User login

Gene therapy appears effective against WAS

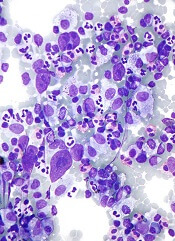

Photo by Chad McNeeley

Results of a small study suggest gene therapy can lead to clinical improvements in children and teens with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS).

The gene therapy—autologous, gene-corrected hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) given along with chemotherapy—improved infectious complications, severe eczema, and symptoms of autoimmunity in 6 of the 7 patients studied.

The therapy also reduced patients’ use of blood products and the amount of time they spent in the hospital.

Marina Cavazzana, MD, PhD, of Necker Children’s Hospital in Paris, France, and colleagues reported these results in JAMA. The study was sponsored by Genethon.

The researchers noted that WAS is caused by loss-of-function mutations in the WAS gene. The condition is characterized by thrombocytopenia, eczema, and recurring infections. In the absence of definitive treatment, patients with classic WAS generally do not survive beyond their second or third decade of life.

Partially HLA-matched, allogeneic HSC transplant is often curative, but it is associated with a high incidence of complications. Dr Cavazzana and colleagues speculated that transplanting autologous, gene-corrected HSCs may be an effective and potentially safer alternative.

So the team assessed the outcomes and safety of autologous HSC gene therapy in 7 patients (age range, 0.8-15.5 years) with severe WAS who lacked HLA antigen-matched related or unrelated HSC donors.

Patients were enrolled in France and England and treated between December 2010 and January 2014. Follow-up ranged from 9 months to 42 months.

The treatment involved collecting mutated HSCs from patients and correcting the cells in the lab by introducing a healthy WAS gene using a lentiviral vector developed and produced by Genethon. The corrected cells were reinjected into patients who, in parallel, received chemotherapy to suppress their defective stem cells and autoimmune cells to make room for new, corrected cells.

Six of the 7 patients saw clinical improvements after this treatment. One patient died of pre-existing, treatment-refractory infectious disease.

In the 6 surviving patients, infectious complications resolved after gene therapy, and prophylactic antibiotic therapy was successfully discontinued in 3 cases. Severe eczema resolved in all affected patients, as did signs and symptoms of autoimmunity.

There were no severe bleeding episodes after treatment. And, at last follow-up, none of the 6 surviving patients required blood product support.

The median number of hospitalization days decreased from 25 during the 2 years before treatment to 0 during the 2 years after treatment.

“[T]he patients showed a significant clinical improvement due to the re-expression of the protein WASp in the cells of the immune system,” Dr

Cavazzana said.

However, the researchers also noted that the interpretation of these results is constrained by the small number of patients studied. So the team said they could not draw conclusions on long-term outcomes and safety without further follow-up and additional trials. ![]()

Photo by Chad McNeeley

Results of a small study suggest gene therapy can lead to clinical improvements in children and teens with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS).

The gene therapy—autologous, gene-corrected hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) given along with chemotherapy—improved infectious complications, severe eczema, and symptoms of autoimmunity in 6 of the 7 patients studied.

The therapy also reduced patients’ use of blood products and the amount of time they spent in the hospital.

Marina Cavazzana, MD, PhD, of Necker Children’s Hospital in Paris, France, and colleagues reported these results in JAMA. The study was sponsored by Genethon.

The researchers noted that WAS is caused by loss-of-function mutations in the WAS gene. The condition is characterized by thrombocytopenia, eczema, and recurring infections. In the absence of definitive treatment, patients with classic WAS generally do not survive beyond their second or third decade of life.

Partially HLA-matched, allogeneic HSC transplant is often curative, but it is associated with a high incidence of complications. Dr Cavazzana and colleagues speculated that transplanting autologous, gene-corrected HSCs may be an effective and potentially safer alternative.

So the team assessed the outcomes and safety of autologous HSC gene therapy in 7 patients (age range, 0.8-15.5 years) with severe WAS who lacked HLA antigen-matched related or unrelated HSC donors.

Patients were enrolled in France and England and treated between December 2010 and January 2014. Follow-up ranged from 9 months to 42 months.

The treatment involved collecting mutated HSCs from patients and correcting the cells in the lab by introducing a healthy WAS gene using a lentiviral vector developed and produced by Genethon. The corrected cells were reinjected into patients who, in parallel, received chemotherapy to suppress their defective stem cells and autoimmune cells to make room for new, corrected cells.

Six of the 7 patients saw clinical improvements after this treatment. One patient died of pre-existing, treatment-refractory infectious disease.

In the 6 surviving patients, infectious complications resolved after gene therapy, and prophylactic antibiotic therapy was successfully discontinued in 3 cases. Severe eczema resolved in all affected patients, as did signs and symptoms of autoimmunity.

There were no severe bleeding episodes after treatment. And, at last follow-up, none of the 6 surviving patients required blood product support.

The median number of hospitalization days decreased from 25 during the 2 years before treatment to 0 during the 2 years after treatment.

“[T]he patients showed a significant clinical improvement due to the re-expression of the protein WASp in the cells of the immune system,” Dr

Cavazzana said.

However, the researchers also noted that the interpretation of these results is constrained by the small number of patients studied. So the team said they could not draw conclusions on long-term outcomes and safety without further follow-up and additional trials. ![]()

Photo by Chad McNeeley

Results of a small study suggest gene therapy can lead to clinical improvements in children and teens with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS).

The gene therapy—autologous, gene-corrected hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) given along with chemotherapy—improved infectious complications, severe eczema, and symptoms of autoimmunity in 6 of the 7 patients studied.

The therapy also reduced patients’ use of blood products and the amount of time they spent in the hospital.

Marina Cavazzana, MD, PhD, of Necker Children’s Hospital in Paris, France, and colleagues reported these results in JAMA. The study was sponsored by Genethon.

The researchers noted that WAS is caused by loss-of-function mutations in the WAS gene. The condition is characterized by thrombocytopenia, eczema, and recurring infections. In the absence of definitive treatment, patients with classic WAS generally do not survive beyond their second or third decade of life.

Partially HLA-matched, allogeneic HSC transplant is often curative, but it is associated with a high incidence of complications. Dr Cavazzana and colleagues speculated that transplanting autologous, gene-corrected HSCs may be an effective and potentially safer alternative.

So the team assessed the outcomes and safety of autologous HSC gene therapy in 7 patients (age range, 0.8-15.5 years) with severe WAS who lacked HLA antigen-matched related or unrelated HSC donors.

Patients were enrolled in France and England and treated between December 2010 and January 2014. Follow-up ranged from 9 months to 42 months.

The treatment involved collecting mutated HSCs from patients and correcting the cells in the lab by introducing a healthy WAS gene using a lentiviral vector developed and produced by Genethon. The corrected cells were reinjected into patients who, in parallel, received chemotherapy to suppress their defective stem cells and autoimmune cells to make room for new, corrected cells.

Six of the 7 patients saw clinical improvements after this treatment. One patient died of pre-existing, treatment-refractory infectious disease.

In the 6 surviving patients, infectious complications resolved after gene therapy, and prophylactic antibiotic therapy was successfully discontinued in 3 cases. Severe eczema resolved in all affected patients, as did signs and symptoms of autoimmunity.

There were no severe bleeding episodes after treatment. And, at last follow-up, none of the 6 surviving patients required blood product support.

The median number of hospitalization days decreased from 25 during the 2 years before treatment to 0 during the 2 years after treatment.

“[T]he patients showed a significant clinical improvement due to the re-expression of the protein WASp in the cells of the immune system,” Dr

Cavazzana said.

However, the researchers also noted that the interpretation of these results is constrained by the small number of patients studied. So the team said they could not draw conclusions on long-term outcomes and safety without further follow-up and additional trials. ![]()

EBV-CTLs produce durable responses in EBV-LPD

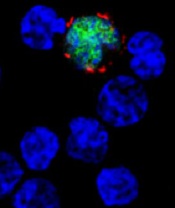

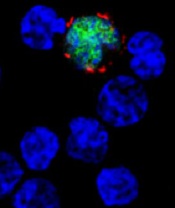

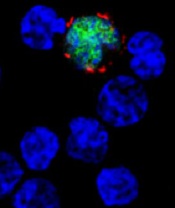

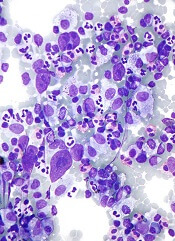

among uninfected cells (blue)

Image courtesy of NIH/

Benjamin Chaigne-Delalande

PHILADELPHIA—Cytotoxic T lymphocytes designed to target Epstein-Barr virus (EBV-CTLs) can elicit durable responses in patients

with EBV–associated lymphoproliferative disorder (EBV-LPD), according to data presented at the AACRAnnual Meeting 2015.

Results from two trials showed that EBV-CTLs derived from a patient’s transplant donor could produce a response rate of 62%, and EBV-CTLs derived from third-party donors could produce a response rate of 61%.

Study investigators noted that, with the achievement of complete response (CR), remission proved durable. And, unlike with chemotherapy, partial responses (PRs) to EBV-CTLs were durable as well.

The team presented these results as abstract CT107.*

“The purpose of our clinical trials was to see if giving T cells from a normal-immune individual that were expanded in culture and stimulated to respond to multiple proteins from the Epstein-Barr virus could provide a safe and effective treatment,” said Richard J. O’Reilly, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

“The good news from our two clinical trials is that EBV-CTLs generated from either the patient’s transplant donor or from the bank of normal donor T cells developed at Memorial Sloan Kettering put aggressive EBV-LPD that had failed to respond to rituximab into long-lasting remission in more than 60% of patients.”

In the first trial, 26 patients with EBV-LPD received EBV-CTLs generated from their transplant donor. Thirteen of these patients had previously received rituximab, and 16 had high-risk disease.

Thirteen patients in this trial received HLA-matched, EBV-CTLs from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center bank of EBV-CTLs generated from third-party, healthy donors. All 13 patients had high-risk disease, and 12 had received prior rituximab.

Dr O’Reilly noted that good results were observed with EBV-CTLs from both sources in this trial. And because EBV-CTLs from the bank are available immediately, he and his team used only EBV-CTLs from the bank when treating the 18 patients enrolled in the second trial.

Among the 39 patients enrolled in the first trial, 23 had a CR, none had a PR, and 2 had stable disease.

For patients who received EBV-CTLs from their primary donor, the combined rate of CR and PR was 62% (16 CRs). For patients who received third-party EBV-CTLs, the combined rate of CR and PR was 54% (7 CRs).

Sixteen of the patients who achieved a CR are still doing well, Dr O’Reilly said. Eight of these patients are alive more than 5 years after receiving EBV-CTLs, and 1 is alive more than 10 years after treatment.

Among the 18 patients enrolled in the second trial, 9 had a CR, 3 had a PR, and 1 had stable disease. The combined rate of CR and PR was 67%.

All of the patients who achieved a CR in this trial continue to do well, and the investigators will be following them long-term, Dr O’Reilly said.

He also noted that toxicities with EBV-CTLs were minimal, and there were no treatment-related deaths. None of the patients developed cytokine release syndrome or graft-vs-host disease requiring systemic therapy.

“The EBV-CTLs work well for the majority of recipients,” Dr O’Reilly said. “However, the responses became clinically evident only after the T cells expanded in vivo, which took about 7 to 14 days. We are rigorously pursuing the development of biomarkers or other tests to predict response earlier.”

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center has entered into an option agreement with Atara Biotherapeutics to further develop EBV-CTLs for clinical use. However, the data presented at AACR were accrued prior to that agreement.

Last month, the US Food and Drug Administration granted breakthrough therapy designation to EBV-CTLs generated from third-party donors for the treatment of patients with rituximab-refractory EBV-LPD. ![]()

*Information in the abstract differs from that presented at the meeting.

among uninfected cells (blue)

Image courtesy of NIH/

Benjamin Chaigne-Delalande

PHILADELPHIA—Cytotoxic T lymphocytes designed to target Epstein-Barr virus (EBV-CTLs) can elicit durable responses in patients

with EBV–associated lymphoproliferative disorder (EBV-LPD), according to data presented at the AACRAnnual Meeting 2015.

Results from two trials showed that EBV-CTLs derived from a patient’s transplant donor could produce a response rate of 62%, and EBV-CTLs derived from third-party donors could produce a response rate of 61%.

Study investigators noted that, with the achievement of complete response (CR), remission proved durable. And, unlike with chemotherapy, partial responses (PRs) to EBV-CTLs were durable as well.

The team presented these results as abstract CT107.*

“The purpose of our clinical trials was to see if giving T cells from a normal-immune individual that were expanded in culture and stimulated to respond to multiple proteins from the Epstein-Barr virus could provide a safe and effective treatment,” said Richard J. O’Reilly, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

“The good news from our two clinical trials is that EBV-CTLs generated from either the patient’s transplant donor or from the bank of normal donor T cells developed at Memorial Sloan Kettering put aggressive EBV-LPD that had failed to respond to rituximab into long-lasting remission in more than 60% of patients.”

In the first trial, 26 patients with EBV-LPD received EBV-CTLs generated from their transplant donor. Thirteen of these patients had previously received rituximab, and 16 had high-risk disease.

Thirteen patients in this trial received HLA-matched, EBV-CTLs from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center bank of EBV-CTLs generated from third-party, healthy donors. All 13 patients had high-risk disease, and 12 had received prior rituximab.

Dr O’Reilly noted that good results were observed with EBV-CTLs from both sources in this trial. And because EBV-CTLs from the bank are available immediately, he and his team used only EBV-CTLs from the bank when treating the 18 patients enrolled in the second trial.

Among the 39 patients enrolled in the first trial, 23 had a CR, none had a PR, and 2 had stable disease.

For patients who received EBV-CTLs from their primary donor, the combined rate of CR and PR was 62% (16 CRs). For patients who received third-party EBV-CTLs, the combined rate of CR and PR was 54% (7 CRs).

Sixteen of the patients who achieved a CR are still doing well, Dr O’Reilly said. Eight of these patients are alive more than 5 years after receiving EBV-CTLs, and 1 is alive more than 10 years after treatment.

Among the 18 patients enrolled in the second trial, 9 had a CR, 3 had a PR, and 1 had stable disease. The combined rate of CR and PR was 67%.

All of the patients who achieved a CR in this trial continue to do well, and the investigators will be following them long-term, Dr O’Reilly said.

He also noted that toxicities with EBV-CTLs were minimal, and there were no treatment-related deaths. None of the patients developed cytokine release syndrome or graft-vs-host disease requiring systemic therapy.

“The EBV-CTLs work well for the majority of recipients,” Dr O’Reilly said. “However, the responses became clinically evident only after the T cells expanded in vivo, which took about 7 to 14 days. We are rigorously pursuing the development of biomarkers or other tests to predict response earlier.”

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center has entered into an option agreement with Atara Biotherapeutics to further develop EBV-CTLs for clinical use. However, the data presented at AACR were accrued prior to that agreement.

Last month, the US Food and Drug Administration granted breakthrough therapy designation to EBV-CTLs generated from third-party donors for the treatment of patients with rituximab-refractory EBV-LPD. ![]()

*Information in the abstract differs from that presented at the meeting.

among uninfected cells (blue)

Image courtesy of NIH/

Benjamin Chaigne-Delalande

PHILADELPHIA—Cytotoxic T lymphocytes designed to target Epstein-Barr virus (EBV-CTLs) can elicit durable responses in patients

with EBV–associated lymphoproliferative disorder (EBV-LPD), according to data presented at the AACRAnnual Meeting 2015.

Results from two trials showed that EBV-CTLs derived from a patient’s transplant donor could produce a response rate of 62%, and EBV-CTLs derived from third-party donors could produce a response rate of 61%.

Study investigators noted that, with the achievement of complete response (CR), remission proved durable. And, unlike with chemotherapy, partial responses (PRs) to EBV-CTLs were durable as well.

The team presented these results as abstract CT107.*

“The purpose of our clinical trials was to see if giving T cells from a normal-immune individual that were expanded in culture and stimulated to respond to multiple proteins from the Epstein-Barr virus could provide a safe and effective treatment,” said Richard J. O’Reilly, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

“The good news from our two clinical trials is that EBV-CTLs generated from either the patient’s transplant donor or from the bank of normal donor T cells developed at Memorial Sloan Kettering put aggressive EBV-LPD that had failed to respond to rituximab into long-lasting remission in more than 60% of patients.”

In the first trial, 26 patients with EBV-LPD received EBV-CTLs generated from their transplant donor. Thirteen of these patients had previously received rituximab, and 16 had high-risk disease.

Thirteen patients in this trial received HLA-matched, EBV-CTLs from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center bank of EBV-CTLs generated from third-party, healthy donors. All 13 patients had high-risk disease, and 12 had received prior rituximab.

Dr O’Reilly noted that good results were observed with EBV-CTLs from both sources in this trial. And because EBV-CTLs from the bank are available immediately, he and his team used only EBV-CTLs from the bank when treating the 18 patients enrolled in the second trial.

Among the 39 patients enrolled in the first trial, 23 had a CR, none had a PR, and 2 had stable disease.

For patients who received EBV-CTLs from their primary donor, the combined rate of CR and PR was 62% (16 CRs). For patients who received third-party EBV-CTLs, the combined rate of CR and PR was 54% (7 CRs).

Sixteen of the patients who achieved a CR are still doing well, Dr O’Reilly said. Eight of these patients are alive more than 5 years after receiving EBV-CTLs, and 1 is alive more than 10 years after treatment.

Among the 18 patients enrolled in the second trial, 9 had a CR, 3 had a PR, and 1 had stable disease. The combined rate of CR and PR was 67%.

All of the patients who achieved a CR in this trial continue to do well, and the investigators will be following them long-term, Dr O’Reilly said.

He also noted that toxicities with EBV-CTLs were minimal, and there were no treatment-related deaths. None of the patients developed cytokine release syndrome or graft-vs-host disease requiring systemic therapy.

“The EBV-CTLs work well for the majority of recipients,” Dr O’Reilly said. “However, the responses became clinically evident only after the T cells expanded in vivo, which took about 7 to 14 days. We are rigorously pursuing the development of biomarkers or other tests to predict response earlier.”

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center has entered into an option agreement with Atara Biotherapeutics to further develop EBV-CTLs for clinical use. However, the data presented at AACR were accrued prior to that agreement.

Last month, the US Food and Drug Administration granted breakthrough therapy designation to EBV-CTLs generated from third-party donors for the treatment of patients with rituximab-refractory EBV-LPD. ![]()

*Information in the abstract differs from that presented at the meeting.

Gene appears key to HSC regulation

in the bone marrow

The gene Ash1l plays a key role in regulating the maintenance and self-renewal of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), according to a study published in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

The research provides new insight into how the body creates and maintains a healthy blood supply and immune system. It also opens new lines of inquiry about Ash1l’s potential role in cancers—like leukemia—that involve other members of the same gene family.

“If we find that Ash1l plays a role [in leukemia], that would open up avenues to try to block or slow down its activity pharmacologically,” said study author Ivan Maillard, MD, of the University of Michigan Medical School in Ann Arbor.

The Ash1l gene regulates the expression of multiple downstream homeotic genes, which help ensure the correct anatomical structure of a developing organism. And Ash1l is part of a family of genes that includes MLL1.

The researchers found that both Ash1l and MLL1 contribute to blood renewal. They observed mild defects in mice missing one gene or the other, but lacking both genes led to catastrophic deficiencies.

“We now have clear evidence that these genes cooperate to develop a healthy blood system,” Dr Maillard said.

He and his colleagues also found that Ash1l-deficient mice had normal numbers of HSCs during early development but a lack of HSCs in maturity—an indication the cells were not able to properly maintain themselves in the bone marrow.

Ash1l-deficient HSCs were unable to establish normal blood renewal after an HSC transplant. Moreover, Ash1l-deficient stem cells competed poorly with normal HSCs in the bone marrow and could easily be dislodged.

“By continuing to investigate the basic, underlying mechanisms [of blood renewal], we are helping to untangle the complex machinery . . . that may lay the foundation for new human treatments 5, 10, or 20 years from now,” Dr Maillard said. ![]()

in the bone marrow

The gene Ash1l plays a key role in regulating the maintenance and self-renewal of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), according to a study published in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

The research provides new insight into how the body creates and maintains a healthy blood supply and immune system. It also opens new lines of inquiry about Ash1l’s potential role in cancers—like leukemia—that involve other members of the same gene family.

“If we find that Ash1l plays a role [in leukemia], that would open up avenues to try to block or slow down its activity pharmacologically,” said study author Ivan Maillard, MD, of the University of Michigan Medical School in Ann Arbor.

The Ash1l gene regulates the expression of multiple downstream homeotic genes, which help ensure the correct anatomical structure of a developing organism. And Ash1l is part of a family of genes that includes MLL1.

The researchers found that both Ash1l and MLL1 contribute to blood renewal. They observed mild defects in mice missing one gene or the other, but lacking both genes led to catastrophic deficiencies.

“We now have clear evidence that these genes cooperate to develop a healthy blood system,” Dr Maillard said.

He and his colleagues also found that Ash1l-deficient mice had normal numbers of HSCs during early development but a lack of HSCs in maturity—an indication the cells were not able to properly maintain themselves in the bone marrow.

Ash1l-deficient HSCs were unable to establish normal blood renewal after an HSC transplant. Moreover, Ash1l-deficient stem cells competed poorly with normal HSCs in the bone marrow and could easily be dislodged.

“By continuing to investigate the basic, underlying mechanisms [of blood renewal], we are helping to untangle the complex machinery . . . that may lay the foundation for new human treatments 5, 10, or 20 years from now,” Dr Maillard said. ![]()

in the bone marrow

The gene Ash1l plays a key role in regulating the maintenance and self-renewal of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), according to a study published in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

The research provides new insight into how the body creates and maintains a healthy blood supply and immune system. It also opens new lines of inquiry about Ash1l’s potential role in cancers—like leukemia—that involve other members of the same gene family.

“If we find that Ash1l plays a role [in leukemia], that would open up avenues to try to block or slow down its activity pharmacologically,” said study author Ivan Maillard, MD, of the University of Michigan Medical School in Ann Arbor.

The Ash1l gene regulates the expression of multiple downstream homeotic genes, which help ensure the correct anatomical structure of a developing organism. And Ash1l is part of a family of genes that includes MLL1.

The researchers found that both Ash1l and MLL1 contribute to blood renewal. They observed mild defects in mice missing one gene or the other, but lacking both genes led to catastrophic deficiencies.

“We now have clear evidence that these genes cooperate to develop a healthy blood system,” Dr Maillard said.

He and his colleagues also found that Ash1l-deficient mice had normal numbers of HSCs during early development but a lack of HSCs in maturity—an indication the cells were not able to properly maintain themselves in the bone marrow.

Ash1l-deficient HSCs were unable to establish normal blood renewal after an HSC transplant. Moreover, Ash1l-deficient stem cells competed poorly with normal HSCs in the bone marrow and could easily be dislodged.

“By continuing to investigate the basic, underlying mechanisms [of blood renewal], we are helping to untangle the complex machinery . . . that may lay the foundation for new human treatments 5, 10, or 20 years from now,” Dr Maillard said. ![]()

Gene therapy superior to partially matched HSCT for SCID-X1

Photo by Chad McNeeley

Children with X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID-X1) who undergo gene therapy have fewer infections and hospitalizations than those who receive a hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) from a partially matched donor, according to a study published in Blood.

“Over the last decade, gene therapy has emerged as a viable alternative to a partial matched stem cell transplant for infants with SCID-X1,” said study author Fabien Touzot, MD, PhD, of Necker Children’s Hospital in Paris, France.

“To ensure that we are providing the best alternative therapy possible, we wanted to compare outcomes among infants treated with gene therapy and infants receiving partial matched transplants.”

Dr Touzot and his colleagues studied the medical records of 27 children who received either a partially matched HSCT (n=13) or gene therapy (n=14) for SCID-X1 at Necker Children’s Hospital between 1999 and 2013.

The children receiving half-matched transplants and the children receiving gene therapy had been followed for a median of 6 years and 12 years, respectively.

The researchers compared T-cell development among the patients, as well as key clinical outcomes such as infections and hospitalization.

The 14 children in the gene therapy group developed healthy immune cells faster than the 13 children in the half-matched transplant group. In fact, in the first 6 months after therapy, T-cell counts had reached normal values in 78% of the gene therapy patients, compared to 26% of the HSCT patients.

The more rapid growth of the immune system in gene therapy patients was also associated with faster resolution of disseminated BDG infections. These infections resolved in a median of 11 months in the gene therapy group, compared to 25.5 months in the half-matched transplant group.

Gene therapy patients also had fewer infection-related hospitalizations—3 hospitalizations in 3 patients, compared to 15 hospitalizations in 5 patients from the half-matched HSCT group.

“Our analysis suggests that gene therapy can put these incredibly sick children on the road to defending themselves against infection faster than a half-matched transplant,” Dr Touzot said. “These results suggest that, for patients without a fully matched stem cell donor, gene therapy is the next-best approach.” ![]()

Photo by Chad McNeeley

Children with X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID-X1) who undergo gene therapy have fewer infections and hospitalizations than those who receive a hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) from a partially matched donor, according to a study published in Blood.

“Over the last decade, gene therapy has emerged as a viable alternative to a partial matched stem cell transplant for infants with SCID-X1,” said study author Fabien Touzot, MD, PhD, of Necker Children’s Hospital in Paris, France.

“To ensure that we are providing the best alternative therapy possible, we wanted to compare outcomes among infants treated with gene therapy and infants receiving partial matched transplants.”

Dr Touzot and his colleagues studied the medical records of 27 children who received either a partially matched HSCT (n=13) or gene therapy (n=14) for SCID-X1 at Necker Children’s Hospital between 1999 and 2013.

The children receiving half-matched transplants and the children receiving gene therapy had been followed for a median of 6 years and 12 years, respectively.

The researchers compared T-cell development among the patients, as well as key clinical outcomes such as infections and hospitalization.

The 14 children in the gene therapy group developed healthy immune cells faster than the 13 children in the half-matched transplant group. In fact, in the first 6 months after therapy, T-cell counts had reached normal values in 78% of the gene therapy patients, compared to 26% of the HSCT patients.

The more rapid growth of the immune system in gene therapy patients was also associated with faster resolution of disseminated BDG infections. These infections resolved in a median of 11 months in the gene therapy group, compared to 25.5 months in the half-matched transplant group.

Gene therapy patients also had fewer infection-related hospitalizations—3 hospitalizations in 3 patients, compared to 15 hospitalizations in 5 patients from the half-matched HSCT group.

“Our analysis suggests that gene therapy can put these incredibly sick children on the road to defending themselves against infection faster than a half-matched transplant,” Dr Touzot said. “These results suggest that, for patients without a fully matched stem cell donor, gene therapy is the next-best approach.” ![]()

Photo by Chad McNeeley

Children with X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID-X1) who undergo gene therapy have fewer infections and hospitalizations than those who receive a hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) from a partially matched donor, according to a study published in Blood.

“Over the last decade, gene therapy has emerged as a viable alternative to a partial matched stem cell transplant for infants with SCID-X1,” said study author Fabien Touzot, MD, PhD, of Necker Children’s Hospital in Paris, France.

“To ensure that we are providing the best alternative therapy possible, we wanted to compare outcomes among infants treated with gene therapy and infants receiving partial matched transplants.”

Dr Touzot and his colleagues studied the medical records of 27 children who received either a partially matched HSCT (n=13) or gene therapy (n=14) for SCID-X1 at Necker Children’s Hospital between 1999 and 2013.

The children receiving half-matched transplants and the children receiving gene therapy had been followed for a median of 6 years and 12 years, respectively.

The researchers compared T-cell development among the patients, as well as key clinical outcomes such as infections and hospitalization.

The 14 children in the gene therapy group developed healthy immune cells faster than the 13 children in the half-matched transplant group. In fact, in the first 6 months after therapy, T-cell counts had reached normal values in 78% of the gene therapy patients, compared to 26% of the HSCT patients.

The more rapid growth of the immune system in gene therapy patients was also associated with faster resolution of disseminated BDG infections. These infections resolved in a median of 11 months in the gene therapy group, compared to 25.5 months in the half-matched transplant group.

Gene therapy patients also had fewer infection-related hospitalizations—3 hospitalizations in 3 patients, compared to 15 hospitalizations in 5 patients from the half-matched HSCT group.

“Our analysis suggests that gene therapy can put these incredibly sick children on the road to defending themselves against infection faster than a half-matched transplant,” Dr Touzot said. “These results suggest that, for patients without a fully matched stem cell donor, gene therapy is the next-best approach.” ![]()

Regulatory monocytes can inhibit GVHD

Image courtesy of PLOS ONE

Researchers believe they have identified a population of monocytes that can protect against graft-vs-host disease (GVHD).

While analyzing peripheral blood stem cells from healthy donors, the team found CD34+ cells with the features of mature monocytes.

They said these cells are transcriptionally distinct from myeloid and monocytic precursors, but they are similar to mature monocytes and endowed with immunosuppressive properties.

Maud D’Aveni, MD, of INSERM in Paris, France, and colleagues described these cells and their abilities in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers found that granulocyte colony-stimulating factor mobilized the monocytes, which strongly suppressed the activation of donor T cells.

In fact, patients who received peripheral blood stem cells containing high levels of the monocytes had lower rates of GVHD.

Experiments in mice revealed that the monocytes release nitric oxide, which triggers reactive T cells to self-destruct and activates a subset of T cells that suppress the immune system to produce immune tolerance.

The researchers said these results indicate that boosting this population of monocytes could help prevent GVHD in transplant recipients. ![]()

Image courtesy of PLOS ONE

Researchers believe they have identified a population of monocytes that can protect against graft-vs-host disease (GVHD).

While analyzing peripheral blood stem cells from healthy donors, the team found CD34+ cells with the features of mature monocytes.

They said these cells are transcriptionally distinct from myeloid and monocytic precursors, but they are similar to mature monocytes and endowed with immunosuppressive properties.

Maud D’Aveni, MD, of INSERM in Paris, France, and colleagues described these cells and their abilities in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers found that granulocyte colony-stimulating factor mobilized the monocytes, which strongly suppressed the activation of donor T cells.

In fact, patients who received peripheral blood stem cells containing high levels of the monocytes had lower rates of GVHD.

Experiments in mice revealed that the monocytes release nitric oxide, which triggers reactive T cells to self-destruct and activates a subset of T cells that suppress the immune system to produce immune tolerance.

The researchers said these results indicate that boosting this population of monocytes could help prevent GVHD in transplant recipients. ![]()

Image courtesy of PLOS ONE

Researchers believe they have identified a population of monocytes that can protect against graft-vs-host disease (GVHD).

While analyzing peripheral blood stem cells from healthy donors, the team found CD34+ cells with the features of mature monocytes.

They said these cells are transcriptionally distinct from myeloid and monocytic precursors, but they are similar to mature monocytes and endowed with immunosuppressive properties.

Maud D’Aveni, MD, of INSERM in Paris, France, and colleagues described these cells and their abilities in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers found that granulocyte colony-stimulating factor mobilized the monocytes, which strongly suppressed the activation of donor T cells.

In fact, patients who received peripheral blood stem cells containing high levels of the monocytes had lower rates of GVHD.

Experiments in mice revealed that the monocytes release nitric oxide, which triggers reactive T cells to self-destruct and activates a subset of T cells that suppress the immune system to produce immune tolerance.

The researchers said these results indicate that boosting this population of monocytes could help prevent GVHD in transplant recipients. ![]()

Protein proves essential for hematopoietic recovery

in the bone marrow

New research suggests the cell survival protein MCL-1, a target for a number of new anticancer agents, is essential for hematopoietic recovery.

Investigators found that reducing MCL-1 levels hindered hematopoietic recovery after chemotherapy and radiotherapy caused extensive destruction of mature blood cells.

Reducing MCL-1 also impaired reconstitution of the bone marrow after hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

“Our previous research has shown that targeting MCL-1 could be used with great success for treating certain blood cancers,” said Alex Delbridge, PhD, of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

“However, we have now shown that MCL-1 is also critical for emergency recovery of the blood cell system after cancer therapy-induced blood cell loss.”

Dr Delbridge and his colleagues reported these findings in Blood.

Experiments in mice revealed that loss of a single MCL-1 allele, which reduced MCL-1 protein levels, greatly compromised the immune system and hindered red blood cell recovery after treatment with 5-fluorouracil, γ-irradiation, or HSCT.

Further investigation showed that the pro-apoptotic gene PUMA plays a key role in this phenomenon, as MCL-1 inhibits PUMA. In mice, knocking out PUMA alleviated—but did not eliminate—the HSC survival defect caused by deletion of both MCL-1 alleles.

“This exquisite dependency on MCL-1 for emergency blood cell production has important implications for potential cancer treatments involving MCL-1 inhibitors,” Dr Delbridge said.

“If MCL-1 inhibitors are to be used in combination with other cancer therapies, careful monitoring of the blood cell system will be needed,” added Stephanie Grabow, PhD, also of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute.

“Our institute colleagues are working to evaluate a potential new drug to treat blood cancers by targeting MCL-1. Our findings suggest that MCL-1 inhibitors and chemotherapeutic drugs should not be used simultaneously.”

Dr Delbridge said this research also offers insights that could help improve HSCT.

“Stem cell transplants can be dangerous because, until the blood cell system is functionally restored, patients are vulnerable to infection,” he said. “Our research suggests that increasing levels of MCL-1 or decreasing the activity of opposing proteins could be a viable strategy for speeding up the regeneration process and reducing the risk of infection after stem cell transplantation.” ![]()

in the bone marrow

New research suggests the cell survival protein MCL-1, a target for a number of new anticancer agents, is essential for hematopoietic recovery.

Investigators found that reducing MCL-1 levels hindered hematopoietic recovery after chemotherapy and radiotherapy caused extensive destruction of mature blood cells.

Reducing MCL-1 also impaired reconstitution of the bone marrow after hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

“Our previous research has shown that targeting MCL-1 could be used with great success for treating certain blood cancers,” said Alex Delbridge, PhD, of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

“However, we have now shown that MCL-1 is also critical for emergency recovery of the blood cell system after cancer therapy-induced blood cell loss.”

Dr Delbridge and his colleagues reported these findings in Blood.

Experiments in mice revealed that loss of a single MCL-1 allele, which reduced MCL-1 protein levels, greatly compromised the immune system and hindered red blood cell recovery after treatment with 5-fluorouracil, γ-irradiation, or HSCT.

Further investigation showed that the pro-apoptotic gene PUMA plays a key role in this phenomenon, as MCL-1 inhibits PUMA. In mice, knocking out PUMA alleviated—but did not eliminate—the HSC survival defect caused by deletion of both MCL-1 alleles.

“This exquisite dependency on MCL-1 for emergency blood cell production has important implications for potential cancer treatments involving MCL-1 inhibitors,” Dr Delbridge said.

“If MCL-1 inhibitors are to be used in combination with other cancer therapies, careful monitoring of the blood cell system will be needed,” added Stephanie Grabow, PhD, also of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute.

“Our institute colleagues are working to evaluate a potential new drug to treat blood cancers by targeting MCL-1. Our findings suggest that MCL-1 inhibitors and chemotherapeutic drugs should not be used simultaneously.”

Dr Delbridge said this research also offers insights that could help improve HSCT.

“Stem cell transplants can be dangerous because, until the blood cell system is functionally restored, patients are vulnerable to infection,” he said. “Our research suggests that increasing levels of MCL-1 or decreasing the activity of opposing proteins could be a viable strategy for speeding up the regeneration process and reducing the risk of infection after stem cell transplantation.” ![]()

in the bone marrow

New research suggests the cell survival protein MCL-1, a target for a number of new anticancer agents, is essential for hematopoietic recovery.

Investigators found that reducing MCL-1 levels hindered hematopoietic recovery after chemotherapy and radiotherapy caused extensive destruction of mature blood cells.

Reducing MCL-1 also impaired reconstitution of the bone marrow after hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

“Our previous research has shown that targeting MCL-1 could be used with great success for treating certain blood cancers,” said Alex Delbridge, PhD, of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

“However, we have now shown that MCL-1 is also critical for emergency recovery of the blood cell system after cancer therapy-induced blood cell loss.”

Dr Delbridge and his colleagues reported these findings in Blood.

Experiments in mice revealed that loss of a single MCL-1 allele, which reduced MCL-1 protein levels, greatly compromised the immune system and hindered red blood cell recovery after treatment with 5-fluorouracil, γ-irradiation, or HSCT.

Further investigation showed that the pro-apoptotic gene PUMA plays a key role in this phenomenon, as MCL-1 inhibits PUMA. In mice, knocking out PUMA alleviated—but did not eliminate—the HSC survival defect caused by deletion of both MCL-1 alleles.

“This exquisite dependency on MCL-1 for emergency blood cell production has important implications for potential cancer treatments involving MCL-1 inhibitors,” Dr Delbridge said.

“If MCL-1 inhibitors are to be used in combination with other cancer therapies, careful monitoring of the blood cell system will be needed,” added Stephanie Grabow, PhD, also of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute.

“Our institute colleagues are working to evaluate a potential new drug to treat blood cancers by targeting MCL-1. Our findings suggest that MCL-1 inhibitors and chemotherapeutic drugs should not be used simultaneously.”

Dr Delbridge said this research also offers insights that could help improve HSCT.

“Stem cell transplants can be dangerous because, until the blood cell system is functionally restored, patients are vulnerable to infection,” he said. “Our research suggests that increasing levels of MCL-1 or decreasing the activity of opposing proteins could be a viable strategy for speeding up the regeneration process and reducing the risk of infection after stem cell transplantation.” ![]()

Enzyme keeps HSCs functional to prevent anemia

Preclinical research suggests an enzyme found in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) is key to maintaining periods of inactivity, thereby decreasing the odds that HSCs will divide too often and acquire mutations or cell damage.

Experiments showed that animals lacking this enzyme, inositol trisphosphate 3-kinase B (Itpkb), experience dangerous HSC activation and ultimately succumb to lethal anemia.

“These HSCs remain active too long and then disappear,” said Karsten Sauer, PhD, of The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California.

“As a consequence, the mice lose their red blood cells and die.”

With this new understanding of Itpkb, Dr Sauer and his colleagues believe they are closer to improving therapies for diseases such as bone marrow failure syndrome, anemia, leukemia, and lymphoma.

The team described their research in Blood.

The group set out to investigate the mechanisms that activate and deactivate HSCs. They focused on Itpkb because it is produced in HSCs, and the enzyme is known to dampen activating signaling in other cells.

“We hypothesized that Itpkb might do the same in HSCs to keep them at rest,” Dr Sauer said. “Moreover, Itpkb is an enzyme whose function can be controlled by small molecules. This might facilitate drug development if our hypothesis were true.”

The researchers started with a strain of mice that lacked the gene to produce Itpkb. As expected, these mice developed hyperactive HSCs. Eventually, the mutant HSCs exhausted themselves and stopped producing progenitor cells, so the mice developed severe anemia and died.

Dr Sauer and his colleagues linked the abnormal behavior of the mutant HSCs to a chain of events at the molecular level.

Itpkb’s job is to attach phosphates to molecules called inositols, which then send messages to other parts of the cell. The researchers found that Itpkb can turn one inositol, IP3, into another inositol known as IP4.

This is significant because IP4 controls cell proliferation, cellular metabolism, and aspects of the immune system. The study showed that IP4 also protects HSCs by dampening PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling.

To confirm this finding, the researchers treated the animals with the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin. The drug halted the abnormal signaling process and prevented the excessive division of HSCs lacking Itpkb. This supported the notion that Itpkb maintains HSCs’ quiescence by dampening PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling.

Dr Sauer said future research in his lab will focus on studying whether Itpkb has a similar function in human HSCs.

“A major question is whether we can translate our findings into innovative therapies,” he said. “If we can show that Itpkb also keeps human HSCs healthy, this could open avenues to target Itpkb to improve HSC function in bone marrow failure syndromes and immunodeficiencies or to increase the success rates of HSC transplantation therapies for leukemias and lymphomas.” ![]()

Preclinical research suggests an enzyme found in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) is key to maintaining periods of inactivity, thereby decreasing the odds that HSCs will divide too often and acquire mutations or cell damage.

Experiments showed that animals lacking this enzyme, inositol trisphosphate 3-kinase B (Itpkb), experience dangerous HSC activation and ultimately succumb to lethal anemia.

“These HSCs remain active too long and then disappear,” said Karsten Sauer, PhD, of The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California.

“As a consequence, the mice lose their red blood cells and die.”

With this new understanding of Itpkb, Dr Sauer and his colleagues believe they are closer to improving therapies for diseases such as bone marrow failure syndrome, anemia, leukemia, and lymphoma.

The team described their research in Blood.

The group set out to investigate the mechanisms that activate and deactivate HSCs. They focused on Itpkb because it is produced in HSCs, and the enzyme is known to dampen activating signaling in other cells.

“We hypothesized that Itpkb might do the same in HSCs to keep them at rest,” Dr Sauer said. “Moreover, Itpkb is an enzyme whose function can be controlled by small molecules. This might facilitate drug development if our hypothesis were true.”

The researchers started with a strain of mice that lacked the gene to produce Itpkb. As expected, these mice developed hyperactive HSCs. Eventually, the mutant HSCs exhausted themselves and stopped producing progenitor cells, so the mice developed severe anemia and died.

Dr Sauer and his colleagues linked the abnormal behavior of the mutant HSCs to a chain of events at the molecular level.

Itpkb’s job is to attach phosphates to molecules called inositols, which then send messages to other parts of the cell. The researchers found that Itpkb can turn one inositol, IP3, into another inositol known as IP4.

This is significant because IP4 controls cell proliferation, cellular metabolism, and aspects of the immune system. The study showed that IP4 also protects HSCs by dampening PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling.

To confirm this finding, the researchers treated the animals with the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin. The drug halted the abnormal signaling process and prevented the excessive division of HSCs lacking Itpkb. This supported the notion that Itpkb maintains HSCs’ quiescence by dampening PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling.

Dr Sauer said future research in his lab will focus on studying whether Itpkb has a similar function in human HSCs.

“A major question is whether we can translate our findings into innovative therapies,” he said. “If we can show that Itpkb also keeps human HSCs healthy, this could open avenues to target Itpkb to improve HSC function in bone marrow failure syndromes and immunodeficiencies or to increase the success rates of HSC transplantation therapies for leukemias and lymphomas.” ![]()

Preclinical research suggests an enzyme found in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) is key to maintaining periods of inactivity, thereby decreasing the odds that HSCs will divide too often and acquire mutations or cell damage.

Experiments showed that animals lacking this enzyme, inositol trisphosphate 3-kinase B (Itpkb), experience dangerous HSC activation and ultimately succumb to lethal anemia.

“These HSCs remain active too long and then disappear,” said Karsten Sauer, PhD, of The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California.

“As a consequence, the mice lose their red blood cells and die.”

With this new understanding of Itpkb, Dr Sauer and his colleagues believe they are closer to improving therapies for diseases such as bone marrow failure syndrome, anemia, leukemia, and lymphoma.

The team described their research in Blood.

The group set out to investigate the mechanisms that activate and deactivate HSCs. They focused on Itpkb because it is produced in HSCs, and the enzyme is known to dampen activating signaling in other cells.

“We hypothesized that Itpkb might do the same in HSCs to keep them at rest,” Dr Sauer said. “Moreover, Itpkb is an enzyme whose function can be controlled by small molecules. This might facilitate drug development if our hypothesis were true.”

The researchers started with a strain of mice that lacked the gene to produce Itpkb. As expected, these mice developed hyperactive HSCs. Eventually, the mutant HSCs exhausted themselves and stopped producing progenitor cells, so the mice developed severe anemia and died.

Dr Sauer and his colleagues linked the abnormal behavior of the mutant HSCs to a chain of events at the molecular level.

Itpkb’s job is to attach phosphates to molecules called inositols, which then send messages to other parts of the cell. The researchers found that Itpkb can turn one inositol, IP3, into another inositol known as IP4.

This is significant because IP4 controls cell proliferation, cellular metabolism, and aspects of the immune system. The study showed that IP4 also protects HSCs by dampening PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling.

To confirm this finding, the researchers treated the animals with the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin. The drug halted the abnormal signaling process and prevented the excessive division of HSCs lacking Itpkb. This supported the notion that Itpkb maintains HSCs’ quiescence by dampening PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling.

Dr Sauer said future research in his lab will focus on studying whether Itpkb has a similar function in human HSCs.

“A major question is whether we can translate our findings into innovative therapies,” he said. “If we can show that Itpkb also keeps human HSCs healthy, this could open avenues to target Itpkb to improve HSC function in bone marrow failure syndromes and immunodeficiencies or to increase the success rates of HSC transplantation therapies for leukemias and lymphomas.”

Drug granted orphan designation for GVHD

The European Commission has granted orphan drug designation for intravenous (IV) alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) to treat graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

AAT is a protein derived from human plasma that has demonstrated immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, tissue-protective, antimicrobial, and anti-apoptotic properties.

AAT may attenuate inflammation by lowering levels of pro-inflammatory mediators such as cytokines, chemokines, and proteases associated with GVHD.

The European Commission granted IV AAT orphan designation based on preliminary clinical and preclinical research.

Orphan designation is granted to a medicine intended to treat a rare condition occurring in not more than 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union. The designation allows the drug’s maker to benefit from incentives such as a 10-year period of market exclusivity, reduced regulatory fees, and protocol assistance from the European Medicines Agency.

IV AAT also has orphan designation to treat GVHD in the US.

Studies of AAT

AAT is being investigated in a phase 1/2 study involving 24 patients with GVHD who had an inadequate response to steroid treatment. The patients are enrolled in 4 dose cohorts, in which they receive up to 8 doses of AAT.

Interim results from this study were presented at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 3927). Preliminary results indicated that continuous administration of AAT as therapy for steroid-resistant gut GVHD is feasible in the subject population.

Following AAT administration, the researchers observed a decrease in diarrhea, a decrease in intestinal AAT loss, and improvement in endoscopic evaluation. In addition, AAT administration suppressed serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and interfered with GVHD biomarkers.

Investigators have also published research on AAT in Blood. This study suggested that AAT has a protective effect against GVHD and enhances graft-vs-leukemia effects.

Kamada Ltd., the company developing IV AAT, plans to begin a phase 3 trial of the treatment in 2016 and get the product to market in 2019 or later.

The European Commission has granted orphan drug designation for intravenous (IV) alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) to treat graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

AAT is a protein derived from human plasma that has demonstrated immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, tissue-protective, antimicrobial, and anti-apoptotic properties.

AAT may attenuate inflammation by lowering levels of pro-inflammatory mediators such as cytokines, chemokines, and proteases associated with GVHD.

The European Commission granted IV AAT orphan designation based on preliminary clinical and preclinical research.

Orphan designation is granted to a medicine intended to treat a rare condition occurring in not more than 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union. The designation allows the drug’s maker to benefit from incentives such as a 10-year period of market exclusivity, reduced regulatory fees, and protocol assistance from the European Medicines Agency.

IV AAT also has orphan designation to treat GVHD in the US.

Studies of AAT

AAT is being investigated in a phase 1/2 study involving 24 patients with GVHD who had an inadequate response to steroid treatment. The patients are enrolled in 4 dose cohorts, in which they receive up to 8 doses of AAT.

Interim results from this study were presented at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 3927). Preliminary results indicated that continuous administration of AAT as therapy for steroid-resistant gut GVHD is feasible in the subject population.

Following AAT administration, the researchers observed a decrease in diarrhea, a decrease in intestinal AAT loss, and improvement in endoscopic evaluation. In addition, AAT administration suppressed serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and interfered with GVHD biomarkers.

Investigators have also published research on AAT in Blood. This study suggested that AAT has a protective effect against GVHD and enhances graft-vs-leukemia effects.

Kamada Ltd., the company developing IV AAT, plans to begin a phase 3 trial of the treatment in 2016 and get the product to market in 2019 or later.

The European Commission has granted orphan drug designation for intravenous (IV) alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) to treat graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

AAT is a protein derived from human plasma that has demonstrated immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, tissue-protective, antimicrobial, and anti-apoptotic properties.

AAT may attenuate inflammation by lowering levels of pro-inflammatory mediators such as cytokines, chemokines, and proteases associated with GVHD.

The European Commission granted IV AAT orphan designation based on preliminary clinical and preclinical research.

Orphan designation is granted to a medicine intended to treat a rare condition occurring in not more than 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union. The designation allows the drug’s maker to benefit from incentives such as a 10-year period of market exclusivity, reduced regulatory fees, and protocol assistance from the European Medicines Agency.

IV AAT also has orphan designation to treat GVHD in the US.

Studies of AAT

AAT is being investigated in a phase 1/2 study involving 24 patients with GVHD who had an inadequate response to steroid treatment. The patients are enrolled in 4 dose cohorts, in which they receive up to 8 doses of AAT.

Interim results from this study were presented at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 3927). Preliminary results indicated that continuous administration of AAT as therapy for steroid-resistant gut GVHD is feasible in the subject population.

Following AAT administration, the researchers observed a decrease in diarrhea, a decrease in intestinal AAT loss, and improvement in endoscopic evaluation. In addition, AAT administration suppressed serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and interfered with GVHD biomarkers.

Investigators have also published research on AAT in Blood. This study suggested that AAT has a protective effect against GVHD and enhances graft-vs-leukemia effects.

Kamada Ltd., the company developing IV AAT, plans to begin a phase 3 trial of the treatment in 2016 and get the product to market in 2019 or later.

Drug produces ‘dramatic’ results in HL

The anti-CD30 antibody-drug conjugate brentuximab vedotin can prolong progression-free survival (PFS) in Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) patients who have undergone autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), results of the phase 3 AETHERA trial have shown.

The median PFS for patients who received brentuximab vedotin immediately after ASCT was nearly twice that of patients who received placebo—42.9 months and 24.1 months, respectively.

“No medication available today has had such dramatic results in patients with hard-to-treat Hodgkin lymphoma,” said Craig Moskowitz, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, New York.

Dr Moskowitz and his colleagues detailed these results in The Lancet. The results were previously presented at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting. The research was funded by Seattle Genetics, Inc., and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, the companies developing brentuximab vedotin.

The AETHERA study included 329 HL patients age 18 or older who were thought to be at high risk of relapse or progression after ASCT. Patients were randomized to receive placebo or 16 cycles of brentuximab vedotin once every 3 weeks.

After a median observation time of 30 months (range, 0-50 months), the rate of PFS was significantly higher in the brentuximab vedotin arm than the placebo arm. The hazard ratio was 0.57 (P=0.0013), according to an independent review group.

The estimated 2-year PFS was 63% in the brentuximab vedotin arm and 51% in the placebo arm, according to the independent review group. But according to investigators, the estimated 2-year PFS was 65% in the brentuximab vedotin arm and 45% in the placebo arm.

“Nearly all of these patients who are progression-free at 2 years are likely to be cured, since relapse 2 years after a transplant is unlikely,” Dr Moskowitz noted.

An interim analysis revealed no significant difference between the treatment arms with regard to overall survival.

The researchers said brentuximab vedotin was generally well-tolerated. The most common adverse events were peripheral neuropathy—occurring in 67% of brentuximab vedotin-treated patients and 13% of placebo-treated patients—and neutropenia—occurring in 35% and 12%, respectively.

In all, 53 patients died, 17% of those in the brentuximab vedotin arm and 16% of those in the placebo arm. The proportion of patients who died from disease-related illness was the same in both arms—11%.

“The bottom line is that brentuximab vedotin is a very effective drug in poor-risk Hodgkin lymphoma, and it spares patients from the harmful effects of further traditional chemotherapy by breaking down inside the cell, resulting in less toxicity,” Dr Moskowitz said.

Writing in a linked comment article, Andreas Engert, MD, of the University Hospital of Cologne in Germany, discussed how best to define which patients are at high risk of relapse and should receive brentuximab vedotin.

“AETHERA is a positive study establishing a promising new treatment approach for patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma at high risk for relapse,” he wrote. “However, with a progression-free survival of about 50% at 24 months in the placebo group, whether this patient population is indeed high-risk could be debated.”

“An international consortium is currently reassessing the effect of risk factors in patients with relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma to define a high-risk patient population in need of consolidation treatment. We look forward to a better definition of patients with relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma who should receive consolidation treatment with brentuximab vedotin.”

The anti-CD30 antibody-drug conjugate brentuximab vedotin can prolong progression-free survival (PFS) in Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) patients who have undergone autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), results of the phase 3 AETHERA trial have shown.

The median PFS for patients who received brentuximab vedotin immediately after ASCT was nearly twice that of patients who received placebo—42.9 months and 24.1 months, respectively.

“No medication available today has had such dramatic results in patients with hard-to-treat Hodgkin lymphoma,” said Craig Moskowitz, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, New York.

Dr Moskowitz and his colleagues detailed these results in The Lancet. The results were previously presented at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting. The research was funded by Seattle Genetics, Inc., and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, the companies developing brentuximab vedotin.

The AETHERA study included 329 HL patients age 18 or older who were thought to be at high risk of relapse or progression after ASCT. Patients were randomized to receive placebo or 16 cycles of brentuximab vedotin once every 3 weeks.

After a median observation time of 30 months (range, 0-50 months), the rate of PFS was significantly higher in the brentuximab vedotin arm than the placebo arm. The hazard ratio was 0.57 (P=0.0013), according to an independent review group.

The estimated 2-year PFS was 63% in the brentuximab vedotin arm and 51% in the placebo arm, according to the independent review group. But according to investigators, the estimated 2-year PFS was 65% in the brentuximab vedotin arm and 45% in the placebo arm.

“Nearly all of these patients who are progression-free at 2 years are likely to be cured, since relapse 2 years after a transplant is unlikely,” Dr Moskowitz noted.

An interim analysis revealed no significant difference between the treatment arms with regard to overall survival.

The researchers said brentuximab vedotin was generally well-tolerated. The most common adverse events were peripheral neuropathy—occurring in 67% of brentuximab vedotin-treated patients and 13% of placebo-treated patients—and neutropenia—occurring in 35% and 12%, respectively.

In all, 53 patients died, 17% of those in the brentuximab vedotin arm and 16% of those in the placebo arm. The proportion of patients who died from disease-related illness was the same in both arms—11%.

“The bottom line is that brentuximab vedotin is a very effective drug in poor-risk Hodgkin lymphoma, and it spares patients from the harmful effects of further traditional chemotherapy by breaking down inside the cell, resulting in less toxicity,” Dr Moskowitz said.

Writing in a linked comment article, Andreas Engert, MD, of the University Hospital of Cologne in Germany, discussed how best to define which patients are at high risk of relapse and should receive brentuximab vedotin.

“AETHERA is a positive study establishing a promising new treatment approach for patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma at high risk for relapse,” he wrote. “However, with a progression-free survival of about 50% at 24 months in the placebo group, whether this patient population is indeed high-risk could be debated.”

“An international consortium is currently reassessing the effect of risk factors in patients with relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma to define a high-risk patient population in need of consolidation treatment. We look forward to a better definition of patients with relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma who should receive consolidation treatment with brentuximab vedotin.”

The anti-CD30 antibody-drug conjugate brentuximab vedotin can prolong progression-free survival (PFS) in Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) patients who have undergone autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), results of the phase 3 AETHERA trial have shown.

The median PFS for patients who received brentuximab vedotin immediately after ASCT was nearly twice that of patients who received placebo—42.9 months and 24.1 months, respectively.

“No medication available today has had such dramatic results in patients with hard-to-treat Hodgkin lymphoma,” said Craig Moskowitz, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, New York.

Dr Moskowitz and his colleagues detailed these results in The Lancet. The results were previously presented at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting. The research was funded by Seattle Genetics, Inc., and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, the companies developing brentuximab vedotin.

The AETHERA study included 329 HL patients age 18 or older who were thought to be at high risk of relapse or progression after ASCT. Patients were randomized to receive placebo or 16 cycles of brentuximab vedotin once every 3 weeks.

After a median observation time of 30 months (range, 0-50 months), the rate of PFS was significantly higher in the brentuximab vedotin arm than the placebo arm. The hazard ratio was 0.57 (P=0.0013), according to an independent review group.

The estimated 2-year PFS was 63% in the brentuximab vedotin arm and 51% in the placebo arm, according to the independent review group. But according to investigators, the estimated 2-year PFS was 65% in the brentuximab vedotin arm and 45% in the placebo arm.

“Nearly all of these patients who are progression-free at 2 years are likely to be cured, since relapse 2 years after a transplant is unlikely,” Dr Moskowitz noted.

An interim analysis revealed no significant difference between the treatment arms with regard to overall survival.

The researchers said brentuximab vedotin was generally well-tolerated. The most common adverse events were peripheral neuropathy—occurring in 67% of brentuximab vedotin-treated patients and 13% of placebo-treated patients—and neutropenia—occurring in 35% and 12%, respectively.

In all, 53 patients died, 17% of those in the brentuximab vedotin arm and 16% of those in the placebo arm. The proportion of patients who died from disease-related illness was the same in both arms—11%.

“The bottom line is that brentuximab vedotin is a very effective drug in poor-risk Hodgkin lymphoma, and it spares patients from the harmful effects of further traditional chemotherapy by breaking down inside the cell, resulting in less toxicity,” Dr Moskowitz said.

Writing in a linked comment article, Andreas Engert, MD, of the University Hospital of Cologne in Germany, discussed how best to define which patients are at high risk of relapse and should receive brentuximab vedotin.

“AETHERA is a positive study establishing a promising new treatment approach for patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma at high risk for relapse,” he wrote. “However, with a progression-free survival of about 50% at 24 months in the placebo group, whether this patient population is indeed high-risk could be debated.”

“An international consortium is currently reassessing the effect of risk factors in patients with relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma to define a high-risk patient population in need of consolidation treatment. We look forward to a better definition of patients with relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma who should receive consolidation treatment with brentuximab vedotin.”

News reports on stem cell research often unrealistic, team says

Media coverage of translational stem cell research might generate unrealistic expectations, according to a pair of researchers.

The team analyzed reports on stem cell research published in major daily newspapers in Canada, the US, and the UK between 2010 and 2013.

They found that most reports were highly optimistic about the future of stem cell therapies and indicated that therapies would be available for clinical use within 5 to 10 years or sooner.

The researchers said that, as spokespeople, scientists need to be mindful of harnessing public expectations.

“As the dominant voice in respect to timelines for stem cell therapies, the scientists quoted in these stories need to be more aware of the importance of communicating realistic timelines to the press,“ said Kalina Kamenova, PhD, of the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada.

Dr Kamenova conducted this research with Timothy Caulfield, also of the University of Alberta, and the pair disclosed their results in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers examined 307 news reports covering translational research on stem cells, including human embryonic stem cells (21.5%), induced pluripotent stem cells (12.1%), cord blood stem cells (2.9%), other tissue-specific stem cells such as bone marrow or mesenchymal stem cells (23.8%), multiple types of stem cells (18.9%), and stem cells of an unspecified type (20.8%).

The team assessed perspectives on the future of stem cell therapies and found that 57.7% of news reports were optimistic, 10.4% were pessimistic, and 31.9% were neutral.

In addition, 69% of all news stories citing timelines predicted that stem cell therapies would be available within 5 to 10 years or sooner.

“The approval process for new treatments is long and complicated, and only a few of all drugs that enter preclinical testing are approved for human clinical trials,” Dr Kamenova pointed out. “It takes, on average, 12 years to get a new drug from the lab to the market and [an] additional 11 to 14 years of post-market surveillance.”

“Our findings showed that many scientists have often provided, either by implication or direct quotes, authoritative statements regarding unrealistic timelines for stem cell therapies,” Caulfield added.

“[M]edia hype can foster unrealistic public expectations about clinical translation and increased patient demand for unproven stem cell therapies. Care needs to be taken by the media and the research community so that advances in research and therapy are portrayed in a realistic manner.”

Media coverage of translational stem cell research might generate unrealistic expectations, according to a pair of researchers.

The team analyzed reports on stem cell research published in major daily newspapers in Canada, the US, and the UK between 2010 and 2013.

They found that most reports were highly optimistic about the future of stem cell therapies and indicated that therapies would be available for clinical use within 5 to 10 years or sooner.

The researchers said that, as spokespeople, scientists need to be mindful of harnessing public expectations.

“As the dominant voice in respect to timelines for stem cell therapies, the scientists quoted in these stories need to be more aware of the importance of communicating realistic timelines to the press,“ said Kalina Kamenova, PhD, of the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada.

Dr Kamenova conducted this research with Timothy Caulfield, also of the University of Alberta, and the pair disclosed their results in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers examined 307 news reports covering translational research on stem cells, including human embryonic stem cells (21.5%), induced pluripotent stem cells (12.1%), cord blood stem cells (2.9%), other tissue-specific stem cells such as bone marrow or mesenchymal stem cells (23.8%), multiple types of stem cells (18.9%), and stem cells of an unspecified type (20.8%).

The team assessed perspectives on the future of stem cell therapies and found that 57.7% of news reports were optimistic, 10.4% were pessimistic, and 31.9% were neutral.

In addition, 69% of all news stories citing timelines predicted that stem cell therapies would be available within 5 to 10 years or sooner.

“The approval process for new treatments is long and complicated, and only a few of all drugs that enter preclinical testing are approved for human clinical trials,” Dr Kamenova pointed out. “It takes, on average, 12 years to get a new drug from the lab to the market and [an] additional 11 to 14 years of post-market surveillance.”

“Our findings showed that many scientists have often provided, either by implication or direct quotes, authoritative statements regarding unrealistic timelines for stem cell therapies,” Caulfield added.

“[M]edia hype can foster unrealistic public expectations about clinical translation and increased patient demand for unproven stem cell therapies. Care needs to be taken by the media and the research community so that advances in research and therapy are portrayed in a realistic manner.”

Media coverage of translational stem cell research might generate unrealistic expectations, according to a pair of researchers.

The team analyzed reports on stem cell research published in major daily newspapers in Canada, the US, and the UK between 2010 and 2013.

They found that most reports were highly optimistic about the future of stem cell therapies and indicated that therapies would be available for clinical use within 5 to 10 years or sooner.

The researchers said that, as spokespeople, scientists need to be mindful of harnessing public expectations.

“As the dominant voice in respect to timelines for stem cell therapies, the scientists quoted in these stories need to be more aware of the importance of communicating realistic timelines to the press,“ said Kalina Kamenova, PhD, of the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada.

Dr Kamenova conducted this research with Timothy Caulfield, also of the University of Alberta, and the pair disclosed their results in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers examined 307 news reports covering translational research on stem cells, including human embryonic stem cells (21.5%), induced pluripotent stem cells (12.1%), cord blood stem cells (2.9%), other tissue-specific stem cells such as bone marrow or mesenchymal stem cells (23.8%), multiple types of stem cells (18.9%), and stem cells of an unspecified type (20.8%).

The team assessed perspectives on the future of stem cell therapies and found that 57.7% of news reports were optimistic, 10.4% were pessimistic, and 31.9% were neutral.