User login

Overlap between Medicare’s Voluntary Bundled Payment and Accountable Care Organization Programs

Voluntary accountable care organizations (ACOs) and bundled payments have concurrently become cornerstone strategies in Medicare’s shift from volume-based fee-for-service toward value-based payment.

Physician practice and hospital participation in Medicare’s largest ACO model, the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP),1 grew to include 561 organizations in 2018. Under MSSP, participants assume financial accountability for the global quality and costs of care for defined populations of Medicare fee-for-service patients. ACOs that manage to maintain or improve quality while achieving savings (ie, containing costs below a predefined population-wide spending benchmark) are eligible to receive a portion of the difference back from Medicare in the form of “shared savings”.

Similarly, hospital participation in Medicare’s bundled payment programs has grown over time. Most notably, more than 700 participants enrolled in the recently concluded Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative,2 Medicare’s largest bundled payment program over the past five years.3 Under BPCI, participants assumed financial accountability for the quality and costs of care for all Medicare patients triggering a qualifying “episode of care”. Participants that limit episode spending below a predefined benchmark without compromising quality were eligible for financial incentives.

As both ACOs and bundled payments grow in prominence and scale, they may increasingly overlap if patients attributed to ACOs receive care at bundled payment hospitals. Overlap could create synergies by increasing incentives to address shared processes (eg, discharge planning) or outcomes (eg, readmissions).4 An ACO focus on reducing hospital admissions could complement bundled payment efforts to increase hospital efficiency.

Conversely, Medicare’s approach to allocating savings and losses can penalize ACOs or bundled payment participants.3 For example, when a patient included in an MSSP ACO population receives episodic care at a hospital participating in BPCI, the historical costs of care for the hospital and the episode type, not the actual costs of care for that specific patient and his/her episode, are counted in the performance of the ACO. In other words, in these cases, the performance of the MSSP ACO is dependent on the historical spending at BPCI hospitals—despite it being out of ACO’s control and having little to do with the actual care its patients receive at BPCI hospitals—and MSSP ACOs cannot benefit from improvements over time. Therefore, MSSP ACOs may be functionally penalized if patients receive care at historically high-cost BPCI hospitals regardless of whether they have considerably improved the value of care delivered. As a corollary, Medicare rules involve a “claw back” stipulation in which savings are recouped from hospitals that participate in both BPCI and MSSP, effectively discouraging participation in both payment models.

Although these dynamics are complex, they highlight an intuitive point that has gained increasing awareness,5 ie, policymakers must understand the magnitude of overlap to evaluate the urgency in coordinating between the payment models. Our objective was to describe the extent of overlap and the characteristics of patients affected by it.

METHODS

We used 100% institutional Medicare claims, MSSP beneficiary attribution, and BPCI hospital data to identify fee-for-service beneficiaries attributed to MSSP and/or receiving care at BPCI hospitals for its 48 included episodes from the start of BPCI in 2013 quarter 4 through 2016 quarter 4.

We examined the trends in the number of episodes across the following three groups: MSSP-attributed patients hospitalized at BPCI hospitals for an episode included in BPCI (Overlap), MSSP-attributed patients hospitalized for that episode at non-BPCI hospitals (MSSP-only), and non-MSSP-attributed patients hospitalized at BPCI hospitals for a BPCI episode (BPCI-only). We used Medicare and United States Census Bureau data to compare groups with respect to sociodemographic (eg, age, sex, residence in a low-income area),6 clinical (eg, Elixhauser comorbidity index),7 and prior utilization (eg, skilled nursing facility discharge) characteristics.

Categorical and continuous variables were compared using logistic regression and one-way analysis of variance, respectively. Analyses were performed using Stata (StataCorp, College Station, Texas), version 15.0. Statistical tests were 2-tailed and significant at α = 0.05. This study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Pennsylvania.

RESULTS

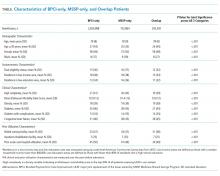

The number of MSSP ACOs increased from 220 in 2013 to 432 in 2016. The number of BPCI hospitals increased from 9 to 389 over this period, peaking at 413 hospitals in 2015. Over our study period, a total of 243,392, 2,824,898, and 702,864 episodes occurred in the Overlap, ACO-only, and BPCI-only groups, respectively (Table). Among episodes, patients in the Overlap group generally showed lower severity than those in other groups, although the differences were small. The BPCI-only, MSSP-only, and Overlap groups also exhibited small differences with respect to other characteristics such as the proportion of patients with Medicare/Medicaid dual-eligibility (15% of individual vs 16% and 12%, respectively) and prior use of skilled nursing facilities (33% vs 34% vs 31%, respectively) and acute care hospitals (45% vs 41% vs 39%, respectively) (P < .001 for all).

The overall overlap facing MSSP patients (overlap as a proportion of all MSSP patients) increased from 0.3% at the end of 2013 to 10% at the end of 2016, whereas over the same period, overlap facing bundled payment patients (overlap as a proportion of all bundled payment patients) increased from 11.9% to 27% (Appendix Figure). Overlap facing MSSP ACOs varied according to episode type, ranging from 3% for both acute myocardial infarction and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease episodes to 18% for automatic implantable cardiac defibrillator episodes at the end of 2016. Similarly, overlap facing bundled payment patients varied from 21% for spinal fusion episodes to 32% for lower extremity joint replacement and automatic implantable cardiac defibrillator episodes.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe the sizable and growing overlap facing ACOs with attributed patients who receive care at bundled payment hospitals, as well as bundled payment hospitals that treat patients attributed to ACOs.

The major implication of our findings is that policymakers must address and anticipate forthcoming payment model overlap as a key policy priority. Given the emphasis on ACOs and bundled payments as payment models—for example, Medicare continues to implement both nationwide via the Next Generation ACO model8 and the recently launched BPCI-Advanced program9—policymakers urgently need insights about the extent of payment model overlap. In that context, it is notable that although we have evaluated MSSP and BPCI as flagship programs, true overlap may actually be greater once other programs are considered.

Several factors may underlie the differences in the magnitude of overlap facing bundled payment versus ACO patients. The models differ in how they identify relevant patient populations, with patients falling under bundled payments via hospitalization for certain episode types but patients falling under ACOs via attribution based on the plurality of primary care services. Furthermore, BPCI participation lagged behind MSSP participation in time, while also occurring disproportionately in areas with existing MSSP ACOs.

Given these findings, understanding the implications of overlap should be a priority for future research and policy strategies. Potential policy considerations should include revising cost accounting processes so that when ACO-attributed patients receive episodic care at bundled payment hospitals, actual rather than historical hospital costs are counted toward ACO cost performance. To encourage hospitals to assume more accountability over outcomes—the ostensible overarching goal of value-based payment reform—Medicare could elect not to recoup savings from hospitals in both payment models. Although such changes require careful accounting to protect Medicare from financial losses as it forgoes some savings achieved through payment reforms, this may be worthwhile if hospital engagement in both models yields synergies.

Importantly, any policy changes made to address program overlap would need to accommodate ongoing changes in ACO, bundled payments, and other payment programs. For example, Medicare overhauled MSSP in December 2018. Compared to the earlier rules, in which ACOs could avoid downside financial risk altogether via “upside only” arrangements for up to six years, new MSSP rules require all participants to assume downside risk after several years of participation. Separately, forthcoming payment reforms such as direct contracting10 may draw clinicians and hospitals previously not participating in either Medicare fee-for-service or value-based payment models into payment reform. These factors may affect overlap in unpredictable ways (eg, they may increase the overlap by increasing the number of patients whose care is covered by different payment models or they may decrease overlap by raising the financial stakes of payment reforms to a degree that organizations drop out altogether).

This study has limitations. First, generalizability is limited by the fact that our analysis did not include bundled payment episodes assigned to physician group participants in BPCI or hospitals in mandatory joint replacement bundles under the Medicare Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement model.11 Second, although this study provides the first description of overlap between ACO and bundled payment programs, it was descriptive in nature. Future research is needed to evaluate the impact of overlap on clinical, quality, and cost outcomes. This is particularly important because although we observed only small differences in patient characteristics among MSSP-only, BPCI-only, and Overlap groups, characteristics could change differentially over time. Payment reforms must be carefully monitored for potentially unintended consequences that could arise from differential changes in patient characteristics (eg, cherry-picking behavior that is disadvantageous to vulnerable individuals).

Nonetheless, this study underscores the importance and extent of overlap and the urgency to consider policy measures to coordinate between the payment models.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank research assistance from Sandra Vanderslice who did not receive any compensation for her work. This research was supported in part by The Commonwealth Fund. Rachel Werner was supported in part by K24-AG047908 from the NIA.

1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Shared Savings Program. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-For-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/index.html. Accessed July 22, 2019.

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative: General Information. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments/. Accessed July 22, 2019.

3. Mechanic RE. When new Medicare payment systems collide. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(18):1706-1709. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1601464.

4. Ryan AM, Krinsky S, Adler-Milstein J, Damberg CL, Maurer KA, Hollingsworth JM. Association between hospitals’ engagement in value-based reforms and readmission reduction in the hospital readmission reduction program. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(6):863-868. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0518.

5. Liao JM, Dykstra SE, Werner RM, Navathe AS. BPCI Advanced will further emphasize the need to address overlap between bundled payments and accountable care organizations. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20180409.159181/full/. Accessed May 14, 2019.

6. Census Bureau. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/. Accessed May 14, 2018.

7. van Walraven C, Austin PC, Jennings A, Quan H, Forster AJ. A modification of the elixhauser comorbidity measures into a point system for hospital death using administrative data. Med Care. 2009;47(6):626-633. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819432e5.

8. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Next, Generation ACO Model. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/next-generation-aco-model/. Accessed July 22, 2019.

9. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. BPCI Advanced. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bpci-advanced. Accessed July 22, 2019.

10. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Direct Contracting. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/direct-contracting. Accessed July 22, 2019.

11. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/CJR. Accessed July 22, 2019.

Voluntary accountable care organizations (ACOs) and bundled payments have concurrently become cornerstone strategies in Medicare’s shift from volume-based fee-for-service toward value-based payment.

Physician practice and hospital participation in Medicare’s largest ACO model, the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP),1 grew to include 561 organizations in 2018. Under MSSP, participants assume financial accountability for the global quality and costs of care for defined populations of Medicare fee-for-service patients. ACOs that manage to maintain or improve quality while achieving savings (ie, containing costs below a predefined population-wide spending benchmark) are eligible to receive a portion of the difference back from Medicare in the form of “shared savings”.

Similarly, hospital participation in Medicare’s bundled payment programs has grown over time. Most notably, more than 700 participants enrolled in the recently concluded Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative,2 Medicare’s largest bundled payment program over the past five years.3 Under BPCI, participants assumed financial accountability for the quality and costs of care for all Medicare patients triggering a qualifying “episode of care”. Participants that limit episode spending below a predefined benchmark without compromising quality were eligible for financial incentives.

As both ACOs and bundled payments grow in prominence and scale, they may increasingly overlap if patients attributed to ACOs receive care at bundled payment hospitals. Overlap could create synergies by increasing incentives to address shared processes (eg, discharge planning) or outcomes (eg, readmissions).4 An ACO focus on reducing hospital admissions could complement bundled payment efforts to increase hospital efficiency.

Conversely, Medicare’s approach to allocating savings and losses can penalize ACOs or bundled payment participants.3 For example, when a patient included in an MSSP ACO population receives episodic care at a hospital participating in BPCI, the historical costs of care for the hospital and the episode type, not the actual costs of care for that specific patient and his/her episode, are counted in the performance of the ACO. In other words, in these cases, the performance of the MSSP ACO is dependent on the historical spending at BPCI hospitals—despite it being out of ACO’s control and having little to do with the actual care its patients receive at BPCI hospitals—and MSSP ACOs cannot benefit from improvements over time. Therefore, MSSP ACOs may be functionally penalized if patients receive care at historically high-cost BPCI hospitals regardless of whether they have considerably improved the value of care delivered. As a corollary, Medicare rules involve a “claw back” stipulation in which savings are recouped from hospitals that participate in both BPCI and MSSP, effectively discouraging participation in both payment models.

Although these dynamics are complex, they highlight an intuitive point that has gained increasing awareness,5 ie, policymakers must understand the magnitude of overlap to evaluate the urgency in coordinating between the payment models. Our objective was to describe the extent of overlap and the characteristics of patients affected by it.

METHODS

We used 100% institutional Medicare claims, MSSP beneficiary attribution, and BPCI hospital data to identify fee-for-service beneficiaries attributed to MSSP and/or receiving care at BPCI hospitals for its 48 included episodes from the start of BPCI in 2013 quarter 4 through 2016 quarter 4.

We examined the trends in the number of episodes across the following three groups: MSSP-attributed patients hospitalized at BPCI hospitals for an episode included in BPCI (Overlap), MSSP-attributed patients hospitalized for that episode at non-BPCI hospitals (MSSP-only), and non-MSSP-attributed patients hospitalized at BPCI hospitals for a BPCI episode (BPCI-only). We used Medicare and United States Census Bureau data to compare groups with respect to sociodemographic (eg, age, sex, residence in a low-income area),6 clinical (eg, Elixhauser comorbidity index),7 and prior utilization (eg, skilled nursing facility discharge) characteristics.

Categorical and continuous variables were compared using logistic regression and one-way analysis of variance, respectively. Analyses were performed using Stata (StataCorp, College Station, Texas), version 15.0. Statistical tests were 2-tailed and significant at α = 0.05. This study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Pennsylvania.

RESULTS

The number of MSSP ACOs increased from 220 in 2013 to 432 in 2016. The number of BPCI hospitals increased from 9 to 389 over this period, peaking at 413 hospitals in 2015. Over our study period, a total of 243,392, 2,824,898, and 702,864 episodes occurred in the Overlap, ACO-only, and BPCI-only groups, respectively (Table). Among episodes, patients in the Overlap group generally showed lower severity than those in other groups, although the differences were small. The BPCI-only, MSSP-only, and Overlap groups also exhibited small differences with respect to other characteristics such as the proportion of patients with Medicare/Medicaid dual-eligibility (15% of individual vs 16% and 12%, respectively) and prior use of skilled nursing facilities (33% vs 34% vs 31%, respectively) and acute care hospitals (45% vs 41% vs 39%, respectively) (P < .001 for all).

The overall overlap facing MSSP patients (overlap as a proportion of all MSSP patients) increased from 0.3% at the end of 2013 to 10% at the end of 2016, whereas over the same period, overlap facing bundled payment patients (overlap as a proportion of all bundled payment patients) increased from 11.9% to 27% (Appendix Figure). Overlap facing MSSP ACOs varied according to episode type, ranging from 3% for both acute myocardial infarction and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease episodes to 18% for automatic implantable cardiac defibrillator episodes at the end of 2016. Similarly, overlap facing bundled payment patients varied from 21% for spinal fusion episodes to 32% for lower extremity joint replacement and automatic implantable cardiac defibrillator episodes.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe the sizable and growing overlap facing ACOs with attributed patients who receive care at bundled payment hospitals, as well as bundled payment hospitals that treat patients attributed to ACOs.

The major implication of our findings is that policymakers must address and anticipate forthcoming payment model overlap as a key policy priority. Given the emphasis on ACOs and bundled payments as payment models—for example, Medicare continues to implement both nationwide via the Next Generation ACO model8 and the recently launched BPCI-Advanced program9—policymakers urgently need insights about the extent of payment model overlap. In that context, it is notable that although we have evaluated MSSP and BPCI as flagship programs, true overlap may actually be greater once other programs are considered.

Several factors may underlie the differences in the magnitude of overlap facing bundled payment versus ACO patients. The models differ in how they identify relevant patient populations, with patients falling under bundled payments via hospitalization for certain episode types but patients falling under ACOs via attribution based on the plurality of primary care services. Furthermore, BPCI participation lagged behind MSSP participation in time, while also occurring disproportionately in areas with existing MSSP ACOs.

Given these findings, understanding the implications of overlap should be a priority for future research and policy strategies. Potential policy considerations should include revising cost accounting processes so that when ACO-attributed patients receive episodic care at bundled payment hospitals, actual rather than historical hospital costs are counted toward ACO cost performance. To encourage hospitals to assume more accountability over outcomes—the ostensible overarching goal of value-based payment reform—Medicare could elect not to recoup savings from hospitals in both payment models. Although such changes require careful accounting to protect Medicare from financial losses as it forgoes some savings achieved through payment reforms, this may be worthwhile if hospital engagement in both models yields synergies.

Importantly, any policy changes made to address program overlap would need to accommodate ongoing changes in ACO, bundled payments, and other payment programs. For example, Medicare overhauled MSSP in December 2018. Compared to the earlier rules, in which ACOs could avoid downside financial risk altogether via “upside only” arrangements for up to six years, new MSSP rules require all participants to assume downside risk after several years of participation. Separately, forthcoming payment reforms such as direct contracting10 may draw clinicians and hospitals previously not participating in either Medicare fee-for-service or value-based payment models into payment reform. These factors may affect overlap in unpredictable ways (eg, they may increase the overlap by increasing the number of patients whose care is covered by different payment models or they may decrease overlap by raising the financial stakes of payment reforms to a degree that organizations drop out altogether).

This study has limitations. First, generalizability is limited by the fact that our analysis did not include bundled payment episodes assigned to physician group participants in BPCI or hospitals in mandatory joint replacement bundles under the Medicare Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement model.11 Second, although this study provides the first description of overlap between ACO and bundled payment programs, it was descriptive in nature. Future research is needed to evaluate the impact of overlap on clinical, quality, and cost outcomes. This is particularly important because although we observed only small differences in patient characteristics among MSSP-only, BPCI-only, and Overlap groups, characteristics could change differentially over time. Payment reforms must be carefully monitored for potentially unintended consequences that could arise from differential changes in patient characteristics (eg, cherry-picking behavior that is disadvantageous to vulnerable individuals).

Nonetheless, this study underscores the importance and extent of overlap and the urgency to consider policy measures to coordinate between the payment models.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank research assistance from Sandra Vanderslice who did not receive any compensation for her work. This research was supported in part by The Commonwealth Fund. Rachel Werner was supported in part by K24-AG047908 from the NIA.

Voluntary accountable care organizations (ACOs) and bundled payments have concurrently become cornerstone strategies in Medicare’s shift from volume-based fee-for-service toward value-based payment.

Physician practice and hospital participation in Medicare’s largest ACO model, the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP),1 grew to include 561 organizations in 2018. Under MSSP, participants assume financial accountability for the global quality and costs of care for defined populations of Medicare fee-for-service patients. ACOs that manage to maintain or improve quality while achieving savings (ie, containing costs below a predefined population-wide spending benchmark) are eligible to receive a portion of the difference back from Medicare in the form of “shared savings”.

Similarly, hospital participation in Medicare’s bundled payment programs has grown over time. Most notably, more than 700 participants enrolled in the recently concluded Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative,2 Medicare’s largest bundled payment program over the past five years.3 Under BPCI, participants assumed financial accountability for the quality and costs of care for all Medicare patients triggering a qualifying “episode of care”. Participants that limit episode spending below a predefined benchmark without compromising quality were eligible for financial incentives.

As both ACOs and bundled payments grow in prominence and scale, they may increasingly overlap if patients attributed to ACOs receive care at bundled payment hospitals. Overlap could create synergies by increasing incentives to address shared processes (eg, discharge planning) or outcomes (eg, readmissions).4 An ACO focus on reducing hospital admissions could complement bundled payment efforts to increase hospital efficiency.

Conversely, Medicare’s approach to allocating savings and losses can penalize ACOs or bundled payment participants.3 For example, when a patient included in an MSSP ACO population receives episodic care at a hospital participating in BPCI, the historical costs of care for the hospital and the episode type, not the actual costs of care for that specific patient and his/her episode, are counted in the performance of the ACO. In other words, in these cases, the performance of the MSSP ACO is dependent on the historical spending at BPCI hospitals—despite it being out of ACO’s control and having little to do with the actual care its patients receive at BPCI hospitals—and MSSP ACOs cannot benefit from improvements over time. Therefore, MSSP ACOs may be functionally penalized if patients receive care at historically high-cost BPCI hospitals regardless of whether they have considerably improved the value of care delivered. As a corollary, Medicare rules involve a “claw back” stipulation in which savings are recouped from hospitals that participate in both BPCI and MSSP, effectively discouraging participation in both payment models.

Although these dynamics are complex, they highlight an intuitive point that has gained increasing awareness,5 ie, policymakers must understand the magnitude of overlap to evaluate the urgency in coordinating between the payment models. Our objective was to describe the extent of overlap and the characteristics of patients affected by it.

METHODS

We used 100% institutional Medicare claims, MSSP beneficiary attribution, and BPCI hospital data to identify fee-for-service beneficiaries attributed to MSSP and/or receiving care at BPCI hospitals for its 48 included episodes from the start of BPCI in 2013 quarter 4 through 2016 quarter 4.

We examined the trends in the number of episodes across the following three groups: MSSP-attributed patients hospitalized at BPCI hospitals for an episode included in BPCI (Overlap), MSSP-attributed patients hospitalized for that episode at non-BPCI hospitals (MSSP-only), and non-MSSP-attributed patients hospitalized at BPCI hospitals for a BPCI episode (BPCI-only). We used Medicare and United States Census Bureau data to compare groups with respect to sociodemographic (eg, age, sex, residence in a low-income area),6 clinical (eg, Elixhauser comorbidity index),7 and prior utilization (eg, skilled nursing facility discharge) characteristics.

Categorical and continuous variables were compared using logistic regression and one-way analysis of variance, respectively. Analyses were performed using Stata (StataCorp, College Station, Texas), version 15.0. Statistical tests were 2-tailed and significant at α = 0.05. This study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Pennsylvania.

RESULTS

The number of MSSP ACOs increased from 220 in 2013 to 432 in 2016. The number of BPCI hospitals increased from 9 to 389 over this period, peaking at 413 hospitals in 2015. Over our study period, a total of 243,392, 2,824,898, and 702,864 episodes occurred in the Overlap, ACO-only, and BPCI-only groups, respectively (Table). Among episodes, patients in the Overlap group generally showed lower severity than those in other groups, although the differences were small. The BPCI-only, MSSP-only, and Overlap groups also exhibited small differences with respect to other characteristics such as the proportion of patients with Medicare/Medicaid dual-eligibility (15% of individual vs 16% and 12%, respectively) and prior use of skilled nursing facilities (33% vs 34% vs 31%, respectively) and acute care hospitals (45% vs 41% vs 39%, respectively) (P < .001 for all).

The overall overlap facing MSSP patients (overlap as a proportion of all MSSP patients) increased from 0.3% at the end of 2013 to 10% at the end of 2016, whereas over the same period, overlap facing bundled payment patients (overlap as a proportion of all bundled payment patients) increased from 11.9% to 27% (Appendix Figure). Overlap facing MSSP ACOs varied according to episode type, ranging from 3% for both acute myocardial infarction and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease episodes to 18% for automatic implantable cardiac defibrillator episodes at the end of 2016. Similarly, overlap facing bundled payment patients varied from 21% for spinal fusion episodes to 32% for lower extremity joint replacement and automatic implantable cardiac defibrillator episodes.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe the sizable and growing overlap facing ACOs with attributed patients who receive care at bundled payment hospitals, as well as bundled payment hospitals that treat patients attributed to ACOs.

The major implication of our findings is that policymakers must address and anticipate forthcoming payment model overlap as a key policy priority. Given the emphasis on ACOs and bundled payments as payment models—for example, Medicare continues to implement both nationwide via the Next Generation ACO model8 and the recently launched BPCI-Advanced program9—policymakers urgently need insights about the extent of payment model overlap. In that context, it is notable that although we have evaluated MSSP and BPCI as flagship programs, true overlap may actually be greater once other programs are considered.

Several factors may underlie the differences in the magnitude of overlap facing bundled payment versus ACO patients. The models differ in how they identify relevant patient populations, with patients falling under bundled payments via hospitalization for certain episode types but patients falling under ACOs via attribution based on the plurality of primary care services. Furthermore, BPCI participation lagged behind MSSP participation in time, while also occurring disproportionately in areas with existing MSSP ACOs.

Given these findings, understanding the implications of overlap should be a priority for future research and policy strategies. Potential policy considerations should include revising cost accounting processes so that when ACO-attributed patients receive episodic care at bundled payment hospitals, actual rather than historical hospital costs are counted toward ACO cost performance. To encourage hospitals to assume more accountability over outcomes—the ostensible overarching goal of value-based payment reform—Medicare could elect not to recoup savings from hospitals in both payment models. Although such changes require careful accounting to protect Medicare from financial losses as it forgoes some savings achieved through payment reforms, this may be worthwhile if hospital engagement in both models yields synergies.

Importantly, any policy changes made to address program overlap would need to accommodate ongoing changes in ACO, bundled payments, and other payment programs. For example, Medicare overhauled MSSP in December 2018. Compared to the earlier rules, in which ACOs could avoid downside financial risk altogether via “upside only” arrangements for up to six years, new MSSP rules require all participants to assume downside risk after several years of participation. Separately, forthcoming payment reforms such as direct contracting10 may draw clinicians and hospitals previously not participating in either Medicare fee-for-service or value-based payment models into payment reform. These factors may affect overlap in unpredictable ways (eg, they may increase the overlap by increasing the number of patients whose care is covered by different payment models or they may decrease overlap by raising the financial stakes of payment reforms to a degree that organizations drop out altogether).

This study has limitations. First, generalizability is limited by the fact that our analysis did not include bundled payment episodes assigned to physician group participants in BPCI or hospitals in mandatory joint replacement bundles under the Medicare Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement model.11 Second, although this study provides the first description of overlap between ACO and bundled payment programs, it was descriptive in nature. Future research is needed to evaluate the impact of overlap on clinical, quality, and cost outcomes. This is particularly important because although we observed only small differences in patient characteristics among MSSP-only, BPCI-only, and Overlap groups, characteristics could change differentially over time. Payment reforms must be carefully monitored for potentially unintended consequences that could arise from differential changes in patient characteristics (eg, cherry-picking behavior that is disadvantageous to vulnerable individuals).

Nonetheless, this study underscores the importance and extent of overlap and the urgency to consider policy measures to coordinate between the payment models.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank research assistance from Sandra Vanderslice who did not receive any compensation for her work. This research was supported in part by The Commonwealth Fund. Rachel Werner was supported in part by K24-AG047908 from the NIA.

1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Shared Savings Program. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-For-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/index.html. Accessed July 22, 2019.

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative: General Information. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments/. Accessed July 22, 2019.

3. Mechanic RE. When new Medicare payment systems collide. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(18):1706-1709. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1601464.

4. Ryan AM, Krinsky S, Adler-Milstein J, Damberg CL, Maurer KA, Hollingsworth JM. Association between hospitals’ engagement in value-based reforms and readmission reduction in the hospital readmission reduction program. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(6):863-868. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0518.

5. Liao JM, Dykstra SE, Werner RM, Navathe AS. BPCI Advanced will further emphasize the need to address overlap between bundled payments and accountable care organizations. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20180409.159181/full/. Accessed May 14, 2019.

6. Census Bureau. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/. Accessed May 14, 2018.

7. van Walraven C, Austin PC, Jennings A, Quan H, Forster AJ. A modification of the elixhauser comorbidity measures into a point system for hospital death using administrative data. Med Care. 2009;47(6):626-633. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819432e5.

8. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Next, Generation ACO Model. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/next-generation-aco-model/. Accessed July 22, 2019.

9. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. BPCI Advanced. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bpci-advanced. Accessed July 22, 2019.

10. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Direct Contracting. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/direct-contracting. Accessed July 22, 2019.

11. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/CJR. Accessed July 22, 2019.

1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Shared Savings Program. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-For-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/index.html. Accessed July 22, 2019.

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative: General Information. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments/. Accessed July 22, 2019.

3. Mechanic RE. When new Medicare payment systems collide. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(18):1706-1709. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1601464.

4. Ryan AM, Krinsky S, Adler-Milstein J, Damberg CL, Maurer KA, Hollingsworth JM. Association between hospitals’ engagement in value-based reforms and readmission reduction in the hospital readmission reduction program. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(6):863-868. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0518.

5. Liao JM, Dykstra SE, Werner RM, Navathe AS. BPCI Advanced will further emphasize the need to address overlap between bundled payments and accountable care organizations. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20180409.159181/full/. Accessed May 14, 2019.

6. Census Bureau. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/. Accessed May 14, 2018.

7. van Walraven C, Austin PC, Jennings A, Quan H, Forster AJ. A modification of the elixhauser comorbidity measures into a point system for hospital death using administrative data. Med Care. 2009;47(6):626-633. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819432e5.

8. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Next, Generation ACO Model. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/next-generation-aco-model/. Accessed July 22, 2019.

9. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. BPCI Advanced. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bpci-advanced. Accessed July 22, 2019.

10. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Direct Contracting. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/direct-contracting. Accessed July 22, 2019.

11. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/CJR. Accessed July 22, 2019.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Choosing Wisely in the COVID-19 Era: Preventing Harm to Healthcare Workers

With more than 3 million people diagnosed and more than 200,000 deaths worldwide at the time this article was written, coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) poses an unprecedented challenge to the public and to our healthcare system.1 The United States has surpassed every other country in the total number of COVID-19 cases. Hospitals in hotspots are operating beyond capacity, while others prepare for a predicted surge of patients suffering from COVID-19. Now more than ever, clinicians need to prioritize limited time and resources wisely in this rapidly changing environment. Our most precious limited resource, healthcare workers (HCWs), bravely care for patients while trying to avoid acquiring the infection. With each test and treatment, clinicians must carefully consider harms and benefits, including exposing themselves and other HCWs to SARS-CoV-2, the virus causing this disease.

Delivering any healthcare service in which the potential harm exceeds benefit represents one form of overuse. In the era of COVID-19, the harmful consequences of overuse go beyond the patient to the healthcare team. For example, unnecessary chest computed tomography (CT) to help diagnose COVID-19 comes with the usual risks to the patient including radiation, but it may also reveal a suspicious nodule. That incidental finding can lead to downstream consequences, such as more imaging, blood work, and biopsy. In the current pandemic, however, that CT comes with more than just the usual risk. The initial unnecessary chest CT can risk exposing the transporter, the staff in the hallways and elevator en route, the radiology staff operating the CT scanner, and the maintenance staff who must clean the room and scanner afterward. Potential downstream harms to staff include exposure of the pulmonary and interventional radiology consultants, as well as the staff who perform repeat imaging after the biopsy. Evaluation of the nodule potentially prolongs the patient’s stay and exposes more staff. Clinicians must weigh the benefits and harms of each test and treatment carefully with consideration of both the patient and the staff involved. Moreover, it may turn out that the patient and staff without symptoms of COVID-19 may pose the most risk to one another.

RECOMMENDATIONS

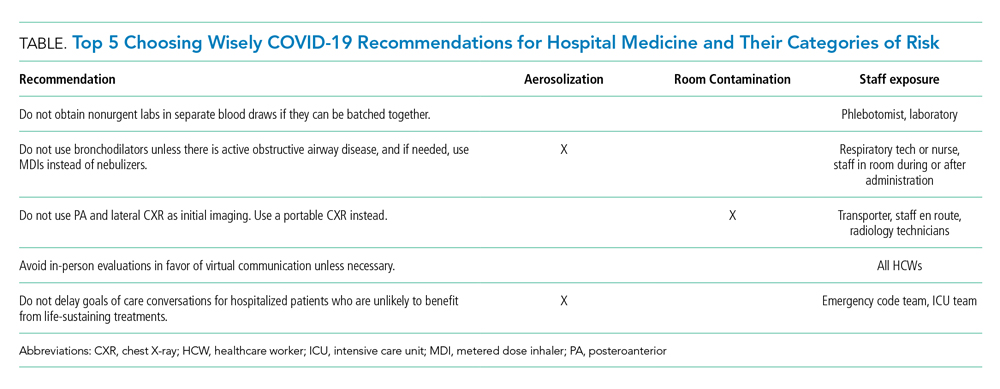

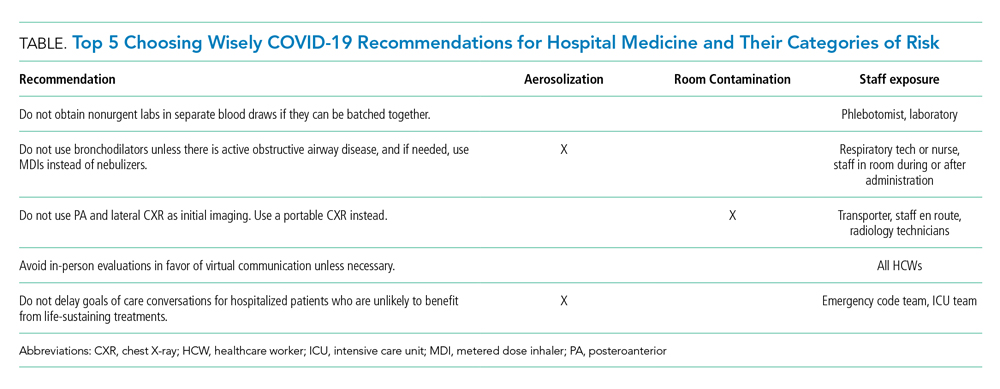

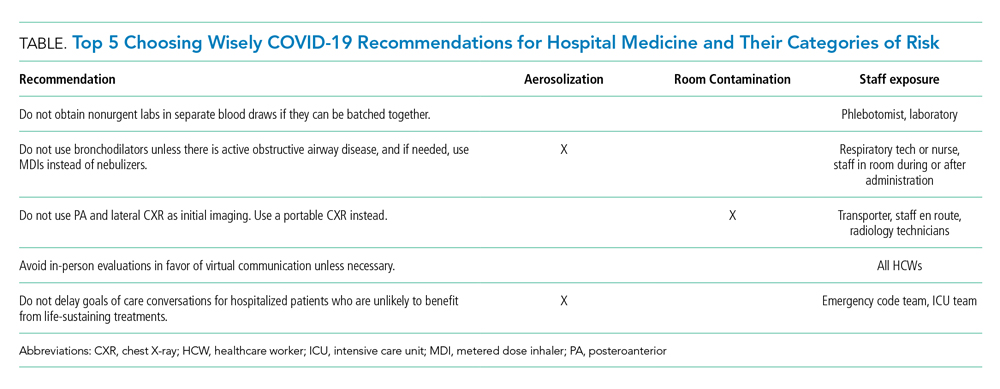

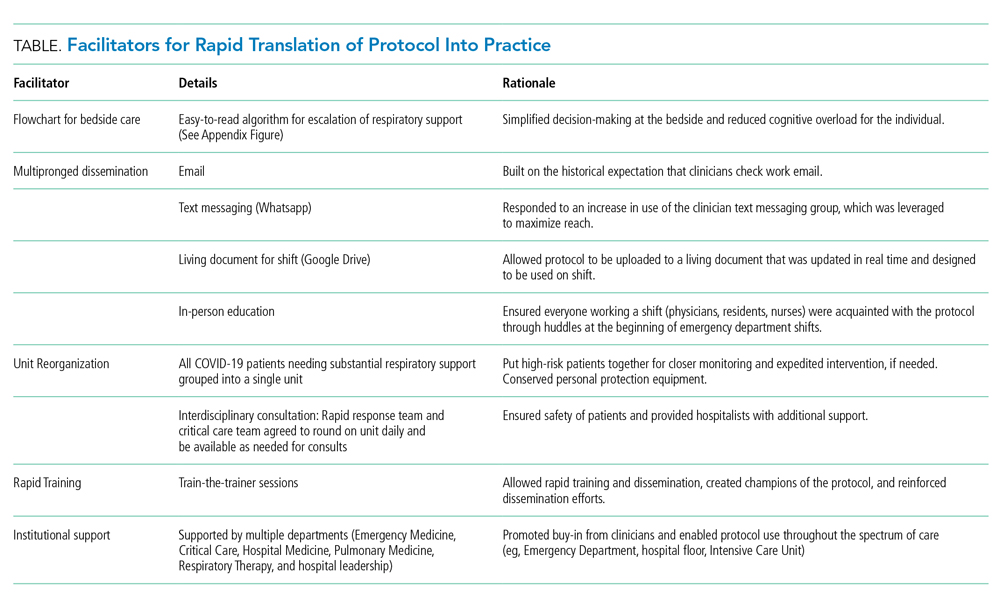

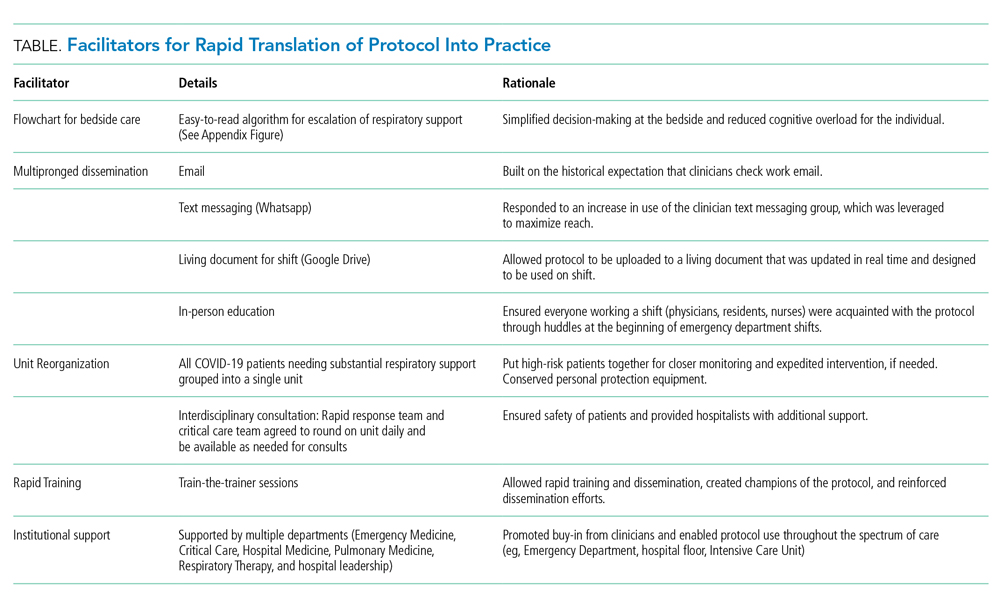

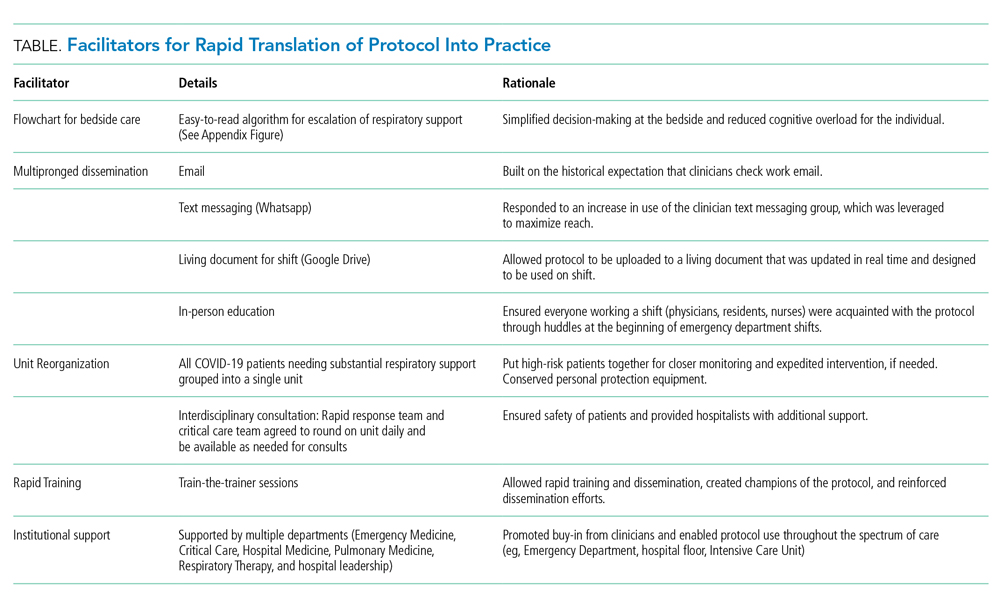

Choosing Wisely® partnered with patients and clinician societies to develop a Top 5 recommendations list for eliminating unnecessary testing and treatment. Our multi-institutional group from the High Value Practice Academic Alliance proposed this Top 5 list of overuse practices in hospital medicine that can lead to harm of both patients and HCWs in the COVID-19 era (Table). The following recommendations apply to all patients with unsuspected, suspected, or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in the hospital setting.

- Do not obtain nonurgent labs in separate blood draws if they can be batched together.

This recommendation expands on the original Society of Hospital Medicine Choosing Wisely recommendation: Don’t perform repetitive complete blood count and chemistry testing in the face of clinical and lab stability.2 Aside from patient harms such as pain and hospital-acquired anemia, the risk of exposure to HCWs who perform phlebotomy (phlebotomists, nurses, and other clinicians), as well as staff who transport, handle, and process the bloodwork in the lab, must be minimized. Most prior interventions to eliminate unnecessary bloodwork focused on the number of lab tests,3 but some also aimed to batch nonurgent labs together to effectively reduce unnecessary needlesticks (“think twice, stick once”).4 This concept can be brought into this pandemic to provide safe and appropriate care for both patients and HCWs.

- Do not use bronchodilators unless there is active obstructive airway disease, and if needed, use metered dose inhalers instead of nebulizers.

We do not recommend using bronchodilators to treat COVID-19 symptoms unless patients develop acute bronchospastic symptoms of their underlying obstructive airway disease.5 When needed, use metered dose inhalers (MDIs),6 if available, instead of nebulizers because the latter potentiates aerosolization that could lead to higher risk of spreading the infection. The risk extends to respiratory technicians and nurses who administer the nebulizer, as well as other HCWs who enter the room during or after administration. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) considers nebulized bronchodilator therapy a “high-risk” exposure for HCWs not wearing the proper personal protectvie equipment.7 Moreover, MDI therapy produces equivalent outcomes to nebulized treatments for patients who are not critically ill.6 Unfortunately, the supply of MDIs during this crisis has not kept up with the increased demand.8

There are no clear guidelines for reuse of MDIs in COVID-19; however, options include labeling patients’ MDIs to use for hospitalization and discharge or labeling an MDI for use during hospitalization and then disinfecting for reuse. For safety reasons, MDIs of COVID-19 patients should be reused only for other patients with COVID-19.8

- Do not use posteroanterior and lateral chest X-ray as initial imaging. Use a portable chest X-ray instead.

The CDC does not currently recommend diagnosing COVID-19 by chest X-ray (CXR).7 When used appropriately, CXR can provide information to support a COVID-19 diagnosis and rule out other etiologies that cause respiratory symptoms.9 Posteroanterior (PA) and lateral CXR are more sensitive than portable CXR for detecting pleural effusions, and lateral CXR is needed to examine structures along the axis of the body. Portable CXR also may cause the heart to appear magnified and the mediastinum widened, the diaphragm to appear higher, and vascular shadows to be obscured.10 The improved ability to detect these subtle differences should be weighed against the increased risk to HCWs required to perform PA and lateral CXR. A portable CXR exposes a relatively smaller number of staff who come to the bedside versus the larger number of people exposed in transporting the patient out of the room and into the hallway, elevator, and the radiology suite for a PA and lateral CXR.

- Avoid in-person evaluations in favor of virtual communication unless necessary.

To minimize HCW exposure to COVID-19 and optimize infection control, the CDC recommends the use of telemedicine when possible.7 Telemedicine refers to the use of technology to support clinical care across some distance, which includes video visits and remote clinical monitoring. At the time of writing, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services had waived the rural site of care requirement for Medicare beneficiaries, granted 49 Medicaid waivers to states to enhance flexibility, and (at least temporarily) added inpatient care to the list of reimbursed telemedicine services.11 Funding for expanded coverage under Medicare is included in the recent Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act.12 These federal changes open the door for commercial payers and state Medicaid programs to further boost telemedicine through reimbursement parity to in-person visits and other coverage policies. Hospitalists can ride this momentum and learn from ambulatory colleagues to harness the power of telemedicine and minimize unnecessary face-to-face interactions with patients who are suspected or confirmed to have COVID-19.13 Even if providers have to enter the patient’s room, telemedicine may still allow for large virtual family meetings despite strict visitor restrictions and physical distance with loved ones. If in-person visits are necessary, only one designated person should enter the patient’s room instead of the entire team.

- Do not delay goals of care conversations for hospitalized patients who are unlikely to benefit from life-sustaining treatments.

The COVID-19 pandemic amplifies the need for early goals of care discussions. Mortality rates range higher with acute respiratory distress syndrome from COVID-19, compared with other etiologies, and is associated with extended intensive care unit stays.14 The harms extend beyond the patient and families to our HCWs through psychological distress and heightened exposure from aerosolization during resuscitation. Advance care planning should center on the values and preferences of the patient. Rather than asking if the patient or family would want certain treatments, it is crucial for clinicians to be direct in making do-not-resuscitate recommendations if deemed futile care.15 This practice is well within legal confines and is distinct from withdrawal or withholding of life-sustaining resources.15

CONCLUSION

HCWs providing inpatient care during this pandemic remain among the highest risk for contracting the infection. As of April 9, 2020, nearly 9,300 HCWs in the United States have contracted COVID-19.16 One thing remains clear: If we want to protect our patients, we must start by protecting our HCWs. We must think critically to evaluate the potential harms to our extended healthcare teams and strive further to eliminate overuse from our care.

Acknowledgment

The authors represent members of the High Value Practice Academic Alliance. The High Value Practice Academic Alliance is a consortium of academic medical centers in the United States and Canada working to advance high-value healthcare through collaborative quality improvement, research, and education. Additional information is available at http://www.hvpaa.org.

1. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019. Accessed May 3, 2020.

2. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2063.

3. Eaton KP, Levy K, Soong C, et al. Evidence-based guidelines to eliminate repetitive laboratory testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1833-1839. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.5152.

4. Wheeler D, Marcus P, Nguyen J, et al. Evaluation of a resident-led project to decrease phlebotomy rates in the hospital: think twice, stick once. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(5):708-710. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0549.

5. Respiratory care committee of Chinese Thoracic Society. [Expert consensus on preventing nosocomial transmission during respiratory care for critically ill patients infected by 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia]. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2020;17(0):E020. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-0939.2020.0020.

6. Moriates C, Feldman L. Nebulized bronchodilators instead of metered-dose inhalers for obstructive pulmonary symptoms. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):691-693. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2386.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim US Guidance for Risk Assessment and Public Health Management of Healthcare Personnel with Potential Exposure in a Healthcare Setting to Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). April 15, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html. Accessed May 3, 2020.

8. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. Revisiting the Need for MDI Common Canister Protocols During the COVID-19 Pandemic. March 26, 2020. https://ismp.org/resources/revisiting-need-mdi-common-canister-protocols-during-covid-19-pandemic. Accessed May 3, 2020.

9. American College of Radiology. ACR Recommendations for the Use of Chest Radiography and Computed Tomography (CT) for Suspected COVID-19 Infection. March 11, 2020. https://www.acr.org/Advocacy-and-Economics/ACR-Position-Statements/Recommendations-for-Chest-Radiography-and-CT-for-Suspected-COVID19-Infection. Accessed May 3, 2020.

10. Bell DJ, Jones J, et al. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/chest-radiograph?lang=us. Accessed April 4, 2020.

11. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. List of Telehealth Services. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-General-Information/Telehealth/Telehealth-Codes. Accessed April 17, 2020.

12. Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2020, HR 6074, 116th Cong (2020). Accessed May 3, 2020. https://congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/6074/.

13. Doshi A, Platt Y, Dressen JR, Mathews Benji, Siy JC. Keep calm and log on: telemedicine for COVID-19 pandemic response. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):302-304. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3419.

14. Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1574‐1581. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5394.

15. Curtis JR, Kross EK, Stapleton RD. The importance of addressing advance care planning and decisions about do-not-resuscitate orders during novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) [online first]. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4894.

16. CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Characteristics of health care personnel with COVID-19 - United States, February 12-April 9, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(15):477-481.

With more than 3 million people diagnosed and more than 200,000 deaths worldwide at the time this article was written, coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) poses an unprecedented challenge to the public and to our healthcare system.1 The United States has surpassed every other country in the total number of COVID-19 cases. Hospitals in hotspots are operating beyond capacity, while others prepare for a predicted surge of patients suffering from COVID-19. Now more than ever, clinicians need to prioritize limited time and resources wisely in this rapidly changing environment. Our most precious limited resource, healthcare workers (HCWs), bravely care for patients while trying to avoid acquiring the infection. With each test and treatment, clinicians must carefully consider harms and benefits, including exposing themselves and other HCWs to SARS-CoV-2, the virus causing this disease.

Delivering any healthcare service in which the potential harm exceeds benefit represents one form of overuse. In the era of COVID-19, the harmful consequences of overuse go beyond the patient to the healthcare team. For example, unnecessary chest computed tomography (CT) to help diagnose COVID-19 comes with the usual risks to the patient including radiation, but it may also reveal a suspicious nodule. That incidental finding can lead to downstream consequences, such as more imaging, blood work, and biopsy. In the current pandemic, however, that CT comes with more than just the usual risk. The initial unnecessary chest CT can risk exposing the transporter, the staff in the hallways and elevator en route, the radiology staff operating the CT scanner, and the maintenance staff who must clean the room and scanner afterward. Potential downstream harms to staff include exposure of the pulmonary and interventional radiology consultants, as well as the staff who perform repeat imaging after the biopsy. Evaluation of the nodule potentially prolongs the patient’s stay and exposes more staff. Clinicians must weigh the benefits and harms of each test and treatment carefully with consideration of both the patient and the staff involved. Moreover, it may turn out that the patient and staff without symptoms of COVID-19 may pose the most risk to one another.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Choosing Wisely® partnered with patients and clinician societies to develop a Top 5 recommendations list for eliminating unnecessary testing and treatment. Our multi-institutional group from the High Value Practice Academic Alliance proposed this Top 5 list of overuse practices in hospital medicine that can lead to harm of both patients and HCWs in the COVID-19 era (Table). The following recommendations apply to all patients with unsuspected, suspected, or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in the hospital setting.

- Do not obtain nonurgent labs in separate blood draws if they can be batched together.

This recommendation expands on the original Society of Hospital Medicine Choosing Wisely recommendation: Don’t perform repetitive complete blood count and chemistry testing in the face of clinical and lab stability.2 Aside from patient harms such as pain and hospital-acquired anemia, the risk of exposure to HCWs who perform phlebotomy (phlebotomists, nurses, and other clinicians), as well as staff who transport, handle, and process the bloodwork in the lab, must be minimized. Most prior interventions to eliminate unnecessary bloodwork focused on the number of lab tests,3 but some also aimed to batch nonurgent labs together to effectively reduce unnecessary needlesticks (“think twice, stick once”).4 This concept can be brought into this pandemic to provide safe and appropriate care for both patients and HCWs.

- Do not use bronchodilators unless there is active obstructive airway disease, and if needed, use metered dose inhalers instead of nebulizers.

We do not recommend using bronchodilators to treat COVID-19 symptoms unless patients develop acute bronchospastic symptoms of their underlying obstructive airway disease.5 When needed, use metered dose inhalers (MDIs),6 if available, instead of nebulizers because the latter potentiates aerosolization that could lead to higher risk of spreading the infection. The risk extends to respiratory technicians and nurses who administer the nebulizer, as well as other HCWs who enter the room during or after administration. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) considers nebulized bronchodilator therapy a “high-risk” exposure for HCWs not wearing the proper personal protectvie equipment.7 Moreover, MDI therapy produces equivalent outcomes to nebulized treatments for patients who are not critically ill.6 Unfortunately, the supply of MDIs during this crisis has not kept up with the increased demand.8

There are no clear guidelines for reuse of MDIs in COVID-19; however, options include labeling patients’ MDIs to use for hospitalization and discharge or labeling an MDI for use during hospitalization and then disinfecting for reuse. For safety reasons, MDIs of COVID-19 patients should be reused only for other patients with COVID-19.8

- Do not use posteroanterior and lateral chest X-ray as initial imaging. Use a portable chest X-ray instead.

The CDC does not currently recommend diagnosing COVID-19 by chest X-ray (CXR).7 When used appropriately, CXR can provide information to support a COVID-19 diagnosis and rule out other etiologies that cause respiratory symptoms.9 Posteroanterior (PA) and lateral CXR are more sensitive than portable CXR for detecting pleural effusions, and lateral CXR is needed to examine structures along the axis of the body. Portable CXR also may cause the heart to appear magnified and the mediastinum widened, the diaphragm to appear higher, and vascular shadows to be obscured.10 The improved ability to detect these subtle differences should be weighed against the increased risk to HCWs required to perform PA and lateral CXR. A portable CXR exposes a relatively smaller number of staff who come to the bedside versus the larger number of people exposed in transporting the patient out of the room and into the hallway, elevator, and the radiology suite for a PA and lateral CXR.

- Avoid in-person evaluations in favor of virtual communication unless necessary.

To minimize HCW exposure to COVID-19 and optimize infection control, the CDC recommends the use of telemedicine when possible.7 Telemedicine refers to the use of technology to support clinical care across some distance, which includes video visits and remote clinical monitoring. At the time of writing, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services had waived the rural site of care requirement for Medicare beneficiaries, granted 49 Medicaid waivers to states to enhance flexibility, and (at least temporarily) added inpatient care to the list of reimbursed telemedicine services.11 Funding for expanded coverage under Medicare is included in the recent Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act.12 These federal changes open the door for commercial payers and state Medicaid programs to further boost telemedicine through reimbursement parity to in-person visits and other coverage policies. Hospitalists can ride this momentum and learn from ambulatory colleagues to harness the power of telemedicine and minimize unnecessary face-to-face interactions with patients who are suspected or confirmed to have COVID-19.13 Even if providers have to enter the patient’s room, telemedicine may still allow for large virtual family meetings despite strict visitor restrictions and physical distance with loved ones. If in-person visits are necessary, only one designated person should enter the patient’s room instead of the entire team.

- Do not delay goals of care conversations for hospitalized patients who are unlikely to benefit from life-sustaining treatments.

The COVID-19 pandemic amplifies the need for early goals of care discussions. Mortality rates range higher with acute respiratory distress syndrome from COVID-19, compared with other etiologies, and is associated with extended intensive care unit stays.14 The harms extend beyond the patient and families to our HCWs through psychological distress and heightened exposure from aerosolization during resuscitation. Advance care planning should center on the values and preferences of the patient. Rather than asking if the patient or family would want certain treatments, it is crucial for clinicians to be direct in making do-not-resuscitate recommendations if deemed futile care.15 This practice is well within legal confines and is distinct from withdrawal or withholding of life-sustaining resources.15

CONCLUSION

HCWs providing inpatient care during this pandemic remain among the highest risk for contracting the infection. As of April 9, 2020, nearly 9,300 HCWs in the United States have contracted COVID-19.16 One thing remains clear: If we want to protect our patients, we must start by protecting our HCWs. We must think critically to evaluate the potential harms to our extended healthcare teams and strive further to eliminate overuse from our care.

Acknowledgment

The authors represent members of the High Value Practice Academic Alliance. The High Value Practice Academic Alliance is a consortium of academic medical centers in the United States and Canada working to advance high-value healthcare through collaborative quality improvement, research, and education. Additional information is available at http://www.hvpaa.org.

With more than 3 million people diagnosed and more than 200,000 deaths worldwide at the time this article was written, coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) poses an unprecedented challenge to the public and to our healthcare system.1 The United States has surpassed every other country in the total number of COVID-19 cases. Hospitals in hotspots are operating beyond capacity, while others prepare for a predicted surge of patients suffering from COVID-19. Now more than ever, clinicians need to prioritize limited time and resources wisely in this rapidly changing environment. Our most precious limited resource, healthcare workers (HCWs), bravely care for patients while trying to avoid acquiring the infection. With each test and treatment, clinicians must carefully consider harms and benefits, including exposing themselves and other HCWs to SARS-CoV-2, the virus causing this disease.

Delivering any healthcare service in which the potential harm exceeds benefit represents one form of overuse. In the era of COVID-19, the harmful consequences of overuse go beyond the patient to the healthcare team. For example, unnecessary chest computed tomography (CT) to help diagnose COVID-19 comes with the usual risks to the patient including radiation, but it may also reveal a suspicious nodule. That incidental finding can lead to downstream consequences, such as more imaging, blood work, and biopsy. In the current pandemic, however, that CT comes with more than just the usual risk. The initial unnecessary chest CT can risk exposing the transporter, the staff in the hallways and elevator en route, the radiology staff operating the CT scanner, and the maintenance staff who must clean the room and scanner afterward. Potential downstream harms to staff include exposure of the pulmonary and interventional radiology consultants, as well as the staff who perform repeat imaging after the biopsy. Evaluation of the nodule potentially prolongs the patient’s stay and exposes more staff. Clinicians must weigh the benefits and harms of each test and treatment carefully with consideration of both the patient and the staff involved. Moreover, it may turn out that the patient and staff without symptoms of COVID-19 may pose the most risk to one another.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Choosing Wisely® partnered with patients and clinician societies to develop a Top 5 recommendations list for eliminating unnecessary testing and treatment. Our multi-institutional group from the High Value Practice Academic Alliance proposed this Top 5 list of overuse practices in hospital medicine that can lead to harm of both patients and HCWs in the COVID-19 era (Table). The following recommendations apply to all patients with unsuspected, suspected, or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in the hospital setting.

- Do not obtain nonurgent labs in separate blood draws if they can be batched together.

This recommendation expands on the original Society of Hospital Medicine Choosing Wisely recommendation: Don’t perform repetitive complete blood count and chemistry testing in the face of clinical and lab stability.2 Aside from patient harms such as pain and hospital-acquired anemia, the risk of exposure to HCWs who perform phlebotomy (phlebotomists, nurses, and other clinicians), as well as staff who transport, handle, and process the bloodwork in the lab, must be minimized. Most prior interventions to eliminate unnecessary bloodwork focused on the number of lab tests,3 but some also aimed to batch nonurgent labs together to effectively reduce unnecessary needlesticks (“think twice, stick once”).4 This concept can be brought into this pandemic to provide safe and appropriate care for both patients and HCWs.

- Do not use bronchodilators unless there is active obstructive airway disease, and if needed, use metered dose inhalers instead of nebulizers.

We do not recommend using bronchodilators to treat COVID-19 symptoms unless patients develop acute bronchospastic symptoms of their underlying obstructive airway disease.5 When needed, use metered dose inhalers (MDIs),6 if available, instead of nebulizers because the latter potentiates aerosolization that could lead to higher risk of spreading the infection. The risk extends to respiratory technicians and nurses who administer the nebulizer, as well as other HCWs who enter the room during or after administration. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) considers nebulized bronchodilator therapy a “high-risk” exposure for HCWs not wearing the proper personal protectvie equipment.7 Moreover, MDI therapy produces equivalent outcomes to nebulized treatments for patients who are not critically ill.6 Unfortunately, the supply of MDIs during this crisis has not kept up with the increased demand.8

There are no clear guidelines for reuse of MDIs in COVID-19; however, options include labeling patients’ MDIs to use for hospitalization and discharge or labeling an MDI for use during hospitalization and then disinfecting for reuse. For safety reasons, MDIs of COVID-19 patients should be reused only for other patients with COVID-19.8

- Do not use posteroanterior and lateral chest X-ray as initial imaging. Use a portable chest X-ray instead.

The CDC does not currently recommend diagnosing COVID-19 by chest X-ray (CXR).7 When used appropriately, CXR can provide information to support a COVID-19 diagnosis and rule out other etiologies that cause respiratory symptoms.9 Posteroanterior (PA) and lateral CXR are more sensitive than portable CXR for detecting pleural effusions, and lateral CXR is needed to examine structures along the axis of the body. Portable CXR also may cause the heart to appear magnified and the mediastinum widened, the diaphragm to appear higher, and vascular shadows to be obscured.10 The improved ability to detect these subtle differences should be weighed against the increased risk to HCWs required to perform PA and lateral CXR. A portable CXR exposes a relatively smaller number of staff who come to the bedside versus the larger number of people exposed in transporting the patient out of the room and into the hallway, elevator, and the radiology suite for a PA and lateral CXR.

- Avoid in-person evaluations in favor of virtual communication unless necessary.

To minimize HCW exposure to COVID-19 and optimize infection control, the CDC recommends the use of telemedicine when possible.7 Telemedicine refers to the use of technology to support clinical care across some distance, which includes video visits and remote clinical monitoring. At the time of writing, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services had waived the rural site of care requirement for Medicare beneficiaries, granted 49 Medicaid waivers to states to enhance flexibility, and (at least temporarily) added inpatient care to the list of reimbursed telemedicine services.11 Funding for expanded coverage under Medicare is included in the recent Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act.12 These federal changes open the door for commercial payers and state Medicaid programs to further boost telemedicine through reimbursement parity to in-person visits and other coverage policies. Hospitalists can ride this momentum and learn from ambulatory colleagues to harness the power of telemedicine and minimize unnecessary face-to-face interactions with patients who are suspected or confirmed to have COVID-19.13 Even if providers have to enter the patient’s room, telemedicine may still allow for large virtual family meetings despite strict visitor restrictions and physical distance with loved ones. If in-person visits are necessary, only one designated person should enter the patient’s room instead of the entire team.

- Do not delay goals of care conversations for hospitalized patients who are unlikely to benefit from life-sustaining treatments.

The COVID-19 pandemic amplifies the need for early goals of care discussions. Mortality rates range higher with acute respiratory distress syndrome from COVID-19, compared with other etiologies, and is associated with extended intensive care unit stays.14 The harms extend beyond the patient and families to our HCWs through psychological distress and heightened exposure from aerosolization during resuscitation. Advance care planning should center on the values and preferences of the patient. Rather than asking if the patient or family would want certain treatments, it is crucial for clinicians to be direct in making do-not-resuscitate recommendations if deemed futile care.15 This practice is well within legal confines and is distinct from withdrawal or withholding of life-sustaining resources.15

CONCLUSION

HCWs providing inpatient care during this pandemic remain among the highest risk for contracting the infection. As of April 9, 2020, nearly 9,300 HCWs in the United States have contracted COVID-19.16 One thing remains clear: If we want to protect our patients, we must start by protecting our HCWs. We must think critically to evaluate the potential harms to our extended healthcare teams and strive further to eliminate overuse from our care.

Acknowledgment

The authors represent members of the High Value Practice Academic Alliance. The High Value Practice Academic Alliance is a consortium of academic medical centers in the United States and Canada working to advance high-value healthcare through collaborative quality improvement, research, and education. Additional information is available at http://www.hvpaa.org.

1. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019. Accessed May 3, 2020.

2. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2063.

3. Eaton KP, Levy K, Soong C, et al. Evidence-based guidelines to eliminate repetitive laboratory testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1833-1839. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.5152.

4. Wheeler D, Marcus P, Nguyen J, et al. Evaluation of a resident-led project to decrease phlebotomy rates in the hospital: think twice, stick once. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(5):708-710. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0549.

5. Respiratory care committee of Chinese Thoracic Society. [Expert consensus on preventing nosocomial transmission during respiratory care for critically ill patients infected by 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia]. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2020;17(0):E020. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-0939.2020.0020.

6. Moriates C, Feldman L. Nebulized bronchodilators instead of metered-dose inhalers for obstructive pulmonary symptoms. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):691-693. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2386.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim US Guidance for Risk Assessment and Public Health Management of Healthcare Personnel with Potential Exposure in a Healthcare Setting to Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). April 15, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html. Accessed May 3, 2020.

8. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. Revisiting the Need for MDI Common Canister Protocols During the COVID-19 Pandemic. March 26, 2020. https://ismp.org/resources/revisiting-need-mdi-common-canister-protocols-during-covid-19-pandemic. Accessed May 3, 2020.

9. American College of Radiology. ACR Recommendations for the Use of Chest Radiography and Computed Tomography (CT) for Suspected COVID-19 Infection. March 11, 2020. https://www.acr.org/Advocacy-and-Economics/ACR-Position-Statements/Recommendations-for-Chest-Radiography-and-CT-for-Suspected-COVID19-Infection. Accessed May 3, 2020.

10. Bell DJ, Jones J, et al. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/chest-radiograph?lang=us. Accessed April 4, 2020.

11. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. List of Telehealth Services. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-General-Information/Telehealth/Telehealth-Codes. Accessed April 17, 2020.

12. Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2020, HR 6074, 116th Cong (2020). Accessed May 3, 2020. https://congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/6074/.

13. Doshi A, Platt Y, Dressen JR, Mathews Benji, Siy JC. Keep calm and log on: telemedicine for COVID-19 pandemic response. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):302-304. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3419.

14. Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1574‐1581. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5394.

15. Curtis JR, Kross EK, Stapleton RD. The importance of addressing advance care planning and decisions about do-not-resuscitate orders during novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) [online first]. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4894.

16. CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Characteristics of health care personnel with COVID-19 - United States, February 12-April 9, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(15):477-481.

1. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019. Accessed May 3, 2020.

2. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2063.

3. Eaton KP, Levy K, Soong C, et al. Evidence-based guidelines to eliminate repetitive laboratory testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1833-1839. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.5152.

4. Wheeler D, Marcus P, Nguyen J, et al. Evaluation of a resident-led project to decrease phlebotomy rates in the hospital: think twice, stick once. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(5):708-710. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0549.

5. Respiratory care committee of Chinese Thoracic Society. [Expert consensus on preventing nosocomial transmission during respiratory care for critically ill patients infected by 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia]. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2020;17(0):E020. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-0939.2020.0020.

6. Moriates C, Feldman L. Nebulized bronchodilators instead of metered-dose inhalers for obstructive pulmonary symptoms. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):691-693. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2386.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim US Guidance for Risk Assessment and Public Health Management of Healthcare Personnel with Potential Exposure in a Healthcare Setting to Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). April 15, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html. Accessed May 3, 2020.

8. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. Revisiting the Need for MDI Common Canister Protocols During the COVID-19 Pandemic. March 26, 2020. https://ismp.org/resources/revisiting-need-mdi-common-canister-protocols-during-covid-19-pandemic. Accessed May 3, 2020.

9. American College of Radiology. ACR Recommendations for the Use of Chest Radiography and Computed Tomography (CT) for Suspected COVID-19 Infection. March 11, 2020. https://www.acr.org/Advocacy-and-Economics/ACR-Position-Statements/Recommendations-for-Chest-Radiography-and-CT-for-Suspected-COVID19-Infection. Accessed May 3, 2020.

10. Bell DJ, Jones J, et al. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/chest-radiograph?lang=us. Accessed April 4, 2020.

11. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. List of Telehealth Services. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-General-Information/Telehealth/Telehealth-Codes. Accessed April 17, 2020.

12. Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2020, HR 6074, 116th Cong (2020). Accessed May 3, 2020. https://congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/6074/.

13. Doshi A, Platt Y, Dressen JR, Mathews Benji, Siy JC. Keep calm and log on: telemedicine for COVID-19 pandemic response. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):302-304. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3419.

14. Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1574‐1581. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5394.

15. Curtis JR, Kross EK, Stapleton RD. The importance of addressing advance care planning and decisions about do-not-resuscitate orders during novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) [online first]. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4894.

16. CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Characteristics of health care personnel with COVID-19 - United States, February 12-April 9, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(15):477-481.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Reducing the Risk of Diagnostic Error in the COVID-19 Era