User login

Primary renal synovial sarcoma – a diagnostic dilemma

Soft tissue sarcomas are rare mesenchymal tumors that comprise 1% of all malignancies. Synovial sarcoma accounts for 5% to 10% of adult soft tissue sarcomas and usually occurs in close association with joint capsules, tendon sheaths, and bursa in the extremities of young and middle-aged adults.1 Synovial sarcomas have been reported in other unusual sites, including the head and neck, thoracic and abdominal wall, retroperitoneum, bone, pleura, and visceral organs such as the lung, prostate, or kidney.2 Primary renal synovial sarcoma is an extremely rare tumor accounting for <2% of all malignant renal tumors.3 To the best of our knowledge, fewer than 50 cases of primary renal synovial sarcoma have been described in the English literature.4 It presents as a diagnostic dilemma because of the dearth of specific clinical and imaging findings and is often confused with benign and malignant tumors. The differential diagnosis includes angiomyolipoma, renal cell carcinoma with sarcomatoid differentiation, metastatic sarcoma, hemangiopericytoma, malignant solitary fibrous tumor, Wilms tumor, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. Hence, a combination of histomorphologic, immunohistochemical, cytogenetic, and molecular studies that show a unique chromosomal translocation t(X;18) (p11;q11) is imperative in the diagnosis of primary renal synovial sarcoma.4 In the present report, we present the case of a 38-year-old man who was diagnosed with primary renal synovial sarcoma.

Case presentation and summary

A 38-year-old man with a medical history of gastroesophageal reflux disease and Barrett’s esophagus presented to our hospital for the first time with persistent and progressive right-sided flank and abdominal pain that was aggravated after a minor trauma to the back. There was no associated hematuria or dysuria.

Of note is that he had experienced intermittent flank pain for 2 years before this transfer. He had initially been diagnosed at his local hospital close to his home by ultrasound with an angiomyolipoma of 2 × 3 cm arising from the upper pole of his right kidney, which remained stable on repeat sonograms. About 22 months after his initial presentation at his local hospital, the flank pain increased, and a computed-tomographic (CT) scan revealed a perinephric hematoma that was thought to originate from a ruptured angiomyolipoma. He subsequently underwent embolization, but his symptoms recurred soon after. He presented again to his local hospital where CT imaging revealed a significant increase in the size of the retroperitoneal mass, and findings were suggestive of a hematoma. Subsequent angiogram did not reveal active extravasation, so a biopsy was performed.

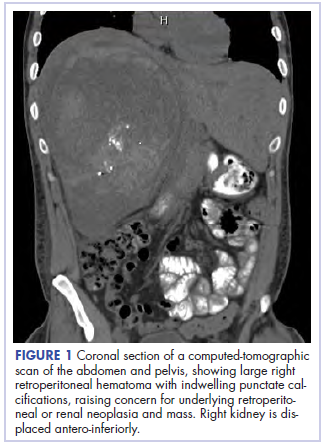

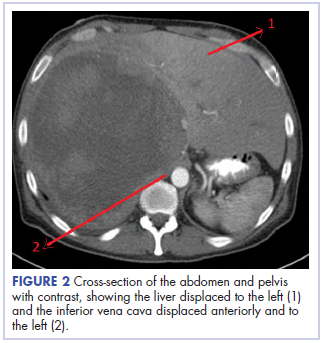

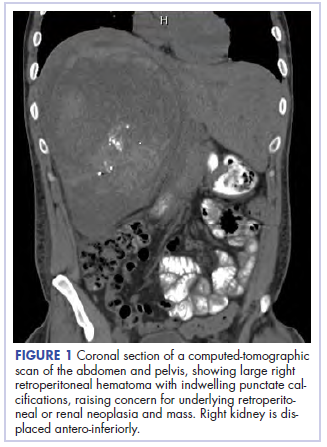

Before confirmatory pathologic evaluation could be completed, the patient presented to his local hospital again in excruciating pain. A CT scan of his abdomen and pelvis demonstrated a massive subacute on chronic hematoma in the right retroperitoneum measuring 22 × 19 × 18 cm, with calcifications originating from an upper pole right renal neoplasm. The right kidney was displaced antero-inferiorly, and the inferior vena cava was displaced anteriorly and to the left. The preliminary pathology returned with findings suggestive of sarcoma (Figures 1 and 2).

The patient was then transferred to our institution, where he was evaluated by medical and surgical oncology. A CT scan of the chest and magnetic-resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain did not reveal metastatic disease. He underwent exploratory laparotomy that involved the resection of a 22-cm retroperitoneal mass, right nephrectomy, right adrenalectomy, partial right hepatectomy, and a full thickness resection of the right postero-inferior diaphragm followed by mesh repair because of involvement by the tumor.

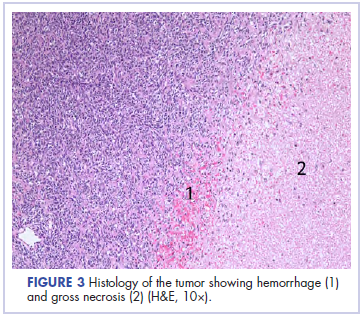

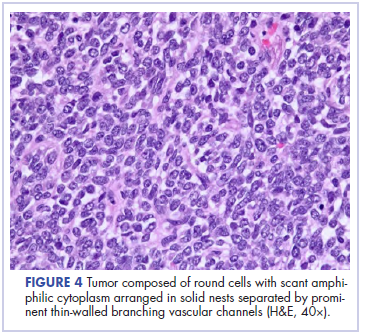

In its entirety, the specimen was a mass of 26 × 24 × 14 cm. It was sectioned to show extensively necrotic and hemorrhagic variegated white to tan-red parenchyma (Figure 3). Histology revealed a poorly differentiated malignant neoplasm composed of round cells with scant amphophilic cytoplasm arranged in solid, variably sized nests separated by prominent thin-walled branching vascular channels (Figure 4). The mitotic rate was high. It was determined to be a histologically ungraded sarcoma according to the French Federation of Comprehensive Cancer Centers system of grading soft tissue sarcomas; the margins were indeterminate. Immunohistochemistry was positive for EMA, TLE1, and negative for AE1/AE3, S100, STAT6, and Nkx2.2. Molecular pathology fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis demonstrated positivity for SS18 gene rearrangement (SS18-SSX1 fusion).

After recovering from surgery, the patient received adjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin and ifosfamide. It has been almost 16 months since we first saw this patient. He was started on doxorubicin 20 mg/m2 on days 1 to 4, ifosfamide 2,500 mg on days 1 to 4, and mesna 800 mg on days 1 to 4, for a total of 6 cycles. He did well for the first 5 months, after which he developed disease recurrence in the postoperative nephrectomy bed (a biopsy showed it to be recurrent synovial sarcoma) as well as pulmonary nodules, for which he was started on trabectedin 1.5 mg/m2 every 3 weeks. Two months later, a CT scan showed an increase in the size of his retroperitoneal mass, and the treatment was changed to pazopanib 400 mg daily orally, on which he remained at the time of publication.

Discussion

Synovial sarcoma is the fourth most common type of soft tissue sarcoma, accounting for 2.5% to 10.5% of all primary soft tissue malignancies worldwide. It occurs most frequently in adolescents and young adults, with most patients presenting between the ages of 15 and 40 years. Median age of presentation is 36 years. Despite the nomenclature, synovial sarcoma does not arise in intra-articular locations but typically occurs in proximity to joints in the extremities. Synovial sarcomas are less commonly described in other sites, including the head and neck, mediastinum, intraperitoneum, retroperitoneum, lung, pleura, and kidney.4,5 Renal synovial sarcoma was first described in a published article by Argani and colleagues in 2000.5

Adult renal mesenchymal tumors are classified into benign and malignant tumors on the basis of the histologic features and clinicobiologic behavior.6,7 The benign esenchymal renal tumors include angiomyolipoma, leiomyoma, hemangioma, lymphangioma, juxtaglomerular cell tumor, renomedullary interstitial cell tumor (medullary fibroma), lipoma, solitary fibrous tumor, and schwannoma. Malignant renal tumors of mesenchymal origin include leiomyosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, angiosarcoma, osteosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, solitary fibrous tumor, and synovial sarcoma.

Most of these tumor types cause the same nonspecific symptoms in patients – abdominal pain, flank pain, abdominal fullness, a palpable mass, and hematuria – although they can be clinically silent. The average duration of symptoms in synovial sarcoma is 2 to 4 years.8 The long duration of symptoms and initial slow growth of synovial sarcomas may give a false impression of a benign process.

A preoperative radiological diagnosis of primary renal synovial sarcoma may be suspected by analyzing the tumor’s growth patterns on CT scans.9 Renal synovial sarcomas often appear as large, well-defined soft tissue masses that can extend into the renal pelvis or into the perinephric region.9 A CT scan may identify soft tissue calcifications, especially subtle ones in areas where the tumor anatomy is complex. A CT scan may also reveal areas of hemorrhage, necrosis, or cyst formation within the tumor, and can easily confirm bone involvement. Intravenous contrast may help in differentiating the mass from adjacent muscle and neurovascular complex.9,10 On MRI, renal synovial sarcomas are often described as nonspecific heterogeneous masses, although they may also exhibit heterogeneous enhancement of hemorrhagic areas, calcifications, and air-fluid levels (known as “triple sign”) as well as septae. The triple sign may be identified as areas of low, intermediate, and high signal intensity, correlating with areas of hemorrhage, calcification, and air-fluid level.9,10 Signal intensity is about equal to that of skeletal muscle on T1-weighted MRI and higher than that of subcutaneous fat on T2-weighted MRI.

In the present case, the tumor was initially misdiagnosed as an angiomyolipoma, the most common benign tumor of the kidney. Angiomyolipomas are usually solid triphasic tumors arising from the renal cortex and are composed of 3 major elements: dysmorphic blood vessels, smooth muscle components, and adipose tissue. When angiomyolipomas are large enough, they are readily recognized by the identification of macroscopic fat within the tumor, either by CT scan or MRI.11 When they are small, they may be difficult to distinguish from a small cyst on CT because of volume averaging.

On pathology, synovial sarcoma has dual epithelial and mesenchymal differentiation. They are frequently multi-lobulated, and areas of necrosis, hemorrhage, and cyst formation are also common. There are 3 main histologic subtypes of synovial sarcoma: biphasic (20%-30%), monophasic (50%-60%), and poorly differentiated (15%-25%). Poorly differentiated synovial sarcomas are generally epithelioid in morphology, have high mitotic activity (usually 10-20 mitoses/10 high-power field; range is <5 for well differentiated, low-grade tumors), and can be confused with round cell tumors such as Ewing sarcoma. Poorly differentiated synovial sarcomas are high-grade tumors.

Immunohistochemical studies can confirm the pathological diagnosis. Synovial sarcomas usually stain positive for Bcl2, CD99/Mic2, CD56, Vim, and focally for EMA but negatively for desmin, actin, WT1, S-100, CD34, and CD31.5 Currently, the gold standard for diagnosis and hallmark for synovial sarcomas are the t (X;18) translocation and SYT-SSX gene fusion products (SYT-SSX1 in 67% and SYT-SSX2 in 33% of cases). These can be detected either by FISH or reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. This genetic alteration is identified in more than 90% of synovial sarcomas and is highly specific.

The role of SYT-SSX gene fusion in the pathogenesis of synovial sarcoma is an active area of investigation. The fusion of SYT with SSX translates into a fusion protein that binds to the transcription activator SMARCA4 that is involved in chromatin remodeling, thus displacing both the wildtype SYT and the tumor suppressor gene SMARCB1. The modified protein complex then binds at several super-enhancer loci, unlocking suppressed genes such as Sox2, which is known to be necessary for synovial sarcoma proliferation. Alterations in SMARCB1 are involved in several cancer types, implicating this event as a driver of these malignancies.12 This results in a global alteration in chromatin remodeling that needs to be better understood to design targeted therapies.

The clinical course of synovial sarcoma, regardless of the tissue of origin, is typically poor. Multiple clinical and pathologic factors, including tumor size, location, patient age, and presence of poorly differentiated areas, are thought to have prognostic significance. A tumor size of more than 5 cm at presentation has the greatest impact on prognosis, with studies showing 5-year survival rates of 64% for patients with tumors smaller than 5 cm and 26% for patients with masses greater than 5 cm.13,14 High-grade synovial sarcoma is favored in tumors that have cystic components, hemorrhage, and fluid levels and the triple sign.

Patients with tumors in the extremities have a more favorable prognosis than those with lesions in the head and neck area or axially, a feature that likely reflects better surgical control available for extremity lesions. Patient age of less than 15 to 20 years is also associated with a better long-term prognosis.15,16 Varela-Duran and Enzinger17 reported that the presence of extensive calcifications suggests improved long-term survival, with 5-year survival rates of 82% and decreased rates of local recurrence (32%) and metastatic disease (29%). The poorly differentiated subtype is associated with a worsened prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of 20% through 30%.18,19 Other pathologic factors associated with worsened prognosis include presence of rhabdoid cells, extensive tumor necrosis, high nuclear grade, p53 mutations, and high mitotic rate (>10 mitoses/10 high-power field). More recently, the gene fusion type SYT-SSX2 (more common in monophasic lesions) has been associated with an improved prognosis, compared with that for SYT-SSX1, and an 89% metastasis-free survival.20

Although there are no guidelines for the treatment of primary renal synovial sarcoma because of the limited number of cases reported, surgery is considered the first choice. Adjuvant chemotherapy with an anthracycline (doxorubicin or epirubicin) combined with ifosfamide has been the most frequently used regimen in published cases, especially in those in which patients have poor prognostic factors as mentioned above.

Overall, the 5-year survival rate ranges from 36% to 76%.14 The clinical course of synovial sarcoma is characterized by a high rate of local recurrence (30%-50%) and metastatic disease (41%). Most metastases occur within the first 2 to 5 years after treatment cessation. Metastases are present in 16% to 25% of patients at their initial presentation, with the most frequent metastatic site being the lung, followed by the lymph nodes (4%-18%) and bone (8%-11%).

Conclusion

Primary renal synovial sarcoma is extremely rare, and preoperative diagnosis is difficult in the absence of specific clinical or imaging findings. A high index of suspicion combined with pathologic, immunohistochemical, cytogenetic, and molecular studies is essential for accurate diagnosis and subsequent treatment planning. The differential diagnosis of renal synovial sarcoma can be extensive, and our experience with this patient illustrates the diagnostic dilemma associated with renal synovial sarcoma.

1. Majumder A, Dey S, Khandakar B, Medda S, Chandra Paul P. Primary renal synovial sarcoma: a rare tumor with an atypical presentation. Arch Iran Med. 2014;17(10):726-728.

2. Fetsch JF, Meis JM. Synovial sarcoma of the abdominal wall. Cancer. 1993;72(2):469 477.

3. Wang Z, Zhong Z, Zhu L, et al. Primary synovial sarcoma of the kidney: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2015;10(6):3542-3544.

4. Abbas M, Dämmrich ME, Braubach P, et al. Synovial sarcoma of the kidney in a young patient with a review of the literature. Rare tumors. 2014;6(2):5393

5. Argani P, Faria PA, Epstein JI, et al. Primary renal synovial sarcoma: molecular and morphologic delineation of an entity previously included among embryonal sarcomas of the kidney. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24(8):1087-1096.

6. Eble JN, Sauter G, Epstein JI, Sesterhenn IA, eds. World Health Organization classification of tumours: pathology and genetics of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs. Lyon, France: IARC; 2004.

7. Tamboli P, Ro JY, Amin MB, Ligato S, Ayala AG. Benign tumors and tumor-like lesions of the adult kidney. Part II: benign mesenchymal and mixed neoplasms, and tumor-like lesions. Adv Anat Pathol. 2000;7(1):47-66.

8. Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Malignant soft tissue tumors of uncertain type. In: Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, eds. Enzinger and Weiss’s soft tissue tumors. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby, 2001; 1483-1565.

9. Lacovelli R, Altavilla A, Ciardi A, et al. Clinical and pathological features of primary renal synovial sarcoma: analysis of 64 cases from 11 years of medical literature. BJU Int. 2012;110(10):1449-1454.

10. Alhazzani AR, El-Sharkawy MS, Hassan H. Primary retroperitoneal synovial sarcoma in CT and MRI. Urol Ann. 2010;2(1):39-41.

11. Katabathina VS, Vikram R, Nagar AM, Tamboli P, Menias CO, Prasad SR. Mesenchymal neoplasms of the kidney in adults: imaging spectrum with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2010;30(6):1525-1540.

12. Sápi Z, Papp G, Szendrői M, et al. Epigenetic regulation of SMARCB1 by miR-206, -381 and -671- 5p is evident in a variety of SMARCB1 immunonegative soft tissue sarcomas, while miR-765 appears specific for epithelioid sarcoma. A miRNA study of 223 soft tissue sarcomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2016;55(10):786-802.

13. Ferrari A, Gronchi A, Casanova M, et al. Synovial sarcoma: a retrospective analysis of 271 patients of all ages treated at a single institution. Cancer. 2004;101(3):627-634.

14. Rangheard AS, Vanel D, Viala J, Schwaab G, Casiraghi O, Sigal R. Synovial sarcomas of the head and neck: CT and MR imaging findings of eight patients. Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22(5):851-857.

15. Oda Y, Hashimoto H, Tsuneyoshi M, Takeshita S. Survival in synovial sarcoma: a multivariate study of prognostic factors with special emphasis on the comparison between early death and long-term survival. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17(1):35-44.

16. Raney RB. Synovial sarcoma in young people: background, prognostic factors and therapeutic questions. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005;27(4):207-211.

17. Varela-Duran J, Enzinger FM. Calcifying synovial sarcoma. Cancer. 1982;50(2):345-352.

18. Cagle LA, Mirra JM, Storm FK, Roe DJ, Eilber FR. Histologic features relating to prognosis in synovial sarcoma. Cancer. 1987;59(10):1810-1814.

19. Skytting B, Meis-Kindblom JM, Larsson O, et al. Synovial sarcoma – identification of favorable and unfavorable histologic types: a Scandinavian sarcoma group study of 104 cases. Acta Orthop Scand. 1999:70(6):543-554.

20. Murphey MD, Gibson MS, Jennings BT, Crespo-Rodríguez AM, Fanburg-Smith J, Gajewski DA. Imaging of synovial sarcoma with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2006;26(5):1543-1565.

Soft tissue sarcomas are rare mesenchymal tumors that comprise 1% of all malignancies. Synovial sarcoma accounts for 5% to 10% of adult soft tissue sarcomas and usually occurs in close association with joint capsules, tendon sheaths, and bursa in the extremities of young and middle-aged adults.1 Synovial sarcomas have been reported in other unusual sites, including the head and neck, thoracic and abdominal wall, retroperitoneum, bone, pleura, and visceral organs such as the lung, prostate, or kidney.2 Primary renal synovial sarcoma is an extremely rare tumor accounting for <2% of all malignant renal tumors.3 To the best of our knowledge, fewer than 50 cases of primary renal synovial sarcoma have been described in the English literature.4 It presents as a diagnostic dilemma because of the dearth of specific clinical and imaging findings and is often confused with benign and malignant tumors. The differential diagnosis includes angiomyolipoma, renal cell carcinoma with sarcomatoid differentiation, metastatic sarcoma, hemangiopericytoma, malignant solitary fibrous tumor, Wilms tumor, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. Hence, a combination of histomorphologic, immunohistochemical, cytogenetic, and molecular studies that show a unique chromosomal translocation t(X;18) (p11;q11) is imperative in the diagnosis of primary renal synovial sarcoma.4 In the present report, we present the case of a 38-year-old man who was diagnosed with primary renal synovial sarcoma.

Case presentation and summary

A 38-year-old man with a medical history of gastroesophageal reflux disease and Barrett’s esophagus presented to our hospital for the first time with persistent and progressive right-sided flank and abdominal pain that was aggravated after a minor trauma to the back. There was no associated hematuria or dysuria.

Of note is that he had experienced intermittent flank pain for 2 years before this transfer. He had initially been diagnosed at his local hospital close to his home by ultrasound with an angiomyolipoma of 2 × 3 cm arising from the upper pole of his right kidney, which remained stable on repeat sonograms. About 22 months after his initial presentation at his local hospital, the flank pain increased, and a computed-tomographic (CT) scan revealed a perinephric hematoma that was thought to originate from a ruptured angiomyolipoma. He subsequently underwent embolization, but his symptoms recurred soon after. He presented again to his local hospital where CT imaging revealed a significant increase in the size of the retroperitoneal mass, and findings were suggestive of a hematoma. Subsequent angiogram did not reveal active extravasation, so a biopsy was performed.

Before confirmatory pathologic evaluation could be completed, the patient presented to his local hospital again in excruciating pain. A CT scan of his abdomen and pelvis demonstrated a massive subacute on chronic hematoma in the right retroperitoneum measuring 22 × 19 × 18 cm, with calcifications originating from an upper pole right renal neoplasm. The right kidney was displaced antero-inferiorly, and the inferior vena cava was displaced anteriorly and to the left. The preliminary pathology returned with findings suggestive of sarcoma (Figures 1 and 2).

The patient was then transferred to our institution, where he was evaluated by medical and surgical oncology. A CT scan of the chest and magnetic-resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain did not reveal metastatic disease. He underwent exploratory laparotomy that involved the resection of a 22-cm retroperitoneal mass, right nephrectomy, right adrenalectomy, partial right hepatectomy, and a full thickness resection of the right postero-inferior diaphragm followed by mesh repair because of involvement by the tumor.

In its entirety, the specimen was a mass of 26 × 24 × 14 cm. It was sectioned to show extensively necrotic and hemorrhagic variegated white to tan-red parenchyma (Figure 3). Histology revealed a poorly differentiated malignant neoplasm composed of round cells with scant amphophilic cytoplasm arranged in solid, variably sized nests separated by prominent thin-walled branching vascular channels (Figure 4). The mitotic rate was high. It was determined to be a histologically ungraded sarcoma according to the French Federation of Comprehensive Cancer Centers system of grading soft tissue sarcomas; the margins were indeterminate. Immunohistochemistry was positive for EMA, TLE1, and negative for AE1/AE3, S100, STAT6, and Nkx2.2. Molecular pathology fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis demonstrated positivity for SS18 gene rearrangement (SS18-SSX1 fusion).

After recovering from surgery, the patient received adjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin and ifosfamide. It has been almost 16 months since we first saw this patient. He was started on doxorubicin 20 mg/m2 on days 1 to 4, ifosfamide 2,500 mg on days 1 to 4, and mesna 800 mg on days 1 to 4, for a total of 6 cycles. He did well for the first 5 months, after which he developed disease recurrence in the postoperative nephrectomy bed (a biopsy showed it to be recurrent synovial sarcoma) as well as pulmonary nodules, for which he was started on trabectedin 1.5 mg/m2 every 3 weeks. Two months later, a CT scan showed an increase in the size of his retroperitoneal mass, and the treatment was changed to pazopanib 400 mg daily orally, on which he remained at the time of publication.

Discussion

Synovial sarcoma is the fourth most common type of soft tissue sarcoma, accounting for 2.5% to 10.5% of all primary soft tissue malignancies worldwide. It occurs most frequently in adolescents and young adults, with most patients presenting between the ages of 15 and 40 years. Median age of presentation is 36 years. Despite the nomenclature, synovial sarcoma does not arise in intra-articular locations but typically occurs in proximity to joints in the extremities. Synovial sarcomas are less commonly described in other sites, including the head and neck, mediastinum, intraperitoneum, retroperitoneum, lung, pleura, and kidney.4,5 Renal synovial sarcoma was first described in a published article by Argani and colleagues in 2000.5

Adult renal mesenchymal tumors are classified into benign and malignant tumors on the basis of the histologic features and clinicobiologic behavior.6,7 The benign esenchymal renal tumors include angiomyolipoma, leiomyoma, hemangioma, lymphangioma, juxtaglomerular cell tumor, renomedullary interstitial cell tumor (medullary fibroma), lipoma, solitary fibrous tumor, and schwannoma. Malignant renal tumors of mesenchymal origin include leiomyosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, angiosarcoma, osteosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, solitary fibrous tumor, and synovial sarcoma.

Most of these tumor types cause the same nonspecific symptoms in patients – abdominal pain, flank pain, abdominal fullness, a palpable mass, and hematuria – although they can be clinically silent. The average duration of symptoms in synovial sarcoma is 2 to 4 years.8 The long duration of symptoms and initial slow growth of synovial sarcomas may give a false impression of a benign process.

A preoperative radiological diagnosis of primary renal synovial sarcoma may be suspected by analyzing the tumor’s growth patterns on CT scans.9 Renal synovial sarcomas often appear as large, well-defined soft tissue masses that can extend into the renal pelvis or into the perinephric region.9 A CT scan may identify soft tissue calcifications, especially subtle ones in areas where the tumor anatomy is complex. A CT scan may also reveal areas of hemorrhage, necrosis, or cyst formation within the tumor, and can easily confirm bone involvement. Intravenous contrast may help in differentiating the mass from adjacent muscle and neurovascular complex.9,10 On MRI, renal synovial sarcomas are often described as nonspecific heterogeneous masses, although they may also exhibit heterogeneous enhancement of hemorrhagic areas, calcifications, and air-fluid levels (known as “triple sign”) as well as septae. The triple sign may be identified as areas of low, intermediate, and high signal intensity, correlating with areas of hemorrhage, calcification, and air-fluid level.9,10 Signal intensity is about equal to that of skeletal muscle on T1-weighted MRI and higher than that of subcutaneous fat on T2-weighted MRI.

In the present case, the tumor was initially misdiagnosed as an angiomyolipoma, the most common benign tumor of the kidney. Angiomyolipomas are usually solid triphasic tumors arising from the renal cortex and are composed of 3 major elements: dysmorphic blood vessels, smooth muscle components, and adipose tissue. When angiomyolipomas are large enough, they are readily recognized by the identification of macroscopic fat within the tumor, either by CT scan or MRI.11 When they are small, they may be difficult to distinguish from a small cyst on CT because of volume averaging.

On pathology, synovial sarcoma has dual epithelial and mesenchymal differentiation. They are frequently multi-lobulated, and areas of necrosis, hemorrhage, and cyst formation are also common. There are 3 main histologic subtypes of synovial sarcoma: biphasic (20%-30%), monophasic (50%-60%), and poorly differentiated (15%-25%). Poorly differentiated synovial sarcomas are generally epithelioid in morphology, have high mitotic activity (usually 10-20 mitoses/10 high-power field; range is <5 for well differentiated, low-grade tumors), and can be confused with round cell tumors such as Ewing sarcoma. Poorly differentiated synovial sarcomas are high-grade tumors.

Immunohistochemical studies can confirm the pathological diagnosis. Synovial sarcomas usually stain positive for Bcl2, CD99/Mic2, CD56, Vim, and focally for EMA but negatively for desmin, actin, WT1, S-100, CD34, and CD31.5 Currently, the gold standard for diagnosis and hallmark for synovial sarcomas are the t (X;18) translocation and SYT-SSX gene fusion products (SYT-SSX1 in 67% and SYT-SSX2 in 33% of cases). These can be detected either by FISH or reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. This genetic alteration is identified in more than 90% of synovial sarcomas and is highly specific.

The role of SYT-SSX gene fusion in the pathogenesis of synovial sarcoma is an active area of investigation. The fusion of SYT with SSX translates into a fusion protein that binds to the transcription activator SMARCA4 that is involved in chromatin remodeling, thus displacing both the wildtype SYT and the tumor suppressor gene SMARCB1. The modified protein complex then binds at several super-enhancer loci, unlocking suppressed genes such as Sox2, which is known to be necessary for synovial sarcoma proliferation. Alterations in SMARCB1 are involved in several cancer types, implicating this event as a driver of these malignancies.12 This results in a global alteration in chromatin remodeling that needs to be better understood to design targeted therapies.

The clinical course of synovial sarcoma, regardless of the tissue of origin, is typically poor. Multiple clinical and pathologic factors, including tumor size, location, patient age, and presence of poorly differentiated areas, are thought to have prognostic significance. A tumor size of more than 5 cm at presentation has the greatest impact on prognosis, with studies showing 5-year survival rates of 64% for patients with tumors smaller than 5 cm and 26% for patients with masses greater than 5 cm.13,14 High-grade synovial sarcoma is favored in tumors that have cystic components, hemorrhage, and fluid levels and the triple sign.

Patients with tumors in the extremities have a more favorable prognosis than those with lesions in the head and neck area or axially, a feature that likely reflects better surgical control available for extremity lesions. Patient age of less than 15 to 20 years is also associated with a better long-term prognosis.15,16 Varela-Duran and Enzinger17 reported that the presence of extensive calcifications suggests improved long-term survival, with 5-year survival rates of 82% and decreased rates of local recurrence (32%) and metastatic disease (29%). The poorly differentiated subtype is associated with a worsened prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of 20% through 30%.18,19 Other pathologic factors associated with worsened prognosis include presence of rhabdoid cells, extensive tumor necrosis, high nuclear grade, p53 mutations, and high mitotic rate (>10 mitoses/10 high-power field). More recently, the gene fusion type SYT-SSX2 (more common in monophasic lesions) has been associated with an improved prognosis, compared with that for SYT-SSX1, and an 89% metastasis-free survival.20

Although there are no guidelines for the treatment of primary renal synovial sarcoma because of the limited number of cases reported, surgery is considered the first choice. Adjuvant chemotherapy with an anthracycline (doxorubicin or epirubicin) combined with ifosfamide has been the most frequently used regimen in published cases, especially in those in which patients have poor prognostic factors as mentioned above.

Overall, the 5-year survival rate ranges from 36% to 76%.14 The clinical course of synovial sarcoma is characterized by a high rate of local recurrence (30%-50%) and metastatic disease (41%). Most metastases occur within the first 2 to 5 years after treatment cessation. Metastases are present in 16% to 25% of patients at their initial presentation, with the most frequent metastatic site being the lung, followed by the lymph nodes (4%-18%) and bone (8%-11%).

Conclusion

Primary renal synovial sarcoma is extremely rare, and preoperative diagnosis is difficult in the absence of specific clinical or imaging findings. A high index of suspicion combined with pathologic, immunohistochemical, cytogenetic, and molecular studies is essential for accurate diagnosis and subsequent treatment planning. The differential diagnosis of renal synovial sarcoma can be extensive, and our experience with this patient illustrates the diagnostic dilemma associated with renal synovial sarcoma.

Soft tissue sarcomas are rare mesenchymal tumors that comprise 1% of all malignancies. Synovial sarcoma accounts for 5% to 10% of adult soft tissue sarcomas and usually occurs in close association with joint capsules, tendon sheaths, and bursa in the extremities of young and middle-aged adults.1 Synovial sarcomas have been reported in other unusual sites, including the head and neck, thoracic and abdominal wall, retroperitoneum, bone, pleura, and visceral organs such as the lung, prostate, or kidney.2 Primary renal synovial sarcoma is an extremely rare tumor accounting for <2% of all malignant renal tumors.3 To the best of our knowledge, fewer than 50 cases of primary renal synovial sarcoma have been described in the English literature.4 It presents as a diagnostic dilemma because of the dearth of specific clinical and imaging findings and is often confused with benign and malignant tumors. The differential diagnosis includes angiomyolipoma, renal cell carcinoma with sarcomatoid differentiation, metastatic sarcoma, hemangiopericytoma, malignant solitary fibrous tumor, Wilms tumor, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. Hence, a combination of histomorphologic, immunohistochemical, cytogenetic, and molecular studies that show a unique chromosomal translocation t(X;18) (p11;q11) is imperative in the diagnosis of primary renal synovial sarcoma.4 In the present report, we present the case of a 38-year-old man who was diagnosed with primary renal synovial sarcoma.

Case presentation and summary

A 38-year-old man with a medical history of gastroesophageal reflux disease and Barrett’s esophagus presented to our hospital for the first time with persistent and progressive right-sided flank and abdominal pain that was aggravated after a minor trauma to the back. There was no associated hematuria or dysuria.

Of note is that he had experienced intermittent flank pain for 2 years before this transfer. He had initially been diagnosed at his local hospital close to his home by ultrasound with an angiomyolipoma of 2 × 3 cm arising from the upper pole of his right kidney, which remained stable on repeat sonograms. About 22 months after his initial presentation at his local hospital, the flank pain increased, and a computed-tomographic (CT) scan revealed a perinephric hematoma that was thought to originate from a ruptured angiomyolipoma. He subsequently underwent embolization, but his symptoms recurred soon after. He presented again to his local hospital where CT imaging revealed a significant increase in the size of the retroperitoneal mass, and findings were suggestive of a hematoma. Subsequent angiogram did not reveal active extravasation, so a biopsy was performed.

Before confirmatory pathologic evaluation could be completed, the patient presented to his local hospital again in excruciating pain. A CT scan of his abdomen and pelvis demonstrated a massive subacute on chronic hematoma in the right retroperitoneum measuring 22 × 19 × 18 cm, with calcifications originating from an upper pole right renal neoplasm. The right kidney was displaced antero-inferiorly, and the inferior vena cava was displaced anteriorly and to the left. The preliminary pathology returned with findings suggestive of sarcoma (Figures 1 and 2).

The patient was then transferred to our institution, where he was evaluated by medical and surgical oncology. A CT scan of the chest and magnetic-resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain did not reveal metastatic disease. He underwent exploratory laparotomy that involved the resection of a 22-cm retroperitoneal mass, right nephrectomy, right adrenalectomy, partial right hepatectomy, and a full thickness resection of the right postero-inferior diaphragm followed by mesh repair because of involvement by the tumor.

In its entirety, the specimen was a mass of 26 × 24 × 14 cm. It was sectioned to show extensively necrotic and hemorrhagic variegated white to tan-red parenchyma (Figure 3). Histology revealed a poorly differentiated malignant neoplasm composed of round cells with scant amphophilic cytoplasm arranged in solid, variably sized nests separated by prominent thin-walled branching vascular channels (Figure 4). The mitotic rate was high. It was determined to be a histologically ungraded sarcoma according to the French Federation of Comprehensive Cancer Centers system of grading soft tissue sarcomas; the margins were indeterminate. Immunohistochemistry was positive for EMA, TLE1, and negative for AE1/AE3, S100, STAT6, and Nkx2.2. Molecular pathology fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis demonstrated positivity for SS18 gene rearrangement (SS18-SSX1 fusion).

After recovering from surgery, the patient received adjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin and ifosfamide. It has been almost 16 months since we first saw this patient. He was started on doxorubicin 20 mg/m2 on days 1 to 4, ifosfamide 2,500 mg on days 1 to 4, and mesna 800 mg on days 1 to 4, for a total of 6 cycles. He did well for the first 5 months, after which he developed disease recurrence in the postoperative nephrectomy bed (a biopsy showed it to be recurrent synovial sarcoma) as well as pulmonary nodules, for which he was started on trabectedin 1.5 mg/m2 every 3 weeks. Two months later, a CT scan showed an increase in the size of his retroperitoneal mass, and the treatment was changed to pazopanib 400 mg daily orally, on which he remained at the time of publication.

Discussion

Synovial sarcoma is the fourth most common type of soft tissue sarcoma, accounting for 2.5% to 10.5% of all primary soft tissue malignancies worldwide. It occurs most frequently in adolescents and young adults, with most patients presenting between the ages of 15 and 40 years. Median age of presentation is 36 years. Despite the nomenclature, synovial sarcoma does not arise in intra-articular locations but typically occurs in proximity to joints in the extremities. Synovial sarcomas are less commonly described in other sites, including the head and neck, mediastinum, intraperitoneum, retroperitoneum, lung, pleura, and kidney.4,5 Renal synovial sarcoma was first described in a published article by Argani and colleagues in 2000.5

Adult renal mesenchymal tumors are classified into benign and malignant tumors on the basis of the histologic features and clinicobiologic behavior.6,7 The benign esenchymal renal tumors include angiomyolipoma, leiomyoma, hemangioma, lymphangioma, juxtaglomerular cell tumor, renomedullary interstitial cell tumor (medullary fibroma), lipoma, solitary fibrous tumor, and schwannoma. Malignant renal tumors of mesenchymal origin include leiomyosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, angiosarcoma, osteosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, solitary fibrous tumor, and synovial sarcoma.

Most of these tumor types cause the same nonspecific symptoms in patients – abdominal pain, flank pain, abdominal fullness, a palpable mass, and hematuria – although they can be clinically silent. The average duration of symptoms in synovial sarcoma is 2 to 4 years.8 The long duration of symptoms and initial slow growth of synovial sarcomas may give a false impression of a benign process.

A preoperative radiological diagnosis of primary renal synovial sarcoma may be suspected by analyzing the tumor’s growth patterns on CT scans.9 Renal synovial sarcomas often appear as large, well-defined soft tissue masses that can extend into the renal pelvis or into the perinephric region.9 A CT scan may identify soft tissue calcifications, especially subtle ones in areas where the tumor anatomy is complex. A CT scan may also reveal areas of hemorrhage, necrosis, or cyst formation within the tumor, and can easily confirm bone involvement. Intravenous contrast may help in differentiating the mass from adjacent muscle and neurovascular complex.9,10 On MRI, renal synovial sarcomas are often described as nonspecific heterogeneous masses, although they may also exhibit heterogeneous enhancement of hemorrhagic areas, calcifications, and air-fluid levels (known as “triple sign”) as well as septae. The triple sign may be identified as areas of low, intermediate, and high signal intensity, correlating with areas of hemorrhage, calcification, and air-fluid level.9,10 Signal intensity is about equal to that of skeletal muscle on T1-weighted MRI and higher than that of subcutaneous fat on T2-weighted MRI.

In the present case, the tumor was initially misdiagnosed as an angiomyolipoma, the most common benign tumor of the kidney. Angiomyolipomas are usually solid triphasic tumors arising from the renal cortex and are composed of 3 major elements: dysmorphic blood vessels, smooth muscle components, and adipose tissue. When angiomyolipomas are large enough, they are readily recognized by the identification of macroscopic fat within the tumor, either by CT scan or MRI.11 When they are small, they may be difficult to distinguish from a small cyst on CT because of volume averaging.

On pathology, synovial sarcoma has dual epithelial and mesenchymal differentiation. They are frequently multi-lobulated, and areas of necrosis, hemorrhage, and cyst formation are also common. There are 3 main histologic subtypes of synovial sarcoma: biphasic (20%-30%), monophasic (50%-60%), and poorly differentiated (15%-25%). Poorly differentiated synovial sarcomas are generally epithelioid in morphology, have high mitotic activity (usually 10-20 mitoses/10 high-power field; range is <5 for well differentiated, low-grade tumors), and can be confused with round cell tumors such as Ewing sarcoma. Poorly differentiated synovial sarcomas are high-grade tumors.

Immunohistochemical studies can confirm the pathological diagnosis. Synovial sarcomas usually stain positive for Bcl2, CD99/Mic2, CD56, Vim, and focally for EMA but negatively for desmin, actin, WT1, S-100, CD34, and CD31.5 Currently, the gold standard for diagnosis and hallmark for synovial sarcomas are the t (X;18) translocation and SYT-SSX gene fusion products (SYT-SSX1 in 67% and SYT-SSX2 in 33% of cases). These can be detected either by FISH or reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. This genetic alteration is identified in more than 90% of synovial sarcomas and is highly specific.

The role of SYT-SSX gene fusion in the pathogenesis of synovial sarcoma is an active area of investigation. The fusion of SYT with SSX translates into a fusion protein that binds to the transcription activator SMARCA4 that is involved in chromatin remodeling, thus displacing both the wildtype SYT and the tumor suppressor gene SMARCB1. The modified protein complex then binds at several super-enhancer loci, unlocking suppressed genes such as Sox2, which is known to be necessary for synovial sarcoma proliferation. Alterations in SMARCB1 are involved in several cancer types, implicating this event as a driver of these malignancies.12 This results in a global alteration in chromatin remodeling that needs to be better understood to design targeted therapies.

The clinical course of synovial sarcoma, regardless of the tissue of origin, is typically poor. Multiple clinical and pathologic factors, including tumor size, location, patient age, and presence of poorly differentiated areas, are thought to have prognostic significance. A tumor size of more than 5 cm at presentation has the greatest impact on prognosis, with studies showing 5-year survival rates of 64% for patients with tumors smaller than 5 cm and 26% for patients with masses greater than 5 cm.13,14 High-grade synovial sarcoma is favored in tumors that have cystic components, hemorrhage, and fluid levels and the triple sign.

Patients with tumors in the extremities have a more favorable prognosis than those with lesions in the head and neck area or axially, a feature that likely reflects better surgical control available for extremity lesions. Patient age of less than 15 to 20 years is also associated with a better long-term prognosis.15,16 Varela-Duran and Enzinger17 reported that the presence of extensive calcifications suggests improved long-term survival, with 5-year survival rates of 82% and decreased rates of local recurrence (32%) and metastatic disease (29%). The poorly differentiated subtype is associated with a worsened prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of 20% through 30%.18,19 Other pathologic factors associated with worsened prognosis include presence of rhabdoid cells, extensive tumor necrosis, high nuclear grade, p53 mutations, and high mitotic rate (>10 mitoses/10 high-power field). More recently, the gene fusion type SYT-SSX2 (more common in monophasic lesions) has been associated with an improved prognosis, compared with that for SYT-SSX1, and an 89% metastasis-free survival.20

Although there are no guidelines for the treatment of primary renal synovial sarcoma because of the limited number of cases reported, surgery is considered the first choice. Adjuvant chemotherapy with an anthracycline (doxorubicin or epirubicin) combined with ifosfamide has been the most frequently used regimen in published cases, especially in those in which patients have poor prognostic factors as mentioned above.

Overall, the 5-year survival rate ranges from 36% to 76%.14 The clinical course of synovial sarcoma is characterized by a high rate of local recurrence (30%-50%) and metastatic disease (41%). Most metastases occur within the first 2 to 5 years after treatment cessation. Metastases are present in 16% to 25% of patients at their initial presentation, with the most frequent metastatic site being the lung, followed by the lymph nodes (4%-18%) and bone (8%-11%).

Conclusion

Primary renal synovial sarcoma is extremely rare, and preoperative diagnosis is difficult in the absence of specific clinical or imaging findings. A high index of suspicion combined with pathologic, immunohistochemical, cytogenetic, and molecular studies is essential for accurate diagnosis and subsequent treatment planning. The differential diagnosis of renal synovial sarcoma can be extensive, and our experience with this patient illustrates the diagnostic dilemma associated with renal synovial sarcoma.

1. Majumder A, Dey S, Khandakar B, Medda S, Chandra Paul P. Primary renal synovial sarcoma: a rare tumor with an atypical presentation. Arch Iran Med. 2014;17(10):726-728.

2. Fetsch JF, Meis JM. Synovial sarcoma of the abdominal wall. Cancer. 1993;72(2):469 477.

3. Wang Z, Zhong Z, Zhu L, et al. Primary synovial sarcoma of the kidney: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2015;10(6):3542-3544.

4. Abbas M, Dämmrich ME, Braubach P, et al. Synovial sarcoma of the kidney in a young patient with a review of the literature. Rare tumors. 2014;6(2):5393

5. Argani P, Faria PA, Epstein JI, et al. Primary renal synovial sarcoma: molecular and morphologic delineation of an entity previously included among embryonal sarcomas of the kidney. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24(8):1087-1096.

6. Eble JN, Sauter G, Epstein JI, Sesterhenn IA, eds. World Health Organization classification of tumours: pathology and genetics of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs. Lyon, France: IARC; 2004.

7. Tamboli P, Ro JY, Amin MB, Ligato S, Ayala AG. Benign tumors and tumor-like lesions of the adult kidney. Part II: benign mesenchymal and mixed neoplasms, and tumor-like lesions. Adv Anat Pathol. 2000;7(1):47-66.

8. Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Malignant soft tissue tumors of uncertain type. In: Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, eds. Enzinger and Weiss’s soft tissue tumors. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby, 2001; 1483-1565.

9. Lacovelli R, Altavilla A, Ciardi A, et al. Clinical and pathological features of primary renal synovial sarcoma: analysis of 64 cases from 11 years of medical literature. BJU Int. 2012;110(10):1449-1454.

10. Alhazzani AR, El-Sharkawy MS, Hassan H. Primary retroperitoneal synovial sarcoma in CT and MRI. Urol Ann. 2010;2(1):39-41.

11. Katabathina VS, Vikram R, Nagar AM, Tamboli P, Menias CO, Prasad SR. Mesenchymal neoplasms of the kidney in adults: imaging spectrum with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2010;30(6):1525-1540.

12. Sápi Z, Papp G, Szendrői M, et al. Epigenetic regulation of SMARCB1 by miR-206, -381 and -671- 5p is evident in a variety of SMARCB1 immunonegative soft tissue sarcomas, while miR-765 appears specific for epithelioid sarcoma. A miRNA study of 223 soft tissue sarcomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2016;55(10):786-802.

13. Ferrari A, Gronchi A, Casanova M, et al. Synovial sarcoma: a retrospective analysis of 271 patients of all ages treated at a single institution. Cancer. 2004;101(3):627-634.

14. Rangheard AS, Vanel D, Viala J, Schwaab G, Casiraghi O, Sigal R. Synovial sarcomas of the head and neck: CT and MR imaging findings of eight patients. Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22(5):851-857.

15. Oda Y, Hashimoto H, Tsuneyoshi M, Takeshita S. Survival in synovial sarcoma: a multivariate study of prognostic factors with special emphasis on the comparison between early death and long-term survival. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17(1):35-44.

16. Raney RB. Synovial sarcoma in young people: background, prognostic factors and therapeutic questions. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005;27(4):207-211.

17. Varela-Duran J, Enzinger FM. Calcifying synovial sarcoma. Cancer. 1982;50(2):345-352.

18. Cagle LA, Mirra JM, Storm FK, Roe DJ, Eilber FR. Histologic features relating to prognosis in synovial sarcoma. Cancer. 1987;59(10):1810-1814.

19. Skytting B, Meis-Kindblom JM, Larsson O, et al. Synovial sarcoma – identification of favorable and unfavorable histologic types: a Scandinavian sarcoma group study of 104 cases. Acta Orthop Scand. 1999:70(6):543-554.

20. Murphey MD, Gibson MS, Jennings BT, Crespo-Rodríguez AM, Fanburg-Smith J, Gajewski DA. Imaging of synovial sarcoma with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2006;26(5):1543-1565.

1. Majumder A, Dey S, Khandakar B, Medda S, Chandra Paul P. Primary renal synovial sarcoma: a rare tumor with an atypical presentation. Arch Iran Med. 2014;17(10):726-728.

2. Fetsch JF, Meis JM. Synovial sarcoma of the abdominal wall. Cancer. 1993;72(2):469 477.

3. Wang Z, Zhong Z, Zhu L, et al. Primary synovial sarcoma of the kidney: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2015;10(6):3542-3544.

4. Abbas M, Dämmrich ME, Braubach P, et al. Synovial sarcoma of the kidney in a young patient with a review of the literature. Rare tumors. 2014;6(2):5393

5. Argani P, Faria PA, Epstein JI, et al. Primary renal synovial sarcoma: molecular and morphologic delineation of an entity previously included among embryonal sarcomas of the kidney. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24(8):1087-1096.

6. Eble JN, Sauter G, Epstein JI, Sesterhenn IA, eds. World Health Organization classification of tumours: pathology and genetics of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs. Lyon, France: IARC; 2004.

7. Tamboli P, Ro JY, Amin MB, Ligato S, Ayala AG. Benign tumors and tumor-like lesions of the adult kidney. Part II: benign mesenchymal and mixed neoplasms, and tumor-like lesions. Adv Anat Pathol. 2000;7(1):47-66.

8. Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Malignant soft tissue tumors of uncertain type. In: Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, eds. Enzinger and Weiss’s soft tissue tumors. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby, 2001; 1483-1565.

9. Lacovelli R, Altavilla A, Ciardi A, et al. Clinical and pathological features of primary renal synovial sarcoma: analysis of 64 cases from 11 years of medical literature. BJU Int. 2012;110(10):1449-1454.

10. Alhazzani AR, El-Sharkawy MS, Hassan H. Primary retroperitoneal synovial sarcoma in CT and MRI. Urol Ann. 2010;2(1):39-41.

11. Katabathina VS, Vikram R, Nagar AM, Tamboli P, Menias CO, Prasad SR. Mesenchymal neoplasms of the kidney in adults: imaging spectrum with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2010;30(6):1525-1540.

12. Sápi Z, Papp G, Szendrői M, et al. Epigenetic regulation of SMARCB1 by miR-206, -381 and -671- 5p is evident in a variety of SMARCB1 immunonegative soft tissue sarcomas, while miR-765 appears specific for epithelioid sarcoma. A miRNA study of 223 soft tissue sarcomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2016;55(10):786-802.

13. Ferrari A, Gronchi A, Casanova M, et al. Synovial sarcoma: a retrospective analysis of 271 patients of all ages treated at a single institution. Cancer. 2004;101(3):627-634.

14. Rangheard AS, Vanel D, Viala J, Schwaab G, Casiraghi O, Sigal R. Synovial sarcomas of the head and neck: CT and MR imaging findings of eight patients. Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22(5):851-857.

15. Oda Y, Hashimoto H, Tsuneyoshi M, Takeshita S. Survival in synovial sarcoma: a multivariate study of prognostic factors with special emphasis on the comparison between early death and long-term survival. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17(1):35-44.

16. Raney RB. Synovial sarcoma in young people: background, prognostic factors and therapeutic questions. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005;27(4):207-211.

17. Varela-Duran J, Enzinger FM. Calcifying synovial sarcoma. Cancer. 1982;50(2):345-352.

18. Cagle LA, Mirra JM, Storm FK, Roe DJ, Eilber FR. Histologic features relating to prognosis in synovial sarcoma. Cancer. 1987;59(10):1810-1814.

19. Skytting B, Meis-Kindblom JM, Larsson O, et al. Synovial sarcoma – identification of favorable and unfavorable histologic types: a Scandinavian sarcoma group study of 104 cases. Acta Orthop Scand. 1999:70(6):543-554.

20. Murphey MD, Gibson MS, Jennings BT, Crespo-Rodríguez AM, Fanburg-Smith J, Gajewski DA. Imaging of synovial sarcoma with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2006;26(5):1543-1565.

TKIs and immunotherapy hold promise for alveolar soft part sarcoma

Alveolar soft part sarcoma (ASPS) has often proven to be resistant to conventional doxorubicin-based chemotherapy, but tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) may provide new treatment strategies for this rare type of sarcoma, according to a literature review.

A rare, translocation-driven sarcoma of the soft tissues, ASPS often affects young adults and is characterized by indolent behavior and early metastasis. Despite its resistance to chemotherapy, studies indicate that survival is often prolonged in patients with metastatic disease. The literature has shown 5-year survival rates at about 60%, and this percentage has remained fairly consistent for the past 3 decades.

Luca Paoluzzi, MD, of New York University, and Robert G. Maki, MD, PhD, of Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y., reviewed the literature from 1952 to March 2018, in order to gain a better understanding of ASPS and the opportunities “for the translation of such knowledge into clinical practice,” they wrote in JAMA.

From a therapeutic standpoint, ASPS is characterized by sensitivity to vascular endothelial growth factor receptor–predominant TKIs, compared with other soft tissue sarcomas (STS), and recent data have emphasized that it is responsive to new immunotherapy regimens including ICIs. Pazopanib is currently the only agent that has received regulatory approval for use in STS refractory to other treatments and it appears to have consistent activity in metastatic ASPS. Management of ASPS generally also involves surgical resection and/or systemic treatment for metastatic disease. Conventional agents such as anthracycline-based chemotherapy have demonstrated a poor response rate lower than 10%, and while a complete resection may be curative, metastases are common and can occur years after resection of the primary tumor.

Conversely, ICIs “represent a promising area of drug development in ASPS; the data to date are limited but encouraging,” wrote Dr. Paoluzzi and Dr. Maki.

They pointed to one study that included 50 patients with sarcoma with 14 different subtypes of STS who were enrolled in immunotherapy trials conducted at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. There were two pretreated patients with ASPS (two to four prior lines) in the cohort who received antiprogrammed death-ligand 1–based therapy, and achieved a partial response bordering on a complete response that lasted 8 and 12 months. An additional two patients achieved stable disease.

Another paper, presented at the 2017 Connective Tissue Oncology Society annual meeting, presented preliminary data from a phase 2 study that showed four of nine evaluable patients with ASPS treated with the TKI axitinib, combined with pembrolizumab, achieved a partial response. Three others had stable disease.

“Pathway-driven basket trials facilitate the enrollment of patients with such uncommon cancers and should provide valuable information regarding a second type of immune responsiveness to ICIs, one that is not a function of high tumor mutational burden,” the authors concluded.

No outside funding sources were reported. Dr. Maki reported receiving consultant fees from numerous sources and research support to New York University from Immune Design, Immunocore, Eli Lilly, Presage Biosciences, TRACON Pharmaceuticals, SARC, Regeneron, and Genentech. No other conflicts were reported.

SOURCE: doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4490.

Alveolar soft part sarcoma (ASPS) has often proven to be resistant to conventional doxorubicin-based chemotherapy, but tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) may provide new treatment strategies for this rare type of sarcoma, according to a literature review.

A rare, translocation-driven sarcoma of the soft tissues, ASPS often affects young adults and is characterized by indolent behavior and early metastasis. Despite its resistance to chemotherapy, studies indicate that survival is often prolonged in patients with metastatic disease. The literature has shown 5-year survival rates at about 60%, and this percentage has remained fairly consistent for the past 3 decades.

Luca Paoluzzi, MD, of New York University, and Robert G. Maki, MD, PhD, of Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y., reviewed the literature from 1952 to March 2018, in order to gain a better understanding of ASPS and the opportunities “for the translation of such knowledge into clinical practice,” they wrote in JAMA.

From a therapeutic standpoint, ASPS is characterized by sensitivity to vascular endothelial growth factor receptor–predominant TKIs, compared with other soft tissue sarcomas (STS), and recent data have emphasized that it is responsive to new immunotherapy regimens including ICIs. Pazopanib is currently the only agent that has received regulatory approval for use in STS refractory to other treatments and it appears to have consistent activity in metastatic ASPS. Management of ASPS generally also involves surgical resection and/or systemic treatment for metastatic disease. Conventional agents such as anthracycline-based chemotherapy have demonstrated a poor response rate lower than 10%, and while a complete resection may be curative, metastases are common and can occur years after resection of the primary tumor.

Conversely, ICIs “represent a promising area of drug development in ASPS; the data to date are limited but encouraging,” wrote Dr. Paoluzzi and Dr. Maki.

They pointed to one study that included 50 patients with sarcoma with 14 different subtypes of STS who were enrolled in immunotherapy trials conducted at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. There were two pretreated patients with ASPS (two to four prior lines) in the cohort who received antiprogrammed death-ligand 1–based therapy, and achieved a partial response bordering on a complete response that lasted 8 and 12 months. An additional two patients achieved stable disease.

Another paper, presented at the 2017 Connective Tissue Oncology Society annual meeting, presented preliminary data from a phase 2 study that showed four of nine evaluable patients with ASPS treated with the TKI axitinib, combined with pembrolizumab, achieved a partial response. Three others had stable disease.

“Pathway-driven basket trials facilitate the enrollment of patients with such uncommon cancers and should provide valuable information regarding a second type of immune responsiveness to ICIs, one that is not a function of high tumor mutational burden,” the authors concluded.

No outside funding sources were reported. Dr. Maki reported receiving consultant fees from numerous sources and research support to New York University from Immune Design, Immunocore, Eli Lilly, Presage Biosciences, TRACON Pharmaceuticals, SARC, Regeneron, and Genentech. No other conflicts were reported.

SOURCE: doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4490.

Alveolar soft part sarcoma (ASPS) has often proven to be resistant to conventional doxorubicin-based chemotherapy, but tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) may provide new treatment strategies for this rare type of sarcoma, according to a literature review.

A rare, translocation-driven sarcoma of the soft tissues, ASPS often affects young adults and is characterized by indolent behavior and early metastasis. Despite its resistance to chemotherapy, studies indicate that survival is often prolonged in patients with metastatic disease. The literature has shown 5-year survival rates at about 60%, and this percentage has remained fairly consistent for the past 3 decades.

Luca Paoluzzi, MD, of New York University, and Robert G. Maki, MD, PhD, of Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y., reviewed the literature from 1952 to March 2018, in order to gain a better understanding of ASPS and the opportunities “for the translation of such knowledge into clinical practice,” they wrote in JAMA.

From a therapeutic standpoint, ASPS is characterized by sensitivity to vascular endothelial growth factor receptor–predominant TKIs, compared with other soft tissue sarcomas (STS), and recent data have emphasized that it is responsive to new immunotherapy regimens including ICIs. Pazopanib is currently the only agent that has received regulatory approval for use in STS refractory to other treatments and it appears to have consistent activity in metastatic ASPS. Management of ASPS generally also involves surgical resection and/or systemic treatment for metastatic disease. Conventional agents such as anthracycline-based chemotherapy have demonstrated a poor response rate lower than 10%, and while a complete resection may be curative, metastases are common and can occur years after resection of the primary tumor.

Conversely, ICIs “represent a promising area of drug development in ASPS; the data to date are limited but encouraging,” wrote Dr. Paoluzzi and Dr. Maki.

They pointed to one study that included 50 patients with sarcoma with 14 different subtypes of STS who were enrolled in immunotherapy trials conducted at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. There were two pretreated patients with ASPS (two to four prior lines) in the cohort who received antiprogrammed death-ligand 1–based therapy, and achieved a partial response bordering on a complete response that lasted 8 and 12 months. An additional two patients achieved stable disease.

Another paper, presented at the 2017 Connective Tissue Oncology Society annual meeting, presented preliminary data from a phase 2 study that showed four of nine evaluable patients with ASPS treated with the TKI axitinib, combined with pembrolizumab, achieved a partial response. Three others had stable disease.

“Pathway-driven basket trials facilitate the enrollment of patients with such uncommon cancers and should provide valuable information regarding a second type of immune responsiveness to ICIs, one that is not a function of high tumor mutational burden,” the authors concluded.

No outside funding sources were reported. Dr. Maki reported receiving consultant fees from numerous sources and research support to New York University from Immune Design, Immunocore, Eli Lilly, Presage Biosciences, TRACON Pharmaceuticals, SARC, Regeneron, and Genentech. No other conflicts were reported.

SOURCE: doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4490.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Alveolar soft part sarcoma has often proven to be resistant to conventional doxorubicin-based chemotherapy, tyrosine kinase inhibitors and immune checkpoint inhibitors may provide new treatment strategies.

Major finding: In one study of sarcoma patients enrolled in immunotherapy trials, two pretreated patients with alveolar soft part sarcoma (two to four prior lines) who received antiprogrammed death-ligand 1–based therapy achieved partial responses, bordering on a complete response, that lasted 8 and 12 months.

Study details: A review of literature concerning treatment for alveolar soft part sarcoma.

Disclosures: No outside funding sources were reported. Dr. Maki reported receiving consultant fees from numerous sources and research support to New York University from Immune Design, Immunocore, Eli Lilly, Presage Biosciences, TRACON Pharmaceuticals, SARC, Regeneron, and Genentech. No other conflicts were reported.

Source:

Predicting treatment response in leiomyosarcoma, liposarcoma

Aberrations in oncogenic pathways and immune modulation influence treatment response in patients with metastatic leiomyosarcoma or liposarcoma, based on an analysis of whole-exome sequencing of tumor samples from patients in a completed phase 3 randomized trial comparing trabectedin and dacarbazine.

In that trial, trabectedin benefit was mostly seen in patients with leiomyosarcoma, as well as in patients with myxoid/round cell sarcomas, and less so in those with dedifferentiated and pleomorphic liposarcomas.

Gurpreet Kapoor, PhD, of LabConnect, Seattle, and colleagues examined aberrations in oncogenic pathways (DNA damage response, PI3K, MDM2-p53) and in immune modulation and then correlated the genomic aberrations with prospective data on clinical outcomes in the trial.

For the study, presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology in Chicago, archival tumor samples were collected from 456 of the 518 patients; 180 had uterine leiomyosarcomas, 149 had nonuterine leiomyosarcomas, 66 had dedifferentiated liposarcomas, 46 had myxoid liposarcomas, and 15 had pleomorphic liposarcomas.

Peripheral blood samples from a subset of 346 patients were also analyzed as matched normal to filter noise from nonpathogenic variants in the whole-exome sequencing.

Consistent with sarcoma data from The Cancer Genome Atlas, frequent homozygous gene deletions with relatively low mutational load were noted in these leiomyosarcoma and liposarcoma samples. TP53 and RB1 alterations were more frequent in leiomyosarcomas than in liposarcomas and were not associated with clinical outcomes. Analyses of 103 DNA damage-response genes found somatic alterations exceeded 20% across subtypes and correlated with improved progression-free survival in only uterine leiomyosarcomas (hazard ratio, 0.63; P = .03).

Genomic alterations in PI3K pathway genes were noted in 30% of myxoid liposarcomas and were associated with a worse rate of progression-free survival (HR, 3.0; P = .045).

A trend towards better overall survival was noted in dedifferentiated liposarcoma patients with MDM2 amplification as compared with normal MDM2 copy number.

Certain subtype-specific genomic aberrations in immune modulation pathways were associated with worse clinical outcomes in patients with uterine leiomyosarcoma or dedifferentiated liposarcoma. Alterations in immune suppressors were associated with improved clinical outcomes in nonuterine leiomyosarcomas and alterations in lipid metabolism were associated with improved clinical outcomes in dedifferentiated liposarcomas.

The invited discussant for the study, Mark Andrew Dickson, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, noted that “the real take-home here is that the TMBs (tumor mutation burdens) are relatively low across all of the L-type sarcomas.

“The pattern and prevalence of genomic aberrations that we’re seeing in this cohort of patients prospectively analyzed on a clinical trial are consistent with prior reports. ... including CDK4 and MDM2 in dedifferentiated liposarcoma, PI3-kinase in some myxoid/round cells, p53 in leiomyosarcoma and liposarcoma, and so on.”

Generally, tumor mutation burden is low in L-type sarcomas, and there are some intriguing associations with benefit to therapies, such as PI3-kinase pathway and potential resistance to trabectedin and high tumor mutation burden and potential sensitivity to trabectedin, that need to be explored and validated in another larger cohort, he said.

“I also am increasingly coming to terms with the fact that the tumors like leiomyosarcoma, which have low tumor mutation burden, and which so far have proven fairly immune to immunotherapy, based on all of the negative PD-1 data that we’ve seen, and that also have recurrent, relatively unactionable mutations, like p53 and Rb, remain very difficult to treat,” Dr. Dickson concluded.

SOURCE: Kapoor G et al. ASCO 2018, Abstract 11513.

Aberrations in oncogenic pathways and immune modulation influence treatment response in patients with metastatic leiomyosarcoma or liposarcoma, based on an analysis of whole-exome sequencing of tumor samples from patients in a completed phase 3 randomized trial comparing trabectedin and dacarbazine.

In that trial, trabectedin benefit was mostly seen in patients with leiomyosarcoma, as well as in patients with myxoid/round cell sarcomas, and less so in those with dedifferentiated and pleomorphic liposarcomas.

Gurpreet Kapoor, PhD, of LabConnect, Seattle, and colleagues examined aberrations in oncogenic pathways (DNA damage response, PI3K, MDM2-p53) and in immune modulation and then correlated the genomic aberrations with prospective data on clinical outcomes in the trial.

For the study, presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology in Chicago, archival tumor samples were collected from 456 of the 518 patients; 180 had uterine leiomyosarcomas, 149 had nonuterine leiomyosarcomas, 66 had dedifferentiated liposarcomas, 46 had myxoid liposarcomas, and 15 had pleomorphic liposarcomas.

Peripheral blood samples from a subset of 346 patients were also analyzed as matched normal to filter noise from nonpathogenic variants in the whole-exome sequencing.

Consistent with sarcoma data from The Cancer Genome Atlas, frequent homozygous gene deletions with relatively low mutational load were noted in these leiomyosarcoma and liposarcoma samples. TP53 and RB1 alterations were more frequent in leiomyosarcomas than in liposarcomas and were not associated with clinical outcomes. Analyses of 103 DNA damage-response genes found somatic alterations exceeded 20% across subtypes and correlated with improved progression-free survival in only uterine leiomyosarcomas (hazard ratio, 0.63; P = .03).

Genomic alterations in PI3K pathway genes were noted in 30% of myxoid liposarcomas and were associated with a worse rate of progression-free survival (HR, 3.0; P = .045).

A trend towards better overall survival was noted in dedifferentiated liposarcoma patients with MDM2 amplification as compared with normal MDM2 copy number.

Certain subtype-specific genomic aberrations in immune modulation pathways were associated with worse clinical outcomes in patients with uterine leiomyosarcoma or dedifferentiated liposarcoma. Alterations in immune suppressors were associated with improved clinical outcomes in nonuterine leiomyosarcomas and alterations in lipid metabolism were associated with improved clinical outcomes in dedifferentiated liposarcomas.

The invited discussant for the study, Mark Andrew Dickson, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, noted that “the real take-home here is that the TMBs (tumor mutation burdens) are relatively low across all of the L-type sarcomas.

“The pattern and prevalence of genomic aberrations that we’re seeing in this cohort of patients prospectively analyzed on a clinical trial are consistent with prior reports. ... including CDK4 and MDM2 in dedifferentiated liposarcoma, PI3-kinase in some myxoid/round cells, p53 in leiomyosarcoma and liposarcoma, and so on.”

Generally, tumor mutation burden is low in L-type sarcomas, and there are some intriguing associations with benefit to therapies, such as PI3-kinase pathway and potential resistance to trabectedin and high tumor mutation burden and potential sensitivity to trabectedin, that need to be explored and validated in another larger cohort, he said.

“I also am increasingly coming to terms with the fact that the tumors like leiomyosarcoma, which have low tumor mutation burden, and which so far have proven fairly immune to immunotherapy, based on all of the negative PD-1 data that we’ve seen, and that also have recurrent, relatively unactionable mutations, like p53 and Rb, remain very difficult to treat,” Dr. Dickson concluded.

SOURCE: Kapoor G et al. ASCO 2018, Abstract 11513.

Aberrations in oncogenic pathways and immune modulation influence treatment response in patients with metastatic leiomyosarcoma or liposarcoma, based on an analysis of whole-exome sequencing of tumor samples from patients in a completed phase 3 randomized trial comparing trabectedin and dacarbazine.

In that trial, trabectedin benefit was mostly seen in patients with leiomyosarcoma, as well as in patients with myxoid/round cell sarcomas, and less so in those with dedifferentiated and pleomorphic liposarcomas.

Gurpreet Kapoor, PhD, of LabConnect, Seattle, and colleagues examined aberrations in oncogenic pathways (DNA damage response, PI3K, MDM2-p53) and in immune modulation and then correlated the genomic aberrations with prospective data on clinical outcomes in the trial.

For the study, presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology in Chicago, archival tumor samples were collected from 456 of the 518 patients; 180 had uterine leiomyosarcomas, 149 had nonuterine leiomyosarcomas, 66 had dedifferentiated liposarcomas, 46 had myxoid liposarcomas, and 15 had pleomorphic liposarcomas.

Peripheral blood samples from a subset of 346 patients were also analyzed as matched normal to filter noise from nonpathogenic variants in the whole-exome sequencing.

Consistent with sarcoma data from The Cancer Genome Atlas, frequent homozygous gene deletions with relatively low mutational load were noted in these leiomyosarcoma and liposarcoma samples. TP53 and RB1 alterations were more frequent in leiomyosarcomas than in liposarcomas and were not associated with clinical outcomes. Analyses of 103 DNA damage-response genes found somatic alterations exceeded 20% across subtypes and correlated with improved progression-free survival in only uterine leiomyosarcomas (hazard ratio, 0.63; P = .03).

Genomic alterations in PI3K pathway genes were noted in 30% of myxoid liposarcomas and were associated with a worse rate of progression-free survival (HR, 3.0; P = .045).

A trend towards better overall survival was noted in dedifferentiated liposarcoma patients with MDM2 amplification as compared with normal MDM2 copy number.

Certain subtype-specific genomic aberrations in immune modulation pathways were associated with worse clinical outcomes in patients with uterine leiomyosarcoma or dedifferentiated liposarcoma. Alterations in immune suppressors were associated with improved clinical outcomes in nonuterine leiomyosarcomas and alterations in lipid metabolism were associated with improved clinical outcomes in dedifferentiated liposarcomas.

The invited discussant for the study, Mark Andrew Dickson, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, noted that “the real take-home here is that the TMBs (tumor mutation burdens) are relatively low across all of the L-type sarcomas.

“The pattern and prevalence of genomic aberrations that we’re seeing in this cohort of patients prospectively analyzed on a clinical trial are consistent with prior reports. ... including CDK4 and MDM2 in dedifferentiated liposarcoma, PI3-kinase in some myxoid/round cells, p53 in leiomyosarcoma and liposarcoma, and so on.”

Generally, tumor mutation burden is low in L-type sarcomas, and there are some intriguing associations with benefit to therapies, such as PI3-kinase pathway and potential resistance to trabectedin and high tumor mutation burden and potential sensitivity to trabectedin, that need to be explored and validated in another larger cohort, he said.

“I also am increasingly coming to terms with the fact that the tumors like leiomyosarcoma, which have low tumor mutation burden, and which so far have proven fairly immune to immunotherapy, based on all of the negative PD-1 data that we’ve seen, and that also have recurrent, relatively unactionable mutations, like p53 and Rb, remain very difficult to treat,” Dr. Dickson concluded.

SOURCE: Kapoor G et al. ASCO 2018, Abstract 11513.

REPORTING FROM ASCO 2018

Key clinical point: Aberrations in oncogenic pathways and immune modulation influence treatment response in patients with metastatic leiomyosarcoma or liposarcoma.

Major finding: Genomic alterations in PI3K pathway genes were noted in 30% of myxoid liposarcomas and were associated with a worse rate of progression-free survival (HR, 3.0; P = .045).

Study details: Archival tumor samples were collected from 456 of the 518 patients; 180 had uterine leiomyosarcomas, 149 had nonuterine leiomyosarcomas, 66 had dedifferentiated liposarcomas, 46 had myxoid liposarcomas, and 15 had pleomorphic liposarcomas in the completed phase 3 randomized trial comparing trabectedin and dacarbazine.

Disclosures: Dr. Kapoor is employed by LabConnect, Seattle. Research funding was supplied by Janssen Research & Development.

Source: Kapoor G et al. ASCO 2018, Abstract 11513.

FDA lifts partial hold on tazemetostat trials

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has lifted the partial clinical hold on trials of tazemetostat, an EZH2 inhibitor being developed to treat solid tumors and lymphomas, according to a press release from the drug’s developer Epizyme.

The patient had been on study for approximately 15 months and had achieved a confirmed partial response. The patient has since discontinued tazemetostat and responded to treatment for T-LBL.

“This remains the only case of T-LBL we’ve seen in more than 750 patients treated with tazemetostat,” Robert Bazemore, president and chief executive officer of Epizyme, said in a webcast on Sept. 24.