User login

VRIC is May 3; Register Today

Register today for the May 3 Vascular Research Initiatives Conference.

The one-day meeting emphasizes emerging vascular science. It is considered a key event for meeting and reconnecting with vascular research collaborators.

New this year is the Alexander W. Clowes Distinguished Lecture, honoring the legacy of vascular surgeon-scientist Alec Clowes, M.D. William Sessa, Ph.D., of Yale University School of Medicine, will deliver the inaugural lecture, titled, "New Insights in Arteriogenesis and Blood Flow Control." The translational panel will discuss "Matrix Revolution: Vascular Repair and Regeneration," in a session co-sponsored with the International Society for Applied Cardiovascular Biology.

Four abstract sessions will focus on vascular endothelium and thrombosis, aortic and arterial pathology, stem cells and tissue engineering, and peripheral arterial disease. See the full program here.

Register today for the May 3 Vascular Research Initiatives Conference.

The one-day meeting emphasizes emerging vascular science. It is considered a key event for meeting and reconnecting with vascular research collaborators.

New this year is the Alexander W. Clowes Distinguished Lecture, honoring the legacy of vascular surgeon-scientist Alec Clowes, M.D. William Sessa, Ph.D., of Yale University School of Medicine, will deliver the inaugural lecture, titled, "New Insights in Arteriogenesis and Blood Flow Control." The translational panel will discuss "Matrix Revolution: Vascular Repair and Regeneration," in a session co-sponsored with the International Society for Applied Cardiovascular Biology.

Four abstract sessions will focus on vascular endothelium and thrombosis, aortic and arterial pathology, stem cells and tissue engineering, and peripheral arterial disease. See the full program here.

Register today for the May 3 Vascular Research Initiatives Conference.

The one-day meeting emphasizes emerging vascular science. It is considered a key event for meeting and reconnecting with vascular research collaborators.

New this year is the Alexander W. Clowes Distinguished Lecture, honoring the legacy of vascular surgeon-scientist Alec Clowes, M.D. William Sessa, Ph.D., of Yale University School of Medicine, will deliver the inaugural lecture, titled, "New Insights in Arteriogenesis and Blood Flow Control." The translational panel will discuss "Matrix Revolution: Vascular Repair and Regeneration," in a session co-sponsored with the International Society for Applied Cardiovascular Biology.

Four abstract sessions will focus on vascular endothelium and thrombosis, aortic and arterial pathology, stem cells and tissue engineering, and peripheral arterial disease. See the full program here.

Purchase On-Demand Library at VAM Registration

Don't forget you can take VAM home with you! You can pre-purchase all VAM PowerPoint slides, audio and a limited selection of assorted videotaped sessions in the On-Demand Library.

This valuable resource of almost 400 individual presentations will be available shortly following the meeting’s conclusion, with access continued for up to one year.

Cost is just $99. For those who have already registered and now want to add the On-Demand Library, simply return to the registration page and add the library separately.

Register here for VAM and make housing reservations here.

Don't forget you can take VAM home with you! You can pre-purchase all VAM PowerPoint slides, audio and a limited selection of assorted videotaped sessions in the On-Demand Library.

This valuable resource of almost 400 individual presentations will be available shortly following the meeting’s conclusion, with access continued for up to one year.

Cost is just $99. For those who have already registered and now want to add the On-Demand Library, simply return to the registration page and add the library separately.

Register here for VAM and make housing reservations here.

Don't forget you can take VAM home with you! You can pre-purchase all VAM PowerPoint slides, audio and a limited selection of assorted videotaped sessions in the On-Demand Library.

This valuable resource of almost 400 individual presentations will be available shortly following the meeting’s conclusion, with access continued for up to one year.

Cost is just $99. For those who have already registered and now want to add the On-Demand Library, simply return to the registration page and add the library separately.

Register here for VAM and make housing reservations here.

Visit some of Toronto’s best during CHEST 2017

Get ready to visit the metropolitan hub of Canada. Explore new grounds with the chest medicine community for current pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine topics presented by world-renowned faculty in a variety of innovative instruction formats.

You will have access to our cutting-edge education, Oct 28 - Nov 1, but don’t forget to take advantage of all that Toronto has to offer.

Food

Le Petit Dejeune offers an ever-changing menu that ranges from less expensive items, like soup, sandwiches, and salads, to some pricier stuffed crepes, quiche, and eggs florentine. While most Sundays, Saving Grace is packed, but there’s only a 15-minute wait, and the atmosphere is quite pleasant. Looking for the perfect cinnamon bun? Rosen’s Cinnamon Buns is the place to go. But you have to look closely for the bakery’s name, since the sign above the window still advertises the hair salon that used to reside in the same spot!

Nature parks

One of the city’s largest and oldest parks, High Park is Toronto’s version of New York City’s Central Park. There’s plenty to enjoy, such as Grenadier Pond, numerous ravine-based hiking trails, playgrounds, athletic areas, restaurants, a museum, and even a zoo!

If you want a different type of nature excursion, there is always beautiful Niagara Falls, Ontario, which is just a short drive from Toronto. Don’t miss seeing the Tesla monument in Queen Victoria Park, or go 10 minutes north of the Falls to the Botanical Gardens, home to the Butterfly Conservatory with over 2,000 butterflies.

Relaxation

After eventful days of absorbing all the new science CHEST 2017 has to offer, you may want to relax your mind and body. Elmwood spa, located in downtown Toronto, is where “four spacious floors of treatment and renewal options mean that Elmwood Spa can provide the convenience and flexibility to cater to demanding schedules,” according to Elmwood.

Learn more about Toronto opportunities at blogTO.com, and find out more about CHEST 2017 at chestmeeting.chestnet.org.

Get ready to visit the metropolitan hub of Canada. Explore new grounds with the chest medicine community for current pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine topics presented by world-renowned faculty in a variety of innovative instruction formats.

You will have access to our cutting-edge education, Oct 28 - Nov 1, but don’t forget to take advantage of all that Toronto has to offer.

Food

Le Petit Dejeune offers an ever-changing menu that ranges from less expensive items, like soup, sandwiches, and salads, to some pricier stuffed crepes, quiche, and eggs florentine. While most Sundays, Saving Grace is packed, but there’s only a 15-minute wait, and the atmosphere is quite pleasant. Looking for the perfect cinnamon bun? Rosen’s Cinnamon Buns is the place to go. But you have to look closely for the bakery’s name, since the sign above the window still advertises the hair salon that used to reside in the same spot!

Nature parks

One of the city’s largest and oldest parks, High Park is Toronto’s version of New York City’s Central Park. There’s plenty to enjoy, such as Grenadier Pond, numerous ravine-based hiking trails, playgrounds, athletic areas, restaurants, a museum, and even a zoo!

If you want a different type of nature excursion, there is always beautiful Niagara Falls, Ontario, which is just a short drive from Toronto. Don’t miss seeing the Tesla monument in Queen Victoria Park, or go 10 minutes north of the Falls to the Botanical Gardens, home to the Butterfly Conservatory with over 2,000 butterflies.

Relaxation

After eventful days of absorbing all the new science CHEST 2017 has to offer, you may want to relax your mind and body. Elmwood spa, located in downtown Toronto, is where “four spacious floors of treatment and renewal options mean that Elmwood Spa can provide the convenience and flexibility to cater to demanding schedules,” according to Elmwood.

Learn more about Toronto opportunities at blogTO.com, and find out more about CHEST 2017 at chestmeeting.chestnet.org.

Get ready to visit the metropolitan hub of Canada. Explore new grounds with the chest medicine community for current pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine topics presented by world-renowned faculty in a variety of innovative instruction formats.

You will have access to our cutting-edge education, Oct 28 - Nov 1, but don’t forget to take advantage of all that Toronto has to offer.

Food

Le Petit Dejeune offers an ever-changing menu that ranges from less expensive items, like soup, sandwiches, and salads, to some pricier stuffed crepes, quiche, and eggs florentine. While most Sundays, Saving Grace is packed, but there’s only a 15-minute wait, and the atmosphere is quite pleasant. Looking for the perfect cinnamon bun? Rosen’s Cinnamon Buns is the place to go. But you have to look closely for the bakery’s name, since the sign above the window still advertises the hair salon that used to reside in the same spot!

Nature parks

One of the city’s largest and oldest parks, High Park is Toronto’s version of New York City’s Central Park. There’s plenty to enjoy, such as Grenadier Pond, numerous ravine-based hiking trails, playgrounds, athletic areas, restaurants, a museum, and even a zoo!

If you want a different type of nature excursion, there is always beautiful Niagara Falls, Ontario, which is just a short drive from Toronto. Don’t miss seeing the Tesla monument in Queen Victoria Park, or go 10 minutes north of the Falls to the Botanical Gardens, home to the Butterfly Conservatory with over 2,000 butterflies.

Relaxation

After eventful days of absorbing all the new science CHEST 2017 has to offer, you may want to relax your mind and body. Elmwood spa, located in downtown Toronto, is where “four spacious floors of treatment and renewal options mean that Elmwood Spa can provide the convenience and flexibility to cater to demanding schedules,” according to Elmwood.

Learn more about Toronto opportunities at blogTO.com, and find out more about CHEST 2017 at chestmeeting.chestnet.org.

Pulmonary Perspectives: Ensuring quality for EBUS bronchoscopy with varying levels of practitioner experience

Dr. Mahajan and colleagues present a compelling case for requiring minimum standards to perform an EBUS-guided bronchoscopy. Their opinion piece epitomizes the classic tension between physicians with advanced training and those who can only have practice-based training. A middle ground may exist, as perhaps competence could be achieved by simulation, clinical cases performed, and observation by a regional expert? Physicians in practice must have a pathway to adopt new technology whether it is thoracic ultrasound or endobronchial ultrasound, but it must be done in a safe manner. As a referring physician, I would only send my patients who required mediastinal staging to a pulmonologist who I knew performed EBUS regularly.

Nitin Puri, MD, FCCP

Endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) bronchoscopy is a tool that has transformed the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. Through real-time ultrasound imaging, EBUS provides clear images of lymph nodes and proximal lung masses that can be adequately sampled through transbronchial needle aspiration. EBUS is a minimally invasive, outpatient procedure that can also be used for diagnosing benign disease within the chest. Large studies investigating the use of EBUS for mediastinal staging have shown the procedure to be highly sensitive and specific while harboring an excellent safety profile.1 As a result, EBUS has essentially replaced mediastinoscopy for the staging of lung cancer.

EBUS bronchoscopy was primarily offered at major academic centers when first released and was performed by physicians who were formally trained in the procedure during interventional pulmonology or thoracic surgery fellowships. Over time, the tool has been adopted by established general pulmonologists without formal training in EBUS. Some of these pulmonologists only develop their skills by attending 1- to 2-day courses, which is insufficient supervision to become competent in this important procedure.

An ongoing debate continues as to how many supervised EBUS bronchoscopies should be performed prior to being considered proficient.2 As procedural competence has been associated with the number of EBUS procedures performed, the learning curve required to master EBUS is an important component of proficiency. While most consider learning curves to be variable, evidence produced by Fernandez-Villar and colleagues revealed that EBUS performance continues to improve up to 120 procedures.3 This analysis was performed in unselected consecutive patients based on diagnostic yield, procedure length, number of lymph nodes passes performed in order to obtain adequate samples, and the number of lymph nodes studied per patient. The learning curve was evaluated based on consecutive groups of 20 patients, the number of adequate samples obtained, and the diagnostic accuracy. Their results indicated that the diagnostic effectiveness of EBUS-TBNA improves with increasing number of procedures performed, allowing for access to a greater number of lymph nodes without necessarily increasing the length of the procedure, and by reducing the number of punctures at each nodal station. Based on their results, the first 20 procedures performed yielded a 70% accuracy, 21 to 40 procedures performed resulted in 81.8% accuracy, 41 to 60 procedures performed resulted in 83.3% accuracy, 61 to 80 procedures performed resulted in 89.8% accuracy, 81 to 100 procedures performed resulted in 90.5% accuracy, and 101 to 120 procedures performed resulted in 94.5% accuracy.

While the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) both recommend a minimum number of 40 to 50 supervised EBUS bronchoscopies prior to performing the procedure independently, along with 20 procedures per year for maintenance of competency, most institutions do not track the number of EBUS procedures performed and they do not follow the ATS or CHEST recommendations.4,5 As a result, a number of physicians are independently performing EBUS without adequate experience, resulting in possibly poor quality care. Unfortunately, some short courses, intended to generate interest and encourage attendees to pursue further training, are mistakenly assumed to be sufficient by the novice user.

As the number of interventional pulmonary fellowships continues to expand, the growing number of subspecialized pulmonologists with extensive training in EBUS grows. During a dedicated interventional pulmonary fellowship, fellows perform well above the number of EBUS bronchoscopies suggested by the ATS and CHEST in a single year. Recently published accreditation guidelines require a minimum of 100 cases per interventional pulmonary fellow.6 These fellowship-trained interventional pulmonologists are then tested to become board-certified in a wide array of minimally invasive procedures, including EBUS. As a result, a model has developed where both board-certified interventional pulmonologists with extensive training in EBUS and general pulmonologists not meeting ATS or CHEST minimum requirements practice at the same institution. Proponents of a more liberal access to credentialing in EBUS have suggested that adhering to competency requirements constitutes a “barrier to entry” in which incumbent practitioners benefit from limiting competition. However, like any other regulatory metric, the rationale is to prevent asymmetric information. In this example, the physician knows more than the patient. The patient cannot make an informed decision on which provider to choose and what are the minimum requirements that are likely to produce the most useful information (ie, complete staging). For these reasons, it is imperative that regulations protect the patient.

Without question, EBUS bronchoscopy should not be performed only by board-certified interventional pulmonologists. Instead, hospital credentialing committees should adhere to both the ATS and CHEST recommendations for the number of supervised cases necessary prior to performing EBUS independently. As EBUS use continues to grow, fellows in 3- or 4-year pulmonary and critical care fellowships will be likely capable of meeting the minimal number of observed cases, but, if these numbers are not achieved, additional training should be required. Understandably, this could be challenging for physicians who are unable to take time away from their practice to gain this training. However, if these numbers cannot be met, credentialing requirements should be enforced.

Even more challenging than establishing quality measures for EBUS, is to ensure the highest level of care delivery for patients when there exist multiple levels of experience in the same institution. Undoubtedly, patients undergoing EBUS bronchoscopy, or any procedure for that matter, would want the most skilled physician who has attained certification in the procedure. Unfortunately, no formal certification of EBUS exists outside of gaining board certification in interventional pulmonology. To ensure excellence in care, physicians performing EBUS should be involved in quality improvement initiatives and review pathologic yields along with complications on a regular basis in a group setting. Unlike emergency interventions, EBUS bronchoscopy is an entirely elective procedure.

The advent of EBUS bronchoscopy has revolutionized the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. As use of EBUS continues to become more widespread, the incidence of high volume and low volume proceduralists will become a more commonly encountered scenario. Guidelines have been set by the professional pulmonary societies based on the data and observations available. At the local level, stringent guidelines need to be established by hospitals to ensure a high level of quality with appropriate oversight. Patients undergoing EBUS deserve a physician who is skilled in the procedure and has performed at least the minimum number of procedures to provide the adequate care.

Dr. Mahajan is Medical Director, Interventional Pulmonology, Inova Heart and Vascular Institute - Inova Fairfax Hospital, and Associate Professor, Virginia Commonwealth Medical School; Dr. Khandhar is Medical Director, Thoracic Surgery, Inova Heart and Vascular Institute - Inova Fairfax Hospital, and Assistant Clinical Professor, Virginia Commonwealth Medical School; Falls Church, VA. Dr. Folch is Co-Director, Interventional Pulmonology Chief, Complex Chest Diseases Center, Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA.

References

1. Gomez M, Silvestri GA. Endobronchial ultrasound for the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6(2):180-186.

2. Folch E, Majid A. Point: Are >50 Supervised Procedures Required to Develop Competency in Performing Endobronchial Ultrasound-Guided Transbronchial Needle Aspiration for Mediastinal Staging? Yes. Chest. 2013;143(4):888-891.

3. Fernandez-Villar A, Leiro-Fernandez V, Botana-Rial M, Represas-Represas C, Nunez-Delgado M. The endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle biopsy learning curve for mediastinal and hilar lymph node diagnosis. Chest. 2012; 141(1):278-279.

4. Ernst A, Silvestri GA, Johnstone D. Interventional pulmonary procedures: Guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians. Chest. 2003;123(5):1693-1717.

5. Bolliger CT, Mathur PN, Beamis JF, et al. ERS/ATS statement on interventional pulmonology. European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society. Eur Respir J. 2002;19(2):356-373.

6. Mullon JJ, Burkhart KM, Silvestri G. Interventional Pulmonology Fellowship Accreditation Standards: Executive Summary of the Multi-society Interventional Pulmonology Fellowship Accreditation Committee. Chest. 2017. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2017.01.024.

Dr. Mahajan and colleagues present a compelling case for requiring minimum standards to perform an EBUS-guided bronchoscopy. Their opinion piece epitomizes the classic tension between physicians with advanced training and those who can only have practice-based training. A middle ground may exist, as perhaps competence could be achieved by simulation, clinical cases performed, and observation by a regional expert? Physicians in practice must have a pathway to adopt new technology whether it is thoracic ultrasound or endobronchial ultrasound, but it must be done in a safe manner. As a referring physician, I would only send my patients who required mediastinal staging to a pulmonologist who I knew performed EBUS regularly.

Nitin Puri, MD, FCCP

Endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) bronchoscopy is a tool that has transformed the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. Through real-time ultrasound imaging, EBUS provides clear images of lymph nodes and proximal lung masses that can be adequately sampled through transbronchial needle aspiration. EBUS is a minimally invasive, outpatient procedure that can also be used for diagnosing benign disease within the chest. Large studies investigating the use of EBUS for mediastinal staging have shown the procedure to be highly sensitive and specific while harboring an excellent safety profile.1 As a result, EBUS has essentially replaced mediastinoscopy for the staging of lung cancer.

EBUS bronchoscopy was primarily offered at major academic centers when first released and was performed by physicians who were formally trained in the procedure during interventional pulmonology or thoracic surgery fellowships. Over time, the tool has been adopted by established general pulmonologists without formal training in EBUS. Some of these pulmonologists only develop their skills by attending 1- to 2-day courses, which is insufficient supervision to become competent in this important procedure.

An ongoing debate continues as to how many supervised EBUS bronchoscopies should be performed prior to being considered proficient.2 As procedural competence has been associated with the number of EBUS procedures performed, the learning curve required to master EBUS is an important component of proficiency. While most consider learning curves to be variable, evidence produced by Fernandez-Villar and colleagues revealed that EBUS performance continues to improve up to 120 procedures.3 This analysis was performed in unselected consecutive patients based on diagnostic yield, procedure length, number of lymph nodes passes performed in order to obtain adequate samples, and the number of lymph nodes studied per patient. The learning curve was evaluated based on consecutive groups of 20 patients, the number of adequate samples obtained, and the diagnostic accuracy. Their results indicated that the diagnostic effectiveness of EBUS-TBNA improves with increasing number of procedures performed, allowing for access to a greater number of lymph nodes without necessarily increasing the length of the procedure, and by reducing the number of punctures at each nodal station. Based on their results, the first 20 procedures performed yielded a 70% accuracy, 21 to 40 procedures performed resulted in 81.8% accuracy, 41 to 60 procedures performed resulted in 83.3% accuracy, 61 to 80 procedures performed resulted in 89.8% accuracy, 81 to 100 procedures performed resulted in 90.5% accuracy, and 101 to 120 procedures performed resulted in 94.5% accuracy.

While the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) both recommend a minimum number of 40 to 50 supervised EBUS bronchoscopies prior to performing the procedure independently, along with 20 procedures per year for maintenance of competency, most institutions do not track the number of EBUS procedures performed and they do not follow the ATS or CHEST recommendations.4,5 As a result, a number of physicians are independently performing EBUS without adequate experience, resulting in possibly poor quality care. Unfortunately, some short courses, intended to generate interest and encourage attendees to pursue further training, are mistakenly assumed to be sufficient by the novice user.

As the number of interventional pulmonary fellowships continues to expand, the growing number of subspecialized pulmonologists with extensive training in EBUS grows. During a dedicated interventional pulmonary fellowship, fellows perform well above the number of EBUS bronchoscopies suggested by the ATS and CHEST in a single year. Recently published accreditation guidelines require a minimum of 100 cases per interventional pulmonary fellow.6 These fellowship-trained interventional pulmonologists are then tested to become board-certified in a wide array of minimally invasive procedures, including EBUS. As a result, a model has developed where both board-certified interventional pulmonologists with extensive training in EBUS and general pulmonologists not meeting ATS or CHEST minimum requirements practice at the same institution. Proponents of a more liberal access to credentialing in EBUS have suggested that adhering to competency requirements constitutes a “barrier to entry” in which incumbent practitioners benefit from limiting competition. However, like any other regulatory metric, the rationale is to prevent asymmetric information. In this example, the physician knows more than the patient. The patient cannot make an informed decision on which provider to choose and what are the minimum requirements that are likely to produce the most useful information (ie, complete staging). For these reasons, it is imperative that regulations protect the patient.

Without question, EBUS bronchoscopy should not be performed only by board-certified interventional pulmonologists. Instead, hospital credentialing committees should adhere to both the ATS and CHEST recommendations for the number of supervised cases necessary prior to performing EBUS independently. As EBUS use continues to grow, fellows in 3- or 4-year pulmonary and critical care fellowships will be likely capable of meeting the minimal number of observed cases, but, if these numbers are not achieved, additional training should be required. Understandably, this could be challenging for physicians who are unable to take time away from their practice to gain this training. However, if these numbers cannot be met, credentialing requirements should be enforced.

Even more challenging than establishing quality measures for EBUS, is to ensure the highest level of care delivery for patients when there exist multiple levels of experience in the same institution. Undoubtedly, patients undergoing EBUS bronchoscopy, or any procedure for that matter, would want the most skilled physician who has attained certification in the procedure. Unfortunately, no formal certification of EBUS exists outside of gaining board certification in interventional pulmonology. To ensure excellence in care, physicians performing EBUS should be involved in quality improvement initiatives and review pathologic yields along with complications on a regular basis in a group setting. Unlike emergency interventions, EBUS bronchoscopy is an entirely elective procedure.

The advent of EBUS bronchoscopy has revolutionized the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. As use of EBUS continues to become more widespread, the incidence of high volume and low volume proceduralists will become a more commonly encountered scenario. Guidelines have been set by the professional pulmonary societies based on the data and observations available. At the local level, stringent guidelines need to be established by hospitals to ensure a high level of quality with appropriate oversight. Patients undergoing EBUS deserve a physician who is skilled in the procedure and has performed at least the minimum number of procedures to provide the adequate care.

Dr. Mahajan is Medical Director, Interventional Pulmonology, Inova Heart and Vascular Institute - Inova Fairfax Hospital, and Associate Professor, Virginia Commonwealth Medical School; Dr. Khandhar is Medical Director, Thoracic Surgery, Inova Heart and Vascular Institute - Inova Fairfax Hospital, and Assistant Clinical Professor, Virginia Commonwealth Medical School; Falls Church, VA. Dr. Folch is Co-Director, Interventional Pulmonology Chief, Complex Chest Diseases Center, Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA.

References

1. Gomez M, Silvestri GA. Endobronchial ultrasound for the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6(2):180-186.

2. Folch E, Majid A. Point: Are >50 Supervised Procedures Required to Develop Competency in Performing Endobronchial Ultrasound-Guided Transbronchial Needle Aspiration for Mediastinal Staging? Yes. Chest. 2013;143(4):888-891.

3. Fernandez-Villar A, Leiro-Fernandez V, Botana-Rial M, Represas-Represas C, Nunez-Delgado M. The endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle biopsy learning curve for mediastinal and hilar lymph node diagnosis. Chest. 2012; 141(1):278-279.

4. Ernst A, Silvestri GA, Johnstone D. Interventional pulmonary procedures: Guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians. Chest. 2003;123(5):1693-1717.

5. Bolliger CT, Mathur PN, Beamis JF, et al. ERS/ATS statement on interventional pulmonology. European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society. Eur Respir J. 2002;19(2):356-373.

6. Mullon JJ, Burkhart KM, Silvestri G. Interventional Pulmonology Fellowship Accreditation Standards: Executive Summary of the Multi-society Interventional Pulmonology Fellowship Accreditation Committee. Chest. 2017. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2017.01.024.

Dr. Mahajan and colleagues present a compelling case for requiring minimum standards to perform an EBUS-guided bronchoscopy. Their opinion piece epitomizes the classic tension between physicians with advanced training and those who can only have practice-based training. A middle ground may exist, as perhaps competence could be achieved by simulation, clinical cases performed, and observation by a regional expert? Physicians in practice must have a pathway to adopt new technology whether it is thoracic ultrasound or endobronchial ultrasound, but it must be done in a safe manner. As a referring physician, I would only send my patients who required mediastinal staging to a pulmonologist who I knew performed EBUS regularly.

Nitin Puri, MD, FCCP

Endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) bronchoscopy is a tool that has transformed the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. Through real-time ultrasound imaging, EBUS provides clear images of lymph nodes and proximal lung masses that can be adequately sampled through transbronchial needle aspiration. EBUS is a minimally invasive, outpatient procedure that can also be used for diagnosing benign disease within the chest. Large studies investigating the use of EBUS for mediastinal staging have shown the procedure to be highly sensitive and specific while harboring an excellent safety profile.1 As a result, EBUS has essentially replaced mediastinoscopy for the staging of lung cancer.

EBUS bronchoscopy was primarily offered at major academic centers when first released and was performed by physicians who were formally trained in the procedure during interventional pulmonology or thoracic surgery fellowships. Over time, the tool has been adopted by established general pulmonologists without formal training in EBUS. Some of these pulmonologists only develop their skills by attending 1- to 2-day courses, which is insufficient supervision to become competent in this important procedure.

An ongoing debate continues as to how many supervised EBUS bronchoscopies should be performed prior to being considered proficient.2 As procedural competence has been associated with the number of EBUS procedures performed, the learning curve required to master EBUS is an important component of proficiency. While most consider learning curves to be variable, evidence produced by Fernandez-Villar and colleagues revealed that EBUS performance continues to improve up to 120 procedures.3 This analysis was performed in unselected consecutive patients based on diagnostic yield, procedure length, number of lymph nodes passes performed in order to obtain adequate samples, and the number of lymph nodes studied per patient. The learning curve was evaluated based on consecutive groups of 20 patients, the number of adequate samples obtained, and the diagnostic accuracy. Their results indicated that the diagnostic effectiveness of EBUS-TBNA improves with increasing number of procedures performed, allowing for access to a greater number of lymph nodes without necessarily increasing the length of the procedure, and by reducing the number of punctures at each nodal station. Based on their results, the first 20 procedures performed yielded a 70% accuracy, 21 to 40 procedures performed resulted in 81.8% accuracy, 41 to 60 procedures performed resulted in 83.3% accuracy, 61 to 80 procedures performed resulted in 89.8% accuracy, 81 to 100 procedures performed resulted in 90.5% accuracy, and 101 to 120 procedures performed resulted in 94.5% accuracy.

While the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) both recommend a minimum number of 40 to 50 supervised EBUS bronchoscopies prior to performing the procedure independently, along with 20 procedures per year for maintenance of competency, most institutions do not track the number of EBUS procedures performed and they do not follow the ATS or CHEST recommendations.4,5 As a result, a number of physicians are independently performing EBUS without adequate experience, resulting in possibly poor quality care. Unfortunately, some short courses, intended to generate interest and encourage attendees to pursue further training, are mistakenly assumed to be sufficient by the novice user.

As the number of interventional pulmonary fellowships continues to expand, the growing number of subspecialized pulmonologists with extensive training in EBUS grows. During a dedicated interventional pulmonary fellowship, fellows perform well above the number of EBUS bronchoscopies suggested by the ATS and CHEST in a single year. Recently published accreditation guidelines require a minimum of 100 cases per interventional pulmonary fellow.6 These fellowship-trained interventional pulmonologists are then tested to become board-certified in a wide array of minimally invasive procedures, including EBUS. As a result, a model has developed where both board-certified interventional pulmonologists with extensive training in EBUS and general pulmonologists not meeting ATS or CHEST minimum requirements practice at the same institution. Proponents of a more liberal access to credentialing in EBUS have suggested that adhering to competency requirements constitutes a “barrier to entry” in which incumbent practitioners benefit from limiting competition. However, like any other regulatory metric, the rationale is to prevent asymmetric information. In this example, the physician knows more than the patient. The patient cannot make an informed decision on which provider to choose and what are the minimum requirements that are likely to produce the most useful information (ie, complete staging). For these reasons, it is imperative that regulations protect the patient.

Without question, EBUS bronchoscopy should not be performed only by board-certified interventional pulmonologists. Instead, hospital credentialing committees should adhere to both the ATS and CHEST recommendations for the number of supervised cases necessary prior to performing EBUS independently. As EBUS use continues to grow, fellows in 3- or 4-year pulmonary and critical care fellowships will be likely capable of meeting the minimal number of observed cases, but, if these numbers are not achieved, additional training should be required. Understandably, this could be challenging for physicians who are unable to take time away from their practice to gain this training. However, if these numbers cannot be met, credentialing requirements should be enforced.

Even more challenging than establishing quality measures for EBUS, is to ensure the highest level of care delivery for patients when there exist multiple levels of experience in the same institution. Undoubtedly, patients undergoing EBUS bronchoscopy, or any procedure for that matter, would want the most skilled physician who has attained certification in the procedure. Unfortunately, no formal certification of EBUS exists outside of gaining board certification in interventional pulmonology. To ensure excellence in care, physicians performing EBUS should be involved in quality improvement initiatives and review pathologic yields along with complications on a regular basis in a group setting. Unlike emergency interventions, EBUS bronchoscopy is an entirely elective procedure.

The advent of EBUS bronchoscopy has revolutionized the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. As use of EBUS continues to become more widespread, the incidence of high volume and low volume proceduralists will become a more commonly encountered scenario. Guidelines have been set by the professional pulmonary societies based on the data and observations available. At the local level, stringent guidelines need to be established by hospitals to ensure a high level of quality with appropriate oversight. Patients undergoing EBUS deserve a physician who is skilled in the procedure and has performed at least the minimum number of procedures to provide the adequate care.

Dr. Mahajan is Medical Director, Interventional Pulmonology, Inova Heart and Vascular Institute - Inova Fairfax Hospital, and Associate Professor, Virginia Commonwealth Medical School; Dr. Khandhar is Medical Director, Thoracic Surgery, Inova Heart and Vascular Institute - Inova Fairfax Hospital, and Assistant Clinical Professor, Virginia Commonwealth Medical School; Falls Church, VA. Dr. Folch is Co-Director, Interventional Pulmonology Chief, Complex Chest Diseases Center, Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA.

References

1. Gomez M, Silvestri GA. Endobronchial ultrasound for the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6(2):180-186.

2. Folch E, Majid A. Point: Are >50 Supervised Procedures Required to Develop Competency in Performing Endobronchial Ultrasound-Guided Transbronchial Needle Aspiration for Mediastinal Staging? Yes. Chest. 2013;143(4):888-891.

3. Fernandez-Villar A, Leiro-Fernandez V, Botana-Rial M, Represas-Represas C, Nunez-Delgado M. The endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle biopsy learning curve for mediastinal and hilar lymph node diagnosis. Chest. 2012; 141(1):278-279.

4. Ernst A, Silvestri GA, Johnstone D. Interventional pulmonary procedures: Guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians. Chest. 2003;123(5):1693-1717.

5. Bolliger CT, Mathur PN, Beamis JF, et al. ERS/ATS statement on interventional pulmonology. European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society. Eur Respir J. 2002;19(2):356-373.

6. Mullon JJ, Burkhart KM, Silvestri G. Interventional Pulmonology Fellowship Accreditation Standards: Executive Summary of the Multi-society Interventional Pulmonology Fellowship Accreditation Committee. Chest. 2017. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2017.01.024.

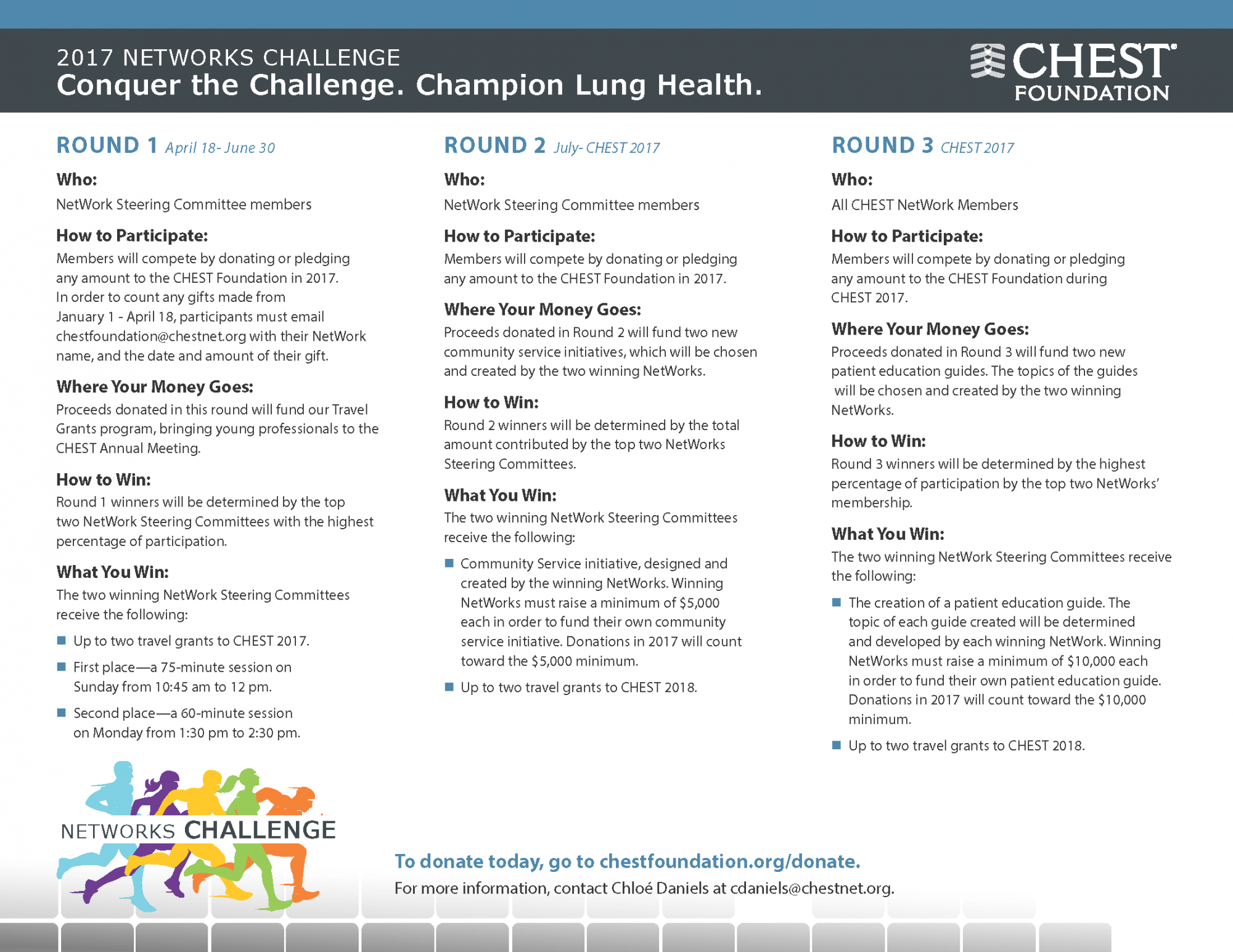

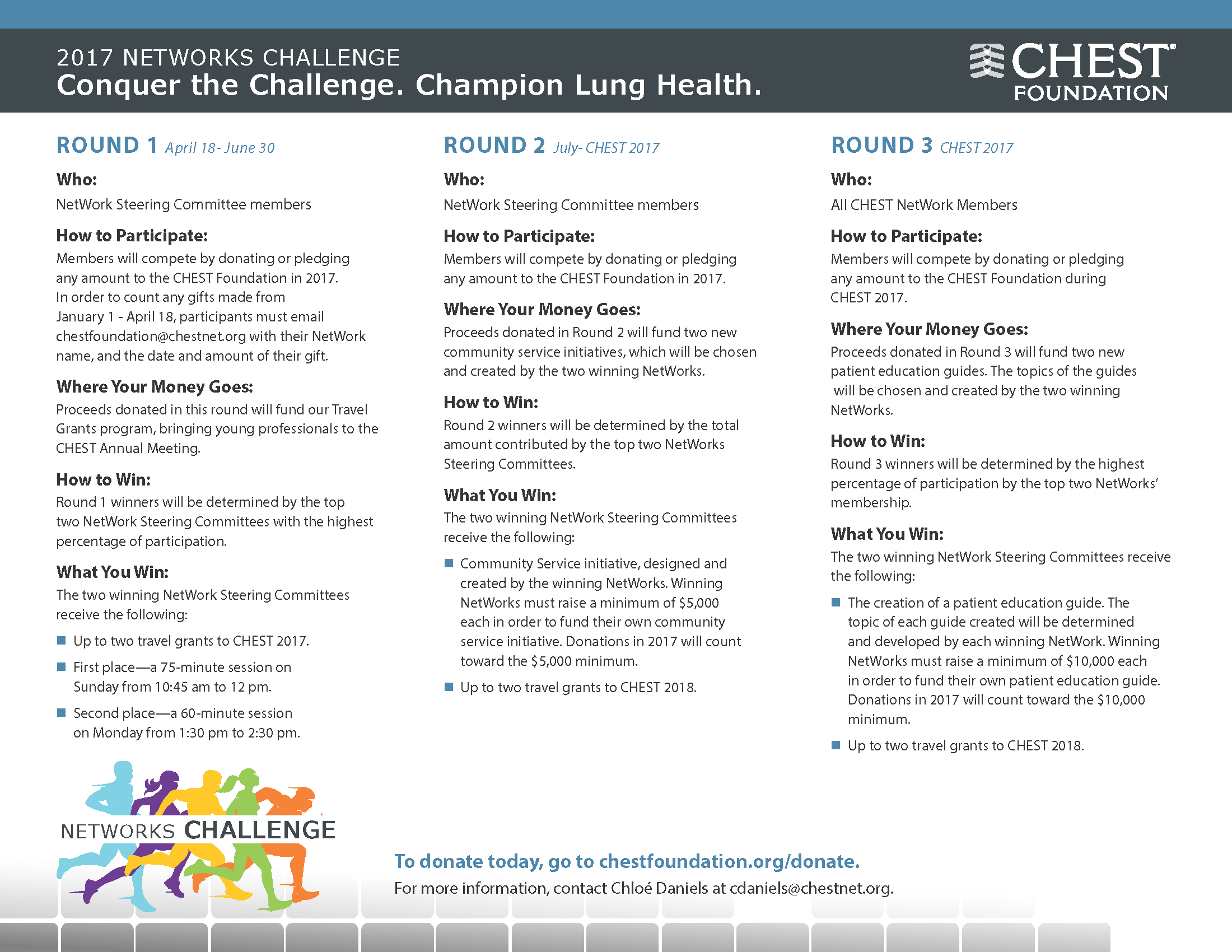

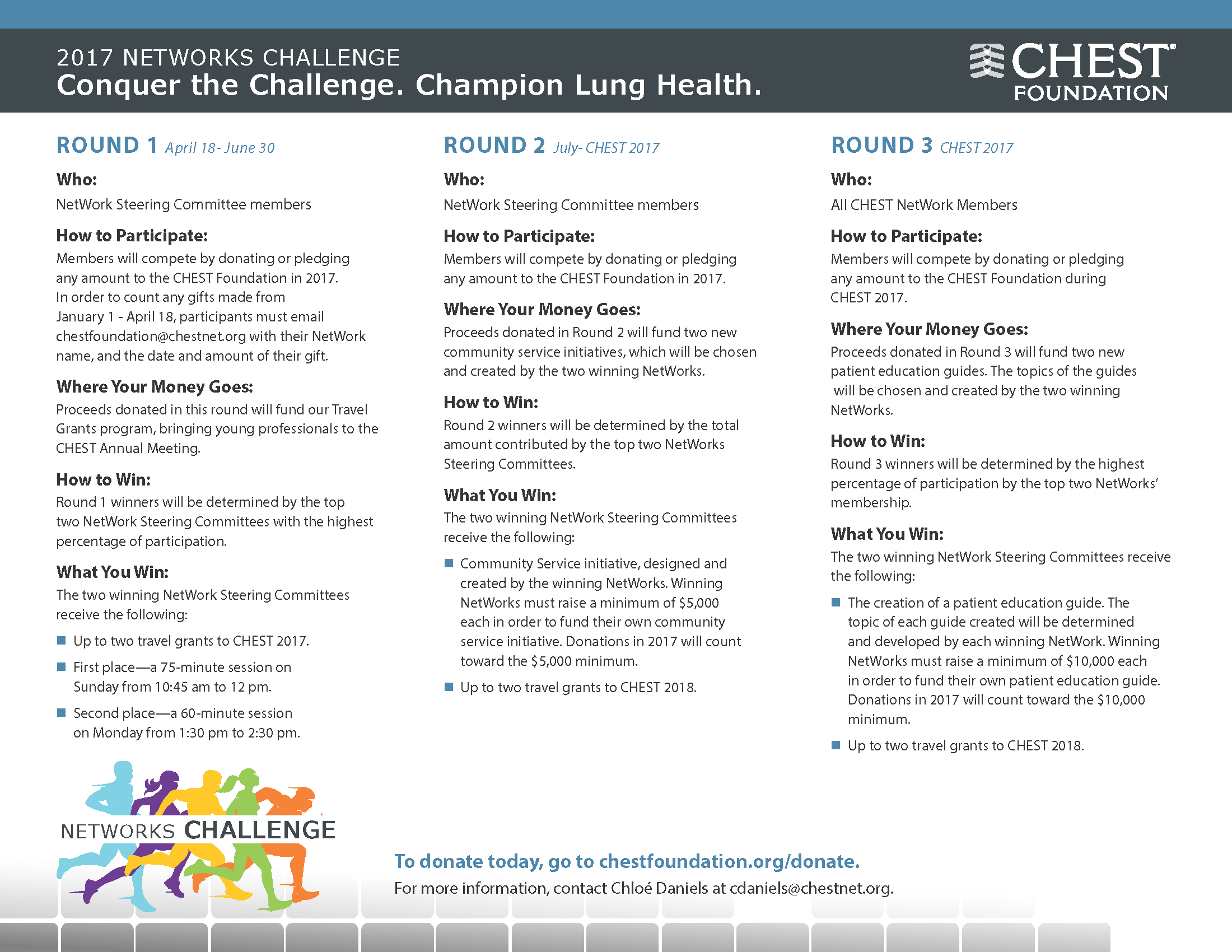

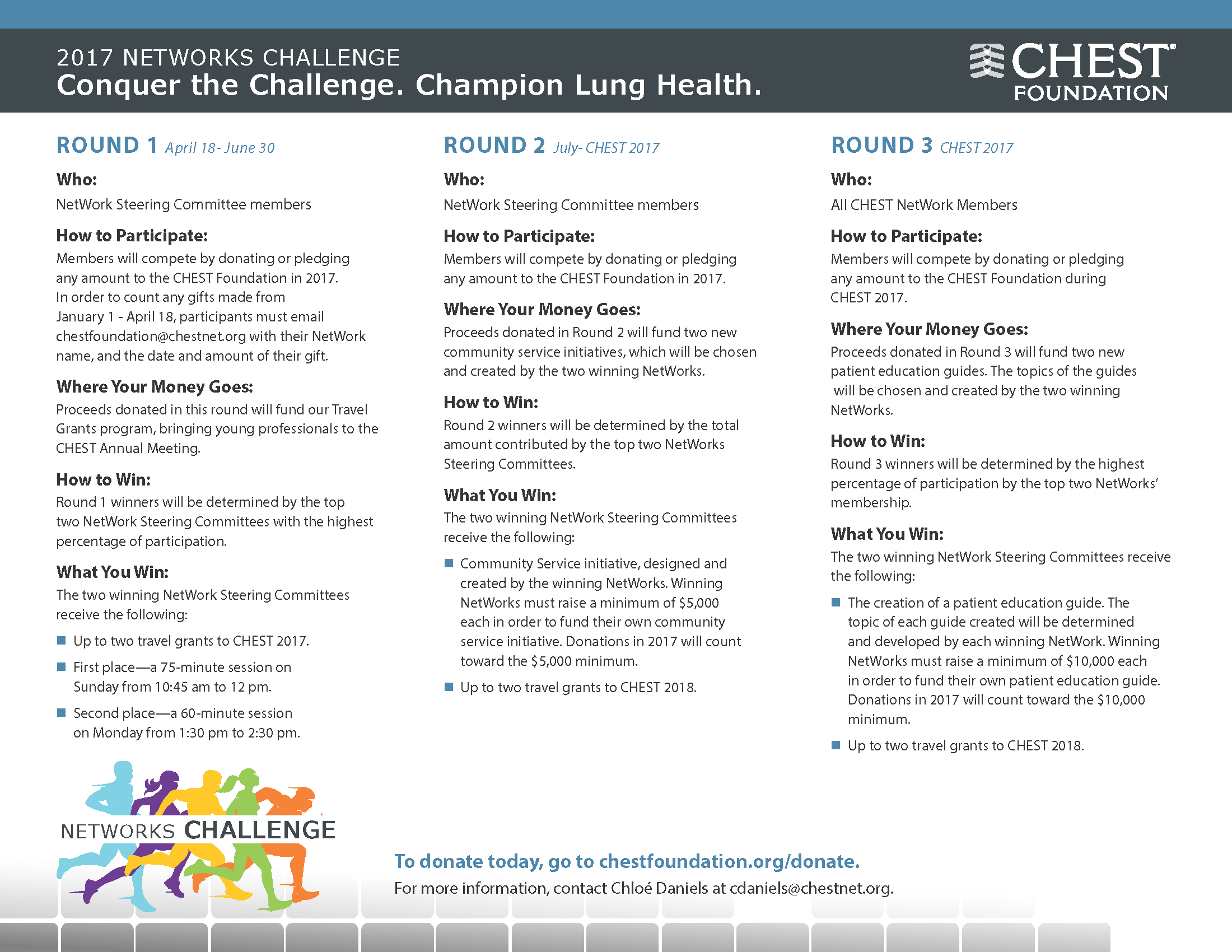

Participate in CHEST Foundation’s NetWorks Challenge

This month in CHEST: Editor’s picks

Original Research

Clinical Predictors of Hospital Mortality Differ Between Direct and Indirect ARDS. By Dr. L. Luo, et al.

Giants in Chest Medicine

Professor James C. Hogg. By Dr. Manuel G. Cosio.

Commentary

Pulmonary Hypertension Care Center Network: Improving Care and Outcomes in Pulmonary Hypertension. By Dr. S. Sahay, et al.

Evidence-Based Medicine

Use of Management Pathways or Algorithms in Children With Chronic Cough: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. By Dr. A. B. Chang, et al; on behalf of the CHEST Expert Cough Panel.

Symptomatic Treatment of Cough Among Adult Patients With Lung Cancer: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. By Dr. A. Molassiotis, et al; on behalf of the CHEST Expert Cough Panel.

Management of Children With Chronic Wet Cough and Protracted Bacterial Bronchitis: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. By Dr. A. B. Chang, et al; on behalf of the CHEST Expert Cough Panel.

Original Research

Clinical Predictors of Hospital Mortality Differ Between Direct and Indirect ARDS. By Dr. L. Luo, et al.

Giants in Chest Medicine

Professor James C. Hogg. By Dr. Manuel G. Cosio.

Commentary

Pulmonary Hypertension Care Center Network: Improving Care and Outcomes in Pulmonary Hypertension. By Dr. S. Sahay, et al.

Evidence-Based Medicine

Use of Management Pathways or Algorithms in Children With Chronic Cough: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. By Dr. A. B. Chang, et al; on behalf of the CHEST Expert Cough Panel.

Symptomatic Treatment of Cough Among Adult Patients With Lung Cancer: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. By Dr. A. Molassiotis, et al; on behalf of the CHEST Expert Cough Panel.

Management of Children With Chronic Wet Cough and Protracted Bacterial Bronchitis: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. By Dr. A. B. Chang, et al; on behalf of the CHEST Expert Cough Panel.

Original Research

Clinical Predictors of Hospital Mortality Differ Between Direct and Indirect ARDS. By Dr. L. Luo, et al.

Giants in Chest Medicine

Professor James C. Hogg. By Dr. Manuel G. Cosio.

Commentary

Pulmonary Hypertension Care Center Network: Improving Care and Outcomes in Pulmonary Hypertension. By Dr. S. Sahay, et al.

Evidence-Based Medicine

Use of Management Pathways or Algorithms in Children With Chronic Cough: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. By Dr. A. B. Chang, et al; on behalf of the CHEST Expert Cough Panel.

Symptomatic Treatment of Cough Among Adult Patients With Lung Cancer: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. By Dr. A. Molassiotis, et al; on behalf of the CHEST Expert Cough Panel.

Management of Children With Chronic Wet Cough and Protracted Bacterial Bronchitis: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. By Dr. A. B. Chang, et al; on behalf of the CHEST Expert Cough Panel.

NetWorks: Uranium mining, hyperoxia, palliative care education, OSA impact

Health effects of uranium mining

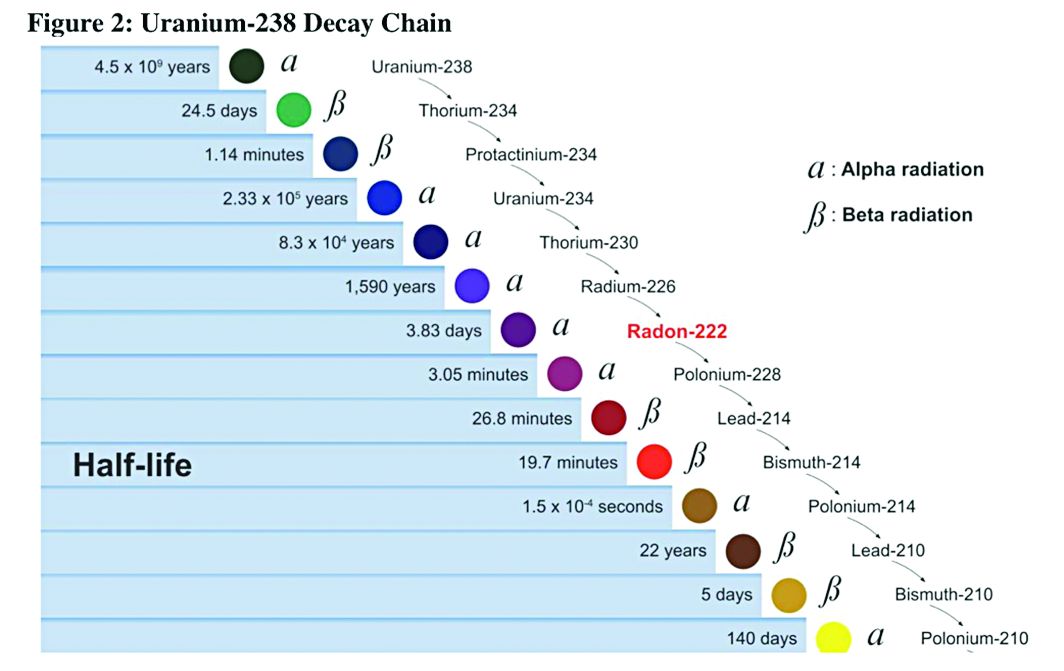

Decay series of U 238

Prior to 1900, uranium was used only for coloring glass. After discovery of radium by Madame Curie in 1898, uranium was widely mined to obtain radium (a decay product of uranium).

While uranium was not directly mined until 1900, uranium contaminates were in the ore in silver and cobalt mines in Czechoslovakia, which were heavily mined in the 18th and 19th centuries.

There were no reports (written in English) of lung cancer associated with radiation until 1942; but in 1944, these results were called into question in a monograph from the National Cancer Institute. The carcinogenicity of radon was confirmed in 1951; however, this remained an internal government document until 1980. By 1967, the increased prevalence of lung cancer in uranium miners was widely known. By 1970, new ventilation standards for uranium mines were established.

Lung cancer risk associated with uranium mining is the result of exposure to radon gas and specifically radon progeny of Polonium 218 and 210. These radon progeny remain suspended in air, attached to ambient particles (diesel exhaust, silica) and are then inhaled into the lung, where they tend to precipitate on the major airways. Polonium 218 and 210 are alpha emitters, which have a 20-fold increase in energy compared with gamma rays (the primary radiation source in radiation therapy). Given the mass of alpha particles (two protons and two neutrons), they interact with superficial tissues; thus, once deposited in the large airways, a large radiation dose is directed to the respiratory epithelium of these airways.

Occupational control of exposure to radon and radon progeny is accomplished primarily by ventilation. In high-grade deposits of uranium, such as the 20% ore grades in the Athabasca Basin of Saskatchewan, remote control mining is performed.

Smoking, in combination with occupational exposure to radon progeny, carries a greater than additive but less than multiplicative risk of lung cancer.

In addition to the lung cancer risk associated with radon progeny exposure, uranium miners share the occupational risks of other miners: exposure to silica and diesel exhaust. Miners are also at risk for traumatic injuries, including electrocution.

Health effects associated with uranium milling, enrichment, and tailings will be discussed in a subsequent CHEST Physician article.

Richard B. Evans, MD, MPH, FCCP

Steering Committee Chair

Hyperoxia in critically ill patients: What’s the verdict?

Oxygen saturation is considered to be the “fifth vital sign,” and current guidelines recommend target oxygen saturation (SpO2) between 94% and 98%, with lower targets for patients at risk for hypercapnic respiratory failure (O’Driscoll BR et al. Thorax. 2008;63(suppl):vi1). Oxygen toxicity is well-demonstrated in experimental animal studies. While its incidence and impact on outcomes is difficult to determine in the clinical setting, increases in-hospital mortality have been associated with hyperoxia in patients with cardiac arrest, acute myocardial infarction, and stroke (Kligannon et al. JAMA. 2010;303[21]:2165; Stub et al. Circulation. 2015;131[24]:2143; Rincon et al. Crit Care Med. 2014;42[2]:387).

Complementing the findings of Girardis and colleagues, a recent analysis of more than 14,000 critically ill patients, found that time spent at PaO2 > 200 mm Hg was associated with excess mortality and fewer ventilator-free days (Helmerhorst et al. Crit Care Med. 2017;45[2]:187).

While other trials demonstrated safety and feasibility of conservative oxygen therapy in critically ill patients (Panwar et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193[1]:43; Helmerhorst et al. Crit Care Med. 2016; 44[3]:554; Suzuki et al. Crit Care Med. 2014;42[6]:1414), they did not find significant differences between conservative and liberal oxygen therapy with regards to new organ dysfunction or mortality. However, the degree of hyperoxia was usually more modest than in either the Girardis trial or the Helmerhorst (2017) analysis.

Amanpreet Kaur, MD

Steering Committee Fellow-in-Training

David L. Bowton, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Chair

Education in palliative medicine

Prompted by concerns that the Affordable Care Act would be instituting “death panels” as part of cost-containment measures, “Dying in America” (a 2015 report of the Institute of Medicine [IOM]) identified compassionate, affordable, and effective care for patients at the end of their lives as a “national priority” in American health care. The IOM identified the education of all primary care providers in the delivery of basic palliative care, specifically commenting that all clinicians who manage patients with serious, life-threatening illnesses should be “competent in basic palliative care” (IOM, The National Academies Press 2015).

Check out our NetWork Storify page later this year for links to the ongoing discussion surrounding palliative care in medicine and for useful tools in the effort to provide palliative care to all our patients.

Laura Johnson, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Vice Chair

The impact of sleep apnea: Why should we care?

With recent large trials such as the SAVE and the SERVE-HF studies challenging the cardiovascular benefits of treating sleep-disordered breathing in specific patient subsets, many physicians may start to question, “Why all the fuss?” The Sleep NetWork is bringing the leaders in the field to CHEST 2017 to discuss their take on where we stand with the connection between sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular disease, so stay tuned!

Our relationships, general health, and work productivity can be affected by untreated OSA. The effect on daily life may not be initially obvious. Patients often present only at the insistence of their partner or physician, only to be surprised at how much better they feel once treated. Symptoms of OSA are associated with a higher rate of impaired work performance, sick leave, and divorce (Grunstein et al. Sleep. 1995;18[8]:635). A recent survey estimates an $86.9 billion loss of workplace productivity due to sleep apnea in 2015 (Frost & Sullivan. Hidden health crisis costing America billions. AASM; 2016. http://www.aasmnet.org/Resources/pdf/sleep-apnea-economic-crisis.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2017.). The same survey found that among those who are employed, treating OSA was associated with a decline in absences by 1.8 days per year and an increase in productivity 17.3% on average. Considering that the majority of OSA remains undiagnosed, this could have tremendous economic impact.

OSA is an important public health burden. The Sleep NetWork is committed to increasing awareness among individuals (patients and clinicians) and institutions (transportation agencies, government) of the impact of sleep-disordered breathing on society.

Aneesa Das, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Chair

Health effects of uranium mining

Decay series of U 238

Prior to 1900, uranium was used only for coloring glass. After discovery of radium by Madame Curie in 1898, uranium was widely mined to obtain radium (a decay product of uranium).

While uranium was not directly mined until 1900, uranium contaminates were in the ore in silver and cobalt mines in Czechoslovakia, which were heavily mined in the 18th and 19th centuries.

There were no reports (written in English) of lung cancer associated with radiation until 1942; but in 1944, these results were called into question in a monograph from the National Cancer Institute. The carcinogenicity of radon was confirmed in 1951; however, this remained an internal government document until 1980. By 1967, the increased prevalence of lung cancer in uranium miners was widely known. By 1970, new ventilation standards for uranium mines were established.

Lung cancer risk associated with uranium mining is the result of exposure to radon gas and specifically radon progeny of Polonium 218 and 210. These radon progeny remain suspended in air, attached to ambient particles (diesel exhaust, silica) and are then inhaled into the lung, where they tend to precipitate on the major airways. Polonium 218 and 210 are alpha emitters, which have a 20-fold increase in energy compared with gamma rays (the primary radiation source in radiation therapy). Given the mass of alpha particles (two protons and two neutrons), they interact with superficial tissues; thus, once deposited in the large airways, a large radiation dose is directed to the respiratory epithelium of these airways.

Occupational control of exposure to radon and radon progeny is accomplished primarily by ventilation. In high-grade deposits of uranium, such as the 20% ore grades in the Athabasca Basin of Saskatchewan, remote control mining is performed.

Smoking, in combination with occupational exposure to radon progeny, carries a greater than additive but less than multiplicative risk of lung cancer.

In addition to the lung cancer risk associated with radon progeny exposure, uranium miners share the occupational risks of other miners: exposure to silica and diesel exhaust. Miners are also at risk for traumatic injuries, including electrocution.

Health effects associated with uranium milling, enrichment, and tailings will be discussed in a subsequent CHEST Physician article.

Richard B. Evans, MD, MPH, FCCP

Steering Committee Chair

Hyperoxia in critically ill patients: What’s the verdict?

Oxygen saturation is considered to be the “fifth vital sign,” and current guidelines recommend target oxygen saturation (SpO2) between 94% and 98%, with lower targets for patients at risk for hypercapnic respiratory failure (O’Driscoll BR et al. Thorax. 2008;63(suppl):vi1). Oxygen toxicity is well-demonstrated in experimental animal studies. While its incidence and impact on outcomes is difficult to determine in the clinical setting, increases in-hospital mortality have been associated with hyperoxia in patients with cardiac arrest, acute myocardial infarction, and stroke (Kligannon et al. JAMA. 2010;303[21]:2165; Stub et al. Circulation. 2015;131[24]:2143; Rincon et al. Crit Care Med. 2014;42[2]:387).

Complementing the findings of Girardis and colleagues, a recent analysis of more than 14,000 critically ill patients, found that time spent at PaO2 > 200 mm Hg was associated with excess mortality and fewer ventilator-free days (Helmerhorst et al. Crit Care Med. 2017;45[2]:187).

While other trials demonstrated safety and feasibility of conservative oxygen therapy in critically ill patients (Panwar et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193[1]:43; Helmerhorst et al. Crit Care Med. 2016; 44[3]:554; Suzuki et al. Crit Care Med. 2014;42[6]:1414), they did not find significant differences between conservative and liberal oxygen therapy with regards to new organ dysfunction or mortality. However, the degree of hyperoxia was usually more modest than in either the Girardis trial or the Helmerhorst (2017) analysis.

Amanpreet Kaur, MD

Steering Committee Fellow-in-Training

David L. Bowton, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Chair

Education in palliative medicine

Prompted by concerns that the Affordable Care Act would be instituting “death panels” as part of cost-containment measures, “Dying in America” (a 2015 report of the Institute of Medicine [IOM]) identified compassionate, affordable, and effective care for patients at the end of their lives as a “national priority” in American health care. The IOM identified the education of all primary care providers in the delivery of basic palliative care, specifically commenting that all clinicians who manage patients with serious, life-threatening illnesses should be “competent in basic palliative care” (IOM, The National Academies Press 2015).

Check out our NetWork Storify page later this year for links to the ongoing discussion surrounding palliative care in medicine and for useful tools in the effort to provide palliative care to all our patients.

Laura Johnson, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Vice Chair

The impact of sleep apnea: Why should we care?

With recent large trials such as the SAVE and the SERVE-HF studies challenging the cardiovascular benefits of treating sleep-disordered breathing in specific patient subsets, many physicians may start to question, “Why all the fuss?” The Sleep NetWork is bringing the leaders in the field to CHEST 2017 to discuss their take on where we stand with the connection between sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular disease, so stay tuned!

Our relationships, general health, and work productivity can be affected by untreated OSA. The effect on daily life may not be initially obvious. Patients often present only at the insistence of their partner or physician, only to be surprised at how much better they feel once treated. Symptoms of OSA are associated with a higher rate of impaired work performance, sick leave, and divorce (Grunstein et al. Sleep. 1995;18[8]:635). A recent survey estimates an $86.9 billion loss of workplace productivity due to sleep apnea in 2015 (Frost & Sullivan. Hidden health crisis costing America billions. AASM; 2016. http://www.aasmnet.org/Resources/pdf/sleep-apnea-economic-crisis.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2017.). The same survey found that among those who are employed, treating OSA was associated with a decline in absences by 1.8 days per year and an increase in productivity 17.3% on average. Considering that the majority of OSA remains undiagnosed, this could have tremendous economic impact.

OSA is an important public health burden. The Sleep NetWork is committed to increasing awareness among individuals (patients and clinicians) and institutions (transportation agencies, government) of the impact of sleep-disordered breathing on society.

Aneesa Das, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Chair

Health effects of uranium mining

Decay series of U 238

Prior to 1900, uranium was used only for coloring glass. After discovery of radium by Madame Curie in 1898, uranium was widely mined to obtain radium (a decay product of uranium).

While uranium was not directly mined until 1900, uranium contaminates were in the ore in silver and cobalt mines in Czechoslovakia, which were heavily mined in the 18th and 19th centuries.

There were no reports (written in English) of lung cancer associated with radiation until 1942; but in 1944, these results were called into question in a monograph from the National Cancer Institute. The carcinogenicity of radon was confirmed in 1951; however, this remained an internal government document until 1980. By 1967, the increased prevalence of lung cancer in uranium miners was widely known. By 1970, new ventilation standards for uranium mines were established.

Lung cancer risk associated with uranium mining is the result of exposure to radon gas and specifically radon progeny of Polonium 218 and 210. These radon progeny remain suspended in air, attached to ambient particles (diesel exhaust, silica) and are then inhaled into the lung, where they tend to precipitate on the major airways. Polonium 218 and 210 are alpha emitters, which have a 20-fold increase in energy compared with gamma rays (the primary radiation source in radiation therapy). Given the mass of alpha particles (two protons and two neutrons), they interact with superficial tissues; thus, once deposited in the large airways, a large radiation dose is directed to the respiratory epithelium of these airways.

Occupational control of exposure to radon and radon progeny is accomplished primarily by ventilation. In high-grade deposits of uranium, such as the 20% ore grades in the Athabasca Basin of Saskatchewan, remote control mining is performed.

Smoking, in combination with occupational exposure to radon progeny, carries a greater than additive but less than multiplicative risk of lung cancer.

In addition to the lung cancer risk associated with radon progeny exposure, uranium miners share the occupational risks of other miners: exposure to silica and diesel exhaust. Miners are also at risk for traumatic injuries, including electrocution.

Health effects associated with uranium milling, enrichment, and tailings will be discussed in a subsequent CHEST Physician article.

Richard B. Evans, MD, MPH, FCCP

Steering Committee Chair

Hyperoxia in critically ill patients: What’s the verdict?

Oxygen saturation is considered to be the “fifth vital sign,” and current guidelines recommend target oxygen saturation (SpO2) between 94% and 98%, with lower targets for patients at risk for hypercapnic respiratory failure (O’Driscoll BR et al. Thorax. 2008;63(suppl):vi1). Oxygen toxicity is well-demonstrated in experimental animal studies. While its incidence and impact on outcomes is difficult to determine in the clinical setting, increases in-hospital mortality have been associated with hyperoxia in patients with cardiac arrest, acute myocardial infarction, and stroke (Kligannon et al. JAMA. 2010;303[21]:2165; Stub et al. Circulation. 2015;131[24]:2143; Rincon et al. Crit Care Med. 2014;42[2]:387).

Complementing the findings of Girardis and colleagues, a recent analysis of more than 14,000 critically ill patients, found that time spent at PaO2 > 200 mm Hg was associated with excess mortality and fewer ventilator-free days (Helmerhorst et al. Crit Care Med. 2017;45[2]:187).

While other trials demonstrated safety and feasibility of conservative oxygen therapy in critically ill patients (Panwar et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193[1]:43; Helmerhorst et al. Crit Care Med. 2016; 44[3]:554; Suzuki et al. Crit Care Med. 2014;42[6]:1414), they did not find significant differences between conservative and liberal oxygen therapy with regards to new organ dysfunction or mortality. However, the degree of hyperoxia was usually more modest than in either the Girardis trial or the Helmerhorst (2017) analysis.

Amanpreet Kaur, MD

Steering Committee Fellow-in-Training

David L. Bowton, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Chair

Education in palliative medicine

Prompted by concerns that the Affordable Care Act would be instituting “death panels” as part of cost-containment measures, “Dying in America” (a 2015 report of the Institute of Medicine [IOM]) identified compassionate, affordable, and effective care for patients at the end of their lives as a “national priority” in American health care. The IOM identified the education of all primary care providers in the delivery of basic palliative care, specifically commenting that all clinicians who manage patients with serious, life-threatening illnesses should be “competent in basic palliative care” (IOM, The National Academies Press 2015).

Check out our NetWork Storify page later this year for links to the ongoing discussion surrounding palliative care in medicine and for useful tools in the effort to provide palliative care to all our patients.

Laura Johnson, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Vice Chair

The impact of sleep apnea: Why should we care?

With recent large trials such as the SAVE and the SERVE-HF studies challenging the cardiovascular benefits of treating sleep-disordered breathing in specific patient subsets, many physicians may start to question, “Why all the fuss?” The Sleep NetWork is bringing the leaders in the field to CHEST 2017 to discuss their take on where we stand with the connection between sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular disease, so stay tuned!

Our relationships, general health, and work productivity can be affected by untreated OSA. The effect on daily life may not be initially obvious. Patients often present only at the insistence of their partner or physician, only to be surprised at how much better they feel once treated. Symptoms of OSA are associated with a higher rate of impaired work performance, sick leave, and divorce (Grunstein et al. Sleep. 1995;18[8]:635). A recent survey estimates an $86.9 billion loss of workplace productivity due to sleep apnea in 2015 (Frost & Sullivan. Hidden health crisis costing America billions. AASM; 2016. http://www.aasmnet.org/Resources/pdf/sleep-apnea-economic-crisis.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2017.). The same survey found that among those who are employed, treating OSA was associated with a decline in absences by 1.8 days per year and an increase in productivity 17.3% on average. Considering that the majority of OSA remains undiagnosed, this could have tremendous economic impact.

OSA is an important public health burden. The Sleep NetWork is committed to increasing awareness among individuals (patients and clinicians) and institutions (transportation agencies, government) of the impact of sleep-disordered breathing on society.

Aneesa Das, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Chair

In Memoriam

Sandra K. Willsie, DO, FCCP, died on March 26, 2017, after a courageous battle with brain cancer. As an osteopathic physician with board certification in internal medicine, pulmonary diseases, and critical care medicine, Sandra worked diligently for over 30 years to further scientific discovery and health-care education.

An NIH-funded career academic awardee, a Macy Institute scholar, and an invited faculty member on health-care leadership at Harvard University, Sandra was very involved in academic medicine. She served as professor of medicine, interim chair of medicine and docent at the University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Medicine; and as provost, dean, vice-dean, and department chair at Kansas City University of Osteopathic Medicine. Sandra earned a master’s degree in bioethics and health policy focusing on research ethics from Loyola University of Chicago Stritch School of Medicine. She made countless scholarly presentations and published regularly.

Sandra made eight pro bono trips to provide physicians in Honduras, Panama, Costa Rica, and the Dominican Republic the latest research updates on asthma and COPD research. She was honored to serve as president of Women Executives in Science and Healthcare and as board president of the American Heart Association’s Midwest Affiliate. She had been volunteering for over 30 years at the KC CARE Clinic in downtown Kansas City, Missouri, and was a committee member of the FDA advisory panel on respiratory and anesthesiology devices.

Sandra devoted many years of active participation to the American College of Chest Physicians and will be missed by so many colleagues and friends. She served on the Board of Regents and on the US and Canadian Council of Governors, was a member of numerous committees, including Education, Ethics, Marketing, Nominating, and Chair of the Scientific Presentations and Awards Committee. A staunch supporter of the CHEST Foundation, she was instrumental in its creation and served as a board and committee member. We extend our heartfelt condolences to her husband, Tom, and her family and many friends.

Sandra K. Willsie, DO, FCCP, died on March 26, 2017, after a courageous battle with brain cancer. As an osteopathic physician with board certification in internal medicine, pulmonary diseases, and critical care medicine, Sandra worked diligently for over 30 years to further scientific discovery and health-care education.

An NIH-funded career academic awardee, a Macy Institute scholar, and an invited faculty member on health-care leadership at Harvard University, Sandra was very involved in academic medicine. She served as professor of medicine, interim chair of medicine and docent at the University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Medicine; and as provost, dean, vice-dean, and department chair at Kansas City University of Osteopathic Medicine. Sandra earned a master’s degree in bioethics and health policy focusing on research ethics from Loyola University of Chicago Stritch School of Medicine. She made countless scholarly presentations and published regularly.

Sandra made eight pro bono trips to provide physicians in Honduras, Panama, Costa Rica, and the Dominican Republic the latest research updates on asthma and COPD research. She was honored to serve as president of Women Executives in Science and Healthcare and as board president of the American Heart Association’s Midwest Affiliate. She had been volunteering for over 30 years at the KC CARE Clinic in downtown Kansas City, Missouri, and was a committee member of the FDA advisory panel on respiratory and anesthesiology devices.

Sandra devoted many years of active participation to the American College of Chest Physicians and will be missed by so many colleagues and friends. She served on the Board of Regents and on the US and Canadian Council of Governors, was a member of numerous committees, including Education, Ethics, Marketing, Nominating, and Chair of the Scientific Presentations and Awards Committee. A staunch supporter of the CHEST Foundation, she was instrumental in its creation and served as a board and committee member. We extend our heartfelt condolences to her husband, Tom, and her family and many friends.

Sandra K. Willsie, DO, FCCP, died on March 26, 2017, after a courageous battle with brain cancer. As an osteopathic physician with board certification in internal medicine, pulmonary diseases, and critical care medicine, Sandra worked diligently for over 30 years to further scientific discovery and health-care education.

An NIH-funded career academic awardee, a Macy Institute scholar, and an invited faculty member on health-care leadership at Harvard University, Sandra was very involved in academic medicine. She served as professor of medicine, interim chair of medicine and docent at the University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Medicine; and as provost, dean, vice-dean, and department chair at Kansas City University of Osteopathic Medicine. Sandra earned a master’s degree in bioethics and health policy focusing on research ethics from Loyola University of Chicago Stritch School of Medicine. She made countless scholarly presentations and published regularly.

Sandra made eight pro bono trips to provide physicians in Honduras, Panama, Costa Rica, and the Dominican Republic the latest research updates on asthma and COPD research. She was honored to serve as president of Women Executives in Science and Healthcare and as board president of the American Heart Association’s Midwest Affiliate. She had been volunteering for over 30 years at the KC CARE Clinic in downtown Kansas City, Missouri, and was a committee member of the FDA advisory panel on respiratory and anesthesiology devices.

Sandra devoted many years of active participation to the American College of Chest Physicians and will be missed by so many colleagues and friends. She served on the Board of Regents and on the US and Canadian Council of Governors, was a member of numerous committees, including Education, Ethics, Marketing, Nominating, and Chair of the Scientific Presentations and Awards Committee. A staunch supporter of the CHEST Foundation, she was instrumental in its creation and served as a board and committee member. We extend our heartfelt condolences to her husband, Tom, and her family and many friends.

Critical Care Commentary: Sepsis resuscitation in a post-EGDT age

We must admit that we are all imperfect beings and, as such, we are all incorrect from time to time. In order to evolve to proverbial ‘higher planes of enlightenment,’ we must accept our cognitive errors – sometimes as individuals and other times as a collective entity. Within this framework of improvement through critical reflection, evidence-based medicine has been born. In this commentary, the authors address an area of smoldering contention and conflicting evidence—the role of EGDT in managing sepsis. If their call for an individualized approach to therapy is ultimately the ideal strategy, it may vindicate us all by simultaneously proving us all wrong.

Lee E. Morrow, MD, FCCP

The approach to sepsis resuscitation is emblematic of the challenges and opportunities of the evolution in this transition. There was no standardized approach to early sepsis resuscitation in the 20th century, and mortality from the disease approached 50% in many studies. This changed in 2001 with the publication of the landmark early-goal-directed therapy (EGDT) trial (Rivers et al. N Engl J Med. 2001;345[19]:1368). This single center trial demonstrated a dramatic 16% absolute decrease in mortality secondary to usage of an aggressive protocol for sepsis resuscitation within the first 6 hours after presentation to the ED. In addition to early cultures and antibiotic therapy in patients randomized to both EGDT and “usual care,” EGDT involved a number of mandatory elements, including placing both an arterial catheter and a central venous catheter capable of measuring continuous central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2). Patients received crystalloid or colloid until a predetermined central venous pressure was obtained, and if their mean arterial pressure was still below 65 mm Hg, therapy with pressors was initiated. If their ScvO2 was not 70% or greater, patients were transfused until their hematocrit was greater than 30%, and, if this still did not bring their ScvO2 up, patients were started on a regimen of dobutamine. Multiple trials of varying design subsequently demonstrated efficacy in this approach, which was rapidly adopted worldwide in many centers managing patients with sepsis.

However, many questions remained. All patients were managed the same in EGDT, with no capacity to individualize care, regardless of clinical situation (comorbidities, age, origin of sepsis). In addition, it was never clear which specific elements of the EGDT protocol were responsible for its success, as a bundled protocol could potentially simultaneously include beneficial, harmful, and neutral components. Further, many of the elements of EGDT have not been demonstrated to be beneficial in isolation. For example, multiple studies demonstrate that patients not receiving transfusions until their hemoglobin value reaches 7 g/dL is at least as effective as receiving transfusions to a hemoglobin value of 10 g/dL. Also, there is a wealth of data suggesting that central venous pressure is not an accurate surrogate for intravascular volume.

The difference between the original Rivers trial (demonstrating a huge benefit of EGDT) and the three subsequent trials leads (showing no benefit) was striking and leads to the obvious questions of (a) why were the results so disparate and (b) what should we do for our patients moving forward? Perhaps the most obvious difference in the trials is the baseline mortality in the “usual care” groups between the studies. In the original Rivers study, in-hospital mortality was 46.5% for the “usual care” group. For ARISE, ProCESS, and ProMISe, 60- to 90-day mortality ranged from 18.8% to 29.2% in the “usual care” group. This means either that the patients in the original EGDT trial were significantly sicker or that something fundamental has changed over time. A closer review of the papers reveals it is likely the latter as, in actuality, the “usual care” group in the three NEJM trials looked a lot like the EGDT group in the original trial. Most patients received significant volume resuscitation in these studies prior to enrollment, and the original ScvO2 was 71% in ProCESS (as opposed to 49% in the original Rivers trial). This suggested that increasing awareness of sepsis that occurred during the 15 years between the EGDT trial and the subsequent three trials – likely due to the Surviving Sepsis Campaign, as well as other efforts from both advocacy groups as well as medical organizations – led to better sepsis care on patient presentation. In essence, what was “usual care” in the time of the original EGDT study had become inappropriate care in the modern era, and much of what was protocolized in EGDT had been transformed into “usual care,” even if a specific protocol was not being used. In the setting in which “usual care” had dramatically improved, the original EGDT protocol was not helpful if implemented on all comers. One key reason is that many patients simply improved with volume and antibiotics (which had become “usual care”) and did not need additional interventions. Another reason is that some of the interventions in EGDT (blood transfusion, continuous ScvO2 monitoring) are likely not beneficial in the majority of cases.

These studies have led to significant changes in recommendations in sepsis management guidelines. The 2016 Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines – published after ARISE, ProCESS and ProMISe trials – still recommend antibiotics, cultures, adequate volume resuscitation (without specifying how to do so), targeting an initial mean arterial pressure of 65 mm Hg, and vasopressors if a patient remains hypotensive despite adequate fluids (Rhodes et al. Crit Care Med. 2017; 45). However, no recommendations are made regarding mandatory placement of a central venous catheter, measuring central venous pressure, transfusing to higher hemoglobin, etc.

In many ways, the last 15 years of fluid resuscitation in sepsis represents the triumph of evidence-based medicine over opinion-based medicine and the challenges of moving toward precision medicine. When “usual care” was highly variable without a consistent scientific rationale, EGDT markedly improved outcomes – a clear victory of evidence-based medicine that likely saved thousands of lives. However, when EGDT effectively became “usual care,” each individual element of EGDT bundled together failed to further improve outcome. The new evidence suggested that for all comers, EGDT is no better than the new normal, and, thus, newer guidelines do not recommend most of its components.

Moving forward, what is the best way to resuscitate newly identified patients with sepsis? A big fear in eliminating EGDT in its entirety is that practitioners will not have any guidance on how to manage resuscitation in sepsis and so will revert to less rigorous practice patterns. While we acknowledge that concern, we are optimistic that the future will continue to yield decreases in sepsis mortality. Optimally, volume status will be assessed on an individual basis. Rather than resuscitating every patient with a one-size-fits-all parameter that is fairly crude at best and inaccurate at worst (central venous pressure), bedside caregivers should use whatever tools are most appropriate to their individual patient and expertise. This could include bedside ultrasound, stroke volume variation, esophageal Doppler, passive leg raise, etc, depending on the clinical situation. The concept of appropriate volume resuscitation raised in EGDT continues to be 100% valid, but the implementation is now patient-specific and will vary upon available technology, provider skill, and bedside factors that might make one method superior to the other. Similarly, the failure of EGDT to improve survival in the ARISE, ProCESS, and ProMISe trials does not mean there is never a role for checking venous blood gases and measuring ScvO2. From our point of view, this would be a gross misinterpretation of the trials, as the finding that all elements of EGDT combined fail to benefit all patients with sepsis on arrival should assuredly not be interpreted as none of the elements of EGDT can ever be beneficial in any patients with sepsis. While we can – and should – learn from the data as they pertain to “all comers,” we equally can – and should – look at each individual patient and determine where they align with what is known (and unknown) in the literature and simultaneously attempt to both personalize and optimize their care utilizing our general knowledge of physiology and individual information that is unique to the patient.