User login

Sleep-deprived physicians less empathetic to patient pain?

new research suggests.

In the first of two studies, resident physicians were presented with two hypothetical scenarios involving a patient who complains of pain. They were asked about their likelihood of prescribing pain medication. The test was given to one group of residents who were just starting their day and to another group who were at the end of their night shift after being on call for 26 hours.

Results showed that the night shift residents were less likely than their daytime counterparts to say they would prescribe pain medication to the patients.

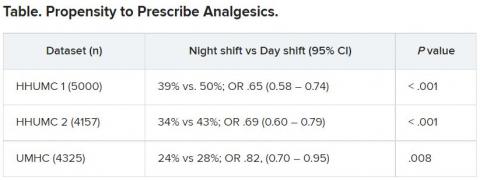

In further analysis of discharge notes from more than 13,000 electronic records of patients presenting with pain complaints at hospitals in Israel and the United States, the likelihood of an analgesic being prescribed during the night shift was 11% lower in Israel and 9% lower in the United States, compared with the day shift.

“Pain management is a major challenge, and a doctor’s perception of a patient’s subjective pain is susceptible to bias,” coinvestigator David Gozal, MD, the Marie M. and Harry L. Smith Endowed Chair of Child Health, University of Missouri–Columbia, said in a press release.

“This study demonstrated that night shift work is an important and previously unrecognized source of bias in pain management, likely stemming from impaired perception of pain,” Dr. Gozal added.

The findings were published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

‘Directional’ differences

Senior investigator Alex Gileles-Hillel, MD, senior pediatric pulmonologist and sleep researcher at Hadassah University Medical Center, Jerusalem, said in an interview that physicians must make “complex assessments of patients’ subjective pain experience” – and the “subjective nature of pain management decisions can give rise to various biases.”

Dr. Gileles-Hillel has previously researched the cognitive toll of night shift work on physicians.

“It’s pretty established, for example, not to drive when sleep deprived because cognition is impaired,” he said. The current study explored whether sleep deprivation could affect areas other than cognition, including emotions and empathy.

The researchers used “two complementary approaches.” First, they administered tests to measure empathy and pain management decisions in 67 resident physicians at Hadassah Medical Centers either following a 26-hour night shift that began at 8:00 a.m. the day before (n = 36) or immediately before starting the workday (n = 31).

There were no significant differences in demographic, sleep, or burnout measures between the two groups, except that night shift physicians had slept less than those in the daytime group (2.93 vs. 5.96 hours).

Participants completed two tasks. In the empathy-for-pain task, they rated their emotional reactions to pictures of individuals in pain. In the empathy accuracy task, they were asked to assess the feelings of videotaped individuals telling emotional stories.

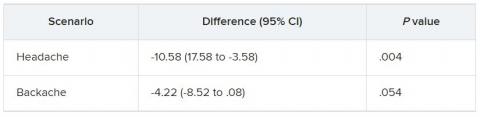

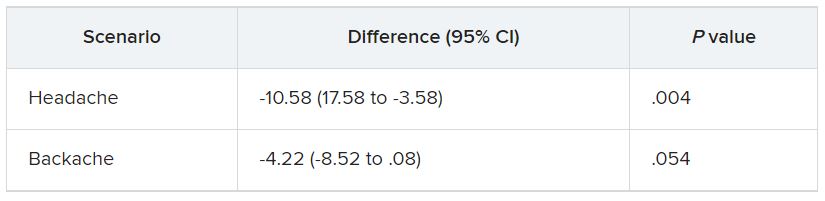

They were then presented with two clinical scenarios: a female patient with a headache and a male patient with a backache. Following that, they were asked to assess the magnitude of the patients’ pain and how likely they would be to prescribe pain medication.

In the empathy-for-pain task, physicians’ empathy scores were significantly lower in the night shift group than in the day group (difference, –0.83; 95% CI, –1.55 to –0.10; P = .026). There were no significant differences between the groups in the empathy accuracy task.

In both scenarios, physicians in the night shift group assessed the patient’s pain as weaker in comparison with physicians in the day group. There was a statistically significant difference in the headache scenario but not the backache scenario.

In the headache scenario, the propensity of the physicians to prescribe analgesics was “directionally lower” but did not reach statistical significance. In the backache scenario, there was no significant difference between the groups’ prescribing propensities.

In both scenarios, pain assessment was positively correlated with the propensity to prescribe analgesics.

Despite the lack of statistical significance, the findings “documented a negative effect of night shift work on physician empathy for pain and a positive association between physician assessment of patient pain and the propensity to prescribe analgesics,” the investigators wrote.

Need for naps?

The researchers then analyzed analgesic prescription patterns drawn from three datasets of discharge notes of patients presenting to the emergency department with pain complaints (n = 13,482) at two branches of Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center and the University of Missouri Health Center.

The researchers collected data, including discharge time, medications patients were prescribed upon discharge, and patients’ subjective pain rating on a scale of 0-10 on a visual analogue scale (VAS).

Although patients’ VAS scores did not differ with respect to time or shift, patients were discharged with significantly less prescribed analgesics during the night shift in comparison with the day shift.

No similar differences in prescriptions between night shifts and day shifts were found for nonanalgesic medications, such as for diabetes or blood pressure. This suggests “the effect was specific to pain,” Dr. Gileles-Hillel said.

The pattern remained significant after controlling for potential confounders, including patient and physician variables and emergency department characteristics.

In addition, patients seen during night shifts received fewer analgesics, particularly opioids, than recommended by the World Health Organization for pain management.

“The first study enabled us to measure empathy for pain directly and examine our hypothesis in a controlled environment, while the second enabled us to test the implications by examining real-life pain management decisions,” Dr. Gileles-Hillel said.

“Physicians need to be aware of this,” he noted. “I try to be aware when I’m taking calls [at night] that I’m less empathetic to others and I might be more brief or angry with others.”

On a “house management level, perhaps institutions should try to schedule naps either before or during overnight call. A nap might give a boost and reboot not only to cognitive but also to emotional resources,” Dr. Gileles-Hillel added.

Compromised safety

In a comment, Eti Ben Simon, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Human Sleep Science, University of California, Berkeley, called the study “an important contribution to a growing list of studies that reveal how long night shifts reduce overall safety” for both patients and clinicians.

“It’s time to abandon the notion that the human brain can function as normal after being deprived of sleep for 24 hours,” said Dr. Ben Simon, who was not involved with the research.

“This is especially true in medicine, where we trust others to take care of us and feel our pain. These functions are simply not possible without adequate sleep,” she added.

Also commenting, Kannan Ramar, MD, president of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, suggested that being cognizant of these findings “may help providers to mitigate this bias” of underprescribing pain medications when treating their patients.

Dr. Ramar, who is also a critical care specialist, pulmonologist, and sleep medicine specialist at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., was not involved with the research.

He noted that “further studies that systematically evaluate this further in a prospective and blinded way will be important.”

The research was supported in part by grants from the Israel Science Foundation, Joy Ventures, the Recanati Fund at the Jerusalem School of Business at the Hebrew University, and a fellowship from the Azrieli Foundation and received grant support to various investigators from the NIH, the Leda J. Sears Foundation, and the University of Missouri. The investigators, Ramar, and Ben Simon have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

In the first of two studies, resident physicians were presented with two hypothetical scenarios involving a patient who complains of pain. They were asked about their likelihood of prescribing pain medication. The test was given to one group of residents who were just starting their day and to another group who were at the end of their night shift after being on call for 26 hours.

Results showed that the night shift residents were less likely than their daytime counterparts to say they would prescribe pain medication to the patients.

In further analysis of discharge notes from more than 13,000 electronic records of patients presenting with pain complaints at hospitals in Israel and the United States, the likelihood of an analgesic being prescribed during the night shift was 11% lower in Israel and 9% lower in the United States, compared with the day shift.

“Pain management is a major challenge, and a doctor’s perception of a patient’s subjective pain is susceptible to bias,” coinvestigator David Gozal, MD, the Marie M. and Harry L. Smith Endowed Chair of Child Health, University of Missouri–Columbia, said in a press release.

“This study demonstrated that night shift work is an important and previously unrecognized source of bias in pain management, likely stemming from impaired perception of pain,” Dr. Gozal added.

The findings were published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

‘Directional’ differences

Senior investigator Alex Gileles-Hillel, MD, senior pediatric pulmonologist and sleep researcher at Hadassah University Medical Center, Jerusalem, said in an interview that physicians must make “complex assessments of patients’ subjective pain experience” – and the “subjective nature of pain management decisions can give rise to various biases.”

Dr. Gileles-Hillel has previously researched the cognitive toll of night shift work on physicians.

“It’s pretty established, for example, not to drive when sleep deprived because cognition is impaired,” he said. The current study explored whether sleep deprivation could affect areas other than cognition, including emotions and empathy.

The researchers used “two complementary approaches.” First, they administered tests to measure empathy and pain management decisions in 67 resident physicians at Hadassah Medical Centers either following a 26-hour night shift that began at 8:00 a.m. the day before (n = 36) or immediately before starting the workday (n = 31).

There were no significant differences in demographic, sleep, or burnout measures between the two groups, except that night shift physicians had slept less than those in the daytime group (2.93 vs. 5.96 hours).

Participants completed two tasks. In the empathy-for-pain task, they rated their emotional reactions to pictures of individuals in pain. In the empathy accuracy task, they were asked to assess the feelings of videotaped individuals telling emotional stories.

They were then presented with two clinical scenarios: a female patient with a headache and a male patient with a backache. Following that, they were asked to assess the magnitude of the patients’ pain and how likely they would be to prescribe pain medication.

In the empathy-for-pain task, physicians’ empathy scores were significantly lower in the night shift group than in the day group (difference, –0.83; 95% CI, –1.55 to –0.10; P = .026). There were no significant differences between the groups in the empathy accuracy task.

In both scenarios, physicians in the night shift group assessed the patient’s pain as weaker in comparison with physicians in the day group. There was a statistically significant difference in the headache scenario but not the backache scenario.

In the headache scenario, the propensity of the physicians to prescribe analgesics was “directionally lower” but did not reach statistical significance. In the backache scenario, there was no significant difference between the groups’ prescribing propensities.

In both scenarios, pain assessment was positively correlated with the propensity to prescribe analgesics.

Despite the lack of statistical significance, the findings “documented a negative effect of night shift work on physician empathy for pain and a positive association between physician assessment of patient pain and the propensity to prescribe analgesics,” the investigators wrote.

Need for naps?

The researchers then analyzed analgesic prescription patterns drawn from three datasets of discharge notes of patients presenting to the emergency department with pain complaints (n = 13,482) at two branches of Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center and the University of Missouri Health Center.

The researchers collected data, including discharge time, medications patients were prescribed upon discharge, and patients’ subjective pain rating on a scale of 0-10 on a visual analogue scale (VAS).

Although patients’ VAS scores did not differ with respect to time or shift, patients were discharged with significantly less prescribed analgesics during the night shift in comparison with the day shift.

No similar differences in prescriptions between night shifts and day shifts were found for nonanalgesic medications, such as for diabetes or blood pressure. This suggests “the effect was specific to pain,” Dr. Gileles-Hillel said.

The pattern remained significant after controlling for potential confounders, including patient and physician variables and emergency department characteristics.

In addition, patients seen during night shifts received fewer analgesics, particularly opioids, than recommended by the World Health Organization for pain management.

“The first study enabled us to measure empathy for pain directly and examine our hypothesis in a controlled environment, while the second enabled us to test the implications by examining real-life pain management decisions,” Dr. Gileles-Hillel said.

“Physicians need to be aware of this,” he noted. “I try to be aware when I’m taking calls [at night] that I’m less empathetic to others and I might be more brief or angry with others.”

On a “house management level, perhaps institutions should try to schedule naps either before or during overnight call. A nap might give a boost and reboot not only to cognitive but also to emotional resources,” Dr. Gileles-Hillel added.

Compromised safety

In a comment, Eti Ben Simon, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Human Sleep Science, University of California, Berkeley, called the study “an important contribution to a growing list of studies that reveal how long night shifts reduce overall safety” for both patients and clinicians.

“It’s time to abandon the notion that the human brain can function as normal after being deprived of sleep for 24 hours,” said Dr. Ben Simon, who was not involved with the research.

“This is especially true in medicine, where we trust others to take care of us and feel our pain. These functions are simply not possible without adequate sleep,” she added.

Also commenting, Kannan Ramar, MD, president of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, suggested that being cognizant of these findings “may help providers to mitigate this bias” of underprescribing pain medications when treating their patients.

Dr. Ramar, who is also a critical care specialist, pulmonologist, and sleep medicine specialist at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., was not involved with the research.

He noted that “further studies that systematically evaluate this further in a prospective and blinded way will be important.”

The research was supported in part by grants from the Israel Science Foundation, Joy Ventures, the Recanati Fund at the Jerusalem School of Business at the Hebrew University, and a fellowship from the Azrieli Foundation and received grant support to various investigators from the NIH, the Leda J. Sears Foundation, and the University of Missouri. The investigators, Ramar, and Ben Simon have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

In the first of two studies, resident physicians were presented with two hypothetical scenarios involving a patient who complains of pain. They were asked about their likelihood of prescribing pain medication. The test was given to one group of residents who were just starting their day and to another group who were at the end of their night shift after being on call for 26 hours.

Results showed that the night shift residents were less likely than their daytime counterparts to say they would prescribe pain medication to the patients.

In further analysis of discharge notes from more than 13,000 electronic records of patients presenting with pain complaints at hospitals in Israel and the United States, the likelihood of an analgesic being prescribed during the night shift was 11% lower in Israel and 9% lower in the United States, compared with the day shift.

“Pain management is a major challenge, and a doctor’s perception of a patient’s subjective pain is susceptible to bias,” coinvestigator David Gozal, MD, the Marie M. and Harry L. Smith Endowed Chair of Child Health, University of Missouri–Columbia, said in a press release.

“This study demonstrated that night shift work is an important and previously unrecognized source of bias in pain management, likely stemming from impaired perception of pain,” Dr. Gozal added.

The findings were published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

‘Directional’ differences

Senior investigator Alex Gileles-Hillel, MD, senior pediatric pulmonologist and sleep researcher at Hadassah University Medical Center, Jerusalem, said in an interview that physicians must make “complex assessments of patients’ subjective pain experience” – and the “subjective nature of pain management decisions can give rise to various biases.”

Dr. Gileles-Hillel has previously researched the cognitive toll of night shift work on physicians.

“It’s pretty established, for example, not to drive when sleep deprived because cognition is impaired,” he said. The current study explored whether sleep deprivation could affect areas other than cognition, including emotions and empathy.

The researchers used “two complementary approaches.” First, they administered tests to measure empathy and pain management decisions in 67 resident physicians at Hadassah Medical Centers either following a 26-hour night shift that began at 8:00 a.m. the day before (n = 36) or immediately before starting the workday (n = 31).

There were no significant differences in demographic, sleep, or burnout measures between the two groups, except that night shift physicians had slept less than those in the daytime group (2.93 vs. 5.96 hours).

Participants completed two tasks. In the empathy-for-pain task, they rated their emotional reactions to pictures of individuals in pain. In the empathy accuracy task, they were asked to assess the feelings of videotaped individuals telling emotional stories.

They were then presented with two clinical scenarios: a female patient with a headache and a male patient with a backache. Following that, they were asked to assess the magnitude of the patients’ pain and how likely they would be to prescribe pain medication.

In the empathy-for-pain task, physicians’ empathy scores were significantly lower in the night shift group than in the day group (difference, –0.83; 95% CI, –1.55 to –0.10; P = .026). There were no significant differences between the groups in the empathy accuracy task.

In both scenarios, physicians in the night shift group assessed the patient’s pain as weaker in comparison with physicians in the day group. There was a statistically significant difference in the headache scenario but not the backache scenario.

In the headache scenario, the propensity of the physicians to prescribe analgesics was “directionally lower” but did not reach statistical significance. In the backache scenario, there was no significant difference between the groups’ prescribing propensities.

In both scenarios, pain assessment was positively correlated with the propensity to prescribe analgesics.

Despite the lack of statistical significance, the findings “documented a negative effect of night shift work on physician empathy for pain and a positive association between physician assessment of patient pain and the propensity to prescribe analgesics,” the investigators wrote.

Need for naps?

The researchers then analyzed analgesic prescription patterns drawn from three datasets of discharge notes of patients presenting to the emergency department with pain complaints (n = 13,482) at two branches of Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center and the University of Missouri Health Center.

The researchers collected data, including discharge time, medications patients were prescribed upon discharge, and patients’ subjective pain rating on a scale of 0-10 on a visual analogue scale (VAS).

Although patients’ VAS scores did not differ with respect to time or shift, patients were discharged with significantly less prescribed analgesics during the night shift in comparison with the day shift.

No similar differences in prescriptions between night shifts and day shifts were found for nonanalgesic medications, such as for diabetes or blood pressure. This suggests “the effect was specific to pain,” Dr. Gileles-Hillel said.

The pattern remained significant after controlling for potential confounders, including patient and physician variables and emergency department characteristics.

In addition, patients seen during night shifts received fewer analgesics, particularly opioids, than recommended by the World Health Organization for pain management.

“The first study enabled us to measure empathy for pain directly and examine our hypothesis in a controlled environment, while the second enabled us to test the implications by examining real-life pain management decisions,” Dr. Gileles-Hillel said.

“Physicians need to be aware of this,” he noted. “I try to be aware when I’m taking calls [at night] that I’m less empathetic to others and I might be more brief or angry with others.”

On a “house management level, perhaps institutions should try to schedule naps either before or during overnight call. A nap might give a boost and reboot not only to cognitive but also to emotional resources,” Dr. Gileles-Hillel added.

Compromised safety

In a comment, Eti Ben Simon, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Human Sleep Science, University of California, Berkeley, called the study “an important contribution to a growing list of studies that reveal how long night shifts reduce overall safety” for both patients and clinicians.

“It’s time to abandon the notion that the human brain can function as normal after being deprived of sleep for 24 hours,” said Dr. Ben Simon, who was not involved with the research.

“This is especially true in medicine, where we trust others to take care of us and feel our pain. These functions are simply not possible without adequate sleep,” she added.

Also commenting, Kannan Ramar, MD, president of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, suggested that being cognizant of these findings “may help providers to mitigate this bias” of underprescribing pain medications when treating their patients.

Dr. Ramar, who is also a critical care specialist, pulmonologist, and sleep medicine specialist at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., was not involved with the research.

He noted that “further studies that systematically evaluate this further in a prospective and blinded way will be important.”

The research was supported in part by grants from the Israel Science Foundation, Joy Ventures, the Recanati Fund at the Jerusalem School of Business at the Hebrew University, and a fellowship from the Azrieli Foundation and received grant support to various investigators from the NIH, the Leda J. Sears Foundation, and the University of Missouri. The investigators, Ramar, and Ben Simon have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES

Water birth may have benefits for healthy women: Meta-analysis suggests

Water immersion during labor and birth significantly reduced use of medications, maternal pain, and postpartum hemorrhage, compared with standard care with no water immersion, based on data from 36 studies including more than 150,000 women.

“Resting and laboring in water can reduce fear, anxiety, and pain perception; it helps optimize the physiology of childbirth through the release of endogenous endorphins and oxytocin,” and data from randomized, controlled trials have shown a reduced need for epidural analgesia with water immersion, Ethel Burns, PhD, of Oxford (England) Brookes University Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, and colleagues wrote.

Although previous studies have not shown an increased risk for adverse events for newborns following water birth, “There is a need to understand which clinical practices, when performed as part of water immersion care, result in the optimum outcomes for mother and newborn,” the researchers said.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis published in BMJ Open, the researchers identified studies published since 2000 that examined maternal or neonatal interventions and/or outcomes when birthing pools were used for labor and/or birth.

The primary objective was to compare intrapartum interventions and outcomes for water immersion during labor with standard care with no water immersion.

Water immersion generally involves the use of a birth pool for relaxation and pain relief in early labor, and some women proceed with immersion through the second stage of labor and delivery. Of the 36 included studies, 31 took place in a hospital setting, 4 in a midwife-led setting, and 1 in a mixed setting. Most of the studies (25) involved women who planned to have/had a water birth, and these studies included 151,742 women. Another seven studies including 1,901 women involved in water immersion for labor only, three studies including 3,688 women involved in water immersion during labor and water birth; the timing of water immersion was unclear in the remaining study of 215 women.

Overall, water immersion significantly reduced the use of epidurals (odds ratio, 0.17), injected opioids (OR, 0.22), and episiotomy (OR, 0.16). Maternal pain and postpartum hemorrhage also were significantly reduced with water immersion (OR, 0.24 and OR, 0.69, respectively).

Maternal satisfaction was significantly increased with water immersion, and the odds of an intact perineum increased as well (OR, 1.95 and OR, 1.48).

The overall odds of cord avulsion increased with water immersion (OR, 1.94), but the absolute risk was low, compared with births without water immersion (4.3 vs. 1.3 per 1,000). No significant differences in other identified neonatal outcomes were observed across the studies.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the inconsistency of reporting on birth setting, care practices, interventions, and outcomes, and the inclusion of only three outcomes for meta-regression analysis, the researchers noted. In addition, only four studies were conducted in midwifery-led settings.

“This is important because birth pool use is most prevalent in midwifery-led settings,” the researchers wrote.” Evidence-based practice of water immersion requires research that reflects the context of care provision.

“We suggest that studies incorporate the following fundamentals to advance the evidence: birth pool description, clearly described maternal and obstetric characteristics, the birth setting, the care model and use of standardized definitions.”

Despite the limitations and need for additional research, the data overall support the potential benefits from water immersion births for healthy women and newborns, the researchers concluded.

A Clinical Report issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics in January 2022 advised against water immersion during the second stage of labor and delivery. According to the report, the potential for neonatal infections from organisms such as Legionella and Pseudomonas species, is low, but does exist, and could result in serious complications.

Education is essential

Increasing numbers of women are seeking home births and water births, Marissa Platner, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview.

“Given the conflicting data and lack of data, it is important to be able to educate birthing mothers based on best available evidence,” said Dr. Platner, who was not involved in the study.

“I was not surprised by the findings, because the adverse outcomes that are of concern, such as neonatal sepsis, were not clearly addressed,” Dr. Platner said. Given that sepsis “is a rare outcome in the population of low-risk individuals, the study may not have been powered to assess for this. The findings of maternal pain and satisfaction being improved with water immersion are well known. ACOG [American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists] has also stated that water immersion during the first stage of labor is safe and can help with pain control.”

On a practical level, “I think clinicians can use this guidance to discuss the potential benefits of water immersion in the first stages of labor, but would caution women regarding the unknown but possible risks of the water birth, given these findings are less clear,” Dr. Platner said.

“I think the findings regarding maternal outcomes are valid and consistent with the AAP/ACOG recommendations in terms of improving maternal pain control; however, more research is needed to determine the safety of the second stage of labor occurring in the water, given the potential for neonatal infection and respiratory distress, which could not be adequately addressed in this study,” Dr. Platner emphasized.

The study was supported by Oxford Brookes University. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Platner had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Water immersion during labor and birth significantly reduced use of medications, maternal pain, and postpartum hemorrhage, compared with standard care with no water immersion, based on data from 36 studies including more than 150,000 women.

“Resting and laboring in water can reduce fear, anxiety, and pain perception; it helps optimize the physiology of childbirth through the release of endogenous endorphins and oxytocin,” and data from randomized, controlled trials have shown a reduced need for epidural analgesia with water immersion, Ethel Burns, PhD, of Oxford (England) Brookes University Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, and colleagues wrote.

Although previous studies have not shown an increased risk for adverse events for newborns following water birth, “There is a need to understand which clinical practices, when performed as part of water immersion care, result in the optimum outcomes for mother and newborn,” the researchers said.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis published in BMJ Open, the researchers identified studies published since 2000 that examined maternal or neonatal interventions and/or outcomes when birthing pools were used for labor and/or birth.

The primary objective was to compare intrapartum interventions and outcomes for water immersion during labor with standard care with no water immersion.

Water immersion generally involves the use of a birth pool for relaxation and pain relief in early labor, and some women proceed with immersion through the second stage of labor and delivery. Of the 36 included studies, 31 took place in a hospital setting, 4 in a midwife-led setting, and 1 in a mixed setting. Most of the studies (25) involved women who planned to have/had a water birth, and these studies included 151,742 women. Another seven studies including 1,901 women involved in water immersion for labor only, three studies including 3,688 women involved in water immersion during labor and water birth; the timing of water immersion was unclear in the remaining study of 215 women.

Overall, water immersion significantly reduced the use of epidurals (odds ratio, 0.17), injected opioids (OR, 0.22), and episiotomy (OR, 0.16). Maternal pain and postpartum hemorrhage also were significantly reduced with water immersion (OR, 0.24 and OR, 0.69, respectively).

Maternal satisfaction was significantly increased with water immersion, and the odds of an intact perineum increased as well (OR, 1.95 and OR, 1.48).

The overall odds of cord avulsion increased with water immersion (OR, 1.94), but the absolute risk was low, compared with births without water immersion (4.3 vs. 1.3 per 1,000). No significant differences in other identified neonatal outcomes were observed across the studies.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the inconsistency of reporting on birth setting, care practices, interventions, and outcomes, and the inclusion of only three outcomes for meta-regression analysis, the researchers noted. In addition, only four studies were conducted in midwifery-led settings.

“This is important because birth pool use is most prevalent in midwifery-led settings,” the researchers wrote.” Evidence-based practice of water immersion requires research that reflects the context of care provision.

“We suggest that studies incorporate the following fundamentals to advance the evidence: birth pool description, clearly described maternal and obstetric characteristics, the birth setting, the care model and use of standardized definitions.”

Despite the limitations and need for additional research, the data overall support the potential benefits from water immersion births for healthy women and newborns, the researchers concluded.

A Clinical Report issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics in January 2022 advised against water immersion during the second stage of labor and delivery. According to the report, the potential for neonatal infections from organisms such as Legionella and Pseudomonas species, is low, but does exist, and could result in serious complications.

Education is essential

Increasing numbers of women are seeking home births and water births, Marissa Platner, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview.

“Given the conflicting data and lack of data, it is important to be able to educate birthing mothers based on best available evidence,” said Dr. Platner, who was not involved in the study.

“I was not surprised by the findings, because the adverse outcomes that are of concern, such as neonatal sepsis, were not clearly addressed,” Dr. Platner said. Given that sepsis “is a rare outcome in the population of low-risk individuals, the study may not have been powered to assess for this. The findings of maternal pain and satisfaction being improved with water immersion are well known. ACOG [American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists] has also stated that water immersion during the first stage of labor is safe and can help with pain control.”

On a practical level, “I think clinicians can use this guidance to discuss the potential benefits of water immersion in the first stages of labor, but would caution women regarding the unknown but possible risks of the water birth, given these findings are less clear,” Dr. Platner said.

“I think the findings regarding maternal outcomes are valid and consistent with the AAP/ACOG recommendations in terms of improving maternal pain control; however, more research is needed to determine the safety of the second stage of labor occurring in the water, given the potential for neonatal infection and respiratory distress, which could not be adequately addressed in this study,” Dr. Platner emphasized.

The study was supported by Oxford Brookes University. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Platner had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Water immersion during labor and birth significantly reduced use of medications, maternal pain, and postpartum hemorrhage, compared with standard care with no water immersion, based on data from 36 studies including more than 150,000 women.

“Resting and laboring in water can reduce fear, anxiety, and pain perception; it helps optimize the physiology of childbirth through the release of endogenous endorphins and oxytocin,” and data from randomized, controlled trials have shown a reduced need for epidural analgesia with water immersion, Ethel Burns, PhD, of Oxford (England) Brookes University Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, and colleagues wrote.

Although previous studies have not shown an increased risk for adverse events for newborns following water birth, “There is a need to understand which clinical practices, when performed as part of water immersion care, result in the optimum outcomes for mother and newborn,” the researchers said.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis published in BMJ Open, the researchers identified studies published since 2000 that examined maternal or neonatal interventions and/or outcomes when birthing pools were used for labor and/or birth.

The primary objective was to compare intrapartum interventions and outcomes for water immersion during labor with standard care with no water immersion.

Water immersion generally involves the use of a birth pool for relaxation and pain relief in early labor, and some women proceed with immersion through the second stage of labor and delivery. Of the 36 included studies, 31 took place in a hospital setting, 4 in a midwife-led setting, and 1 in a mixed setting. Most of the studies (25) involved women who planned to have/had a water birth, and these studies included 151,742 women. Another seven studies including 1,901 women involved in water immersion for labor only, three studies including 3,688 women involved in water immersion during labor and water birth; the timing of water immersion was unclear in the remaining study of 215 women.

Overall, water immersion significantly reduced the use of epidurals (odds ratio, 0.17), injected opioids (OR, 0.22), and episiotomy (OR, 0.16). Maternal pain and postpartum hemorrhage also were significantly reduced with water immersion (OR, 0.24 and OR, 0.69, respectively).

Maternal satisfaction was significantly increased with water immersion, and the odds of an intact perineum increased as well (OR, 1.95 and OR, 1.48).

The overall odds of cord avulsion increased with water immersion (OR, 1.94), but the absolute risk was low, compared with births without water immersion (4.3 vs. 1.3 per 1,000). No significant differences in other identified neonatal outcomes were observed across the studies.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the inconsistency of reporting on birth setting, care practices, interventions, and outcomes, and the inclusion of only three outcomes for meta-regression analysis, the researchers noted. In addition, only four studies were conducted in midwifery-led settings.

“This is important because birth pool use is most prevalent in midwifery-led settings,” the researchers wrote.” Evidence-based practice of water immersion requires research that reflects the context of care provision.

“We suggest that studies incorporate the following fundamentals to advance the evidence: birth pool description, clearly described maternal and obstetric characteristics, the birth setting, the care model and use of standardized definitions.”

Despite the limitations and need for additional research, the data overall support the potential benefits from water immersion births for healthy women and newborns, the researchers concluded.

A Clinical Report issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics in January 2022 advised against water immersion during the second stage of labor and delivery. According to the report, the potential for neonatal infections from organisms such as Legionella and Pseudomonas species, is low, but does exist, and could result in serious complications.

Education is essential

Increasing numbers of women are seeking home births and water births, Marissa Platner, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview.

“Given the conflicting data and lack of data, it is important to be able to educate birthing mothers based on best available evidence,” said Dr. Platner, who was not involved in the study.

“I was not surprised by the findings, because the adverse outcomes that are of concern, such as neonatal sepsis, were not clearly addressed,” Dr. Platner said. Given that sepsis “is a rare outcome in the population of low-risk individuals, the study may not have been powered to assess for this. The findings of maternal pain and satisfaction being improved with water immersion are well known. ACOG [American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists] has also stated that water immersion during the first stage of labor is safe and can help with pain control.”

On a practical level, “I think clinicians can use this guidance to discuss the potential benefits of water immersion in the first stages of labor, but would caution women regarding the unknown but possible risks of the water birth, given these findings are less clear,” Dr. Platner said.

“I think the findings regarding maternal outcomes are valid and consistent with the AAP/ACOG recommendations in terms of improving maternal pain control; however, more research is needed to determine the safety of the second stage of labor occurring in the water, given the potential for neonatal infection and respiratory distress, which could not be adequately addressed in this study,” Dr. Platner emphasized.

The study was supported by Oxford Brookes University. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Platner had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM BMJ OPEN

How to manage cancer pain when patients misuse opioids

Opioids remain a staple in pain management for cancer, but there is little guidance around how to treat patients who have a history of opioid misuse.

Recently,

“There is a tendency to ignore treatment of opioid use disorder in advanced cancer patients because people think: ‘Oh, this person has bigger fish to fry,’ but that’s not a very patient-centric way of looking at things,” senior author Jessica Merlin, MD, PhD, with the University of Pittsburgh, said in a news release.

“We know that opioid use disorder is a really important factor in quality of life, so addressing opioid addiction and prescription opioid misuse in people with advanced cancer is really critical,” Dr. Merlin added.

The study was published online in JAMA Oncology.

To improve care for people with advanced cancer and cancer-related pain, the researchers first assessed how clinicians currently treat patients with opioid complexity.

Using an online Delphi platform, the team invited 120 clinicians with expertise in palliative care, pain management, and addiction medicine to weigh in on three common clinical scenarios – a patient with a recent history of untreated opioid use disorder, a patient taking more opioids than prescribed, and a patient using nonprescribed benzodiazepines.

For a patient with cancer and a recent history of untreated opioid use disorder, regardless of prognosis, the panel deemed it appropriate to begin treatment with buprenorphine/naloxone for pain but inappropriate to refer the patient to a methadone clinic. The panel felt that going to a methadone clinic would be too burdensome for a patient with advanced cancer and not possible for those with limited prognoses.

“This underscores the importance of access to [opioid use disorder] treatment in cancer treatment settings, including non–addiction specialists waivered to prescribe buprenorphine/naloxone and addiction specialists for more complex cases,” the authors wrote.

For a patient with untreated opioid use disorder, the panel deemed split-dose methadone (two to three times daily) appropriate in those with limited prognosis of weeks to months but was uncertain about the suitability of this approach for patients with longer prognoses of a year or longer.

The appropriateness of initiating treatment with a full-agonist opioid was considered uncertain for a patient with limited prognosis and inappropriate for a patient with longer prognosis.

For a patient with cancer pain and no medical history of opioid use disorder but taking more opioids than prescribed, regardless of prognosis, the panel felt it was appropriate to increase monitoring and inappropriate to taper opioids. The panel was not certain about whether to increase opioids based on the patient’s account of what they need or transition to buprenorphine/naloxone.

For a patient with no history of opioid use disorder who was prescribed traditional opioids for pain and had a positive urine drug test for nonprescribed benzodiazepines, regardless of prognosis, the panel felt it was appropriate to continue opioids with close monitoring and inappropriate to taper opioids or transition to buprenorphine/naloxone.

The researchers said that improving education around buprenorphine and cancer pain management in the context of opioid use disorder or misuse is needed.

In a related editorial, two experts noted that the patients considered in this “important article” require considerable time and expertise from an interdisciplinary team.

“It is important that cancer centers establish and fund such teams mainly as a safety measure for these patients and also as a major contribution to the care of all patients with cancer,” wrote Joseph Arthur, MD, and Eduardo Bruera, MD, with the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

In the wider context, Dr. Arthur and Dr. Bruera highlighted how treatments for patients with advanced cancer have evolved over the past 3 decades, yet patients have continued to be given opioids to address cancer-related pain. Developing more sophisticated drugs that relieve pain without significant side effects or addictive properties is imperative.

Dr. Arthur and Dr. Bruera said the study authors “appropriately emphasize the value of delivering compassionate and expert care for these particularly complex cases and the importance of conducting research on the best ways to alleviate the suffering in this rapidly growing patient population.”

This research was supported by Cambia Health Foundation and the National Institute of Nursing Research. Dr. Merlin, Dr. Arthur, and Dr. Bruera reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Opioids remain a staple in pain management for cancer, but there is little guidance around how to treat patients who have a history of opioid misuse.

Recently,

“There is a tendency to ignore treatment of opioid use disorder in advanced cancer patients because people think: ‘Oh, this person has bigger fish to fry,’ but that’s not a very patient-centric way of looking at things,” senior author Jessica Merlin, MD, PhD, with the University of Pittsburgh, said in a news release.

“We know that opioid use disorder is a really important factor in quality of life, so addressing opioid addiction and prescription opioid misuse in people with advanced cancer is really critical,” Dr. Merlin added.

The study was published online in JAMA Oncology.

To improve care for people with advanced cancer and cancer-related pain, the researchers first assessed how clinicians currently treat patients with opioid complexity.

Using an online Delphi platform, the team invited 120 clinicians with expertise in palliative care, pain management, and addiction medicine to weigh in on three common clinical scenarios – a patient with a recent history of untreated opioid use disorder, a patient taking more opioids than prescribed, and a patient using nonprescribed benzodiazepines.

For a patient with cancer and a recent history of untreated opioid use disorder, regardless of prognosis, the panel deemed it appropriate to begin treatment with buprenorphine/naloxone for pain but inappropriate to refer the patient to a methadone clinic. The panel felt that going to a methadone clinic would be too burdensome for a patient with advanced cancer and not possible for those with limited prognoses.

“This underscores the importance of access to [opioid use disorder] treatment in cancer treatment settings, including non–addiction specialists waivered to prescribe buprenorphine/naloxone and addiction specialists for more complex cases,” the authors wrote.

For a patient with untreated opioid use disorder, the panel deemed split-dose methadone (two to three times daily) appropriate in those with limited prognosis of weeks to months but was uncertain about the suitability of this approach for patients with longer prognoses of a year or longer.

The appropriateness of initiating treatment with a full-agonist opioid was considered uncertain for a patient with limited prognosis and inappropriate for a patient with longer prognosis.

For a patient with cancer pain and no medical history of opioid use disorder but taking more opioids than prescribed, regardless of prognosis, the panel felt it was appropriate to increase monitoring and inappropriate to taper opioids. The panel was not certain about whether to increase opioids based on the patient’s account of what they need or transition to buprenorphine/naloxone.

For a patient with no history of opioid use disorder who was prescribed traditional opioids for pain and had a positive urine drug test for nonprescribed benzodiazepines, regardless of prognosis, the panel felt it was appropriate to continue opioids with close monitoring and inappropriate to taper opioids or transition to buprenorphine/naloxone.

The researchers said that improving education around buprenorphine and cancer pain management in the context of opioid use disorder or misuse is needed.

In a related editorial, two experts noted that the patients considered in this “important article” require considerable time and expertise from an interdisciplinary team.

“It is important that cancer centers establish and fund such teams mainly as a safety measure for these patients and also as a major contribution to the care of all patients with cancer,” wrote Joseph Arthur, MD, and Eduardo Bruera, MD, with the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

In the wider context, Dr. Arthur and Dr. Bruera highlighted how treatments for patients with advanced cancer have evolved over the past 3 decades, yet patients have continued to be given opioids to address cancer-related pain. Developing more sophisticated drugs that relieve pain without significant side effects or addictive properties is imperative.

Dr. Arthur and Dr. Bruera said the study authors “appropriately emphasize the value of delivering compassionate and expert care for these particularly complex cases and the importance of conducting research on the best ways to alleviate the suffering in this rapidly growing patient population.”

This research was supported by Cambia Health Foundation and the National Institute of Nursing Research. Dr. Merlin, Dr. Arthur, and Dr. Bruera reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Opioids remain a staple in pain management for cancer, but there is little guidance around how to treat patients who have a history of opioid misuse.

Recently,

“There is a tendency to ignore treatment of opioid use disorder in advanced cancer patients because people think: ‘Oh, this person has bigger fish to fry,’ but that’s not a very patient-centric way of looking at things,” senior author Jessica Merlin, MD, PhD, with the University of Pittsburgh, said in a news release.

“We know that opioid use disorder is a really important factor in quality of life, so addressing opioid addiction and prescription opioid misuse in people with advanced cancer is really critical,” Dr. Merlin added.

The study was published online in JAMA Oncology.

To improve care for people with advanced cancer and cancer-related pain, the researchers first assessed how clinicians currently treat patients with opioid complexity.

Using an online Delphi platform, the team invited 120 clinicians with expertise in palliative care, pain management, and addiction medicine to weigh in on three common clinical scenarios – a patient with a recent history of untreated opioid use disorder, a patient taking more opioids than prescribed, and a patient using nonprescribed benzodiazepines.

For a patient with cancer and a recent history of untreated opioid use disorder, regardless of prognosis, the panel deemed it appropriate to begin treatment with buprenorphine/naloxone for pain but inappropriate to refer the patient to a methadone clinic. The panel felt that going to a methadone clinic would be too burdensome for a patient with advanced cancer and not possible for those with limited prognoses.

“This underscores the importance of access to [opioid use disorder] treatment in cancer treatment settings, including non–addiction specialists waivered to prescribe buprenorphine/naloxone and addiction specialists for more complex cases,” the authors wrote.

For a patient with untreated opioid use disorder, the panel deemed split-dose methadone (two to three times daily) appropriate in those with limited prognosis of weeks to months but was uncertain about the suitability of this approach for patients with longer prognoses of a year or longer.

The appropriateness of initiating treatment with a full-agonist opioid was considered uncertain for a patient with limited prognosis and inappropriate for a patient with longer prognosis.

For a patient with cancer pain and no medical history of opioid use disorder but taking more opioids than prescribed, regardless of prognosis, the panel felt it was appropriate to increase monitoring and inappropriate to taper opioids. The panel was not certain about whether to increase opioids based on the patient’s account of what they need or transition to buprenorphine/naloxone.

For a patient with no history of opioid use disorder who was prescribed traditional opioids for pain and had a positive urine drug test for nonprescribed benzodiazepines, regardless of prognosis, the panel felt it was appropriate to continue opioids with close monitoring and inappropriate to taper opioids or transition to buprenorphine/naloxone.

The researchers said that improving education around buprenorphine and cancer pain management in the context of opioid use disorder or misuse is needed.

In a related editorial, two experts noted that the patients considered in this “important article” require considerable time and expertise from an interdisciplinary team.

“It is important that cancer centers establish and fund such teams mainly as a safety measure for these patients and also as a major contribution to the care of all patients with cancer,” wrote Joseph Arthur, MD, and Eduardo Bruera, MD, with the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

In the wider context, Dr. Arthur and Dr. Bruera highlighted how treatments for patients with advanced cancer have evolved over the past 3 decades, yet patients have continued to be given opioids to address cancer-related pain. Developing more sophisticated drugs that relieve pain without significant side effects or addictive properties is imperative.

Dr. Arthur and Dr. Bruera said the study authors “appropriately emphasize the value of delivering compassionate and expert care for these particularly complex cases and the importance of conducting research on the best ways to alleviate the suffering in this rapidly growing patient population.”

This research was supported by Cambia Health Foundation and the National Institute of Nursing Research. Dr. Merlin, Dr. Arthur, and Dr. Bruera reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Will the headache field embrace rofecoxib?

In June, the Concord, Mass.–based company Tremeau Pharmaceuticals announced that the Food and Drug Administration was letting it proceed with a phase 3 clinical trial to test rofecoxib, the once-bestselling painkiller known as Vioxx, in patients with migraine.

The anti-inflammatory drug, a cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitor, received its first FDA approval in 1999 and became widely prescribed for arthritis and acute pain. In 2004 it was withdrawn by its manufacturer, Merck, after being shown to raise the risk of cardiovascular events.

In clinical trials and in real-world epidemiological studies, rofecoxib was associated with elevated heart attack, stroke, and related deaths; one 2005 study estimated that it had been responsible for some 38,000 excess deaths in the United States before being withdrawn. In 2007 Merck, beset with allegations that it had suppressed and mischaracterized rofecoxib’s safety data, paid out nearly $5 billion to settle thousands of lawsuits filed by patients and their families.

, an indication for which it received an orphan drug designation in 2017 and the agency’s green light for trials in 2020.

Brad Sippy, Tremeau’s chief executive officer, said that his company chose the two indications in part because both patient populations have low cardiovascular risk. Migraine patients are generally younger than the arthritis populations formerly treated with rofecoxib and are unlikely to take the drug for more than a day or 2 at time, avoiding the risks associated with extended exposure.

A crowded market

The past several years have seen the emergence of a cornucopia of new migraine treatments, including monoclonal antibodies such as erenumab (Aimovig, Amgen), which help prevent attacks by blocking the vasodilator calcitonin gene-related peptide, or CGRP. In addition to the standard arsenal of triptans and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for acute pain relief, migraine patients can now choose among serotonin-blocking agents such as lasmiditan (Reyvow, Eli Lilly), known as “ditans,” and small-molecule CGRP antagonists such as ubrogepant (Ubrelvy, Abbie), known as “gepants.” Some NSAIDs, including one COX inhibitor, have been formulated into rapidly absorbed powders or liquids for migraine.

Mr. Sippy said he sees a role for rofecoxib even in this crowded space. “Migraine as you know is a multimodal situation – few people say that only one drug works for them,” he said. “We think this is an option that would basically be like a high dose of ibuprofen,” but with less frequent dosing and lower gastrointestinal and platelet effects compared with ibuprofen and other NSAIDs.

An improved formulation

Rofecoxib “crosses the blood brain barrier very readily – better than other COX inhibitors on the market,” Mr. Sippy added. “It was well absorbed in its original formulation, and our product is even better absorbed than the original – we estimate it’s probably an hour quicker to [peak concentration].” In addition, he said, “our formulation is more efficient at delivering the drug so we don’t need as much active ingredient – our 17.5 milligrams gets you the same systemic exposure as 25 milligrams of the old product.”

A different mechanism of action

Neurologist Alan M. Rapoport, MD, editor-in-chief of Neurology Reviews and professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, said that he was “cautiously optimistic” that “if used correctly and not too frequently, [rofecoxib] will find its niche in migraine treatment.”

“Patients liked Vioxx,” said Dr. Rapoport, past president of the International Headache Society. Even people currently on prevention “need to have an acute care drug handy.” While some patients on monoclonal antibodies have had success with gepants for acute care, “these both target the same pathway. It’s always nice to have options with a different mechanism of action.”

One of the arguments Tremeau has cited for reintroducing rofecoxib has been an urgent need for alternatives to opioid painkillers. Indeed some analysts have linked the demise of Vioxx with a subsequent increase in opioid prescribing.

Dr. Rapoport noted that he never prescribes opioids or butalbital, a barbiturate, for migraine, and that most headache specialists avoid them in clinical practice. But in the emergency setting, he said, patients receive them all too frequently.

Mr. Sippy said that opioid prescribing, while not unknown in migraine, was a bigger problem in hemophilic arthropathy, the first indication his company has pursued for rofecoxib. People with hemophilia “have a kind of arthritis that would respond well to an anti-inflammatory drug but they can’t take NSAIDs due to bleeding risk. This is why so many end up on opioids. Rofecoxib, as a COX-2 inhibitor, doesn’t have any effect on platelet aggregation, which would make it another option.”

No unique risks at prescribed doses

The migraine indication originally started out narrower: Patients with both migraine and bleeding disorders. “But in talking with the FDA, they encouraged us to develop it for migraine,” Mr. Sippy said. The company is considering pursuing a third indication: menstrual pain co-occurring with migraine. Tremeau has not ruled out seeking an indication in patients with arthritis who cannot take other painkillers, whether opioids or NSAIDs.

Five years ago, when Tremeau first announced its plans to bring rofecoxib back – indeed the company was set up for that purpose and has only this and another COX-2 inhibitor in development – some experts warned that there is little to prevent the drug from being used off-label, whether in higher doses or for other diseases.

“That’s something else we’re seeking to solve in addition to going for younger populations,” said Mr. Sippy, who worked at Merck during the Vioxx crisis and later headed neurology at Sunovion before starting his own company.

“We’re going for the former middle dose as our high dose and now we know that you don’t want to take more than the prescribed amount. If it doesn’t work you get off it; you don’t want to dose-creep on it. That’s been a key insight: At the appropriate dose, this product has no unique risk relative to the drug class and potentially some unique benefits,” he said.

Risk versus benefit

Joseph Ross, MD, a health policy researcher at Yale University in New Haven, Conn., who in a 2018 editorial expressed concerns about rofecoxib’s revival, said in an email that he felt its use in migraine could be justified, with caveats.

During Vioxx’s original approval and time on the market, “there was a cardiovascular risk associated with use that was not being transparently and clearly reported to patients and clinicians,” Dr. Ross said.

“In terms of testing the product for use in patients with migraine – a population of generally younger patients at lower risk of cardiovascular disease – my only concern is that the risk is clearly communicated and that there is adequate postmarket safety surveillance,” he said. “If patients are making fully informed decisions, the potential benefit of the drug with respect to pain control may be worth the risks.”

Dr. Rapoport serves as an adviser for AbbVie, Amgen, Biohaven, Cala Health, Collegium Pharmaceutical, Satsuma, Teva, Theranica and Xoc; he is on the speakers bureau of AbbVie, Amgen, Biohaven, Impel, Lundbeck, and Teva. Dr. Ross disclosed research support from Johnson and Johnson, the Medical Device Innovation Consortium, and the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, along with government grants; he is also an expert witness in a lawsuit against Biogen.

In June, the Concord, Mass.–based company Tremeau Pharmaceuticals announced that the Food and Drug Administration was letting it proceed with a phase 3 clinical trial to test rofecoxib, the once-bestselling painkiller known as Vioxx, in patients with migraine.

The anti-inflammatory drug, a cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitor, received its first FDA approval in 1999 and became widely prescribed for arthritis and acute pain. In 2004 it was withdrawn by its manufacturer, Merck, after being shown to raise the risk of cardiovascular events.

In clinical trials and in real-world epidemiological studies, rofecoxib was associated with elevated heart attack, stroke, and related deaths; one 2005 study estimated that it had been responsible for some 38,000 excess deaths in the United States before being withdrawn. In 2007 Merck, beset with allegations that it had suppressed and mischaracterized rofecoxib’s safety data, paid out nearly $5 billion to settle thousands of lawsuits filed by patients and their families.

, an indication for which it received an orphan drug designation in 2017 and the agency’s green light for trials in 2020.

Brad Sippy, Tremeau’s chief executive officer, said that his company chose the two indications in part because both patient populations have low cardiovascular risk. Migraine patients are generally younger than the arthritis populations formerly treated with rofecoxib and are unlikely to take the drug for more than a day or 2 at time, avoiding the risks associated with extended exposure.

A crowded market

The past several years have seen the emergence of a cornucopia of new migraine treatments, including monoclonal antibodies such as erenumab (Aimovig, Amgen), which help prevent attacks by blocking the vasodilator calcitonin gene-related peptide, or CGRP. In addition to the standard arsenal of triptans and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for acute pain relief, migraine patients can now choose among serotonin-blocking agents such as lasmiditan (Reyvow, Eli Lilly), known as “ditans,” and small-molecule CGRP antagonists such as ubrogepant (Ubrelvy, Abbie), known as “gepants.” Some NSAIDs, including one COX inhibitor, have been formulated into rapidly absorbed powders or liquids for migraine.

Mr. Sippy said he sees a role for rofecoxib even in this crowded space. “Migraine as you know is a multimodal situation – few people say that only one drug works for them,” he said. “We think this is an option that would basically be like a high dose of ibuprofen,” but with less frequent dosing and lower gastrointestinal and platelet effects compared with ibuprofen and other NSAIDs.

An improved formulation

Rofecoxib “crosses the blood brain barrier very readily – better than other COX inhibitors on the market,” Mr. Sippy added. “It was well absorbed in its original formulation, and our product is even better absorbed than the original – we estimate it’s probably an hour quicker to [peak concentration].” In addition, he said, “our formulation is more efficient at delivering the drug so we don’t need as much active ingredient – our 17.5 milligrams gets you the same systemic exposure as 25 milligrams of the old product.”

A different mechanism of action

Neurologist Alan M. Rapoport, MD, editor-in-chief of Neurology Reviews and professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, said that he was “cautiously optimistic” that “if used correctly and not too frequently, [rofecoxib] will find its niche in migraine treatment.”

“Patients liked Vioxx,” said Dr. Rapoport, past president of the International Headache Society. Even people currently on prevention “need to have an acute care drug handy.” While some patients on monoclonal antibodies have had success with gepants for acute care, “these both target the same pathway. It’s always nice to have options with a different mechanism of action.”

One of the arguments Tremeau has cited for reintroducing rofecoxib has been an urgent need for alternatives to opioid painkillers. Indeed some analysts have linked the demise of Vioxx with a subsequent increase in opioid prescribing.

Dr. Rapoport noted that he never prescribes opioids or butalbital, a barbiturate, for migraine, and that most headache specialists avoid them in clinical practice. But in the emergency setting, he said, patients receive them all too frequently.

Mr. Sippy said that opioid prescribing, while not unknown in migraine, was a bigger problem in hemophilic arthropathy, the first indication his company has pursued for rofecoxib. People with hemophilia “have a kind of arthritis that would respond well to an anti-inflammatory drug but they can’t take NSAIDs due to bleeding risk. This is why so many end up on opioids. Rofecoxib, as a COX-2 inhibitor, doesn’t have any effect on platelet aggregation, which would make it another option.”

No unique risks at prescribed doses

The migraine indication originally started out narrower: Patients with both migraine and bleeding disorders. “But in talking with the FDA, they encouraged us to develop it for migraine,” Mr. Sippy said. The company is considering pursuing a third indication: menstrual pain co-occurring with migraine. Tremeau has not ruled out seeking an indication in patients with arthritis who cannot take other painkillers, whether opioids or NSAIDs.

Five years ago, when Tremeau first announced its plans to bring rofecoxib back – indeed the company was set up for that purpose and has only this and another COX-2 inhibitor in development – some experts warned that there is little to prevent the drug from being used off-label, whether in higher doses or for other diseases.

“That’s something else we’re seeking to solve in addition to going for younger populations,” said Mr. Sippy, who worked at Merck during the Vioxx crisis and later headed neurology at Sunovion before starting his own company.

“We’re going for the former middle dose as our high dose and now we know that you don’t want to take more than the prescribed amount. If it doesn’t work you get off it; you don’t want to dose-creep on it. That’s been a key insight: At the appropriate dose, this product has no unique risk relative to the drug class and potentially some unique benefits,” he said.

Risk versus benefit

Joseph Ross, MD, a health policy researcher at Yale University in New Haven, Conn., who in a 2018 editorial expressed concerns about rofecoxib’s revival, said in an email that he felt its use in migraine could be justified, with caveats.

During Vioxx’s original approval and time on the market, “there was a cardiovascular risk associated with use that was not being transparently and clearly reported to patients and clinicians,” Dr. Ross said.

“In terms of testing the product for use in patients with migraine – a population of generally younger patients at lower risk of cardiovascular disease – my only concern is that the risk is clearly communicated and that there is adequate postmarket safety surveillance,” he said. “If patients are making fully informed decisions, the potential benefit of the drug with respect to pain control may be worth the risks.”

Dr. Rapoport serves as an adviser for AbbVie, Amgen, Biohaven, Cala Health, Collegium Pharmaceutical, Satsuma, Teva, Theranica and Xoc; he is on the speakers bureau of AbbVie, Amgen, Biohaven, Impel, Lundbeck, and Teva. Dr. Ross disclosed research support from Johnson and Johnson, the Medical Device Innovation Consortium, and the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, along with government grants; he is also an expert witness in a lawsuit against Biogen.

In June, the Concord, Mass.–based company Tremeau Pharmaceuticals announced that the Food and Drug Administration was letting it proceed with a phase 3 clinical trial to test rofecoxib, the once-bestselling painkiller known as Vioxx, in patients with migraine.

The anti-inflammatory drug, a cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitor, received its first FDA approval in 1999 and became widely prescribed for arthritis and acute pain. In 2004 it was withdrawn by its manufacturer, Merck, after being shown to raise the risk of cardiovascular events.

In clinical trials and in real-world epidemiological studies, rofecoxib was associated with elevated heart attack, stroke, and related deaths; one 2005 study estimated that it had been responsible for some 38,000 excess deaths in the United States before being withdrawn. In 2007 Merck, beset with allegations that it had suppressed and mischaracterized rofecoxib’s safety data, paid out nearly $5 billion to settle thousands of lawsuits filed by patients and their families.

, an indication for which it received an orphan drug designation in 2017 and the agency’s green light for trials in 2020.

Brad Sippy, Tremeau’s chief executive officer, said that his company chose the two indications in part because both patient populations have low cardiovascular risk. Migraine patients are generally younger than the arthritis populations formerly treated with rofecoxib and are unlikely to take the drug for more than a day or 2 at time, avoiding the risks associated with extended exposure.

A crowded market

The past several years have seen the emergence of a cornucopia of new migraine treatments, including monoclonal antibodies such as erenumab (Aimovig, Amgen), which help prevent attacks by blocking the vasodilator calcitonin gene-related peptide, or CGRP. In addition to the standard arsenal of triptans and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for acute pain relief, migraine patients can now choose among serotonin-blocking agents such as lasmiditan (Reyvow, Eli Lilly), known as “ditans,” and small-molecule CGRP antagonists such as ubrogepant (Ubrelvy, Abbie), known as “gepants.” Some NSAIDs, including one COX inhibitor, have been formulated into rapidly absorbed powders or liquids for migraine.

Mr. Sippy said he sees a role for rofecoxib even in this crowded space. “Migraine as you know is a multimodal situation – few people say that only one drug works for them,” he said. “We think this is an option that would basically be like a high dose of ibuprofen,” but with less frequent dosing and lower gastrointestinal and platelet effects compared with ibuprofen and other NSAIDs.

An improved formulation

Rofecoxib “crosses the blood brain barrier very readily – better than other COX inhibitors on the market,” Mr. Sippy added. “It was well absorbed in its original formulation, and our product is even better absorbed than the original – we estimate it’s probably an hour quicker to [peak concentration].” In addition, he said, “our formulation is more efficient at delivering the drug so we don’t need as much active ingredient – our 17.5 milligrams gets you the same systemic exposure as 25 milligrams of the old product.”

A different mechanism of action

Neurologist Alan M. Rapoport, MD, editor-in-chief of Neurology Reviews and professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, said that he was “cautiously optimistic” that “if used correctly and not too frequently, [rofecoxib] will find its niche in migraine treatment.”

“Patients liked Vioxx,” said Dr. Rapoport, past president of the International Headache Society. Even people currently on prevention “need to have an acute care drug handy.” While some patients on monoclonal antibodies have had success with gepants for acute care, “these both target the same pathway. It’s always nice to have options with a different mechanism of action.”

One of the arguments Tremeau has cited for reintroducing rofecoxib has been an urgent need for alternatives to opioid painkillers. Indeed some analysts have linked the demise of Vioxx with a subsequent increase in opioid prescribing.

Dr. Rapoport noted that he never prescribes opioids or butalbital, a barbiturate, for migraine, and that most headache specialists avoid them in clinical practice. But in the emergency setting, he said, patients receive them all too frequently.

Mr. Sippy said that opioid prescribing, while not unknown in migraine, was a bigger problem in hemophilic arthropathy, the first indication his company has pursued for rofecoxib. People with hemophilia “have a kind of arthritis that would respond well to an anti-inflammatory drug but they can’t take NSAIDs due to bleeding risk. This is why so many end up on opioids. Rofecoxib, as a COX-2 inhibitor, doesn’t have any effect on platelet aggregation, which would make it another option.”

No unique risks at prescribed doses

The migraine indication originally started out narrower: Patients with both migraine and bleeding disorders. “But in talking with the FDA, they encouraged us to develop it for migraine,” Mr. Sippy said. The company is considering pursuing a third indication: menstrual pain co-occurring with migraine. Tremeau has not ruled out seeking an indication in patients with arthritis who cannot take other painkillers, whether opioids or NSAIDs.

Five years ago, when Tremeau first announced its plans to bring rofecoxib back – indeed the company was set up for that purpose and has only this and another COX-2 inhibitor in development – some experts warned that there is little to prevent the drug from being used off-label, whether in higher doses or for other diseases.

“That’s something else we’re seeking to solve in addition to going for younger populations,” said Mr. Sippy, who worked at Merck during the Vioxx crisis and later headed neurology at Sunovion before starting his own company.

“We’re going for the former middle dose as our high dose and now we know that you don’t want to take more than the prescribed amount. If it doesn’t work you get off it; you don’t want to dose-creep on it. That’s been a key insight: At the appropriate dose, this product has no unique risk relative to the drug class and potentially some unique benefits,” he said.

Risk versus benefit

Joseph Ross, MD, a health policy researcher at Yale University in New Haven, Conn., who in a 2018 editorial expressed concerns about rofecoxib’s revival, said in an email that he felt its use in migraine could be justified, with caveats.

During Vioxx’s original approval and time on the market, “there was a cardiovascular risk associated with use that was not being transparently and clearly reported to patients and clinicians,” Dr. Ross said.