User login

Families as Care Partners: Implementing the Better Together Initiative Across a Large Health System

From the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care, Bethesda, MD (Ms. Dokken and Ms. Johnson), and Northwell Health, New Hyde Park, NY (Dr. Barden, Ms. Tuomey, and Ms. Giammarinaro).

Abstract

Objective: To describe the growth of Better Together: Partnering with Families, a campaign launched in 2014 to eliminate restrictive hospital visiting policies and to put in place policies that recognize families as partners in care, and to discuss the processes involved in implementing the initiative in a large, integrated health system.

Methods: Descriptive report.

Results: In June 2014, the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care (IPFCC) launched the Better Together campaign to emphasize the importance of family presence and participation to the quality, experience, safety, and outcomes of care. Since then, this initiative has expanded in both the United States and Canada. With support from 2 funders in the United States, special attention was focused on acute care hospitals across New York State. Nearly 50 hospitals participated in 2 separate but related projects. Fifteen of the hospitals are part of Northwell Health, New York State’s largest health system. Over a 10-month period, these hospitals made significant progress in changing policy, practice, and communication to support family presence.

Conclusion: The Better Together initiative was implemented across a health system with strong support from leadership and the involvement of patient and family advisors. An intervention offering structured training, coaching, and resources, like IPFCC’s Better Together initiative, can facilitate the change process.

Keywords: family presence; visiting policies; patient-centered care; family-centered care; patient experience.

The presence of families at the bedside of patients is often restricted by hospital visiting hours. Hospitals that maintain these restrictive policies cite concerns about negative impacts on security, infection control, privacy, and staff workload. But there are no data to support these concerns, and the experience of hospitals that have successfully changed policy and practice to welcome families demonstrates the potential positive impacts of less restrictive policies on patient care and outcomes.1 For example, hospitalization can lead to reduced cognitive function in elderly patients. Family members would recognize the changes and could provide valuable information to hospital staff, potentially improving outcomes.2

In June 2014, the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care (IPFCC) launched the campaign Better Together: Partnering with Families.3 The campaign is is grounded in patient- and family- centered care, an approach to care that supports partnerships among health care providers, patients, and families, and, among other core principles, advocates that patients define their “families” and how they will participate in care and decision-making.

Emphasizing the importance of family presence and participation to quality and safety, the Better Together campaign seeks to eliminate restrictive visiting policies and calls upon hospitals to include families as members of the care team and to welcome them 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, according to patient preference. As part of the campaign, IPFCC developed an extensive toolkit of resources that is available to hospitals and other organizations at no cost. The resources include sample policies; profiles of hospitals that have implemented family presence policies; educational materials for staff, patients, and families; and a template for hospital websites. This article, a follow-up to an article published in the January 2015 issue of JCOM,1 discusses the growth of the Better Together initiative as well as the processes involved in implementing the initiative across a large health system.

Growth of the Initiative

Since its launch in 2014, the Better Together initiative has continued to expand in the United States and Canada. In Canada, under the leadership of the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement (CFHI), more than 50 organizations have made a commitment to the Better Together program and family presence.4 Utilizing and adapting IPFCC’s Toolkit, CFHI developed a change package of free resources for Canadian organizations.5 Some of the materials, including the Pocket Guide for Families (Manuel des Familles), were translated into French.6

With support from 2 funders in the United States, the United Hospital Fund and the New York State Health (NYSHealth) Foundation, through a subcontract with the New York Public Interest Research Group (NYPIRG), IPFCC has been able to focus on hospitals in New York City, including public hospitals, and, more broadly, acute care hospitals across New York State. Nearly 50 hospitals participated in these 2 separate but related projects.

Education and Support for New York City Hospitals

Supported by the United Hospital Fund, an 18-month project that focused specifically on New York City hospitals was completed in June 2017. The project began with a 1-day intensive training event with representatives of 21 hospitals. Eighteen of those hospitals were eligible to participate in follow-up consultation provided by IPFCC, and 14 participated in some kind of follow-up. NYC Health + Hospitals (H+H), the system of public hospitals in NYC, participated most fully in these activities.

The outcomes of the Better Together initiative in New York City are summarized in the report Sick, Scared, & Separated From Loved Ones,2 which is based on a pre/post review of hospital visitation/family presence policies and website communications. According to the report, hospitals that participated in the IPFCC training and consultation program performed better, as a group, with respect to improved policy and website scores on post review than those that did not. Of the 10 hospitals whose scores improved during the review period, 8 had participated in the IPFCC training and 1 hospital was part of a hospital network that did so. (Six of these hospitals are part of the H+H public hospital system.) Those 9 hospitals saw an average increase in scores of 4.9 points (out of a possible 11).

A Learning Community for Hospitals in New York State

With support from the NYSHealth Foundation, IPFCC again collaborated with NYPIRG and New Yorkers for Patient & Family Empowerment on a 2-year initiative, completed in November 2019, that involved 26 hospitals: 15 from Northwell Health, New York State’s largest health system, and 11 hospitals from health systems throughout the state (Greater Hudson Valley Health System, now Garnet Health; Mohawk Valley Health System; Rochester Regional Health; and University of Vermont Health Network). An update of the report Sick, Scared, & Separated From Loved Onescompared pre/post reviews of policies and website communications regarding hospital visitation/family presence.7 Its findings confirm that hospitals that participated in the Better Together Learning Community improved both their policy and website scores to a greater degree than hospitals that did not participate and that a planned intervention can help facilitate change.

During the survey period, 28 out of 40 hospitals’ website navigability scores improved. Of those, hospitals that did not participate in the Better Together Learning Community saw an average increase in scores of 1.2 points, out of a possible 11, while the participating hospitals saw an average increase of 2.7 points, with the top 5 largest increases in scores belonging to hospitals that participated in the Better Together Learning Community.7

The Northwell Health Experience

Northwell Health is a large integrated health care organization comprising more than 69,000 employees, 23 hospitals, and more than 750 medical practices, located geographically across New York State. Embracing patient- and family-centered care, Northwell is dedicated to improving the quality, experience, and safety of care for patients and their families. Welcoming and including patients, families, and care partners as members of the health care team has always been a core element of Northwell’s organizational goal of providing world-class patient care and experience.

Four years ago, the organization reorganized and formalized a system-wide Patient & Family Partnership Council (PFPC).8 Representatives on the PFPC include a Northwell patient experience leader and patient/family co-chair from local councils that have been established in nearly all 23 hospitals as well as service lines. Modeling partnership, the PFPC is grounded in listening to the “voice” of patients and families and promoting collaboration, with the goal of driving change across varied aspects and experiences of health care delivery.

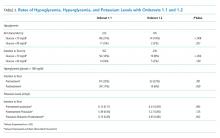

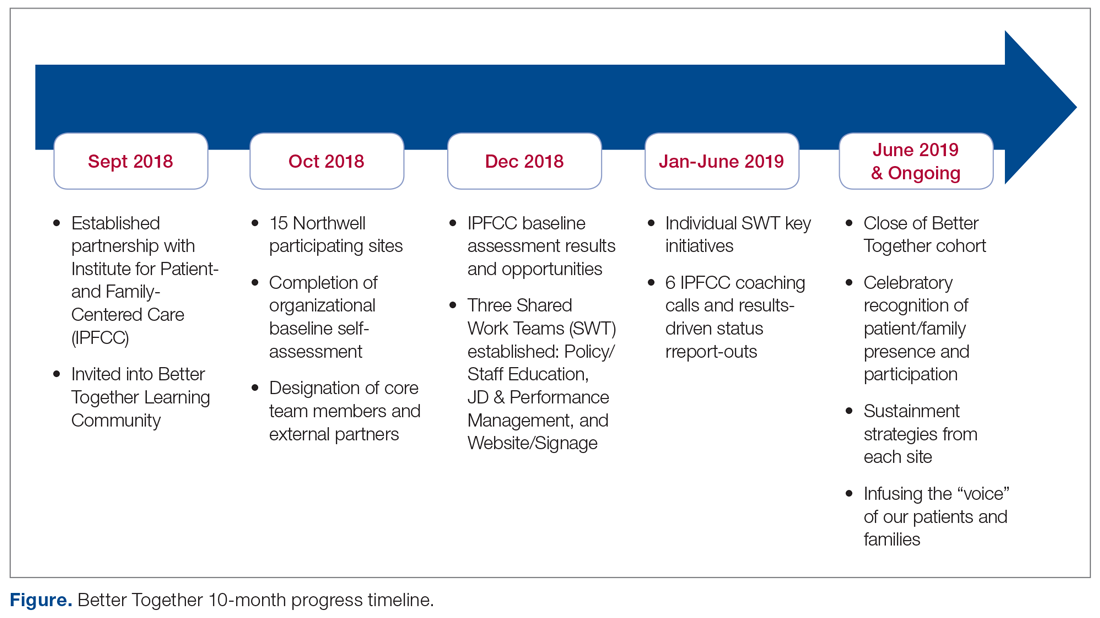

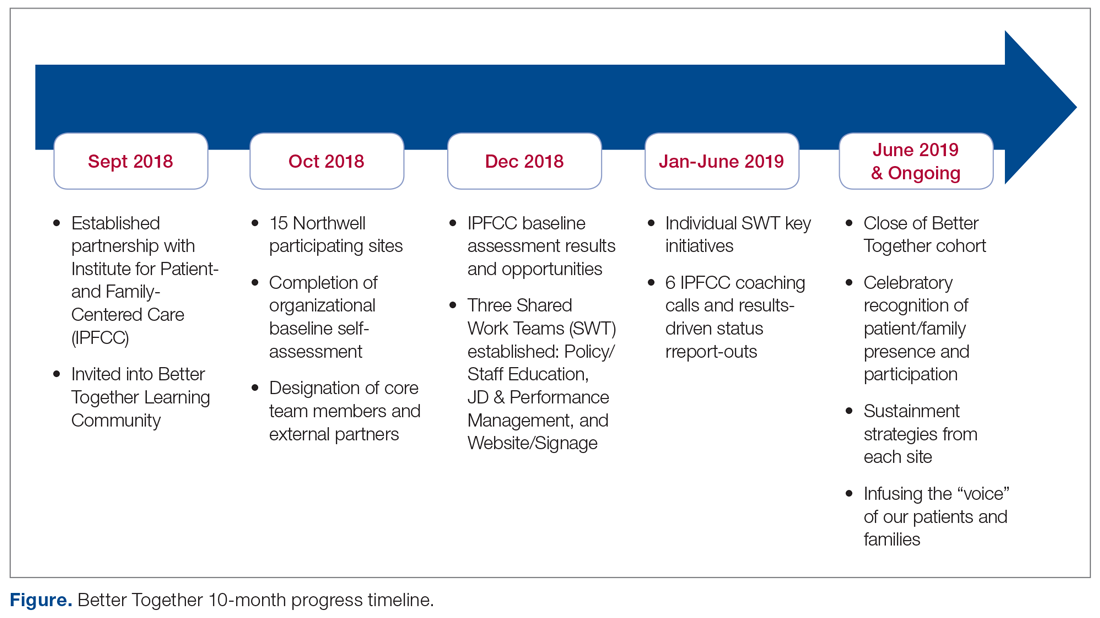

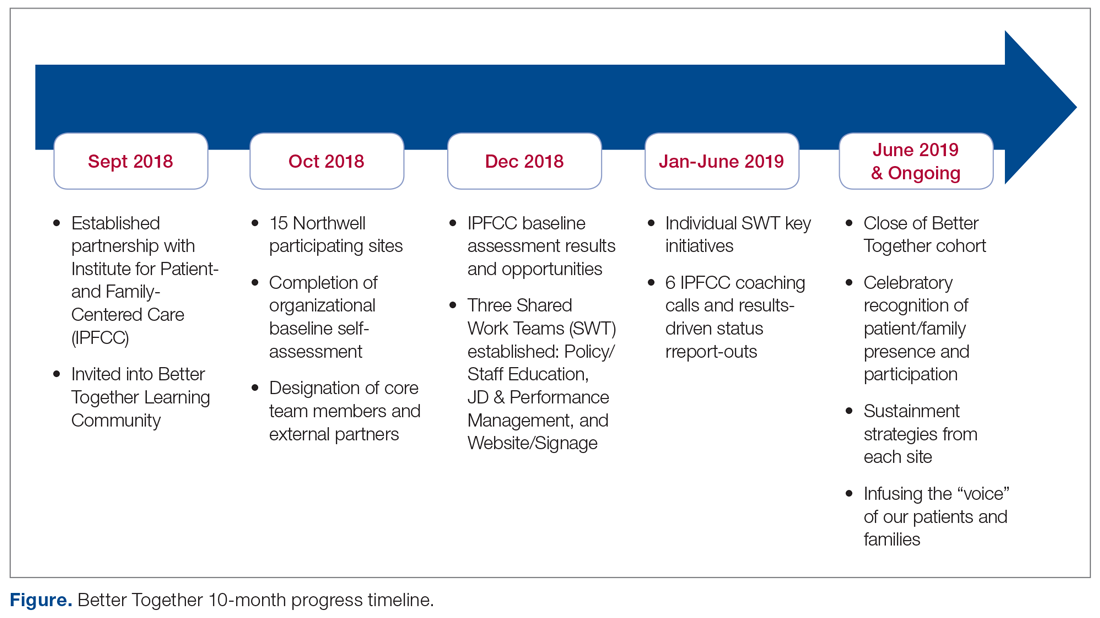

Through the Office of Patient and Customer Experience (OPCE), a partnership with IPFCC and the Better Together Learning Community for Hospitals in New York State was initiated as a fundamental next step in Northwell’s journey to enhance system-wide family presence and participation. Results from Better Together’s Organizational Self-Assessment Tool and process identified opportunities to influence 3 distinct areas: policy/staff education, position descriptions/performance management, and website/signage. Over a 10-month period (September 2018 through June 2019), 15 Northwell hospitals implemened significant patient- and family-centered improvements through multifaceted shared work teams (SWT) that partnered around the common goal of supporting the patient and family experience (Figure). Northwell’s SWT structure allowed teams to meet individually on specific tasks, led by a dedicated staff member of the OPCE to ensure progress, support, and accountability. Six monthly coaching calls or report-out meetings were attended by participating teams, where feedback and recommendations shared by IPFCC were discussed in order to maintain momentum and results.

Policy/Staff Education

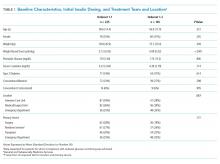

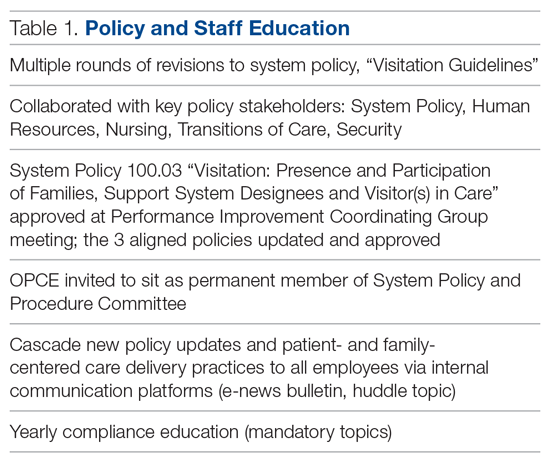

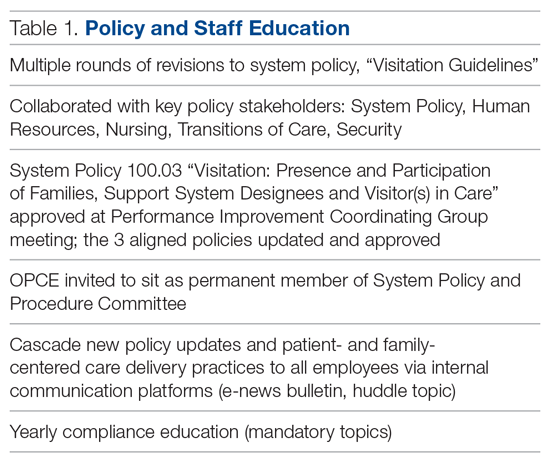

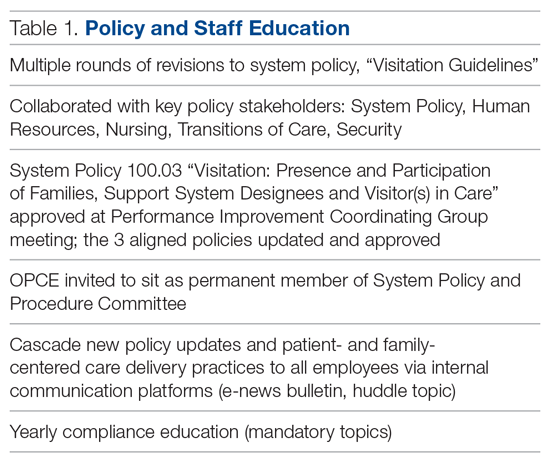

The policy/staff education SWT focused on appraising and updating existing policies to ensure alignment with key patient- and family-centered concepts and Better Together principles (Table 1). By establishing representation on the System Policy and Procedure Committee, OPCE enabled patients and families to have a voice at the decision-making table. OPCE leaders presented the ideology and scope of the transformation to this committee. After reviewing all system-wide policies, 4 were identified as key opportunities for revision. One overarching policy titled “Visitation Guidelines” was reviewed and updated to reflect Northwell’s mission of patient- and family-centered care, retiring the reference to “families” as “visitors” in definitions, incorporating language of inclusion and partnership, and citing other related policies. The policy was vetted through a multilayer process of review and stakeholder feedback and was ultimately approved at a system

Three additional related policies were also updated to reflect core principles of inclusion and partnership. These included system policies focused on discharge planning; identification of health care proxy, agent, support person and caregiver; and standards of behavior not conducive in a health care setting. As a result of this work, OPCE was invited to remain an active member of the System Policy and Procedure Committee, adding meaningful new perspectives to the clinical and administrative policy management process. Once policies were updated and approved, the SWT focused on educating leaders and teams. Using a diversified strategy, education was provided through various modes, including weekly system-wide internal communication channels, patient experience huddle messages, yearly mandatory topics training, and the incorporation of essential concepts in existing educational courses (classroom and e-learning modalities).

Position Descriptions/Performance Management

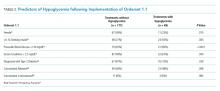

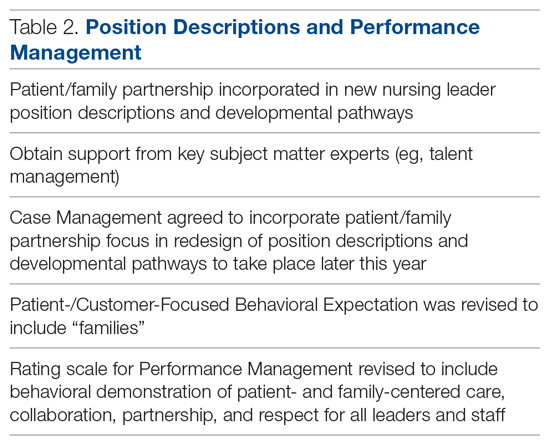

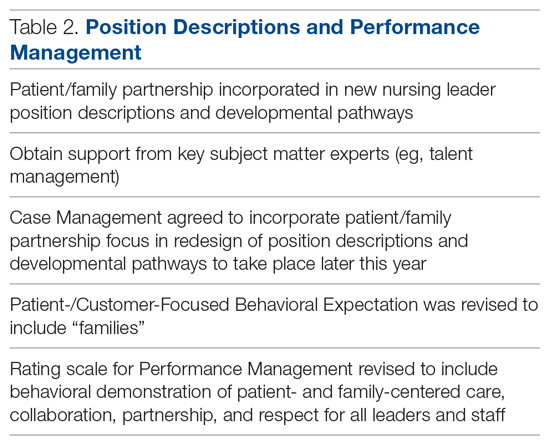

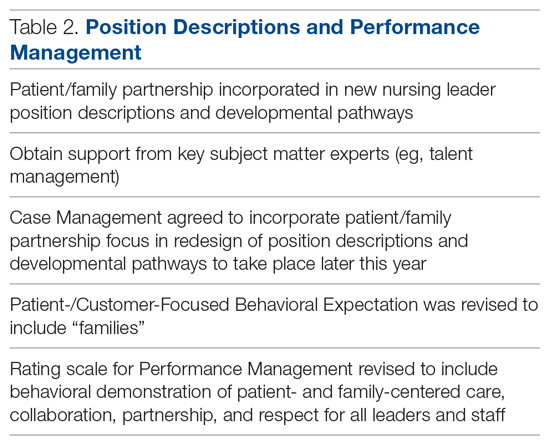

The position descriptions/performance management SWT focused its efforts on incorporating patient- and family-centered concepts and language into position descriptions and the performance appraisal process (Table 2). Due to the complex nature of this work, the process required collaboration from key subject matter experts in human resources, talent management, corporate compensation, and labor management. In 2019, Northwell began an initiative focused on streamlining and standardizing job titles, roles, and developmental pathways across the system. The overarching goal was to create system-wide consistency and standardization. The SWT was successful in advising the leaders overseeing this job architecture initiative on the importance of including language of patient- and family-centered care, like partnership and collaboration, and of highlighting the critical role of family members as part of the care team in subsequent documents.

Northwell has 6 behavioral expectations, standards to which all team members are held accountable: Patient/Customer Focus, Teamwork, Execution, Organizational Awareness, Enable Change, and Develop Self. As a result of the SWT’s work, Patient/Customer Focus was revised to include “families” as essential care partners, demonstrating Northwell’s ongoing commitment to honoring the role of families as members of the care team. It also ensures that all employees are aligned around this priority, as these expectations are utilized to support areas such as recognition and performance. Collaborating with talent management and organizational development, the SWT reviewed yearly performance management and new-hire evaluations. In doing so, they identified an opportunity to refresh the anchored qualitative rating scales to include behavioral demonstrations of patient- and family-centered care, collaboration, respect, and partnership with family members.

Website/Signage

Websites make an important first impression on patients and families looking for information to best prepare for a hospital experience. Therefore, the website/signage SWT worked to redesign hospital websites, enhance digital signage, and perform a baseline assessment of physical signage across facilities. Initial feedback on Northwell’s websites identified opportunities to include more patient- and family-centered, care-partner-infused language; improve navigation; and streamline click levels for easier access. Content for the websites was carefully crafted in collaboration with Northwell’s internal web team, utilizing IPFCC’s best practice standards as a framework and guide.

Next, a multidisciplinary website shared-governance team was established by the OPCE to ensure that key stakeholders were represented and had the opportunity to review and make recommendations for appropriate language and messaging about family presence and participation. This 13-person team was comprised of patient/family partners, patient-experience culture leaders, quality, compliance, human resources, policy, a chief nursing officer, a medical director, and representation from the Institute for Nursing. After careful review and consideration from Northwell’s family partners and teams, all participating hospital websites were enhanced as of June 2019 to include prominent 1-click access from homepages to information for “patients, families and visitors,” as well as “your care partners” information on the important role of families and care partners.

Along with refreshing websites, another step in Northwell’s work to strengthen messaging about family presence and participation was to partner and collaborate with the system’s digital web team as well as local facility councils to understand the capacity to adjust digital signage across facilities. Opportunities were found to make simple yet effective enhancements to the language and imagery of digital signage upon entry, creating a warmer and more welcoming first impression for patients and families. With patient and family partner feedback, the team designed digital signage with inclusive messaging and images that would circulate appropriately based on the facility. Signage specifically welcomes families and refers to them as members of patients’ care teams.

Northwell’s website/signage SWT also directed a 2-phase physical signage assessment to determine ongoing opportunities to alter signs in areas that particularly impact patients and families, such as emergency departments, main lobbies, cafeterias, surgical waiting areas, and intensive care units. Each hospital’s local PFPC did a “walk-about”9 to make enhancements to physical signage, such as removing paper and overcrowded signs, adjusting negative language, ensuring alignment with brand guidelines, and including language that welcomed families. As a result of the team’s efforts around signage, collaboration began with the health system’s signage committee to help standardize signage terminology to reflect family inclusiveness, and to implement the recommendation for a standardized signage shared-governance team to ensure accountability and a patient- and family-centered structure.

Sustainment

Since implementing Better Together, Northwell has been able to infuse a more patient- and family-centered emphasis into its overall patient experience message of “Every role, every person, every moment matters.” As a strategic tool aimed at encouraging leaders, clinicians, and staff to pause and reflect about the “heart” of their work, patient and family stories are now included at the beginning of meetings, forums, and team huddles. Elements of the initiative have been integrated in current Patient and Family Partnership sustainment plans at participating hospitals. Some highlights include continued integration of patient/family partners on committees and councils that impact areas such as way finding, signage, recruitment, new-hire orientation, and community outreach; focus on enhancing partner retention and development programs; and inclusion of patient- and family-centered care and Better Together principles in ongoing leadership meetings.

Factors Contributing to Success

Health care is a complex, regulated, and often bureaucratic world that can be very difficult for patients and families to navigate. The system’s partnership with the Better Together Learning Community for Hospitals in New York State enhanced its efforts to improve family presence and participation and created powerful synergy. The success of this partnership was based on a number of important factors:

A solid foundation of support, structure, and accountability. The OPCE initiated the IPFCC Better Together partnership and established a synergistic collaboration inclusive of leadership, frontline teams, multiple departments, and patient and family partners. As a major strategic component of Northwell’s mission to deliver high-quality, patient- and family-centered care, OPCE was instrumental in connecting key areas and stakeholders and mobilizing the recommendations coming from patients and families.

A visible commitment of leadership at all levels. Partnering with leadership across Northwell’s system required a delineated vision, clear purpose and ownership, and comprehensive implementation and sustainment strategies. The existing format of Northwell’s PFPC provided the structure and framework needed for engaged patient and family input; the OPCE motivated and organized key areas of involvement and led communication efforts across the organization. The IPFCC coaching calls provided the underlying guidance and accountability needed to sustain momentum. As leadership and frontline teams became aware of the vision, they understood the larger connection to the system’s purpose, which ultimately created a clear path for positive change.

Meaningful involvement and input of patient and family partners. Throughout this project, Northwell’s patient/family partners were involved through the PFPC and local councils. For example, patient/family partners attended every IPFCC coaching call; members had a central voice in every decision made within each SWT; and local PFPCs actively participated in physical signage “walk-abouts” across facilities, making key recommendations for improvement. This multifaceted, supportive collaboration created a rejuvenated and purposeful focus for all council members involved. Some of their reactions include, “…I am so happy to be able to help other families in crisis, so that they don’t have to be alone, like I was,” and “I feel how important the patient and family’s voice is … it’s truly a partnership between patients, families, and staff.”

Regular access to IPFCC as a best practice coach and expert resource. Throughout the 10-month process, IPFCC’s Better Together Learning Community for Hospitals in New York State provided ongoing learning interventions for members of the SWT; multiple and varied resources from the Better Together toolkit for adaptation; and opportunities to share and reinforce new, learned expertise with colleagues within the Northwell Health system and beyond through IPFCC’s free online learning community, PFCC.Connect.

Conclusion

Family presence and participation are important to the quality, experience, safety, and outcomes of care. IPFCC’s campaign, Better Together: Partnering with Families, encourages hospitals to change restrictive visiting policies and, instead, to welcome families and caregivers 24 hours a day.

Two projects within Better Together involving almost 50 acute care hospitals in New York State confirm that change in policy, practice, and communication is particularly effective when implemented with strong support from leadership. An intervention like the Better Together Learning Community, offering structured training, coaching, and resources, can facilitate the change process.

Corresponding author: IPFCC, Deborah L. Dokken, 6917 Arlington Rd., Ste. 309, Bethesda, MD 20814; [email protected].

Funding disclosures: None.

1. Dokken DL, Kaufman J, Johnson BJ et al. Changing hospital visiting policies: from families as “visitors” to families as partners. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2015; 22:29-36.

2. New York Public Interest Research Group and New Yorkers for Patient & Family Empowerment. Sick, scared and separated from loved ones. third edition: A pathway to improvement in New York City. New York: NYPIRG: 2018. www.nypirg.org/pubs/201801/NYPIRG_SICK_SCARED_FINAL.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2019.

3. Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Better Together: Partnering with Families. www.ipfcc.org/bestpractices/better-together.html. Accessed December 12, 2019.

4. Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement. Better Together. www.cfhi-fcass.ca/WhatWeDo/better-together. Accessed December 12, 2019.

5. Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement. Better Together: A change package to support the adoption of family presence and participation in acute care hospitals and accelerate healthcare improvement. www.cfhi-fcass.ca/sf-docs/default-source/patient-engagement/better-together-change-package.pdf?sfvrsn=9656d044_4. Accessed December 12, 2019.

6. Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement. L’Objectif santé: main dans la main avec les familles. www.cfhi-fcass.ca/sf-docs/default-source/patient-engagement/families-pocket-screen_fr.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2019.

7. New York Public Interest Research Group and New Yorkers for Patient & Family Empowerment. Sick, scared and separated from loved ones. fourth edition: A pathway to improvement in New York. New York: NYPIRG: 2019. www.nypirg.org/pubs/201911/Sick_Scared_Separated_2019_web_FINAL.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2019.

8. Northwell Health. Patient and Family Partnership Councils. www.northwell.edu/about/commitment-to-excellence/patient-and-customer-experience/care-delivery-hospitality. Accessed December 12, 2019.

9 . Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. How to conduct a “walk-about” from the patient and family perspective. www.ipfcc.org/resources/How_To_Conduct_A_Walk-About.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2019.

From the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care, Bethesda, MD (Ms. Dokken and Ms. Johnson), and Northwell Health, New Hyde Park, NY (Dr. Barden, Ms. Tuomey, and Ms. Giammarinaro).

Abstract

Objective: To describe the growth of Better Together: Partnering with Families, a campaign launched in 2014 to eliminate restrictive hospital visiting policies and to put in place policies that recognize families as partners in care, and to discuss the processes involved in implementing the initiative in a large, integrated health system.

Methods: Descriptive report.

Results: In June 2014, the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care (IPFCC) launched the Better Together campaign to emphasize the importance of family presence and participation to the quality, experience, safety, and outcomes of care. Since then, this initiative has expanded in both the United States and Canada. With support from 2 funders in the United States, special attention was focused on acute care hospitals across New York State. Nearly 50 hospitals participated in 2 separate but related projects. Fifteen of the hospitals are part of Northwell Health, New York State’s largest health system. Over a 10-month period, these hospitals made significant progress in changing policy, practice, and communication to support family presence.

Conclusion: The Better Together initiative was implemented across a health system with strong support from leadership and the involvement of patient and family advisors. An intervention offering structured training, coaching, and resources, like IPFCC’s Better Together initiative, can facilitate the change process.

Keywords: family presence; visiting policies; patient-centered care; family-centered care; patient experience.

The presence of families at the bedside of patients is often restricted by hospital visiting hours. Hospitals that maintain these restrictive policies cite concerns about negative impacts on security, infection control, privacy, and staff workload. But there are no data to support these concerns, and the experience of hospitals that have successfully changed policy and practice to welcome families demonstrates the potential positive impacts of less restrictive policies on patient care and outcomes.1 For example, hospitalization can lead to reduced cognitive function in elderly patients. Family members would recognize the changes and could provide valuable information to hospital staff, potentially improving outcomes.2

In June 2014, the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care (IPFCC) launched the campaign Better Together: Partnering with Families.3 The campaign is is grounded in patient- and family- centered care, an approach to care that supports partnerships among health care providers, patients, and families, and, among other core principles, advocates that patients define their “families” and how they will participate in care and decision-making.

Emphasizing the importance of family presence and participation to quality and safety, the Better Together campaign seeks to eliminate restrictive visiting policies and calls upon hospitals to include families as members of the care team and to welcome them 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, according to patient preference. As part of the campaign, IPFCC developed an extensive toolkit of resources that is available to hospitals and other organizations at no cost. The resources include sample policies; profiles of hospitals that have implemented family presence policies; educational materials for staff, patients, and families; and a template for hospital websites. This article, a follow-up to an article published in the January 2015 issue of JCOM,1 discusses the growth of the Better Together initiative as well as the processes involved in implementing the initiative across a large health system.

Growth of the Initiative

Since its launch in 2014, the Better Together initiative has continued to expand in the United States and Canada. In Canada, under the leadership of the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement (CFHI), more than 50 organizations have made a commitment to the Better Together program and family presence.4 Utilizing and adapting IPFCC’s Toolkit, CFHI developed a change package of free resources for Canadian organizations.5 Some of the materials, including the Pocket Guide for Families (Manuel des Familles), were translated into French.6

With support from 2 funders in the United States, the United Hospital Fund and the New York State Health (NYSHealth) Foundation, through a subcontract with the New York Public Interest Research Group (NYPIRG), IPFCC has been able to focus on hospitals in New York City, including public hospitals, and, more broadly, acute care hospitals across New York State. Nearly 50 hospitals participated in these 2 separate but related projects.

Education and Support for New York City Hospitals

Supported by the United Hospital Fund, an 18-month project that focused specifically on New York City hospitals was completed in June 2017. The project began with a 1-day intensive training event with representatives of 21 hospitals. Eighteen of those hospitals were eligible to participate in follow-up consultation provided by IPFCC, and 14 participated in some kind of follow-up. NYC Health + Hospitals (H+H), the system of public hospitals in NYC, participated most fully in these activities.

The outcomes of the Better Together initiative in New York City are summarized in the report Sick, Scared, & Separated From Loved Ones,2 which is based on a pre/post review of hospital visitation/family presence policies and website communications. According to the report, hospitals that participated in the IPFCC training and consultation program performed better, as a group, with respect to improved policy and website scores on post review than those that did not. Of the 10 hospitals whose scores improved during the review period, 8 had participated in the IPFCC training and 1 hospital was part of a hospital network that did so. (Six of these hospitals are part of the H+H public hospital system.) Those 9 hospitals saw an average increase in scores of 4.9 points (out of a possible 11).

A Learning Community for Hospitals in New York State

With support from the NYSHealth Foundation, IPFCC again collaborated with NYPIRG and New Yorkers for Patient & Family Empowerment on a 2-year initiative, completed in November 2019, that involved 26 hospitals: 15 from Northwell Health, New York State’s largest health system, and 11 hospitals from health systems throughout the state (Greater Hudson Valley Health System, now Garnet Health; Mohawk Valley Health System; Rochester Regional Health; and University of Vermont Health Network). An update of the report Sick, Scared, & Separated From Loved Onescompared pre/post reviews of policies and website communications regarding hospital visitation/family presence.7 Its findings confirm that hospitals that participated in the Better Together Learning Community improved both their policy and website scores to a greater degree than hospitals that did not participate and that a planned intervention can help facilitate change.

During the survey period, 28 out of 40 hospitals’ website navigability scores improved. Of those, hospitals that did not participate in the Better Together Learning Community saw an average increase in scores of 1.2 points, out of a possible 11, while the participating hospitals saw an average increase of 2.7 points, with the top 5 largest increases in scores belonging to hospitals that participated in the Better Together Learning Community.7

The Northwell Health Experience

Northwell Health is a large integrated health care organization comprising more than 69,000 employees, 23 hospitals, and more than 750 medical practices, located geographically across New York State. Embracing patient- and family-centered care, Northwell is dedicated to improving the quality, experience, and safety of care for patients and their families. Welcoming and including patients, families, and care partners as members of the health care team has always been a core element of Northwell’s organizational goal of providing world-class patient care and experience.

Four years ago, the organization reorganized and formalized a system-wide Patient & Family Partnership Council (PFPC).8 Representatives on the PFPC include a Northwell patient experience leader and patient/family co-chair from local councils that have been established in nearly all 23 hospitals as well as service lines. Modeling partnership, the PFPC is grounded in listening to the “voice” of patients and families and promoting collaboration, with the goal of driving change across varied aspects and experiences of health care delivery.

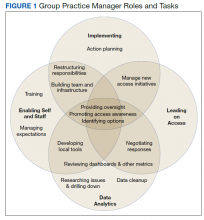

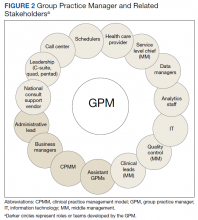

Through the Office of Patient and Customer Experience (OPCE), a partnership with IPFCC and the Better Together Learning Community for Hospitals in New York State was initiated as a fundamental next step in Northwell’s journey to enhance system-wide family presence and participation. Results from Better Together’s Organizational Self-Assessment Tool and process identified opportunities to influence 3 distinct areas: policy/staff education, position descriptions/performance management, and website/signage. Over a 10-month period (September 2018 through June 2019), 15 Northwell hospitals implemened significant patient- and family-centered improvements through multifaceted shared work teams (SWT) that partnered around the common goal of supporting the patient and family experience (Figure). Northwell’s SWT structure allowed teams to meet individually on specific tasks, led by a dedicated staff member of the OPCE to ensure progress, support, and accountability. Six monthly coaching calls or report-out meetings were attended by participating teams, where feedback and recommendations shared by IPFCC were discussed in order to maintain momentum and results.

Policy/Staff Education

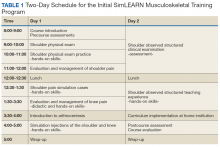

The policy/staff education SWT focused on appraising and updating existing policies to ensure alignment with key patient- and family-centered concepts and Better Together principles (Table 1). By establishing representation on the System Policy and Procedure Committee, OPCE enabled patients and families to have a voice at the decision-making table. OPCE leaders presented the ideology and scope of the transformation to this committee. After reviewing all system-wide policies, 4 were identified as key opportunities for revision. One overarching policy titled “Visitation Guidelines” was reviewed and updated to reflect Northwell’s mission of patient- and family-centered care, retiring the reference to “families” as “visitors” in definitions, incorporating language of inclusion and partnership, and citing other related policies. The policy was vetted through a multilayer process of review and stakeholder feedback and was ultimately approved at a system

Three additional related policies were also updated to reflect core principles of inclusion and partnership. These included system policies focused on discharge planning; identification of health care proxy, agent, support person and caregiver; and standards of behavior not conducive in a health care setting. As a result of this work, OPCE was invited to remain an active member of the System Policy and Procedure Committee, adding meaningful new perspectives to the clinical and administrative policy management process. Once policies were updated and approved, the SWT focused on educating leaders and teams. Using a diversified strategy, education was provided through various modes, including weekly system-wide internal communication channels, patient experience huddle messages, yearly mandatory topics training, and the incorporation of essential concepts in existing educational courses (classroom and e-learning modalities).

Position Descriptions/Performance Management

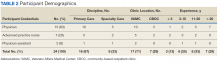

The position descriptions/performance management SWT focused its efforts on incorporating patient- and family-centered concepts and language into position descriptions and the performance appraisal process (Table 2). Due to the complex nature of this work, the process required collaboration from key subject matter experts in human resources, talent management, corporate compensation, and labor management. In 2019, Northwell began an initiative focused on streamlining and standardizing job titles, roles, and developmental pathways across the system. The overarching goal was to create system-wide consistency and standardization. The SWT was successful in advising the leaders overseeing this job architecture initiative on the importance of including language of patient- and family-centered care, like partnership and collaboration, and of highlighting the critical role of family members as part of the care team in subsequent documents.

Northwell has 6 behavioral expectations, standards to which all team members are held accountable: Patient/Customer Focus, Teamwork, Execution, Organizational Awareness, Enable Change, and Develop Self. As a result of the SWT’s work, Patient/Customer Focus was revised to include “families” as essential care partners, demonstrating Northwell’s ongoing commitment to honoring the role of families as members of the care team. It also ensures that all employees are aligned around this priority, as these expectations are utilized to support areas such as recognition and performance. Collaborating with talent management and organizational development, the SWT reviewed yearly performance management and new-hire evaluations. In doing so, they identified an opportunity to refresh the anchored qualitative rating scales to include behavioral demonstrations of patient- and family-centered care, collaboration, respect, and partnership with family members.

Website/Signage

Websites make an important first impression on patients and families looking for information to best prepare for a hospital experience. Therefore, the website/signage SWT worked to redesign hospital websites, enhance digital signage, and perform a baseline assessment of physical signage across facilities. Initial feedback on Northwell’s websites identified opportunities to include more patient- and family-centered, care-partner-infused language; improve navigation; and streamline click levels for easier access. Content for the websites was carefully crafted in collaboration with Northwell’s internal web team, utilizing IPFCC’s best practice standards as a framework and guide.

Next, a multidisciplinary website shared-governance team was established by the OPCE to ensure that key stakeholders were represented and had the opportunity to review and make recommendations for appropriate language and messaging about family presence and participation. This 13-person team was comprised of patient/family partners, patient-experience culture leaders, quality, compliance, human resources, policy, a chief nursing officer, a medical director, and representation from the Institute for Nursing. After careful review and consideration from Northwell’s family partners and teams, all participating hospital websites were enhanced as of June 2019 to include prominent 1-click access from homepages to information for “patients, families and visitors,” as well as “your care partners” information on the important role of families and care partners.

Along with refreshing websites, another step in Northwell’s work to strengthen messaging about family presence and participation was to partner and collaborate with the system’s digital web team as well as local facility councils to understand the capacity to adjust digital signage across facilities. Opportunities were found to make simple yet effective enhancements to the language and imagery of digital signage upon entry, creating a warmer and more welcoming first impression for patients and families. With patient and family partner feedback, the team designed digital signage with inclusive messaging and images that would circulate appropriately based on the facility. Signage specifically welcomes families and refers to them as members of patients’ care teams.

Northwell’s website/signage SWT also directed a 2-phase physical signage assessment to determine ongoing opportunities to alter signs in areas that particularly impact patients and families, such as emergency departments, main lobbies, cafeterias, surgical waiting areas, and intensive care units. Each hospital’s local PFPC did a “walk-about”9 to make enhancements to physical signage, such as removing paper and overcrowded signs, adjusting negative language, ensuring alignment with brand guidelines, and including language that welcomed families. As a result of the team’s efforts around signage, collaboration began with the health system’s signage committee to help standardize signage terminology to reflect family inclusiveness, and to implement the recommendation for a standardized signage shared-governance team to ensure accountability and a patient- and family-centered structure.

Sustainment

Since implementing Better Together, Northwell has been able to infuse a more patient- and family-centered emphasis into its overall patient experience message of “Every role, every person, every moment matters.” As a strategic tool aimed at encouraging leaders, clinicians, and staff to pause and reflect about the “heart” of their work, patient and family stories are now included at the beginning of meetings, forums, and team huddles. Elements of the initiative have been integrated in current Patient and Family Partnership sustainment plans at participating hospitals. Some highlights include continued integration of patient/family partners on committees and councils that impact areas such as way finding, signage, recruitment, new-hire orientation, and community outreach; focus on enhancing partner retention and development programs; and inclusion of patient- and family-centered care and Better Together principles in ongoing leadership meetings.

Factors Contributing to Success

Health care is a complex, regulated, and often bureaucratic world that can be very difficult for patients and families to navigate. The system’s partnership with the Better Together Learning Community for Hospitals in New York State enhanced its efforts to improve family presence and participation and created powerful synergy. The success of this partnership was based on a number of important factors:

A solid foundation of support, structure, and accountability. The OPCE initiated the IPFCC Better Together partnership and established a synergistic collaboration inclusive of leadership, frontline teams, multiple departments, and patient and family partners. As a major strategic component of Northwell’s mission to deliver high-quality, patient- and family-centered care, OPCE was instrumental in connecting key areas and stakeholders and mobilizing the recommendations coming from patients and families.

A visible commitment of leadership at all levels. Partnering with leadership across Northwell’s system required a delineated vision, clear purpose and ownership, and comprehensive implementation and sustainment strategies. The existing format of Northwell’s PFPC provided the structure and framework needed for engaged patient and family input; the OPCE motivated and organized key areas of involvement and led communication efforts across the organization. The IPFCC coaching calls provided the underlying guidance and accountability needed to sustain momentum. As leadership and frontline teams became aware of the vision, they understood the larger connection to the system’s purpose, which ultimately created a clear path for positive change.

Meaningful involvement and input of patient and family partners. Throughout this project, Northwell’s patient/family partners were involved through the PFPC and local councils. For example, patient/family partners attended every IPFCC coaching call; members had a central voice in every decision made within each SWT; and local PFPCs actively participated in physical signage “walk-abouts” across facilities, making key recommendations for improvement. This multifaceted, supportive collaboration created a rejuvenated and purposeful focus for all council members involved. Some of their reactions include, “…I am so happy to be able to help other families in crisis, so that they don’t have to be alone, like I was,” and “I feel how important the patient and family’s voice is … it’s truly a partnership between patients, families, and staff.”

Regular access to IPFCC as a best practice coach and expert resource. Throughout the 10-month process, IPFCC’s Better Together Learning Community for Hospitals in New York State provided ongoing learning interventions for members of the SWT; multiple and varied resources from the Better Together toolkit for adaptation; and opportunities to share and reinforce new, learned expertise with colleagues within the Northwell Health system and beyond through IPFCC’s free online learning community, PFCC.Connect.

Conclusion

Family presence and participation are important to the quality, experience, safety, and outcomes of care. IPFCC’s campaign, Better Together: Partnering with Families, encourages hospitals to change restrictive visiting policies and, instead, to welcome families and caregivers 24 hours a day.

Two projects within Better Together involving almost 50 acute care hospitals in New York State confirm that change in policy, practice, and communication is particularly effective when implemented with strong support from leadership. An intervention like the Better Together Learning Community, offering structured training, coaching, and resources, can facilitate the change process.

Corresponding author: IPFCC, Deborah L. Dokken, 6917 Arlington Rd., Ste. 309, Bethesda, MD 20814; [email protected].

Funding disclosures: None.

From the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care, Bethesda, MD (Ms. Dokken and Ms. Johnson), and Northwell Health, New Hyde Park, NY (Dr. Barden, Ms. Tuomey, and Ms. Giammarinaro).

Abstract

Objective: To describe the growth of Better Together: Partnering with Families, a campaign launched in 2014 to eliminate restrictive hospital visiting policies and to put in place policies that recognize families as partners in care, and to discuss the processes involved in implementing the initiative in a large, integrated health system.

Methods: Descriptive report.

Results: In June 2014, the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care (IPFCC) launched the Better Together campaign to emphasize the importance of family presence and participation to the quality, experience, safety, and outcomes of care. Since then, this initiative has expanded in both the United States and Canada. With support from 2 funders in the United States, special attention was focused on acute care hospitals across New York State. Nearly 50 hospitals participated in 2 separate but related projects. Fifteen of the hospitals are part of Northwell Health, New York State’s largest health system. Over a 10-month period, these hospitals made significant progress in changing policy, practice, and communication to support family presence.

Conclusion: The Better Together initiative was implemented across a health system with strong support from leadership and the involvement of patient and family advisors. An intervention offering structured training, coaching, and resources, like IPFCC’s Better Together initiative, can facilitate the change process.

Keywords: family presence; visiting policies; patient-centered care; family-centered care; patient experience.

The presence of families at the bedside of patients is often restricted by hospital visiting hours. Hospitals that maintain these restrictive policies cite concerns about negative impacts on security, infection control, privacy, and staff workload. But there are no data to support these concerns, and the experience of hospitals that have successfully changed policy and practice to welcome families demonstrates the potential positive impacts of less restrictive policies on patient care and outcomes.1 For example, hospitalization can lead to reduced cognitive function in elderly patients. Family members would recognize the changes and could provide valuable information to hospital staff, potentially improving outcomes.2

In June 2014, the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care (IPFCC) launched the campaign Better Together: Partnering with Families.3 The campaign is is grounded in patient- and family- centered care, an approach to care that supports partnerships among health care providers, patients, and families, and, among other core principles, advocates that patients define their “families” and how they will participate in care and decision-making.

Emphasizing the importance of family presence and participation to quality and safety, the Better Together campaign seeks to eliminate restrictive visiting policies and calls upon hospitals to include families as members of the care team and to welcome them 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, according to patient preference. As part of the campaign, IPFCC developed an extensive toolkit of resources that is available to hospitals and other organizations at no cost. The resources include sample policies; profiles of hospitals that have implemented family presence policies; educational materials for staff, patients, and families; and a template for hospital websites. This article, a follow-up to an article published in the January 2015 issue of JCOM,1 discusses the growth of the Better Together initiative as well as the processes involved in implementing the initiative across a large health system.

Growth of the Initiative

Since its launch in 2014, the Better Together initiative has continued to expand in the United States and Canada. In Canada, under the leadership of the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement (CFHI), more than 50 organizations have made a commitment to the Better Together program and family presence.4 Utilizing and adapting IPFCC’s Toolkit, CFHI developed a change package of free resources for Canadian organizations.5 Some of the materials, including the Pocket Guide for Families (Manuel des Familles), were translated into French.6

With support from 2 funders in the United States, the United Hospital Fund and the New York State Health (NYSHealth) Foundation, through a subcontract with the New York Public Interest Research Group (NYPIRG), IPFCC has been able to focus on hospitals in New York City, including public hospitals, and, more broadly, acute care hospitals across New York State. Nearly 50 hospitals participated in these 2 separate but related projects.

Education and Support for New York City Hospitals

Supported by the United Hospital Fund, an 18-month project that focused specifically on New York City hospitals was completed in June 2017. The project began with a 1-day intensive training event with representatives of 21 hospitals. Eighteen of those hospitals were eligible to participate in follow-up consultation provided by IPFCC, and 14 participated in some kind of follow-up. NYC Health + Hospitals (H+H), the system of public hospitals in NYC, participated most fully in these activities.

The outcomes of the Better Together initiative in New York City are summarized in the report Sick, Scared, & Separated From Loved Ones,2 which is based on a pre/post review of hospital visitation/family presence policies and website communications. According to the report, hospitals that participated in the IPFCC training and consultation program performed better, as a group, with respect to improved policy and website scores on post review than those that did not. Of the 10 hospitals whose scores improved during the review period, 8 had participated in the IPFCC training and 1 hospital was part of a hospital network that did so. (Six of these hospitals are part of the H+H public hospital system.) Those 9 hospitals saw an average increase in scores of 4.9 points (out of a possible 11).

A Learning Community for Hospitals in New York State

With support from the NYSHealth Foundation, IPFCC again collaborated with NYPIRG and New Yorkers for Patient & Family Empowerment on a 2-year initiative, completed in November 2019, that involved 26 hospitals: 15 from Northwell Health, New York State’s largest health system, and 11 hospitals from health systems throughout the state (Greater Hudson Valley Health System, now Garnet Health; Mohawk Valley Health System; Rochester Regional Health; and University of Vermont Health Network). An update of the report Sick, Scared, & Separated From Loved Onescompared pre/post reviews of policies and website communications regarding hospital visitation/family presence.7 Its findings confirm that hospitals that participated in the Better Together Learning Community improved both their policy and website scores to a greater degree than hospitals that did not participate and that a planned intervention can help facilitate change.

During the survey period, 28 out of 40 hospitals’ website navigability scores improved. Of those, hospitals that did not participate in the Better Together Learning Community saw an average increase in scores of 1.2 points, out of a possible 11, while the participating hospitals saw an average increase of 2.7 points, with the top 5 largest increases in scores belonging to hospitals that participated in the Better Together Learning Community.7

The Northwell Health Experience

Northwell Health is a large integrated health care organization comprising more than 69,000 employees, 23 hospitals, and more than 750 medical practices, located geographically across New York State. Embracing patient- and family-centered care, Northwell is dedicated to improving the quality, experience, and safety of care for patients and their families. Welcoming and including patients, families, and care partners as members of the health care team has always been a core element of Northwell’s organizational goal of providing world-class patient care and experience.

Four years ago, the organization reorganized and formalized a system-wide Patient & Family Partnership Council (PFPC).8 Representatives on the PFPC include a Northwell patient experience leader and patient/family co-chair from local councils that have been established in nearly all 23 hospitals as well as service lines. Modeling partnership, the PFPC is grounded in listening to the “voice” of patients and families and promoting collaboration, with the goal of driving change across varied aspects and experiences of health care delivery.

Through the Office of Patient and Customer Experience (OPCE), a partnership with IPFCC and the Better Together Learning Community for Hospitals in New York State was initiated as a fundamental next step in Northwell’s journey to enhance system-wide family presence and participation. Results from Better Together’s Organizational Self-Assessment Tool and process identified opportunities to influence 3 distinct areas: policy/staff education, position descriptions/performance management, and website/signage. Over a 10-month period (September 2018 through June 2019), 15 Northwell hospitals implemened significant patient- and family-centered improvements through multifaceted shared work teams (SWT) that partnered around the common goal of supporting the patient and family experience (Figure). Northwell’s SWT structure allowed teams to meet individually on specific tasks, led by a dedicated staff member of the OPCE to ensure progress, support, and accountability. Six monthly coaching calls or report-out meetings were attended by participating teams, where feedback and recommendations shared by IPFCC were discussed in order to maintain momentum and results.

Policy/Staff Education

The policy/staff education SWT focused on appraising and updating existing policies to ensure alignment with key patient- and family-centered concepts and Better Together principles (Table 1). By establishing representation on the System Policy and Procedure Committee, OPCE enabled patients and families to have a voice at the decision-making table. OPCE leaders presented the ideology and scope of the transformation to this committee. After reviewing all system-wide policies, 4 were identified as key opportunities for revision. One overarching policy titled “Visitation Guidelines” was reviewed and updated to reflect Northwell’s mission of patient- and family-centered care, retiring the reference to “families” as “visitors” in definitions, incorporating language of inclusion and partnership, and citing other related policies. The policy was vetted through a multilayer process of review and stakeholder feedback and was ultimately approved at a system

Three additional related policies were also updated to reflect core principles of inclusion and partnership. These included system policies focused on discharge planning; identification of health care proxy, agent, support person and caregiver; and standards of behavior not conducive in a health care setting. As a result of this work, OPCE was invited to remain an active member of the System Policy and Procedure Committee, adding meaningful new perspectives to the clinical and administrative policy management process. Once policies were updated and approved, the SWT focused on educating leaders and teams. Using a diversified strategy, education was provided through various modes, including weekly system-wide internal communication channels, patient experience huddle messages, yearly mandatory topics training, and the incorporation of essential concepts in existing educational courses (classroom and e-learning modalities).

Position Descriptions/Performance Management

The position descriptions/performance management SWT focused its efforts on incorporating patient- and family-centered concepts and language into position descriptions and the performance appraisal process (Table 2). Due to the complex nature of this work, the process required collaboration from key subject matter experts in human resources, talent management, corporate compensation, and labor management. In 2019, Northwell began an initiative focused on streamlining and standardizing job titles, roles, and developmental pathways across the system. The overarching goal was to create system-wide consistency and standardization. The SWT was successful in advising the leaders overseeing this job architecture initiative on the importance of including language of patient- and family-centered care, like partnership and collaboration, and of highlighting the critical role of family members as part of the care team in subsequent documents.

Northwell has 6 behavioral expectations, standards to which all team members are held accountable: Patient/Customer Focus, Teamwork, Execution, Organizational Awareness, Enable Change, and Develop Self. As a result of the SWT’s work, Patient/Customer Focus was revised to include “families” as essential care partners, demonstrating Northwell’s ongoing commitment to honoring the role of families as members of the care team. It also ensures that all employees are aligned around this priority, as these expectations are utilized to support areas such as recognition and performance. Collaborating with talent management and organizational development, the SWT reviewed yearly performance management and new-hire evaluations. In doing so, they identified an opportunity to refresh the anchored qualitative rating scales to include behavioral demonstrations of patient- and family-centered care, collaboration, respect, and partnership with family members.

Website/Signage

Websites make an important first impression on patients and families looking for information to best prepare for a hospital experience. Therefore, the website/signage SWT worked to redesign hospital websites, enhance digital signage, and perform a baseline assessment of physical signage across facilities. Initial feedback on Northwell’s websites identified opportunities to include more patient- and family-centered, care-partner-infused language; improve navigation; and streamline click levels for easier access. Content for the websites was carefully crafted in collaboration with Northwell’s internal web team, utilizing IPFCC’s best practice standards as a framework and guide.

Next, a multidisciplinary website shared-governance team was established by the OPCE to ensure that key stakeholders were represented and had the opportunity to review and make recommendations for appropriate language and messaging about family presence and participation. This 13-person team was comprised of patient/family partners, patient-experience culture leaders, quality, compliance, human resources, policy, a chief nursing officer, a medical director, and representation from the Institute for Nursing. After careful review and consideration from Northwell’s family partners and teams, all participating hospital websites were enhanced as of June 2019 to include prominent 1-click access from homepages to information for “patients, families and visitors,” as well as “your care partners” information on the important role of families and care partners.

Along with refreshing websites, another step in Northwell’s work to strengthen messaging about family presence and participation was to partner and collaborate with the system’s digital web team as well as local facility councils to understand the capacity to adjust digital signage across facilities. Opportunities were found to make simple yet effective enhancements to the language and imagery of digital signage upon entry, creating a warmer and more welcoming first impression for patients and families. With patient and family partner feedback, the team designed digital signage with inclusive messaging and images that would circulate appropriately based on the facility. Signage specifically welcomes families and refers to them as members of patients’ care teams.

Northwell’s website/signage SWT also directed a 2-phase physical signage assessment to determine ongoing opportunities to alter signs in areas that particularly impact patients and families, such as emergency departments, main lobbies, cafeterias, surgical waiting areas, and intensive care units. Each hospital’s local PFPC did a “walk-about”9 to make enhancements to physical signage, such as removing paper and overcrowded signs, adjusting negative language, ensuring alignment with brand guidelines, and including language that welcomed families. As a result of the team’s efforts around signage, collaboration began with the health system’s signage committee to help standardize signage terminology to reflect family inclusiveness, and to implement the recommendation for a standardized signage shared-governance team to ensure accountability and a patient- and family-centered structure.

Sustainment

Since implementing Better Together, Northwell has been able to infuse a more patient- and family-centered emphasis into its overall patient experience message of “Every role, every person, every moment matters.” As a strategic tool aimed at encouraging leaders, clinicians, and staff to pause and reflect about the “heart” of their work, patient and family stories are now included at the beginning of meetings, forums, and team huddles. Elements of the initiative have been integrated in current Patient and Family Partnership sustainment plans at participating hospitals. Some highlights include continued integration of patient/family partners on committees and councils that impact areas such as way finding, signage, recruitment, new-hire orientation, and community outreach; focus on enhancing partner retention and development programs; and inclusion of patient- and family-centered care and Better Together principles in ongoing leadership meetings.

Factors Contributing to Success

Health care is a complex, regulated, and often bureaucratic world that can be very difficult for patients and families to navigate. The system’s partnership with the Better Together Learning Community for Hospitals in New York State enhanced its efforts to improve family presence and participation and created powerful synergy. The success of this partnership was based on a number of important factors:

A solid foundation of support, structure, and accountability. The OPCE initiated the IPFCC Better Together partnership and established a synergistic collaboration inclusive of leadership, frontline teams, multiple departments, and patient and family partners. As a major strategic component of Northwell’s mission to deliver high-quality, patient- and family-centered care, OPCE was instrumental in connecting key areas and stakeholders and mobilizing the recommendations coming from patients and families.

A visible commitment of leadership at all levels. Partnering with leadership across Northwell’s system required a delineated vision, clear purpose and ownership, and comprehensive implementation and sustainment strategies. The existing format of Northwell’s PFPC provided the structure and framework needed for engaged patient and family input; the OPCE motivated and organized key areas of involvement and led communication efforts across the organization. The IPFCC coaching calls provided the underlying guidance and accountability needed to sustain momentum. As leadership and frontline teams became aware of the vision, they understood the larger connection to the system’s purpose, which ultimately created a clear path for positive change.

Meaningful involvement and input of patient and family partners. Throughout this project, Northwell’s patient/family partners were involved through the PFPC and local councils. For example, patient/family partners attended every IPFCC coaching call; members had a central voice in every decision made within each SWT; and local PFPCs actively participated in physical signage “walk-abouts” across facilities, making key recommendations for improvement. This multifaceted, supportive collaboration created a rejuvenated and purposeful focus for all council members involved. Some of their reactions include, “…I am so happy to be able to help other families in crisis, so that they don’t have to be alone, like I was,” and “I feel how important the patient and family’s voice is … it’s truly a partnership between patients, families, and staff.”

Regular access to IPFCC as a best practice coach and expert resource. Throughout the 10-month process, IPFCC’s Better Together Learning Community for Hospitals in New York State provided ongoing learning interventions for members of the SWT; multiple and varied resources from the Better Together toolkit for adaptation; and opportunities to share and reinforce new, learned expertise with colleagues within the Northwell Health system and beyond through IPFCC’s free online learning community, PFCC.Connect.

Conclusion

Family presence and participation are important to the quality, experience, safety, and outcomes of care. IPFCC’s campaign, Better Together: Partnering with Families, encourages hospitals to change restrictive visiting policies and, instead, to welcome families and caregivers 24 hours a day.

Two projects within Better Together involving almost 50 acute care hospitals in New York State confirm that change in policy, practice, and communication is particularly effective when implemented with strong support from leadership. An intervention like the Better Together Learning Community, offering structured training, coaching, and resources, can facilitate the change process.

Corresponding author: IPFCC, Deborah L. Dokken, 6917 Arlington Rd., Ste. 309, Bethesda, MD 20814; [email protected].

Funding disclosures: None.

1. Dokken DL, Kaufman J, Johnson BJ et al. Changing hospital visiting policies: from families as “visitors” to families as partners. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2015; 22:29-36.

2. New York Public Interest Research Group and New Yorkers for Patient & Family Empowerment. Sick, scared and separated from loved ones. third edition: A pathway to improvement in New York City. New York: NYPIRG: 2018. www.nypirg.org/pubs/201801/NYPIRG_SICK_SCARED_FINAL.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2019.

3. Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Better Together: Partnering with Families. www.ipfcc.org/bestpractices/better-together.html. Accessed December 12, 2019.

4. Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement. Better Together. www.cfhi-fcass.ca/WhatWeDo/better-together. Accessed December 12, 2019.

5. Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement. Better Together: A change package to support the adoption of family presence and participation in acute care hospitals and accelerate healthcare improvement. www.cfhi-fcass.ca/sf-docs/default-source/patient-engagement/better-together-change-package.pdf?sfvrsn=9656d044_4. Accessed December 12, 2019.

6. Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement. L’Objectif santé: main dans la main avec les familles. www.cfhi-fcass.ca/sf-docs/default-source/patient-engagement/families-pocket-screen_fr.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2019.

7. New York Public Interest Research Group and New Yorkers for Patient & Family Empowerment. Sick, scared and separated from loved ones. fourth edition: A pathway to improvement in New York. New York: NYPIRG: 2019. www.nypirg.org/pubs/201911/Sick_Scared_Separated_2019_web_FINAL.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2019.

8. Northwell Health. Patient and Family Partnership Councils. www.northwell.edu/about/commitment-to-excellence/patient-and-customer-experience/care-delivery-hospitality. Accessed December 12, 2019.

9 . Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. How to conduct a “walk-about” from the patient and family perspective. www.ipfcc.org/resources/How_To_Conduct_A_Walk-About.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2019.

1. Dokken DL, Kaufman J, Johnson BJ et al. Changing hospital visiting policies: from families as “visitors” to families as partners. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2015; 22:29-36.

2. New York Public Interest Research Group and New Yorkers for Patient & Family Empowerment. Sick, scared and separated from loved ones. third edition: A pathway to improvement in New York City. New York: NYPIRG: 2018. www.nypirg.org/pubs/201801/NYPIRG_SICK_SCARED_FINAL.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2019.

3. Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Better Together: Partnering with Families. www.ipfcc.org/bestpractices/better-together.html. Accessed December 12, 2019.

4. Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement. Better Together. www.cfhi-fcass.ca/WhatWeDo/better-together. Accessed December 12, 2019.

5. Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement. Better Together: A change package to support the adoption of family presence and participation in acute care hospitals and accelerate healthcare improvement. www.cfhi-fcass.ca/sf-docs/default-source/patient-engagement/better-together-change-package.pdf?sfvrsn=9656d044_4. Accessed December 12, 2019.

6. Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement. L’Objectif santé: main dans la main avec les familles. www.cfhi-fcass.ca/sf-docs/default-source/patient-engagement/families-pocket-screen_fr.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2019.

7. New York Public Interest Research Group and New Yorkers for Patient & Family Empowerment. Sick, scared and separated from loved ones. fourth edition: A pathway to improvement in New York. New York: NYPIRG: 2019. www.nypirg.org/pubs/201911/Sick_Scared_Separated_2019_web_FINAL.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2019.

8. Northwell Health. Patient and Family Partnership Councils. www.northwell.edu/about/commitment-to-excellence/patient-and-customer-experience/care-delivery-hospitality. Accessed December 12, 2019.

9 . Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. How to conduct a “walk-about” from the patient and family perspective. www.ipfcc.org/resources/How_To_Conduct_A_Walk-About.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2019.

When Horses and Zebras Coexist: Achieving Diagnostic Excellence in the Age of High-Value Care

Safe, timely, and efficient diagnosis is fundamental for high-quality, effective healthcare. Why is diagnosis so important? First, it informs the two other main areas of medical decision-making: treatment and prognosis. These are the means by which physicians can actually change health outcomes for patients, as well as ensure that patients and their families have a realistic and accurate understanding of what the future holds with respect to their health. Second, patients and families tend to feel a sense of closure from having a name and an explanation for symptoms, even in the absence of specific treatment. Proper labeling allows patients and families to connect with others with the same diagnosis, who are best positioned to offer empathy by virtue of their similar experiences.

Despite the fundamental role of diagnosis, diagnostic error is pervasive in medicine, with unacceptable levels of resultant harm.1 In 2015, the Institute of Medicine published a landmark report, “Improving Diagnosis in Health Care,” bringing the problem to the forefront of the minds of healthcare professionals and the general public alike. According to the report, “improving the diagnostic process…represents a moral, professional, and public health imperative.”1 We must do more than avoid diagnostic error, however—we must aim to achieve diagnostic excellence. Not getting it wrong is not enough.

There are real challenges to achieving diagnostic safety, let alone excellence. The “churn” of modern hospital medicine does not reward deep diagnostic thought, nor does it often encourage reflection or collaboration, important components of being able to achieve diagnostic excellence.2 Furthermore, despite their years of training, physicians often have difficulty applying probabilistic reasoning and appropriately incorporating diagnostic information in the best evidence-based manner.3,4 In addition, there are no validated measures of diagnostic performance in practice. It is telling that many hospitalists, despite a professed interest in complex diagnosis, would rather be assigned to care for a patient with cellulitis than a patient with a complicated differential diagnosis.

Given these challenges, how can the modern healthcare ecosystem be changed to achieve diagnostic excellence? In this month’s issue of Journal of Hospital Medicine, Singer and colleagues describe a pilot project of a proposed solution to the problem.5 Aptly named, the Socrates Project is an intervention that makes available a team of “diagnosticians” that can be consulted for assistance with challenging diagnostic cases. The physicians on the team volunteer their time, allowing for deep diagnostic evaluation that is not limited by one’s daily workload, thus overcoming one of the major hurdles to achieving diagnostic excellence. The described program also focuses on harnessing the power of teamwork, which is especially relevant given recent descriptions of the effectiveness of collective intelligence in improving diagnostic performance.6 Importantly, the authors recognize that their intervention will not achieve a diagnosis in every case for which they are consulted; rather, they hope that their thorough evaluation will uncover additional potential diagnostic avenues for the referring team to pursue, with a goal to “improve patient care by providing…ideas to reduce—or at least manage—diagnostic uncertainty.”

Programs of this nature are exciting for hospitalists. Hospital medicine is, perhaps, a place in modern medicine where diagnostic excellence has a natural home. Patients admitted to the hospital are acutely (and often severely) ill, and hospitalists are tasked with rapidly identifying the cause of their illness in order to initiate appropriate treatment and accurately inform prognosis. Hospitalists, as generalists, take a broad approach to challenging cases, and they tend to practice in well-resourced environments with nearly every diagnostic modality at their disposal. Many hospitalists would envy participating in a program such as the Socrates Project.

While Singer et al.’s innovation—and the institutional support thereof—should be lauded, some discussion must be had about how to assess the effectiveness of such a program. The authors acknowledge the need for evaluation of both the diagnostic process and the outcomes that process achieves. Measuring diagnostic performance is challenging, however, and while there is substantial progress being made in this area, recent efforts tend to focus on identifying diagnostic errors rather than measuring diagnostic excellence. Moreover, even if a program does improve diagnostic performance, how should we evaluate for unintended consequences of its implementation? In the age of high-value care, how can we ensure that efforts to do a better job of spotting proverbial zebras do not come at the cost of harming too many horses?7

Hospitalists are well primed to answer this question. The juxtaposition of Singer et al.’s article with the Journal of Hospital Medicine’s long-running series on Choosing Wisely®: Things We Do for No Reason™ provides a natural synergy to begin crafting a framework to evaluate unintended consequences of a program in diagnostic excellence. More diagnosis is not the goal; more appropriate diagnosis is what is needed. A clinical program aimed at achieving diagnostic excellence should not employ low-value, wasteful strategies that do not add substantively to the diagnostic process but should instead seek to improve the overall efficiency of even complicated diagnostic odysseys. Avoiding waste throughout will allow for allocation of diagnostic resources where they are needed. In turn, hospitalists can do a better job of correctly identifying both horses and zebras for what they are. While a given hospitalization for a diagnostically complex patient may be relatively expensive, better diagnosis during an index hospitalization is likely to lead to decreased downstream costs, such as those related to readmissions and further testing, as well as better health outcomes.

The Socrates Project, along with similar programs at other institutions, are exciting innovations. These programs are not only likely to be good for patients but are also good for hospitalists. The field of hospital medicine should leverage its collective expertise in clinical medicine, systems of care, and high-value care to become a home for diagnostic excellence.

1. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Improving Diagnosis in Health Care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2015. https://doi.org/10.17226/21794

2. Olson A, Rencic J, Cosby K, et al. Competencies for improving diagnosis: an interprofessional framework for education and training in health care. Diagnosis. 2019;6(4):335-341. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2018-0107.