User login

Adherence and discontinuation limit triptan outcomes

a new Danish study shows.

“Few people continue on triptans either due to lack of efficacy or too many adverse events,” said Alan Rapoport, MD, clinical professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles. “Some people overuse triptans when they are available and work well, but the patients are not properly informed, and do not listen.”

Migraine headaches fall among some of the most common neurologic disorders and claims the No. 2 spot in diseases that contribute to life lived with disability. An estimated 11.7% have migraine episodes annually, and the disorder carries a high prevalence through the duration of the patient’s life.

Triptans were noted as being a highly effective solution for acute migraine management when they were first introduced in the early 1990s and still remain the first-line treatment for acute migraine management not adequately controlled by ordinary analgesics and NSAIDs. As a drug class, the side-effect profile of triptans can vary, but frequent users run the risk of medication overuse headache, a condition noted by migraines of increased frequency and intensity.

25 years of triptan use

Study investigators conducted a nationwide, register-based cohort study using data collected from 7,435,758 Danish residents who accessed the public health care system between Jan. 1, 1994, and Oct. 31, 2019. The time frame accounts for a period of 139.0 million person-years when the residents were both alive and living in Denmark. Their findings were published online Feb. 14, 2021, in Cephalalgia.

Researchers evaluated and summarized purchases of all triptans in all dosage forms sold in Denmark during that time frame. These were sumatriptan, naratriptan, zolmitriptan, rizatriptan, almotriptan, eletriptan, and frovatriptan. Based on their finding, 381,695 patients purchased triptans at least one time. Triptan users were more likely to be female (75.7%) than male (24.3%).

Dr. Rapoport, who was not involved in the study, feels the differences in use between genders extrapolate to the U.S. migraine population as well. “Three times more women have migraines than men and buy triptans in that ratio,” he said.

Any patient who purchased at least one of any triptan at any point during the course of the study was classified as a triptan user. Triptan overuse is defined as using a triptan greater for at least 10 days a month for 3 consecutive months, as defined by the International Classification of Headache Disorders. It’s important to note that triptan are prescribed to patients for only two indications – migraines and cluster headaches. However, cluster headaches are extremely rare.

The study’s investigators summarized data collected throughout Denmark for more than a quarter of a century. The findings show an increase in triptan use from 345 defined daily doses to 945 defined daily doses per 1,000 residents per year along with an increased prevalence on triptan use from 5.17 to 14.57 per 1,000 inhabitants. In addition, 12.3% of the Danish residents who had migraines bought a triptan between 2014 and 2019 – data Dr. Rapoport noted falls in lines with trends in other Western countries, which range between 12% and 13%.

Nearly half of the first-time triptan buyers (43%) did not purchase another triptan for 5 years. In conflict with established guidelines, 90% of patients that discontinued triptan-based treatment had tried only one triptan type.

One important factor contributing to the ease of data collection is that the Danish population has free health care, coupled with sizable reimbursements for their spending. The country’s accessible health care system negates the effects of barriers related to price and availability while engendering data that more accurately reflects the patients’ experience based on treatment need and satisfaction.

“In a cohort with access to free clinical consultations and low medication costs, we observed low rates of triptan adherence, likely due to disappointing efficacy and/or unpleasant side effects rather than economic considerations. Triptan success continues to be hindered by poor implementation of clinical guidelines and high rates of treatment discontinuance,” the researchers concluded.

“The most surprising thing about this study is it is exactly what I would have expected if triptans in the U.S. were free,” Dr. Rapoport said.

Dr. Rapoport is the editor in chief of Neurology Reviews and serves as a consultant to several pharmaceutical companies.

a new Danish study shows.

“Few people continue on triptans either due to lack of efficacy or too many adverse events,” said Alan Rapoport, MD, clinical professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles. “Some people overuse triptans when they are available and work well, but the patients are not properly informed, and do not listen.”

Migraine headaches fall among some of the most common neurologic disorders and claims the No. 2 spot in diseases that contribute to life lived with disability. An estimated 11.7% have migraine episodes annually, and the disorder carries a high prevalence through the duration of the patient’s life.

Triptans were noted as being a highly effective solution for acute migraine management when they were first introduced in the early 1990s and still remain the first-line treatment for acute migraine management not adequately controlled by ordinary analgesics and NSAIDs. As a drug class, the side-effect profile of triptans can vary, but frequent users run the risk of medication overuse headache, a condition noted by migraines of increased frequency and intensity.

25 years of triptan use

Study investigators conducted a nationwide, register-based cohort study using data collected from 7,435,758 Danish residents who accessed the public health care system between Jan. 1, 1994, and Oct. 31, 2019. The time frame accounts for a period of 139.0 million person-years when the residents were both alive and living in Denmark. Their findings were published online Feb. 14, 2021, in Cephalalgia.

Researchers evaluated and summarized purchases of all triptans in all dosage forms sold in Denmark during that time frame. These were sumatriptan, naratriptan, zolmitriptan, rizatriptan, almotriptan, eletriptan, and frovatriptan. Based on their finding, 381,695 patients purchased triptans at least one time. Triptan users were more likely to be female (75.7%) than male (24.3%).

Dr. Rapoport, who was not involved in the study, feels the differences in use between genders extrapolate to the U.S. migraine population as well. “Three times more women have migraines than men and buy triptans in that ratio,” he said.

Any patient who purchased at least one of any triptan at any point during the course of the study was classified as a triptan user. Triptan overuse is defined as using a triptan greater for at least 10 days a month for 3 consecutive months, as defined by the International Classification of Headache Disorders. It’s important to note that triptan are prescribed to patients for only two indications – migraines and cluster headaches. However, cluster headaches are extremely rare.

The study’s investigators summarized data collected throughout Denmark for more than a quarter of a century. The findings show an increase in triptan use from 345 defined daily doses to 945 defined daily doses per 1,000 residents per year along with an increased prevalence on triptan use from 5.17 to 14.57 per 1,000 inhabitants. In addition, 12.3% of the Danish residents who had migraines bought a triptan between 2014 and 2019 – data Dr. Rapoport noted falls in lines with trends in other Western countries, which range between 12% and 13%.

Nearly half of the first-time triptan buyers (43%) did not purchase another triptan for 5 years. In conflict with established guidelines, 90% of patients that discontinued triptan-based treatment had tried only one triptan type.

One important factor contributing to the ease of data collection is that the Danish population has free health care, coupled with sizable reimbursements for their spending. The country’s accessible health care system negates the effects of barriers related to price and availability while engendering data that more accurately reflects the patients’ experience based on treatment need and satisfaction.

“In a cohort with access to free clinical consultations and low medication costs, we observed low rates of triptan adherence, likely due to disappointing efficacy and/or unpleasant side effects rather than economic considerations. Triptan success continues to be hindered by poor implementation of clinical guidelines and high rates of treatment discontinuance,” the researchers concluded.

“The most surprising thing about this study is it is exactly what I would have expected if triptans in the U.S. were free,” Dr. Rapoport said.

Dr. Rapoport is the editor in chief of Neurology Reviews and serves as a consultant to several pharmaceutical companies.

a new Danish study shows.

“Few people continue on triptans either due to lack of efficacy or too many adverse events,” said Alan Rapoport, MD, clinical professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles. “Some people overuse triptans when they are available and work well, but the patients are not properly informed, and do not listen.”

Migraine headaches fall among some of the most common neurologic disorders and claims the No. 2 spot in diseases that contribute to life lived with disability. An estimated 11.7% have migraine episodes annually, and the disorder carries a high prevalence through the duration of the patient’s life.

Triptans were noted as being a highly effective solution for acute migraine management when they were first introduced in the early 1990s and still remain the first-line treatment for acute migraine management not adequately controlled by ordinary analgesics and NSAIDs. As a drug class, the side-effect profile of triptans can vary, but frequent users run the risk of medication overuse headache, a condition noted by migraines of increased frequency and intensity.

25 years of triptan use

Study investigators conducted a nationwide, register-based cohort study using data collected from 7,435,758 Danish residents who accessed the public health care system between Jan. 1, 1994, and Oct. 31, 2019. The time frame accounts for a period of 139.0 million person-years when the residents were both alive and living in Denmark. Their findings were published online Feb. 14, 2021, in Cephalalgia.

Researchers evaluated and summarized purchases of all triptans in all dosage forms sold in Denmark during that time frame. These were sumatriptan, naratriptan, zolmitriptan, rizatriptan, almotriptan, eletriptan, and frovatriptan. Based on their finding, 381,695 patients purchased triptans at least one time. Triptan users were more likely to be female (75.7%) than male (24.3%).

Dr. Rapoport, who was not involved in the study, feels the differences in use between genders extrapolate to the U.S. migraine population as well. “Three times more women have migraines than men and buy triptans in that ratio,” he said.

Any patient who purchased at least one of any triptan at any point during the course of the study was classified as a triptan user. Triptan overuse is defined as using a triptan greater for at least 10 days a month for 3 consecutive months, as defined by the International Classification of Headache Disorders. It’s important to note that triptan are prescribed to patients for only two indications – migraines and cluster headaches. However, cluster headaches are extremely rare.

The study’s investigators summarized data collected throughout Denmark for more than a quarter of a century. The findings show an increase in triptan use from 345 defined daily doses to 945 defined daily doses per 1,000 residents per year along with an increased prevalence on triptan use from 5.17 to 14.57 per 1,000 inhabitants. In addition, 12.3% of the Danish residents who had migraines bought a triptan between 2014 and 2019 – data Dr. Rapoport noted falls in lines with trends in other Western countries, which range between 12% and 13%.

Nearly half of the first-time triptan buyers (43%) did not purchase another triptan for 5 years. In conflict with established guidelines, 90% of patients that discontinued triptan-based treatment had tried only one triptan type.

One important factor contributing to the ease of data collection is that the Danish population has free health care, coupled with sizable reimbursements for their spending. The country’s accessible health care system negates the effects of barriers related to price and availability while engendering data that more accurately reflects the patients’ experience based on treatment need and satisfaction.

“In a cohort with access to free clinical consultations and low medication costs, we observed low rates of triptan adherence, likely due to disappointing efficacy and/or unpleasant side effects rather than economic considerations. Triptan success continues to be hindered by poor implementation of clinical guidelines and high rates of treatment discontinuance,” the researchers concluded.

“The most surprising thing about this study is it is exactly what I would have expected if triptans in the U.S. were free,” Dr. Rapoport said.

Dr. Rapoport is the editor in chief of Neurology Reviews and serves as a consultant to several pharmaceutical companies.

FROM CEPHALALGIA

Impact of comorbid migraine on propranolol efficacy for painful TMD

Key clinical point: Propranolol appears more effective in reducing temporomandibular disorder (TMD) pain among migraineurs, with more of the effect mediated by reduced heart rate than by decreased headache impact.

Major finding: Efficacy of propranolol for at least 30% reduction in facial pain index at week 9 was higher among 104 migraineurs (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 3.3; P = .009; P for treatment group interaction = .139) than 95 non-migraineurs (aOR, 1.3; P = .631; P for treatment group interaction = .139). Only 9% of the treatment effect was mediated by reduced headache, whereas 46% was mediated by reduced heart rate.

Study details: Data come from SOPPRANO, a phase 2b randomized controlled trial that investigated analgesic efficacy of propranolol in 200 patients with chronic myogenous TMD randomly allocated to either propranolol or placebo.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

Source: Tchivileva IE et al. Cephalalgia. 2021 Feb 9. doi: 10.1177/0333102421989268.

Key clinical point: Propranolol appears more effective in reducing temporomandibular disorder (TMD) pain among migraineurs, with more of the effect mediated by reduced heart rate than by decreased headache impact.

Major finding: Efficacy of propranolol for at least 30% reduction in facial pain index at week 9 was higher among 104 migraineurs (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 3.3; P = .009; P for treatment group interaction = .139) than 95 non-migraineurs (aOR, 1.3; P = .631; P for treatment group interaction = .139). Only 9% of the treatment effect was mediated by reduced headache, whereas 46% was mediated by reduced heart rate.

Study details: Data come from SOPPRANO, a phase 2b randomized controlled trial that investigated analgesic efficacy of propranolol in 200 patients with chronic myogenous TMD randomly allocated to either propranolol or placebo.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

Source: Tchivileva IE et al. Cephalalgia. 2021 Feb 9. doi: 10.1177/0333102421989268.

Key clinical point: Propranolol appears more effective in reducing temporomandibular disorder (TMD) pain among migraineurs, with more of the effect mediated by reduced heart rate than by decreased headache impact.

Major finding: Efficacy of propranolol for at least 30% reduction in facial pain index at week 9 was higher among 104 migraineurs (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 3.3; P = .009; P for treatment group interaction = .139) than 95 non-migraineurs (aOR, 1.3; P = .631; P for treatment group interaction = .139). Only 9% of the treatment effect was mediated by reduced headache, whereas 46% was mediated by reduced heart rate.

Study details: Data come from SOPPRANO, a phase 2b randomized controlled trial that investigated analgesic efficacy of propranolol in 200 patients with chronic myogenous TMD randomly allocated to either propranolol or placebo.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

Source: Tchivileva IE et al. Cephalalgia. 2021 Feb 9. doi: 10.1177/0333102421989268.

Is the keto diet effective for refractory chronic migraine?

Key clinical point: A 3-month ketogenic diet (KD) resulted in a reduction of painful symptoms of drug refractory chronic migraine.

Major finding: KD significantly reduced the number of migraine days/month from a median of 30 days to 7.5 days (P less than .0001), hours of migraine/day from a median of 24 hours to 5.5 hours (P less than .0016), and pain level at maximum value for 83% of participants that improved for 55% of them (P less than .0024). The median number of drugs taken in a month reduced from 30 to 6 doses.

Study details: This open-label, single-arm clinical trial assessed 38 patients with refractory chronic migraine who adopted a KD for 3 months.

Disclosures: No source of funding was declared. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Bongiovanni D et al. Neurol Sci. 2021 Feb 1. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05078-5.

Key clinical point: A 3-month ketogenic diet (KD) resulted in a reduction of painful symptoms of drug refractory chronic migraine.

Major finding: KD significantly reduced the number of migraine days/month from a median of 30 days to 7.5 days (P less than .0001), hours of migraine/day from a median of 24 hours to 5.5 hours (P less than .0016), and pain level at maximum value for 83% of participants that improved for 55% of them (P less than .0024). The median number of drugs taken in a month reduced from 30 to 6 doses.

Study details: This open-label, single-arm clinical trial assessed 38 patients with refractory chronic migraine who adopted a KD for 3 months.

Disclosures: No source of funding was declared. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Bongiovanni D et al. Neurol Sci. 2021 Feb 1. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05078-5.

Key clinical point: A 3-month ketogenic diet (KD) resulted in a reduction of painful symptoms of drug refractory chronic migraine.

Major finding: KD significantly reduced the number of migraine days/month from a median of 30 days to 7.5 days (P less than .0001), hours of migraine/day from a median of 24 hours to 5.5 hours (P less than .0016), and pain level at maximum value for 83% of participants that improved for 55% of them (P less than .0024). The median number of drugs taken in a month reduced from 30 to 6 doses.

Study details: This open-label, single-arm clinical trial assessed 38 patients with refractory chronic migraine who adopted a KD for 3 months.

Disclosures: No source of funding was declared. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Bongiovanni D et al. Neurol Sci. 2021 Feb 1. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05078-5.

Galcanezumab may alleviate severity and symptoms of migraine

Key clinical point: Galcanezumab reduces the frequency of migraine headache days and may also potentially decrease disabling non-pain symptoms on days when migraine is present in patients with episodic and chronic migraine.

Major finding: Galcanezumab doses of 120 and 240 mg were superior to placebo in reducing the number of monthly migraine days with nausea and/or vomiting in both episodic and chronic migraine studies (all P less than .001). Both doses of galcanezumab were associated with a significant reduction in migraine headache days with photophobia and phonophobia vs. placebo in episodic (P less than .001) and chronic (P less than .001 for galcanezumab 120 mg; P =.001 for galcanezumab 240 mg) migraine studies.

Study details: A post hoc analysis of phase 3 randomized clinical trials EVOLVE-1, EVOLVE-2, and REGAIN that included a total of 2,289 patients with episodic or chronic migraine with or without aura.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, USA. K Day, VL Stauffer, V Skljarevski, M Rettiganti, E Pearlman, and SK Aurora reported being current/former full-time employees and/or minor stockholders of Eli Lilly and Company. M Ament reported being a consultant and/or on speaker bureaus for Eli Lilly and Company and others.

Source: Ament M et al. J Headache Pain. 2021 Feb 6. doi: 10.1186/s10194-021-01215-9.

Key clinical point: Galcanezumab reduces the frequency of migraine headache days and may also potentially decrease disabling non-pain symptoms on days when migraine is present in patients with episodic and chronic migraine.

Major finding: Galcanezumab doses of 120 and 240 mg were superior to placebo in reducing the number of monthly migraine days with nausea and/or vomiting in both episodic and chronic migraine studies (all P less than .001). Both doses of galcanezumab were associated with a significant reduction in migraine headache days with photophobia and phonophobia vs. placebo in episodic (P less than .001) and chronic (P less than .001 for galcanezumab 120 mg; P =.001 for galcanezumab 240 mg) migraine studies.

Study details: A post hoc analysis of phase 3 randomized clinical trials EVOLVE-1, EVOLVE-2, and REGAIN that included a total of 2,289 patients with episodic or chronic migraine with or without aura.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, USA. K Day, VL Stauffer, V Skljarevski, M Rettiganti, E Pearlman, and SK Aurora reported being current/former full-time employees and/or minor stockholders of Eli Lilly and Company. M Ament reported being a consultant and/or on speaker bureaus for Eli Lilly and Company and others.

Source: Ament M et al. J Headache Pain. 2021 Feb 6. doi: 10.1186/s10194-021-01215-9.

Key clinical point: Galcanezumab reduces the frequency of migraine headache days and may also potentially decrease disabling non-pain symptoms on days when migraine is present in patients with episodic and chronic migraine.

Major finding: Galcanezumab doses of 120 and 240 mg were superior to placebo in reducing the number of monthly migraine days with nausea and/or vomiting in both episodic and chronic migraine studies (all P less than .001). Both doses of galcanezumab were associated with a significant reduction in migraine headache days with photophobia and phonophobia vs. placebo in episodic (P less than .001) and chronic (P less than .001 for galcanezumab 120 mg; P =.001 for galcanezumab 240 mg) migraine studies.

Study details: A post hoc analysis of phase 3 randomized clinical trials EVOLVE-1, EVOLVE-2, and REGAIN that included a total of 2,289 patients with episodic or chronic migraine with or without aura.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, USA. K Day, VL Stauffer, V Skljarevski, M Rettiganti, E Pearlman, and SK Aurora reported being current/former full-time employees and/or minor stockholders of Eli Lilly and Company. M Ament reported being a consultant and/or on speaker bureaus for Eli Lilly and Company and others.

Source: Ament M et al. J Headache Pain. 2021 Feb 6. doi: 10.1186/s10194-021-01215-9.

Lasmiditan demonstrates superior pain freedom at 2 hours in at least 2 of 3 migraine attacks

Key clinical point: Lasmiditan is effective in the treatment of an acute migraine attack and demonstrates consistency of response across multiple migraine attacks

Major finding: Lasmiditan doses of 100 and 200 mg were superior to placebo for pain freedom at 2 hours during the first attack (odds ratio [OR], 3.8 and 4.6, respectively; P less than .001) and in at least 2 of 3 attacks (OR, 3.8 and 7.2, respectively; P less than .001). The incidence of severe adverse events was similar across treatment groups.

Study details: Findings are from CENTURION, a phase 3 study that randomly assigned patients with migraine with/without aura to either of 3 treatment groups for 4 attacks: lasmiditan 200 mg (n=536), lasmiditan 100 mg (n=539), or control (n=538).

Disclosures: The CENTURION study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company. Some authors including the lead author were full-time employees and minor stockholders at Eli Lilly and Company. Some authors reported receiving speaker fees and honorariums from different sources.

Source: Ashina M et al. Cephalalgia. 2021 Feb 4. doi: 10.1177/0333102421989232.

Key clinical point: Lasmiditan is effective in the treatment of an acute migraine attack and demonstrates consistency of response across multiple migraine attacks

Major finding: Lasmiditan doses of 100 and 200 mg were superior to placebo for pain freedom at 2 hours during the first attack (odds ratio [OR], 3.8 and 4.6, respectively; P less than .001) and in at least 2 of 3 attacks (OR, 3.8 and 7.2, respectively; P less than .001). The incidence of severe adverse events was similar across treatment groups.

Study details: Findings are from CENTURION, a phase 3 study that randomly assigned patients with migraine with/without aura to either of 3 treatment groups for 4 attacks: lasmiditan 200 mg (n=536), lasmiditan 100 mg (n=539), or control (n=538).

Disclosures: The CENTURION study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company. Some authors including the lead author were full-time employees and minor stockholders at Eli Lilly and Company. Some authors reported receiving speaker fees and honorariums from different sources.

Source: Ashina M et al. Cephalalgia. 2021 Feb 4. doi: 10.1177/0333102421989232.

Key clinical point: Lasmiditan is effective in the treatment of an acute migraine attack and demonstrates consistency of response across multiple migraine attacks

Major finding: Lasmiditan doses of 100 and 200 mg were superior to placebo for pain freedom at 2 hours during the first attack (odds ratio [OR], 3.8 and 4.6, respectively; P less than .001) and in at least 2 of 3 attacks (OR, 3.8 and 7.2, respectively; P less than .001). The incidence of severe adverse events was similar across treatment groups.

Study details: Findings are from CENTURION, a phase 3 study that randomly assigned patients with migraine with/without aura to either of 3 treatment groups for 4 attacks: lasmiditan 200 mg (n=536), lasmiditan 100 mg (n=539), or control (n=538).

Disclosures: The CENTURION study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company. Some authors including the lead author were full-time employees and minor stockholders at Eli Lilly and Company. Some authors reported receiving speaker fees and honorariums from different sources.

Source: Ashina M et al. Cephalalgia. 2021 Feb 4. doi: 10.1177/0333102421989232.

Acute care of migraine and cluster headaches: Mainstay treatments and emerging strategies

Acute migraine headache attacks

A recent review in the Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology by Konstantinos Spingos and colleagues (including me as the senior author) details typical and new treatments for migraine. We all know about the longstanding options, including the 7 triptans and ergots, as well as over-the-counter analgesics, which can be combined with caffeine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; and many use the 2 categories of medication that I no longer use for migraine, butalbital-containing medications, and opioids.

Now 2 gepants are available—small molecule calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonists. These medications are thought to be a useful alternative for those in whom triptans do not work or are relatively contraindicated due to coronary and cerebrovascular problems and other cardiac risk factors like obesity, smoking, lack of exercise, high cholesterol, and diabetes. Ubrogepant was approved by the FDA in 2019, and rimegepant soon followed in 2020.

- Ubrogepant: In the ACHIEVE trials, approximately 1 in 5 participants who received the 50 mg dose were pain-free at 2 hours. Moreover, nearly 40% of individuals who received it said their worst migraine symptom was resolved at 2 hours. Pain relief at 2 hours was 59%

- Rimegepant: Like ubrogepant, about 20% of trial participants who received the 75 mg melt tablet dose of rimegepant were pain-free at 2 hours. Thirty-seven percent reported that their worst migraine symptom was gone at 2 hours. Patients began to return to normal functioning in 15 minutes.

In addition to gepants, there is 1 ditan approved, which stimulates 5-HT1F receptors. Lasmiditan is the first medication in this class to be FDA-approved. It, too, is considered an alternative in patients in whom triptans are ineffective or when patients should not take a vasoconstrictor. In the most recent phase 3 study, the percentage of individuals who received lasmiditan and were pain-free at 2 hours were 28% (50 mg), 31% (100 mg) and 39% (200 mg). Relief from the migraine sufferers’ most bothersome symptom at 2 hours occurred in 41%, 44%, and 49% of patients, respectively. Lasmiditan is a Class V controlled substance. It has 18% dizziness in clinical trials. After administration, patients should not drive for 8 hours, and it should only be used once in a 24-hour period.

Non-pharmaceutical treatment options for acute migraine include nerve stimulation using electrical and magnetic stimulation devices, and behavioral approaches such as biofeedback training and mindfulness. The Nerivio device for the upper arm is controlled by a smart phone app and seems to work as well as a triptan in some patients with almost no adverse events. Just approved in February is the Relivion device which is worn like a tiara on the head and stimulates the frontal branches of the trigeminal nerve as well as the 2 occipital nerves in the back of the head.

Acute care of cluster headache attacks

In 2011, Ashkenazi and Schwedt published a comprehensive table in Headache outlining the treatment options for acute cluster headache. More recently, a review in CNS Drugs by Brandt and colleagues presented the choices with level 1 evidence for efficacy. They include:

- Sumatriptan, 6 mg subcutaneous injection, or 20 mg nasal spray

- Zolmitriptan, 5 or 10 mg nasal spray

- Oxygen, 100%, 7 to 12 liters per minute via a mask over the nose and mouth

The authors recommend subcutaneous sumatriptan 6 mg and/or high-flow oxygen at 9- to 12- liters per minute for 15 minutes. Subcutaneous sumatriptan, they note, has been shown to achieve pain relief within 15 minutes in 75% of patients who receive it. Moreover, one-third report pain freedom. Oxygen’s efficacy has long been established, and relief comes with no adverse events. As for mask type, though no significant differences have been observed in studies, patients appear to express a preference for the demand valve oxygen type, which allows a high flow rate and is dependent on the user’s breathing rate.

Lidocaine intranasally has been found to be effective when triptans or oxygen do not work, according to a review in The Lancet Neurology by Hoffman and May. The medication is dripped or sprayed into the ipsilateral nostril at a concentration of between 4% and 10%. Pain relief is typically achieved within 10 minutes. This review also reports efficacy with percutaneous vagus nerve stimulation with the gammaCore device and neurostimulation of the sphenopalatine ganglion, though the mechanisms of these approaches are poorly understood.

Evolving therapies for acute cluster headache include the aforementioned CGRP receptor-antagonists. Additionally, intranasal ketamine hydrochloride is under investigation in an open-label, proof-of-concept study; and a zolmitriptan patch is being evaluated in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Attacks of migraine occur in 12% of the adult population, 3 times more in women than men and are painful and debilitating. Cluster attacks are even more painful and occur in about 0.1% of the population, somewhat more in men. Both types of headache have a variety of effective treatment as detailed above.

Acute migraine headache attacks

A recent review in the Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology by Konstantinos Spingos and colleagues (including me as the senior author) details typical and new treatments for migraine. We all know about the longstanding options, including the 7 triptans and ergots, as well as over-the-counter analgesics, which can be combined with caffeine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; and many use the 2 categories of medication that I no longer use for migraine, butalbital-containing medications, and opioids.

Now 2 gepants are available—small molecule calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonists. These medications are thought to be a useful alternative for those in whom triptans do not work or are relatively contraindicated due to coronary and cerebrovascular problems and other cardiac risk factors like obesity, smoking, lack of exercise, high cholesterol, and diabetes. Ubrogepant was approved by the FDA in 2019, and rimegepant soon followed in 2020.

- Ubrogepant: In the ACHIEVE trials, approximately 1 in 5 participants who received the 50 mg dose were pain-free at 2 hours. Moreover, nearly 40% of individuals who received it said their worst migraine symptom was resolved at 2 hours. Pain relief at 2 hours was 59%

- Rimegepant: Like ubrogepant, about 20% of trial participants who received the 75 mg melt tablet dose of rimegepant were pain-free at 2 hours. Thirty-seven percent reported that their worst migraine symptom was gone at 2 hours. Patients began to return to normal functioning in 15 minutes.

In addition to gepants, there is 1 ditan approved, which stimulates 5-HT1F receptors. Lasmiditan is the first medication in this class to be FDA-approved. It, too, is considered an alternative in patients in whom triptans are ineffective or when patients should not take a vasoconstrictor. In the most recent phase 3 study, the percentage of individuals who received lasmiditan and were pain-free at 2 hours were 28% (50 mg), 31% (100 mg) and 39% (200 mg). Relief from the migraine sufferers’ most bothersome symptom at 2 hours occurred in 41%, 44%, and 49% of patients, respectively. Lasmiditan is a Class V controlled substance. It has 18% dizziness in clinical trials. After administration, patients should not drive for 8 hours, and it should only be used once in a 24-hour period.

Non-pharmaceutical treatment options for acute migraine include nerve stimulation using electrical and magnetic stimulation devices, and behavioral approaches such as biofeedback training and mindfulness. The Nerivio device for the upper arm is controlled by a smart phone app and seems to work as well as a triptan in some patients with almost no adverse events. Just approved in February is the Relivion device which is worn like a tiara on the head and stimulates the frontal branches of the trigeminal nerve as well as the 2 occipital nerves in the back of the head.

Acute care of cluster headache attacks

In 2011, Ashkenazi and Schwedt published a comprehensive table in Headache outlining the treatment options for acute cluster headache. More recently, a review in CNS Drugs by Brandt and colleagues presented the choices with level 1 evidence for efficacy. They include:

- Sumatriptan, 6 mg subcutaneous injection, or 20 mg nasal spray

- Zolmitriptan, 5 or 10 mg nasal spray

- Oxygen, 100%, 7 to 12 liters per minute via a mask over the nose and mouth

The authors recommend subcutaneous sumatriptan 6 mg and/or high-flow oxygen at 9- to 12- liters per minute for 15 minutes. Subcutaneous sumatriptan, they note, has been shown to achieve pain relief within 15 minutes in 75% of patients who receive it. Moreover, one-third report pain freedom. Oxygen’s efficacy has long been established, and relief comes with no adverse events. As for mask type, though no significant differences have been observed in studies, patients appear to express a preference for the demand valve oxygen type, which allows a high flow rate and is dependent on the user’s breathing rate.

Lidocaine intranasally has been found to be effective when triptans or oxygen do not work, according to a review in The Lancet Neurology by Hoffman and May. The medication is dripped or sprayed into the ipsilateral nostril at a concentration of between 4% and 10%. Pain relief is typically achieved within 10 minutes. This review also reports efficacy with percutaneous vagus nerve stimulation with the gammaCore device and neurostimulation of the sphenopalatine ganglion, though the mechanisms of these approaches are poorly understood.

Evolving therapies for acute cluster headache include the aforementioned CGRP receptor-antagonists. Additionally, intranasal ketamine hydrochloride is under investigation in an open-label, proof-of-concept study; and a zolmitriptan patch is being evaluated in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Attacks of migraine occur in 12% of the adult population, 3 times more in women than men and are painful and debilitating. Cluster attacks are even more painful and occur in about 0.1% of the population, somewhat more in men. Both types of headache have a variety of effective treatment as detailed above.

Acute migraine headache attacks

A recent review in the Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology by Konstantinos Spingos and colleagues (including me as the senior author) details typical and new treatments for migraine. We all know about the longstanding options, including the 7 triptans and ergots, as well as over-the-counter analgesics, which can be combined with caffeine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; and many use the 2 categories of medication that I no longer use for migraine, butalbital-containing medications, and opioids.

Now 2 gepants are available—small molecule calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonists. These medications are thought to be a useful alternative for those in whom triptans do not work or are relatively contraindicated due to coronary and cerebrovascular problems and other cardiac risk factors like obesity, smoking, lack of exercise, high cholesterol, and diabetes. Ubrogepant was approved by the FDA in 2019, and rimegepant soon followed in 2020.

- Ubrogepant: In the ACHIEVE trials, approximately 1 in 5 participants who received the 50 mg dose were pain-free at 2 hours. Moreover, nearly 40% of individuals who received it said their worst migraine symptom was resolved at 2 hours. Pain relief at 2 hours was 59%

- Rimegepant: Like ubrogepant, about 20% of trial participants who received the 75 mg melt tablet dose of rimegepant were pain-free at 2 hours. Thirty-seven percent reported that their worst migraine symptom was gone at 2 hours. Patients began to return to normal functioning in 15 minutes.

In addition to gepants, there is 1 ditan approved, which stimulates 5-HT1F receptors. Lasmiditan is the first medication in this class to be FDA-approved. It, too, is considered an alternative in patients in whom triptans are ineffective or when patients should not take a vasoconstrictor. In the most recent phase 3 study, the percentage of individuals who received lasmiditan and were pain-free at 2 hours were 28% (50 mg), 31% (100 mg) and 39% (200 mg). Relief from the migraine sufferers’ most bothersome symptom at 2 hours occurred in 41%, 44%, and 49% of patients, respectively. Lasmiditan is a Class V controlled substance. It has 18% dizziness in clinical trials. After administration, patients should not drive for 8 hours, and it should only be used once in a 24-hour period.

Non-pharmaceutical treatment options for acute migraine include nerve stimulation using electrical and magnetic stimulation devices, and behavioral approaches such as biofeedback training and mindfulness. The Nerivio device for the upper arm is controlled by a smart phone app and seems to work as well as a triptan in some patients with almost no adverse events. Just approved in February is the Relivion device which is worn like a tiara on the head and stimulates the frontal branches of the trigeminal nerve as well as the 2 occipital nerves in the back of the head.

Acute care of cluster headache attacks

In 2011, Ashkenazi and Schwedt published a comprehensive table in Headache outlining the treatment options for acute cluster headache. More recently, a review in CNS Drugs by Brandt and colleagues presented the choices with level 1 evidence for efficacy. They include:

- Sumatriptan, 6 mg subcutaneous injection, or 20 mg nasal spray

- Zolmitriptan, 5 or 10 mg nasal spray

- Oxygen, 100%, 7 to 12 liters per minute via a mask over the nose and mouth

The authors recommend subcutaneous sumatriptan 6 mg and/or high-flow oxygen at 9- to 12- liters per minute for 15 minutes. Subcutaneous sumatriptan, they note, has been shown to achieve pain relief within 15 minutes in 75% of patients who receive it. Moreover, one-third report pain freedom. Oxygen’s efficacy has long been established, and relief comes with no adverse events. As for mask type, though no significant differences have been observed in studies, patients appear to express a preference for the demand valve oxygen type, which allows a high flow rate and is dependent on the user’s breathing rate.

Lidocaine intranasally has been found to be effective when triptans or oxygen do not work, according to a review in The Lancet Neurology by Hoffman and May. The medication is dripped or sprayed into the ipsilateral nostril at a concentration of between 4% and 10%. Pain relief is typically achieved within 10 minutes. This review also reports efficacy with percutaneous vagus nerve stimulation with the gammaCore device and neurostimulation of the sphenopalatine ganglion, though the mechanisms of these approaches are poorly understood.

Evolving therapies for acute cluster headache include the aforementioned CGRP receptor-antagonists. Additionally, intranasal ketamine hydrochloride is under investigation in an open-label, proof-of-concept study; and a zolmitriptan patch is being evaluated in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Attacks of migraine occur in 12% of the adult population, 3 times more in women than men and are painful and debilitating. Cluster attacks are even more painful and occur in about 0.1% of the population, somewhat more in men. Both types of headache have a variety of effective treatment as detailed above.

Neurologic disorders ubiquitous and rising in the U.S.

, according to new findings derived from the 2017 Global Burden of Disease study.

The authors of the analysis, led by Valery Feigin, MD, PhD, of New Zealand’s National Institute for Stroke and Applied Neurosciences, and published in the February 2021 issue of JAMA Neurology, looked at prevalence, incidence, mortality, and disability-adjusted life years for 14 neurological disorders across 50 states between 1990 and 2017. The diseases included in the analysis were stroke, Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, motor neuron disease, headaches, traumatic brain injury, spinal cord injuries, brain and other nervous system cancers, meningitis, encephalitis, and tetanus.

Tracking the burden of neurologic diseases

Dr. Feigin and colleagues estimated that a full 60% of the U.S. population lives with one or more of these disorders, a figure much greater than previous estimates for neurological disease burden nationwide. Tension-type headache and migraine were the most prevalent in the analysis by Dr. Feigin and colleagues. During the study period, they found, prevalence, incidence, and disability burden of nearly all the included disorders increased, with the exception of brain and spinal cord injuries, meningitis, and encephalitis.

The researchers attributed most of the rise in noncommunicable neurological diseases to population aging. An age-standardized analysis found trends for stroke and Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias to be declining or flat. Age-standardized stroke incidence dropped by 16% from 1990 to 2017, while stroke mortality declined by nearly a third, and stroke disability by a quarter. Age-standardized incidence of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias dropped by 12%, and their prevalence by 13%, during the study period, though dementia mortality and disability were seen increasing.

The authors surmised that the age-standardized declines in stroke and dementias could reflect that “primary prevention of these disorders are beginning to show an influence.” With dementia, which is linked to cognitive reserve and education, “improving educational levels of cohort reaching the age groups at greatest risk of disease may also be contributing to a modest decline over time,” Dr. Feigin and his colleagues wrote.

Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis, meanwhile, were both seen rising in incidence, prevalence, and disability adjusted life years (DALYs) even with age-standardized figures. The United States saw comparatively more disability in 2017 from dementias, Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, motor neuron disease, and headache disorders, which together comprised 6.7% of DALYs, compared with 4.4% globally; these also accounted for a higher share of mortality in the U.S. than worldwide. The authors attributed at least some of the difference to better case ascertainment in the U.S.

Regional variations

The researchers also reported variations in disease burden by state and region. While previous studies have identified a “stroke belt” concentrated in North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia, the new findings point to stroke disability highest in Alabama, Arkansas, and Mississippi, and mortality highest in Alabama, Mississippi, and South Carolina. The researchers noted increases in dementia mortality in these states, “likely attributable to the reciprocal association between stroke and dementia.”

Northern states saw higher burdens of multiple sclerosis compared with the rest of the country, while eastern states had higher rates of Parkinson’s disease.

Such regional and state-by state variations, Dr. Feigin and colleagues wrote in their analysis, “may be associated with differences in the case ascertainment, as well as access to health care; racial/ethnic, genetic, and socioeconomic diversity; quality and comprehensiveness of preventive strategies; and risk factor distribution.”

The researchers noted as a limitation of their study that the 14 diseases captured were not an exhaustive list of neurological conditions; chronic lower back pain, a condition included in a previous major study of the burden of neurological disease in the United States, was omitted, as were restless legs syndrome and peripheral neuropathy. The researchers cited changes to coding practice in the U.S. and accuracy of medical claims data as potential limitations of their analysis. The Global Burden of Disease study is funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and several of Dr. Feigin’s coauthors reported financial relationships with industry.

Time to adjust the stroke belt?

Amelia Boehme, PhD, a stroke epidemiologist at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health in New York, said in an interview that the current study added to recent findings showing surprising local variability in stroke prevalence, incidence, and mortality. “What we had always conceptually thought of as the ‘stroke belt’ isn’t necessarily the case,” Dr. Boehme said, but is rather subject to local, county-by-county variations. “Looking at the data here in conjunction with what previous authors have found, it raises some questions as to whether or not state-level data is giving a completely accurate picture, and whether we need to start looking at the county level and adjust for populations and age.” Importantly, Dr. Boehme said, data collected in the Global Burden of Disease study tends to be exceptionally rigorous and systematic, adding weight to Dr. Feigin and colleagues’ suggestions that prevention efforts may be making a dent in stroke and dementia.

“More data is always needed before we start to say we’re seeing things change,” Dr. Boehme noted. “But any glimmer of optimism is welcome, especially with regard to interventions that have been put in place, to allow us to build on those interventions.”

Dr. Boehme disclosed no financial conflicts of interest.

, according to new findings derived from the 2017 Global Burden of Disease study.

The authors of the analysis, led by Valery Feigin, MD, PhD, of New Zealand’s National Institute for Stroke and Applied Neurosciences, and published in the February 2021 issue of JAMA Neurology, looked at prevalence, incidence, mortality, and disability-adjusted life years for 14 neurological disorders across 50 states between 1990 and 2017. The diseases included in the analysis were stroke, Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, motor neuron disease, headaches, traumatic brain injury, spinal cord injuries, brain and other nervous system cancers, meningitis, encephalitis, and tetanus.

Tracking the burden of neurologic diseases

Dr. Feigin and colleagues estimated that a full 60% of the U.S. population lives with one or more of these disorders, a figure much greater than previous estimates for neurological disease burden nationwide. Tension-type headache and migraine were the most prevalent in the analysis by Dr. Feigin and colleagues. During the study period, they found, prevalence, incidence, and disability burden of nearly all the included disorders increased, with the exception of brain and spinal cord injuries, meningitis, and encephalitis.

The researchers attributed most of the rise in noncommunicable neurological diseases to population aging. An age-standardized analysis found trends for stroke and Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias to be declining or flat. Age-standardized stroke incidence dropped by 16% from 1990 to 2017, while stroke mortality declined by nearly a third, and stroke disability by a quarter. Age-standardized incidence of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias dropped by 12%, and their prevalence by 13%, during the study period, though dementia mortality and disability were seen increasing.

The authors surmised that the age-standardized declines in stroke and dementias could reflect that “primary prevention of these disorders are beginning to show an influence.” With dementia, which is linked to cognitive reserve and education, “improving educational levels of cohort reaching the age groups at greatest risk of disease may also be contributing to a modest decline over time,” Dr. Feigin and his colleagues wrote.

Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis, meanwhile, were both seen rising in incidence, prevalence, and disability adjusted life years (DALYs) even with age-standardized figures. The United States saw comparatively more disability in 2017 from dementias, Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, motor neuron disease, and headache disorders, which together comprised 6.7% of DALYs, compared with 4.4% globally; these also accounted for a higher share of mortality in the U.S. than worldwide. The authors attributed at least some of the difference to better case ascertainment in the U.S.

Regional variations

The researchers also reported variations in disease burden by state and region. While previous studies have identified a “stroke belt” concentrated in North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia, the new findings point to stroke disability highest in Alabama, Arkansas, and Mississippi, and mortality highest in Alabama, Mississippi, and South Carolina. The researchers noted increases in dementia mortality in these states, “likely attributable to the reciprocal association between stroke and dementia.”

Northern states saw higher burdens of multiple sclerosis compared with the rest of the country, while eastern states had higher rates of Parkinson’s disease.

Such regional and state-by state variations, Dr. Feigin and colleagues wrote in their analysis, “may be associated with differences in the case ascertainment, as well as access to health care; racial/ethnic, genetic, and socioeconomic diversity; quality and comprehensiveness of preventive strategies; and risk factor distribution.”

The researchers noted as a limitation of their study that the 14 diseases captured were not an exhaustive list of neurological conditions; chronic lower back pain, a condition included in a previous major study of the burden of neurological disease in the United States, was omitted, as were restless legs syndrome and peripheral neuropathy. The researchers cited changes to coding practice in the U.S. and accuracy of medical claims data as potential limitations of their analysis. The Global Burden of Disease study is funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and several of Dr. Feigin’s coauthors reported financial relationships with industry.

Time to adjust the stroke belt?

Amelia Boehme, PhD, a stroke epidemiologist at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health in New York, said in an interview that the current study added to recent findings showing surprising local variability in stroke prevalence, incidence, and mortality. “What we had always conceptually thought of as the ‘stroke belt’ isn’t necessarily the case,” Dr. Boehme said, but is rather subject to local, county-by-county variations. “Looking at the data here in conjunction with what previous authors have found, it raises some questions as to whether or not state-level data is giving a completely accurate picture, and whether we need to start looking at the county level and adjust for populations and age.” Importantly, Dr. Boehme said, data collected in the Global Burden of Disease study tends to be exceptionally rigorous and systematic, adding weight to Dr. Feigin and colleagues’ suggestions that prevention efforts may be making a dent in stroke and dementia.

“More data is always needed before we start to say we’re seeing things change,” Dr. Boehme noted. “But any glimmer of optimism is welcome, especially with regard to interventions that have been put in place, to allow us to build on those interventions.”

Dr. Boehme disclosed no financial conflicts of interest.

, according to new findings derived from the 2017 Global Burden of Disease study.

The authors of the analysis, led by Valery Feigin, MD, PhD, of New Zealand’s National Institute for Stroke and Applied Neurosciences, and published in the February 2021 issue of JAMA Neurology, looked at prevalence, incidence, mortality, and disability-adjusted life years for 14 neurological disorders across 50 states between 1990 and 2017. The diseases included in the analysis were stroke, Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, motor neuron disease, headaches, traumatic brain injury, spinal cord injuries, brain and other nervous system cancers, meningitis, encephalitis, and tetanus.

Tracking the burden of neurologic diseases

Dr. Feigin and colleagues estimated that a full 60% of the U.S. population lives with one or more of these disorders, a figure much greater than previous estimates for neurological disease burden nationwide. Tension-type headache and migraine were the most prevalent in the analysis by Dr. Feigin and colleagues. During the study period, they found, prevalence, incidence, and disability burden of nearly all the included disorders increased, with the exception of brain and spinal cord injuries, meningitis, and encephalitis.

The researchers attributed most of the rise in noncommunicable neurological diseases to population aging. An age-standardized analysis found trends for stroke and Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias to be declining or flat. Age-standardized stroke incidence dropped by 16% from 1990 to 2017, while stroke mortality declined by nearly a third, and stroke disability by a quarter. Age-standardized incidence of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias dropped by 12%, and their prevalence by 13%, during the study period, though dementia mortality and disability were seen increasing.

The authors surmised that the age-standardized declines in stroke and dementias could reflect that “primary prevention of these disorders are beginning to show an influence.” With dementia, which is linked to cognitive reserve and education, “improving educational levels of cohort reaching the age groups at greatest risk of disease may also be contributing to a modest decline over time,” Dr. Feigin and his colleagues wrote.

Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis, meanwhile, were both seen rising in incidence, prevalence, and disability adjusted life years (DALYs) even with age-standardized figures. The United States saw comparatively more disability in 2017 from dementias, Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, motor neuron disease, and headache disorders, which together comprised 6.7% of DALYs, compared with 4.4% globally; these also accounted for a higher share of mortality in the U.S. than worldwide. The authors attributed at least some of the difference to better case ascertainment in the U.S.

Regional variations

The researchers also reported variations in disease burden by state and region. While previous studies have identified a “stroke belt” concentrated in North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia, the new findings point to stroke disability highest in Alabama, Arkansas, and Mississippi, and mortality highest in Alabama, Mississippi, and South Carolina. The researchers noted increases in dementia mortality in these states, “likely attributable to the reciprocal association between stroke and dementia.”

Northern states saw higher burdens of multiple sclerosis compared with the rest of the country, while eastern states had higher rates of Parkinson’s disease.

Such regional and state-by state variations, Dr. Feigin and colleagues wrote in their analysis, “may be associated with differences in the case ascertainment, as well as access to health care; racial/ethnic, genetic, and socioeconomic diversity; quality and comprehensiveness of preventive strategies; and risk factor distribution.”

The researchers noted as a limitation of their study that the 14 diseases captured were not an exhaustive list of neurological conditions; chronic lower back pain, a condition included in a previous major study of the burden of neurological disease in the United States, was omitted, as were restless legs syndrome and peripheral neuropathy. The researchers cited changes to coding practice in the U.S. and accuracy of medical claims data as potential limitations of their analysis. The Global Burden of Disease study is funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and several of Dr. Feigin’s coauthors reported financial relationships with industry.

Time to adjust the stroke belt?

Amelia Boehme, PhD, a stroke epidemiologist at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health in New York, said in an interview that the current study added to recent findings showing surprising local variability in stroke prevalence, incidence, and mortality. “What we had always conceptually thought of as the ‘stroke belt’ isn’t necessarily the case,” Dr. Boehme said, but is rather subject to local, county-by-county variations. “Looking at the data here in conjunction with what previous authors have found, it raises some questions as to whether or not state-level data is giving a completely accurate picture, and whether we need to start looking at the county level and adjust for populations and age.” Importantly, Dr. Boehme said, data collected in the Global Burden of Disease study tends to be exceptionally rigorous and systematic, adding weight to Dr. Feigin and colleagues’ suggestions that prevention efforts may be making a dent in stroke and dementia.

“More data is always needed before we start to say we’re seeing things change,” Dr. Boehme noted. “But any glimmer of optimism is welcome, especially with regard to interventions that have been put in place, to allow us to build on those interventions.”

Dr. Boehme disclosed no financial conflicts of interest.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Identifying Acute Migraine Triggers

To read a digital version of the print supplement, click here.

To gain a full understanding of the challenges faced by neurologists, headache specialists, and other clinicians when managing triggers that prompt migraine headache attacks, consider the case of Lola H, a 35-year-old woman with a history of recurrent headaches that was diagnosed 12 months earlier as migraine without aura. Lola is taking oral sumatriptan, 100 mg, for acute migraine episodes, which she reports experiencing 3 or 4 times a month. She also has up to 3 headaches a week that are less severe. Lola’s insurance carrier limits the number of sumatriptan tablets covered in a month, forcing her use the medication only when she has severe headaches. However, the rationing strategy adds stress to her life that could be contributing to additional headache episodes.

Lola raised this issue during a recent visit with her neurologist, at which time she also presented a lengthy list of things she felt were triggering her attacks: stress, her menstrual cycle, chocolate, the odor of gasoline, and the weather, among other potential causes. Regarding the weather, she reported experiencing headaches—sometimes severe—whenever barometric pressure drops. Lola told her clinician that she believes she has gained control of 2 triggers—chocolate and gasoline fumes—through avoidance. She no longer consumes chocolate and other sweets and relies on family members and friends to fill her automobile fuel tank. However, Lola said she cannot control other triggers and needs her clinician’s help. She insists on leaving the appointment with answers she feels satisfied with. More than anything, she wants to feel secure that she has enough medication to meet her needs. (We will reveal how Lola fared later in this article.)

Heterogeneity of triggers: A daunting challenge

Lola’s circumstances are not uncommon among the nearly 40 million migraine sufferers in the United States.1 For clinicians seeking to better understand how potential triggers cause migraine attacks, it is important to appreciate the fine lines that exist between (1) perceived triggers, (2) their apparent frequency and strength, (3) patients’ efforts to control these factors, and (4) the distinction between real migraine triggers and premonitory symptoms. Moreover, recognizing how each of these 4 issues influence the patient’s experience enables the clinician to optimally manage individuals who experience migraine headache.

A diverse array of potential stimuli

Perhaps the most daunting challenge when trying to uncover what is triggering Lola’s and other migraine patients’ headaches is the realization that triggers and perceived triggers comprise a diverse array of potential stimuli. A meta-analysis of 85 studies conducted over a 60-year period and involving more than 27,000 participants revealed 420 unique headache triggers categorized to 1 of 15 categories.2 Characterizing these triggers as vastly heterogenous is an understatement, considering that they include factors such as raising the arms overhead, sneezing, abstaining from coffee, using a low pillow, weekend sleep habits, use of shower gels, relaxing after stressful events, bus journeys, road stripes, and more.2 The authors of the meta-analysis note that the variability observed likely is because of methodology differences among the studies included in their analysis. For this reason, the authors advised caution in interpreting the results.2

Nevertheless, the investigators concluded that (1) most of those who experience frequent headaches—including migraine sufferers—believe they have at least 1 trigger, and (2) stress is the trigger most frequently cited by patients, followed by sleep and environmental triggers.2

Perceived differences in trigger frequency and strength

Heterogeneity extends beyond the triggers and perceived triggers; incidence and strength also can vary greatly. In a cross-sectional observational study, 300 headache sufferers were asked to rate 33 triggers by frequency and potency.3 Triggers that were perceived to be encountered most days per month were air conditioning and caffeine (both 30 days). Red wine was perceived to be encountered least frequently (0 days). Importantly, interperson variability for frequency of encounter was significant—most ranges for each trigger spanned

15 days or more.3

Triggers that were perceived to increase the chance of a headache were stress (75%), missing a meal, and dehydration (both 60%). Nuts and salty food were least perceived to increase the likelihood of a headache (both 0%). Similar to frequency, perceptions about trigger strengths varied widely, with most ranges spreading by more than 50% for each trigger.3

The authors noted that the heterogeneity seen in frequency of encounters with triggers remained even when 2 patients had matching perceptions about the importance of the trigger in precipitating a headache. The fact that this was observed for nearly every perceived trigger is an important aspect of understanding trigger frequency at the patient-care level.3 Additionally, most headache sufferers do not believe that triggers are simply present or absent. Rather, they have diverse beliefs about the strength of perceived triggers.3 These broad differences among patients make it difficult to predict how an individual headache sufferer will rate triggers.3

The patient’s trigger belief system

Layered onto this challenge is the observation that many migraine sufferers use the so-called trigger belief system to create a safe and controlled environment to stave off headache attacks. Indeed, perception often dictates how headache triggers are experienced, and this adds to the complexity of managing these patients. This is borne out in 2 studies. One, involving more than 200 individuals, revealed that perceived control over and impact of headaches were related to headache severity.4 Another trial involving more than 300 patients seeking treatment for headache showed that participants who were confident they could avoid and better manage their headaches also believed that they could control factors impacting their headaches. Although this led to the use of positive coping strategies, it also triggered more anxiety.5

Trigger avoidance can also lead to reduced quality of life. Consider, for example, physical activity, which is recommended to prevent and manage migraine: As many as 8 in 10 migraine sufferers avoid physical activity because they fear triggering an episode.6 In a recent study, investigators examined the potential correlation between anxiety sensitivity and physical activity avoidance among 100 women with migraine. Participants completed an anonymous survey about migraine and avoiding physical activity. The survey included a tool that measured anxiety sensitivity. Migraine attacks in the previous 30 days were self-reported.6 Higher anxiety scores were linked with more frequent physical activity avoidance. Participants who cited physical concerns were nearly 8 times more likely to avoid vigorous physical activity. Those who mentioned cognitive concerns were more than 5 times more likely to avoid moderate physical activity.6 The authors noted that even though avoiding triggers often is recommended, in some situations it can lead to more migraines because of increased anxiety. For this reason, although avoidance is probably best for certain triggers that have true biologic onset mechanisms, triggers that work through anticipatory anxiety or fearful expectations might best be handled via gradual exposure and desensitization.6

Distinguishing between real triggers and premonitory symptoms

Once clinicians gain an understanding of these factors, they may consider themselves adequately prepared to optimally manage migraine sufferers. Yet, there is one more factor to consider: premonitory symptoms. Separating premonitory symptoms from actual migraine triggers gets the clinician closer to optimal management. Yet, it is not always easy to make the distinction.

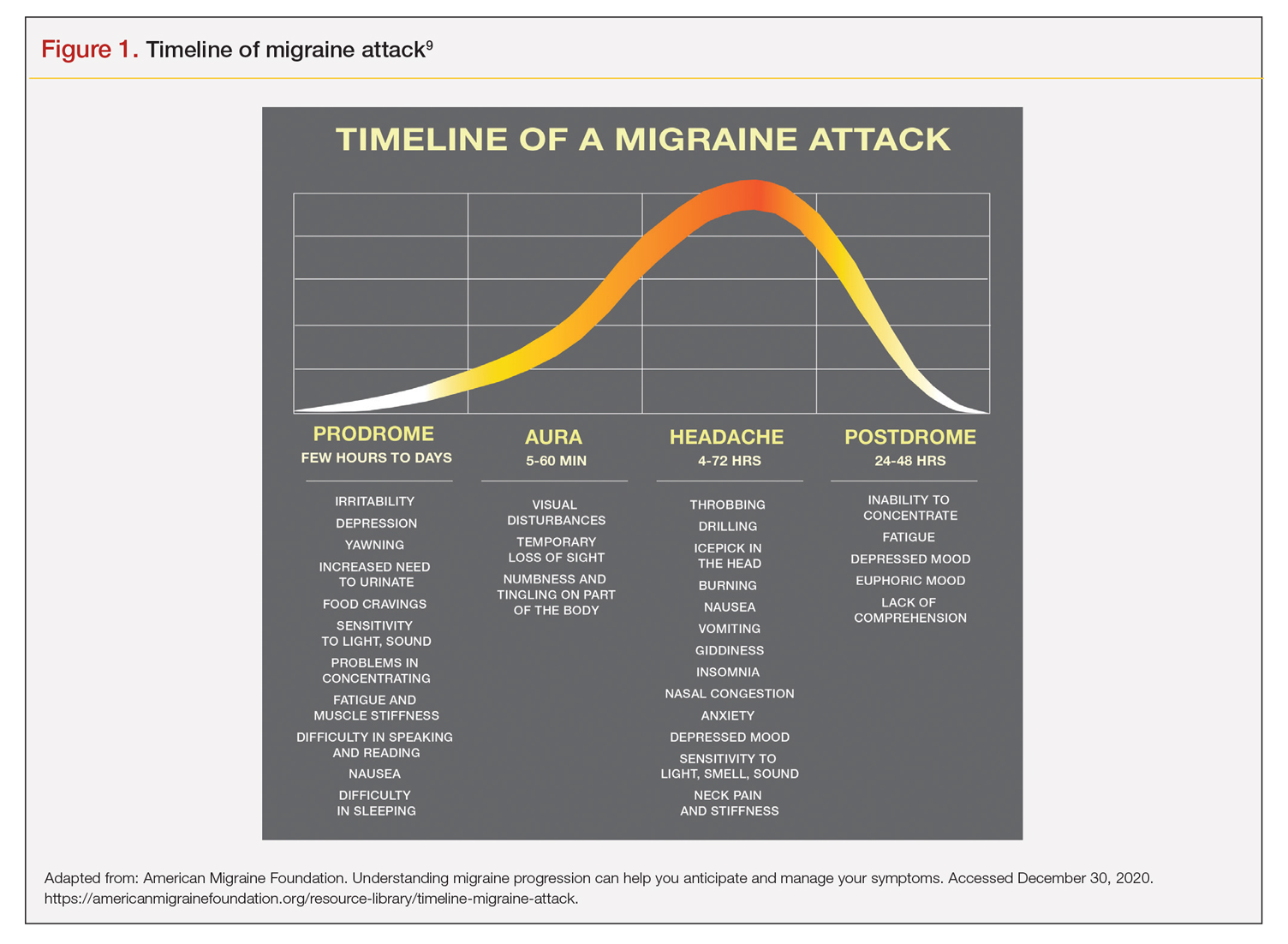

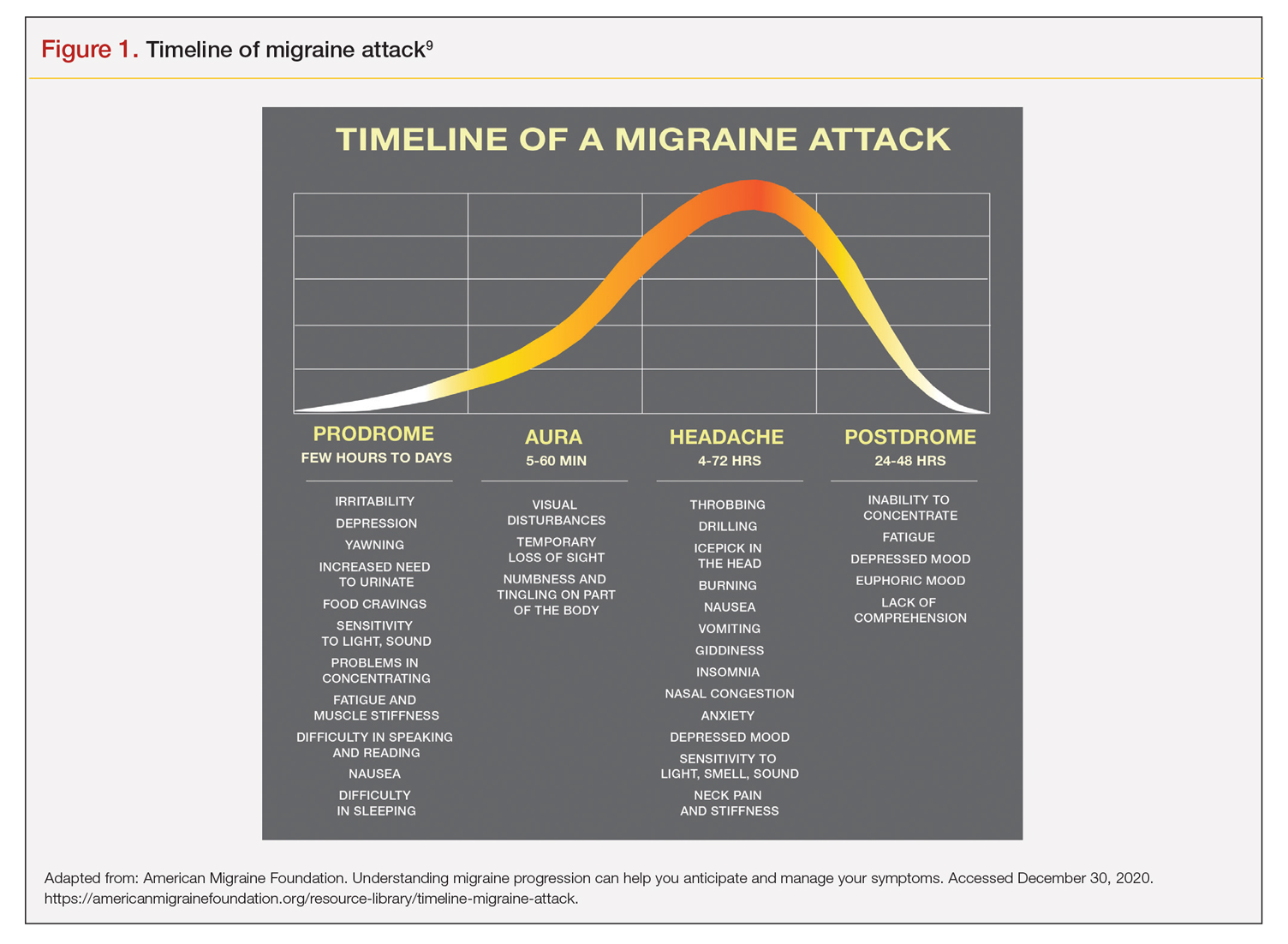

Premonitory symptoms typically present 2 to 48 hours (or more) before migraine headache onset. Symptoms include changes in mood and activity, irritability, fatigue, food cravings, repetitive yawning, stiff neck, and photophobia. Because these symptoms can continue even past the premonitory stage, they often can be misinterpreted as actual migraine triggers.7 Premonitory symptoms have been found to accompany 30% to 80% of migraine attacks. Signs that often are confused with actual migraine triggers include neck pain, photophobia, and food cravings.8

Timing of symptoms: Potential clues

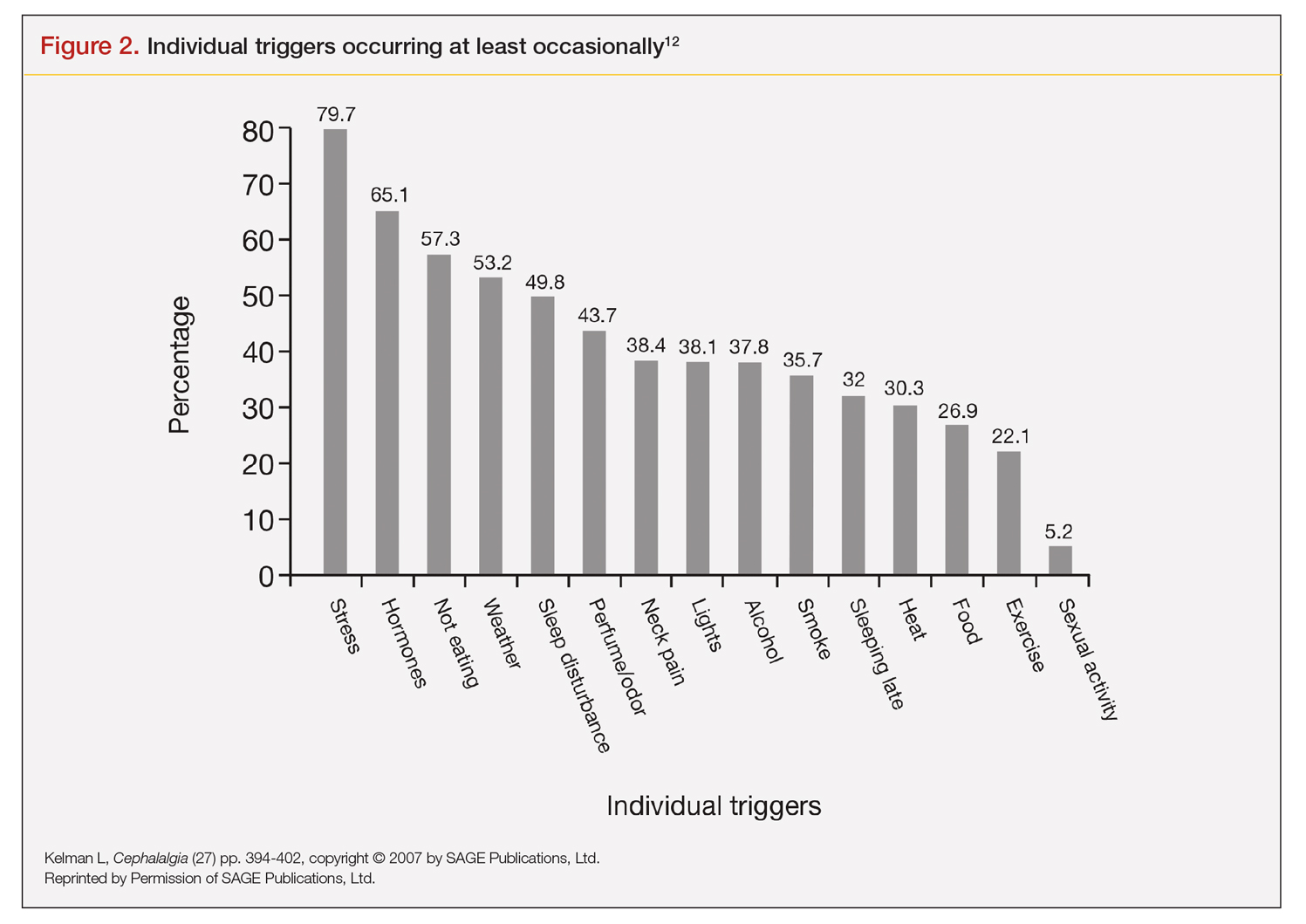

It is critical to understand the interval between a symptom and migraine onset, which can help determine whether it is an actual trigger, premonitory symptom, or other manifestation. For this, it helps to review the timeline of a migraine attack. The 4 phases of a migraine attack—premonitory/prodrome, aura, headache, and postdrome—are well known. According to the American Migraine Foundation, the 4 phases are marked by specific symptoms that typically—but not always—occur along a general timeline (Figure 1).9

Although this symptom timeline can help guide clinicians and migraine sufferers, it is important to understand that these phases do not always occur linearly, and there often is significant overlap, which can mislead both the clinician and patient.7

Common triggers

Stress: Stress is the most frequently self-reported migraine trigger, and numerous studies show a link between stress and migraine. However, retrospective and prospective diary studies have not been able to confirm a link between stressful days and acute migraine attacks. Moreover, although 1 study demonstrated that migraines were less likely to occur on holidays or days off, relaxation did not play a role. Fatigue was more common premigraine than mental exhaustion or insomnia, leading investigators to surmise it is a premonitory symptom and not a migraine cause.8 Further confounding is the finding that reduced stress from one day to the next is linked with migraine onset the next day, making it a possible predictor of a migraine attack because of the so-called letdown effect.10

Menstruation: Menstruation appears to be the most common migraine trigger in women. A large 3-month study showed an increase of migraine prevalence and persistence up to 96%. Additionally, diary studies demonstrate menstruation as a trigger, and in a population-based trial, more than half of female migraine sufferers reported an increased rate

of migraine. However, only 4% actually had a migraine during menstruation.8,11

Diet: Studies that seek to find a link between specific foods and migraine are open to question because they do not have a placebo component, and it is difficult to tell the difference between premonitory food cravings and actual triggers. Moreover, in most patients food appears to be 1 of several contributors to migraine headache, and not the only factor.8 Fasting is among the most studied and consistent migraine triggers and seems to be more common during longer fasts. Dehydration is not thought to be a cause; rather, it could be because of hypoglycemia.8 A trial involving more than 3000 women revealed that those with migraine had a lower diet quality than their counterparts who did not experience migraine. Other smaller studies show benefit from low-fat vegan and ketogenic diets. Also, patients with irritable bowel syndrome and migraine might benefit from eliminating such foods that cause irritation to improve both migraine frequency and bowel symptoms.8

Weather: A few small studies have sought to evaluate the link between weather and migraines. One involving 77 individuals with migraine showed that slightly more than half were sensitive to at least 1 weather factor (i.e., barometric changes, lightning, temperature, and precipitation). Another involving 238 participants demonstrated a nonstatistically significant trend toward increased frequency of migraine attacks on days with high pressure, low wind speed, and increased sunshine, but they called the correlation questionable. A study of 90 individuals found lightning to be an independent risk factor for migraine.8

Sensory stimuli: Although visual, aural, olfactory, and other sensory stimuli have been shown to cause migraine in susceptible individuals and worsen migraine intensity, it is difficult to determine if these are true triggers or premonitory symptoms. Indeed, the discomfort thresholds of various sensory stimuli are lower in migraine sufferers.8 Odors are the most commonly reported triggers among all sensory stimuli. In 1 study, 7 in every 10 migraine sufferers reported that odors triggered their attack. Common offenders include perfumes, paint, gasoline, bleach, and rancid odors. Smoke and exhaust fumes were also found to be problematic.8

Best evidence on migraine triggers

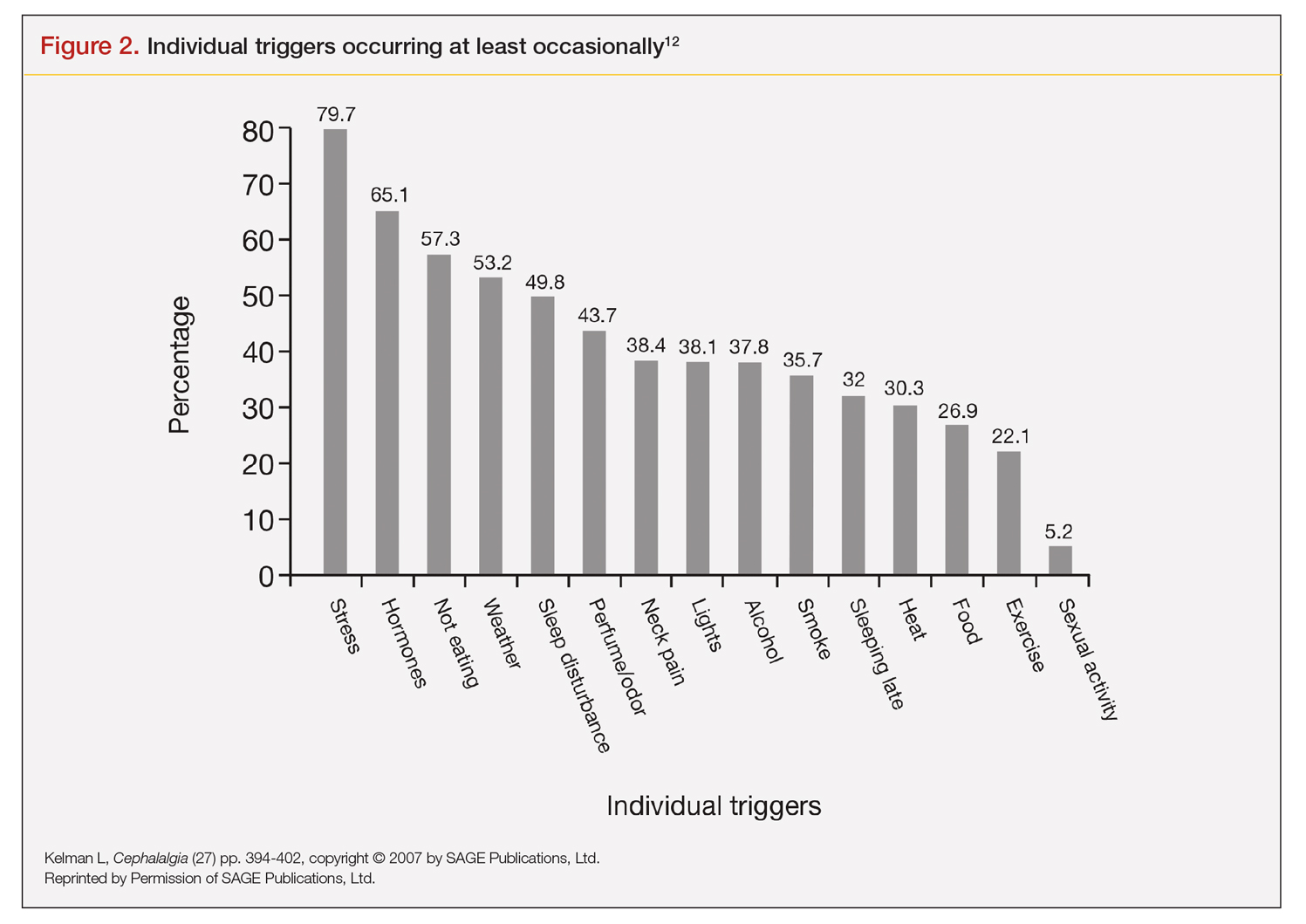

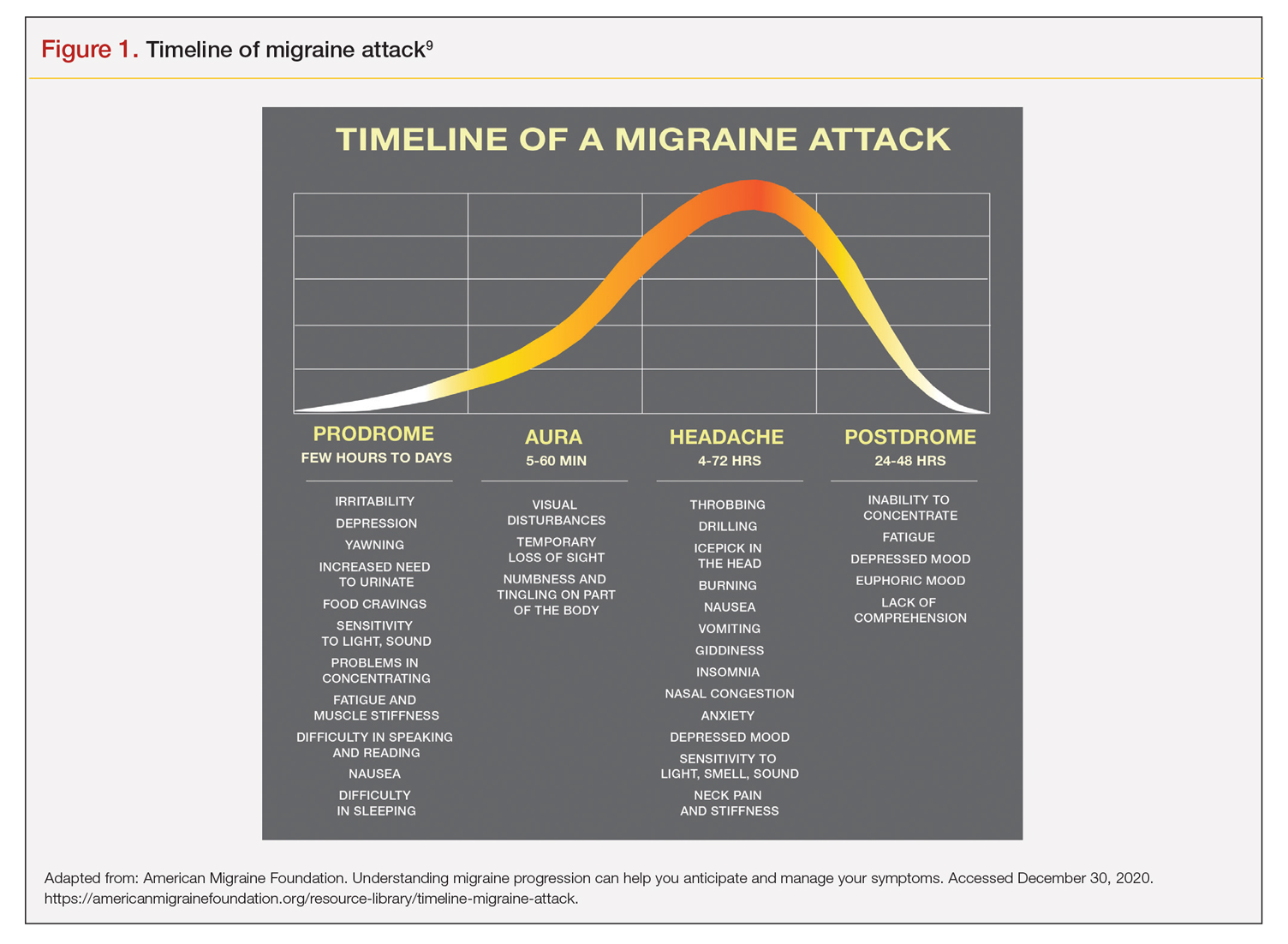

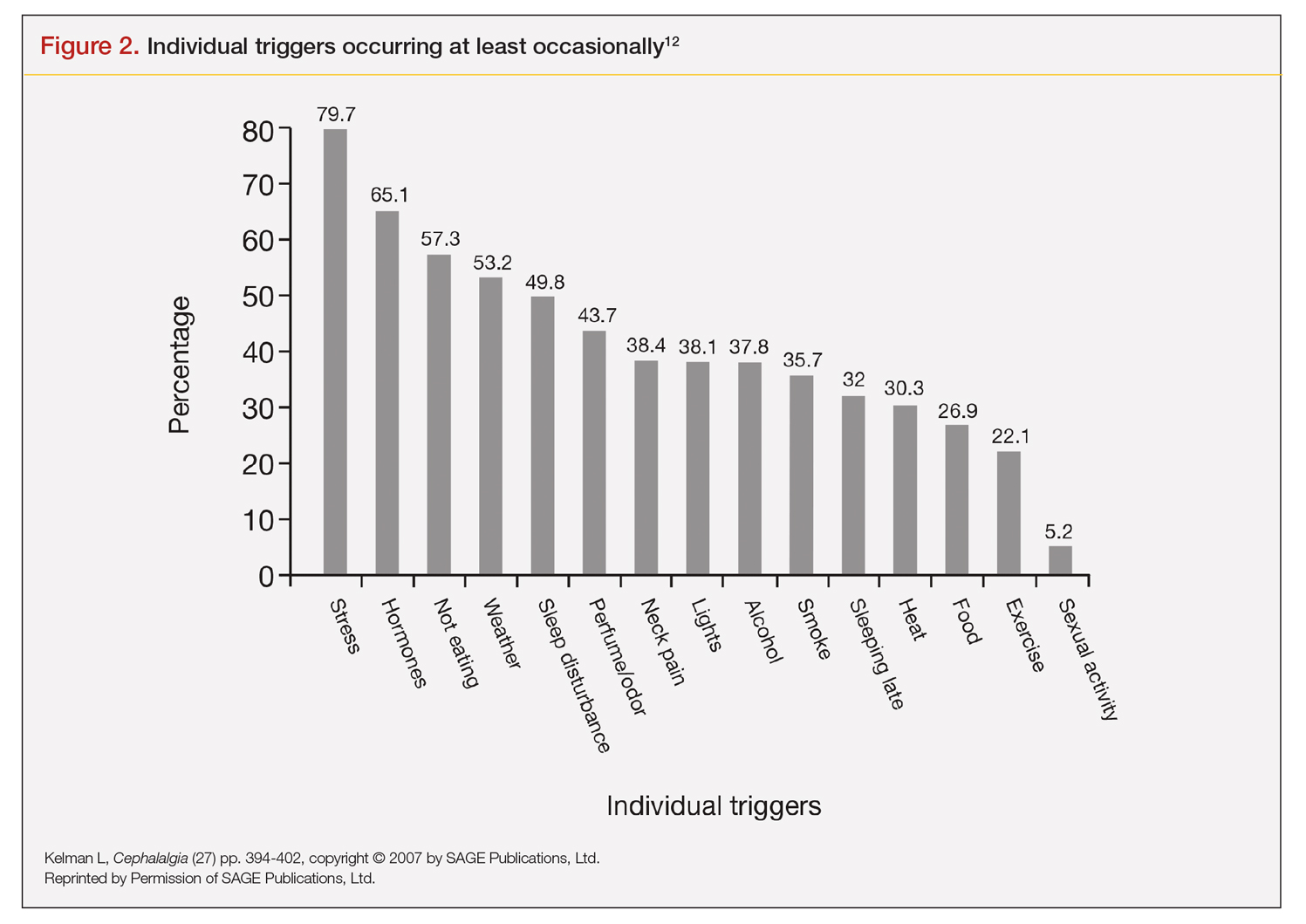

A large retrospective survey looked at acute migraine trigger factors in 1750 individuals treated in a clinical practice. A detailed headache evaluation was conducted that included neurologic history, structured headache interview, and a neurologic exam.12 More than three-fourths of patients experienced triggers. Approximately 6 in every 10 patients had between 4 and 9 triggers. Nearly one-fourth experienced 1 to 3 triggers.12 As shown in Figure 2, the 5 triggers that occurred occasionally in at least half of patients were stress (80%), hormone (65%), fasting (57%), weather (53%), and sleep disturbance (50%). The most common triggers, occurring very frequently, were hormone (33%) and stress (26%).12

Trials that use randomized and blinded exposure to possible triggers can—at face value—appear most useful. Potent compounds such as glyceryl trinitrite, prostaglandin I2 and E2, calcitonin-gene related peptide, and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide have been shown to be dependable triggers in the experimental setting. However, trial designs that do not closely mimic real-world experience lack usefulness in clinical practice. Moreover, studies of low intensity migraine triggers that are common in the real world—chocolate and aspartame, for instance—have produced mixed results.13 So-called N-of-1 studies—in which a single patient is repeatedly exposed in blinded fashion to a trigger or placebo—might be the best way to uncover actual triggers. However, migraine sufferers are, understandably, not interested in deliberately inducing an attack.13

This leaves results of diary studies as the most reflective of clinical practice. These evaluations limit the chance of bias that retrospective studies could carry and often provide a significant amount of real-world data that can be used to test hypotheses. Moreover, the advent of smartphone technology enables researchers to capture data in real time, which can help distinguish premonitory symptoms from actual triggers.13 A high-quality paper diary study (PAMINA) involving 327 individuals showed strong evidence that a migraine was likely to occur with the following factors: menstruation, muscle tension/neck pain, psychic tension, and sunshine that lasted 3 or more hours per day.14

Diary studies are also able to assess the ability of migraine sufferers to predict a headache. In an evaluation that used an electronic diary design, researchers looked at self-prediction through use of a single question asked daily: “How likely are you to have a headache today?” When participants reported at the beginning of a particular day that headache was “almost certain,” actual headache occurred more than 90% of the time on that day.13

Leveraging best evidence into best practices

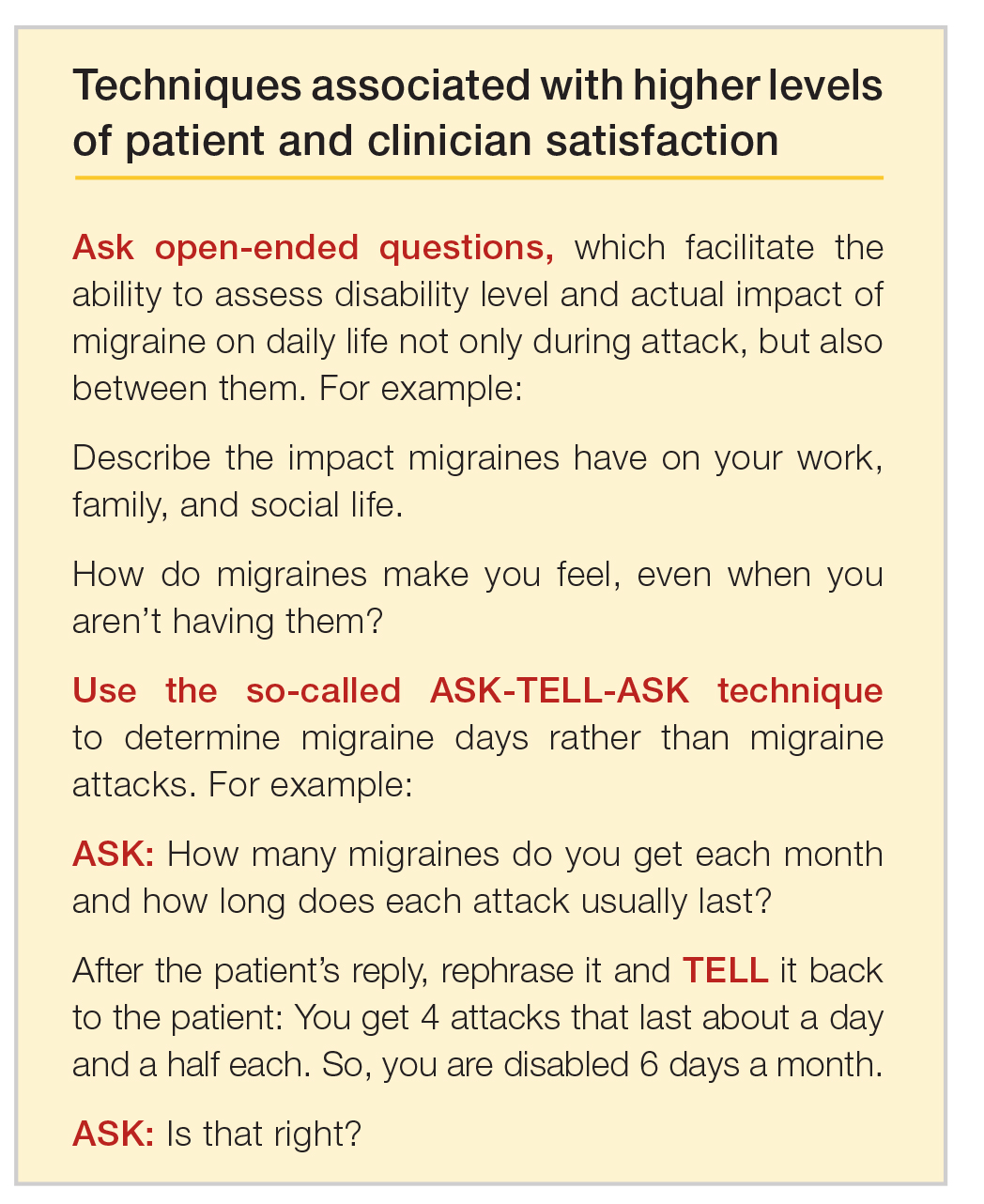

The clinician–patient conversation

A clinician’s detective skills are put to the test when evaluating patients with migraine. Avoiding dead-ends and fruitless pursuits can spare providers and patients frustration and help patients avoid needless suffering. Yet, as noted, the list of potential triggers appears endless, duration and frequency are variable, patients often try to control their environment with mixed results, and it is difficult to tell the difference between actual triggers and premonitory symptoms.

Which brings us back to Lola H. She desperately wanted to leave her appointment with confidence that she had enough medication to meet her needs each month. She might have expected to go home with access to more medication, but she did not. Rather, she left her clinician’s office with a plan to reduce the number of monthly migraine episodes she experienced, enabling her to use medication as needed, rather than only when her attacks were severe.

Her clinician confirmed that avoiding gasoline odor would reduce the number of attacks. Eliminating chocolates and sweets might, but it is not known whether chocolate is a trigger. He suggested that she try allowing herself chocolate now and then, which would probably serve as a stress reducer. The net result would likely be no change in number of episodes, while allowing for a small improvement in quality of life.

Perhaps most striking, Lola left the appointment certain that her issue with lower barometric pressure was resolved because her clinician took the time to ask how she knew about the daily barometric pressure levels.

Her smartwatch, she told him. He strongly suggested that she delete the watch’s barometric pressure app, which she did on the spot. At her next appointment, Lola was happy to report that barometric pressure no longer played a significant role in her episodes. Moreover, the other strategies she and her clinician discussed have reduced the number of severe and less severe episodes. She no longer lives with the stress of pill-rationing and looks forward to enjoying a small amount of chocolate ice cream each weekend with her family.