User login

Hospital Medicine Leaders Set to Converge for HM13

Every year, thousands of hospitalists gather to share their experiences, challenges, and energy with each other at SHM’s annual meeting. In 2013, hospitalists can do all of that while visiting the nation’s capital.

And make a real difference by advocating on Capitol Hill for quality improvement and safety in hospitals.

And enjoy all the amenities of a first-class hotel and conference center under one roof.

And get ahead of the curve on some of the most pressing topics in healthcare, such as the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation’s Choosing Wisely campaign.

But in order to do all of that, hospitalists have to register for HM13, and must do so quickly to save $50. The early registration deadline is March 19, earlier than in prior years. So don’t wait—sign up now at www.hospitalmedicine2013.org.

Choosing Wisely

Are you ready to make wise choices? HM13 provides unprecedented access to the hospitalist experts who developed the lists of recommendations for the Choosing Wisely campaign with two educational sessions and a pre-course.

Before HM13 kicks off, hospitalists John Bulger, DO, FACP, SFHM, and Ian Jenkins, MD, will direct a full-day Choosing Wisely pre-course on Thursday, May 16, featuring didactic sessions in the morning with national experts in QI on such topics as teambuilding and making the case for quality. The afternoon session will encompass highly interactive workgroups utilizing skills learned in the morning to develop a plan for how to “choose wisely.” Attendees will apply quality methodologies to frequently overutilized tests or procedures, resulting in an actual plan for embedding “avoids” or “never-dos” into their own practice in their own institutions.

On Saturday, May 18, Douglas Carlson, MD, and Ricardo Quinonez, MD, FAAP, FHM, will present “Addressing Overuse in Pediatric Hospital Medicine: The ABIM Choosing Wisely Campaign—PHM Recommendations,” and on Sunday, May 19, Drs. Bulger and Jenkins will present “Choosing Wisely: 5 Things Physicians and Patients Should Question.”

New Featured Speaker

Back by popular demand, hospitalist Patrick Conway, MD, MSc, FAAP, SFHM, chief medical officer and the director of the Office of Clinical Standards and Quality Centers for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), will speak on the role hospitalists will play as change agents for healthcare reform and patient safety in the years to come. Dr. Conway replaces quality expert Peter Pronovost, MD, who had a scheduling conflict and will not be able to speak at HM13.

Get Your Conference In Hand

Hospitalists continue to be ahead of the curve, and the technology at HM13 is no exception. This year’s HM13 At Hand conference app for smartphones and tablets enables conference-goers to plan their schedule ahead of time, download meeting content, play a scavenger hunt for prizes, and socialize with other attendees.

The app’s scheduling feature offers attendees the chance to explore their options ahead of time or make changes on the fly to their HM13 experience.

For links to download the HM13 app, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org.

Every year, thousands of hospitalists gather to share their experiences, challenges, and energy with each other at SHM’s annual meeting. In 2013, hospitalists can do all of that while visiting the nation’s capital.

And make a real difference by advocating on Capitol Hill for quality improvement and safety in hospitals.

And enjoy all the amenities of a first-class hotel and conference center under one roof.

And get ahead of the curve on some of the most pressing topics in healthcare, such as the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation’s Choosing Wisely campaign.

But in order to do all of that, hospitalists have to register for HM13, and must do so quickly to save $50. The early registration deadline is March 19, earlier than in prior years. So don’t wait—sign up now at www.hospitalmedicine2013.org.

Choosing Wisely

Are you ready to make wise choices? HM13 provides unprecedented access to the hospitalist experts who developed the lists of recommendations for the Choosing Wisely campaign with two educational sessions and a pre-course.

Before HM13 kicks off, hospitalists John Bulger, DO, FACP, SFHM, and Ian Jenkins, MD, will direct a full-day Choosing Wisely pre-course on Thursday, May 16, featuring didactic sessions in the morning with national experts in QI on such topics as teambuilding and making the case for quality. The afternoon session will encompass highly interactive workgroups utilizing skills learned in the morning to develop a plan for how to “choose wisely.” Attendees will apply quality methodologies to frequently overutilized tests or procedures, resulting in an actual plan for embedding “avoids” or “never-dos” into their own practice in their own institutions.

On Saturday, May 18, Douglas Carlson, MD, and Ricardo Quinonez, MD, FAAP, FHM, will present “Addressing Overuse in Pediatric Hospital Medicine: The ABIM Choosing Wisely Campaign—PHM Recommendations,” and on Sunday, May 19, Drs. Bulger and Jenkins will present “Choosing Wisely: 5 Things Physicians and Patients Should Question.”

New Featured Speaker

Back by popular demand, hospitalist Patrick Conway, MD, MSc, FAAP, SFHM, chief medical officer and the director of the Office of Clinical Standards and Quality Centers for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), will speak on the role hospitalists will play as change agents for healthcare reform and patient safety in the years to come. Dr. Conway replaces quality expert Peter Pronovost, MD, who had a scheduling conflict and will not be able to speak at HM13.

Get Your Conference In Hand

Hospitalists continue to be ahead of the curve, and the technology at HM13 is no exception. This year’s HM13 At Hand conference app for smartphones and tablets enables conference-goers to plan their schedule ahead of time, download meeting content, play a scavenger hunt for prizes, and socialize with other attendees.

The app’s scheduling feature offers attendees the chance to explore their options ahead of time or make changes on the fly to their HM13 experience.

For links to download the HM13 app, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org.

Every year, thousands of hospitalists gather to share their experiences, challenges, and energy with each other at SHM’s annual meeting. In 2013, hospitalists can do all of that while visiting the nation’s capital.

And make a real difference by advocating on Capitol Hill for quality improvement and safety in hospitals.

And enjoy all the amenities of a first-class hotel and conference center under one roof.

And get ahead of the curve on some of the most pressing topics in healthcare, such as the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation’s Choosing Wisely campaign.

But in order to do all of that, hospitalists have to register for HM13, and must do so quickly to save $50. The early registration deadline is March 19, earlier than in prior years. So don’t wait—sign up now at www.hospitalmedicine2013.org.

Choosing Wisely

Are you ready to make wise choices? HM13 provides unprecedented access to the hospitalist experts who developed the lists of recommendations for the Choosing Wisely campaign with two educational sessions and a pre-course.

Before HM13 kicks off, hospitalists John Bulger, DO, FACP, SFHM, and Ian Jenkins, MD, will direct a full-day Choosing Wisely pre-course on Thursday, May 16, featuring didactic sessions in the morning with national experts in QI on such topics as teambuilding and making the case for quality. The afternoon session will encompass highly interactive workgroups utilizing skills learned in the morning to develop a plan for how to “choose wisely.” Attendees will apply quality methodologies to frequently overutilized tests or procedures, resulting in an actual plan for embedding “avoids” or “never-dos” into their own practice in their own institutions.

On Saturday, May 18, Douglas Carlson, MD, and Ricardo Quinonez, MD, FAAP, FHM, will present “Addressing Overuse in Pediatric Hospital Medicine: The ABIM Choosing Wisely Campaign—PHM Recommendations,” and on Sunday, May 19, Drs. Bulger and Jenkins will present “Choosing Wisely: 5 Things Physicians and Patients Should Question.”

New Featured Speaker

Back by popular demand, hospitalist Patrick Conway, MD, MSc, FAAP, SFHM, chief medical officer and the director of the Office of Clinical Standards and Quality Centers for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), will speak on the role hospitalists will play as change agents for healthcare reform and patient safety in the years to come. Dr. Conway replaces quality expert Peter Pronovost, MD, who had a scheduling conflict and will not be able to speak at HM13.

Get Your Conference In Hand

Hospitalists continue to be ahead of the curve, and the technology at HM13 is no exception. This year’s HM13 At Hand conference app for smartphones and tablets enables conference-goers to plan their schedule ahead of time, download meeting content, play a scavenger hunt for prizes, and socialize with other attendees.

The app’s scheduling feature offers attendees the chance to explore their options ahead of time or make changes on the fly to their HM13 experience.

For links to download the HM13 app, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org.

Hospitalwide Reductions in Pediatric Patient Harm are Achievable

Clinical question: Can a broadly constructed improvement initiative significantly reduce serious safety events (SSEs)?

Study design: Single-institution quality-improvement initiative.

Setting: Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Synopsis: A multidisciplinary team supported by leadership was formed to reduce SSEs across the hospital by 80% within four years. A consulting firm with expertise in the field was also engaged for this process. Multifaceted interventions were clustered according to perceived key drivers of change in the institution: error prevention systems, improved safety governance, cause analysis programs, lessons-learned programs, and specific tactical interventions.

SSEs per 10,000 adjusted patient-days decreased significantly, to a mean of 0.3 from 0.9 (P<0.0001) after implementation, while days between SSEs increased to a mean of 55.2 from 19.4 (P<0.0001).

This work represents one of the most robust single-center approaches to improving patient safety that has been published to date. The authors attribute much of their success to culture change, which required “relentless clarity of vision by the organization.” Although this substantially limits immediate generalizability of any of the specific interventions, the work stands on its own as a prime example of what may be accomplished through focused dedication to reducing patient harm.

Bottom line: Patient harm is preventable through a widespread and multifaceted institutional initiative.

Citation: Muething SE, Goudie A, Schoettker PJ, et al. Quality improvement initiative to reduce serious safety events and improve patient safety culture. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e423-431.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Clinical question: Can a broadly constructed improvement initiative significantly reduce serious safety events (SSEs)?

Study design: Single-institution quality-improvement initiative.

Setting: Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Synopsis: A multidisciplinary team supported by leadership was formed to reduce SSEs across the hospital by 80% within four years. A consulting firm with expertise in the field was also engaged for this process. Multifaceted interventions were clustered according to perceived key drivers of change in the institution: error prevention systems, improved safety governance, cause analysis programs, lessons-learned programs, and specific tactical interventions.

SSEs per 10,000 adjusted patient-days decreased significantly, to a mean of 0.3 from 0.9 (P<0.0001) after implementation, while days between SSEs increased to a mean of 55.2 from 19.4 (P<0.0001).

This work represents one of the most robust single-center approaches to improving patient safety that has been published to date. The authors attribute much of their success to culture change, which required “relentless clarity of vision by the organization.” Although this substantially limits immediate generalizability of any of the specific interventions, the work stands on its own as a prime example of what may be accomplished through focused dedication to reducing patient harm.

Bottom line: Patient harm is preventable through a widespread and multifaceted institutional initiative.

Citation: Muething SE, Goudie A, Schoettker PJ, et al. Quality improvement initiative to reduce serious safety events and improve patient safety culture. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e423-431.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Clinical question: Can a broadly constructed improvement initiative significantly reduce serious safety events (SSEs)?

Study design: Single-institution quality-improvement initiative.

Setting: Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Synopsis: A multidisciplinary team supported by leadership was formed to reduce SSEs across the hospital by 80% within four years. A consulting firm with expertise in the field was also engaged for this process. Multifaceted interventions were clustered according to perceived key drivers of change in the institution: error prevention systems, improved safety governance, cause analysis programs, lessons-learned programs, and specific tactical interventions.

SSEs per 10,000 adjusted patient-days decreased significantly, to a mean of 0.3 from 0.9 (P<0.0001) after implementation, while days between SSEs increased to a mean of 55.2 from 19.4 (P<0.0001).

This work represents one of the most robust single-center approaches to improving patient safety that has been published to date. The authors attribute much of their success to culture change, which required “relentless clarity of vision by the organization.” Although this substantially limits immediate generalizability of any of the specific interventions, the work stands on its own as a prime example of what may be accomplished through focused dedication to reducing patient harm.

Bottom line: Patient harm is preventable through a widespread and multifaceted institutional initiative.

Citation: Muething SE, Goudie A, Schoettker PJ, et al. Quality improvement initiative to reduce serious safety events and improve patient safety culture. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e423-431.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Special Interest Groups Target Healthcare Waste

As HM ramps up its efforts to eliminate wasteful and unnecessary medical treatments through its participation in the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation’s Choosing Wisely Campaign (choosingwisely.org), two new policy reports help to delineate the problem of waste in healthcare.

The Health Affairs health policy brief “Reducing Waste in Health Care” concludes that a third or more of U.S. healthcare spending could be considered wasteful.4 Its categories of waste include unnecessary services, inefficiently delivered services, excessive prices and administrative costs, fraud, and abuse—along with a handful of categories familiar to hospitalists: failures of care coordination, avoidable hospital readmissions, and missed prevention opportunities.

The policy brief offers potential solutions, including increased provider use of digital data to improve care coordination and delivery, and heightened transparency of provider performance for consumers.

On Jan. 10, the Commonwealth Fund proposed a new set of strategies to slow health spending growth by $2 trillion dollars over the next 10 years.5 The report outlines a broad set of policies to change the way healthcare is paid for, accelerating a variety of delivery system innovations already under way; disseminate better quality and cost information to enhance consumers’ ability to choose high-value care; and address the market forces that drive up costs.

“We know that by innovating and coordinating care, our healthcare system can provide better care at lower cost,” Commonwealth Fund president David Blumenthal, MD, said in the report.

References

- Health Affairs. Health Policy Brief: Reducing Waste in Health Care. Health Affairs website. Available at: http://www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_id=82. Accessed Jan. 10, 2013.

- The Commonwealth Fund Commission on a High Performance Health System. Confronting Costs: Stabilizing U.S. Health Spending While Moving Toward a High Performance Health Care System. The Commonwealth Fund website. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Publications/Fund-Reports/2013/Jan/Confronting-Costs.aspx?page=all. Accessed Feb. 2, 2013.

As HM ramps up its efforts to eliminate wasteful and unnecessary medical treatments through its participation in the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation’s Choosing Wisely Campaign (choosingwisely.org), two new policy reports help to delineate the problem of waste in healthcare.

The Health Affairs health policy brief “Reducing Waste in Health Care” concludes that a third or more of U.S. healthcare spending could be considered wasteful.4 Its categories of waste include unnecessary services, inefficiently delivered services, excessive prices and administrative costs, fraud, and abuse—along with a handful of categories familiar to hospitalists: failures of care coordination, avoidable hospital readmissions, and missed prevention opportunities.

The policy brief offers potential solutions, including increased provider use of digital data to improve care coordination and delivery, and heightened transparency of provider performance for consumers.

On Jan. 10, the Commonwealth Fund proposed a new set of strategies to slow health spending growth by $2 trillion dollars over the next 10 years.5 The report outlines a broad set of policies to change the way healthcare is paid for, accelerating a variety of delivery system innovations already under way; disseminate better quality and cost information to enhance consumers’ ability to choose high-value care; and address the market forces that drive up costs.

“We know that by innovating and coordinating care, our healthcare system can provide better care at lower cost,” Commonwealth Fund president David Blumenthal, MD, said in the report.

References

- Health Affairs. Health Policy Brief: Reducing Waste in Health Care. Health Affairs website. Available at: http://www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_id=82. Accessed Jan. 10, 2013.

- The Commonwealth Fund Commission on a High Performance Health System. Confronting Costs: Stabilizing U.S. Health Spending While Moving Toward a High Performance Health Care System. The Commonwealth Fund website. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Publications/Fund-Reports/2013/Jan/Confronting-Costs.aspx?page=all. Accessed Feb. 2, 2013.

As HM ramps up its efforts to eliminate wasteful and unnecessary medical treatments through its participation in the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation’s Choosing Wisely Campaign (choosingwisely.org), two new policy reports help to delineate the problem of waste in healthcare.

The Health Affairs health policy brief “Reducing Waste in Health Care” concludes that a third or more of U.S. healthcare spending could be considered wasteful.4 Its categories of waste include unnecessary services, inefficiently delivered services, excessive prices and administrative costs, fraud, and abuse—along with a handful of categories familiar to hospitalists: failures of care coordination, avoidable hospital readmissions, and missed prevention opportunities.

The policy brief offers potential solutions, including increased provider use of digital data to improve care coordination and delivery, and heightened transparency of provider performance for consumers.

On Jan. 10, the Commonwealth Fund proposed a new set of strategies to slow health spending growth by $2 trillion dollars over the next 10 years.5 The report outlines a broad set of policies to change the way healthcare is paid for, accelerating a variety of delivery system innovations already under way; disseminate better quality and cost information to enhance consumers’ ability to choose high-value care; and address the market forces that drive up costs.

“We know that by innovating and coordinating care, our healthcare system can provide better care at lower cost,” Commonwealth Fund president David Blumenthal, MD, said in the report.

References

- Health Affairs. Health Policy Brief: Reducing Waste in Health Care. Health Affairs website. Available at: http://www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_id=82. Accessed Jan. 10, 2013.

- The Commonwealth Fund Commission on a High Performance Health System. Confronting Costs: Stabilizing U.S. Health Spending While Moving Toward a High Performance Health Care System. The Commonwealth Fund website. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Publications/Fund-Reports/2013/Jan/Confronting-Costs.aspx?page=all. Accessed Feb. 2, 2013.

Post-Hospital Syndrome Contributes to Readmission Risk for Elderly

Post-hospital syndrome, as labeled in a recent, widely publicized opinion piece in the New England Journal of Medicine, is not a new concept, according to one hospitalist pioneer.1

Harlan Krumholz, MD, of the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn., writes in NEJM what others previously have described as “hospitalization-associated disability,” says Mark Williams, MD, MHM, chief of hospital medicine at Northwestern University School of Medicine and principal investigator of SHM’s Project BOOST (www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost).2

Dr. Krumholz found that the majority of 30-day readmissions for elderly patients with heart failure, pneumonia, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are for conditions other than the diagnosis named at discharge. He attributes this phenomenon to hospitalization-related sleep deprivation, malnourishment, pain and discomfort, cognition- and physical function-altering medications, deconditioning from bed rest or inactivity, and the experience of confronting stressful, mentally challenging situations in the hospital.1 Such stressors leave elderly patients with post-hospitalization disabilities comparable to a bad case of jet lag.

For Dr. Williams, the physical deterioration leading to rehospitalizations is better attributed to the underlying serious illness and comorbidities experienced by elderly patients—a kind of high-risk, post-illness syndrome. Prior research also has demonstrated the effects of bed rest for hospitalized elderly patients.

Regardless of the origins, is there anything hospitalists can do about this syndrome? “Absolutely,” Dr. Williams says. “Get elderly, hospitalized patients out of bed as quickly as possible, and be mindful of medications and their effects on elderly patients. But most hospitalists already think about these things when managing elderly patients.”

References

Post-hospital syndrome, as labeled in a recent, widely publicized opinion piece in the New England Journal of Medicine, is not a new concept, according to one hospitalist pioneer.1

Harlan Krumholz, MD, of the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn., writes in NEJM what others previously have described as “hospitalization-associated disability,” says Mark Williams, MD, MHM, chief of hospital medicine at Northwestern University School of Medicine and principal investigator of SHM’s Project BOOST (www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost).2

Dr. Krumholz found that the majority of 30-day readmissions for elderly patients with heart failure, pneumonia, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are for conditions other than the diagnosis named at discharge. He attributes this phenomenon to hospitalization-related sleep deprivation, malnourishment, pain and discomfort, cognition- and physical function-altering medications, deconditioning from bed rest or inactivity, and the experience of confronting stressful, mentally challenging situations in the hospital.1 Such stressors leave elderly patients with post-hospitalization disabilities comparable to a bad case of jet lag.

For Dr. Williams, the physical deterioration leading to rehospitalizations is better attributed to the underlying serious illness and comorbidities experienced by elderly patients—a kind of high-risk, post-illness syndrome. Prior research also has demonstrated the effects of bed rest for hospitalized elderly patients.

Regardless of the origins, is there anything hospitalists can do about this syndrome? “Absolutely,” Dr. Williams says. “Get elderly, hospitalized patients out of bed as quickly as possible, and be mindful of medications and their effects on elderly patients. But most hospitalists already think about these things when managing elderly patients.”

References

Post-hospital syndrome, as labeled in a recent, widely publicized opinion piece in the New England Journal of Medicine, is not a new concept, according to one hospitalist pioneer.1

Harlan Krumholz, MD, of the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn., writes in NEJM what others previously have described as “hospitalization-associated disability,” says Mark Williams, MD, MHM, chief of hospital medicine at Northwestern University School of Medicine and principal investigator of SHM’s Project BOOST (www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost).2

Dr. Krumholz found that the majority of 30-day readmissions for elderly patients with heart failure, pneumonia, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are for conditions other than the diagnosis named at discharge. He attributes this phenomenon to hospitalization-related sleep deprivation, malnourishment, pain and discomfort, cognition- and physical function-altering medications, deconditioning from bed rest or inactivity, and the experience of confronting stressful, mentally challenging situations in the hospital.1 Such stressors leave elderly patients with post-hospitalization disabilities comparable to a bad case of jet lag.

For Dr. Williams, the physical deterioration leading to rehospitalizations is better attributed to the underlying serious illness and comorbidities experienced by elderly patients—a kind of high-risk, post-illness syndrome. Prior research also has demonstrated the effects of bed rest for hospitalized elderly patients.

Regardless of the origins, is there anything hospitalists can do about this syndrome? “Absolutely,” Dr. Williams says. “Get elderly, hospitalized patients out of bed as quickly as possible, and be mindful of medications and their effects on elderly patients. But most hospitalists already think about these things when managing elderly patients.”

References

Southern Hospital Medicine Conference Drives Home the Value of Hospitalists

More than 300 hospitalists and other clinicians recently attended the 13th annual Southern Hospital Medicine Conference in Atlanta. The conference is a joint collaboration between the Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta and Ochsner Health System New Orleans. The meeting site has alternated between the two cities each year since 2005.

The prevailing conference theme in 2012 was “Value and Values in Hospital Medicine,” alluding to the value that hospitalists bring to the medical community and hospitals and the values shared by hospitalists. The conference offered five pre-courses and more than 50 sessions focused on educating hospitalists on current best practices within core topic areas, including clinical care, quality improvement, healthcare information technology, innovative care models, systems of care, and transitions of care. A judged poster competition featured research and clinical vignettes abstracts, with interesting clinical cases as well as new research in hospital medicine.

One of the highlights of this year’s conference was the keynote address delivered by Dr. William A. Bornstein, chief quality and medical officer of Emory Healthcare. Dr. Bornstein discussed the various aspects of quality and cost in hospital care. He described the challenges in defining quality and measuring cost when trying to calculate the “value” equation in medicine (value=quality/cost). He outlined the Institute of Medicine’s previously described STEEEP (safe, timely, effective, efficient, equitable, patient-centered) aims of quality in 2001.

Dr. Bornstein’s own definition for quality is “partnering with patients and families to reliably, 100% of the time, deliver when, where, and how they want it—and with minimal waste—care based on the best available evidence and consistent with patient and family values and preferences.” To measure outcome, he said, we need to address system structure (what’s in place before the patient arrives), process (what we do for the patient), and culture (how we can get the buy-in from all stakeholders). The sum of these factors achieves outcome, which requires risk adjustment and, ideally, long-term follow-up data, he said.

Dr. Bornstein also discussed the need to develop standard processes whereby equivalent clinicians can follow similar processes to achieve the same results. When physicians “do it the same” (i.e. standardized protocols), error rates and cost decrease, he explained.

Dr. Bornstein also focused on transformative solutions to address problems in healthcare as a whole, rather than attempting to fix problems piecemeal.

Jason Stein, MD, SFHM, offered another conference highlight: a pre-conference program and plenary session on an innovative approach to improve hospital outcomes through implementation of the accountable-care unit (ACU). Dr. Stein, director of the clinical research program at Emory School of Medicine, described the current state of hospital care as asynchronous, with various providers caring for the patient without much coordination. For example, the physician sees the patient at 9 a.m., followed by the nurse at 10 a.m., and then finally the visiting family at 11 a.m. The ACU model of care would involve all the providers rounding with the patient and family at a scheduled time daily to provide synchronous care.

Dr. Stein described an ACU as a geographic inpatient area consistently responsible for the clinical, service, and cost outcomes it produces. Features of this unit include:

- Assignment of physicians by units to enhance predictability;

- Cohesiveness and communication;

- Structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds to consistently deliver evidence-based, patient-centered care;

- Evaluation of performance data by unit instead of facility or service line; and

- A dyad partnership involving a nurse unit director and a physician unit medical director.

ACU implementation at Emory has led to decreased mortality, reduced length of stay, and improved patient satisfaction compared to traditional units, according to Dr. Stein. While the ACU might not be suited for all, he said, all hospitals can learn from various components of this innovative approach to deliver better patient care.

The ever-changing state of HM in the U.S. remains a challenge, but it continues to generate innovation and excitement. The high number of engaged participants from 30 different states attending the 13th annual Southern Hospital Medicine Conference demonstrates that hospitalists are eager to learn and ready to improve their practice in order to provide high-value healthcare in U.S. hospitals today.

Dr. Lee is vice chairman in the department of hospital medicine at Ochsner Health System. Dr. Smith is an assistant director for education in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University. Dr. Deitelzweig is system chairman in the department of hospital medicine and medical director for regional business development at Ochsner Health System. Dr. Wang is the division director of hospital medicine at Emory University. Dr. Dressler is director for education in the division of hospital medicine and an associate program director for the J. Willis Hurst Internal Medicine Residency Program at Emory University.

More than 300 hospitalists and other clinicians recently attended the 13th annual Southern Hospital Medicine Conference in Atlanta. The conference is a joint collaboration between the Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta and Ochsner Health System New Orleans. The meeting site has alternated between the two cities each year since 2005.

The prevailing conference theme in 2012 was “Value and Values in Hospital Medicine,” alluding to the value that hospitalists bring to the medical community and hospitals and the values shared by hospitalists. The conference offered five pre-courses and more than 50 sessions focused on educating hospitalists on current best practices within core topic areas, including clinical care, quality improvement, healthcare information technology, innovative care models, systems of care, and transitions of care. A judged poster competition featured research and clinical vignettes abstracts, with interesting clinical cases as well as new research in hospital medicine.

One of the highlights of this year’s conference was the keynote address delivered by Dr. William A. Bornstein, chief quality and medical officer of Emory Healthcare. Dr. Bornstein discussed the various aspects of quality and cost in hospital care. He described the challenges in defining quality and measuring cost when trying to calculate the “value” equation in medicine (value=quality/cost). He outlined the Institute of Medicine’s previously described STEEEP (safe, timely, effective, efficient, equitable, patient-centered) aims of quality in 2001.

Dr. Bornstein’s own definition for quality is “partnering with patients and families to reliably, 100% of the time, deliver when, where, and how they want it—and with minimal waste—care based on the best available evidence and consistent with patient and family values and preferences.” To measure outcome, he said, we need to address system structure (what’s in place before the patient arrives), process (what we do for the patient), and culture (how we can get the buy-in from all stakeholders). The sum of these factors achieves outcome, which requires risk adjustment and, ideally, long-term follow-up data, he said.

Dr. Bornstein also discussed the need to develop standard processes whereby equivalent clinicians can follow similar processes to achieve the same results. When physicians “do it the same” (i.e. standardized protocols), error rates and cost decrease, he explained.

Dr. Bornstein also focused on transformative solutions to address problems in healthcare as a whole, rather than attempting to fix problems piecemeal.

Jason Stein, MD, SFHM, offered another conference highlight: a pre-conference program and plenary session on an innovative approach to improve hospital outcomes through implementation of the accountable-care unit (ACU). Dr. Stein, director of the clinical research program at Emory School of Medicine, described the current state of hospital care as asynchronous, with various providers caring for the patient without much coordination. For example, the physician sees the patient at 9 a.m., followed by the nurse at 10 a.m., and then finally the visiting family at 11 a.m. The ACU model of care would involve all the providers rounding with the patient and family at a scheduled time daily to provide synchronous care.

Dr. Stein described an ACU as a geographic inpatient area consistently responsible for the clinical, service, and cost outcomes it produces. Features of this unit include:

- Assignment of physicians by units to enhance predictability;

- Cohesiveness and communication;

- Structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds to consistently deliver evidence-based, patient-centered care;

- Evaluation of performance data by unit instead of facility or service line; and

- A dyad partnership involving a nurse unit director and a physician unit medical director.

ACU implementation at Emory has led to decreased mortality, reduced length of stay, and improved patient satisfaction compared to traditional units, according to Dr. Stein. While the ACU might not be suited for all, he said, all hospitals can learn from various components of this innovative approach to deliver better patient care.

The ever-changing state of HM in the U.S. remains a challenge, but it continues to generate innovation and excitement. The high number of engaged participants from 30 different states attending the 13th annual Southern Hospital Medicine Conference demonstrates that hospitalists are eager to learn and ready to improve their practice in order to provide high-value healthcare in U.S. hospitals today.

Dr. Lee is vice chairman in the department of hospital medicine at Ochsner Health System. Dr. Smith is an assistant director for education in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University. Dr. Deitelzweig is system chairman in the department of hospital medicine and medical director for regional business development at Ochsner Health System. Dr. Wang is the division director of hospital medicine at Emory University. Dr. Dressler is director for education in the division of hospital medicine and an associate program director for the J. Willis Hurst Internal Medicine Residency Program at Emory University.

More than 300 hospitalists and other clinicians recently attended the 13th annual Southern Hospital Medicine Conference in Atlanta. The conference is a joint collaboration between the Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta and Ochsner Health System New Orleans. The meeting site has alternated between the two cities each year since 2005.

The prevailing conference theme in 2012 was “Value and Values in Hospital Medicine,” alluding to the value that hospitalists bring to the medical community and hospitals and the values shared by hospitalists. The conference offered five pre-courses and more than 50 sessions focused on educating hospitalists on current best practices within core topic areas, including clinical care, quality improvement, healthcare information technology, innovative care models, systems of care, and transitions of care. A judged poster competition featured research and clinical vignettes abstracts, with interesting clinical cases as well as new research in hospital medicine.

One of the highlights of this year’s conference was the keynote address delivered by Dr. William A. Bornstein, chief quality and medical officer of Emory Healthcare. Dr. Bornstein discussed the various aspects of quality and cost in hospital care. He described the challenges in defining quality and measuring cost when trying to calculate the “value” equation in medicine (value=quality/cost). He outlined the Institute of Medicine’s previously described STEEEP (safe, timely, effective, efficient, equitable, patient-centered) aims of quality in 2001.

Dr. Bornstein’s own definition for quality is “partnering with patients and families to reliably, 100% of the time, deliver when, where, and how they want it—and with minimal waste—care based on the best available evidence and consistent with patient and family values and preferences.” To measure outcome, he said, we need to address system structure (what’s in place before the patient arrives), process (what we do for the patient), and culture (how we can get the buy-in from all stakeholders). The sum of these factors achieves outcome, which requires risk adjustment and, ideally, long-term follow-up data, he said.

Dr. Bornstein also discussed the need to develop standard processes whereby equivalent clinicians can follow similar processes to achieve the same results. When physicians “do it the same” (i.e. standardized protocols), error rates and cost decrease, he explained.

Dr. Bornstein also focused on transformative solutions to address problems in healthcare as a whole, rather than attempting to fix problems piecemeal.

Jason Stein, MD, SFHM, offered another conference highlight: a pre-conference program and plenary session on an innovative approach to improve hospital outcomes through implementation of the accountable-care unit (ACU). Dr. Stein, director of the clinical research program at Emory School of Medicine, described the current state of hospital care as asynchronous, with various providers caring for the patient without much coordination. For example, the physician sees the patient at 9 a.m., followed by the nurse at 10 a.m., and then finally the visiting family at 11 a.m. The ACU model of care would involve all the providers rounding with the patient and family at a scheduled time daily to provide synchronous care.

Dr. Stein described an ACU as a geographic inpatient area consistently responsible for the clinical, service, and cost outcomes it produces. Features of this unit include:

- Assignment of physicians by units to enhance predictability;

- Cohesiveness and communication;

- Structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds to consistently deliver evidence-based, patient-centered care;

- Evaluation of performance data by unit instead of facility or service line; and

- A dyad partnership involving a nurse unit director and a physician unit medical director.

ACU implementation at Emory has led to decreased mortality, reduced length of stay, and improved patient satisfaction compared to traditional units, according to Dr. Stein. While the ACU might not be suited for all, he said, all hospitals can learn from various components of this innovative approach to deliver better patient care.

The ever-changing state of HM in the U.S. remains a challenge, but it continues to generate innovation and excitement. The high number of engaged participants from 30 different states attending the 13th annual Southern Hospital Medicine Conference demonstrates that hospitalists are eager to learn and ready to improve their practice in order to provide high-value healthcare in U.S. hospitals today.

Dr. Lee is vice chairman in the department of hospital medicine at Ochsner Health System. Dr. Smith is an assistant director for education in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University. Dr. Deitelzweig is system chairman in the department of hospital medicine and medical director for regional business development at Ochsner Health System. Dr. Wang is the division director of hospital medicine at Emory University. Dr. Dressler is director for education in the division of hospital medicine and an associate program director for the J. Willis Hurst Internal Medicine Residency Program at Emory University.

Win Whitcomb: Mortality Rates Become a Measuring Stick for Hospital Performance

—Blue Oyster Cult

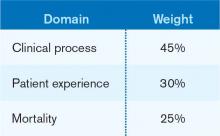

The designers of the hospital value-based purchasing (HVBP) program sought to include outcomes measures in 2014, and when they did, mortality was their choice. Specifically, HVBP for fiscal-year 2014 (starting October 2013) will include 30-day mortality rates for myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia. The weighting for the mortality domain will be 25% (see Table 1).

To review the requirements for the HVBP program in FY2014: All hospitals will have 1.25% of their Medicare inpatient payments withheld. They can earn back none, some, all, or an amount in excess of the 1.25%, depending on performance in the performance domains. To put it in perspective, 1.25% of Medicare inpatient payments for a 320-bed hospital are about $1 million. Such a hospital will have about $250,000 at risk in the mortality domain in FY2014.

Given the role hospitalists play in quality and safety initiatives, and the importance of medical record documentation in defining the risk of mortality and severity of illness, we can be crucial players in how our hospitals perform with regard to mortality.

Focus Areas for Mortality Reduction

Although many hospitalists might think that reducing mortality is like “boiling the ocean,” there are some areas where we can clearly focus our attention. There are four priority areas we should target in the coming years (also see Figure 1):

Reduce harm. This may take the form of reducing hospital-acquired infections, such as catheter-related UTIs, Clostridium difficile, and central-line-associated bloodstream infections, or reducing hospital-acquired VTE, falls, and delirium. Many hospital-acquired conditions have a collection, or bundle, of preventive practices. Hospitalists can work both in an institutional leadership capacity and in the course of daily clinical practice to implement bundles and best practices to reduce patient harm.

Improve teamwork. With hospitalists, “you started to have teams caring for inpatients in a coordinated way. So I regard this as [hospitalists] coming into their own, their vision of the future starting to really take hold,” said Brent James, coauthor of the recent Institute of Medicine report “Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.” Partly, we’ve accomplished this through simply “showing up” and partly we’ve done it through becoming students of the art and science of teamwork. An example of teamwork training, developed by the Defense Department and the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ), is TeamSTEPPS, which offers a systematic approach to cooperation, coordination, and communication among team members. Optimal patient resuscitation, in-hospital handoffs, rapid-response teams, and early-warning systems are essential pieces of teamwork that may reduce mortality.

Improve evidence-based care. This domain covers process measures aimed at optimizing care, including reducing mortality. For HVBP in particular, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia are the focus.

Improve transitions of care. Best practices for care transitions and reducing readmissions, including advance-care planning, involvement of palliative care and hospice, and coordination with post-acute care, can be a key part of reducing 30-day mortality.

Documentation Integrity

Accurately capturing a patient’s condition in the medical record is crucial to assigning severity of illness and risk of mortality. Because mortality rates are severity-adjusted, accurate documentation is another important dimension to potentially improving a hospital’s performance with regard to the mortality domain. This is one more reason to work closely with your hospital’s documentation specialists.

Don’t Be Afraid...

Proponents of mortality as a quality measure point to it as the ultimate reflection of the care provided. While moving the needle might seem like a task too big to undertake, a disciplined approach to the elements of the driver diagram combined with a robust documentation program can provide your institution with a tangible focus on this definitive measure.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

—Blue Oyster Cult

The designers of the hospital value-based purchasing (HVBP) program sought to include outcomes measures in 2014, and when they did, mortality was their choice. Specifically, HVBP for fiscal-year 2014 (starting October 2013) will include 30-day mortality rates for myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia. The weighting for the mortality domain will be 25% (see Table 1).

To review the requirements for the HVBP program in FY2014: All hospitals will have 1.25% of their Medicare inpatient payments withheld. They can earn back none, some, all, or an amount in excess of the 1.25%, depending on performance in the performance domains. To put it in perspective, 1.25% of Medicare inpatient payments for a 320-bed hospital are about $1 million. Such a hospital will have about $250,000 at risk in the mortality domain in FY2014.

Given the role hospitalists play in quality and safety initiatives, and the importance of medical record documentation in defining the risk of mortality and severity of illness, we can be crucial players in how our hospitals perform with regard to mortality.

Focus Areas for Mortality Reduction

Although many hospitalists might think that reducing mortality is like “boiling the ocean,” there are some areas where we can clearly focus our attention. There are four priority areas we should target in the coming years (also see Figure 1):

Reduce harm. This may take the form of reducing hospital-acquired infections, such as catheter-related UTIs, Clostridium difficile, and central-line-associated bloodstream infections, or reducing hospital-acquired VTE, falls, and delirium. Many hospital-acquired conditions have a collection, or bundle, of preventive practices. Hospitalists can work both in an institutional leadership capacity and in the course of daily clinical practice to implement bundles and best practices to reduce patient harm.

Improve teamwork. With hospitalists, “you started to have teams caring for inpatients in a coordinated way. So I regard this as [hospitalists] coming into their own, their vision of the future starting to really take hold,” said Brent James, coauthor of the recent Institute of Medicine report “Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.” Partly, we’ve accomplished this through simply “showing up” and partly we’ve done it through becoming students of the art and science of teamwork. An example of teamwork training, developed by the Defense Department and the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ), is TeamSTEPPS, which offers a systematic approach to cooperation, coordination, and communication among team members. Optimal patient resuscitation, in-hospital handoffs, rapid-response teams, and early-warning systems are essential pieces of teamwork that may reduce mortality.

Improve evidence-based care. This domain covers process measures aimed at optimizing care, including reducing mortality. For HVBP in particular, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia are the focus.

Improve transitions of care. Best practices for care transitions and reducing readmissions, including advance-care planning, involvement of palliative care and hospice, and coordination with post-acute care, can be a key part of reducing 30-day mortality.

Documentation Integrity

Accurately capturing a patient’s condition in the medical record is crucial to assigning severity of illness and risk of mortality. Because mortality rates are severity-adjusted, accurate documentation is another important dimension to potentially improving a hospital’s performance with regard to the mortality domain. This is one more reason to work closely with your hospital’s documentation specialists.

Don’t Be Afraid...

Proponents of mortality as a quality measure point to it as the ultimate reflection of the care provided. While moving the needle might seem like a task too big to undertake, a disciplined approach to the elements of the driver diagram combined with a robust documentation program can provide your institution with a tangible focus on this definitive measure.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

—Blue Oyster Cult

The designers of the hospital value-based purchasing (HVBP) program sought to include outcomes measures in 2014, and when they did, mortality was their choice. Specifically, HVBP for fiscal-year 2014 (starting October 2013) will include 30-day mortality rates for myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia. The weighting for the mortality domain will be 25% (see Table 1).

To review the requirements for the HVBP program in FY2014: All hospitals will have 1.25% of their Medicare inpatient payments withheld. They can earn back none, some, all, or an amount in excess of the 1.25%, depending on performance in the performance domains. To put it in perspective, 1.25% of Medicare inpatient payments for a 320-bed hospital are about $1 million. Such a hospital will have about $250,000 at risk in the mortality domain in FY2014.

Given the role hospitalists play in quality and safety initiatives, and the importance of medical record documentation in defining the risk of mortality and severity of illness, we can be crucial players in how our hospitals perform with regard to mortality.

Focus Areas for Mortality Reduction

Although many hospitalists might think that reducing mortality is like “boiling the ocean,” there are some areas where we can clearly focus our attention. There are four priority areas we should target in the coming years (also see Figure 1):

Reduce harm. This may take the form of reducing hospital-acquired infections, such as catheter-related UTIs, Clostridium difficile, and central-line-associated bloodstream infections, or reducing hospital-acquired VTE, falls, and delirium. Many hospital-acquired conditions have a collection, or bundle, of preventive practices. Hospitalists can work both in an institutional leadership capacity and in the course of daily clinical practice to implement bundles and best practices to reduce patient harm.

Improve teamwork. With hospitalists, “you started to have teams caring for inpatients in a coordinated way. So I regard this as [hospitalists] coming into their own, their vision of the future starting to really take hold,” said Brent James, coauthor of the recent Institute of Medicine report “Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.” Partly, we’ve accomplished this through simply “showing up” and partly we’ve done it through becoming students of the art and science of teamwork. An example of teamwork training, developed by the Defense Department and the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ), is TeamSTEPPS, which offers a systematic approach to cooperation, coordination, and communication among team members. Optimal patient resuscitation, in-hospital handoffs, rapid-response teams, and early-warning systems are essential pieces of teamwork that may reduce mortality.

Improve evidence-based care. This domain covers process measures aimed at optimizing care, including reducing mortality. For HVBP in particular, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia are the focus.

Improve transitions of care. Best practices for care transitions and reducing readmissions, including advance-care planning, involvement of palliative care and hospice, and coordination with post-acute care, can be a key part of reducing 30-day mortality.

Documentation Integrity

Accurately capturing a patient’s condition in the medical record is crucial to assigning severity of illness and risk of mortality. Because mortality rates are severity-adjusted, accurate documentation is another important dimension to potentially improving a hospital’s performance with regard to the mortality domain. This is one more reason to work closely with your hospital’s documentation specialists.

Don’t Be Afraid...

Proponents of mortality as a quality measure point to it as the ultimate reflection of the care provided. While moving the needle might seem like a task too big to undertake, a disciplined approach to the elements of the driver diagram combined with a robust documentation program can provide your institution with a tangible focus on this definitive measure.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

Pharmacist-Hospitalist Collaboration Can Improve Care, Save Money

A healthy collaboration between hospitalists and pharmacists can generate cost savings and promote positive outcomes, such as preventing adverse drug events and improving care transitions, says Jonathan Edwards, PharmD, BCPS, a clinical pharmacy specialist at Huntsville Hospital in Alabama.

At the 2012 national conference of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy in Hollywood, Fla., Edwards presented a poster that detailed the effectiveness of such interdisciplinary collaboration at Huntsville Hospital, where pharmacists and physicians developed six order sets, a collaborative practice, and a patient interaction program from November 2011 to February 2012. During the study period, researchers documented a total cost savings of $9,825 resulting from 156 patient interventions.

Edwards’ collaborative study at Huntsville started with two physicians who had launched a service teaching hospitalists what pharmacists do, and how they could help in their efforts.

“We got together and developed an order set for treating acute alcohol withdrawal. That went well, so we did five more order sets,” Edwards says. “Then we thought: What if pharmacists got more involved by meeting directly with patients in the hospital to optimize their medication management and help them reach their goals for treatment? We now evaluate patients on the hospitalist service in three units.”

For Edwards, key factors that make the hospitalist-pharmacist relationship work include communicating the pharmacist’s availability to help with the hospitalist’s patients, identifying the physician’s openness to help, and clarifying how the physician prefers to be contacted.

Last October, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) and the American Pharmacists Association (APhA) recognized eight care-transitions programs for best practices that improved patient outcomes and reduced hospital readmissions as part of the Medication Management in Care Transitions (MMCT) Project.

“The MMCT project highlights the valuable role pharmacists can play in addressing medication-related problems that can lead to hospital readmissions,” APhA chief executive officer Thomas E. Menighan, BSPharm, MBA, ScD (Hon), FAPhA, said in a news release. “By putting together these best practices, our goal is to provide a model for better coordination of care and better connectivity between pharmacists and healthcare providers in different practice settings that leads to improved patient health.”

Visit our website for more information about maximizing patient care through pharmacist-hospitalist collaboration.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

Articles first published in the Jan. 16, 2013, edition of The Hospitalist eWire.

A healthy collaboration between hospitalists and pharmacists can generate cost savings and promote positive outcomes, such as preventing adverse drug events and improving care transitions, says Jonathan Edwards, PharmD, BCPS, a clinical pharmacy specialist at Huntsville Hospital in Alabama.

At the 2012 national conference of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy in Hollywood, Fla., Edwards presented a poster that detailed the effectiveness of such interdisciplinary collaboration at Huntsville Hospital, where pharmacists and physicians developed six order sets, a collaborative practice, and a patient interaction program from November 2011 to February 2012. During the study period, researchers documented a total cost savings of $9,825 resulting from 156 patient interventions.

Edwards’ collaborative study at Huntsville started with two physicians who had launched a service teaching hospitalists what pharmacists do, and how they could help in their efforts.

“We got together and developed an order set for treating acute alcohol withdrawal. That went well, so we did five more order sets,” Edwards says. “Then we thought: What if pharmacists got more involved by meeting directly with patients in the hospital to optimize their medication management and help them reach their goals for treatment? We now evaluate patients on the hospitalist service in three units.”

For Edwards, key factors that make the hospitalist-pharmacist relationship work include communicating the pharmacist’s availability to help with the hospitalist’s patients, identifying the physician’s openness to help, and clarifying how the physician prefers to be contacted.

Last October, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) and the American Pharmacists Association (APhA) recognized eight care-transitions programs for best practices that improved patient outcomes and reduced hospital readmissions as part of the Medication Management in Care Transitions (MMCT) Project.

“The MMCT project highlights the valuable role pharmacists can play in addressing medication-related problems that can lead to hospital readmissions,” APhA chief executive officer Thomas E. Menighan, BSPharm, MBA, ScD (Hon), FAPhA, said in a news release. “By putting together these best practices, our goal is to provide a model for better coordination of care and better connectivity between pharmacists and healthcare providers in different practice settings that leads to improved patient health.”

Visit our website for more information about maximizing patient care through pharmacist-hospitalist collaboration.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

Articles first published in the Jan. 16, 2013, edition of The Hospitalist eWire.

A healthy collaboration between hospitalists and pharmacists can generate cost savings and promote positive outcomes, such as preventing adverse drug events and improving care transitions, says Jonathan Edwards, PharmD, BCPS, a clinical pharmacy specialist at Huntsville Hospital in Alabama.

At the 2012 national conference of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy in Hollywood, Fla., Edwards presented a poster that detailed the effectiveness of such interdisciplinary collaboration at Huntsville Hospital, where pharmacists and physicians developed six order sets, a collaborative practice, and a patient interaction program from November 2011 to February 2012. During the study period, researchers documented a total cost savings of $9,825 resulting from 156 patient interventions.

Edwards’ collaborative study at Huntsville started with two physicians who had launched a service teaching hospitalists what pharmacists do, and how they could help in their efforts.

“We got together and developed an order set for treating acute alcohol withdrawal. That went well, so we did five more order sets,” Edwards says. “Then we thought: What if pharmacists got more involved by meeting directly with patients in the hospital to optimize their medication management and help them reach their goals for treatment? We now evaluate patients on the hospitalist service in three units.”

For Edwards, key factors that make the hospitalist-pharmacist relationship work include communicating the pharmacist’s availability to help with the hospitalist’s patients, identifying the physician’s openness to help, and clarifying how the physician prefers to be contacted.

Last October, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) and the American Pharmacists Association (APhA) recognized eight care-transitions programs for best practices that improved patient outcomes and reduced hospital readmissions as part of the Medication Management in Care Transitions (MMCT) Project.

“The MMCT project highlights the valuable role pharmacists can play in addressing medication-related problems that can lead to hospital readmissions,” APhA chief executive officer Thomas E. Menighan, BSPharm, MBA, ScD (Hon), FAPhA, said in a news release. “By putting together these best practices, our goal is to provide a model for better coordination of care and better connectivity between pharmacists and healthcare providers in different practice settings that leads to improved patient health.”

Visit our website for more information about maximizing patient care through pharmacist-hospitalist collaboration.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

Articles first published in the Jan. 16, 2013, edition of The Hospitalist eWire.

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: CogentHMG hospitalist explains how hospitalists can prepare for Value-Based Purchasing at hospital, individual level

Click here to listen to Dr. Wright

Click here to listen to Dr. Wright

Click here to listen to Dr. Wright

Quality Improvement Project Helps Hospital Patients Get Needed Prescriptions

A quality-improvement (QI) project to give high-risk patients ready access to prescribed medications at the time of hospital discharge achieved an 86% success rate, according to an abstract poster presented at HM12 in San Diego last April.1

Lead author Elizabeth Le, MD, then a resident at the University of California at San Francisco Medical Center (UCSF) and now a practicing hospitalist at the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Palo Alto, Calif., says the multidisciplinary “brown bag medications” project involved training house staff to recognize patients at risk. Staff meetings and rounds were used to identify appropriate candidates—those with limited mobility or cognitive issues, lacking insurance coverage or financial resources, a history of medication noncompliance, or leaving the hospital against medical advice—as well as those prescribed medications with a greater urgency for administration on schedule, such as anticoagulants or antibiotics.

About one-quarter of patients on the unit where this approach was first tested were found to need the service, which involved faxing prescriptions to an outpatient pharmacy across the street from the hospital for either pick-up by the family or delivery to the patient’s hospital room. For those with financial impediments, hospital social workers and case managers explored other options, including the social work department’s discretionary use fund, to pay for the drugs.

Dr. Le believes the project could be replicated in other facilities that lack access to in-house pharmacy services at discharge. She recommends involving social workers and case managers in the planning.

At UCSF, recent EHR implementation has automated the ordering of medications, but the challenge of recognizing who could benefit from extra help in obtaining their discharge medications remains a critical issue for hospitals trying to bring readmissions under control.

For more information about the brown bag medications program, contact Dr. Le at [email protected].

References

A quality-improvement (QI) project to give high-risk patients ready access to prescribed medications at the time of hospital discharge achieved an 86% success rate, according to an abstract poster presented at HM12 in San Diego last April.1

Lead author Elizabeth Le, MD, then a resident at the University of California at San Francisco Medical Center (UCSF) and now a practicing hospitalist at the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Palo Alto, Calif., says the multidisciplinary “brown bag medications” project involved training house staff to recognize patients at risk. Staff meetings and rounds were used to identify appropriate candidates—those with limited mobility or cognitive issues, lacking insurance coverage or financial resources, a history of medication noncompliance, or leaving the hospital against medical advice—as well as those prescribed medications with a greater urgency for administration on schedule, such as anticoagulants or antibiotics.

About one-quarter of patients on the unit where this approach was first tested were found to need the service, which involved faxing prescriptions to an outpatient pharmacy across the street from the hospital for either pick-up by the family or delivery to the patient’s hospital room. For those with financial impediments, hospital social workers and case managers explored other options, including the social work department’s discretionary use fund, to pay for the drugs.

Dr. Le believes the project could be replicated in other facilities that lack access to in-house pharmacy services at discharge. She recommends involving social workers and case managers in the planning.

At UCSF, recent EHR implementation has automated the ordering of medications, but the challenge of recognizing who could benefit from extra help in obtaining their discharge medications remains a critical issue for hospitals trying to bring readmissions under control.

For more information about the brown bag medications program, contact Dr. Le at [email protected].

References

A quality-improvement (QI) project to give high-risk patients ready access to prescribed medications at the time of hospital discharge achieved an 86% success rate, according to an abstract poster presented at HM12 in San Diego last April.1

Lead author Elizabeth Le, MD, then a resident at the University of California at San Francisco Medical Center (UCSF) and now a practicing hospitalist at the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Palo Alto, Calif., says the multidisciplinary “brown bag medications” project involved training house staff to recognize patients at risk. Staff meetings and rounds were used to identify appropriate candidates—those with limited mobility or cognitive issues, lacking insurance coverage or financial resources, a history of medication noncompliance, or leaving the hospital against medical advice—as well as those prescribed medications with a greater urgency for administration on schedule, such as anticoagulants or antibiotics.

About one-quarter of patients on the unit where this approach was first tested were found to need the service, which involved faxing prescriptions to an outpatient pharmacy across the street from the hospital for either pick-up by the family or delivery to the patient’s hospital room. For those with financial impediments, hospital social workers and case managers explored other options, including the social work department’s discretionary use fund, to pay for the drugs.

Dr. Le believes the project could be replicated in other facilities that lack access to in-house pharmacy services at discharge. She recommends involving social workers and case managers in the planning.

At UCSF, recent EHR implementation has automated the ordering of medications, but the challenge of recognizing who could benefit from extra help in obtaining their discharge medications remains a critical issue for hospitals trying to bring readmissions under control.

For more information about the brown bag medications program, contact Dr. Le at [email protected].

References

Accountability Hits Home for Hospitalists

Russell Cowles III, MD, lead hospitalist at Bergan Mercy Medical Center in Omaha, Neb., recalls the shock on the faces of hospitalists who attended his presentation to SHM’s Nebraska Area chapter meeting last spring. Dr. Cowles and co-presenter Eric Rice, MD, MMM, SFHM, chapter president and assistant medical director of Alegent Creighton Hospital Medicine Services, were introducing their fellow hospitalists to a forthcoming Medicare initiative called the Physician Feedback/Value-Based Payment Modifier (VBPM) program.

“And everyone in the audience was completely stunned,” Dr. Cowles says. “They had never even dreamed that any of this would come down to the physician level.”

They’re not alone.

“Unless you work in administration or you’re leading a group, I don’t think very many people know this exists,” Dr. Cowles says. “Your average practicing physician, I think, has no clue that this measurement is going on behind the scenes.”

Authorized by the Affordable Care Act, the budget-neutral scheme ties future Medicare reimbursements to measures of quality and efficiency, and grades physicians on a curve. The Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), in place since 2007, forms the foundation of the new program, with feedback arriving in the form of a Quality and Resource Use Report (QRUR), a confidential report card sent to providers. The VBPM program then uses those reports as the basis for a financial reward or penalty.

In principle, SHM and hospitalist leaders have supported the concept of quality measurements as a way to hold doctors more accountable and to help the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) take a more proactive role in improving quality of care while containing costs. And, in theory, HM leaders say hospitalists might be better able to adapt to the added responsibility of performance measurement and reporting due to their central role in the like-minded hospital value-based purchasing (VBP) program that began Oct. 1.

“If the expectation is that we will be involved in some of these initiatives and help the hospitals gain revenue, now we can actually see some dollars for those efforts,” says Julia Wright, MD, SFHM, FACP, president of the MidAtlantic Business Unit for Brentwood, Tenn.-based Cogent HMG. But the inverse is also true: If hospitals are going to have dollars at risk for performance, she says, CMS believes physicians should share in that risk as the providers of healthcare.

On that score, Dr. Rice says, hospitalists might have an advantage due to their focus on teamwork and their role in transitioning patients between inpatient and outpatient settings. In fact, he sees the VBPM as an “enormous opportunity” for hospitalists to demonstrate their leadership in helping to shape how organizations and institutions adapt to a quickly evolving healthcare environment.

But first, hospitalists will need to fully engage. In 2010, CMS found that only about 1 in 4 eligible physicians were participating in the voluntary PQRS and earning a reporting bonus of what is now 0.5% of allowable Medicare charges (roughly $800 for the average hospitalist). The stakes will grow when the PQRS transforms into a negative incentive program in 2015, with a 1.5% penalty for doctors who do not meet its reporting requirements. In 2016 and thereafter, the assessed penalty grows to 2% (about $3,200 for the average hospitalist).

“I think the unfolding timeline has really provided the potential for lulling us into complacency and procrastination,” says Patrick Torcson, MD, MMM, FACP, SFHM, director of hospital medicine at St. Tammany Parish Hospital in Covington, La., and chair of SHM’s Performance Measurement and Reporting Committee.

According to CMS, “physician groups can avoid all negative adjustments simply by participating in the PQRS.” Nonparticipants, however, could get hit with a double whammy. With no quality data, CMS would have no way to assess groups’ performances and would automatically deduct an extra 1% of Medicare reimbursements under the VBPM program. For groups of 100 eligible providers or more, that combined PQRS-VBPM penalty could amount to 2.5% in 2015.

PQRS participants have more leeway and a smaller downside. Starting January 2015, eligible provider groups who meet the reporting requirements can choose either to have no adjustments at all or to compete in the VBPM program for a performance-based bonus or a penalty of 1%, based on cost and quality scores. In January 2017, the program is expected to expand to include all providers, whether in individual or group practice.

A Measure of Relevance

Based on the first QRURs, sent out in March 2012 to providers in four pilot states, SHM wrote a letter to CMS that offered a detailed analysis of several additional concerns. The society followed up with a second letter that provided a more expansive critique of the proposed 2013 Physician Fee Schedule.

One worry is whether the physician feedback/VBPM program has included enough performance measures that are relevant to hospitalists. A Public Policy column in The Hospitalist (“Metric Accountability,” November 2012, p. 18) counted only 10 PQRS measures that apply routinely to HM providers out of a list of more than 200. Even those 10 aren’t always applicable.

“I work at a teaching hospital that’s large enough to have a neurology program, so most acute-stroke patients are admitted by the neurologists,” says Gregory Seymann, MD, SFHM, chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of California at San Diego and a member of SHM’s Performance Measurement and Reporting Committee. “Five of the 10 measures are related to stroke patients, but my group rarely admits stroke patients.” That means only five PQRS measures remain relevant to him.

On paper, the issue might be readily resolved by expanding the number of measures to better reflect HM responsibilities—such as four measures proposed by SHM that relate to transitions of care and medication reconciliation.

—Patrick Torcson, MD, MMM, FACP, SFHM, director, hospital medicine, St. Tammany Parish Hospital, Covington, La., chair, SHM’s Performance Measurement and Reporting Committee

Other groups, though, have their own ideas. A letter to CMS signed by 28 patient and healthcare payor groups calls for the elimination of almost two dozen PQRS measures deemed unnecessary, duplicative, or uninformative, and for the addition of nine others that might better assess patient outcomes and quality of care. Jennifer Eames Huff, director of the Consumer-Purchaser Disclosure Project at San Francisco-based Pacific Business Group on Health, one of the letter’s signatories, says some of those potential measures might be more applicable to hospitalists as well.

But therein lies the rub. Although process measures might not always be strong indicators of quality of care, the introduction of outcome measures often makes providers nervous, says Gary Young, JD, PhD, director of the Center for Health Policy and Healthcare Research at Northeastern University in Boston. “Most providers feel that their patients are sicker and more vulnerable to poorer outcomes, and they don’t want to be judged poorly because they have sicker patients,” he says. Reaching an agreement on the best collection of measures may require some intense negotiations, he says.

–Win Whitcomb, MD, MHM, medical director of healthcare quality, Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, Mass.

Fairer Comparisons