User login

Israel approves ponatinib for CML, Ph+ ALL

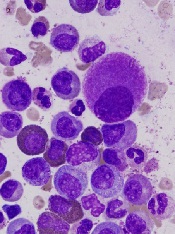

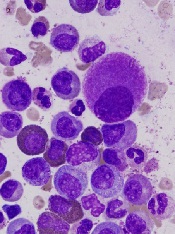

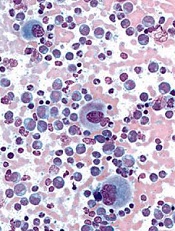

Photo courtesy of the US FDA

The Israeli Ministry of Health has granted regulatory approval for the kinase inhibitor ponatinib (Iclusig) to treat certain adults with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) or Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL).

The drug can now be used to treat adults with any phase of CML who have the T315I mutation or are resistant to/cannot tolerate dasatinib or nilotinib and for whom subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate.

Ponatinib is also approved to treat patients with Ph+ ALL who have the T315I mutation or are resistant to/cannot tolerate dasatinib and for whom subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate.

Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing ponatinib, said the drug should be available in Israel in the second quarter of 2015.

Trial results

The Ministry of Health’s decision to approve ponatinib was based on results from the phase 2 PACE trial, which included patients with CML or Ph+ ALL who were resistant to or intolerant of prior tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy, or who had the T315I mutation.

The median follow-up times were 15.3 months in chronic-phase CML patients, 15.8 months in accelerated-phase CML patients, and 6.2 months in patients with blast-phase CML or Ph+ ALL.

In chronic-phase CML, the primary endpoint was major cytogenetic response, and it occurred in 56% of patients. Among chronic-phase patients with the T315I mutation, 70% achieved a major cytogenetic response. Among patients who had failed treatment with dasatinib or nilotinib, 51% achieved a major cytogenetic response.

In accelerated-phase CML, the primary endpoint was major hematologic response. This occurred in 57% of all patients in this group, 50% of patients with the T315I mutation, and 58% of patients who had failed treatment with dasatinib or nilotinib.

The primary endpoint was major hematologic response in blast-phase CML/Ph+ ALL as well. Thirty-four percent of all patients in this group met this endpoint, as did 33% of patients with the T315I mutation and 35% of patients who had failed treatment with dasatinib or nilotinib.

Common non-hematologic adverse events included rash (38%), abdominal pain (38%), headache (35%), dry skin (35%), constipation (34%), fatigue (27%), pyrexia (27%), nausea (26%), arthralgia (25%), hypertension (21%), increased lipase (19%), and increased amylase (7%).

Hematologic events of any grade included thrombocytopenia (42%), neutropenia (24%), and anemia (20%). Serious adverse events of arterial thromboembolism, including arterial stenosis, occurred in patients with cardiovascular risk factors.

Safety issues

Extended follow-up data from the PACE trial, collected in 2013, suggested ponatinib can increase the risk of thrombotic events. When these data came to light, officials in the European Union and the US, where ponatinib had already been approved, began to investigate the drug.

Ponatinib was pulled from the US market for a little over 2 months, and trials of the drug were placed on partial hold while the Food and Drug Administration evaluated the drug’s safety. Ponatinib went back on the market in January 2014, with new safety measures in place.

The drug was not pulled from the market in the European Union, but the European Medicine’s Agency released recommendations for safer use of ponatinib. The Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use reviewed data on ponatinib and decided the drug’s benefits outweigh its risks. ![]()

Photo courtesy of the US FDA

The Israeli Ministry of Health has granted regulatory approval for the kinase inhibitor ponatinib (Iclusig) to treat certain adults with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) or Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL).

The drug can now be used to treat adults with any phase of CML who have the T315I mutation or are resistant to/cannot tolerate dasatinib or nilotinib and for whom subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate.

Ponatinib is also approved to treat patients with Ph+ ALL who have the T315I mutation or are resistant to/cannot tolerate dasatinib and for whom subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate.

Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing ponatinib, said the drug should be available in Israel in the second quarter of 2015.

Trial results

The Ministry of Health’s decision to approve ponatinib was based on results from the phase 2 PACE trial, which included patients with CML or Ph+ ALL who were resistant to or intolerant of prior tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy, or who had the T315I mutation.

The median follow-up times were 15.3 months in chronic-phase CML patients, 15.8 months in accelerated-phase CML patients, and 6.2 months in patients with blast-phase CML or Ph+ ALL.

In chronic-phase CML, the primary endpoint was major cytogenetic response, and it occurred in 56% of patients. Among chronic-phase patients with the T315I mutation, 70% achieved a major cytogenetic response. Among patients who had failed treatment with dasatinib or nilotinib, 51% achieved a major cytogenetic response.

In accelerated-phase CML, the primary endpoint was major hematologic response. This occurred in 57% of all patients in this group, 50% of patients with the T315I mutation, and 58% of patients who had failed treatment with dasatinib or nilotinib.

The primary endpoint was major hematologic response in blast-phase CML/Ph+ ALL as well. Thirty-four percent of all patients in this group met this endpoint, as did 33% of patients with the T315I mutation and 35% of patients who had failed treatment with dasatinib or nilotinib.

Common non-hematologic adverse events included rash (38%), abdominal pain (38%), headache (35%), dry skin (35%), constipation (34%), fatigue (27%), pyrexia (27%), nausea (26%), arthralgia (25%), hypertension (21%), increased lipase (19%), and increased amylase (7%).

Hematologic events of any grade included thrombocytopenia (42%), neutropenia (24%), and anemia (20%). Serious adverse events of arterial thromboembolism, including arterial stenosis, occurred in patients with cardiovascular risk factors.

Safety issues

Extended follow-up data from the PACE trial, collected in 2013, suggested ponatinib can increase the risk of thrombotic events. When these data came to light, officials in the European Union and the US, where ponatinib had already been approved, began to investigate the drug.

Ponatinib was pulled from the US market for a little over 2 months, and trials of the drug were placed on partial hold while the Food and Drug Administration evaluated the drug’s safety. Ponatinib went back on the market in January 2014, with new safety measures in place.

The drug was not pulled from the market in the European Union, but the European Medicine’s Agency released recommendations for safer use of ponatinib. The Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use reviewed data on ponatinib and decided the drug’s benefits outweigh its risks. ![]()

Photo courtesy of the US FDA

The Israeli Ministry of Health has granted regulatory approval for the kinase inhibitor ponatinib (Iclusig) to treat certain adults with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) or Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL).

The drug can now be used to treat adults with any phase of CML who have the T315I mutation or are resistant to/cannot tolerate dasatinib or nilotinib and for whom subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate.

Ponatinib is also approved to treat patients with Ph+ ALL who have the T315I mutation or are resistant to/cannot tolerate dasatinib and for whom subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate.

Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing ponatinib, said the drug should be available in Israel in the second quarter of 2015.

Trial results

The Ministry of Health’s decision to approve ponatinib was based on results from the phase 2 PACE trial, which included patients with CML or Ph+ ALL who were resistant to or intolerant of prior tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy, or who had the T315I mutation.

The median follow-up times were 15.3 months in chronic-phase CML patients, 15.8 months in accelerated-phase CML patients, and 6.2 months in patients with blast-phase CML or Ph+ ALL.

In chronic-phase CML, the primary endpoint was major cytogenetic response, and it occurred in 56% of patients. Among chronic-phase patients with the T315I mutation, 70% achieved a major cytogenetic response. Among patients who had failed treatment with dasatinib or nilotinib, 51% achieved a major cytogenetic response.

In accelerated-phase CML, the primary endpoint was major hematologic response. This occurred in 57% of all patients in this group, 50% of patients with the T315I mutation, and 58% of patients who had failed treatment with dasatinib or nilotinib.

The primary endpoint was major hematologic response in blast-phase CML/Ph+ ALL as well. Thirty-four percent of all patients in this group met this endpoint, as did 33% of patients with the T315I mutation and 35% of patients who had failed treatment with dasatinib or nilotinib.

Common non-hematologic adverse events included rash (38%), abdominal pain (38%), headache (35%), dry skin (35%), constipation (34%), fatigue (27%), pyrexia (27%), nausea (26%), arthralgia (25%), hypertension (21%), increased lipase (19%), and increased amylase (7%).

Hematologic events of any grade included thrombocytopenia (42%), neutropenia (24%), and anemia (20%). Serious adverse events of arterial thromboembolism, including arterial stenosis, occurred in patients with cardiovascular risk factors.

Safety issues

Extended follow-up data from the PACE trial, collected in 2013, suggested ponatinib can increase the risk of thrombotic events. When these data came to light, officials in the European Union and the US, where ponatinib had already been approved, began to investigate the drug.

Ponatinib was pulled from the US market for a little over 2 months, and trials of the drug were placed on partial hold while the Food and Drug Administration evaluated the drug’s safety. Ponatinib went back on the market in January 2014, with new safety measures in place.

The drug was not pulled from the market in the European Union, but the European Medicine’s Agency released recommendations for safer use of ponatinib. The Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use reviewed data on ponatinib and decided the drug’s benefits outweigh its risks. ![]()

Skiing accident claims life of leukemia expert

Photo courtesy of RPCI

Meir Wetzler, MD, Chief of the Leukemia Section at the Roswell Park Cancer Institute (RPCI) in Buffalo, New York, has died at the age of 60.

Dr Wetzler passed away on February 23, in a Denver, Colorado, hospital a little more than 2 weeks after a skiing accident.

He was nationally prominent in his field and served on the Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia (CML) Treatment Committee of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, helping set the standard of care for CML patients.

Originally from Israel, Dr Wetzler earned his medical degree at Hebrew University’s Hadassah Medical School in Jerusalem and did his residency in internal medicine at Kaplan Hospital in Rehovot before coming to the US.

From 1988 to 1992, he served 2 fellowships—in clinical immunology/biologic therapy and medical oncology—at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas. He joined the Leukemia Division of RPCI in 1994.

Dr Wetzler’s colleagues said he worked tirelessly with cooperative groups and pharmaceutical companies to attract new trials to RPCI for the benefit of his patients.

“He gave a piece of himself in everything he did, from his research to his care for patients to his interactions with his team of colleagues,” said Kara Eaton-Weaver, RPCI’s Executive Director of the Patient and Family Experience. “Meir was a transformational leader who built a culture of empathy, compassion, integrity, and innovation.”

“He was like a father,” said Linda Lutgen-Dunckley, a pathology resource technician at RPCI. “Everybody was part of a team, and nobody was less important than he was. He felt everybody played their part on the team.”

Dr Wetzler is survived by his wife, Chana, and their 4 children: Mor, Shira, Adam, and Modi.

The Dr Meir Wetzler Memorial Fund for Leukemia Research has been established to benefit leukemia research. A portion of the donations will be used to plant a tree in his memory in RPCI’s Kaminski Park & Gardens. To donate directly, visit giving.roswellpark.org/wetzler.

To send a personal message to Dr Wetzler’s family, direct it to Jamie Genovese at Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Department of Medicine, Elm and Carlton Streets, Buffalo, NY 14263. Messages can also be dropped off at RPCI’s Leukemia Center. ![]()

Photo courtesy of RPCI

Meir Wetzler, MD, Chief of the Leukemia Section at the Roswell Park Cancer Institute (RPCI) in Buffalo, New York, has died at the age of 60.

Dr Wetzler passed away on February 23, in a Denver, Colorado, hospital a little more than 2 weeks after a skiing accident.

He was nationally prominent in his field and served on the Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia (CML) Treatment Committee of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, helping set the standard of care for CML patients.

Originally from Israel, Dr Wetzler earned his medical degree at Hebrew University’s Hadassah Medical School in Jerusalem and did his residency in internal medicine at Kaplan Hospital in Rehovot before coming to the US.

From 1988 to 1992, he served 2 fellowships—in clinical immunology/biologic therapy and medical oncology—at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas. He joined the Leukemia Division of RPCI in 1994.

Dr Wetzler’s colleagues said he worked tirelessly with cooperative groups and pharmaceutical companies to attract new trials to RPCI for the benefit of his patients.

“He gave a piece of himself in everything he did, from his research to his care for patients to his interactions with his team of colleagues,” said Kara Eaton-Weaver, RPCI’s Executive Director of the Patient and Family Experience. “Meir was a transformational leader who built a culture of empathy, compassion, integrity, and innovation.”

“He was like a father,” said Linda Lutgen-Dunckley, a pathology resource technician at RPCI. “Everybody was part of a team, and nobody was less important than he was. He felt everybody played their part on the team.”

Dr Wetzler is survived by his wife, Chana, and their 4 children: Mor, Shira, Adam, and Modi.

The Dr Meir Wetzler Memorial Fund for Leukemia Research has been established to benefit leukemia research. A portion of the donations will be used to plant a tree in his memory in RPCI’s Kaminski Park & Gardens. To donate directly, visit giving.roswellpark.org/wetzler.

To send a personal message to Dr Wetzler’s family, direct it to Jamie Genovese at Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Department of Medicine, Elm and Carlton Streets, Buffalo, NY 14263. Messages can also be dropped off at RPCI’s Leukemia Center. ![]()

Photo courtesy of RPCI

Meir Wetzler, MD, Chief of the Leukemia Section at the Roswell Park Cancer Institute (RPCI) in Buffalo, New York, has died at the age of 60.

Dr Wetzler passed away on February 23, in a Denver, Colorado, hospital a little more than 2 weeks after a skiing accident.

He was nationally prominent in his field and served on the Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia (CML) Treatment Committee of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, helping set the standard of care for CML patients.

Originally from Israel, Dr Wetzler earned his medical degree at Hebrew University’s Hadassah Medical School in Jerusalem and did his residency in internal medicine at Kaplan Hospital in Rehovot before coming to the US.

From 1988 to 1992, he served 2 fellowships—in clinical immunology/biologic therapy and medical oncology—at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas. He joined the Leukemia Division of RPCI in 1994.

Dr Wetzler’s colleagues said he worked tirelessly with cooperative groups and pharmaceutical companies to attract new trials to RPCI for the benefit of his patients.

“He gave a piece of himself in everything he did, from his research to his care for patients to his interactions with his team of colleagues,” said Kara Eaton-Weaver, RPCI’s Executive Director of the Patient and Family Experience. “Meir was a transformational leader who built a culture of empathy, compassion, integrity, and innovation.”

“He was like a father,” said Linda Lutgen-Dunckley, a pathology resource technician at RPCI. “Everybody was part of a team, and nobody was less important than he was. He felt everybody played their part on the team.”

Dr Wetzler is survived by his wife, Chana, and their 4 children: Mor, Shira, Adam, and Modi.

The Dr Meir Wetzler Memorial Fund for Leukemia Research has been established to benefit leukemia research. A portion of the donations will be used to plant a tree in his memory in RPCI’s Kaminski Park & Gardens. To donate directly, visit giving.roswellpark.org/wetzler.

To send a personal message to Dr Wetzler’s family, direct it to Jamie Genovese at Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Department of Medicine, Elm and Carlton Streets, Buffalo, NY 14263. Messages can also be dropped off at RPCI’s Leukemia Center. ![]()

Evolutionary findings may aid cancer drug development

Photo by Darren Baker

By tracking the evolution of Abl and Src, investigators have made discoveries that may aid the design of highly specific cancer drugs.

Abl and Src are 2 nearly identical protein kinases with a predilection to cause cancer in humans, mainly chronic myeloid leukemia and colon cancer.

The proteins are separated by 146 amino acids and one big difference: Abl is susceptible to treatment with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib (Gleevec), but Src is not.

Dorothee Kern, PhD, of Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts, and her colleagues traced the journey of these 2 proteins over 1 billion years of evolution, pinpointing the exact evolutionary shifts that caused imatinib to bind well with one protein and poorly with the other.

This new approach to researching enzymes and their binding sites may have a major impact on the development of cancer drugs, the investigators said.

They published their findings in Science.

To determine why imatinib binds with Abl but not Src, Dr Kern and her colleagues turned back the evolutionary clock 1 billion years.

This revealed Abl and Src’s common ancestor, a primitive protein in yeast the team dubbed “ANC-AS.” They mapped out the family tree, searching for changes in amino acids and molecular mechanisms.

“Src and Abl differ by 146 amino acids, and we were looking for the handful that dictate Gleevec specificity,” Dr Kern said. “It was like finding a needle in a haystack and could only be done by our evolutionary approach.”

As ANC-AS evolved in more complex organisms, it began to specialize and branch into proteins with different regulation, roles, and catalysis processes—creating Abl and Src.

By following this progression, while testing the proteins’ affinity to imatinib along the way, the investigators were able to whittle down the 146 different amino acids to 15 that are responsible for imatinib specificity.

These 15 amino acids play a role in Abl’s conformational equilibrium—a process in which the protein transitions between 2 structures. The main difference between Abl and Src, when it comes to binding with imatinib, is the relative times the proteins spend in each configuration, resulting in a major difference in their binding energies.

By understanding how and why imatinib works on Abl—and doesn’t work on Src—scientists have a jumping off point to design other drugs with a high affinity and specificity, and a strong binding on cancerous proteins.

“Understanding the molecular basis for Gleevec specificity has opened the door wider to designing good drugs,” Dr Kern said. “Our results pave the way for a different approach to rational drug design.” ![]()

Photo by Darren Baker

By tracking the evolution of Abl and Src, investigators have made discoveries that may aid the design of highly specific cancer drugs.

Abl and Src are 2 nearly identical protein kinases with a predilection to cause cancer in humans, mainly chronic myeloid leukemia and colon cancer.

The proteins are separated by 146 amino acids and one big difference: Abl is susceptible to treatment with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib (Gleevec), but Src is not.

Dorothee Kern, PhD, of Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts, and her colleagues traced the journey of these 2 proteins over 1 billion years of evolution, pinpointing the exact evolutionary shifts that caused imatinib to bind well with one protein and poorly with the other.

This new approach to researching enzymes and their binding sites may have a major impact on the development of cancer drugs, the investigators said.

They published their findings in Science.

To determine why imatinib binds with Abl but not Src, Dr Kern and her colleagues turned back the evolutionary clock 1 billion years.

This revealed Abl and Src’s common ancestor, a primitive protein in yeast the team dubbed “ANC-AS.” They mapped out the family tree, searching for changes in amino acids and molecular mechanisms.

“Src and Abl differ by 146 amino acids, and we were looking for the handful that dictate Gleevec specificity,” Dr Kern said. “It was like finding a needle in a haystack and could only be done by our evolutionary approach.”

As ANC-AS evolved in more complex organisms, it began to specialize and branch into proteins with different regulation, roles, and catalysis processes—creating Abl and Src.

By following this progression, while testing the proteins’ affinity to imatinib along the way, the investigators were able to whittle down the 146 different amino acids to 15 that are responsible for imatinib specificity.

These 15 amino acids play a role in Abl’s conformational equilibrium—a process in which the protein transitions between 2 structures. The main difference between Abl and Src, when it comes to binding with imatinib, is the relative times the proteins spend in each configuration, resulting in a major difference in their binding energies.

By understanding how and why imatinib works on Abl—and doesn’t work on Src—scientists have a jumping off point to design other drugs with a high affinity and specificity, and a strong binding on cancerous proteins.

“Understanding the molecular basis for Gleevec specificity has opened the door wider to designing good drugs,” Dr Kern said. “Our results pave the way for a different approach to rational drug design.” ![]()

Photo by Darren Baker

By tracking the evolution of Abl and Src, investigators have made discoveries that may aid the design of highly specific cancer drugs.

Abl and Src are 2 nearly identical protein kinases with a predilection to cause cancer in humans, mainly chronic myeloid leukemia and colon cancer.

The proteins are separated by 146 amino acids and one big difference: Abl is susceptible to treatment with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib (Gleevec), but Src is not.

Dorothee Kern, PhD, of Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts, and her colleagues traced the journey of these 2 proteins over 1 billion years of evolution, pinpointing the exact evolutionary shifts that caused imatinib to bind well with one protein and poorly with the other.

This new approach to researching enzymes and their binding sites may have a major impact on the development of cancer drugs, the investigators said.

They published their findings in Science.

To determine why imatinib binds with Abl but not Src, Dr Kern and her colleagues turned back the evolutionary clock 1 billion years.

This revealed Abl and Src’s common ancestor, a primitive protein in yeast the team dubbed “ANC-AS.” They mapped out the family tree, searching for changes in amino acids and molecular mechanisms.

“Src and Abl differ by 146 amino acids, and we were looking for the handful that dictate Gleevec specificity,” Dr Kern said. “It was like finding a needle in a haystack and could only be done by our evolutionary approach.”

As ANC-AS evolved in more complex organisms, it began to specialize and branch into proteins with different regulation, roles, and catalysis processes—creating Abl and Src.

By following this progression, while testing the proteins’ affinity to imatinib along the way, the investigators were able to whittle down the 146 different amino acids to 15 that are responsible for imatinib specificity.

These 15 amino acids play a role in Abl’s conformational equilibrium—a process in which the protein transitions between 2 structures. The main difference between Abl and Src, when it comes to binding with imatinib, is the relative times the proteins spend in each configuration, resulting in a major difference in their binding energies.

By understanding how and why imatinib works on Abl—and doesn’t work on Src—scientists have a jumping off point to design other drugs with a high affinity and specificity, and a strong binding on cancerous proteins.

“Understanding the molecular basis for Gleevec specificity has opened the door wider to designing good drugs,” Dr Kern said. “Our results pave the way for a different approach to rational drug design.” ![]()

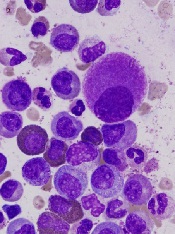

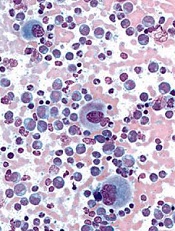

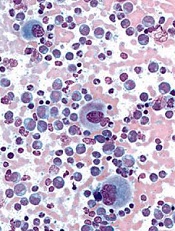

Approved TKI could treat drug-resistant CML, ALL

Photo courtesy of CDC

New research indicates that a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) approved to treat advanced renal cell carcinoma could prove useful in treating patients with drug-resistant chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) or acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

The study showed that the TKI, axitinib, can inhibit BCR-ABL1 (T315I), a mutation known to confer drug resistance in CML and ALL.

“Since axitinib is already used to treat cancer, its safety is known,” said Kimmo Porkka, MD, PhD, of the University of Helsinki in Finland.

“[A] formal exploration of its clinical utility in drug-resistant leukemia can now be done in a fast-track mode. Thus, the normally very long path from lab bench to bedside is now significantly shortened.”

Dr Porkka and his colleagues described the newfound activity of axitinib in Nature.

The researchers used a drug sensitivity and resistance testing method developed at the University of Helsinki’s Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland (FIMM) to examine how patient-derived leukemia cells responded to a large panel of drugs.

In this way, the group identified axitinib as a promising drug candidate for CML and ALL. Axitinib effectively eliminated drug-resistant leukemia cells.

The TKI inhibited BCR-ABL1 (T315I) at biochemical and cellular levels by binding to the active form of ABL1 (T315I) in a mutation-selective binding mode.

The researchers said this suggests the T315I mutation shifts the conformational equilibrium of the kinase in favor of an active (DFG-in) A-loop conformation, which has more optimal binding interactions with axitinib.

“If you think of the targeted protein as a lock into which the cancer drug fits in as a key, the resistant protein changes in such a way that we need a different key,” said study author Brion Murray, PhD, of Pfizer Worldwide Research & Development in San Diego, California.

“In the case of axitinib, it acts as two distinct keys—one for renal cell carcinoma and one for leukemia.”

The researchers also treated a CML patient with axitinib and observed a “rapid reduction” of T315I-positive cells in the patient’s bone marrow.

“Further research will determine whether these findings have the potential to significantly improve the standard of care for this select group of CML patients and patients with other related leukemias,” Dr Murray concluded. ![]()

Photo courtesy of CDC

New research indicates that a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) approved to treat advanced renal cell carcinoma could prove useful in treating patients with drug-resistant chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) or acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

The study showed that the TKI, axitinib, can inhibit BCR-ABL1 (T315I), a mutation known to confer drug resistance in CML and ALL.

“Since axitinib is already used to treat cancer, its safety is known,” said Kimmo Porkka, MD, PhD, of the University of Helsinki in Finland.

“[A] formal exploration of its clinical utility in drug-resistant leukemia can now be done in a fast-track mode. Thus, the normally very long path from lab bench to bedside is now significantly shortened.”

Dr Porkka and his colleagues described the newfound activity of axitinib in Nature.

The researchers used a drug sensitivity and resistance testing method developed at the University of Helsinki’s Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland (FIMM) to examine how patient-derived leukemia cells responded to a large panel of drugs.

In this way, the group identified axitinib as a promising drug candidate for CML and ALL. Axitinib effectively eliminated drug-resistant leukemia cells.

The TKI inhibited BCR-ABL1 (T315I) at biochemical and cellular levels by binding to the active form of ABL1 (T315I) in a mutation-selective binding mode.

The researchers said this suggests the T315I mutation shifts the conformational equilibrium of the kinase in favor of an active (DFG-in) A-loop conformation, which has more optimal binding interactions with axitinib.

“If you think of the targeted protein as a lock into which the cancer drug fits in as a key, the resistant protein changes in such a way that we need a different key,” said study author Brion Murray, PhD, of Pfizer Worldwide Research & Development in San Diego, California.

“In the case of axitinib, it acts as two distinct keys—one for renal cell carcinoma and one for leukemia.”

The researchers also treated a CML patient with axitinib and observed a “rapid reduction” of T315I-positive cells in the patient’s bone marrow.

“Further research will determine whether these findings have the potential to significantly improve the standard of care for this select group of CML patients and patients with other related leukemias,” Dr Murray concluded. ![]()

Photo courtesy of CDC

New research indicates that a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) approved to treat advanced renal cell carcinoma could prove useful in treating patients with drug-resistant chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) or acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

The study showed that the TKI, axitinib, can inhibit BCR-ABL1 (T315I), a mutation known to confer drug resistance in CML and ALL.

“Since axitinib is already used to treat cancer, its safety is known,” said Kimmo Porkka, MD, PhD, of the University of Helsinki in Finland.

“[A] formal exploration of its clinical utility in drug-resistant leukemia can now be done in a fast-track mode. Thus, the normally very long path from lab bench to bedside is now significantly shortened.”

Dr Porkka and his colleagues described the newfound activity of axitinib in Nature.

The researchers used a drug sensitivity and resistance testing method developed at the University of Helsinki’s Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland (FIMM) to examine how patient-derived leukemia cells responded to a large panel of drugs.

In this way, the group identified axitinib as a promising drug candidate for CML and ALL. Axitinib effectively eliminated drug-resistant leukemia cells.

The TKI inhibited BCR-ABL1 (T315I) at biochemical and cellular levels by binding to the active form of ABL1 (T315I) in a mutation-selective binding mode.

The researchers said this suggests the T315I mutation shifts the conformational equilibrium of the kinase in favor of an active (DFG-in) A-loop conformation, which has more optimal binding interactions with axitinib.

“If you think of the targeted protein as a lock into which the cancer drug fits in as a key, the resistant protein changes in such a way that we need a different key,” said study author Brion Murray, PhD, of Pfizer Worldwide Research & Development in San Diego, California.

“In the case of axitinib, it acts as two distinct keys—one for renal cell carcinoma and one for leukemia.”

The researchers also treated a CML patient with axitinib and observed a “rapid reduction” of T315I-positive cells in the patient’s bone marrow.

“Further research will determine whether these findings have the potential to significantly improve the standard of care for this select group of CML patients and patients with other related leukemias,” Dr Murray concluded. ![]()

Though costly, blood cancer drugs appear cost-effective

Photo by Bill Branson

A new analysis indicates that certain high-cost therapies for hematologic malignancies provide reasonable value for money spent.

Most cost-effectiveness ratios were lower than thresholds commonly used to establish cost-effectiveness in the US—$50,000 or $100,000 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained.

The median cost-effectiveness ratio was highest for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), at $55,000/QALY, and lowest for non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), at $21,500/QALY.

Researchers presented these data in Blood.

“Given the increased discussion about the high cost of these treatments, we were somewhat surprised to discover that their cost-effectiveness ratios were lower than expected,” said study author Peter J. Neumann, ScD, of Tufts Medical Center in Boston.

“Our analysis had a small sample size and included both industry- and non-industry-funded studies. In addition, cost-effectiveness ratios may have changed over time as associated costs or benefits have changed. However, the study underscores that debates in healthcare should consider the value of breakthrough drugs and not just costs.”

With that issue in mind, Dr Neumann and his colleagues had conducted a systematic review of studies published between 1996 and 2012 that examined the cost utility of agents for hematologic malignancies. The cost utility of a drug was depicted as a ratio of a drug’s total cost per patient QALY gained.

The researchers identified 29 studies, 22 of which were industry-funded. Nine studies were conducted from a US perspective, 6 from the UK, 3 from Norway, 3 from Sweden, 2 from France, 1 from Canada, 1 from Finland, and 4 from “other” countries.

The team grouped studies according to malignancy—CML, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), NHL, and multiple myeloma (MM)—as well as by treatment—α interferon, alemtuzumab, bendamustine, bortezomib, dasatinib, imatinib, lenalidomide, rituximab alone or in combination, and thalidomide.

The studies reported 44 cost-effectiveness ratios, most concerning interventions for NHL (41%) or CML (30%). Most ratios pertained to rituximab (43%), α interferon (18%), or imatinib (16%), and the most common intervention-disease combination was rituximab (alone or in combination) for NHL (36%).

The median cost-effectiveness ratios fluctuated over time, rising from $35,000/QALY (1996-2002) to $52,000/QALY (2003-2006), then falling to $22,000/QALY (2007-2012).

The median cost-effectiveness ratio reported by industry-funded studies was lower ($26,000/QALY) than for non-industry-funded studies ($33,000/QALY).

Four cost-effectiveness ratios, 1 from an industry-funded study, exceeded $100,000/QALY. This included 2 studies of bortezomib in MM, 1 of α interferon in CML, and 1 of imatinib in CML.

The researchers said these results suggest that many new treatments for hematologic malignancies may confer reasonable value for money spent. The distribution of cost-effectiveness ratios is comparable to those for cancers overall and for other healthcare fields, they said.

This study was funded by internal resources at the Center for the Evaluation of Value and Risk in Health. The center receives funding from federal, private foundation, and pharmaceutical industry sources. ![]()

Photo by Bill Branson

A new analysis indicates that certain high-cost therapies for hematologic malignancies provide reasonable value for money spent.

Most cost-effectiveness ratios were lower than thresholds commonly used to establish cost-effectiveness in the US—$50,000 or $100,000 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained.

The median cost-effectiveness ratio was highest for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), at $55,000/QALY, and lowest for non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), at $21,500/QALY.

Researchers presented these data in Blood.

“Given the increased discussion about the high cost of these treatments, we were somewhat surprised to discover that their cost-effectiveness ratios were lower than expected,” said study author Peter J. Neumann, ScD, of Tufts Medical Center in Boston.

“Our analysis had a small sample size and included both industry- and non-industry-funded studies. In addition, cost-effectiveness ratios may have changed over time as associated costs or benefits have changed. However, the study underscores that debates in healthcare should consider the value of breakthrough drugs and not just costs.”

With that issue in mind, Dr Neumann and his colleagues had conducted a systematic review of studies published between 1996 and 2012 that examined the cost utility of agents for hematologic malignancies. The cost utility of a drug was depicted as a ratio of a drug’s total cost per patient QALY gained.

The researchers identified 29 studies, 22 of which were industry-funded. Nine studies were conducted from a US perspective, 6 from the UK, 3 from Norway, 3 from Sweden, 2 from France, 1 from Canada, 1 from Finland, and 4 from “other” countries.

The team grouped studies according to malignancy—CML, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), NHL, and multiple myeloma (MM)—as well as by treatment—α interferon, alemtuzumab, bendamustine, bortezomib, dasatinib, imatinib, lenalidomide, rituximab alone or in combination, and thalidomide.

The studies reported 44 cost-effectiveness ratios, most concerning interventions for NHL (41%) or CML (30%). Most ratios pertained to rituximab (43%), α interferon (18%), or imatinib (16%), and the most common intervention-disease combination was rituximab (alone or in combination) for NHL (36%).

The median cost-effectiveness ratios fluctuated over time, rising from $35,000/QALY (1996-2002) to $52,000/QALY (2003-2006), then falling to $22,000/QALY (2007-2012).

The median cost-effectiveness ratio reported by industry-funded studies was lower ($26,000/QALY) than for non-industry-funded studies ($33,000/QALY).

Four cost-effectiveness ratios, 1 from an industry-funded study, exceeded $100,000/QALY. This included 2 studies of bortezomib in MM, 1 of α interferon in CML, and 1 of imatinib in CML.

The researchers said these results suggest that many new treatments for hematologic malignancies may confer reasonable value for money spent. The distribution of cost-effectiveness ratios is comparable to those for cancers overall and for other healthcare fields, they said.

This study was funded by internal resources at the Center for the Evaluation of Value and Risk in Health. The center receives funding from federal, private foundation, and pharmaceutical industry sources. ![]()

Photo by Bill Branson

A new analysis indicates that certain high-cost therapies for hematologic malignancies provide reasonable value for money spent.

Most cost-effectiveness ratios were lower than thresholds commonly used to establish cost-effectiveness in the US—$50,000 or $100,000 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained.

The median cost-effectiveness ratio was highest for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), at $55,000/QALY, and lowest for non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), at $21,500/QALY.

Researchers presented these data in Blood.

“Given the increased discussion about the high cost of these treatments, we were somewhat surprised to discover that their cost-effectiveness ratios were lower than expected,” said study author Peter J. Neumann, ScD, of Tufts Medical Center in Boston.

“Our analysis had a small sample size and included both industry- and non-industry-funded studies. In addition, cost-effectiveness ratios may have changed over time as associated costs or benefits have changed. However, the study underscores that debates in healthcare should consider the value of breakthrough drugs and not just costs.”

With that issue in mind, Dr Neumann and his colleagues had conducted a systematic review of studies published between 1996 and 2012 that examined the cost utility of agents for hematologic malignancies. The cost utility of a drug was depicted as a ratio of a drug’s total cost per patient QALY gained.

The researchers identified 29 studies, 22 of which were industry-funded. Nine studies were conducted from a US perspective, 6 from the UK, 3 from Norway, 3 from Sweden, 2 from France, 1 from Canada, 1 from Finland, and 4 from “other” countries.

The team grouped studies according to malignancy—CML, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), NHL, and multiple myeloma (MM)—as well as by treatment—α interferon, alemtuzumab, bendamustine, bortezomib, dasatinib, imatinib, lenalidomide, rituximab alone or in combination, and thalidomide.

The studies reported 44 cost-effectiveness ratios, most concerning interventions for NHL (41%) or CML (30%). Most ratios pertained to rituximab (43%), α interferon (18%), or imatinib (16%), and the most common intervention-disease combination was rituximab (alone or in combination) for NHL (36%).

The median cost-effectiveness ratios fluctuated over time, rising from $35,000/QALY (1996-2002) to $52,000/QALY (2003-2006), then falling to $22,000/QALY (2007-2012).

The median cost-effectiveness ratio reported by industry-funded studies was lower ($26,000/QALY) than for non-industry-funded studies ($33,000/QALY).

Four cost-effectiveness ratios, 1 from an industry-funded study, exceeded $100,000/QALY. This included 2 studies of bortezomib in MM, 1 of α interferon in CML, and 1 of imatinib in CML.

The researchers said these results suggest that many new treatments for hematologic malignancies may confer reasonable value for money spent. The distribution of cost-effectiveness ratios is comparable to those for cancers overall and for other healthcare fields, they said.

This study was funded by internal resources at the Center for the Evaluation of Value and Risk in Health. The center receives funding from federal, private foundation, and pharmaceutical industry sources. ![]()

EC supports continued use of ponatinib

Credit: Rhoda Baer

The European Commission (EC) has concluded that ponatinib (Iclusig) should continue to be prescribed in accordance with its already approved indications.

After trial results suggested the drug poses an increased risk of thrombotic events, the European Medicines Agency’s (EMA) Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) conducted a review of available ponatinib data.

Results of that review suggested the benefits of ponatinib outweigh the risks. So the committee said the drug should be prescribed as indicated.

The EMA’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) recently endorsed this recommendation, and, now, the EC has followed suit. The EC’s decision is legally binding.

Ponatinib is approved in the European Union to treat adults with chronic phase, accelerated phase, or blast phase chronic myeloid leukemia who are resistant to dasatinib or nilotinib, who are intolerant to dasatinib or nilotinib and for whom subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate, or who have the T315I mutation.

The drug is also approved to treat adults with Philadelphia-chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia who are resistant to dasatinib, who cannot tolerate dasatinib and subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate, or who have the T315I mutation.

In October 2013, extended follow-up data from the PACE trial revealed that ponatinib-treated patients had a higher incidence of arterial and venous thrombotic events than was observed when the drug first gained approval. So one ponatinib trial was discontinued, and the rest were placed on partial clinical hold.

Soon after, ponatinib was pulled from the US market. The drug ultimately returned to the marketplace with new recommendations designed to decrease the risk of thrombotic events.

The EMA also revised its recommendations for ponatinib—discouraging use of the drug in certain patients, providing advice for managing comorbidities, and suggesting patient monitoring—but kept the drug on the market.

In October 2014, the PRAC concluded its 11-month review of ponatinib data, confirming that the benefit-risk profile of the drug was favorable in its approved indications and recommending that the indications remain unchanged.

However, the PRAC also said the risk of vascular occlusive events with ponatinib is likely dose-related. So the committee recommended that healthcare professionals monitor ponatinib-treated patients and consider dose reductions or discontinuing the drug in certain patients.

The CHMP endorsed these recommendations, and, now, the EC has as well. This is a legally binding decision for ponatinib to continue to be prescribed in Europe in accordance with its already approved indications.

Ponatinib is being developed by ARIAD Pharmaceuticals, Inc. ![]()

Credit: Rhoda Baer

The European Commission (EC) has concluded that ponatinib (Iclusig) should continue to be prescribed in accordance with its already approved indications.

After trial results suggested the drug poses an increased risk of thrombotic events, the European Medicines Agency’s (EMA) Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) conducted a review of available ponatinib data.

Results of that review suggested the benefits of ponatinib outweigh the risks. So the committee said the drug should be prescribed as indicated.

The EMA’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) recently endorsed this recommendation, and, now, the EC has followed suit. The EC’s decision is legally binding.

Ponatinib is approved in the European Union to treat adults with chronic phase, accelerated phase, or blast phase chronic myeloid leukemia who are resistant to dasatinib or nilotinib, who are intolerant to dasatinib or nilotinib and for whom subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate, or who have the T315I mutation.

The drug is also approved to treat adults with Philadelphia-chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia who are resistant to dasatinib, who cannot tolerate dasatinib and subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate, or who have the T315I mutation.

In October 2013, extended follow-up data from the PACE trial revealed that ponatinib-treated patients had a higher incidence of arterial and venous thrombotic events than was observed when the drug first gained approval. So one ponatinib trial was discontinued, and the rest were placed on partial clinical hold.

Soon after, ponatinib was pulled from the US market. The drug ultimately returned to the marketplace with new recommendations designed to decrease the risk of thrombotic events.

The EMA also revised its recommendations for ponatinib—discouraging use of the drug in certain patients, providing advice for managing comorbidities, and suggesting patient monitoring—but kept the drug on the market.

In October 2014, the PRAC concluded its 11-month review of ponatinib data, confirming that the benefit-risk profile of the drug was favorable in its approved indications and recommending that the indications remain unchanged.

However, the PRAC also said the risk of vascular occlusive events with ponatinib is likely dose-related. So the committee recommended that healthcare professionals monitor ponatinib-treated patients and consider dose reductions or discontinuing the drug in certain patients.

The CHMP endorsed these recommendations, and, now, the EC has as well. This is a legally binding decision for ponatinib to continue to be prescribed in Europe in accordance with its already approved indications.

Ponatinib is being developed by ARIAD Pharmaceuticals, Inc. ![]()

Credit: Rhoda Baer

The European Commission (EC) has concluded that ponatinib (Iclusig) should continue to be prescribed in accordance with its already approved indications.

After trial results suggested the drug poses an increased risk of thrombotic events, the European Medicines Agency’s (EMA) Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) conducted a review of available ponatinib data.

Results of that review suggested the benefits of ponatinib outweigh the risks. So the committee said the drug should be prescribed as indicated.

The EMA’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) recently endorsed this recommendation, and, now, the EC has followed suit. The EC’s decision is legally binding.

Ponatinib is approved in the European Union to treat adults with chronic phase, accelerated phase, or blast phase chronic myeloid leukemia who are resistant to dasatinib or nilotinib, who are intolerant to dasatinib or nilotinib and for whom subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate, or who have the T315I mutation.

The drug is also approved to treat adults with Philadelphia-chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia who are resistant to dasatinib, who cannot tolerate dasatinib and subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate, or who have the T315I mutation.

In October 2013, extended follow-up data from the PACE trial revealed that ponatinib-treated patients had a higher incidence of arterial and venous thrombotic events than was observed when the drug first gained approval. So one ponatinib trial was discontinued, and the rest were placed on partial clinical hold.

Soon after, ponatinib was pulled from the US market. The drug ultimately returned to the marketplace with new recommendations designed to decrease the risk of thrombotic events.

The EMA also revised its recommendations for ponatinib—discouraging use of the drug in certain patients, providing advice for managing comorbidities, and suggesting patient monitoring—but kept the drug on the market.

In October 2014, the PRAC concluded its 11-month review of ponatinib data, confirming that the benefit-risk profile of the drug was favorable in its approved indications and recommending that the indications remain unchanged.

However, the PRAC also said the risk of vascular occlusive events with ponatinib is likely dose-related. So the committee recommended that healthcare professionals monitor ponatinib-treated patients and consider dose reductions or discontinuing the drug in certain patients.

The CHMP endorsed these recommendations, and, now, the EC has as well. This is a legally binding decision for ponatinib to continue to be prescribed in Europe in accordance with its already approved indications.

Ponatinib is being developed by ARIAD Pharmaceuticals, Inc. ![]()

NHS cuts 5 blood cancer drugs from CDF, adds 1

Credit: Steven Harbour

The National Health Service (NHS) has increased the budget for England’s Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF) and added a new drug to treat 2 hematologic malignancies, but 5 other blood cancer drugs will be removed from the fund in March.

The budget for the CDF will grow from £200 million in 2013/14 to £280 million in 2014/15.

However, 16 drugs (for 25 different indications) will no longer be offered through the fund as of March 12, 2015.

Still, the NHS said it has taken steps to ensure patients can receive appropriate treatment.

Review leads to cuts

A national panel of oncologists, pharmacists, and patient representatives independently reviewed the drug indications currently available through the CDF, plus new applications.

They evaluated the clinical benefit, survival, quality of life, toxicity, and safety associated with each treatment, as well as the level of unmet need and the median cost per patient. In cases where the high cost of a drug would lead to its exclusion from CDF, manufacturers were given an opportunity to reduce prices.

The result of the review is that 59 of the 84 most effective currently approved indications of drugs will rollover into the CDF next year, creating room for new drug indications that will be funded for the first time.

These are panitumumab for bowel cancer, ibrutinib for mantle cell lymphoma, and ibrutinib for chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

However, 16 drugs, including 5 blood cancer drugs—bendamustine, bortezomib, bosutinib, dasatinib, and ofatumumab—will no longer be offered through the CDF.

Following these changes, the NHS will put 4 measures in place to ensure patients can receive appropriate treatment. First, any patient currently receiving a drug through the CDF will continue to receive it, regardless of whether it remains in the CDF.

Second, drugs that are the only therapy for the cancer in question will remain available through the CDF. Third, if the CDF panel removes a drug for a particular indication, some patients may instead be able to receive it in another line of therapy or receive an alternative CDF-approved drug.

And finally, clinicians can apply for their patient to receive a drug not available through the CDF on an exceptional basis.

Cuts to blood cancer drugs

The full list of cuts to the CDF is available on the NHS website, but the following list includes all drugs for hematologic malignancies that will no longer be available. These drugs will still be available for other indications, however.

- Bendamustine for the treatment of low-grade lymphoma that is refractory to rituximab alone or in combination.

- Bortezomib for the treatment of:

- relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma after 1 or more prior chemotherapies or stem cell transplant

- relapsed multiple myeloma patients with a previous partial response or complete response of 6 months or more with bortezomib

- relapsed Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia patients who received previous treatment with alkylating agents and purine analogues.

- Bosutinib for the treatment of:

- blast crisis chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) that is refractory to nilotinib or dasatinib if dasatinib was accessed via a clinical trial or via its current approved CDF indication

- blast crisis CML where there is treatment intolerance, specifically, significant intolerance to dasatinib (grade 3 or 4 adverse events) if dasatinib was accessed via its current approved CDF indication.

- Dasatinib for the treatment of lymphoid, blast crisis CML that is refractory to, significantly intolerant of, or resistant to prior therapy including imatinib (grade 3 or 4 adverse events); also when used as the 2nd- or 3rd-line treatment.

- Ofatumumab for the treatment of CML as the 2nd- or 3rd-line indication and if the patient is refractory to treatment with fludarabine in combination and/or alemtuzumab or if treatment with fludarabine in combination and/or alemtuzumab is contraindicated.

More about the CDF and the NHS

The CDF—set up in 2010 and currently due to run until March 2016—is money the government has set aside to pay for cancer drugs that haven’t been approved by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and aren’t available within the NHS in England. Most cancer drugs are routinely funded outside of the CDF.

NHS England said it is working with cancer charities, the pharmaceutical industry, and NICE to create a sustainable model for the commissioning of chemotherapy. The agency has also updated its procedures for evaluating drugs in the CDF, in an effort to ensure sustainability.

In addition, NHS England has set up an appeals process by which pharmaceutical companies can challenge the decision-making process.

And a newly assembled national taskforce, headed by Harpal Kumar, chief executive of Cancer Research UK, is set to produce a refreshed, 5-year cancer plan for the NHS. ![]()

Credit: Steven Harbour

The National Health Service (NHS) has increased the budget for England’s Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF) and added a new drug to treat 2 hematologic malignancies, but 5 other blood cancer drugs will be removed from the fund in March.

The budget for the CDF will grow from £200 million in 2013/14 to £280 million in 2014/15.

However, 16 drugs (for 25 different indications) will no longer be offered through the fund as of March 12, 2015.

Still, the NHS said it has taken steps to ensure patients can receive appropriate treatment.

Review leads to cuts

A national panel of oncologists, pharmacists, and patient representatives independently reviewed the drug indications currently available through the CDF, plus new applications.

They evaluated the clinical benefit, survival, quality of life, toxicity, and safety associated with each treatment, as well as the level of unmet need and the median cost per patient. In cases where the high cost of a drug would lead to its exclusion from CDF, manufacturers were given an opportunity to reduce prices.

The result of the review is that 59 of the 84 most effective currently approved indications of drugs will rollover into the CDF next year, creating room for new drug indications that will be funded for the first time.

These are panitumumab for bowel cancer, ibrutinib for mantle cell lymphoma, and ibrutinib for chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

However, 16 drugs, including 5 blood cancer drugs—bendamustine, bortezomib, bosutinib, dasatinib, and ofatumumab—will no longer be offered through the CDF.

Following these changes, the NHS will put 4 measures in place to ensure patients can receive appropriate treatment. First, any patient currently receiving a drug through the CDF will continue to receive it, regardless of whether it remains in the CDF.

Second, drugs that are the only therapy for the cancer in question will remain available through the CDF. Third, if the CDF panel removes a drug for a particular indication, some patients may instead be able to receive it in another line of therapy or receive an alternative CDF-approved drug.

And finally, clinicians can apply for their patient to receive a drug not available through the CDF on an exceptional basis.

Cuts to blood cancer drugs

The full list of cuts to the CDF is available on the NHS website, but the following list includes all drugs for hematologic malignancies that will no longer be available. These drugs will still be available for other indications, however.

- Bendamustine for the treatment of low-grade lymphoma that is refractory to rituximab alone or in combination.

- Bortezomib for the treatment of:

- relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma after 1 or more prior chemotherapies or stem cell transplant

- relapsed multiple myeloma patients with a previous partial response or complete response of 6 months or more with bortezomib

- relapsed Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia patients who received previous treatment with alkylating agents and purine analogues.

- Bosutinib for the treatment of:

- blast crisis chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) that is refractory to nilotinib or dasatinib if dasatinib was accessed via a clinical trial or via its current approved CDF indication

- blast crisis CML where there is treatment intolerance, specifically, significant intolerance to dasatinib (grade 3 or 4 adverse events) if dasatinib was accessed via its current approved CDF indication.

- Dasatinib for the treatment of lymphoid, blast crisis CML that is refractory to, significantly intolerant of, or resistant to prior therapy including imatinib (grade 3 or 4 adverse events); also when used as the 2nd- or 3rd-line treatment.

- Ofatumumab for the treatment of CML as the 2nd- or 3rd-line indication and if the patient is refractory to treatment with fludarabine in combination and/or alemtuzumab or if treatment with fludarabine in combination and/or alemtuzumab is contraindicated.

More about the CDF and the NHS

The CDF—set up in 2010 and currently due to run until March 2016—is money the government has set aside to pay for cancer drugs that haven’t been approved by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and aren’t available within the NHS in England. Most cancer drugs are routinely funded outside of the CDF.

NHS England said it is working with cancer charities, the pharmaceutical industry, and NICE to create a sustainable model for the commissioning of chemotherapy. The agency has also updated its procedures for evaluating drugs in the CDF, in an effort to ensure sustainability.

In addition, NHS England has set up an appeals process by which pharmaceutical companies can challenge the decision-making process.

And a newly assembled national taskforce, headed by Harpal Kumar, chief executive of Cancer Research UK, is set to produce a refreshed, 5-year cancer plan for the NHS. ![]()

Credit: Steven Harbour

The National Health Service (NHS) has increased the budget for England’s Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF) and added a new drug to treat 2 hematologic malignancies, but 5 other blood cancer drugs will be removed from the fund in March.

The budget for the CDF will grow from £200 million in 2013/14 to £280 million in 2014/15.

However, 16 drugs (for 25 different indications) will no longer be offered through the fund as of March 12, 2015.

Still, the NHS said it has taken steps to ensure patients can receive appropriate treatment.

Review leads to cuts

A national panel of oncologists, pharmacists, and patient representatives independently reviewed the drug indications currently available through the CDF, plus new applications.

They evaluated the clinical benefit, survival, quality of life, toxicity, and safety associated with each treatment, as well as the level of unmet need and the median cost per patient. In cases where the high cost of a drug would lead to its exclusion from CDF, manufacturers were given an opportunity to reduce prices.

The result of the review is that 59 of the 84 most effective currently approved indications of drugs will rollover into the CDF next year, creating room for new drug indications that will be funded for the first time.

These are panitumumab for bowel cancer, ibrutinib for mantle cell lymphoma, and ibrutinib for chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

However, 16 drugs, including 5 blood cancer drugs—bendamustine, bortezomib, bosutinib, dasatinib, and ofatumumab—will no longer be offered through the CDF.

Following these changes, the NHS will put 4 measures in place to ensure patients can receive appropriate treatment. First, any patient currently receiving a drug through the CDF will continue to receive it, regardless of whether it remains in the CDF.

Second, drugs that are the only therapy for the cancer in question will remain available through the CDF. Third, if the CDF panel removes a drug for a particular indication, some patients may instead be able to receive it in another line of therapy or receive an alternative CDF-approved drug.

And finally, clinicians can apply for their patient to receive a drug not available through the CDF on an exceptional basis.

Cuts to blood cancer drugs

The full list of cuts to the CDF is available on the NHS website, but the following list includes all drugs for hematologic malignancies that will no longer be available. These drugs will still be available for other indications, however.

- Bendamustine for the treatment of low-grade lymphoma that is refractory to rituximab alone or in combination.

- Bortezomib for the treatment of:

- relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma after 1 or more prior chemotherapies or stem cell transplant

- relapsed multiple myeloma patients with a previous partial response or complete response of 6 months or more with bortezomib

- relapsed Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia patients who received previous treatment with alkylating agents and purine analogues.

- Bosutinib for the treatment of:

- blast crisis chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) that is refractory to nilotinib or dasatinib if dasatinib was accessed via a clinical trial or via its current approved CDF indication

- blast crisis CML where there is treatment intolerance, specifically, significant intolerance to dasatinib (grade 3 or 4 adverse events) if dasatinib was accessed via its current approved CDF indication.

- Dasatinib for the treatment of lymphoid, blast crisis CML that is refractory to, significantly intolerant of, or resistant to prior therapy including imatinib (grade 3 or 4 adverse events); also when used as the 2nd- or 3rd-line treatment.

- Ofatumumab for the treatment of CML as the 2nd- or 3rd-line indication and if the patient is refractory to treatment with fludarabine in combination and/or alemtuzumab or if treatment with fludarabine in combination and/or alemtuzumab is contraindicated.

More about the CDF and the NHS

The CDF—set up in 2010 and currently due to run until March 2016—is money the government has set aside to pay for cancer drugs that haven’t been approved by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and aren’t available within the NHS in England. Most cancer drugs are routinely funded outside of the CDF.

NHS England said it is working with cancer charities, the pharmaceutical industry, and NICE to create a sustainable model for the commissioning of chemotherapy. The agency has also updated its procedures for evaluating drugs in the CDF, in an effort to ensure sustainability.

In addition, NHS England has set up an appeals process by which pharmaceutical companies can challenge the decision-making process.

And a newly assembled national taskforce, headed by Harpal Kumar, chief executive of Cancer Research UK, is set to produce a refreshed, 5-year cancer plan for the NHS.

Finding could help docs tailor treatment for myeloid leukemias

PHILADELPHIA—New research suggests that stiffness in the extracellular matrix (ECM) can predict how leukemias will respond to therapy.

Using a 3D model, investigators demonstrated that ECM stiffness can affect treatment response in both chronic and acute myeloid leukemia.

The researchers believe that correcting for the matrix effect could give hematologists a new tool for personalizing leukemia treatment.

The team presented this research at the 2014 ASCB/IFCB meeting (poster 429).

Jae-Won Shin, PhD, and David Mooney, PhD, both of Harvard University, knew that myeloid leukemia subtypes are defined by distinct genetic mutations and the activation of known signaling pathways.

But the investigators wanted to see if changes in matrix stiffness played a part in cancer cell proliferation and if myeloid leukemia subtypes could be sorted out by their responses.

The researchers built a 3D hydrogel system with tunable stiffness and attempted to evaluate how relative stiffness of the surrounding ECM affected the resistance of human myeloid leukemias to chemotherapeutic drugs.

They found, for example, that chronic myeloid leukemias (CMLs) grown in their viscous 3D gel system were more resistant to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib than those cultured in a rigid matrix.

Using this and other data from their variable ECM system, the team screened libraries of small-molecule drugs, identifying a subset of drugs they say are more likely to be effective against CML, regardless of the surrounding matrix.

By correcting for the matrix effect, Drs Shin and Mooney believe their novel approach to drug screening could more precisely tailor chemotherapy to a patient’s individual malignancy.

The investigators’ 3D hydrogel system allowed them to vary the stiffness of the matrix and uncover different growth patterns, which they used to profile different leukemia subtypes.

They also looked at a cellular signaling pathway, protein kinase B (AKT), known to be involved in mechanotransduction and therefore sensitive to stiffness in different leukemia subtypes.

They discovered that CML cells in the 3D hydrogel were resistant to an AKT inhibitor, while acute myeloid leukemia cells grown in the same conditions were responsive to the drug, supporting their idea that a tunable matrix system could be a way to sort out leukemia subtypes by drug resistance. ![]()

PHILADELPHIA—New research suggests that stiffness in the extracellular matrix (ECM) can predict how leukemias will respond to therapy.

Using a 3D model, investigators demonstrated that ECM stiffness can affect treatment response in both chronic and acute myeloid leukemia.

The researchers believe that correcting for the matrix effect could give hematologists a new tool for personalizing leukemia treatment.

The team presented this research at the 2014 ASCB/IFCB meeting (poster 429).

Jae-Won Shin, PhD, and David Mooney, PhD, both of Harvard University, knew that myeloid leukemia subtypes are defined by distinct genetic mutations and the activation of known signaling pathways.

But the investigators wanted to see if changes in matrix stiffness played a part in cancer cell proliferation and if myeloid leukemia subtypes could be sorted out by their responses.

The researchers built a 3D hydrogel system with tunable stiffness and attempted to evaluate how relative stiffness of the surrounding ECM affected the resistance of human myeloid leukemias to chemotherapeutic drugs.

They found, for example, that chronic myeloid leukemias (CMLs) grown in their viscous 3D gel system were more resistant to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib than those cultured in a rigid matrix.

Using this and other data from their variable ECM system, the team screened libraries of small-molecule drugs, identifying a subset of drugs they say are more likely to be effective against CML, regardless of the surrounding matrix.

By correcting for the matrix effect, Drs Shin and Mooney believe their novel approach to drug screening could more precisely tailor chemotherapy to a patient’s individual malignancy.

The investigators’ 3D hydrogel system allowed them to vary the stiffness of the matrix and uncover different growth patterns, which they used to profile different leukemia subtypes.

They also looked at a cellular signaling pathway, protein kinase B (AKT), known to be involved in mechanotransduction and therefore sensitive to stiffness in different leukemia subtypes.

They discovered that CML cells in the 3D hydrogel were resistant to an AKT inhibitor, while acute myeloid leukemia cells grown in the same conditions were responsive to the drug, supporting their idea that a tunable matrix system could be a way to sort out leukemia subtypes by drug resistance. ![]()

PHILADELPHIA—New research suggests that stiffness in the extracellular matrix (ECM) can predict how leukemias will respond to therapy.

Using a 3D model, investigators demonstrated that ECM stiffness can affect treatment response in both chronic and acute myeloid leukemia.

The researchers believe that correcting for the matrix effect could give hematologists a new tool for personalizing leukemia treatment.

The team presented this research at the 2014 ASCB/IFCB meeting (poster 429).

Jae-Won Shin, PhD, and David Mooney, PhD, both of Harvard University, knew that myeloid leukemia subtypes are defined by distinct genetic mutations and the activation of known signaling pathways.

But the investigators wanted to see if changes in matrix stiffness played a part in cancer cell proliferation and if myeloid leukemia subtypes could be sorted out by their responses.

The researchers built a 3D hydrogel system with tunable stiffness and attempted to evaluate how relative stiffness of the surrounding ECM affected the resistance of human myeloid leukemias to chemotherapeutic drugs.

They found, for example, that chronic myeloid leukemias (CMLs) grown in their viscous 3D gel system were more resistant to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib than those cultured in a rigid matrix.

Using this and other data from their variable ECM system, the team screened libraries of small-molecule drugs, identifying a subset of drugs they say are more likely to be effective against CML, regardless of the surrounding matrix.

By correcting for the matrix effect, Drs Shin and Mooney believe their novel approach to drug screening could more precisely tailor chemotherapy to a patient’s individual malignancy.

The investigators’ 3D hydrogel system allowed them to vary the stiffness of the matrix and uncover different growth patterns, which they used to profile different leukemia subtypes.

They also looked at a cellular signaling pathway, protein kinase B (AKT), known to be involved in mechanotransduction and therefore sensitive to stiffness in different leukemia subtypes.

They discovered that CML cells in the 3D hydrogel were resistant to an AKT inhibitor, while acute myeloid leukemia cells grown in the same conditions were responsive to the drug, supporting their idea that a tunable matrix system could be a way to sort out leukemia subtypes by drug resistance. ![]()

Discovery reveals potential approach to treat CML

Credit: UCSD School of Medicine

By analyzing structural changes that occur during Abl kinase activation, researchers have gained new insight into this process.

The team discovered a mechanism that links the allosteric regulation of the SH2 domain to two critical phosphorylation events.

As allosteric SH2-kinase domain interactions have proven essential for leukemogenesis caused by Bcr-Abl, the researchers believe this finding has implications for treating chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

Oliver Hantschel, PhD, of the École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) in Lausanne, Switzerland, and his colleagues described this work in Nature Communications.

The team made small, strategic mutations to Abl kinase that caused its 3D structure to change. Then, they tested each mutant version of the enzyme to see if its function would change.

The researchers built on previous studies showing that Abl kinase is indirectly controlled by the SH2 region. Normally, the SH2 region regulates the activation loop by opening and closing it. But under the Philadelphia chromosome translocation, that regulation is lost.

The team discovered that when the Philadelphia mutation takes effect, the SH2 region changes the Abl activation loop to a fully open conformation. This enables the trans-autophosphorylation of the activation loop and requires prior phosphorylation of the SH2-kinase linker.

This discovery provides the first-ever picture of the molecular events surrounding the hyperactivity of Abl kinase, the researchers said.

They also found that by disrupting the SH2-kinase interaction, it’s possible to modulate the activity of Abl kinase, which could potentially stop the growth of leukemia.

Since the SH2 region is common to other kinases, the researchers think it’s likely the effect could extend to malignancies other than CML as well, particularly those characterized by abnormal kinase activity.

Finally, the team expects this approach could overcome the problem of drug resistance in CML, as it might offer an alternative way to inhibit Abl kinase, and mutations of rapidly growing cancer cells may be less likely to occur. ![]()

Credit: UCSD School of Medicine

By analyzing structural changes that occur during Abl kinase activation, researchers have gained new insight into this process.

The team discovered a mechanism that links the allosteric regulation of the SH2 domain to two critical phosphorylation events.

As allosteric SH2-kinase domain interactions have proven essential for leukemogenesis caused by Bcr-Abl, the researchers believe this finding has implications for treating chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

Oliver Hantschel, PhD, of the École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) in Lausanne, Switzerland, and his colleagues described this work in Nature Communications.

The team made small, strategic mutations to Abl kinase that caused its 3D structure to change. Then, they tested each mutant version of the enzyme to see if its function would change.

The researchers built on previous studies showing that Abl kinase is indirectly controlled by the SH2 region. Normally, the SH2 region regulates the activation loop by opening and closing it. But under the Philadelphia chromosome translocation, that regulation is lost.

The team discovered that when the Philadelphia mutation takes effect, the SH2 region changes the Abl activation loop to a fully open conformation. This enables the trans-autophosphorylation of the activation loop and requires prior phosphorylation of the SH2-kinase linker.

This discovery provides the first-ever picture of the molecular events surrounding the hyperactivity of Abl kinase, the researchers said.

They also found that by disrupting the SH2-kinase interaction, it’s possible to modulate the activity of Abl kinase, which could potentially stop the growth of leukemia.

Since the SH2 region is common to other kinases, the researchers think it’s likely the effect could extend to malignancies other than CML as well, particularly those characterized by abnormal kinase activity.

Finally, the team expects this approach could overcome the problem of drug resistance in CML, as it might offer an alternative way to inhibit Abl kinase, and mutations of rapidly growing cancer cells may be less likely to occur. ![]()

Credit: UCSD School of Medicine

By analyzing structural changes that occur during Abl kinase activation, researchers have gained new insight into this process.

The team discovered a mechanism that links the allosteric regulation of the SH2 domain to two critical phosphorylation events.

As allosteric SH2-kinase domain interactions have proven essential for leukemogenesis caused by Bcr-Abl, the researchers believe this finding has implications for treating chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).