User login

Perceived safety and value of inpatient “very important person” services

Recent publications in the medical literature and lay press have stirred controversy regarding the use of inpatient ‘very important person’ (VIP) services.1-3 The term “VIP services” often refers to select conveniences offered in addition to the assumed basic level of care and services provided by a hospital. Examples include additional space, enhanced facilities, specific comforts, or personal support. In some instances, these amenities may only be provided to patients who have close financial, social, or professional relationships with the hospital.

How VIP patients interact with their health system to obtain VIP services has raised unique concerns. Some have speculated that the presence of a VIP patient may be disruptive to the care of non-VIP patients, while others have cautioned physicians about potential dangers to the VIP patients themselves.4-6 Despite much being written on the topics of VIP patients and services in both the lay and academic press, our literature review identified only 1 study on the topic, which cataloged the preferential treatment of VIP patients in the emergency department.6 We are unaware of any investigations of VIP-service use in the inpatient setting. Through a multisite survey of hospital medicine physicians, we assessed physician viewpoints and behavior regarding VIP services.

METHODS

The Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN) is a nation-wide learning organization focused on measuring and improving the outcomes of hospitalized patients.7 We surveyed hospitalists from 8 HOMERuN hospitals (Appendix 1). The survey instrument contained 4 sections: nonidentifying respondent demographics, local use of VIP services, reported physician perceptions of VIP services, and case-based assessments (Appendix 2). Survey questions and individual cases were developed by study authors and based on real scenarios and concerns provided by front-line clinical providers. Content, length, and reliability of physician understanding were assessed by a 5-person focus group consisting of physicians not included in the survey population.

Subjects were identified via administrative rosters from each HOMERuN site. Surveys were administered via SurveyMonkey, and results were analyzed descriptively. Populations were compared via the Fisher exact test. “VIP services” were defined as conveniences provided in addition to the assumed basic level of care and services (eg, private or luxury-style rooms, access to a special menu, better views, dedicated personal care attendants, hospital liaisons). VIP patients were defined as those patients receiving VIP services. A hospital was identified as providing VIP services if 50% or more of respondents from that site reported the presence of VIP services.

RESULTS

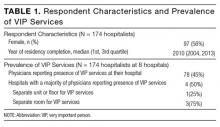

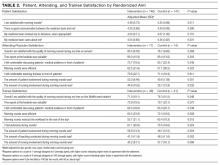

Of 366 hospitalists contacted, 160 completed the survey (44%). Respondent characteristics and reported prevalence of VIP services are demonstrated in Table 1. In total, 78 respondents (45%) reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital. Of the 8 sites surveyed, a majority of physicians at 4 sites (50%) reported presence of VIP services.

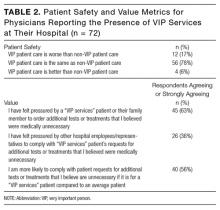

Of respondents reporting the presence of VIP services at their hospital, a majority felt that, from a patient safety perspective, the care received by VIP patients was the same as care received by non-VIP patients (Table 2). A majority reported they had felt pressured by a VIP patient or a family member to order additional tests or treatments that the physician believed were medically unnecessary and that they would be more likely to comply with VIP patient’s requests for tests or treatments they felt were unnecessary. More than one-third (36%) felt pressured by other hospital employees or representatives to comply with VIP services patient’s requests for additional tests or treatments that the physicians believed were medically unnecessary.

When presented the case of a VIP patient with community-acquired pneumonia who is clinically stable for discharge but expressing concerns about leaving the hospital, 61 (38%) respondents reported they would not discharge this patient home: 39 of 70 (55.7%) who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital, and 22 of 91 (24.2%) who reported the absence of VIP services (P < 0.001). Of those who reported they would not discharge this patient home, 37 (61%) reported the reason for this related to the patient’s connection to the Board of Trustees; 48 (79%) reported the reason for this related to the patient’s concerns; 9 (15%) reported the reason for this related to their own concerns regarding medical details of the patient’s case (respondents could select more than 1 reason).

When presented the case of a VIP patient with acute pulmonary embolism who is medically ready for discharge with primary care physician-approved anticoagulation and discharge plans but for whom their family requests additional consultations and inpatient hypercoagulable workup, 33 (21%) respondents reported they would order additional testing and specialist consultation: 17 of 69 (24.6%) who reported the presence of VIP services their hospital, and 16 of 91 (17.6%) who reported the absence of VIP services (P = 0.33). Of those who reported they would order additional testing and specialist consultation, 14 (42%) reported the reason for this related to the family’s financial connections to the hospital; 30 (91%) reported the reason for this related to the family’s concerns; 3 (9%) reported the reason for this related to their own concerns about the medical details of the patient’s case (respondents could select more than 1 reason).

DISCUSSION

In our study, a majority of physicians who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital felt pressured by VIP patients or their family members to perform unnecessary testing or treatment. While this study was not designed to quantify the burden of unnecessary care for VIP patients, our results have implications for individual patients and public health, including potential effects on resource availability, the identification of clinically irrelevant incidental findings, and short- and long-term medical complications of procedures, testing and radiation exposure.

Prior publications have advocated that physicians and hospitals should not allow VIP status to influence management decisions.3,5 We found that more than one-third of physicians who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital also reported receiving pressure from hospital representatives to provide care to VIP patients that was not medically indicated. These findings highlight an example of the tension faced by physicians who are caught between patient requests and the delivery of value-based care. This potential conflict may be amplified particularly for those patients with close financial, social, or professional ties to the hospitals (and physicians) providing their care. These results suggest the need for physicians, administrators, and patients to work together to address the potential blurring of ethical boundaries created by VIP relationships. Prevention of harm and avoidance of placing physicians in morally distressing situations are common goals for all involved parties.

Efforts to reduce unnecessary care have predominantly focused on structural and knowledge-based drivers.4,8,9 Our results highlight the presence of additional forces. A majority of physician respondents who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital also reported that they would be more likely to comply with requests for unnecessary care for a VIP patient as compared to a non-VIP patient. Furthermore, in case-based questions about the requests of a VIP patient and their family for additional unnecessary care, a significant portion of physicians who reported they would comply with these requests listed the VIP status of the patient or family as a factor underlying this decision. Only a minority of physicians reported their decision to provide additional care was the result of their own medically-based concerns. Because these cases were hypothetical and we did not include comparator cases involving non-VIP patients, it remains uncertain whether the observed perceptions accurately reflect real-world differences in the care of VIP and non-VIP patients. Nonetheless, our findings emphasize the importance of better understanding the social drivers of overuse and physician communication strategies related to medically inappropriate tests.10,11

Demand for unnecessary testing may be driven by the mentality that “more is better.”12 Contrary to this belief, provision of unnecessary care can increase the risk of patient harm.13 Despite physician respondents reporting that VIP patients requested and/or received additional unnecessary care, a majority of respondents felt that patient safety for VIP patients was equivalent to that for non-VIP patients. As we assessed only physician perceptions of safety, which may not necessarily correlate with actual safety, further research in this area is needed.

Our study was limited by several factors. While our study population included hospitalists from 8 geographically broad hospitals, including university, safety net, and community hospitals, study responses may not be reflective of nationwide trends. Our response rate may limit our ability to generalize conclusions beyond respondents. Second, our study captured physician perceptions of behavior and safety rather than actually measuring practice and outcomes. Studies comparing physician practice patterns and outcomes between VIP and non-VIP patients would be informative. Additionally, despite our inclusive survey design process, our survey was not validated, and it is possible that our questions were not interpreted as intended. Lastly, despite the anonymous nature of our survey, physicians may have felt compelled to respond in a particular way due to conflicting professional, financial, or social factors.

Our findings provide initial insight into how care for the VIP patient may present unique challenges for physicians, hospitals, and society by systematizing care inequities, as well as potentially incentivizing low-value care practices. Whether these imbalances produce clinical harms or benefits remains worthy of future studies.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Bernstein N. Chefs, butlers, marble baths: Hospitals vie for the affluent. New York Times. January 21, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/22/nyregion/chefs-butlers-and-marble-baths-not-your-average-hospital-room.html. Accessed February 1, 2017.

2. Kennedy DW, Kagan SH, Abramson KB, Boberick C, Kaiser LR. Academic medicine amenities unit: developing a model to integrate academic medical care with luxury hotel services. Acad Med. 2009;84(2):185-191. PubMed

3. Alfandre D, Clever S, Farber NJ, Hughes MT, Redstone P, Lehmann LS. Caring for ‘very important patients’--ethical dilemmas and suggestions for practical management. Am J Med. 2016;129(2):143-147. PubMed

4. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. PubMed

5. Martin A, Bostic JQ, Pruett K. The V.I.P.: hazard and promise in treating “special” patients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(3):366-369. PubMed

6. Smally AJ, Carroll B, Carius M, Tilden F, Werdmann M. Treatment of VIPs. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(4):397-398. PubMed

7. Auerbach AD, Patel MS, Metlay JP, et al. The hospital medicine reengineering network (HOMERuN): a learning organization focused on improving hospital care. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):415-420. PubMed

8. Caverly TJ, Combs BP, Moriates C, Shah N, Grady D. Too much medicine happens too often: the teachable moment and a call for manuscripts from clinical trainees. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(1):8-9. PubMed

9. Schwartz AL, Chernew ME, Landon BE, McWilliams JM. Changes in low-value services in year 1 of the Medicare pioneer accountable care organization program. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(11):1815-1825. PubMed

10. Paterniti DA, Fancher TL, Cipri CS, Timmermans S, Heritage J, Kravitz RL. Getting to “no”: strategies primary care physicians use to deny patient requests. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):381-388. PubMed

11. Veroff D, Marr A, Wennberg DE. Enhanced support for shared decision making reduced costs of care for patients with preference-sensitive conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(2):285-293. PubMed

12. Korenstein D. Patient perception of benefits and harms: the Achilles heel of high-value care. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):287-288. PubMed

13. Moynihan R, Doust J, Henry D. Preventing overdiagnosis: how to stop harming the healthy. BMJ. 2012;344:e3502. PubMed

Recent publications in the medical literature and lay press have stirred controversy regarding the use of inpatient ‘very important person’ (VIP) services.1-3 The term “VIP services” often refers to select conveniences offered in addition to the assumed basic level of care and services provided by a hospital. Examples include additional space, enhanced facilities, specific comforts, or personal support. In some instances, these amenities may only be provided to patients who have close financial, social, or professional relationships with the hospital.

How VIP patients interact with their health system to obtain VIP services has raised unique concerns. Some have speculated that the presence of a VIP patient may be disruptive to the care of non-VIP patients, while others have cautioned physicians about potential dangers to the VIP patients themselves.4-6 Despite much being written on the topics of VIP patients and services in both the lay and academic press, our literature review identified only 1 study on the topic, which cataloged the preferential treatment of VIP patients in the emergency department.6 We are unaware of any investigations of VIP-service use in the inpatient setting. Through a multisite survey of hospital medicine physicians, we assessed physician viewpoints and behavior regarding VIP services.

METHODS

The Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN) is a nation-wide learning organization focused on measuring and improving the outcomes of hospitalized patients.7 We surveyed hospitalists from 8 HOMERuN hospitals (Appendix 1). The survey instrument contained 4 sections: nonidentifying respondent demographics, local use of VIP services, reported physician perceptions of VIP services, and case-based assessments (Appendix 2). Survey questions and individual cases were developed by study authors and based on real scenarios and concerns provided by front-line clinical providers. Content, length, and reliability of physician understanding were assessed by a 5-person focus group consisting of physicians not included in the survey population.

Subjects were identified via administrative rosters from each HOMERuN site. Surveys were administered via SurveyMonkey, and results were analyzed descriptively. Populations were compared via the Fisher exact test. “VIP services” were defined as conveniences provided in addition to the assumed basic level of care and services (eg, private or luxury-style rooms, access to a special menu, better views, dedicated personal care attendants, hospital liaisons). VIP patients were defined as those patients receiving VIP services. A hospital was identified as providing VIP services if 50% or more of respondents from that site reported the presence of VIP services.

RESULTS

Of 366 hospitalists contacted, 160 completed the survey (44%). Respondent characteristics and reported prevalence of VIP services are demonstrated in Table 1. In total, 78 respondents (45%) reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital. Of the 8 sites surveyed, a majority of physicians at 4 sites (50%) reported presence of VIP services.

Of respondents reporting the presence of VIP services at their hospital, a majority felt that, from a patient safety perspective, the care received by VIP patients was the same as care received by non-VIP patients (Table 2). A majority reported they had felt pressured by a VIP patient or a family member to order additional tests or treatments that the physician believed were medically unnecessary and that they would be more likely to comply with VIP patient’s requests for tests or treatments they felt were unnecessary. More than one-third (36%) felt pressured by other hospital employees or representatives to comply with VIP services patient’s requests for additional tests or treatments that the physicians believed were medically unnecessary.

When presented the case of a VIP patient with community-acquired pneumonia who is clinically stable for discharge but expressing concerns about leaving the hospital, 61 (38%) respondents reported they would not discharge this patient home: 39 of 70 (55.7%) who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital, and 22 of 91 (24.2%) who reported the absence of VIP services (P < 0.001). Of those who reported they would not discharge this patient home, 37 (61%) reported the reason for this related to the patient’s connection to the Board of Trustees; 48 (79%) reported the reason for this related to the patient’s concerns; 9 (15%) reported the reason for this related to their own concerns regarding medical details of the patient’s case (respondents could select more than 1 reason).

When presented the case of a VIP patient with acute pulmonary embolism who is medically ready for discharge with primary care physician-approved anticoagulation and discharge plans but for whom their family requests additional consultations and inpatient hypercoagulable workup, 33 (21%) respondents reported they would order additional testing and specialist consultation: 17 of 69 (24.6%) who reported the presence of VIP services their hospital, and 16 of 91 (17.6%) who reported the absence of VIP services (P = 0.33). Of those who reported they would order additional testing and specialist consultation, 14 (42%) reported the reason for this related to the family’s financial connections to the hospital; 30 (91%) reported the reason for this related to the family’s concerns; 3 (9%) reported the reason for this related to their own concerns about the medical details of the patient’s case (respondents could select more than 1 reason).

DISCUSSION

In our study, a majority of physicians who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital felt pressured by VIP patients or their family members to perform unnecessary testing or treatment. While this study was not designed to quantify the burden of unnecessary care for VIP patients, our results have implications for individual patients and public health, including potential effects on resource availability, the identification of clinically irrelevant incidental findings, and short- and long-term medical complications of procedures, testing and radiation exposure.

Prior publications have advocated that physicians and hospitals should not allow VIP status to influence management decisions.3,5 We found that more than one-third of physicians who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital also reported receiving pressure from hospital representatives to provide care to VIP patients that was not medically indicated. These findings highlight an example of the tension faced by physicians who are caught between patient requests and the delivery of value-based care. This potential conflict may be amplified particularly for those patients with close financial, social, or professional ties to the hospitals (and physicians) providing their care. These results suggest the need for physicians, administrators, and patients to work together to address the potential blurring of ethical boundaries created by VIP relationships. Prevention of harm and avoidance of placing physicians in morally distressing situations are common goals for all involved parties.

Efforts to reduce unnecessary care have predominantly focused on structural and knowledge-based drivers.4,8,9 Our results highlight the presence of additional forces. A majority of physician respondents who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital also reported that they would be more likely to comply with requests for unnecessary care for a VIP patient as compared to a non-VIP patient. Furthermore, in case-based questions about the requests of a VIP patient and their family for additional unnecessary care, a significant portion of physicians who reported they would comply with these requests listed the VIP status of the patient or family as a factor underlying this decision. Only a minority of physicians reported their decision to provide additional care was the result of their own medically-based concerns. Because these cases were hypothetical and we did not include comparator cases involving non-VIP patients, it remains uncertain whether the observed perceptions accurately reflect real-world differences in the care of VIP and non-VIP patients. Nonetheless, our findings emphasize the importance of better understanding the social drivers of overuse and physician communication strategies related to medically inappropriate tests.10,11

Demand for unnecessary testing may be driven by the mentality that “more is better.”12 Contrary to this belief, provision of unnecessary care can increase the risk of patient harm.13 Despite physician respondents reporting that VIP patients requested and/or received additional unnecessary care, a majority of respondents felt that patient safety for VIP patients was equivalent to that for non-VIP patients. As we assessed only physician perceptions of safety, which may not necessarily correlate with actual safety, further research in this area is needed.

Our study was limited by several factors. While our study population included hospitalists from 8 geographically broad hospitals, including university, safety net, and community hospitals, study responses may not be reflective of nationwide trends. Our response rate may limit our ability to generalize conclusions beyond respondents. Second, our study captured physician perceptions of behavior and safety rather than actually measuring practice and outcomes. Studies comparing physician practice patterns and outcomes between VIP and non-VIP patients would be informative. Additionally, despite our inclusive survey design process, our survey was not validated, and it is possible that our questions were not interpreted as intended. Lastly, despite the anonymous nature of our survey, physicians may have felt compelled to respond in a particular way due to conflicting professional, financial, or social factors.

Our findings provide initial insight into how care for the VIP patient may present unique challenges for physicians, hospitals, and society by systematizing care inequities, as well as potentially incentivizing low-value care practices. Whether these imbalances produce clinical harms or benefits remains worthy of future studies.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Recent publications in the medical literature and lay press have stirred controversy regarding the use of inpatient ‘very important person’ (VIP) services.1-3 The term “VIP services” often refers to select conveniences offered in addition to the assumed basic level of care and services provided by a hospital. Examples include additional space, enhanced facilities, specific comforts, or personal support. In some instances, these amenities may only be provided to patients who have close financial, social, or professional relationships with the hospital.

How VIP patients interact with their health system to obtain VIP services has raised unique concerns. Some have speculated that the presence of a VIP patient may be disruptive to the care of non-VIP patients, while others have cautioned physicians about potential dangers to the VIP patients themselves.4-6 Despite much being written on the topics of VIP patients and services in both the lay and academic press, our literature review identified only 1 study on the topic, which cataloged the preferential treatment of VIP patients in the emergency department.6 We are unaware of any investigations of VIP-service use in the inpatient setting. Through a multisite survey of hospital medicine physicians, we assessed physician viewpoints and behavior regarding VIP services.

METHODS

The Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN) is a nation-wide learning organization focused on measuring and improving the outcomes of hospitalized patients.7 We surveyed hospitalists from 8 HOMERuN hospitals (Appendix 1). The survey instrument contained 4 sections: nonidentifying respondent demographics, local use of VIP services, reported physician perceptions of VIP services, and case-based assessments (Appendix 2). Survey questions and individual cases were developed by study authors and based on real scenarios and concerns provided by front-line clinical providers. Content, length, and reliability of physician understanding were assessed by a 5-person focus group consisting of physicians not included in the survey population.

Subjects were identified via administrative rosters from each HOMERuN site. Surveys were administered via SurveyMonkey, and results were analyzed descriptively. Populations were compared via the Fisher exact test. “VIP services” were defined as conveniences provided in addition to the assumed basic level of care and services (eg, private or luxury-style rooms, access to a special menu, better views, dedicated personal care attendants, hospital liaisons). VIP patients were defined as those patients receiving VIP services. A hospital was identified as providing VIP services if 50% or more of respondents from that site reported the presence of VIP services.

RESULTS

Of 366 hospitalists contacted, 160 completed the survey (44%). Respondent characteristics and reported prevalence of VIP services are demonstrated in Table 1. In total, 78 respondents (45%) reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital. Of the 8 sites surveyed, a majority of physicians at 4 sites (50%) reported presence of VIP services.

Of respondents reporting the presence of VIP services at their hospital, a majority felt that, from a patient safety perspective, the care received by VIP patients was the same as care received by non-VIP patients (Table 2). A majority reported they had felt pressured by a VIP patient or a family member to order additional tests or treatments that the physician believed were medically unnecessary and that they would be more likely to comply with VIP patient’s requests for tests or treatments they felt were unnecessary. More than one-third (36%) felt pressured by other hospital employees or representatives to comply with VIP services patient’s requests for additional tests or treatments that the physicians believed were medically unnecessary.

When presented the case of a VIP patient with community-acquired pneumonia who is clinically stable for discharge but expressing concerns about leaving the hospital, 61 (38%) respondents reported they would not discharge this patient home: 39 of 70 (55.7%) who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital, and 22 of 91 (24.2%) who reported the absence of VIP services (P < 0.001). Of those who reported they would not discharge this patient home, 37 (61%) reported the reason for this related to the patient’s connection to the Board of Trustees; 48 (79%) reported the reason for this related to the patient’s concerns; 9 (15%) reported the reason for this related to their own concerns regarding medical details of the patient’s case (respondents could select more than 1 reason).

When presented the case of a VIP patient with acute pulmonary embolism who is medically ready for discharge with primary care physician-approved anticoagulation and discharge plans but for whom their family requests additional consultations and inpatient hypercoagulable workup, 33 (21%) respondents reported they would order additional testing and specialist consultation: 17 of 69 (24.6%) who reported the presence of VIP services their hospital, and 16 of 91 (17.6%) who reported the absence of VIP services (P = 0.33). Of those who reported they would order additional testing and specialist consultation, 14 (42%) reported the reason for this related to the family’s financial connections to the hospital; 30 (91%) reported the reason for this related to the family’s concerns; 3 (9%) reported the reason for this related to their own concerns about the medical details of the patient’s case (respondents could select more than 1 reason).

DISCUSSION

In our study, a majority of physicians who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital felt pressured by VIP patients or their family members to perform unnecessary testing or treatment. While this study was not designed to quantify the burden of unnecessary care for VIP patients, our results have implications for individual patients and public health, including potential effects on resource availability, the identification of clinically irrelevant incidental findings, and short- and long-term medical complications of procedures, testing and radiation exposure.

Prior publications have advocated that physicians and hospitals should not allow VIP status to influence management decisions.3,5 We found that more than one-third of physicians who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital also reported receiving pressure from hospital representatives to provide care to VIP patients that was not medically indicated. These findings highlight an example of the tension faced by physicians who are caught between patient requests and the delivery of value-based care. This potential conflict may be amplified particularly for those patients with close financial, social, or professional ties to the hospitals (and physicians) providing their care. These results suggest the need for physicians, administrators, and patients to work together to address the potential blurring of ethical boundaries created by VIP relationships. Prevention of harm and avoidance of placing physicians in morally distressing situations are common goals for all involved parties.

Efforts to reduce unnecessary care have predominantly focused on structural and knowledge-based drivers.4,8,9 Our results highlight the presence of additional forces. A majority of physician respondents who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital also reported that they would be more likely to comply with requests for unnecessary care for a VIP patient as compared to a non-VIP patient. Furthermore, in case-based questions about the requests of a VIP patient and their family for additional unnecessary care, a significant portion of physicians who reported they would comply with these requests listed the VIP status of the patient or family as a factor underlying this decision. Only a minority of physicians reported their decision to provide additional care was the result of their own medically-based concerns. Because these cases were hypothetical and we did not include comparator cases involving non-VIP patients, it remains uncertain whether the observed perceptions accurately reflect real-world differences in the care of VIP and non-VIP patients. Nonetheless, our findings emphasize the importance of better understanding the social drivers of overuse and physician communication strategies related to medically inappropriate tests.10,11

Demand for unnecessary testing may be driven by the mentality that “more is better.”12 Contrary to this belief, provision of unnecessary care can increase the risk of patient harm.13 Despite physician respondents reporting that VIP patients requested and/or received additional unnecessary care, a majority of respondents felt that patient safety for VIP patients was equivalent to that for non-VIP patients. As we assessed only physician perceptions of safety, which may not necessarily correlate with actual safety, further research in this area is needed.

Our study was limited by several factors. While our study population included hospitalists from 8 geographically broad hospitals, including university, safety net, and community hospitals, study responses may not be reflective of nationwide trends. Our response rate may limit our ability to generalize conclusions beyond respondents. Second, our study captured physician perceptions of behavior and safety rather than actually measuring practice and outcomes. Studies comparing physician practice patterns and outcomes between VIP and non-VIP patients would be informative. Additionally, despite our inclusive survey design process, our survey was not validated, and it is possible that our questions were not interpreted as intended. Lastly, despite the anonymous nature of our survey, physicians may have felt compelled to respond in a particular way due to conflicting professional, financial, or social factors.

Our findings provide initial insight into how care for the VIP patient may present unique challenges for physicians, hospitals, and society by systematizing care inequities, as well as potentially incentivizing low-value care practices. Whether these imbalances produce clinical harms or benefits remains worthy of future studies.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Bernstein N. Chefs, butlers, marble baths: Hospitals vie for the affluent. New York Times. January 21, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/22/nyregion/chefs-butlers-and-marble-baths-not-your-average-hospital-room.html. Accessed February 1, 2017.

2. Kennedy DW, Kagan SH, Abramson KB, Boberick C, Kaiser LR. Academic medicine amenities unit: developing a model to integrate academic medical care with luxury hotel services. Acad Med. 2009;84(2):185-191. PubMed

3. Alfandre D, Clever S, Farber NJ, Hughes MT, Redstone P, Lehmann LS. Caring for ‘very important patients’--ethical dilemmas and suggestions for practical management. Am J Med. 2016;129(2):143-147. PubMed

4. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. PubMed

5. Martin A, Bostic JQ, Pruett K. The V.I.P.: hazard and promise in treating “special” patients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(3):366-369. PubMed

6. Smally AJ, Carroll B, Carius M, Tilden F, Werdmann M. Treatment of VIPs. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(4):397-398. PubMed

7. Auerbach AD, Patel MS, Metlay JP, et al. The hospital medicine reengineering network (HOMERuN): a learning organization focused on improving hospital care. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):415-420. PubMed

8. Caverly TJ, Combs BP, Moriates C, Shah N, Grady D. Too much medicine happens too often: the teachable moment and a call for manuscripts from clinical trainees. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(1):8-9. PubMed

9. Schwartz AL, Chernew ME, Landon BE, McWilliams JM. Changes in low-value services in year 1 of the Medicare pioneer accountable care organization program. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(11):1815-1825. PubMed

10. Paterniti DA, Fancher TL, Cipri CS, Timmermans S, Heritage J, Kravitz RL. Getting to “no”: strategies primary care physicians use to deny patient requests. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):381-388. PubMed

11. Veroff D, Marr A, Wennberg DE. Enhanced support for shared decision making reduced costs of care for patients with preference-sensitive conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(2):285-293. PubMed

12. Korenstein D. Patient perception of benefits and harms: the Achilles heel of high-value care. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):287-288. PubMed

13. Moynihan R, Doust J, Henry D. Preventing overdiagnosis: how to stop harming the healthy. BMJ. 2012;344:e3502. PubMed

1. Bernstein N. Chefs, butlers, marble baths: Hospitals vie for the affluent. New York Times. January 21, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/22/nyregion/chefs-butlers-and-marble-baths-not-your-average-hospital-room.html. Accessed February 1, 2017.

2. Kennedy DW, Kagan SH, Abramson KB, Boberick C, Kaiser LR. Academic medicine amenities unit: developing a model to integrate academic medical care with luxury hotel services. Acad Med. 2009;84(2):185-191. PubMed

3. Alfandre D, Clever S, Farber NJ, Hughes MT, Redstone P, Lehmann LS. Caring for ‘very important patients’--ethical dilemmas and suggestions for practical management. Am J Med. 2016;129(2):143-147. PubMed

4. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. PubMed

5. Martin A, Bostic JQ, Pruett K. The V.I.P.: hazard and promise in treating “special” patients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(3):366-369. PubMed

6. Smally AJ, Carroll B, Carius M, Tilden F, Werdmann M. Treatment of VIPs. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(4):397-398. PubMed

7. Auerbach AD, Patel MS, Metlay JP, et al. The hospital medicine reengineering network (HOMERuN): a learning organization focused on improving hospital care. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):415-420. PubMed

8. Caverly TJ, Combs BP, Moriates C, Shah N, Grady D. Too much medicine happens too often: the teachable moment and a call for manuscripts from clinical trainees. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(1):8-9. PubMed

9. Schwartz AL, Chernew ME, Landon BE, McWilliams JM. Changes in low-value services in year 1 of the Medicare pioneer accountable care organization program. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(11):1815-1825. PubMed

10. Paterniti DA, Fancher TL, Cipri CS, Timmermans S, Heritage J, Kravitz RL. Getting to “no”: strategies primary care physicians use to deny patient requests. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):381-388. PubMed

11. Veroff D, Marr A, Wennberg DE. Enhanced support for shared decision making reduced costs of care for patients with preference-sensitive conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(2):285-293. PubMed

12. Korenstein D. Patient perception of benefits and harms: the Achilles heel of high-value care. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):287-288. PubMed

13. Moynihan R, Doust J, Henry D. Preventing overdiagnosis: how to stop harming the healthy. BMJ. 2012;344:e3502. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

A time and motion study of pharmacists and pharmacy technicians obtaining admission medication histories

Using pharmacists to obtain admission medication histories (AMHs) reduces medication errors by 70% to 83% and resultant adverse drug events (ADEs) by 15%.1-3 Dissemination of this practice has been limited by several factors, including clinician practice models, staff availability, confusion in provider roles and accountability, and absence of standardized best practices.4-5 This paper assesses one of these barriers: the high cost of utilizing pharmacists. Third-person observer time and motion analysis shows that pharmacists require 46 and 92 minutes to obtain AMHs from medical and geriatric patients,6 respectively, resulting in pharmacist costs of $44 to $88 per patient, based on 2015 US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) hourly wage data for pharmacists ($57.34).7

Ph

METHODS

This study originated as part of a randomized, controlled trial conducted during January-February 2014 at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center (CSMC), an 896-bed, university-affiliated, not-for-profit hospital.9 Pharmacy staff included pharmacists, PGY-1 pharmacy residents, and pharmacy technicians, each of whom received standardized didactic and experiential training (Appendix 1).

The pharmacists’ AMH and general pharmacy experience ranged from <1 to 3 years and <1 to 5 years, respectively. For PSPTs, AMH and general pharmacy experience ranged from <1 to 2 years and 1 to 17 years, respectively. Three additional pharmacists were involved in supervising PSPTs, and their experience fell within the aforementioned ranges, except for one pharmacist with general pharmacy experience of 16 years. The CSMC Institutional Review Board approved this study with oral consent from pharmacy staff.

For the trial, pharmacists and PSPTs obtained AMHs from 185 patients identified as high-risk for ADEs in the CSMC Emergency Department (ED). Patients were randomized into each arm using RANDI2 software11 if they met one of the trial inclusion criteria, accessed via electronic health record (EHR) (Appendix 2). For several days during this trial, a trained research nurse shadowed pharmacists and PSPTs to record tasks performed, as well as the actual time, including start and end times, dedicated to each task.

After excluding AMHs with incomplete data, we calculated mean AMH times and component task times (Table). We compared mean times for pharmacists and PSPTs using two sample t tests (Table). We calculated mean times of tasks across only AMHs that required the task, mean times of tasks across all AMHs studied, regardless of whether the AMH required the task or not (assigning 0 minutes for the task if it was not required), and percent mean time of task per patient for providers combined (Table).

We calculated Pearson product-moment correlation estimates between AMH time and these continuous variables: patient age; total number of EHR medications; number of chronic EHR medications; years of provider AMH experience; and years of provider general pharmacy experience. Using two sample t tests, we also checked for associations between AMH time and the following categorical variables: sex; presence of a patient-provided medication list; caregiver availability; and altered mental status, as determined by review of the ED physician’s note. Caregiver availability was defined as the availability of a family member, caregiver, or medication administration record (MAR) for patients residing at a skilled nursing facility (SNF). The rationale for combining these variables is that SNF nurses are the primary caregivers responsible for administering medications, and the MAR is reflective of their actions.

After reviewing our initial data, we decided to increase our sample size from 20 to 30 complete AMHs. Because the trial had concluded, we selected 10 additional patients who met trial criteria and who would already have an AMH obtained by pharmacy staff for operational reasons. The only difference with the second set of patients (n = 10) is that we did not randomize patients into each arm, but chose to focus on AMHs obtained by PSPTs, as there is a greater need in the literature to study PSPTs. After finalizing data collection, the aforementioned analyses were conducted on the complete data set.

Lastly, we estimated the mean labor cost for pharmacists and PSPTs to obtain an AMH by using 2015 US BLS hourly wage data for pharmacists ($57.34) and pharmacy technicians ($15.23).7 The cost for a pharmacist-obtained AMH was calculated by multiplying the measured mean time a pharmacist needed to obtain an AMH by $57.34 per hour. The cost for a PSPT-obtained AMH was the sum of the PSPT’s measured mean time to obtain an AMH multiplied by $15.23 per hour and the measured mean pharmacist supervisory time multiplied by $57.34 per hour.

RESULTS

Of the 37 observed AMHs, 30 had complete data. Seven AMHs were excluded because not all task times were recorded, due to the schedule restraints of the research nurse. Pharmacists and PSPTs obtained 12 and 18 AMHs, respectively. Mean patient ages were 83.3 (95% confidence interval [CI], 77.3-89.2) and 79.8 (95% CI, 71.5-88.0), for pharmacists and PSPTs, respectively (P = 0.55). Patient’s EHRs contained a mean of 14.3 (95% CI, 11.2-17.5) and 16.3 (95% CI, 13.2-19.5) medications, prior to pharmacists and PSPTs obtaining an AMH, respectively (P = 0.41).

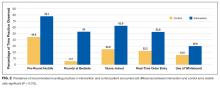

The mean time pharmacists and PSPTs needed to obtain an AMH was 58.5 (95% CI, 46.9-70.1) and 79.4 (95% CI, 59.1-99.8) minutes, respectively (P = 0.14). Summary time data per provider is reported in the Figure. The mean time for pharmacist supervision of technicians was 26 (95% CI, 14.9-37.1) minutes. Mean times of tasks and comparisons of these means times between providers are reported in the Table. The percent mean time for each task per patient for providers combined is also reported in the Table, in which utilizing the EHR was associated with the greatest percentage of time spent at 42.8% (95% CI, 37.4-48.2).

In the 18 cases for which a caregiver (or SNF medication list) was available, providers needed only 58.1 (95% CI, 44.1-72.1) minutes to obtain an AMH, as compared with 90.5 (95% CI, 67.9-113.1) minutes for the 12 cases lacking these resources (P = 0.02). We also found that among PSPTs, years of AMH experience were positively correlated with AMH time (coefficient of correlation 0.49, P = 0.04). No other studied variables were correlated with or associated with differential AMH times.

We estimated mean labor costs for pharmacists and PSPTs to obtain AMHs as $55.91 (95% CI, 44.9-67.0) and $45.00 (95% CI, 29.7-60.4) per patient, respectively (P = 0.32). In the latter case, $24.85 (95% CI, 14.3-35.4) of the $45.00 would be needed for pharmacist supervisory time. The labor cost for a PSPT-obtained AMH ($45.00) was the sum of the PSPT’s mean time (79.4 minutes) multiplied by technician wage data ($15.23/hour) and supervising pharmacist’s mean time (26.0 minutes) multiplied by pharmacist wage data ($57.34/hour).

DISCUSSION

Although limited by sample size, we observed no difference in time or costs of obtaining AMHs between pharmacists and PSPTs. Several prior studies reported that pharmacists and technicians needed less time to obtain AMHs (20-40 minutes), as compared with our findings.12-14 However, most prior studies used younger, healthier patients. Additionally, they used clinician self-reporting instead of third-person observer time and motion methodology. Indeed, the pharmacist times we observed in this study were consistent with prior findings6 that used accepted third-person observer time and motion methodology.10

We observed more variation in time to obtain AMHs among PSPTs than among pharmacists. While variation may be at least in part to the greater number of technicians studied, variation also points to the need for training and oversight of PSPTs. Selection of PSPTs with prior experience interacting with patients and functioning with higher levels of autonomy, standardized training of PSPTs, and consistent dedication of trained PSPTs to AMH functions to maintain their skills, may help to minimize such variation.

Limitations include the use of a single center and a small sample size. As such, the study may be underpowered to demonstrate statistically significant differences between providers. Furthermore, 7 AMHs (19%) had to be excluded because complete task times were missing. This was exclusively because the workday of the research nurse ended before the AMH had been completed. Another limitation was that the tasks observed could have been dissected further to identify even more specific factors that could be targeted to decrease AMH times. We recommend that future studies be larger, investigate in more depth various factors associated with time needed to obtain AMHs, consider which patients would most likely benefit from PSPTs, and use a measure of value (eg, number of history errors prevented/dollar spent).

In summary, we found that PSPTs can obtain AMHs for similar cost to pharmacists. It will be especially important to know whether PSPTs maintain the accuracy documented in prior studies.8-9 If that continues to be the case, we expect our findings to allow many hospitals to implement programs using PSPTs to obtain accurate AMHs.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Katherine M. Abdel-Razek for her role in data collection.

Disclosure

This research was supported by NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Science UCLA CTSI Grant Number KL2TR000122 and National Institute on Aging Grant Number K23 AG049181-01 (Pevnick). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The investigators retained full independence in the conduct of this research.

1. Mergenhagen KA, Blum SS, Kugler A, et al. Pharmacist- versus physician-initiated admission medication reconciliation: impact on adverse drug events. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2012;10(4):242-250. PubMed

2. Mills PR, McGuffie AC. Formal medication reconciliation within the emergency department reduces the medication error rates for emergency admissions. Emerg Med J. 2010;27(12):911-915. PubMed

3. Boockvar KS, LaCorte HC, Giambanco V, Fridman B, Siu A. Medication reconciliation for reducing drug-discrepancy adverse events. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006;4(3):236-243. PubMed

4. Mueller SK, Sponsler KC, Kripalani S, Schnipper JL. Hospital-based medication reconciliation practices: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(14):1057-1069. PubMed

5. Lee KP, Hartridge C, Corbett K, Vittinghoff E, Auerbach AD. “Whose job is it, really?” Physicians’, nurses’, and pharmacists’ perspectives on completing inpatient medication reconciliation. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(3):184-186. PubMed

6. Meguerditchian AN, Krotneva S, Reidel K, Huang A, Tamblyn R. Medication reconciliation at admission and discharge: a time and motion study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:485. PubMed

7. Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor, Occupational Employment Statistics, May 2015. Pharmacists and Pharmacy Technicians. http://www.bls.gov/oes/. Accessed July 15, 2016.

8. Johnston R, Saulnier L, Gould O. Best possible medication history in the emergency department: comparing pharmacy technicians and pharmacists. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2010;63(5):359-365. PubMed

9. Pevnick JM, Nguyen CB, Jackevicius CA, et al. Minimizing medication histories errors for patients admitted to the hospital through the emergency department: a three-arm pragmatic randomized controlled trial of adding admission medication history interviews by pharmacists or pharmacist-supervised pharmacy technicians to usual care. J Patient Cent Res Rev. 2015;2:93.

10. Zheng K, Guo MH, Hanauer DA. Using the time and motion method to study clinical work processes and workflow: methodological inconsistencies and a call for standardized research. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(5):704-710. PubMed

11. Schrimpf D, Plotnicki L, Pilz LR. Web-based open source application for the randomization process in clinical trials: RANDI2. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;48(7):465-467. PubMed

12. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists and the American Pharmacists Association. ASHP-APhA medication management in care transitions best practices. http://media.pharmacist.com/practice/ASHP_APhA_MedicationManagementinCareTransitionsBestPracticesReport2_2013.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2016.

13. Kent AJ, Harrington L, Skinner J. Medication reconciliation by a pharmacist in the emergency department: a pilot project. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2009;62(3):238-242. PubMed

14. Sen S, Siemianowski L, Murphy M, McAllister SC. Implementation of a pharmacy technician-centered medication reconciliation program at an urban teaching medical center. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71(1):51-56. PubMed

Using pharmacists to obtain admission medication histories (AMHs) reduces medication errors by 70% to 83% and resultant adverse drug events (ADEs) by 15%.1-3 Dissemination of this practice has been limited by several factors, including clinician practice models, staff availability, confusion in provider roles and accountability, and absence of standardized best practices.4-5 This paper assesses one of these barriers: the high cost of utilizing pharmacists. Third-person observer time and motion analysis shows that pharmacists require 46 and 92 minutes to obtain AMHs from medical and geriatric patients,6 respectively, resulting in pharmacist costs of $44 to $88 per patient, based on 2015 US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) hourly wage data for pharmacists ($57.34).7

Ph

METHODS

This study originated as part of a randomized, controlled trial conducted during January-February 2014 at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center (CSMC), an 896-bed, university-affiliated, not-for-profit hospital.9 Pharmacy staff included pharmacists, PGY-1 pharmacy residents, and pharmacy technicians, each of whom received standardized didactic and experiential training (Appendix 1).

The pharmacists’ AMH and general pharmacy experience ranged from <1 to 3 years and <1 to 5 years, respectively. For PSPTs, AMH and general pharmacy experience ranged from <1 to 2 years and 1 to 17 years, respectively. Three additional pharmacists were involved in supervising PSPTs, and their experience fell within the aforementioned ranges, except for one pharmacist with general pharmacy experience of 16 years. The CSMC Institutional Review Board approved this study with oral consent from pharmacy staff.

For the trial, pharmacists and PSPTs obtained AMHs from 185 patients identified as high-risk for ADEs in the CSMC Emergency Department (ED). Patients were randomized into each arm using RANDI2 software11 if they met one of the trial inclusion criteria, accessed via electronic health record (EHR) (Appendix 2). For several days during this trial, a trained research nurse shadowed pharmacists and PSPTs to record tasks performed, as well as the actual time, including start and end times, dedicated to each task.

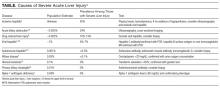

After excluding AMHs with incomplete data, we calculated mean AMH times and component task times (Table). We compared mean times for pharmacists and PSPTs using two sample t tests (Table). We calculated mean times of tasks across only AMHs that required the task, mean times of tasks across all AMHs studied, regardless of whether the AMH required the task or not (assigning 0 minutes for the task if it was not required), and percent mean time of task per patient for providers combined (Table).

We calculated Pearson product-moment correlation estimates between AMH time and these continuous variables: patient age; total number of EHR medications; number of chronic EHR medications; years of provider AMH experience; and years of provider general pharmacy experience. Using two sample t tests, we also checked for associations between AMH time and the following categorical variables: sex; presence of a patient-provided medication list; caregiver availability; and altered mental status, as determined by review of the ED physician’s note. Caregiver availability was defined as the availability of a family member, caregiver, or medication administration record (MAR) for patients residing at a skilled nursing facility (SNF). The rationale for combining these variables is that SNF nurses are the primary caregivers responsible for administering medications, and the MAR is reflective of their actions.

After reviewing our initial data, we decided to increase our sample size from 20 to 30 complete AMHs. Because the trial had concluded, we selected 10 additional patients who met trial criteria and who would already have an AMH obtained by pharmacy staff for operational reasons. The only difference with the second set of patients (n = 10) is that we did not randomize patients into each arm, but chose to focus on AMHs obtained by PSPTs, as there is a greater need in the literature to study PSPTs. After finalizing data collection, the aforementioned analyses were conducted on the complete data set.

Lastly, we estimated the mean labor cost for pharmacists and PSPTs to obtain an AMH by using 2015 US BLS hourly wage data for pharmacists ($57.34) and pharmacy technicians ($15.23).7 The cost for a pharmacist-obtained AMH was calculated by multiplying the measured mean time a pharmacist needed to obtain an AMH by $57.34 per hour. The cost for a PSPT-obtained AMH was the sum of the PSPT’s measured mean time to obtain an AMH multiplied by $15.23 per hour and the measured mean pharmacist supervisory time multiplied by $57.34 per hour.

RESULTS

Of the 37 observed AMHs, 30 had complete data. Seven AMHs were excluded because not all task times were recorded, due to the schedule restraints of the research nurse. Pharmacists and PSPTs obtained 12 and 18 AMHs, respectively. Mean patient ages were 83.3 (95% confidence interval [CI], 77.3-89.2) and 79.8 (95% CI, 71.5-88.0), for pharmacists and PSPTs, respectively (P = 0.55). Patient’s EHRs contained a mean of 14.3 (95% CI, 11.2-17.5) and 16.3 (95% CI, 13.2-19.5) medications, prior to pharmacists and PSPTs obtaining an AMH, respectively (P = 0.41).

The mean time pharmacists and PSPTs needed to obtain an AMH was 58.5 (95% CI, 46.9-70.1) and 79.4 (95% CI, 59.1-99.8) minutes, respectively (P = 0.14). Summary time data per provider is reported in the Figure. The mean time for pharmacist supervision of technicians was 26 (95% CI, 14.9-37.1) minutes. Mean times of tasks and comparisons of these means times between providers are reported in the Table. The percent mean time for each task per patient for providers combined is also reported in the Table, in which utilizing the EHR was associated with the greatest percentage of time spent at 42.8% (95% CI, 37.4-48.2).

In the 18 cases for which a caregiver (or SNF medication list) was available, providers needed only 58.1 (95% CI, 44.1-72.1) minutes to obtain an AMH, as compared with 90.5 (95% CI, 67.9-113.1) minutes for the 12 cases lacking these resources (P = 0.02). We also found that among PSPTs, years of AMH experience were positively correlated with AMH time (coefficient of correlation 0.49, P = 0.04). No other studied variables were correlated with or associated with differential AMH times.

We estimated mean labor costs for pharmacists and PSPTs to obtain AMHs as $55.91 (95% CI, 44.9-67.0) and $45.00 (95% CI, 29.7-60.4) per patient, respectively (P = 0.32). In the latter case, $24.85 (95% CI, 14.3-35.4) of the $45.00 would be needed for pharmacist supervisory time. The labor cost for a PSPT-obtained AMH ($45.00) was the sum of the PSPT’s mean time (79.4 minutes) multiplied by technician wage data ($15.23/hour) and supervising pharmacist’s mean time (26.0 minutes) multiplied by pharmacist wage data ($57.34/hour).

DISCUSSION

Although limited by sample size, we observed no difference in time or costs of obtaining AMHs between pharmacists and PSPTs. Several prior studies reported that pharmacists and technicians needed less time to obtain AMHs (20-40 minutes), as compared with our findings.12-14 However, most prior studies used younger, healthier patients. Additionally, they used clinician self-reporting instead of third-person observer time and motion methodology. Indeed, the pharmacist times we observed in this study were consistent with prior findings6 that used accepted third-person observer time and motion methodology.10

We observed more variation in time to obtain AMHs among PSPTs than among pharmacists. While variation may be at least in part to the greater number of technicians studied, variation also points to the need for training and oversight of PSPTs. Selection of PSPTs with prior experience interacting with patients and functioning with higher levels of autonomy, standardized training of PSPTs, and consistent dedication of trained PSPTs to AMH functions to maintain their skills, may help to minimize such variation.

Limitations include the use of a single center and a small sample size. As such, the study may be underpowered to demonstrate statistically significant differences between providers. Furthermore, 7 AMHs (19%) had to be excluded because complete task times were missing. This was exclusively because the workday of the research nurse ended before the AMH had been completed. Another limitation was that the tasks observed could have been dissected further to identify even more specific factors that could be targeted to decrease AMH times. We recommend that future studies be larger, investigate in more depth various factors associated with time needed to obtain AMHs, consider which patients would most likely benefit from PSPTs, and use a measure of value (eg, number of history errors prevented/dollar spent).

In summary, we found that PSPTs can obtain AMHs for similar cost to pharmacists. It will be especially important to know whether PSPTs maintain the accuracy documented in prior studies.8-9 If that continues to be the case, we expect our findings to allow many hospitals to implement programs using PSPTs to obtain accurate AMHs.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Katherine M. Abdel-Razek for her role in data collection.

Disclosure

This research was supported by NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Science UCLA CTSI Grant Number KL2TR000122 and National Institute on Aging Grant Number K23 AG049181-01 (Pevnick). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The investigators retained full independence in the conduct of this research.

Using pharmacists to obtain admission medication histories (AMHs) reduces medication errors by 70% to 83% and resultant adverse drug events (ADEs) by 15%.1-3 Dissemination of this practice has been limited by several factors, including clinician practice models, staff availability, confusion in provider roles and accountability, and absence of standardized best practices.4-5 This paper assesses one of these barriers: the high cost of utilizing pharmacists. Third-person observer time and motion analysis shows that pharmacists require 46 and 92 minutes to obtain AMHs from medical and geriatric patients,6 respectively, resulting in pharmacist costs of $44 to $88 per patient, based on 2015 US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) hourly wage data for pharmacists ($57.34).7

Ph

METHODS

This study originated as part of a randomized, controlled trial conducted during January-February 2014 at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center (CSMC), an 896-bed, university-affiliated, not-for-profit hospital.9 Pharmacy staff included pharmacists, PGY-1 pharmacy residents, and pharmacy technicians, each of whom received standardized didactic and experiential training (Appendix 1).

The pharmacists’ AMH and general pharmacy experience ranged from <1 to 3 years and <1 to 5 years, respectively. For PSPTs, AMH and general pharmacy experience ranged from <1 to 2 years and 1 to 17 years, respectively. Three additional pharmacists were involved in supervising PSPTs, and their experience fell within the aforementioned ranges, except for one pharmacist with general pharmacy experience of 16 years. The CSMC Institutional Review Board approved this study with oral consent from pharmacy staff.

For the trial, pharmacists and PSPTs obtained AMHs from 185 patients identified as high-risk for ADEs in the CSMC Emergency Department (ED). Patients were randomized into each arm using RANDI2 software11 if they met one of the trial inclusion criteria, accessed via electronic health record (EHR) (Appendix 2). For several days during this trial, a trained research nurse shadowed pharmacists and PSPTs to record tasks performed, as well as the actual time, including start and end times, dedicated to each task.

After excluding AMHs with incomplete data, we calculated mean AMH times and component task times (Table). We compared mean times for pharmacists and PSPTs using two sample t tests (Table). We calculated mean times of tasks across only AMHs that required the task, mean times of tasks across all AMHs studied, regardless of whether the AMH required the task or not (assigning 0 minutes for the task if it was not required), and percent mean time of task per patient for providers combined (Table).

We calculated Pearson product-moment correlation estimates between AMH time and these continuous variables: patient age; total number of EHR medications; number of chronic EHR medications; years of provider AMH experience; and years of provider general pharmacy experience. Using two sample t tests, we also checked for associations between AMH time and the following categorical variables: sex; presence of a patient-provided medication list; caregiver availability; and altered mental status, as determined by review of the ED physician’s note. Caregiver availability was defined as the availability of a family member, caregiver, or medication administration record (MAR) for patients residing at a skilled nursing facility (SNF). The rationale for combining these variables is that SNF nurses are the primary caregivers responsible for administering medications, and the MAR is reflective of their actions.

After reviewing our initial data, we decided to increase our sample size from 20 to 30 complete AMHs. Because the trial had concluded, we selected 10 additional patients who met trial criteria and who would already have an AMH obtained by pharmacy staff for operational reasons. The only difference with the second set of patients (n = 10) is that we did not randomize patients into each arm, but chose to focus on AMHs obtained by PSPTs, as there is a greater need in the literature to study PSPTs. After finalizing data collection, the aforementioned analyses were conducted on the complete data set.

Lastly, we estimated the mean labor cost for pharmacists and PSPTs to obtain an AMH by using 2015 US BLS hourly wage data for pharmacists ($57.34) and pharmacy technicians ($15.23).7 The cost for a pharmacist-obtained AMH was calculated by multiplying the measured mean time a pharmacist needed to obtain an AMH by $57.34 per hour. The cost for a PSPT-obtained AMH was the sum of the PSPT’s measured mean time to obtain an AMH multiplied by $15.23 per hour and the measured mean pharmacist supervisory time multiplied by $57.34 per hour.

RESULTS

Of the 37 observed AMHs, 30 had complete data. Seven AMHs were excluded because not all task times were recorded, due to the schedule restraints of the research nurse. Pharmacists and PSPTs obtained 12 and 18 AMHs, respectively. Mean patient ages were 83.3 (95% confidence interval [CI], 77.3-89.2) and 79.8 (95% CI, 71.5-88.0), for pharmacists and PSPTs, respectively (P = 0.55). Patient’s EHRs contained a mean of 14.3 (95% CI, 11.2-17.5) and 16.3 (95% CI, 13.2-19.5) medications, prior to pharmacists and PSPTs obtaining an AMH, respectively (P = 0.41).

The mean time pharmacists and PSPTs needed to obtain an AMH was 58.5 (95% CI, 46.9-70.1) and 79.4 (95% CI, 59.1-99.8) minutes, respectively (P = 0.14). Summary time data per provider is reported in the Figure. The mean time for pharmacist supervision of technicians was 26 (95% CI, 14.9-37.1) minutes. Mean times of tasks and comparisons of these means times between providers are reported in the Table. The percent mean time for each task per patient for providers combined is also reported in the Table, in which utilizing the EHR was associated with the greatest percentage of time spent at 42.8% (95% CI, 37.4-48.2).

In the 18 cases for which a caregiver (or SNF medication list) was available, providers needed only 58.1 (95% CI, 44.1-72.1) minutes to obtain an AMH, as compared with 90.5 (95% CI, 67.9-113.1) minutes for the 12 cases lacking these resources (P = 0.02). We also found that among PSPTs, years of AMH experience were positively correlated with AMH time (coefficient of correlation 0.49, P = 0.04). No other studied variables were correlated with or associated with differential AMH times.

We estimated mean labor costs for pharmacists and PSPTs to obtain AMHs as $55.91 (95% CI, 44.9-67.0) and $45.00 (95% CI, 29.7-60.4) per patient, respectively (P = 0.32). In the latter case, $24.85 (95% CI, 14.3-35.4) of the $45.00 would be needed for pharmacist supervisory time. The labor cost for a PSPT-obtained AMH ($45.00) was the sum of the PSPT’s mean time (79.4 minutes) multiplied by technician wage data ($15.23/hour) and supervising pharmacist’s mean time (26.0 minutes) multiplied by pharmacist wage data ($57.34/hour).

DISCUSSION

Although limited by sample size, we observed no difference in time or costs of obtaining AMHs between pharmacists and PSPTs. Several prior studies reported that pharmacists and technicians needed less time to obtain AMHs (20-40 minutes), as compared with our findings.12-14 However, most prior studies used younger, healthier patients. Additionally, they used clinician self-reporting instead of third-person observer time and motion methodology. Indeed, the pharmacist times we observed in this study were consistent with prior findings6 that used accepted third-person observer time and motion methodology.10

We observed more variation in time to obtain AMHs among PSPTs than among pharmacists. While variation may be at least in part to the greater number of technicians studied, variation also points to the need for training and oversight of PSPTs. Selection of PSPTs with prior experience interacting with patients and functioning with higher levels of autonomy, standardized training of PSPTs, and consistent dedication of trained PSPTs to AMH functions to maintain their skills, may help to minimize such variation.

Limitations include the use of a single center and a small sample size. As such, the study may be underpowered to demonstrate statistically significant differences between providers. Furthermore, 7 AMHs (19%) had to be excluded because complete task times were missing. This was exclusively because the workday of the research nurse ended before the AMH had been completed. Another limitation was that the tasks observed could have been dissected further to identify even more specific factors that could be targeted to decrease AMH times. We recommend that future studies be larger, investigate in more depth various factors associated with time needed to obtain AMHs, consider which patients would most likely benefit from PSPTs, and use a measure of value (eg, number of history errors prevented/dollar spent).

In summary, we found that PSPTs can obtain AMHs for similar cost to pharmacists. It will be especially important to know whether PSPTs maintain the accuracy documented in prior studies.8-9 If that continues to be the case, we expect our findings to allow many hospitals to implement programs using PSPTs to obtain accurate AMHs.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Katherine M. Abdel-Razek for her role in data collection.

Disclosure

This research was supported by NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Science UCLA CTSI Grant Number KL2TR000122 and National Institute on Aging Grant Number K23 AG049181-01 (Pevnick). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The investigators retained full independence in the conduct of this research.

1. Mergenhagen KA, Blum SS, Kugler A, et al. Pharmacist- versus physician-initiated admission medication reconciliation: impact on adverse drug events. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2012;10(4):242-250. PubMed

2. Mills PR, McGuffie AC. Formal medication reconciliation within the emergency department reduces the medication error rates for emergency admissions. Emerg Med J. 2010;27(12):911-915. PubMed

3. Boockvar KS, LaCorte HC, Giambanco V, Fridman B, Siu A. Medication reconciliation for reducing drug-discrepancy adverse events. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006;4(3):236-243. PubMed

4. Mueller SK, Sponsler KC, Kripalani S, Schnipper JL. Hospital-based medication reconciliation practices: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(14):1057-1069. PubMed

5. Lee KP, Hartridge C, Corbett K, Vittinghoff E, Auerbach AD. “Whose job is it, really?” Physicians’, nurses’, and pharmacists’ perspectives on completing inpatient medication reconciliation. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(3):184-186. PubMed

6. Meguerditchian AN, Krotneva S, Reidel K, Huang A, Tamblyn R. Medication reconciliation at admission and discharge: a time and motion study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:485. PubMed

7. Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor, Occupational Employment Statistics, May 2015. Pharmacists and Pharmacy Technicians. http://www.bls.gov/oes/. Accessed July 15, 2016.

8. Johnston R, Saulnier L, Gould O. Best possible medication history in the emergency department: comparing pharmacy technicians and pharmacists. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2010;63(5):359-365. PubMed

9. Pevnick JM, Nguyen CB, Jackevicius CA, et al. Minimizing medication histories errors for patients admitted to the hospital through the emergency department: a three-arm pragmatic randomized controlled trial of adding admission medication history interviews by pharmacists or pharmacist-supervised pharmacy technicians to usual care. J Patient Cent Res Rev. 2015;2:93.

10. Zheng K, Guo MH, Hanauer DA. Using the time and motion method to study clinical work processes and workflow: methodological inconsistencies and a call for standardized research. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(5):704-710. PubMed

11. Schrimpf D, Plotnicki L, Pilz LR. Web-based open source application for the randomization process in clinical trials: RANDI2. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;48(7):465-467. PubMed

12. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists and the American Pharmacists Association. ASHP-APhA medication management in care transitions best practices. http://media.pharmacist.com/practice/ASHP_APhA_MedicationManagementinCareTransitionsBestPracticesReport2_2013.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2016.

13. Kent AJ, Harrington L, Skinner J. Medication reconciliation by a pharmacist in the emergency department: a pilot project. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2009;62(3):238-242. PubMed

14. Sen S, Siemianowski L, Murphy M, McAllister SC. Implementation of a pharmacy technician-centered medication reconciliation program at an urban teaching medical center. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71(1):51-56. PubMed

1. Mergenhagen KA, Blum SS, Kugler A, et al. Pharmacist- versus physician-initiated admission medication reconciliation: impact on adverse drug events. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2012;10(4):242-250. PubMed

2. Mills PR, McGuffie AC. Formal medication reconciliation within the emergency department reduces the medication error rates for emergency admissions. Emerg Med J. 2010;27(12):911-915. PubMed

3. Boockvar KS, LaCorte HC, Giambanco V, Fridman B, Siu A. Medication reconciliation for reducing drug-discrepancy adverse events. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006;4(3):236-243. PubMed

4. Mueller SK, Sponsler KC, Kripalani S, Schnipper JL. Hospital-based medication reconciliation practices: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(14):1057-1069. PubMed

5. Lee KP, Hartridge C, Corbett K, Vittinghoff E, Auerbach AD. “Whose job is it, really?” Physicians’, nurses’, and pharmacists’ perspectives on completing inpatient medication reconciliation. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(3):184-186. PubMed

6. Meguerditchian AN, Krotneva S, Reidel K, Huang A, Tamblyn R. Medication reconciliation at admission and discharge: a time and motion study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:485. PubMed

7. Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor, Occupational Employment Statistics, May 2015. Pharmacists and Pharmacy Technicians. http://www.bls.gov/oes/. Accessed July 15, 2016.

8. Johnston R, Saulnier L, Gould O. Best possible medication history in the emergency department: comparing pharmacy technicians and pharmacists. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2010;63(5):359-365. PubMed

9. Pevnick JM, Nguyen CB, Jackevicius CA, et al. Minimizing medication histories errors for patients admitted to the hospital through the emergency department: a three-arm pragmatic randomized controlled trial of adding admission medication history interviews by pharmacists or pharmacist-supervised pharmacy technicians to usual care. J Patient Cent Res Rev. 2015;2:93.

10. Zheng K, Guo MH, Hanauer DA. Using the time and motion method to study clinical work processes and workflow: methodological inconsistencies and a call for standardized research. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(5):704-710. PubMed

11. Schrimpf D, Plotnicki L, Pilz LR. Web-based open source application for the randomization process in clinical trials: RANDI2. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;48(7):465-467. PubMed

12. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists and the American Pharmacists Association. ASHP-APhA medication management in care transitions best practices. http://media.pharmacist.com/practice/ASHP_APhA_MedicationManagementinCareTransitionsBestPracticesReport2_2013.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2016.

13. Kent AJ, Harrington L, Skinner J. Medication reconciliation by a pharmacist in the emergency department: a pilot project. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2009;62(3):238-242. PubMed

14. Sen S, Siemianowski L, Murphy M, McAllister SC. Implementation of a pharmacy technician-centered medication reconciliation program at an urban teaching medical center. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71(1):51-56. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Nondirected testing for inpatients with severe liver injury

The “Things We Do for No Reason” series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

CASE REPORT

A 68-year-old woman with ischemic cardiomyopathy was admitted with abdominal cramping, diarrhea, and nausea, which had left her unable to keep food and liquids down for 2 days. She had been taking diuretics and had a remote history of intravenous drug use. On admission, she was afebrile and had blood pressure of 100/60 mm Hg and a heart rate of 100 bpm. Her extremities were cool and clammy. Blood test results showed an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level of 1510 IU/L and an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level of 1643 IU/L. The patient’s clinician did not know her baseline ALT and AST levels and thought the best approach was to identify the cause of the transaminase elevation.

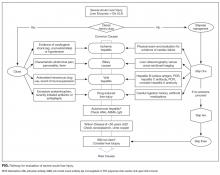

Severe acute liver injury (liver enzymes, >10 × upper limit of normal [ULN], usually 40 IU/L) is a common presentation among hospitalized patients. Between 1997 and 2015, 1.5% of patients admitted to our hospital had severe liver injury. In another large cohort of hospitalized patients,1 0.6% had an ALT level higher than 1000 IU/L (~20 × ULN). A precise diagnosis is often needed to direct appropriate therapy, and serologic tests are available for many conditions, both common and rare (Table). Given the relative ease of bundled blood testing, nondirected testing has emerged as a popular, if reflexive, strategy.2-5 In this approach, clinicians evaluate each patient for the set of testable diseases all at once—in contrast to taking a directed, stepwise testing approach guided by the patient’s history.