User login

Venetoclax produces durable effects in relapsed/refractory CLL

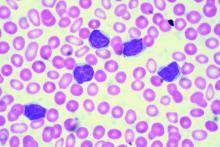

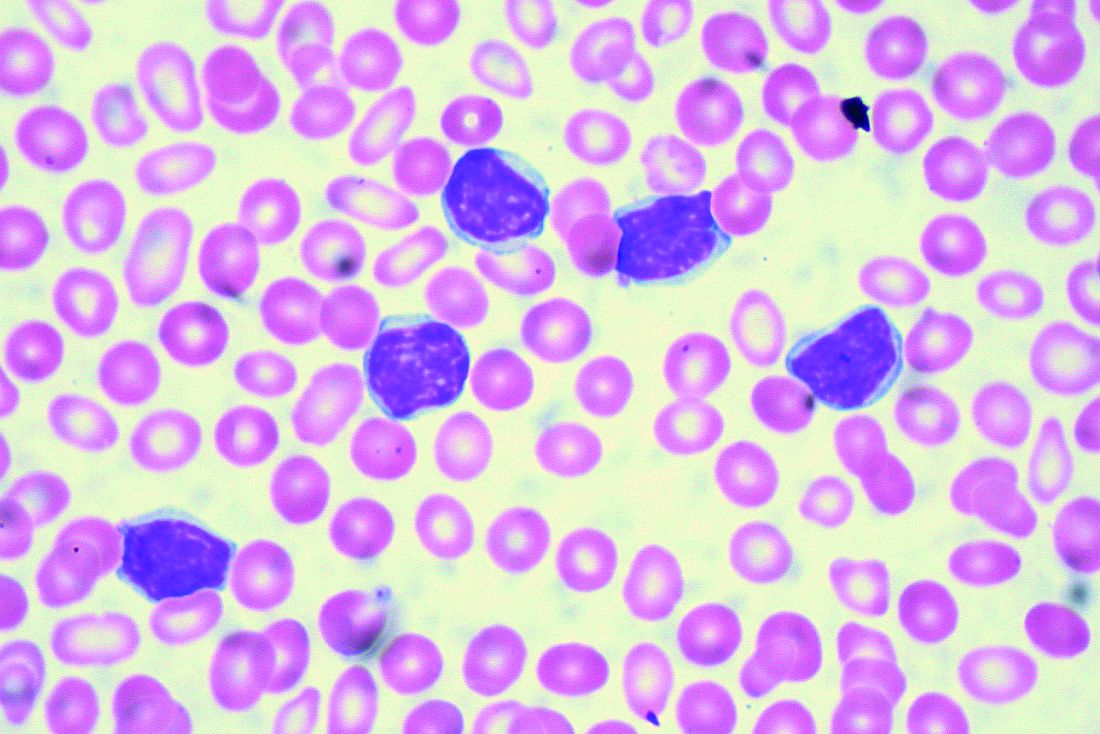

ORLANDO – In patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), the results with venetoclax continue to be encouraging, and recent findings from a multicenter phase Ib study hint that venetoclax may also provide durable responses – even with treatment discontinuation.

Venetoclax is an orally bioavailable selective BCL2 inhibitor that is typically given in an open-ended fashion. Toxicity – including tumor lysis syndrome – is always a concern, however, and the issue of whether open-ended administration is necessary is an important question, Andrew D. Zelenetz, MD, PhD, said at the annual conference of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

In one phase II multicenter study of venetoclax monotherapy in 107 patients with relapsed/refractory CLL with del(17p) at 31 centers in the United States, Canada, and Europe, the overall response rate was 79.4% based on an independent review committee assessment, (Lancet Oncol. 2016[17]:768-78).

Treatment included once-daily venetoclax beginning with a dose of 20 mg that was ramped up to 50, 100, 200, and 400 mg over 4-5 weeks, followed by daily 400 mg continuous dosing until disease progression or discontinuation for another reason.

Notably, 18 of 85 patients from the study who achieved an objective response were minimal residual disease (MRD)–negative in peripheral blood samples – an outcome that has not been seen with tyrosine kinase inhibitors, noted Dr. Zelenetz of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York.

The durability of venetoclax’s activity in the study was 84.7% at 12 months in all responders; 100% in those who achieved complete response, complete response with incomplete recovery of blood counts, or nodular partial remission; and 94.4% in the MRD-negative patients.

The authors concluded that venetoclax monotherapy is active and well tolerated in patients with relapsed or refractory del(17p) chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and that given the distinct mechanism of action of this new therapeutic option for these very poor-prognosis patients, it deserves further investigation as part of a combination or as part of sequential treatment with other novel targeted agents.

The finding that patients on venetoclax can achieve MRD negativity also raised the question of whether treatment can be stopped, Dr. Zelenetz said.

“Because who wants to be on a drug forever? Nobody,” he added.

This question was explored in a study published in February by Seymour et al., which provided early evidence that stopping treatment may indeed be feasible in some patients (Lancet Oncol. 2017;18[2]:230-40).

Venetoclax in this study was given in a dose-escalating fashion to target doses of 200-600 mg daily, in 49 patients with relapsed or refractory “moderately heavily pretreated” CLL. Rituximab was added at a dose of 375 mg/m2 in month 1 and 500 mg/m2 in months 2-6.

Patients had the option of stopping treatment if they achieved a complete response.

The overall response rate was 86%, including a complete response in 51% of patients. Two-year estimates for progression-free survival and ongoing response were 82% and 89% respectively.

MRD negativity was attained in 80% of complete responders and 57% of patients overall. Thirteen responders discontinued all treatment, and at the time of publication, 11 MRD-negative responders who discontinued therapy remained progression free off therapy. Two MRD-positive patients who achieved complete response and discontinued therapy progressed after 2 years, but were able to recapture response once they restarted the drug.

“So it’s really quite interesting. We might have durable responses after discontinuation of this drug in an MRD-negative state,” Dr. Zelenetz said.

Of note, the latest update to the NCCN guidelines for the treatment of CLL/SLL (small lymphocytic lymphoma) included the addition of “+/– rituximab” as part of the “suggested treatment regimen” of venetoclax in the relapsed/refractory disease setting. This recommendation is category 2A, meaning it is based on lower level evidence with uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Venetoclax: adverse events of special interest

In these studies, venetoclax was considered well tolerated, but attention to adverse events and their prevention and management – particularly with respect to tumor lysis syndrome – is essential, Dr. Zelenetz said.

In the phase II study by Stilgenbauer et al., adverse events of special interest included grade 3/4 neutropenia, which occurred in 40% of patients. This was manageable with dose interruptions (five patients) or reductions (four patients), or with granulocyte–colony stimulating factor and antibiotics (six patients, including one who received only antibiotics). None of the patients permanently discontinued treatment.

Infections occurred in 72% of patients, and grade 3 or greater infections occurred in 20% of patients. The most common overall were upper respiratory infections (15%), nasopharyngitis (14%), and urinary tract infections (9%).

Serious infections occurring in two or more patients were pneumonia, lower respiratory tract infection, and upper respiratory tract infection. One patient died from septic shock, 10 had infections leading to venetoclax interruption, and 2 had infections leading to dose reduction.

No mandated infection prophylaxis was used in this study.

Serious adverse events occurred in 59 patients (55%). The most common, occurring in at least 5% of patients, were pyrexia, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, pneumonia, and febrile neutropenia. Thirteen had adverse events leading to dose reductions, most commonly due to neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and febrile neutropenia.

Laboratory-confirmed tumor lysis syndrome was reported in five patients during the ramp-up period, including four who developed the syndrome within the first 2 days of treatment. All cases resolved without clinical sequelae. Treatment was continued without interruption in three patients with tumor lysis syndrome, who received only electrolyte management, and two patients had a 1-day treatment interruption. Both resumed dosing the next day.

In the phase Ib study by Seymour et al., common grade 1-2 toxicities included upper respiratory tract infections, diarrhea, and nausea occurring in 57%, 55%, and 53% of patients, respectively. Grade 3-4 adverse events occurred in 76% of 49 patients, and most often included neutropenia (12% of patients), thrombocytopenia (16%), anemia (14%), febrile neutropenia (12%), and leukopenia (12%). The most common serious adverse events were pyrexia (12%), febrile neutropenia (10%), lower respiratory tract infection (6%), and pneumonia (6%). Clinical tumor lysis syndrome occurred in two patients who initiated venetoclax at 50 mg, one of whom died as a result.

After enhancement of tumor lysis syndrome prophylaxis measures and reduction of the starting dose of venetoclax to 20 mg, no additional cases occurred, the authors reported.

Mitigating tumor lysis syndrome risk

General measures for mitigating the risk of tumor lysis syndrome include identification of patients at increased risk, initiation of prophylaxis with hydration and a uric acid reducing agent, and initiation of venetoclax at a 20 mg dose for 1 week, with gradual step-wise ramp-up over 5 weeks to the target dose, Dr. Zelenetz noted.

As reported by Stilgenbauer, et al., patients with a nodal mass less than 5 cm and absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) of 25,000 or less are considered at low risk for tumor lysis syndrome, those with a nodal mass of 5 cm to less than 10 cm or ALC greater than 25,000 are at medium risk, and those with a nodal mass of 10 cm or greater or nodal mass of 5 cm or greater and ALC of greater than 25,000 are considered to be at high risk.

High-risk patients in the study received inpatient venetoclax dosing and monitoring at 4, 8, 12, and 24 hours with 20 mg and 50 mg dosing, as well as outpatient intravenous hydration at 100 mg if there was no indication to hospitalize, and post-dose 8-24 hour laboratory monitoring at 100 mg and above.

Medium-risk patients received IV hydration at 20 and 50 mg dosing, inpatient care if creatinine clearance was less than 80 mL/min or if there was a high tumor burden, and postdose 8- and 24-hour laboratory monitoring after the initial dose and at dose escalations. Low-risk patients received outpatient dosing at all dose levels in the absence of an indication to hospitalize, and postdose 8- and 24-hour laboratory monitoring after the initial dose and at dose increases.

“Unfortunately, the dose-limiting toxicity of venetoclax is fatal tumor lysis,” Dr. Zelenetz said, adding that by increasing the dose slowly over time according to current treatment recommendations – from 20 mg, to 50, 100, 200, and 400 mg at weekly intervals, this complication can be avoided.

Dr. Zelenetz reported receiving consulting fees, honoraria, and/or grant/research support from Genentech, the maker of venetoclax (Venclexta), and a wide variety of other drug companies.

ORLANDO – In patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), the results with venetoclax continue to be encouraging, and recent findings from a multicenter phase Ib study hint that venetoclax may also provide durable responses – even with treatment discontinuation.

Venetoclax is an orally bioavailable selective BCL2 inhibitor that is typically given in an open-ended fashion. Toxicity – including tumor lysis syndrome – is always a concern, however, and the issue of whether open-ended administration is necessary is an important question, Andrew D. Zelenetz, MD, PhD, said at the annual conference of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

In one phase II multicenter study of venetoclax monotherapy in 107 patients with relapsed/refractory CLL with del(17p) at 31 centers in the United States, Canada, and Europe, the overall response rate was 79.4% based on an independent review committee assessment, (Lancet Oncol. 2016[17]:768-78).

Treatment included once-daily venetoclax beginning with a dose of 20 mg that was ramped up to 50, 100, 200, and 400 mg over 4-5 weeks, followed by daily 400 mg continuous dosing until disease progression or discontinuation for another reason.

Notably, 18 of 85 patients from the study who achieved an objective response were minimal residual disease (MRD)–negative in peripheral blood samples – an outcome that has not been seen with tyrosine kinase inhibitors, noted Dr. Zelenetz of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York.

The durability of venetoclax’s activity in the study was 84.7% at 12 months in all responders; 100% in those who achieved complete response, complete response with incomplete recovery of blood counts, or nodular partial remission; and 94.4% in the MRD-negative patients.

The authors concluded that venetoclax monotherapy is active and well tolerated in patients with relapsed or refractory del(17p) chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and that given the distinct mechanism of action of this new therapeutic option for these very poor-prognosis patients, it deserves further investigation as part of a combination or as part of sequential treatment with other novel targeted agents.

The finding that patients on venetoclax can achieve MRD negativity also raised the question of whether treatment can be stopped, Dr. Zelenetz said.

“Because who wants to be on a drug forever? Nobody,” he added.

This question was explored in a study published in February by Seymour et al., which provided early evidence that stopping treatment may indeed be feasible in some patients (Lancet Oncol. 2017;18[2]:230-40).

Venetoclax in this study was given in a dose-escalating fashion to target doses of 200-600 mg daily, in 49 patients with relapsed or refractory “moderately heavily pretreated” CLL. Rituximab was added at a dose of 375 mg/m2 in month 1 and 500 mg/m2 in months 2-6.

Patients had the option of stopping treatment if they achieved a complete response.

The overall response rate was 86%, including a complete response in 51% of patients. Two-year estimates for progression-free survival and ongoing response were 82% and 89% respectively.

MRD negativity was attained in 80% of complete responders and 57% of patients overall. Thirteen responders discontinued all treatment, and at the time of publication, 11 MRD-negative responders who discontinued therapy remained progression free off therapy. Two MRD-positive patients who achieved complete response and discontinued therapy progressed after 2 years, but were able to recapture response once they restarted the drug.

“So it’s really quite interesting. We might have durable responses after discontinuation of this drug in an MRD-negative state,” Dr. Zelenetz said.

Of note, the latest update to the NCCN guidelines for the treatment of CLL/SLL (small lymphocytic lymphoma) included the addition of “+/– rituximab” as part of the “suggested treatment regimen” of venetoclax in the relapsed/refractory disease setting. This recommendation is category 2A, meaning it is based on lower level evidence with uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Venetoclax: adverse events of special interest

In these studies, venetoclax was considered well tolerated, but attention to adverse events and their prevention and management – particularly with respect to tumor lysis syndrome – is essential, Dr. Zelenetz said.

In the phase II study by Stilgenbauer et al., adverse events of special interest included grade 3/4 neutropenia, which occurred in 40% of patients. This was manageable with dose interruptions (five patients) or reductions (four patients), or with granulocyte–colony stimulating factor and antibiotics (six patients, including one who received only antibiotics). None of the patients permanently discontinued treatment.

Infections occurred in 72% of patients, and grade 3 or greater infections occurred in 20% of patients. The most common overall were upper respiratory infections (15%), nasopharyngitis (14%), and urinary tract infections (9%).

Serious infections occurring in two or more patients were pneumonia, lower respiratory tract infection, and upper respiratory tract infection. One patient died from septic shock, 10 had infections leading to venetoclax interruption, and 2 had infections leading to dose reduction.

No mandated infection prophylaxis was used in this study.

Serious adverse events occurred in 59 patients (55%). The most common, occurring in at least 5% of patients, were pyrexia, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, pneumonia, and febrile neutropenia. Thirteen had adverse events leading to dose reductions, most commonly due to neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and febrile neutropenia.

Laboratory-confirmed tumor lysis syndrome was reported in five patients during the ramp-up period, including four who developed the syndrome within the first 2 days of treatment. All cases resolved without clinical sequelae. Treatment was continued without interruption in three patients with tumor lysis syndrome, who received only electrolyte management, and two patients had a 1-day treatment interruption. Both resumed dosing the next day.

In the phase Ib study by Seymour et al., common grade 1-2 toxicities included upper respiratory tract infections, diarrhea, and nausea occurring in 57%, 55%, and 53% of patients, respectively. Grade 3-4 adverse events occurred in 76% of 49 patients, and most often included neutropenia (12% of patients), thrombocytopenia (16%), anemia (14%), febrile neutropenia (12%), and leukopenia (12%). The most common serious adverse events were pyrexia (12%), febrile neutropenia (10%), lower respiratory tract infection (6%), and pneumonia (6%). Clinical tumor lysis syndrome occurred in two patients who initiated venetoclax at 50 mg, one of whom died as a result.

After enhancement of tumor lysis syndrome prophylaxis measures and reduction of the starting dose of venetoclax to 20 mg, no additional cases occurred, the authors reported.

Mitigating tumor lysis syndrome risk

General measures for mitigating the risk of tumor lysis syndrome include identification of patients at increased risk, initiation of prophylaxis with hydration and a uric acid reducing agent, and initiation of venetoclax at a 20 mg dose for 1 week, with gradual step-wise ramp-up over 5 weeks to the target dose, Dr. Zelenetz noted.

As reported by Stilgenbauer, et al., patients with a nodal mass less than 5 cm and absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) of 25,000 or less are considered at low risk for tumor lysis syndrome, those with a nodal mass of 5 cm to less than 10 cm or ALC greater than 25,000 are at medium risk, and those with a nodal mass of 10 cm or greater or nodal mass of 5 cm or greater and ALC of greater than 25,000 are considered to be at high risk.

High-risk patients in the study received inpatient venetoclax dosing and monitoring at 4, 8, 12, and 24 hours with 20 mg and 50 mg dosing, as well as outpatient intravenous hydration at 100 mg if there was no indication to hospitalize, and post-dose 8-24 hour laboratory monitoring at 100 mg and above.

Medium-risk patients received IV hydration at 20 and 50 mg dosing, inpatient care if creatinine clearance was less than 80 mL/min or if there was a high tumor burden, and postdose 8- and 24-hour laboratory monitoring after the initial dose and at dose escalations. Low-risk patients received outpatient dosing at all dose levels in the absence of an indication to hospitalize, and postdose 8- and 24-hour laboratory monitoring after the initial dose and at dose increases.

“Unfortunately, the dose-limiting toxicity of venetoclax is fatal tumor lysis,” Dr. Zelenetz said, adding that by increasing the dose slowly over time according to current treatment recommendations – from 20 mg, to 50, 100, 200, and 400 mg at weekly intervals, this complication can be avoided.

Dr. Zelenetz reported receiving consulting fees, honoraria, and/or grant/research support from Genentech, the maker of venetoclax (Venclexta), and a wide variety of other drug companies.

ORLANDO – In patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), the results with venetoclax continue to be encouraging, and recent findings from a multicenter phase Ib study hint that venetoclax may also provide durable responses – even with treatment discontinuation.

Venetoclax is an orally bioavailable selective BCL2 inhibitor that is typically given in an open-ended fashion. Toxicity – including tumor lysis syndrome – is always a concern, however, and the issue of whether open-ended administration is necessary is an important question, Andrew D. Zelenetz, MD, PhD, said at the annual conference of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

In one phase II multicenter study of venetoclax monotherapy in 107 patients with relapsed/refractory CLL with del(17p) at 31 centers in the United States, Canada, and Europe, the overall response rate was 79.4% based on an independent review committee assessment, (Lancet Oncol. 2016[17]:768-78).

Treatment included once-daily venetoclax beginning with a dose of 20 mg that was ramped up to 50, 100, 200, and 400 mg over 4-5 weeks, followed by daily 400 mg continuous dosing until disease progression or discontinuation for another reason.

Notably, 18 of 85 patients from the study who achieved an objective response were minimal residual disease (MRD)–negative in peripheral blood samples – an outcome that has not been seen with tyrosine kinase inhibitors, noted Dr. Zelenetz of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York.

The durability of venetoclax’s activity in the study was 84.7% at 12 months in all responders; 100% in those who achieved complete response, complete response with incomplete recovery of blood counts, or nodular partial remission; and 94.4% in the MRD-negative patients.

The authors concluded that venetoclax monotherapy is active and well tolerated in patients with relapsed or refractory del(17p) chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and that given the distinct mechanism of action of this new therapeutic option for these very poor-prognosis patients, it deserves further investigation as part of a combination or as part of sequential treatment with other novel targeted agents.

The finding that patients on venetoclax can achieve MRD negativity also raised the question of whether treatment can be stopped, Dr. Zelenetz said.

“Because who wants to be on a drug forever? Nobody,” he added.

This question was explored in a study published in February by Seymour et al., which provided early evidence that stopping treatment may indeed be feasible in some patients (Lancet Oncol. 2017;18[2]:230-40).

Venetoclax in this study was given in a dose-escalating fashion to target doses of 200-600 mg daily, in 49 patients with relapsed or refractory “moderately heavily pretreated” CLL. Rituximab was added at a dose of 375 mg/m2 in month 1 and 500 mg/m2 in months 2-6.

Patients had the option of stopping treatment if they achieved a complete response.

The overall response rate was 86%, including a complete response in 51% of patients. Two-year estimates for progression-free survival and ongoing response were 82% and 89% respectively.

MRD negativity was attained in 80% of complete responders and 57% of patients overall. Thirteen responders discontinued all treatment, and at the time of publication, 11 MRD-negative responders who discontinued therapy remained progression free off therapy. Two MRD-positive patients who achieved complete response and discontinued therapy progressed after 2 years, but were able to recapture response once they restarted the drug.

“So it’s really quite interesting. We might have durable responses after discontinuation of this drug in an MRD-negative state,” Dr. Zelenetz said.

Of note, the latest update to the NCCN guidelines for the treatment of CLL/SLL (small lymphocytic lymphoma) included the addition of “+/– rituximab” as part of the “suggested treatment regimen” of venetoclax in the relapsed/refractory disease setting. This recommendation is category 2A, meaning it is based on lower level evidence with uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Venetoclax: adverse events of special interest

In these studies, venetoclax was considered well tolerated, but attention to adverse events and their prevention and management – particularly with respect to tumor lysis syndrome – is essential, Dr. Zelenetz said.

In the phase II study by Stilgenbauer et al., adverse events of special interest included grade 3/4 neutropenia, which occurred in 40% of patients. This was manageable with dose interruptions (five patients) or reductions (four patients), or with granulocyte–colony stimulating factor and antibiotics (six patients, including one who received only antibiotics). None of the patients permanently discontinued treatment.

Infections occurred in 72% of patients, and grade 3 or greater infections occurred in 20% of patients. The most common overall were upper respiratory infections (15%), nasopharyngitis (14%), and urinary tract infections (9%).

Serious infections occurring in two or more patients were pneumonia, lower respiratory tract infection, and upper respiratory tract infection. One patient died from septic shock, 10 had infections leading to venetoclax interruption, and 2 had infections leading to dose reduction.

No mandated infection prophylaxis was used in this study.

Serious adverse events occurred in 59 patients (55%). The most common, occurring in at least 5% of patients, were pyrexia, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, pneumonia, and febrile neutropenia. Thirteen had adverse events leading to dose reductions, most commonly due to neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and febrile neutropenia.

Laboratory-confirmed tumor lysis syndrome was reported in five patients during the ramp-up period, including four who developed the syndrome within the first 2 days of treatment. All cases resolved without clinical sequelae. Treatment was continued without interruption in three patients with tumor lysis syndrome, who received only electrolyte management, and two patients had a 1-day treatment interruption. Both resumed dosing the next day.

In the phase Ib study by Seymour et al., common grade 1-2 toxicities included upper respiratory tract infections, diarrhea, and nausea occurring in 57%, 55%, and 53% of patients, respectively. Grade 3-4 adverse events occurred in 76% of 49 patients, and most often included neutropenia (12% of patients), thrombocytopenia (16%), anemia (14%), febrile neutropenia (12%), and leukopenia (12%). The most common serious adverse events were pyrexia (12%), febrile neutropenia (10%), lower respiratory tract infection (6%), and pneumonia (6%). Clinical tumor lysis syndrome occurred in two patients who initiated venetoclax at 50 mg, one of whom died as a result.

After enhancement of tumor lysis syndrome prophylaxis measures and reduction of the starting dose of venetoclax to 20 mg, no additional cases occurred, the authors reported.

Mitigating tumor lysis syndrome risk

General measures for mitigating the risk of tumor lysis syndrome include identification of patients at increased risk, initiation of prophylaxis with hydration and a uric acid reducing agent, and initiation of venetoclax at a 20 mg dose for 1 week, with gradual step-wise ramp-up over 5 weeks to the target dose, Dr. Zelenetz noted.

As reported by Stilgenbauer, et al., patients with a nodal mass less than 5 cm and absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) of 25,000 or less are considered at low risk for tumor lysis syndrome, those with a nodal mass of 5 cm to less than 10 cm or ALC greater than 25,000 are at medium risk, and those with a nodal mass of 10 cm or greater or nodal mass of 5 cm or greater and ALC of greater than 25,000 are considered to be at high risk.

High-risk patients in the study received inpatient venetoclax dosing and monitoring at 4, 8, 12, and 24 hours with 20 mg and 50 mg dosing, as well as outpatient intravenous hydration at 100 mg if there was no indication to hospitalize, and post-dose 8-24 hour laboratory monitoring at 100 mg and above.

Medium-risk patients received IV hydration at 20 and 50 mg dosing, inpatient care if creatinine clearance was less than 80 mL/min or if there was a high tumor burden, and postdose 8- and 24-hour laboratory monitoring after the initial dose and at dose escalations. Low-risk patients received outpatient dosing at all dose levels in the absence of an indication to hospitalize, and postdose 8- and 24-hour laboratory monitoring after the initial dose and at dose increases.

“Unfortunately, the dose-limiting toxicity of venetoclax is fatal tumor lysis,” Dr. Zelenetz said, adding that by increasing the dose slowly over time according to current treatment recommendations – from 20 mg, to 50, 100, 200, and 400 mg at weekly intervals, this complication can be avoided.

Dr. Zelenetz reported receiving consulting fees, honoraria, and/or grant/research support from Genentech, the maker of venetoclax (Venclexta), and a wide variety of other drug companies.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT THE NCCN ANNUAL CONFERENCE

Advanced CLL treatment approach depends on comorbidity burden

ORLANDO – The choice of first-line therapy in symptomatic chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients depends largely on comorbidity burden, Andrew D. Zelenetz, MD, PhD, said at the annual conference of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

“This is a disease of elderly patients. Frequently they have comorbidities,” he said. Categorizing these patients as having a low or high comorbidity burden can be done with the Cumulative Index Rating Scale score, which involves scoring of all organ systems on a 0-5 scale representing “not affected” to “extremely disabled.”

“We use this to determine first-line therapy,” said Dr. Zelenetz of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York. Dr. Zelenetz is chair of the NCCN Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Guidelines panel.

Patients with a score of greater than 12 on the 0- to 56-point scale, are “no-go” patients with respect to therapy, and are typically treated only with palliative approaches. Those with a score of 7-12 (“slow-go” patients) have a significant comorbidity burden, but can undergo treatment, thought typically to be at reduced intensity. Those with a score of 0-6 are “go-go” patients with respect to treatment, as they are physically fit, have excellent renal function, and have no significant comorbidities, he said.

Treatment options for ‘go-go’ CLL patients

Among the treatment options for the latter is FCR–the combination of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab, which was shown in the phase III CLL10 trial of patients with advanced CLL to be associated with improved complete response rates compared with the popular regimen of bendamustine and rituximab (BR), both overall and in patients under age 65. In older patients, the advantage disappeared, Dr. Zelenetz said.

FCR was also associated with improved outcomes vs. BR in patients with del(11q).

The primary endpoint of the study was progression-free survival, which favored FCR (median of 55.2 vs. 41.7 months; hazard ratio, 1.643), he said, noting that no difference was seen between the two regimens in terms of overall survival.

In a recent publication, MD Anderson Cancer Center reported its experience with its first 300 CLL patients treated with FCR. With long-term follow-up of at least 9-10 years (median of 12.8 years), patients in this trial have done extremely well.

“But interestingly, when you stratify these patients by whether they have IGHV [immunoglobulin heavy chain variable] mutated or unmutated [disease], the IGHV mutated patients have something that looks a whole lot like a survival plateau, and that survival plateau is not trivial – it’s about 60%,” he said. “So there is a group of patients with CLL who are, in fact, curable with conventional chemoimmunotherapy.

“This is an appropriate treatment for a young, fit, ‘go-go’ patient, and it has a big implication,” he said. That is, patients who are young and fit require IGHV mutation testing, as “you will absolutely choose FCR chemotherapy for the fit, young patients who has IGHV mutated disease.

“In that setting IGHV testing is now mandatory,” he stressed, noting that the benefits in this population extend to overall survival as well as progression-free survival.

Dr. Zelenetz also emphasized the need for increasing the single dose of rituximab from 375 mg/m2 during cycle 1 to 500 mg/m2 during cycles 2-6 in those receiving FCR, as this is often forgotten.

The data demonstrating the efficacy of FCR were based on this approach, he said.

Fludarabine is to be given at a dose of 25 mg/m2, and cyclophosphamide at a dose of 250 mg/m2 – both for 2-4 days during cycle 1 and for 1-3 days during cycles 2-6.

Treatment options for ‘slow-go’ CLL patients

In “slow-go” patients, an interesting approach is to use new anti-CD20 antibodies such as ofatumumab and obinutuzumab, which have features that are distinct from rituximab.

Both have been studied in CLL. The CLL11 trial compared chlorambucil, rituximab+chlorambucil, and obinutuzumab+chlorambucil, and the latest analysis showed substantial improvement in progression-free survival with obinutuzumab+chlorambucil vs. the other two regimens (26.7 months vs. 11.1 and 16.3 months, respectively), Dr. Zelenetz said, noting that rituximab+chlorambucil was also superior to chlorambucil alone, but that only the obinutuzumab regimen had an overall survival advantage vs. chlorambucil alone.

An updated analysis to be reported soon will show emerging evidence of a survival advantage of obinutuzumab+chlorambucil vs. rituximab+chlorambucil, he said.

“This suggests that obinutuzumab is a far better antibody,” he added, noting that the reasons for that are under debate, “but the way it’s given, it works better in CLL, and that, I think is unequivocal.”

A similar study looking at chlorambucil with and without ofatumumab in “slow-go” patients also demonstrated an improvement in PFS with ofatumumab, but showed “no difference whatsoever in overall survival.”

“This is actually very similar to the rituximab result, and I actually call this the ‘death of ofatumumab’ study, because clearly obinutuzumab in CLL is, I think, a superior anti-CD20 antibody,” Dr. Zelenetz said.

Studies in which obinutuzumab is substituted for rituximab in the FCR combination are currently underway as are a number of other studies of obinutuzumab, he noted.

Another treatment option in the up-front setting is ibrutinib, which was shown to be effective in the RESONATE 2 trial .

“But notice, a very, very small [complete response rate]. CRs are very difficult to achieve with ibrutinib alone, so this drug is given continuously, lifelong,” Dr. Zelenetz said, noting that it was, however, associated with an overall survival advantage vs. chlorambucil.

“Should this be the standard of care? I think it is in patients who have del(17p) or mutation of TP53. Outside of that setting, I’m still concerned about the cost of long-term tolerability of the agent,” he said.

Future of first-line CLL treatment

Avoidance of long-term therapy and conventional chemotherapy in patients with CLL is a goal, he added, noting that new understanding from studies in patients in the relapsed/refractory CLL setting – such as recent findings from a phase Ib study of venetoclax plus rituximab, which demonstrated potentially durable responses after treatment discontinuation in minimal residual disease (MRD)–negative patients – are providing insights into achieving MRD negativity that could be applied in the front line treatment setting.

“We’re still trying to figure out how to best use this. We want to try to use some of this knowledge about achievement of MRD negativity in the up-front setting so we don’t have to give patients long-term therapy, and we would like to avoid conventional chemotherapy,” he said. “So I’m hoping we’re going to be able to replace chronic long-term therapy of CLL with a defined course of treatment with high levels of MRD negativity.”

Dr. Zelenetz reported receiving consulting fees, honoraria, and/or grant/research support from Acerta Pharma, Amgen Inc., BeiGene, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene Corporation, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Janssen Pharmaceutica Products, MEI Pharma, NanoString Technologies, Pharmacyclics, Portola Pharmaceuticals, Roche Laboratories, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America.

ORLANDO – The choice of first-line therapy in symptomatic chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients depends largely on comorbidity burden, Andrew D. Zelenetz, MD, PhD, said at the annual conference of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

“This is a disease of elderly patients. Frequently they have comorbidities,” he said. Categorizing these patients as having a low or high comorbidity burden can be done with the Cumulative Index Rating Scale score, which involves scoring of all organ systems on a 0-5 scale representing “not affected” to “extremely disabled.”

“We use this to determine first-line therapy,” said Dr. Zelenetz of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York. Dr. Zelenetz is chair of the NCCN Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Guidelines panel.

Patients with a score of greater than 12 on the 0- to 56-point scale, are “no-go” patients with respect to therapy, and are typically treated only with palliative approaches. Those with a score of 7-12 (“slow-go” patients) have a significant comorbidity burden, but can undergo treatment, thought typically to be at reduced intensity. Those with a score of 0-6 are “go-go” patients with respect to treatment, as they are physically fit, have excellent renal function, and have no significant comorbidities, he said.

Treatment options for ‘go-go’ CLL patients

Among the treatment options for the latter is FCR–the combination of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab, which was shown in the phase III CLL10 trial of patients with advanced CLL to be associated with improved complete response rates compared with the popular regimen of bendamustine and rituximab (BR), both overall and in patients under age 65. In older patients, the advantage disappeared, Dr. Zelenetz said.

FCR was also associated with improved outcomes vs. BR in patients with del(11q).

The primary endpoint of the study was progression-free survival, which favored FCR (median of 55.2 vs. 41.7 months; hazard ratio, 1.643), he said, noting that no difference was seen between the two regimens in terms of overall survival.

In a recent publication, MD Anderson Cancer Center reported its experience with its first 300 CLL patients treated with FCR. With long-term follow-up of at least 9-10 years (median of 12.8 years), patients in this trial have done extremely well.

“But interestingly, when you stratify these patients by whether they have IGHV [immunoglobulin heavy chain variable] mutated or unmutated [disease], the IGHV mutated patients have something that looks a whole lot like a survival plateau, and that survival plateau is not trivial – it’s about 60%,” he said. “So there is a group of patients with CLL who are, in fact, curable with conventional chemoimmunotherapy.

“This is an appropriate treatment for a young, fit, ‘go-go’ patient, and it has a big implication,” he said. That is, patients who are young and fit require IGHV mutation testing, as “you will absolutely choose FCR chemotherapy for the fit, young patients who has IGHV mutated disease.

“In that setting IGHV testing is now mandatory,” he stressed, noting that the benefits in this population extend to overall survival as well as progression-free survival.

Dr. Zelenetz also emphasized the need for increasing the single dose of rituximab from 375 mg/m2 during cycle 1 to 500 mg/m2 during cycles 2-6 in those receiving FCR, as this is often forgotten.

The data demonstrating the efficacy of FCR were based on this approach, he said.

Fludarabine is to be given at a dose of 25 mg/m2, and cyclophosphamide at a dose of 250 mg/m2 – both for 2-4 days during cycle 1 and for 1-3 days during cycles 2-6.

Treatment options for ‘slow-go’ CLL patients

In “slow-go” patients, an interesting approach is to use new anti-CD20 antibodies such as ofatumumab and obinutuzumab, which have features that are distinct from rituximab.

Both have been studied in CLL. The CLL11 trial compared chlorambucil, rituximab+chlorambucil, and obinutuzumab+chlorambucil, and the latest analysis showed substantial improvement in progression-free survival with obinutuzumab+chlorambucil vs. the other two regimens (26.7 months vs. 11.1 and 16.3 months, respectively), Dr. Zelenetz said, noting that rituximab+chlorambucil was also superior to chlorambucil alone, but that only the obinutuzumab regimen had an overall survival advantage vs. chlorambucil alone.

An updated analysis to be reported soon will show emerging evidence of a survival advantage of obinutuzumab+chlorambucil vs. rituximab+chlorambucil, he said.

“This suggests that obinutuzumab is a far better antibody,” he added, noting that the reasons for that are under debate, “but the way it’s given, it works better in CLL, and that, I think is unequivocal.”

A similar study looking at chlorambucil with and without ofatumumab in “slow-go” patients also demonstrated an improvement in PFS with ofatumumab, but showed “no difference whatsoever in overall survival.”

“This is actually very similar to the rituximab result, and I actually call this the ‘death of ofatumumab’ study, because clearly obinutuzumab in CLL is, I think, a superior anti-CD20 antibody,” Dr. Zelenetz said.

Studies in which obinutuzumab is substituted for rituximab in the FCR combination are currently underway as are a number of other studies of obinutuzumab, he noted.

Another treatment option in the up-front setting is ibrutinib, which was shown to be effective in the RESONATE 2 trial .

“But notice, a very, very small [complete response rate]. CRs are very difficult to achieve with ibrutinib alone, so this drug is given continuously, lifelong,” Dr. Zelenetz said, noting that it was, however, associated with an overall survival advantage vs. chlorambucil.

“Should this be the standard of care? I think it is in patients who have del(17p) or mutation of TP53. Outside of that setting, I’m still concerned about the cost of long-term tolerability of the agent,” he said.

Future of first-line CLL treatment

Avoidance of long-term therapy and conventional chemotherapy in patients with CLL is a goal, he added, noting that new understanding from studies in patients in the relapsed/refractory CLL setting – such as recent findings from a phase Ib study of venetoclax plus rituximab, which demonstrated potentially durable responses after treatment discontinuation in minimal residual disease (MRD)–negative patients – are providing insights into achieving MRD negativity that could be applied in the front line treatment setting.

“We’re still trying to figure out how to best use this. We want to try to use some of this knowledge about achievement of MRD negativity in the up-front setting so we don’t have to give patients long-term therapy, and we would like to avoid conventional chemotherapy,” he said. “So I’m hoping we’re going to be able to replace chronic long-term therapy of CLL with a defined course of treatment with high levels of MRD negativity.”

Dr. Zelenetz reported receiving consulting fees, honoraria, and/or grant/research support from Acerta Pharma, Amgen Inc., BeiGene, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene Corporation, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Janssen Pharmaceutica Products, MEI Pharma, NanoString Technologies, Pharmacyclics, Portola Pharmaceuticals, Roche Laboratories, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America.

ORLANDO – The choice of first-line therapy in symptomatic chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients depends largely on comorbidity burden, Andrew D. Zelenetz, MD, PhD, said at the annual conference of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

“This is a disease of elderly patients. Frequently they have comorbidities,” he said. Categorizing these patients as having a low or high comorbidity burden can be done with the Cumulative Index Rating Scale score, which involves scoring of all organ systems on a 0-5 scale representing “not affected” to “extremely disabled.”

“We use this to determine first-line therapy,” said Dr. Zelenetz of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York. Dr. Zelenetz is chair of the NCCN Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Guidelines panel.

Patients with a score of greater than 12 on the 0- to 56-point scale, are “no-go” patients with respect to therapy, and are typically treated only with palliative approaches. Those with a score of 7-12 (“slow-go” patients) have a significant comorbidity burden, but can undergo treatment, thought typically to be at reduced intensity. Those with a score of 0-6 are “go-go” patients with respect to treatment, as they are physically fit, have excellent renal function, and have no significant comorbidities, he said.

Treatment options for ‘go-go’ CLL patients

Among the treatment options for the latter is FCR–the combination of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab, which was shown in the phase III CLL10 trial of patients with advanced CLL to be associated with improved complete response rates compared with the popular regimen of bendamustine and rituximab (BR), both overall and in patients under age 65. In older patients, the advantage disappeared, Dr. Zelenetz said.

FCR was also associated with improved outcomes vs. BR in patients with del(11q).

The primary endpoint of the study was progression-free survival, which favored FCR (median of 55.2 vs. 41.7 months; hazard ratio, 1.643), he said, noting that no difference was seen between the two regimens in terms of overall survival.

In a recent publication, MD Anderson Cancer Center reported its experience with its first 300 CLL patients treated with FCR. With long-term follow-up of at least 9-10 years (median of 12.8 years), patients in this trial have done extremely well.

“But interestingly, when you stratify these patients by whether they have IGHV [immunoglobulin heavy chain variable] mutated or unmutated [disease], the IGHV mutated patients have something that looks a whole lot like a survival plateau, and that survival plateau is not trivial – it’s about 60%,” he said. “So there is a group of patients with CLL who are, in fact, curable with conventional chemoimmunotherapy.

“This is an appropriate treatment for a young, fit, ‘go-go’ patient, and it has a big implication,” he said. That is, patients who are young and fit require IGHV mutation testing, as “you will absolutely choose FCR chemotherapy for the fit, young patients who has IGHV mutated disease.

“In that setting IGHV testing is now mandatory,” he stressed, noting that the benefits in this population extend to overall survival as well as progression-free survival.

Dr. Zelenetz also emphasized the need for increasing the single dose of rituximab from 375 mg/m2 during cycle 1 to 500 mg/m2 during cycles 2-6 in those receiving FCR, as this is often forgotten.

The data demonstrating the efficacy of FCR were based on this approach, he said.

Fludarabine is to be given at a dose of 25 mg/m2, and cyclophosphamide at a dose of 250 mg/m2 – both for 2-4 days during cycle 1 and for 1-3 days during cycles 2-6.

Treatment options for ‘slow-go’ CLL patients

In “slow-go” patients, an interesting approach is to use new anti-CD20 antibodies such as ofatumumab and obinutuzumab, which have features that are distinct from rituximab.

Both have been studied in CLL. The CLL11 trial compared chlorambucil, rituximab+chlorambucil, and obinutuzumab+chlorambucil, and the latest analysis showed substantial improvement in progression-free survival with obinutuzumab+chlorambucil vs. the other two regimens (26.7 months vs. 11.1 and 16.3 months, respectively), Dr. Zelenetz said, noting that rituximab+chlorambucil was also superior to chlorambucil alone, but that only the obinutuzumab regimen had an overall survival advantage vs. chlorambucil alone.

An updated analysis to be reported soon will show emerging evidence of a survival advantage of obinutuzumab+chlorambucil vs. rituximab+chlorambucil, he said.

“This suggests that obinutuzumab is a far better antibody,” he added, noting that the reasons for that are under debate, “but the way it’s given, it works better in CLL, and that, I think is unequivocal.”

A similar study looking at chlorambucil with and without ofatumumab in “slow-go” patients also demonstrated an improvement in PFS with ofatumumab, but showed “no difference whatsoever in overall survival.”

“This is actually very similar to the rituximab result, and I actually call this the ‘death of ofatumumab’ study, because clearly obinutuzumab in CLL is, I think, a superior anti-CD20 antibody,” Dr. Zelenetz said.

Studies in which obinutuzumab is substituted for rituximab in the FCR combination are currently underway as are a number of other studies of obinutuzumab, he noted.

Another treatment option in the up-front setting is ibrutinib, which was shown to be effective in the RESONATE 2 trial .

“But notice, a very, very small [complete response rate]. CRs are very difficult to achieve with ibrutinib alone, so this drug is given continuously, lifelong,” Dr. Zelenetz said, noting that it was, however, associated with an overall survival advantage vs. chlorambucil.

“Should this be the standard of care? I think it is in patients who have del(17p) or mutation of TP53. Outside of that setting, I’m still concerned about the cost of long-term tolerability of the agent,” he said.

Future of first-line CLL treatment

Avoidance of long-term therapy and conventional chemotherapy in patients with CLL is a goal, he added, noting that new understanding from studies in patients in the relapsed/refractory CLL setting – such as recent findings from a phase Ib study of venetoclax plus rituximab, which demonstrated potentially durable responses after treatment discontinuation in minimal residual disease (MRD)–negative patients – are providing insights into achieving MRD negativity that could be applied in the front line treatment setting.

“We’re still trying to figure out how to best use this. We want to try to use some of this knowledge about achievement of MRD negativity in the up-front setting so we don’t have to give patients long-term therapy, and we would like to avoid conventional chemotherapy,” he said. “So I’m hoping we’re going to be able to replace chronic long-term therapy of CLL with a defined course of treatment with high levels of MRD negativity.”

Dr. Zelenetz reported receiving consulting fees, honoraria, and/or grant/research support from Acerta Pharma, Amgen Inc., BeiGene, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene Corporation, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Janssen Pharmaceutica Products, MEI Pharma, NanoString Technologies, Pharmacyclics, Portola Pharmaceuticals, Roche Laboratories, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE NCCN ANNUAL CONFERENCE

CLL boost in PFS came at high cost in side effects

Add-on idelalisib boosted the progression-free survival (PFS) of patients with relapsed and refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia by over 9 months in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 416 participants. But that improvement came at the price of a 4% absolute increase in treatment-emergent adverse events leading to death.

At a median follow-up of 14 months, the median PFS was 20.8 months in the 207 patients in the idelalisib group and 11.1 months in the 209 patients in the placebo group. However, 11% of patients in the idelalisib group and 7% of those in the placebo group had treatment-related adverse events that resulted in death.

Overall, 68% of those in the idelalisib group, and 44% in the placebo group, had serious adverse events that included febrile neutropenia, pneumonia, and pyrexia. Six deaths resulted from infections in the idelalisib group, and three deaths resulted from infections in the placebo group.

All 416 participants in the international, multicenter study had measurable lymphadenopathy by CT or MRI and progression of chronic lymphocytic leukemia within 36 months of their last therapy. Patients were stratified by high-risk genetic mutations (IGHV, del[17p], or TP53) and refractory versus relapsed disease. Participants were randomly assigned to receive daily idelalisib or placebo, plus a maximum of six cycles of bendamustine and rituximab.

The primary endpoint of PFS was assessed by an independent review committee in the intention-to-treat population.

A 150 mg dose of idelalisib or placebo was given twice daily until disease progressed or drug-related toxicity was intolerable. Bendamustine was given intravenously at 70 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2 for six 28-day cycles. Rituximab was given at 375 mg/m2 on day 1 of cycle 1 and at 500 mg/m2 on day 1 of cycles 2–6.

The trial is ongoing, the researchers reported.

The trial is funded by Gilead Sciences, the maker of idelalisib (Zydelig). Dr. Zelenetz disclosed consulting with multiple drug companies, including Gilead.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryjodales

Add-on idelalisib boosted the progression-free survival (PFS) of patients with relapsed and refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia by over 9 months in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 416 participants. But that improvement came at the price of a 4% absolute increase in treatment-emergent adverse events leading to death.

At a median follow-up of 14 months, the median PFS was 20.8 months in the 207 patients in the idelalisib group and 11.1 months in the 209 patients in the placebo group. However, 11% of patients in the idelalisib group and 7% of those in the placebo group had treatment-related adverse events that resulted in death.

Overall, 68% of those in the idelalisib group, and 44% in the placebo group, had serious adverse events that included febrile neutropenia, pneumonia, and pyrexia. Six deaths resulted from infections in the idelalisib group, and three deaths resulted from infections in the placebo group.

All 416 participants in the international, multicenter study had measurable lymphadenopathy by CT or MRI and progression of chronic lymphocytic leukemia within 36 months of their last therapy. Patients were stratified by high-risk genetic mutations (IGHV, del[17p], or TP53) and refractory versus relapsed disease. Participants were randomly assigned to receive daily idelalisib or placebo, plus a maximum of six cycles of bendamustine and rituximab.

The primary endpoint of PFS was assessed by an independent review committee in the intention-to-treat population.

A 150 mg dose of idelalisib or placebo was given twice daily until disease progressed or drug-related toxicity was intolerable. Bendamustine was given intravenously at 70 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2 for six 28-day cycles. Rituximab was given at 375 mg/m2 on day 1 of cycle 1 and at 500 mg/m2 on day 1 of cycles 2–6.

The trial is ongoing, the researchers reported.

The trial is funded by Gilead Sciences, the maker of idelalisib (Zydelig). Dr. Zelenetz disclosed consulting with multiple drug companies, including Gilead.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryjodales

Add-on idelalisib boosted the progression-free survival (PFS) of patients with relapsed and refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia by over 9 months in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 416 participants. But that improvement came at the price of a 4% absolute increase in treatment-emergent adverse events leading to death.

At a median follow-up of 14 months, the median PFS was 20.8 months in the 207 patients in the idelalisib group and 11.1 months in the 209 patients in the placebo group. However, 11% of patients in the idelalisib group and 7% of those in the placebo group had treatment-related adverse events that resulted in death.

Overall, 68% of those in the idelalisib group, and 44% in the placebo group, had serious adverse events that included febrile neutropenia, pneumonia, and pyrexia. Six deaths resulted from infections in the idelalisib group, and three deaths resulted from infections in the placebo group.

All 416 participants in the international, multicenter study had measurable lymphadenopathy by CT or MRI and progression of chronic lymphocytic leukemia within 36 months of their last therapy. Patients were stratified by high-risk genetic mutations (IGHV, del[17p], or TP53) and refractory versus relapsed disease. Participants were randomly assigned to receive daily idelalisib or placebo, plus a maximum of six cycles of bendamustine and rituximab.

The primary endpoint of PFS was assessed by an independent review committee in the intention-to-treat population.

A 150 mg dose of idelalisib or placebo was given twice daily until disease progressed or drug-related toxicity was intolerable. Bendamustine was given intravenously at 70 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2 for six 28-day cycles. Rituximab was given at 375 mg/m2 on day 1 of cycle 1 and at 500 mg/m2 on day 1 of cycles 2–6.

The trial is ongoing, the researchers reported.

The trial is funded by Gilead Sciences, the maker of idelalisib (Zydelig). Dr. Zelenetz disclosed consulting with multiple drug companies, including Gilead.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryjodales

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Add-on idelalisib boosted the progression-free survival of patients with relapsed and refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia by over 9 months.

Data source: A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 416 participants.

Disclosures: Gilead Sciences, the maker of idelalisib (Zydelig), sponsored the study. Dr. Zelenetz disclosed consulting with multiple drug companies, including Gilead.

CAR designers report high B-cell cancer response rates

ORLANDO – Patients with advanced hematologic malignancies of B-cell lineage had robust immune responses following infusion of a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)–T-cell construct designed to deliver a specific balance of antigens, investigators reported.

Adults with relapsed or refractory B-lineage acute myeloid leukemia (ALL), non–Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who received a CAR-T cell construct consisting of autologous CD4-positive and CD-8-positive T cells that were transduced separately, recombined, and then delivered in a single infusion had comparatively high overall response and complete response rates, reported Cameron Turtle, MBBS, PhD, from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle.

“We know that patients have a highly variable CD4 to CD8 ratio, so by actually controlling this and separately transducing, expanding, and then reformulating in this defined composition, we’re able to eliminate one source of variability in CAR-T cell products,” Dr. Turtle said at the ASCO-SITC Clinical Immuno-Oncology Symposium.

In preclinical studies, an even balance of CD4-positive and CD8-positive central memory T cells or naive T cells evoked more potent immune responses against B-cell malignancies in mice than CD19-positive cells, he explained

To see whether this would also hold true in humans, the investigators enrolled into a phase I/II trial adults with relapsed/refractory B-cell malignancies, including ALL (36 patients), NHL (41), and CLL (24). No patients were excluded on the basis of either absolute lymphocyte, circulating tumors cells, history of stem cell transplant, or results of in vitro test expansions.

All patients underwent leukapheresis for harvesting of T-cells, and populations of CD4- and CD8-positive cells were separated and transduced with a lentiviral vector to express a CD19 CAR and a truncated human epidermal growth factor receptor that allowed tracing of the transduced cells via flow cytometry. The patients underwent lymphodepleting chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide (for the earliest patients), or cyclophosphamide plus fludarabine. Fifteen days after leukapheresis, the separated, transduced, and expanded cells were combined and delivered back to patients in a single infusion at one of three dose levels: 2 x 105, 2 x 106, or 2 x 107 CAR-T cells/kg.

ALL results

Two of the 36 patients with ALL died from complications of the CAR-T cell infusion process prior to evaluation. The 34 remaining patients all had morphologic bone marrow complete responses (CR). Of this group, 32 also had bone marrow CR on flow cytometry.

Using immunoglobulin H (IgH) deep sequencing in a subset of 20 patients 3 weeks after CAR-T cell infusion, the investigators could not detect the malignant IgH index clone in 13 of the patients, and found fewer than 10 copies in the bone marrow of 5 patients.

Six of seven patients with extramedullary disease at baseline had a complete response. The remaining patient in this group had an equivocal PET scan result, and experienced a relapse 2 months after assessment.

The investigators also determined that the lymphodepletion regimen may affect overall results, based on the finding that 10 of 12 patients who received cyclophosphamide alone achieved a CR, but seven of these 10 patients had a relapse within a few months. Of these seven patients. five received a second T-cell infusion, but none had significant T-cell expansion. The investigators traced the failure of the second attempt to a CD8-mediated transgene immune response to a murine single-chain variable fragment used in the construct.

For subsequent patients, they altered the lymphodepletion regimen to include fludarabine to prevent priming of the anti-CAR transgenic immune response. This modification resulted in improved progression-free survival and overall survival for subsequent patients receiving a second infusion, Dr. Turtle said.

NHL results

Of the 41 patients with NHL, 30 (73%) had aggressive histologies, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell, and Burkitt lymphomas, and 11 (27%) had indolent histologies, including mantle cell and follicular lymphomas. Most of the patients had received multiple prior lines of therapy, and 19 (46%) had undergone either an autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplant.

Of the 39 evaluable patients who completed therapy, the overall response rate was 67%, including 13 (39%) with CR. Dr. Turtle noted that the CR rate was substantially higher among patients who received cyclophosphamide and fludarabine lymphodepletion, compared with cyclophosphamide alone.

There were also a few responses, including two CRs, among patients with indolent histologies, he said.

CLL, safety results

All 24 patients with CLL had previously received ibrutinib (Imbruvica). Of this group, 19 either had no significant responses to the drug, inactivating mutations, or intolerable toxicities. All but 1 of the 24 patients also had high-risk cytogenetics.

Of the 16 ibrutinib-refractory patients who were evaluable for restaging, 14 had no evidence of disease in bone marrow by flow cytometry at 4 weeks. The overall response rate in this group was 69%, which included four CRs.

Among a majority of all patients, toxicity with the CAR-T cell therapy was mild to moderate. Early cytokine changes appeared to be predictive of serious adverse events such as the cytokine release syndrome, a finding that may allow clinicians to intervene early to prevent complications, Dr. Turtle said.

In the CAR-T cell therapy, “multiple things affect the response and toxicity, including CAR T-cell dose, disease burden, the anti-CAR transgene immune response and the lymphodepletion regimen, not to mention other patient factors that we’re still sorting out,” he commented.

The trial was funded by the National Institutes of Health, Life Science Development Fund, Juno Therapeutics and the Bezos Family Foundation. Dr. Turtle disclosed consultancy, honoraria, and/or research funding from Juno Therapeutics and Seattle Genetics.

ORLANDO – Patients with advanced hematologic malignancies of B-cell lineage had robust immune responses following infusion of a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)–T-cell construct designed to deliver a specific balance of antigens, investigators reported.

Adults with relapsed or refractory B-lineage acute myeloid leukemia (ALL), non–Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who received a CAR-T cell construct consisting of autologous CD4-positive and CD-8-positive T cells that were transduced separately, recombined, and then delivered in a single infusion had comparatively high overall response and complete response rates, reported Cameron Turtle, MBBS, PhD, from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle.

“We know that patients have a highly variable CD4 to CD8 ratio, so by actually controlling this and separately transducing, expanding, and then reformulating in this defined composition, we’re able to eliminate one source of variability in CAR-T cell products,” Dr. Turtle said at the ASCO-SITC Clinical Immuno-Oncology Symposium.

In preclinical studies, an even balance of CD4-positive and CD8-positive central memory T cells or naive T cells evoked more potent immune responses against B-cell malignancies in mice than CD19-positive cells, he explained

To see whether this would also hold true in humans, the investigators enrolled into a phase I/II trial adults with relapsed/refractory B-cell malignancies, including ALL (36 patients), NHL (41), and CLL (24). No patients were excluded on the basis of either absolute lymphocyte, circulating tumors cells, history of stem cell transplant, or results of in vitro test expansions.

All patients underwent leukapheresis for harvesting of T-cells, and populations of CD4- and CD8-positive cells were separated and transduced with a lentiviral vector to express a CD19 CAR and a truncated human epidermal growth factor receptor that allowed tracing of the transduced cells via flow cytometry. The patients underwent lymphodepleting chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide (for the earliest patients), or cyclophosphamide plus fludarabine. Fifteen days after leukapheresis, the separated, transduced, and expanded cells were combined and delivered back to patients in a single infusion at one of three dose levels: 2 x 105, 2 x 106, or 2 x 107 CAR-T cells/kg.

ALL results

Two of the 36 patients with ALL died from complications of the CAR-T cell infusion process prior to evaluation. The 34 remaining patients all had morphologic bone marrow complete responses (CR). Of this group, 32 also had bone marrow CR on flow cytometry.

Using immunoglobulin H (IgH) deep sequencing in a subset of 20 patients 3 weeks after CAR-T cell infusion, the investigators could not detect the malignant IgH index clone in 13 of the patients, and found fewer than 10 copies in the bone marrow of 5 patients.

Six of seven patients with extramedullary disease at baseline had a complete response. The remaining patient in this group had an equivocal PET scan result, and experienced a relapse 2 months after assessment.

The investigators also determined that the lymphodepletion regimen may affect overall results, based on the finding that 10 of 12 patients who received cyclophosphamide alone achieved a CR, but seven of these 10 patients had a relapse within a few months. Of these seven patients. five received a second T-cell infusion, but none had significant T-cell expansion. The investigators traced the failure of the second attempt to a CD8-mediated transgene immune response to a murine single-chain variable fragment used in the construct.

For subsequent patients, they altered the lymphodepletion regimen to include fludarabine to prevent priming of the anti-CAR transgenic immune response. This modification resulted in improved progression-free survival and overall survival for subsequent patients receiving a second infusion, Dr. Turtle said.

NHL results

Of the 41 patients with NHL, 30 (73%) had aggressive histologies, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell, and Burkitt lymphomas, and 11 (27%) had indolent histologies, including mantle cell and follicular lymphomas. Most of the patients had received multiple prior lines of therapy, and 19 (46%) had undergone either an autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplant.

Of the 39 evaluable patients who completed therapy, the overall response rate was 67%, including 13 (39%) with CR. Dr. Turtle noted that the CR rate was substantially higher among patients who received cyclophosphamide and fludarabine lymphodepletion, compared with cyclophosphamide alone.

There were also a few responses, including two CRs, among patients with indolent histologies, he said.

CLL, safety results

All 24 patients with CLL had previously received ibrutinib (Imbruvica). Of this group, 19 either had no significant responses to the drug, inactivating mutations, or intolerable toxicities. All but 1 of the 24 patients also had high-risk cytogenetics.

Of the 16 ibrutinib-refractory patients who were evaluable for restaging, 14 had no evidence of disease in bone marrow by flow cytometry at 4 weeks. The overall response rate in this group was 69%, which included four CRs.

Among a majority of all patients, toxicity with the CAR-T cell therapy was mild to moderate. Early cytokine changes appeared to be predictive of serious adverse events such as the cytokine release syndrome, a finding that may allow clinicians to intervene early to prevent complications, Dr. Turtle said.

In the CAR-T cell therapy, “multiple things affect the response and toxicity, including CAR T-cell dose, disease burden, the anti-CAR transgene immune response and the lymphodepletion regimen, not to mention other patient factors that we’re still sorting out,” he commented.

The trial was funded by the National Institutes of Health, Life Science Development Fund, Juno Therapeutics and the Bezos Family Foundation. Dr. Turtle disclosed consultancy, honoraria, and/or research funding from Juno Therapeutics and Seattle Genetics.

ORLANDO – Patients with advanced hematologic malignancies of B-cell lineage had robust immune responses following infusion of a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)–T-cell construct designed to deliver a specific balance of antigens, investigators reported.

Adults with relapsed or refractory B-lineage acute myeloid leukemia (ALL), non–Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who received a CAR-T cell construct consisting of autologous CD4-positive and CD-8-positive T cells that were transduced separately, recombined, and then delivered in a single infusion had comparatively high overall response and complete response rates, reported Cameron Turtle, MBBS, PhD, from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle.

“We know that patients have a highly variable CD4 to CD8 ratio, so by actually controlling this and separately transducing, expanding, and then reformulating in this defined composition, we’re able to eliminate one source of variability in CAR-T cell products,” Dr. Turtle said at the ASCO-SITC Clinical Immuno-Oncology Symposium.

In preclinical studies, an even balance of CD4-positive and CD8-positive central memory T cells or naive T cells evoked more potent immune responses against B-cell malignancies in mice than CD19-positive cells, he explained

To see whether this would also hold true in humans, the investigators enrolled into a phase I/II trial adults with relapsed/refractory B-cell malignancies, including ALL (36 patients), NHL (41), and CLL (24). No patients were excluded on the basis of either absolute lymphocyte, circulating tumors cells, history of stem cell transplant, or results of in vitro test expansions.

All patients underwent leukapheresis for harvesting of T-cells, and populations of CD4- and CD8-positive cells were separated and transduced with a lentiviral vector to express a CD19 CAR and a truncated human epidermal growth factor receptor that allowed tracing of the transduced cells via flow cytometry. The patients underwent lymphodepleting chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide (for the earliest patients), or cyclophosphamide plus fludarabine. Fifteen days after leukapheresis, the separated, transduced, and expanded cells were combined and delivered back to patients in a single infusion at one of three dose levels: 2 x 105, 2 x 106, or 2 x 107 CAR-T cells/kg.

ALL results

Two of the 36 patients with ALL died from complications of the CAR-T cell infusion process prior to evaluation. The 34 remaining patients all had morphologic bone marrow complete responses (CR). Of this group, 32 also had bone marrow CR on flow cytometry.

Using immunoglobulin H (IgH) deep sequencing in a subset of 20 patients 3 weeks after CAR-T cell infusion, the investigators could not detect the malignant IgH index clone in 13 of the patients, and found fewer than 10 copies in the bone marrow of 5 patients.

Six of seven patients with extramedullary disease at baseline had a complete response. The remaining patient in this group had an equivocal PET scan result, and experienced a relapse 2 months after assessment.

The investigators also determined that the lymphodepletion regimen may affect overall results, based on the finding that 10 of 12 patients who received cyclophosphamide alone achieved a CR, but seven of these 10 patients had a relapse within a few months. Of these seven patients. five received a second T-cell infusion, but none had significant T-cell expansion. The investigators traced the failure of the second attempt to a CD8-mediated transgene immune response to a murine single-chain variable fragment used in the construct.

For subsequent patients, they altered the lymphodepletion regimen to include fludarabine to prevent priming of the anti-CAR transgenic immune response. This modification resulted in improved progression-free survival and overall survival for subsequent patients receiving a second infusion, Dr. Turtle said.

NHL results

Of the 41 patients with NHL, 30 (73%) had aggressive histologies, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell, and Burkitt lymphomas, and 11 (27%) had indolent histologies, including mantle cell and follicular lymphomas. Most of the patients had received multiple prior lines of therapy, and 19 (46%) had undergone either an autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplant.

Of the 39 evaluable patients who completed therapy, the overall response rate was 67%, including 13 (39%) with CR. Dr. Turtle noted that the CR rate was substantially higher among patients who received cyclophosphamide and fludarabine lymphodepletion, compared with cyclophosphamide alone.

There were also a few responses, including two CRs, among patients with indolent histologies, he said.

CLL, safety results

All 24 patients with CLL had previously received ibrutinib (Imbruvica). Of this group, 19 either had no significant responses to the drug, inactivating mutations, or intolerable toxicities. All but 1 of the 24 patients also had high-risk cytogenetics.

Of the 16 ibrutinib-refractory patients who were evaluable for restaging, 14 had no evidence of disease in bone marrow by flow cytometry at 4 weeks. The overall response rate in this group was 69%, which included four CRs.

Among a majority of all patients, toxicity with the CAR-T cell therapy was mild to moderate. Early cytokine changes appeared to be predictive of serious adverse events such as the cytokine release syndrome, a finding that may allow clinicians to intervene early to prevent complications, Dr. Turtle said.

In the CAR-T cell therapy, “multiple things affect the response and toxicity, including CAR T-cell dose, disease burden, the anti-CAR transgene immune response and the lymphodepletion regimen, not to mention other patient factors that we’re still sorting out,” he commented.

The trial was funded by the National Institutes of Health, Life Science Development Fund, Juno Therapeutics and the Bezos Family Foundation. Dr. Turtle disclosed consultancy, honoraria, and/or research funding from Juno Therapeutics and Seattle Genetics.

AT THE CLINICAL IMMUNO-ONCOLOGY SYMPOSIUM

Key clinical point: A defined CAR-T cell construct was associated with high response rates in patients with B-cell malignancies.

Major finding: The overall response rate among patients with ibrutinib-refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia was 69%, including four complete responses.

Data source: Phase I/II dose-finding, safety and efficacy study in patients with B-lineage hematologic malignancies

Disclosures: The trial was funded by the National Institutes of Health, Life Science Development Fund, Juno Therapeutics and the Bezos Family Foundation. Dr. Turtle disclosed consultancy, honoraria, and/or research funding from Juno Therapeutics and Seattle Genetics.

Ublituximab was safe, highly active in rituximab-pretreated B-cell NHL, CLL

The investigational anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody ublituximab is safe and has good antitumor activity in patients with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (B-NHL) or chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who have previously received the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab, results from a phase I/II trial suggest.

Ublituximab is engineered to have a low fucose content. This feature gives it enhanced antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity relative to other anti-CD20 antibodies, especially against tumors having low expression of that protein, as may occur in the development of rituximab resistance.

In the trial, nearly half of the 35 patients studied had a complete or partial response to ublituximab, including nearly one-third of those whose disease was refractory to rituximab (Rituxan) (Br J Haematol. 2017 Apr;177[2]:243-53). The main adverse events were infusion-related reactions, fatigue, pyrexia, and diarrhea, but almost all were lower grade.

“Ublituximab was well tolerated and efficacious in a heterogeneous and highly rituximab–pretreated patient population,” said the investigators, who were led by Ahmed Sawas, MD, at the Center for Lymphoid Malignancies, Columbia University Medical Center, N.Y.

The observed response rate is much the same as those seen with two other anti-CD20 antibodies – obinutuzumab (Gazyva)and ofatumumab (Arzerra)– in similar patient populations, and ublituximab may have advantages in terms of fewer higher-grade infusion-related reactions and shorter infusion time.

“Enhanced anti-CD20 [monoclonal antibodies] that are well tolerated and active in rituximab-resistant disease can provide meaningful clinical benefit to patients with limited treatment options,” the investigators noted.

The trial enrolled 27 patients with B-NHL and 8 patients with CLL (or small lymphocytic lymphoma) who had rituximab-refractory disease (defined by progression on or within 6 months of receiving that agent) or rituximab-relapsed disease (defined by progression more than 6 months after receiving it). They had received a median of three prior therapies.

The patients were treated on an open-label basis with ublituximab at various doses as induction therapy (3-4 weekly infusions during cycles 1 and 2) and then as maintenance therapy (monthly during cycles 3-5, then once every 3 months for up to 2 years). All patients received an oral antihistamine and steroids before infusions.

By the end of the trial, 60% of patients had discontinued treatment because of progression; 23% had discontinued because of adverse events, physician decision, or other reasons; and the remaining 17% had received all planned treatment, Dr. Sawas and his coinvestigators reported.

None of the patients experienced dose-limiting toxicities or unexpected adverse events. The rate of any-grade adverse events was 100%, and the rate specifically of grade 3/4 adverse events was 49%. The rate of serious adverse events (most commonly pneumonia) was 37%.

The leading nonhematologic adverse events were infusion-related reactions (40%; grade 3/4, 0%), fatigue (37%; grade 3/4, 3%), pyrexia (29%; grade 3/4, 0%), and diarrhea (26%; grade 3/4, 0%).

The leading hematologic adverse events were neutropenia (14%; grade 3/4, 14%), with no associated infections; anemia (11%; grade 3/4, 6%); and thrombocytopenia (6%; grade 3/4, 6%), with no associated bleeding.