User login

The Gamer Who Became a GI Hospitalist and Dedicated Endoscopist

Reflecting on his career in gastroenterology, Andy Tau, MD, (@DrBloodandGuts on X) claims the discipline chose him, in many ways.

“I love gaming, which my mom said would never pay off. Then one day she nearly died from a peptic ulcer, and endoscopy saved her,” said Dr. Tau, a GI hospitalist who practices with Austin Gastroenterology in Austin, Texas. One of his specialties is endoscopic hemostasis.

Endoscopy functions similarly to a game because the interface between the operator and the patient is a controller and a video screen, he explained. “Movements in my hands translate directly onto the screen. Obviously, endoscopy is serious business, but the tactile feel was very familiar and satisfying to me.”

Advocating for the GI hospitalist and the versatile role they play in hospital medicine, is another passion of his. “The dedicated GI hospitalist indirectly improves the efficiency of an outpatient practice, while directly improving inpatient outcomes, collegiality, and even one’s own skills as an endoscopist,” Dr. Tau wrote in an opinion piece in GI & Hepatology News .

He expounded more on this topic and others in an interview, recalling what he learned from one mentor about maintaining a sense of humor at the bedside.

Q: You’ve said that GI hospitalists are the future of patient care. Can you explain why you feel this way?

Dr. Tau: From a quality perspective, even though it’s hard to put into one word, the care of acute GI pathology and endoscopy can be seen as a specialty in and of itself. These skills include hemostasis, enteral access, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG), balloon-assisted enteroscopy, luminal stenting, advanced tissue closure, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. The greater availability of a GI hospitalist, as opposed to an outpatient GI doctor rounding at the ends of days, likely shortens admissions and improves the logistics of scheduling inpatient cases.

From a financial perspective, the landscape of GI practice is changing because of GI physician shortages relative to increased demand for outpatient procedures. Namely, the outpatient gastroenterologists simply have too much on their plate and inefficiencies abound when they have to juggle inpatient and outpatient work. Thus, two tracks are forming, especially in large busy hospitals. This is the same evolution of the pure outpatient internist and inpatient internist 20 years ago.

Q: What attributes does a GI hospitalist bring to the table?

Dr. Tau: A GI hospitalist is one who can multitask through interruptions, manage end-of-life issues, craves therapeutic endoscopy (even if that’s hemostasis), and can keep more erratic hours based on the number of consults that come in. She/he tends to want immediate gratification and doesn’t mind the lack of continuity of care. Lastly, the GI hospitalist has to be brave and yet careful as the patients are sicker and thus complications may be higher and certainly less well tolerated.

Q: Are there enough of them going into practice right now?

Dr. Tau: Not really! The demand seems to outstrip supply based on what I see. There is a definite financial lure as the market rate for them rises (because more GIs are leaving the hospital for pure outpatient practice), but burnout can be an issue. Interestingly, fellows are typically highly trained and familiar with inpatient work, but once in practice, most choose the outpatient track. I think it’s a combination of work-life balance, inefficiency of inpatient endoscopy, and perhaps the strain of daily, erratic consultation.

Q: You received the 2021 Travis County Medical Society (TCMS) Young Physician of the Year. What achievements led to this honor?

Dr. Tau: I am not sure I am deserving of that award, but I think it was related to personal risk and some long hours as a GI hospitalist during the COVID pandemic. I may have the unfortunate distinction of performing more procedures on COVID patients than any other physician in the city. My hospital was the largest COVID-designated site in the city. There were countless PEG tubes in COVID survivors and a lot of bleeders for some reason. A critical care physician on the front lines and health director of the city of Austin received Physician of the Year, deservedly.

Q: What teacher or mentor had the greatest impact on you?

Dr. Tau: David Y. Graham, MD, MACG, got me into GI as a medical student and taught me to never tolerate any loose ends when it came to patient care as a resident. He trained me at every level — from medical school, residency, and through my fellowship. His advice is often delivered sly and dry, but his humor-laden truths continue to ring true throughout my life. One story: my whole family tested positive for Helicobacter pylori after my mother survived peptic ulcer hemorrhage. I was the only one who tested negative! I asked Dr Graham about it and he quipped, “You’re lucky! It’s because your mother didn’t love (and kiss) you as much!”

Even to this moment I laugh about that. I share that with my patients when they ask about how they contracted H. pylori.

Lightning Round

Favorite junk food?

McDonalds fries

Favorite movie genre?

Psychological thriller

Cat person or dog person?

Dog

What was your favorite Halloween costume?

Ninja turtle

Favorite sport:

Football (played in college)

Introvert or extrovert?

Extrovert unless sleep deprived.

Favorite holiday:

Thanksgiving

The book you read over and over:

Swiss Family Robinson

Favorite travel destination:

Hawaii

Optimist or pessimist?

A happy pessimist.

Reflecting on his career in gastroenterology, Andy Tau, MD, (@DrBloodandGuts on X) claims the discipline chose him, in many ways.

“I love gaming, which my mom said would never pay off. Then one day she nearly died from a peptic ulcer, and endoscopy saved her,” said Dr. Tau, a GI hospitalist who practices with Austin Gastroenterology in Austin, Texas. One of his specialties is endoscopic hemostasis.

Endoscopy functions similarly to a game because the interface between the operator and the patient is a controller and a video screen, he explained. “Movements in my hands translate directly onto the screen. Obviously, endoscopy is serious business, but the tactile feel was very familiar and satisfying to me.”

Advocating for the GI hospitalist and the versatile role they play in hospital medicine, is another passion of his. “The dedicated GI hospitalist indirectly improves the efficiency of an outpatient practice, while directly improving inpatient outcomes, collegiality, and even one’s own skills as an endoscopist,” Dr. Tau wrote in an opinion piece in GI & Hepatology News .

He expounded more on this topic and others in an interview, recalling what he learned from one mentor about maintaining a sense of humor at the bedside.

Q: You’ve said that GI hospitalists are the future of patient care. Can you explain why you feel this way?

Dr. Tau: From a quality perspective, even though it’s hard to put into one word, the care of acute GI pathology and endoscopy can be seen as a specialty in and of itself. These skills include hemostasis, enteral access, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG), balloon-assisted enteroscopy, luminal stenting, advanced tissue closure, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. The greater availability of a GI hospitalist, as opposed to an outpatient GI doctor rounding at the ends of days, likely shortens admissions and improves the logistics of scheduling inpatient cases.

From a financial perspective, the landscape of GI practice is changing because of GI physician shortages relative to increased demand for outpatient procedures. Namely, the outpatient gastroenterologists simply have too much on their plate and inefficiencies abound when they have to juggle inpatient and outpatient work. Thus, two tracks are forming, especially in large busy hospitals. This is the same evolution of the pure outpatient internist and inpatient internist 20 years ago.

Q: What attributes does a GI hospitalist bring to the table?

Dr. Tau: A GI hospitalist is one who can multitask through interruptions, manage end-of-life issues, craves therapeutic endoscopy (even if that’s hemostasis), and can keep more erratic hours based on the number of consults that come in. She/he tends to want immediate gratification and doesn’t mind the lack of continuity of care. Lastly, the GI hospitalist has to be brave and yet careful as the patients are sicker and thus complications may be higher and certainly less well tolerated.

Q: Are there enough of them going into practice right now?

Dr. Tau: Not really! The demand seems to outstrip supply based on what I see. There is a definite financial lure as the market rate for them rises (because more GIs are leaving the hospital for pure outpatient practice), but burnout can be an issue. Interestingly, fellows are typically highly trained and familiar with inpatient work, but once in practice, most choose the outpatient track. I think it’s a combination of work-life balance, inefficiency of inpatient endoscopy, and perhaps the strain of daily, erratic consultation.

Q: You received the 2021 Travis County Medical Society (TCMS) Young Physician of the Year. What achievements led to this honor?

Dr. Tau: I am not sure I am deserving of that award, but I think it was related to personal risk and some long hours as a GI hospitalist during the COVID pandemic. I may have the unfortunate distinction of performing more procedures on COVID patients than any other physician in the city. My hospital was the largest COVID-designated site in the city. There were countless PEG tubes in COVID survivors and a lot of bleeders for some reason. A critical care physician on the front lines and health director of the city of Austin received Physician of the Year, deservedly.

Q: What teacher or mentor had the greatest impact on you?

Dr. Tau: David Y. Graham, MD, MACG, got me into GI as a medical student and taught me to never tolerate any loose ends when it came to patient care as a resident. He trained me at every level — from medical school, residency, and through my fellowship. His advice is often delivered sly and dry, but his humor-laden truths continue to ring true throughout my life. One story: my whole family tested positive for Helicobacter pylori after my mother survived peptic ulcer hemorrhage. I was the only one who tested negative! I asked Dr Graham about it and he quipped, “You’re lucky! It’s because your mother didn’t love (and kiss) you as much!”

Even to this moment I laugh about that. I share that with my patients when they ask about how they contracted H. pylori.

Lightning Round

Favorite junk food?

McDonalds fries

Favorite movie genre?

Psychological thriller

Cat person or dog person?

Dog

What was your favorite Halloween costume?

Ninja turtle

Favorite sport:

Football (played in college)

Introvert or extrovert?

Extrovert unless sleep deprived.

Favorite holiday:

Thanksgiving

The book you read over and over:

Swiss Family Robinson

Favorite travel destination:

Hawaii

Optimist or pessimist?

A happy pessimist.

Reflecting on his career in gastroenterology, Andy Tau, MD, (@DrBloodandGuts on X) claims the discipline chose him, in many ways.

“I love gaming, which my mom said would never pay off. Then one day she nearly died from a peptic ulcer, and endoscopy saved her,” said Dr. Tau, a GI hospitalist who practices with Austin Gastroenterology in Austin, Texas. One of his specialties is endoscopic hemostasis.

Endoscopy functions similarly to a game because the interface between the operator and the patient is a controller and a video screen, he explained. “Movements in my hands translate directly onto the screen. Obviously, endoscopy is serious business, but the tactile feel was very familiar and satisfying to me.”

Advocating for the GI hospitalist and the versatile role they play in hospital medicine, is another passion of his. “The dedicated GI hospitalist indirectly improves the efficiency of an outpatient practice, while directly improving inpatient outcomes, collegiality, and even one’s own skills as an endoscopist,” Dr. Tau wrote in an opinion piece in GI & Hepatology News .

He expounded more on this topic and others in an interview, recalling what he learned from one mentor about maintaining a sense of humor at the bedside.

Q: You’ve said that GI hospitalists are the future of patient care. Can you explain why you feel this way?

Dr. Tau: From a quality perspective, even though it’s hard to put into one word, the care of acute GI pathology and endoscopy can be seen as a specialty in and of itself. These skills include hemostasis, enteral access, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG), balloon-assisted enteroscopy, luminal stenting, advanced tissue closure, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. The greater availability of a GI hospitalist, as opposed to an outpatient GI doctor rounding at the ends of days, likely shortens admissions and improves the logistics of scheduling inpatient cases.

From a financial perspective, the landscape of GI practice is changing because of GI physician shortages relative to increased demand for outpatient procedures. Namely, the outpatient gastroenterologists simply have too much on their plate and inefficiencies abound when they have to juggle inpatient and outpatient work. Thus, two tracks are forming, especially in large busy hospitals. This is the same evolution of the pure outpatient internist and inpatient internist 20 years ago.

Q: What attributes does a GI hospitalist bring to the table?

Dr. Tau: A GI hospitalist is one who can multitask through interruptions, manage end-of-life issues, craves therapeutic endoscopy (even if that’s hemostasis), and can keep more erratic hours based on the number of consults that come in. She/he tends to want immediate gratification and doesn’t mind the lack of continuity of care. Lastly, the GI hospitalist has to be brave and yet careful as the patients are sicker and thus complications may be higher and certainly less well tolerated.

Q: Are there enough of them going into practice right now?

Dr. Tau: Not really! The demand seems to outstrip supply based on what I see. There is a definite financial lure as the market rate for them rises (because more GIs are leaving the hospital for pure outpatient practice), but burnout can be an issue. Interestingly, fellows are typically highly trained and familiar with inpatient work, but once in practice, most choose the outpatient track. I think it’s a combination of work-life balance, inefficiency of inpatient endoscopy, and perhaps the strain of daily, erratic consultation.

Q: You received the 2021 Travis County Medical Society (TCMS) Young Physician of the Year. What achievements led to this honor?

Dr. Tau: I am not sure I am deserving of that award, but I think it was related to personal risk and some long hours as a GI hospitalist during the COVID pandemic. I may have the unfortunate distinction of performing more procedures on COVID patients than any other physician in the city. My hospital was the largest COVID-designated site in the city. There were countless PEG tubes in COVID survivors and a lot of bleeders for some reason. A critical care physician on the front lines and health director of the city of Austin received Physician of the Year, deservedly.

Q: What teacher or mentor had the greatest impact on you?

Dr. Tau: David Y. Graham, MD, MACG, got me into GI as a medical student and taught me to never tolerate any loose ends when it came to patient care as a resident. He trained me at every level — from medical school, residency, and through my fellowship. His advice is often delivered sly and dry, but his humor-laden truths continue to ring true throughout my life. One story: my whole family tested positive for Helicobacter pylori after my mother survived peptic ulcer hemorrhage. I was the only one who tested negative! I asked Dr Graham about it and he quipped, “You’re lucky! It’s because your mother didn’t love (and kiss) you as much!”

Even to this moment I laugh about that. I share that with my patients when they ask about how they contracted H. pylori.

Lightning Round

Favorite junk food?

McDonalds fries

Favorite movie genre?

Psychological thriller

Cat person or dog person?

Dog

What was your favorite Halloween costume?

Ninja turtle

Favorite sport:

Football (played in college)

Introvert or extrovert?

Extrovert unless sleep deprived.

Favorite holiday:

Thanksgiving

The book you read over and over:

Swiss Family Robinson

Favorite travel destination:

Hawaii

Optimist or pessimist?

A happy pessimist.

AGA Tech Summit Focuses on Accelerating Innovation

The AGA Tech Summit is building on the success of past summits and moving in a new direction. The reimagined summit will accelerate innovation by bringing together MedTech startups, innovators, investors and leaders in the field.

“It’s a new world out there. The Tech Summit now reflects the new direction AGA is taking in innovation,” said Lawrence R. Kosinski, MD, AGA at-large councilor for development and growth. “We want to help GI innovators successfully navigate the innovation lifecycle from start to finish and bring new technologies to market.”

The Tech Summit will take place April 11-12 in Chicago at MATTER, located at the Merchandise Mart. MATTER supports healthcare startups at all stages of growth and brings together industry executives, entrepreneurs, and investors to accelerate innovation, advance care and improve lives.

Highlights of the Tech Summit include:

- Keynote addresses from leaders in the field of GI innovation.

- Panel discussions with VC strategists.

- The Shark Tank Pitch Competition featuring emerging GI technologies.

- Multiple opportunities to network innovators, investors and leaders in the field.

- One-on-one consultations with VCs.

.

The AGA Tech Summit is building on the success of past summits and moving in a new direction. The reimagined summit will accelerate innovation by bringing together MedTech startups, innovators, investors and leaders in the field.

“It’s a new world out there. The Tech Summit now reflects the new direction AGA is taking in innovation,” said Lawrence R. Kosinski, MD, AGA at-large councilor for development and growth. “We want to help GI innovators successfully navigate the innovation lifecycle from start to finish and bring new technologies to market.”

The Tech Summit will take place April 11-12 in Chicago at MATTER, located at the Merchandise Mart. MATTER supports healthcare startups at all stages of growth and brings together industry executives, entrepreneurs, and investors to accelerate innovation, advance care and improve lives.

Highlights of the Tech Summit include:

- Keynote addresses from leaders in the field of GI innovation.

- Panel discussions with VC strategists.

- The Shark Tank Pitch Competition featuring emerging GI technologies.

- Multiple opportunities to network innovators, investors and leaders in the field.

- One-on-one consultations with VCs.

.

The AGA Tech Summit is building on the success of past summits and moving in a new direction. The reimagined summit will accelerate innovation by bringing together MedTech startups, innovators, investors and leaders in the field.

“It’s a new world out there. The Tech Summit now reflects the new direction AGA is taking in innovation,” said Lawrence R. Kosinski, MD, AGA at-large councilor for development and growth. “We want to help GI innovators successfully navigate the innovation lifecycle from start to finish and bring new technologies to market.”

The Tech Summit will take place April 11-12 in Chicago at MATTER, located at the Merchandise Mart. MATTER supports healthcare startups at all stages of growth and brings together industry executives, entrepreneurs, and investors to accelerate innovation, advance care and improve lives.

Highlights of the Tech Summit include:

- Keynote addresses from leaders in the field of GI innovation.

- Panel discussions with VC strategists.

- The Shark Tank Pitch Competition featuring emerging GI technologies.

- Multiple opportunities to network innovators, investors and leaders in the field.

- One-on-one consultations with VCs.

.

AGA Gives Guidance on Subepithelial Lesions

The new guidance document, authored by Lionel S. D’Souza, MD, of Stony Brook University Hospital, Stony Brook, New York, and colleagues, offers a framework for deciding between various EFTR techniques based on lesion histology, size, and location.

“EFTR has emerged as a novel treatment option for select SELs,” the update panelists wrote in Gastroenterology. “In this commentary, we reviewed the different techniques and uses of EFTR for the management of SELs.”

They noted that all patients with SELs should first undergo multidisciplinary evaluation in accordance with a separate AGA guidance document on SELs.

The present update focuses specifically on EFTR, first by distinguishing between exposed and nonexposed techniques. While the former involves resection of the mucosa and all other layers of the wall, the latter relies upon a ‘close first, then cut’ method to prevent perforation, or preservation of an overlying flap of mucosa.

The new guidance calls for a nonexposed technique unless the exposed approach is necessary.

“In our opinion, the exposed EFTR technique should be considered for lesions in which other methods (i.e., endoscopic mucosal resection, endoscopic submucosal dissection, and nonexposed EFTR) cannot reliably and completely excise SELs due to larger size or difficult location of the lesion,” the update panelists wrote. “The exposed EFTR technique may be best suited for gastric lesions and as an alternative to other endoscopic approaches for SELs in the rectum. The exposed technique should be avoided in the esophagus and duodenum, as the clinical consequences of a leak can be devastating and endoscopic closure is notoriously challenging.”

Dr. D’Souza and colleagues went on to discuss various nonexposed techniques, including submucosal tunneling and endoscopic resection and peroral endoscopic tunnel resection (STER/POET), device-assisted endoscopic full-thickness resection, and full-thickness resection with an over-the-scope clip with integrated snare (FTRD).

They highlighted how STER/POET encourages traction on the lesion and scope stability while limiting extravasation of luminal contents, and closure tends to be easier than with exposed EFTR. This approach should be reserved for tumors smaller than approximately 3-4 cm, however, with the update noting that lesions larger than 2 cm may present increased risk of incomplete resection. Similarly, device-assisted endoscopic full-thickness resection, which involves pulling or suctioning the lesion into the device, is also limited by lesion size, although fewer data are available to guide size thresholds.

FTRD, which involves “a 23-mm deep cap with a specially designed over-the-scope clip and integrated cautery snare,” also lacks a broad evidence base.

“Although there has been reasonable clinical success reported in most case series, several factors should be considered with the use of the FTRD for SELs,” the update cautions.

Specifically, a recent Dutch and German registry study of FTRD had an adverse event rate of 11.3%, with an approximate 1% perforation rate. More than half of the perforations were due to technical or procedural issues.

“This adverse event rate may improve as individual experience with the device is gained; however, data on this are lacking,” the panelists wrote, also noting that lesions 1.5 cm or larger may carry a higher risk of incomplete resection.

Ultimately, the clinical practice update calls for a personalized approach to EFTR decision-making that considers factors extending beyond the lesion.

“The ‘ideal’ technique will depend on various patient and lesion characteristics, as well as the endoscopist’s preference and available expertise,” Dr. D’Souza and colleagues concluded. “Further research into the efficacy of these resection techniques and the long-term outcomes in patients after endoscopic resection of SELs will be essential in standardizing appropriate resection algorithms.”

This clinical practice update was commissioned and approved by AGA Institute. The investigators disclosed relationships with Olympus, Fujifilm, Apollo Endosurgery, and others.

The new guidance document, authored by Lionel S. D’Souza, MD, of Stony Brook University Hospital, Stony Brook, New York, and colleagues, offers a framework for deciding between various EFTR techniques based on lesion histology, size, and location.

“EFTR has emerged as a novel treatment option for select SELs,” the update panelists wrote in Gastroenterology. “In this commentary, we reviewed the different techniques and uses of EFTR for the management of SELs.”

They noted that all patients with SELs should first undergo multidisciplinary evaluation in accordance with a separate AGA guidance document on SELs.

The present update focuses specifically on EFTR, first by distinguishing between exposed and nonexposed techniques. While the former involves resection of the mucosa and all other layers of the wall, the latter relies upon a ‘close first, then cut’ method to prevent perforation, or preservation of an overlying flap of mucosa.

The new guidance calls for a nonexposed technique unless the exposed approach is necessary.

“In our opinion, the exposed EFTR technique should be considered for lesions in which other methods (i.e., endoscopic mucosal resection, endoscopic submucosal dissection, and nonexposed EFTR) cannot reliably and completely excise SELs due to larger size or difficult location of the lesion,” the update panelists wrote. “The exposed EFTR technique may be best suited for gastric lesions and as an alternative to other endoscopic approaches for SELs in the rectum. The exposed technique should be avoided in the esophagus and duodenum, as the clinical consequences of a leak can be devastating and endoscopic closure is notoriously challenging.”

Dr. D’Souza and colleagues went on to discuss various nonexposed techniques, including submucosal tunneling and endoscopic resection and peroral endoscopic tunnel resection (STER/POET), device-assisted endoscopic full-thickness resection, and full-thickness resection with an over-the-scope clip with integrated snare (FTRD).

They highlighted how STER/POET encourages traction on the lesion and scope stability while limiting extravasation of luminal contents, and closure tends to be easier than with exposed EFTR. This approach should be reserved for tumors smaller than approximately 3-4 cm, however, with the update noting that lesions larger than 2 cm may present increased risk of incomplete resection. Similarly, device-assisted endoscopic full-thickness resection, which involves pulling or suctioning the lesion into the device, is also limited by lesion size, although fewer data are available to guide size thresholds.

FTRD, which involves “a 23-mm deep cap with a specially designed over-the-scope clip and integrated cautery snare,” also lacks a broad evidence base.

“Although there has been reasonable clinical success reported in most case series, several factors should be considered with the use of the FTRD for SELs,” the update cautions.

Specifically, a recent Dutch and German registry study of FTRD had an adverse event rate of 11.3%, with an approximate 1% perforation rate. More than half of the perforations were due to technical or procedural issues.

“This adverse event rate may improve as individual experience with the device is gained; however, data on this are lacking,” the panelists wrote, also noting that lesions 1.5 cm or larger may carry a higher risk of incomplete resection.

Ultimately, the clinical practice update calls for a personalized approach to EFTR decision-making that considers factors extending beyond the lesion.

“The ‘ideal’ technique will depend on various patient and lesion characteristics, as well as the endoscopist’s preference and available expertise,” Dr. D’Souza and colleagues concluded. “Further research into the efficacy of these resection techniques and the long-term outcomes in patients after endoscopic resection of SELs will be essential in standardizing appropriate resection algorithms.”

This clinical practice update was commissioned and approved by AGA Institute. The investigators disclosed relationships with Olympus, Fujifilm, Apollo Endosurgery, and others.

The new guidance document, authored by Lionel S. D’Souza, MD, of Stony Brook University Hospital, Stony Brook, New York, and colleagues, offers a framework for deciding between various EFTR techniques based on lesion histology, size, and location.

“EFTR has emerged as a novel treatment option for select SELs,” the update panelists wrote in Gastroenterology. “In this commentary, we reviewed the different techniques and uses of EFTR for the management of SELs.”

They noted that all patients with SELs should first undergo multidisciplinary evaluation in accordance with a separate AGA guidance document on SELs.

The present update focuses specifically on EFTR, first by distinguishing between exposed and nonexposed techniques. While the former involves resection of the mucosa and all other layers of the wall, the latter relies upon a ‘close first, then cut’ method to prevent perforation, or preservation of an overlying flap of mucosa.

The new guidance calls for a nonexposed technique unless the exposed approach is necessary.

“In our opinion, the exposed EFTR technique should be considered for lesions in which other methods (i.e., endoscopic mucosal resection, endoscopic submucosal dissection, and nonexposed EFTR) cannot reliably and completely excise SELs due to larger size or difficult location of the lesion,” the update panelists wrote. “The exposed EFTR technique may be best suited for gastric lesions and as an alternative to other endoscopic approaches for SELs in the rectum. The exposed technique should be avoided in the esophagus and duodenum, as the clinical consequences of a leak can be devastating and endoscopic closure is notoriously challenging.”

Dr. D’Souza and colleagues went on to discuss various nonexposed techniques, including submucosal tunneling and endoscopic resection and peroral endoscopic tunnel resection (STER/POET), device-assisted endoscopic full-thickness resection, and full-thickness resection with an over-the-scope clip with integrated snare (FTRD).

They highlighted how STER/POET encourages traction on the lesion and scope stability while limiting extravasation of luminal contents, and closure tends to be easier than with exposed EFTR. This approach should be reserved for tumors smaller than approximately 3-4 cm, however, with the update noting that lesions larger than 2 cm may present increased risk of incomplete resection. Similarly, device-assisted endoscopic full-thickness resection, which involves pulling or suctioning the lesion into the device, is also limited by lesion size, although fewer data are available to guide size thresholds.

FTRD, which involves “a 23-mm deep cap with a specially designed over-the-scope clip and integrated cautery snare,” also lacks a broad evidence base.

“Although there has been reasonable clinical success reported in most case series, several factors should be considered with the use of the FTRD for SELs,” the update cautions.

Specifically, a recent Dutch and German registry study of FTRD had an adverse event rate of 11.3%, with an approximate 1% perforation rate. More than half of the perforations were due to technical or procedural issues.

“This adverse event rate may improve as individual experience with the device is gained; however, data on this are lacking,” the panelists wrote, also noting that lesions 1.5 cm or larger may carry a higher risk of incomplete resection.

Ultimately, the clinical practice update calls for a personalized approach to EFTR decision-making that considers factors extending beyond the lesion.

“The ‘ideal’ technique will depend on various patient and lesion characteristics, as well as the endoscopist’s preference and available expertise,” Dr. D’Souza and colleagues concluded. “Further research into the efficacy of these resection techniques and the long-term outcomes in patients after endoscopic resection of SELs will be essential in standardizing appropriate resection algorithms.”

This clinical practice update was commissioned and approved by AGA Institute. The investigators disclosed relationships with Olympus, Fujifilm, Apollo Endosurgery, and others.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

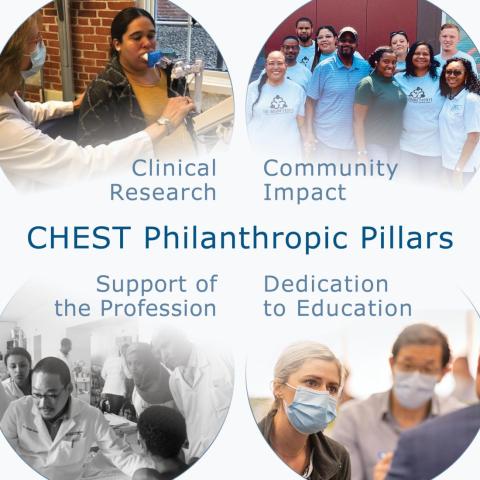

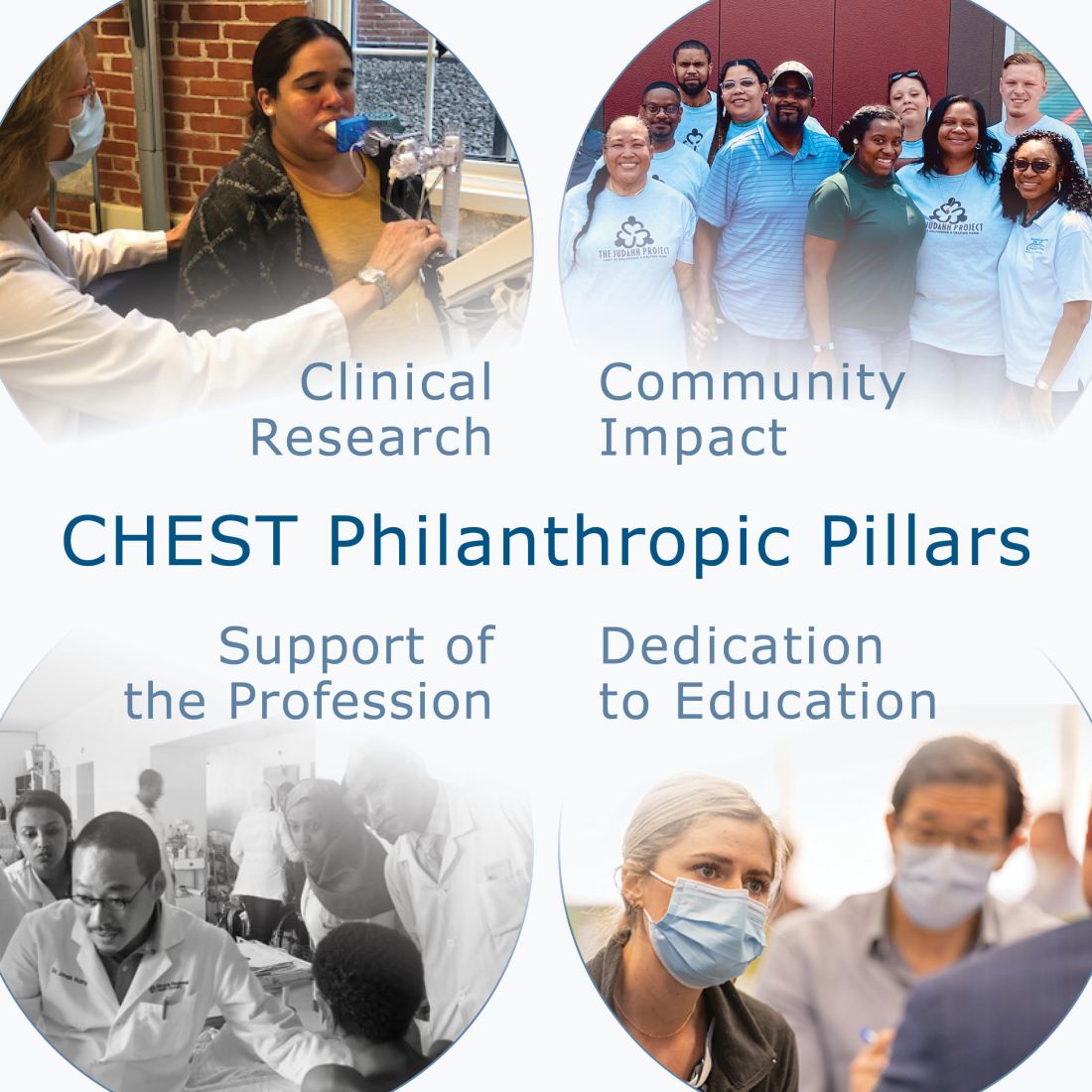

New age of CHEST philanthropy to focus on education, impact, community

In a time echoing with the constant call for transformation, CHEST delved deep into its essence, questioning its potential for impact. This pivotal introspection led to a crucial inquiry…

Are we harnessing every opportunity to make a difference?

It’s a familiar question, yet its resonance urged a deeper evaluation.

Philanthropy has long been entwined in CHEST’s identity. Commemorating 25 years of the CHEST Foundation at CHEST 2022 spotlighted our history of generosity. Stories of transformative community initiatives and pivotal clinical research grants narrated a tale of empowered change and fostering healthier communities worldwide.

However, amid these achievements, more pressing inquiries surfaced:

- What unique role can CHEST play?

- Where do unmet needs persist?

- Which causes deeply resonate within our community?

CHEST’s leadership and dedicated staff embarked on a comprehensive review, scrutinizing past triumphs, donor commitments, and the evolving aspirations of our members. Themes of social responsibility, professional diversity, community impact, and expanded partnerships emerged as pivotal points. This extensive process, spanning nearly a year, resembled a reflective pause amid the rapid cadence of change.

Achieving these aspirations meant reimagining our approach, thereby streamlining efforts for maximal impact by…

- Integrating philanthropy as an integral facet of our mission, and amplifying the culture of giving within CHEST

- Consolidating philanthropic initiatives under CHEST to maximize resources for direct, substantial impact

- Defining clear avenues for giving that deeply resonate with our members

With endorsement from the Board of Regents, the CHEST Foundation seamlessly merged into CHEST, inaugurating a new chapter in our philanthropic endeavors.

Central to this transformative shift is the crystallization of our giving strategy, fortified by four pillars: Clinical Research, Community Impact, Support to the Profession, and Dedication to Education. These pillars encapsulate our commitment to nurturing clinicians, supporting trainees, and enhancing patient care.

Clinical Research emerges as the cornerstone, transcending boundaries to empower researchers in their pursuit of groundbreaking insights. Through strategic grants, we embolden early career investigators to delve into uncharted territories, unraveling mysteries that underpin advancements in chest medicine. The ripple effect extends beyond labs; it traverses communities, amplifying equitable health care solutions and bridging disparities in patient care. Our commitment to nurturing this pillar springs from the belief that every breakthrough, regardless of scale, is a catalyst for transformative change.

Community Impact extends CHEST’s reach far beyond clinical settings, fostering alliances with local organizations. Together, we forge a tapestry of collaboration, weaving essential services and imparting knowledge on crucial lung health issues into the fabric of diverse communities. This engagement not only elevates awareness but also empowers individuals and communities to take charge of their respiratory well-being. It’s the grassroots unity that amplifies our impact, creating enduring shifts in local landscapes.

Support of the Profession epitomizes our dedication to fortifying the backbone of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine. By offering unparalleled clinical education and mentorship, we empower emerging clinicians from diverse backgrounds with the latest knowledge and resources. Fueling their professional growth is pivotal to nurturing a robust and inclusive cadre of health care professionals, ensuring comprehensive and culturally sensitive care for patients worldwide.

Dedication to Education isn’t just a commitment—it’s a bridge spanning the gap between knowledge and application, patient and clinician. Strengthening this connection involves equipping clinicians with tools for effective communication and partnering with patient-centered organizations. Our focus transcends textbooks; it embodies a relentless pursuit to refine patient-clinician interactions, enhancing patient understanding and, ultimately, elevating their quality of life.

CHEST’s philanthropic evolution signifies not just growth but a resolute commitment to effecting tangible change in chest medicine and patient care. These pillars stand as guiding beacons, steering us toward a future that mirrors our mission, vision, and values. Each pillar represents a pathway to meaningful, enduring change within chest medicine, ensuring a lasting impact on patient well-being.

In a time echoing with the constant call for transformation, CHEST delved deep into its essence, questioning its potential for impact. This pivotal introspection led to a crucial inquiry…

Are we harnessing every opportunity to make a difference?

It’s a familiar question, yet its resonance urged a deeper evaluation.

Philanthropy has long been entwined in CHEST’s identity. Commemorating 25 years of the CHEST Foundation at CHEST 2022 spotlighted our history of generosity. Stories of transformative community initiatives and pivotal clinical research grants narrated a tale of empowered change and fostering healthier communities worldwide.

However, amid these achievements, more pressing inquiries surfaced:

- What unique role can CHEST play?

- Where do unmet needs persist?

- Which causes deeply resonate within our community?

CHEST’s leadership and dedicated staff embarked on a comprehensive review, scrutinizing past triumphs, donor commitments, and the evolving aspirations of our members. Themes of social responsibility, professional diversity, community impact, and expanded partnerships emerged as pivotal points. This extensive process, spanning nearly a year, resembled a reflective pause amid the rapid cadence of change.

Achieving these aspirations meant reimagining our approach, thereby streamlining efforts for maximal impact by…

- Integrating philanthropy as an integral facet of our mission, and amplifying the culture of giving within CHEST

- Consolidating philanthropic initiatives under CHEST to maximize resources for direct, substantial impact

- Defining clear avenues for giving that deeply resonate with our members

With endorsement from the Board of Regents, the CHEST Foundation seamlessly merged into CHEST, inaugurating a new chapter in our philanthropic endeavors.

Central to this transformative shift is the crystallization of our giving strategy, fortified by four pillars: Clinical Research, Community Impact, Support to the Profession, and Dedication to Education. These pillars encapsulate our commitment to nurturing clinicians, supporting trainees, and enhancing patient care.

Clinical Research emerges as the cornerstone, transcending boundaries to empower researchers in their pursuit of groundbreaking insights. Through strategic grants, we embolden early career investigators to delve into uncharted territories, unraveling mysteries that underpin advancements in chest medicine. The ripple effect extends beyond labs; it traverses communities, amplifying equitable health care solutions and bridging disparities in patient care. Our commitment to nurturing this pillar springs from the belief that every breakthrough, regardless of scale, is a catalyst for transformative change.

Community Impact extends CHEST’s reach far beyond clinical settings, fostering alliances with local organizations. Together, we forge a tapestry of collaboration, weaving essential services and imparting knowledge on crucial lung health issues into the fabric of diverse communities. This engagement not only elevates awareness but also empowers individuals and communities to take charge of their respiratory well-being. It’s the grassroots unity that amplifies our impact, creating enduring shifts in local landscapes.

Support of the Profession epitomizes our dedication to fortifying the backbone of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine. By offering unparalleled clinical education and mentorship, we empower emerging clinicians from diverse backgrounds with the latest knowledge and resources. Fueling their professional growth is pivotal to nurturing a robust and inclusive cadre of health care professionals, ensuring comprehensive and culturally sensitive care for patients worldwide.

Dedication to Education isn’t just a commitment—it’s a bridge spanning the gap between knowledge and application, patient and clinician. Strengthening this connection involves equipping clinicians with tools for effective communication and partnering with patient-centered organizations. Our focus transcends textbooks; it embodies a relentless pursuit to refine patient-clinician interactions, enhancing patient understanding and, ultimately, elevating their quality of life.

CHEST’s philanthropic evolution signifies not just growth but a resolute commitment to effecting tangible change in chest medicine and patient care. These pillars stand as guiding beacons, steering us toward a future that mirrors our mission, vision, and values. Each pillar represents a pathway to meaningful, enduring change within chest medicine, ensuring a lasting impact on patient well-being.

In a time echoing with the constant call for transformation, CHEST delved deep into its essence, questioning its potential for impact. This pivotal introspection led to a crucial inquiry…

Are we harnessing every opportunity to make a difference?

It’s a familiar question, yet its resonance urged a deeper evaluation.

Philanthropy has long been entwined in CHEST’s identity. Commemorating 25 years of the CHEST Foundation at CHEST 2022 spotlighted our history of generosity. Stories of transformative community initiatives and pivotal clinical research grants narrated a tale of empowered change and fostering healthier communities worldwide.

However, amid these achievements, more pressing inquiries surfaced:

- What unique role can CHEST play?

- Where do unmet needs persist?

- Which causes deeply resonate within our community?

CHEST’s leadership and dedicated staff embarked on a comprehensive review, scrutinizing past triumphs, donor commitments, and the evolving aspirations of our members. Themes of social responsibility, professional diversity, community impact, and expanded partnerships emerged as pivotal points. This extensive process, spanning nearly a year, resembled a reflective pause amid the rapid cadence of change.

Achieving these aspirations meant reimagining our approach, thereby streamlining efforts for maximal impact by…

- Integrating philanthropy as an integral facet of our mission, and amplifying the culture of giving within CHEST

- Consolidating philanthropic initiatives under CHEST to maximize resources for direct, substantial impact

- Defining clear avenues for giving that deeply resonate with our members

With endorsement from the Board of Regents, the CHEST Foundation seamlessly merged into CHEST, inaugurating a new chapter in our philanthropic endeavors.

Central to this transformative shift is the crystallization of our giving strategy, fortified by four pillars: Clinical Research, Community Impact, Support to the Profession, and Dedication to Education. These pillars encapsulate our commitment to nurturing clinicians, supporting trainees, and enhancing patient care.

Clinical Research emerges as the cornerstone, transcending boundaries to empower researchers in their pursuit of groundbreaking insights. Through strategic grants, we embolden early career investigators to delve into uncharted territories, unraveling mysteries that underpin advancements in chest medicine. The ripple effect extends beyond labs; it traverses communities, amplifying equitable health care solutions and bridging disparities in patient care. Our commitment to nurturing this pillar springs from the belief that every breakthrough, regardless of scale, is a catalyst for transformative change.

Community Impact extends CHEST’s reach far beyond clinical settings, fostering alliances with local organizations. Together, we forge a tapestry of collaboration, weaving essential services and imparting knowledge on crucial lung health issues into the fabric of diverse communities. This engagement not only elevates awareness but also empowers individuals and communities to take charge of their respiratory well-being. It’s the grassroots unity that amplifies our impact, creating enduring shifts in local landscapes.

Support of the Profession epitomizes our dedication to fortifying the backbone of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine. By offering unparalleled clinical education and mentorship, we empower emerging clinicians from diverse backgrounds with the latest knowledge and resources. Fueling their professional growth is pivotal to nurturing a robust and inclusive cadre of health care professionals, ensuring comprehensive and culturally sensitive care for patients worldwide.

Dedication to Education isn’t just a commitment—it’s a bridge spanning the gap between knowledge and application, patient and clinician. Strengthening this connection involves equipping clinicians with tools for effective communication and partnering with patient-centered organizations. Our focus transcends textbooks; it embodies a relentless pursuit to refine patient-clinician interactions, enhancing patient understanding and, ultimately, elevating their quality of life.

CHEST’s philanthropic evolution signifies not just growth but a resolute commitment to effecting tangible change in chest medicine and patient care. These pillars stand as guiding beacons, steering us toward a future that mirrors our mission, vision, and values. Each pillar represents a pathway to meaningful, enduring change within chest medicine, ensuring a lasting impact on patient well-being.

Biomarker checklist seeks to expedite NSCLC diagnoses

Drs. Tamer Said Ahmed and Adam Fox receive funding for quality improvement projects in biomarker testing

Establishing a systematic biomarker testing program for patients with suspected non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) takes both time and collaboration across specialties. To standardize this process, the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) created two clinician checklists for use in practice.

The case-by-case checklist helps guide physicians to ensure timely and comprehensive biomarker testing for individual patients, and the programmatic/institutional checklist is for multidisciplinary teams to enable clear expectations and processes across hand-offs to aid in the testing process.

To substantiate best practices for ordering biomarker tests using the checklists, CHEST issued quality improvement demonstration grants for implementation at two institutions. This year, Tamer Said Ahmed, MD, FCCP, pulmonary and sleep physician at Toledo Hospital (ProMedica Health System) and Assistant Professor at the University of Toledo, and Adam Fox, MD, MS, Assistant Professor of Medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina, will begin projects to improve biomarker testing.

“Biomarker testing allows for tailored treatment plans that drastically impact the progression of lung cancer, but every hospital system and practice is following a different procedure for testing,” Dr. Said Ahmed said. “To best serve the patient, our project aims to streamline the approach to biomarker testing to bridge health care inconsistencies. Given the intense progression of some forms of lung cancer where every week matters, the more streamlined we can make the biomarker testing process, the earlier we will get to an accurate diagnosis, begin treatment, and likely extend the life of a patient.”

Discrepancies in the testing process stem from existing silos between specialties, including pathology, oncology, interventional radiology, and more. Care is fragmented, leading to delays like repeat biopsies because a large enough sample was not taken the first time.

This is the exact problem that checklist implementation will seek to solve.

“By intent, these checklists help to provide a systematic approach to timely and comprehensive biomarker testing,” said Dr. Fox, who was also part of the team that developed the checklists. “What we need now is to implement them into clinical practice to gain metrics that can be studied, identified, and will lead to the process being widely accepted. To truly impact practice, we need to be able to provide strong evidence for interventions that work for clinicians to implement.”

To learn more and download the checklists, visit CHEST’s Thoracic Oncology Topic Collection onlineThis project is supported in part by AstraZeneca, Sanofi, and Pfizer.

Drs. Tamer Said Ahmed and Adam Fox receive funding for quality improvement projects in biomarker testing

Drs. Tamer Said Ahmed and Adam Fox receive funding for quality improvement projects in biomarker testing

Establishing a systematic biomarker testing program for patients with suspected non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) takes both time and collaboration across specialties. To standardize this process, the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) created two clinician checklists for use in practice.

The case-by-case checklist helps guide physicians to ensure timely and comprehensive biomarker testing for individual patients, and the programmatic/institutional checklist is for multidisciplinary teams to enable clear expectations and processes across hand-offs to aid in the testing process.

To substantiate best practices for ordering biomarker tests using the checklists, CHEST issued quality improvement demonstration grants for implementation at two institutions. This year, Tamer Said Ahmed, MD, FCCP, pulmonary and sleep physician at Toledo Hospital (ProMedica Health System) and Assistant Professor at the University of Toledo, and Adam Fox, MD, MS, Assistant Professor of Medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina, will begin projects to improve biomarker testing.

“Biomarker testing allows for tailored treatment plans that drastically impact the progression of lung cancer, but every hospital system and practice is following a different procedure for testing,” Dr. Said Ahmed said. “To best serve the patient, our project aims to streamline the approach to biomarker testing to bridge health care inconsistencies. Given the intense progression of some forms of lung cancer where every week matters, the more streamlined we can make the biomarker testing process, the earlier we will get to an accurate diagnosis, begin treatment, and likely extend the life of a patient.”

Discrepancies in the testing process stem from existing silos between specialties, including pathology, oncology, interventional radiology, and more. Care is fragmented, leading to delays like repeat biopsies because a large enough sample was not taken the first time.

This is the exact problem that checklist implementation will seek to solve.

“By intent, these checklists help to provide a systematic approach to timely and comprehensive biomarker testing,” said Dr. Fox, who was also part of the team that developed the checklists. “What we need now is to implement them into clinical practice to gain metrics that can be studied, identified, and will lead to the process being widely accepted. To truly impact practice, we need to be able to provide strong evidence for interventions that work for clinicians to implement.”

To learn more and download the checklists, visit CHEST’s Thoracic Oncology Topic Collection onlineThis project is supported in part by AstraZeneca, Sanofi, and Pfizer.

Establishing a systematic biomarker testing program for patients with suspected non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) takes both time and collaboration across specialties. To standardize this process, the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) created two clinician checklists for use in practice.

The case-by-case checklist helps guide physicians to ensure timely and comprehensive biomarker testing for individual patients, and the programmatic/institutional checklist is for multidisciplinary teams to enable clear expectations and processes across hand-offs to aid in the testing process.

To substantiate best practices for ordering biomarker tests using the checklists, CHEST issued quality improvement demonstration grants for implementation at two institutions. This year, Tamer Said Ahmed, MD, FCCP, pulmonary and sleep physician at Toledo Hospital (ProMedica Health System) and Assistant Professor at the University of Toledo, and Adam Fox, MD, MS, Assistant Professor of Medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina, will begin projects to improve biomarker testing.

“Biomarker testing allows for tailored treatment plans that drastically impact the progression of lung cancer, but every hospital system and practice is following a different procedure for testing,” Dr. Said Ahmed said. “To best serve the patient, our project aims to streamline the approach to biomarker testing to bridge health care inconsistencies. Given the intense progression of some forms of lung cancer where every week matters, the more streamlined we can make the biomarker testing process, the earlier we will get to an accurate diagnosis, begin treatment, and likely extend the life of a patient.”

Discrepancies in the testing process stem from existing silos between specialties, including pathology, oncology, interventional radiology, and more. Care is fragmented, leading to delays like repeat biopsies because a large enough sample was not taken the first time.

This is the exact problem that checklist implementation will seek to solve.

“By intent, these checklists help to provide a systematic approach to timely and comprehensive biomarker testing,” said Dr. Fox, who was also part of the team that developed the checklists. “What we need now is to implement them into clinical practice to gain metrics that can be studied, identified, and will lead to the process being widely accepted. To truly impact practice, we need to be able to provide strong evidence for interventions that work for clinicians to implement.”

To learn more and download the checklists, visit CHEST’s Thoracic Oncology Topic Collection onlineThis project is supported in part by AstraZeneca, Sanofi, and Pfizer.

Examining the past and looking toward the future: The need for quality data in interventional pulmonology

THORACIC ONCOLOGY AND CHEST PROCEDURES NETWORK

Interventional Procedures Section

During the last decade, the explosion of technological advancements in the field of interventional pulmonary (IP) has afforded patients the opportunity to undergo novel, minimally invasive diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. However, these unprecedented technological advances have often been introduced without the support of high-quality research on safety and efficacy, and without evaluating their impact on meaningful patient outcomes. Encouraging and participating in high-quality IP research should remain a top priority for those practicing in the field.

Structured research networks, such as the UK Pleural Society and more recently the Interventional Pulmonary Outcome Group, have facilitated the transition of IP research from observational case series and single-center experiences to multicenter, randomized controlled trials to generate level I evidence and inform patient care (Laskawiec-Szkonter M, et al. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2019 Apr 2;80[4]:186-7) (Maldonado F, et al. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2019 Jul;26(3):150-2). In the bronchoscopy space, important investigator-initiated clinical trial results anticipated in 2024 include VERITAS (NCT04250194), FROSTBITE2 (NCT05751278), and RELIANT (NCT05705544), among others. These research efforts complement industry-sponsored clinical trials (such as RheSolve, NCT04677465) and aim to emulate the extraordinary track record achieved in the field of pleural disease that has led to recently updated evidence-based guidelines for the management of challenging diseases like malignant pleural effusions, pleural space infections, and pneumothorax (Davies HE, et a l. JAMA. 2012 Jun 13;307[22]:2383-9, Mishra EK, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018 Feb 15;197[4]:502-8) (Rahman NM, et al. N Engl J Med. 2011 Aug 11;365[6]:518-26) (Hallifax RJ, et al. Lancet. 2020 Jul 4;396[10243]:39-49).

Ultimately, the rapidly evolving technological advancements in interventional pulmonology must be supported by research based on high-quality clinical trials, which will be contingent on appropriate trial funding requiring partnership with industry and federal funding agencies. Only through such collaboration can researchers design robust clinical trials based on complex methodology, which will advance patient care and lead to improved patient outcomes.

– Jennifer D. Duke, MD

Section Fellow-in-Training

– Fabien Maldonado, MD, MSc, FCCP

Section Member

THORACIC ONCOLOGY AND CHEST PROCEDURES NETWORK

Interventional Procedures Section

During the last decade, the explosion of technological advancements in the field of interventional pulmonary (IP) has afforded patients the opportunity to undergo novel, minimally invasive diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. However, these unprecedented technological advances have often been introduced without the support of high-quality research on safety and efficacy, and without evaluating their impact on meaningful patient outcomes. Encouraging and participating in high-quality IP research should remain a top priority for those practicing in the field.

Structured research networks, such as the UK Pleural Society and more recently the Interventional Pulmonary Outcome Group, have facilitated the transition of IP research from observational case series and single-center experiences to multicenter, randomized controlled trials to generate level I evidence and inform patient care (Laskawiec-Szkonter M, et al. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2019 Apr 2;80[4]:186-7) (Maldonado F, et al. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2019 Jul;26(3):150-2). In the bronchoscopy space, important investigator-initiated clinical trial results anticipated in 2024 include VERITAS (NCT04250194), FROSTBITE2 (NCT05751278), and RELIANT (NCT05705544), among others. These research efforts complement industry-sponsored clinical trials (such as RheSolve, NCT04677465) and aim to emulate the extraordinary track record achieved in the field of pleural disease that has led to recently updated evidence-based guidelines for the management of challenging diseases like malignant pleural effusions, pleural space infections, and pneumothorax (Davies HE, et a l. JAMA. 2012 Jun 13;307[22]:2383-9, Mishra EK, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018 Feb 15;197[4]:502-8) (Rahman NM, et al. N Engl J Med. 2011 Aug 11;365[6]:518-26) (Hallifax RJ, et al. Lancet. 2020 Jul 4;396[10243]:39-49).

Ultimately, the rapidly evolving technological advancements in interventional pulmonology must be supported by research based on high-quality clinical trials, which will be contingent on appropriate trial funding requiring partnership with industry and federal funding agencies. Only through such collaboration can researchers design robust clinical trials based on complex methodology, which will advance patient care and lead to improved patient outcomes.

– Jennifer D. Duke, MD

Section Fellow-in-Training

– Fabien Maldonado, MD, MSc, FCCP

Section Member

THORACIC ONCOLOGY AND CHEST PROCEDURES NETWORK

Interventional Procedures Section

During the last decade, the explosion of technological advancements in the field of interventional pulmonary (IP) has afforded patients the opportunity to undergo novel, minimally invasive diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. However, these unprecedented technological advances have often been introduced without the support of high-quality research on safety and efficacy, and without evaluating their impact on meaningful patient outcomes. Encouraging and participating in high-quality IP research should remain a top priority for those practicing in the field.

Structured research networks, such as the UK Pleural Society and more recently the Interventional Pulmonary Outcome Group, have facilitated the transition of IP research from observational case series and single-center experiences to multicenter, randomized controlled trials to generate level I evidence and inform patient care (Laskawiec-Szkonter M, et al. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2019 Apr 2;80[4]:186-7) (Maldonado F, et al. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2019 Jul;26(3):150-2). In the bronchoscopy space, important investigator-initiated clinical trial results anticipated in 2024 include VERITAS (NCT04250194), FROSTBITE2 (NCT05751278), and RELIANT (NCT05705544), among others. These research efforts complement industry-sponsored clinical trials (such as RheSolve, NCT04677465) and aim to emulate the extraordinary track record achieved in the field of pleural disease that has led to recently updated evidence-based guidelines for the management of challenging diseases like malignant pleural effusions, pleural space infections, and pneumothorax (Davies HE, et a l. JAMA. 2012 Jun 13;307[22]:2383-9, Mishra EK, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018 Feb 15;197[4]:502-8) (Rahman NM, et al. N Engl J Med. 2011 Aug 11;365[6]:518-26) (Hallifax RJ, et al. Lancet. 2020 Jul 4;396[10243]:39-49).

Ultimately, the rapidly evolving technological advancements in interventional pulmonology must be supported by research based on high-quality clinical trials, which will be contingent on appropriate trial funding requiring partnership with industry and federal funding agencies. Only through such collaboration can researchers design robust clinical trials based on complex methodology, which will advance patient care and lead to improved patient outcomes.

– Jennifer D. Duke, MD

Section Fellow-in-Training

– Fabien Maldonado, MD, MSc, FCCP

Section Member

Updates in evidence for rituximab in interstitial lung disease

DIFFUSE LUNG DISEASE AND LUNG TRANSPLANT NETWORK

Interstitial Lung Disease Section

Interstitial lung diseases (ILD) are a heterogeneous group of fibro-inflammatory disorders that can be progressive despite available therapies. The cornerstones of pharmacologic therapy include immunosuppression and antifibrotics.

Data on the use of rituximab, a B-lymphocyte-depleting monoclonal antibody, often utilized as rescue therapy in progressive and severe ILD, was limited until recently. The RECITAL trial reported the first randomized controlled trial investigating rituximab in severe or progressive autoimmune ILD. Though rituximab was not superior to cyclophosphamide, both agents improved forced vital capacity (FVC) at 24 weeks and respiratory-related quality of life. Rituximab was associated with less adverse events and lower corticosteroid exposure (Maher et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2023;11:45-54). In the DESIRES trial, patients with systemic sclerosis-associated ILD treated with rituximab had preservation of FVC at 24 and 48 weeks compared to placebo (Ebata et al. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021;3:e489-97; Lancet Rheumatol. 2022;4:e546-55). The EVER-ILD investigators compared mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) alone vs addition of rituximab in patients with autoimmune and idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP). Combination therapy was superior to MMF alone in improving FVC and progression-free survival. Combination regimen was well tolerated though nonserious viral and bacterial infections were more frequent (Mankikian et al. Eur Respir J. 2023;61[6]:2202071).

These findings, primarily in autoimmune ILD, are promising and provide clinicians with evidence for utilizing rituximab in patients with severe and progressive ILD. Nonetheless, they highlight the need for additional research and standardized guidance regarding the target population who stands to most benefit from rituximab.

–Tessy K. Paul, MD

Section Member-at-Large

–Tejaswini Kulkarni, MD, MBBS, FCCP

Section Chair

DIFFUSE LUNG DISEASE AND LUNG TRANSPLANT NETWORK

Interstitial Lung Disease Section

Interstitial lung diseases (ILD) are a heterogeneous group of fibro-inflammatory disorders that can be progressive despite available therapies. The cornerstones of pharmacologic therapy include immunosuppression and antifibrotics.

Data on the use of rituximab, a B-lymphocyte-depleting monoclonal antibody, often utilized as rescue therapy in progressive and severe ILD, was limited until recently. The RECITAL trial reported the first randomized controlled trial investigating rituximab in severe or progressive autoimmune ILD. Though rituximab was not superior to cyclophosphamide, both agents improved forced vital capacity (FVC) at 24 weeks and respiratory-related quality of life. Rituximab was associated with less adverse events and lower corticosteroid exposure (Maher et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2023;11:45-54). In the DESIRES trial, patients with systemic sclerosis-associated ILD treated with rituximab had preservation of FVC at 24 and 48 weeks compared to placebo (Ebata et al. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021;3:e489-97; Lancet Rheumatol. 2022;4:e546-55). The EVER-ILD investigators compared mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) alone vs addition of rituximab in patients with autoimmune and idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP). Combination therapy was superior to MMF alone in improving FVC and progression-free survival. Combination regimen was well tolerated though nonserious viral and bacterial infections were more frequent (Mankikian et al. Eur Respir J. 2023;61[6]:2202071).

These findings, primarily in autoimmune ILD, are promising and provide clinicians with evidence for utilizing rituximab in patients with severe and progressive ILD. Nonetheless, they highlight the need for additional research and standardized guidance regarding the target population who stands to most benefit from rituximab.

–Tessy K. Paul, MD

Section Member-at-Large

–Tejaswini Kulkarni, MD, MBBS, FCCP

Section Chair

DIFFUSE LUNG DISEASE AND LUNG TRANSPLANT NETWORK

Interstitial Lung Disease Section

Interstitial lung diseases (ILD) are a heterogeneous group of fibro-inflammatory disorders that can be progressive despite available therapies. The cornerstones of pharmacologic therapy include immunosuppression and antifibrotics.

Data on the use of rituximab, a B-lymphocyte-depleting monoclonal antibody, often utilized as rescue therapy in progressive and severe ILD, was limited until recently. The RECITAL trial reported the first randomized controlled trial investigating rituximab in severe or progressive autoimmune ILD. Though rituximab was not superior to cyclophosphamide, both agents improved forced vital capacity (FVC) at 24 weeks and respiratory-related quality of life. Rituximab was associated with less adverse events and lower corticosteroid exposure (Maher et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2023;11:45-54). In the DESIRES trial, patients with systemic sclerosis-associated ILD treated with rituximab had preservation of FVC at 24 and 48 weeks compared to placebo (Ebata et al. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021;3:e489-97; Lancet Rheumatol. 2022;4:e546-55). The EVER-ILD investigators compared mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) alone vs addition of rituximab in patients with autoimmune and idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP). Combination therapy was superior to MMF alone in improving FVC and progression-free survival. Combination regimen was well tolerated though nonserious viral and bacterial infections were more frequent (Mankikian et al. Eur Respir J. 2023;61[6]:2202071).

These findings, primarily in autoimmune ILD, are promising and provide clinicians with evidence for utilizing rituximab in patients with severe and progressive ILD. Nonetheless, they highlight the need for additional research and standardized guidance regarding the target population who stands to most benefit from rituximab.

–Tessy K. Paul, MD

Section Member-at-Large

–Tejaswini Kulkarni, MD, MBBS, FCCP

Section Chair

The emergence of postgraduate training programs for APPs in pulmonary and critical care

APP Intersection

Postgraduate training for advanced practice providers (APPs) has existed in one form or another since the genesis of the allied professions. They are typically referred to as residencies, fellowships, postgraduate programs, and transition-to-practice.

The desire and necessity for these programs has increased in the past decade with workforce changes; namely the increasing number of nurse practitioners (NPs) graduating with fewer years of experience at the bedside compared with previous eras, a similar decrease in patient contact hours for graduating PAs, the transition of physician colleagues from employers to employees and the subsequent change in priorities in training new graduate APPs, and resident work hour restrictions necessitating more APPs to staff inpatient units and work in various specialties.

The goal of these programs is to provide postgraduate training to physician assistants/associates (PAs) and NPs across myriad medical specialties to both newly graduated APPs and those looking to transition specialties. Current programs exist in family medicine, emergency medicine, urgent care, critical care medicine, pulmonary medicine, oncology, surgery, and various surgical subspecialties, to name a few. Program length is highly variable, though most programs advertise as lasting around 12 months, with varying ratios of clinical and didactic education. Postgraduate APP programs are largely advertise as salaried, benefitted positions, though usually at a rate below that of a so-called “direct hire” due to the protected learning time associated with the postgraduate training year.

Accreditation for these programs is still disjointed, although unifying efforts have been made as of late, and is currently available through the Advanced Practice Provider Fellowship Accreditation, Association of Postgraduate Physician Assistant Programs, ARC-PA, the Accreditation Commission for Education in Nursing, and the Consortium for Advanced Practice Providers. Other organizations, such as the Association of Post Graduate APRN Programs, host regular conferences to discuss the formulation of postgraduate APP education curricula and program development.

While accreditation offers guidance for fledgling programs, many utilize the standards published by the American College of Graduate Medical Education to ensure that appropriate clinical milestones are being met and that a common language among APPs and physicians who are involved in the evaluation of the postgraduate APP trainee is being used. Programs also seek to utilize other well-established curricula and certification programs published by various national and international organizations. A key distinction from physician postgraduate training is that there is currently no fiscal or legislative support for postgraduate APP programs; these issues have been cited as reasons for the limited scope and number of programs.

When starting APP Fellowship programs, it is important to consider why this would be beneficial to a specific division and health care organization. Usually, fellowship programs develop out of a need to train and retain APPs. It is no secret that turnover and retention of skilled APPs is a nationwide problem associated with significant costs to organizations. The ability to retain fellowship-trained APPs will result in cost savings due to the reduction in onboarding time and orientation costs, as these APP fellows finish their programs ready to be fully productive team members.

Additional considerations for the development of an APP fellowship include improving access to care and increasing the quality of the care provided. Fellowship programs encourage a smoother transition to practice by offering more support through education, closer evaluation, and frequent feedback, which improves competence and confidence of these providers. A supported APP is more likely to practice to the fullest extent of their license and have improved personal and professional satisfaction, leading to employee retention and better patient care.

When developing a budget for these types of programs, it is important to include the full-time equivalent (FTE) for the fellow, benefits, onboarding/licensure, simulations, and fellowship faculty costs.

Faculty compensation varies by institution but can include salary support, FTE reduction, and nonclinical appointments. Tracking metrics such as fellow billing, length of stay, and access to care during the fellowship year are helpful to highlight the benefit of these programs to the organization.

Initiating a program like those described may seem like a Herculean feat, but motivated individuals have been able to accomplish similar goals in both adequately and poorly resourced areas. For those aspiring to start a postgraduate APP program at their instruction, these authors suggest the following approach.

First, identify your institution’s need for such a program. Next, define your curriculum, evaluation process, and expectations. Then, create buy-in from stakeholders, including administrative and clinical personnel. Finally, focus on recruitment. Seeking accreditation may be challenging for new programs, but identifying the accreditation standard you plan to pursue early will pay dividends when the time comes for the program to apply. Those starting down this path should realistically expect an 18- to 24-month period between their first efforts and the start of the first class.

“APP Intersection” is a new quarterly column focusing on areas of interest for the entire chest medicine health care team.

APP Intersection

Postgraduate training for advanced practice providers (APPs) has existed in one form or another since the genesis of the allied professions. They are typically referred to as residencies, fellowships, postgraduate programs, and transition-to-practice.

The desire and necessity for these programs has increased in the past decade with workforce changes; namely the increasing number of nurse practitioners (NPs) graduating with fewer years of experience at the bedside compared with previous eras, a similar decrease in patient contact hours for graduating PAs, the transition of physician colleagues from employers to employees and the subsequent change in priorities in training new graduate APPs, and resident work hour restrictions necessitating more APPs to staff inpatient units and work in various specialties.

The goal of these programs is to provide postgraduate training to physician assistants/associates (PAs) and NPs across myriad medical specialties to both newly graduated APPs and those looking to transition specialties. Current programs exist in family medicine, emergency medicine, urgent care, critical care medicine, pulmonary medicine, oncology, surgery, and various surgical subspecialties, to name a few. Program length is highly variable, though most programs advertise as lasting around 12 months, with varying ratios of clinical and didactic education. Postgraduate APP programs are largely advertise as salaried, benefitted positions, though usually at a rate below that of a so-called “direct hire” due to the protected learning time associated with the postgraduate training year.

Accreditation for these programs is still disjointed, although unifying efforts have been made as of late, and is currently available through the Advanced Practice Provider Fellowship Accreditation, Association of Postgraduate Physician Assistant Programs, ARC-PA, the Accreditation Commission for Education in Nursing, and the Consortium for Advanced Practice Providers. Other organizations, such as the Association of Post Graduate APRN Programs, host regular conferences to discuss the formulation of postgraduate APP education curricula and program development.

While accreditation offers guidance for fledgling programs, many utilize the standards published by the American College of Graduate Medical Education to ensure that appropriate clinical milestones are being met and that a common language among APPs and physicians who are involved in the evaluation of the postgraduate APP trainee is being used. Programs also seek to utilize other well-established curricula and certification programs published by various national and international organizations. A key distinction from physician postgraduate training is that there is currently no fiscal or legislative support for postgraduate APP programs; these issues have been cited as reasons for the limited scope and number of programs.

When starting APP Fellowship programs, it is important to consider why this would be beneficial to a specific division and health care organization. Usually, fellowship programs develop out of a need to train and retain APPs. It is no secret that turnover and retention of skilled APPs is a nationwide problem associated with significant costs to organizations. The ability to retain fellowship-trained APPs will result in cost savings due to the reduction in onboarding time and orientation costs, as these APP fellows finish their programs ready to be fully productive team members.