User login

Are You Delivering on the Promise of Higher Quality?

One hospitalist-led pilot project produced a 61% decrease in heart failure readmission rates. Another resulted in a 33% drop in all-cause readmissions. The numbers might be impressive, but what do they really say about how hospitalists have influenced healthcare quality?

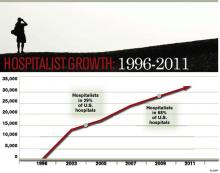

When HM emerged 15 years ago, advocates pitched the fledgling physician specialty as a model of efficient inpatient care, and subsequent findings that the concept led to reductions in length of stay encouraged more hospitals to bolster their staff with the newcomers. With a rising emphasis on quality and patient safety over the past decade, and the new era of pay-for-performance, the hospitalist model of care has expanded to embrace improved quality of care as a chief selling point.

Measuring quality is no easy task, however, and researchers still debate the relative merits of metrics like 30-day readmission rates and inpatient mortality. "Without question, quality measurement is an imperfect science, and all measures will contain some level of imprecision and bias," concluded a recent commentary in Health Affairs.1

Against that backdrop, relatively few studies have looked broadly at the contributions of hospital medicine. Most interventions have been individually tailored to a hospital or instituted at only a few sites, precluding large-scale, head-to-head comparisons.

And so the question remains: Has hospital medicine lived up to its promise on quality?

The Evidence

In one of the few national surveys of HM’s impact on patient care, a yearlong comparison of more than 3,600 hospitals found that the roughly 40% that employed hospitalists scored better on multiple Hospital Quality Alliance indicators. The 2009 Archives of Internal Medicine study suggested that hospitals with hospitalists outperformed their counterparts in quality metrics for acute myocardial infarction, pneumonia, overall disease treatment and diagnosis, and counseling and prevention. Congestive heart failure was the only category of the five reviewed that lacked a statistically significant difference.2

A separate editorial, however, argued that the study’s data were not persuasive enough to support the conclusion that hospitalists bring a higher quality of care to the table.3 And even less can be said about the national impact of HM on newly elevated metrics, such as readmission rates. The obligation to gather evidence, in fact, is largely falling upon hospitalists themselves, and the multitude of research abstracts from SHM’s annual meeting in May suggests that plenty of physician scientists are taking the responsibility seriously. Among the presentations, a study led by David Boyte, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Duke University and a hospitalist at Durham Regional Hospital, found that a multidisciplinary approach greatly improved one hospital unit’s 30-day readmission rates for heart failure patients. After a three-month pilot in the cardiac nursing unit, readmission rates fell to 10.7% from 27.6%.4

Although the multidisciplinary effort has included doctors, nurses, nutritionists, pharmacists, unit managers, and other personnel, Dr. Boyte says the involvement of hospitalists has been key to the project’s success. "We feel like we were the main participants who could see the whole picture from a patient-centered perspective," he says. "We were the glue; we were the center node of all the healthcare providers." Based on that dramatic improvement, Dr. Boyte says, the same interventional protocol has been rolled out in three other medical surgical units, and the hospital is using a similar approach to address AMI readmission rates.

SHM’s Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions; www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost )—by far the largest study of how HM is impacting readmission rates—has amassed data from more than 20 hospitals, with more expected from a growing roster of participants. So far, however, the project has only released data from six pilot sites describing the six-month periods before and after the project’s start. Among those sites, initial results suggest that readmission rates fell by an average of more than 20%, to 11.2% from 14.2%.5

Though the early numbers are encouraging, experts say rates from a larger group of participants at the one-year mark will be more telling, as will direct comparisons between BOOST units and nonparticipating counterparts at the same hospitals. Principal investigator Mark Williams, MD, FHM, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, says researchers still need to clean up that data before they’re ready to share it publicly.

In the meantime, some individual BOOST case studies are suggesting that hospitalist-led changes could pay big dividends. To help create cohesiveness and a sense of ownership within its HM program, St. Mary’s Health Center in St. Louis started a 20-bed hospitalist unit in 2008. Philip Vaidyan, MD, FACP, head of the hospitalist program and practice group leader for IPC: The Hospitalist Company at St. Mary’s, says one unit, 3 West, has since functioned as a lab for testing new ideas that are then introduced hospitalwide.

One early change was to bring all of the unit’s care providers together, from doctors and nurses to the unit-based case manager and social worker, for 9 a.m. handoff meetings. "We have this collective brain to find unique solutions," Dr. Vaidyan says. After seeing positive trends on length of stay, 30-day readmission rates, and patient satisfaction scores, St. Mary’s upgraded to a 32-bed hospitalist unit in early 2009. That same year, the 525-bed community teaching hospital was accepted into the BOOST program.

The hospitalist unit’s improved quality scores continued under BOOST, leading to a 33% reduction in readmission rates from 2008 to 2010 (to 10.5% from 15.7%). Rates for a nonhospitalist unit, by contrast, hovered around 17%. "For reducing readmissions, people may think that you have to have a higher length of stay," Dr. Vaidyan says. But the unit trended toward a lower length of stay, in addition to its reduced 30-day readmissions and improved patient satisfaction scores.

Flush with success, the 10 physicians and four nurse practitioners in the hospitalist program have since begun spreading their best practices to the rest of the hospital units. "Hospitalists are in the best ‘sweet spot,’ " Dr. Vaidyan says, "partnering with all of the disciplines, bringing them together, and keeping everybody on the same page."

Ironically, pinpointing the contribution of hospitalists is harder when their changes produce an ecological effect throughout an entire institution, says Siddhartha Singh, MD, MS, associate chief medical officer of Medical College Physicians, the adult practice for Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee. Even so, he stresses that the impact of the two dozen hospitalists at Medical College Physicians has been felt.

"Coinciding with and following the introduction of our hospitalist program in 2004, we have noticed dramatic decreases in our length of stay throughout medicine services," he says. The same has held true for inpatient mortality. "And that, we feel, is attributable to the standardization of processes introduced by the hospitalist group." Multidisciplinary rounds; whiteboards in patient rooms; and standardized admission orders, prophylactic treatments, and discharge processes—"all of this would’ve been impossible, absolutely impossible, without the hospitalist," he says.

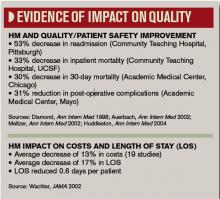

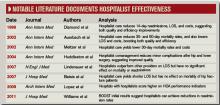

Over the past decade, Dr. Singh’s assessment has been echoed by several studies suggesting that individual hospitalist programs have brought significant improvements in quality measures, such as complication rates and inpatient mortality. In 2002, for example, Andrew Auerbach, MD, MPH, at the University of California San Francisco Medical Center, led a study that compared HM care with that of community physicians in a community-based teaching hospital. Patients cared for by hospitalists, the study found, had a lower risk of death during the hospitalization, as well as at 30 days and 60 days after discharge.6

A separate report by David Meltzer, MD, PhD, and colleagues at the University of Chicago found that an HM program in an academic general medicine service led to a 30% reduction in 30-day mortality rates during its second year of operation.7 And a 2004 study led by Jeanne Huddleston, MD, at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine in Rochester, Minn., found that a hospitalist-orthopedic co-management model (versus care by orthopedic surgeons with medical consultation) led to more patients being discharged with no complications after elective hip or knee surgery.8 Hospitalist co-management also reduced the rate of minor complications, but had no effect on actual length of stay or cost.

A subsequent study by the same group, however, documented improved efficiency of care through the HM model, but no effect on the mortality of hip fracture patients up to one year after discharge.9 Multiple studies of hospitalist programs, in fact, have seen increased efficiency but little or no impact on inpatient mortality, leading researchers to broadly conclude that such programs can decrease resource use without compromising quality.

In 2007, a retrospective study of nearly 77,000 patients admitted to 45 hospitals with one of seven common diagnoses compared the care delivered by hospitalists, general internists, and family physicians.10 Although the study authors found that hospitalist care yielded a small drop in length of stay, they saw no difference in the inpatient mortality rates or 14-day readmission rates. More recently, mortality has become ensnared in controversy over its reliability as an accurate indicator of quality.

-Shai Gavi, DO, MPH, chief, section of hospital medicine, assistant professor, Stony Brook University School of Medicine, Brookhaven, N.Y.

Half of the Equation

Despite a lack of ideal metrics, another promising sign for HM might be the model’s exportability. Lee Kheng Hock, MMed, senior consultant and head of the Department of Family Medicine and Continuing Care at Singapore General Hospital, says the 1,600-bed hospital began experimenting with the hospitalist model when officials realized the existing care system wasn’t sustainable. Amid an aging population and increasingly complex and fragmented care, Hock views the hospitalist movement as a natural evolution of the healthcare system to meet the needs of a changing environment.

In a recent study, Hock and his colleagues used the hospital’s administrative database to examine the resource use and outcomes of patients cared for in 2008 by family medicine hospitalists or by specialists.11 The comparison, based on several standard metrics, found no significant improvements in quality, with similar inpatient mortality rates and 30-day, all-cause, unscheduled readmission rates regardless of the care delivery method. The study, though, revealed a significantly shorter hospital stay (4.4 days vs. 5.3 days) and lower costs per patient for those cared for by hospitalists ($2,250 vs. $2,500).11

Hock points out that, like his study, most analyses of hospitalist programs have shown an improvement in length of stay and cost of care without any increase in mortality and morbidity. If value equals quality divided by cost, he says, it stands to reason that quality must increase as overall value remains the same but costs decrease.

"The main difference is that the patients received undivided attention from a well-rounded generalist physician who is focused on providing holistic general medical care," Hock says, adding that "it is really a no-brainer that the outcome would be different."

Patients Rule

Other measures like the effectiveness of communication and seamlessness of handoffs often are assessed through their impacts on patient outcomes. But Sunil Kripalani, MD, MSc, SFHM, chief of the section of hospital medicine and an associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., says communication is now a primary focal point in Medicare’s new hospital value-based purchasing program (VBP). Within VBP’s Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) component, worth 30% of a hospital’s sum score, four of the 10 survey-based measures deal directly with communication. Patients’ overall rating and recommendation of hospitals likely will reflect their satisfaction with communication as well. Dr. Kripalani says it’s inevitable that hospitals—and hospitalists—will pay more attention to communication ratings as patients become judges of quality.

The expertise of hospitalists in handling challenging patients also leads to improved quality over time, says Shai Gavi, DO, MPH, chief of the section of hospital medicine and assistant professor of clinical medicine at Stony Brook University School of Medicine in Brookhaven, N.Y. Hospitalists, he says, excel in handling such high-stakes medical issues as gastrointestinal bleeding, pancreatitis, sepsis, and pain management that can quickly impact patient outcomes if not addressed properly and proficiently. "I think there’s significant value to having people who do this on a pretty frequent basis," he says.

And because of their broad day-to-day interactions, Dr. Gavi says, hospitalists are natural choices for committees focused on improving quality. "When we sit on committees, people often look to us for answers and directions because they know we’re on the front lines and we’ve interfaced with all of the services in the hospital," he says. "You have a good view of the whole hospital operation from A to Z, and I think that’s pretty unique to hospitalists."

The Verdict

In a recent issue brief by Lisa Sprague, principal policy analyst at the National Health Policy Forum, she asserts, "Hospitalists have the undeniable advantage of being there when a crisis occurs, when a patient is ready for discharge, and so on."12

So is "being there" the defining concept of hospital medicine, as she subsequently suggests?

Based on both scientific and anecdotal evidence, the contribution of hospitalists to healthcare quality might be better summarized as "being involved." Whether as innovators, navigators, physician champions, the "sweet spot" of interdepartmental partnerships, the "glue" of multidisciplinary teams, or the nuclei of performance committees, hospitalists are increasingly described as being in the middle of efforts to improve quality. On this basis, the discipline appears to be living up to expectations, though experts say more research is needed to better assess the impacts of HM on quality.

Dr. Vaidyan says hospitalists are particularly well positioned to understand what constitutes ideal care from the perspective of patients. "They want to be treated well: That’s patient satisfaction," he says. "They want to have their chief complaint—why they came to the hospital—properly addressed, so you need a coordinated care team. They want to go home early and don’t want come back: That’s low length of stay and a reduction in 30-day readmissions. And they don’t want any hospital-acquired complications."

Treating patients better, then, should be reflected by improved quality, even if the participation of hospitalists cannot be precisely quantified. "Being involved is something that may be difficult to measure," Dr. Gavi says, "but nonetheless, it has an important impact." TH

Bryn Nelson is a medical writer based in Seattle.

References

- Pronovost PJ, Lilford R. Analysis & commentary: A roadmap for improving the performance of performance measures. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(4):569-73.

- López L, Hicks LS, Cohen AP, McKean S, Weissman JS. Hospitalists and the quality of care in hospitals. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(15):1389-1394.

- Centor RM, Taylor BB. Do hospitalists improve quality? Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(15):1351-1352.

- Boyte D, Verma L, Wightman M. A multidisciplinary approach to reducing heart failure readmissions. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(4)Supp 2:S14.

- Williams MV, Hansen L, Greenwald J, Howell E, et al. BOOST: impact of a quality improvement project to reduce rehospitalizations. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(4) Supp 2:S88. BOOST: impact of a quality improvement project to reduce rehospitalizations.

- Auerbach AD, Wachter RM, Katz P, Showstack J, Baron RB, Goldman L. Implementation of a voluntary hospitalist service at a community teaching hospital: improved clinical efficiency and patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):859-865.

- Meltzer D, Manning WG, Morrison J, et al. Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(1):866-874.

- Huddleston JM, Hall K, Naessens JM, et al. Medical and surgical comanagement after elective hip and knee arthroplasty. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(1):28-38.

- Batsis JA, Phy MP, Melton LJ, et al. Effects of a hospitalist care model on mortality of elderly patients with hip fractures. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(4): 219–225.

- Lindenauer PK, Rothberg MB, Pekow PS, et al. Outcomes of care by hospitalists, general internists, and family physicians. N Eng J Med. 2007;357:2589-2600.

- Hock Lee K, Yang Y, Soong Yang K, Chi Ong B, Seong Ng H. Bringing generalists into the hospital: outcomes of a family medicine hospitalist model in Singapore. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(3):115-121.

- Sprague L. The hospitalist: better value in inpatient care? National Health Policy Forum website. Available at: www.nhpf.org/library/issue-briefs/IB842_Hospitalist_03-30-11.pdf. Accessed June 28, 2011.

One hospitalist-led pilot project produced a 61% decrease in heart failure readmission rates. Another resulted in a 33% drop in all-cause readmissions. The numbers might be impressive, but what do they really say about how hospitalists have influenced healthcare quality?

When HM emerged 15 years ago, advocates pitched the fledgling physician specialty as a model of efficient inpatient care, and subsequent findings that the concept led to reductions in length of stay encouraged more hospitals to bolster their staff with the newcomers. With a rising emphasis on quality and patient safety over the past decade, and the new era of pay-for-performance, the hospitalist model of care has expanded to embrace improved quality of care as a chief selling point.

Measuring quality is no easy task, however, and researchers still debate the relative merits of metrics like 30-day readmission rates and inpatient mortality. "Without question, quality measurement is an imperfect science, and all measures will contain some level of imprecision and bias," concluded a recent commentary in Health Affairs.1

Against that backdrop, relatively few studies have looked broadly at the contributions of hospital medicine. Most interventions have been individually tailored to a hospital or instituted at only a few sites, precluding large-scale, head-to-head comparisons.

And so the question remains: Has hospital medicine lived up to its promise on quality?

The Evidence

In one of the few national surveys of HM’s impact on patient care, a yearlong comparison of more than 3,600 hospitals found that the roughly 40% that employed hospitalists scored better on multiple Hospital Quality Alliance indicators. The 2009 Archives of Internal Medicine study suggested that hospitals with hospitalists outperformed their counterparts in quality metrics for acute myocardial infarction, pneumonia, overall disease treatment and diagnosis, and counseling and prevention. Congestive heart failure was the only category of the five reviewed that lacked a statistically significant difference.2

A separate editorial, however, argued that the study’s data were not persuasive enough to support the conclusion that hospitalists bring a higher quality of care to the table.3 And even less can be said about the national impact of HM on newly elevated metrics, such as readmission rates. The obligation to gather evidence, in fact, is largely falling upon hospitalists themselves, and the multitude of research abstracts from SHM’s annual meeting in May suggests that plenty of physician scientists are taking the responsibility seriously. Among the presentations, a study led by David Boyte, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Duke University and a hospitalist at Durham Regional Hospital, found that a multidisciplinary approach greatly improved one hospital unit’s 30-day readmission rates for heart failure patients. After a three-month pilot in the cardiac nursing unit, readmission rates fell to 10.7% from 27.6%.4

Although the multidisciplinary effort has included doctors, nurses, nutritionists, pharmacists, unit managers, and other personnel, Dr. Boyte says the involvement of hospitalists has been key to the project’s success. "We feel like we were the main participants who could see the whole picture from a patient-centered perspective," he says. "We were the glue; we were the center node of all the healthcare providers." Based on that dramatic improvement, Dr. Boyte says, the same interventional protocol has been rolled out in three other medical surgical units, and the hospital is using a similar approach to address AMI readmission rates.

SHM’s Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions; www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost )—by far the largest study of how HM is impacting readmission rates—has amassed data from more than 20 hospitals, with more expected from a growing roster of participants. So far, however, the project has only released data from six pilot sites describing the six-month periods before and after the project’s start. Among those sites, initial results suggest that readmission rates fell by an average of more than 20%, to 11.2% from 14.2%.5

Though the early numbers are encouraging, experts say rates from a larger group of participants at the one-year mark will be more telling, as will direct comparisons between BOOST units and nonparticipating counterparts at the same hospitals. Principal investigator Mark Williams, MD, FHM, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, says researchers still need to clean up that data before they’re ready to share it publicly.

In the meantime, some individual BOOST case studies are suggesting that hospitalist-led changes could pay big dividends. To help create cohesiveness and a sense of ownership within its HM program, St. Mary’s Health Center in St. Louis started a 20-bed hospitalist unit in 2008. Philip Vaidyan, MD, FACP, head of the hospitalist program and practice group leader for IPC: The Hospitalist Company at St. Mary’s, says one unit, 3 West, has since functioned as a lab for testing new ideas that are then introduced hospitalwide.

One early change was to bring all of the unit’s care providers together, from doctors and nurses to the unit-based case manager and social worker, for 9 a.m. handoff meetings. "We have this collective brain to find unique solutions," Dr. Vaidyan says. After seeing positive trends on length of stay, 30-day readmission rates, and patient satisfaction scores, St. Mary’s upgraded to a 32-bed hospitalist unit in early 2009. That same year, the 525-bed community teaching hospital was accepted into the BOOST program.

The hospitalist unit’s improved quality scores continued under BOOST, leading to a 33% reduction in readmission rates from 2008 to 2010 (to 10.5% from 15.7%). Rates for a nonhospitalist unit, by contrast, hovered around 17%. "For reducing readmissions, people may think that you have to have a higher length of stay," Dr. Vaidyan says. But the unit trended toward a lower length of stay, in addition to its reduced 30-day readmissions and improved patient satisfaction scores.

Flush with success, the 10 physicians and four nurse practitioners in the hospitalist program have since begun spreading their best practices to the rest of the hospital units. "Hospitalists are in the best ‘sweet spot,’ " Dr. Vaidyan says, "partnering with all of the disciplines, bringing them together, and keeping everybody on the same page."

Ironically, pinpointing the contribution of hospitalists is harder when their changes produce an ecological effect throughout an entire institution, says Siddhartha Singh, MD, MS, associate chief medical officer of Medical College Physicians, the adult practice for Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee. Even so, he stresses that the impact of the two dozen hospitalists at Medical College Physicians has been felt.

"Coinciding with and following the introduction of our hospitalist program in 2004, we have noticed dramatic decreases in our length of stay throughout medicine services," he says. The same has held true for inpatient mortality. "And that, we feel, is attributable to the standardization of processes introduced by the hospitalist group." Multidisciplinary rounds; whiteboards in patient rooms; and standardized admission orders, prophylactic treatments, and discharge processes—"all of this would’ve been impossible, absolutely impossible, without the hospitalist," he says.

Over the past decade, Dr. Singh’s assessment has been echoed by several studies suggesting that individual hospitalist programs have brought significant improvements in quality measures, such as complication rates and inpatient mortality. In 2002, for example, Andrew Auerbach, MD, MPH, at the University of California San Francisco Medical Center, led a study that compared HM care with that of community physicians in a community-based teaching hospital. Patients cared for by hospitalists, the study found, had a lower risk of death during the hospitalization, as well as at 30 days and 60 days after discharge.6

A separate report by David Meltzer, MD, PhD, and colleagues at the University of Chicago found that an HM program in an academic general medicine service led to a 30% reduction in 30-day mortality rates during its second year of operation.7 And a 2004 study led by Jeanne Huddleston, MD, at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine in Rochester, Minn., found that a hospitalist-orthopedic co-management model (versus care by orthopedic surgeons with medical consultation) led to more patients being discharged with no complications after elective hip or knee surgery.8 Hospitalist co-management also reduced the rate of minor complications, but had no effect on actual length of stay or cost.

A subsequent study by the same group, however, documented improved efficiency of care through the HM model, but no effect on the mortality of hip fracture patients up to one year after discharge.9 Multiple studies of hospitalist programs, in fact, have seen increased efficiency but little or no impact on inpatient mortality, leading researchers to broadly conclude that such programs can decrease resource use without compromising quality.

In 2007, a retrospective study of nearly 77,000 patients admitted to 45 hospitals with one of seven common diagnoses compared the care delivered by hospitalists, general internists, and family physicians.10 Although the study authors found that hospitalist care yielded a small drop in length of stay, they saw no difference in the inpatient mortality rates or 14-day readmission rates. More recently, mortality has become ensnared in controversy over its reliability as an accurate indicator of quality.

-Shai Gavi, DO, MPH, chief, section of hospital medicine, assistant professor, Stony Brook University School of Medicine, Brookhaven, N.Y.

Half of the Equation

Despite a lack of ideal metrics, another promising sign for HM might be the model’s exportability. Lee Kheng Hock, MMed, senior consultant and head of the Department of Family Medicine and Continuing Care at Singapore General Hospital, says the 1,600-bed hospital began experimenting with the hospitalist model when officials realized the existing care system wasn’t sustainable. Amid an aging population and increasingly complex and fragmented care, Hock views the hospitalist movement as a natural evolution of the healthcare system to meet the needs of a changing environment.

In a recent study, Hock and his colleagues used the hospital’s administrative database to examine the resource use and outcomes of patients cared for in 2008 by family medicine hospitalists or by specialists.11 The comparison, based on several standard metrics, found no significant improvements in quality, with similar inpatient mortality rates and 30-day, all-cause, unscheduled readmission rates regardless of the care delivery method. The study, though, revealed a significantly shorter hospital stay (4.4 days vs. 5.3 days) and lower costs per patient for those cared for by hospitalists ($2,250 vs. $2,500).11

Hock points out that, like his study, most analyses of hospitalist programs have shown an improvement in length of stay and cost of care without any increase in mortality and morbidity. If value equals quality divided by cost, he says, it stands to reason that quality must increase as overall value remains the same but costs decrease.

"The main difference is that the patients received undivided attention from a well-rounded generalist physician who is focused on providing holistic general medical care," Hock says, adding that "it is really a no-brainer that the outcome would be different."

Patients Rule

Other measures like the effectiveness of communication and seamlessness of handoffs often are assessed through their impacts on patient outcomes. But Sunil Kripalani, MD, MSc, SFHM, chief of the section of hospital medicine and an associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., says communication is now a primary focal point in Medicare’s new hospital value-based purchasing program (VBP). Within VBP’s Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) component, worth 30% of a hospital’s sum score, four of the 10 survey-based measures deal directly with communication. Patients’ overall rating and recommendation of hospitals likely will reflect their satisfaction with communication as well. Dr. Kripalani says it’s inevitable that hospitals—and hospitalists—will pay more attention to communication ratings as patients become judges of quality.

The expertise of hospitalists in handling challenging patients also leads to improved quality over time, says Shai Gavi, DO, MPH, chief of the section of hospital medicine and assistant professor of clinical medicine at Stony Brook University School of Medicine in Brookhaven, N.Y. Hospitalists, he says, excel in handling such high-stakes medical issues as gastrointestinal bleeding, pancreatitis, sepsis, and pain management that can quickly impact patient outcomes if not addressed properly and proficiently. "I think there’s significant value to having people who do this on a pretty frequent basis," he says.

And because of their broad day-to-day interactions, Dr. Gavi says, hospitalists are natural choices for committees focused on improving quality. "When we sit on committees, people often look to us for answers and directions because they know we’re on the front lines and we’ve interfaced with all of the services in the hospital," he says. "You have a good view of the whole hospital operation from A to Z, and I think that’s pretty unique to hospitalists."

The Verdict

In a recent issue brief by Lisa Sprague, principal policy analyst at the National Health Policy Forum, she asserts, "Hospitalists have the undeniable advantage of being there when a crisis occurs, when a patient is ready for discharge, and so on."12

So is "being there" the defining concept of hospital medicine, as she subsequently suggests?

Based on both scientific and anecdotal evidence, the contribution of hospitalists to healthcare quality might be better summarized as "being involved." Whether as innovators, navigators, physician champions, the "sweet spot" of interdepartmental partnerships, the "glue" of multidisciplinary teams, or the nuclei of performance committees, hospitalists are increasingly described as being in the middle of efforts to improve quality. On this basis, the discipline appears to be living up to expectations, though experts say more research is needed to better assess the impacts of HM on quality.

Dr. Vaidyan says hospitalists are particularly well positioned to understand what constitutes ideal care from the perspective of patients. "They want to be treated well: That’s patient satisfaction," he says. "They want to have their chief complaint—why they came to the hospital—properly addressed, so you need a coordinated care team. They want to go home early and don’t want come back: That’s low length of stay and a reduction in 30-day readmissions. And they don’t want any hospital-acquired complications."

Treating patients better, then, should be reflected by improved quality, even if the participation of hospitalists cannot be precisely quantified. "Being involved is something that may be difficult to measure," Dr. Gavi says, "but nonetheless, it has an important impact." TH

Bryn Nelson is a medical writer based in Seattle.

References

- Pronovost PJ, Lilford R. Analysis & commentary: A roadmap for improving the performance of performance measures. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(4):569-73.

- López L, Hicks LS, Cohen AP, McKean S, Weissman JS. Hospitalists and the quality of care in hospitals. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(15):1389-1394.

- Centor RM, Taylor BB. Do hospitalists improve quality? Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(15):1351-1352.

- Boyte D, Verma L, Wightman M. A multidisciplinary approach to reducing heart failure readmissions. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(4)Supp 2:S14.

- Williams MV, Hansen L, Greenwald J, Howell E, et al. BOOST: impact of a quality improvement project to reduce rehospitalizations. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(4) Supp 2:S88. BOOST: impact of a quality improvement project to reduce rehospitalizations.

- Auerbach AD, Wachter RM, Katz P, Showstack J, Baron RB, Goldman L. Implementation of a voluntary hospitalist service at a community teaching hospital: improved clinical efficiency and patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):859-865.

- Meltzer D, Manning WG, Morrison J, et al. Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(1):866-874.

- Huddleston JM, Hall K, Naessens JM, et al. Medical and surgical comanagement after elective hip and knee arthroplasty. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(1):28-38.

- Batsis JA, Phy MP, Melton LJ, et al. Effects of a hospitalist care model on mortality of elderly patients with hip fractures. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(4): 219–225.

- Lindenauer PK, Rothberg MB, Pekow PS, et al. Outcomes of care by hospitalists, general internists, and family physicians. N Eng J Med. 2007;357:2589-2600.

- Hock Lee K, Yang Y, Soong Yang K, Chi Ong B, Seong Ng H. Bringing generalists into the hospital: outcomes of a family medicine hospitalist model in Singapore. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(3):115-121.

- Sprague L. The hospitalist: better value in inpatient care? National Health Policy Forum website. Available at: www.nhpf.org/library/issue-briefs/IB842_Hospitalist_03-30-11.pdf. Accessed June 28, 2011.

One hospitalist-led pilot project produced a 61% decrease in heart failure readmission rates. Another resulted in a 33% drop in all-cause readmissions. The numbers might be impressive, but what do they really say about how hospitalists have influenced healthcare quality?

When HM emerged 15 years ago, advocates pitched the fledgling physician specialty as a model of efficient inpatient care, and subsequent findings that the concept led to reductions in length of stay encouraged more hospitals to bolster their staff with the newcomers. With a rising emphasis on quality and patient safety over the past decade, and the new era of pay-for-performance, the hospitalist model of care has expanded to embrace improved quality of care as a chief selling point.

Measuring quality is no easy task, however, and researchers still debate the relative merits of metrics like 30-day readmission rates and inpatient mortality. "Without question, quality measurement is an imperfect science, and all measures will contain some level of imprecision and bias," concluded a recent commentary in Health Affairs.1

Against that backdrop, relatively few studies have looked broadly at the contributions of hospital medicine. Most interventions have been individually tailored to a hospital or instituted at only a few sites, precluding large-scale, head-to-head comparisons.

And so the question remains: Has hospital medicine lived up to its promise on quality?

The Evidence

In one of the few national surveys of HM’s impact on patient care, a yearlong comparison of more than 3,600 hospitals found that the roughly 40% that employed hospitalists scored better on multiple Hospital Quality Alliance indicators. The 2009 Archives of Internal Medicine study suggested that hospitals with hospitalists outperformed their counterparts in quality metrics for acute myocardial infarction, pneumonia, overall disease treatment and diagnosis, and counseling and prevention. Congestive heart failure was the only category of the five reviewed that lacked a statistically significant difference.2

A separate editorial, however, argued that the study’s data were not persuasive enough to support the conclusion that hospitalists bring a higher quality of care to the table.3 And even less can be said about the national impact of HM on newly elevated metrics, such as readmission rates. The obligation to gather evidence, in fact, is largely falling upon hospitalists themselves, and the multitude of research abstracts from SHM’s annual meeting in May suggests that plenty of physician scientists are taking the responsibility seriously. Among the presentations, a study led by David Boyte, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Duke University and a hospitalist at Durham Regional Hospital, found that a multidisciplinary approach greatly improved one hospital unit’s 30-day readmission rates for heart failure patients. After a three-month pilot in the cardiac nursing unit, readmission rates fell to 10.7% from 27.6%.4

Although the multidisciplinary effort has included doctors, nurses, nutritionists, pharmacists, unit managers, and other personnel, Dr. Boyte says the involvement of hospitalists has been key to the project’s success. "We feel like we were the main participants who could see the whole picture from a patient-centered perspective," he says. "We were the glue; we were the center node of all the healthcare providers." Based on that dramatic improvement, Dr. Boyte says, the same interventional protocol has been rolled out in three other medical surgical units, and the hospital is using a similar approach to address AMI readmission rates.

SHM’s Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions; www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost )—by far the largest study of how HM is impacting readmission rates—has amassed data from more than 20 hospitals, with more expected from a growing roster of participants. So far, however, the project has only released data from six pilot sites describing the six-month periods before and after the project’s start. Among those sites, initial results suggest that readmission rates fell by an average of more than 20%, to 11.2% from 14.2%.5

Though the early numbers are encouraging, experts say rates from a larger group of participants at the one-year mark will be more telling, as will direct comparisons between BOOST units and nonparticipating counterparts at the same hospitals. Principal investigator Mark Williams, MD, FHM, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, says researchers still need to clean up that data before they’re ready to share it publicly.

In the meantime, some individual BOOST case studies are suggesting that hospitalist-led changes could pay big dividends. To help create cohesiveness and a sense of ownership within its HM program, St. Mary’s Health Center in St. Louis started a 20-bed hospitalist unit in 2008. Philip Vaidyan, MD, FACP, head of the hospitalist program and practice group leader for IPC: The Hospitalist Company at St. Mary’s, says one unit, 3 West, has since functioned as a lab for testing new ideas that are then introduced hospitalwide.

One early change was to bring all of the unit’s care providers together, from doctors and nurses to the unit-based case manager and social worker, for 9 a.m. handoff meetings. "We have this collective brain to find unique solutions," Dr. Vaidyan says. After seeing positive trends on length of stay, 30-day readmission rates, and patient satisfaction scores, St. Mary’s upgraded to a 32-bed hospitalist unit in early 2009. That same year, the 525-bed community teaching hospital was accepted into the BOOST program.

The hospitalist unit’s improved quality scores continued under BOOST, leading to a 33% reduction in readmission rates from 2008 to 2010 (to 10.5% from 15.7%). Rates for a nonhospitalist unit, by contrast, hovered around 17%. "For reducing readmissions, people may think that you have to have a higher length of stay," Dr. Vaidyan says. But the unit trended toward a lower length of stay, in addition to its reduced 30-day readmissions and improved patient satisfaction scores.

Flush with success, the 10 physicians and four nurse practitioners in the hospitalist program have since begun spreading their best practices to the rest of the hospital units. "Hospitalists are in the best ‘sweet spot,’ " Dr. Vaidyan says, "partnering with all of the disciplines, bringing them together, and keeping everybody on the same page."

Ironically, pinpointing the contribution of hospitalists is harder when their changes produce an ecological effect throughout an entire institution, says Siddhartha Singh, MD, MS, associate chief medical officer of Medical College Physicians, the adult practice for Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee. Even so, he stresses that the impact of the two dozen hospitalists at Medical College Physicians has been felt.

"Coinciding with and following the introduction of our hospitalist program in 2004, we have noticed dramatic decreases in our length of stay throughout medicine services," he says. The same has held true for inpatient mortality. "And that, we feel, is attributable to the standardization of processes introduced by the hospitalist group." Multidisciplinary rounds; whiteboards in patient rooms; and standardized admission orders, prophylactic treatments, and discharge processes—"all of this would’ve been impossible, absolutely impossible, without the hospitalist," he says.

Over the past decade, Dr. Singh’s assessment has been echoed by several studies suggesting that individual hospitalist programs have brought significant improvements in quality measures, such as complication rates and inpatient mortality. In 2002, for example, Andrew Auerbach, MD, MPH, at the University of California San Francisco Medical Center, led a study that compared HM care with that of community physicians in a community-based teaching hospital. Patients cared for by hospitalists, the study found, had a lower risk of death during the hospitalization, as well as at 30 days and 60 days after discharge.6

A separate report by David Meltzer, MD, PhD, and colleagues at the University of Chicago found that an HM program in an academic general medicine service led to a 30% reduction in 30-day mortality rates during its second year of operation.7 And a 2004 study led by Jeanne Huddleston, MD, at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine in Rochester, Minn., found that a hospitalist-orthopedic co-management model (versus care by orthopedic surgeons with medical consultation) led to more patients being discharged with no complications after elective hip or knee surgery.8 Hospitalist co-management also reduced the rate of minor complications, but had no effect on actual length of stay or cost.

A subsequent study by the same group, however, documented improved efficiency of care through the HM model, but no effect on the mortality of hip fracture patients up to one year after discharge.9 Multiple studies of hospitalist programs, in fact, have seen increased efficiency but little or no impact on inpatient mortality, leading researchers to broadly conclude that such programs can decrease resource use without compromising quality.

In 2007, a retrospective study of nearly 77,000 patients admitted to 45 hospitals with one of seven common diagnoses compared the care delivered by hospitalists, general internists, and family physicians.10 Although the study authors found that hospitalist care yielded a small drop in length of stay, they saw no difference in the inpatient mortality rates or 14-day readmission rates. More recently, mortality has become ensnared in controversy over its reliability as an accurate indicator of quality.

-Shai Gavi, DO, MPH, chief, section of hospital medicine, assistant professor, Stony Brook University School of Medicine, Brookhaven, N.Y.

Half of the Equation

Despite a lack of ideal metrics, another promising sign for HM might be the model’s exportability. Lee Kheng Hock, MMed, senior consultant and head of the Department of Family Medicine and Continuing Care at Singapore General Hospital, says the 1,600-bed hospital began experimenting with the hospitalist model when officials realized the existing care system wasn’t sustainable. Amid an aging population and increasingly complex and fragmented care, Hock views the hospitalist movement as a natural evolution of the healthcare system to meet the needs of a changing environment.

In a recent study, Hock and his colleagues used the hospital’s administrative database to examine the resource use and outcomes of patients cared for in 2008 by family medicine hospitalists or by specialists.11 The comparison, based on several standard metrics, found no significant improvements in quality, with similar inpatient mortality rates and 30-day, all-cause, unscheduled readmission rates regardless of the care delivery method. The study, though, revealed a significantly shorter hospital stay (4.4 days vs. 5.3 days) and lower costs per patient for those cared for by hospitalists ($2,250 vs. $2,500).11

Hock points out that, like his study, most analyses of hospitalist programs have shown an improvement in length of stay and cost of care without any increase in mortality and morbidity. If value equals quality divided by cost, he says, it stands to reason that quality must increase as overall value remains the same but costs decrease.

"The main difference is that the patients received undivided attention from a well-rounded generalist physician who is focused on providing holistic general medical care," Hock says, adding that "it is really a no-brainer that the outcome would be different."

Patients Rule

Other measures like the effectiveness of communication and seamlessness of handoffs often are assessed through their impacts on patient outcomes. But Sunil Kripalani, MD, MSc, SFHM, chief of the section of hospital medicine and an associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., says communication is now a primary focal point in Medicare’s new hospital value-based purchasing program (VBP). Within VBP’s Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) component, worth 30% of a hospital’s sum score, four of the 10 survey-based measures deal directly with communication. Patients’ overall rating and recommendation of hospitals likely will reflect their satisfaction with communication as well. Dr. Kripalani says it’s inevitable that hospitals—and hospitalists—will pay more attention to communication ratings as patients become judges of quality.

The expertise of hospitalists in handling challenging patients also leads to improved quality over time, says Shai Gavi, DO, MPH, chief of the section of hospital medicine and assistant professor of clinical medicine at Stony Brook University School of Medicine in Brookhaven, N.Y. Hospitalists, he says, excel in handling such high-stakes medical issues as gastrointestinal bleeding, pancreatitis, sepsis, and pain management that can quickly impact patient outcomes if not addressed properly and proficiently. "I think there’s significant value to having people who do this on a pretty frequent basis," he says.

And because of their broad day-to-day interactions, Dr. Gavi says, hospitalists are natural choices for committees focused on improving quality. "When we sit on committees, people often look to us for answers and directions because they know we’re on the front lines and we’ve interfaced with all of the services in the hospital," he says. "You have a good view of the whole hospital operation from A to Z, and I think that’s pretty unique to hospitalists."

The Verdict

In a recent issue brief by Lisa Sprague, principal policy analyst at the National Health Policy Forum, she asserts, "Hospitalists have the undeniable advantage of being there when a crisis occurs, when a patient is ready for discharge, and so on."12

So is "being there" the defining concept of hospital medicine, as she subsequently suggests?

Based on both scientific and anecdotal evidence, the contribution of hospitalists to healthcare quality might be better summarized as "being involved." Whether as innovators, navigators, physician champions, the "sweet spot" of interdepartmental partnerships, the "glue" of multidisciplinary teams, or the nuclei of performance committees, hospitalists are increasingly described as being in the middle of efforts to improve quality. On this basis, the discipline appears to be living up to expectations, though experts say more research is needed to better assess the impacts of HM on quality.

Dr. Vaidyan says hospitalists are particularly well positioned to understand what constitutes ideal care from the perspective of patients. "They want to be treated well: That’s patient satisfaction," he says. "They want to have their chief complaint—why they came to the hospital—properly addressed, so you need a coordinated care team. They want to go home early and don’t want come back: That’s low length of stay and a reduction in 30-day readmissions. And they don’t want any hospital-acquired complications."

Treating patients better, then, should be reflected by improved quality, even if the participation of hospitalists cannot be precisely quantified. "Being involved is something that may be difficult to measure," Dr. Gavi says, "but nonetheless, it has an important impact." TH

Bryn Nelson is a medical writer based in Seattle.

References

- Pronovost PJ, Lilford R. Analysis & commentary: A roadmap for improving the performance of performance measures. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(4):569-73.

- López L, Hicks LS, Cohen AP, McKean S, Weissman JS. Hospitalists and the quality of care in hospitals. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(15):1389-1394.

- Centor RM, Taylor BB. Do hospitalists improve quality? Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(15):1351-1352.

- Boyte D, Verma L, Wightman M. A multidisciplinary approach to reducing heart failure readmissions. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(4)Supp 2:S14.

- Williams MV, Hansen L, Greenwald J, Howell E, et al. BOOST: impact of a quality improvement project to reduce rehospitalizations. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(4) Supp 2:S88. BOOST: impact of a quality improvement project to reduce rehospitalizations.

- Auerbach AD, Wachter RM, Katz P, Showstack J, Baron RB, Goldman L. Implementation of a voluntary hospitalist service at a community teaching hospital: improved clinical efficiency and patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):859-865.

- Meltzer D, Manning WG, Morrison J, et al. Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(1):866-874.

- Huddleston JM, Hall K, Naessens JM, et al. Medical and surgical comanagement after elective hip and knee arthroplasty. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(1):28-38.

- Batsis JA, Phy MP, Melton LJ, et al. Effects of a hospitalist care model on mortality of elderly patients with hip fractures. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(4): 219–225.

- Lindenauer PK, Rothberg MB, Pekow PS, et al. Outcomes of care by hospitalists, general internists, and family physicians. N Eng J Med. 2007;357:2589-2600.

- Hock Lee K, Yang Y, Soong Yang K, Chi Ong B, Seong Ng H. Bringing generalists into the hospital: outcomes of a family medicine hospitalist model in Singapore. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(3):115-121.

- Sprague L. The hospitalist: better value in inpatient care? National Health Policy Forum website. Available at: www.nhpf.org/library/issue-briefs/IB842_Hospitalist_03-30-11.pdf. Accessed June 28, 2011.

Discharge improvement

If you’re a hospitalist interested in reducing readmissions in your hospital, the time to act is now.

Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions), SHM’s groundbreaking program designed to help hospitals reduce unplanned readmissions, is now accepting applications for two new cohorts: one national and another specific to California. The deadline for applications is August 1.

Now with 85 sites as part of the national community, Project BOOST will introduce new sites across the country in the fall. In addition to the national cohort, Project BOOST will also establish a new cohort in California, with discounted tuition through grants from three healthcare groups in the state.

“It’s a great time to apply,” says Stephanie Rennke, MD, assistant clinical professor of medicine at the University of California San Francisco Medical Center. “We are at the cusp of a lot of big changes in health reform. The time to address readmissions is now. Hospitals will have to address this, and BOOST is one way to do that.”

—Stephanie Rennke, MD, assistant clinical professor of medicine, University of California San Francisco Medical Center

Applications are submitted online (www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost) and evaluated based on whether improving discharge and care transitions is a high priority at the institution. Applications must be accompanied by a letter of support from an executive sponsor within the applicant’s hospital.

Once accepted into the program, BOOST participants pay a tuition fee of $28,000. Thanks to the support of the California HealthCare Foundation, the L.A. Care Health Plan, and the Hospital Association of Southern California, sites in California are eligible for reduced tuition based on site location and availability of funds.

For Dr. Rennke, the link between healthcare reform and readmissions is clear, along with the repercussions for hospitals. Most notably, the discharge process affects multiple quality issues, including “patient satisfaction, provider satisfaction and improving communication from hospital to home.”

“Hospitals need to realize healthcare reform is coming,” says Dr. Rennke, who previously served as a Project BOOST site team member and now works as a BOOST mentor. “Not only is reducing readmissions the right thing to do, it will also have a financial impact for hospitals that don’t address it. … It’s going to be of paramount importance to address the discharge process.”

National Growth

Since it was initially developed through a grant from the John A. Hartford Foundation, Project BOOST has spread to hospitals across the country and received widespread attention throughout the healthcare community.

At the time of Project BOOST’s inception in 2008, readmissions already were an intractable and costly issue for hospitals. The next year, research coauthored by Project BOOST principal investigator Mark V. Williams, MD, FHM, and published in the New England Journal of Medicine revealed that unplanned readmissions cost Medicare $17.4 billion annually.

Project BOOST’s pilot cohort consisted of six hospital sites. The program’s growth accelerated quickly, and it soon added another 24 sites and, later, two statewide programs in Michigan and Illinois.

The popularity of Project BOOST among hospitals has captured the attention of media and other organizations as well:

- This year, Kaiser Health News featured the work of Atlanta’s Piedmont Hospital to reduce readmissions using Project BOOST in an article focusing on the impact of healthcare reform laws on hospital readmissions.

- The Bassett Healthcare Network, a Project BOOST site in upstate New York, has earned the Hospital Association of New York State’s prestigious 2011 HANYS Pinnacle Award for Quality and Safety for the group’s care-transition work. The award was presented to Bassett Healthcare Network chief executives in June.

- In California, the Kaiser Permanente West LA BOOST Team was recognized with an award from Dr. Benjamin Chu, president of Southern California Kaiser Foundation Health Plan.

- In December 2010, Dr. Williams and hospitalist Matthew Schreiber, CMO of Piedmont Hospital, shared their experiences with Project BOOST at a national conference hosted by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

The Project BOOST Process

Once a site is accepted as a Project BOOST site, the site leader receives an information package and access to the Project BOOST online repository for recording and uploading readmission data. Then, each Project BOOST cohort performs an in-person conference. Networking and personal interaction are an important part of sharing challenges and successes in reducing readmissions. The conference also includes training on root-cause analysis and process mapping, a required step for application of the new Community Based Care Transitions Program (CCTP), part of the Affordable Care Act.

Each site leader is assigned a Project BOOST mentor, a national expert on reducing readmissions to the hospital. The mentor conducts a site visit to the hospital to meet the entire team in person and better understand the discharge challenges first-hand.

Over the course of the year, through regularly scheduled telephone calls, the mentor works with the Project BOOST team to best apply the program to the needs of the specific hospital. Mentors also help answer questions related to project planning, toolkit materials, data collection, implementation, and analysis.

In Dr. Rennke’s case, the process helped augment and guide UCSF’s current discharge program. Having multiple team members from different disciplines made distributing the work and implementation easier.

“Overall, we knew this was going to be doable because we incorporated Project BOOST into an already existing discharge process,” Dr. Rennke says.

Readmissions in the Crosshairs

The impacts of preventable readmissions on patient safety and efficiency of care in the hospital have made the issue a heated one in public policy. Earlier this year, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services announced the creation of Partnership for Patients, a $1 billion initiative to address “quality, safety, and affordability of healthcare for all Americans.” SHM was one of the first medical societies to sign on to the “Partnership for Patients Pledge.”

One of the partnership’s two major goals is to reduce hospital readmissions by 20%. According to the Partnership for Patients website, “achieving this goal would mean more than 1.6 million patients would recover from illness without suffering a preventable complication requiring rehospitalization within 30 days of discharge.”

The government is backing up this goal with funding for hospitals with concrete plans to reduce readmissions. Under the Affordable Care Act of 2010—commonly known as the healthcare reform law—Medicare created the five-year CCTP earlier this year. The program provides $500 million to collaborative partnerships between hospitals and community-based organizations to implement care-transition services for Medicare beneficiaries, many of whom are at high risk of readmission.

To Dr. Rennke, the attention to reducing readmissions is an extension of her responsibility as a caregiver. “Our responsibility doesn’t end when the patient leaves the hospital,” she says. TH

Brendon Shank is SHM’s assistant vice president of communications.

If you’re a hospitalist interested in reducing readmissions in your hospital, the time to act is now.

Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions), SHM’s groundbreaking program designed to help hospitals reduce unplanned readmissions, is now accepting applications for two new cohorts: one national and another specific to California. The deadline for applications is August 1.

Now with 85 sites as part of the national community, Project BOOST will introduce new sites across the country in the fall. In addition to the national cohort, Project BOOST will also establish a new cohort in California, with discounted tuition through grants from three healthcare groups in the state.

“It’s a great time to apply,” says Stephanie Rennke, MD, assistant clinical professor of medicine at the University of California San Francisco Medical Center. “We are at the cusp of a lot of big changes in health reform. The time to address readmissions is now. Hospitals will have to address this, and BOOST is one way to do that.”

—Stephanie Rennke, MD, assistant clinical professor of medicine, University of California San Francisco Medical Center

Applications are submitted online (www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost) and evaluated based on whether improving discharge and care transitions is a high priority at the institution. Applications must be accompanied by a letter of support from an executive sponsor within the applicant’s hospital.

Once accepted into the program, BOOST participants pay a tuition fee of $28,000. Thanks to the support of the California HealthCare Foundation, the L.A. Care Health Plan, and the Hospital Association of Southern California, sites in California are eligible for reduced tuition based on site location and availability of funds.

For Dr. Rennke, the link between healthcare reform and readmissions is clear, along with the repercussions for hospitals. Most notably, the discharge process affects multiple quality issues, including “patient satisfaction, provider satisfaction and improving communication from hospital to home.”

“Hospitals need to realize healthcare reform is coming,” says Dr. Rennke, who previously served as a Project BOOST site team member and now works as a BOOST mentor. “Not only is reducing readmissions the right thing to do, it will also have a financial impact for hospitals that don’t address it. … It’s going to be of paramount importance to address the discharge process.”

National Growth

Since it was initially developed through a grant from the John A. Hartford Foundation, Project BOOST has spread to hospitals across the country and received widespread attention throughout the healthcare community.

At the time of Project BOOST’s inception in 2008, readmissions already were an intractable and costly issue for hospitals. The next year, research coauthored by Project BOOST principal investigator Mark V. Williams, MD, FHM, and published in the New England Journal of Medicine revealed that unplanned readmissions cost Medicare $17.4 billion annually.

Project BOOST’s pilot cohort consisted of six hospital sites. The program’s growth accelerated quickly, and it soon added another 24 sites and, later, two statewide programs in Michigan and Illinois.

The popularity of Project BOOST among hospitals has captured the attention of media and other organizations as well:

- This year, Kaiser Health News featured the work of Atlanta’s Piedmont Hospital to reduce readmissions using Project BOOST in an article focusing on the impact of healthcare reform laws on hospital readmissions.

- The Bassett Healthcare Network, a Project BOOST site in upstate New York, has earned the Hospital Association of New York State’s prestigious 2011 HANYS Pinnacle Award for Quality and Safety for the group’s care-transition work. The award was presented to Bassett Healthcare Network chief executives in June.

- In California, the Kaiser Permanente West LA BOOST Team was recognized with an award from Dr. Benjamin Chu, president of Southern California Kaiser Foundation Health Plan.

- In December 2010, Dr. Williams and hospitalist Matthew Schreiber, CMO of Piedmont Hospital, shared their experiences with Project BOOST at a national conference hosted by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

The Project BOOST Process

Once a site is accepted as a Project BOOST site, the site leader receives an information package and access to the Project BOOST online repository for recording and uploading readmission data. Then, each Project BOOST cohort performs an in-person conference. Networking and personal interaction are an important part of sharing challenges and successes in reducing readmissions. The conference also includes training on root-cause analysis and process mapping, a required step for application of the new Community Based Care Transitions Program (CCTP), part of the Affordable Care Act.

Each site leader is assigned a Project BOOST mentor, a national expert on reducing readmissions to the hospital. The mentor conducts a site visit to the hospital to meet the entire team in person and better understand the discharge challenges first-hand.

Over the course of the year, through regularly scheduled telephone calls, the mentor works with the Project BOOST team to best apply the program to the needs of the specific hospital. Mentors also help answer questions related to project planning, toolkit materials, data collection, implementation, and analysis.

In Dr. Rennke’s case, the process helped augment and guide UCSF’s current discharge program. Having multiple team members from different disciplines made distributing the work and implementation easier.

“Overall, we knew this was going to be doable because we incorporated Project BOOST into an already existing discharge process,” Dr. Rennke says.

Readmissions in the Crosshairs

The impacts of preventable readmissions on patient safety and efficiency of care in the hospital have made the issue a heated one in public policy. Earlier this year, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services announced the creation of Partnership for Patients, a $1 billion initiative to address “quality, safety, and affordability of healthcare for all Americans.” SHM was one of the first medical societies to sign on to the “Partnership for Patients Pledge.”

One of the partnership’s two major goals is to reduce hospital readmissions by 20%. According to the Partnership for Patients website, “achieving this goal would mean more than 1.6 million patients would recover from illness without suffering a preventable complication requiring rehospitalization within 30 days of discharge.”

The government is backing up this goal with funding for hospitals with concrete plans to reduce readmissions. Under the Affordable Care Act of 2010—commonly known as the healthcare reform law—Medicare created the five-year CCTP earlier this year. The program provides $500 million to collaborative partnerships between hospitals and community-based organizations to implement care-transition services for Medicare beneficiaries, many of whom are at high risk of readmission.

To Dr. Rennke, the attention to reducing readmissions is an extension of her responsibility as a caregiver. “Our responsibility doesn’t end when the patient leaves the hospital,” she says. TH

Brendon Shank is SHM’s assistant vice president of communications.

If you’re a hospitalist interested in reducing readmissions in your hospital, the time to act is now.

Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions), SHM’s groundbreaking program designed to help hospitals reduce unplanned readmissions, is now accepting applications for two new cohorts: one national and another specific to California. The deadline for applications is August 1.

Now with 85 sites as part of the national community, Project BOOST will introduce new sites across the country in the fall. In addition to the national cohort, Project BOOST will also establish a new cohort in California, with discounted tuition through grants from three healthcare groups in the state.

“It’s a great time to apply,” says Stephanie Rennke, MD, assistant clinical professor of medicine at the University of California San Francisco Medical Center. “We are at the cusp of a lot of big changes in health reform. The time to address readmissions is now. Hospitals will have to address this, and BOOST is one way to do that.”

—Stephanie Rennke, MD, assistant clinical professor of medicine, University of California San Francisco Medical Center

Applications are submitted online (www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost) and evaluated based on whether improving discharge and care transitions is a high priority at the institution. Applications must be accompanied by a letter of support from an executive sponsor within the applicant’s hospital.

Once accepted into the program, BOOST participants pay a tuition fee of $28,000. Thanks to the support of the California HealthCare Foundation, the L.A. Care Health Plan, and the Hospital Association of Southern California, sites in California are eligible for reduced tuition based on site location and availability of funds.

For Dr. Rennke, the link between healthcare reform and readmissions is clear, along with the repercussions for hospitals. Most notably, the discharge process affects multiple quality issues, including “patient satisfaction, provider satisfaction and improving communication from hospital to home.”

“Hospitals need to realize healthcare reform is coming,” says Dr. Rennke, who previously served as a Project BOOST site team member and now works as a BOOST mentor. “Not only is reducing readmissions the right thing to do, it will also have a financial impact for hospitals that don’t address it. … It’s going to be of paramount importance to address the discharge process.”

National Growth

Since it was initially developed through a grant from the John A. Hartford Foundation, Project BOOST has spread to hospitals across the country and received widespread attention throughout the healthcare community.

At the time of Project BOOST’s inception in 2008, readmissions already were an intractable and costly issue for hospitals. The next year, research coauthored by Project BOOST principal investigator Mark V. Williams, MD, FHM, and published in the New England Journal of Medicine revealed that unplanned readmissions cost Medicare $17.4 billion annually.

Project BOOST’s pilot cohort consisted of six hospital sites. The program’s growth accelerated quickly, and it soon added another 24 sites and, later, two statewide programs in Michigan and Illinois.

The popularity of Project BOOST among hospitals has captured the attention of media and other organizations as well:

- This year, Kaiser Health News featured the work of Atlanta’s Piedmont Hospital to reduce readmissions using Project BOOST in an article focusing on the impact of healthcare reform laws on hospital readmissions.

- The Bassett Healthcare Network, a Project BOOST site in upstate New York, has earned the Hospital Association of New York State’s prestigious 2011 HANYS Pinnacle Award for Quality and Safety for the group’s care-transition work. The award was presented to Bassett Healthcare Network chief executives in June.

- In California, the Kaiser Permanente West LA BOOST Team was recognized with an award from Dr. Benjamin Chu, president of Southern California Kaiser Foundation Health Plan.

- In December 2010, Dr. Williams and hospitalist Matthew Schreiber, CMO of Piedmont Hospital, shared their experiences with Project BOOST at a national conference hosted by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

The Project BOOST Process

Once a site is accepted as a Project BOOST site, the site leader receives an information package and access to the Project BOOST online repository for recording and uploading readmission data. Then, each Project BOOST cohort performs an in-person conference. Networking and personal interaction are an important part of sharing challenges and successes in reducing readmissions. The conference also includes training on root-cause analysis and process mapping, a required step for application of the new Community Based Care Transitions Program (CCTP), part of the Affordable Care Act.

Each site leader is assigned a Project BOOST mentor, a national expert on reducing readmissions to the hospital. The mentor conducts a site visit to the hospital to meet the entire team in person and better understand the discharge challenges first-hand.

Over the course of the year, through regularly scheduled telephone calls, the mentor works with the Project BOOST team to best apply the program to the needs of the specific hospital. Mentors also help answer questions related to project planning, toolkit materials, data collection, implementation, and analysis.

In Dr. Rennke’s case, the process helped augment and guide UCSF’s current discharge program. Having multiple team members from different disciplines made distributing the work and implementation easier.

“Overall, we knew this was going to be doable because we incorporated Project BOOST into an already existing discharge process,” Dr. Rennke says.

Readmissions in the Crosshairs

The impacts of preventable readmissions on patient safety and efficiency of care in the hospital have made the issue a heated one in public policy. Earlier this year, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services announced the creation of Partnership for Patients, a $1 billion initiative to address “quality, safety, and affordability of healthcare for all Americans.” SHM was one of the first medical societies to sign on to the “Partnership for Patients Pledge.”

One of the partnership’s two major goals is to reduce hospital readmissions by 20%. According to the Partnership for Patients website, “achieving this goal would mean more than 1.6 million patients would recover from illness without suffering a preventable complication requiring rehospitalization within 30 days of discharge.”

The government is backing up this goal with funding for hospitals with concrete plans to reduce readmissions. Under the Affordable Care Act of 2010—commonly known as the healthcare reform law—Medicare created the five-year CCTP earlier this year. The program provides $500 million to collaborative partnerships between hospitals and community-based organizations to implement care-transition services for Medicare beneficiaries, many of whom are at high risk of readmission.

To Dr. Rennke, the attention to reducing readmissions is an extension of her responsibility as a caregiver. “Our responsibility doesn’t end when the patient leaves the hospital,” she says. TH

Brendon Shank is SHM’s assistant vice president of communications.

HM=Improved Patient Care

GRAPEVINE, Texas—The most successful companies tend to have superior branding. Starbucks owns coffee. Disney owns family fun. And hospitalists own patient-safety and quality-improvement (QI) initiatives within their hospitals.

“We were pretty confident that if we embraced this, we would have a clear running field to ourselves,” says Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, professor, chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine, and chief of the Medical Service at the University of California at San Francisco Medical Center, former SHM president, and author of the Wachter’s World blog. “No other physician field would do the same thing, and by owning the patient-safety field, we would distinguish ourselves.”

Now comes the really hard part, though.

Three keynote speakers at HM11—Dr. Wachter, AMA President Cecil Wilson, MD, and Robert Kocher, MD, a healthcare policy advisor to President Obama—pointed to hospitalists as the physician cohort that can help shepherd the conceptual reform passed last year by Congress into daily practice in America’s hospitals. And all three also point to HM’s role at the vanguard of patient safety as a primary reason why.

Hurdles will arise, Dr. Wilson says. A solo practitioner most of his career, he says hospitalists can play a key role in the coming years as more patients receive insurance, but looming doctor shortages could stymie the cause. While many caution that the flood of newly insured patients will overburden primary-care physicians (PCPs), the expected shortage of physicians will plague HM as well.

“Hospitalists are primary-care physicians; the vast majority of them are general internists,” Dr. Wilson says. “… So when we say that the number of people who are going into primary care, particularly general internal medicine, is reducing, that reduces not only the pool of physicians in the community, but also the hospitalist pool. We’re in that boat together.”

Dr. Kocher, director of the McKinsey Center for U.S. Health System Reform in Washington, D.C., says hospitalists are in the best position to push for on-the-ground reform as they are the doctors who bridge all hospital departments, floors, and wards. He sees four broad areas where HM can take a particularly leading role:

- Increasing labor productivity. HM’s role as a link between specialties from cardiology to the pharmacy makes HM a natural conduit to push institutional values from a unique vantage point.

- Driving decision-making. Whether it’s recommending less costly drugs with similar outcomes, questioning whether expensive test batteries are truly necessary or being done for fear of missing something, or pausing to ask whether a “90-year-old hip replacement patient should receive orthopedic implants that will last far longer than their grandkids will be alive,” hospitalists can use their data to be a common-sense lynchpin of daily operations.

- Using technology to lower delivery costs. Many insurance companies are willing to enter into risk-based contracts with hospitals, but some hospital executives worry whether they will be able to perform well enough to justify the risk. “Hospitalists can help say, ‘We can do this. We can hit the thresholds.’ ”

- Shifting compensation models from “selling work RVUs to selling years of health.”