User login

ASH 2018 coming attractions look at the big picture

In the closest thing the medical world has to movie trailers, the American Society of Hematology held a press conference offering

Shorter R-CHOP regimen for DLBCL

Under the heading “Big Trials, Big Results” will be data from the FLYER trial, a phase 3, randomized, deescalation trial in 592 patients aged 18-60 years with favorable-prognosis diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. The investigators report that both progression-free survival and overall survival with four cycles of R-CHOP (rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone) were noninferior to those for patients treated with six cycles of R-CHOP (abstract 781).

Ibrutinib mastery in CLL

Also on the program are results of a study showing that ibrutinib (Imbruvica), either alone or in combination with rituximab, is associated with superior progression-free survival than bendamustine and rituximab in older patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

The trial, the Alliance North American Intergroup Study A041202 (abstract 6) is the first major trial to pit ibrutinib against the modern standard of immunochemotherapy rather than the older standard of chlorambucil, Dr. Brodsky noted.

Anemia support in beta-thalassemia, MDS

In nonmalignant disease, investigators in the randomized, phase 3 BELIEVE trial are reporting results of their study showing that the first-in-class erythroid maturation agent luspatercept was associated with significant reductions in the need for RBC transfusion in adults with transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia.

The investigators report that the experimental agent was “generally well tolerated” (abstract 163).

“Beyond a proof of principle, [this is] certainly a very exciting advancement in this group of patients who otherwise had very few treatment options,” said Alexis A. Thompson, MD, associate director of equity and minority health at the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University, Chicago, and the current ASH president.

Dr. Thompson also highlighted the MEDALIST trial (abstract 1), a phase 3, randomized study showing that luspatercept significantly reduced transfusion burden, compared with placebo, in patients with anemia caused by very low–, low-, or intermediate-risk myelodysplastic syndrome with ring sideroblasts who require RBC transfusions.

“This group of patients were individuals who were refractory or were not responders or did not tolerate erythropoietic stimulating agents and therefore were requiring regular transfusion,” Dr. Thompson said.

Worth the wait

The late-breaking abstract program was stretched from the usual six abstracts to seven this year because of the unusually high quality of the science, Dr. Brodsky said.

Among these star attractions are results of a phase 3, randomized study of daratumumab (Darzalex) plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone versus lenalidomide-dexamethasone alone for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma who are ineligible for transplant.

The investigators found that adding daratumumab reduced the risk of disease progression or death by close to 50%, supporting the combination as a new standard of care in these patients, according to Thierry Facon, MD, from the Hospital Claude Huriez in Lille, France, and colleagues (abstract LBA-2).

Two other late-breakers deal with CLL. The first, a randomized, phase 3 study of ibrutinib-based therapy versus standard fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab chemoimmunotherapy in younger patients with untreated CLL, found that ibrutinib and rituximab provided significantly better progression-free survival and overall survival (abstract LBA-4).

“These findings have immediate practice-changing implications and establish ibrutinib-based therapy as the most efficacious first-line therapy for patients with CLL,” wrote Tait D. Shanafelt, MD, from Stanford (Calif.) University, and colleagues.

On a less positive note, Australian researchers report their discovery of a recurrent mutation in BCL2 that confers resistance to venetoclax (Venclexta) in patients with progressive CLL (abstract LBA-7).

“This mutation provides new insights into the pathobiology of venetoclax resistance and provides a potential biomarker of impending clinical relapse,” wrote Piers Blombery, MBBS, from the University of Melbourne, and colleagues.

Finally, investigators from children’s hospitals in the United States and Europe report promising findings on the safety and efficacy of emapalumab for the treatment of patients with the rare genetic disorder primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH).

The drug, newly approved by the Food and Drug Administration, was able to control HLH’s hyperinflammatory activity, and allowed a substantial proportion of patients to survive to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, the investigators said (abstract LBA-6).

In the closest thing the medical world has to movie trailers, the American Society of Hematology held a press conference offering

Shorter R-CHOP regimen for DLBCL

Under the heading “Big Trials, Big Results” will be data from the FLYER trial, a phase 3, randomized, deescalation trial in 592 patients aged 18-60 years with favorable-prognosis diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. The investigators report that both progression-free survival and overall survival with four cycles of R-CHOP (rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone) were noninferior to those for patients treated with six cycles of R-CHOP (abstract 781).

Ibrutinib mastery in CLL

Also on the program are results of a study showing that ibrutinib (Imbruvica), either alone or in combination with rituximab, is associated with superior progression-free survival than bendamustine and rituximab in older patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

The trial, the Alliance North American Intergroup Study A041202 (abstract 6) is the first major trial to pit ibrutinib against the modern standard of immunochemotherapy rather than the older standard of chlorambucil, Dr. Brodsky noted.

Anemia support in beta-thalassemia, MDS

In nonmalignant disease, investigators in the randomized, phase 3 BELIEVE trial are reporting results of their study showing that the first-in-class erythroid maturation agent luspatercept was associated with significant reductions in the need for RBC transfusion in adults with transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia.

The investigators report that the experimental agent was “generally well tolerated” (abstract 163).

“Beyond a proof of principle, [this is] certainly a very exciting advancement in this group of patients who otherwise had very few treatment options,” said Alexis A. Thompson, MD, associate director of equity and minority health at the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University, Chicago, and the current ASH president.

Dr. Thompson also highlighted the MEDALIST trial (abstract 1), a phase 3, randomized study showing that luspatercept significantly reduced transfusion burden, compared with placebo, in patients with anemia caused by very low–, low-, or intermediate-risk myelodysplastic syndrome with ring sideroblasts who require RBC transfusions.

“This group of patients were individuals who were refractory or were not responders or did not tolerate erythropoietic stimulating agents and therefore were requiring regular transfusion,” Dr. Thompson said.

Worth the wait

The late-breaking abstract program was stretched from the usual six abstracts to seven this year because of the unusually high quality of the science, Dr. Brodsky said.

Among these star attractions are results of a phase 3, randomized study of daratumumab (Darzalex) plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone versus lenalidomide-dexamethasone alone for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma who are ineligible for transplant.

The investigators found that adding daratumumab reduced the risk of disease progression or death by close to 50%, supporting the combination as a new standard of care in these patients, according to Thierry Facon, MD, from the Hospital Claude Huriez in Lille, France, and colleagues (abstract LBA-2).

Two other late-breakers deal with CLL. The first, a randomized, phase 3 study of ibrutinib-based therapy versus standard fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab chemoimmunotherapy in younger patients with untreated CLL, found that ibrutinib and rituximab provided significantly better progression-free survival and overall survival (abstract LBA-4).

“These findings have immediate practice-changing implications and establish ibrutinib-based therapy as the most efficacious first-line therapy for patients with CLL,” wrote Tait D. Shanafelt, MD, from Stanford (Calif.) University, and colleagues.

On a less positive note, Australian researchers report their discovery of a recurrent mutation in BCL2 that confers resistance to venetoclax (Venclexta) in patients with progressive CLL (abstract LBA-7).

“This mutation provides new insights into the pathobiology of venetoclax resistance and provides a potential biomarker of impending clinical relapse,” wrote Piers Blombery, MBBS, from the University of Melbourne, and colleagues.

Finally, investigators from children’s hospitals in the United States and Europe report promising findings on the safety and efficacy of emapalumab for the treatment of patients with the rare genetic disorder primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH).

The drug, newly approved by the Food and Drug Administration, was able to control HLH’s hyperinflammatory activity, and allowed a substantial proportion of patients to survive to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, the investigators said (abstract LBA-6).

In the closest thing the medical world has to movie trailers, the American Society of Hematology held a press conference offering

Shorter R-CHOP regimen for DLBCL

Under the heading “Big Trials, Big Results” will be data from the FLYER trial, a phase 3, randomized, deescalation trial in 592 patients aged 18-60 years with favorable-prognosis diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. The investigators report that both progression-free survival and overall survival with four cycles of R-CHOP (rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone) were noninferior to those for patients treated with six cycles of R-CHOP (abstract 781).

Ibrutinib mastery in CLL

Also on the program are results of a study showing that ibrutinib (Imbruvica), either alone or in combination with rituximab, is associated with superior progression-free survival than bendamustine and rituximab in older patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

The trial, the Alliance North American Intergroup Study A041202 (abstract 6) is the first major trial to pit ibrutinib against the modern standard of immunochemotherapy rather than the older standard of chlorambucil, Dr. Brodsky noted.

Anemia support in beta-thalassemia, MDS

In nonmalignant disease, investigators in the randomized, phase 3 BELIEVE trial are reporting results of their study showing that the first-in-class erythroid maturation agent luspatercept was associated with significant reductions in the need for RBC transfusion in adults with transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia.

The investigators report that the experimental agent was “generally well tolerated” (abstract 163).

“Beyond a proof of principle, [this is] certainly a very exciting advancement in this group of patients who otherwise had very few treatment options,” said Alexis A. Thompson, MD, associate director of equity and minority health at the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University, Chicago, and the current ASH president.

Dr. Thompson also highlighted the MEDALIST trial (abstract 1), a phase 3, randomized study showing that luspatercept significantly reduced transfusion burden, compared with placebo, in patients with anemia caused by very low–, low-, or intermediate-risk myelodysplastic syndrome with ring sideroblasts who require RBC transfusions.

“This group of patients were individuals who were refractory or were not responders or did not tolerate erythropoietic stimulating agents and therefore were requiring regular transfusion,” Dr. Thompson said.

Worth the wait

The late-breaking abstract program was stretched from the usual six abstracts to seven this year because of the unusually high quality of the science, Dr. Brodsky said.

Among these star attractions are results of a phase 3, randomized study of daratumumab (Darzalex) plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone versus lenalidomide-dexamethasone alone for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma who are ineligible for transplant.

The investigators found that adding daratumumab reduced the risk of disease progression or death by close to 50%, supporting the combination as a new standard of care in these patients, according to Thierry Facon, MD, from the Hospital Claude Huriez in Lille, France, and colleagues (abstract LBA-2).

Two other late-breakers deal with CLL. The first, a randomized, phase 3 study of ibrutinib-based therapy versus standard fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab chemoimmunotherapy in younger patients with untreated CLL, found that ibrutinib and rituximab provided significantly better progression-free survival and overall survival (abstract LBA-4).

“These findings have immediate practice-changing implications and establish ibrutinib-based therapy as the most efficacious first-line therapy for patients with CLL,” wrote Tait D. Shanafelt, MD, from Stanford (Calif.) University, and colleagues.

On a less positive note, Australian researchers report their discovery of a recurrent mutation in BCL2 that confers resistance to venetoclax (Venclexta) in patients with progressive CLL (abstract LBA-7).

“This mutation provides new insights into the pathobiology of venetoclax resistance and provides a potential biomarker of impending clinical relapse,” wrote Piers Blombery, MBBS, from the University of Melbourne, and colleagues.

Finally, investigators from children’s hospitals in the United States and Europe report promising findings on the safety and efficacy of emapalumab for the treatment of patients with the rare genetic disorder primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH).

The drug, newly approved by the Food and Drug Administration, was able to control HLH’s hyperinflammatory activity, and allowed a substantial proportion of patients to survive to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, the investigators said (abstract LBA-6).

Triplet produces ‘unprecedented’ ORR in PI-refractory MM

Phase 2 results suggest a three-drug regimen may improve response rates in patients with proteasome inhibitor (PI)-refractory multiple myeloma (MM).

The combination—nelfinavir, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (NeVd)—produced an objective response rate (ORR) of 65% in this trial.

In comparison, past studies have shown response rates of 24% to 36% in the PI-refractory MM population.1,2,3

“The unprecedented ORR of NeVd observed in this heavily pretreated, multi-refractory setting warrants further investigation to explore the potential of nelfinavir in combination with PIs . . . ,” Christoph Driessen, of Kantonsspital St. Gallen in Switzerland, and his colleagues wrote in a letter to Blood.

The researchers noted that NeVd previously demonstrated activity in a phase 1 trial of MM patients who were refractory to both bortezomib and lenalidomide.

For the phase 2 study (NCT02188537), Dr. Driessen and his colleagues tested NeVd in MM patients who were refractory to their most recent PI-containing regimen and were previously exposed to or intolerant of at least one immunomodulatory drug.

The 34 patients had a median age of 67 (range, 42-82). Sixty-two percent were male, 38% had poor-risk cytogenetics, and most had a performance status of 0 (59%) or 1 (32%).

All patients had received lenalidomide, 47% had prior pomalidomide, 76% had prior high-dose chemotherapy, and 76% had a prior transplant.

All patients were bortezomib-refractory, 79% were refractory to a PI and lenalidomide, 44% were refractory to a PI and pomalidomide, and 38% were refractory to a PI, lenalidomide, and pomalidomide.

In this study, the patients received:

- Nelfinavir at 2500 mg on days 1 to 14 twice daily

- Bortezomib at 1.3 mg/m2 subcutaneously on days 1, 4, 8, and 11

- Dexamethasone at 20 mg orally on days 1 to 2, 4 to 5, 8 to 9, and 11 to 12.

The patients were treated for up to six 21-day cycles. They received a median of 4.5 cycles (range, 1-6).

Results

The ORR was 65%, with 17 partial responses (PRs) and five very good PRs. Three patients had a minimal response, and four had stable disease.

The ORR (PR or better) was:

- 77% in patients with poor-risk cytogenetics

- 67% in patients with fewer than five prior therapies

- 63% in patients with five or more prior therapies

- 70% in patients refractory to bortezomib and lenalidomide

- 60% in patients refractory to bortezomib and pomalidomide

- 62% in patients refractory to bortezomib, lenalidomide, and pomalidomide.

The researchers said the clinical benefit of NeVd may have been underestimated in this trial because patients were only able to receive six cycles of treatment on study due to a lack of external funding support.

“The time course of paraprotein levels also suggests that individual patients might potentially have experienced myeloma control if NeVd had been continued until progression,” the researchers wrote.

Five patients did receive more than six cycles of NeVd on a compassionate-use basis. In all, 27 patients received additional anti-myeloma treatment during follow-up.

The median progression-free survival was 12 weeks for the entire cohort and 16 weeks among patients who achieved a PR or better.

The median overall survival was 12 months, and 17 patients had died as of November 2016.

The researchers said the most common adverse events in this trial were anemia (97%), thrombocytopenia (82%), hypertension (53%), diarrhea (47%), fatigue (38%), and dyspnea (35%).

There were four deaths during treatment—three due to septicemia and one from heart failure. Three of the deaths were associated with underlying pneumonia.

“Although this mortality rate is consistent with the background mortality among patients with heavily pretreated, refractory myeloma, these findings suggest that prophylactic antibiotic therapy should be considered in those with low neutrophil counts and/or advanced age undergoing NeVd treatment,” the researchers wrote.

This work was supported by the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research, the Swiss State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation, the Rising Tide Foundation for Clinical Cancer Research, and the Gateway for Cancer Research.

Most of the researchers declared no competing financial interests, but one reported personal fees from Celgene, Takeda, Amgen, Novartis, and Janssen-Cilag that were unrelated to this trial.

1. Lokhorst HM et al. N Engl J Med. 2015; 373(13):1207-1219.

2. Dimopoulos MA et al. Blood. 2016;128(4): 497-503.

Phase 2 results suggest a three-drug regimen may improve response rates in patients with proteasome inhibitor (PI)-refractory multiple myeloma (MM).

The combination—nelfinavir, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (NeVd)—produced an objective response rate (ORR) of 65% in this trial.

In comparison, past studies have shown response rates of 24% to 36% in the PI-refractory MM population.1,2,3

“The unprecedented ORR of NeVd observed in this heavily pretreated, multi-refractory setting warrants further investigation to explore the potential of nelfinavir in combination with PIs . . . ,” Christoph Driessen, of Kantonsspital St. Gallen in Switzerland, and his colleagues wrote in a letter to Blood.

The researchers noted that NeVd previously demonstrated activity in a phase 1 trial of MM patients who were refractory to both bortezomib and lenalidomide.

For the phase 2 study (NCT02188537), Dr. Driessen and his colleagues tested NeVd in MM patients who were refractory to their most recent PI-containing regimen and were previously exposed to or intolerant of at least one immunomodulatory drug.

The 34 patients had a median age of 67 (range, 42-82). Sixty-two percent were male, 38% had poor-risk cytogenetics, and most had a performance status of 0 (59%) or 1 (32%).

All patients had received lenalidomide, 47% had prior pomalidomide, 76% had prior high-dose chemotherapy, and 76% had a prior transplant.

All patients were bortezomib-refractory, 79% were refractory to a PI and lenalidomide, 44% were refractory to a PI and pomalidomide, and 38% were refractory to a PI, lenalidomide, and pomalidomide.

In this study, the patients received:

- Nelfinavir at 2500 mg on days 1 to 14 twice daily

- Bortezomib at 1.3 mg/m2 subcutaneously on days 1, 4, 8, and 11

- Dexamethasone at 20 mg orally on days 1 to 2, 4 to 5, 8 to 9, and 11 to 12.

The patients were treated for up to six 21-day cycles. They received a median of 4.5 cycles (range, 1-6).

Results

The ORR was 65%, with 17 partial responses (PRs) and five very good PRs. Three patients had a minimal response, and four had stable disease.

The ORR (PR or better) was:

- 77% in patients with poor-risk cytogenetics

- 67% in patients with fewer than five prior therapies

- 63% in patients with five or more prior therapies

- 70% in patients refractory to bortezomib and lenalidomide

- 60% in patients refractory to bortezomib and pomalidomide

- 62% in patients refractory to bortezomib, lenalidomide, and pomalidomide.

The researchers said the clinical benefit of NeVd may have been underestimated in this trial because patients were only able to receive six cycles of treatment on study due to a lack of external funding support.

“The time course of paraprotein levels also suggests that individual patients might potentially have experienced myeloma control if NeVd had been continued until progression,” the researchers wrote.

Five patients did receive more than six cycles of NeVd on a compassionate-use basis. In all, 27 patients received additional anti-myeloma treatment during follow-up.

The median progression-free survival was 12 weeks for the entire cohort and 16 weeks among patients who achieved a PR or better.

The median overall survival was 12 months, and 17 patients had died as of November 2016.

The researchers said the most common adverse events in this trial were anemia (97%), thrombocytopenia (82%), hypertension (53%), diarrhea (47%), fatigue (38%), and dyspnea (35%).

There were four deaths during treatment—three due to septicemia and one from heart failure. Three of the deaths were associated with underlying pneumonia.

“Although this mortality rate is consistent with the background mortality among patients with heavily pretreated, refractory myeloma, these findings suggest that prophylactic antibiotic therapy should be considered in those with low neutrophil counts and/or advanced age undergoing NeVd treatment,” the researchers wrote.

This work was supported by the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research, the Swiss State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation, the Rising Tide Foundation for Clinical Cancer Research, and the Gateway for Cancer Research.

Most of the researchers declared no competing financial interests, but one reported personal fees from Celgene, Takeda, Amgen, Novartis, and Janssen-Cilag that were unrelated to this trial.

1. Lokhorst HM et al. N Engl J Med. 2015; 373(13):1207-1219.

2. Dimopoulos MA et al. Blood. 2016;128(4): 497-503.

Phase 2 results suggest a three-drug regimen may improve response rates in patients with proteasome inhibitor (PI)-refractory multiple myeloma (MM).

The combination—nelfinavir, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (NeVd)—produced an objective response rate (ORR) of 65% in this trial.

In comparison, past studies have shown response rates of 24% to 36% in the PI-refractory MM population.1,2,3

“The unprecedented ORR of NeVd observed in this heavily pretreated, multi-refractory setting warrants further investigation to explore the potential of nelfinavir in combination with PIs . . . ,” Christoph Driessen, of Kantonsspital St. Gallen in Switzerland, and his colleagues wrote in a letter to Blood.

The researchers noted that NeVd previously demonstrated activity in a phase 1 trial of MM patients who were refractory to both bortezomib and lenalidomide.

For the phase 2 study (NCT02188537), Dr. Driessen and his colleagues tested NeVd in MM patients who were refractory to their most recent PI-containing regimen and were previously exposed to or intolerant of at least one immunomodulatory drug.

The 34 patients had a median age of 67 (range, 42-82). Sixty-two percent were male, 38% had poor-risk cytogenetics, and most had a performance status of 0 (59%) or 1 (32%).

All patients had received lenalidomide, 47% had prior pomalidomide, 76% had prior high-dose chemotherapy, and 76% had a prior transplant.

All patients were bortezomib-refractory, 79% were refractory to a PI and lenalidomide, 44% were refractory to a PI and pomalidomide, and 38% were refractory to a PI, lenalidomide, and pomalidomide.

In this study, the patients received:

- Nelfinavir at 2500 mg on days 1 to 14 twice daily

- Bortezomib at 1.3 mg/m2 subcutaneously on days 1, 4, 8, and 11

- Dexamethasone at 20 mg orally on days 1 to 2, 4 to 5, 8 to 9, and 11 to 12.

The patients were treated for up to six 21-day cycles. They received a median of 4.5 cycles (range, 1-6).

Results

The ORR was 65%, with 17 partial responses (PRs) and five very good PRs. Three patients had a minimal response, and four had stable disease.

The ORR (PR or better) was:

- 77% in patients with poor-risk cytogenetics

- 67% in patients with fewer than five prior therapies

- 63% in patients with five or more prior therapies

- 70% in patients refractory to bortezomib and lenalidomide

- 60% in patients refractory to bortezomib and pomalidomide

- 62% in patients refractory to bortezomib, lenalidomide, and pomalidomide.

The researchers said the clinical benefit of NeVd may have been underestimated in this trial because patients were only able to receive six cycles of treatment on study due to a lack of external funding support.

“The time course of paraprotein levels also suggests that individual patients might potentially have experienced myeloma control if NeVd had been continued until progression,” the researchers wrote.

Five patients did receive more than six cycles of NeVd on a compassionate-use basis. In all, 27 patients received additional anti-myeloma treatment during follow-up.

The median progression-free survival was 12 weeks for the entire cohort and 16 weeks among patients who achieved a PR or better.

The median overall survival was 12 months, and 17 patients had died as of November 2016.

The researchers said the most common adverse events in this trial were anemia (97%), thrombocytopenia (82%), hypertension (53%), diarrhea (47%), fatigue (38%), and dyspnea (35%).

There were four deaths during treatment—three due to septicemia and one from heart failure. Three of the deaths were associated with underlying pneumonia.

“Although this mortality rate is consistent with the background mortality among patients with heavily pretreated, refractory myeloma, these findings suggest that prophylactic antibiotic therapy should be considered in those with low neutrophil counts and/or advanced age undergoing NeVd treatment,” the researchers wrote.

This work was supported by the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research, the Swiss State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation, the Rising Tide Foundation for Clinical Cancer Research, and the Gateway for Cancer Research.

Most of the researchers declared no competing financial interests, but one reported personal fees from Celgene, Takeda, Amgen, Novartis, and Janssen-Cilag that were unrelated to this trial.

1. Lokhorst HM et al. N Engl J Med. 2015; 373(13):1207-1219.

2. Dimopoulos MA et al. Blood. 2016;128(4): 497-503.

Americans concerned about cost of cancer care

A recent survey suggests Americans are nearly as worried about the cost of a cancer diagnosis as they are about dying from cancer.

The cost of cancer care was a top concern even among people who had no prior experience with cancer.

At the same time, cancer patients/survivors admitted to delaying or forgoing care due to costs, and caregivers reported taking “dramatic” actions to pay for their loved one’s care.

These are findings from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO)’s second annual National Cancer Opinion Survey.

The survey was conducted online by The Harris Poll from July 10, 2018, to August 10, 2018. It included 4,887 U.S. adults age 18 and older—1,001 of whom have or had cancer.

Cost among top concerns

Death and pain/suffering were the top concerns related to a cancer diagnosis. Fifty-four percent of respondents said death would be one of their greatest concerns if they were diagnosed with cancer, and the same percentage rated pain/suffering a top concern.

Forty-four percent of respondents said paying for cancer treatment would be a top concern, and 45% said the same about the financial impact of a cancer diagnosis on their family. When combined, financial issues were a top concern for 57% of respondents.

Paying for treatment was a top concern for:

- 36% of respondents who had/have cancer

- 51% of caregivers

- 43% of people with no prior cancer experience.

The financial impact on family was a top concern for:

- 39% of respondents who had/have cancer

- 55% of caregivers

- 42% of people with no prior cancer experience.

Cutting costs

Sixty-one percent of caregivers surveyed said they or another relative have taken a “dramatic” step to help pay for their loved one’s care, including:

- Dipping into savings accounts (35%)

- Working extra hours (23%)

- Taking an early withdrawal from a retirement account or college fund (14%)

- Postponing retirement (14%)

- Taking out a second mortgage or other type of loan (13%)

- Taking an additional job (13%)

- Selling family heirlooms (9%).

Twenty percent of cancer patients/survivors said they have taken actions to reduce treatment costs, including:

- Delaying scans (7%)

- Skipping or delaying appointments (7%)

- Skipping doses of prescribed treatment (6%)

- Postponing or not filling prescriptions (5%)

- Refusing treatment (3%).

“Patients are right to be concerned about the financial impact of a cancer diagnosis on their families,” said Richard L. Schilsky, MD, ASCO’s chief medical officer.

“It’s clear that high treatment costs are taking a serious toll not only on patients, but also on the people who care for them. If a family member has been diagnosed with cancer, the sole focus should be helping them get well. Instead, Americans are worrying about affording treatment, and, in many cases, they’re making serious personal sacrifices to help pay for their loved ones’ care.”

A recent survey suggests Americans are nearly as worried about the cost of a cancer diagnosis as they are about dying from cancer.

The cost of cancer care was a top concern even among people who had no prior experience with cancer.

At the same time, cancer patients/survivors admitted to delaying or forgoing care due to costs, and caregivers reported taking “dramatic” actions to pay for their loved one’s care.

These are findings from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO)’s second annual National Cancer Opinion Survey.

The survey was conducted online by The Harris Poll from July 10, 2018, to August 10, 2018. It included 4,887 U.S. adults age 18 and older—1,001 of whom have or had cancer.

Cost among top concerns

Death and pain/suffering were the top concerns related to a cancer diagnosis. Fifty-four percent of respondents said death would be one of their greatest concerns if they were diagnosed with cancer, and the same percentage rated pain/suffering a top concern.

Forty-four percent of respondents said paying for cancer treatment would be a top concern, and 45% said the same about the financial impact of a cancer diagnosis on their family. When combined, financial issues were a top concern for 57% of respondents.

Paying for treatment was a top concern for:

- 36% of respondents who had/have cancer

- 51% of caregivers

- 43% of people with no prior cancer experience.

The financial impact on family was a top concern for:

- 39% of respondents who had/have cancer

- 55% of caregivers

- 42% of people with no prior cancer experience.

Cutting costs

Sixty-one percent of caregivers surveyed said they or another relative have taken a “dramatic” step to help pay for their loved one’s care, including:

- Dipping into savings accounts (35%)

- Working extra hours (23%)

- Taking an early withdrawal from a retirement account or college fund (14%)

- Postponing retirement (14%)

- Taking out a second mortgage or other type of loan (13%)

- Taking an additional job (13%)

- Selling family heirlooms (9%).

Twenty percent of cancer patients/survivors said they have taken actions to reduce treatment costs, including:

- Delaying scans (7%)

- Skipping or delaying appointments (7%)

- Skipping doses of prescribed treatment (6%)

- Postponing or not filling prescriptions (5%)

- Refusing treatment (3%).

“Patients are right to be concerned about the financial impact of a cancer diagnosis on their families,” said Richard L. Schilsky, MD, ASCO’s chief medical officer.

“It’s clear that high treatment costs are taking a serious toll not only on patients, but also on the people who care for them. If a family member has been diagnosed with cancer, the sole focus should be helping them get well. Instead, Americans are worrying about affording treatment, and, in many cases, they’re making serious personal sacrifices to help pay for their loved ones’ care.”

A recent survey suggests Americans are nearly as worried about the cost of a cancer diagnosis as they are about dying from cancer.

The cost of cancer care was a top concern even among people who had no prior experience with cancer.

At the same time, cancer patients/survivors admitted to delaying or forgoing care due to costs, and caregivers reported taking “dramatic” actions to pay for their loved one’s care.

These are findings from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO)’s second annual National Cancer Opinion Survey.

The survey was conducted online by The Harris Poll from July 10, 2018, to August 10, 2018. It included 4,887 U.S. adults age 18 and older—1,001 of whom have or had cancer.

Cost among top concerns

Death and pain/suffering were the top concerns related to a cancer diagnosis. Fifty-four percent of respondents said death would be one of their greatest concerns if they were diagnosed with cancer, and the same percentage rated pain/suffering a top concern.

Forty-four percent of respondents said paying for cancer treatment would be a top concern, and 45% said the same about the financial impact of a cancer diagnosis on their family. When combined, financial issues were a top concern for 57% of respondents.

Paying for treatment was a top concern for:

- 36% of respondents who had/have cancer

- 51% of caregivers

- 43% of people with no prior cancer experience.

The financial impact on family was a top concern for:

- 39% of respondents who had/have cancer

- 55% of caregivers

- 42% of people with no prior cancer experience.

Cutting costs

Sixty-one percent of caregivers surveyed said they or another relative have taken a “dramatic” step to help pay for their loved one’s care, including:

- Dipping into savings accounts (35%)

- Working extra hours (23%)

- Taking an early withdrawal from a retirement account or college fund (14%)

- Postponing retirement (14%)

- Taking out a second mortgage or other type of loan (13%)

- Taking an additional job (13%)

- Selling family heirlooms (9%).

Twenty percent of cancer patients/survivors said they have taken actions to reduce treatment costs, including:

- Delaying scans (7%)

- Skipping or delaying appointments (7%)

- Skipping doses of prescribed treatment (6%)

- Postponing or not filling prescriptions (5%)

- Refusing treatment (3%).

“Patients are right to be concerned about the financial impact of a cancer diagnosis on their families,” said Richard L. Schilsky, MD, ASCO’s chief medical officer.

“It’s clear that high treatment costs are taking a serious toll not only on patients, but also on the people who care for them. If a family member has been diagnosed with cancer, the sole focus should be helping them get well. Instead, Americans are worrying about affording treatment, and, in many cases, they’re making serious personal sacrifices to help pay for their loved ones’ care.”

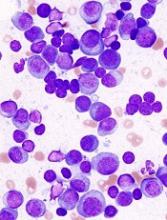

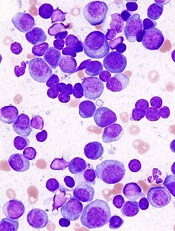

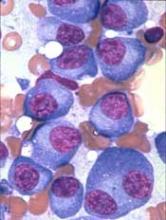

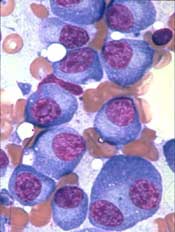

ADAR1 linked to MM pathogenesis, outcomes

Overly zealous editing of messenger RNA in multiple myeloma (MM) cells contributes to MM pathogenesis and is associated with poor outcomes after certain treatments, investigators contend.

The team found evidence to suggest that overexpression of the RNA editing enzyme ADAR1 leads to hyperediting of the MM transcriptome that appears related to a drug-resistant disease phenotype and worse prognosis.

Phaik Ju Teoh, PhD, of the Cancer Science Institute of Singapore, and colleagues reported these findings in Blood.

The investigators implicate aberrant editing of adenosine (A) to inosine (I) in malignant plasma cells and its effects on NEIL1, a gene that encodes proteins involved in base-excision repair of DNA, as important mechanisms in MM pathogenesis.

A to I editing is the most prevalent form of RNA editing in humans, and aberrant editing mediated by ADAR1 has recently been linked to the development of several cancer types, the investigators noted.

To see whether this process may also be involved in MM, the investigators examined whole blood or bone marrow samples from healthy volunteers and MM patients.

The team found that ADAR1 was overexpressed in MM cells compared to nonmalignant plasma cells.

Furthermore, ADAR1 was expressed at higher levels in patients with newly diagnosed or relapsed MM compared to patients who had smoldering myeloma or monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance.

Response to treatment

The investigators also assessed ADAR1 expression in relation to MM patients’ responsiveness to treatment using data from the CoMMpass study.

The team found that patients with poor responses (stable or progressive disease) to bortezomib-based and immunomodulatory-based therapies had high ADAR1 mRNA.

There was no correlation between ADAR1 and responsiveness to carfilzomib-based treatments, but the investigators said this may be because of the relatively lower number of patients who received carfilzomib in this study.

The investigators also found that bortezomib was more effective in inhibiting the growth of MM cells with low ADAR1, and bortezomib-treated cells showed downregulation of ADAR1 expression in a dose- and time-dependent manner.

ADAR1-mediated editing

The investigators determined that ADAR1 directly regulates hyperediting of the MM transcriptome. This was evidenced by a significant increase in A to guanosine (G) editing in newly diagnosed and relapsed MM samples, compared with normal plasma cells.

The team confirmed this finding by observing the effects of ADAR1 levels on editing events across the transcriptome.

The investigators followed this observation with experiments to see whether ADAR1-mediated editing contributes to oncogenesis in MM cells. The MM growth rate slowed when the team silenced ADAR1, and introducing wild-type ADAR1 into cells promoted growth and proliferation.

The investigators also identified NEIL1 as an important ADAR1 editing target in MM. The editing compromised NEIL1’s ability to accurately repair DNA damage.

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation Singapore, the Singapore Ministry of Education, and the National University of Singapore. The investigators reported no competing financial interests.

Overly zealous editing of messenger RNA in multiple myeloma (MM) cells contributes to MM pathogenesis and is associated with poor outcomes after certain treatments, investigators contend.

The team found evidence to suggest that overexpression of the RNA editing enzyme ADAR1 leads to hyperediting of the MM transcriptome that appears related to a drug-resistant disease phenotype and worse prognosis.

Phaik Ju Teoh, PhD, of the Cancer Science Institute of Singapore, and colleagues reported these findings in Blood.

The investigators implicate aberrant editing of adenosine (A) to inosine (I) in malignant plasma cells and its effects on NEIL1, a gene that encodes proteins involved in base-excision repair of DNA, as important mechanisms in MM pathogenesis.

A to I editing is the most prevalent form of RNA editing in humans, and aberrant editing mediated by ADAR1 has recently been linked to the development of several cancer types, the investigators noted.

To see whether this process may also be involved in MM, the investigators examined whole blood or bone marrow samples from healthy volunteers and MM patients.

The team found that ADAR1 was overexpressed in MM cells compared to nonmalignant plasma cells.

Furthermore, ADAR1 was expressed at higher levels in patients with newly diagnosed or relapsed MM compared to patients who had smoldering myeloma or monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance.

Response to treatment

The investigators also assessed ADAR1 expression in relation to MM patients’ responsiveness to treatment using data from the CoMMpass study.

The team found that patients with poor responses (stable or progressive disease) to bortezomib-based and immunomodulatory-based therapies had high ADAR1 mRNA.

There was no correlation between ADAR1 and responsiveness to carfilzomib-based treatments, but the investigators said this may be because of the relatively lower number of patients who received carfilzomib in this study.

The investigators also found that bortezomib was more effective in inhibiting the growth of MM cells with low ADAR1, and bortezomib-treated cells showed downregulation of ADAR1 expression in a dose- and time-dependent manner.

ADAR1-mediated editing

The investigators determined that ADAR1 directly regulates hyperediting of the MM transcriptome. This was evidenced by a significant increase in A to guanosine (G) editing in newly diagnosed and relapsed MM samples, compared with normal plasma cells.

The team confirmed this finding by observing the effects of ADAR1 levels on editing events across the transcriptome.

The investigators followed this observation with experiments to see whether ADAR1-mediated editing contributes to oncogenesis in MM cells. The MM growth rate slowed when the team silenced ADAR1, and introducing wild-type ADAR1 into cells promoted growth and proliferation.

The investigators also identified NEIL1 as an important ADAR1 editing target in MM. The editing compromised NEIL1’s ability to accurately repair DNA damage.

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation Singapore, the Singapore Ministry of Education, and the National University of Singapore. The investigators reported no competing financial interests.

Overly zealous editing of messenger RNA in multiple myeloma (MM) cells contributes to MM pathogenesis and is associated with poor outcomes after certain treatments, investigators contend.

The team found evidence to suggest that overexpression of the RNA editing enzyme ADAR1 leads to hyperediting of the MM transcriptome that appears related to a drug-resistant disease phenotype and worse prognosis.

Phaik Ju Teoh, PhD, of the Cancer Science Institute of Singapore, and colleagues reported these findings in Blood.

The investigators implicate aberrant editing of adenosine (A) to inosine (I) in malignant plasma cells and its effects on NEIL1, a gene that encodes proteins involved in base-excision repair of DNA, as important mechanisms in MM pathogenesis.

A to I editing is the most prevalent form of RNA editing in humans, and aberrant editing mediated by ADAR1 has recently been linked to the development of several cancer types, the investigators noted.

To see whether this process may also be involved in MM, the investigators examined whole blood or bone marrow samples from healthy volunteers and MM patients.

The team found that ADAR1 was overexpressed in MM cells compared to nonmalignant plasma cells.

Furthermore, ADAR1 was expressed at higher levels in patients with newly diagnosed or relapsed MM compared to patients who had smoldering myeloma or monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance.

Response to treatment

The investigators also assessed ADAR1 expression in relation to MM patients’ responsiveness to treatment using data from the CoMMpass study.

The team found that patients with poor responses (stable or progressive disease) to bortezomib-based and immunomodulatory-based therapies had high ADAR1 mRNA.

There was no correlation between ADAR1 and responsiveness to carfilzomib-based treatments, but the investigators said this may be because of the relatively lower number of patients who received carfilzomib in this study.

The investigators also found that bortezomib was more effective in inhibiting the growth of MM cells with low ADAR1, and bortezomib-treated cells showed downregulation of ADAR1 expression in a dose- and time-dependent manner.

ADAR1-mediated editing

The investigators determined that ADAR1 directly regulates hyperediting of the MM transcriptome. This was evidenced by a significant increase in A to guanosine (G) editing in newly diagnosed and relapsed MM samples, compared with normal plasma cells.

The team confirmed this finding by observing the effects of ADAR1 levels on editing events across the transcriptome.

The investigators followed this observation with experiments to see whether ADAR1-mediated editing contributes to oncogenesis in MM cells. The MM growth rate slowed when the team silenced ADAR1, and introducing wild-type ADAR1 into cells promoted growth and proliferation.

The investigators also identified NEIL1 as an important ADAR1 editing target in MM. The editing compromised NEIL1’s ability to accurately repair DNA damage.

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation Singapore, the Singapore Ministry of Education, and the National University of Singapore. The investigators reported no competing financial interests.

Financial burden of blood cancers in the U.S.

An analysis of more than 2,000 U.S. patients with blood cancers revealed an average healthcare cost of almost $157,000 in the first year after diagnosis.

Costs were highest for acute leukemia patients—almost triple the average for all blood cancers.

Out-of-pocket (OOP) costs were initially highest for acute leukemia patients. However, over time, OOP costs became highest for patients with multiple myeloma.

These results are included in a report commissioned by the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society and prepared by the actuarial firm Milliman.

The report is based on data from the Truven Health MarketScan commercial claims databases.

The cost figures are drawn from data for 2,332 patients, ages 18 to 64, who were diagnosed with blood cancer in 2014 and followed through 2016. This includes the following:

- 1,468 patients with lymphoma

- 286 with chronic leukemia

- 282 with multiple myeloma

- 148 with acute leukemia

- 148 with bone marrow disorders (myelodysplastic syndromes).

The average allowed spending—the amount paid by the payer and patient combined—in the first 12 months after diagnosis was:

- $156,845 overall

- $463,414 for acute leukemia

- $213,879 for multiple myeloma

- $133,744 for bone marrow disorders

- $130,545 for lymphoma

- $88,913 for chronic leukemia.

Differences in OOP costs were smaller, although OOP spending was 32% higher for acute leukemia patients than the overall average.

Average OOP costs—which include coinsurance, copay, and deductible—in the first 12 months after diagnosis were:

- $3,877 overall

- $5,147 for acute leukemia

- $4,849 for multiple myeloma

- $3,695 for lymphoma

- $3,480 for chronic leukemia

- $3,336 for bone marrow disorders.

Although OOP costs were initially highest for acute leukemia patients, over time, costs for multiple myeloma patients became the highest.

The average OOP costs in the month of diagnosis were $1,637 for acute leukemia patients and $1,210 for multiple myeloma patients.

The total accumulated OOP costs 3 years after diagnosis were $8,797 for acute leukemia and $9,127 for multiple myeloma. For the other blood cancers, the average 3-year accumulated OOP costs were under $7,800.

The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society received support from Pfizer, Genentech, and Amgen for this work.

An analysis of more than 2,000 U.S. patients with blood cancers revealed an average healthcare cost of almost $157,000 in the first year after diagnosis.

Costs were highest for acute leukemia patients—almost triple the average for all blood cancers.

Out-of-pocket (OOP) costs were initially highest for acute leukemia patients. However, over time, OOP costs became highest for patients with multiple myeloma.

These results are included in a report commissioned by the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society and prepared by the actuarial firm Milliman.

The report is based on data from the Truven Health MarketScan commercial claims databases.

The cost figures are drawn from data for 2,332 patients, ages 18 to 64, who were diagnosed with blood cancer in 2014 and followed through 2016. This includes the following:

- 1,468 patients with lymphoma

- 286 with chronic leukemia

- 282 with multiple myeloma

- 148 with acute leukemia

- 148 with bone marrow disorders (myelodysplastic syndromes).

The average allowed spending—the amount paid by the payer and patient combined—in the first 12 months after diagnosis was:

- $156,845 overall

- $463,414 for acute leukemia

- $213,879 for multiple myeloma

- $133,744 for bone marrow disorders

- $130,545 for lymphoma

- $88,913 for chronic leukemia.

Differences in OOP costs were smaller, although OOP spending was 32% higher for acute leukemia patients than the overall average.

Average OOP costs—which include coinsurance, copay, and deductible—in the first 12 months after diagnosis were:

- $3,877 overall

- $5,147 for acute leukemia

- $4,849 for multiple myeloma

- $3,695 for lymphoma

- $3,480 for chronic leukemia

- $3,336 for bone marrow disorders.

Although OOP costs were initially highest for acute leukemia patients, over time, costs for multiple myeloma patients became the highest.

The average OOP costs in the month of diagnosis were $1,637 for acute leukemia patients and $1,210 for multiple myeloma patients.

The total accumulated OOP costs 3 years after diagnosis were $8,797 for acute leukemia and $9,127 for multiple myeloma. For the other blood cancers, the average 3-year accumulated OOP costs were under $7,800.

The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society received support from Pfizer, Genentech, and Amgen for this work.

An analysis of more than 2,000 U.S. patients with blood cancers revealed an average healthcare cost of almost $157,000 in the first year after diagnosis.

Costs were highest for acute leukemia patients—almost triple the average for all blood cancers.

Out-of-pocket (OOP) costs were initially highest for acute leukemia patients. However, over time, OOP costs became highest for patients with multiple myeloma.

These results are included in a report commissioned by the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society and prepared by the actuarial firm Milliman.

The report is based on data from the Truven Health MarketScan commercial claims databases.

The cost figures are drawn from data for 2,332 patients, ages 18 to 64, who were diagnosed with blood cancer in 2014 and followed through 2016. This includes the following:

- 1,468 patients with lymphoma

- 286 with chronic leukemia

- 282 with multiple myeloma

- 148 with acute leukemia

- 148 with bone marrow disorders (myelodysplastic syndromes).

The average allowed spending—the amount paid by the payer and patient combined—in the first 12 months after diagnosis was:

- $156,845 overall

- $463,414 for acute leukemia

- $213,879 for multiple myeloma

- $133,744 for bone marrow disorders

- $130,545 for lymphoma

- $88,913 for chronic leukemia.

Differences in OOP costs were smaller, although OOP spending was 32% higher for acute leukemia patients than the overall average.

Average OOP costs—which include coinsurance, copay, and deductible—in the first 12 months after diagnosis were:

- $3,877 overall

- $5,147 for acute leukemia

- $4,849 for multiple myeloma

- $3,695 for lymphoma

- $3,480 for chronic leukemia

- $3,336 for bone marrow disorders.

Although OOP costs were initially highest for acute leukemia patients, over time, costs for multiple myeloma patients became the highest.

The average OOP costs in the month of diagnosis were $1,637 for acute leukemia patients and $1,210 for multiple myeloma patients.

The total accumulated OOP costs 3 years after diagnosis were $8,797 for acute leukemia and $9,127 for multiple myeloma. For the other blood cancers, the average 3-year accumulated OOP costs were under $7,800.

The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society received support from Pfizer, Genentech, and Amgen for this work.

Triplet improves PFS in relapsed/refractory MM

Adding elotuzumab to pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone can improve progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (MM), according to the ELOQUENT-3 trial.

These results support the recent U.S. approval of elotuzumab, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone in adults with MM who have received at least two prior therapies, including lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor.

Results from ELOQUENT-3 were recently published in The New England Journal of Medicine and previously presented at the 23rd Congress of the European Hematology Association in June.

The phase 2 trial included patients with refractory or relapsed and refractory MM who had received lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor.

The patients were randomized to receive elotuzumab plus pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone (EPd, n=60) or pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone (Pd, n=57) in 28-day cycles until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

The overall response rate was 53% in the EPd arm and 26% in the Pd arm (odds ratio=3.25; P=0.0029).

There were two stringent complete responses (CRs) and three CRs in the EPd arm, and there was one CR in the Pd arm.

The median duration of response was 8.3 months in the Pd arm and was not reached in the EPd arm.

The median PFS was 10.3 months with EPd and 4.7 months with Pd (hazard ratio=0.54, P=0.008).

Overall survival data were not mature at the time of analysis, but there was a trend favoring EPd over Pd (hazard ratio=0.62). There were 13 deaths in the EPd arm and 18 in the Pd arm.

The most common treatment-related adverse events (in the EPd and Pd arms, respectively) were neutropenia (18% and 20%), hyperglycemia (18% and 11%), and anemia (10% and 15%).

This trial was supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb and AbbVie Biotherapeutics, and researchers reported relationships with several other companies.

Adding elotuzumab to pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone can improve progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (MM), according to the ELOQUENT-3 trial.

These results support the recent U.S. approval of elotuzumab, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone in adults with MM who have received at least two prior therapies, including lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor.

Results from ELOQUENT-3 were recently published in The New England Journal of Medicine and previously presented at the 23rd Congress of the European Hematology Association in June.

The phase 2 trial included patients with refractory or relapsed and refractory MM who had received lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor.

The patients were randomized to receive elotuzumab plus pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone (EPd, n=60) or pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone (Pd, n=57) in 28-day cycles until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

The overall response rate was 53% in the EPd arm and 26% in the Pd arm (odds ratio=3.25; P=0.0029).

There were two stringent complete responses (CRs) and three CRs in the EPd arm, and there was one CR in the Pd arm.

The median duration of response was 8.3 months in the Pd arm and was not reached in the EPd arm.

The median PFS was 10.3 months with EPd and 4.7 months with Pd (hazard ratio=0.54, P=0.008).

Overall survival data were not mature at the time of analysis, but there was a trend favoring EPd over Pd (hazard ratio=0.62). There were 13 deaths in the EPd arm and 18 in the Pd arm.

The most common treatment-related adverse events (in the EPd and Pd arms, respectively) were neutropenia (18% and 20%), hyperglycemia (18% and 11%), and anemia (10% and 15%).

This trial was supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb and AbbVie Biotherapeutics, and researchers reported relationships with several other companies.

Adding elotuzumab to pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone can improve progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (MM), according to the ELOQUENT-3 trial.

These results support the recent U.S. approval of elotuzumab, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone in adults with MM who have received at least two prior therapies, including lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor.

Results from ELOQUENT-3 were recently published in The New England Journal of Medicine and previously presented at the 23rd Congress of the European Hematology Association in June.

The phase 2 trial included patients with refractory or relapsed and refractory MM who had received lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor.

The patients were randomized to receive elotuzumab plus pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone (EPd, n=60) or pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone (Pd, n=57) in 28-day cycles until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

The overall response rate was 53% in the EPd arm and 26% in the Pd arm (odds ratio=3.25; P=0.0029).

There were two stringent complete responses (CRs) and three CRs in the EPd arm, and there was one CR in the Pd arm.

The median duration of response was 8.3 months in the Pd arm and was not reached in the EPd arm.

The median PFS was 10.3 months with EPd and 4.7 months with Pd (hazard ratio=0.54, P=0.008).

Overall survival data were not mature at the time of analysis, but there was a trend favoring EPd over Pd (hazard ratio=0.62). There were 13 deaths in the EPd arm and 18 in the Pd arm.

The most common treatment-related adverse events (in the EPd and Pd arms, respectively) were neutropenia (18% and 20%), hyperglycemia (18% and 11%), and anemia (10% and 15%).

This trial was supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb and AbbVie Biotherapeutics, and researchers reported relationships with several other companies.

P-BCMA-101 gains FDA regenerative medicine designation

(MM), has received the regenerative medicine advanced therapy (RMAT) designation from the Food and Drug Administration.

P-BCMA-101 modifies patients’ T cells using a nonviral DNA modification system known as piggyBac. The modified T cells target cells expressing B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA), which is expressed on essentially all MM cells.

Early results from the phase 1 clinical trial of P-BCMA-101 were recently reported at the 2018 CAR-TCR Summit by Eric Ostertag, MD, PhD, chief executive officer of Poseida Therapeutics, the company developing P-BCMA-101.

Initial results of the trial (NCT03288493) included data on 11 patients with heavily pretreated MM. Patients were a median age of 60, and 73% were high risk. They had a median of six prior therapies.

Patients received conditioning treatment with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide for 3 days prior to receiving P-BCMA-101. They then received one of three doses of CAR T cells – 51×106 (n=3), 152×106 (n=7), or 430×106 (n=1).

The investigators observed no dose-limiting toxicities. Adverse events included neutropenia in eight patients and thrombocytopenia in five.

One patient may have had cytokine release syndrome, but the condition resolved without drug intervention. And investigators observed no neurotoxicity.

Seven of ten patients evaluable for response by International Myeloma Working Group criteria achieved at least a partial response, including very good partial responses and stringent complete response.

The eleventh patient has oligosecretory disease and was only evaluable by PET, which indicated a near-complete response.

Poseida expects to have additional data to report by the end of the year, according to Dr. Ostertag. The study is funded by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine and Poseida Therapeutics.RMAT designation is intended to expedite development and review of regenerative medicines that are intended to treat, modify, reverse, or cure a serious or life-threatening disease or condition.

Preliminary evidence must indicate that the therapy has the potential to address unmet medical needs for the disease or condition. RMAT designation includes all the benefits of fast track and breakthrough therapy designations, including early interactions with the FDA.

(MM), has received the regenerative medicine advanced therapy (RMAT) designation from the Food and Drug Administration.

P-BCMA-101 modifies patients’ T cells using a nonviral DNA modification system known as piggyBac. The modified T cells target cells expressing B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA), which is expressed on essentially all MM cells.

Early results from the phase 1 clinical trial of P-BCMA-101 were recently reported at the 2018 CAR-TCR Summit by Eric Ostertag, MD, PhD, chief executive officer of Poseida Therapeutics, the company developing P-BCMA-101.

Initial results of the trial (NCT03288493) included data on 11 patients with heavily pretreated MM. Patients were a median age of 60, and 73% were high risk. They had a median of six prior therapies.

Patients received conditioning treatment with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide for 3 days prior to receiving P-BCMA-101. They then received one of three doses of CAR T cells – 51×106 (n=3), 152×106 (n=7), or 430×106 (n=1).

The investigators observed no dose-limiting toxicities. Adverse events included neutropenia in eight patients and thrombocytopenia in five.

One patient may have had cytokine release syndrome, but the condition resolved without drug intervention. And investigators observed no neurotoxicity.

Seven of ten patients evaluable for response by International Myeloma Working Group criteria achieved at least a partial response, including very good partial responses and stringent complete response.

The eleventh patient has oligosecretory disease and was only evaluable by PET, which indicated a near-complete response.

Poseida expects to have additional data to report by the end of the year, according to Dr. Ostertag. The study is funded by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine and Poseida Therapeutics.RMAT designation is intended to expedite development and review of regenerative medicines that are intended to treat, modify, reverse, or cure a serious or life-threatening disease or condition.

Preliminary evidence must indicate that the therapy has the potential to address unmet medical needs for the disease or condition. RMAT designation includes all the benefits of fast track and breakthrough therapy designations, including early interactions with the FDA.

(MM), has received the regenerative medicine advanced therapy (RMAT) designation from the Food and Drug Administration.

P-BCMA-101 modifies patients’ T cells using a nonviral DNA modification system known as piggyBac. The modified T cells target cells expressing B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA), which is expressed on essentially all MM cells.

Early results from the phase 1 clinical trial of P-BCMA-101 were recently reported at the 2018 CAR-TCR Summit by Eric Ostertag, MD, PhD, chief executive officer of Poseida Therapeutics, the company developing P-BCMA-101.

Initial results of the trial (NCT03288493) included data on 11 patients with heavily pretreated MM. Patients were a median age of 60, and 73% were high risk. They had a median of six prior therapies.

Patients received conditioning treatment with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide for 3 days prior to receiving P-BCMA-101. They then received one of three doses of CAR T cells – 51×106 (n=3), 152×106 (n=7), or 430×106 (n=1).

The investigators observed no dose-limiting toxicities. Adverse events included neutropenia in eight patients and thrombocytopenia in five.

One patient may have had cytokine release syndrome, but the condition resolved without drug intervention. And investigators observed no neurotoxicity.

Seven of ten patients evaluable for response by International Myeloma Working Group criteria achieved at least a partial response, including very good partial responses and stringent complete response.

The eleventh patient has oligosecretory disease and was only evaluable by PET, which indicated a near-complete response.

Poseida expects to have additional data to report by the end of the year, according to Dr. Ostertag. The study is funded by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine and Poseida Therapeutics.RMAT designation is intended to expedite development and review of regenerative medicines that are intended to treat, modify, reverse, or cure a serious or life-threatening disease or condition.

Preliminary evidence must indicate that the therapy has the potential to address unmet medical needs for the disease or condition. RMAT designation includes all the benefits of fast track and breakthrough therapy designations, including early interactions with the FDA.

CAR T therapy for MM receives RMAT designation

P-BCMA-101, an autologous chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy being developed to treat patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (MM), has received regenerative medicine advanced therapy (RMAT) designation from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

RMAT designation is intended to expedite the development and review of regenerative medicines that are intended to treat, modify, reverse, or cure a serious or life-threatening disease or condition.

For a therapy to receive RMAT designation, preliminary evidence must indicate the therapy has the potential to address unmet medical needs for the disease or condition.

RMAT designation provides all the benefits of fast track and breakthrough therapy designations, including early interactions with the FDA.

About P-BCMA-101

To create P-BCMA-101, patients’ T cells are modified using a non-viral DNA modification system known as piggyBac™. The modified T cells target cells expressing B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA), which is expressed on essentially all MM cells.

Early results from the phase 1 trial (NCT03288493) of P-BCMA-101 were recently reported at the 2018 CAR-TCR Summit by Eric Ostertag, MD, PhD, chief executive officer of Poseida Therapeutics Inc., the company developing P-BCMA-101.

The presentation included data on 11 patients with heavily pretreated MM. Patients were a median age of 60, and 73% were high risk. They had a median of six prior therapies.

Patients received conditioning with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide for 3 days prior to receiving P-BCMA-101. They then received one of three doses of CAR T cells—51×106 (n=3), 152×106 (n=7), or 430×106 (n=1).

The investigators observed no dose-limiting toxicities. Adverse events included neutropenia in eight patients and thrombocytopenia in five.

One patient may have had cytokine release syndrome, but the condition resolved without drug intervention. And investigators observed no neurotoxicity.

Seven of ten patients evaluable for response by International Myeloma Working Group criteria achieved at least a partial response, including very good partial responses and stringent complete response.

The eleventh patient has oligosecretory disease and was only evaluable by PET, which indicated a near complete response.

Additional results from this trial are scheduled to be presented at the 2018 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 1012).

The study is funded by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine and Poseida Therapeutics.

P-BCMA-101, an autologous chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy being developed to treat patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (MM), has received regenerative medicine advanced therapy (RMAT) designation from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

RMAT designation is intended to expedite the development and review of regenerative medicines that are intended to treat, modify, reverse, or cure a serious or life-threatening disease or condition.

For a therapy to receive RMAT designation, preliminary evidence must indicate the therapy has the potential to address unmet medical needs for the disease or condition.

RMAT designation provides all the benefits of fast track and breakthrough therapy designations, including early interactions with the FDA.

About P-BCMA-101

To create P-BCMA-101, patients’ T cells are modified using a non-viral DNA modification system known as piggyBac™. The modified T cells target cells expressing B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA), which is expressed on essentially all MM cells.

Early results from the phase 1 trial (NCT03288493) of P-BCMA-101 were recently reported at the 2018 CAR-TCR Summit by Eric Ostertag, MD, PhD, chief executive officer of Poseida Therapeutics Inc., the company developing P-BCMA-101.

The presentation included data on 11 patients with heavily pretreated MM. Patients were a median age of 60, and 73% were high risk. They had a median of six prior therapies.

Patients received conditioning with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide for 3 days prior to receiving P-BCMA-101. They then received one of three doses of CAR T cells—51×106 (n=3), 152×106 (n=7), or 430×106 (n=1).

The investigators observed no dose-limiting toxicities. Adverse events included neutropenia in eight patients and thrombocytopenia in five.

One patient may have had cytokine release syndrome, but the condition resolved without drug intervention. And investigators observed no neurotoxicity.

Seven of ten patients evaluable for response by International Myeloma Working Group criteria achieved at least a partial response, including very good partial responses and stringent complete response.

The eleventh patient has oligosecretory disease and was only evaluable by PET, which indicated a near complete response.

Additional results from this trial are scheduled to be presented at the 2018 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 1012).

The study is funded by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine and Poseida Therapeutics.

P-BCMA-101, an autologous chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy being developed to treat patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (MM), has received regenerative medicine advanced therapy (RMAT) designation from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

RMAT designation is intended to expedite the development and review of regenerative medicines that are intended to treat, modify, reverse, or cure a serious or life-threatening disease or condition.

For a therapy to receive RMAT designation, preliminary evidence must indicate the therapy has the potential to address unmet medical needs for the disease or condition.

RMAT designation provides all the benefits of fast track and breakthrough therapy designations, including early interactions with the FDA.

About P-BCMA-101

To create P-BCMA-101, patients’ T cells are modified using a non-viral DNA modification system known as piggyBac™. The modified T cells target cells expressing B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA), which is expressed on essentially all MM cells.

Early results from the phase 1 trial (NCT03288493) of P-BCMA-101 were recently reported at the 2018 CAR-TCR Summit by Eric Ostertag, MD, PhD, chief executive officer of Poseida Therapeutics Inc., the company developing P-BCMA-101.

The presentation included data on 11 patients with heavily pretreated MM. Patients were a median age of 60, and 73% were high risk. They had a median of six prior therapies.

Patients received conditioning with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide for 3 days prior to receiving P-BCMA-101. They then received one of three doses of CAR T cells—51×106 (n=3), 152×106 (n=7), or 430×106 (n=1).

The investigators observed no dose-limiting toxicities. Adverse events included neutropenia in eight patients and thrombocytopenia in five.

One patient may have had cytokine release syndrome, but the condition resolved without drug intervention. And investigators observed no neurotoxicity.

Seven of ten patients evaluable for response by International Myeloma Working Group criteria achieved at least a partial response, including very good partial responses and stringent complete response.

The eleventh patient has oligosecretory disease and was only evaluable by PET, which indicated a near complete response.

Additional results from this trial are scheduled to be presented at the 2018 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 1012).

The study is funded by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine and Poseida Therapeutics.

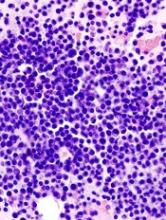

Aberrant RNA editing linked to aggressive myeloma

Overly zealous editing of messenger RNA in multiple myeloma cells appears to contribute to myeloma pathogenesis, and is prognostic of poor outcomes, investigators contend.

Over-expression of RNA editing enzymes in the adenosine deaminases acting on RNA (ADAR) family, specifically ADAR1, lead to hyperediting of the multiple myeloma (MM) transcriptome that in turn appears related to a drug-resistant disease phenotype and worse prognosis, reported Phaik Ju Teoh, PhD, of the Cancer Science Institute of Singapore, and colleagues.

The investigators implicate aberrant editing of adenosine to inosine (A-to-I) in malignant plasma cells, and its effects on NEIL1, a gene that encodes proteins involved in base excision repair of DNA, as important mechanisms in multiple myeloma pathogenesis.

“To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of ADAR1-mediated hypereditome being an independent prognostic factor. The compromised integrity of MM transcriptome drives oncogenic phenotypes, likely contributing to the disease pathogenesis. Our current work, therefore, recognizes the clear biological and clinical importance of A-to-I editing at both the whole-transcriptome and gene-specific level (NEIL1) in MM,” they wrote in Blood.

A-to-I editing is the most prevalent form of RNA editing in humans, and aberrant editing mediated by ADAR1 has recently been linked to the development of several different cancer types, the investigators noted.

To see whether this process may also be involved in multiple myeloma, the investigators examined whole blood or bone marrow samples from healthy volunteers and patients with multiple myeloma.

They first looked at gene-expression profiling in the control and multiple myeloma samples and found that ADAR1 was overexpressed in the multiple myeloma cells, compared with nonmalignant plasma cells. Additionally, they saw that, at the protein level, ADAR1 was expressed at higher levels in patients with newly diagnosed or relapsed disease, compared with patients with smoldering myeloma or monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance.

They next determined that ADAR1 directly regulates hyperediting of the MM transcriptome, evidenced by the observation of a significant increase in A-to-G editing in the newly diagnosed and relapsed myeloma samples, compared with normal plasma cells. They confirmed this finding by observing the effects of ADAR1 levels on editing events across the transcriptome.

The authors followed this observation with experiments to see whether RNA editing by ADAR1 contributes to oncogenesis in myeloma cells. They silenced its expression and found that growth rate slowed and that ADAR1 wild-type protein introduced into cells promoted growth and proliferation.

“As the rescue with mutant ADAR1 is incomplete, we do not discount potential nonediting effects in ADAR1-induced oncogenesis in vivo. Nevertheless, taking into consideration the collective results from both the in vitro and in vivo studies, the RNA editing function of ADAR1 is important for its oncogenic effects in myeloma,” they wrote.

In the final steps, they identified NEIL1 as an important target for editing in multiple myeloma and observed that the editing compromised the ability of the proteins produced by the gene to accurately repair DNA damage.