User login

No benefit from added trabectedin for STS patients

When trabectedin was administered to soft tissue sarcoma (STS) patients receiving doxorubicin, neither progression-free nor overall survival significantly improved, investigators found.

In addition, patients who received both drugs were significantly more likely to experience adverse events.

“The combination of trabectedin plus doxorubicin did not show superiority over doxorubicin alone as first-line treatment of advanced STS patients, at least under this schedule. Moreover, the experimental arm was significantly more toxic than the control arm, especially regarding thrombocytopenia, vomiting, liver toxicity, and asthenia,” wrote Dr. Javier Martin-Broto of the Virgen del Rocio Hospital and Biomedicine Institute, Seville (Spain) and his associates (J Clin Oncol. 2016. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.3329).

Of 115 adult patients with advanced nonresectable or metastatic STS, 59 received doxorubicin only, 55 received both doxorubicin and trabectedin, and one patient was not treated. In the experimental group, doxorubicin was administered before trabectedin. Both the experimental and control groups underwent six cycles of their respective drug regime unless disease progression or unacceptable toxicity was observed.

A Cox proportional hazard regression model revealed that the progression-free survival was not significantly higher among patients receiving trabectedin and doxorubicin compared to patients only receiving doxorubicin (5.7 months vs. 5.5 months; hazard ratio, 1.16; 95% confidence interval, 0.79-1.71; P = .45). Overall survival was also not significantly different between the groups (13.3 months vs. 13.7 months; HR, 1.21; 95% CI, .77-1.92, P = .41).

However, compared with patients who only received doxorubicin, patients who received both trabectedin and doxorubicin experienced significantly more adverse events such as grade 3 or 4 thrombocytopenia (2% vs. 18%, P = .016), grade 3 or 4 liver toxicity (12% vs. 29%, P = .002), AST (0% vs. 8%, P = .007), ALT (0% vs. 19%, P less than .001), and grade 3 or 4 asthenia (4% vs. 25%, P = .002).

On Twitter @jess_craig94

When trabectedin was administered to soft tissue sarcoma (STS) patients receiving doxorubicin, neither progression-free nor overall survival significantly improved, investigators found.

In addition, patients who received both drugs were significantly more likely to experience adverse events.

“The combination of trabectedin plus doxorubicin did not show superiority over doxorubicin alone as first-line treatment of advanced STS patients, at least under this schedule. Moreover, the experimental arm was significantly more toxic than the control arm, especially regarding thrombocytopenia, vomiting, liver toxicity, and asthenia,” wrote Dr. Javier Martin-Broto of the Virgen del Rocio Hospital and Biomedicine Institute, Seville (Spain) and his associates (J Clin Oncol. 2016. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.3329).

Of 115 adult patients with advanced nonresectable or metastatic STS, 59 received doxorubicin only, 55 received both doxorubicin and trabectedin, and one patient was not treated. In the experimental group, doxorubicin was administered before trabectedin. Both the experimental and control groups underwent six cycles of their respective drug regime unless disease progression or unacceptable toxicity was observed.

A Cox proportional hazard regression model revealed that the progression-free survival was not significantly higher among patients receiving trabectedin and doxorubicin compared to patients only receiving doxorubicin (5.7 months vs. 5.5 months; hazard ratio, 1.16; 95% confidence interval, 0.79-1.71; P = .45). Overall survival was also not significantly different between the groups (13.3 months vs. 13.7 months; HR, 1.21; 95% CI, .77-1.92, P = .41).

However, compared with patients who only received doxorubicin, patients who received both trabectedin and doxorubicin experienced significantly more adverse events such as grade 3 or 4 thrombocytopenia (2% vs. 18%, P = .016), grade 3 or 4 liver toxicity (12% vs. 29%, P = .002), AST (0% vs. 8%, P = .007), ALT (0% vs. 19%, P less than .001), and grade 3 or 4 asthenia (4% vs. 25%, P = .002).

On Twitter @jess_craig94

When trabectedin was administered to soft tissue sarcoma (STS) patients receiving doxorubicin, neither progression-free nor overall survival significantly improved, investigators found.

In addition, patients who received both drugs were significantly more likely to experience adverse events.

“The combination of trabectedin plus doxorubicin did not show superiority over doxorubicin alone as first-line treatment of advanced STS patients, at least under this schedule. Moreover, the experimental arm was significantly more toxic than the control arm, especially regarding thrombocytopenia, vomiting, liver toxicity, and asthenia,” wrote Dr. Javier Martin-Broto of the Virgen del Rocio Hospital and Biomedicine Institute, Seville (Spain) and his associates (J Clin Oncol. 2016. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.3329).

Of 115 adult patients with advanced nonresectable or metastatic STS, 59 received doxorubicin only, 55 received both doxorubicin and trabectedin, and one patient was not treated. In the experimental group, doxorubicin was administered before trabectedin. Both the experimental and control groups underwent six cycles of their respective drug regime unless disease progression or unacceptable toxicity was observed.

A Cox proportional hazard regression model revealed that the progression-free survival was not significantly higher among patients receiving trabectedin and doxorubicin compared to patients only receiving doxorubicin (5.7 months vs. 5.5 months; hazard ratio, 1.16; 95% confidence interval, 0.79-1.71; P = .45). Overall survival was also not significantly different between the groups (13.3 months vs. 13.7 months; HR, 1.21; 95% CI, .77-1.92, P = .41).

However, compared with patients who only received doxorubicin, patients who received both trabectedin and doxorubicin experienced significantly more adverse events such as grade 3 or 4 thrombocytopenia (2% vs. 18%, P = .016), grade 3 or 4 liver toxicity (12% vs. 29%, P = .002), AST (0% vs. 8%, P = .007), ALT (0% vs. 19%, P less than .001), and grade 3 or 4 asthenia (4% vs. 25%, P = .002).

On Twitter @jess_craig94

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: When trabectedin was administered to soft tissue sarcoma (STS) patients receiving doxorubicin, neither progression-free nor overall survival significantly improved. However, patients who received both drugs were significantly more likely to experience adverse events.

Major finding: Progression-free survival was not significantly higher among patients receiving trabectedin and doxorubicin, compared with patients only receiving doxorubicin (5.7 months vs. 5.5 months; HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.79-1.71; P = .45). Compared with patients who only received doxorubicin, patients who received both drugs experienced significantly more adverse events such as thrombocytopenia, liver toxicity, AST, ALT, and asthenia (all P values less than .05).

Data source: Randomized phase II trial of 115 adult patients with advanced nonresectable soft tissue sarcoma.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Spanish Group for Research on Sarcoma. Ten investigators reported serving in advisory roles or receiving financial compensation or honoraria from several companies. The other 14 investigators reported having no disclosures.

FDA grants priority review of olaratumab for advanced sarcoma

The Food and Drug Administration has granted priority review of olaratumab, in combination with doxorubicin, for the treatment of patients with advanced soft tissue sarcoma who unsuccessfully underwent prior radiotherapy or surgery for their cancer.

Olaratumab is a human IgG1 monoclonal antibody that directly targets tumor cells by disrupting the platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha, a receptor that is believed to play a role in tumor growth and progression.

“We are hopeful that, if approved, olaratumab will provide a meaningful addition to the limited treatment options for this rare and difficult-to-treat disease,” Dr. Richard Gaynor, senior vice president of product development and medical affairs for Lilly Oncology, the maker of the drug, said in a written statement issued by company.

The biologics license application submission for olaratumab was based on a phase II clinical trial of 129 patients with metastatic or unresectable soft tissue sarcoma. Sixty-four patients were assigned to the treatment group and received both doxorubicin and olaratumab. Patients in this group continued to receive olaratumab through observed disease progression. Sixty-five patients were assigned to the control group and received only doxorubicin until disease progression was first observed. Patients who received olaratumab in addition to doxorubicin experienced a longer median progression-free survival, compared with patients who only received doxorubicin (6.6 months vs. 4.1 months; stratified hazard ratio, 0.672; 95% confidence interval, 0.442 to 1.021; P = .0615). The results of the phase II clinical trial were reported at the 2015 American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting and the 2015 Connective Tissue Oncology Society annual meeting.

The FDA previously granted olaratumab breakthrough therapy, fast track, and orphan drug designation.

On Twitter @jess_craig94

The Food and Drug Administration has granted priority review of olaratumab, in combination with doxorubicin, for the treatment of patients with advanced soft tissue sarcoma who unsuccessfully underwent prior radiotherapy or surgery for their cancer.

Olaratumab is a human IgG1 monoclonal antibody that directly targets tumor cells by disrupting the platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha, a receptor that is believed to play a role in tumor growth and progression.

“We are hopeful that, if approved, olaratumab will provide a meaningful addition to the limited treatment options for this rare and difficult-to-treat disease,” Dr. Richard Gaynor, senior vice president of product development and medical affairs for Lilly Oncology, the maker of the drug, said in a written statement issued by company.

The biologics license application submission for olaratumab was based on a phase II clinical trial of 129 patients with metastatic or unresectable soft tissue sarcoma. Sixty-four patients were assigned to the treatment group and received both doxorubicin and olaratumab. Patients in this group continued to receive olaratumab through observed disease progression. Sixty-five patients were assigned to the control group and received only doxorubicin until disease progression was first observed. Patients who received olaratumab in addition to doxorubicin experienced a longer median progression-free survival, compared with patients who only received doxorubicin (6.6 months vs. 4.1 months; stratified hazard ratio, 0.672; 95% confidence interval, 0.442 to 1.021; P = .0615). The results of the phase II clinical trial were reported at the 2015 American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting and the 2015 Connective Tissue Oncology Society annual meeting.

The FDA previously granted olaratumab breakthrough therapy, fast track, and orphan drug designation.

On Twitter @jess_craig94

The Food and Drug Administration has granted priority review of olaratumab, in combination with doxorubicin, for the treatment of patients with advanced soft tissue sarcoma who unsuccessfully underwent prior radiotherapy or surgery for their cancer.

Olaratumab is a human IgG1 monoclonal antibody that directly targets tumor cells by disrupting the platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha, a receptor that is believed to play a role in tumor growth and progression.

“We are hopeful that, if approved, olaratumab will provide a meaningful addition to the limited treatment options for this rare and difficult-to-treat disease,” Dr. Richard Gaynor, senior vice president of product development and medical affairs for Lilly Oncology, the maker of the drug, said in a written statement issued by company.

The biologics license application submission for olaratumab was based on a phase II clinical trial of 129 patients with metastatic or unresectable soft tissue sarcoma. Sixty-four patients were assigned to the treatment group and received both doxorubicin and olaratumab. Patients in this group continued to receive olaratumab through observed disease progression. Sixty-five patients were assigned to the control group and received only doxorubicin until disease progression was first observed. Patients who received olaratumab in addition to doxorubicin experienced a longer median progression-free survival, compared with patients who only received doxorubicin (6.6 months vs. 4.1 months; stratified hazard ratio, 0.672; 95% confidence interval, 0.442 to 1.021; P = .0615). The results of the phase II clinical trial were reported at the 2015 American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting and the 2015 Connective Tissue Oncology Society annual meeting.

The FDA previously granted olaratumab breakthrough therapy, fast track, and orphan drug designation.

On Twitter @jess_craig94

Targeting gene rearrangements shows promise in early study

Entrectinib, an investigational drug that targets several abnormal fusion proteins, showed antitumor activity and was safe in patients with several different types of advanced solid tumors. The patients had never before been exposed to drugs targeting these same genetic alterations.

“Responses can be very rapid and durable … which include colorectal, primary brain tumor, astrocytoma, fibrosarcoma, lung, and mammary analog secretory carcinoma,” Dr. Alexander Drilon of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York said in a news conference at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research. “Dramatic intracranial activity … has been demonstrated both in primary brain tumor and also in metastatic.”

NTRK1/2/3, ROS1, and ALK gene–rearranged cancers produce fusion proteins that are ligand independent for their activity and thus constitutively active, driving tumor growth. Entrectinib is a pan-TRK, ROS1, ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitor that targets the abnormal fusion protein products of the genes, is highly potent at low concentrations, and has been designed to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB). The targeted proteins are present across multiple cancers and are especially prevalent (greater than 80%) among some rare adult and pediatric cancers.

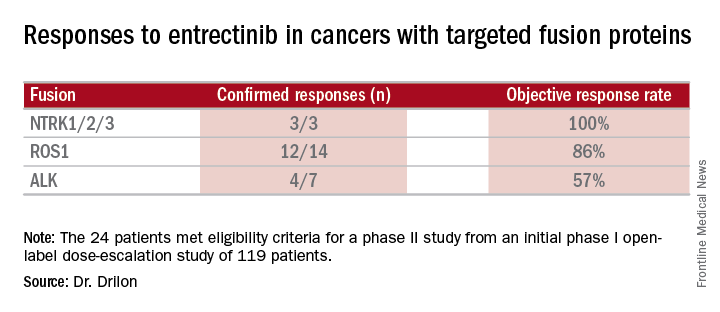

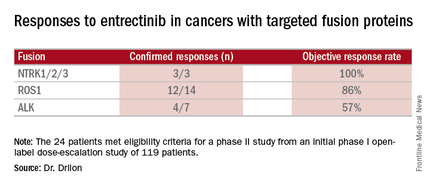

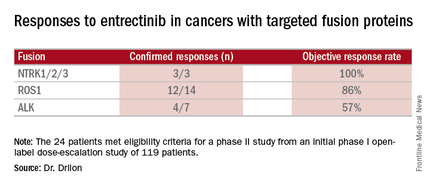

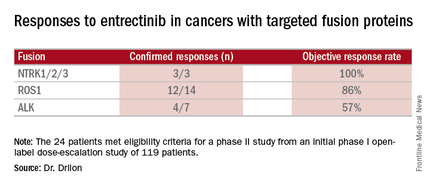

Combined data on 119 patients in two phase I trials established 600 mg orally once daily as the recommended dose to go into phase II trials. Among the 24 patients meeting eligibility criteria for a phase II trial (presence of the targeted gene fusions in their tumors, no prior treatment against these targets, and treatment at or above 600 mg daily), the confirmed response rate was 79% (19/24). Most were partial responses in terms of tumor shrinkage, but two patients had complete responses. Response rates appeared to vary according to the specific fusion protein defect.

All three cases of CNS disease with NTRK-rearranged cancers had intracranial responses, demonstrating that the drug crosses the BBB and is active. In one case, a 46-year-old man with brain metastases heavily pretreated for non–small cell lung cancer with an NTRK1 rearrangement experienced a dramatic response.

“The patient at that point was actually on hospice and was doing extremely poorly on supplemental oxygen,” Dr. Drilon said. “Within a few weeks, the patient had a dramatic clinical response to therapy … At day 26 there was almost a 50% reduction in tumor burden.” At day 317 scans showed he had a complete intracranial response to entrectinib, but he still has visceral disease on therapy past 1 year.

Responses often occurred within the first month of therapy, and many persisted for several months without disease progression, with one patient being followed for more than 2 years with clinical benefit. Nineteen of 24 patients have been on the therapy for more than 6 months, and the therapy appears to be safe and well tolerated.

Commenting on this study and others targeting specific genetic alterations leading to cancer, Dr. Louis Weiner, director of the Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center in Washington, said, “You’re seeing a series of clinical trials described that aren’t necessarily targeting people with a particular cancer but rather people who have cancers characterized by particular molecular abnormalities.” Not all cancers will have identified molecular abnormalities driving them. “However, I think where you have these drivers, the proper thing to do is not to worry about whether [a drug] works in a given disease but rather whether it works for people with that particular abnormality,” he said.

For the future, the investigators plan a phase II trial called STARTRK-2. It is a multicenter, open-label, global basket study to include any solid tumors with the targeted rearrangements.

Dr. Drilon disclosed ties with Ignyta, which funded the study, and has received research funding from Foundation Medicine. Dr. Weiner disclosed ties with several pharmaceutical companies.

Entrectinib, an investigational drug that targets several abnormal fusion proteins, showed antitumor activity and was safe in patients with several different types of advanced solid tumors. The patients had never before been exposed to drugs targeting these same genetic alterations.

“Responses can be very rapid and durable … which include colorectal, primary brain tumor, astrocytoma, fibrosarcoma, lung, and mammary analog secretory carcinoma,” Dr. Alexander Drilon of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York said in a news conference at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research. “Dramatic intracranial activity … has been demonstrated both in primary brain tumor and also in metastatic.”

NTRK1/2/3, ROS1, and ALK gene–rearranged cancers produce fusion proteins that are ligand independent for their activity and thus constitutively active, driving tumor growth. Entrectinib is a pan-TRK, ROS1, ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitor that targets the abnormal fusion protein products of the genes, is highly potent at low concentrations, and has been designed to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB). The targeted proteins are present across multiple cancers and are especially prevalent (greater than 80%) among some rare adult and pediatric cancers.

Combined data on 119 patients in two phase I trials established 600 mg orally once daily as the recommended dose to go into phase II trials. Among the 24 patients meeting eligibility criteria for a phase II trial (presence of the targeted gene fusions in their tumors, no prior treatment against these targets, and treatment at or above 600 mg daily), the confirmed response rate was 79% (19/24). Most were partial responses in terms of tumor shrinkage, but two patients had complete responses. Response rates appeared to vary according to the specific fusion protein defect.

All three cases of CNS disease with NTRK-rearranged cancers had intracranial responses, demonstrating that the drug crosses the BBB and is active. In one case, a 46-year-old man with brain metastases heavily pretreated for non–small cell lung cancer with an NTRK1 rearrangement experienced a dramatic response.

“The patient at that point was actually on hospice and was doing extremely poorly on supplemental oxygen,” Dr. Drilon said. “Within a few weeks, the patient had a dramatic clinical response to therapy … At day 26 there was almost a 50% reduction in tumor burden.” At day 317 scans showed he had a complete intracranial response to entrectinib, but he still has visceral disease on therapy past 1 year.

Responses often occurred within the first month of therapy, and many persisted for several months without disease progression, with one patient being followed for more than 2 years with clinical benefit. Nineteen of 24 patients have been on the therapy for more than 6 months, and the therapy appears to be safe and well tolerated.

Commenting on this study and others targeting specific genetic alterations leading to cancer, Dr. Louis Weiner, director of the Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center in Washington, said, “You’re seeing a series of clinical trials described that aren’t necessarily targeting people with a particular cancer but rather people who have cancers characterized by particular molecular abnormalities.” Not all cancers will have identified molecular abnormalities driving them. “However, I think where you have these drivers, the proper thing to do is not to worry about whether [a drug] works in a given disease but rather whether it works for people with that particular abnormality,” he said.

For the future, the investigators plan a phase II trial called STARTRK-2. It is a multicenter, open-label, global basket study to include any solid tumors with the targeted rearrangements.

Dr. Drilon disclosed ties with Ignyta, which funded the study, and has received research funding from Foundation Medicine. Dr. Weiner disclosed ties with several pharmaceutical companies.

Entrectinib, an investigational drug that targets several abnormal fusion proteins, showed antitumor activity and was safe in patients with several different types of advanced solid tumors. The patients had never before been exposed to drugs targeting these same genetic alterations.

“Responses can be very rapid and durable … which include colorectal, primary brain tumor, astrocytoma, fibrosarcoma, lung, and mammary analog secretory carcinoma,” Dr. Alexander Drilon of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York said in a news conference at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research. “Dramatic intracranial activity … has been demonstrated both in primary brain tumor and also in metastatic.”

NTRK1/2/3, ROS1, and ALK gene–rearranged cancers produce fusion proteins that are ligand independent for their activity and thus constitutively active, driving tumor growth. Entrectinib is a pan-TRK, ROS1, ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitor that targets the abnormal fusion protein products of the genes, is highly potent at low concentrations, and has been designed to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB). The targeted proteins are present across multiple cancers and are especially prevalent (greater than 80%) among some rare adult and pediatric cancers.

Combined data on 119 patients in two phase I trials established 600 mg orally once daily as the recommended dose to go into phase II trials. Among the 24 patients meeting eligibility criteria for a phase II trial (presence of the targeted gene fusions in their tumors, no prior treatment against these targets, and treatment at or above 600 mg daily), the confirmed response rate was 79% (19/24). Most were partial responses in terms of tumor shrinkage, but two patients had complete responses. Response rates appeared to vary according to the specific fusion protein defect.

All three cases of CNS disease with NTRK-rearranged cancers had intracranial responses, demonstrating that the drug crosses the BBB and is active. In one case, a 46-year-old man with brain metastases heavily pretreated for non–small cell lung cancer with an NTRK1 rearrangement experienced a dramatic response.

“The patient at that point was actually on hospice and was doing extremely poorly on supplemental oxygen,” Dr. Drilon said. “Within a few weeks, the patient had a dramatic clinical response to therapy … At day 26 there was almost a 50% reduction in tumor burden.” At day 317 scans showed he had a complete intracranial response to entrectinib, but he still has visceral disease on therapy past 1 year.

Responses often occurred within the first month of therapy, and many persisted for several months without disease progression, with one patient being followed for more than 2 years with clinical benefit. Nineteen of 24 patients have been on the therapy for more than 6 months, and the therapy appears to be safe and well tolerated.

Commenting on this study and others targeting specific genetic alterations leading to cancer, Dr. Louis Weiner, director of the Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center in Washington, said, “You’re seeing a series of clinical trials described that aren’t necessarily targeting people with a particular cancer but rather people who have cancers characterized by particular molecular abnormalities.” Not all cancers will have identified molecular abnormalities driving them. “However, I think where you have these drivers, the proper thing to do is not to worry about whether [a drug] works in a given disease but rather whether it works for people with that particular abnormality,” he said.

For the future, the investigators plan a phase II trial called STARTRK-2. It is a multicenter, open-label, global basket study to include any solid tumors with the targeted rearrangements.

Dr. Drilon disclosed ties with Ignyta, which funded the study, and has received research funding from Foundation Medicine. Dr. Weiner disclosed ties with several pharmaceutical companies.

FROM THE AACR ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Entrectinib showed antitumor activity including intracranial responses.

Major finding: Patients with the targeted abnormalities had a 79% response rate.

Data source: Twenty-four patients meeting eligibility criteria for a phase II study from an initial phase I open-label dose-escalation study of 119 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Drilon disclosed ties with Ignyta, which funded the study, and has received research funding from Foundation Medicine. Dr. Weiner disclosed ties with several pharmaceutical companies.

Older patients with soft tissue sarcoma may receive greater benefit from RT

Older patients appeared to receive greater benefit from adjuvant radiotherapy (RT) for soft tissue sarcoma (STS) than younger patients, according an analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database.

Several STS subtypes were associated with significant RT benefits to overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) in patients older than 65 years, but survival differences were not significant in younger patients. These seven subtypes included leiomyosarcoma (hazard ratio, 0.84; P = .04), sarcoma not otherwise specified (HR, 0.66; P less than or equal to .001), liposarcoma not otherwise specified (HR, 0.72; P = .05), myxoid liposarcoma (HR, 0.50; P = .02), rhabdomyosarcoma (HR, 0.23; P less than or equal to .001), epithelioid (HR, 0.01; P less than .01) and myxoid chondrosarcoma (HR, 0.02; P = .04). One STS subtype, synovial sarcoma, was associated with significant RT benefit only in younger patients (HR, 0.73; P = .04). Malignant fibrous histiocytoma was the only subtype to show significant benefit in the overall cohort as well as both age groups.

“We observed a statistically significant improvement in OS and DSS in all patients receiving RT compared to surgery alone across the majority of histological subgroups. More importantly, there was no significant improvement in younger patients compared to a significant improvement in older patients, suggesting that survival benefits in response to RT are significantly affected by age-related differences,” wrote Dr. Noah K. Yuen of the Department of Surgery, University of California, Davis, and his colleagues (Anticancer Res. 2016 Apr;36(4):1745-50). The findings suggest that older patients may benefit more than previously appreciated, and while implementation of RT among the elderly may present challenges, according to the investigators, “our data suggest that this approach deserves greater attention.”

Previous population-based retrospective studies have demonstrated a similar benefit with surgery and adjuvant RT; however, randomized clinical trials have shown significant improvement in local control but have failed to show significant improvement in OS. The authors acknowledged the potential impact of unmeasured confounding factors on the retrospective study. Selection bias may be present if healthier older patients preferentially received RT; a subpopulation of healthier individuals would be expected to have better survival.

The SEER database analysis included 15,380 patients with non-metastatic STS who underwent surgery during 1990 to 2011. The mean age of the cohort was 56.6 years and one-third were age 65 years or more. As the most common histologic subtype, leiomyosarcoma accounted for 30.1% of all tumors. Most of the patients treated with RT (68.3%) had high-grade tumors.

Older patients appeared to receive greater benefit from adjuvant radiotherapy (RT) for soft tissue sarcoma (STS) than younger patients, according an analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database.

Several STS subtypes were associated with significant RT benefits to overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) in patients older than 65 years, but survival differences were not significant in younger patients. These seven subtypes included leiomyosarcoma (hazard ratio, 0.84; P = .04), sarcoma not otherwise specified (HR, 0.66; P less than or equal to .001), liposarcoma not otherwise specified (HR, 0.72; P = .05), myxoid liposarcoma (HR, 0.50; P = .02), rhabdomyosarcoma (HR, 0.23; P less than or equal to .001), epithelioid (HR, 0.01; P less than .01) and myxoid chondrosarcoma (HR, 0.02; P = .04). One STS subtype, synovial sarcoma, was associated with significant RT benefit only in younger patients (HR, 0.73; P = .04). Malignant fibrous histiocytoma was the only subtype to show significant benefit in the overall cohort as well as both age groups.

“We observed a statistically significant improvement in OS and DSS in all patients receiving RT compared to surgery alone across the majority of histological subgroups. More importantly, there was no significant improvement in younger patients compared to a significant improvement in older patients, suggesting that survival benefits in response to RT are significantly affected by age-related differences,” wrote Dr. Noah K. Yuen of the Department of Surgery, University of California, Davis, and his colleagues (Anticancer Res. 2016 Apr;36(4):1745-50). The findings suggest that older patients may benefit more than previously appreciated, and while implementation of RT among the elderly may present challenges, according to the investigators, “our data suggest that this approach deserves greater attention.”

Previous population-based retrospective studies have demonstrated a similar benefit with surgery and adjuvant RT; however, randomized clinical trials have shown significant improvement in local control but have failed to show significant improvement in OS. The authors acknowledged the potential impact of unmeasured confounding factors on the retrospective study. Selection bias may be present if healthier older patients preferentially received RT; a subpopulation of healthier individuals would be expected to have better survival.

The SEER database analysis included 15,380 patients with non-metastatic STS who underwent surgery during 1990 to 2011. The mean age of the cohort was 56.6 years and one-third were age 65 years or more. As the most common histologic subtype, leiomyosarcoma accounted for 30.1% of all tumors. Most of the patients treated with RT (68.3%) had high-grade tumors.

Older patients appeared to receive greater benefit from adjuvant radiotherapy (RT) for soft tissue sarcoma (STS) than younger patients, according an analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database.

Several STS subtypes were associated with significant RT benefits to overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) in patients older than 65 years, but survival differences were not significant in younger patients. These seven subtypes included leiomyosarcoma (hazard ratio, 0.84; P = .04), sarcoma not otherwise specified (HR, 0.66; P less than or equal to .001), liposarcoma not otherwise specified (HR, 0.72; P = .05), myxoid liposarcoma (HR, 0.50; P = .02), rhabdomyosarcoma (HR, 0.23; P less than or equal to .001), epithelioid (HR, 0.01; P less than .01) and myxoid chondrosarcoma (HR, 0.02; P = .04). One STS subtype, synovial sarcoma, was associated with significant RT benefit only in younger patients (HR, 0.73; P = .04). Malignant fibrous histiocytoma was the only subtype to show significant benefit in the overall cohort as well as both age groups.

“We observed a statistically significant improvement in OS and DSS in all patients receiving RT compared to surgery alone across the majority of histological subgroups. More importantly, there was no significant improvement in younger patients compared to a significant improvement in older patients, suggesting that survival benefits in response to RT are significantly affected by age-related differences,” wrote Dr. Noah K. Yuen of the Department of Surgery, University of California, Davis, and his colleagues (Anticancer Res. 2016 Apr;36(4):1745-50). The findings suggest that older patients may benefit more than previously appreciated, and while implementation of RT among the elderly may present challenges, according to the investigators, “our data suggest that this approach deserves greater attention.”

Previous population-based retrospective studies have demonstrated a similar benefit with surgery and adjuvant RT; however, randomized clinical trials have shown significant improvement in local control but have failed to show significant improvement in OS. The authors acknowledged the potential impact of unmeasured confounding factors on the retrospective study. Selection bias may be present if healthier older patients preferentially received RT; a subpopulation of healthier individuals would be expected to have better survival.

The SEER database analysis included 15,380 patients with non-metastatic STS who underwent surgery during 1990 to 2011. The mean age of the cohort was 56.6 years and one-third were age 65 years or more. As the most common histologic subtype, leiomyosarcoma accounted for 30.1% of all tumors. Most of the patients treated with RT (68.3%) had high-grade tumors.

FROM ANTICANCER RESEARCH

Key clinical point: For many subtypes of soft tissue sarcoma (STS), overall survival (OS) was significantly greater in older patients who received adjuvant RT, compared with those who received surgery alone.

Major finding: Among patients age 65 years and older who received RT, most STS subtypes were associated with significantly improved OS; among younger patients, only three subtypes were associated with significantly improved OS.

Data sources: The retrospective analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database included 15,380 patients with non-metastatic STS who underwent surgery during 1990 to 2011.

Disclosures: Dr. Yuen and his coauthors reported having no disclosures.

Feds advance cancer moonshot with expert panel, outline of goals

Federal officials took the next step in their moonshot to end cancer by announcing on April 4 a blue ribbon panel to guide the effort.

A total of 28 leading researchers, clinicians, and patient advocates have been named to the panel charged with informing the scientific direction and goals of the National Cancer Moonshot Initiative, led by Vice President Joe Biden.

“This Blue Ribbon Panel will ensure that, as [the National Institutes of Health] allocates new resources through the Moonshot, decisions will be grounded in the best science,” Vice President Biden said in a statement. “I look forward to working with this panel and many others involved with the Moonshot to make unprecedented improvements in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer.”

The key goals of the initiative were set out simultaneously in a perspective from Dr. Francis S. Collins, NIH director, and Dr. Douglas R. Lowy, director of the National Cancer Institute. The editorial was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Fueled by an additional $680 million in the proposed fiscal year 2017 budget for the NIH, plus additional resources for the Food and Drug Administration, the initiative will aim to accelerate progress toward the next generation of interventions that we hope will substantially reduce cancer incidence and dramatically improve patient outcomes,” Dr. Collins and Dr. Lowy wrote. “The NIH’s most compelling opportunities for progress will be set forth by late summer 2016 in a research plan informed by the deliberations of a blue-ribbon panel of experts, which will provide scientific input to the National Cancer Advisory Board. Some possible opportunities include vaccine development, early-detection technology, single-cell genomic analysis, immunotherapy, a focus on pediatric cancer, and enhanced data sharing.”

To read the full editorial, click here.

On Twitter @denisefulton

Federal officials took the next step in their moonshot to end cancer by announcing on April 4 a blue ribbon panel to guide the effort.

A total of 28 leading researchers, clinicians, and patient advocates have been named to the panel charged with informing the scientific direction and goals of the National Cancer Moonshot Initiative, led by Vice President Joe Biden.

“This Blue Ribbon Panel will ensure that, as [the National Institutes of Health] allocates new resources through the Moonshot, decisions will be grounded in the best science,” Vice President Biden said in a statement. “I look forward to working with this panel and many others involved with the Moonshot to make unprecedented improvements in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer.”

The key goals of the initiative were set out simultaneously in a perspective from Dr. Francis S. Collins, NIH director, and Dr. Douglas R. Lowy, director of the National Cancer Institute. The editorial was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Fueled by an additional $680 million in the proposed fiscal year 2017 budget for the NIH, plus additional resources for the Food and Drug Administration, the initiative will aim to accelerate progress toward the next generation of interventions that we hope will substantially reduce cancer incidence and dramatically improve patient outcomes,” Dr. Collins and Dr. Lowy wrote. “The NIH’s most compelling opportunities for progress will be set forth by late summer 2016 in a research plan informed by the deliberations of a blue-ribbon panel of experts, which will provide scientific input to the National Cancer Advisory Board. Some possible opportunities include vaccine development, early-detection technology, single-cell genomic analysis, immunotherapy, a focus on pediatric cancer, and enhanced data sharing.”

To read the full editorial, click here.

On Twitter @denisefulton

Federal officials took the next step in their moonshot to end cancer by announcing on April 4 a blue ribbon panel to guide the effort.

A total of 28 leading researchers, clinicians, and patient advocates have been named to the panel charged with informing the scientific direction and goals of the National Cancer Moonshot Initiative, led by Vice President Joe Biden.

“This Blue Ribbon Panel will ensure that, as [the National Institutes of Health] allocates new resources through the Moonshot, decisions will be grounded in the best science,” Vice President Biden said in a statement. “I look forward to working with this panel and many others involved with the Moonshot to make unprecedented improvements in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer.”

The key goals of the initiative were set out simultaneously in a perspective from Dr. Francis S. Collins, NIH director, and Dr. Douglas R. Lowy, director of the National Cancer Institute. The editorial was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Fueled by an additional $680 million in the proposed fiscal year 2017 budget for the NIH, plus additional resources for the Food and Drug Administration, the initiative will aim to accelerate progress toward the next generation of interventions that we hope will substantially reduce cancer incidence and dramatically improve patient outcomes,” Dr. Collins and Dr. Lowy wrote. “The NIH’s most compelling opportunities for progress will be set forth by late summer 2016 in a research plan informed by the deliberations of a blue-ribbon panel of experts, which will provide scientific input to the National Cancer Advisory Board. Some possible opportunities include vaccine development, early-detection technology, single-cell genomic analysis, immunotherapy, a focus on pediatric cancer, and enhanced data sharing.”

To read the full editorial, click here.

On Twitter @denisefulton

FROM NEJM

Better sarcoma outcomes at high-volume centers

BOSTON – In sarcoma as in other cancers, experience counts.

That’s the conclusion of investigators who found that patients with extra-abdominal sarcomas who were treated in high-volume hospitals had half the 30-day mortality rate, higher likelihood of negative surgical margins, and better overall survival, compared with patients treated in low-volume hospitals.

“It appears there is a direct association between hospital volume and short-term as well as long-term outcomes for soft-tissue sarcomas outside the abdomen,” said Dr. Sanjay P. Bagaria of the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla.

The findings support centralization of services at the national level in centers specializing in the management of sarcomas, he said at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium.

Previous studies have shown that patients treated in high-volume centers for cancers of the esophagus, pancreas, and lung have better outcomes than patients treated in low-volume centers, he noted.

Given the rarity of sarcomas, with an incidence of approximately 12,000 in the U.S. annually, their complexity, with more than 60 histologic subtypes, and the multimodality approach required for them, it seemed likely that a positive association between volume and outcomes could be found, Dr. Bagaria said.

He and colleagues queried the U.S. National Cancer Database, a hospital registry of data from more than 1,500 facilities accredited by the Commission on Cancer.

They drew records on all patients diagnosed with extra-abdominal sarcomas from 2003 through 2007 who underwent surgery at the reporting hospitals, and divided the cases into terciles as either low volume (3 or fewer surgical cases per year), medium volume (3.2-11.6 per year), or high volume (12 or more cases per year).

One third (33%) of all cases were concentrated in just 44 high-volume hospitals, which comprised just 4% of the total hospital sample of 1,163. An additional third (34%) of cases were managed among 196 medium-volume hospitals (17% of the hospital sample), and the remaining third (33%) were spread among 923 low-volume hospitals (79%).

The 30-day mortality rates for low-, medium-, and high-volume hospitals, respectively, were 1.7%, 1.1%, and 0.6% (P less than .0001).

Similarly, the rates of negative margins (R0 resections) were 73.%, 78.2%, and 84.2% (P less than .0001).

Five-year overall survival was identical for low- and medium-volume centers (65% each), but was significantly better for patients treated at high-volume centers (69%, P less than .001)

Compared with low-volume centers, patients treated at high-volume centers had an adjusted odds ratio (OR) for 30-day mortality of 0.46 (P = .01), an adjusted OR for R0 margins of 1.87 (P less than .001), and OR for overall mortality of 0.92 (P = .04).

Dr. Bagaria noted that the study was limited by missing data about disease-specific survival and by possible selection bias associated with the choice of Commission on Cancer-accredited institutions, which account for 70% of cancer cases nationwide but comprise one-third of all hospitals.

BOSTON – In sarcoma as in other cancers, experience counts.

That’s the conclusion of investigators who found that patients with extra-abdominal sarcomas who were treated in high-volume hospitals had half the 30-day mortality rate, higher likelihood of negative surgical margins, and better overall survival, compared with patients treated in low-volume hospitals.

“It appears there is a direct association between hospital volume and short-term as well as long-term outcomes for soft-tissue sarcomas outside the abdomen,” said Dr. Sanjay P. Bagaria of the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla.

The findings support centralization of services at the national level in centers specializing in the management of sarcomas, he said at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium.

Previous studies have shown that patients treated in high-volume centers for cancers of the esophagus, pancreas, and lung have better outcomes than patients treated in low-volume centers, he noted.

Given the rarity of sarcomas, with an incidence of approximately 12,000 in the U.S. annually, their complexity, with more than 60 histologic subtypes, and the multimodality approach required for them, it seemed likely that a positive association between volume and outcomes could be found, Dr. Bagaria said.

He and colleagues queried the U.S. National Cancer Database, a hospital registry of data from more than 1,500 facilities accredited by the Commission on Cancer.

They drew records on all patients diagnosed with extra-abdominal sarcomas from 2003 through 2007 who underwent surgery at the reporting hospitals, and divided the cases into terciles as either low volume (3 or fewer surgical cases per year), medium volume (3.2-11.6 per year), or high volume (12 or more cases per year).

One third (33%) of all cases were concentrated in just 44 high-volume hospitals, which comprised just 4% of the total hospital sample of 1,163. An additional third (34%) of cases were managed among 196 medium-volume hospitals (17% of the hospital sample), and the remaining third (33%) were spread among 923 low-volume hospitals (79%).

The 30-day mortality rates for low-, medium-, and high-volume hospitals, respectively, were 1.7%, 1.1%, and 0.6% (P less than .0001).

Similarly, the rates of negative margins (R0 resections) were 73.%, 78.2%, and 84.2% (P less than .0001).

Five-year overall survival was identical for low- and medium-volume centers (65% each), but was significantly better for patients treated at high-volume centers (69%, P less than .001)

Compared with low-volume centers, patients treated at high-volume centers had an adjusted odds ratio (OR) for 30-day mortality of 0.46 (P = .01), an adjusted OR for R0 margins of 1.87 (P less than .001), and OR for overall mortality of 0.92 (P = .04).

Dr. Bagaria noted that the study was limited by missing data about disease-specific survival and by possible selection bias associated with the choice of Commission on Cancer-accredited institutions, which account for 70% of cancer cases nationwide but comprise one-third of all hospitals.

BOSTON – In sarcoma as in other cancers, experience counts.

That’s the conclusion of investigators who found that patients with extra-abdominal sarcomas who were treated in high-volume hospitals had half the 30-day mortality rate, higher likelihood of negative surgical margins, and better overall survival, compared with patients treated in low-volume hospitals.

“It appears there is a direct association between hospital volume and short-term as well as long-term outcomes for soft-tissue sarcomas outside the abdomen,” said Dr. Sanjay P. Bagaria of the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla.

The findings support centralization of services at the national level in centers specializing in the management of sarcomas, he said at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium.

Previous studies have shown that patients treated in high-volume centers for cancers of the esophagus, pancreas, and lung have better outcomes than patients treated in low-volume centers, he noted.

Given the rarity of sarcomas, with an incidence of approximately 12,000 in the U.S. annually, their complexity, with more than 60 histologic subtypes, and the multimodality approach required for them, it seemed likely that a positive association between volume and outcomes could be found, Dr. Bagaria said.

He and colleagues queried the U.S. National Cancer Database, a hospital registry of data from more than 1,500 facilities accredited by the Commission on Cancer.

They drew records on all patients diagnosed with extra-abdominal sarcomas from 2003 through 2007 who underwent surgery at the reporting hospitals, and divided the cases into terciles as either low volume (3 or fewer surgical cases per year), medium volume (3.2-11.6 per year), or high volume (12 or more cases per year).

One third (33%) of all cases were concentrated in just 44 high-volume hospitals, which comprised just 4% of the total hospital sample of 1,163. An additional third (34%) of cases were managed among 196 medium-volume hospitals (17% of the hospital sample), and the remaining third (33%) were spread among 923 low-volume hospitals (79%).

The 30-day mortality rates for low-, medium-, and high-volume hospitals, respectively, were 1.7%, 1.1%, and 0.6% (P less than .0001).

Similarly, the rates of negative margins (R0 resections) were 73.%, 78.2%, and 84.2% (P less than .0001).

Five-year overall survival was identical for low- and medium-volume centers (65% each), but was significantly better for patients treated at high-volume centers (69%, P less than .001)

Compared with low-volume centers, patients treated at high-volume centers had an adjusted odds ratio (OR) for 30-day mortality of 0.46 (P = .01), an adjusted OR for R0 margins of 1.87 (P less than .001), and OR for overall mortality of 0.92 (P = .04).

Dr. Bagaria noted that the study was limited by missing data about disease-specific survival and by possible selection bias associated with the choice of Commission on Cancer-accredited institutions, which account for 70% of cancer cases nationwide but comprise one-third of all hospitals.

Key clinical point: Surgical volume, a surrogate for experience, has been shown to have a direct correlation with patient outcomes for cancers of the esophagus, lung, and pancreas, and this appears to be true for sarcomas as well.

Major finding: Patients treated for sarcoma at high-volume centers had lower 30-day and overall mortality and a higher probability of negative margins than those treated at low-volume centers.

Data source: Retrospective review of data on 14,634 patients treated at 1,163 U.S. hospitals.

Disclosures: The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

CT of chest, extremity effective for sarcoma follow-up

BOSTON – CT scans appear to be effective for detecting local recurrences and pulmonary metastases in patients treated for soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremities, for about a third less than the cost of follow-up with MRI.

In a retrospective study by Dr. Allison Maciver and her colleagues, among 91 patients with soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremity followed with CT, 11 patients had a total of 14 local recurrences detected on CT, and 11 of the recurrences were in patients who were clinically asymptomatic.

Surveillance CT also identified 15 cases of pulmonary metastases, and 4 incidental second primary malignancies, Dr. Maciver of the Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Buffalo, N.Y., and her coinvestigators found, and there was only one false-positive recurrence.

The benefits of CT over extremity MRI in this population include decreased imaging time, lower cost, and a larger field of view, allowing for detection of second primary malignancies, she noted in a poster session at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium.

Many sarcomas of the extremities are highly aggressive, and timely detection of local recurrences could improve chances for limb-sparing salvage therapies. Although MRI has typically been used to follow patients with sarcomas, it is expensive and has a limited field of view, Dr. Maciver said.

In addition, the risk of pulmonary metastases with some soft-tissue sarcomas is high, necessitating the use of chest CT as a surveillance tool.

To see whether CT scans of the chest and extremities could be a cost-effective surveillance strategy for both local recurrences and pulmonary metastases, the investigators did a retrospective study of a prospective database of patients who underwent surgical resection for soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremities from 2001 through 2014 and who had CT as the primary follow-up imaging modality.

They identified a total of 91 high-risk patients followed for a median of 50.5 months. The patients had an estimated 5-year freedom from local recurrence of 82%, and from distant recurrence of 80%. Five-year overall survival was 76%.

Of the 15 patients found on CT to have pulmonary metastases, there were 4 incidentally discovered second primary cancers, including 1 each of non–small cell lung cancer, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, Merkel cell carcinomatosis, and myxofibrosarcoma. There were no false-positive pulmonary metastases.

The estimated cost of 10 years of surveillance, based on 2014 gross technical costs, was $64,969 per patient for chest CT and extremity MRI, compared with $41,595 per patient for chest and extremity CT surveillance, a potential cost savings with the CT-only strategy of $23,374 per patient.

The investigators said that the overall benefits of CT, including the cost savings in an accountable care organization model, “appear to outweigh the slightly increased radiation exposure.”

The study was internally funded. The authors reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

BOSTON – CT scans appear to be effective for detecting local recurrences and pulmonary metastases in patients treated for soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremities, for about a third less than the cost of follow-up with MRI.

In a retrospective study by Dr. Allison Maciver and her colleagues, among 91 patients with soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremity followed with CT, 11 patients had a total of 14 local recurrences detected on CT, and 11 of the recurrences were in patients who were clinically asymptomatic.

Surveillance CT also identified 15 cases of pulmonary metastases, and 4 incidental second primary malignancies, Dr. Maciver of the Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Buffalo, N.Y., and her coinvestigators found, and there was only one false-positive recurrence.

The benefits of CT over extremity MRI in this population include decreased imaging time, lower cost, and a larger field of view, allowing for detection of second primary malignancies, she noted in a poster session at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium.

Many sarcomas of the extremities are highly aggressive, and timely detection of local recurrences could improve chances for limb-sparing salvage therapies. Although MRI has typically been used to follow patients with sarcomas, it is expensive and has a limited field of view, Dr. Maciver said.

In addition, the risk of pulmonary metastases with some soft-tissue sarcomas is high, necessitating the use of chest CT as a surveillance tool.

To see whether CT scans of the chest and extremities could be a cost-effective surveillance strategy for both local recurrences and pulmonary metastases, the investigators did a retrospective study of a prospective database of patients who underwent surgical resection for soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremities from 2001 through 2014 and who had CT as the primary follow-up imaging modality.

They identified a total of 91 high-risk patients followed for a median of 50.5 months. The patients had an estimated 5-year freedom from local recurrence of 82%, and from distant recurrence of 80%. Five-year overall survival was 76%.

Of the 15 patients found on CT to have pulmonary metastases, there were 4 incidentally discovered second primary cancers, including 1 each of non–small cell lung cancer, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, Merkel cell carcinomatosis, and myxofibrosarcoma. There were no false-positive pulmonary metastases.

The estimated cost of 10 years of surveillance, based on 2014 gross technical costs, was $64,969 per patient for chest CT and extremity MRI, compared with $41,595 per patient for chest and extremity CT surveillance, a potential cost savings with the CT-only strategy of $23,374 per patient.

The investigators said that the overall benefits of CT, including the cost savings in an accountable care organization model, “appear to outweigh the slightly increased radiation exposure.”

The study was internally funded. The authors reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

BOSTON – CT scans appear to be effective for detecting local recurrences and pulmonary metastases in patients treated for soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremities, for about a third less than the cost of follow-up with MRI.

In a retrospective study by Dr. Allison Maciver and her colleagues, among 91 patients with soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremity followed with CT, 11 patients had a total of 14 local recurrences detected on CT, and 11 of the recurrences were in patients who were clinically asymptomatic.

Surveillance CT also identified 15 cases of pulmonary metastases, and 4 incidental second primary malignancies, Dr. Maciver of the Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Buffalo, N.Y., and her coinvestigators found, and there was only one false-positive recurrence.

The benefits of CT over extremity MRI in this population include decreased imaging time, lower cost, and a larger field of view, allowing for detection of second primary malignancies, she noted in a poster session at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium.

Many sarcomas of the extremities are highly aggressive, and timely detection of local recurrences could improve chances for limb-sparing salvage therapies. Although MRI has typically been used to follow patients with sarcomas, it is expensive and has a limited field of view, Dr. Maciver said.

In addition, the risk of pulmonary metastases with some soft-tissue sarcomas is high, necessitating the use of chest CT as a surveillance tool.

To see whether CT scans of the chest and extremities could be a cost-effective surveillance strategy for both local recurrences and pulmonary metastases, the investigators did a retrospective study of a prospective database of patients who underwent surgical resection for soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremities from 2001 through 2014 and who had CT as the primary follow-up imaging modality.

They identified a total of 91 high-risk patients followed for a median of 50.5 months. The patients had an estimated 5-year freedom from local recurrence of 82%, and from distant recurrence of 80%. Five-year overall survival was 76%.

Of the 15 patients found on CT to have pulmonary metastases, there were 4 incidentally discovered second primary cancers, including 1 each of non–small cell lung cancer, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, Merkel cell carcinomatosis, and myxofibrosarcoma. There were no false-positive pulmonary metastases.

The estimated cost of 10 years of surveillance, based on 2014 gross technical costs, was $64,969 per patient for chest CT and extremity MRI, compared with $41,595 per patient for chest and extremity CT surveillance, a potential cost savings with the CT-only strategy of $23,374 per patient.

The investigators said that the overall benefits of CT, including the cost savings in an accountable care organization model, “appear to outweigh the slightly increased radiation exposure.”

The study was internally funded. The authors reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Key clinical point: Lower-cost CT scans of the extremity and chest appear to be effective for surveillance of patients following resection of soft-tissue sarcomas.

Major finding: Of 91 patients with soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremity followed with CT, 11 had a total of 14 local recurrences detected. Of the recurrences, 11 were clinically asymptomatic.

Data source: A retrospective study of a prospectively maintained surgical database.

Disclosures: The study was internally funded. The authors reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Bone sarcomas are not just for kids

The treatment of bone sarcomas in adults is guided as much by experience as it is by medical evidence, say sarcoma experts who should know.

“[L]arge prospective clinical trials in adults with bone sarcomas are lacking. Although translation of findings in pediatric studies to adults is possible, it is not clear if findings from pediatric studies truly apply to adults,” Dr. Michael J. Wagner and his colleagues from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston said.

In a review article in the Journal of Oncology Practice, the investigators outline how they have melded lessons learned from pediatric clinical trials with clinical experience treating adults with bone sarcomas.

Adult osteosarcomas

Although the peak incidence of osteosarcoma occurs in adolescents and young adults, some studies of various chemotherapy regimens have included middle-aged adults and even some patients in their 90s, although many have excluded patients older than 30, the authors noted.

In adults, and in children and adolescents and young adults, chemotherapy and definitive surgical resection are the mainstays of treatment, with the exception of osteosarcomas of the jaw, which are generally treated with resection alone. For the past three decades, adults with high-grade osteosarcomas have been treated with chemotherapy containing doxorubicin, cisplatin, high-dose methotrexate, and ifosfamide.

“However, important differences to consider in the treatment of older patients include, but are not limited to, the increased incidence of histologic variants of osteosarcoma (including secondary osteosarcomas) and medical comorbidities that may limit tolerance of older adults to dose-intense chemotherapy,” wrote Dr. Wagner and his colleagues (J Oncol Pract. 2016 Mar. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.009944).

High-grade localized osteosarcoma is treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, followed by limb-sparing surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy.

A poor response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, defined as tumor necrosis of less than 90% at resection, is a marker for poor prognosis.

The authors previously reported that for patients with a poor response following a regimen of doxorubicin intravenous infusion at 90 mg/m2 over 96 hours plus cisplatin infused intra-arterially at 120-160 mg/m2 over 2 to 24 hours, the addition of high-dose methotrexate and ifosfamide resulted in significant improvement in continuous relapse-free survival.

At MD Anderson, adults with osteosarcoma receive preoperative chemotherapy with doxorubicin and cisplatin for three to four cycles and then undergo surgical resection. Those who have a good response go on to receive adjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin 75 mg/m2 and ifosfamide 10g/m2 for four cycles. Patients who have a poor response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy receive alternating courses of ifosfamide 14 g/m2, high-dose methotrexate 10 to 12 g/m2, and doxorubicin 75 mg/m2 and ifosfamide 10 g/m2 for up to 12 cycles or until intolerable adverse events.

Patients with metastatic relapsed/refractory osteosarcoma have 5-year overall survival rates ranging from 15% to 20%, the authors noted, adding that chemotherapy has “limited efficacy” in this setting.

Targeted agents, including the tyrosine kinase inhibitor sorafenib (Nexavar) and the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor everolimus (Afinitor) have been evaluated in phase II trials.

Ewing sarcoma

Evidence from clinical trials of chemotherapy regimens in Ewing sarcoma show that patients 18 and older tend to have less favorable outcomes than younger patients when treated with dose-dense regimens, the authors noted.

Their practice is to treat adults with Ewing sarcoma with upfront vincristine 2 mg on day 1, doxorubicin 75 to 90 mg/m2 in a continuous 72-hour infusion, and ifosfamide 2.5 g/m2 given over 3 hours daily for four doses, followed by surgery, and adjuvant chemotherapy with an ifosfamide-based regimen.

Giant cell tumors of bone

These rare osteolytic tumors are treated with surgery as the primary therapy if they are resectable. Patients with metastases (which paradoxically, are usually histologically benign) as well as those who have tumors in areas where surgery may cause unacceptable morbidities may be treated with serial embolization, denosumab (Xgeva), interferon, or pegylated interferon.

Chondrosarcoma

The so-called “conventional” sub-type of chondrosarcomas are not generally responsive to cytotoxic chemotherapy and best managed with surgery alone, the authors say. However, patients with mesenchymal chondrosarcoma are treated similarly to patients with Ewing sarcoma, and those with the dedifferentiated subtype are treated with an osteosarcoma regimens.

The authors noted that point mutations in IDH1 and IDH2 have recently been discovered in chondrosarcomas, making them potential targets for an experimental IDH-1 inhibitor.

Dr. Wagner and coauthor Dr. J. Andrew Livingston reported no relevant disclosures. Coauthors Dr. Shreyaskumar R. Patel and Dr. Robert S. Benjamin reported consulting, advisory roles, research funding, or ownership interests in various pharmaceutical companies.

The treatment of bone sarcomas in adults is guided as much by experience as it is by medical evidence, say sarcoma experts who should know.

“[L]arge prospective clinical trials in adults with bone sarcomas are lacking. Although translation of findings in pediatric studies to adults is possible, it is not clear if findings from pediatric studies truly apply to adults,” Dr. Michael J. Wagner and his colleagues from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston said.

In a review article in the Journal of Oncology Practice, the investigators outline how they have melded lessons learned from pediatric clinical trials with clinical experience treating adults with bone sarcomas.

Adult osteosarcomas

Although the peak incidence of osteosarcoma occurs in adolescents and young adults, some studies of various chemotherapy regimens have included middle-aged adults and even some patients in their 90s, although many have excluded patients older than 30, the authors noted.

In adults, and in children and adolescents and young adults, chemotherapy and definitive surgical resection are the mainstays of treatment, with the exception of osteosarcomas of the jaw, which are generally treated with resection alone. For the past three decades, adults with high-grade osteosarcomas have been treated with chemotherapy containing doxorubicin, cisplatin, high-dose methotrexate, and ifosfamide.

“However, important differences to consider in the treatment of older patients include, but are not limited to, the increased incidence of histologic variants of osteosarcoma (including secondary osteosarcomas) and medical comorbidities that may limit tolerance of older adults to dose-intense chemotherapy,” wrote Dr. Wagner and his colleagues (J Oncol Pract. 2016 Mar. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.009944).

High-grade localized osteosarcoma is treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, followed by limb-sparing surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy.

A poor response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, defined as tumor necrosis of less than 90% at resection, is a marker for poor prognosis.

The authors previously reported that for patients with a poor response following a regimen of doxorubicin intravenous infusion at 90 mg/m2 over 96 hours plus cisplatin infused intra-arterially at 120-160 mg/m2 over 2 to 24 hours, the addition of high-dose methotrexate and ifosfamide resulted in significant improvement in continuous relapse-free survival.

At MD Anderson, adults with osteosarcoma receive preoperative chemotherapy with doxorubicin and cisplatin for three to four cycles and then undergo surgical resection. Those who have a good response go on to receive adjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin 75 mg/m2 and ifosfamide 10g/m2 for four cycles. Patients who have a poor response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy receive alternating courses of ifosfamide 14 g/m2, high-dose methotrexate 10 to 12 g/m2, and doxorubicin 75 mg/m2 and ifosfamide 10 g/m2 for up to 12 cycles or until intolerable adverse events.

Patients with metastatic relapsed/refractory osteosarcoma have 5-year overall survival rates ranging from 15% to 20%, the authors noted, adding that chemotherapy has “limited efficacy” in this setting.

Targeted agents, including the tyrosine kinase inhibitor sorafenib (Nexavar) and the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor everolimus (Afinitor) have been evaluated in phase II trials.

Ewing sarcoma

Evidence from clinical trials of chemotherapy regimens in Ewing sarcoma show that patients 18 and older tend to have less favorable outcomes than younger patients when treated with dose-dense regimens, the authors noted.

Their practice is to treat adults with Ewing sarcoma with upfront vincristine 2 mg on day 1, doxorubicin 75 to 90 mg/m2 in a continuous 72-hour infusion, and ifosfamide 2.5 g/m2 given over 3 hours daily for four doses, followed by surgery, and adjuvant chemotherapy with an ifosfamide-based regimen.

Giant cell tumors of bone

These rare osteolytic tumors are treated with surgery as the primary therapy if they are resectable. Patients with metastases (which paradoxically, are usually histologically benign) as well as those who have tumors in areas where surgery may cause unacceptable morbidities may be treated with serial embolization, denosumab (Xgeva), interferon, or pegylated interferon.

Chondrosarcoma

The so-called “conventional” sub-type of chondrosarcomas are not generally responsive to cytotoxic chemotherapy and best managed with surgery alone, the authors say. However, patients with mesenchymal chondrosarcoma are treated similarly to patients with Ewing sarcoma, and those with the dedifferentiated subtype are treated with an osteosarcoma regimens.

The authors noted that point mutations in IDH1 and IDH2 have recently been discovered in chondrosarcomas, making them potential targets for an experimental IDH-1 inhibitor.

Dr. Wagner and coauthor Dr. J. Andrew Livingston reported no relevant disclosures. Coauthors Dr. Shreyaskumar R. Patel and Dr. Robert S. Benjamin reported consulting, advisory roles, research funding, or ownership interests in various pharmaceutical companies.

The treatment of bone sarcomas in adults is guided as much by experience as it is by medical evidence, say sarcoma experts who should know.

“[L]arge prospective clinical trials in adults with bone sarcomas are lacking. Although translation of findings in pediatric studies to adults is possible, it is not clear if findings from pediatric studies truly apply to adults,” Dr. Michael J. Wagner and his colleagues from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston said.

In a review article in the Journal of Oncology Practice, the investigators outline how they have melded lessons learned from pediatric clinical trials with clinical experience treating adults with bone sarcomas.

Adult osteosarcomas

Although the peak incidence of osteosarcoma occurs in adolescents and young adults, some studies of various chemotherapy regimens have included middle-aged adults and even some patients in their 90s, although many have excluded patients older than 30, the authors noted.

In adults, and in children and adolescents and young adults, chemotherapy and definitive surgical resection are the mainstays of treatment, with the exception of osteosarcomas of the jaw, which are generally treated with resection alone. For the past three decades, adults with high-grade osteosarcomas have been treated with chemotherapy containing doxorubicin, cisplatin, high-dose methotrexate, and ifosfamide.

“However, important differences to consider in the treatment of older patients include, but are not limited to, the increased incidence of histologic variants of osteosarcoma (including secondary osteosarcomas) and medical comorbidities that may limit tolerance of older adults to dose-intense chemotherapy,” wrote Dr. Wagner and his colleagues (J Oncol Pract. 2016 Mar. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.009944).

High-grade localized osteosarcoma is treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, followed by limb-sparing surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy.

A poor response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, defined as tumor necrosis of less than 90% at resection, is a marker for poor prognosis.

The authors previously reported that for patients with a poor response following a regimen of doxorubicin intravenous infusion at 90 mg/m2 over 96 hours plus cisplatin infused intra-arterially at 120-160 mg/m2 over 2 to 24 hours, the addition of high-dose methotrexate and ifosfamide resulted in significant improvement in continuous relapse-free survival.

At MD Anderson, adults with osteosarcoma receive preoperative chemotherapy with doxorubicin and cisplatin for three to four cycles and then undergo surgical resection. Those who have a good response go on to receive adjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin 75 mg/m2 and ifosfamide 10g/m2 for four cycles. Patients who have a poor response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy receive alternating courses of ifosfamide 14 g/m2, high-dose methotrexate 10 to 12 g/m2, and doxorubicin 75 mg/m2 and ifosfamide 10 g/m2 for up to 12 cycles or until intolerable adverse events.

Patients with metastatic relapsed/refractory osteosarcoma have 5-year overall survival rates ranging from 15% to 20%, the authors noted, adding that chemotherapy has “limited efficacy” in this setting.

Targeted agents, including the tyrosine kinase inhibitor sorafenib (Nexavar) and the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor everolimus (Afinitor) have been evaluated in phase II trials.

Ewing sarcoma

Evidence from clinical trials of chemotherapy regimens in Ewing sarcoma show that patients 18 and older tend to have less favorable outcomes than younger patients when treated with dose-dense regimens, the authors noted.

Their practice is to treat adults with Ewing sarcoma with upfront vincristine 2 mg on day 1, doxorubicin 75 to 90 mg/m2 in a continuous 72-hour infusion, and ifosfamide 2.5 g/m2 given over 3 hours daily for four doses, followed by surgery, and adjuvant chemotherapy with an ifosfamide-based regimen.

Giant cell tumors of bone

These rare osteolytic tumors are treated with surgery as the primary therapy if they are resectable. Patients with metastases (which paradoxically, are usually histologically benign) as well as those who have tumors in areas where surgery may cause unacceptable morbidities may be treated with serial embolization, denosumab (Xgeva), interferon, or pegylated interferon.

Chondrosarcoma

The so-called “conventional” sub-type of chondrosarcomas are not generally responsive to cytotoxic chemotherapy and best managed with surgery alone, the authors say. However, patients with mesenchymal chondrosarcoma are treated similarly to patients with Ewing sarcoma, and those with the dedifferentiated subtype are treated with an osteosarcoma regimens.

The authors noted that point mutations in IDH1 and IDH2 have recently been discovered in chondrosarcomas, making them potential targets for an experimental IDH-1 inhibitor.

Dr. Wagner and coauthor Dr. J. Andrew Livingston reported no relevant disclosures. Coauthors Dr. Shreyaskumar R. Patel and Dr. Robert S. Benjamin reported consulting, advisory roles, research funding, or ownership interests in various pharmaceutical companies.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ONCOLOGY PRACTICE

Key clinical point: Sarcomas of bone have their peak incidence in children and adolescents, but are also seen in adults.

Major finding: Findings from clinical trials in pediatric bone sarcomas may not be applicable to treatment of adults with the same malignancies.

Data source: Review of the medical literature and of clinical experience at the authors’ center.

Disclosures: Dr. Wagner and coauthor Dr. J. Andrew Livingston reported no relevant disclosures. Coauthors Dr. Shreyaskumar R. Patel and Dr. Robert S. Benjamin reported consulting, advisory roles, research funding, or ownership interests in various pharmaceutical companies.

Trabectedin found to benefit patients with uterine leiomyosarcoma

SAN DIEGO – Among patients with uterine leiomyosarcoma who underwent prior chemotherapy, treatment with trabectedin resulted in superior disease control, with significantly longer progression-free survival, compared with dacarbazine, a phase III trial showed.

“Trabectedin is an important new treatment option for patients with advanced uterine LMS after anthracycline-containing treatment,” lead study author Dr. Martee L. Hensley said at annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology.

Trabectedin, which is marketed by Janssen Products and is also known as ET743, has a novel mechanism of action that “distorts DNA structure resulting in the initiation of DNA repair,” explained Dr. Hensley, a surgical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York. “At the same time it binds and inhibits repair mechanisms, thereby activating apoptosis. In addition, trabectedin inhibits transcriptional activation and can modify the tumor microenvironment.”

ET743-SAR-3007 was the largest randomized, phase III study in soft tissue sarcoma. It found that trabectedin demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in progression-free survival (PFS), compared with dacarbazine (4.2 months vs. 1.5 months; hazard ratio = .55; P less than .001). The results led to FDA approval of trabectedin for the treatment of patients with leiomyosarcoma (LMS) or liposarcoma (LPS), after prior anthracycline therapy. In addition, a previously reported subgroup analysis demonstrated equivalent PFS benefit in patients with either LMS (HR = .56) or LPS HR = .55). However, the majority of that study population (73%) had LMS, and most of those (40%) were uterine LMS. The purpose of the current analysis was the subgroup of patients 232 with uterine LMS who were enrolled in ET743-SAR-3007, which was conducted in 90 sites on four different countries.