User login

Older-age bipolar disorder: A case series

Although the peak age of onset of bipolar disorder (BD) is between 20 and 40 years,1 some patients develop BD later in life. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force has classified the illness into 3 categories:

- early-onset bipolar disorder (EOBD), in which the first manic episode occurs before age 40

- late-onset bipolar disorder (LOBD), in which the initial manic/hypomanic episode occurs after age 50

- older-age bipolar disorder (OABD), in which the first manic/hypomanic episode occurs after age 60.2

OABD represents 25% of the population with BD.3 OABD differs from EOBD in its clinical presentation, biological factors, and psychiatric and somatic comorbidities.4 Studies suggest OABD warrants a more extensive workup to rule out organic causes because symptoms are often attributable to a variety of organic etiologies.

This article describes 3 cases of OABD, including treatments and outcomes. We discuss general treatment recommendations for patients with OABD as cited in the literature. Further research is needed to expand our ability to better care for this unique population.

CASE 1

Mr. D was a 66-year-old African American male with no psychiatric history. His medical history was significant for hypertension, poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease. One year ago, he was diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma, and underwent uncomplicated right trisegmentectomy, resection of extrahepatic biliary tree, and complete portal lymphadenectomy, with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy to 2 intrahepatic ducts. He presented to the emergency department (ED) with disorganized behavior for 3 weeks. During that time, Mr. D reported increased distractibility, irritability, hyper-religiosity, racing thoughts, decreased appetite, and decreased need for sleep. There was no pertinent family history.

On mental status examination, Mr. D was agitated, noncooperative, and guarded. His speech was loud and pressured. Mr. D was distractible, tangential, and goal-directed. His Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) score was 31, which is highly indicative of mania.5 Computed tomography (CT) scan of the head (Figure 1)

CASE 2

Mr. M was a 63-year-old African American male with no psychiatric history and a medical history significant for hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. He presented to the ED with behavioral changes for 2 weeks. During this time, he experienced decreased need for sleep, agitation, excessive spending, self-conversing, hypersexuality, and paranoia. His family history was significant for schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type.

A mental status examination revealed pressured speech, grandiose delusions, hyper-religiosity, flight of ideas, looseness of association, auditory hallucinations, and tangential thought processes. Mr. M’s initial YMRS score was 56. A CT scan of the head revealed no acute abnormality, but MRI of the brain (Figure 2) showed chronic microvascular ischemic change. Mr. M was diagnosed with bipolar I disorder and admitted. He was started on quetiapine extended release, which was titrated to 600 mg nightly. Divalproex sodium extended release was titrated to 1,500 mg nightly, with subsequent improvement. At discharge, his YMRS score was 15.

Continue to: CASE 3

CASE 3

Ms. F was a 69-year-old White female with no psychiatric history. Her medical history was significant for hypertension, osteoarthritis, and stage III-C ovarian adenocarcinoma with a debulking surgical procedure 5 years earlier. After that, she received adjuvant therapy with paclitaxel and carboplatin, which resulted in a 10-month disease-free interval. Subsequent progression led to cycles of doxorubicin liposomal and gemcitabine. She was in remission until 1 week earlier, when a CT scan of the abdomen/pelvis showed recurrence. She presented to the hospital after disrobing in the street due to hyper-religiosity and divine instruction. She endorsed elevated mood and increased energy despite sleeping only 2 hours daily. Her family psychiatric history was significant for her daughter’s suicide attempt.

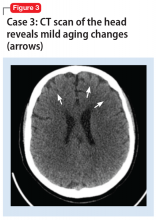

A mental status examination revealed disorganized behavior and agitation. Her speech was loud and pressured. She described a “great” mood with congruent affect. Her thought process was circumstantial and illogical. She displayed flight of ideas, grandiose delusions, and paranoia. Ms. F’s initial YMRS score was 38. Vital signs were significant for an elevated blood pressure of 153/113 mm Hg. A CT scan of the head (Figure 3) showed age-related change with no acute findings. Ms. F was admitted with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder and prescribed olanzapine, 2.5 mg nightly. Due to continued manic symptoms, olanzapine was discontinued, and Ms. F was started on quetiapine, 300 mg nightly, with subsequent improvement. At discharge, her YMRS score was 10.

Differences between EOBD and OABD

BD has always been considered a multi-system illness; however, comorbidity is much more common in OABD than in EOBD. Comorbid conditions are 3 to 4 times more common in patients with OABD.2 Common comorbidities include metabolic syndrome, allergic rhinitis, arthritis, asthma, and cardiovascular disease.

Compared with younger individuals, older patients with BD score lower on the YMRS in the areas of increased activity-energy, language-thought disorder, and sexual interest.6 Psychotic symptoms are less common or less severe in OABD. Although symptom severity is lower, the prevalence of rapid cycling illness is 20% higher in patients with OABD.6 OABD is less commonly associated with a family history.7 This may suggest a difference from the popular genetic component typically found in patients with EOBD.

Cognitive impairment is more commonly found in OABD. Patients with OABD suffer from neuropsychological deficits even during euthymic phases.8 While these deficits may also be found in patients with EOBD, compared with younger patients, older adults are more susceptible to accelerated decline in cognition. OABD can first present within the context of cardiovascular or neuropsychological impairment. It has also been linked to a greater prevalence of white matter hyperintensities compared with EOBD.9,10

Continue to: Treatment is not specific to OABD

Treatment is not specific to OABD

No established treatment guidelines specifically address OABD. It has been treated similarly to EOBD, with antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, antidepressants, and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Although lithium is effective, special precautions should be taken when prescribing it to older adults because these patients may be more sensitive to adverse events.11 Drug–drug interactions may also be more likely due to concomitant use of medications for common medical issues such as hypertension.

Treatment with antipsychotics in older patients carries risks. Use of antipsychotics may result in higher rates of morbidity and mortality related to cardiovascular, metabolic, and infectious etiologies. Some literature recommends the use of antipsychotics for OABD; however, the potential benefits must outweigh the risks.6 Monotherapy followed by combination therapy has demonstrated effectiveness in OABD.11 Because symptoms of OABD are often less severe, it may be best to avoid maintenance antipsychotic therapy when possible. With a higher prevalence of depressed mood following manic episodes, use of antidepressant therapy is common in OABD.6 ECT should be considered for patients with treatment-refractory BD.11

Lessons from our case series

Our case series included 3 patients with OABD. These patients’ comorbid conditions included hypertension, hypercholesteremia, and diabetes mellitus. Two patients had a history of cancer, but there was no metastasis to the brain in either case. However, we considered the possibility of structural changes in the brain or cognitive impairment secondary to cancer or its treatment. A literature review confirmed that adult patients treated for noncentral nervous system cancer experienced cancer-related cognitive impairment (CRCI).12 New research suggests that CRCI could be related to altered neuronal integrity along with a disturbance of brain structure networks that process and integrate information.13

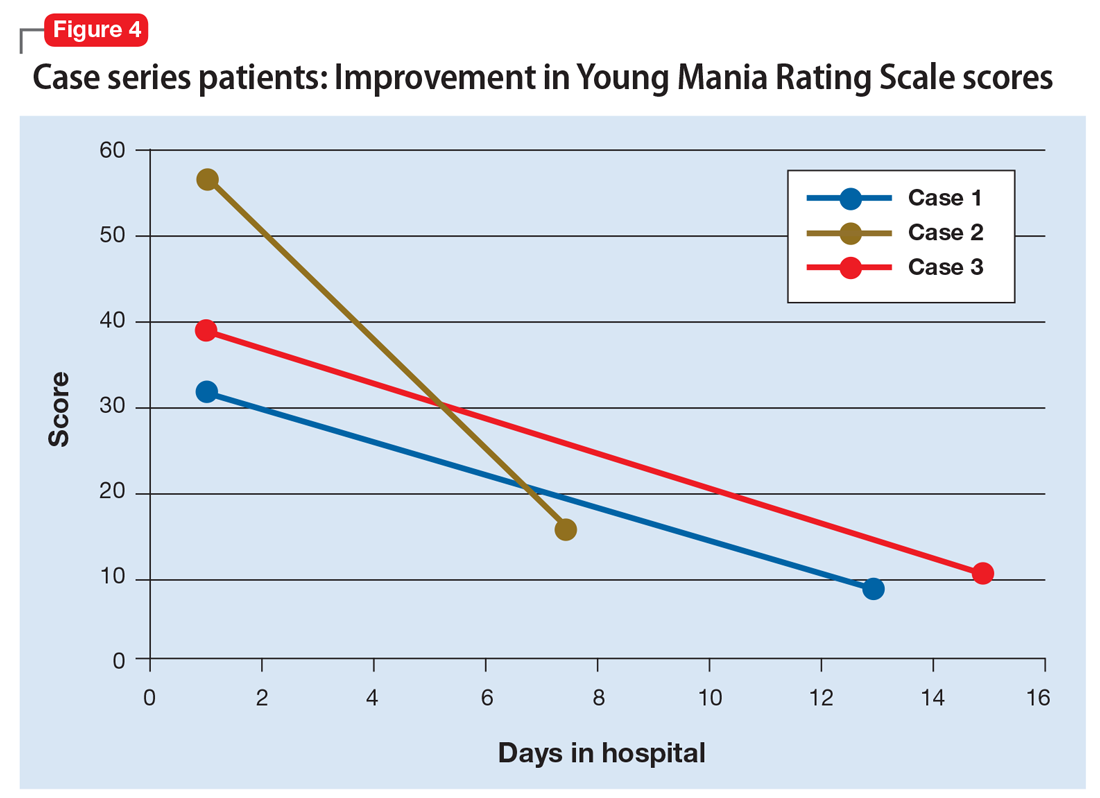

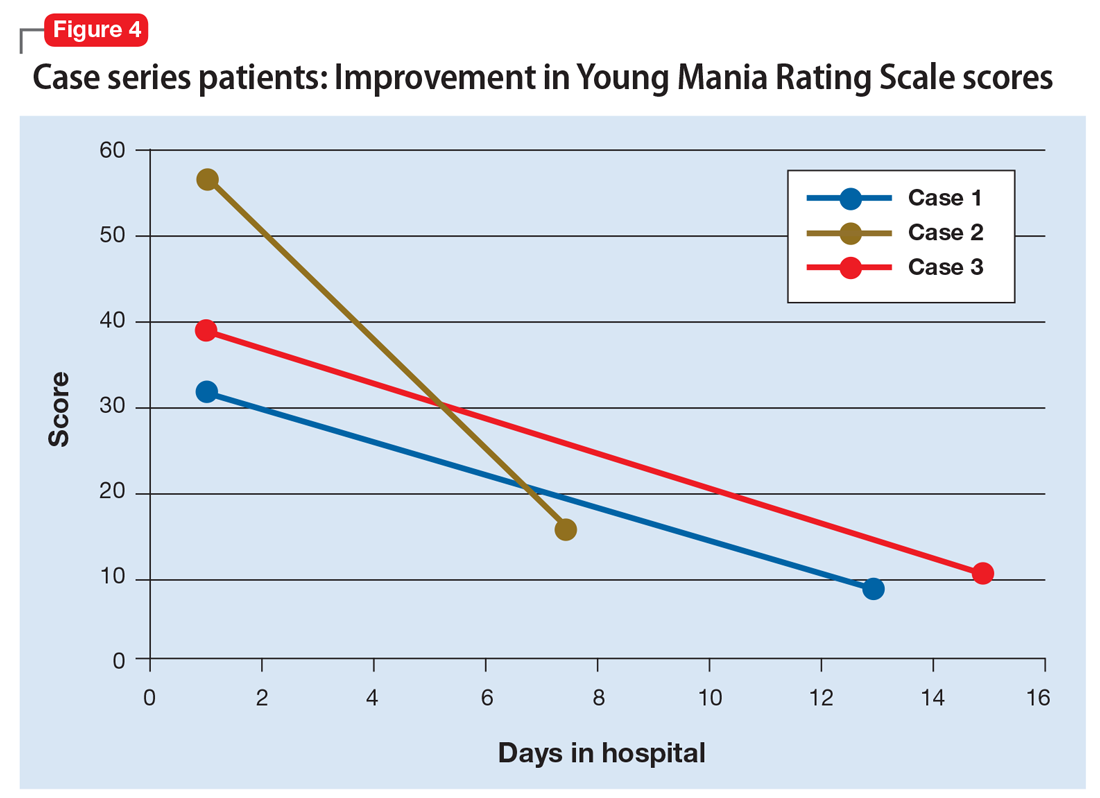

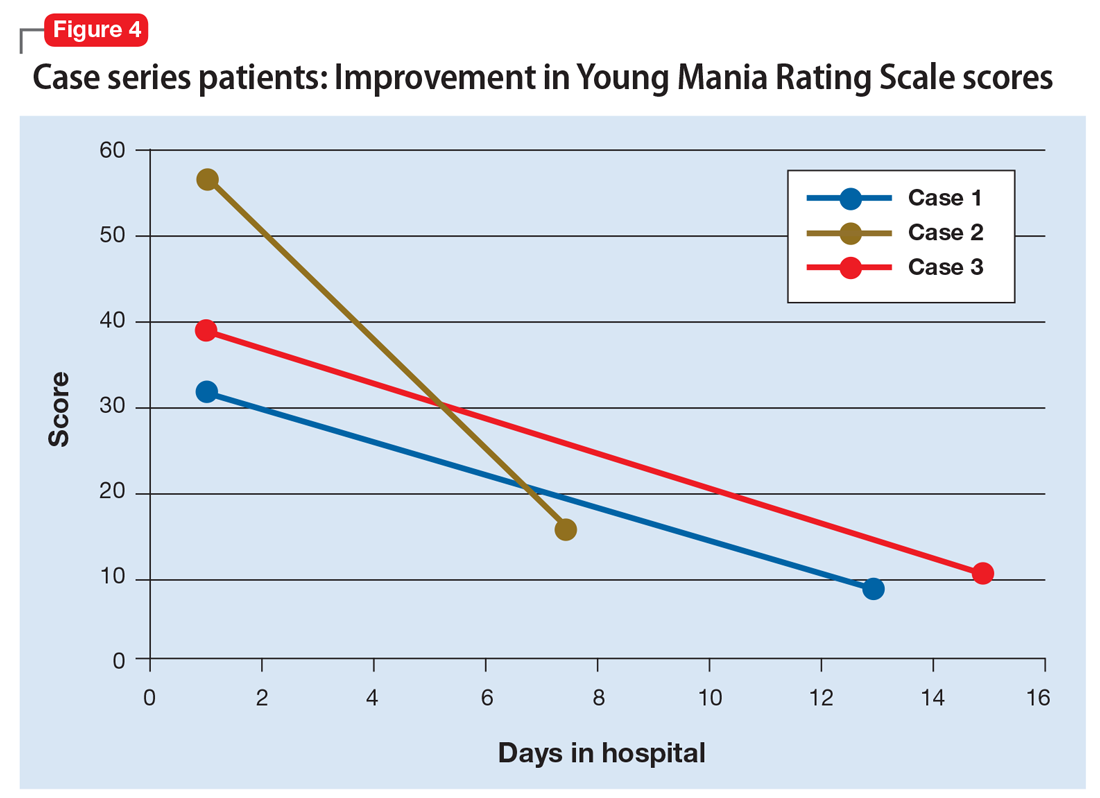

We used the YMRS to compare symptom severity and treatment response (Figure 4). Two patients were treated with atypical antipsychotics with a mood stabilizer, and the third patient was prescribed an antipsychotic only. We avoided lithium and carbamazepine as mood stabilizers due to their adverse effect profiles and potential for drug–drug interactions. Each patient responded well to treatment without adverse events.

Future studies are needed to clearly define the safest and most effective treatment guidelines in patients with OABD. We believe that OABD may require the development of a unique treatment algorithm due to the high likelihood of medical comorbidity and age-related variations in treatment response.

Continue to: Etiology of OABD may be different

Etiology of OABD may be different

OABD may be associated with manic presentations and vascular risk factors. MRI imaging that found more white matter hyperintensities and cerebrovascular lesions in patients with OABD compared with younger patients provides evidence of possible differing etiologies.14 Cassidy and Carroll15 found a higher incidence of smoking, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, and atrial fibrillation in patients in the older onset group. Bellivier et al16 proposed 3 subgroups of bipolar I disorder; the late-onset subgroup’s etiology was multifactorial. EOBD and OABD subgroups have similar gender ratios,17 first-episode descriptions, and alcohol use rates; however, OABD subgroups have more neurological comorbidity, lesser severe psychosis, and less genetic predisposition.

Although 25% of BD cases are late onset,3 there is still little consensus regarding subgroups and etiological causes. Therefore, additional research specifically focusing on vascular risks may provide much-needed information. Controlling and mitigating vascular risks in OABD may affect its development and course. Despite debated etiologies, the treatment of BD remains consistent, with anticonvulsants preferred over lithium in older individuals.

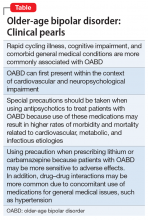

The Table summarizes clinical pearls about the features and treatment of OABD.

Bottom Line

Compared with younger patients with bipolar disorder (BD), those who develop BD later in life may be more likely to have rapid cycling, medical comorbidities, and cognitive impairment. Older patients with BD also may be more likely to experience adverse effects of the medications commonly used to treat BD, including antipsychotics, lithium, and carbamazepine.

Related Resources

- Carlino AR, Stinnett JL, Kim DR. New onset of bipolar disorder in late life. Psychosomatics. 2013;54(1):94-97.

- Sajatovic M, Kales HC, Mulsant BH. Prescribing antipsychotics in geriatric patients: Focus on schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(10):20-26,28.

Drug Brand Names

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, Tegretol

Carboplatin • Paraplatin

Divalproex sodium • Depakote

Doxorubicin liposome injection • Doxil

Gemcitabine injection • Gemzar

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paclitaxel injection • Abraxane

Quetiapine • Seroquel

1. Prabhakar D, Balon R. Late-onset bipolar disorder: a case for careful appraisal. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2010;7(1):34-37.

2. Sajatovic M, Strejilevich SA, Gildengers AG, et al. A report on older-age bipolar disorder from the International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17(7):689-704.

3. Arciniegas DB. New-onset bipolar disorder in late life: a case of mistaken identity. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(2):198-203.

4. Chou P-H, Tseng W-J, Chen L-M, et al. Late onset bipolar disorder: a case report and review of the literature. Journal of Clinical Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2015;6(1):27-29.

5. Lukasiewicz M, Gerard S, Besnard A, et al; Emblem Study Group. Young Mania Rating Scale: how to interpret the numbers? Determination of a severity threshold and of the minimal clinically significant difference in the EMBLEM cohort. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2013;22(1):46-58.

6. Oostervink F, Boomsma MM, Nolen WA; EMBLEM Advisory Board. Bipolar disorder in the elderly; different effects of age and of age of onset. J Affect Disord. 2009;116(3):176-183.

7. Depp CA, Jeste D V. Bipolar disorder in older adults: A critical review. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6(5):343-367.8.

8. Gildengers AG, Butters MA, et al. Cognitive functioning in late-life bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.736

9. Steffens DC, Krishnan KR. Structural neuroimaging and mood disorders: Recent findings, implications for classification, and future directions. Biological Psychiatry. 1998;43(10):705-712.

10. Tamashiro JH, Zung S, Zanetti MV, et al. Increased rates of white matter hyperintensities in late-onset bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10(7):765-775.

11. Aziz R, Lorberg B, Tampi RR. Treatments for late-life bipolar disorder. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006;4(4):347-364.

12. Wefel JS, Kesler SR, Noll KR, et al. Clinical characteristics, pathophysiology, and management of noncentral nervous system cancer-related cognitive impairment in adults. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):123-138.

13. Amidi A, Hosseini SMH, Leemans A, et al. Changes in brain structural networks and cognitive functions in testicular cancer patients receiving cisplatin-based chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(12). doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx085.

14. Torrence C, Jackson J. New onset mania in late life: case report and literature review. J Mississippi Acad Sci. 2016;61(1):159.

15. Cassidy F, Carroll BJ. Vascular risk factors in late onset mania. Psychol Med. 2002;32(2):359-362.

16. Bellivier F, Golmard JL, Rietschel M, et al. Age at onset in bipolar I affective disorder: further evidence for three subgroups. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(5):999-1001.

17. Almeida OP, Fenner S. Bipolar disorder: similarities and differences between patients with illness onset before and after 65 years of age. Int Psychogeriatr. 2002;14(3):311-322.

18. Schürhoff F, Bellivier F, Jouvent R, et al. Early and late onset bipolar disorders: two different forms of manic-depressive illness? J Affect Disord. 2000;58(3):215-21.

Although the peak age of onset of bipolar disorder (BD) is between 20 and 40 years,1 some patients develop BD later in life. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force has classified the illness into 3 categories:

- early-onset bipolar disorder (EOBD), in which the first manic episode occurs before age 40

- late-onset bipolar disorder (LOBD), in which the initial manic/hypomanic episode occurs after age 50

- older-age bipolar disorder (OABD), in which the first manic/hypomanic episode occurs after age 60.2

OABD represents 25% of the population with BD.3 OABD differs from EOBD in its clinical presentation, biological factors, and psychiatric and somatic comorbidities.4 Studies suggest OABD warrants a more extensive workup to rule out organic causes because symptoms are often attributable to a variety of organic etiologies.

This article describes 3 cases of OABD, including treatments and outcomes. We discuss general treatment recommendations for patients with OABD as cited in the literature. Further research is needed to expand our ability to better care for this unique population.

CASE 1

Mr. D was a 66-year-old African American male with no psychiatric history. His medical history was significant for hypertension, poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease. One year ago, he was diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma, and underwent uncomplicated right trisegmentectomy, resection of extrahepatic biliary tree, and complete portal lymphadenectomy, with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy to 2 intrahepatic ducts. He presented to the emergency department (ED) with disorganized behavior for 3 weeks. During that time, Mr. D reported increased distractibility, irritability, hyper-religiosity, racing thoughts, decreased appetite, and decreased need for sleep. There was no pertinent family history.

On mental status examination, Mr. D was agitated, noncooperative, and guarded. His speech was loud and pressured. Mr. D was distractible, tangential, and goal-directed. His Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) score was 31, which is highly indicative of mania.5 Computed tomography (CT) scan of the head (Figure 1)

CASE 2

Mr. M was a 63-year-old African American male with no psychiatric history and a medical history significant for hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. He presented to the ED with behavioral changes for 2 weeks. During this time, he experienced decreased need for sleep, agitation, excessive spending, self-conversing, hypersexuality, and paranoia. His family history was significant for schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type.

A mental status examination revealed pressured speech, grandiose delusions, hyper-religiosity, flight of ideas, looseness of association, auditory hallucinations, and tangential thought processes. Mr. M’s initial YMRS score was 56. A CT scan of the head revealed no acute abnormality, but MRI of the brain (Figure 2) showed chronic microvascular ischemic change. Mr. M was diagnosed with bipolar I disorder and admitted. He was started on quetiapine extended release, which was titrated to 600 mg nightly. Divalproex sodium extended release was titrated to 1,500 mg nightly, with subsequent improvement. At discharge, his YMRS score was 15.

Continue to: CASE 3

CASE 3

Ms. F was a 69-year-old White female with no psychiatric history. Her medical history was significant for hypertension, osteoarthritis, and stage III-C ovarian adenocarcinoma with a debulking surgical procedure 5 years earlier. After that, she received adjuvant therapy with paclitaxel and carboplatin, which resulted in a 10-month disease-free interval. Subsequent progression led to cycles of doxorubicin liposomal and gemcitabine. She was in remission until 1 week earlier, when a CT scan of the abdomen/pelvis showed recurrence. She presented to the hospital after disrobing in the street due to hyper-religiosity and divine instruction. She endorsed elevated mood and increased energy despite sleeping only 2 hours daily. Her family psychiatric history was significant for her daughter’s suicide attempt.

A mental status examination revealed disorganized behavior and agitation. Her speech was loud and pressured. She described a “great” mood with congruent affect. Her thought process was circumstantial and illogical. She displayed flight of ideas, grandiose delusions, and paranoia. Ms. F’s initial YMRS score was 38. Vital signs were significant for an elevated blood pressure of 153/113 mm Hg. A CT scan of the head (Figure 3) showed age-related change with no acute findings. Ms. F was admitted with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder and prescribed olanzapine, 2.5 mg nightly. Due to continued manic symptoms, olanzapine was discontinued, and Ms. F was started on quetiapine, 300 mg nightly, with subsequent improvement. At discharge, her YMRS score was 10.

Differences between EOBD and OABD

BD has always been considered a multi-system illness; however, comorbidity is much more common in OABD than in EOBD. Comorbid conditions are 3 to 4 times more common in patients with OABD.2 Common comorbidities include metabolic syndrome, allergic rhinitis, arthritis, asthma, and cardiovascular disease.

Compared with younger individuals, older patients with BD score lower on the YMRS in the areas of increased activity-energy, language-thought disorder, and sexual interest.6 Psychotic symptoms are less common or less severe in OABD. Although symptom severity is lower, the prevalence of rapid cycling illness is 20% higher in patients with OABD.6 OABD is less commonly associated with a family history.7 This may suggest a difference from the popular genetic component typically found in patients with EOBD.

Cognitive impairment is more commonly found in OABD. Patients with OABD suffer from neuropsychological deficits even during euthymic phases.8 While these deficits may also be found in patients with EOBD, compared with younger patients, older adults are more susceptible to accelerated decline in cognition. OABD can first present within the context of cardiovascular or neuropsychological impairment. It has also been linked to a greater prevalence of white matter hyperintensities compared with EOBD.9,10

Continue to: Treatment is not specific to OABD

Treatment is not specific to OABD

No established treatment guidelines specifically address OABD. It has been treated similarly to EOBD, with antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, antidepressants, and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Although lithium is effective, special precautions should be taken when prescribing it to older adults because these patients may be more sensitive to adverse events.11 Drug–drug interactions may also be more likely due to concomitant use of medications for common medical issues such as hypertension.

Treatment with antipsychotics in older patients carries risks. Use of antipsychotics may result in higher rates of morbidity and mortality related to cardiovascular, metabolic, and infectious etiologies. Some literature recommends the use of antipsychotics for OABD; however, the potential benefits must outweigh the risks.6 Monotherapy followed by combination therapy has demonstrated effectiveness in OABD.11 Because symptoms of OABD are often less severe, it may be best to avoid maintenance antipsychotic therapy when possible. With a higher prevalence of depressed mood following manic episodes, use of antidepressant therapy is common in OABD.6 ECT should be considered for patients with treatment-refractory BD.11

Lessons from our case series

Our case series included 3 patients with OABD. These patients’ comorbid conditions included hypertension, hypercholesteremia, and diabetes mellitus. Two patients had a history of cancer, but there was no metastasis to the brain in either case. However, we considered the possibility of structural changes in the brain or cognitive impairment secondary to cancer or its treatment. A literature review confirmed that adult patients treated for noncentral nervous system cancer experienced cancer-related cognitive impairment (CRCI).12 New research suggests that CRCI could be related to altered neuronal integrity along with a disturbance of brain structure networks that process and integrate information.13

We used the YMRS to compare symptom severity and treatment response (Figure 4). Two patients were treated with atypical antipsychotics with a mood stabilizer, and the third patient was prescribed an antipsychotic only. We avoided lithium and carbamazepine as mood stabilizers due to their adverse effect profiles and potential for drug–drug interactions. Each patient responded well to treatment without adverse events.

Future studies are needed to clearly define the safest and most effective treatment guidelines in patients with OABD. We believe that OABD may require the development of a unique treatment algorithm due to the high likelihood of medical comorbidity and age-related variations in treatment response.

Continue to: Etiology of OABD may be different

Etiology of OABD may be different

OABD may be associated with manic presentations and vascular risk factors. MRI imaging that found more white matter hyperintensities and cerebrovascular lesions in patients with OABD compared with younger patients provides evidence of possible differing etiologies.14 Cassidy and Carroll15 found a higher incidence of smoking, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, and atrial fibrillation in patients in the older onset group. Bellivier et al16 proposed 3 subgroups of bipolar I disorder; the late-onset subgroup’s etiology was multifactorial. EOBD and OABD subgroups have similar gender ratios,17 first-episode descriptions, and alcohol use rates; however, OABD subgroups have more neurological comorbidity, lesser severe psychosis, and less genetic predisposition.

Although 25% of BD cases are late onset,3 there is still little consensus regarding subgroups and etiological causes. Therefore, additional research specifically focusing on vascular risks may provide much-needed information. Controlling and mitigating vascular risks in OABD may affect its development and course. Despite debated etiologies, the treatment of BD remains consistent, with anticonvulsants preferred over lithium in older individuals.

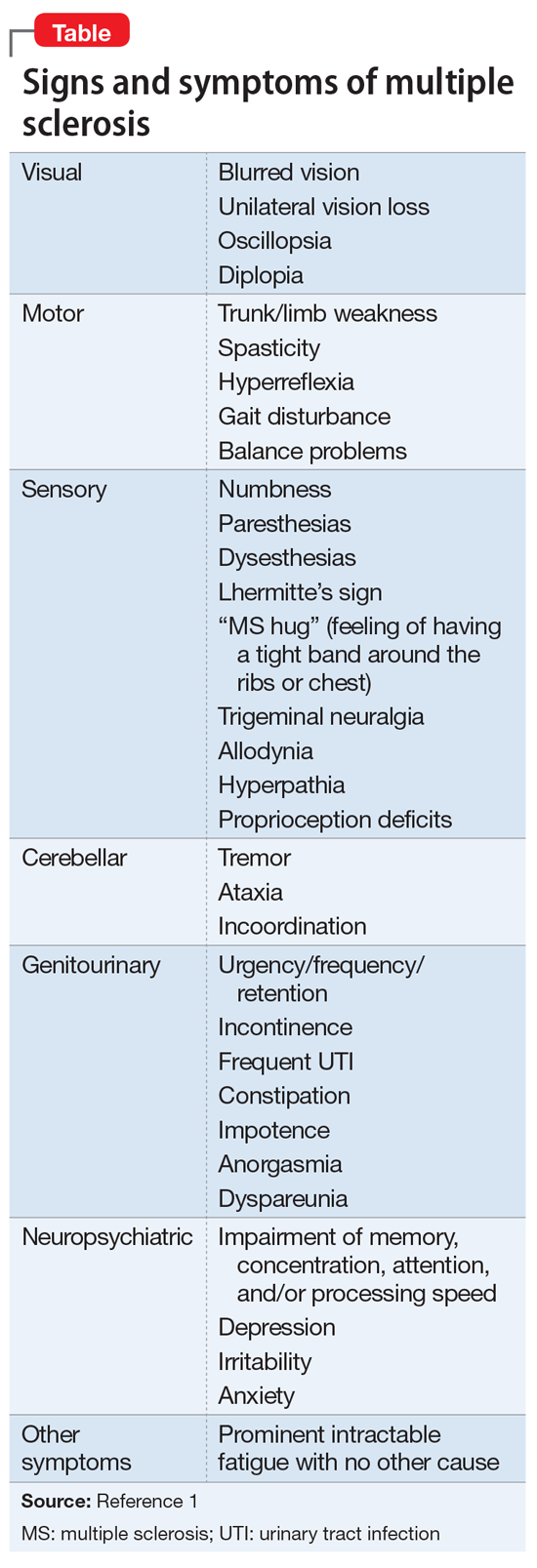

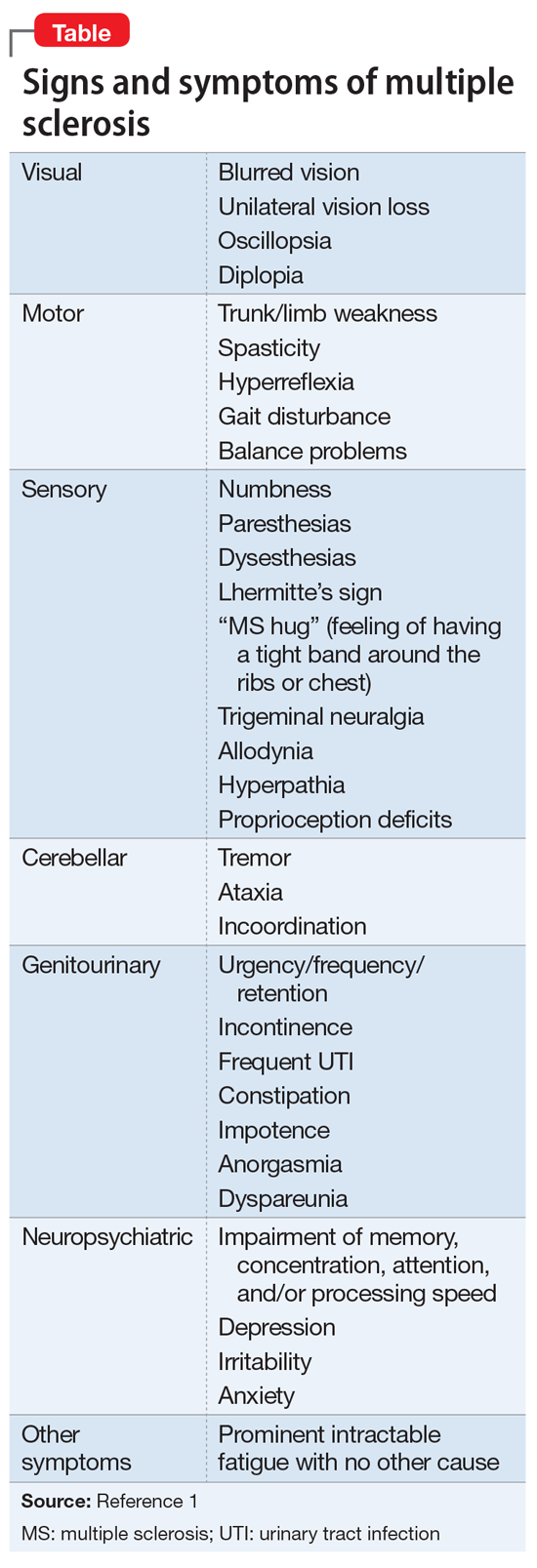

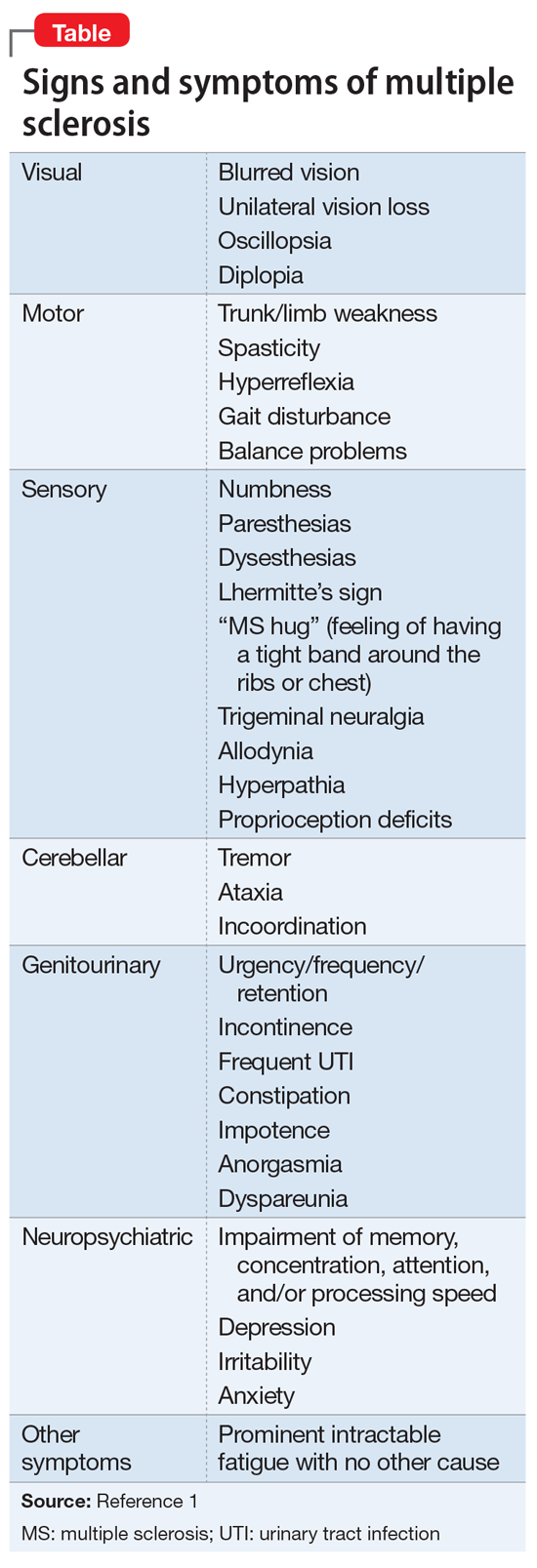

The Table summarizes clinical pearls about the features and treatment of OABD.

Bottom Line

Compared with younger patients with bipolar disorder (BD), those who develop BD later in life may be more likely to have rapid cycling, medical comorbidities, and cognitive impairment. Older patients with BD also may be more likely to experience adverse effects of the medications commonly used to treat BD, including antipsychotics, lithium, and carbamazepine.

Related Resources

- Carlino AR, Stinnett JL, Kim DR. New onset of bipolar disorder in late life. Psychosomatics. 2013;54(1):94-97.

- Sajatovic M, Kales HC, Mulsant BH. Prescribing antipsychotics in geriatric patients: Focus on schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(10):20-26,28.

Drug Brand Names

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, Tegretol

Carboplatin • Paraplatin

Divalproex sodium • Depakote

Doxorubicin liposome injection • Doxil

Gemcitabine injection • Gemzar

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paclitaxel injection • Abraxane

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Although the peak age of onset of bipolar disorder (BD) is between 20 and 40 years,1 some patients develop BD later in life. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force has classified the illness into 3 categories:

- early-onset bipolar disorder (EOBD), in which the first manic episode occurs before age 40

- late-onset bipolar disorder (LOBD), in which the initial manic/hypomanic episode occurs after age 50

- older-age bipolar disorder (OABD), in which the first manic/hypomanic episode occurs after age 60.2

OABD represents 25% of the population with BD.3 OABD differs from EOBD in its clinical presentation, biological factors, and psychiatric and somatic comorbidities.4 Studies suggest OABD warrants a more extensive workup to rule out organic causes because symptoms are often attributable to a variety of organic etiologies.

This article describes 3 cases of OABD, including treatments and outcomes. We discuss general treatment recommendations for patients with OABD as cited in the literature. Further research is needed to expand our ability to better care for this unique population.

CASE 1

Mr. D was a 66-year-old African American male with no psychiatric history. His medical history was significant for hypertension, poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease. One year ago, he was diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma, and underwent uncomplicated right trisegmentectomy, resection of extrahepatic biliary tree, and complete portal lymphadenectomy, with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy to 2 intrahepatic ducts. He presented to the emergency department (ED) with disorganized behavior for 3 weeks. During that time, Mr. D reported increased distractibility, irritability, hyper-religiosity, racing thoughts, decreased appetite, and decreased need for sleep. There was no pertinent family history.

On mental status examination, Mr. D was agitated, noncooperative, and guarded. His speech was loud and pressured. Mr. D was distractible, tangential, and goal-directed. His Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) score was 31, which is highly indicative of mania.5 Computed tomography (CT) scan of the head (Figure 1)

CASE 2

Mr. M was a 63-year-old African American male with no psychiatric history and a medical history significant for hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. He presented to the ED with behavioral changes for 2 weeks. During this time, he experienced decreased need for sleep, agitation, excessive spending, self-conversing, hypersexuality, and paranoia. His family history was significant for schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type.

A mental status examination revealed pressured speech, grandiose delusions, hyper-religiosity, flight of ideas, looseness of association, auditory hallucinations, and tangential thought processes. Mr. M’s initial YMRS score was 56. A CT scan of the head revealed no acute abnormality, but MRI of the brain (Figure 2) showed chronic microvascular ischemic change. Mr. M was diagnosed with bipolar I disorder and admitted. He was started on quetiapine extended release, which was titrated to 600 mg nightly. Divalproex sodium extended release was titrated to 1,500 mg nightly, with subsequent improvement. At discharge, his YMRS score was 15.

Continue to: CASE 3

CASE 3

Ms. F was a 69-year-old White female with no psychiatric history. Her medical history was significant for hypertension, osteoarthritis, and stage III-C ovarian adenocarcinoma with a debulking surgical procedure 5 years earlier. After that, she received adjuvant therapy with paclitaxel and carboplatin, which resulted in a 10-month disease-free interval. Subsequent progression led to cycles of doxorubicin liposomal and gemcitabine. She was in remission until 1 week earlier, when a CT scan of the abdomen/pelvis showed recurrence. She presented to the hospital after disrobing in the street due to hyper-religiosity and divine instruction. She endorsed elevated mood and increased energy despite sleeping only 2 hours daily. Her family psychiatric history was significant for her daughter’s suicide attempt.

A mental status examination revealed disorganized behavior and agitation. Her speech was loud and pressured. She described a “great” mood with congruent affect. Her thought process was circumstantial and illogical. She displayed flight of ideas, grandiose delusions, and paranoia. Ms. F’s initial YMRS score was 38. Vital signs were significant for an elevated blood pressure of 153/113 mm Hg. A CT scan of the head (Figure 3) showed age-related change with no acute findings. Ms. F was admitted with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder and prescribed olanzapine, 2.5 mg nightly. Due to continued manic symptoms, olanzapine was discontinued, and Ms. F was started on quetiapine, 300 mg nightly, with subsequent improvement. At discharge, her YMRS score was 10.

Differences between EOBD and OABD

BD has always been considered a multi-system illness; however, comorbidity is much more common in OABD than in EOBD. Comorbid conditions are 3 to 4 times more common in patients with OABD.2 Common comorbidities include metabolic syndrome, allergic rhinitis, arthritis, asthma, and cardiovascular disease.

Compared with younger individuals, older patients with BD score lower on the YMRS in the areas of increased activity-energy, language-thought disorder, and sexual interest.6 Psychotic symptoms are less common or less severe in OABD. Although symptom severity is lower, the prevalence of rapid cycling illness is 20% higher in patients with OABD.6 OABD is less commonly associated with a family history.7 This may suggest a difference from the popular genetic component typically found in patients with EOBD.

Cognitive impairment is more commonly found in OABD. Patients with OABD suffer from neuropsychological deficits even during euthymic phases.8 While these deficits may also be found in patients with EOBD, compared with younger patients, older adults are more susceptible to accelerated decline in cognition. OABD can first present within the context of cardiovascular or neuropsychological impairment. It has also been linked to a greater prevalence of white matter hyperintensities compared with EOBD.9,10

Continue to: Treatment is not specific to OABD

Treatment is not specific to OABD

No established treatment guidelines specifically address OABD. It has been treated similarly to EOBD, with antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, antidepressants, and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Although lithium is effective, special precautions should be taken when prescribing it to older adults because these patients may be more sensitive to adverse events.11 Drug–drug interactions may also be more likely due to concomitant use of medications for common medical issues such as hypertension.

Treatment with antipsychotics in older patients carries risks. Use of antipsychotics may result in higher rates of morbidity and mortality related to cardiovascular, metabolic, and infectious etiologies. Some literature recommends the use of antipsychotics for OABD; however, the potential benefits must outweigh the risks.6 Monotherapy followed by combination therapy has demonstrated effectiveness in OABD.11 Because symptoms of OABD are often less severe, it may be best to avoid maintenance antipsychotic therapy when possible. With a higher prevalence of depressed mood following manic episodes, use of antidepressant therapy is common in OABD.6 ECT should be considered for patients with treatment-refractory BD.11

Lessons from our case series

Our case series included 3 patients with OABD. These patients’ comorbid conditions included hypertension, hypercholesteremia, and diabetes mellitus. Two patients had a history of cancer, but there was no metastasis to the brain in either case. However, we considered the possibility of structural changes in the brain or cognitive impairment secondary to cancer or its treatment. A literature review confirmed that adult patients treated for noncentral nervous system cancer experienced cancer-related cognitive impairment (CRCI).12 New research suggests that CRCI could be related to altered neuronal integrity along with a disturbance of brain structure networks that process and integrate information.13

We used the YMRS to compare symptom severity and treatment response (Figure 4). Two patients were treated with atypical antipsychotics with a mood stabilizer, and the third patient was prescribed an antipsychotic only. We avoided lithium and carbamazepine as mood stabilizers due to their adverse effect profiles and potential for drug–drug interactions. Each patient responded well to treatment without adverse events.

Future studies are needed to clearly define the safest and most effective treatment guidelines in patients with OABD. We believe that OABD may require the development of a unique treatment algorithm due to the high likelihood of medical comorbidity and age-related variations in treatment response.

Continue to: Etiology of OABD may be different

Etiology of OABD may be different

OABD may be associated with manic presentations and vascular risk factors. MRI imaging that found more white matter hyperintensities and cerebrovascular lesions in patients with OABD compared with younger patients provides evidence of possible differing etiologies.14 Cassidy and Carroll15 found a higher incidence of smoking, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, and atrial fibrillation in patients in the older onset group. Bellivier et al16 proposed 3 subgroups of bipolar I disorder; the late-onset subgroup’s etiology was multifactorial. EOBD and OABD subgroups have similar gender ratios,17 first-episode descriptions, and alcohol use rates; however, OABD subgroups have more neurological comorbidity, lesser severe psychosis, and less genetic predisposition.

Although 25% of BD cases are late onset,3 there is still little consensus regarding subgroups and etiological causes. Therefore, additional research specifically focusing on vascular risks may provide much-needed information. Controlling and mitigating vascular risks in OABD may affect its development and course. Despite debated etiologies, the treatment of BD remains consistent, with anticonvulsants preferred over lithium in older individuals.

The Table summarizes clinical pearls about the features and treatment of OABD.

Bottom Line

Compared with younger patients with bipolar disorder (BD), those who develop BD later in life may be more likely to have rapid cycling, medical comorbidities, and cognitive impairment. Older patients with BD also may be more likely to experience adverse effects of the medications commonly used to treat BD, including antipsychotics, lithium, and carbamazepine.

Related Resources

- Carlino AR, Stinnett JL, Kim DR. New onset of bipolar disorder in late life. Psychosomatics. 2013;54(1):94-97.

- Sajatovic M, Kales HC, Mulsant BH. Prescribing antipsychotics in geriatric patients: Focus on schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(10):20-26,28.

Drug Brand Names

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, Tegretol

Carboplatin • Paraplatin

Divalproex sodium • Depakote

Doxorubicin liposome injection • Doxil

Gemcitabine injection • Gemzar

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paclitaxel injection • Abraxane

Quetiapine • Seroquel

1. Prabhakar D, Balon R. Late-onset bipolar disorder: a case for careful appraisal. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2010;7(1):34-37.

2. Sajatovic M, Strejilevich SA, Gildengers AG, et al. A report on older-age bipolar disorder from the International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17(7):689-704.

3. Arciniegas DB. New-onset bipolar disorder in late life: a case of mistaken identity. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(2):198-203.

4. Chou P-H, Tseng W-J, Chen L-M, et al. Late onset bipolar disorder: a case report and review of the literature. Journal of Clinical Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2015;6(1):27-29.

5. Lukasiewicz M, Gerard S, Besnard A, et al; Emblem Study Group. Young Mania Rating Scale: how to interpret the numbers? Determination of a severity threshold and of the minimal clinically significant difference in the EMBLEM cohort. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2013;22(1):46-58.

6. Oostervink F, Boomsma MM, Nolen WA; EMBLEM Advisory Board. Bipolar disorder in the elderly; different effects of age and of age of onset. J Affect Disord. 2009;116(3):176-183.

7. Depp CA, Jeste D V. Bipolar disorder in older adults: A critical review. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6(5):343-367.8.

8. Gildengers AG, Butters MA, et al. Cognitive functioning in late-life bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.736

9. Steffens DC, Krishnan KR. Structural neuroimaging and mood disorders: Recent findings, implications for classification, and future directions. Biological Psychiatry. 1998;43(10):705-712.

10. Tamashiro JH, Zung S, Zanetti MV, et al. Increased rates of white matter hyperintensities in late-onset bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10(7):765-775.

11. Aziz R, Lorberg B, Tampi RR. Treatments for late-life bipolar disorder. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006;4(4):347-364.

12. Wefel JS, Kesler SR, Noll KR, et al. Clinical characteristics, pathophysiology, and management of noncentral nervous system cancer-related cognitive impairment in adults. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):123-138.

13. Amidi A, Hosseini SMH, Leemans A, et al. Changes in brain structural networks and cognitive functions in testicular cancer patients receiving cisplatin-based chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(12). doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx085.

14. Torrence C, Jackson J. New onset mania in late life: case report and literature review. J Mississippi Acad Sci. 2016;61(1):159.

15. Cassidy F, Carroll BJ. Vascular risk factors in late onset mania. Psychol Med. 2002;32(2):359-362.

16. Bellivier F, Golmard JL, Rietschel M, et al. Age at onset in bipolar I affective disorder: further evidence for three subgroups. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(5):999-1001.

17. Almeida OP, Fenner S. Bipolar disorder: similarities and differences between patients with illness onset before and after 65 years of age. Int Psychogeriatr. 2002;14(3):311-322.

18. Schürhoff F, Bellivier F, Jouvent R, et al. Early and late onset bipolar disorders: two different forms of manic-depressive illness? J Affect Disord. 2000;58(3):215-21.

1. Prabhakar D, Balon R. Late-onset bipolar disorder: a case for careful appraisal. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2010;7(1):34-37.

2. Sajatovic M, Strejilevich SA, Gildengers AG, et al. A report on older-age bipolar disorder from the International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17(7):689-704.

3. Arciniegas DB. New-onset bipolar disorder in late life: a case of mistaken identity. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(2):198-203.

4. Chou P-H, Tseng W-J, Chen L-M, et al. Late onset bipolar disorder: a case report and review of the literature. Journal of Clinical Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2015;6(1):27-29.

5. Lukasiewicz M, Gerard S, Besnard A, et al; Emblem Study Group. Young Mania Rating Scale: how to interpret the numbers? Determination of a severity threshold and of the minimal clinically significant difference in the EMBLEM cohort. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2013;22(1):46-58.

6. Oostervink F, Boomsma MM, Nolen WA; EMBLEM Advisory Board. Bipolar disorder in the elderly; different effects of age and of age of onset. J Affect Disord. 2009;116(3):176-183.

7. Depp CA, Jeste D V. Bipolar disorder in older adults: A critical review. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6(5):343-367.8.

8. Gildengers AG, Butters MA, et al. Cognitive functioning in late-life bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.736

9. Steffens DC, Krishnan KR. Structural neuroimaging and mood disorders: Recent findings, implications for classification, and future directions. Biological Psychiatry. 1998;43(10):705-712.

10. Tamashiro JH, Zung S, Zanetti MV, et al. Increased rates of white matter hyperintensities in late-onset bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10(7):765-775.

11. Aziz R, Lorberg B, Tampi RR. Treatments for late-life bipolar disorder. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006;4(4):347-364.

12. Wefel JS, Kesler SR, Noll KR, et al. Clinical characteristics, pathophysiology, and management of noncentral nervous system cancer-related cognitive impairment in adults. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):123-138.

13. Amidi A, Hosseini SMH, Leemans A, et al. Changes in brain structural networks and cognitive functions in testicular cancer patients receiving cisplatin-based chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(12). doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx085.

14. Torrence C, Jackson J. New onset mania in late life: case report and literature review. J Mississippi Acad Sci. 2016;61(1):159.

15. Cassidy F, Carroll BJ. Vascular risk factors in late onset mania. Psychol Med. 2002;32(2):359-362.

16. Bellivier F, Golmard JL, Rietschel M, et al. Age at onset in bipolar I affective disorder: further evidence for three subgroups. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(5):999-1001.

17. Almeida OP, Fenner S. Bipolar disorder: similarities and differences between patients with illness onset before and after 65 years of age. Int Psychogeriatr. 2002;14(3):311-322.

18. Schürhoff F, Bellivier F, Jouvent R, et al. Early and late onset bipolar disorders: two different forms of manic-depressive illness? J Affect Disord. 2000;58(3):215-21.

Bipolar patients’ ability to consent can be measured with MacCAT-CR

, according to Christina C. Klein and her associates.

A total of 50 patients who were enrolled in a clinical trial of approved, standard treatments for bipolar disease were included in the consent study. The MacCAT-CR was administered after patients had given consent to be included in the trial, but before the trial had started. Four patients lacked the ability to provide consent for the trial after receiving the MacCAT-CR. After these patients were reeducated and went through the consent process a second time, three were enrolled and one declined enrollment.

Patients with higher Schedule for Assessment of Positive Symptoms scores were more likely to have worse MacCAT-CR Understanding and Appreciation subscale scores; lower Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and higher Clinical Global Impression–Severity scores were associated with worse Reasoning and Understanding subscale scores.

Comorbid ADHD, sex, IQ scores, and age at onset of bipolar disorder were not correlated with any subscale scores. In addition, a history of substance use disorder was associated with higher Appreciation and Reasoning subscale scores.

“The current study provides important information for clinicians and researchers to consider when obtaining informed consent from an individual with bipolar disorder. The MacCAT-CR may serve to identify patients, specifically those with higher psychotic symptoms or global illness severity, as needing additional education regarding informed consent,” the investigators concluded.

Three study coauthors reported conflicts of interest with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Klein CC et al. J Affect Disord. 2018 Aug 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.08.049.

, according to Christina C. Klein and her associates.

A total of 50 patients who were enrolled in a clinical trial of approved, standard treatments for bipolar disease were included in the consent study. The MacCAT-CR was administered after patients had given consent to be included in the trial, but before the trial had started. Four patients lacked the ability to provide consent for the trial after receiving the MacCAT-CR. After these patients were reeducated and went through the consent process a second time, three were enrolled and one declined enrollment.

Patients with higher Schedule for Assessment of Positive Symptoms scores were more likely to have worse MacCAT-CR Understanding and Appreciation subscale scores; lower Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and higher Clinical Global Impression–Severity scores were associated with worse Reasoning and Understanding subscale scores.

Comorbid ADHD, sex, IQ scores, and age at onset of bipolar disorder were not correlated with any subscale scores. In addition, a history of substance use disorder was associated with higher Appreciation and Reasoning subscale scores.

“The current study provides important information for clinicians and researchers to consider when obtaining informed consent from an individual with bipolar disorder. The MacCAT-CR may serve to identify patients, specifically those with higher psychotic symptoms or global illness severity, as needing additional education regarding informed consent,” the investigators concluded.

Three study coauthors reported conflicts of interest with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Klein CC et al. J Affect Disord. 2018 Aug 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.08.049.

, according to Christina C. Klein and her associates.

A total of 50 patients who were enrolled in a clinical trial of approved, standard treatments for bipolar disease were included in the consent study. The MacCAT-CR was administered after patients had given consent to be included in the trial, but before the trial had started. Four patients lacked the ability to provide consent for the trial after receiving the MacCAT-CR. After these patients were reeducated and went through the consent process a second time, three were enrolled and one declined enrollment.

Patients with higher Schedule for Assessment of Positive Symptoms scores were more likely to have worse MacCAT-CR Understanding and Appreciation subscale scores; lower Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and higher Clinical Global Impression–Severity scores were associated with worse Reasoning and Understanding subscale scores.

Comorbid ADHD, sex, IQ scores, and age at onset of bipolar disorder were not correlated with any subscale scores. In addition, a history of substance use disorder was associated with higher Appreciation and Reasoning subscale scores.

“The current study provides important information for clinicians and researchers to consider when obtaining informed consent from an individual with bipolar disorder. The MacCAT-CR may serve to identify patients, specifically those with higher psychotic symptoms or global illness severity, as needing additional education regarding informed consent,” the investigators concluded.

Three study coauthors reported conflicts of interest with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Klein CC et al. J Affect Disord. 2018 Aug 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.08.049.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF AFFECTIVE DISORDERS

Early maladaptive schemas increase suicide risk, ideation in bipolar

The entitlement, social isolation, and defectiveness early maladaptive schemas (EMSs) were associated with increased suicide risk and ideation in patients with bipolar disorder, according to Vahid Khosravani of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, and his associates.

“These findings were in line with previous studies (J Nerv Ment Dis. 2016 Mar. 204[3]:236-9) showing higher scores of social isolation and entitlement in [bipolar disorder] patients with suicide attempts than those without such attempts,” Mr. Khosravani and his associates wrote in Psychiatry Research.

For the study, 100 inpatients with bipolar disorder completed the Young Schema Questionnaire–Short Form (YSQ-SF), the Bipolar Depression Rating Scale (BDRS), the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS), and the Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSSI). Of that group, 59% had attempted suicide and 59% had a BSSI score of 6 or higher, indicating high suicidal risk, reported Mr. Khosravani and his associates.

; they also had higher levels of depressive and hypomanic/manic symptoms. Current suicide ideation was associated with higher entitlement and defectiveness EMS scores, as well as with increased hypomanic/manic symptoms.

“The findings suggest that manic symptoms as well as specific EMSs including social isolation, entitlement, and defectiveness emerge as potentially implicated in suicidality in BD patients,” the investigators noted. “Therefore, providing social support in the economic, social, political, cultural, and educational spheres may be a factor in preventing suicide.”

Mr. Khosravani and his associates said their study received no funding from public, commercial, or nonprofit agencies. The investigators declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Khosravani V et al. Psychiatry Res. 2019 Jan. (271):351-9.

The entitlement, social isolation, and defectiveness early maladaptive schemas (EMSs) were associated with increased suicide risk and ideation in patients with bipolar disorder, according to Vahid Khosravani of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, and his associates.

“These findings were in line with previous studies (J Nerv Ment Dis. 2016 Mar. 204[3]:236-9) showing higher scores of social isolation and entitlement in [bipolar disorder] patients with suicide attempts than those without such attempts,” Mr. Khosravani and his associates wrote in Psychiatry Research.

For the study, 100 inpatients with bipolar disorder completed the Young Schema Questionnaire–Short Form (YSQ-SF), the Bipolar Depression Rating Scale (BDRS), the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS), and the Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSSI). Of that group, 59% had attempted suicide and 59% had a BSSI score of 6 or higher, indicating high suicidal risk, reported Mr. Khosravani and his associates.

; they also had higher levels of depressive and hypomanic/manic symptoms. Current suicide ideation was associated with higher entitlement and defectiveness EMS scores, as well as with increased hypomanic/manic symptoms.

“The findings suggest that manic symptoms as well as specific EMSs including social isolation, entitlement, and defectiveness emerge as potentially implicated in suicidality in BD patients,” the investigators noted. “Therefore, providing social support in the economic, social, political, cultural, and educational spheres may be a factor in preventing suicide.”

Mr. Khosravani and his associates said their study received no funding from public, commercial, or nonprofit agencies. The investigators declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Khosravani V et al. Psychiatry Res. 2019 Jan. (271):351-9.

The entitlement, social isolation, and defectiveness early maladaptive schemas (EMSs) were associated with increased suicide risk and ideation in patients with bipolar disorder, according to Vahid Khosravani of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, and his associates.

“These findings were in line with previous studies (J Nerv Ment Dis. 2016 Mar. 204[3]:236-9) showing higher scores of social isolation and entitlement in [bipolar disorder] patients with suicide attempts than those without such attempts,” Mr. Khosravani and his associates wrote in Psychiatry Research.

For the study, 100 inpatients with bipolar disorder completed the Young Schema Questionnaire–Short Form (YSQ-SF), the Bipolar Depression Rating Scale (BDRS), the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS), and the Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSSI). Of that group, 59% had attempted suicide and 59% had a BSSI score of 6 or higher, indicating high suicidal risk, reported Mr. Khosravani and his associates.

; they also had higher levels of depressive and hypomanic/manic symptoms. Current suicide ideation was associated with higher entitlement and defectiveness EMS scores, as well as with increased hypomanic/manic symptoms.

“The findings suggest that manic symptoms as well as specific EMSs including social isolation, entitlement, and defectiveness emerge as potentially implicated in suicidality in BD patients,” the investigators noted. “Therefore, providing social support in the economic, social, political, cultural, and educational spheres may be a factor in preventing suicide.”

Mr. Khosravani and his associates said their study received no funding from public, commercial, or nonprofit agencies. The investigators declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Khosravani V et al. Psychiatry Res. 2019 Jan. (271):351-9.

FROM PSYCHIATRY RESEARCH

ADHD more likely, causes worse outcomes in patients with BD

ADHD is significantly more common and is associated with worse outcomes in patients with bipolar disorder, according to Ross J. Baldessarini, MD, of McLean Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his associates.

In a study of 703 patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder (BD) type I or II who were evaluated, treated, and followed at the Lucio Bini Mood Disorder Centers in Rome and Cagliari, Italy, 173 patients had co-occurring lifetime ADHD. Co-occurring conditions were more likely in men and in those with BD-I. The lifetime ADHD prevalence rate of 24.6% in patients with bipolar disorder is significantly higher than the incidence in the general population, the investigators wrote in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

Patients with co-occurring ADHD and BD were more likely to have performed worse in school, have higher Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale scores, be unemployed, have lower socioeconomic status, be married, have separated, have substance abuse, have attempted suicide, and have hypomania, compared with patients with only BD. However, they were less likely to have an anxiety disorder or a family history of mood disorders.

“The association of ADHD with a less successful and stable educational history, more unemployment, lack of or failed marriages, and greater risk of suicide attempts and substance abuse indicates unfavorable effects of having ADHD with BD. Such effects may arise by the impact of ADHD early during development,” the investigators concluded.

The study was partly supported by a research award from the Aretaeus Association of Rome and grants from the Bruce J. Anderson Foundation and the McLean Private Donors Research Fund. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Baldessarini RJ et al. J Affect Disord. 2018 Sep 17. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.09.038.

ADHD is significantly more common and is associated with worse outcomes in patients with bipolar disorder, according to Ross J. Baldessarini, MD, of McLean Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his associates.

In a study of 703 patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder (BD) type I or II who were evaluated, treated, and followed at the Lucio Bini Mood Disorder Centers in Rome and Cagliari, Italy, 173 patients had co-occurring lifetime ADHD. Co-occurring conditions were more likely in men and in those with BD-I. The lifetime ADHD prevalence rate of 24.6% in patients with bipolar disorder is significantly higher than the incidence in the general population, the investigators wrote in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

Patients with co-occurring ADHD and BD were more likely to have performed worse in school, have higher Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale scores, be unemployed, have lower socioeconomic status, be married, have separated, have substance abuse, have attempted suicide, and have hypomania, compared with patients with only BD. However, they were less likely to have an anxiety disorder or a family history of mood disorders.

“The association of ADHD with a less successful and stable educational history, more unemployment, lack of or failed marriages, and greater risk of suicide attempts and substance abuse indicates unfavorable effects of having ADHD with BD. Such effects may arise by the impact of ADHD early during development,” the investigators concluded.

The study was partly supported by a research award from the Aretaeus Association of Rome and grants from the Bruce J. Anderson Foundation and the McLean Private Donors Research Fund. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Baldessarini RJ et al. J Affect Disord. 2018 Sep 17. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.09.038.

ADHD is significantly more common and is associated with worse outcomes in patients with bipolar disorder, according to Ross J. Baldessarini, MD, of McLean Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his associates.

In a study of 703 patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder (BD) type I or II who were evaluated, treated, and followed at the Lucio Bini Mood Disorder Centers in Rome and Cagliari, Italy, 173 patients had co-occurring lifetime ADHD. Co-occurring conditions were more likely in men and in those with BD-I. The lifetime ADHD prevalence rate of 24.6% in patients with bipolar disorder is significantly higher than the incidence in the general population, the investigators wrote in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

Patients with co-occurring ADHD and BD were more likely to have performed worse in school, have higher Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale scores, be unemployed, have lower socioeconomic status, be married, have separated, have substance abuse, have attempted suicide, and have hypomania, compared with patients with only BD. However, they were less likely to have an anxiety disorder or a family history of mood disorders.

“The association of ADHD with a less successful and stable educational history, more unemployment, lack of or failed marriages, and greater risk of suicide attempts and substance abuse indicates unfavorable effects of having ADHD with BD. Such effects may arise by the impact of ADHD early during development,” the investigators concluded.

The study was partly supported by a research award from the Aretaeus Association of Rome and grants from the Bruce J. Anderson Foundation and the McLean Private Donors Research Fund. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Baldessarini RJ et al. J Affect Disord. 2018 Sep 17. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.09.038.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF AFFECTIVE DISORDERS

Best of Psychopharmacology: Stimulants, ketamine, benzodiazapines

In this episode we go back to the summer for two master classes on ketamine and stimulants, respectively and we drop in on two conversations between Lorenzo Norris, MD on anxiety and comorbid ADHD as well as a conversation on benzodiazapines. The Psychcast will be back with new content in 2019.

Amazon

Apple

Google

Spotify

In this episode we go back to the summer for two master classes on ketamine and stimulants, respectively and we drop in on two conversations between Lorenzo Norris, MD on anxiety and comorbid ADHD as well as a conversation on benzodiazapines. The Psychcast will be back with new content in 2019.

Amazon

Apple

Google

Spotify

In this episode we go back to the summer for two master classes on ketamine and stimulants, respectively and we drop in on two conversations between Lorenzo Norris, MD on anxiety and comorbid ADHD as well as a conversation on benzodiazapines. The Psychcast will be back with new content in 2019.

Amazon

Apple

Google

Spotify

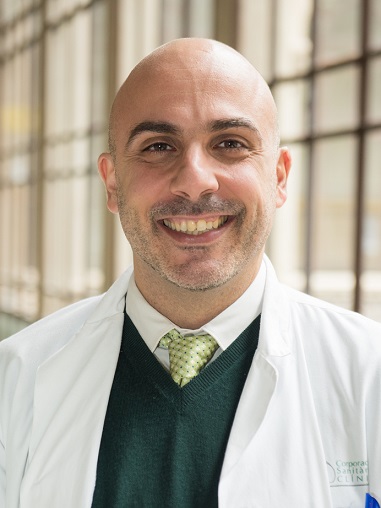

CPN welcomes Andrea Murru, MD, PhD, to CPN board

Clinical Psychiatry News is pleased to announce that Andrea Murru, MD, PhD, has joined the Editorial Advisory Board.

Dr. Murru is senior clinician in the bipolar disorder and sleep disorder units of the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona in Spain, and is a postdoctoral researcher of the Spanish Network of Research in Mental Health, which is led by Eduard Vieta, MD, PhD.

In addition, His research focuses on using, long-term treatments, and implementing clinical guidelines in daily practice. He also researches tolerability in patients with bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and sleep-related disorders and biomarkers.

He earned his medical degree from the University of Cagliari (Italy).

Clinical Psychiatry News is pleased to announce that Andrea Murru, MD, PhD, has joined the Editorial Advisory Board.

Dr. Murru is senior clinician in the bipolar disorder and sleep disorder units of the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona in Spain, and is a postdoctoral researcher of the Spanish Network of Research in Mental Health, which is led by Eduard Vieta, MD, PhD.

In addition, His research focuses on using, long-term treatments, and implementing clinical guidelines in daily practice. He also researches tolerability in patients with bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and sleep-related disorders and biomarkers.

He earned his medical degree from the University of Cagliari (Italy).

Clinical Psychiatry News is pleased to announce that Andrea Murru, MD, PhD, has joined the Editorial Advisory Board.

Dr. Murru is senior clinician in the bipolar disorder and sleep disorder units of the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona in Spain, and is a postdoctoral researcher of the Spanish Network of Research in Mental Health, which is led by Eduard Vieta, MD, PhD.

In addition, His research focuses on using, long-term treatments, and implementing clinical guidelines in daily practice. He also researches tolerability in patients with bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and sleep-related disorders and biomarkers.

He earned his medical degree from the University of Cagliari (Italy).

A mood disorder complicated by multiple sclerosis

CASE Depression, or something else?

Ms. A, age 56, presents to the emergency department (ED) with depressed mood, poor sleep, anhedonia, irritability, agitation, and recent self-injurious behavior; she had superficially cut her wrists. She also has a longstanding history of multiple sclerosis (MS), depression, and anxiety. She is admitted voluntarily to an inpatient psychiatric unit.

According to medical records, at age 32, Ms. A was diagnosed with relapsing-remitting MS, which initially presented with facial numbness, and later with optic neuritis with transient loss of vision. As her disease progressed to the secondary progressive type, she experienced spasticity and vertigo. In the past few years, she also had experienced cognitive difficulties, particularly with memory and focus.

Ms. A has a history of recurrent depressive symptoms that began at an unspecified time after being diagnosed with MS. In the past few years, she had greatly increased her alcohol use in response to multiple psychosocial stressors and as an attempt to self-medicate MS-related pain. Several years ago, Ms. A had been admitted to a rehabilitation facility to address her alcohol use.

In the past, Ms. A’s depressive symptoms had been treated with various antidepressants, including fluoxetine (unspecified dose), which for a time was effective. The most recently prescribed antidepressant was duloxetine, 60 mg/d, which was discontinued because Ms. A felt it activated her mood lability. A few years before this current hospitalization, Ms. A had been started on a trial of dextromethorphan/quinidine (20 mg/10 mg, twice daily), which was discontinued due to concomitant use of an unspecified serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) and subsequent precipitation of serotonin syndrome.

At the time of this current admission to the psychiatric unit, Ms. A is being treated for MS with rituximab (10 mg/mL IV, every 6 months). Additionally, just before her admission, she was taking alprazolam (.25 mg, 3 times per day) for anxiety. She denies experiencing any spasticity or vision impairment.

[polldaddy:10175070]

The authors’ observations

We initially considered a diagnosis of MDD due to Ms. A’s past history of depressive episodes, her recent increase in tearfulness and anhedonia, and her self-injurious behaviors. However, diagnosis of a mood disorder was complicated by her complex history of longstanding MS and other psychosocial factors.

Continue to: Several factors contribute to the neuropsychiatric course of patients with MS...

Several factors contribute to the neuropsychiatric course of patients with MS, including the impact of the patient accepting a chronic and incurable diagnosis, the toll of progressive neurologic/physical disability and subsequent decline in functioning, and the availability of a support system.2 As opposed to disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, where disease progression is relatively more predictable, the culture of MS involves the obscurity of symptom fluctuation, both from the patient’s and/or clinician’s viewpoint. Psychiatric and neurologic symptoms may be difficult to predict, leading to speculation and projection as to the progression of the disease. The diagnosis of psychiatric conditions, such as depression, can be complicated by the fact that MS and psychiatric disorders share presenting symptoms; for example, disturbances in sleep and concentration may be seen in both conditions.

While studies have examined the neurobiology of MS lesions and their effects on mood symptoms, there has been no clear consensus of specific lesion distributions, although lesions in the superior frontal lobe and right temporal lobe regions have been identified in depressed MS patients.8 Lesions in the left frontal lobe may also have some contribution; studies have shown hyperintense lesion load in this area, which was found to be an independent predictor of MDD in MS.9 This, in turn, coincides with the association of left frontal cortex involvement in modulating affective depression, evidenced by studies that have associated depression severity with left frontal lobe damage in post-stroke patients10 as well as the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation of the left prefrontal cortex for treatment-resistant MDD.11 Lesions along the orbitofrontal prefrontal cortex have similarly been connected to mood lability and impulsivity, which are characteristics of bipolar disorder.8 Within the general population, bipolar disorder is associated with areas of hyperintensity on MRI, particularly in the frontal and parietal white matter, which may provide clues as to the role of MS demyelinating lesions in similar locations, although research concerning the relationship between MS and bipolar disorder remains limited.12

EVALUATION No exacerbation of MS

Upon admission, Ms. A’s lability of affect is apparent as she quickly switches from being tearful to bright depending on the topic of discussion. She smiles when talking about the hobbies she enjoys and becomes tearful when speaking of personal problems within her family. She denies suicidal ideation/intent, shows no evidence of psychosis, and denies any history of bipolar disorder or recollection of hypomanic/manic symptoms. Overall, she exhibits low energy and difficulty sleeping, and reiterates her various psychosocial stressors, including her family history of depression and ongoing marital conflicts. Ms. A denies experiencing any acute exacerbations of clinical neurologic features of MS immediately before or during her admission. Laboratory values are normal, except for an elevated thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) value of 11.136 uIU/mL, which is expected given her history of hypothyroidism. Results of the most recent brain MRI scans for Ms. A are pending.

The authors’ observations

Although we considered a diagnosis of bipolar disorder–mixed subtype, this was less likely to be the diagnosis considering her lack of any frank manic/hypomanic symptoms or history of such symptoms. Additionally, while we also considered a diagnosis of pseudobulbar affect due to her current mood swings and past trial of dextromethorphan/quinidine, this diagnosis was also less likely because Ms. A’s affect was not characterized by uncontrollable outbursts of emotion but was congruent with her experiences and surroundings. For example, Ms. A smiled when talking about her hobbies and became tearful when speaking of conflicts within her family.

Given Ms. A’s mood dysregulation and lability and her history of depressive episodes that began to manifest after her diagnosis of MS was established, and after ruling out other etiologic psychiatric disorders, a diagnosis of mood disorder secondary to MS was made.

[polldaddy:10175136]

Continue to: TREATMENT Mood stabilization

TREATMENT Mood stabilization

We start Ms. A on divalproex sodium, 250 mg 2 times a day, which is eventually titrated to 250 mg every morning with an additional daily 750 mg (total daily dose of 1,000 mg) for mood stabilization. Additionally, quetiapine, 50 mg nightly, is added and eventually titrated to 300 mg to augment mood stabilization and to aid sleep. Before being admitted, Ms. A had been prescribed

The authors’ observations

Definitive treatments for psychiatric conditions in patients with MS have been lacking, and current recommendations are based on regimens used to treat general psychiatric populations. For example, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are frequently considered for treatment of MDD in patients with MS, whereas SNRIs are considered for patients with concomitant neuropathic pain.13 Similarly,

OUTCOME Improved mood, energy

After 2 weeks of inpatient treatment, Ms. A shows improvement in mood lability and energy levels, and she is able to tolerate titration of divalproex sodium and quetiapine to therapeutic levels. She is referred to an outpatient psychiatrist after discharge, as well as a follow-up appointment with her neurologist. On discharge, Ms. A expresses a commitment to treatment and hope for the future.

1. National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Signs and symptoms consistent with demyelinating disease (for professionals). https://www.nationalmssociety.org/For-Professionals/Clinical-Care/Diagnosing-MS/Signs-and-Symptoms-Consistent-with-Demyelinating-D. Accessed October 29, 2018.

2. Politte LC, Huffman JC, Stern TA. Neuropsychiatric manifestations of multiple sclerosis. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;10(4):318-324.

3. Siegert RJ, Abernethy D. Depression in multiple sclerosis: a review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(4):469-475.

4. Scalfari A, Knappertz V, Cutter G, et al. Mortality in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2013;81(2):184-192.

5. Ghaffar O, Feinstein A. The neuropsychiatry of multiple sclerosis: a review of recent developments. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20(3):278-285.

6. Duncan A, Malcolm-Smith S, Ameen O, et al. The incidence of euphoria in multiple sclerosis: artefact of measure. Mult Scler Int. 2016;2016:1-8.

7. Paparrigopoulos T, Ferentinos P, Kouzoupis A, et al. The neuropsychiatry of multiple sclerosis: focus on disorders of mood, affect and behaviour. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010;22(1):14-21.

8. Bakshi R, Czarnecki D, Shaikh ZA, et al. Brain MRI lesions and atrophy are related to depression in multiple sclerosis. Neuroreport. 2000;11(6):1153-1158.

9. Feinstein A, Roy P, Lobaugh N, et al. Structural brain abnormalities in multiple sclerosis patients with major depression. Neurology. 2004;62(4):586-590.

10. Hama S, Yamashita H, Shigenobu M, et al. Post-stroke affective or apathetic depression and lesion location: left frontal lobe and bilateral basal ganglia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;257(3):149-152.

11. Carpenter LL, Janicak PG, Aaronson ST, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) for major depression: a multisite, naturalistic, observational study of acute treatment outcomes in clinical practice. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(7):587-596.

12. Beyer JL, Young R, Kuchibhatla M, et al. Hyperintense MRI lesions in bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis and review. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;21(4):394-409.

13. Feinstein A. Neuropsychiatric syndromes associated with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2007;254(S2):1173-1176.

14. Thomas PW, Thomas S, Hillier C, et al. Psychological interventions for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD004431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd004431.pub2.

CASE Depression, or something else?

Ms. A, age 56, presents to the emergency department (ED) with depressed mood, poor sleep, anhedonia, irritability, agitation, and recent self-injurious behavior; she had superficially cut her wrists. She also has a longstanding history of multiple sclerosis (MS), depression, and anxiety. She is admitted voluntarily to an inpatient psychiatric unit.

According to medical records, at age 32, Ms. A was diagnosed with relapsing-remitting MS, which initially presented with facial numbness, and later with optic neuritis with transient loss of vision. As her disease progressed to the secondary progressive type, she experienced spasticity and vertigo. In the past few years, she also had experienced cognitive difficulties, particularly with memory and focus.

Ms. A has a history of recurrent depressive symptoms that began at an unspecified time after being diagnosed with MS. In the past few years, she had greatly increased her alcohol use in response to multiple psychosocial stressors and as an attempt to self-medicate MS-related pain. Several years ago, Ms. A had been admitted to a rehabilitation facility to address her alcohol use.

In the past, Ms. A’s depressive symptoms had been treated with various antidepressants, including fluoxetine (unspecified dose), which for a time was effective. The most recently prescribed antidepressant was duloxetine, 60 mg/d, which was discontinued because Ms. A felt it activated her mood lability. A few years before this current hospitalization, Ms. A had been started on a trial of dextromethorphan/quinidine (20 mg/10 mg, twice daily), which was discontinued due to concomitant use of an unspecified serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) and subsequent precipitation of serotonin syndrome.

At the time of this current admission to the psychiatric unit, Ms. A is being treated for MS with rituximab (10 mg/mL IV, every 6 months). Additionally, just before her admission, she was taking alprazolam (.25 mg, 3 times per day) for anxiety. She denies experiencing any spasticity or vision impairment.

[polldaddy:10175070]

The authors’ observations

We initially considered a diagnosis of MDD due to Ms. A’s past history of depressive episodes, her recent increase in tearfulness and anhedonia, and her self-injurious behaviors. However, diagnosis of a mood disorder was complicated by her complex history of longstanding MS and other psychosocial factors.

Continue to: Several factors contribute to the neuropsychiatric course of patients with MS...

Several factors contribute to the neuropsychiatric course of patients with MS, including the impact of the patient accepting a chronic and incurable diagnosis, the toll of progressive neurologic/physical disability and subsequent decline in functioning, and the availability of a support system.2 As opposed to disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, where disease progression is relatively more predictable, the culture of MS involves the obscurity of symptom fluctuation, both from the patient’s and/or clinician’s viewpoint. Psychiatric and neurologic symptoms may be difficult to predict, leading to speculation and projection as to the progression of the disease. The diagnosis of psychiatric conditions, such as depression, can be complicated by the fact that MS and psychiatric disorders share presenting symptoms; for example, disturbances in sleep and concentration may be seen in both conditions.

While studies have examined the neurobiology of MS lesions and their effects on mood symptoms, there has been no clear consensus of specific lesion distributions, although lesions in the superior frontal lobe and right temporal lobe regions have been identified in depressed MS patients.8 Lesions in the left frontal lobe may also have some contribution; studies have shown hyperintense lesion load in this area, which was found to be an independent predictor of MDD in MS.9 This, in turn, coincides with the association of left frontal cortex involvement in modulating affective depression, evidenced by studies that have associated depression severity with left frontal lobe damage in post-stroke patients10 as well as the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation of the left prefrontal cortex for treatment-resistant MDD.11 Lesions along the orbitofrontal prefrontal cortex have similarly been connected to mood lability and impulsivity, which are characteristics of bipolar disorder.8 Within the general population, bipolar disorder is associated with areas of hyperintensity on MRI, particularly in the frontal and parietal white matter, which may provide clues as to the role of MS demyelinating lesions in similar locations, although research concerning the relationship between MS and bipolar disorder remains limited.12

EVALUATION No exacerbation of MS