User login

Condom Catheters versus Indwelling Urethral Catheters in Men: A Prospective, Observational Study

Millions of patients use urinary collection devices. For men, both indwelling and condom-style urinary catheters (known as “external catheters”) are commonly used. National infection prevention guidelines recommend condom catheters as a preferred alternative to indwelling catheters for patients without urinary retention1,2 to reduce the risk of catheter-associated urinary tract infection (UTI). Unfortunately, little outcome data comparing condom catheters with indwelling urethral catheters exists. We therefore assessed the incidence of infectious and noninfectious complications in condom catheter and indwelling urethral catheter users.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Overview

As part of a larger prospective, observational study,3 we compared complications in patients who received a condom catheter during hospitalization with those in patients who received an indwelling urethral catheter. Hospitalized patients with either a condom catheter or indwelling urethral catheter were identified at two Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers and followed for 30 days after initial catheter placement. Patient-reported data were collected during in-person patient interviews at baseline (within three days of catheter placement), and by in-person or phone interviews at 14 days and 30 days postplacement (Supplementary Appendix A and B). Questions were primarily closed-ended, except for a final question inviting open comments. Information about the catheter and any reported complications was also collected from electronic medical record documentation for each patient. Institutional review board approval was received from both participating study sites.

Data Collection and Inclusion Criteria

Hospitalized patients who had a condom or indwelling urethral catheter placed were eligible to participate if they met the following criteria: (1) were hospitalized on an acute care unit; (2) had a new condom catheter or indwelling urethral catheter placed during this hospital stay that was not present on admission; (3) had a device in place for three days or less; (4) were at least 18 years old; and (5) were able to speak English. Patients were excluded if they: (1) did not have the capacity to give consent or participate in the interview/assessment process; (2) refused to provide written informed consent to participate; or (3) had previously participated in this project.

As the larger study was focused on indwelling urethral catheter users, participants with a condom catheter were recruited from only one facility, while those with an indwelling urethral catheter were recruited from both hospitals. Indwelling catheter patients that had a possible contraindication to condom catheter use (such as urinary retention or perioperative use for a surgical procedure) were excluded to make the groups comparable. Any indication for condom catheterization was permitted.

Information about catheter-related complications was collected from two sources: directly from patients and through medical record review. Patients were interviewed at baseline and approximately 14 days and 30 days after catheter placement. The follow-up assessments asked patients about their symptoms and experience over the previous two weeks. We also conducted a medical record review covering the 30 days after initial catheter placement.

Study Measures

Data Analysis

The primary outcome was the percentage of patients who experienced a complication related to a urinary catheter during the 30 days after the catheter was initially placed. Comparisons by group—condom versus indwelling catheter—were conducted using chi-square tests (Fisher’s exact test when necessary) for categorical variables and the Student’s t-test for continuous variables. All analyses were performed using SAS (Cary, North Carolina). All statistical tests were two-sided with alpha set to .05.

RESULTS

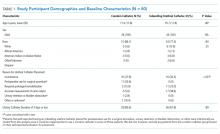

Of the 76 patients invited to participate after having a condom catheter placed, 49 consented (64.5%). Of those, 36 had sufficient data for inclusion in this analysis. The comparison group consisted of 44 patients with an indwelling urethral catheter. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of age, race, or ethnicity (Table 1). There were statistically significant differences in patient-reported reasons for catheter placement, but these were due to the exclusion criteria used for indwelling urethral catheter patients.

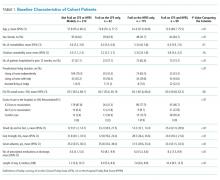

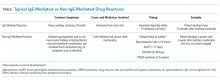

Both patient-reported and clinician-reported (ie, recorded in the patient’s medical record) outcomes are described in Table 2. In total, 80.6% of condom catheter users reported experiencing at least one catheter-related complication during the month after initial catheter placement compared with 88.6% of indwelling catheter users (P = .32). A similar number of condom catheter patients and indwelling urethral catheter patients experienced an infectious complication according to both self-report data (8.3% condom, 6.8% indwelling; P = .99) and medical record review (11.1% condom, 6.8% indwelling; P = .69).

At least one noninfectious complication was identified in 77.8% of condom catheter patients (28 of 36) and 88.6% of indwelling urethral catheter patients (39 of 44) using combined self-report and medical record review data (P = .19); most of these were based on self-reported data. Significantly fewer condom catheter patients reported complications during placement (eg, pain, discomfort, bleeding, or other trauma) compared with those with indwelling catheters (13.9% vs 43.2%, P < .001). Pain, discomfort, bleeding, or other trauma during catheter removal were commonly reported by both condom catheter and indwelling urethral catheter patients (40.9% vs 42.1%, respectively; P = .99).

Patient-reported noninfectious complications were often not documented in the medical record: 75.0% of condom catheter patients and 86.4% of indwelling catheter patients reported complications, in comparison with the 25.0% of condom catheter patients and 27.3% of indwelling urethral catheter patients with noninfectious complications identified during medical record review.

DISCUSSION

Our study revealed three important findings. First, noninfectious complications greatly outnumbered infectious complications, regardless of the device type. Second, condom catheter users reported significantly less pain related to placement of their device compared with the indwelling urethral catheter group. Finally, many patients reported complications that were not documented in the medical record.

The only randomized trial comparing these devices enrolled 75 men hospitalized at a single VA medical center and found that using a condom catheter rather than an indwelling catheter in patients without urinary retention lowered the composite endpoint of bacteriuria, symptomatic UTI, or death.4 Additionally, patients in this trial reported that the condom catheter was significantly more comfortable (90% vs 58%; P = .02) and less painful (5% vs 36%; P = .02) than the indwelling catheter,4 supporting a previous study in hospitalized male Veterans.5

Importantly, we included patient-reported complications that may be of concern to patients but inconsistently documented in the medical record. Pain associated with removal of both condom catheters and indwelling urethral catheters was reported in over 40% in both groups but was not documented in the medical record. One patient with a condom catheter described removal this way: “It got stuck on my hair, so was hard to get off…” Condom catheters also posed some issues with staying in place as has been previously described.6 As one condom catheter user said: “When I was laying down it was okay, but every time I moved around…it would slide off.”

Recent efforts to reduce catheter-associated UTI,7-9 which have focused on reducing the use of indwelling urethral catheters,10,11 have been relatively successful. Clinical policy makers should consider similar efforts to address the noninfectious harms of both catheter types. Such efforts could include further decreasing any type of catheter use along with improved training of those placing such devices.12 Substantial improvement will require a systematic approach to surveilling noninfectious complications of both types of urinary catheters.

Our study has several limitations. First, we conducted the study at two VA hospitals; therefore, the results may not be generalizable to a non-VA population. Second, we only included 80 patients because we recruited a limited number of condom catheter users.

Limitations notwithstanding, we provide comparison data between condom and indwelling urethral catheters. Condom catheter users reported significantly less pain related to initial placement of their device compared with those using an indwelling urethral catheter. For both devices, patients experienced noninfectious complications much more commonly than infectious ones, underscoring the need to systematically address such complications, perhaps through a surveillance system that includes the patient’s perspective. The patient’s voice is important and necessary in view of the apparent underreporting of noninfectious harms in the medical record.

A cknowledgments

Disclaimer

The funding sources played no role in the design, conducting, or evaluation of this study. The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

1. Gould CV, Umscheid CA, Agarwal RK, Kuntz G, Pegues DA, Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Guideline for prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections 2009. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(4):319-326. doi: 10.1086/651091.

2. Lo E, Nicolle LE, Coffin SE, et al. Strategies to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infections in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(5):464-479. doi: 10.1086/675718.

3. Saint S, Trautner BW, Fowler KE, et al. A multicenter study of patient-reported infectious and noninfectious complications associated with indwelling urethral catheters. JAMA Intern Med. 2018. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2417.

4. Saint S, Kaufman SR, Rogers MA, Baker PD, Ossenkop K, Lipsky BA. Condom versus indwelling urinary catheters: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(7):1055-1061. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00785.x.

5. Saint S, Lipsky BA, Baker PD, McDonald LL, Ossenkop K. Urinary catheters: what type do men and their nurses prefer? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(12):1453-1457. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01567.x.

6. Smart C. Male urinary incontinence and the urinary sheath. Br J Nurs. 2014;23(9):S20, S22-S25. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2014.23.Sup9.S20.

7. Saint S, Greene MT, Kowalski CP, Watson SR, Hofer TP, Krein SL. Preventing catheter-associated urinary tract infection in the United States: a national comparative study. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(10):874-879. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.101.

8. Saint S, Greene MT, Krein SL, et al. A program to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infection in acute care. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(22):2111-2119. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504906.

9. Saint S, Fowler KE, Sermak K, et al. Introducing the No preventable harms campaign: creating the safest health care system in the world, starting with catheter-associated urinary tract infection prevention. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43(3):254-259. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.11.016.

10. Fakih MG, Watson SR, Greene MT, et al. Reducing inappropriate urinary catheter use: a statewide effort. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(3):255-260. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.627.

11. Krein SL, Kowalski CP, Harrod M, Forman J, Saint S. Barriers to reducing urinary catheter use: a qualitative assessment of a statewide initiative. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(10):881-886. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.105.

12. Manojlovich M, Saint S, Meddings J, et al. Indwelling urinary catheter insertion practices in the emergency department: an observational study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(1):117-119. doi: 10.1017/ice.2015.238.

13. Meddings JA, Reichert H, Rogers MA, Saint S, Stephansky J, McMahon LF. Effect of nonpayment for hospital-acquired, catheter-associated urinary tract infection: a statewide analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(5):305-312. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-5-201209040-00003.

Millions of patients use urinary collection devices. For men, both indwelling and condom-style urinary catheters (known as “external catheters”) are commonly used. National infection prevention guidelines recommend condom catheters as a preferred alternative to indwelling catheters for patients without urinary retention1,2 to reduce the risk of catheter-associated urinary tract infection (UTI). Unfortunately, little outcome data comparing condom catheters with indwelling urethral catheters exists. We therefore assessed the incidence of infectious and noninfectious complications in condom catheter and indwelling urethral catheter users.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Overview

As part of a larger prospective, observational study,3 we compared complications in patients who received a condom catheter during hospitalization with those in patients who received an indwelling urethral catheter. Hospitalized patients with either a condom catheter or indwelling urethral catheter were identified at two Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers and followed for 30 days after initial catheter placement. Patient-reported data were collected during in-person patient interviews at baseline (within three days of catheter placement), and by in-person or phone interviews at 14 days and 30 days postplacement (Supplementary Appendix A and B). Questions were primarily closed-ended, except for a final question inviting open comments. Information about the catheter and any reported complications was also collected from electronic medical record documentation for each patient. Institutional review board approval was received from both participating study sites.

Data Collection and Inclusion Criteria

Hospitalized patients who had a condom or indwelling urethral catheter placed were eligible to participate if they met the following criteria: (1) were hospitalized on an acute care unit; (2) had a new condom catheter or indwelling urethral catheter placed during this hospital stay that was not present on admission; (3) had a device in place for three days or less; (4) were at least 18 years old; and (5) were able to speak English. Patients were excluded if they: (1) did not have the capacity to give consent or participate in the interview/assessment process; (2) refused to provide written informed consent to participate; or (3) had previously participated in this project.

As the larger study was focused on indwelling urethral catheter users, participants with a condom catheter were recruited from only one facility, while those with an indwelling urethral catheter were recruited from both hospitals. Indwelling catheter patients that had a possible contraindication to condom catheter use (such as urinary retention or perioperative use for a surgical procedure) were excluded to make the groups comparable. Any indication for condom catheterization was permitted.

Information about catheter-related complications was collected from two sources: directly from patients and through medical record review. Patients were interviewed at baseline and approximately 14 days and 30 days after catheter placement. The follow-up assessments asked patients about their symptoms and experience over the previous two weeks. We also conducted a medical record review covering the 30 days after initial catheter placement.

Study Measures

Data Analysis

The primary outcome was the percentage of patients who experienced a complication related to a urinary catheter during the 30 days after the catheter was initially placed. Comparisons by group—condom versus indwelling catheter—were conducted using chi-square tests (Fisher’s exact test when necessary) for categorical variables and the Student’s t-test for continuous variables. All analyses were performed using SAS (Cary, North Carolina). All statistical tests were two-sided with alpha set to .05.

RESULTS

Of the 76 patients invited to participate after having a condom catheter placed, 49 consented (64.5%). Of those, 36 had sufficient data for inclusion in this analysis. The comparison group consisted of 44 patients with an indwelling urethral catheter. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of age, race, or ethnicity (Table 1). There were statistically significant differences in patient-reported reasons for catheter placement, but these were due to the exclusion criteria used for indwelling urethral catheter patients.

Both patient-reported and clinician-reported (ie, recorded in the patient’s medical record) outcomes are described in Table 2. In total, 80.6% of condom catheter users reported experiencing at least one catheter-related complication during the month after initial catheter placement compared with 88.6% of indwelling catheter users (P = .32). A similar number of condom catheter patients and indwelling urethral catheter patients experienced an infectious complication according to both self-report data (8.3% condom, 6.8% indwelling; P = .99) and medical record review (11.1% condom, 6.8% indwelling; P = .69).

At least one noninfectious complication was identified in 77.8% of condom catheter patients (28 of 36) and 88.6% of indwelling urethral catheter patients (39 of 44) using combined self-report and medical record review data (P = .19); most of these were based on self-reported data. Significantly fewer condom catheter patients reported complications during placement (eg, pain, discomfort, bleeding, or other trauma) compared with those with indwelling catheters (13.9% vs 43.2%, P < .001). Pain, discomfort, bleeding, or other trauma during catheter removal were commonly reported by both condom catheter and indwelling urethral catheter patients (40.9% vs 42.1%, respectively; P = .99).

Patient-reported noninfectious complications were often not documented in the medical record: 75.0% of condom catheter patients and 86.4% of indwelling catheter patients reported complications, in comparison with the 25.0% of condom catheter patients and 27.3% of indwelling urethral catheter patients with noninfectious complications identified during medical record review.

DISCUSSION

Our study revealed three important findings. First, noninfectious complications greatly outnumbered infectious complications, regardless of the device type. Second, condom catheter users reported significantly less pain related to placement of their device compared with the indwelling urethral catheter group. Finally, many patients reported complications that were not documented in the medical record.

The only randomized trial comparing these devices enrolled 75 men hospitalized at a single VA medical center and found that using a condom catheter rather than an indwelling catheter in patients without urinary retention lowered the composite endpoint of bacteriuria, symptomatic UTI, or death.4 Additionally, patients in this trial reported that the condom catheter was significantly more comfortable (90% vs 58%; P = .02) and less painful (5% vs 36%; P = .02) than the indwelling catheter,4 supporting a previous study in hospitalized male Veterans.5

Importantly, we included patient-reported complications that may be of concern to patients but inconsistently documented in the medical record. Pain associated with removal of both condom catheters and indwelling urethral catheters was reported in over 40% in both groups but was not documented in the medical record. One patient with a condom catheter described removal this way: “It got stuck on my hair, so was hard to get off…” Condom catheters also posed some issues with staying in place as has been previously described.6 As one condom catheter user said: “When I was laying down it was okay, but every time I moved around…it would slide off.”

Recent efforts to reduce catheter-associated UTI,7-9 which have focused on reducing the use of indwelling urethral catheters,10,11 have been relatively successful. Clinical policy makers should consider similar efforts to address the noninfectious harms of both catheter types. Such efforts could include further decreasing any type of catheter use along with improved training of those placing such devices.12 Substantial improvement will require a systematic approach to surveilling noninfectious complications of both types of urinary catheters.

Our study has several limitations. First, we conducted the study at two VA hospitals; therefore, the results may not be generalizable to a non-VA population. Second, we only included 80 patients because we recruited a limited number of condom catheter users.

Limitations notwithstanding, we provide comparison data between condom and indwelling urethral catheters. Condom catheter users reported significantly less pain related to initial placement of their device compared with those using an indwelling urethral catheter. For both devices, patients experienced noninfectious complications much more commonly than infectious ones, underscoring the need to systematically address such complications, perhaps through a surveillance system that includes the patient’s perspective. The patient’s voice is important and necessary in view of the apparent underreporting of noninfectious harms in the medical record.

A cknowledgments

Disclaimer

The funding sources played no role in the design, conducting, or evaluation of this study. The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Millions of patients use urinary collection devices. For men, both indwelling and condom-style urinary catheters (known as “external catheters”) are commonly used. National infection prevention guidelines recommend condom catheters as a preferred alternative to indwelling catheters for patients without urinary retention1,2 to reduce the risk of catheter-associated urinary tract infection (UTI). Unfortunately, little outcome data comparing condom catheters with indwelling urethral catheters exists. We therefore assessed the incidence of infectious and noninfectious complications in condom catheter and indwelling urethral catheter users.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Overview

As part of a larger prospective, observational study,3 we compared complications in patients who received a condom catheter during hospitalization with those in patients who received an indwelling urethral catheter. Hospitalized patients with either a condom catheter or indwelling urethral catheter were identified at two Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers and followed for 30 days after initial catheter placement. Patient-reported data were collected during in-person patient interviews at baseline (within three days of catheter placement), and by in-person or phone interviews at 14 days and 30 days postplacement (Supplementary Appendix A and B). Questions were primarily closed-ended, except for a final question inviting open comments. Information about the catheter and any reported complications was also collected from electronic medical record documentation for each patient. Institutional review board approval was received from both participating study sites.

Data Collection and Inclusion Criteria

Hospitalized patients who had a condom or indwelling urethral catheter placed were eligible to participate if they met the following criteria: (1) were hospitalized on an acute care unit; (2) had a new condom catheter or indwelling urethral catheter placed during this hospital stay that was not present on admission; (3) had a device in place for three days or less; (4) were at least 18 years old; and (5) were able to speak English. Patients were excluded if they: (1) did not have the capacity to give consent or participate in the interview/assessment process; (2) refused to provide written informed consent to participate; or (3) had previously participated in this project.

As the larger study was focused on indwelling urethral catheter users, participants with a condom catheter were recruited from only one facility, while those with an indwelling urethral catheter were recruited from both hospitals. Indwelling catheter patients that had a possible contraindication to condom catheter use (such as urinary retention or perioperative use for a surgical procedure) were excluded to make the groups comparable. Any indication for condom catheterization was permitted.

Information about catheter-related complications was collected from two sources: directly from patients and through medical record review. Patients were interviewed at baseline and approximately 14 days and 30 days after catheter placement. The follow-up assessments asked patients about their symptoms and experience over the previous two weeks. We also conducted a medical record review covering the 30 days after initial catheter placement.

Study Measures

Data Analysis

The primary outcome was the percentage of patients who experienced a complication related to a urinary catheter during the 30 days after the catheter was initially placed. Comparisons by group—condom versus indwelling catheter—were conducted using chi-square tests (Fisher’s exact test when necessary) for categorical variables and the Student’s t-test for continuous variables. All analyses were performed using SAS (Cary, North Carolina). All statistical tests were two-sided with alpha set to .05.

RESULTS

Of the 76 patients invited to participate after having a condom catheter placed, 49 consented (64.5%). Of those, 36 had sufficient data for inclusion in this analysis. The comparison group consisted of 44 patients with an indwelling urethral catheter. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of age, race, or ethnicity (Table 1). There were statistically significant differences in patient-reported reasons for catheter placement, but these were due to the exclusion criteria used for indwelling urethral catheter patients.

Both patient-reported and clinician-reported (ie, recorded in the patient’s medical record) outcomes are described in Table 2. In total, 80.6% of condom catheter users reported experiencing at least one catheter-related complication during the month after initial catheter placement compared with 88.6% of indwelling catheter users (P = .32). A similar number of condom catheter patients and indwelling urethral catheter patients experienced an infectious complication according to both self-report data (8.3% condom, 6.8% indwelling; P = .99) and medical record review (11.1% condom, 6.8% indwelling; P = .69).

At least one noninfectious complication was identified in 77.8% of condom catheter patients (28 of 36) and 88.6% of indwelling urethral catheter patients (39 of 44) using combined self-report and medical record review data (P = .19); most of these were based on self-reported data. Significantly fewer condom catheter patients reported complications during placement (eg, pain, discomfort, bleeding, or other trauma) compared with those with indwelling catheters (13.9% vs 43.2%, P < .001). Pain, discomfort, bleeding, or other trauma during catheter removal were commonly reported by both condom catheter and indwelling urethral catheter patients (40.9% vs 42.1%, respectively; P = .99).

Patient-reported noninfectious complications were often not documented in the medical record: 75.0% of condom catheter patients and 86.4% of indwelling catheter patients reported complications, in comparison with the 25.0% of condom catheter patients and 27.3% of indwelling urethral catheter patients with noninfectious complications identified during medical record review.

DISCUSSION

Our study revealed three important findings. First, noninfectious complications greatly outnumbered infectious complications, regardless of the device type. Second, condom catheter users reported significantly less pain related to placement of their device compared with the indwelling urethral catheter group. Finally, many patients reported complications that were not documented in the medical record.

The only randomized trial comparing these devices enrolled 75 men hospitalized at a single VA medical center and found that using a condom catheter rather than an indwelling catheter in patients without urinary retention lowered the composite endpoint of bacteriuria, symptomatic UTI, or death.4 Additionally, patients in this trial reported that the condom catheter was significantly more comfortable (90% vs 58%; P = .02) and less painful (5% vs 36%; P = .02) than the indwelling catheter,4 supporting a previous study in hospitalized male Veterans.5

Importantly, we included patient-reported complications that may be of concern to patients but inconsistently documented in the medical record. Pain associated with removal of both condom catheters and indwelling urethral catheters was reported in over 40% in both groups but was not documented in the medical record. One patient with a condom catheter described removal this way: “It got stuck on my hair, so was hard to get off…” Condom catheters also posed some issues with staying in place as has been previously described.6 As one condom catheter user said: “When I was laying down it was okay, but every time I moved around…it would slide off.”

Recent efforts to reduce catheter-associated UTI,7-9 which have focused on reducing the use of indwelling urethral catheters,10,11 have been relatively successful. Clinical policy makers should consider similar efforts to address the noninfectious harms of both catheter types. Such efforts could include further decreasing any type of catheter use along with improved training of those placing such devices.12 Substantial improvement will require a systematic approach to surveilling noninfectious complications of both types of urinary catheters.

Our study has several limitations. First, we conducted the study at two VA hospitals; therefore, the results may not be generalizable to a non-VA population. Second, we only included 80 patients because we recruited a limited number of condom catheter users.

Limitations notwithstanding, we provide comparison data between condom and indwelling urethral catheters. Condom catheter users reported significantly less pain related to initial placement of their device compared with those using an indwelling urethral catheter. For both devices, patients experienced noninfectious complications much more commonly than infectious ones, underscoring the need to systematically address such complications, perhaps through a surveillance system that includes the patient’s perspective. The patient’s voice is important and necessary in view of the apparent underreporting of noninfectious harms in the medical record.

A cknowledgments

Disclaimer

The funding sources played no role in the design, conducting, or evaluation of this study. The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

1. Gould CV, Umscheid CA, Agarwal RK, Kuntz G, Pegues DA, Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Guideline for prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections 2009. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(4):319-326. doi: 10.1086/651091.

2. Lo E, Nicolle LE, Coffin SE, et al. Strategies to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infections in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(5):464-479. doi: 10.1086/675718.

3. Saint S, Trautner BW, Fowler KE, et al. A multicenter study of patient-reported infectious and noninfectious complications associated with indwelling urethral catheters. JAMA Intern Med. 2018. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2417.

4. Saint S, Kaufman SR, Rogers MA, Baker PD, Ossenkop K, Lipsky BA. Condom versus indwelling urinary catheters: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(7):1055-1061. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00785.x.

5. Saint S, Lipsky BA, Baker PD, McDonald LL, Ossenkop K. Urinary catheters: what type do men and their nurses prefer? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(12):1453-1457. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01567.x.

6. Smart C. Male urinary incontinence and the urinary sheath. Br J Nurs. 2014;23(9):S20, S22-S25. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2014.23.Sup9.S20.

7. Saint S, Greene MT, Kowalski CP, Watson SR, Hofer TP, Krein SL. Preventing catheter-associated urinary tract infection in the United States: a national comparative study. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(10):874-879. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.101.

8. Saint S, Greene MT, Krein SL, et al. A program to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infection in acute care. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(22):2111-2119. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504906.

9. Saint S, Fowler KE, Sermak K, et al. Introducing the No preventable harms campaign: creating the safest health care system in the world, starting with catheter-associated urinary tract infection prevention. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43(3):254-259. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.11.016.

10. Fakih MG, Watson SR, Greene MT, et al. Reducing inappropriate urinary catheter use: a statewide effort. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(3):255-260. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.627.

11. Krein SL, Kowalski CP, Harrod M, Forman J, Saint S. Barriers to reducing urinary catheter use: a qualitative assessment of a statewide initiative. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(10):881-886. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.105.

12. Manojlovich M, Saint S, Meddings J, et al. Indwelling urinary catheter insertion practices in the emergency department: an observational study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(1):117-119. doi: 10.1017/ice.2015.238.

13. Meddings JA, Reichert H, Rogers MA, Saint S, Stephansky J, McMahon LF. Effect of nonpayment for hospital-acquired, catheter-associated urinary tract infection: a statewide analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(5):305-312. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-5-201209040-00003.

1. Gould CV, Umscheid CA, Agarwal RK, Kuntz G, Pegues DA, Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Guideline for prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections 2009. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(4):319-326. doi: 10.1086/651091.

2. Lo E, Nicolle LE, Coffin SE, et al. Strategies to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infections in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(5):464-479. doi: 10.1086/675718.

3. Saint S, Trautner BW, Fowler KE, et al. A multicenter study of patient-reported infectious and noninfectious complications associated with indwelling urethral catheters. JAMA Intern Med. 2018. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2417.

4. Saint S, Kaufman SR, Rogers MA, Baker PD, Ossenkop K, Lipsky BA. Condom versus indwelling urinary catheters: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(7):1055-1061. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00785.x.

5. Saint S, Lipsky BA, Baker PD, McDonald LL, Ossenkop K. Urinary catheters: what type do men and their nurses prefer? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(12):1453-1457. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01567.x.

6. Smart C. Male urinary incontinence and the urinary sheath. Br J Nurs. 2014;23(9):S20, S22-S25. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2014.23.Sup9.S20.

7. Saint S, Greene MT, Kowalski CP, Watson SR, Hofer TP, Krein SL. Preventing catheter-associated urinary tract infection in the United States: a national comparative study. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(10):874-879. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.101.

8. Saint S, Greene MT, Krein SL, et al. A program to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infection in acute care. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(22):2111-2119. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504906.

9. Saint S, Fowler KE, Sermak K, et al. Introducing the No preventable harms campaign: creating the safest health care system in the world, starting with catheter-associated urinary tract infection prevention. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43(3):254-259. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.11.016.

10. Fakih MG, Watson SR, Greene MT, et al. Reducing inappropriate urinary catheter use: a statewide effort. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(3):255-260. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.627.

11. Krein SL, Kowalski CP, Harrod M, Forman J, Saint S. Barriers to reducing urinary catheter use: a qualitative assessment of a statewide initiative. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(10):881-886. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.105.

12. Manojlovich M, Saint S, Meddings J, et al. Indwelling urinary catheter insertion practices in the emergency department: an observational study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(1):117-119. doi: 10.1017/ice.2015.238.

13. Meddings JA, Reichert H, Rogers MA, Saint S, Stephansky J, McMahon LF. Effect of nonpayment for hospital-acquired, catheter-associated urinary tract infection: a statewide analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(5):305-312. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-5-201209040-00003.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Prevalence and Postdischarge Outcomes Associated with Frailty in Medical Inpatients: Impact of Different Frailty Definitions

Frailty is associated with adverse outcomes in hospitalized patients, including longer length of stay, increased risk of institutionalization at discharge, and higher rates of readmissions or death postdischarge.1-4 Multiple tools have been developed to evaluate frailty and in an earlier study,4 we compared the three most common of these and demonstrated that the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS)5 was the most useful tool clinically as it was most strongly associated with adverse events in the first 30 days after discharge. However, it must be collected prospectively and requires contact with patients or proxies for the evaluator to assign the patient into one of nine categories depending on their disease state, mobility, cognition, and ability to perform instrumental and functional activities of daily living. Recently, a new score has been described which is based on an administrative data algorithm that assigns points to patients having any of 109 ICD-10 codes listed for their index hospitalization and all hospitalizations in the prior two years and can be generated retrospectively without trained observers.6 Although higher Hospital Frailty Risk Scores (HFRS) were associated with greater risk of postdischarge adverse events, the kappa when compared with the CFS was only 0.30 (95% CI 0.22-0.38) in that study.6 However, as the HFRS was developed and validated in patients aged ≥75 years within the UK National Health Service, the authors themselves recommended that it be evaluated in other healthcare systems, other populations, and with comparison to prospectively collected frailty data from cumulative deficit models such as the CFS.

The aim of this study was to compare frailty assessments using the CFS and the HFRS in a population of adult patients hospitalized on general medical wards in North America to determine the impact on prevalence estimates and prediction of outcomes within the first 30 days after hospital discharge (a timeframe highlighted in the Affordable Care Act and used by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services as an important hospital quality indicator).

METHODS

As described previously,7 we performed a prospective cohort study of adults without cognitive impairment or life expectancy less than three months being discharged back to the community (not to long-term care facilities) from general medical wards in two teaching hospitals in Edmonton, Alberta, between October 2013 and November 2014. All patients provided signed consent, and the University of Alberta Health Research Ethics board (project ID Pro00036880) approved the study.

Trained observers assessed each patient’s frailty status within 24 hours of discharge based on the patient’s best status in the week prior to becoming ill with the reason for the index hospitalization. The research assistant classified patients into one of the following nine CFS categories: very fit, well, managing well, vulnerable, mildly frail (need help with at least one instrumental activities of daily living such as shopping, finances, meal preparation, or housework), moderately frail (need help with one or two activities of daily living such as bathing and dressing), severely frail (dependent for personal care), very severely frail (bedbound), and terminally ill. According to the CFS validation studies, the last five categories were defined as frail for the purposes of our analyses.

Independent of the trained observer’s assessments, we calculated the HFRS for each participant in our cohort by linking to Alberta administrative data holdings within the Alberta Health Services Data Integration and Measurement Reporting unit and examining all diagnostic codes for the index hospitalization and any other hospitalizations in the prior two years for the 109 ICD-10 codes listed in the original HFRS paper and used the same score cutpoints as they reported (HFRS <5 being low risk, 5-15 defined as intermediate risk, and >15 as high risk for frailty; scores ≥5 were defined as frail).6

All patients were followed after discharge by research personnel blinded to the patient’s frailty assessment. We used patient/caregiver self-report and the provincial electronic health record to collect information on all-cause readmissions or mortality within 30 days.

We have previously reported4,7 the association between frailty defined by the CFS and unplanned readmissions or death within 30 days of discharge but in this study, we examined the correlation between CFS-defined frailty and the HFRS score (classifying those with intermediate or high scores as frail) using chance-corrected kappa coefficients. We also compared the prognostic accuracy of both models for predicting death and/or unplanned readmissions within 30 days using the C statistic and the integrated discrimination improvement index and examined patients aged >65 years as a subgroup.8 We used SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) for analyses, with P values of <.05 considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

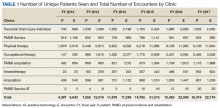

Of the 499 patients in our original cohort,7 we could not link 10 to the administrative data to calculate HFRS, and thus this study sample is only 489 patients (mean age 64 years, 50% women, 52% older than 65 years, a mean of 4.9 comorbidities, and median length of stay five days).

Overall, 276 (56%) patients were deemed frail according to at least one assessment (214 [44%] on the HFRS [35% intermediate risk and 9% high risk] and 161 [33%] on the CFS), and 99 (20%) met both frailty definitions (Appendix Figure). Among the 252 patients aged >65 years, 66 (26%) met both frailty definitions and 166 (66%) were frail according to at least one assessment. Agreement between HFRS and the CFS (kappa 0.24, 95% CI 0.16-0.33) was poor. The CFS definition of frailty was 46% sensitive and 77% specific in classifying frail patients compared with HFRS-defined frailty.

As we reported earlier,4 patients deemed frail were generally similar across scales in that they were older, had more comorbidities, more prescriptions, longer lengths of stay, and poorer quality of life than nonfrail patients (all P < .01, Table 1). However, patients classified as frail on the HFRS only but not meeting the CFS definition were younger, had higher quality of life, and despite a similar Charlson Score and number of comorbidities were much more likely to have been living independently prior to admission than those classified as frail on the CFS.

Death or unplanned readmission within 30 days occurred in 13.3% (65 patients), with most events being readmissions (62, 12.7%). HFRS-defined frail patients exhibited higher 30-day death/readmission rates (16% vs 11% for not frail, P = .08; 14% vs 11% in the elderly, P = .5), which was not statistically significantly different from the nonfrail patients even after adjusting for age and sex (aOR [adjusted odds ratio] 1.62, 95% CI 0.95-2.75 for all adults; aOR 1.24, 95% CI 0.58-2.63 for the elderly). CFS-defined frail patients had significantly higher 30-day readmission/death rates (19% vs 10% for not frail, aOR 2.53, 95% CI 1.40-4.57 for all adults and 21% vs 6% in the elderly, aOR 4.31, 95% CI 1.80-10.31).

Adding the HFRS results to the CFS-based predictive models added little new information, with an integrated discrimination improvement of only 0.009 that was not statistically significant (P = .09, Table 2). In fact, the HFRS was not an independent predictor of postdischarge outcomes after adjusting for age and sex. Although predictive models incorporating the CFS demonstrated the best C statistics, none of the models had high C statistics (ranging between 0.54 and 0.64 for all adults and between 0.55 and 0.68 for those aged >65 years). Even when the frailty definitions were examined as continuous variables, the C statistics were similar as for the dichotomized analyses (0.64 for CFS and 0.58 for HFRS) and the correlation between the two remained weak (Spearman’s correlation coefficient 0.34).

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that the prevalence of frailty in patients being discharged from medical wards was high, with the HFRS (44%) being higher than the CFS (33%), and that only 46% of patients deemed frail on the HFRS were also deemed frail on the CFS. We confirm the report by the developers of the HFRS that there was poor correlation between the CFS cumulative deficit model and the administrative-data-based HFRS model in our cohort, even among those older than 65 years.

Previous studies have reported marked heterogeneity in prevalence estimates between different frailty instruments.2,9 For example, Aguayo et al. found that the prevalence of frailty in the English Longitudinal Study of Aging varied between 0.9% and 68% depending on which of the 35 frailty scales they tested were used, although the prevalence with comprehensive geriatric assessments (the gold standard) was 14.9% (and 15.3% on the CFS).9 Although frail patients are at higher risk for death and/or readmission after discharge, other investigators have also reported similar findings to ours that frailty-based risk models are surprisingly modest at predicting postdischarge readmission or death, with the C statistics ranging between 0.52 and 0.57, although the CFS appears to correlate best with the gold standard of comprehensive geriatric assessment.10-14 This is not surprising since the CFS is multidimensional and as a cumulative deficit model, it incorporates assessment of the patient’s underlying diseases, cognition, function, mobility, and mood in the assignment of their CFS level. Regardless, others15 have pointed out the need for studies such as ours to compare the validity of published frailty scales.

Despite our prospective cohort design and blinded endpoint ascertainment, there are some potential limitations to our study. First, we excluded long-term care residents and patients with foreshortened life expectancy – the frailest of the frail – from our analysis of 30-day outcomes, thereby potentially reducing the magnitude of the association between frailty and adverse outcomes. However, we were interested only in situations where clinicians were faced with equipoise about patient prognosis. Second, we assessed only 30-day readmissions or deaths and cannot comment on the impact of frailty definitions on other postdischarge outcomes (such as discharge locale or need for home care services) or other timeframes. Finally, although the association between the HFRS definition of frailty and the 30-day mortality/readmission was not statistically significant, the 95% confidence intervals were wide and thus we cannot definitively rule out a positive association.

In conclusion, considering that it had the strongest association with postdischarge outcomes and is the fastest and easiest to perform, the most useful of the frailty assessment tools for clinicians at the bedside still appears to be the CFS (both overall and in those patients who are elderly). However, for researchers who are analyzing data retrospectively or policy planners looking at health services data where the CFS was not collected, the HFRS holds promise for risk adjustment in population-level studies comparing processes and outcomes between hospitals.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Miriam Fradette, Debbie Boyko, Sara Belga, Darren Lau, Jenelle Pederson, and Sharry Kahlon for their important contributions in data acquisition in our original cohort study, as well as all the physicians rotating through the general internal medicine wards at the University of Alberta Hospital for their help in identifying the patients. We also thank Dr. Simon Conroy, MB ChB PhD, University of Leicester, UK, for his helpful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. All authors had access to the data and played a role in writing and revising this manuscript.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by an operating grant from Alberta Innovates - Health Solutions. F.A.M. holds the Chair in Cardiovascular Outcomes Research at the Mazankowski Heart Institute, University of Alberta. The authors have no affiliations or financial interests with any organization or entity with a financial interest in the contents of this manuscript.

1. Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):752-762. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9. PubMed

2. Collard RM, Boter H, Schoevers RA, Oude Voshaar RC. Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(8):1487-1492. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04054.x. PubMed

3. de Vries NM, Staal JB, van Ravensberg CD, Hobbelen JS, Olde Rikkert MG, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW. Outcome instruments to measure frailty: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(1):104-114. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.09.001. PubMed

4. Belga S, Majumdar SR, Kahlon S, et al. Comparing three different measures of frailty in medical inpatients: multicenter prospective cohort study examining 30-day risk of readmission or death. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(8):556-562. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2607. PubMed

5. Rockwood K, Andrew M, Mintnitski A. A comparison of two approaches to measuring frailty in elerly people. J Gerontol. 2007;62(7):738-743. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.7.738. PubMed

6. Gilbert T, Neuburger J, Kraindler J, et al. Development and validation of a Hospital Frailty Risk Score focusing on older people in acute care settings using electronic hospital records: an observational study. Lancet. 2018;391(10132):1775-1782. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30668-8Get. PubMed

7. Kahlon S, Pederson J, Majumdar SR, et al. Association between frailty and 30-day outcomes after discharge from hospital. CMAJ. 2015;187(11):799-804. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.150100. PubMed

8. Pencina MJ, D’ Agostino RB, Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the roc curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med. 2008;27(2):157-172. doi: 10.1002/sim.2929.

9. Aguayo GA, Donneau A-F, Vaillant MT, et al. Agreement between 35 published frailty scores in the general population. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186(4):420-434. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx061. PubMed

10. Ritt M, Bollheimer LC, Siever CC, Gaßmann KG. Prediction of one-year mortality by five different frailty instruments: a comparative study in hospitalized geriatric patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;66:66-72. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2016.05.004. PubMed

11. Forti P, Rietti E, Pisacane N, Olivelli V, Maltoni B, Ravaglia G. A comparison of frailty indexes for prediction of adverse health outcomes in a elderly cohort. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;54(1):16-20. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2011.01.007. PubMed

12. Wou F, Gladman JR, Bradshaw L, Franklin M, Edmans J, Conroy SP. The predictive properties of frailty-rating scales in the acute medical unit. Age Ageing. 2013;42(6):776-781. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft055. PubMed

13. Wallis SJ, Wall J, Biram RW, Romero-Ortuno R. Association of the clinical frailty scale with hospital outcomes. QJM. 2015;108(12):943-949. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcv066. PubMed

14. Harmand MGC, Meillon C, Bergua V, et al. Comparing the predictive value of three definitions of frailty: results from the Three-City Study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;72:153-163. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2017.06.005. PubMed

15. Bouillon K, Kivimaki M, Hamer M, et al. Measures of frailty in population-based studies: an overview. BMC Geriatrics. 2013;13(1):64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-13-64. PubMed

Frailty is associated with adverse outcomes in hospitalized patients, including longer length of stay, increased risk of institutionalization at discharge, and higher rates of readmissions or death postdischarge.1-4 Multiple tools have been developed to evaluate frailty and in an earlier study,4 we compared the three most common of these and demonstrated that the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS)5 was the most useful tool clinically as it was most strongly associated with adverse events in the first 30 days after discharge. However, it must be collected prospectively and requires contact with patients or proxies for the evaluator to assign the patient into one of nine categories depending on their disease state, mobility, cognition, and ability to perform instrumental and functional activities of daily living. Recently, a new score has been described which is based on an administrative data algorithm that assigns points to patients having any of 109 ICD-10 codes listed for their index hospitalization and all hospitalizations in the prior two years and can be generated retrospectively without trained observers.6 Although higher Hospital Frailty Risk Scores (HFRS) were associated with greater risk of postdischarge adverse events, the kappa when compared with the CFS was only 0.30 (95% CI 0.22-0.38) in that study.6 However, as the HFRS was developed and validated in patients aged ≥75 years within the UK National Health Service, the authors themselves recommended that it be evaluated in other healthcare systems, other populations, and with comparison to prospectively collected frailty data from cumulative deficit models such as the CFS.

The aim of this study was to compare frailty assessments using the CFS and the HFRS in a population of adult patients hospitalized on general medical wards in North America to determine the impact on prevalence estimates and prediction of outcomes within the first 30 days after hospital discharge (a timeframe highlighted in the Affordable Care Act and used by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services as an important hospital quality indicator).

METHODS

As described previously,7 we performed a prospective cohort study of adults without cognitive impairment or life expectancy less than three months being discharged back to the community (not to long-term care facilities) from general medical wards in two teaching hospitals in Edmonton, Alberta, between October 2013 and November 2014. All patients provided signed consent, and the University of Alberta Health Research Ethics board (project ID Pro00036880) approved the study.

Trained observers assessed each patient’s frailty status within 24 hours of discharge based on the patient’s best status in the week prior to becoming ill with the reason for the index hospitalization. The research assistant classified patients into one of the following nine CFS categories: very fit, well, managing well, vulnerable, mildly frail (need help with at least one instrumental activities of daily living such as shopping, finances, meal preparation, or housework), moderately frail (need help with one or two activities of daily living such as bathing and dressing), severely frail (dependent for personal care), very severely frail (bedbound), and terminally ill. According to the CFS validation studies, the last five categories were defined as frail for the purposes of our analyses.

Independent of the trained observer’s assessments, we calculated the HFRS for each participant in our cohort by linking to Alberta administrative data holdings within the Alberta Health Services Data Integration and Measurement Reporting unit and examining all diagnostic codes for the index hospitalization and any other hospitalizations in the prior two years for the 109 ICD-10 codes listed in the original HFRS paper and used the same score cutpoints as they reported (HFRS <5 being low risk, 5-15 defined as intermediate risk, and >15 as high risk for frailty; scores ≥5 were defined as frail).6

All patients were followed after discharge by research personnel blinded to the patient’s frailty assessment. We used patient/caregiver self-report and the provincial electronic health record to collect information on all-cause readmissions or mortality within 30 days.

We have previously reported4,7 the association between frailty defined by the CFS and unplanned readmissions or death within 30 days of discharge but in this study, we examined the correlation between CFS-defined frailty and the HFRS score (classifying those with intermediate or high scores as frail) using chance-corrected kappa coefficients. We also compared the prognostic accuracy of both models for predicting death and/or unplanned readmissions within 30 days using the C statistic and the integrated discrimination improvement index and examined patients aged >65 years as a subgroup.8 We used SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) for analyses, with P values of <.05 considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Of the 499 patients in our original cohort,7 we could not link 10 to the administrative data to calculate HFRS, and thus this study sample is only 489 patients (mean age 64 years, 50% women, 52% older than 65 years, a mean of 4.9 comorbidities, and median length of stay five days).

Overall, 276 (56%) patients were deemed frail according to at least one assessment (214 [44%] on the HFRS [35% intermediate risk and 9% high risk] and 161 [33%] on the CFS), and 99 (20%) met both frailty definitions (Appendix Figure). Among the 252 patients aged >65 years, 66 (26%) met both frailty definitions and 166 (66%) were frail according to at least one assessment. Agreement between HFRS and the CFS (kappa 0.24, 95% CI 0.16-0.33) was poor. The CFS definition of frailty was 46% sensitive and 77% specific in classifying frail patients compared with HFRS-defined frailty.

As we reported earlier,4 patients deemed frail were generally similar across scales in that they were older, had more comorbidities, more prescriptions, longer lengths of stay, and poorer quality of life than nonfrail patients (all P < .01, Table 1). However, patients classified as frail on the HFRS only but not meeting the CFS definition were younger, had higher quality of life, and despite a similar Charlson Score and number of comorbidities were much more likely to have been living independently prior to admission than those classified as frail on the CFS.

Death or unplanned readmission within 30 days occurred in 13.3% (65 patients), with most events being readmissions (62, 12.7%). HFRS-defined frail patients exhibited higher 30-day death/readmission rates (16% vs 11% for not frail, P = .08; 14% vs 11% in the elderly, P = .5), which was not statistically significantly different from the nonfrail patients even after adjusting for age and sex (aOR [adjusted odds ratio] 1.62, 95% CI 0.95-2.75 for all adults; aOR 1.24, 95% CI 0.58-2.63 for the elderly). CFS-defined frail patients had significantly higher 30-day readmission/death rates (19% vs 10% for not frail, aOR 2.53, 95% CI 1.40-4.57 for all adults and 21% vs 6% in the elderly, aOR 4.31, 95% CI 1.80-10.31).

Adding the HFRS results to the CFS-based predictive models added little new information, with an integrated discrimination improvement of only 0.009 that was not statistically significant (P = .09, Table 2). In fact, the HFRS was not an independent predictor of postdischarge outcomes after adjusting for age and sex. Although predictive models incorporating the CFS demonstrated the best C statistics, none of the models had high C statistics (ranging between 0.54 and 0.64 for all adults and between 0.55 and 0.68 for those aged >65 years). Even when the frailty definitions were examined as continuous variables, the C statistics were similar as for the dichotomized analyses (0.64 for CFS and 0.58 for HFRS) and the correlation between the two remained weak (Spearman’s correlation coefficient 0.34).

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that the prevalence of frailty in patients being discharged from medical wards was high, with the HFRS (44%) being higher than the CFS (33%), and that only 46% of patients deemed frail on the HFRS were also deemed frail on the CFS. We confirm the report by the developers of the HFRS that there was poor correlation between the CFS cumulative deficit model and the administrative-data-based HFRS model in our cohort, even among those older than 65 years.

Previous studies have reported marked heterogeneity in prevalence estimates between different frailty instruments.2,9 For example, Aguayo et al. found that the prevalence of frailty in the English Longitudinal Study of Aging varied between 0.9% and 68% depending on which of the 35 frailty scales they tested were used, although the prevalence with comprehensive geriatric assessments (the gold standard) was 14.9% (and 15.3% on the CFS).9 Although frail patients are at higher risk for death and/or readmission after discharge, other investigators have also reported similar findings to ours that frailty-based risk models are surprisingly modest at predicting postdischarge readmission or death, with the C statistics ranging between 0.52 and 0.57, although the CFS appears to correlate best with the gold standard of comprehensive geriatric assessment.10-14 This is not surprising since the CFS is multidimensional and as a cumulative deficit model, it incorporates assessment of the patient’s underlying diseases, cognition, function, mobility, and mood in the assignment of their CFS level. Regardless, others15 have pointed out the need for studies such as ours to compare the validity of published frailty scales.

Despite our prospective cohort design and blinded endpoint ascertainment, there are some potential limitations to our study. First, we excluded long-term care residents and patients with foreshortened life expectancy – the frailest of the frail – from our analysis of 30-day outcomes, thereby potentially reducing the magnitude of the association between frailty and adverse outcomes. However, we were interested only in situations where clinicians were faced with equipoise about patient prognosis. Second, we assessed only 30-day readmissions or deaths and cannot comment on the impact of frailty definitions on other postdischarge outcomes (such as discharge locale or need for home care services) or other timeframes. Finally, although the association between the HFRS definition of frailty and the 30-day mortality/readmission was not statistically significant, the 95% confidence intervals were wide and thus we cannot definitively rule out a positive association.

In conclusion, considering that it had the strongest association with postdischarge outcomes and is the fastest and easiest to perform, the most useful of the frailty assessment tools for clinicians at the bedside still appears to be the CFS (both overall and in those patients who are elderly). However, for researchers who are analyzing data retrospectively or policy planners looking at health services data where the CFS was not collected, the HFRS holds promise for risk adjustment in population-level studies comparing processes and outcomes between hospitals.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Miriam Fradette, Debbie Boyko, Sara Belga, Darren Lau, Jenelle Pederson, and Sharry Kahlon for their important contributions in data acquisition in our original cohort study, as well as all the physicians rotating through the general internal medicine wards at the University of Alberta Hospital for their help in identifying the patients. We also thank Dr. Simon Conroy, MB ChB PhD, University of Leicester, UK, for his helpful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. All authors had access to the data and played a role in writing and revising this manuscript.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by an operating grant from Alberta Innovates - Health Solutions. F.A.M. holds the Chair in Cardiovascular Outcomes Research at the Mazankowski Heart Institute, University of Alberta. The authors have no affiliations or financial interests with any organization or entity with a financial interest in the contents of this manuscript.

Frailty is associated with adverse outcomes in hospitalized patients, including longer length of stay, increased risk of institutionalization at discharge, and higher rates of readmissions or death postdischarge.1-4 Multiple tools have been developed to evaluate frailty and in an earlier study,4 we compared the three most common of these and demonstrated that the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS)5 was the most useful tool clinically as it was most strongly associated with adverse events in the first 30 days after discharge. However, it must be collected prospectively and requires contact with patients or proxies for the evaluator to assign the patient into one of nine categories depending on their disease state, mobility, cognition, and ability to perform instrumental and functional activities of daily living. Recently, a new score has been described which is based on an administrative data algorithm that assigns points to patients having any of 109 ICD-10 codes listed for their index hospitalization and all hospitalizations in the prior two years and can be generated retrospectively without trained observers.6 Although higher Hospital Frailty Risk Scores (HFRS) were associated with greater risk of postdischarge adverse events, the kappa when compared with the CFS was only 0.30 (95% CI 0.22-0.38) in that study.6 However, as the HFRS was developed and validated in patients aged ≥75 years within the UK National Health Service, the authors themselves recommended that it be evaluated in other healthcare systems, other populations, and with comparison to prospectively collected frailty data from cumulative deficit models such as the CFS.

The aim of this study was to compare frailty assessments using the CFS and the HFRS in a population of adult patients hospitalized on general medical wards in North America to determine the impact on prevalence estimates and prediction of outcomes within the first 30 days after hospital discharge (a timeframe highlighted in the Affordable Care Act and used by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services as an important hospital quality indicator).

METHODS

As described previously,7 we performed a prospective cohort study of adults without cognitive impairment or life expectancy less than three months being discharged back to the community (not to long-term care facilities) from general medical wards in two teaching hospitals in Edmonton, Alberta, between October 2013 and November 2014. All patients provided signed consent, and the University of Alberta Health Research Ethics board (project ID Pro00036880) approved the study.

Trained observers assessed each patient’s frailty status within 24 hours of discharge based on the patient’s best status in the week prior to becoming ill with the reason for the index hospitalization. The research assistant classified patients into one of the following nine CFS categories: very fit, well, managing well, vulnerable, mildly frail (need help with at least one instrumental activities of daily living such as shopping, finances, meal preparation, or housework), moderately frail (need help with one or two activities of daily living such as bathing and dressing), severely frail (dependent for personal care), very severely frail (bedbound), and terminally ill. According to the CFS validation studies, the last five categories were defined as frail for the purposes of our analyses.

Independent of the trained observer’s assessments, we calculated the HFRS for each participant in our cohort by linking to Alberta administrative data holdings within the Alberta Health Services Data Integration and Measurement Reporting unit and examining all diagnostic codes for the index hospitalization and any other hospitalizations in the prior two years for the 109 ICD-10 codes listed in the original HFRS paper and used the same score cutpoints as they reported (HFRS <5 being low risk, 5-15 defined as intermediate risk, and >15 as high risk for frailty; scores ≥5 were defined as frail).6

All patients were followed after discharge by research personnel blinded to the patient’s frailty assessment. We used patient/caregiver self-report and the provincial electronic health record to collect information on all-cause readmissions or mortality within 30 days.

We have previously reported4,7 the association between frailty defined by the CFS and unplanned readmissions or death within 30 days of discharge but in this study, we examined the correlation between CFS-defined frailty and the HFRS score (classifying those with intermediate or high scores as frail) using chance-corrected kappa coefficients. We also compared the prognostic accuracy of both models for predicting death and/or unplanned readmissions within 30 days using the C statistic and the integrated discrimination improvement index and examined patients aged >65 years as a subgroup.8 We used SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) for analyses, with P values of <.05 considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Of the 499 patients in our original cohort,7 we could not link 10 to the administrative data to calculate HFRS, and thus this study sample is only 489 patients (mean age 64 years, 50% women, 52% older than 65 years, a mean of 4.9 comorbidities, and median length of stay five days).

Overall, 276 (56%) patients were deemed frail according to at least one assessment (214 [44%] on the HFRS [35% intermediate risk and 9% high risk] and 161 [33%] on the CFS), and 99 (20%) met both frailty definitions (Appendix Figure). Among the 252 patients aged >65 years, 66 (26%) met both frailty definitions and 166 (66%) were frail according to at least one assessment. Agreement between HFRS and the CFS (kappa 0.24, 95% CI 0.16-0.33) was poor. The CFS definition of frailty was 46% sensitive and 77% specific in classifying frail patients compared with HFRS-defined frailty.

As we reported earlier,4 patients deemed frail were generally similar across scales in that they were older, had more comorbidities, more prescriptions, longer lengths of stay, and poorer quality of life than nonfrail patients (all P < .01, Table 1). However, patients classified as frail on the HFRS only but not meeting the CFS definition were younger, had higher quality of life, and despite a similar Charlson Score and number of comorbidities were much more likely to have been living independently prior to admission than those classified as frail on the CFS.

Death or unplanned readmission within 30 days occurred in 13.3% (65 patients), with most events being readmissions (62, 12.7%). HFRS-defined frail patients exhibited higher 30-day death/readmission rates (16% vs 11% for not frail, P = .08; 14% vs 11% in the elderly, P = .5), which was not statistically significantly different from the nonfrail patients even after adjusting for age and sex (aOR [adjusted odds ratio] 1.62, 95% CI 0.95-2.75 for all adults; aOR 1.24, 95% CI 0.58-2.63 for the elderly). CFS-defined frail patients had significantly higher 30-day readmission/death rates (19% vs 10% for not frail, aOR 2.53, 95% CI 1.40-4.57 for all adults and 21% vs 6% in the elderly, aOR 4.31, 95% CI 1.80-10.31).

Adding the HFRS results to the CFS-based predictive models added little new information, with an integrated discrimination improvement of only 0.009 that was not statistically significant (P = .09, Table 2). In fact, the HFRS was not an independent predictor of postdischarge outcomes after adjusting for age and sex. Although predictive models incorporating the CFS demonstrated the best C statistics, none of the models had high C statistics (ranging between 0.54 and 0.64 for all adults and between 0.55 and 0.68 for those aged >65 years). Even when the frailty definitions were examined as continuous variables, the C statistics were similar as for the dichotomized analyses (0.64 for CFS and 0.58 for HFRS) and the correlation between the two remained weak (Spearman’s correlation coefficient 0.34).

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that the prevalence of frailty in patients being discharged from medical wards was high, with the HFRS (44%) being higher than the CFS (33%), and that only 46% of patients deemed frail on the HFRS were also deemed frail on the CFS. We confirm the report by the developers of the HFRS that there was poor correlation between the CFS cumulative deficit model and the administrative-data-based HFRS model in our cohort, even among those older than 65 years.

Previous studies have reported marked heterogeneity in prevalence estimates between different frailty instruments.2,9 For example, Aguayo et al. found that the prevalence of frailty in the English Longitudinal Study of Aging varied between 0.9% and 68% depending on which of the 35 frailty scales they tested were used, although the prevalence with comprehensive geriatric assessments (the gold standard) was 14.9% (and 15.3% on the CFS).9 Although frail patients are at higher risk for death and/or readmission after discharge, other investigators have also reported similar findings to ours that frailty-based risk models are surprisingly modest at predicting postdischarge readmission or death, with the C statistics ranging between 0.52 and 0.57, although the CFS appears to correlate best with the gold standard of comprehensive geriatric assessment.10-14 This is not surprising since the CFS is multidimensional and as a cumulative deficit model, it incorporates assessment of the patient’s underlying diseases, cognition, function, mobility, and mood in the assignment of their CFS level. Regardless, others15 have pointed out the need for studies such as ours to compare the validity of published frailty scales.

Despite our prospective cohort design and blinded endpoint ascertainment, there are some potential limitations to our study. First, we excluded long-term care residents and patients with foreshortened life expectancy – the frailest of the frail – from our analysis of 30-day outcomes, thereby potentially reducing the magnitude of the association between frailty and adverse outcomes. However, we were interested only in situations where clinicians were faced with equipoise about patient prognosis. Second, we assessed only 30-day readmissions or deaths and cannot comment on the impact of frailty definitions on other postdischarge outcomes (such as discharge locale or need for home care services) or other timeframes. Finally, although the association between the HFRS definition of frailty and the 30-day mortality/readmission was not statistically significant, the 95% confidence intervals were wide and thus we cannot definitively rule out a positive association.

In conclusion, considering that it had the strongest association with postdischarge outcomes and is the fastest and easiest to perform, the most useful of the frailty assessment tools for clinicians at the bedside still appears to be the CFS (both overall and in those patients who are elderly). However, for researchers who are analyzing data retrospectively or policy planners looking at health services data where the CFS was not collected, the HFRS holds promise for risk adjustment in population-level studies comparing processes and outcomes between hospitals.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Miriam Fradette, Debbie Boyko, Sara Belga, Darren Lau, Jenelle Pederson, and Sharry Kahlon for their important contributions in data acquisition in our original cohort study, as well as all the physicians rotating through the general internal medicine wards at the University of Alberta Hospital for their help in identifying the patients. We also thank Dr. Simon Conroy, MB ChB PhD, University of Leicester, UK, for his helpful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. All authors had access to the data and played a role in writing and revising this manuscript.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by an operating grant from Alberta Innovates - Health Solutions. F.A.M. holds the Chair in Cardiovascular Outcomes Research at the Mazankowski Heart Institute, University of Alberta. The authors have no affiliations or financial interests with any organization or entity with a financial interest in the contents of this manuscript.

1. Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):752-762. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9. PubMed

2. Collard RM, Boter H, Schoevers RA, Oude Voshaar RC. Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(8):1487-1492. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04054.x. PubMed

3. de Vries NM, Staal JB, van Ravensberg CD, Hobbelen JS, Olde Rikkert MG, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW. Outcome instruments to measure frailty: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(1):104-114. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.09.001. PubMed

4. Belga S, Majumdar SR, Kahlon S, et al. Comparing three different measures of frailty in medical inpatients: multicenter prospective cohort study examining 30-day risk of readmission or death. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(8):556-562. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2607. PubMed

5. Rockwood K, Andrew M, Mintnitski A. A comparison of two approaches to measuring frailty in elerly people. J Gerontol. 2007;62(7):738-743. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.7.738. PubMed

6. Gilbert T, Neuburger J, Kraindler J, et al. Development and validation of a Hospital Frailty Risk Score focusing on older people in acute care settings using electronic hospital records: an observational study. Lancet. 2018;391(10132):1775-1782. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30668-8Get. PubMed