User login

Pre- and postprocedure skin care guide for your surgical patients

Whether patients are having a biopsy, surgical excision, or Mohs surgery, the outcome will be improved when the proper skin care is used before and after the procedure. This is a guide that you can use to educate your patients about pre- and postprocedure skin care needs.

Presurgery skin care and supplements

The goal is to speed healing and minimize infection, scarring, and hyperpigmentation. For 2 weeks prior to surgery, recommend products that have been shown to speed wound healing by increasing keratinization and/or collagen production. Ingredients that should be used prior to wounding include retinoids such as tretinoin and retinol. Several studies have convincingly shown that pretreatment with tretinoin speeds wound healing.1,2,3 Kligman and associates evaluated healing after punch biopsy and found the wounds on arms pretreated with tretinoin cream 0.05% to 0.1% were significantly smaller – by 35% to 37% – on days 1 and 4, and were 47% to 50% smaller on days 6, 8, and 11, compared with the untreated arms.4 Most studies suggest a 2- to 4-week tretinoin pretreatment regimen5 because peak epidermal hypertrophy occurs after 7 days of tretinoin application and normalizes after 14 days of continued treatment.6 This approach allows the skin to recover from any retinoid dermatitis prior to surgery. Adapalene should be started 5-6 weeks prior to procedures because it has a longer half-life and requires an earlier initiation period.7

Although wound healing studies have not been conducted in this area, pretreating skin with topical ascorbic acid8 and hydroxyacids9 might help speed wound healing by increasing collagen synthesis.

Ingredients and activities to avoid presurgery

Patients should avoid using ingredients that could promote skin tumor growth. Although there are no studies evaluating the effects of growth factors on promoting the growth of skin cancer, caution is prudent. To reduce bruising, patients should avoid aspirin, ibuprofen, naproxen, St. John’s Wort, vitamin E, omega-3 fatty acids supplements, flax seed oil, ginseng, salmon, and alcohol. Most physicians agree that these should be avoided for 10 days prior to the procedure. Smoking should be avoided 4 weeks prior to the procedure.

Postsurgery skin care and supplements

Oral vitamin C and zinc supplements have been shown to speed wound healing in rats when taken immediately after a procedure.10 Oral Arnica tablets and tinctures are often used prior to and after surgery to reduce bruising and inflammation. There is much anecdotal support for the use of Arnica, but clinical trial evidence substantiating its efficacy to prevent bruising and reduce swelling is scant.

A protein important in wound repair, defensin, is available in a topical formulation. Defensin14 has been shown to activate the leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein–coupled receptors 5 and 6 (also known as LGR5 and LGR6) stem cells. It speeds wound healing by increasing LGR stem cell migration into wound beds. Wounds should be covered to provide protection from sun exposure until reepithelialization occurs. Which occlusive ointments and wound repair products to use are beyond the scope of this article. Once epithelized, zinc oxide sunscreens can be used. These have been shown to be safe with minimal penetration into the skin.15

Ingredients to avoid post surgery

Topical retinoids should not be used post skin cancer surgery until epithelialization is complete. A study by Hung et al.16 in a porcine model used 0.05% tretinoin cream daily for 10 days prior to partial-thickness skin wounding demonstrated that use of tretinoin 10 days prior to wounding sped reepithelialization while use after the procedure slowed wound healing.

Acidic products will sting wounded skin. For this reason, benzoic acid, hydroxy acids, and ascorbic acid should be avoided until the skin has completely reepithelialized. Products with preservatives and fragrance should be avoided if possible.

Vitamin E derived from oral supplement capsules slowed healing after skin cancer surgery and had a high rate of contact dermatitis.17 Chemical sunscreens are more likely to cause an allergic contact dermatitis and should be avoided for 4 weeks after skin surgery. Organic products with essential oils and botanical ingredients may present a higher risk of contact dermatitis due to allergen exposure.

Conclusion

To ensure the best outcome from surgical treatments, patient education is a must! The more that patients know and understand about the ways in which they can prepare for their procedure and treat their skin after the procedure, the better the outcomes will be. Providers should give this type of information in an easy-to-follow printed instruction sheet because studies show that patients cannot remember most of the oral instructions offered by practitioners.

Encourage your patients to ask questions during their consultation and procedure and to get in touch with your office should they have any concerns when they leave. These steps help improve patient compliance and satisfaction, which will help you maintain a trusting relationship with established patients and attract new ones through word-of-mouth referrals.

Please email me at [email protected] if you have any other pre- and postprocedure skin care advice.

Dr. Leslie S. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients,” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems LLC.

References

1. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1995 May-Jun;19(3):243-6.

2. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011 Mar;127(3):1343-5.

3. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998 Aug;39(2 Pt 3):S79-81.

4. Br J Dermatol. 1995 Jan;132(1):46-53.

5. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004 Dec;51(6):940-6.

6. J Korean Med Sci. 1996 Aug;11(4):335-41.

7. Eur J Dermatol. 2002 Mar-Apr;12(2):145-8.

8. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981 May;78(5):2879-82.

9. Exp Dermatol. 2003;12 Suppl 2:57-63.

10. Surg Today. 2004;34(9):747-51.

11. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017 Jan/Feb;33(1):47-52.

12. Wound Repair Regen. 1998 Mar-Apr;6(2):167-77.

13. Dermatol Surg. 1998 Jun;24(6):661-4.

14. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013 Nov;132(5):1159-71.

15. ACS Nano. 2016 Feb 23;10(2):1810-9.

16. Arch Dermatol. 1989 Jan;125(1):65-9.

17. Dermatol Surg. 1999 Apr;25(4):311-5.

Retinoids should be used 2-3 times prior to procedures to speed healing.

Retinoids should not be used after the procedure until reepithelization has occurred.

Vitamin C and zinc supplements taken post procedure might speed wound healing.

Retinoids should be used 2-3 times prior to procedures to speed healing.

Retinoids should not be used after the procedure until reepithelization has occurred.

Vitamin C and zinc supplements taken post procedure might speed wound healing.

Retinoids should be used 2-3 times prior to procedures to speed healing.

Retinoids should not be used after the procedure until reepithelization has occurred.

Vitamin C and zinc supplements taken post procedure might speed wound healing.

Whether patients are having a biopsy, surgical excision, or Mohs surgery, the outcome will be improved when the proper skin care is used before and after the procedure. This is a guide that you can use to educate your patients about pre- and postprocedure skin care needs.

Presurgery skin care and supplements

The goal is to speed healing and minimize infection, scarring, and hyperpigmentation. For 2 weeks prior to surgery, recommend products that have been shown to speed wound healing by increasing keratinization and/or collagen production. Ingredients that should be used prior to wounding include retinoids such as tretinoin and retinol. Several studies have convincingly shown that pretreatment with tretinoin speeds wound healing.1,2,3 Kligman and associates evaluated healing after punch biopsy and found the wounds on arms pretreated with tretinoin cream 0.05% to 0.1% were significantly smaller – by 35% to 37% – on days 1 and 4, and were 47% to 50% smaller on days 6, 8, and 11, compared with the untreated arms.4 Most studies suggest a 2- to 4-week tretinoin pretreatment regimen5 because peak epidermal hypertrophy occurs after 7 days of tretinoin application and normalizes after 14 days of continued treatment.6 This approach allows the skin to recover from any retinoid dermatitis prior to surgery. Adapalene should be started 5-6 weeks prior to procedures because it has a longer half-life and requires an earlier initiation period.7

Although wound healing studies have not been conducted in this area, pretreating skin with topical ascorbic acid8 and hydroxyacids9 might help speed wound healing by increasing collagen synthesis.

Ingredients and activities to avoid presurgery

Patients should avoid using ingredients that could promote skin tumor growth. Although there are no studies evaluating the effects of growth factors on promoting the growth of skin cancer, caution is prudent. To reduce bruising, patients should avoid aspirin, ibuprofen, naproxen, St. John’s Wort, vitamin E, omega-3 fatty acids supplements, flax seed oil, ginseng, salmon, and alcohol. Most physicians agree that these should be avoided for 10 days prior to the procedure. Smoking should be avoided 4 weeks prior to the procedure.

Postsurgery skin care and supplements

Oral vitamin C and zinc supplements have been shown to speed wound healing in rats when taken immediately after a procedure.10 Oral Arnica tablets and tinctures are often used prior to and after surgery to reduce bruising and inflammation. There is much anecdotal support for the use of Arnica, but clinical trial evidence substantiating its efficacy to prevent bruising and reduce swelling is scant.

A protein important in wound repair, defensin, is available in a topical formulation. Defensin14 has been shown to activate the leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein–coupled receptors 5 and 6 (also known as LGR5 and LGR6) stem cells. It speeds wound healing by increasing LGR stem cell migration into wound beds. Wounds should be covered to provide protection from sun exposure until reepithelialization occurs. Which occlusive ointments and wound repair products to use are beyond the scope of this article. Once epithelized, zinc oxide sunscreens can be used. These have been shown to be safe with minimal penetration into the skin.15

Ingredients to avoid post surgery

Topical retinoids should not be used post skin cancer surgery until epithelialization is complete. A study by Hung et al.16 in a porcine model used 0.05% tretinoin cream daily for 10 days prior to partial-thickness skin wounding demonstrated that use of tretinoin 10 days prior to wounding sped reepithelialization while use after the procedure slowed wound healing.

Acidic products will sting wounded skin. For this reason, benzoic acid, hydroxy acids, and ascorbic acid should be avoided until the skin has completely reepithelialized. Products with preservatives and fragrance should be avoided if possible.

Vitamin E derived from oral supplement capsules slowed healing after skin cancer surgery and had a high rate of contact dermatitis.17 Chemical sunscreens are more likely to cause an allergic contact dermatitis and should be avoided for 4 weeks after skin surgery. Organic products with essential oils and botanical ingredients may present a higher risk of contact dermatitis due to allergen exposure.

Conclusion

To ensure the best outcome from surgical treatments, patient education is a must! The more that patients know and understand about the ways in which they can prepare for their procedure and treat their skin after the procedure, the better the outcomes will be. Providers should give this type of information in an easy-to-follow printed instruction sheet because studies show that patients cannot remember most of the oral instructions offered by practitioners.

Encourage your patients to ask questions during their consultation and procedure and to get in touch with your office should they have any concerns when they leave. These steps help improve patient compliance and satisfaction, which will help you maintain a trusting relationship with established patients and attract new ones through word-of-mouth referrals.

Please email me at [email protected] if you have any other pre- and postprocedure skin care advice.

Dr. Leslie S. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients,” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems LLC.

References

1. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1995 May-Jun;19(3):243-6.

2. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011 Mar;127(3):1343-5.

3. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998 Aug;39(2 Pt 3):S79-81.

4. Br J Dermatol. 1995 Jan;132(1):46-53.

5. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004 Dec;51(6):940-6.

6. J Korean Med Sci. 1996 Aug;11(4):335-41.

7. Eur J Dermatol. 2002 Mar-Apr;12(2):145-8.

8. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981 May;78(5):2879-82.

9. Exp Dermatol. 2003;12 Suppl 2:57-63.

10. Surg Today. 2004;34(9):747-51.

11. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017 Jan/Feb;33(1):47-52.

12. Wound Repair Regen. 1998 Mar-Apr;6(2):167-77.

13. Dermatol Surg. 1998 Jun;24(6):661-4.

14. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013 Nov;132(5):1159-71.

15. ACS Nano. 2016 Feb 23;10(2):1810-9.

16. Arch Dermatol. 1989 Jan;125(1):65-9.

17. Dermatol Surg. 1999 Apr;25(4):311-5.

Whether patients are having a biopsy, surgical excision, or Mohs surgery, the outcome will be improved when the proper skin care is used before and after the procedure. This is a guide that you can use to educate your patients about pre- and postprocedure skin care needs.

Presurgery skin care and supplements

The goal is to speed healing and minimize infection, scarring, and hyperpigmentation. For 2 weeks prior to surgery, recommend products that have been shown to speed wound healing by increasing keratinization and/or collagen production. Ingredients that should be used prior to wounding include retinoids such as tretinoin and retinol. Several studies have convincingly shown that pretreatment with tretinoin speeds wound healing.1,2,3 Kligman and associates evaluated healing after punch biopsy and found the wounds on arms pretreated with tretinoin cream 0.05% to 0.1% were significantly smaller – by 35% to 37% – on days 1 and 4, and were 47% to 50% smaller on days 6, 8, and 11, compared with the untreated arms.4 Most studies suggest a 2- to 4-week tretinoin pretreatment regimen5 because peak epidermal hypertrophy occurs after 7 days of tretinoin application and normalizes after 14 days of continued treatment.6 This approach allows the skin to recover from any retinoid dermatitis prior to surgery. Adapalene should be started 5-6 weeks prior to procedures because it has a longer half-life and requires an earlier initiation period.7

Although wound healing studies have not been conducted in this area, pretreating skin with topical ascorbic acid8 and hydroxyacids9 might help speed wound healing by increasing collagen synthesis.

Ingredients and activities to avoid presurgery

Patients should avoid using ingredients that could promote skin tumor growth. Although there are no studies evaluating the effects of growth factors on promoting the growth of skin cancer, caution is prudent. To reduce bruising, patients should avoid aspirin, ibuprofen, naproxen, St. John’s Wort, vitamin E, omega-3 fatty acids supplements, flax seed oil, ginseng, salmon, and alcohol. Most physicians agree that these should be avoided for 10 days prior to the procedure. Smoking should be avoided 4 weeks prior to the procedure.

Postsurgery skin care and supplements

Oral vitamin C and zinc supplements have been shown to speed wound healing in rats when taken immediately after a procedure.10 Oral Arnica tablets and tinctures are often used prior to and after surgery to reduce bruising and inflammation. There is much anecdotal support for the use of Arnica, but clinical trial evidence substantiating its efficacy to prevent bruising and reduce swelling is scant.

A protein important in wound repair, defensin, is available in a topical formulation. Defensin14 has been shown to activate the leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein–coupled receptors 5 and 6 (also known as LGR5 and LGR6) stem cells. It speeds wound healing by increasing LGR stem cell migration into wound beds. Wounds should be covered to provide protection from sun exposure until reepithelialization occurs. Which occlusive ointments and wound repair products to use are beyond the scope of this article. Once epithelized, zinc oxide sunscreens can be used. These have been shown to be safe with minimal penetration into the skin.15

Ingredients to avoid post surgery

Topical retinoids should not be used post skin cancer surgery until epithelialization is complete. A study by Hung et al.16 in a porcine model used 0.05% tretinoin cream daily for 10 days prior to partial-thickness skin wounding demonstrated that use of tretinoin 10 days prior to wounding sped reepithelialization while use after the procedure slowed wound healing.

Acidic products will sting wounded skin. For this reason, benzoic acid, hydroxy acids, and ascorbic acid should be avoided until the skin has completely reepithelialized. Products with preservatives and fragrance should be avoided if possible.

Vitamin E derived from oral supplement capsules slowed healing after skin cancer surgery and had a high rate of contact dermatitis.17 Chemical sunscreens are more likely to cause an allergic contact dermatitis and should be avoided for 4 weeks after skin surgery. Organic products with essential oils and botanical ingredients may present a higher risk of contact dermatitis due to allergen exposure.

Conclusion

To ensure the best outcome from surgical treatments, patient education is a must! The more that patients know and understand about the ways in which they can prepare for their procedure and treat their skin after the procedure, the better the outcomes will be. Providers should give this type of information in an easy-to-follow printed instruction sheet because studies show that patients cannot remember most of the oral instructions offered by practitioners.

Encourage your patients to ask questions during their consultation and procedure and to get in touch with your office should they have any concerns when they leave. These steps help improve patient compliance and satisfaction, which will help you maintain a trusting relationship with established patients and attract new ones through word-of-mouth referrals.

Please email me at [email protected] if you have any other pre- and postprocedure skin care advice.

Dr. Leslie S. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients,” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems LLC.

References

1. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1995 May-Jun;19(3):243-6.

2. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011 Mar;127(3):1343-5.

3. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998 Aug;39(2 Pt 3):S79-81.

4. Br J Dermatol. 1995 Jan;132(1):46-53.

5. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004 Dec;51(6):940-6.

6. J Korean Med Sci. 1996 Aug;11(4):335-41.

7. Eur J Dermatol. 2002 Mar-Apr;12(2):145-8.

8. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981 May;78(5):2879-82.

9. Exp Dermatol. 2003;12 Suppl 2:57-63.

10. Surg Today. 2004;34(9):747-51.

11. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017 Jan/Feb;33(1):47-52.

12. Wound Repair Regen. 1998 Mar-Apr;6(2):167-77.

13. Dermatol Surg. 1998 Jun;24(6):661-4.

14. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013 Nov;132(5):1159-71.

15. ACS Nano. 2016 Feb 23;10(2):1810-9.

16. Arch Dermatol. 1989 Jan;125(1):65-9.

17. Dermatol Surg. 1999 Apr;25(4):311-5.

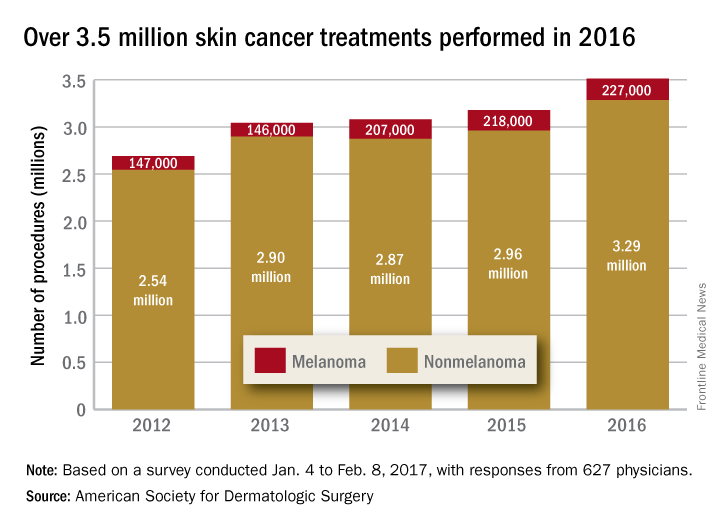

Skin cancer procedures up by 35% since 2012

The number of skin cancer procedures in 2016 was up by 10.5% since 2015 and by 35% since 2012, according to the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

Of the estimated 3.5 million skin cancer treatments provided by dermatologic surgeons in 2016, just over 227,000, or 6.5%, were for melanoma – a 4% increase over those diagnosed in 2015. Since 2012, the annual number of melanoma procedures has risen by 55%. The 3.29 million nonmelanoma procedures performed in 2016 represent a 10% increase over 2015, the ASDS said in a report on its 2016 Survey on Dermatologic Procedures.

“The public is increasingly aware of the need to have any new or suspicious lesions checked,” ASDS President Thomas Rohrer, MD, said in a written statement.

In addition to the skin cancer treatments, ASDS members also performed over 7 million cosmetic procedures in 2016, including 2.8 million involving laser, light, and energy-based devices. Additionally, 1.7 million involving neuromodulators, and 1.35 million involved soft-tissue fillers, the ASDS said.

The procedures survey was conducted Jan. 4 to Feb. 8, 2017, and included 627 physicians’ responses, which were then generalized to represent all of the almost 6,100 ASDS members.

The number of skin cancer procedures in 2016 was up by 10.5% since 2015 and by 35% since 2012, according to the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

Of the estimated 3.5 million skin cancer treatments provided by dermatologic surgeons in 2016, just over 227,000, or 6.5%, were for melanoma – a 4% increase over those diagnosed in 2015. Since 2012, the annual number of melanoma procedures has risen by 55%. The 3.29 million nonmelanoma procedures performed in 2016 represent a 10% increase over 2015, the ASDS said in a report on its 2016 Survey on Dermatologic Procedures.

“The public is increasingly aware of the need to have any new or suspicious lesions checked,” ASDS President Thomas Rohrer, MD, said in a written statement.

In addition to the skin cancer treatments, ASDS members also performed over 7 million cosmetic procedures in 2016, including 2.8 million involving laser, light, and energy-based devices. Additionally, 1.7 million involving neuromodulators, and 1.35 million involved soft-tissue fillers, the ASDS said.

The procedures survey was conducted Jan. 4 to Feb. 8, 2017, and included 627 physicians’ responses, which were then generalized to represent all of the almost 6,100 ASDS members.

The number of skin cancer procedures in 2016 was up by 10.5% since 2015 and by 35% since 2012, according to the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

Of the estimated 3.5 million skin cancer treatments provided by dermatologic surgeons in 2016, just over 227,000, or 6.5%, were for melanoma – a 4% increase over those diagnosed in 2015. Since 2012, the annual number of melanoma procedures has risen by 55%. The 3.29 million nonmelanoma procedures performed in 2016 represent a 10% increase over 2015, the ASDS said in a report on its 2016 Survey on Dermatologic Procedures.

“The public is increasingly aware of the need to have any new or suspicious lesions checked,” ASDS President Thomas Rohrer, MD, said in a written statement.

In addition to the skin cancer treatments, ASDS members also performed over 7 million cosmetic procedures in 2016, including 2.8 million involving laser, light, and energy-based devices. Additionally, 1.7 million involving neuromodulators, and 1.35 million involved soft-tissue fillers, the ASDS said.

The procedures survey was conducted Jan. 4 to Feb. 8, 2017, and included 627 physicians’ responses, which were then generalized to represent all of the almost 6,100 ASDS members.

Cutaneous laser surgery: Basic caution isn’t enough to prevent lawsuits

SAN DIEGO – Injuries and lawsuits related to laser cosmetic surgery are increasing and potential legal threats are not always easy to predict, according to two dermatologists who spoke at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery (ASLMS).

A laser procedure could go smoothly, for example, but the patient might be able to successfully sue if he or she is allowed to drive home after receiving a sedative. Or a physician might get sued because his or her nurse set a laser at the wrong setting and singed a patient.

The risk of a lawsuit is high, H. Ray Jalian, MD, a dermatologist in Los Angeles, said at the meeting. “The reality is that we’re all at some point going to face this.”

The most common procedure litigated was laser hair removal, making up almost 40% of the cases, which is not an indication that this particular procedure is dangerous, Dr. Jalian said. “It’s quite safe, and the complication rate is quite low,” but more of these procedures are being done, he noted. Rejuvenation procedures followed, accounting for 25% of cases.

The alleged injuries sustained from laser surgery included burns (47%), scars (39%), and pigmentation problems (24%). Deaths occurred in just over 2% of the cases. In the study, almost a third of plaintiffs alleged that they were not provided informed consent. Plaintiffs also alleged fraud (9%) and assault/battery (5%), and a family member occasionally sued for loss of consortium (8% of cases). The specialty with the largest percentage of the cases was plastic surgery (26%), followed by dermatology (21%).

Dr. Jalian and his copresenter, Mathew Avram, MD, JD, director of the Dermatology Laser & Cosmetic Center, and director of dermatologic surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, offered these lessons about the legal risks associated with laser procedures:

• You may have a duty to protect your patient from bad choices.

Physicians aren’t expected to keep patients from making certain bad decisions such as sunbathing after a traditional resurfacing procedure, said Dr. Avram, of the department of dermatology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and the ASLMS president. But in some cases, he said, the law may expect the physician to step in to prevent harm. For example, he said, a patient who has undergone a fractional ablative laser procedure and has received a sedative should not be allowed to drive home.

• You may get sued even if your employee is at fault.

The 2013 study found physicians were often sued even when they did not perform the laser procedure in question. Nonphysicians such as physician assistants and nurses often perform laser operations, and many states allow them to do so. “Nonphysicians were less likely to be sued even if they were the operators,” Dr. Jalian said. In the study, almost 38% of the 174 analyzed cases involved nonphysician operators, but they were sued in just 26% of the cases. In 33 of the 174 cases in the study, plaintiffs alleged failure to properly hire, train, or supervise staff.

He recommended looking at state laws, which differ greatly in their regulations – or lack of them – regarding the operation of medical lasers. In some cases, physicians must supervise laser use, he said. “But what are the requirements? Can you be available by phone down the street or in the Caribbean?”

Dr. Jalian, Dr. Avram, and a colleague followed up the 2013 study with another study that tracked 175 legal cases from 1999 to 2012 involving alleged injuries from cutaneous laser surgery. During this time period, 75 (43%) involved a nonphysician operating a laser, increasing from 36% in 2008 to 78% in 2012.

In almost two-thirds of cases, the procedures in question were done by nonphysicians outside a “traditional medical setting” such as a salon or spa (JAMA Dermatol. 2014 Apr;150[4]:407-11).

• Delayed side effects could mean delayed lawsuits.

According to Dr. Avram, statutes of limitations – the length of time in which a patient can file a lawsuit – typically last for 2-3 years in malpractice cases. But he said that the period begins when the physician is alleged to have made a mistake or when the patient becomes aware of – or should reasonably be aware of – an injury. Therefore, physicians could face legal trouble over delayed hypopigmentation that appears 6 months after a laser resurfacing treatment, or granulomas that appear years after a filler treatment, he said.

• A signed form is not a cure-all.

It is wise to make patients sign an extensive informed consent form, but this will not protect a physician against a claim of negligence, Dr. Avram said. And the reverse is also true: If a patient did not sign a proper consent form, he or she could still sue even if the procedure went perfectly, he noted.

• Your instincts are worth trusting.

When it comes to lawsuit prevention, Dr. Avram said, “by far the most important thing you can do happens within a minute of when you see the patient. Assess and trust your own intuition and your staff’s intuition. For elective, cosmetic treatments, don’t be afraid to say no. There’s no legal obligation to perform a cosmetic treatment on a patient.”

If you do choose to treat a patient, he advised, be open about the procedure and “maybe even tell them some of the tougher, worse-case scenarios.” If a procedure goes poorly, he said, consider how to fix it. “Many complications can be significantly improved or cleared with timely and appropriate intervention,” he said.

In some cases, refunding the patient’s money can be considered, with the patient signing a release, he said. “Document that you are refunding the money in order to preserve the doctor-patient relationship, not to avoid negligence.”

Dr. Jalian and Dr. Avram reported no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Injuries and lawsuits related to laser cosmetic surgery are increasing and potential legal threats are not always easy to predict, according to two dermatologists who spoke at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery (ASLMS).

A laser procedure could go smoothly, for example, but the patient might be able to successfully sue if he or she is allowed to drive home after receiving a sedative. Or a physician might get sued because his or her nurse set a laser at the wrong setting and singed a patient.

The risk of a lawsuit is high, H. Ray Jalian, MD, a dermatologist in Los Angeles, said at the meeting. “The reality is that we’re all at some point going to face this.”

The most common procedure litigated was laser hair removal, making up almost 40% of the cases, which is not an indication that this particular procedure is dangerous, Dr. Jalian said. “It’s quite safe, and the complication rate is quite low,” but more of these procedures are being done, he noted. Rejuvenation procedures followed, accounting for 25% of cases.

The alleged injuries sustained from laser surgery included burns (47%), scars (39%), and pigmentation problems (24%). Deaths occurred in just over 2% of the cases. In the study, almost a third of plaintiffs alleged that they were not provided informed consent. Plaintiffs also alleged fraud (9%) and assault/battery (5%), and a family member occasionally sued for loss of consortium (8% of cases). The specialty with the largest percentage of the cases was plastic surgery (26%), followed by dermatology (21%).

Dr. Jalian and his copresenter, Mathew Avram, MD, JD, director of the Dermatology Laser & Cosmetic Center, and director of dermatologic surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, offered these lessons about the legal risks associated with laser procedures:

• You may have a duty to protect your patient from bad choices.

Physicians aren’t expected to keep patients from making certain bad decisions such as sunbathing after a traditional resurfacing procedure, said Dr. Avram, of the department of dermatology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and the ASLMS president. But in some cases, he said, the law may expect the physician to step in to prevent harm. For example, he said, a patient who has undergone a fractional ablative laser procedure and has received a sedative should not be allowed to drive home.

• You may get sued even if your employee is at fault.

The 2013 study found physicians were often sued even when they did not perform the laser procedure in question. Nonphysicians such as physician assistants and nurses often perform laser operations, and many states allow them to do so. “Nonphysicians were less likely to be sued even if they were the operators,” Dr. Jalian said. In the study, almost 38% of the 174 analyzed cases involved nonphysician operators, but they were sued in just 26% of the cases. In 33 of the 174 cases in the study, plaintiffs alleged failure to properly hire, train, or supervise staff.

He recommended looking at state laws, which differ greatly in their regulations – or lack of them – regarding the operation of medical lasers. In some cases, physicians must supervise laser use, he said. “But what are the requirements? Can you be available by phone down the street or in the Caribbean?”

Dr. Jalian, Dr. Avram, and a colleague followed up the 2013 study with another study that tracked 175 legal cases from 1999 to 2012 involving alleged injuries from cutaneous laser surgery. During this time period, 75 (43%) involved a nonphysician operating a laser, increasing from 36% in 2008 to 78% in 2012.

In almost two-thirds of cases, the procedures in question were done by nonphysicians outside a “traditional medical setting” such as a salon or spa (JAMA Dermatol. 2014 Apr;150[4]:407-11).

• Delayed side effects could mean delayed lawsuits.

According to Dr. Avram, statutes of limitations – the length of time in which a patient can file a lawsuit – typically last for 2-3 years in malpractice cases. But he said that the period begins when the physician is alleged to have made a mistake or when the patient becomes aware of – or should reasonably be aware of – an injury. Therefore, physicians could face legal trouble over delayed hypopigmentation that appears 6 months after a laser resurfacing treatment, or granulomas that appear years after a filler treatment, he said.

• A signed form is not a cure-all.

It is wise to make patients sign an extensive informed consent form, but this will not protect a physician against a claim of negligence, Dr. Avram said. And the reverse is also true: If a patient did not sign a proper consent form, he or she could still sue even if the procedure went perfectly, he noted.

• Your instincts are worth trusting.

When it comes to lawsuit prevention, Dr. Avram said, “by far the most important thing you can do happens within a minute of when you see the patient. Assess and trust your own intuition and your staff’s intuition. For elective, cosmetic treatments, don’t be afraid to say no. There’s no legal obligation to perform a cosmetic treatment on a patient.”

If you do choose to treat a patient, he advised, be open about the procedure and “maybe even tell them some of the tougher, worse-case scenarios.” If a procedure goes poorly, he said, consider how to fix it. “Many complications can be significantly improved or cleared with timely and appropriate intervention,” he said.

In some cases, refunding the patient’s money can be considered, with the patient signing a release, he said. “Document that you are refunding the money in order to preserve the doctor-patient relationship, not to avoid negligence.”

Dr. Jalian and Dr. Avram reported no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Injuries and lawsuits related to laser cosmetic surgery are increasing and potential legal threats are not always easy to predict, according to two dermatologists who spoke at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery (ASLMS).

A laser procedure could go smoothly, for example, but the patient might be able to successfully sue if he or she is allowed to drive home after receiving a sedative. Or a physician might get sued because his or her nurse set a laser at the wrong setting and singed a patient.

The risk of a lawsuit is high, H. Ray Jalian, MD, a dermatologist in Los Angeles, said at the meeting. “The reality is that we’re all at some point going to face this.”

The most common procedure litigated was laser hair removal, making up almost 40% of the cases, which is not an indication that this particular procedure is dangerous, Dr. Jalian said. “It’s quite safe, and the complication rate is quite low,” but more of these procedures are being done, he noted. Rejuvenation procedures followed, accounting for 25% of cases.

The alleged injuries sustained from laser surgery included burns (47%), scars (39%), and pigmentation problems (24%). Deaths occurred in just over 2% of the cases. In the study, almost a third of plaintiffs alleged that they were not provided informed consent. Plaintiffs also alleged fraud (9%) and assault/battery (5%), and a family member occasionally sued for loss of consortium (8% of cases). The specialty with the largest percentage of the cases was plastic surgery (26%), followed by dermatology (21%).

Dr. Jalian and his copresenter, Mathew Avram, MD, JD, director of the Dermatology Laser & Cosmetic Center, and director of dermatologic surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, offered these lessons about the legal risks associated with laser procedures:

• You may have a duty to protect your patient from bad choices.

Physicians aren’t expected to keep patients from making certain bad decisions such as sunbathing after a traditional resurfacing procedure, said Dr. Avram, of the department of dermatology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and the ASLMS president. But in some cases, he said, the law may expect the physician to step in to prevent harm. For example, he said, a patient who has undergone a fractional ablative laser procedure and has received a sedative should not be allowed to drive home.

• You may get sued even if your employee is at fault.

The 2013 study found physicians were often sued even when they did not perform the laser procedure in question. Nonphysicians such as physician assistants and nurses often perform laser operations, and many states allow them to do so. “Nonphysicians were less likely to be sued even if they were the operators,” Dr. Jalian said. In the study, almost 38% of the 174 analyzed cases involved nonphysician operators, but they were sued in just 26% of the cases. In 33 of the 174 cases in the study, plaintiffs alleged failure to properly hire, train, or supervise staff.

He recommended looking at state laws, which differ greatly in their regulations – or lack of them – regarding the operation of medical lasers. In some cases, physicians must supervise laser use, he said. “But what are the requirements? Can you be available by phone down the street or in the Caribbean?”

Dr. Jalian, Dr. Avram, and a colleague followed up the 2013 study with another study that tracked 175 legal cases from 1999 to 2012 involving alleged injuries from cutaneous laser surgery. During this time period, 75 (43%) involved a nonphysician operating a laser, increasing from 36% in 2008 to 78% in 2012.

In almost two-thirds of cases, the procedures in question were done by nonphysicians outside a “traditional medical setting” such as a salon or spa (JAMA Dermatol. 2014 Apr;150[4]:407-11).

• Delayed side effects could mean delayed lawsuits.

According to Dr. Avram, statutes of limitations – the length of time in which a patient can file a lawsuit – typically last for 2-3 years in malpractice cases. But he said that the period begins when the physician is alleged to have made a mistake or when the patient becomes aware of – or should reasonably be aware of – an injury. Therefore, physicians could face legal trouble over delayed hypopigmentation that appears 6 months after a laser resurfacing treatment, or granulomas that appear years after a filler treatment, he said.

• A signed form is not a cure-all.

It is wise to make patients sign an extensive informed consent form, but this will not protect a physician against a claim of negligence, Dr. Avram said. And the reverse is also true: If a patient did not sign a proper consent form, he or she could still sue even if the procedure went perfectly, he noted.

• Your instincts are worth trusting.

When it comes to lawsuit prevention, Dr. Avram said, “by far the most important thing you can do happens within a minute of when you see the patient. Assess and trust your own intuition and your staff’s intuition. For elective, cosmetic treatments, don’t be afraid to say no. There’s no legal obligation to perform a cosmetic treatment on a patient.”

If you do choose to treat a patient, he advised, be open about the procedure and “maybe even tell them some of the tougher, worse-case scenarios.” If a procedure goes poorly, he said, consider how to fix it. “Many complications can be significantly improved or cleared with timely and appropriate intervention,” he said.

In some cases, refunding the patient’s money can be considered, with the patient signing a release, he said. “Document that you are refunding the money in order to preserve the doctor-patient relationship, not to avoid negligence.”

Dr. Jalian and Dr. Avram reported no relevant disclosures.

AT LASER 2017

VIDEO: Surgery succeeds with select hidradenitis suppurativa patients

WASHINGTON – Medication has its limits for some patients with more severe hidradenitis suppurativa, and these patients can often benefit from surgical treatment, Chris Sayed, MD, said at an educational session held by George Washington University.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

“Especially if patients have relatively limited areas of sinus, being able to do some local procedures [is] what will get the patient a lot better,” Dr. Sayed of the department of dermatology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, said in a video interview. “Whereas the medicines would never have made that sinus go away.”

The meeting was supported by AbbVie. Dr. Sayed disclosed financial relationships with the company.

WASHINGTON – Medication has its limits for some patients with more severe hidradenitis suppurativa, and these patients can often benefit from surgical treatment, Chris Sayed, MD, said at an educational session held by George Washington University.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

“Especially if patients have relatively limited areas of sinus, being able to do some local procedures [is] what will get the patient a lot better,” Dr. Sayed of the department of dermatology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, said in a video interview. “Whereas the medicines would never have made that sinus go away.”

The meeting was supported by AbbVie. Dr. Sayed disclosed financial relationships with the company.

WASHINGTON – Medication has its limits for some patients with more severe hidradenitis suppurativa, and these patients can often benefit from surgical treatment, Chris Sayed, MD, said at an educational session held by George Washington University.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

“Especially if patients have relatively limited areas of sinus, being able to do some local procedures [is] what will get the patient a lot better,” Dr. Sayed of the department of dermatology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, said in a video interview. “Whereas the medicines would never have made that sinus go away.”

The meeting was supported by AbbVie. Dr. Sayed disclosed financial relationships with the company.

The power of words in aesthetic procedures and healing patients

The words we choose to use prior to procedures can positively or negatively impact a patient’s experience during a procedure and their decision to have the procedure performed. A practical example would include using the word discomfort instead of pain to describe pain that may be associated with a procedure. The root word of discomfort is comfort, which the mind focuses on and creates less of an anxious state than pain.

Obviously, the need to provide proper and realistic expectations, as well as risks and benefits, is of utmost importance when obtaining informed consent. The words used can put a patient’s mind at ease or cause further anxiety about ideas of needles, scalpels, pain, risk of infection, and bleeding that are part of our everyday procedures.

Judith Thomas, DDS, a dentist in Virginia who is trained in clinical hypnosis, once described the power of the word but. People will often put more emphasis in their minds on what is said after the word but than on what is said before. For example, in a romantic relationship context, saying “I love you, but you drive me crazy” has a different impact than “You drive me crazy, but I love you.” The focus tends to stay on the “I love you” portion more when it is said last, after the “but.”

The same phenomenon can happen when we discuss procedures with our patients. When a medical assistant performs phlebotomy or when we as doctors are about to perform an injection, instead of saying this is going to hurt, another way to phrase it would be “In a moment you may feel something, but it doesn’t have to bother you” or “You may experience some discomfort, but it will resolve quickly.” Something I’ve said for years to patients before surgery is “You may feel a little stinging as the anesthetic goes in, after that you may feel me touching you, but nothing uncomfortable.” I guess I had been intuitively using this technique for years, without knowing the impact of the word “but.” Perhaps now that I am more mindful of it, I will be even more mindful of how I phrase these terms. We, in addition to our nurses and medical assistants, can use these techniques to enhance patient comfort and the patient’s experience.

According to the American Society of Clinical Hypnosis, physicians and dentists used the power of words through hypnosis as anesthesia before the first chemical general anesthetic agent, ether, was used for surgery in the 1840s, followed by chloroform. Prior to this time, British and Scottish physicians John Elliotson, James Esdaile, and James Braid performed over 3,000 procedures and surgeries with clinical hypnosis alone. Some may argue that the ancient Egyptians also used hypnosis for their well-described surgeries, as no other anesthetic has been documented. Moreover, there is evidence of “sleep temples” that the ancient Egyptians used for healing.1

This article is not to suggest that our words should replace anesthesia. Many advances in anesthesia and pain control have been made since the time of chloroform. However, being mindful of our words can aid and assist in our surgical and aesthetic procedures where less anesthesia is used: Patients feel more comfortable, they heal faster, and overall, they have a more positive outcome and pleasant physician-patient experience.2

For patients, the skill of the doctor and the outcome of the procedure are of the utmost importance, but, especially in aesthetic dermatology, where some of our procedures are repeated or performed periodically, the positive impact of the entire experience will entrust them with your care long term.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Mutter, C.B. (1998). History of Hypnosis. (pp. 10-12) “Hypnotic Induction and Suggestion.” Chicago: American Society of Clinical Hypnosis.

2. Burns. 2010 Aug;36(5):639-46.

The words we choose to use prior to procedures can positively or negatively impact a patient’s experience during a procedure and their decision to have the procedure performed. A practical example would include using the word discomfort instead of pain to describe pain that may be associated with a procedure. The root word of discomfort is comfort, which the mind focuses on and creates less of an anxious state than pain.

Obviously, the need to provide proper and realistic expectations, as well as risks and benefits, is of utmost importance when obtaining informed consent. The words used can put a patient’s mind at ease or cause further anxiety about ideas of needles, scalpels, pain, risk of infection, and bleeding that are part of our everyday procedures.

Judith Thomas, DDS, a dentist in Virginia who is trained in clinical hypnosis, once described the power of the word but. People will often put more emphasis in their minds on what is said after the word but than on what is said before. For example, in a romantic relationship context, saying “I love you, but you drive me crazy” has a different impact than “You drive me crazy, but I love you.” The focus tends to stay on the “I love you” portion more when it is said last, after the “but.”

The same phenomenon can happen when we discuss procedures with our patients. When a medical assistant performs phlebotomy or when we as doctors are about to perform an injection, instead of saying this is going to hurt, another way to phrase it would be “In a moment you may feel something, but it doesn’t have to bother you” or “You may experience some discomfort, but it will resolve quickly.” Something I’ve said for years to patients before surgery is “You may feel a little stinging as the anesthetic goes in, after that you may feel me touching you, but nothing uncomfortable.” I guess I had been intuitively using this technique for years, without knowing the impact of the word “but.” Perhaps now that I am more mindful of it, I will be even more mindful of how I phrase these terms. We, in addition to our nurses and medical assistants, can use these techniques to enhance patient comfort and the patient’s experience.

According to the American Society of Clinical Hypnosis, physicians and dentists used the power of words through hypnosis as anesthesia before the first chemical general anesthetic agent, ether, was used for surgery in the 1840s, followed by chloroform. Prior to this time, British and Scottish physicians John Elliotson, James Esdaile, and James Braid performed over 3,000 procedures and surgeries with clinical hypnosis alone. Some may argue that the ancient Egyptians also used hypnosis for their well-described surgeries, as no other anesthetic has been documented. Moreover, there is evidence of “sleep temples” that the ancient Egyptians used for healing.1

This article is not to suggest that our words should replace anesthesia. Many advances in anesthesia and pain control have been made since the time of chloroform. However, being mindful of our words can aid and assist in our surgical and aesthetic procedures where less anesthesia is used: Patients feel more comfortable, they heal faster, and overall, they have a more positive outcome and pleasant physician-patient experience.2

For patients, the skill of the doctor and the outcome of the procedure are of the utmost importance, but, especially in aesthetic dermatology, where some of our procedures are repeated or performed periodically, the positive impact of the entire experience will entrust them with your care long term.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Mutter, C.B. (1998). History of Hypnosis. (pp. 10-12) “Hypnotic Induction and Suggestion.” Chicago: American Society of Clinical Hypnosis.

2. Burns. 2010 Aug;36(5):639-46.

The words we choose to use prior to procedures can positively or negatively impact a patient’s experience during a procedure and their decision to have the procedure performed. A practical example would include using the word discomfort instead of pain to describe pain that may be associated with a procedure. The root word of discomfort is comfort, which the mind focuses on and creates less of an anxious state than pain.

Obviously, the need to provide proper and realistic expectations, as well as risks and benefits, is of utmost importance when obtaining informed consent. The words used can put a patient’s mind at ease or cause further anxiety about ideas of needles, scalpels, pain, risk of infection, and bleeding that are part of our everyday procedures.

Judith Thomas, DDS, a dentist in Virginia who is trained in clinical hypnosis, once described the power of the word but. People will often put more emphasis in their minds on what is said after the word but than on what is said before. For example, in a romantic relationship context, saying “I love you, but you drive me crazy” has a different impact than “You drive me crazy, but I love you.” The focus tends to stay on the “I love you” portion more when it is said last, after the “but.”

The same phenomenon can happen when we discuss procedures with our patients. When a medical assistant performs phlebotomy or when we as doctors are about to perform an injection, instead of saying this is going to hurt, another way to phrase it would be “In a moment you may feel something, but it doesn’t have to bother you” or “You may experience some discomfort, but it will resolve quickly.” Something I’ve said for years to patients before surgery is “You may feel a little stinging as the anesthetic goes in, after that you may feel me touching you, but nothing uncomfortable.” I guess I had been intuitively using this technique for years, without knowing the impact of the word “but.” Perhaps now that I am more mindful of it, I will be even more mindful of how I phrase these terms. We, in addition to our nurses and medical assistants, can use these techniques to enhance patient comfort and the patient’s experience.

According to the American Society of Clinical Hypnosis, physicians and dentists used the power of words through hypnosis as anesthesia before the first chemical general anesthetic agent, ether, was used for surgery in the 1840s, followed by chloroform. Prior to this time, British and Scottish physicians John Elliotson, James Esdaile, and James Braid performed over 3,000 procedures and surgeries with clinical hypnosis alone. Some may argue that the ancient Egyptians also used hypnosis for their well-described surgeries, as no other anesthetic has been documented. Moreover, there is evidence of “sleep temples” that the ancient Egyptians used for healing.1

This article is not to suggest that our words should replace anesthesia. Many advances in anesthesia and pain control have been made since the time of chloroform. However, being mindful of our words can aid and assist in our surgical and aesthetic procedures where less anesthesia is used: Patients feel more comfortable, they heal faster, and overall, they have a more positive outcome and pleasant physician-patient experience.2

For patients, the skill of the doctor and the outcome of the procedure are of the utmost importance, but, especially in aesthetic dermatology, where some of our procedures are repeated or performed periodically, the positive impact of the entire experience will entrust them with your care long term.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Mutter, C.B. (1998). History of Hypnosis. (pp. 10-12) “Hypnotic Induction and Suggestion.” Chicago: American Society of Clinical Hypnosis.

2. Burns. 2010 Aug;36(5):639-46.