User login

For MD-IQ on Family Practice News, but a regular topic for Rheumatology News

OARSI to FDA: Take osteoarthritis seriously

LAS VEGAS – The Osteoarthritis Research Society International has submitted a 103-page white paper to the Food and Drug Administration, the gist of which is captured in its title: “Osteoarthritis: A Serious Disease.”

The purpose of the voluminous white paper is to persuade FDA officials that osteoarthritis (OA) meets the agency’s formal definition of a serious disease for which there are currently no satisfactory treatments. That recognition would result in removal of current regulatory barriers to development of new structure-modifying treatments for OA, instead allowing such efforts to fall within the agency’s accelerated approval program, Marc C. Hochberg, MD, a coauthor of the white paper, explained at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

OARSI would like to see novel investigational therapies be allowed to advance through the developmental pipeline on the basis of favorable changes in clinically relevant biomarkers – be they biochemical or imaging – as intermediate endpoints serving as surrogates for structural change endpoints and meaningful clinical outcomes.

There is an enormous unmet need for effective disease-modifying therapies for OA. Establishing a more flexible regulatory environment for drug development by designating OA as a serious disease is expected to rekindle pharmaceutical industry interest in developing such products, which at present is at an ebb, he continued at the congress sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

The FDA has defined a serious disease as “a disease or condition associated with morbidity that has substantial impact on day-to-day functioning. Short-lived and self-limiting morbidity will usually not be sufficient, but the morbidity need not be irreversible if it is persistent or recurrent. Whether a disease or condition is serious is a matter of clinical judgment, based on its impact on such factors as survival, day-to-day functioning, or the likelihood that the disease, if left untreated, will progress from a less severe condition to a more serious one.”

The white paper makes the case that OA fits that description to a T. Dr. Hochberg said the big picture regarding OA as described in the white paper is this: It’s the most common form of arthritis, affecting more than 250 million people worldwide. And its costs approach 2% of the gross national product in the United States and other developed countries.

“Osteoarthritis accounts for more functional limitation, work loss, and physical disability than any other chronic disease, including cardiovascular disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,” the rheumatologist said.

The white paper cites published data in support of these and other key points. At OARSI 2017, Dr. Hochberg presented highlights from the white paper, submitted to the FDA in December 2016:

• OA prevalence is relentlessly climbing. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention put the U.S. prevalence of OA at 46 million in 2004 and has projected that it will reach 63 million in 2020 and 78 million Americans by 2040. The rise is being driven by the aging of the baby boomers, the obesity epidemic, predisposing physical injuries, and sedentary behavior.

• OA is expensive for patients and society. The combined direct medical costs and indirect costs stemming from lost earnings from OA amount to an estimated $461 billion annually in the United States.

• OA exacts a steep toll in years lived with disability (YLD). Estimated YLD from OA jumped by 75% during 1990-2013. This increase in YLD was exceeded only by dementia at 84% and diabetes at 135%. OA accounts for 1.6% of overall YLD in the United States, a rate comparable to ischemic heart disease at 1.63% and more than twice that for rheumatoid arthritis at 0.68%.

• Comorbidities are the rule. Various studies have estimated that 59%-87% of adults with OA have at least one additional significant chronic condition. The median number is two. One-third of OA patients have four or more additional comorbid conditions. The most common are cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, metabolic syndrome, depression, anxiety, and falls and fractures.

• No effective treatments exist. There are no approved drugs that can prevent or even slow progression of OA to the point where total joint replacement is needed. Current medications are focused on pain relief and maintenance of functional independence. But these drugs are associated with significant risks of life-threatening side effects. NSAIDs have been linked to increased risk of cardiovascular events, GI bleeding, chronic kidney disease, and heart failure. And while opioids provide a small benefit in terms of pain relief, this is outweighed by the associated risks of falls, fractures, dependence, overdose, and death. All of these risks are accentuated in the presence of the common comorbid conditions associated with OA.

• OA increases the risk of dying prematurely. In a meta-analysis of individual patient data from the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study and the Johnston County (N.C.) Osteoarthritis Project conducted specifically for the white paper, investigators determined that OA was associated with a 23% increase in the risk of death independent of age, race, and sex. This excess mortality is attributable in part to the presence of the metabolic syndrome and other commonly comorbid conditions, reduced physical activity because of OA disability, and the use of NSAIDs and opioid analgesics for symptomatic control.

The OARSI initiative is supported by EMD Serono, Fidia Pharma, Flexion Therapeutics, Nordic Biosciences, and Spinifex. Dr. Hochberg reported having numerous financial relationships with industry.

LAS VEGAS – The Osteoarthritis Research Society International has submitted a 103-page white paper to the Food and Drug Administration, the gist of which is captured in its title: “Osteoarthritis: A Serious Disease.”

The purpose of the voluminous white paper is to persuade FDA officials that osteoarthritis (OA) meets the agency’s formal definition of a serious disease for which there are currently no satisfactory treatments. That recognition would result in removal of current regulatory barriers to development of new structure-modifying treatments for OA, instead allowing such efforts to fall within the agency’s accelerated approval program, Marc C. Hochberg, MD, a coauthor of the white paper, explained at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

OARSI would like to see novel investigational therapies be allowed to advance through the developmental pipeline on the basis of favorable changes in clinically relevant biomarkers – be they biochemical or imaging – as intermediate endpoints serving as surrogates for structural change endpoints and meaningful clinical outcomes.

There is an enormous unmet need for effective disease-modifying therapies for OA. Establishing a more flexible regulatory environment for drug development by designating OA as a serious disease is expected to rekindle pharmaceutical industry interest in developing such products, which at present is at an ebb, he continued at the congress sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

The FDA has defined a serious disease as “a disease or condition associated with morbidity that has substantial impact on day-to-day functioning. Short-lived and self-limiting morbidity will usually not be sufficient, but the morbidity need not be irreversible if it is persistent or recurrent. Whether a disease or condition is serious is a matter of clinical judgment, based on its impact on such factors as survival, day-to-day functioning, or the likelihood that the disease, if left untreated, will progress from a less severe condition to a more serious one.”

The white paper makes the case that OA fits that description to a T. Dr. Hochberg said the big picture regarding OA as described in the white paper is this: It’s the most common form of arthritis, affecting more than 250 million people worldwide. And its costs approach 2% of the gross national product in the United States and other developed countries.

“Osteoarthritis accounts for more functional limitation, work loss, and physical disability than any other chronic disease, including cardiovascular disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,” the rheumatologist said.

The white paper cites published data in support of these and other key points. At OARSI 2017, Dr. Hochberg presented highlights from the white paper, submitted to the FDA in December 2016:

• OA prevalence is relentlessly climbing. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention put the U.S. prevalence of OA at 46 million in 2004 and has projected that it will reach 63 million in 2020 and 78 million Americans by 2040. The rise is being driven by the aging of the baby boomers, the obesity epidemic, predisposing physical injuries, and sedentary behavior.

• OA is expensive for patients and society. The combined direct medical costs and indirect costs stemming from lost earnings from OA amount to an estimated $461 billion annually in the United States.

• OA exacts a steep toll in years lived with disability (YLD). Estimated YLD from OA jumped by 75% during 1990-2013. This increase in YLD was exceeded only by dementia at 84% and diabetes at 135%. OA accounts for 1.6% of overall YLD in the United States, a rate comparable to ischemic heart disease at 1.63% and more than twice that for rheumatoid arthritis at 0.68%.

• Comorbidities are the rule. Various studies have estimated that 59%-87% of adults with OA have at least one additional significant chronic condition. The median number is two. One-third of OA patients have four or more additional comorbid conditions. The most common are cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, metabolic syndrome, depression, anxiety, and falls and fractures.

• No effective treatments exist. There are no approved drugs that can prevent or even slow progression of OA to the point where total joint replacement is needed. Current medications are focused on pain relief and maintenance of functional independence. But these drugs are associated with significant risks of life-threatening side effects. NSAIDs have been linked to increased risk of cardiovascular events, GI bleeding, chronic kidney disease, and heart failure. And while opioids provide a small benefit in terms of pain relief, this is outweighed by the associated risks of falls, fractures, dependence, overdose, and death. All of these risks are accentuated in the presence of the common comorbid conditions associated with OA.

• OA increases the risk of dying prematurely. In a meta-analysis of individual patient data from the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study and the Johnston County (N.C.) Osteoarthritis Project conducted specifically for the white paper, investigators determined that OA was associated with a 23% increase in the risk of death independent of age, race, and sex. This excess mortality is attributable in part to the presence of the metabolic syndrome and other commonly comorbid conditions, reduced physical activity because of OA disability, and the use of NSAIDs and opioid analgesics for symptomatic control.

The OARSI initiative is supported by EMD Serono, Fidia Pharma, Flexion Therapeutics, Nordic Biosciences, and Spinifex. Dr. Hochberg reported having numerous financial relationships with industry.

LAS VEGAS – The Osteoarthritis Research Society International has submitted a 103-page white paper to the Food and Drug Administration, the gist of which is captured in its title: “Osteoarthritis: A Serious Disease.”

The purpose of the voluminous white paper is to persuade FDA officials that osteoarthritis (OA) meets the agency’s formal definition of a serious disease for which there are currently no satisfactory treatments. That recognition would result in removal of current regulatory barriers to development of new structure-modifying treatments for OA, instead allowing such efforts to fall within the agency’s accelerated approval program, Marc C. Hochberg, MD, a coauthor of the white paper, explained at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

OARSI would like to see novel investigational therapies be allowed to advance through the developmental pipeline on the basis of favorable changes in clinically relevant biomarkers – be they biochemical or imaging – as intermediate endpoints serving as surrogates for structural change endpoints and meaningful clinical outcomes.

There is an enormous unmet need for effective disease-modifying therapies for OA. Establishing a more flexible regulatory environment for drug development by designating OA as a serious disease is expected to rekindle pharmaceutical industry interest in developing such products, which at present is at an ebb, he continued at the congress sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

The FDA has defined a serious disease as “a disease or condition associated with morbidity that has substantial impact on day-to-day functioning. Short-lived and self-limiting morbidity will usually not be sufficient, but the morbidity need not be irreversible if it is persistent or recurrent. Whether a disease or condition is serious is a matter of clinical judgment, based on its impact on such factors as survival, day-to-day functioning, or the likelihood that the disease, if left untreated, will progress from a less severe condition to a more serious one.”

The white paper makes the case that OA fits that description to a T. Dr. Hochberg said the big picture regarding OA as described in the white paper is this: It’s the most common form of arthritis, affecting more than 250 million people worldwide. And its costs approach 2% of the gross national product in the United States and other developed countries.

“Osteoarthritis accounts for more functional limitation, work loss, and physical disability than any other chronic disease, including cardiovascular disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,” the rheumatologist said.

The white paper cites published data in support of these and other key points. At OARSI 2017, Dr. Hochberg presented highlights from the white paper, submitted to the FDA in December 2016:

• OA prevalence is relentlessly climbing. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention put the U.S. prevalence of OA at 46 million in 2004 and has projected that it will reach 63 million in 2020 and 78 million Americans by 2040. The rise is being driven by the aging of the baby boomers, the obesity epidemic, predisposing physical injuries, and sedentary behavior.

• OA is expensive for patients and society. The combined direct medical costs and indirect costs stemming from lost earnings from OA amount to an estimated $461 billion annually in the United States.

• OA exacts a steep toll in years lived with disability (YLD). Estimated YLD from OA jumped by 75% during 1990-2013. This increase in YLD was exceeded only by dementia at 84% and diabetes at 135%. OA accounts for 1.6% of overall YLD in the United States, a rate comparable to ischemic heart disease at 1.63% and more than twice that for rheumatoid arthritis at 0.68%.

• Comorbidities are the rule. Various studies have estimated that 59%-87% of adults with OA have at least one additional significant chronic condition. The median number is two. One-third of OA patients have four or more additional comorbid conditions. The most common are cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, metabolic syndrome, depression, anxiety, and falls and fractures.

• No effective treatments exist. There are no approved drugs that can prevent or even slow progression of OA to the point where total joint replacement is needed. Current medications are focused on pain relief and maintenance of functional independence. But these drugs are associated with significant risks of life-threatening side effects. NSAIDs have been linked to increased risk of cardiovascular events, GI bleeding, chronic kidney disease, and heart failure. And while opioids provide a small benefit in terms of pain relief, this is outweighed by the associated risks of falls, fractures, dependence, overdose, and death. All of these risks are accentuated in the presence of the common comorbid conditions associated with OA.

• OA increases the risk of dying prematurely. In a meta-analysis of individual patient data from the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study and the Johnston County (N.C.) Osteoarthritis Project conducted specifically for the white paper, investigators determined that OA was associated with a 23% increase in the risk of death independent of age, race, and sex. This excess mortality is attributable in part to the presence of the metabolic syndrome and other commonly comorbid conditions, reduced physical activity because of OA disability, and the use of NSAIDs and opioid analgesics for symptomatic control.

The OARSI initiative is supported by EMD Serono, Fidia Pharma, Flexion Therapeutics, Nordic Biosciences, and Spinifex. Dr. Hochberg reported having numerous financial relationships with industry.

AT OARSI 2017

Lifetime risk of hand OA comes close to 40%

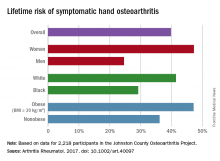

Almost 40% of Americans can expect to develop hand osteoarthritis (OA) in their lifetimes, according to an analysis involving participants from an ongoing population-based, prospective cohort study.

The overall risk, 39.8%, is based on data from 2,218 eligible subjects in the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project, but there is significant variation among various subgroups, said Jin Qin, ScD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and her associates (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 May 4. doi: 10.1002/art.40097).

This report is the first to estimate the lifetime risk of symptomatic hand OA, they noted, and “given the aging population and increasing life expectancy in the United States, it is reasonable to expect that more Americans will be affected by this painful and debilitating condition in the years to come.”

The study was funded by the CDC and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The investigators did not include any disclosures in the report.

Almost 40% of Americans can expect to develop hand osteoarthritis (OA) in their lifetimes, according to an analysis involving participants from an ongoing population-based, prospective cohort study.

The overall risk, 39.8%, is based on data from 2,218 eligible subjects in the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project, but there is significant variation among various subgroups, said Jin Qin, ScD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and her associates (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 May 4. doi: 10.1002/art.40097).

This report is the first to estimate the lifetime risk of symptomatic hand OA, they noted, and “given the aging population and increasing life expectancy in the United States, it is reasonable to expect that more Americans will be affected by this painful and debilitating condition in the years to come.”

The study was funded by the CDC and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The investigators did not include any disclosures in the report.

Almost 40% of Americans can expect to develop hand osteoarthritis (OA) in their lifetimes, according to an analysis involving participants from an ongoing population-based, prospective cohort study.

The overall risk, 39.8%, is based on data from 2,218 eligible subjects in the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project, but there is significant variation among various subgroups, said Jin Qin, ScD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and her associates (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 May 4. doi: 10.1002/art.40097).

This report is the first to estimate the lifetime risk of symptomatic hand OA, they noted, and “given the aging population and increasing life expectancy in the United States, it is reasonable to expect that more Americans will be affected by this painful and debilitating condition in the years to come.”

The study was funded by the CDC and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The investigators did not include any disclosures in the report.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

No increase in hand osteoarthritis seen in Sjögren’s syndrome

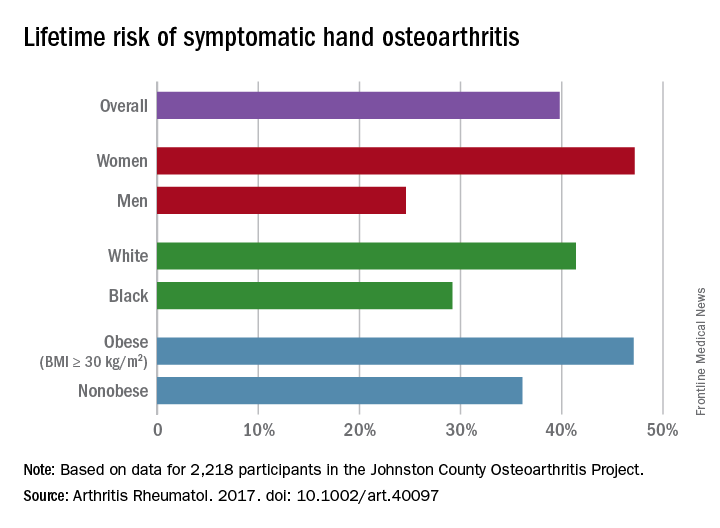

LAS VEGAS – Patients with Sjögren’s syndrome do not have an increased prevalence of hand osteoarthritis, but they are strongly predisposed to have a history of hypothyroidism, Jeremie Sellam, MD, reported at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

Both of these findings in his small case-control study were unexpected, he added at the congress sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

The study included 34 women with primary Sjögren’s syndrome according to the 2002 American-European Consensus Group criteria and 54 female controls with sicca syndrome but no autoantibodies and no Sjögren’s syndrome. All subjects were evaluated at a specialized tertiary Sjögren’s syndrome clinic. The controls were referred there to ascertain whether they had Sjögren’s syndrome.

Among the Sjögren’s syndrome patients, 41% had radiographic evidence of hand osteoarthritis, 12% had symptomatic hand osteoarthritis, and 9% had erosive hand osteoarthritis. In the sicca syndrome–only patients, the rates were similar at 52%, 28%, and 9%, respectively.

Looking for commonalities and differences between the Sjögren’s syndrome patients and controls, Dr. Sellam and his coinvestigators noted that the Sjögren’s syndrome patients were significantly older, with an average age of 64 years, compared with 48.5 years in the controls.

Impressively, two-thirds of the 15 Sjögren’s syndrome patients with hand osteoarthritis had a history of hypothyroidism, compared with just 15% of the 27 non-autoimmune sicca syndrome patients with hand osteoarthritis and one-quarter of the Sjögren’s syndrome patients without hand osteoarthritis. This suggests a possible interaction between Sjögren’s syndrome, hand osteoarthritis, and a history of hypothyroidism which merits further study, according to the rheumatologist.

Because of the relatively small patient numbers in the French study, Dr. Sellam and coworkers ran a crosscheck with data from the Framingham Osteoarthritis Study and found hand osteoarthritis prevalence rates comparable to their own findings. For example, the prevalences of radiographic and erosive hand osteoarthritis in the French Sjögren’s syndrome and non-autoimmune sicca syndrome groups were similar to the 44% and 10% figures, respectively, in the general population of age-matched Framingham women (Ann Rheum Dis. 2011 Sep;70[9]:1581-6).

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

LAS VEGAS – Patients with Sjögren’s syndrome do not have an increased prevalence of hand osteoarthritis, but they are strongly predisposed to have a history of hypothyroidism, Jeremie Sellam, MD, reported at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

Both of these findings in his small case-control study were unexpected, he added at the congress sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

The study included 34 women with primary Sjögren’s syndrome according to the 2002 American-European Consensus Group criteria and 54 female controls with sicca syndrome but no autoantibodies and no Sjögren’s syndrome. All subjects were evaluated at a specialized tertiary Sjögren’s syndrome clinic. The controls were referred there to ascertain whether they had Sjögren’s syndrome.

Among the Sjögren’s syndrome patients, 41% had radiographic evidence of hand osteoarthritis, 12% had symptomatic hand osteoarthritis, and 9% had erosive hand osteoarthritis. In the sicca syndrome–only patients, the rates were similar at 52%, 28%, and 9%, respectively.

Looking for commonalities and differences between the Sjögren’s syndrome patients and controls, Dr. Sellam and his coinvestigators noted that the Sjögren’s syndrome patients were significantly older, with an average age of 64 years, compared with 48.5 years in the controls.

Impressively, two-thirds of the 15 Sjögren’s syndrome patients with hand osteoarthritis had a history of hypothyroidism, compared with just 15% of the 27 non-autoimmune sicca syndrome patients with hand osteoarthritis and one-quarter of the Sjögren’s syndrome patients without hand osteoarthritis. This suggests a possible interaction between Sjögren’s syndrome, hand osteoarthritis, and a history of hypothyroidism which merits further study, according to the rheumatologist.

Because of the relatively small patient numbers in the French study, Dr. Sellam and coworkers ran a crosscheck with data from the Framingham Osteoarthritis Study and found hand osteoarthritis prevalence rates comparable to their own findings. For example, the prevalences of radiographic and erosive hand osteoarthritis in the French Sjögren’s syndrome and non-autoimmune sicca syndrome groups were similar to the 44% and 10% figures, respectively, in the general population of age-matched Framingham women (Ann Rheum Dis. 2011 Sep;70[9]:1581-6).

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

LAS VEGAS – Patients with Sjögren’s syndrome do not have an increased prevalence of hand osteoarthritis, but they are strongly predisposed to have a history of hypothyroidism, Jeremie Sellam, MD, reported at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

Both of these findings in his small case-control study were unexpected, he added at the congress sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

The study included 34 women with primary Sjögren’s syndrome according to the 2002 American-European Consensus Group criteria and 54 female controls with sicca syndrome but no autoantibodies and no Sjögren’s syndrome. All subjects were evaluated at a specialized tertiary Sjögren’s syndrome clinic. The controls were referred there to ascertain whether they had Sjögren’s syndrome.

Among the Sjögren’s syndrome patients, 41% had radiographic evidence of hand osteoarthritis, 12% had symptomatic hand osteoarthritis, and 9% had erosive hand osteoarthritis. In the sicca syndrome–only patients, the rates were similar at 52%, 28%, and 9%, respectively.

Looking for commonalities and differences between the Sjögren’s syndrome patients and controls, Dr. Sellam and his coinvestigators noted that the Sjögren’s syndrome patients were significantly older, with an average age of 64 years, compared with 48.5 years in the controls.

Impressively, two-thirds of the 15 Sjögren’s syndrome patients with hand osteoarthritis had a history of hypothyroidism, compared with just 15% of the 27 non-autoimmune sicca syndrome patients with hand osteoarthritis and one-quarter of the Sjögren’s syndrome patients without hand osteoarthritis. This suggests a possible interaction between Sjögren’s syndrome, hand osteoarthritis, and a history of hypothyroidism which merits further study, according to the rheumatologist.

Because of the relatively small patient numbers in the French study, Dr. Sellam and coworkers ran a crosscheck with data from the Framingham Osteoarthritis Study and found hand osteoarthritis prevalence rates comparable to their own findings. For example, the prevalences of radiographic and erosive hand osteoarthritis in the French Sjögren’s syndrome and non-autoimmune sicca syndrome groups were similar to the 44% and 10% figures, respectively, in the general population of age-matched Framingham women (Ann Rheum Dis. 2011 Sep;70[9]:1581-6).

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

AT OARSI 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Nine percent of women with Sjögren’s syndrome had erosive hand osteoarthritis, a prevalence identical to that in a group with non-autoimmune sicca syndrome only.

Data source: This case-control study included 34 women with Sjögren’s syndrome and 54 women with non-autoimmune sicca syndrome.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

Adalimumab strikes out for hand osteoarthritis

LAS VEGAS – Adalimumab proved no better than placebo for the treatment of erosive hand osteoarthritis in the double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized HUMOR trial, throwing cold water on hopes that a disease-modifying treatment for osteoarthritis might at long last have been found.

“This randomized controlled trial demonstrated that subcutaneous adalimumab at 40 mg every other week was no different from placebo for alleviation of pain, synovitis, or bone marrow lesions in patients with erosive hand osteoarthritis presenting with MRI-detected synovitis. This suggests that pain and inflammation are not responsive to TNF [tumor necrosis factor] inhibition in this patient population,” Dawn Aitken, PhD, declared at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

The primary endpoint was change in the visual analog pain score over the course of 12 weeks of therapy. Scores dropped by an average of 3.0 points from a mean baseline of 63.6 with adalimumab and by 0.7 points with placebo. That between-group difference wasn’t statistically significant, nor were those modest reductions clinically meaningful. By convention, a clinically meaningful treatment result requires at least a 15-point improvement on the self-assessed pain scale, noted Dr. Aitken of the University of Tasmania in Hobart, Australia.

It made no difference which treatment arm came first.

“There was absolutely no placebo effect,” she said.

The study proved negative for all prespecified secondary endpoints, too. These included change in the Australian/Canadian Hand OA Index pain, function, and stiffness subscales, as well as change in bone marrow lesions and synovitis. A mere 12% of patients showed improvement in synovitis scores with adalimumab, as did 10% on placebo. Five percent of the adalimumab group and 7% on placebo showed improvement in bone marrow lesion scores.

The proinflammatory cytokine TNF-alpha has been shown to play a key role in OA development and progression. However, several prior studies failed to show a benefit for anti-TNF therapy in terms of reducing pain in hand OA patients, although in one of those negative studies, a post hoc analysis found that adalimumab halted erosive progression in the subset of interphalangeal joints with palpable soft tissue swelling at baseline (Ann Rheum Dis. 2012 Jun;71[6]:891-8).

However, there was a positive signal: In a subgroup analysis confined to the patients with inflammatory joints, the use of etanercept was associated with less structural damage of those joints over time as assessed using the quantitative Ghent University Scoring System, or GUSS, according to Dr. Kloppenburg, professor of rheumatology at Leiden (the Netherlands) University.

The emphatically negative results of the HUMOR trial were greeted with dismay by several disappointed audience members. They raised questions: Might a study featuring more than 12 weeks of treatment have brought positive results? How about a larger study? Why no placebo effect, given that patients were receiving injections? Is this area of investigation of TNF-inhibitor therapy now a dead end? Or could adalimumab and etanercept have differential efficacy in hand OA, even though they are both TNF inhibitors?

Dr. Aitken had an answer for every question.

“I think our study was big enough based on our power calculations to detect a difference of 15 mm on a visual analog scale, which is a clinically important difference. And that’s what we should be chasing in OA, that big effect. Patients are not going to be interested in a treatment that improves their pain by 5 mm,” she said.

As for the possibility that 12 weeks of adalimumab might have been too short to see a treatment effect, Dr. Aitken noted that anti-TNF therapy in rheumatoid arthritis brings a rapid response.

“Ideally, if you did have a disease-modifying drug for osteoarthritis you would want it to have a relatively quick response for pain; if patients aren’t seeing an effect after 3 months they might be less interested in taking it,” she continued.

Also, studies with a crossover design, like HUMOR, are known to have a much smaller placebo effect because patients know that at some point they’re certain to receive the active agent, Dr. Aitken observed.

As for the possibility that etanercept might be effective for erosive hand OA, while adalimumab is not, one physician commented, “That’s really scraping the bottom of the barrel.”

The HUMOR trial was sponsored by AbbVie. Dr. Aitken reported having no financial conflicts.

LAS VEGAS – Adalimumab proved no better than placebo for the treatment of erosive hand osteoarthritis in the double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized HUMOR trial, throwing cold water on hopes that a disease-modifying treatment for osteoarthritis might at long last have been found.

“This randomized controlled trial demonstrated that subcutaneous adalimumab at 40 mg every other week was no different from placebo for alleviation of pain, synovitis, or bone marrow lesions in patients with erosive hand osteoarthritis presenting with MRI-detected synovitis. This suggests that pain and inflammation are not responsive to TNF [tumor necrosis factor] inhibition in this patient population,” Dawn Aitken, PhD, declared at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

The primary endpoint was change in the visual analog pain score over the course of 12 weeks of therapy. Scores dropped by an average of 3.0 points from a mean baseline of 63.6 with adalimumab and by 0.7 points with placebo. That between-group difference wasn’t statistically significant, nor were those modest reductions clinically meaningful. By convention, a clinically meaningful treatment result requires at least a 15-point improvement on the self-assessed pain scale, noted Dr. Aitken of the University of Tasmania in Hobart, Australia.

It made no difference which treatment arm came first.

“There was absolutely no placebo effect,” she said.

The study proved negative for all prespecified secondary endpoints, too. These included change in the Australian/Canadian Hand OA Index pain, function, and stiffness subscales, as well as change in bone marrow lesions and synovitis. A mere 12% of patients showed improvement in synovitis scores with adalimumab, as did 10% on placebo. Five percent of the adalimumab group and 7% on placebo showed improvement in bone marrow lesion scores.

The proinflammatory cytokine TNF-alpha has been shown to play a key role in OA development and progression. However, several prior studies failed to show a benefit for anti-TNF therapy in terms of reducing pain in hand OA patients, although in one of those negative studies, a post hoc analysis found that adalimumab halted erosive progression in the subset of interphalangeal joints with palpable soft tissue swelling at baseline (Ann Rheum Dis. 2012 Jun;71[6]:891-8).

However, there was a positive signal: In a subgroup analysis confined to the patients with inflammatory joints, the use of etanercept was associated with less structural damage of those joints over time as assessed using the quantitative Ghent University Scoring System, or GUSS, according to Dr. Kloppenburg, professor of rheumatology at Leiden (the Netherlands) University.

The emphatically negative results of the HUMOR trial were greeted with dismay by several disappointed audience members. They raised questions: Might a study featuring more than 12 weeks of treatment have brought positive results? How about a larger study? Why no placebo effect, given that patients were receiving injections? Is this area of investigation of TNF-inhibitor therapy now a dead end? Or could adalimumab and etanercept have differential efficacy in hand OA, even though they are both TNF inhibitors?

Dr. Aitken had an answer for every question.

“I think our study was big enough based on our power calculations to detect a difference of 15 mm on a visual analog scale, which is a clinically important difference. And that’s what we should be chasing in OA, that big effect. Patients are not going to be interested in a treatment that improves their pain by 5 mm,” she said.

As for the possibility that 12 weeks of adalimumab might have been too short to see a treatment effect, Dr. Aitken noted that anti-TNF therapy in rheumatoid arthritis brings a rapid response.

“Ideally, if you did have a disease-modifying drug for osteoarthritis you would want it to have a relatively quick response for pain; if patients aren’t seeing an effect after 3 months they might be less interested in taking it,” she continued.

Also, studies with a crossover design, like HUMOR, are known to have a much smaller placebo effect because patients know that at some point they’re certain to receive the active agent, Dr. Aitken observed.

As for the possibility that etanercept might be effective for erosive hand OA, while adalimumab is not, one physician commented, “That’s really scraping the bottom of the barrel.”

The HUMOR trial was sponsored by AbbVie. Dr. Aitken reported having no financial conflicts.

LAS VEGAS – Adalimumab proved no better than placebo for the treatment of erosive hand osteoarthritis in the double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized HUMOR trial, throwing cold water on hopes that a disease-modifying treatment for osteoarthritis might at long last have been found.

“This randomized controlled trial demonstrated that subcutaneous adalimumab at 40 mg every other week was no different from placebo for alleviation of pain, synovitis, or bone marrow lesions in patients with erosive hand osteoarthritis presenting with MRI-detected synovitis. This suggests that pain and inflammation are not responsive to TNF [tumor necrosis factor] inhibition in this patient population,” Dawn Aitken, PhD, declared at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

The primary endpoint was change in the visual analog pain score over the course of 12 weeks of therapy. Scores dropped by an average of 3.0 points from a mean baseline of 63.6 with adalimumab and by 0.7 points with placebo. That between-group difference wasn’t statistically significant, nor were those modest reductions clinically meaningful. By convention, a clinically meaningful treatment result requires at least a 15-point improvement on the self-assessed pain scale, noted Dr. Aitken of the University of Tasmania in Hobart, Australia.

It made no difference which treatment arm came first.

“There was absolutely no placebo effect,” she said.

The study proved negative for all prespecified secondary endpoints, too. These included change in the Australian/Canadian Hand OA Index pain, function, and stiffness subscales, as well as change in bone marrow lesions and synovitis. A mere 12% of patients showed improvement in synovitis scores with adalimumab, as did 10% on placebo. Five percent of the adalimumab group and 7% on placebo showed improvement in bone marrow lesion scores.

The proinflammatory cytokine TNF-alpha has been shown to play a key role in OA development and progression. However, several prior studies failed to show a benefit for anti-TNF therapy in terms of reducing pain in hand OA patients, although in one of those negative studies, a post hoc analysis found that adalimumab halted erosive progression in the subset of interphalangeal joints with palpable soft tissue swelling at baseline (Ann Rheum Dis. 2012 Jun;71[6]:891-8).

However, there was a positive signal: In a subgroup analysis confined to the patients with inflammatory joints, the use of etanercept was associated with less structural damage of those joints over time as assessed using the quantitative Ghent University Scoring System, or GUSS, according to Dr. Kloppenburg, professor of rheumatology at Leiden (the Netherlands) University.

The emphatically negative results of the HUMOR trial were greeted with dismay by several disappointed audience members. They raised questions: Might a study featuring more than 12 weeks of treatment have brought positive results? How about a larger study? Why no placebo effect, given that patients were receiving injections? Is this area of investigation of TNF-inhibitor therapy now a dead end? Or could adalimumab and etanercept have differential efficacy in hand OA, even though they are both TNF inhibitors?

Dr. Aitken had an answer for every question.

“I think our study was big enough based on our power calculations to detect a difference of 15 mm on a visual analog scale, which is a clinically important difference. And that’s what we should be chasing in OA, that big effect. Patients are not going to be interested in a treatment that improves their pain by 5 mm,” she said.

As for the possibility that 12 weeks of adalimumab might have been too short to see a treatment effect, Dr. Aitken noted that anti-TNF therapy in rheumatoid arthritis brings a rapid response.

“Ideally, if you did have a disease-modifying drug for osteoarthritis you would want it to have a relatively quick response for pain; if patients aren’t seeing an effect after 3 months they might be less interested in taking it,” she continued.

Also, studies with a crossover design, like HUMOR, are known to have a much smaller placebo effect because patients know that at some point they’re certain to receive the active agent, Dr. Aitken observed.

As for the possibility that etanercept might be effective for erosive hand OA, while adalimumab is not, one physician commented, “That’s really scraping the bottom of the barrel.”

The HUMOR trial was sponsored by AbbVie. Dr. Aitken reported having no financial conflicts.

FROM OARSI 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Scores dropped by an average of 3.0 points from a mean baseline of 63.6 with adalimumab and by 0.7 points with placebo on the primary endpoint of change in the visual analog pain score over the course of 12 weeks.

Data source: The HUMOR trial was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, crossover trial in which 43 participants with erosive hand osteoarthritis received 12 weeks of treatment with adalimumab and 12 weeks of placebo.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by AbbVie. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Novel agent brings clinically meaningful improvements in knee osteoarthritis

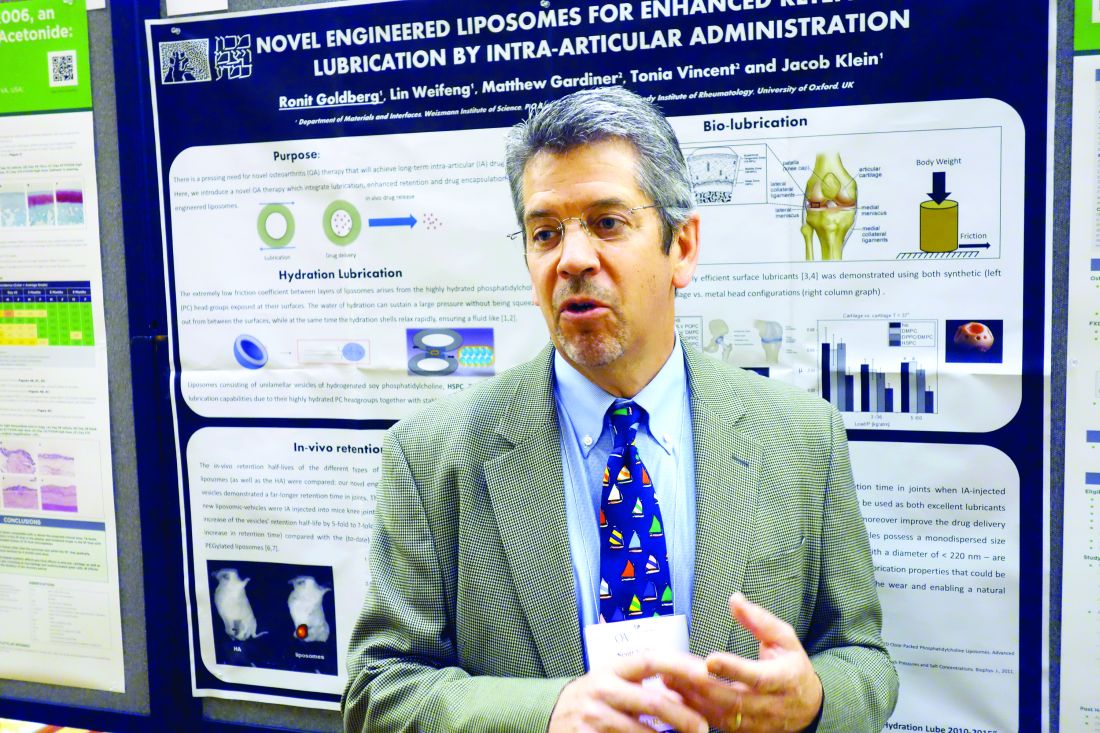

LAS VEGAS – The investigational agent FX006 brought improvements in pain and function in patients with knee osteoarthritis that were not only statistically significant but also clinically meaningful by three different yardsticks, according to Scott Kelley, MD.

FX006 (Zilretta) is an extended-release, microsphere-based formulation of triamcinolone acetonide for intra-articular injection now under review for marketing approval by the Food and Drug Administration, which has said it will render a decision in October, Dr. Kelley reported at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

He presented a post hoc pooled analysis of the 798 patients with knee OA who participated in two phase II randomized, double-blind clinical trials and in an identically designed pivotal phase III trial of a single 40-mg intra-articular injection of FX006. The three studies included 324 patients who got FX006, 212 who received a single 40-mg intra-articular injection of standard triamcinolone acetonide crystalline suspension, and 262 who got a placebo injection of 5 mL of saline.

All participants had radiographically documented symptomatic knee OA with baseline daily pain scores of 6-9 on a 0-10 scale, corresponding to pain in the moderate-to-severe range. Patients telephoned in their average daily pain scores every day during the studies, one of which lasted 12 weeks while the other two ran for 24 weeks. Patients also visited their clinician every 4 weeks for Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) assessments of pain, stiffness, and physical function.

This secondary analysis was undertaken to demonstrate that FX006 distinguishes itself from current nonsurgical treatments for knee OA, which typically achieve clinical effects that are small, transient, and not clinically relevant, Dr. Kelley said at the congress sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

“What’s different about this product formulation is it maintains a prolonged release of triamcinolone acetonide inside the synovial fluid. The pharmacology has demonstrated prolonged residence time in synovial fluid out to at least 12 weeks after intra-articular administration. In addition, it mitigates the peak plasma level after intra-articular administration, so it blunts the level of corticosteroid in plasma and has a lower systemic exposure over time,” he said.

The clinical relevance of the outcomes achieved in the pooled studies was assessed using three different metrics: the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) criteria for determining whether a result represents a minimal clinically important improvement; the Outcomes Measures in Rheumatology–Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OMERACT-OARSI) “strict responder” definition; and the Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT)–defined proportion of patients achieving substantial improvement in pain.

At the 4- and 8-week follow-up visits post injection, only the FX006 group achieved the AAOS threshold of improvement that’s deemed both statistically and clinically significant. Standard triamcinolone couldn’t reach that bar, even at week 4. This makes FX006 the first intra-articular treatment for knee OA to achieve this stringent standard for a clinically meaningful effect. By week 12, the improvement in pain in the FX006 group had slipped to the level of ‘‘statistically and possibly clinically significant.” At weeks 16-24 following a single injection, the FX006 results were no longer statistically or clinically significant.

A significantly greater percentage of the FX006 group met the OMERACT-OARSI strict responder definition of substantial pain improvement at weeks 4, 8, and 12, compared with the standard triamcinolone and placebo groups. The degree of pain improvement in the FX006 group remained superior to placebo through week 16. The OMERACT-OARSI definition of substantial improvement requires at least a 50% improvement in the WOMAC-A pain score plus an absolute improvement of 20 points or more on the WOMAC-A pain score or WOMAC-C physical function 100-point normalized scale.

Substantial clinical improvement as defined by the IMMPACT criteria requires at least a 50% improvement from baseline in the WOMAC-A pain score. Roughly 60% and 50% of the FX006 group met that standard at weeks 4 and 8, respectively, rates that were significantly higher than for standard triamcinolone. The FX006 group’s IMMPACT substantial improvement rate significantly exceeded that of placebo-treated controls throughout all 24 weeks.

These studies as well as the pooled analysis were funded by Flexion Therapeutics.

FX006 is a type of steroid for joint injection that is formulated to stay in the joint longer than typical steroids through the use of microsphere technology. Typical intra-articular steroid injections tend to provide benefit over the short term, and as described by the Cochrane review, the greatest effect is only moderate at 1-2 weeks and decreases from there, with small effects at 13 weeks and none at 26 weeks (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;10:CD005328).

As we have previously reported (Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;43:701-12), intra-articular corticosteroids are widely recommended by professional societies for the management of knee OA, although a specific formulation is not generally given. This compound may fill an important treatment gap by extending the efficacy of a treatment that is generally accepted as useful and safe for this common painful condition. Also, given the controversy surrounding other intra-articular therapies, it may provide a safe and effective alternative for patients who have not benefited from, or not tolerated, one or more traditional intra-articular steroid injection(s).

Amanda E. Nelson, MD, is with the division of rheumatology, allergy, and immunology and the Thurston Arthritis Research Center at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. She is a consultant to GlaxoSmithKline and has received honoraria for online presentations for MedScape and QuantiaMD regarding OA treatment guidelines.

FX006 is a type of steroid for joint injection that is formulated to stay in the joint longer than typical steroids through the use of microsphere technology. Typical intra-articular steroid injections tend to provide benefit over the short term, and as described by the Cochrane review, the greatest effect is only moderate at 1-2 weeks and decreases from there, with small effects at 13 weeks and none at 26 weeks (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;10:CD005328).

As we have previously reported (Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;43:701-12), intra-articular corticosteroids are widely recommended by professional societies for the management of knee OA, although a specific formulation is not generally given. This compound may fill an important treatment gap by extending the efficacy of a treatment that is generally accepted as useful and safe for this common painful condition. Also, given the controversy surrounding other intra-articular therapies, it may provide a safe and effective alternative for patients who have not benefited from, or not tolerated, one or more traditional intra-articular steroid injection(s).

Amanda E. Nelson, MD, is with the division of rheumatology, allergy, and immunology and the Thurston Arthritis Research Center at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. She is a consultant to GlaxoSmithKline and has received honoraria for online presentations for MedScape and QuantiaMD regarding OA treatment guidelines.

FX006 is a type of steroid for joint injection that is formulated to stay in the joint longer than typical steroids through the use of microsphere technology. Typical intra-articular steroid injections tend to provide benefit over the short term, and as described by the Cochrane review, the greatest effect is only moderate at 1-2 weeks and decreases from there, with small effects at 13 weeks and none at 26 weeks (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;10:CD005328).

As we have previously reported (Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;43:701-12), intra-articular corticosteroids are widely recommended by professional societies for the management of knee OA, although a specific formulation is not generally given. This compound may fill an important treatment gap by extending the efficacy of a treatment that is generally accepted as useful and safe for this common painful condition. Also, given the controversy surrounding other intra-articular therapies, it may provide a safe and effective alternative for patients who have not benefited from, or not tolerated, one or more traditional intra-articular steroid injection(s).

Amanda E. Nelson, MD, is with the division of rheumatology, allergy, and immunology and the Thurston Arthritis Research Center at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. She is a consultant to GlaxoSmithKline and has received honoraria for online presentations for MedScape and QuantiaMD regarding OA treatment guidelines.

LAS VEGAS – The investigational agent FX006 brought improvements in pain and function in patients with knee osteoarthritis that were not only statistically significant but also clinically meaningful by three different yardsticks, according to Scott Kelley, MD.

FX006 (Zilretta) is an extended-release, microsphere-based formulation of triamcinolone acetonide for intra-articular injection now under review for marketing approval by the Food and Drug Administration, which has said it will render a decision in October, Dr. Kelley reported at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

He presented a post hoc pooled analysis of the 798 patients with knee OA who participated in two phase II randomized, double-blind clinical trials and in an identically designed pivotal phase III trial of a single 40-mg intra-articular injection of FX006. The three studies included 324 patients who got FX006, 212 who received a single 40-mg intra-articular injection of standard triamcinolone acetonide crystalline suspension, and 262 who got a placebo injection of 5 mL of saline.

All participants had radiographically documented symptomatic knee OA with baseline daily pain scores of 6-9 on a 0-10 scale, corresponding to pain in the moderate-to-severe range. Patients telephoned in their average daily pain scores every day during the studies, one of which lasted 12 weeks while the other two ran for 24 weeks. Patients also visited their clinician every 4 weeks for Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) assessments of pain, stiffness, and physical function.

This secondary analysis was undertaken to demonstrate that FX006 distinguishes itself from current nonsurgical treatments for knee OA, which typically achieve clinical effects that are small, transient, and not clinically relevant, Dr. Kelley said at the congress sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

“What’s different about this product formulation is it maintains a prolonged release of triamcinolone acetonide inside the synovial fluid. The pharmacology has demonstrated prolonged residence time in synovial fluid out to at least 12 weeks after intra-articular administration. In addition, it mitigates the peak plasma level after intra-articular administration, so it blunts the level of corticosteroid in plasma and has a lower systemic exposure over time,” he said.

The clinical relevance of the outcomes achieved in the pooled studies was assessed using three different metrics: the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) criteria for determining whether a result represents a minimal clinically important improvement; the Outcomes Measures in Rheumatology–Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OMERACT-OARSI) “strict responder” definition; and the Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT)–defined proportion of patients achieving substantial improvement in pain.

At the 4- and 8-week follow-up visits post injection, only the FX006 group achieved the AAOS threshold of improvement that’s deemed both statistically and clinically significant. Standard triamcinolone couldn’t reach that bar, even at week 4. This makes FX006 the first intra-articular treatment for knee OA to achieve this stringent standard for a clinically meaningful effect. By week 12, the improvement in pain in the FX006 group had slipped to the level of ‘‘statistically and possibly clinically significant.” At weeks 16-24 following a single injection, the FX006 results were no longer statistically or clinically significant.

A significantly greater percentage of the FX006 group met the OMERACT-OARSI strict responder definition of substantial pain improvement at weeks 4, 8, and 12, compared with the standard triamcinolone and placebo groups. The degree of pain improvement in the FX006 group remained superior to placebo through week 16. The OMERACT-OARSI definition of substantial improvement requires at least a 50% improvement in the WOMAC-A pain score plus an absolute improvement of 20 points or more on the WOMAC-A pain score or WOMAC-C physical function 100-point normalized scale.

Substantial clinical improvement as defined by the IMMPACT criteria requires at least a 50% improvement from baseline in the WOMAC-A pain score. Roughly 60% and 50% of the FX006 group met that standard at weeks 4 and 8, respectively, rates that were significantly higher than for standard triamcinolone. The FX006 group’s IMMPACT substantial improvement rate significantly exceeded that of placebo-treated controls throughout all 24 weeks.

These studies as well as the pooled analysis were funded by Flexion Therapeutics.

LAS VEGAS – The investigational agent FX006 brought improvements in pain and function in patients with knee osteoarthritis that were not only statistically significant but also clinically meaningful by three different yardsticks, according to Scott Kelley, MD.

FX006 (Zilretta) is an extended-release, microsphere-based formulation of triamcinolone acetonide for intra-articular injection now under review for marketing approval by the Food and Drug Administration, which has said it will render a decision in October, Dr. Kelley reported at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

He presented a post hoc pooled analysis of the 798 patients with knee OA who participated in two phase II randomized, double-blind clinical trials and in an identically designed pivotal phase III trial of a single 40-mg intra-articular injection of FX006. The three studies included 324 patients who got FX006, 212 who received a single 40-mg intra-articular injection of standard triamcinolone acetonide crystalline suspension, and 262 who got a placebo injection of 5 mL of saline.

All participants had radiographically documented symptomatic knee OA with baseline daily pain scores of 6-9 on a 0-10 scale, corresponding to pain in the moderate-to-severe range. Patients telephoned in their average daily pain scores every day during the studies, one of which lasted 12 weeks while the other two ran for 24 weeks. Patients also visited their clinician every 4 weeks for Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) assessments of pain, stiffness, and physical function.

This secondary analysis was undertaken to demonstrate that FX006 distinguishes itself from current nonsurgical treatments for knee OA, which typically achieve clinical effects that are small, transient, and not clinically relevant, Dr. Kelley said at the congress sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

“What’s different about this product formulation is it maintains a prolonged release of triamcinolone acetonide inside the synovial fluid. The pharmacology has demonstrated prolonged residence time in synovial fluid out to at least 12 weeks after intra-articular administration. In addition, it mitigates the peak plasma level after intra-articular administration, so it blunts the level of corticosteroid in plasma and has a lower systemic exposure over time,” he said.

The clinical relevance of the outcomes achieved in the pooled studies was assessed using three different metrics: the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) criteria for determining whether a result represents a minimal clinically important improvement; the Outcomes Measures in Rheumatology–Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OMERACT-OARSI) “strict responder” definition; and the Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT)–defined proportion of patients achieving substantial improvement in pain.

At the 4- and 8-week follow-up visits post injection, only the FX006 group achieved the AAOS threshold of improvement that’s deemed both statistically and clinically significant. Standard triamcinolone couldn’t reach that bar, even at week 4. This makes FX006 the first intra-articular treatment for knee OA to achieve this stringent standard for a clinically meaningful effect. By week 12, the improvement in pain in the FX006 group had slipped to the level of ‘‘statistically and possibly clinically significant.” At weeks 16-24 following a single injection, the FX006 results were no longer statistically or clinically significant.

A significantly greater percentage of the FX006 group met the OMERACT-OARSI strict responder definition of substantial pain improvement at weeks 4, 8, and 12, compared with the standard triamcinolone and placebo groups. The degree of pain improvement in the FX006 group remained superior to placebo through week 16. The OMERACT-OARSI definition of substantial improvement requires at least a 50% improvement in the WOMAC-A pain score plus an absolute improvement of 20 points or more on the WOMAC-A pain score or WOMAC-C physical function 100-point normalized scale.

Substantial clinical improvement as defined by the IMMPACT criteria requires at least a 50% improvement from baseline in the WOMAC-A pain score. Roughly 60% and 50% of the FX006 group met that standard at weeks 4 and 8, respectively, rates that were significantly higher than for standard triamcinolone. The FX006 group’s IMMPACT substantial improvement rate significantly exceeded that of placebo-treated controls throughout all 24 weeks.

These studies as well as the pooled analysis were funded by Flexion Therapeutics.

AT OARSI 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The investigational extended-release formulation of triamcinolone, known as FX006 (Zilretta), is the first intra-articular treatment for knee OA to meet the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons’ stringent standard for a clinically meaningful, as opposed to merely statistically significant, effect.

Data source: A post hoc pooled analysis of three randomized, double-blind clinical trials involving nearly 800 patients with knee osteoarthritis.

Disclosures: The pooled analysis was funded by Flexion Therapeutics and presented by a company officer.

Knee osteoarthritis linked to premature mortality

LAS VEGAS – Knee osteoarthritis was independently associated with increased risk of premature mortality in the largest-ever meta-analysis to examine the issue, Kirsten M. Leyland, PhD, reported at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

The meta-analysis used individual patient-level data on 11,954 participants in six prospective observational cohort studies conducted in four countries. The key finding: Subjects with symptomatic and radiographically confirmed knee OA were at 17% greater risk of premature mortality, compared with pain-free, radiographically negative participants, independent of age, sex, and race, according to Dr. Leyland, a musculoskeletal epidemiologist at the University of Oxford (England).

The six prospective cohort studies included in the new analysis are well known in the field of osteoarthritis research: the Framingham (Mass.) Osteoarthritis Study, the Rotterdam (the Netherlands) Study, the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study (MOST), the Johnston County (N.C.) Osteoarthritis Project, the Tasmanian Older Adult Cohort Study, and the Chingford (U.K.) 1000 Women Study. These studies feature 7.4-23.7 years of prospective follow-up.

In an interview, Dr. Leyland said that the current analysis uses all-cause mortality as the outcome because causes of death are recorded differently in the countries where the studies are taking place. It will take several more years for statisticians to harmonize the cause-of-death data and draw definitive conclusions; however, preliminary analysis suggests the causes of premature mortality in the knee OA patients are disproportionately cardiovascular, she added.

Dr. Leyland reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was supported by Arthritis Research UK.

LAS VEGAS – Knee osteoarthritis was independently associated with increased risk of premature mortality in the largest-ever meta-analysis to examine the issue, Kirsten M. Leyland, PhD, reported at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

The meta-analysis used individual patient-level data on 11,954 participants in six prospective observational cohort studies conducted in four countries. The key finding: Subjects with symptomatic and radiographically confirmed knee OA were at 17% greater risk of premature mortality, compared with pain-free, radiographically negative participants, independent of age, sex, and race, according to Dr. Leyland, a musculoskeletal epidemiologist at the University of Oxford (England).

The six prospective cohort studies included in the new analysis are well known in the field of osteoarthritis research: the Framingham (Mass.) Osteoarthritis Study, the Rotterdam (the Netherlands) Study, the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study (MOST), the Johnston County (N.C.) Osteoarthritis Project, the Tasmanian Older Adult Cohort Study, and the Chingford (U.K.) 1000 Women Study. These studies feature 7.4-23.7 years of prospective follow-up.

In an interview, Dr. Leyland said that the current analysis uses all-cause mortality as the outcome because causes of death are recorded differently in the countries where the studies are taking place. It will take several more years for statisticians to harmonize the cause-of-death data and draw definitive conclusions; however, preliminary analysis suggests the causes of premature mortality in the knee OA patients are disproportionately cardiovascular, she added.

Dr. Leyland reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was supported by Arthritis Research UK.

LAS VEGAS – Knee osteoarthritis was independently associated with increased risk of premature mortality in the largest-ever meta-analysis to examine the issue, Kirsten M. Leyland, PhD, reported at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

The meta-analysis used individual patient-level data on 11,954 participants in six prospective observational cohort studies conducted in four countries. The key finding: Subjects with symptomatic and radiographically confirmed knee OA were at 17% greater risk of premature mortality, compared with pain-free, radiographically negative participants, independent of age, sex, and race, according to Dr. Leyland, a musculoskeletal epidemiologist at the University of Oxford (England).

The six prospective cohort studies included in the new analysis are well known in the field of osteoarthritis research: the Framingham (Mass.) Osteoarthritis Study, the Rotterdam (the Netherlands) Study, the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study (MOST), the Johnston County (N.C.) Osteoarthritis Project, the Tasmanian Older Adult Cohort Study, and the Chingford (U.K.) 1000 Women Study. These studies feature 7.4-23.7 years of prospective follow-up.

In an interview, Dr. Leyland said that the current analysis uses all-cause mortality as the outcome because causes of death are recorded differently in the countries where the studies are taking place. It will take several more years for statisticians to harmonize the cause-of-death data and draw definitive conclusions; however, preliminary analysis suggests the causes of premature mortality in the knee OA patients are disproportionately cardiovascular, she added.

Dr. Leyland reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was supported by Arthritis Research UK.

AT OARSI 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Knee osteoarthritis is independently associated with a 17% increased likelihood of premature mortality.

Data source: This meta-analysis harmonized individual patient-level data drawn from six major prospective, population-based cohort studies worldwide.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was supported by Arthritis Research UK.

Short course of prednisolone may help distinguish between RA and hand OA

A short course of prednisolone may help rheumatologists differentiate between patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis, a proof of concept study shows.

However, the investigators caution that a positive response to the 3-day steroid course does not confirm a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

For many years, rheumatologists have been using short courses of prednisolone in unclear clinical situations to differentiate between inflammatory and non-inflammatory arthritis, according to the investigators led by Uta Kiltz, MD, from Rheumazentrum Ruhrgebiet, Herne, Germany.

The pilot part of the TryCort study involved 15 patients with confirmed osteoarthritis and 15 with rheumatoid arthritis who were given 1 g of paracetamol (acetaminophen) a day for 5 days, and on days 3-5, they were given a 20-mg dose of prednisolone (Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19:73. doi: 10.1186/s13075-017-1279-z).

Results showed that the patients with RA had greater improvements in their pain scores (0-10 on a numerical rating scale), compared with OA patients. The mean percentage improvement in pain scores at day 5 was 52.3% in the RA group and 22.0% in the OA group.

The research team considered that a 40% improvement in pain scores was the best choice between sensitivity and specificity regarding a diagnosis of RA.

At this 40% improvement cut-off, the “pred-test” was positive in 11 patients with RA and in four patients with OA (P = .012), with a sensitivity and specificity for a diagnosis of RA of 73.3% for both measures.

In order to validate the test, the researchers enrolled 95 patients with pain in their fingers and hands but without a clear diagnosis. These patients completed the 5-day intervention, and then at week 12 a rheumatologist diagnosed 47 as having RA and 48 were thought to not have RA.

The patients with diagnosed RA had a higher reduction in pain scores during the treatment with prednisolone, compared with patients without RA.

The median percentage of improvement at day 5 was higher in patients with RA than in those without RA (50% [interquartile range, 30%-60%] vs. 20% [IQR, 10%-30%]; P = .001). Overall, 40 of the 95 patients had an improvement of more than 40% in pain levels on day 5, fulfilling the criteria of a positive pred-test.

However, the authors noted that 31 patients with RA had a positive pred-test (77.5%), compared with nine (22.5%) patients without RA (P greater than .001).

The sensitivity of the pred-test for a diagnosis of RA was 0.6 (95% confidence interval, 0.5-0.8) and the specificity was 0.8 (95% CI, 0.7-0.9). The positive and negative predictive values were 0.77 and 0.70, respectively.

The authors concluded that the pred-test “performed well” but not “perfectly well.”

“We are aware that the pred-test without confirmation of other surrogate markers is not helpful in clinical decision-making processes,” they said. “We, therefore, recommend use of the test in light of other confirming factors, such as history, physical examination, imaging, and laboratory results.”

The test could be used to triage patients from primary care to rheumatologist care, they suggested.

The study was financially supported by Rheumazentrum Ruhrgebiet. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A short course of prednisolone may help rheumatologists differentiate between patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis, a proof of concept study shows.

However, the investigators caution that a positive response to the 3-day steroid course does not confirm a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

For many years, rheumatologists have been using short courses of prednisolone in unclear clinical situations to differentiate between inflammatory and non-inflammatory arthritis, according to the investigators led by Uta Kiltz, MD, from Rheumazentrum Ruhrgebiet, Herne, Germany.

The pilot part of the TryCort study involved 15 patients with confirmed osteoarthritis and 15 with rheumatoid arthritis who were given 1 g of paracetamol (acetaminophen) a day for 5 days, and on days 3-5, they were given a 20-mg dose of prednisolone (Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19:73. doi: 10.1186/s13075-017-1279-z).

Results showed that the patients with RA had greater improvements in their pain scores (0-10 on a numerical rating scale), compared with OA patients. The mean percentage improvement in pain scores at day 5 was 52.3% in the RA group and 22.0% in the OA group.

The research team considered that a 40% improvement in pain scores was the best choice between sensitivity and specificity regarding a diagnosis of RA.

At this 40% improvement cut-off, the “pred-test” was positive in 11 patients with RA and in four patients with OA (P = .012), with a sensitivity and specificity for a diagnosis of RA of 73.3% for both measures.

In order to validate the test, the researchers enrolled 95 patients with pain in their fingers and hands but without a clear diagnosis. These patients completed the 5-day intervention, and then at week 12 a rheumatologist diagnosed 47 as having RA and 48 were thought to not have RA.

The patients with diagnosed RA had a higher reduction in pain scores during the treatment with prednisolone, compared with patients without RA.

The median percentage of improvement at day 5 was higher in patients with RA than in those without RA (50% [interquartile range, 30%-60%] vs. 20% [IQR, 10%-30%]; P = .001). Overall, 40 of the 95 patients had an improvement of more than 40% in pain levels on day 5, fulfilling the criteria of a positive pred-test.

However, the authors noted that 31 patients with RA had a positive pred-test (77.5%), compared with nine (22.5%) patients without RA (P greater than .001).

The sensitivity of the pred-test for a diagnosis of RA was 0.6 (95% confidence interval, 0.5-0.8) and the specificity was 0.8 (95% CI, 0.7-0.9). The positive and negative predictive values were 0.77 and 0.70, respectively.

The authors concluded that the pred-test “performed well” but not “perfectly well.”

“We are aware that the pred-test without confirmation of other surrogate markers is not helpful in clinical decision-making processes,” they said. “We, therefore, recommend use of the test in light of other confirming factors, such as history, physical examination, imaging, and laboratory results.”

The test could be used to triage patients from primary care to rheumatologist care, they suggested.

The study was financially supported by Rheumazentrum Ruhrgebiet. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A short course of prednisolone may help rheumatologists differentiate between patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis, a proof of concept study shows.

However, the investigators caution that a positive response to the 3-day steroid course does not confirm a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

For many years, rheumatologists have been using short courses of prednisolone in unclear clinical situations to differentiate between inflammatory and non-inflammatory arthritis, according to the investigators led by Uta Kiltz, MD, from Rheumazentrum Ruhrgebiet, Herne, Germany.

The pilot part of the TryCort study involved 15 patients with confirmed osteoarthritis and 15 with rheumatoid arthritis who were given 1 g of paracetamol (acetaminophen) a day for 5 days, and on days 3-5, they were given a 20-mg dose of prednisolone (Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19:73. doi: 10.1186/s13075-017-1279-z).

Results showed that the patients with RA had greater improvements in their pain scores (0-10 on a numerical rating scale), compared with OA patients. The mean percentage improvement in pain scores at day 5 was 52.3% in the RA group and 22.0% in the OA group.

The research team considered that a 40% improvement in pain scores was the best choice between sensitivity and specificity regarding a diagnosis of RA.

At this 40% improvement cut-off, the “pred-test” was positive in 11 patients with RA and in four patients with OA (P = .012), with a sensitivity and specificity for a diagnosis of RA of 73.3% for both measures.

In order to validate the test, the researchers enrolled 95 patients with pain in their fingers and hands but without a clear diagnosis. These patients completed the 5-day intervention, and then at week 12 a rheumatologist diagnosed 47 as having RA and 48 were thought to not have RA.

The patients with diagnosed RA had a higher reduction in pain scores during the treatment with prednisolone, compared with patients without RA.

The median percentage of improvement at day 5 was higher in patients with RA than in those without RA (50% [interquartile range, 30%-60%] vs. 20% [IQR, 10%-30%]; P = .001). Overall, 40 of the 95 patients had an improvement of more than 40% in pain levels on day 5, fulfilling the criteria of a positive pred-test.

However, the authors noted that 31 patients with RA had a positive pred-test (77.5%), compared with nine (22.5%) patients without RA (P greater than .001).

The sensitivity of the pred-test for a diagnosis of RA was 0.6 (95% confidence interval, 0.5-0.8) and the specificity was 0.8 (95% CI, 0.7-0.9). The positive and negative predictive values were 0.77 and 0.70, respectively.

The authors concluded that the pred-test “performed well” but not “perfectly well.”

“We are aware that the pred-test without confirmation of other surrogate markers is not helpful in clinical decision-making processes,” they said. “We, therefore, recommend use of the test in light of other confirming factors, such as history, physical examination, imaging, and laboratory results.”

The test could be used to triage patients from primary care to rheumatologist care, they suggested.

The study was financially supported by Rheumazentrum Ruhrgebiet. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

FROM ARTHRITIS RESEARCH & THERAPY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The sensitivity of the pred-test for a diagnosis of RA was 0.6 (95% CI, 0.5-0.8) and the specificity was 0.8 (95% CI, 0.7-0.9).

Data source: A pilot study of 20 mg of prednisolone for 3 days in 30 patients with established RA or OA followed by a validation study of the test in 95 patients with pain in their fingers and hands but without a clear diagnosis.

Disclosures: The study was financially supported by Rheumazentrum Ruhrgebiet. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Compounding rules challenge practice norms

As new rules about drug compounding get shaped, rheumatologists seek to protect their ability to combine injectable drugs – most commonly a steroid and a local anesthetic – in their own offices.

In a position statement sent to government agencies and members of Congress in February, the American College of Rheumatology voiced concerns that the practice, which it called “critical,” could become a casualty of drug-compounding regulations under revision by the United States Pharmacopeial Convention (USP), a nonprofit group whose standards are enforceable by state and federal regulators.