User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

Adding cisplatin to docetaxel monotherapy provides no benefit for elderly with NSCLC

There is no advantage to weekly docetaxel plus cisplatin over docetaxel monotherapy as first-line chemotherapy for elderly patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer, according to phase III study results published online Jan. 12 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

For the study, 276 chemotherapy-naive patients aged 70 years or older with stage III, stage IV, or recurrent non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who were considered unsuitable for bolus cisplatin administration were randomly assigned to receive docetaxel 60 mg/m2 on day 1, every 3 weeks, or docetaxel 20 mg/m2 plus cisplatin 25 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 every 4 weeks.

At the interim analysis, overall survival was inferior among patients who received docetaxel plus cisplatin, compared with those who received docetaxel only (hazard ratio, 1.56; 95% confidence interval, 0.98 to 2.49), Dr. Tetsuya Abe of Niigata (Japan) Cancer Center Hospital and his associates reported (J. Clin. Onc. 2015 Jan. 12. [doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.55.8627]).

The investigators terminated the study early after finding the predictive probability that the treatment arm would be statistically superior to the monotherapy arm on final analysis was less than 1%. The median survival time as 14.8 months for the monotherapy arm and 13.3 months for the docetaxel plus cisplatin arm (HR, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.83 to 1.69).

Toxicity varied between arms. The rates of neutropenia were higher with docetaxel alone, while rates of grade 3 or greater anemia, anorexia, and hyponatremia were higher in the combination arm, they said.

Docetaxel every 3 weeks remains the standard treatment for elderly patients with advanced NSCLC, Dr. Abe and associates concluded.

Dr. Abe reported having no financial disclosures. Other authors reported honoraria from sanofi-aventis and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

On Twitter @nikolaideslaura

What lesson can we learn from this study, and how should the results influence current management of elderly patients with lung cancer?

It is important to accurately interpret the finding of this study, which is that the combination of cisplatin/docetaxel administered on a weekly schedule is not superior to single-agent docetaxel given every 3 weeks in patients older than 70 years of age with lung cancer. The study does not negate the well-founded recognition that patient age does not preclude clinical benefit of systemic anticancer therapy and that elderly patients with lung cancer should be offered systemic therapy if they are fit enough to tolerate the treatment.

Although the study was designed to evaluate treatment efficacy in elderly patients, only patients who were unsuitable for bolus cisplatin infusion were included. As there is no clear definition for patients unsuitable for bolus cisplatin, we believe that this might have led to the enrollment of a patient subset with unfavorable prognosis. The interpretation, external validity, and generalizability of the result of this study are greatly limited because the unwieldy definition of patients considered unsuitable for cisplatin makes it difficult to establish how well the study population represents the elderly patient population with lung cancer.

There is increasing agreement that treatment decisions for elderly patients should be based on performance status, comorbid conditions, and patient preferences. Treatment decisions based entirely on chronological age and not informed by the tremendous knowledge gained in optimal assessment of older patients in recent years do not serve our patients well. Finally, it is imperative to include functional assessment as an integral component of clinical trials designed for older patients.

Dr. Taofeek K. Owonikoko and Dr. Suresh S. Ramalingam are with Emory University and Winship Cancer Institute, Atlanta. These remarks were extracted from the accompanying editorial (J. Clin. Onc. 2015 Jan. 12 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.59.5033]).

What lesson can we learn from this study, and how should the results influence current management of elderly patients with lung cancer?

It is important to accurately interpret the finding of this study, which is that the combination of cisplatin/docetaxel administered on a weekly schedule is not superior to single-agent docetaxel given every 3 weeks in patients older than 70 years of age with lung cancer. The study does not negate the well-founded recognition that patient age does not preclude clinical benefit of systemic anticancer therapy and that elderly patients with lung cancer should be offered systemic therapy if they are fit enough to tolerate the treatment.

Although the study was designed to evaluate treatment efficacy in elderly patients, only patients who were unsuitable for bolus cisplatin infusion were included. As there is no clear definition for patients unsuitable for bolus cisplatin, we believe that this might have led to the enrollment of a patient subset with unfavorable prognosis. The interpretation, external validity, and generalizability of the result of this study are greatly limited because the unwieldy definition of patients considered unsuitable for cisplatin makes it difficult to establish how well the study population represents the elderly patient population with lung cancer.

There is increasing agreement that treatment decisions for elderly patients should be based on performance status, comorbid conditions, and patient preferences. Treatment decisions based entirely on chronological age and not informed by the tremendous knowledge gained in optimal assessment of older patients in recent years do not serve our patients well. Finally, it is imperative to include functional assessment as an integral component of clinical trials designed for older patients.

Dr. Taofeek K. Owonikoko and Dr. Suresh S. Ramalingam are with Emory University and Winship Cancer Institute, Atlanta. These remarks were extracted from the accompanying editorial (J. Clin. Onc. 2015 Jan. 12 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.59.5033]).

What lesson can we learn from this study, and how should the results influence current management of elderly patients with lung cancer?

It is important to accurately interpret the finding of this study, which is that the combination of cisplatin/docetaxel administered on a weekly schedule is not superior to single-agent docetaxel given every 3 weeks in patients older than 70 years of age with lung cancer. The study does not negate the well-founded recognition that patient age does not preclude clinical benefit of systemic anticancer therapy and that elderly patients with lung cancer should be offered systemic therapy if they are fit enough to tolerate the treatment.

Although the study was designed to evaluate treatment efficacy in elderly patients, only patients who were unsuitable for bolus cisplatin infusion were included. As there is no clear definition for patients unsuitable for bolus cisplatin, we believe that this might have led to the enrollment of a patient subset with unfavorable prognosis. The interpretation, external validity, and generalizability of the result of this study are greatly limited because the unwieldy definition of patients considered unsuitable for cisplatin makes it difficult to establish how well the study population represents the elderly patient population with lung cancer.

There is increasing agreement that treatment decisions for elderly patients should be based on performance status, comorbid conditions, and patient preferences. Treatment decisions based entirely on chronological age and not informed by the tremendous knowledge gained in optimal assessment of older patients in recent years do not serve our patients well. Finally, it is imperative to include functional assessment as an integral component of clinical trials designed for older patients.

Dr. Taofeek K. Owonikoko and Dr. Suresh S. Ramalingam are with Emory University and Winship Cancer Institute, Atlanta. These remarks were extracted from the accompanying editorial (J. Clin. Onc. 2015 Jan. 12 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.59.5033]).

There is no advantage to weekly docetaxel plus cisplatin over docetaxel monotherapy as first-line chemotherapy for elderly patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer, according to phase III study results published online Jan. 12 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

For the study, 276 chemotherapy-naive patients aged 70 years or older with stage III, stage IV, or recurrent non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who were considered unsuitable for bolus cisplatin administration were randomly assigned to receive docetaxel 60 mg/m2 on day 1, every 3 weeks, or docetaxel 20 mg/m2 plus cisplatin 25 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 every 4 weeks.

At the interim analysis, overall survival was inferior among patients who received docetaxel plus cisplatin, compared with those who received docetaxel only (hazard ratio, 1.56; 95% confidence interval, 0.98 to 2.49), Dr. Tetsuya Abe of Niigata (Japan) Cancer Center Hospital and his associates reported (J. Clin. Onc. 2015 Jan. 12. [doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.55.8627]).

The investigators terminated the study early after finding the predictive probability that the treatment arm would be statistically superior to the monotherapy arm on final analysis was less than 1%. The median survival time as 14.8 months for the monotherapy arm and 13.3 months for the docetaxel plus cisplatin arm (HR, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.83 to 1.69).

Toxicity varied between arms. The rates of neutropenia were higher with docetaxel alone, while rates of grade 3 or greater anemia, anorexia, and hyponatremia were higher in the combination arm, they said.

Docetaxel every 3 weeks remains the standard treatment for elderly patients with advanced NSCLC, Dr. Abe and associates concluded.

Dr. Abe reported having no financial disclosures. Other authors reported honoraria from sanofi-aventis and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

On Twitter @nikolaideslaura

There is no advantage to weekly docetaxel plus cisplatin over docetaxel monotherapy as first-line chemotherapy for elderly patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer, according to phase III study results published online Jan. 12 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

For the study, 276 chemotherapy-naive patients aged 70 years or older with stage III, stage IV, or recurrent non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who were considered unsuitable for bolus cisplatin administration were randomly assigned to receive docetaxel 60 mg/m2 on day 1, every 3 weeks, or docetaxel 20 mg/m2 plus cisplatin 25 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 every 4 weeks.

At the interim analysis, overall survival was inferior among patients who received docetaxel plus cisplatin, compared with those who received docetaxel only (hazard ratio, 1.56; 95% confidence interval, 0.98 to 2.49), Dr. Tetsuya Abe of Niigata (Japan) Cancer Center Hospital and his associates reported (J. Clin. Onc. 2015 Jan. 12. [doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.55.8627]).

The investigators terminated the study early after finding the predictive probability that the treatment arm would be statistically superior to the monotherapy arm on final analysis was less than 1%. The median survival time as 14.8 months for the monotherapy arm and 13.3 months for the docetaxel plus cisplatin arm (HR, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.83 to 1.69).

Toxicity varied between arms. The rates of neutropenia were higher with docetaxel alone, while rates of grade 3 or greater anemia, anorexia, and hyponatremia were higher in the combination arm, they said.

Docetaxel every 3 weeks remains the standard treatment for elderly patients with advanced NSCLC, Dr. Abe and associates concluded.

Dr. Abe reported having no financial disclosures. Other authors reported honoraria from sanofi-aventis and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

On Twitter @nikolaideslaura

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Docetaxel every 3 weeks remains the standard treatment for elderly patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer.

Major finding: Overall survival was inferior among patients who received docetaxel plus cisplatin, compared with those who received docetaxel only (hazard ratio, 1.56; 95% confidence interval, 0.98 to 2.49).

Data source: Randomized phase III Japanese trial of 276 elderly patients with stage III, stage IV, or recurrent non–small cell lung cancer (Intergroup Trial JCOG0803/WJOG4307L).

Disclosures: Dr. Abe reported having no financial disclosures. Other authors reported honoraria from sanofi-aventis and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Unnecessary hysterectomies still significant, Michigan data indicate

Almost one in five hysterectomies for benign indications were unnecessary, based on 2013 data from 52 Michigan hospitals.

Uterine pathology reports did not match or support the indication for surgery in 18% of the 3,397 hysterectomies reviewed from the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative, a state-wide program to improve surgical care. In women under 40 years old, pathology did not support surgery in 38% of hysterectomies for benign indications.

Endometriosis and chronic pain were the most common reasons for unnecessary uterus removal; pathology was unsupportive of surgery in about 40% of those cases. Pathology also was unsupportive in about 14% of women with fibroid or acute uterine bleeding (AUB) and in about 20% of the remaining cases, which were mostly indicated for a blend of bleeding, pain, and other problems (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014 Dec 23 [doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2014.11.031]).

Almost half of the women had no documentation in their charts that alternatives to hysterectomy were tried or even considered. Hormonal management, operative hysteroscopy, endometrial ablation, levonorgestrel intrauterine devices (IUDs), and other approaches were documented in 68% of women under 40 years old, but documentation was less likely in women over 40 years old. Alternatives approaches were more likely in women with larger uteri and in women with endometriosis, but were, overall, “underutilized,” Dr. Daniel Morgan, an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and his fellow researchers concluded.

Parity, body mass index, insurance, and common medical comorbidities did not seem to influence the use of alternatives in the study.

The researchers noted that checklists for preoperative appropriateness have been shown in previous studies to reduce the rate of benign hysterectomies, and increase the likelihood that pathology will support the reason for the operation.

The checklist approach “could help standardize treatment and ensure appropriate uterine-sparing management has been offered. The use of electronic medical records systems could potentially facilitate this type of standardization with relative ease,” the researchers wrote.

Also, the levonorgestrel IUD, “a highly effective, cost-saving intervention for women with acute uterine bleeding and pelvic pain, was considered [in] only 12%” of the Michigan cases. Increasing its use is another “important area for quality improvement and cost savings,” they added.

“We are now in the process of developing institution-specific reports ... on use of alternatives prior to hysterectomy and rates of negative pathology. It is our goal that each institution in the Collaborative will see their data and act on it accordingly. We hope that it will lead to more use (or at least consideration) of alternatives to hysterectomy and lower rates of negative pathology.”

The Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative is funded by Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Michigan/Blue Care Network. Dr. Morgan reported no conflicts of interest.

Almost one in five hysterectomies for benign indications were unnecessary, based on 2013 data from 52 Michigan hospitals.

Uterine pathology reports did not match or support the indication for surgery in 18% of the 3,397 hysterectomies reviewed from the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative, a state-wide program to improve surgical care. In women under 40 years old, pathology did not support surgery in 38% of hysterectomies for benign indications.

Endometriosis and chronic pain were the most common reasons for unnecessary uterus removal; pathology was unsupportive of surgery in about 40% of those cases. Pathology also was unsupportive in about 14% of women with fibroid or acute uterine bleeding (AUB) and in about 20% of the remaining cases, which were mostly indicated for a blend of bleeding, pain, and other problems (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014 Dec 23 [doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2014.11.031]).

Almost half of the women had no documentation in their charts that alternatives to hysterectomy were tried or even considered. Hormonal management, operative hysteroscopy, endometrial ablation, levonorgestrel intrauterine devices (IUDs), and other approaches were documented in 68% of women under 40 years old, but documentation was less likely in women over 40 years old. Alternatives approaches were more likely in women with larger uteri and in women with endometriosis, but were, overall, “underutilized,” Dr. Daniel Morgan, an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and his fellow researchers concluded.

Parity, body mass index, insurance, and common medical comorbidities did not seem to influence the use of alternatives in the study.

The researchers noted that checklists for preoperative appropriateness have been shown in previous studies to reduce the rate of benign hysterectomies, and increase the likelihood that pathology will support the reason for the operation.

The checklist approach “could help standardize treatment and ensure appropriate uterine-sparing management has been offered. The use of electronic medical records systems could potentially facilitate this type of standardization with relative ease,” the researchers wrote.

Also, the levonorgestrel IUD, “a highly effective, cost-saving intervention for women with acute uterine bleeding and pelvic pain, was considered [in] only 12%” of the Michigan cases. Increasing its use is another “important area for quality improvement and cost savings,” they added.

“We are now in the process of developing institution-specific reports ... on use of alternatives prior to hysterectomy and rates of negative pathology. It is our goal that each institution in the Collaborative will see their data and act on it accordingly. We hope that it will lead to more use (or at least consideration) of alternatives to hysterectomy and lower rates of negative pathology.”

The Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative is funded by Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Michigan/Blue Care Network. Dr. Morgan reported no conflicts of interest.

Almost one in five hysterectomies for benign indications were unnecessary, based on 2013 data from 52 Michigan hospitals.

Uterine pathology reports did not match or support the indication for surgery in 18% of the 3,397 hysterectomies reviewed from the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative, a state-wide program to improve surgical care. In women under 40 years old, pathology did not support surgery in 38% of hysterectomies for benign indications.

Endometriosis and chronic pain were the most common reasons for unnecessary uterus removal; pathology was unsupportive of surgery in about 40% of those cases. Pathology also was unsupportive in about 14% of women with fibroid or acute uterine bleeding (AUB) and in about 20% of the remaining cases, which were mostly indicated for a blend of bleeding, pain, and other problems (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014 Dec 23 [doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2014.11.031]).

Almost half of the women had no documentation in their charts that alternatives to hysterectomy were tried or even considered. Hormonal management, operative hysteroscopy, endometrial ablation, levonorgestrel intrauterine devices (IUDs), and other approaches were documented in 68% of women under 40 years old, but documentation was less likely in women over 40 years old. Alternatives approaches were more likely in women with larger uteri and in women with endometriosis, but were, overall, “underutilized,” Dr. Daniel Morgan, an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and his fellow researchers concluded.

Parity, body mass index, insurance, and common medical comorbidities did not seem to influence the use of alternatives in the study.

The researchers noted that checklists for preoperative appropriateness have been shown in previous studies to reduce the rate of benign hysterectomies, and increase the likelihood that pathology will support the reason for the operation.

The checklist approach “could help standardize treatment and ensure appropriate uterine-sparing management has been offered. The use of electronic medical records systems could potentially facilitate this type of standardization with relative ease,” the researchers wrote.

Also, the levonorgestrel IUD, “a highly effective, cost-saving intervention for women with acute uterine bleeding and pelvic pain, was considered [in] only 12%” of the Michigan cases. Increasing its use is another “important area for quality improvement and cost savings,” they added.

“We are now in the process of developing institution-specific reports ... on use of alternatives prior to hysterectomy and rates of negative pathology. It is our goal that each institution in the Collaborative will see their data and act on it accordingly. We hope that it will lead to more use (or at least consideration) of alternatives to hysterectomy and lower rates of negative pathology.”

The Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative is funded by Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Michigan/Blue Care Network. Dr. Morgan reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF OBSTETRICS AND GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point: Take the time to try levonorgestrel IUDs and other alternatives before removing a woman’s uterus.

Major finding: About 40% of hysterectomies for benign indications in women younger than 40 years old were not supported by post-surgical pathology.

Data source: Chart review of 3,397 hysterectomies at 52 Michigan hospitals

Disclosures:The Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative is funded by Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Michigan/Blue Care Network. The lead investigator has no financial conflicts of interest.

Trendelenburg positioning does not increase ventilator injuries

VANCOUVER, B.C. – Trendelenburg position does not materially increase ventilator pressures during laparoscopic gynecologic surgery, according to investigators from McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont.

The use of the Trendelenburg position can sometimes cause tension in the operating room. Surgeons need to roll the small bowel out of the pelvis to get access to their gynecologic targets, but anesthesiologists worry that they’ll have to turn up ventilator pressures – and risk barotrauma – if women are placed in a head-down position. It’s unclear from previous studies if pressures really need to be increased when using a moderate Trendelenburg position, Dr. Stephen Bates, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at McMaster University, said at a meeting sponsored by the AAGL.

To find out, Dr. Bates and his colleagues monitored peak inspiratory pressures (PIP), pneumoperitoneum pressures, degrees of Trendelenburg, and other factors as 100 women underwent laparoscopic hysterectomies performed by a total of seven surgeons. The women were aged 46 years, on average, and had a mean body mass index of 29 kg/m2.

The surgeons opted for an average of 10 degrees Trendelenburg, which resulted in a 1.9 cm H20 (7%) increase in PIP from horizontal positioning, up from a mean of 26.7 to 28.6 cm H20.

“By all anesthesia standards, this is a trivial change and clinically insignificant,” Dr. Bates said in an interview. “The traditional dogma is that if you put patients in Trendelenburg, you’ll increase the difficulty of ventilating them. That was not the case.”

But body mass index, and to a greater degree pneumoperitoneum pressures, did predict increased ventilator pressures among the women.

“The higher pneumoperitoneum pressures are, the harder it is to ventilate,” Dr. Bates said. “There’s [almost] a linear relationship between PnP [pneumoperitoneum pressures] and ventilator pressures.”

When pneumoperitoneum pressures were reduced from 15 to 10 mm Hg, PIP fell by approximately 10%, but the surgeons – all blinded to the reduction in PnP – did not notice any deterioration in their surgical views, he said.

Taken together, the findings suggest a new way to negotiate Trendelenburg positioning in the operating room. “Anesthesiologists and gynecologic surgeons should consider minimizing the pneumoperitoneum pressure rather than reducing the degree of Trendelenburg,” Dr. Bates said.

The researchers also tested an inflatable pillow that lifted women’s buttocks a few inches above the table. The hope was that it would reduce the degree of Trendelenburg needed for their operations, and subsequently reduce PIP. Surgeons were able to decrease Trendelenburg by about 4 degrees with the pillow, but consistent with the study’s overall findings, it made no real difference in PIP. There was a clinically insignificant drop of 0.3 cm H20, from a mean of 28.6 to 28.3 cm H20, Dr. Bates said.

Dr. Bates reported having no financial disclosures.

VANCOUVER, B.C. – Trendelenburg position does not materially increase ventilator pressures during laparoscopic gynecologic surgery, according to investigators from McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont.

The use of the Trendelenburg position can sometimes cause tension in the operating room. Surgeons need to roll the small bowel out of the pelvis to get access to their gynecologic targets, but anesthesiologists worry that they’ll have to turn up ventilator pressures – and risk barotrauma – if women are placed in a head-down position. It’s unclear from previous studies if pressures really need to be increased when using a moderate Trendelenburg position, Dr. Stephen Bates, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at McMaster University, said at a meeting sponsored by the AAGL.

To find out, Dr. Bates and his colleagues monitored peak inspiratory pressures (PIP), pneumoperitoneum pressures, degrees of Trendelenburg, and other factors as 100 women underwent laparoscopic hysterectomies performed by a total of seven surgeons. The women were aged 46 years, on average, and had a mean body mass index of 29 kg/m2.

The surgeons opted for an average of 10 degrees Trendelenburg, which resulted in a 1.9 cm H20 (7%) increase in PIP from horizontal positioning, up from a mean of 26.7 to 28.6 cm H20.

“By all anesthesia standards, this is a trivial change and clinically insignificant,” Dr. Bates said in an interview. “The traditional dogma is that if you put patients in Trendelenburg, you’ll increase the difficulty of ventilating them. That was not the case.”

But body mass index, and to a greater degree pneumoperitoneum pressures, did predict increased ventilator pressures among the women.

“The higher pneumoperitoneum pressures are, the harder it is to ventilate,” Dr. Bates said. “There’s [almost] a linear relationship between PnP [pneumoperitoneum pressures] and ventilator pressures.”

When pneumoperitoneum pressures were reduced from 15 to 10 mm Hg, PIP fell by approximately 10%, but the surgeons – all blinded to the reduction in PnP – did not notice any deterioration in their surgical views, he said.

Taken together, the findings suggest a new way to negotiate Trendelenburg positioning in the operating room. “Anesthesiologists and gynecologic surgeons should consider minimizing the pneumoperitoneum pressure rather than reducing the degree of Trendelenburg,” Dr. Bates said.

The researchers also tested an inflatable pillow that lifted women’s buttocks a few inches above the table. The hope was that it would reduce the degree of Trendelenburg needed for their operations, and subsequently reduce PIP. Surgeons were able to decrease Trendelenburg by about 4 degrees with the pillow, but consistent with the study’s overall findings, it made no real difference in PIP. There was a clinically insignificant drop of 0.3 cm H20, from a mean of 28.6 to 28.3 cm H20, Dr. Bates said.

Dr. Bates reported having no financial disclosures.

VANCOUVER, B.C. – Trendelenburg position does not materially increase ventilator pressures during laparoscopic gynecologic surgery, according to investigators from McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont.

The use of the Trendelenburg position can sometimes cause tension in the operating room. Surgeons need to roll the small bowel out of the pelvis to get access to their gynecologic targets, but anesthesiologists worry that they’ll have to turn up ventilator pressures – and risk barotrauma – if women are placed in a head-down position. It’s unclear from previous studies if pressures really need to be increased when using a moderate Trendelenburg position, Dr. Stephen Bates, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at McMaster University, said at a meeting sponsored by the AAGL.

To find out, Dr. Bates and his colleagues monitored peak inspiratory pressures (PIP), pneumoperitoneum pressures, degrees of Trendelenburg, and other factors as 100 women underwent laparoscopic hysterectomies performed by a total of seven surgeons. The women were aged 46 years, on average, and had a mean body mass index of 29 kg/m2.

The surgeons opted for an average of 10 degrees Trendelenburg, which resulted in a 1.9 cm H20 (7%) increase in PIP from horizontal positioning, up from a mean of 26.7 to 28.6 cm H20.

“By all anesthesia standards, this is a trivial change and clinically insignificant,” Dr. Bates said in an interview. “The traditional dogma is that if you put patients in Trendelenburg, you’ll increase the difficulty of ventilating them. That was not the case.”

But body mass index, and to a greater degree pneumoperitoneum pressures, did predict increased ventilator pressures among the women.

“The higher pneumoperitoneum pressures are, the harder it is to ventilate,” Dr. Bates said. “There’s [almost] a linear relationship between PnP [pneumoperitoneum pressures] and ventilator pressures.”

When pneumoperitoneum pressures were reduced from 15 to 10 mm Hg, PIP fell by approximately 10%, but the surgeons – all blinded to the reduction in PnP – did not notice any deterioration in their surgical views, he said.

Taken together, the findings suggest a new way to negotiate Trendelenburg positioning in the operating room. “Anesthesiologists and gynecologic surgeons should consider minimizing the pneumoperitoneum pressure rather than reducing the degree of Trendelenburg,” Dr. Bates said.

The researchers also tested an inflatable pillow that lifted women’s buttocks a few inches above the table. The hope was that it would reduce the degree of Trendelenburg needed for their operations, and subsequently reduce PIP. Surgeons were able to decrease Trendelenburg by about 4 degrees with the pillow, but consistent with the study’s overall findings, it made no real difference in PIP. There was a clinically insignificant drop of 0.3 cm H20, from a mean of 28.6 to 28.3 cm H20, Dr. Bates said.

Dr. Bates reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE AAGL GLOBAL CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Gynecologic surgeons and anesthesiologists should negotiate to reduce pneumoperitoneum pressure instead of the degree of Trendelenburg.

Major finding: Use of a moderate Trendelenburg position increases peak inspiratory pressures (PIP) by 1.9 cm H20, but a 5 mm Hg drop in pneumoperitoneum pressures reduced PIP by about 10%.

Data source: Researchers monitored 100 women during laparoscopic hysterectomies.

Disclosures: There was no outside funding for the project, and the lead investigator reported having no financial disclosures.

Skin injury after FEVAR less prevalent than expected

CORONADO, CALIF. – Skin injury following fenestrated endovascular aortic stent grafting is less prevalent than expected, results from a single-center retrospective study showed.

“Radiation-induced skin injury is a serious potential complication of fluoroscopically guided interventions,” Dr. Melissa L. Kirkwood said at the annual meeting of the Western Vascular Society. “These injuries are associated with a threshold radiation dose, above which the severity of injury increases with increasing dose. Instances of these injuries are mostly limited to case reports of coronary interventions, TIPS procedures, and neuroembolizations.”

These radiation-induced skin lesions can be classified as prompt, early, mid-term, or late depending on when they present following the fluoroscopically guided intervention. “The National Cancer Institute has defined four grades of skin injury, with the most frequent being transient erythema, a prompt reaction within the first 24 hours occurring at skin doses as low as 2 Gy,” said Dr. Kirkwood of the division of vascular and endovascular surgery at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas. “With increasing skin doses, more severe effects present themselves. Atrophy, ulceration, and necrosis are possibilities.”

She went on to note that fenestrated endovascular aneurysm repairs often require high doses of radiation, yet the prevalence of deterministic skin injury following these cases is unknown. In a recent study, Dr. Kirkwood and her associates retrospectively reviewed 61 complex fluoroscopically guided interventions that met substantial radiation dose level criteria (SRDL), which is defined by the National Council on Radiation and Protection Measurements as a reference air kerma (RAK) greater than or equal to 5 Gy (J. Vasc. Surg. 2014; 60[3]:742-8). “Despite mean peak skin doses as high as 6.5 Gy, ranging up to 18.5 Gy, we did not detect any skin injuries in this cohort,” Dr. Kirkwood said. “That study, however, was limited by its retrospective design. There was no postoperative protocol in place to ensure that a thorough skin exam was performed on each patient at every follow-up visit. Therefore, we hypothesized that a more thorough postoperative follow-up of patients would detect some skin injury following these cases.”

For the current study, she and her associates sought to examine the prevalence of deterministic effects after FEVAR as well as well as any patient characteristics that may predispose patients to skin injury.

In June 2013, the researchers implemented a new policy regarding the follow-up of FEVAR patients, which involved a full skin exam at postoperative week 2 and 4, and at 3 and 6 months, as well as questioning patients about any skin-related complaints. For the current study, they retrospectively reviewed all FEVARs over a 7-month period after the change in policy and highlighted all the cases that reached a RAK of 5 Gy or greater. The RAK was the dose metric used in this study. It is a measure of the radiation dose to air at the interventional reference point, which, on standard fluoroscopes, is 15 cm along the beam axis toward the focal spot from isocenter. Dr. Kirkwood characterized RAK as “the best real-time indicator of patient dose, because it roughly estimates the dose at the entry point on the patient’s skin.” Peak skin dose, a dose index, and simulated skin dose maps were calculated using customized software employing input data from fluoroscopic machine logs.

Of 317 cases performed, 22 met or exceeded a RAK of 5 Gy. Of these, 21 were FEVARs and one was an embolization. Most patients (91%) were male and their mean body mass index was 30 kg/m2. Comorbidities and risk factors for skin injury included smoking, diabetes, and the concomitant applications of chemotherapeutic agents.

Dr. Kirkwood reported that the average RAK for all FEVARs was 8 Gy, with a range of 5-11 Gy. Slightly more than half of patients (52%) had multiple fluoroscopically guided interventions within 6 months of their SRDL event. The average RAK for this subset of patients was 10 Gy (range of 5 to 15).

The mean peak skin dose for all FEVARs was 5 Gy (a range of 2 to 10 Gy), and the dose index was 0.69. The average peak skin dose for the subset of patients with multiple procedures was 7 Gy (a range of 3 to 9 Gy).

In terms of the follow-up, all 21 FEVAR patients were examined at the 1- or 2-week mark, 81% were examined at 1 month, 52% were examined at 3 months, and 62% were examined at 6 months. No radiation skin injuries were reported. “Based on the published data, we would expect to see all grades of skin injury, especially in the cohort of the 5-10 Gy,” Dr. Kirkwood said.

In the previous study, conducted prior to the new follow-up policy, the dose index for FEVARs was 0.78, “meaning that the peak skin dose that the patient received could be roughly estimated as 78% of the RAK dose displayed on the monitor,” Dr. Kirkwood explained. “In the current work, the dose index decreased to 60%. This suggests that surgeons in our group have now more appropriately and effectively employed strategies to decrease radiation dose to the patient. However, even when the best operating practice is employed, FEVARs still continue to require high radiation doses in order to complete. “

The present study demonstrated that deterministic skin injuries “are uncommon after FEVAR, even at high RAK levels and regardless of cumulative dose,” she concluded. “Even with more comprehensive patient follow-up, the fact that no skin injuries were reported suggests that skin injuries in this patient cohort are less prevalent than the published guidelines would predict.”

Dr. Kirkwood reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

The dramatic paradigm shift in vascular surgery in the last decade and a half, resulting in the increased and widespread application of catheter-based fluoroscopic interventions makes the topic of radiation injury timely for all of us. This report is a follow up of a study by the same group published in the Journal of Vascular Surgery in 2013 (58:715-21) in which they demonstrated that the use of a variety of radiation safety measures including increasing table height, utilizing collimation and angulation, decreasing magnification modes, and maintaining minimal patient-to-detector distance resulted in a 60% reduction in skin dose to their patients when measured as an index of peak skin dose to reference air kerma (PSD/RAK). Unfortunately, skin exposure remained high for FEVAR despite these measures, underscoring the fact that for very complex interventions, even with excellent radiation safety practices, the risk of skin injury remains a reality.

The fact that skin doses as high as 11 Gy did not result in any deterministic injuries is both reassuring and a little surprising. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, radiation doses of greater than 2 Gy but less than 15 Gy will usually result in erythema within 1-2 days, with a second period of erythema and edema at 2-5 weeks, occasionally resulting in desquamation at 6-7 weeks. Late changes can include mild skin atrophy and some hyperpigmentation. Although complete healing can usually be expected at these doses, squamous skin cancer can still occur, often more than a decade after exposure.

So why were no injuries seen? It may be that some were missed since follow-up examinations were not performed in 100% of their patients at any time interval, and it’s not stated whether exams were routinely performed in the first 1-2 days, when I would presume most patients were still hospitalized and the first stage of skin erythema is usually seen. Alternatively, it may be that the surrogate measure of either RAK or the index of PSD/RAK overestimated the true radiation skin dose, which seems highly likely, especially if the time of exposure in any one location was based less on the frequent changes in gantry angle and table position so commonly used in these procedures.

In our hospital, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health regulations require the patient and their physician be notified by letter when the estimated total absorbed radiation dose equals or exceeds 2 Gy. This is based on calculations by our physicist who reviews the details of any case in which the RAK measured equals or exceeds 2 Gy. Like the experiences of the authors, this most commonly occurs with lengthy and complex interventions. In our experience, we have never observed a significant skin injury presumably for the same reason – the exposure in any one location tends to be far less than the total calculated skin dose. Nevertheless, this study should not lull surgeons into a sense of complacency regarding the risk to the patient (and themselves and their staff). As our comfort and expertise with complex interventions increases, it is likely that radiation exposure will continue to increase, placing our patients at increased risk. Understanding the risk of radiation skin injury and how to minimize it is critical for any surgeon performing FEVAR and any other complex intervention utilizing fluoroscopic imaging.

Dr. Frank Pomposelli is an associate professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School; clinical chief, division of vascular surgery at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center; and section chief, division of vascular surgery, New England Baptist Hospital, Boston. He is also an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

The dramatic paradigm shift in vascular surgery in the last decade and a half, resulting in the increased and widespread application of catheter-based fluoroscopic interventions makes the topic of radiation injury timely for all of us. This report is a follow up of a study by the same group published in the Journal of Vascular Surgery in 2013 (58:715-21) in which they demonstrated that the use of a variety of radiation safety measures including increasing table height, utilizing collimation and angulation, decreasing magnification modes, and maintaining minimal patient-to-detector distance resulted in a 60% reduction in skin dose to their patients when measured as an index of peak skin dose to reference air kerma (PSD/RAK). Unfortunately, skin exposure remained high for FEVAR despite these measures, underscoring the fact that for very complex interventions, even with excellent radiation safety practices, the risk of skin injury remains a reality.

The fact that skin doses as high as 11 Gy did not result in any deterministic injuries is both reassuring and a little surprising. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, radiation doses of greater than 2 Gy but less than 15 Gy will usually result in erythema within 1-2 days, with a second period of erythema and edema at 2-5 weeks, occasionally resulting in desquamation at 6-7 weeks. Late changes can include mild skin atrophy and some hyperpigmentation. Although complete healing can usually be expected at these doses, squamous skin cancer can still occur, often more than a decade after exposure.

So why were no injuries seen? It may be that some were missed since follow-up examinations were not performed in 100% of their patients at any time interval, and it’s not stated whether exams were routinely performed in the first 1-2 days, when I would presume most patients were still hospitalized and the first stage of skin erythema is usually seen. Alternatively, it may be that the surrogate measure of either RAK or the index of PSD/RAK overestimated the true radiation skin dose, which seems highly likely, especially if the time of exposure in any one location was based less on the frequent changes in gantry angle and table position so commonly used in these procedures.

In our hospital, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health regulations require the patient and their physician be notified by letter when the estimated total absorbed radiation dose equals or exceeds 2 Gy. This is based on calculations by our physicist who reviews the details of any case in which the RAK measured equals or exceeds 2 Gy. Like the experiences of the authors, this most commonly occurs with lengthy and complex interventions. In our experience, we have never observed a significant skin injury presumably for the same reason – the exposure in any one location tends to be far less than the total calculated skin dose. Nevertheless, this study should not lull surgeons into a sense of complacency regarding the risk to the patient (and themselves and their staff). As our comfort and expertise with complex interventions increases, it is likely that radiation exposure will continue to increase, placing our patients at increased risk. Understanding the risk of radiation skin injury and how to minimize it is critical for any surgeon performing FEVAR and any other complex intervention utilizing fluoroscopic imaging.

Dr. Frank Pomposelli is an associate professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School; clinical chief, division of vascular surgery at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center; and section chief, division of vascular surgery, New England Baptist Hospital, Boston. He is also an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

The dramatic paradigm shift in vascular surgery in the last decade and a half, resulting in the increased and widespread application of catheter-based fluoroscopic interventions makes the topic of radiation injury timely for all of us. This report is a follow up of a study by the same group published in the Journal of Vascular Surgery in 2013 (58:715-21) in which they demonstrated that the use of a variety of radiation safety measures including increasing table height, utilizing collimation and angulation, decreasing magnification modes, and maintaining minimal patient-to-detector distance resulted in a 60% reduction in skin dose to their patients when measured as an index of peak skin dose to reference air kerma (PSD/RAK). Unfortunately, skin exposure remained high for FEVAR despite these measures, underscoring the fact that for very complex interventions, even with excellent radiation safety practices, the risk of skin injury remains a reality.

The fact that skin doses as high as 11 Gy did not result in any deterministic injuries is both reassuring and a little surprising. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, radiation doses of greater than 2 Gy but less than 15 Gy will usually result in erythema within 1-2 days, with a second period of erythema and edema at 2-5 weeks, occasionally resulting in desquamation at 6-7 weeks. Late changes can include mild skin atrophy and some hyperpigmentation. Although complete healing can usually be expected at these doses, squamous skin cancer can still occur, often more than a decade after exposure.

So why were no injuries seen? It may be that some were missed since follow-up examinations were not performed in 100% of their patients at any time interval, and it’s not stated whether exams were routinely performed in the first 1-2 days, when I would presume most patients were still hospitalized and the first stage of skin erythema is usually seen. Alternatively, it may be that the surrogate measure of either RAK or the index of PSD/RAK overestimated the true radiation skin dose, which seems highly likely, especially if the time of exposure in any one location was based less on the frequent changes in gantry angle and table position so commonly used in these procedures.

In our hospital, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health regulations require the patient and their physician be notified by letter when the estimated total absorbed radiation dose equals or exceeds 2 Gy. This is based on calculations by our physicist who reviews the details of any case in which the RAK measured equals or exceeds 2 Gy. Like the experiences of the authors, this most commonly occurs with lengthy and complex interventions. In our experience, we have never observed a significant skin injury presumably for the same reason – the exposure in any one location tends to be far less than the total calculated skin dose. Nevertheless, this study should not lull surgeons into a sense of complacency regarding the risk to the patient (and themselves and their staff). As our comfort and expertise with complex interventions increases, it is likely that radiation exposure will continue to increase, placing our patients at increased risk. Understanding the risk of radiation skin injury and how to minimize it is critical for any surgeon performing FEVAR and any other complex intervention utilizing fluoroscopic imaging.

Dr. Frank Pomposelli is an associate professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School; clinical chief, division of vascular surgery at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center; and section chief, division of vascular surgery, New England Baptist Hospital, Boston. He is also an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

CORONADO, CALIF. – Skin injury following fenestrated endovascular aortic stent grafting is less prevalent than expected, results from a single-center retrospective study showed.

“Radiation-induced skin injury is a serious potential complication of fluoroscopically guided interventions,” Dr. Melissa L. Kirkwood said at the annual meeting of the Western Vascular Society. “These injuries are associated with a threshold radiation dose, above which the severity of injury increases with increasing dose. Instances of these injuries are mostly limited to case reports of coronary interventions, TIPS procedures, and neuroembolizations.”

These radiation-induced skin lesions can be classified as prompt, early, mid-term, or late depending on when they present following the fluoroscopically guided intervention. “The National Cancer Institute has defined four grades of skin injury, with the most frequent being transient erythema, a prompt reaction within the first 24 hours occurring at skin doses as low as 2 Gy,” said Dr. Kirkwood of the division of vascular and endovascular surgery at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas. “With increasing skin doses, more severe effects present themselves. Atrophy, ulceration, and necrosis are possibilities.”

She went on to note that fenestrated endovascular aneurysm repairs often require high doses of radiation, yet the prevalence of deterministic skin injury following these cases is unknown. In a recent study, Dr. Kirkwood and her associates retrospectively reviewed 61 complex fluoroscopically guided interventions that met substantial radiation dose level criteria (SRDL), which is defined by the National Council on Radiation and Protection Measurements as a reference air kerma (RAK) greater than or equal to 5 Gy (J. Vasc. Surg. 2014; 60[3]:742-8). “Despite mean peak skin doses as high as 6.5 Gy, ranging up to 18.5 Gy, we did not detect any skin injuries in this cohort,” Dr. Kirkwood said. “That study, however, was limited by its retrospective design. There was no postoperative protocol in place to ensure that a thorough skin exam was performed on each patient at every follow-up visit. Therefore, we hypothesized that a more thorough postoperative follow-up of patients would detect some skin injury following these cases.”

For the current study, she and her associates sought to examine the prevalence of deterministic effects after FEVAR as well as well as any patient characteristics that may predispose patients to skin injury.

In June 2013, the researchers implemented a new policy regarding the follow-up of FEVAR patients, which involved a full skin exam at postoperative week 2 and 4, and at 3 and 6 months, as well as questioning patients about any skin-related complaints. For the current study, they retrospectively reviewed all FEVARs over a 7-month period after the change in policy and highlighted all the cases that reached a RAK of 5 Gy or greater. The RAK was the dose metric used in this study. It is a measure of the radiation dose to air at the interventional reference point, which, on standard fluoroscopes, is 15 cm along the beam axis toward the focal spot from isocenter. Dr. Kirkwood characterized RAK as “the best real-time indicator of patient dose, because it roughly estimates the dose at the entry point on the patient’s skin.” Peak skin dose, a dose index, and simulated skin dose maps were calculated using customized software employing input data from fluoroscopic machine logs.

Of 317 cases performed, 22 met or exceeded a RAK of 5 Gy. Of these, 21 were FEVARs and one was an embolization. Most patients (91%) were male and their mean body mass index was 30 kg/m2. Comorbidities and risk factors for skin injury included smoking, diabetes, and the concomitant applications of chemotherapeutic agents.

Dr. Kirkwood reported that the average RAK for all FEVARs was 8 Gy, with a range of 5-11 Gy. Slightly more than half of patients (52%) had multiple fluoroscopically guided interventions within 6 months of their SRDL event. The average RAK for this subset of patients was 10 Gy (range of 5 to 15).

The mean peak skin dose for all FEVARs was 5 Gy (a range of 2 to 10 Gy), and the dose index was 0.69. The average peak skin dose for the subset of patients with multiple procedures was 7 Gy (a range of 3 to 9 Gy).

In terms of the follow-up, all 21 FEVAR patients were examined at the 1- or 2-week mark, 81% were examined at 1 month, 52% were examined at 3 months, and 62% were examined at 6 months. No radiation skin injuries were reported. “Based on the published data, we would expect to see all grades of skin injury, especially in the cohort of the 5-10 Gy,” Dr. Kirkwood said.

In the previous study, conducted prior to the new follow-up policy, the dose index for FEVARs was 0.78, “meaning that the peak skin dose that the patient received could be roughly estimated as 78% of the RAK dose displayed on the monitor,” Dr. Kirkwood explained. “In the current work, the dose index decreased to 60%. This suggests that surgeons in our group have now more appropriately and effectively employed strategies to decrease radiation dose to the patient. However, even when the best operating practice is employed, FEVARs still continue to require high radiation doses in order to complete. “

The present study demonstrated that deterministic skin injuries “are uncommon after FEVAR, even at high RAK levels and regardless of cumulative dose,” she concluded. “Even with more comprehensive patient follow-up, the fact that no skin injuries were reported suggests that skin injuries in this patient cohort are less prevalent than the published guidelines would predict.”

Dr. Kirkwood reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

CORONADO, CALIF. – Skin injury following fenestrated endovascular aortic stent grafting is less prevalent than expected, results from a single-center retrospective study showed.

“Radiation-induced skin injury is a serious potential complication of fluoroscopically guided interventions,” Dr. Melissa L. Kirkwood said at the annual meeting of the Western Vascular Society. “These injuries are associated with a threshold radiation dose, above which the severity of injury increases with increasing dose. Instances of these injuries are mostly limited to case reports of coronary interventions, TIPS procedures, and neuroembolizations.”

These radiation-induced skin lesions can be classified as prompt, early, mid-term, or late depending on when they present following the fluoroscopically guided intervention. “The National Cancer Institute has defined four grades of skin injury, with the most frequent being transient erythema, a prompt reaction within the first 24 hours occurring at skin doses as low as 2 Gy,” said Dr. Kirkwood of the division of vascular and endovascular surgery at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas. “With increasing skin doses, more severe effects present themselves. Atrophy, ulceration, and necrosis are possibilities.”

She went on to note that fenestrated endovascular aneurysm repairs often require high doses of radiation, yet the prevalence of deterministic skin injury following these cases is unknown. In a recent study, Dr. Kirkwood and her associates retrospectively reviewed 61 complex fluoroscopically guided interventions that met substantial radiation dose level criteria (SRDL), which is defined by the National Council on Radiation and Protection Measurements as a reference air kerma (RAK) greater than or equal to 5 Gy (J. Vasc. Surg. 2014; 60[3]:742-8). “Despite mean peak skin doses as high as 6.5 Gy, ranging up to 18.5 Gy, we did not detect any skin injuries in this cohort,” Dr. Kirkwood said. “That study, however, was limited by its retrospective design. There was no postoperative protocol in place to ensure that a thorough skin exam was performed on each patient at every follow-up visit. Therefore, we hypothesized that a more thorough postoperative follow-up of patients would detect some skin injury following these cases.”

For the current study, she and her associates sought to examine the prevalence of deterministic effects after FEVAR as well as well as any patient characteristics that may predispose patients to skin injury.

In June 2013, the researchers implemented a new policy regarding the follow-up of FEVAR patients, which involved a full skin exam at postoperative week 2 and 4, and at 3 and 6 months, as well as questioning patients about any skin-related complaints. For the current study, they retrospectively reviewed all FEVARs over a 7-month period after the change in policy and highlighted all the cases that reached a RAK of 5 Gy or greater. The RAK was the dose metric used in this study. It is a measure of the radiation dose to air at the interventional reference point, which, on standard fluoroscopes, is 15 cm along the beam axis toward the focal spot from isocenter. Dr. Kirkwood characterized RAK as “the best real-time indicator of patient dose, because it roughly estimates the dose at the entry point on the patient’s skin.” Peak skin dose, a dose index, and simulated skin dose maps were calculated using customized software employing input data from fluoroscopic machine logs.

Of 317 cases performed, 22 met or exceeded a RAK of 5 Gy. Of these, 21 were FEVARs and one was an embolization. Most patients (91%) were male and their mean body mass index was 30 kg/m2. Comorbidities and risk factors for skin injury included smoking, diabetes, and the concomitant applications of chemotherapeutic agents.

Dr. Kirkwood reported that the average RAK for all FEVARs was 8 Gy, with a range of 5-11 Gy. Slightly more than half of patients (52%) had multiple fluoroscopically guided interventions within 6 months of their SRDL event. The average RAK for this subset of patients was 10 Gy (range of 5 to 15).

The mean peak skin dose for all FEVARs was 5 Gy (a range of 2 to 10 Gy), and the dose index was 0.69. The average peak skin dose for the subset of patients with multiple procedures was 7 Gy (a range of 3 to 9 Gy).

In terms of the follow-up, all 21 FEVAR patients were examined at the 1- or 2-week mark, 81% were examined at 1 month, 52% were examined at 3 months, and 62% were examined at 6 months. No radiation skin injuries were reported. “Based on the published data, we would expect to see all grades of skin injury, especially in the cohort of the 5-10 Gy,” Dr. Kirkwood said.

In the previous study, conducted prior to the new follow-up policy, the dose index for FEVARs was 0.78, “meaning that the peak skin dose that the patient received could be roughly estimated as 78% of the RAK dose displayed on the monitor,” Dr. Kirkwood explained. “In the current work, the dose index decreased to 60%. This suggests that surgeons in our group have now more appropriately and effectively employed strategies to decrease radiation dose to the patient. However, even when the best operating practice is employed, FEVARs still continue to require high radiation doses in order to complete. “

The present study demonstrated that deterministic skin injuries “are uncommon after FEVAR, even at high RAK levels and regardless of cumulative dose,” she concluded. “Even with more comprehensive patient follow-up, the fact that no skin injuries were reported suggests that skin injuries in this patient cohort are less prevalent than the published guidelines would predict.”

Dr. Kirkwood reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

AT THE WESTERN VASCULAR SOCIETY ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: No skin injuries were found after fenestrated endovascular aortic stent grafts (FEVAR) cases that involved high radiation doses.

Major finding: Even though the average reference air kerma (RAK) for all FEVARs was 8 Gy, with a range of 5-11 Gy, no radiation skin injuries were reported.

Data source: An single-center analysis of 21 FEVARs over a 7-month period that reached a RAK of 5 Gy or greater.

Disclosures: Dr. Kirkwood reported having no financial disclosures.

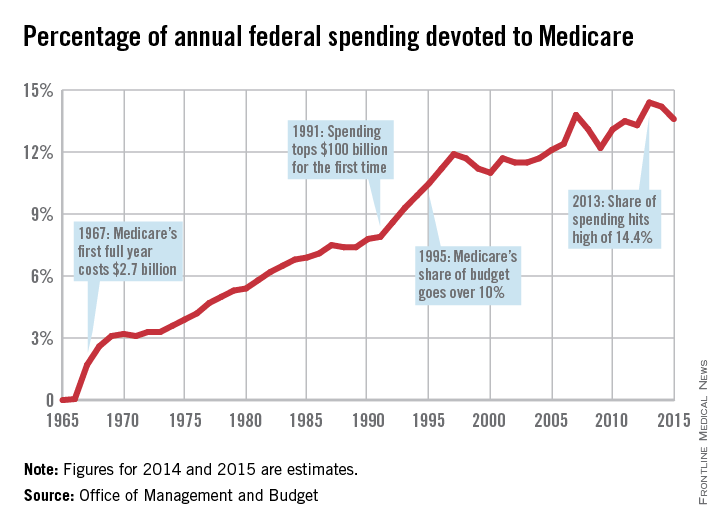

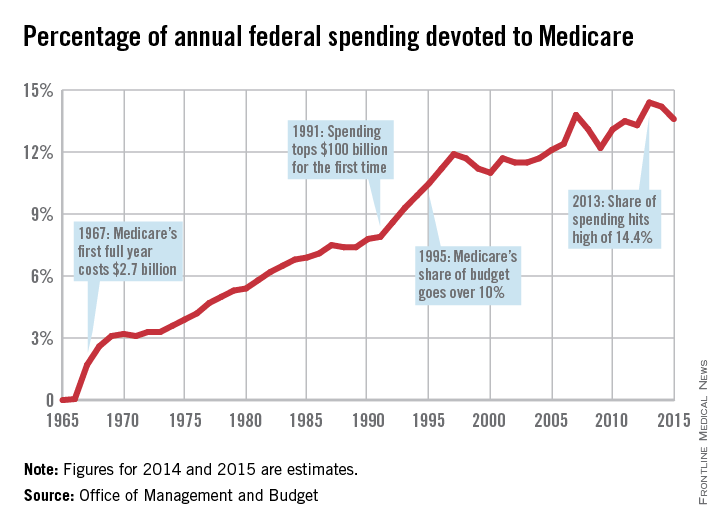

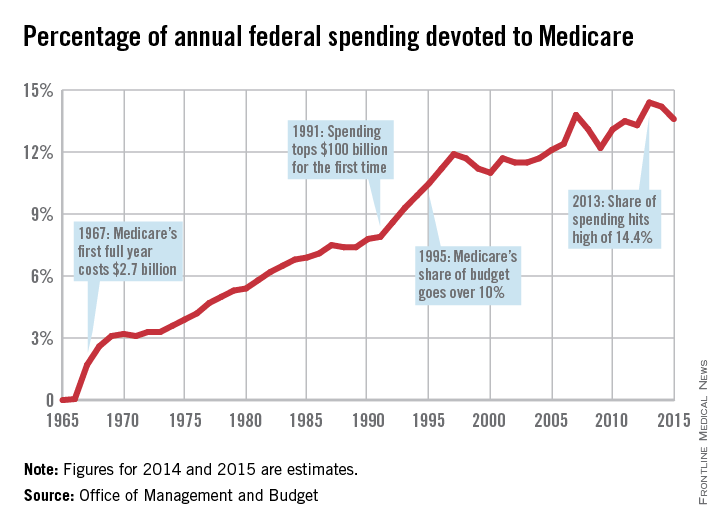

CMS will hold 2015 Medicare payments for 2 weeks

Doctors may have to wait a few extra days to get paid for Medicare services they administer, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services announced.

Claims submitted during the first 14 days of 2015 and dated within that time period will be held to allow for the corrections of errors in the 2015 physician fee schedule. Claims submitted during that time but dated in 2014 will be processed normally. Contractors are expected to process the early 2015 claims beginning Jan. 15.

CMS expects minimal impact to physicians, as it is not required to pay clean electronic claims sooner than 14 days under law.

“I think this will have minimum impact,” American Academy of Family Physicians President Robert Wergin said in an interview. “It does affect your cash flow, but it has happened in the past, particularly around the time with SGR patches.”

Medicare tends to be among the faster payers in general, and the 14-day delay should not create any significant hardship as physicians should be prepared for this, Dr. Wergin added.

Doctors may have to wait a few extra days to get paid for Medicare services they administer, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services announced.

Claims submitted during the first 14 days of 2015 and dated within that time period will be held to allow for the corrections of errors in the 2015 physician fee schedule. Claims submitted during that time but dated in 2014 will be processed normally. Contractors are expected to process the early 2015 claims beginning Jan. 15.

CMS expects minimal impact to physicians, as it is not required to pay clean electronic claims sooner than 14 days under law.

“I think this will have minimum impact,” American Academy of Family Physicians President Robert Wergin said in an interview. “It does affect your cash flow, but it has happened in the past, particularly around the time with SGR patches.”

Medicare tends to be among the faster payers in general, and the 14-day delay should not create any significant hardship as physicians should be prepared for this, Dr. Wergin added.

Doctors may have to wait a few extra days to get paid for Medicare services they administer, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services announced.

Claims submitted during the first 14 days of 2015 and dated within that time period will be held to allow for the corrections of errors in the 2015 physician fee schedule. Claims submitted during that time but dated in 2014 will be processed normally. Contractors are expected to process the early 2015 claims beginning Jan. 15.

CMS expects minimal impact to physicians, as it is not required to pay clean electronic claims sooner than 14 days under law.

“I think this will have minimum impact,” American Academy of Family Physicians President Robert Wergin said in an interview. “It does affect your cash flow, but it has happened in the past, particularly around the time with SGR patches.”

Medicare tends to be among the faster payers in general, and the 14-day delay should not create any significant hardship as physicians should be prepared for this, Dr. Wergin added.

Charging doctors with homicide

Question: Charges of homicide have been successfully brought against doctors in the following situations except:

A. Withholding life-sustaining treatment.

B. Euthanasia.

C. Negligent treatment of a patient.

D. Overprescription of controlled substances.

Answer: A. Homicideis any act that causes the death of a human being with criminal intent and without legal justification. It comprises several crimes of varying severity, with murder being the most serious (requiring “malice aforethought”). Depending on the intent of the perpetrator and/or the presence of mitigating/aggravating circumstances, jurisdictions have subdivided homicide into categories such as first- and second-degree murder, voluntary and involuntary manslaughter, negligent homicide, and others.

Discontinuing futile medical treatment that ends with patient demise raises the specter of criminal prosecution for homicide. However, prosecution of doctors under such circumstances has failed. The seminal case is Barber v. Superior Court (147 Cal. App. 3d 1006 (1983)), in which the state of California brought murder charges against two doctors for discontinuing intravenous fluids and nutrition in a comatose patient.

The patient, a 55-year-old security guard, sustained a cardiopulmonary arrest following surgery for intestinal obstruction. Irreversible brain damage resulted, leaving him in a vegetative state. His family allegedly requested that life support measures and intravenous fluids be discontinued, to which the doctors complied, and the patient died 6 days later.

After a preliminary pretrial hearing, the magistrate dismissed the charges; but a trial court reinstated them. The court of appeals, however, viewed the defendant’s conduct in discontinuing intravenous fluids as an omission rather than an affirmative action, and found that a physician has no duty to continue treatment once it is proven to be ineffective.

The appeals court recognized that “a physician is authorized under the standards of medical practice to discontinue a form of therapy which in his medical judgment is useless. … If the treating physicians have determined that continued use of a respirator is useless, then they may decide to discontinue it without fear of civil or criminal liability.”

In rejecting the distinction between ordinary and extraordinary care, the court dismissed the prosecutor’s contention that unlike the respirator, fluids and nutrition represented ordinary care and therefore should never be withheld.

It concluded that “the petitioners’ omission to continue treatment under the circumstances, though intentional and with knowledge that the patient would die, was not an unlawful failure to perform a legal duty.” And because no criminal liability attaches for failure to act (i.e., an omission) unless there is a legal duty to act affirmatively, it issued a writ of prohibition restraining the lower court from taking any further action on the matter.

The U.S. Supreme Court has since validated the distinction between “letting die” and an affirmative action taken with the intention to cause death, such as the administration of a lethal injection. The former is ethical and legal, conforming to medical norms, while the latter amounts to murder (Vacco v. Quill (117 S. Ct. 2293 (1997)).

With these developments, physicians therefore need not worry about criminal prosecution for carrying out Barber-like noneuthanasia, end-of-life actions that result in the death of their patients.

On the other hand, those who act directly to end the life of a patient, even one who freely requests death, may face criminal prosecution.

The most notorious example is that of retired Michigan pathologist Dr. Jack Kevorkian, who was found guilty of the second-degree murder of Thomas Youk, a 52-year-old race-car driver with terminal Lou Gehrig’s disease. Dr. Kevorkian injected a lethal mixture of Seconal, Anectine, and potassium chloride to end the patient’s life.

At trial, Dr. Kevorkian dismissed his lawyer and served ineffectively in his own defense, never taking the witness stand. Found guilty by a jury and sentenced to 10-25 years in prison, he served just more than 8 years until 2007, when he was released for good behavior. Previous charges by the state of Michigan against Dr. Kevorkian for assisting in the suicide of some 130 patients had proven unsuccessful.

This case spawned a nationwide debate on physician-directed deaths, with a few states now legalizing physician-assisted suicide, although euthanasia remains illegal throughout the nation.

In general, the remedy sought in a medical wrongful death case lies in a malpractice civil lawsuit against the negligent doctor. Sometimes, the plaintiff may assert that there was gross negligence where the conduct was particularly blameworthy, and if proven, the jury may award punitive damages.

Rarely, however, does the level of misconduct rise to that of criminal negligence. Here, the burden of proof for a conviction requires evidence beyond reasonable doubt, rather than the lower “more probable than not” evidentiary standard required in a civil lawsuit.

However, in cases where the physician’s conduct has markedly deviated from the standard of care, doctors have been successfully prosecuted for their “criminal” conduct.

For example, in an English case, an anesthesiologist was convicted of manslaughter in the death of a patient undergoing surgery for a detached retina. During surgery, the patient’s ventilation was interrupted because of accidental disconnection of the endotracheal tube for 4 minutes, leading to a cardiac arrest. An alarm had apparently sounded but was not noticed. The injury would not have occurred had the doctor attended to the patient instead of being away from the operating room.

The tragic death of pop star Michael Jackson in 2009 is another example. Dr. Conrad Murray, a cardiologist who was Jackson’s personal physician, had used the surgical anesthetic propofol to treat Jackson’s insomnia in a bedroom setting without monitoring or resuscitation equipment. Concurrent use of the sedative lorazepam exacerbated the effect of propofol. The prosecution characterized Dr. Murray’s conduct as “egregious, unethical, and unconscionable,” which violated medical standards and amounted to criminal negligence. He was found guilty of involuntary manslaughter, and the state sentenced him to a 4-year prison term.

A new trend appears to be developing toward prosecuting doctors whose overprescription of controlled substances results in patient deaths.

According to a recent news report, New York for the first time convicted a doctor of manslaughter in the overdose deaths of patients from oxycodone and Xanax.1 Some of the patients were reportedly prescribed as many as 500-800 pills over a 5-6 week period. Dr. Stan Li, an anesthesiologist and pain management specialist, allegedly saw up to 90 patients a day in his Queens, N.Y., weekend storefront clinic, charging them on a per-prescription basis. In his defense, Dr. Li claimed that he was simply trying to help suffering people who misused medications and who misled him (“tough patients and good liars”).

Meanwhile, a similar scenario played out in Oklahoma.2 There, Dr. William Valuck, a pain management doctor, pleaded guilty to eight counts of second-degree murder in connection with several drug overdose deaths. He entered into a plea bargain with Oklahoma prosecutors and will serve 8 years in prison. Dr. Valuck had reportedly prescribed more controlled drugs than any other physician in the state of Oklahoma, which included hydrocodone, oxycodone, alprazolam, Valium, and Soma, sometimes as many as 600 pills at a time. He allegedly accepted only cash payment for the office visits, and review of his patient files revealed inadequate assessment of patient complaints or physical findings to justify the prescriptions.

Most physicians are unlikely to ever face the specter of criminal prosecution based on their medical performance. Only in the most egregious of circumstances have physicians been successfully prosecuted for homicide.

As requests for physicians to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatments grow, physicians may find themselves questioning what acts or omissions they may legally perform. Unless the legal landscape changes, however, it appears that the forgoing of life-sustaining treatments in the typical clinical context will not subject physicians to criminal prosecution.

References

1. “NY doctor convicted of manslaughter in 2 overdoses,” July 18, 2014 (http://bigstory.ap.org/article/ny-doctor-convicted-2-patients-overdose-deaths).

2. “Ex-doctor pleads guilty in overdose deaths,” Aug. 13, 2014 (www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2014/08/13/ex-doctor-guilty-deaths/14022735).

Dr. Tan is professor emeritus of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, and directs the St. Francis International Center for Healthcare Ethics in Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some of the articles in this series are adapted from the author’s 2006 book, “Medical Malpractice: Understanding the Law, Managing the Risk,” and his 2012 Halsbury treatise, “Medical Negligence and Professional Misconduct.” For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

Question: Charges of homicide have been successfully brought against doctors in the following situations except:

A. Withholding life-sustaining treatment.

B. Euthanasia.

C. Negligent treatment of a patient.

D. Overprescription of controlled substances.

Answer: A. Homicideis any act that causes the death of a human being with criminal intent and without legal justification. It comprises several crimes of varying severity, with murder being the most serious (requiring “malice aforethought”). Depending on the intent of the perpetrator and/or the presence of mitigating/aggravating circumstances, jurisdictions have subdivided homicide into categories such as first- and second-degree murder, voluntary and involuntary manslaughter, negligent homicide, and others.

Discontinuing futile medical treatment that ends with patient demise raises the specter of criminal prosecution for homicide. However, prosecution of doctors under such circumstances has failed. The seminal case is Barber v. Superior Court (147 Cal. App. 3d 1006 (1983)), in which the state of California brought murder charges against two doctors for discontinuing intravenous fluids and nutrition in a comatose patient.

The patient, a 55-year-old security guard, sustained a cardiopulmonary arrest following surgery for intestinal obstruction. Irreversible brain damage resulted, leaving him in a vegetative state. His family allegedly requested that life support measures and intravenous fluids be discontinued, to which the doctors complied, and the patient died 6 days later.

After a preliminary pretrial hearing, the magistrate dismissed the charges; but a trial court reinstated them. The court of appeals, however, viewed the defendant’s conduct in discontinuing intravenous fluids as an omission rather than an affirmative action, and found that a physician has no duty to continue treatment once it is proven to be ineffective.

The appeals court recognized that “a physician is authorized under the standards of medical practice to discontinue a form of therapy which in his medical judgment is useless. … If the treating physicians have determined that continued use of a respirator is useless, then they may decide to discontinue it without fear of civil or criminal liability.”

In rejecting the distinction between ordinary and extraordinary care, the court dismissed the prosecutor’s contention that unlike the respirator, fluids and nutrition represented ordinary care and therefore should never be withheld.

It concluded that “the petitioners’ omission to continue treatment under the circumstances, though intentional and with knowledge that the patient would die, was not an unlawful failure to perform a legal duty.” And because no criminal liability attaches for failure to act (i.e., an omission) unless there is a legal duty to act affirmatively, it issued a writ of prohibition restraining the lower court from taking any further action on the matter.

The U.S. Supreme Court has since validated the distinction between “letting die” and an affirmative action taken with the intention to cause death, such as the administration of a lethal injection. The former is ethical and legal, conforming to medical norms, while the latter amounts to murder (Vacco v. Quill (117 S. Ct. 2293 (1997)).

With these developments, physicians therefore need not worry about criminal prosecution for carrying out Barber-like noneuthanasia, end-of-life actions that result in the death of their patients.

On the other hand, those who act directly to end the life of a patient, even one who freely requests death, may face criminal prosecution.

The most notorious example is that of retired Michigan pathologist Dr. Jack Kevorkian, who was found guilty of the second-degree murder of Thomas Youk, a 52-year-old race-car driver with terminal Lou Gehrig’s disease. Dr. Kevorkian injected a lethal mixture of Seconal, Anectine, and potassium chloride to end the patient’s life.

At trial, Dr. Kevorkian dismissed his lawyer and served ineffectively in his own defense, never taking the witness stand. Found guilty by a jury and sentenced to 10-25 years in prison, he served just more than 8 years until 2007, when he was released for good behavior. Previous charges by the state of Michigan against Dr. Kevorkian for assisting in the suicide of some 130 patients had proven unsuccessful.

This case spawned a nationwide debate on physician-directed deaths, with a few states now legalizing physician-assisted suicide, although euthanasia remains illegal throughout the nation.

In general, the remedy sought in a medical wrongful death case lies in a malpractice civil lawsuit against the negligent doctor. Sometimes, the plaintiff may assert that there was gross negligence where the conduct was particularly blameworthy, and if proven, the jury may award punitive damages.