User login

A new and completely different pain medicine

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

When you stub your toe or get a paper cut on your finger, you feel the pain in that part of your body. It feels like the pain is coming from that place. But, of course, that’s not really what is happening. Pain doesn’t really happen in your toe or your finger. It happens in your brain.

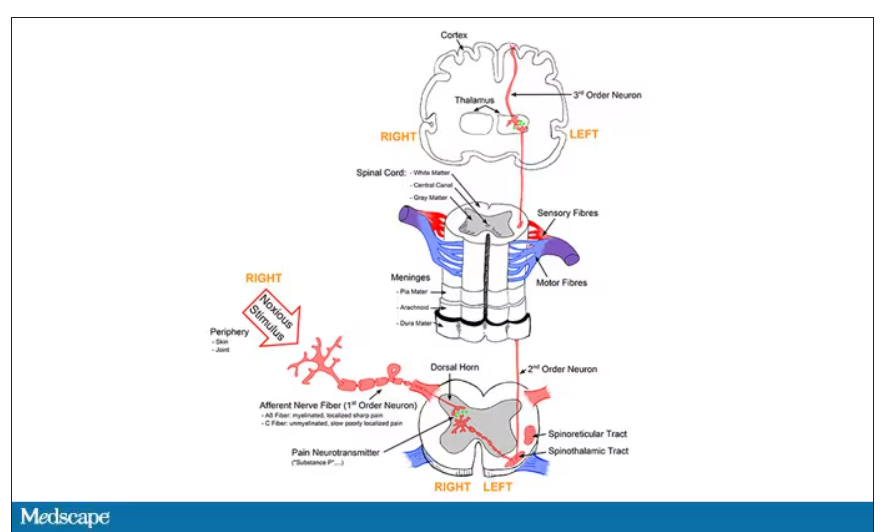

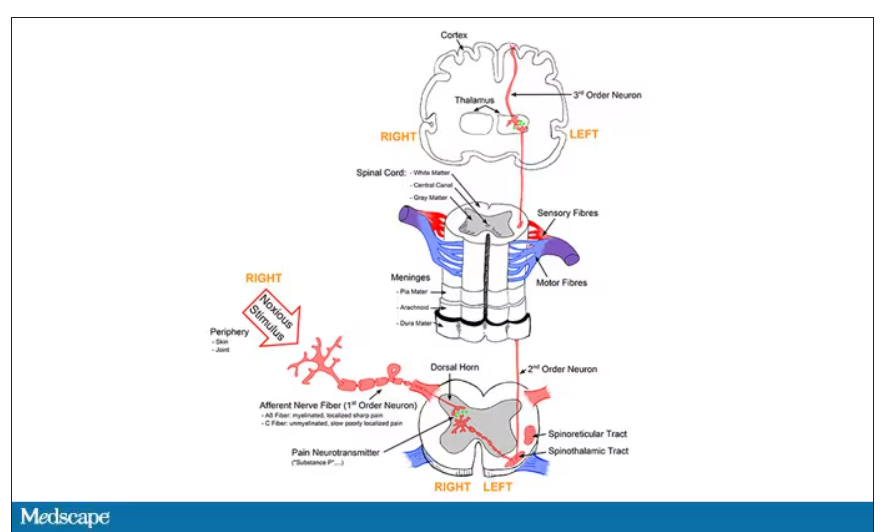

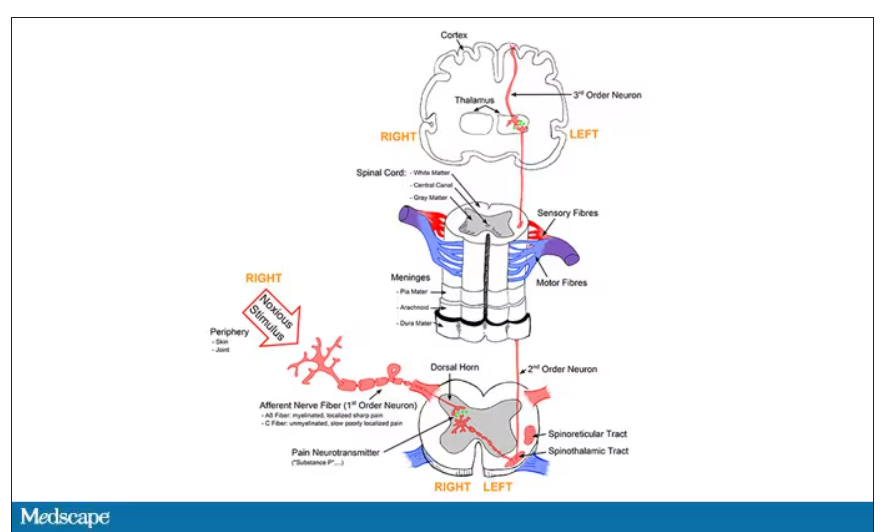

It’s a game of telephone, really. The afferent nerve fiber detects the noxious stimulus, passing that signal to the second-order neuron in the dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord, which runs it up to the thalamus to be passed to the third-order neuron which brings it to the cortex for localization and conscious perception. It’s not even a very good game of telephone. It takes about 100 ms for a pain signal to get from the hand to the brain – longer from the feet, given the greater distance. You see your foot hit the corner of the coffee table and have just enough time to think: “Oh no!” before the pain hits.

Given the Rube Goldberg nature of the process, it would seem like there are any number of places we could stop pain sensation. And sure, local anesthetics at the site of injury, or even spinal anesthetics, are powerful – if temporary and hard to administer – solutions to acute pain.

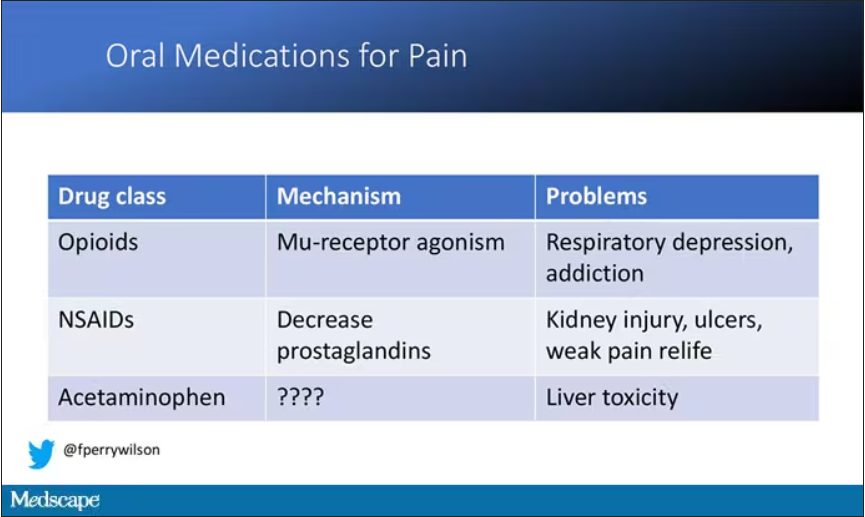

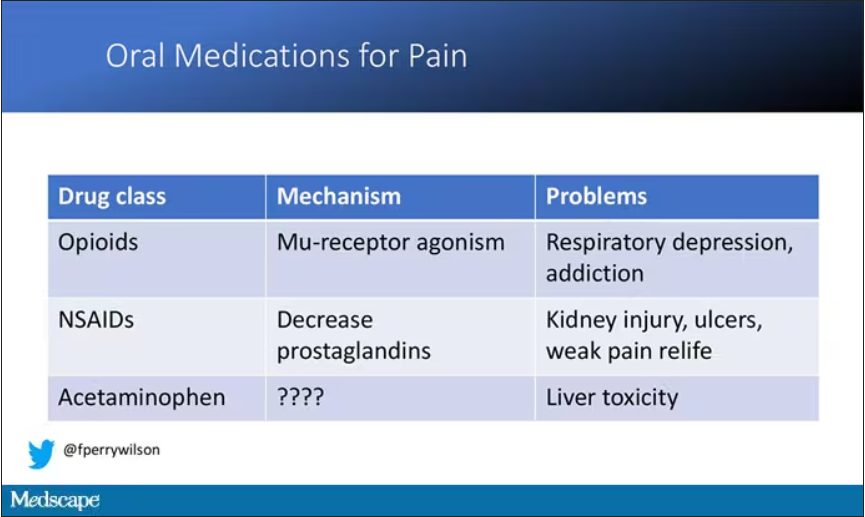

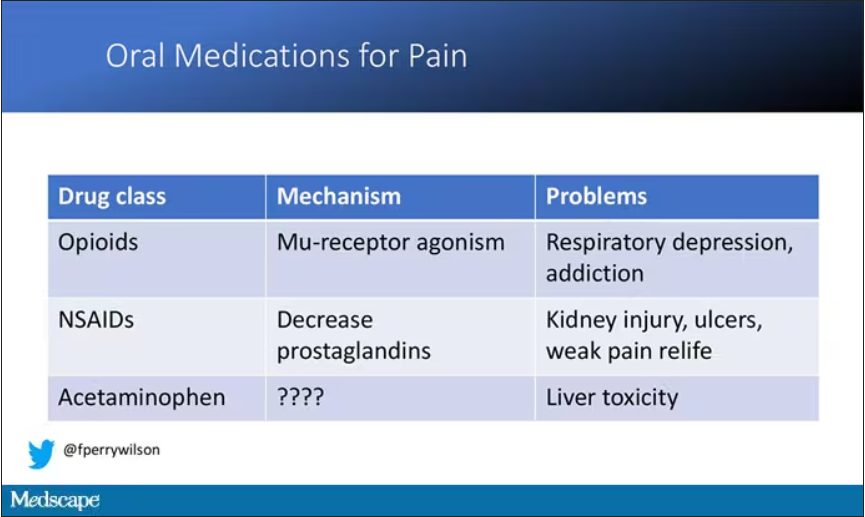

But in our everyday armamentarium, let’s be honest – we essentially have three options: opiates and opioids, which activate the mu-receptors in the brain to dull pain (and cause a host of other nasty side effects); NSAIDs, which block prostaglandin synthesis and thus limit the ability for pain-conducting neurons to get excited; and acetaminophen, which, despite being used for a century, is poorly understood.

But

If you were to zoom in on the connection between that first afferent pain fiber and the secondary nerve in the spinal cord dorsal root ganglion, you would see a receptor called Nav1.8, a voltage-gated sodium channel.

This receptor is a key part of the apparatus that passes information from nerve 1 to nerve 2, but only for fibers that transmit pain signals. In fact, humans with mutations in this receptor that leave it always in the “open” state have a severe pain syndrome. Blocking the receptor, therefore, might reduce pain.

In preclinical work, researchers identified VX-548, which doesn’t have a brand name yet, as a potent blocker of that channel even in nanomolar concentrations. Importantly, the compound was highly selective for that particular channel – about 30,000 times more selective than it was for the other sodium channels in that family.

Of course, a highly selective and specific drug does not a blockbuster analgesic make. To determine how this drug would work on humans in pain, they turned to two populations: 303 individuals undergoing abdominoplasty and 274 undergoing bunionectomy, as reported in a new paper in the New England Journal of Medicine.

I know this seems a bit random, but abdominoplasty is quite painful and a good model for soft-tissue pain. Bunionectomy is also quite a painful procedure and a useful model of bone pain. After the surgeries, patients were randomized to several different doses of VX-548, hydrocodone plus acetaminophen, or placebo for 48 hours.

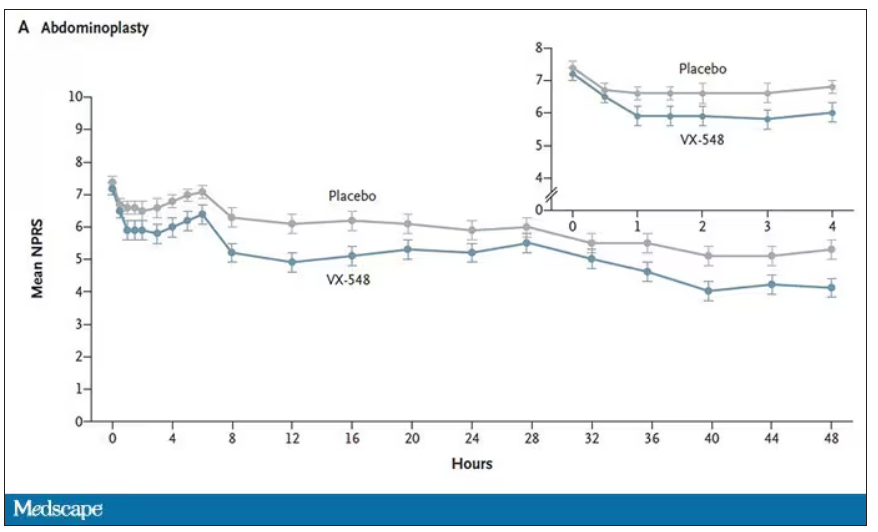

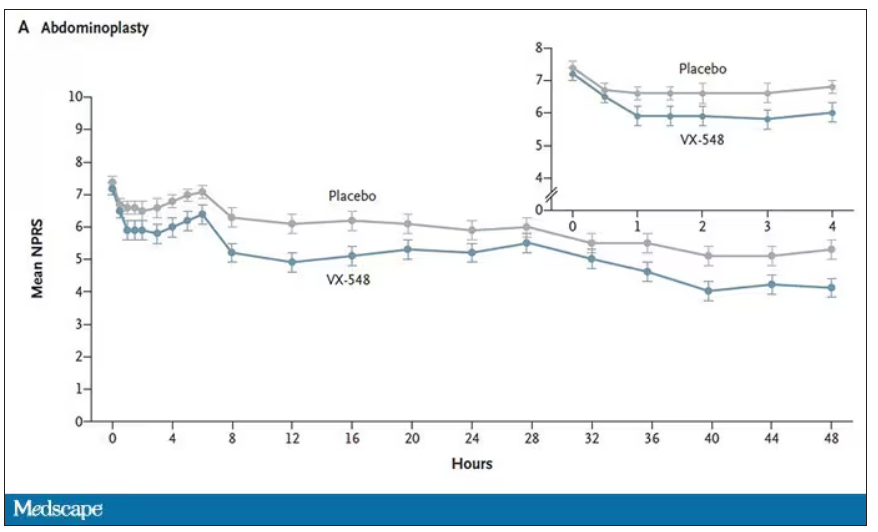

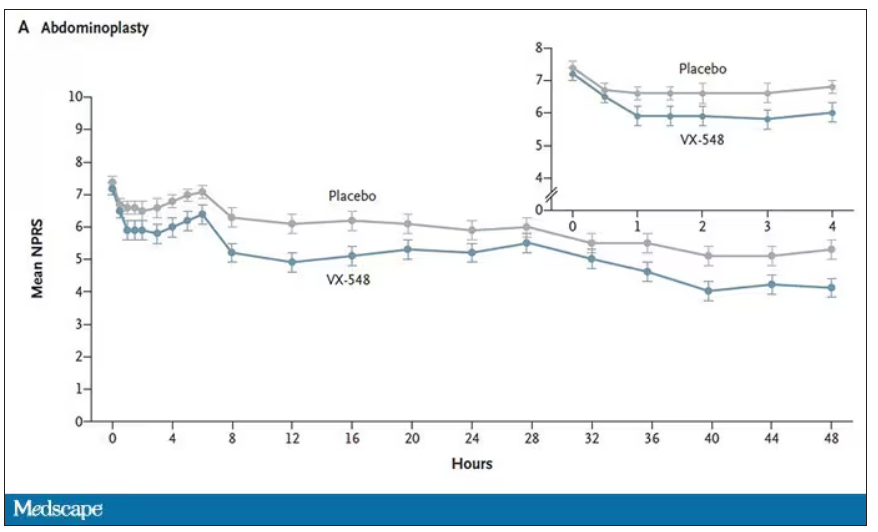

At 19 time points over that 48-hour period, participants were asked to rate their pain on a scale from 0 to 10. The primary outcome was the cumulative pain experienced over the 48 hours. So, higher pain would be worse here, but longer duration of pain would also be worse.

The story of the study is really told in this chart.

Yes, those assigned to the highest dose of VX-548 had a statistically significant lower cumulative amount of pain in the 48 hours after surgery. But the picture is really worth more than the stats here. You can see that the onset of pain relief was fairly quick, and that pain relief was sustained over time. You can also see that this is not a miracle drug. Pain scores were a bit better 48 hours out, but only by about a point and a half.

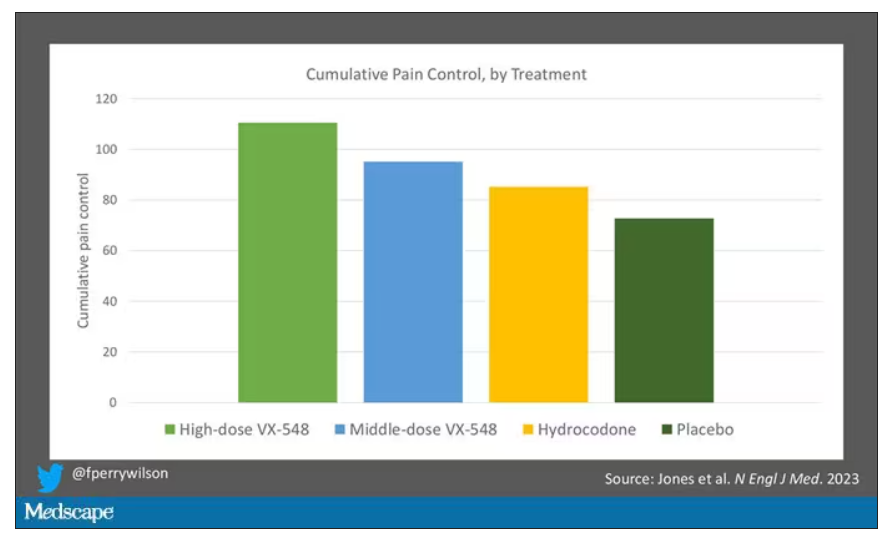

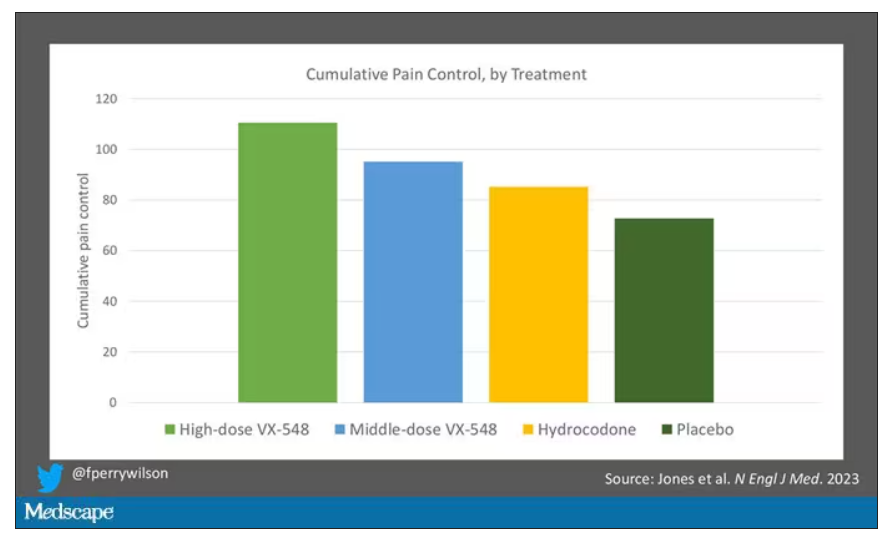

Placebo isn’t really the fair comparison here; few of us treat our postabdominoplasty patients with placebo, after all. The authors do not formally compare the effect of VX-548 with that of the opioid hydrocodone, for instance. But that doesn’t stop us.

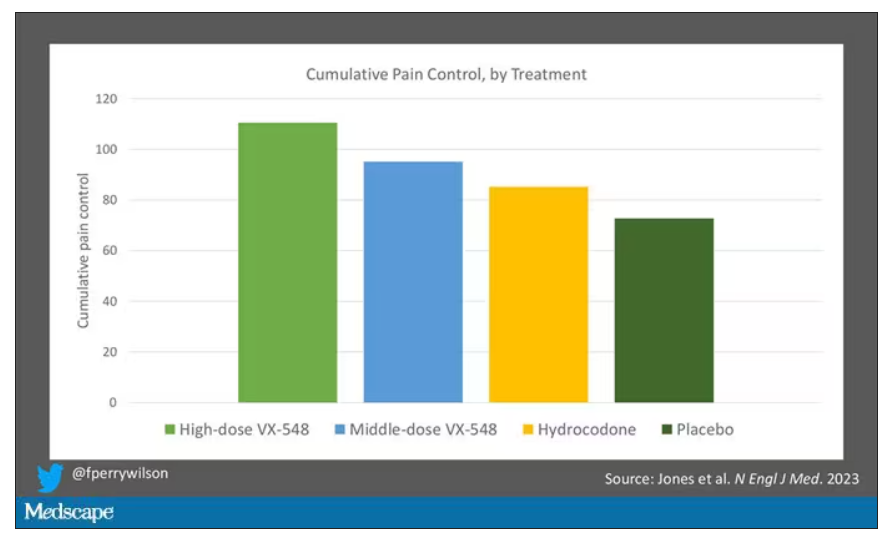

This graph, which I put together from data in the paper, shows pain control across the four randomization categories, with higher numbers indicating more (cumulative) control. While all the active agents do a bit better than placebo, VX-548 at the higher dose appears to do the best. But I should note that 5 mg of hydrocodone may not be an adequate dose for most people.

Yes, I would really have killed for an NSAID arm in this trial. Its absence, given that NSAIDs are a staple of postoperative care, is ... well, let’s just say, notable.

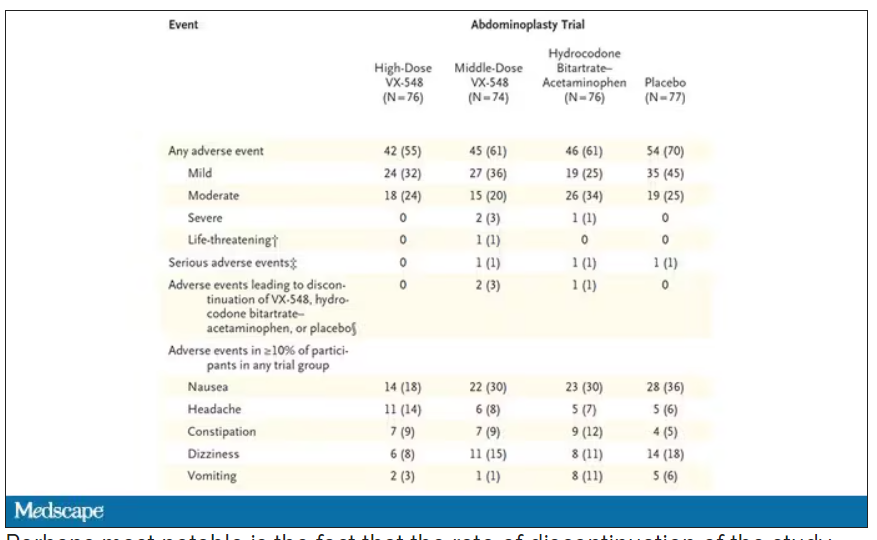

Although not a pain-destroying machine, VX-548 has some other things to recommend it. The receptor is really not found in the brain at all, which suggests that the drug should not carry much risk for dependency, though that has not been formally studied.

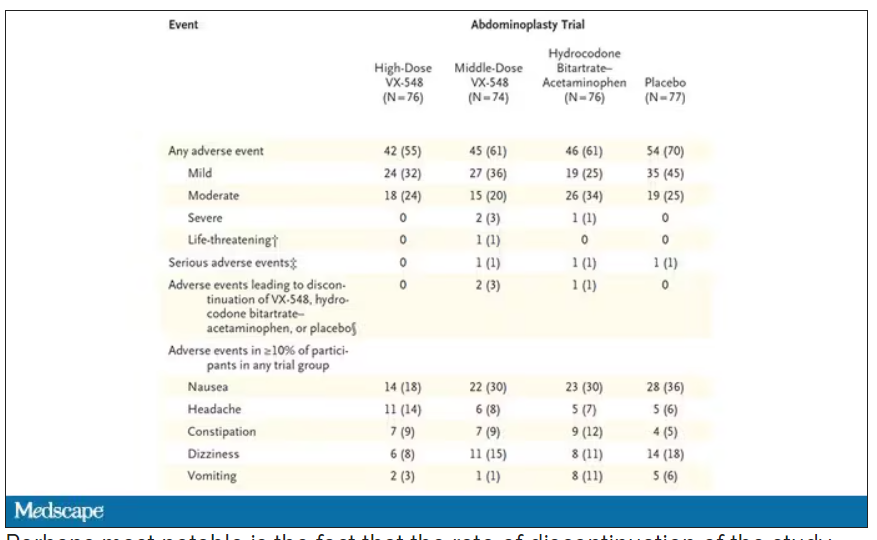

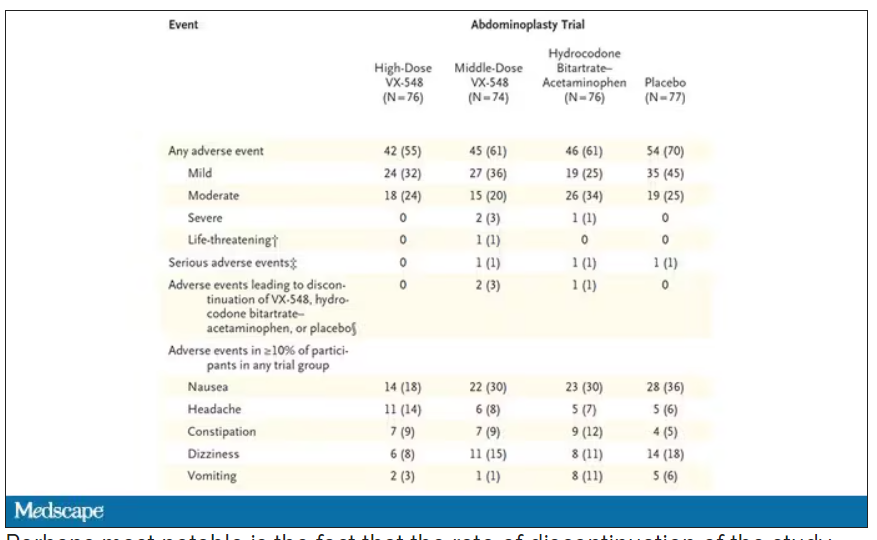

The side effects were generally mild – headache was the most common – and less prevalent than what you see even in the placebo arm.

Perhaps most notable is the fact that the rate of discontinuation of the study drug was lowest in the VX-548 arm. Patients could stop taking the pill they were assigned for any reason, ranging from perceived lack of efficacy to side effects. A low discontinuation rate indicates to me a sort of “voting with your feet” that suggests this might be a well-tolerated and reasonably effective drug.

VX-548 isn’t on the market yet; phase 3 trials are ongoing. But whether it is this particular drug or another in this class, I’m happy to see researchers trying to find new ways to target that most primeval form of suffering: pain.

Dr. Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

When you stub your toe or get a paper cut on your finger, you feel the pain in that part of your body. It feels like the pain is coming from that place. But, of course, that’s not really what is happening. Pain doesn’t really happen in your toe or your finger. It happens in your brain.

It’s a game of telephone, really. The afferent nerve fiber detects the noxious stimulus, passing that signal to the second-order neuron in the dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord, which runs it up to the thalamus to be passed to the third-order neuron which brings it to the cortex for localization and conscious perception. It’s not even a very good game of telephone. It takes about 100 ms for a pain signal to get from the hand to the brain – longer from the feet, given the greater distance. You see your foot hit the corner of the coffee table and have just enough time to think: “Oh no!” before the pain hits.

Given the Rube Goldberg nature of the process, it would seem like there are any number of places we could stop pain sensation. And sure, local anesthetics at the site of injury, or even spinal anesthetics, are powerful – if temporary and hard to administer – solutions to acute pain.

But in our everyday armamentarium, let’s be honest – we essentially have three options: opiates and opioids, which activate the mu-receptors in the brain to dull pain (and cause a host of other nasty side effects); NSAIDs, which block prostaglandin synthesis and thus limit the ability for pain-conducting neurons to get excited; and acetaminophen, which, despite being used for a century, is poorly understood.

But

If you were to zoom in on the connection between that first afferent pain fiber and the secondary nerve in the spinal cord dorsal root ganglion, you would see a receptor called Nav1.8, a voltage-gated sodium channel.

This receptor is a key part of the apparatus that passes information from nerve 1 to nerve 2, but only for fibers that transmit pain signals. In fact, humans with mutations in this receptor that leave it always in the “open” state have a severe pain syndrome. Blocking the receptor, therefore, might reduce pain.

In preclinical work, researchers identified VX-548, which doesn’t have a brand name yet, as a potent blocker of that channel even in nanomolar concentrations. Importantly, the compound was highly selective for that particular channel – about 30,000 times more selective than it was for the other sodium channels in that family.

Of course, a highly selective and specific drug does not a blockbuster analgesic make. To determine how this drug would work on humans in pain, they turned to two populations: 303 individuals undergoing abdominoplasty and 274 undergoing bunionectomy, as reported in a new paper in the New England Journal of Medicine.

I know this seems a bit random, but abdominoplasty is quite painful and a good model for soft-tissue pain. Bunionectomy is also quite a painful procedure and a useful model of bone pain. After the surgeries, patients were randomized to several different doses of VX-548, hydrocodone plus acetaminophen, or placebo for 48 hours.

At 19 time points over that 48-hour period, participants were asked to rate their pain on a scale from 0 to 10. The primary outcome was the cumulative pain experienced over the 48 hours. So, higher pain would be worse here, but longer duration of pain would also be worse.

The story of the study is really told in this chart.

Yes, those assigned to the highest dose of VX-548 had a statistically significant lower cumulative amount of pain in the 48 hours after surgery. But the picture is really worth more than the stats here. You can see that the onset of pain relief was fairly quick, and that pain relief was sustained over time. You can also see that this is not a miracle drug. Pain scores were a bit better 48 hours out, but only by about a point and a half.

Placebo isn’t really the fair comparison here; few of us treat our postabdominoplasty patients with placebo, after all. The authors do not formally compare the effect of VX-548 with that of the opioid hydrocodone, for instance. But that doesn’t stop us.

This graph, which I put together from data in the paper, shows pain control across the four randomization categories, with higher numbers indicating more (cumulative) control. While all the active agents do a bit better than placebo, VX-548 at the higher dose appears to do the best. But I should note that 5 mg of hydrocodone may not be an adequate dose for most people.

Yes, I would really have killed for an NSAID arm in this trial. Its absence, given that NSAIDs are a staple of postoperative care, is ... well, let’s just say, notable.

Although not a pain-destroying machine, VX-548 has some other things to recommend it. The receptor is really not found in the brain at all, which suggests that the drug should not carry much risk for dependency, though that has not been formally studied.

The side effects were generally mild – headache was the most common – and less prevalent than what you see even in the placebo arm.

Perhaps most notable is the fact that the rate of discontinuation of the study drug was lowest in the VX-548 arm. Patients could stop taking the pill they were assigned for any reason, ranging from perceived lack of efficacy to side effects. A low discontinuation rate indicates to me a sort of “voting with your feet” that suggests this might be a well-tolerated and reasonably effective drug.

VX-548 isn’t on the market yet; phase 3 trials are ongoing. But whether it is this particular drug or another in this class, I’m happy to see researchers trying to find new ways to target that most primeval form of suffering: pain.

Dr. Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

When you stub your toe or get a paper cut on your finger, you feel the pain in that part of your body. It feels like the pain is coming from that place. But, of course, that’s not really what is happening. Pain doesn’t really happen in your toe or your finger. It happens in your brain.

It’s a game of telephone, really. The afferent nerve fiber detects the noxious stimulus, passing that signal to the second-order neuron in the dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord, which runs it up to the thalamus to be passed to the third-order neuron which brings it to the cortex for localization and conscious perception. It’s not even a very good game of telephone. It takes about 100 ms for a pain signal to get from the hand to the brain – longer from the feet, given the greater distance. You see your foot hit the corner of the coffee table and have just enough time to think: “Oh no!” before the pain hits.

Given the Rube Goldberg nature of the process, it would seem like there are any number of places we could stop pain sensation. And sure, local anesthetics at the site of injury, or even spinal anesthetics, are powerful – if temporary and hard to administer – solutions to acute pain.

But in our everyday armamentarium, let’s be honest – we essentially have three options: opiates and opioids, which activate the mu-receptors in the brain to dull pain (and cause a host of other nasty side effects); NSAIDs, which block prostaglandin synthesis and thus limit the ability for pain-conducting neurons to get excited; and acetaminophen, which, despite being used for a century, is poorly understood.

But

If you were to zoom in on the connection between that first afferent pain fiber and the secondary nerve in the spinal cord dorsal root ganglion, you would see a receptor called Nav1.8, a voltage-gated sodium channel.

This receptor is a key part of the apparatus that passes information from nerve 1 to nerve 2, but only for fibers that transmit pain signals. In fact, humans with mutations in this receptor that leave it always in the “open” state have a severe pain syndrome. Blocking the receptor, therefore, might reduce pain.

In preclinical work, researchers identified VX-548, which doesn’t have a brand name yet, as a potent blocker of that channel even in nanomolar concentrations. Importantly, the compound was highly selective for that particular channel – about 30,000 times more selective than it was for the other sodium channels in that family.

Of course, a highly selective and specific drug does not a blockbuster analgesic make. To determine how this drug would work on humans in pain, they turned to two populations: 303 individuals undergoing abdominoplasty and 274 undergoing bunionectomy, as reported in a new paper in the New England Journal of Medicine.

I know this seems a bit random, but abdominoplasty is quite painful and a good model for soft-tissue pain. Bunionectomy is also quite a painful procedure and a useful model of bone pain. After the surgeries, patients were randomized to several different doses of VX-548, hydrocodone plus acetaminophen, or placebo for 48 hours.

At 19 time points over that 48-hour period, participants were asked to rate their pain on a scale from 0 to 10. The primary outcome was the cumulative pain experienced over the 48 hours. So, higher pain would be worse here, but longer duration of pain would also be worse.

The story of the study is really told in this chart.

Yes, those assigned to the highest dose of VX-548 had a statistically significant lower cumulative amount of pain in the 48 hours after surgery. But the picture is really worth more than the stats here. You can see that the onset of pain relief was fairly quick, and that pain relief was sustained over time. You can also see that this is not a miracle drug. Pain scores were a bit better 48 hours out, but only by about a point and a half.

Placebo isn’t really the fair comparison here; few of us treat our postabdominoplasty patients with placebo, after all. The authors do not formally compare the effect of VX-548 with that of the opioid hydrocodone, for instance. But that doesn’t stop us.

This graph, which I put together from data in the paper, shows pain control across the four randomization categories, with higher numbers indicating more (cumulative) control. While all the active agents do a bit better than placebo, VX-548 at the higher dose appears to do the best. But I should note that 5 mg of hydrocodone may not be an adequate dose for most people.

Yes, I would really have killed for an NSAID arm in this trial. Its absence, given that NSAIDs are a staple of postoperative care, is ... well, let’s just say, notable.

Although not a pain-destroying machine, VX-548 has some other things to recommend it. The receptor is really not found in the brain at all, which suggests that the drug should not carry much risk for dependency, though that has not been formally studied.

The side effects were generally mild – headache was the most common – and less prevalent than what you see even in the placebo arm.

Perhaps most notable is the fact that the rate of discontinuation of the study drug was lowest in the VX-548 arm. Patients could stop taking the pill they were assigned for any reason, ranging from perceived lack of efficacy to side effects. A low discontinuation rate indicates to me a sort of “voting with your feet” that suggests this might be a well-tolerated and reasonably effective drug.

VX-548 isn’t on the market yet; phase 3 trials are ongoing. But whether it is this particular drug or another in this class, I’m happy to see researchers trying to find new ways to target that most primeval form of suffering: pain.

Dr. Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Will this trial help solve chronic back pain?

Chronic pain, and back pain in particular, is among the most frequent concerns for patients in the primary care setting. Roughly 8% of adults in the United States say they suffer from chronic low back pain, and many of them say the pain is significant enough to impair their ability to move, work, and otherwise enjoy life. All this, despite decades of research and countless millions in funding to find the optimal approach to treating chronic pain.

As the United States crawls out of the opioid epidemic, a group of pain specialists is hoping to identify effective, personalized approaches to managing back pain. Daniel Clauw, MD, professor of anesthesiology, internal medicine, and psychiatry at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, is helping lead the BEST trial. With projected enrollment of nearly 800 patients, BEST will be the largest federally funded clinical trial of interventions to treat chronic low back pain.

In an interview, The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What are your thoughts on the current state of primary care physicians’ understanding and management of pain?

Primary care physicians need a lot of help in demystifying the diagnosis and treatment of any kind of pain, but back pain is a really good place to start. When it comes to back pain, most primary care physicians are not any more knowledgeable than a layperson.

What has the opioid debacle-cum-tragedy taught you about pain management, particular as regards people with chronic pain?

I don’t feel opioids should ever be used to treat chronic low back pain. The few long-term studies that have been performed using opioids for longer than 3 months suggest that they often make pain worse rather than just failing to make pain better – and we know they are associated with a significantly increased all-cause mortality with increased deaths from myocardial infarction, accidents, and suicides, in addition to overdose.

Given how many patients experience back pain, how did we come to the point at which primary care physicians are so ill equipped?

We’ve had terrible pain curricula in medical schools. To give you an example: I’m one of the leading pain experts in the world and I’m not allowed to teach our medical students their pain curriculum. The students learn about neurophysiology and the anatomy of the nerves, not what’s relevant in pain.

This is notorious in medical school: Curricula are almost impossible to modify and change. So it starts with poor training in medical school. And then, regardless of what education they do or don’t get in medical school, a lot of their education about pain management is through our residencies – mainly in inpatient settings, where you’re really seeing the management of acute pain and not the management of chronic pain.

People get more accustomed to managing acute pain, where opioids are a reasonable option. It’s just that when you start managing subacute or chronic pain, opioids don’t work as well.

The other big problem is that historically, most people trained in medicine think that if you have pain in your elbow, there’s got to be something wrong in your elbow. This third mechanism of pain, central sensitization – or nociplastic pain – the kind of pain that we see in fibromyalgia, headache, and low back pain, where the pain is coming from the brain – that’s confusing to people. People can have pain without any damage or inflammation to that region of the body.

Physicians are trained that if there’s pain, there’s something wrong and we have to do surgery or there’s been some trauma. Most chronic pain is none of that. There’s a big disconnect between how people are trained, and then when they go out and are seeing a tremendous number of people with chronic pain.

What are the different types of pain, and how should they inform clinicians’ understanding about what approaches might work for managing their patients in pain?

The way the central nervous system responds to pain is analogous to the loudness of an electric guitar. You can make an electric guitar louder either by strumming the strings harder or by turning up the amplifier. For many people with fibromyalgia, low back pain, and endometriosis, for example, the problem is really more that the amplifier is turned up too high rather than its being that the guitar is strummed too strongly. That kind of pain where the pain is not due to anatomic damage or inflammation is particularly flummoxing for providers.

Can you explain the design of the new study?

It’s a 13-site study looking at four treatments: enhanced self-care, cognitive-behavioral therapy, physical therapy, and duloxetine. It’s a big precision medicine trial, trying to take everything we’ve learned and putting it all into one big study.

We’re using a SMART design, which randomizes people to two of those treatments, unless they are very much improved from the first treatment. To be eligible for the trial, you have to be able to be randomized to three of the four treatments, and people can’t choose which of the four they get.

We give them one of those treatments for 12 weeks, and at the end of 12 weeks we make the call – “Did you respond or not respond?” – and then we go back to the phenotypic data we collected at the beginning of that trial and say, “What information at baseline that we collected predicts that someone is going to respond better to duloxetine or worse to duloxetine?” And then we create the phenotype that responds best to each of those four treatments.

None of our treatments works so well that someone doesn’t end up getting randomized to a second treatment. About 85% of people so far need a second treatment because they still have enough pain that they want more relief. But the nice thing about that is we’ve already done all the functional brain imaging and all these really expensive and time-consuming things.

We’re hoping to have around 700-800 people total in this trial, which means that around 170 people will get randomized to each of the four initial treatments. No one’s ever done a study that has functional brain imaging and all these other things in it with more than 80 or 100 people. The scale of this is totally unprecedented.

Given that the individual therapies don’t appear to be all that successful on their own, what is your goal?

The primary aim is to match the phenotypic characteristics of a patient with chronic low back pain with treatment response to each of these four treatments. So at the end, we can give clinicians information on which of the patients is going to respond to physical therapy, for instance.

Right now, about one out of three people respond to most treatments for pain. We think by doing a trial like this, we can take treatments that work in one out of three people and make them work in one out of two or two out of three people just by using them in the right people.

How do you differentiate between these types of pain in your study?

We phenotype people by asking them a number of questions. We also do brain imaging, look at their back with MRI, test biomechanics, and then give them four different treatments that we know work in groups of people with low back pain.

We think one of the first parts of the phenotype is, do they have pain just in their back? Or do they have pain in their back plus a lot of other body regions? Because the more body regions that people have pain in, the more likely it is that this is an amplifier problem rather than a guitar problem.

Treatments like physical therapy, surgery, and injections are going to work better for people in whom the pain is a guitar problem rather than an amplifier problem. And drugs like duloxetine, which works in the brain, and cognitive-behavioral therapy are going to work a lot better in the people with pain in multiple sites besides the back.

To pick up on your metaphor, do any symptoms help clinicians differentiate between the guitar and the amplifier?

Sleep problems, fatigue, memory problems, and mood problems are common in patients with chronic pain and are more common with amplifier pain. Because again, those are all central nervous system problems. And so we see that the people that have anxiety, depression, and a lot of distress are more likely to have this kind of pain.

Does medical imaging help?

There’s a terrible relationship between what you see on an MRI of the back and whether someone has pain or how severe the pain is going to be. There’s always going to be individuals that have a lot of anatomic damage who don’t have any pain because they happen to be on the other end of the continuum from fibromyalgia; they’re actually pain-insensitive people.

What are your thoughts about ketamine as a possible treatment for chronic pain?

I have a mentee who’s doing a ketamine trial. We’re doing psilocybin trials in patients with fibromyalgia. Ketamine is such a dirty drug; it has so many different mechanisms of action. It does have some psychedelic effects, but it also is an NMDA blocker. It really has so many different effects.

I think it’s being thrown around like water in settings where we don’t yet know it to be efficacious. Even the data in treatment-refractory depression are pretty weak, but we’re so desperate to do something for those patients. If you’re trying to harness the psychedelic properties of ketamine, I think there’s other psychedelics that are a lot more interesting, which is why we’re using psilocybin for a subset of patients. Most of us in the pain field think that the psychedelics will work best for the people with chronic pain who have a lot of comorbid psychiatric illness, especially the ones with a lot of trauma. These drugs will allow us therapeutically to get at a lot of these patients with the side-by-side psychotherapy that’s being done as people are getting care in the medicalized setting.

Dr. Clauw reported conflicts of interest with Pfizer, Tonix, Theravance, Zynerba, Samumed, Aptinyx, Daiichi Sankyo, Intec, Regeneron, Teva, Lundbeck, Virios, and Cerephex.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Chronic pain, and back pain in particular, is among the most frequent concerns for patients in the primary care setting. Roughly 8% of adults in the United States say they suffer from chronic low back pain, and many of them say the pain is significant enough to impair their ability to move, work, and otherwise enjoy life. All this, despite decades of research and countless millions in funding to find the optimal approach to treating chronic pain.

As the United States crawls out of the opioid epidemic, a group of pain specialists is hoping to identify effective, personalized approaches to managing back pain. Daniel Clauw, MD, professor of anesthesiology, internal medicine, and psychiatry at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, is helping lead the BEST trial. With projected enrollment of nearly 800 patients, BEST will be the largest federally funded clinical trial of interventions to treat chronic low back pain.

In an interview, The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What are your thoughts on the current state of primary care physicians’ understanding and management of pain?

Primary care physicians need a lot of help in demystifying the diagnosis and treatment of any kind of pain, but back pain is a really good place to start. When it comes to back pain, most primary care physicians are not any more knowledgeable than a layperson.

What has the opioid debacle-cum-tragedy taught you about pain management, particular as regards people with chronic pain?

I don’t feel opioids should ever be used to treat chronic low back pain. The few long-term studies that have been performed using opioids for longer than 3 months suggest that they often make pain worse rather than just failing to make pain better – and we know they are associated with a significantly increased all-cause mortality with increased deaths from myocardial infarction, accidents, and suicides, in addition to overdose.

Given how many patients experience back pain, how did we come to the point at which primary care physicians are so ill equipped?

We’ve had terrible pain curricula in medical schools. To give you an example: I’m one of the leading pain experts in the world and I’m not allowed to teach our medical students their pain curriculum. The students learn about neurophysiology and the anatomy of the nerves, not what’s relevant in pain.

This is notorious in medical school: Curricula are almost impossible to modify and change. So it starts with poor training in medical school. And then, regardless of what education they do or don’t get in medical school, a lot of their education about pain management is through our residencies – mainly in inpatient settings, where you’re really seeing the management of acute pain and not the management of chronic pain.

People get more accustomed to managing acute pain, where opioids are a reasonable option. It’s just that when you start managing subacute or chronic pain, opioids don’t work as well.

The other big problem is that historically, most people trained in medicine think that if you have pain in your elbow, there’s got to be something wrong in your elbow. This third mechanism of pain, central sensitization – or nociplastic pain – the kind of pain that we see in fibromyalgia, headache, and low back pain, where the pain is coming from the brain – that’s confusing to people. People can have pain without any damage or inflammation to that region of the body.

Physicians are trained that if there’s pain, there’s something wrong and we have to do surgery or there’s been some trauma. Most chronic pain is none of that. There’s a big disconnect between how people are trained, and then when they go out and are seeing a tremendous number of people with chronic pain.

What are the different types of pain, and how should they inform clinicians’ understanding about what approaches might work for managing their patients in pain?

The way the central nervous system responds to pain is analogous to the loudness of an electric guitar. You can make an electric guitar louder either by strumming the strings harder or by turning up the amplifier. For many people with fibromyalgia, low back pain, and endometriosis, for example, the problem is really more that the amplifier is turned up too high rather than its being that the guitar is strummed too strongly. That kind of pain where the pain is not due to anatomic damage or inflammation is particularly flummoxing for providers.

Can you explain the design of the new study?

It’s a 13-site study looking at four treatments: enhanced self-care, cognitive-behavioral therapy, physical therapy, and duloxetine. It’s a big precision medicine trial, trying to take everything we’ve learned and putting it all into one big study.

We’re using a SMART design, which randomizes people to two of those treatments, unless they are very much improved from the first treatment. To be eligible for the trial, you have to be able to be randomized to three of the four treatments, and people can’t choose which of the four they get.

We give them one of those treatments for 12 weeks, and at the end of 12 weeks we make the call – “Did you respond or not respond?” – and then we go back to the phenotypic data we collected at the beginning of that trial and say, “What information at baseline that we collected predicts that someone is going to respond better to duloxetine or worse to duloxetine?” And then we create the phenotype that responds best to each of those four treatments.

None of our treatments works so well that someone doesn’t end up getting randomized to a second treatment. About 85% of people so far need a second treatment because they still have enough pain that they want more relief. But the nice thing about that is we’ve already done all the functional brain imaging and all these really expensive and time-consuming things.

We’re hoping to have around 700-800 people total in this trial, which means that around 170 people will get randomized to each of the four initial treatments. No one’s ever done a study that has functional brain imaging and all these other things in it with more than 80 or 100 people. The scale of this is totally unprecedented.

Given that the individual therapies don’t appear to be all that successful on their own, what is your goal?

The primary aim is to match the phenotypic characteristics of a patient with chronic low back pain with treatment response to each of these four treatments. So at the end, we can give clinicians information on which of the patients is going to respond to physical therapy, for instance.

Right now, about one out of three people respond to most treatments for pain. We think by doing a trial like this, we can take treatments that work in one out of three people and make them work in one out of two or two out of three people just by using them in the right people.

How do you differentiate between these types of pain in your study?

We phenotype people by asking them a number of questions. We also do brain imaging, look at their back with MRI, test biomechanics, and then give them four different treatments that we know work in groups of people with low back pain.

We think one of the first parts of the phenotype is, do they have pain just in their back? Or do they have pain in their back plus a lot of other body regions? Because the more body regions that people have pain in, the more likely it is that this is an amplifier problem rather than a guitar problem.

Treatments like physical therapy, surgery, and injections are going to work better for people in whom the pain is a guitar problem rather than an amplifier problem. And drugs like duloxetine, which works in the brain, and cognitive-behavioral therapy are going to work a lot better in the people with pain in multiple sites besides the back.

To pick up on your metaphor, do any symptoms help clinicians differentiate between the guitar and the amplifier?

Sleep problems, fatigue, memory problems, and mood problems are common in patients with chronic pain and are more common with amplifier pain. Because again, those are all central nervous system problems. And so we see that the people that have anxiety, depression, and a lot of distress are more likely to have this kind of pain.

Does medical imaging help?

There’s a terrible relationship between what you see on an MRI of the back and whether someone has pain or how severe the pain is going to be. There’s always going to be individuals that have a lot of anatomic damage who don’t have any pain because they happen to be on the other end of the continuum from fibromyalgia; they’re actually pain-insensitive people.

What are your thoughts about ketamine as a possible treatment for chronic pain?

I have a mentee who’s doing a ketamine trial. We’re doing psilocybin trials in patients with fibromyalgia. Ketamine is such a dirty drug; it has so many different mechanisms of action. It does have some psychedelic effects, but it also is an NMDA blocker. It really has so many different effects.

I think it’s being thrown around like water in settings where we don’t yet know it to be efficacious. Even the data in treatment-refractory depression are pretty weak, but we’re so desperate to do something for those patients. If you’re trying to harness the psychedelic properties of ketamine, I think there’s other psychedelics that are a lot more interesting, which is why we’re using psilocybin for a subset of patients. Most of us in the pain field think that the psychedelics will work best for the people with chronic pain who have a lot of comorbid psychiatric illness, especially the ones with a lot of trauma. These drugs will allow us therapeutically to get at a lot of these patients with the side-by-side psychotherapy that’s being done as people are getting care in the medicalized setting.

Dr. Clauw reported conflicts of interest with Pfizer, Tonix, Theravance, Zynerba, Samumed, Aptinyx, Daiichi Sankyo, Intec, Regeneron, Teva, Lundbeck, Virios, and Cerephex.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Chronic pain, and back pain in particular, is among the most frequent concerns for patients in the primary care setting. Roughly 8% of adults in the United States say they suffer from chronic low back pain, and many of them say the pain is significant enough to impair their ability to move, work, and otherwise enjoy life. All this, despite decades of research and countless millions in funding to find the optimal approach to treating chronic pain.

As the United States crawls out of the opioid epidemic, a group of pain specialists is hoping to identify effective, personalized approaches to managing back pain. Daniel Clauw, MD, professor of anesthesiology, internal medicine, and psychiatry at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, is helping lead the BEST trial. With projected enrollment of nearly 800 patients, BEST will be the largest federally funded clinical trial of interventions to treat chronic low back pain.

In an interview, The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What are your thoughts on the current state of primary care physicians’ understanding and management of pain?

Primary care physicians need a lot of help in demystifying the diagnosis and treatment of any kind of pain, but back pain is a really good place to start. When it comes to back pain, most primary care physicians are not any more knowledgeable than a layperson.

What has the opioid debacle-cum-tragedy taught you about pain management, particular as regards people with chronic pain?

I don’t feel opioids should ever be used to treat chronic low back pain. The few long-term studies that have been performed using opioids for longer than 3 months suggest that they often make pain worse rather than just failing to make pain better – and we know they are associated with a significantly increased all-cause mortality with increased deaths from myocardial infarction, accidents, and suicides, in addition to overdose.

Given how many patients experience back pain, how did we come to the point at which primary care physicians are so ill equipped?

We’ve had terrible pain curricula in medical schools. To give you an example: I’m one of the leading pain experts in the world and I’m not allowed to teach our medical students their pain curriculum. The students learn about neurophysiology and the anatomy of the nerves, not what’s relevant in pain.

This is notorious in medical school: Curricula are almost impossible to modify and change. So it starts with poor training in medical school. And then, regardless of what education they do or don’t get in medical school, a lot of their education about pain management is through our residencies – mainly in inpatient settings, where you’re really seeing the management of acute pain and not the management of chronic pain.

People get more accustomed to managing acute pain, where opioids are a reasonable option. It’s just that when you start managing subacute or chronic pain, opioids don’t work as well.

The other big problem is that historically, most people trained in medicine think that if you have pain in your elbow, there’s got to be something wrong in your elbow. This third mechanism of pain, central sensitization – or nociplastic pain – the kind of pain that we see in fibromyalgia, headache, and low back pain, where the pain is coming from the brain – that’s confusing to people. People can have pain without any damage or inflammation to that region of the body.

Physicians are trained that if there’s pain, there’s something wrong and we have to do surgery or there’s been some trauma. Most chronic pain is none of that. There’s a big disconnect between how people are trained, and then when they go out and are seeing a tremendous number of people with chronic pain.

What are the different types of pain, and how should they inform clinicians’ understanding about what approaches might work for managing their patients in pain?

The way the central nervous system responds to pain is analogous to the loudness of an electric guitar. You can make an electric guitar louder either by strumming the strings harder or by turning up the amplifier. For many people with fibromyalgia, low back pain, and endometriosis, for example, the problem is really more that the amplifier is turned up too high rather than its being that the guitar is strummed too strongly. That kind of pain where the pain is not due to anatomic damage or inflammation is particularly flummoxing for providers.

Can you explain the design of the new study?

It’s a 13-site study looking at four treatments: enhanced self-care, cognitive-behavioral therapy, physical therapy, and duloxetine. It’s a big precision medicine trial, trying to take everything we’ve learned and putting it all into one big study.

We’re using a SMART design, which randomizes people to two of those treatments, unless they are very much improved from the first treatment. To be eligible for the trial, you have to be able to be randomized to three of the four treatments, and people can’t choose which of the four they get.

We give them one of those treatments for 12 weeks, and at the end of 12 weeks we make the call – “Did you respond or not respond?” – and then we go back to the phenotypic data we collected at the beginning of that trial and say, “What information at baseline that we collected predicts that someone is going to respond better to duloxetine or worse to duloxetine?” And then we create the phenotype that responds best to each of those four treatments.

None of our treatments works so well that someone doesn’t end up getting randomized to a second treatment. About 85% of people so far need a second treatment because they still have enough pain that they want more relief. But the nice thing about that is we’ve already done all the functional brain imaging and all these really expensive and time-consuming things.

We’re hoping to have around 700-800 people total in this trial, which means that around 170 people will get randomized to each of the four initial treatments. No one’s ever done a study that has functional brain imaging and all these other things in it with more than 80 or 100 people. The scale of this is totally unprecedented.

Given that the individual therapies don’t appear to be all that successful on their own, what is your goal?

The primary aim is to match the phenotypic characteristics of a patient with chronic low back pain with treatment response to each of these four treatments. So at the end, we can give clinicians information on which of the patients is going to respond to physical therapy, for instance.

Right now, about one out of three people respond to most treatments for pain. We think by doing a trial like this, we can take treatments that work in one out of three people and make them work in one out of two or two out of three people just by using them in the right people.

How do you differentiate between these types of pain in your study?

We phenotype people by asking them a number of questions. We also do brain imaging, look at their back with MRI, test biomechanics, and then give them four different treatments that we know work in groups of people with low back pain.

We think one of the first parts of the phenotype is, do they have pain just in their back? Or do they have pain in their back plus a lot of other body regions? Because the more body regions that people have pain in, the more likely it is that this is an amplifier problem rather than a guitar problem.

Treatments like physical therapy, surgery, and injections are going to work better for people in whom the pain is a guitar problem rather than an amplifier problem. And drugs like duloxetine, which works in the brain, and cognitive-behavioral therapy are going to work a lot better in the people with pain in multiple sites besides the back.

To pick up on your metaphor, do any symptoms help clinicians differentiate between the guitar and the amplifier?

Sleep problems, fatigue, memory problems, and mood problems are common in patients with chronic pain and are more common with amplifier pain. Because again, those are all central nervous system problems. And so we see that the people that have anxiety, depression, and a lot of distress are more likely to have this kind of pain.

Does medical imaging help?

There’s a terrible relationship between what you see on an MRI of the back and whether someone has pain or how severe the pain is going to be. There’s always going to be individuals that have a lot of anatomic damage who don’t have any pain because they happen to be on the other end of the continuum from fibromyalgia; they’re actually pain-insensitive people.

What are your thoughts about ketamine as a possible treatment for chronic pain?

I have a mentee who’s doing a ketamine trial. We’re doing psilocybin trials in patients with fibromyalgia. Ketamine is such a dirty drug; it has so many different mechanisms of action. It does have some psychedelic effects, but it also is an NMDA blocker. It really has so many different effects.

I think it’s being thrown around like water in settings where we don’t yet know it to be efficacious. Even the data in treatment-refractory depression are pretty weak, but we’re so desperate to do something for those patients. If you’re trying to harness the psychedelic properties of ketamine, I think there’s other psychedelics that are a lot more interesting, which is why we’re using psilocybin for a subset of patients. Most of us in the pain field think that the psychedelics will work best for the people with chronic pain who have a lot of comorbid psychiatric illness, especially the ones with a lot of trauma. These drugs will allow us therapeutically to get at a lot of these patients with the side-by-side psychotherapy that’s being done as people are getting care in the medicalized setting.

Dr. Clauw reported conflicts of interest with Pfizer, Tonix, Theravance, Zynerba, Samumed, Aptinyx, Daiichi Sankyo, Intec, Regeneron, Teva, Lundbeck, Virios, and Cerephex.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Oxycodone tied to persistent use only after vaginal delivery

“In the last decade in Ontario, oxycodone surpassed codeine as the most commonly prescribed opioid postpartum for pain control,” Jonathan Zipursky, MD, PhD, of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, ICES, Toronto, and the University of Toronto, said in an interview. “This likely had to do with concerns with codeine use during breastfeeding, many of which are unsubstantiated.

“We hypothesized that use of oxycodone would be associated with an increased risk of persistent postpartum opioid use,” he said. “However, we did not find this.”

Instead, other factors, such as the quantity of opioids initially prescribed, were probably more important risks, he said.

The team also was “a bit surprised” that oxycodone was associated with an increased risk of persistent use only among those who had a vaginal delivery, Dr. Zipursky added.

“Receipt of an opioid prescription after vaginal delivery is uncommon in Ontario. People who fill prescriptions for potent opioids, such as oxycodone, after vaginal delivery may have underlying characteristics that predispose them to chronic opioid use,” he suggested. “Some of these factors we were unable to assess using our data.”

The study was published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Oxycodone okay

The investigators analyzed data from 70,607 people (median age, 32) who filled an opioid prescription within 7 days of discharge from the hospital between 2012 and 2020. Two-thirds (69.8%) received oxycodone and one-third received (30.2%) codeine.

The median gestational age at delivery was 39 weeks, and 80% of participants had a cesarean delivery. The median opioid prescription duration was 3 days. The median opioid content per prescription was 150 morphine milligram equivalents (MMEs) among those prescribed oxycodone and 135 MMEs for codeine.

The main outcome was persistent opioid use. This was defined as one or more additional prescriptions for an opioid within 90 days of the first postpartum prescription and one or more additional prescriptions in the 91-365 days after.

Oxycodone receipt was not associated with persistent opioid use, compared with codeine (relative risk, 1.04).

However, in a secondary analysis by mode of delivery, an association was seen between a prescription for oxycodone and persistent use after vaginal (RR, 1.63), but not after cesarean (RR, 0.85), delivery.

Dr. Zipursky noted that the quantity of opioids prescribed in the initial postpartum prescription “is likely a more important modifiable risk factor for new persistent opioid use, rather than the type of opioid prescribed.”

For example, a prescription containing more than 225 MMEs (equivalent to about 30 tablets of 5 mg oxycodone and to 50 tablets of 30 mg codeine) was associated with a roughly twofold increased risk of persistent use, compared with less than 112.5 MMEs after both vaginal (odds ratio, 2.51) and cesarean (OR, 1.78) delivery.

Furthermore, a prescription duration of more than 7 days was also associated with a roughly twofold increased risk of persistent use, compared with a duration of 1-3 days after both vaginal (OR, 2.43) and cesarean (OR, 1.52) delivery.

Most risk factors for persistent opioid use – a history of mental illness, substance use disorder, and more maternal comorbidities (aggregated diagnosis groups > 10) – were consistent across modes of delivery.

“Awareness of modifiable factors associated with new, persistent opioid use may help clinicians tailor opioid prescribing while ensuring adequate analgesia after delivery,” Dr. Zipursky suggested.

Less is more

In a comment, Elaine Duryea, MD, assistant professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at UT Southwestern Medical Center and medical director of the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Clinic at Parkland Health and Hospital System, both in Dallas, said, “It is likely exposure to any opioid, rather than a specific opioid, that can promote continued use – that is, past the medically indicated period.”

Dr. Duryea was principal investigator of a study, published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, that showed a multimodal regimen that included scheduled nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acetaminophen, with opioids used as needed, resulted in a decrease in opioid use while adequately controlling pain after cesarean delivery.

“It is important to understand how to appropriately tailor the amount of opioid given to patients at the time of hospital discharge after cesarean in order to treat pain effectively but not send patients home with more opioids than [are] really needed,” she said.

It is also important to “individualize prescribing practices and maximize the use of non-opioid medication to treat postpartum and postoperative pain. Opioids should be a last resort for breakthrough pain, not first-line therapy,” Dr. Duryea concluded.

The study was funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research project grant. Dr. Zipursky has received payments from private law firms for medicolegal opinions on the safety and effectiveness of analgesics, including opioids.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“In the last decade in Ontario, oxycodone surpassed codeine as the most commonly prescribed opioid postpartum for pain control,” Jonathan Zipursky, MD, PhD, of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, ICES, Toronto, and the University of Toronto, said in an interview. “This likely had to do with concerns with codeine use during breastfeeding, many of which are unsubstantiated.

“We hypothesized that use of oxycodone would be associated with an increased risk of persistent postpartum opioid use,” he said. “However, we did not find this.”

Instead, other factors, such as the quantity of opioids initially prescribed, were probably more important risks, he said.

The team also was “a bit surprised” that oxycodone was associated with an increased risk of persistent use only among those who had a vaginal delivery, Dr. Zipursky added.

“Receipt of an opioid prescription after vaginal delivery is uncommon in Ontario. People who fill prescriptions for potent opioids, such as oxycodone, after vaginal delivery may have underlying characteristics that predispose them to chronic opioid use,” he suggested. “Some of these factors we were unable to assess using our data.”

The study was published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Oxycodone okay

The investigators analyzed data from 70,607 people (median age, 32) who filled an opioid prescription within 7 days of discharge from the hospital between 2012 and 2020. Two-thirds (69.8%) received oxycodone and one-third received (30.2%) codeine.

The median gestational age at delivery was 39 weeks, and 80% of participants had a cesarean delivery. The median opioid prescription duration was 3 days. The median opioid content per prescription was 150 morphine milligram equivalents (MMEs) among those prescribed oxycodone and 135 MMEs for codeine.

The main outcome was persistent opioid use. This was defined as one or more additional prescriptions for an opioid within 90 days of the first postpartum prescription and one or more additional prescriptions in the 91-365 days after.

Oxycodone receipt was not associated with persistent opioid use, compared with codeine (relative risk, 1.04).

However, in a secondary analysis by mode of delivery, an association was seen between a prescription for oxycodone and persistent use after vaginal (RR, 1.63), but not after cesarean (RR, 0.85), delivery.

Dr. Zipursky noted that the quantity of opioids prescribed in the initial postpartum prescription “is likely a more important modifiable risk factor for new persistent opioid use, rather than the type of opioid prescribed.”

For example, a prescription containing more than 225 MMEs (equivalent to about 30 tablets of 5 mg oxycodone and to 50 tablets of 30 mg codeine) was associated with a roughly twofold increased risk of persistent use, compared with less than 112.5 MMEs after both vaginal (odds ratio, 2.51) and cesarean (OR, 1.78) delivery.

Furthermore, a prescription duration of more than 7 days was also associated with a roughly twofold increased risk of persistent use, compared with a duration of 1-3 days after both vaginal (OR, 2.43) and cesarean (OR, 1.52) delivery.

Most risk factors for persistent opioid use – a history of mental illness, substance use disorder, and more maternal comorbidities (aggregated diagnosis groups > 10) – were consistent across modes of delivery.

“Awareness of modifiable factors associated with new, persistent opioid use may help clinicians tailor opioid prescribing while ensuring adequate analgesia after delivery,” Dr. Zipursky suggested.

Less is more

In a comment, Elaine Duryea, MD, assistant professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at UT Southwestern Medical Center and medical director of the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Clinic at Parkland Health and Hospital System, both in Dallas, said, “It is likely exposure to any opioid, rather than a specific opioid, that can promote continued use – that is, past the medically indicated period.”

Dr. Duryea was principal investigator of a study, published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, that showed a multimodal regimen that included scheduled nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acetaminophen, with opioids used as needed, resulted in a decrease in opioid use while adequately controlling pain after cesarean delivery.

“It is important to understand how to appropriately tailor the amount of opioid given to patients at the time of hospital discharge after cesarean in order to treat pain effectively but not send patients home with more opioids than [are] really needed,” she said.

It is also important to “individualize prescribing practices and maximize the use of non-opioid medication to treat postpartum and postoperative pain. Opioids should be a last resort for breakthrough pain, not first-line therapy,” Dr. Duryea concluded.

The study was funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research project grant. Dr. Zipursky has received payments from private law firms for medicolegal opinions on the safety and effectiveness of analgesics, including opioids.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“In the last decade in Ontario, oxycodone surpassed codeine as the most commonly prescribed opioid postpartum for pain control,” Jonathan Zipursky, MD, PhD, of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, ICES, Toronto, and the University of Toronto, said in an interview. “This likely had to do with concerns with codeine use during breastfeeding, many of which are unsubstantiated.

“We hypothesized that use of oxycodone would be associated with an increased risk of persistent postpartum opioid use,” he said. “However, we did not find this.”

Instead, other factors, such as the quantity of opioids initially prescribed, were probably more important risks, he said.

The team also was “a bit surprised” that oxycodone was associated with an increased risk of persistent use only among those who had a vaginal delivery, Dr. Zipursky added.

“Receipt of an opioid prescription after vaginal delivery is uncommon in Ontario. People who fill prescriptions for potent opioids, such as oxycodone, after vaginal delivery may have underlying characteristics that predispose them to chronic opioid use,” he suggested. “Some of these factors we were unable to assess using our data.”

The study was published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Oxycodone okay

The investigators analyzed data from 70,607 people (median age, 32) who filled an opioid prescription within 7 days of discharge from the hospital between 2012 and 2020. Two-thirds (69.8%) received oxycodone and one-third received (30.2%) codeine.

The median gestational age at delivery was 39 weeks, and 80% of participants had a cesarean delivery. The median opioid prescription duration was 3 days. The median opioid content per prescription was 150 morphine milligram equivalents (MMEs) among those prescribed oxycodone and 135 MMEs for codeine.

The main outcome was persistent opioid use. This was defined as one or more additional prescriptions for an opioid within 90 days of the first postpartum prescription and one or more additional prescriptions in the 91-365 days after.

Oxycodone receipt was not associated with persistent opioid use, compared with codeine (relative risk, 1.04).

However, in a secondary analysis by mode of delivery, an association was seen between a prescription for oxycodone and persistent use after vaginal (RR, 1.63), but not after cesarean (RR, 0.85), delivery.

Dr. Zipursky noted that the quantity of opioids prescribed in the initial postpartum prescription “is likely a more important modifiable risk factor for new persistent opioid use, rather than the type of opioid prescribed.”

For example, a prescription containing more than 225 MMEs (equivalent to about 30 tablets of 5 mg oxycodone and to 50 tablets of 30 mg codeine) was associated with a roughly twofold increased risk of persistent use, compared with less than 112.5 MMEs after both vaginal (odds ratio, 2.51) and cesarean (OR, 1.78) delivery.

Furthermore, a prescription duration of more than 7 days was also associated with a roughly twofold increased risk of persistent use, compared with a duration of 1-3 days after both vaginal (OR, 2.43) and cesarean (OR, 1.52) delivery.

Most risk factors for persistent opioid use – a history of mental illness, substance use disorder, and more maternal comorbidities (aggregated diagnosis groups > 10) – were consistent across modes of delivery.

“Awareness of modifiable factors associated with new, persistent opioid use may help clinicians tailor opioid prescribing while ensuring adequate analgesia after delivery,” Dr. Zipursky suggested.

Less is more

In a comment, Elaine Duryea, MD, assistant professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at UT Southwestern Medical Center and medical director of the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Clinic at Parkland Health and Hospital System, both in Dallas, said, “It is likely exposure to any opioid, rather than a specific opioid, that can promote continued use – that is, past the medically indicated period.”

Dr. Duryea was principal investigator of a study, published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, that showed a multimodal regimen that included scheduled nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acetaminophen, with opioids used as needed, resulted in a decrease in opioid use while adequately controlling pain after cesarean delivery.

“It is important to understand how to appropriately tailor the amount of opioid given to patients at the time of hospital discharge after cesarean in order to treat pain effectively but not send patients home with more opioids than [are] really needed,” she said.

It is also important to “individualize prescribing practices and maximize the use of non-opioid medication to treat postpartum and postoperative pain. Opioids should be a last resort for breakthrough pain, not first-line therapy,” Dr. Duryea concluded.

The study was funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research project grant. Dr. Zipursky has received payments from private law firms for medicolegal opinions on the safety and effectiveness of analgesics, including opioids.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE CANADIAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION JOURNAL

Innovations in pediatric chronic pain management

At the new Walnut Creek Clinic in the East Bay of the San Francisco Bay area, kids get a “Comfort Promise.”

The clinic extends the work of the Stad Center for Pediatric Pain, Palliative & Integrative Medicine beyond the locations in University of California San Francisco Benioff Children’s Hospitals in San Francisco and Oakland.

At Walnut Creek, clinical acupuncturists, massage therapists, and specialists in hypnosis complement advanced medical care with integrative techniques.

The “Comfort Promise” program, which is being rolled out at that clinic and other UCSF pediatric clinics through the end of 2024, is the clinicians’ pledge to do everything in their power to make tests, infusions, and vaccinations “practically pain free.”

Needle sticks, for example, can be a common source of pain and anxiety for kids. Techniques to minimize pain vary by age. Among the ways the clinicians minimize needle pain for a child 6- to 12-years-old are:

- Giving the child control options to pick which arm; and watch the injection, pause it, or stop it with a communication sign.

- Introducing memory shaping by asking the child about the experience afterward and presenting it in a positive way by praising the acts of sitting still, breathing deeply, or being brave.

- Using distractors such as asking the child to hold a favorite item from home, storytelling, coloring, singing, or using breathing exercises.

Stefan Friedrichsdorf, MD, chief of the UCSF division of pediatric pain, palliative & integrative medicine, said in a statement: “For kids with chronic pain, complex pain medications can cause more harm than benefit. Our goal is to combine exercise and physical therapy with integrative medicine and skills-based psychotherapy to help them become pain free in their everyday life.”

Bundling appointments for early impact

At Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, the chronic pain treatment program bundles visits with experts in several disciplines, include social workers, psychologists, and physical therapists, in addition to the medical team, so that patients can complete a first round of visits with multiple specialists in a short period, as opposed to several months.

Natalie Weatherred, APRN-NP, CPNP-PC, a pediatric nurse practitioner in anesthesiology and the pain clinic coordinator, said in an interview that the up-front visits involve between four and eight follow-up sessions in a short period with everybody in the multidisciplinary team “to really help jump-start their pain treatment.”

She pointed out that many families come from distant parts of the state or beyond so the bundled appointments are also important for easing burden on families.

Sarah Duggan, APRN-NP, CPNP-PC, also a pediatric nurse practitioner in anesthesiology at Lurie’s, pointed out that patients at their clinic often have other chronic conditions as well, such as such as postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome so the care integration is particularly important.

“We can get them the appropriate care that they need and the resources they need, much sooner than we would have been able to do 5 or 10 years ago,” Ms. Duggan said.

Virtual reality distraction instead of sedation

Henry Huang, MD, anesthesiologist and pain physician at Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, said a special team there collaborates with the Chariot Program at Stanford (Calif.) University and incorporates virtual reality to distract children from pain and anxiety and harness their imaginations during induction for anesthesia, intravenous placement, and vaccinations.

“At our institution we’ve been recruiting patients to do a proof of concept to do virtual reality distraction for pain procedures, such as nerve blocks or steroid injections,” Dr. Huang said.

Traditionally, kids would have received oral or intravenous sedation to help them cope with the fear and pain.

“We’ve been successful in several cases without relying on any sedation,” he said. “The next target is to expand that to the chronic pain population.”

The distraction techniques are promising for a wide range of ages, he said, and the programming is tailored to the child’s ability to interact with the technology.

He said he is also part of a group promoting use of ultrasound instead of x-rays to guide injections to the spine and chest to reduce children’s exposure to radiation. His group is helping teach these methods to other clinicians nationally.

Dr. Huang said the most important development in chronic pediatric pain has been the growth of rehab centers that include the medical team, and practitioners from psychology as well as occupational and physical therapy.

“More and more hospitals are recognizing the importance of these pain rehab centers,” he said.

The problem, Dr. Huang said, is that these programs have always been resource intensive and involve highly specialized clinicians. The cost and the limited number of specialists make it difficult for widespread rollout.

“That’s always been the challenge from the pediatric pain world,” he said.

Recognizing the complexity of kids’ chronic pain

Angela Garcia, MD, a consulting physician for pediatric rehabilitation medicine at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh said

Techniques such as biofeedback and acupuncture are becoming more mainstream in pediatric chronic care, she said.

At the UPMC clinic, children and their families talk with a care team about their values and what they want to accomplish in managing the child’s pain. They ask what the pain is preventing the child from doing.

“Their goals really are our goals,” she said.

She said she also refers almost all patients to one of the center’s pain psychologists.

“Pain is biopsychosocial,” she said. “We want to make sure we’re addressing how to cope with pain.”

Dr. Garcia said she hopes nutritional therapy is one of the next approaches the clinic will incorporate, particularly surrounding how dietary changes can reduce inflammation “and heal the body from the inside out.”

She said the hospital is also looking at developing an inpatient pain program for kids whose functioning has changed so drastically that they need more intensive therapies.

Whatever the treatment approach, she said, addressing the pain early is critical.

“There is an increased risk of a child with chronic pain becoming an adult with chronic pain,” Dr. Garcia pointed out, “and that can lead to a decrease in the ability to participate in society.”

Ms. Weatherred, Ms. Duggan, Dr. Huang, and Dr. Garcia reported no relevant financial relationships.

At the new Walnut Creek Clinic in the East Bay of the San Francisco Bay area, kids get a “Comfort Promise.”

The clinic extends the work of the Stad Center for Pediatric Pain, Palliative & Integrative Medicine beyond the locations in University of California San Francisco Benioff Children’s Hospitals in San Francisco and Oakland.

At Walnut Creek, clinical acupuncturists, massage therapists, and specialists in hypnosis complement advanced medical care with integrative techniques.

The “Comfort Promise” program, which is being rolled out at that clinic and other UCSF pediatric clinics through the end of 2024, is the clinicians’ pledge to do everything in their power to make tests, infusions, and vaccinations “practically pain free.”

Needle sticks, for example, can be a common source of pain and anxiety for kids. Techniques to minimize pain vary by age. Among the ways the clinicians minimize needle pain for a child 6- to 12-years-old are:

- Giving the child control options to pick which arm; and watch the injection, pause it, or stop it with a communication sign.

- Introducing memory shaping by asking the child about the experience afterward and presenting it in a positive way by praising the acts of sitting still, breathing deeply, or being brave.

- Using distractors such as asking the child to hold a favorite item from home, storytelling, coloring, singing, or using breathing exercises.

Stefan Friedrichsdorf, MD, chief of the UCSF division of pediatric pain, palliative & integrative medicine, said in a statement: “For kids with chronic pain, complex pain medications can cause more harm than benefit. Our goal is to combine exercise and physical therapy with integrative medicine and skills-based psychotherapy to help them become pain free in their everyday life.”

Bundling appointments for early impact

At Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, the chronic pain treatment program bundles visits with experts in several disciplines, include social workers, psychologists, and physical therapists, in addition to the medical team, so that patients can complete a first round of visits with multiple specialists in a short period, as opposed to several months.

Natalie Weatherred, APRN-NP, CPNP-PC, a pediatric nurse practitioner in anesthesiology and the pain clinic coordinator, said in an interview that the up-front visits involve between four and eight follow-up sessions in a short period with everybody in the multidisciplinary team “to really help jump-start their pain treatment.”

She pointed out that many families come from distant parts of the state or beyond so the bundled appointments are also important for easing burden on families.

Sarah Duggan, APRN-NP, CPNP-PC, also a pediatric nurse practitioner in anesthesiology at Lurie’s, pointed out that patients at their clinic often have other chronic conditions as well, such as such as postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome so the care integration is particularly important.

“We can get them the appropriate care that they need and the resources they need, much sooner than we would have been able to do 5 or 10 years ago,” Ms. Duggan said.

Virtual reality distraction instead of sedation

Henry Huang, MD, anesthesiologist and pain physician at Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, said a special team there collaborates with the Chariot Program at Stanford (Calif.) University and incorporates virtual reality to distract children from pain and anxiety and harness their imaginations during induction for anesthesia, intravenous placement, and vaccinations.

“At our institution we’ve been recruiting patients to do a proof of concept to do virtual reality distraction for pain procedures, such as nerve blocks or steroid injections,” Dr. Huang said.

Traditionally, kids would have received oral or intravenous sedation to help them cope with the fear and pain.

“We’ve been successful in several cases without relying on any sedation,” he said. “The next target is to expand that to the chronic pain population.”

The distraction techniques are promising for a wide range of ages, he said, and the programming is tailored to the child’s ability to interact with the technology.

He said he is also part of a group promoting use of ultrasound instead of x-rays to guide injections to the spine and chest to reduce children’s exposure to radiation. His group is helping teach these methods to other clinicians nationally.

Dr. Huang said the most important development in chronic pediatric pain has been the growth of rehab centers that include the medical team, and practitioners from psychology as well as occupational and physical therapy.

“More and more hospitals are recognizing the importance of these pain rehab centers,” he said.

The problem, Dr. Huang said, is that these programs have always been resource intensive and involve highly specialized clinicians. The cost and the limited number of specialists make it difficult for widespread rollout.

“That’s always been the challenge from the pediatric pain world,” he said.

Recognizing the complexity of kids’ chronic pain

Angela Garcia, MD, a consulting physician for pediatric rehabilitation medicine at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh said

Techniques such as biofeedback and acupuncture are becoming more mainstream in pediatric chronic care, she said.

At the UPMC clinic, children and their families talk with a care team about their values and what they want to accomplish in managing the child’s pain. They ask what the pain is preventing the child from doing.

“Their goals really are our goals,” she said.

She said she also refers almost all patients to one of the center’s pain psychologists.

“Pain is biopsychosocial,” she said. “We want to make sure we’re addressing how to cope with pain.”

Dr. Garcia said she hopes nutritional therapy is one of the next approaches the clinic will incorporate, particularly surrounding how dietary changes can reduce inflammation “and heal the body from the inside out.”

She said the hospital is also looking at developing an inpatient pain program for kids whose functioning has changed so drastically that they need more intensive therapies.

Whatever the treatment approach, she said, addressing the pain early is critical.

“There is an increased risk of a child with chronic pain becoming an adult with chronic pain,” Dr. Garcia pointed out, “and that can lead to a decrease in the ability to participate in society.”

Ms. Weatherred, Ms. Duggan, Dr. Huang, and Dr. Garcia reported no relevant financial relationships.

At the new Walnut Creek Clinic in the East Bay of the San Francisco Bay area, kids get a “Comfort Promise.”

The clinic extends the work of the Stad Center for Pediatric Pain, Palliative & Integrative Medicine beyond the locations in University of California San Francisco Benioff Children’s Hospitals in San Francisco and Oakland.

At Walnut Creek, clinical acupuncturists, massage therapists, and specialists in hypnosis complement advanced medical care with integrative techniques.

The “Comfort Promise” program, which is being rolled out at that clinic and other UCSF pediatric clinics through the end of 2024, is the clinicians’ pledge to do everything in their power to make tests, infusions, and vaccinations “practically pain free.”

Needle sticks, for example, can be a common source of pain and anxiety for kids. Techniques to minimize pain vary by age. Among the ways the clinicians minimize needle pain for a child 6- to 12-years-old are:

- Giving the child control options to pick which arm; and watch the injection, pause it, or stop it with a communication sign.

- Introducing memory shaping by asking the child about the experience afterward and presenting it in a positive way by praising the acts of sitting still, breathing deeply, or being brave.