User login

Skeletal-Related Events in Patients With Multiple Myeloma and Prostate Cancer Who Receive Standard vs Extended-Interval Bisphosphonate Dosing (FULL)

In patients with multiple myeloma and prostate cancer, extending the bisphosphonatedosing interval may help decrease medication-related morbidity without compromising therapeutic benefit.

Bone pain is one of the most common causes of morbidity in multiple myeloma (MM) and metastatic prostate cancer (CaP). This pain originates with the underlying pathologic processes of the cancer and with downstream skeletal-related events (SREs). SREs—fractures, spinal cord compression, and irradiation or surgery performed in ≥ 1 bone sites—represent a significant health care burden, particularly given the incidence of the underlying malignancies. According to American Cancer Society statistics, CaP is the second most common cancer in American men, and MM the second most common hematologic malignancy, despite its relatively low overall lifetime risk.1,2 Regardless of the underlying malignancy, bisphosphonates are the cornerstone of SRE prevention, though the optimal dosing strategy is the subject of clinical debate.

Although similar in SRE incidence, MM and CaP have distinct pathophysiologic processes in the dysregulation of bone resorption. MM is a hematologic malignancy that increases the risk of SREs by osteoclast up-regulation, primarily through the RANK (receptor activator of nuclear factor α-B) signaling pathway.3 CaP is a solid tumor malignancy that metastasizes to bone. Dysregulation of the bone resorption or formation cycle and net bone loss are a result of endogenous osteoclast up-regulation in response to abnormal bone formation in osteoblastic bone metastases.4 Androgen-deprivation therapy, the cornerstone of CaP treatment, further predisposes CaP patients to osteoporosis and SREs.

Prevention of SREs is pharmacologically driven by bisphosphonates, which have antiresorptive effects on bone through promotion of osteoclast apoptosis.5 Two IV formulations, pamidronate and zoledronic acid (ZA), are US Food and Drug Administration approved for use in bone metastases from MM or solid tumors.6-10 Although generally well tolerated, bisphosphonates can cause osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ), an avascular death of bone tissue, particularly with prolonged use.11 With its documented incidence of 5% to 6.7% in bone metastasis, ONJ represents a significant morbidity risk in patients with MM and CaP who are treated with IV bisphosphonates.12

Investigators are exploring bisphosphonate dosing intervals to determine which is most appropriate in mitigating the risk of ONJ. Before 2006, bisphosphonates were consistently dosed once monthly in patients with MM or metastatic bone disease—a standard derived empirically rather than from comparative studies or compelling pharmacodynamic data.13-15 In a 2006 consensus statement, the Mayo Clinic issued an expert opinion recommendation for increasing the bisphosphonate dosing interval to every 3 months in patients with MM.16 The first objective evidence for the clinical applicability of extending the ZA dosing interval was reported by Himelstein and colleagues in 2017.17 The randomized clinical trial found no differences in SRE rates when ZA was dosed every 12 weeks,17 prompting a conditional recommendation for dosing interval extension in the American Society of Clinical Oncology MM treatment guidelines (2018).13 Because of the age and racial demographics of the patients in these studies, many questions remain unanswered.

For the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) population, the pharmacokinetic and dynamic differences imposed by age and race limit the applicability of the available data. However, in veterans with MM or CaP, extending the bisphosphonate dosing interval may help decrease medication-related morbidity (eg, ONJ, nephrotoxicity) without compromising therapeutic benefit. To this end at the Memphis VA Medical Center (VAMC), we assessed for differences in SRE rates by comparing outcomes of patients who received ZA in standard- vs extended-interval dosing.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the Computerized Patient Record System for veterans with MM or metastatic CaP treated with ZA at the Memphis VAMC. Study inclusion criteria were aged > 18 years and care provided by a Memphis VAMC oncologist between January 2003 and January 2018. The study was approved by the Memphis VAMC’s Institutional Review Board, and procedures were followed in accordance with the ethical standards of its committee on human experimentation.

Using Microsoft SQL 2016 (Redmond, WA), we performed a query to identify patients who were prescribed ZA during the study period. Exclusion criteria were ZA prescribed for an indication other than MM or CaP (ie, osteoporosis) and receipt of ≤ 1 dose of ZA. Once a list was compiled, patients were stratified by ZA dosing interval: standard (mean, every month) or extended (mean, every 3 months). Patients whose ZA dosing interval was changed during treatment were included as independent data points in each group.

Skeletal-related events included fractures, spinal compression, irradiation, and surgery. Fractures and spinal compression were pertinent in the presence of radiographic documentation (eg, X-ray, magnetic resonance imaging scan) during the period the patient received ZA or within 1 dosing interval of the last recorded ZA dose. Irradiation was defined as documented application of radiation therapy to ≥ 1 bone sites for palliation of pain or as an intervention in the setting of spinal compression. Surgery was defined as any procedure performed to correct a fracture or spinal compression. Each SRE was counted as a single occurrence.

Osteonecrosis of the jaw was defined as radiographically documented necrosis of the mandible or associated structures with assessment by a VA dentist. Records from non-VA dental practices were not available for assessment. Documentation of dental assessment before the first dose of ZA and any assessments during treatment were recorded.

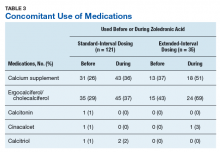

Medication use was assessed before and during ZA treatment. Number of ZA doses and reasons for any discontinuations were documented, as was concomitant use of calcium supplements, vitamin D supplements, calcitriol, paricalcitol, calcitonin, cinacalcet, and pamidronate.

The primary study outcome was observed difference in incidence of SREs between standard- and extended-interval dosing of ZA. Secondary outcomes included difference in incidence of ONJ as well as incidence of SREs and ONJ by disease subtype (MM, CaP).

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic data and assess prespecified outcomes. Differences in rates of SREs and ONJ between dosing interval groups were analyzed with the Pearson χ2 test. The predetermined a priori level of significance was .05.

Results

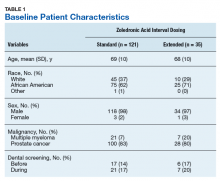

Of the 300 patients prescribed ZA at the Memphis VAMC, 177 were excluded (96 for indication,78 for receiving only 1 dose of ZA, 3 for not receiving any doses of ZA). The remaining 123 patients were stratified into a standard-interval dosing group (121) and an extended-interval dosing group (35). Of the 123 patients, 33 received both standard- and extended-interval dosing of ZA over the course of the study period and were included discretely in each group for the duration of each dosing strategy.

Pre-ZA dental screenings were documented in 14% of standard-interval patients and 17% of extended-interval patients, and during-ZA screenings were documented in 17% of standard-interval patients and 20% of extended-interval patients. Chi-square analysis revealed no significant difference in rates of dental screening before or during use of ZA.

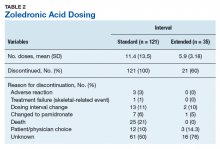

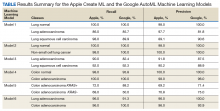

Standard-interval patients received a mean (SD) 11.4 (13.5) doses of ZA (range, 2-124). Extended-interval patients received a mean (SD) of 5.9 (3.18) doses (range, 2-14). All standard-interval patients had discontinued treatment at the time of the study, most commonly because of death or for an unknown reason. Sixty percent of extended-interval patients had discontinued treatment, most commonly because of patient/physician choice or for an unknown reason (Table 2).

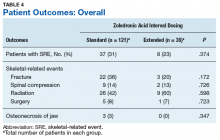

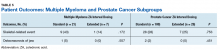

Skeletal-related events were observed in 31% of standard-interval patients and 23% of extended-interval patients. There were no statistically significant differences in SRE rates between groups (P = .374). The most common SRE in both groups was bone irradiation (42% and 60%, respectively), with no statistically significant difference in proportion between groups (Table 4).

Discussion

This retrospective review of patients with MM and CaP receiving ZA for bone metastasesfound no differences in the rates of SREs when ZA was dosed monthly vs every 3 months.

Earlier studies found that ZA can decrease SRE rates, but a major concern is that frequent, prolonged exposure to IV bisphosphonates may increase the risk of ONJ. No significant differences in ONJ rates existed between dosing groups, but all documented cases of ONJ occurred in the standard-interval group, suggesting a trend toward decreased incidence with an extension of the dosing interval.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Geriatric African American men comprised the majority of the study population, and patients with MM accounted for only 22% of included regimens, limiting external validity. Patient overlap between groups may have confounded the results. The retrospective design precluded the ability to control for confounding variables, such as concomitant medication use and medication adherence, and significant heterogeneity was noted in rates of adherence with ZA infusion schedules regardless of dosing group. Use of medications associated with increased risk of osteoporosis—including corticosteroids and proton pump inhibitors—was not assessed.

Assessment of ONJ incidence was limited by the lack of access to dental records from providers outside the VA. Many patients in this review were not eligible for VA dental benefits because of requirements involving time and service connection, a reimbursement measurement that reflects health conditions “incurred or aggravated during active military service.”18

The results of this study provide further support for extended-interval dosing of ZA as a potential method of increasing patient adherence and decreasing the possibility of adverse drug reactions without compromising therapeutic benefit. Further randomized controlled trials are needed to define the potential decrease in ONJ incidence.

Conclusion

In comparisons of standard- and extended-interval dosing of ZA, there was no difference in the incidence of skeletal-related events in veteran patients with bone metastases from MM or CaP.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2018. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2018.

2. Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al, eds. SEER Cancer Statistics Review (CSR), 1975-2014 [based on November 2016 SEER data submission posted to SEER website April 2017]. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2017. https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2014/. Accessed January 12, 2019.

3. Roodman GD. Pathogenesis of myeloma bone disease. Leukemia. 2009;23(3):435-441.

4. Sartor O, de Bono JS. Metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(7):645-657.

5. Drake MT, Clarke BL, Khosla S. Bisphosphonates: mechanism of action and role in clinical practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(9):1032-1045.

6. Zometa [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis; 2016.

7. Aredia [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis; 2011.

8. Berenson JR, Rosen LS, Howell A, et al. Zoledronic acid reduces skeletal-related events in patients with osteolytic metastases: a double-blind, randomized dose-response study [published correction appears in Cancer. 2001;91(10):1956]. Cancer. 2001;91(7):1191-1200.

9. Berenson JR, Lichtenstein A, Porter L, et al. Efficacy of pamidronate in reducing skeletal events in patients with advanced multiple myeloma. Myeloma Aredia Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(8):488-493.

10. Mhaskar R, Redzepovic J, Wheatley K, et al. Bisphosphonates in multiple myeloma: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(5):CD003188.

11. Wu S, Dahut WL, Gulley JL. The use of bisphosphonates in cancer patients. Acta Oncol. 2007;46(5):581-591.

12. Bamias A, Kastritis E, Bamia C, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer after treatment with bisphosphonates: incidence and risk factors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(34):8580-8587.

13. Anderson K, Ismaila N, Flynn PJ, et al. Role of bone-modifying agents in multiple myeloma: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(8):812-818.

14. National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Multiple Myeloma. Version 2.2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/myeloma.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2019.

15. National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Prostate Cancer. Version 4.2018. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2019.

16. Lacy MQ, Dispenzieri A, Gertz MA, et al. Mayo Clinic consensus statement for the use of bisphosphonates in multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(8):1047-1053.

17. Himelstein AL, Foster JC, Khatcheressian JL, et al. Effect of longer-interval vs. standard dosing of zoledronic acid on skeletal events in patients with bone metastases: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(1):48-58.

18. Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs, US Department of Veterans Affairs. Service connected disabilities. In: Federal Benefits for Veterans, Dependents, and Survivors. https://www.va.gov/opa/publications/benefits_book/benefits_chap02.asp. Published April 2015. Accessed May 22, 2018.

In patients with multiple myeloma and prostate cancer, extending the bisphosphonatedosing interval may help decrease medication-related morbidity without compromising therapeutic benefit.

In patients with multiple myeloma and prostate cancer, extending the bisphosphonatedosing interval may help decrease medication-related morbidity without compromising therapeutic benefit.

Bone pain is one of the most common causes of morbidity in multiple myeloma (MM) and metastatic prostate cancer (CaP). This pain originates with the underlying pathologic processes of the cancer and with downstream skeletal-related events (SREs). SREs—fractures, spinal cord compression, and irradiation or surgery performed in ≥ 1 bone sites—represent a significant health care burden, particularly given the incidence of the underlying malignancies. According to American Cancer Society statistics, CaP is the second most common cancer in American men, and MM the second most common hematologic malignancy, despite its relatively low overall lifetime risk.1,2 Regardless of the underlying malignancy, bisphosphonates are the cornerstone of SRE prevention, though the optimal dosing strategy is the subject of clinical debate.

Although similar in SRE incidence, MM and CaP have distinct pathophysiologic processes in the dysregulation of bone resorption. MM is a hematologic malignancy that increases the risk of SREs by osteoclast up-regulation, primarily through the RANK (receptor activator of nuclear factor α-B) signaling pathway.3 CaP is a solid tumor malignancy that metastasizes to bone. Dysregulation of the bone resorption or formation cycle and net bone loss are a result of endogenous osteoclast up-regulation in response to abnormal bone formation in osteoblastic bone metastases.4 Androgen-deprivation therapy, the cornerstone of CaP treatment, further predisposes CaP patients to osteoporosis and SREs.

Prevention of SREs is pharmacologically driven by bisphosphonates, which have antiresorptive effects on bone through promotion of osteoclast apoptosis.5 Two IV formulations, pamidronate and zoledronic acid (ZA), are US Food and Drug Administration approved for use in bone metastases from MM or solid tumors.6-10 Although generally well tolerated, bisphosphonates can cause osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ), an avascular death of bone tissue, particularly with prolonged use.11 With its documented incidence of 5% to 6.7% in bone metastasis, ONJ represents a significant morbidity risk in patients with MM and CaP who are treated with IV bisphosphonates.12

Investigators are exploring bisphosphonate dosing intervals to determine which is most appropriate in mitigating the risk of ONJ. Before 2006, bisphosphonates were consistently dosed once monthly in patients with MM or metastatic bone disease—a standard derived empirically rather than from comparative studies or compelling pharmacodynamic data.13-15 In a 2006 consensus statement, the Mayo Clinic issued an expert opinion recommendation for increasing the bisphosphonate dosing interval to every 3 months in patients with MM.16 The first objective evidence for the clinical applicability of extending the ZA dosing interval was reported by Himelstein and colleagues in 2017.17 The randomized clinical trial found no differences in SRE rates when ZA was dosed every 12 weeks,17 prompting a conditional recommendation for dosing interval extension in the American Society of Clinical Oncology MM treatment guidelines (2018).13 Because of the age and racial demographics of the patients in these studies, many questions remain unanswered.

For the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) population, the pharmacokinetic and dynamic differences imposed by age and race limit the applicability of the available data. However, in veterans with MM or CaP, extending the bisphosphonate dosing interval may help decrease medication-related morbidity (eg, ONJ, nephrotoxicity) without compromising therapeutic benefit. To this end at the Memphis VA Medical Center (VAMC), we assessed for differences in SRE rates by comparing outcomes of patients who received ZA in standard- vs extended-interval dosing.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the Computerized Patient Record System for veterans with MM or metastatic CaP treated with ZA at the Memphis VAMC. Study inclusion criteria were aged > 18 years and care provided by a Memphis VAMC oncologist between January 2003 and January 2018. The study was approved by the Memphis VAMC’s Institutional Review Board, and procedures were followed in accordance with the ethical standards of its committee on human experimentation.

Using Microsoft SQL 2016 (Redmond, WA), we performed a query to identify patients who were prescribed ZA during the study period. Exclusion criteria were ZA prescribed for an indication other than MM or CaP (ie, osteoporosis) and receipt of ≤ 1 dose of ZA. Once a list was compiled, patients were stratified by ZA dosing interval: standard (mean, every month) or extended (mean, every 3 months). Patients whose ZA dosing interval was changed during treatment were included as independent data points in each group.

Skeletal-related events included fractures, spinal compression, irradiation, and surgery. Fractures and spinal compression were pertinent in the presence of radiographic documentation (eg, X-ray, magnetic resonance imaging scan) during the period the patient received ZA or within 1 dosing interval of the last recorded ZA dose. Irradiation was defined as documented application of radiation therapy to ≥ 1 bone sites for palliation of pain or as an intervention in the setting of spinal compression. Surgery was defined as any procedure performed to correct a fracture or spinal compression. Each SRE was counted as a single occurrence.

Osteonecrosis of the jaw was defined as radiographically documented necrosis of the mandible or associated structures with assessment by a VA dentist. Records from non-VA dental practices were not available for assessment. Documentation of dental assessment before the first dose of ZA and any assessments during treatment were recorded.

Medication use was assessed before and during ZA treatment. Number of ZA doses and reasons for any discontinuations were documented, as was concomitant use of calcium supplements, vitamin D supplements, calcitriol, paricalcitol, calcitonin, cinacalcet, and pamidronate.

The primary study outcome was observed difference in incidence of SREs between standard- and extended-interval dosing of ZA. Secondary outcomes included difference in incidence of ONJ as well as incidence of SREs and ONJ by disease subtype (MM, CaP).

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic data and assess prespecified outcomes. Differences in rates of SREs and ONJ between dosing interval groups were analyzed with the Pearson χ2 test. The predetermined a priori level of significance was .05.

Results

Of the 300 patients prescribed ZA at the Memphis VAMC, 177 were excluded (96 for indication,78 for receiving only 1 dose of ZA, 3 for not receiving any doses of ZA). The remaining 123 patients were stratified into a standard-interval dosing group (121) and an extended-interval dosing group (35). Of the 123 patients, 33 received both standard- and extended-interval dosing of ZA over the course of the study period and were included discretely in each group for the duration of each dosing strategy.

Pre-ZA dental screenings were documented in 14% of standard-interval patients and 17% of extended-interval patients, and during-ZA screenings were documented in 17% of standard-interval patients and 20% of extended-interval patients. Chi-square analysis revealed no significant difference in rates of dental screening before or during use of ZA.

Standard-interval patients received a mean (SD) 11.4 (13.5) doses of ZA (range, 2-124). Extended-interval patients received a mean (SD) of 5.9 (3.18) doses (range, 2-14). All standard-interval patients had discontinued treatment at the time of the study, most commonly because of death or for an unknown reason. Sixty percent of extended-interval patients had discontinued treatment, most commonly because of patient/physician choice or for an unknown reason (Table 2).

Skeletal-related events were observed in 31% of standard-interval patients and 23% of extended-interval patients. There were no statistically significant differences in SRE rates between groups (P = .374). The most common SRE in both groups was bone irradiation (42% and 60%, respectively), with no statistically significant difference in proportion between groups (Table 4).

Discussion

This retrospective review of patients with MM and CaP receiving ZA for bone metastasesfound no differences in the rates of SREs when ZA was dosed monthly vs every 3 months.

Earlier studies found that ZA can decrease SRE rates, but a major concern is that frequent, prolonged exposure to IV bisphosphonates may increase the risk of ONJ. No significant differences in ONJ rates existed between dosing groups, but all documented cases of ONJ occurred in the standard-interval group, suggesting a trend toward decreased incidence with an extension of the dosing interval.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Geriatric African American men comprised the majority of the study population, and patients with MM accounted for only 22% of included regimens, limiting external validity. Patient overlap between groups may have confounded the results. The retrospective design precluded the ability to control for confounding variables, such as concomitant medication use and medication adherence, and significant heterogeneity was noted in rates of adherence with ZA infusion schedules regardless of dosing group. Use of medications associated with increased risk of osteoporosis—including corticosteroids and proton pump inhibitors—was not assessed.

Assessment of ONJ incidence was limited by the lack of access to dental records from providers outside the VA. Many patients in this review were not eligible for VA dental benefits because of requirements involving time and service connection, a reimbursement measurement that reflects health conditions “incurred or aggravated during active military service.”18

The results of this study provide further support for extended-interval dosing of ZA as a potential method of increasing patient adherence and decreasing the possibility of adverse drug reactions without compromising therapeutic benefit. Further randomized controlled trials are needed to define the potential decrease in ONJ incidence.

Conclusion

In comparisons of standard- and extended-interval dosing of ZA, there was no difference in the incidence of skeletal-related events in veteran patients with bone metastases from MM or CaP.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Bone pain is one of the most common causes of morbidity in multiple myeloma (MM) and metastatic prostate cancer (CaP). This pain originates with the underlying pathologic processes of the cancer and with downstream skeletal-related events (SREs). SREs—fractures, spinal cord compression, and irradiation or surgery performed in ≥ 1 bone sites—represent a significant health care burden, particularly given the incidence of the underlying malignancies. According to American Cancer Society statistics, CaP is the second most common cancer in American men, and MM the second most common hematologic malignancy, despite its relatively low overall lifetime risk.1,2 Regardless of the underlying malignancy, bisphosphonates are the cornerstone of SRE prevention, though the optimal dosing strategy is the subject of clinical debate.

Although similar in SRE incidence, MM and CaP have distinct pathophysiologic processes in the dysregulation of bone resorption. MM is a hematologic malignancy that increases the risk of SREs by osteoclast up-regulation, primarily through the RANK (receptor activator of nuclear factor α-B) signaling pathway.3 CaP is a solid tumor malignancy that metastasizes to bone. Dysregulation of the bone resorption or formation cycle and net bone loss are a result of endogenous osteoclast up-regulation in response to abnormal bone formation in osteoblastic bone metastases.4 Androgen-deprivation therapy, the cornerstone of CaP treatment, further predisposes CaP patients to osteoporosis and SREs.

Prevention of SREs is pharmacologically driven by bisphosphonates, which have antiresorptive effects on bone through promotion of osteoclast apoptosis.5 Two IV formulations, pamidronate and zoledronic acid (ZA), are US Food and Drug Administration approved for use in bone metastases from MM or solid tumors.6-10 Although generally well tolerated, bisphosphonates can cause osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ), an avascular death of bone tissue, particularly with prolonged use.11 With its documented incidence of 5% to 6.7% in bone metastasis, ONJ represents a significant morbidity risk in patients with MM and CaP who are treated with IV bisphosphonates.12

Investigators are exploring bisphosphonate dosing intervals to determine which is most appropriate in mitigating the risk of ONJ. Before 2006, bisphosphonates were consistently dosed once monthly in patients with MM or metastatic bone disease—a standard derived empirically rather than from comparative studies or compelling pharmacodynamic data.13-15 In a 2006 consensus statement, the Mayo Clinic issued an expert opinion recommendation for increasing the bisphosphonate dosing interval to every 3 months in patients with MM.16 The first objective evidence for the clinical applicability of extending the ZA dosing interval was reported by Himelstein and colleagues in 2017.17 The randomized clinical trial found no differences in SRE rates when ZA was dosed every 12 weeks,17 prompting a conditional recommendation for dosing interval extension in the American Society of Clinical Oncology MM treatment guidelines (2018).13 Because of the age and racial demographics of the patients in these studies, many questions remain unanswered.

For the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) population, the pharmacokinetic and dynamic differences imposed by age and race limit the applicability of the available data. However, in veterans with MM or CaP, extending the bisphosphonate dosing interval may help decrease medication-related morbidity (eg, ONJ, nephrotoxicity) without compromising therapeutic benefit. To this end at the Memphis VA Medical Center (VAMC), we assessed for differences in SRE rates by comparing outcomes of patients who received ZA in standard- vs extended-interval dosing.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the Computerized Patient Record System for veterans with MM or metastatic CaP treated with ZA at the Memphis VAMC. Study inclusion criteria were aged > 18 years and care provided by a Memphis VAMC oncologist between January 2003 and January 2018. The study was approved by the Memphis VAMC’s Institutional Review Board, and procedures were followed in accordance with the ethical standards of its committee on human experimentation.

Using Microsoft SQL 2016 (Redmond, WA), we performed a query to identify patients who were prescribed ZA during the study period. Exclusion criteria were ZA prescribed for an indication other than MM or CaP (ie, osteoporosis) and receipt of ≤ 1 dose of ZA. Once a list was compiled, patients were stratified by ZA dosing interval: standard (mean, every month) or extended (mean, every 3 months). Patients whose ZA dosing interval was changed during treatment were included as independent data points in each group.

Skeletal-related events included fractures, spinal compression, irradiation, and surgery. Fractures and spinal compression were pertinent in the presence of radiographic documentation (eg, X-ray, magnetic resonance imaging scan) during the period the patient received ZA or within 1 dosing interval of the last recorded ZA dose. Irradiation was defined as documented application of radiation therapy to ≥ 1 bone sites for palliation of pain or as an intervention in the setting of spinal compression. Surgery was defined as any procedure performed to correct a fracture or spinal compression. Each SRE was counted as a single occurrence.

Osteonecrosis of the jaw was defined as radiographically documented necrosis of the mandible or associated structures with assessment by a VA dentist. Records from non-VA dental practices were not available for assessment. Documentation of dental assessment before the first dose of ZA and any assessments during treatment were recorded.

Medication use was assessed before and during ZA treatment. Number of ZA doses and reasons for any discontinuations were documented, as was concomitant use of calcium supplements, vitamin D supplements, calcitriol, paricalcitol, calcitonin, cinacalcet, and pamidronate.

The primary study outcome was observed difference in incidence of SREs between standard- and extended-interval dosing of ZA. Secondary outcomes included difference in incidence of ONJ as well as incidence of SREs and ONJ by disease subtype (MM, CaP).

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic data and assess prespecified outcomes. Differences in rates of SREs and ONJ between dosing interval groups were analyzed with the Pearson χ2 test. The predetermined a priori level of significance was .05.

Results

Of the 300 patients prescribed ZA at the Memphis VAMC, 177 were excluded (96 for indication,78 for receiving only 1 dose of ZA, 3 for not receiving any doses of ZA). The remaining 123 patients were stratified into a standard-interval dosing group (121) and an extended-interval dosing group (35). Of the 123 patients, 33 received both standard- and extended-interval dosing of ZA over the course of the study period and were included discretely in each group for the duration of each dosing strategy.

Pre-ZA dental screenings were documented in 14% of standard-interval patients and 17% of extended-interval patients, and during-ZA screenings were documented in 17% of standard-interval patients and 20% of extended-interval patients. Chi-square analysis revealed no significant difference in rates of dental screening before or during use of ZA.

Standard-interval patients received a mean (SD) 11.4 (13.5) doses of ZA (range, 2-124). Extended-interval patients received a mean (SD) of 5.9 (3.18) doses (range, 2-14). All standard-interval patients had discontinued treatment at the time of the study, most commonly because of death or for an unknown reason. Sixty percent of extended-interval patients had discontinued treatment, most commonly because of patient/physician choice or for an unknown reason (Table 2).

Skeletal-related events were observed in 31% of standard-interval patients and 23% of extended-interval patients. There were no statistically significant differences in SRE rates between groups (P = .374). The most common SRE in both groups was bone irradiation (42% and 60%, respectively), with no statistically significant difference in proportion between groups (Table 4).

Discussion

This retrospective review of patients with MM and CaP receiving ZA for bone metastasesfound no differences in the rates of SREs when ZA was dosed monthly vs every 3 months.

Earlier studies found that ZA can decrease SRE rates, but a major concern is that frequent, prolonged exposure to IV bisphosphonates may increase the risk of ONJ. No significant differences in ONJ rates existed between dosing groups, but all documented cases of ONJ occurred in the standard-interval group, suggesting a trend toward decreased incidence with an extension of the dosing interval.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Geriatric African American men comprised the majority of the study population, and patients with MM accounted for only 22% of included regimens, limiting external validity. Patient overlap between groups may have confounded the results. The retrospective design precluded the ability to control for confounding variables, such as concomitant medication use and medication adherence, and significant heterogeneity was noted in rates of adherence with ZA infusion schedules regardless of dosing group. Use of medications associated with increased risk of osteoporosis—including corticosteroids and proton pump inhibitors—was not assessed.

Assessment of ONJ incidence was limited by the lack of access to dental records from providers outside the VA. Many patients in this review were not eligible for VA dental benefits because of requirements involving time and service connection, a reimbursement measurement that reflects health conditions “incurred or aggravated during active military service.”18

The results of this study provide further support for extended-interval dosing of ZA as a potential method of increasing patient adherence and decreasing the possibility of adverse drug reactions without compromising therapeutic benefit. Further randomized controlled trials are needed to define the potential decrease in ONJ incidence.

Conclusion

In comparisons of standard- and extended-interval dosing of ZA, there was no difference in the incidence of skeletal-related events in veteran patients with bone metastases from MM or CaP.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2018. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2018.

2. Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al, eds. SEER Cancer Statistics Review (CSR), 1975-2014 [based on November 2016 SEER data submission posted to SEER website April 2017]. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2017. https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2014/. Accessed January 12, 2019.

3. Roodman GD. Pathogenesis of myeloma bone disease. Leukemia. 2009;23(3):435-441.

4. Sartor O, de Bono JS. Metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(7):645-657.

5. Drake MT, Clarke BL, Khosla S. Bisphosphonates: mechanism of action and role in clinical practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(9):1032-1045.

6. Zometa [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis; 2016.

7. Aredia [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis; 2011.

8. Berenson JR, Rosen LS, Howell A, et al. Zoledronic acid reduces skeletal-related events in patients with osteolytic metastases: a double-blind, randomized dose-response study [published correction appears in Cancer. 2001;91(10):1956]. Cancer. 2001;91(7):1191-1200.

9. Berenson JR, Lichtenstein A, Porter L, et al. Efficacy of pamidronate in reducing skeletal events in patients with advanced multiple myeloma. Myeloma Aredia Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(8):488-493.

10. Mhaskar R, Redzepovic J, Wheatley K, et al. Bisphosphonates in multiple myeloma: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(5):CD003188.

11. Wu S, Dahut WL, Gulley JL. The use of bisphosphonates in cancer patients. Acta Oncol. 2007;46(5):581-591.

12. Bamias A, Kastritis E, Bamia C, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer after treatment with bisphosphonates: incidence and risk factors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(34):8580-8587.

13. Anderson K, Ismaila N, Flynn PJ, et al. Role of bone-modifying agents in multiple myeloma: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(8):812-818.

14. National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Multiple Myeloma. Version 2.2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/myeloma.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2019.

15. National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Prostate Cancer. Version 4.2018. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2019.

16. Lacy MQ, Dispenzieri A, Gertz MA, et al. Mayo Clinic consensus statement for the use of bisphosphonates in multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(8):1047-1053.

17. Himelstein AL, Foster JC, Khatcheressian JL, et al. Effect of longer-interval vs. standard dosing of zoledronic acid on skeletal events in patients with bone metastases: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(1):48-58.

18. Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs, US Department of Veterans Affairs. Service connected disabilities. In: Federal Benefits for Veterans, Dependents, and Survivors. https://www.va.gov/opa/publications/benefits_book/benefits_chap02.asp. Published April 2015. Accessed May 22, 2018.

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2018. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2018.

2. Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al, eds. SEER Cancer Statistics Review (CSR), 1975-2014 [based on November 2016 SEER data submission posted to SEER website April 2017]. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2017. https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2014/. Accessed January 12, 2019.

3. Roodman GD. Pathogenesis of myeloma bone disease. Leukemia. 2009;23(3):435-441.

4. Sartor O, de Bono JS. Metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(7):645-657.

5. Drake MT, Clarke BL, Khosla S. Bisphosphonates: mechanism of action and role in clinical practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(9):1032-1045.

6. Zometa [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis; 2016.

7. Aredia [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis; 2011.

8. Berenson JR, Rosen LS, Howell A, et al. Zoledronic acid reduces skeletal-related events in patients with osteolytic metastases: a double-blind, randomized dose-response study [published correction appears in Cancer. 2001;91(10):1956]. Cancer. 2001;91(7):1191-1200.

9. Berenson JR, Lichtenstein A, Porter L, et al. Efficacy of pamidronate in reducing skeletal events in patients with advanced multiple myeloma. Myeloma Aredia Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(8):488-493.

10. Mhaskar R, Redzepovic J, Wheatley K, et al. Bisphosphonates in multiple myeloma: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(5):CD003188.

11. Wu S, Dahut WL, Gulley JL. The use of bisphosphonates in cancer patients. Acta Oncol. 2007;46(5):581-591.

12. Bamias A, Kastritis E, Bamia C, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer after treatment with bisphosphonates: incidence and risk factors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(34):8580-8587.

13. Anderson K, Ismaila N, Flynn PJ, et al. Role of bone-modifying agents in multiple myeloma: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(8):812-818.

14. National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Multiple Myeloma. Version 2.2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/myeloma.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2019.

15. National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Prostate Cancer. Version 4.2018. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2019.

16. Lacy MQ, Dispenzieri A, Gertz MA, et al. Mayo Clinic consensus statement for the use of bisphosphonates in multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(8):1047-1053.

17. Himelstein AL, Foster JC, Khatcheressian JL, et al. Effect of longer-interval vs. standard dosing of zoledronic acid on skeletal events in patients with bone metastases: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(1):48-58.

18. Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs, US Department of Veterans Affairs. Service connected disabilities. In: Federal Benefits for Veterans, Dependents, and Survivors. https://www.va.gov/opa/publications/benefits_book/benefits_chap02.asp. Published April 2015. Accessed May 22, 2018.

Prostate Cancer Surveillance After Radiation Therapy in a National Delivery System (FULL)

Guideline concordance with PSA surveillance among veterans treated with definitiveradiation therapy was generally high, but opportunities may exist to improve surveillance among select groups.

Guidelines recommend prostate-specific antigen (PSA) surveillance among men treated with definitive radiation therapy (RT) for prostate cancer. Specifically, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends testing every 6 to 12 months for 5 years and annually thereafter (with no specific stopping period specified), while the American Urology Association recommends testing for at least 10 years, with the frequency to be determined by the risk of relapse and patient preferences for monitoring.1,2 Salvage treatments exist for men with localized recurrence identified early through PSA testing, so adherence to follow-up guidelines is important for quality prostate cancer survivorship care.1,2

However, few studies focus on adherence to PSA surveillance following radiation therapy. Posttreatment surveillance among surgical patients is generally high, but sociodemographic disparities exist. Racial and ethnic minorities and unmarried men are less likely to undergo guideline concordant surveillance than is the general population, potentially preventing effective salvage therapy.3,4 A recent Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) study on posttreatment surveillance included radiation therapy patients but did not examine the impact of younger age, concurrent androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), or treatment facility (ie, diagnosed and treated at the same vs different facilities, with the latter including a separate VA facility or the community) on surveillance patterns.5 The latter is particularly relevant given increasing efforts to coordinate care outside the VA delivery system supported by the 2018 VA Maintaining Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act. Furthermore, these patient, treatment, and delivery system factors may each uniquely contribute to whether patients receive guideline-recommended PSA surveillance after prostate cancer treatment.

For these reasons, we conducted a study to better understand determinants of adherence to guideline-recommended PSA surveillance among veterans undergoing definitive radiation therapy with or without concurrent ADT. Our study uniquely included both elderly and nonelderly patients as well as investigated relationships between treatment at or away from the diagnosing facility. Although we found high overall levels of adherence to PSA surveillance, our findings do offer insights into determinants associated with worse adherence and provide opportunities to improve prostate cancer survivorship care after RT.

Methods

This study population included men with biopsy-proven nonmetastatic incident prostate cancer diagnosed between January 2005 and December 2008, with follow-up through 2012, identified using the VA Central Cancer Registry. We included men who underwent definitive RT with or without concurrent ADT injections, determined using the VA pharmacy files. We excluded men with a prior diagnosis of prostate or other malignancy (given the presence of other malignancies might affect life expectancy and surveillance patterns), hospice enrollment within 30 days, diagnosis at autopsy, and those treated with radical prostatectomy. We extracted cancer registry data, including biopsy Gleason score, pretreatment PSA level, clinical tumor stage, and whether RT was delivered at the patient’s diagnosing facility. For the latter, we used data on radiation location coded by the tumor registrar. We also collected demographic information, including age at diagnosis, race, ethnicity, marital status, and ZIP code. We used diagnosis codes to determine Charlson comorbidity scores similar to prior studies.6-8

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome was receipt of guideline concordant annual PSA surveillance in the initial 5 years following RT. We used laboratory files within the VA Corporate Data Warehouse to identify the date and value for each PSA test after RT for the entire cohort. Specifically, we defined the surveillance period as 60 days after initiation of RT through December 31, 2012. We defined guideline concordance as receiving at least 1 PSA test for each 12-month period after RT.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize our cohort of veterans with prostate cancer treated with RT with or without concurrent ADT. To handle missing data, we performed multiple imputation, generating 10 imputations using all baseline clinical and demographic variables, year of diagnosis, and the regional VA network (ie, the Veterans Integrated Services Network [VISN]) for each patient.

Next, we calculated the annual guideline concordance rate for each year of follow-up for each patient, for the overall cohort, as well as by age, race/ethnicity, and concurrent ADT use. We examined bivariable relationships between guideline concordance and baseline demographic, clinical, and delivery system factors, including year of diagnosis and whether patients were treated at the diagnosing facility, using multilevel logistic regression modeling to account for clustering at the patient level.

Analyses were performed using Stata Version 15 (College Station, TX). We considered a 2-sided P value of < .05 as statistically significant. This study was approved by the VA Ann Arbor Health Care System Institution Review Board.

Results

We evaluated annual PSA surveillance for 15,538 men treated with RT with or without concurrent ADT (Table 1).

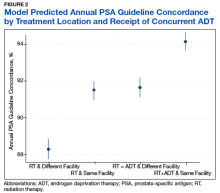

On unadjusted analysis, annual guideline concordance was less common among patients who were at the extremes of age, white, had Gleason 6 disease, PSA ≤ 10 ng/mL, did not receive concurrent ADT, and were treated away from their diagnosing facility (P < .05) (data not shown). We did find slight differences in patient characteristics based on whether patients were treated at their diagnosing facility (Table 2).

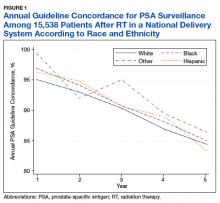

Overall, we found annual guideline concordance was initially very high, though declined slightly over the study period. For example, guideline concordance dropped from 96% in year 1 to 85% in year 5, with an average patient-level guideline concordance of 91% during the study period. We found minimal differences in annual surveillance after RT by race/ethnicity (Figure 1).

On multilevel multivariable analysis to adjust for clustering at the patient level, we found that race and PSA level were no longer significant predictors of annual surveillance (Table 3).

Discussion

We investigated adherence to guideline-recommended annual surveillance PSA testing in a national cohort of veterans treated with definitive RT for prostate cancer. We found guideline concordance was initially high and decreased slightly over time. We also found guideline concordance with PSA surveillance varied based on a number of clinical and delivery system factors, including marital status, rurality, receipt of concurrent ADT, as well as whether the veteran was treated at his diagnosing facility. Taken together, these overall results are promising, however, also point to unique considerations for some patient groups and potentially those treated in the community.

Our finding of lower guideline concordance among nonmarried patients is consistent with prior research, including our study of patients undergoing surgery for prostate cancer.4 Addressing surveillance in this population is important, as they may have less social support than do their married counterparts. We also found surveillance was lower at the extremes of age, which may be appropriate in elderly patients with limited life expectancy but is concerning for younger men with low competing mortality risks.7 Future work should explore whether younger patients experience barriers to care, including employment challenges, as these men are at greatest risk of cancer progression if recurrence goes undetected.

Although rural patients are less likely to undergo definitive prostate cancer treatment, possibly reflecting barriers to care, in our study, surveillance was actually higher among this population than that for urban patients.9 This could reflect the VA’s success in connecting rural patients to appropriate services despite travel distances to maintain quality of cancer care.10 Given annual PSA surveillance is relatively infrequent and not particularly resource intensive, these high surveillance rates might not apply to patients with cancers who need more frequent survivorship care, such as those with head and neck cancer. Future work should examine why surveillance rates among urban patients might be slightly lower, as living in a metropolitan area does not equate to the absence of barriers to survivorship care, especially for veterans who may not be able to take time off from work or have transportation barriers.

We found guideline concordance was higher among patients with higher Gleason scores, which is important given their higher likelihood of failure. However, low- and intermediate-risk patients also are at risk for treatment failure, so annual PSA surveillance should be optimized in this population unless future studies support the safety and feasibility of less frequent surveillance.10-13 Our finding of increased surveillance in patients who receive concurrent ADT may relate to the increased frequency of survivorship care given the need for injections, often every 3 to 6 months. Future studies might examine whether surveillance decreases in this population once they complete their short or long-term ADT, typically given for a maximum of 3 years.

A particularly relevant finding given recent VA policy changes includes lower guideline concordance for patients receiving RT at a different facility than where they were diagnosed. One possible explanation is that a proportion of patients treated outside of their home facilities use Medicare or private insurance and may have surveillance performed outside of the VA, which would not have been captured in our study.14 However, it remains plausible that there are challenges related to coordination and fragmentation of survivorship care for veterans who receive care at separate VA facilities or receive their initial treatment in the community.15 Future studies can help quantify how much this difference is driven by diagnosis and treatment at separate VA sites vs treatment outside of the VA, as different strategies might be necessary to improve surveillance in these 2 populations. Moreover, electronic health record-based tracking has been proposed as a strategy to identify patients who have not received guideline concordant PSA surveillance.14 This strategy may help increase guideline concordance regardless of initial treatment location if VA survivorship care is intended.

Although our study examined receipt of PSA testing, it did not examine whether patients are physically seen back in radiation oncology clinics, or whether their PSAs have been reviewed by radiation oncology providers. Although many surgical patients return to primary care providers for PSA surveillance, surveillance after RT is more complex and likely best managed in the initial years by radiation oncologists. Unlike the postoperative setting in which the definition of PSA failure is straightforward at > 0.2 ng/mL, the definition of treatment failure after RT is more complicated as described below.

For patients who did not receive concurrent ADT, failure is defined as a PSA nadir + 2 ng/mL, which first requires establishing the nadir using the first few postradiation PSA values.15 It becomes even more complex in the setting of ADT as it causes PSA suppression even in the absence of RT due to testosterone suppression.2 At the conclusion of ADT (short term 4-6 months or long term 18-36 months), the PSA may rise as testosterone recovers.15,16 This is not necessarily indicative of treatment failure, as some normal PSA-producing prostatic tissue may remain after treatment. Given these complexities, ongoing survivorship care with radiation oncology is recommended at least in the short term.

Physical visits are a challenge for some patients undergoing prostate cancer surveillance after treatment. Therefore, exploring the safety and feasibility of automated PSA tracking15 and strategies for increasing utilization of telemedicine, including clinical video telehealth appointments that are already used for survivorship and other urologic care in a number of VA clinics, represents opportunities to systematically provide highest quality survivorship care in VA.17,18

Conclusion

Most veterans receive guideline concordant PSA surveillance after RT for prostate cancer. Nonetheless, at the beginning of treatment, providers should screen veterans for risk factors for loss to follow-up (eg, care at a different or non-VA facility), discuss geographic, financial, and other barriers, and plan to leverage existing VA resources (eg, travel support) to continue to achieve high-quality PSA surveillance and survivorship care. Future research should investigate ways to take advantage of the VA’s robust electronic health record system and telemedicine infrastructure to further optimize prostate cancer survivorship care and PSA surveillance particularly among vulnerable patient groups and those treated outside of their diagnosing facility.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: VA HSR&D Career Development Award: 2 (CDA 12−171) and NCI R37 R37CA222885 (TAS).

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies.

1. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: prostate cancer v4.2018. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf. Updated August 15, 2018. Accessed January 23, 2019.

2. Sanda MG, Chen RC, Crispino T, et al. Clinically localized prostate cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO guideline. https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/prostate-cancer-clinically-localized-(2017). Published 2017. Accessed January 22,2019.

3. Zeliadt SB, Penson DF, Albertsen PC, Concato J, Etzioni RD. Race independently predicts prostate specific antigen testing frequency following a prostate carcinoma diagnosis. Cancer. 2003;98(3):496-503.

4. Trantham LC, Nielsen ME, Mobley LR, Wheeler SB, Carpenter WR, Biddle AK. Use of prostate-specific antigen testing as a disease surveillance tool following radical prostatectomy. Cancer. 2013;119(19):3523-3530.

5. Shi Y, Fung KZ, John Boscardin W, et al. Individualizing PSA monitoring among older prostate cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):602-604.

6. Chapman C, Burns J, Caram M, Zaslavsky A, Tsodikov A, Skolarus TA. Multilevel predictors of surveillance PSA guideline concordance after radical prostatectomy: a national Veterans Affairs study. Paper presented at: Association of VA Hematology/Oncology Annual Meeting;

September 28-30, 2018; Chicago, IL. Abstract 34. https://www.mdedge.com/fedprac/avaho/article/175094/prostate-cancer/multilevel-predictors-surveillance-psa-guideline. Accessed January 22, 2019.

7. Kirk PS, Borza T, Caram MEV, et al. Characterising potential bone scan overuse amongst men treated with radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2018. [Epub ahead of print.]

8. Kirk PS, Borza T, Shahinian VB, et al. The implications of baseline bone-health assessment at initiation of androgen-deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2018;121(4):558-564.

9. Baldwin LM, Andrilla CH, Porter MP, Rosenblatt RA, Patel S, Doescher MP. Treatment of early-stage prostate cancer among rural and urban patients. Cancer. 2013;119(16):3067-3075.

10. Skolarus TA, Chan S, Shelton JB, et al. Quality of prostate cancer care among rural men in the Veterans Health Administration. Cancer. 2013;119(20):3629-3635.

11. Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, et al; ProtecT Study Group. 10-year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(15):1415-1424.

12. Michalski JM, Moughan J, Purdy J, et al. Effect of standard vs dose-escalated radiation therapy for patients with intermediate-risk prostate cancer: the NRG Oncology RTOG 0126 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol.2018;4(6):e180039.

13. Chang MG, DeSotto K, Taibi P, Troeschel S. Development of a PSA tracking system for patients with prostate cancer following definitive radiotherapy to enhance rural health. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl 2):39-39.

14. Skolarus TA, Zhang Y, Hollenbeck BK. Understanding fragmentation of prostate cancer survivorship care: implications for cost and quality. Cancer. 2012;118(11):2837-2845.

15. Roach M, 3rd, Hanks G, Thames H Jr, et al. Defining biochemical failure following radiotherapy with or without hormonal therapy in men with clinically localized prostate cancer: recommendations of the RTOG-ASTRO Phoenix Consensus Conference. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65(4):965-974.

16. Buyyounouski MK, Hanlon AL, Horwitz EM, Uzzo RG, Pollack A. Biochemical failure and the temporal kinetics of prostate-specific antigen after radiation therapy with androgen deprivation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61(5):1291-1298.

17. Chu S, Boxer R, Madison P, et al. Veterans Affairs telemedicine: bringing urologic care to remote clinics. Urology. 2015;86(2):255-260.

18. Safir IJ, Gabale S, David SA, et al. Implementation of a tele-urology program for outpatient hematuria referrals: initial results and patient satisfaction. Urology. 2016;97:33-39.

Guideline concordance with PSA surveillance among veterans treated with definitiveradiation therapy was generally high, but opportunities may exist to improve surveillance among select groups.

Guideline concordance with PSA surveillance among veterans treated with definitiveradiation therapy was generally high, but opportunities may exist to improve surveillance among select groups.

Guidelines recommend prostate-specific antigen (PSA) surveillance among men treated with definitive radiation therapy (RT) for prostate cancer. Specifically, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends testing every 6 to 12 months for 5 years and annually thereafter (with no specific stopping period specified), while the American Urology Association recommends testing for at least 10 years, with the frequency to be determined by the risk of relapse and patient preferences for monitoring.1,2 Salvage treatments exist for men with localized recurrence identified early through PSA testing, so adherence to follow-up guidelines is important for quality prostate cancer survivorship care.1,2

However, few studies focus on adherence to PSA surveillance following radiation therapy. Posttreatment surveillance among surgical patients is generally high, but sociodemographic disparities exist. Racial and ethnic minorities and unmarried men are less likely to undergo guideline concordant surveillance than is the general population, potentially preventing effective salvage therapy.3,4 A recent Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) study on posttreatment surveillance included radiation therapy patients but did not examine the impact of younger age, concurrent androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), or treatment facility (ie, diagnosed and treated at the same vs different facilities, with the latter including a separate VA facility or the community) on surveillance patterns.5 The latter is particularly relevant given increasing efforts to coordinate care outside the VA delivery system supported by the 2018 VA Maintaining Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act. Furthermore, these patient, treatment, and delivery system factors may each uniquely contribute to whether patients receive guideline-recommended PSA surveillance after prostate cancer treatment.

For these reasons, we conducted a study to better understand determinants of adherence to guideline-recommended PSA surveillance among veterans undergoing definitive radiation therapy with or without concurrent ADT. Our study uniquely included both elderly and nonelderly patients as well as investigated relationships between treatment at or away from the diagnosing facility. Although we found high overall levels of adherence to PSA surveillance, our findings do offer insights into determinants associated with worse adherence and provide opportunities to improve prostate cancer survivorship care after RT.

Methods

This study population included men with biopsy-proven nonmetastatic incident prostate cancer diagnosed between January 2005 and December 2008, with follow-up through 2012, identified using the VA Central Cancer Registry. We included men who underwent definitive RT with or without concurrent ADT injections, determined using the VA pharmacy files. We excluded men with a prior diagnosis of prostate or other malignancy (given the presence of other malignancies might affect life expectancy and surveillance patterns), hospice enrollment within 30 days, diagnosis at autopsy, and those treated with radical prostatectomy. We extracted cancer registry data, including biopsy Gleason score, pretreatment PSA level, clinical tumor stage, and whether RT was delivered at the patient’s diagnosing facility. For the latter, we used data on radiation location coded by the tumor registrar. We also collected demographic information, including age at diagnosis, race, ethnicity, marital status, and ZIP code. We used diagnosis codes to determine Charlson comorbidity scores similar to prior studies.6-8

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome was receipt of guideline concordant annual PSA surveillance in the initial 5 years following RT. We used laboratory files within the VA Corporate Data Warehouse to identify the date and value for each PSA test after RT for the entire cohort. Specifically, we defined the surveillance period as 60 days after initiation of RT through December 31, 2012. We defined guideline concordance as receiving at least 1 PSA test for each 12-month period after RT.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize our cohort of veterans with prostate cancer treated with RT with or without concurrent ADT. To handle missing data, we performed multiple imputation, generating 10 imputations using all baseline clinical and demographic variables, year of diagnosis, and the regional VA network (ie, the Veterans Integrated Services Network [VISN]) for each patient.

Next, we calculated the annual guideline concordance rate for each year of follow-up for each patient, for the overall cohort, as well as by age, race/ethnicity, and concurrent ADT use. We examined bivariable relationships between guideline concordance and baseline demographic, clinical, and delivery system factors, including year of diagnosis and whether patients were treated at the diagnosing facility, using multilevel logistic regression modeling to account for clustering at the patient level.

Analyses were performed using Stata Version 15 (College Station, TX). We considered a 2-sided P value of < .05 as statistically significant. This study was approved by the VA Ann Arbor Health Care System Institution Review Board.

Results

We evaluated annual PSA surveillance for 15,538 men treated with RT with or without concurrent ADT (Table 1).

On unadjusted analysis, annual guideline concordance was less common among patients who were at the extremes of age, white, had Gleason 6 disease, PSA ≤ 10 ng/mL, did not receive concurrent ADT, and were treated away from their diagnosing facility (P < .05) (data not shown). We did find slight differences in patient characteristics based on whether patients were treated at their diagnosing facility (Table 2).

Overall, we found annual guideline concordance was initially very high, though declined slightly over the study period. For example, guideline concordance dropped from 96% in year 1 to 85% in year 5, with an average patient-level guideline concordance of 91% during the study period. We found minimal differences in annual surveillance after RT by race/ethnicity (Figure 1).

On multilevel multivariable analysis to adjust for clustering at the patient level, we found that race and PSA level were no longer significant predictors of annual surveillance (Table 3).

Discussion

We investigated adherence to guideline-recommended annual surveillance PSA testing in a national cohort of veterans treated with definitive RT for prostate cancer. We found guideline concordance was initially high and decreased slightly over time. We also found guideline concordance with PSA surveillance varied based on a number of clinical and delivery system factors, including marital status, rurality, receipt of concurrent ADT, as well as whether the veteran was treated at his diagnosing facility. Taken together, these overall results are promising, however, also point to unique considerations for some patient groups and potentially those treated in the community.

Our finding of lower guideline concordance among nonmarried patients is consistent with prior research, including our study of patients undergoing surgery for prostate cancer.4 Addressing surveillance in this population is important, as they may have less social support than do their married counterparts. We also found surveillance was lower at the extremes of age, which may be appropriate in elderly patients with limited life expectancy but is concerning for younger men with low competing mortality risks.7 Future work should explore whether younger patients experience barriers to care, including employment challenges, as these men are at greatest risk of cancer progression if recurrence goes undetected.

Although rural patients are less likely to undergo definitive prostate cancer treatment, possibly reflecting barriers to care, in our study, surveillance was actually higher among this population than that for urban patients.9 This could reflect the VA’s success in connecting rural patients to appropriate services despite travel distances to maintain quality of cancer care.10 Given annual PSA surveillance is relatively infrequent and not particularly resource intensive, these high surveillance rates might not apply to patients with cancers who need more frequent survivorship care, such as those with head and neck cancer. Future work should examine why surveillance rates among urban patients might be slightly lower, as living in a metropolitan area does not equate to the absence of barriers to survivorship care, especially for veterans who may not be able to take time off from work or have transportation barriers.

We found guideline concordance was higher among patients with higher Gleason scores, which is important given their higher likelihood of failure. However, low- and intermediate-risk patients also are at risk for treatment failure, so annual PSA surveillance should be optimized in this population unless future studies support the safety and feasibility of less frequent surveillance.10-13 Our finding of increased surveillance in patients who receive concurrent ADT may relate to the increased frequency of survivorship care given the need for injections, often every 3 to 6 months. Future studies might examine whether surveillance decreases in this population once they complete their short or long-term ADT, typically given for a maximum of 3 years.

A particularly relevant finding given recent VA policy changes includes lower guideline concordance for patients receiving RT at a different facility than where they were diagnosed. One possible explanation is that a proportion of patients treated outside of their home facilities use Medicare or private insurance and may have surveillance performed outside of the VA, which would not have been captured in our study.14 However, it remains plausible that there are challenges related to coordination and fragmentation of survivorship care for veterans who receive care at separate VA facilities or receive their initial treatment in the community.15 Future studies can help quantify how much this difference is driven by diagnosis and treatment at separate VA sites vs treatment outside of the VA, as different strategies might be necessary to improve surveillance in these 2 populations. Moreover, electronic health record-based tracking has been proposed as a strategy to identify patients who have not received guideline concordant PSA surveillance.14 This strategy may help increase guideline concordance regardless of initial treatment location if VA survivorship care is intended.

Although our study examined receipt of PSA testing, it did not examine whether patients are physically seen back in radiation oncology clinics, or whether their PSAs have been reviewed by radiation oncology providers. Although many surgical patients return to primary care providers for PSA surveillance, surveillance after RT is more complex and likely best managed in the initial years by radiation oncologists. Unlike the postoperative setting in which the definition of PSA failure is straightforward at > 0.2 ng/mL, the definition of treatment failure after RT is more complicated as described below.

For patients who did not receive concurrent ADT, failure is defined as a PSA nadir + 2 ng/mL, which first requires establishing the nadir using the first few postradiation PSA values.15 It becomes even more complex in the setting of ADT as it causes PSA suppression even in the absence of RT due to testosterone suppression.2 At the conclusion of ADT (short term 4-6 months or long term 18-36 months), the PSA may rise as testosterone recovers.15,16 This is not necessarily indicative of treatment failure, as some normal PSA-producing prostatic tissue may remain after treatment. Given these complexities, ongoing survivorship care with radiation oncology is recommended at least in the short term.

Physical visits are a challenge for some patients undergoing prostate cancer surveillance after treatment. Therefore, exploring the safety and feasibility of automated PSA tracking15 and strategies for increasing utilization of telemedicine, including clinical video telehealth appointments that are already used for survivorship and other urologic care in a number of VA clinics, represents opportunities to systematically provide highest quality survivorship care in VA.17,18

Conclusion

Most veterans receive guideline concordant PSA surveillance after RT for prostate cancer. Nonetheless, at the beginning of treatment, providers should screen veterans for risk factors for loss to follow-up (eg, care at a different or non-VA facility), discuss geographic, financial, and other barriers, and plan to leverage existing VA resources (eg, travel support) to continue to achieve high-quality PSA surveillance and survivorship care. Future research should investigate ways to take advantage of the VA’s robust electronic health record system and telemedicine infrastructure to further optimize prostate cancer survivorship care and PSA surveillance particularly among vulnerable patient groups and those treated outside of their diagnosing facility.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: VA HSR&D Career Development Award: 2 (CDA 12−171) and NCI R37 R37CA222885 (TAS).

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies.

Guidelines recommend prostate-specific antigen (PSA) surveillance among men treated with definitive radiation therapy (RT) for prostate cancer. Specifically, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends testing every 6 to 12 months for 5 years and annually thereafter (with no specific stopping period specified), while the American Urology Association recommends testing for at least 10 years, with the frequency to be determined by the risk of relapse and patient preferences for monitoring.1,2 Salvage treatments exist for men with localized recurrence identified early through PSA testing, so adherence to follow-up guidelines is important for quality prostate cancer survivorship care.1,2

However, few studies focus on adherence to PSA surveillance following radiation therapy. Posttreatment surveillance among surgical patients is generally high, but sociodemographic disparities exist. Racial and ethnic minorities and unmarried men are less likely to undergo guideline concordant surveillance than is the general population, potentially preventing effective salvage therapy.3,4 A recent Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) study on posttreatment surveillance included radiation therapy patients but did not examine the impact of younger age, concurrent androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), or treatment facility (ie, diagnosed and treated at the same vs different facilities, with the latter including a separate VA facility or the community) on surveillance patterns.5 The latter is particularly relevant given increasing efforts to coordinate care outside the VA delivery system supported by the 2018 VA Maintaining Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act. Furthermore, these patient, treatment, and delivery system factors may each uniquely contribute to whether patients receive guideline-recommended PSA surveillance after prostate cancer treatment.

For these reasons, we conducted a study to better understand determinants of adherence to guideline-recommended PSA surveillance among veterans undergoing definitive radiation therapy with or without concurrent ADT. Our study uniquely included both elderly and nonelderly patients as well as investigated relationships between treatment at or away from the diagnosing facility. Although we found high overall levels of adherence to PSA surveillance, our findings do offer insights into determinants associated with worse adherence and provide opportunities to improve prostate cancer survivorship care after RT.

Methods

This study population included men with biopsy-proven nonmetastatic incident prostate cancer diagnosed between January 2005 and December 2008, with follow-up through 2012, identified using the VA Central Cancer Registry. We included men who underwent definitive RT with or without concurrent ADT injections, determined using the VA pharmacy files. We excluded men with a prior diagnosis of prostate or other malignancy (given the presence of other malignancies might affect life expectancy and surveillance patterns), hospice enrollment within 30 days, diagnosis at autopsy, and those treated with radical prostatectomy. We extracted cancer registry data, including biopsy Gleason score, pretreatment PSA level, clinical tumor stage, and whether RT was delivered at the patient’s diagnosing facility. For the latter, we used data on radiation location coded by the tumor registrar. We also collected demographic information, including age at diagnosis, race, ethnicity, marital status, and ZIP code. We used diagnosis codes to determine Charlson comorbidity scores similar to prior studies.6-8

Primary Outcome