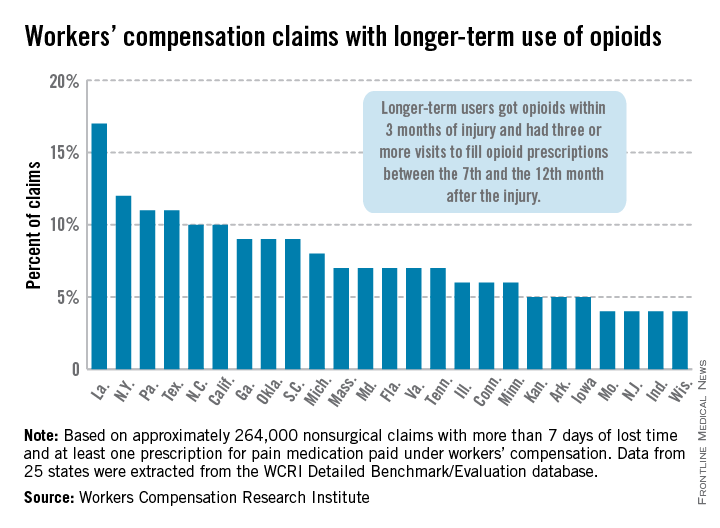

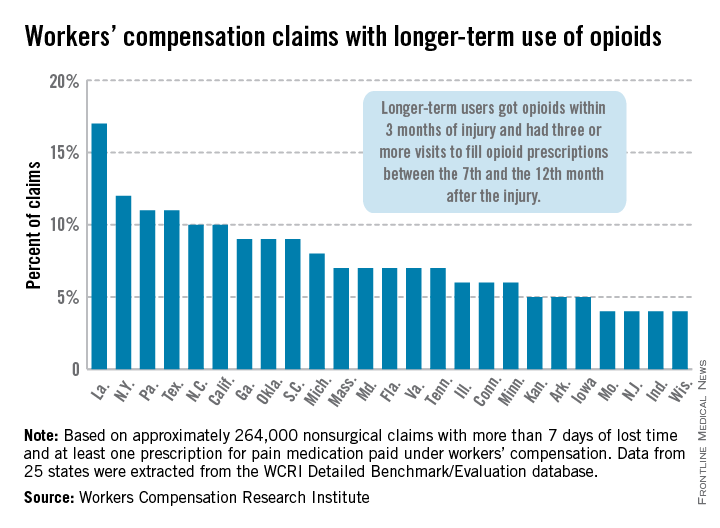

Longer-term opioid use in workers’ comp cases highest in Louisiana

In Louisiana, opioid use lasted more than 6 months in 17% of nonsurgical workers’ compensation claims involving employees who received at least one prescription for pain medication, the Workers Compensation Research Institute reported.

In cases with more than 7 days of lost time, that was the highest rate seen among the 25 states in the study, with New York second at 12% and Pennsylvania and Texas tied for third at 11%. There were four states tied for the lowest rate, at 4%: Missouri, New Jersey, Indiana, and Wisconsin, according to the WCRI report.

Overall, use of narcotics for pain relief by injured workers in such cases ranged from 60% in New Jersey to 88% in Arkansas (median, 76%), while use of any pain medication ranged from 85% in Minnesota to 95% in Florida, Georgia, Tennessee, and Texas (median, 94%), the report showed.

The study involved claims with injuries that occurred from Oct. 1, 2009, through Sept. 30, 2010, with prescriptions filled through March 31, 2012. Longer-term users received a prescription for opioids within 3 months of their injury and had three or more visits to fill opioid prescriptions between the 7th and the 12th month after the injury.

The 25 states in the study "represent more than 70% of the workers’ compensation benefits paid in the United States," the WCRI noted.

The study was based on approximately 264,000 nonsurgical claims and more than 1.5 million prescriptions for pain medications. Data were extracted from the WCRI Detailed Benchmark/Evaluation database and consisted of detailed prescription transactions "collected from workers’ compensation payers and their medical bill review and pharmacy benefit management vendors," the report noted.

In Louisiana, opioid use lasted more than 6 months in 17% of nonsurgical workers’ compensation claims involving employees who received at least one prescription for pain medication, the Workers Compensation Research Institute reported.

In cases with more than 7 days of lost time, that was the highest rate seen among the 25 states in the study, with New York second at 12% and Pennsylvania and Texas tied for third at 11%. There were four states tied for the lowest rate, at 4%: Missouri, New Jersey, Indiana, and Wisconsin, according to the WCRI report.

Overall, use of narcotics for pain relief by injured workers in such cases ranged from 60% in New Jersey to 88% in Arkansas (median, 76%), while use of any pain medication ranged from 85% in Minnesota to 95% in Florida, Georgia, Tennessee, and Texas (median, 94%), the report showed.

The study involved claims with injuries that occurred from Oct. 1, 2009, through Sept. 30, 2010, with prescriptions filled through March 31, 2012. Longer-term users received a prescription for opioids within 3 months of their injury and had three or more visits to fill opioid prescriptions between the 7th and the 12th month after the injury.

The 25 states in the study "represent more than 70% of the workers’ compensation benefits paid in the United States," the WCRI noted.

The study was based on approximately 264,000 nonsurgical claims and more than 1.5 million prescriptions for pain medications. Data were extracted from the WCRI Detailed Benchmark/Evaluation database and consisted of detailed prescription transactions "collected from workers’ compensation payers and their medical bill review and pharmacy benefit management vendors," the report noted.

In Louisiana, opioid use lasted more than 6 months in 17% of nonsurgical workers’ compensation claims involving employees who received at least one prescription for pain medication, the Workers Compensation Research Institute reported.

In cases with more than 7 days of lost time, that was the highest rate seen among the 25 states in the study, with New York second at 12% and Pennsylvania and Texas tied for third at 11%. There were four states tied for the lowest rate, at 4%: Missouri, New Jersey, Indiana, and Wisconsin, according to the WCRI report.

Overall, use of narcotics for pain relief by injured workers in such cases ranged from 60% in New Jersey to 88% in Arkansas (median, 76%), while use of any pain medication ranged from 85% in Minnesota to 95% in Florida, Georgia, Tennessee, and Texas (median, 94%), the report showed.

The study involved claims with injuries that occurred from Oct. 1, 2009, through Sept. 30, 2010, with prescriptions filled through March 31, 2012. Longer-term users received a prescription for opioids within 3 months of their injury and had three or more visits to fill opioid prescriptions between the 7th and the 12th month after the injury.

The 25 states in the study "represent more than 70% of the workers’ compensation benefits paid in the United States," the WCRI noted.

The study was based on approximately 264,000 nonsurgical claims and more than 1.5 million prescriptions for pain medications. Data were extracted from the WCRI Detailed Benchmark/Evaluation database and consisted of detailed prescription transactions "collected from workers’ compensation payers and their medical bill review and pharmacy benefit management vendors," the report noted.

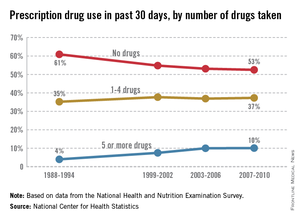

10% of Americans take five or more prescription drugs

In 2007-2010, 10% of Americans reported taking five or more prescription drugs in the past 30 days, up from 4% in 1988-1994, the National Center for Health Statistics said in its "Health, United States, 2013" report released May 14.

By 2007-2010, close to half of all Americans (47%) reported that they had taken at least one prescription drug in the past month, compared with 40% in 1988-1994, according to the NCHS.

Drug use was greater among older age groups, with 40% of those aged 65 years and over and 17% of those aged 45-64 years taking five or more drugs in the past 30 days, compared with 3% of those aged 18-44 years and 1% of those under age 18, the report said.

The analysis of prescription drug use is based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

In 2007-2010, 10% of Americans reported taking five or more prescription drugs in the past 30 days, up from 4% in 1988-1994, the National Center for Health Statistics said in its "Health, United States, 2013" report released May 14.

By 2007-2010, close to half of all Americans (47%) reported that they had taken at least one prescription drug in the past month, compared with 40% in 1988-1994, according to the NCHS.

Drug use was greater among older age groups, with 40% of those aged 65 years and over and 17% of those aged 45-64 years taking five or more drugs in the past 30 days, compared with 3% of those aged 18-44 years and 1% of those under age 18, the report said.

The analysis of prescription drug use is based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

In 2007-2010, 10% of Americans reported taking five or more prescription drugs in the past 30 days, up from 4% in 1988-1994, the National Center for Health Statistics said in its "Health, United States, 2013" report released May 14.

By 2007-2010, close to half of all Americans (47%) reported that they had taken at least one prescription drug in the past month, compared with 40% in 1988-1994, according to the NCHS.

Drug use was greater among older age groups, with 40% of those aged 65 years and over and 17% of those aged 45-64 years taking five or more drugs in the past 30 days, compared with 3% of those aged 18-44 years and 1% of those under age 18, the report said.

The analysis of prescription drug use is based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Perioperative complications of hysterectomy vary by route

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Rates of perioperative complications among women undergoing hysterectomy for benign indications vary according to the route, an ancillary analysis of a retrospective cohort study found.

Analyses were based on 1,440 women who underwent hysterectomy at four teaching hospitals, with procedures about evenly split between the eras before and after introduction of robotic surgery, lead author Dr. Salma Rahimi of Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, reported at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

In the prerobot era, the rate of intraoperative complications – injury of the ureter, bladder, or bowel, or transfusion – was lowest at 3.7% for laparoscopic hysterectomy, about half that for abdominal procedures, and roughly the same as that for vaginal ones. The rate of postoperative complications – infection requiring antibiotics, transfusion, small bowel obstruction, or ileus – was 1.8% with laparoscopic hysterectomy, roughly a third of that seen with the other approaches.

In the postrobot era, the rate of intraoperative complications was 2.8% with vaginal hysterectomy, the lowest value for any approach, including the robotic one. The rate of postoperative complications was 3.0% for robotic hysterectomy, about a quarter of that for abdominal procedures and roughly on a par with that for vaginal and laparoscopic ones.

"Our data demonstrate that a vaginal hysterectomy is associated with fewer intraoperative complications in both the pre- and postrobot period," Dr. Rahimi commented. However, "vaginal hysterectomy was associated with more postoperative infections in the prerobot period."

"The highest complications were noted in the abdominal group, mostly due to transfusions, infections, small bowel obstructions, and ileus," she added.

Introducing the study, she noted that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends vaginal hysterectomy as a first choice over other routes given its relatively better outcomes and lower rates of complications (Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;114:1156-8). "Despite this, most are performed by laparotomy, and there is an increasing trend toward the use of minimally invasive abdominal approaches. Only about 20% are performed by the vaginal approach," she said.

The investigators studied women undergoing hysterectomy identified through the Fellows’ Pelvic Research Network. All of the operations were performed at hospitals with an obstetrics and gynecology residency and had a fellow belonging to the network. Women were excluded if their hysterectomy was performed by a gynecologic oncologist, was for a suspected malignancy, or was done emergently (including cesarean hysterectomies).

Analyses were based on 732 women in the prerobot era (the year before introduction of robotics at each hospital) and 708 in the postrobot era (2011). Characteristics of the women from the two eras were essentially the same, Dr. Rahimi reported at the meeting, jointly sponsored by the American College of Surgeons.

In the prerobot era, the rate of intraoperative complications was 3.9% for vaginal hysterectomy, compared with 7.4% for abdominal hysterectomy (P less than .05) and 3.7% for laparoscopic hysterectomy (P not significant).

The rate of postoperative complications was 8.3% for vaginal hysterectomy, compared with 7.4% for abdominal hysterectomy (P not significant) and 1.8% for laparoscopic hysterectomy (P = .001). These differences were mainly driven by higher rates of infection with the vaginal and abdominal approaches, and a higher rate of small bowel obstruction and ileus with the abdominal approach.

In the postrobot era, the rate of intraoperative complications was 2.8% for vaginal hysterectomy, compared with 10.8% for abdominal hysterectomy (P = .003), 4.6% for laparoscopic hysterectomy (P not significant), and 3.0% for robotic hysterectomy (P not significant). The differences were mainly due to a higher rate of transfusion with the abdominal approach.

The rate of postoperative complications was 5.1% for vaginal hysterectomy, compared with 13.9% for abdominal hysterectomy (P = .008), 3.6% for laparoscopic hysterectomy (P not significant), and 3.0% for robotic hysterectomy (P not significant). The differences again were mainly due to a higher rate of transfusion when surgery was done abdominally.

Dr. Rahimi disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Rates of perioperative complications among women undergoing hysterectomy for benign indications vary according to the route, an ancillary analysis of a retrospective cohort study found.

Analyses were based on 1,440 women who underwent hysterectomy at four teaching hospitals, with procedures about evenly split between the eras before and after introduction of robotic surgery, lead author Dr. Salma Rahimi of Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, reported at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

In the prerobot era, the rate of intraoperative complications – injury of the ureter, bladder, or bowel, or transfusion – was lowest at 3.7% for laparoscopic hysterectomy, about half that for abdominal procedures, and roughly the same as that for vaginal ones. The rate of postoperative complications – infection requiring antibiotics, transfusion, small bowel obstruction, or ileus – was 1.8% with laparoscopic hysterectomy, roughly a third of that seen with the other approaches.

In the postrobot era, the rate of intraoperative complications was 2.8% with vaginal hysterectomy, the lowest value for any approach, including the robotic one. The rate of postoperative complications was 3.0% for robotic hysterectomy, about a quarter of that for abdominal procedures and roughly on a par with that for vaginal and laparoscopic ones.

"Our data demonstrate that a vaginal hysterectomy is associated with fewer intraoperative complications in both the pre- and postrobot period," Dr. Rahimi commented. However, "vaginal hysterectomy was associated with more postoperative infections in the prerobot period."

"The highest complications were noted in the abdominal group, mostly due to transfusions, infections, small bowel obstructions, and ileus," she added.

Introducing the study, she noted that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends vaginal hysterectomy as a first choice over other routes given its relatively better outcomes and lower rates of complications (Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;114:1156-8). "Despite this, most are performed by laparotomy, and there is an increasing trend toward the use of minimally invasive abdominal approaches. Only about 20% are performed by the vaginal approach," she said.

The investigators studied women undergoing hysterectomy identified through the Fellows’ Pelvic Research Network. All of the operations were performed at hospitals with an obstetrics and gynecology residency and had a fellow belonging to the network. Women were excluded if their hysterectomy was performed by a gynecologic oncologist, was for a suspected malignancy, or was done emergently (including cesarean hysterectomies).

Analyses were based on 732 women in the prerobot era (the year before introduction of robotics at each hospital) and 708 in the postrobot era (2011). Characteristics of the women from the two eras were essentially the same, Dr. Rahimi reported at the meeting, jointly sponsored by the American College of Surgeons.

In the prerobot era, the rate of intraoperative complications was 3.9% for vaginal hysterectomy, compared with 7.4% for abdominal hysterectomy (P less than .05) and 3.7% for laparoscopic hysterectomy (P not significant).

The rate of postoperative complications was 8.3% for vaginal hysterectomy, compared with 7.4% for abdominal hysterectomy (P not significant) and 1.8% for laparoscopic hysterectomy (P = .001). These differences were mainly driven by higher rates of infection with the vaginal and abdominal approaches, and a higher rate of small bowel obstruction and ileus with the abdominal approach.

In the postrobot era, the rate of intraoperative complications was 2.8% for vaginal hysterectomy, compared with 10.8% for abdominal hysterectomy (P = .003), 4.6% for laparoscopic hysterectomy (P not significant), and 3.0% for robotic hysterectomy (P not significant). The differences were mainly due to a higher rate of transfusion with the abdominal approach.

The rate of postoperative complications was 5.1% for vaginal hysterectomy, compared with 13.9% for abdominal hysterectomy (P = .008), 3.6% for laparoscopic hysterectomy (P not significant), and 3.0% for robotic hysterectomy (P not significant). The differences again were mainly due to a higher rate of transfusion when surgery was done abdominally.

Dr. Rahimi disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Rates of perioperative complications among women undergoing hysterectomy for benign indications vary according to the route, an ancillary analysis of a retrospective cohort study found.

Analyses were based on 1,440 women who underwent hysterectomy at four teaching hospitals, with procedures about evenly split between the eras before and after introduction of robotic surgery, lead author Dr. Salma Rahimi of Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, reported at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

In the prerobot era, the rate of intraoperative complications – injury of the ureter, bladder, or bowel, or transfusion – was lowest at 3.7% for laparoscopic hysterectomy, about half that for abdominal procedures, and roughly the same as that for vaginal ones. The rate of postoperative complications – infection requiring antibiotics, transfusion, small bowel obstruction, or ileus – was 1.8% with laparoscopic hysterectomy, roughly a third of that seen with the other approaches.

In the postrobot era, the rate of intraoperative complications was 2.8% with vaginal hysterectomy, the lowest value for any approach, including the robotic one. The rate of postoperative complications was 3.0% for robotic hysterectomy, about a quarter of that for abdominal procedures and roughly on a par with that for vaginal and laparoscopic ones.

"Our data demonstrate that a vaginal hysterectomy is associated with fewer intraoperative complications in both the pre- and postrobot period," Dr. Rahimi commented. However, "vaginal hysterectomy was associated with more postoperative infections in the prerobot period."

"The highest complications were noted in the abdominal group, mostly due to transfusions, infections, small bowel obstructions, and ileus," she added.

Introducing the study, she noted that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends vaginal hysterectomy as a first choice over other routes given its relatively better outcomes and lower rates of complications (Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;114:1156-8). "Despite this, most are performed by laparotomy, and there is an increasing trend toward the use of minimally invasive abdominal approaches. Only about 20% are performed by the vaginal approach," she said.

The investigators studied women undergoing hysterectomy identified through the Fellows’ Pelvic Research Network. All of the operations were performed at hospitals with an obstetrics and gynecology residency and had a fellow belonging to the network. Women were excluded if their hysterectomy was performed by a gynecologic oncologist, was for a suspected malignancy, or was done emergently (including cesarean hysterectomies).

Analyses were based on 732 women in the prerobot era (the year before introduction of robotics at each hospital) and 708 in the postrobot era (2011). Characteristics of the women from the two eras were essentially the same, Dr. Rahimi reported at the meeting, jointly sponsored by the American College of Surgeons.

In the prerobot era, the rate of intraoperative complications was 3.9% for vaginal hysterectomy, compared with 7.4% for abdominal hysterectomy (P less than .05) and 3.7% for laparoscopic hysterectomy (P not significant).

The rate of postoperative complications was 8.3% for vaginal hysterectomy, compared with 7.4% for abdominal hysterectomy (P not significant) and 1.8% for laparoscopic hysterectomy (P = .001). These differences were mainly driven by higher rates of infection with the vaginal and abdominal approaches, and a higher rate of small bowel obstruction and ileus with the abdominal approach.

In the postrobot era, the rate of intraoperative complications was 2.8% for vaginal hysterectomy, compared with 10.8% for abdominal hysterectomy (P = .003), 4.6% for laparoscopic hysterectomy (P not significant), and 3.0% for robotic hysterectomy (P not significant). The differences were mainly due to a higher rate of transfusion with the abdominal approach.

The rate of postoperative complications was 5.1% for vaginal hysterectomy, compared with 13.9% for abdominal hysterectomy (P = .008), 3.6% for laparoscopic hysterectomy (P not significant), and 3.0% for robotic hysterectomy (P not significant). The differences again were mainly due to a higher rate of transfusion when surgery was done abdominally.

Dr. Rahimi disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

AT SGS 2014

Key clinical point: Intraoperative complications tend to be low with vaginal, laparoscopic, and robotic hysterectomies.

Major finding: In the postrobot era, the rate of intraoperative complications was 2.8% for vaginal procedures, 10.8% for abdominal ones, 4.6% for laparoscopic ones, and 3.0% for robotic ones.

Data source: An ancillary analysis of a retrospective cohort study of 1,440 cases of hysterectomy done for benign indications

Disclosures: Dr. Rahimi disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

Expert: Choose your sinus surgeon carefully

KEYSTONE, COLO. – Surgical treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis has come a long way from the earlier "grab and tear" days, but referring physicians need to understand that not all otolaryngologists are providing state-of-the-art care.

"I am critical of some of my colleagues," Dr. Todd T. Kingdom said at a meeting on allergy and respiratory diseases sponsored by National Jewish Health.

"If I leave you with one message, it’s to set high expectations of your consultants in otolaryngology. You should find colleagues who are interested in sinus disease, who are committed to it, and who are excellent," added Dr. Kingdom, professor and vice chairman of the department of otolaryngology, head and neck surgery, at the University of Colorado, Denver, and immediate past president of the American Rhinologic Society.

One fine source is the pool of graduates of U.S. subspecialty surgical rhinology fellowship programs. Each year, 30 surgeons complete one of these fellowships, he said.

Technical innovations over the past 15 years have driven major advances in endoscopic sinus surgery. Powered microdebriders are used to precisely and efficiently remove hyperplastic mucosal disease and restore mucociliary clearance. Mucosal preservation is now a central tenet. Forward-thinking surgeons place a priority on creating exposure for delivery of topical medications. The procedures are routinely done on an outpatient basis, and they are less invasive than in former times. The outcomes are better, too, with this modern patient-centered, symptom-based approach.

"We have efficient ways now to take care of very severe disease atraumatically," Dr. Kingdom explained.

He emphasized that postoperative care is critical to successful sinus surgery outcomes. "My biggest criticism of my colleagues in otolaryngology is that many of them cut and go. There isn’t an emphasis on postoperative care," he said. "That’s a clear, clear deficiency in our approach.

"My postop schedule is to see patients at 1, 3, and 6 weeks and 3 and 6 months after surgery – and that’s if they’re doing perfectly. My point is you should have your otolaryngologist really fussing over these people. It’s not, ‘Well, it’s been a couple of weeks, you look fine, you can go back to your allergist now, I’ll see you later.’ It shouldn’t be that way," Dr. Kingdom said.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Dr. Todd T. Kingdom, allergy and respiratory diseases, National Jewish Health, sinus disease, American Rhinologic Society, U.S. subspecialty surgical rhinology fellowship programs, endoscopic sinus surgery, Powered microdebriders, hyperplastic mucosal disease, restore mucociliary clearance, Mucosal preservation,

KEYSTONE, COLO. – Surgical treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis has come a long way from the earlier "grab and tear" days, but referring physicians need to understand that not all otolaryngologists are providing state-of-the-art care.

"I am critical of some of my colleagues," Dr. Todd T. Kingdom said at a meeting on allergy and respiratory diseases sponsored by National Jewish Health.

"If I leave you with one message, it’s to set high expectations of your consultants in otolaryngology. You should find colleagues who are interested in sinus disease, who are committed to it, and who are excellent," added Dr. Kingdom, professor and vice chairman of the department of otolaryngology, head and neck surgery, at the University of Colorado, Denver, and immediate past president of the American Rhinologic Society.

One fine source is the pool of graduates of U.S. subspecialty surgical rhinology fellowship programs. Each year, 30 surgeons complete one of these fellowships, he said.

Technical innovations over the past 15 years have driven major advances in endoscopic sinus surgery. Powered microdebriders are used to precisely and efficiently remove hyperplastic mucosal disease and restore mucociliary clearance. Mucosal preservation is now a central tenet. Forward-thinking surgeons place a priority on creating exposure for delivery of topical medications. The procedures are routinely done on an outpatient basis, and they are less invasive than in former times. The outcomes are better, too, with this modern patient-centered, symptom-based approach.

"We have efficient ways now to take care of very severe disease atraumatically," Dr. Kingdom explained.

He emphasized that postoperative care is critical to successful sinus surgery outcomes. "My biggest criticism of my colleagues in otolaryngology is that many of them cut and go. There isn’t an emphasis on postoperative care," he said. "That’s a clear, clear deficiency in our approach.

"My postop schedule is to see patients at 1, 3, and 6 weeks and 3 and 6 months after surgery – and that’s if they’re doing perfectly. My point is you should have your otolaryngologist really fussing over these people. It’s not, ‘Well, it’s been a couple of weeks, you look fine, you can go back to your allergist now, I’ll see you later.’ It shouldn’t be that way," Dr. Kingdom said.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

KEYSTONE, COLO. – Surgical treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis has come a long way from the earlier "grab and tear" days, but referring physicians need to understand that not all otolaryngologists are providing state-of-the-art care.

"I am critical of some of my colleagues," Dr. Todd T. Kingdom said at a meeting on allergy and respiratory diseases sponsored by National Jewish Health.

"If I leave you with one message, it’s to set high expectations of your consultants in otolaryngology. You should find colleagues who are interested in sinus disease, who are committed to it, and who are excellent," added Dr. Kingdom, professor and vice chairman of the department of otolaryngology, head and neck surgery, at the University of Colorado, Denver, and immediate past president of the American Rhinologic Society.

One fine source is the pool of graduates of U.S. subspecialty surgical rhinology fellowship programs. Each year, 30 surgeons complete one of these fellowships, he said.

Technical innovations over the past 15 years have driven major advances in endoscopic sinus surgery. Powered microdebriders are used to precisely and efficiently remove hyperplastic mucosal disease and restore mucociliary clearance. Mucosal preservation is now a central tenet. Forward-thinking surgeons place a priority on creating exposure for delivery of topical medications. The procedures are routinely done on an outpatient basis, and they are less invasive than in former times. The outcomes are better, too, with this modern patient-centered, symptom-based approach.

"We have efficient ways now to take care of very severe disease atraumatically," Dr. Kingdom explained.

He emphasized that postoperative care is critical to successful sinus surgery outcomes. "My biggest criticism of my colleagues in otolaryngology is that many of them cut and go. There isn’t an emphasis on postoperative care," he said. "That’s a clear, clear deficiency in our approach.

"My postop schedule is to see patients at 1, 3, and 6 weeks and 3 and 6 months after surgery – and that’s if they’re doing perfectly. My point is you should have your otolaryngologist really fussing over these people. It’s not, ‘Well, it’s been a couple of weeks, you look fine, you can go back to your allergist now, I’ll see you later.’ It shouldn’t be that way," Dr. Kingdom said.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Dr. Todd T. Kingdom, allergy and respiratory diseases, National Jewish Health, sinus disease, American Rhinologic Society, U.S. subspecialty surgical rhinology fellowship programs, endoscopic sinus surgery, Powered microdebriders, hyperplastic mucosal disease, restore mucociliary clearance, Mucosal preservation,

Dr. Todd T. Kingdom, allergy and respiratory diseases, National Jewish Health, sinus disease, American Rhinologic Society, U.S. subspecialty surgical rhinology fellowship programs, endoscopic sinus surgery, Powered microdebriders, hyperplastic mucosal disease, restore mucociliary clearance, Mucosal preservation,

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE PULMONARY AND ALLERGY UPDATE

Misery, thy name is chronic rhinosinusitis

KEYSTONE, COLO. – Just how lousy do patients with medically refractory chronic rhinosinusitis feel in daily life? A lot worse than you might guess.