User login

Supreme Court upholds part of Indiana abortion law

In a three-page, unsigned opinion issued May 28, justices wrote that Indiana has a legitimate interest in proper disposition of fetal remains and that the state’s burial/cremation mandate is rational. However, justices said they would not take up the second part of the law regarding abortions based on race, sex, or disability because not enough appeals courts have decided the issue. The court emphasized it was not expressing any view on the merits of the second question.

The opinion stems from an antiabortion measure signed into law by then–Indiana Governor Mike Pence (R) in 2016. According to the law, the health facility where an abortion occurred is required to dispose of fetal remains either by cremation or internment unless the woman or an associated party take possession of the remains. The measure allows the woman or associated party to choose a location of final disposition provided that the parties pay the costs for such arrangements. The second part of the law prohibits an abortion from being performed solely because of the fetus’s expected race, sex, diagnosis, or disability.

Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky sued over the law, arguing that the measure was unconstitutional. Indiana officials countered the disposal requirements provided fetuses dignity in death and that the law’s abortion restrictions prevented discrimination of particular fetuses in light of technological advances in genetic screening. In 2018, a three-judge panel of the Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit struck down the entire law. The panel wrote that well-established Supreme Court precedent allows a woman to terminate her pregnancy for any reason and that the Indiana law invaded a woman’s privacy by examining the underlying basis of her decision for an abortion.

In the Supreme Court’s May 28 filing, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote separately, each stating they would have upheld the lower court’s ban of the entire law. Justice Clarence Thomas, meanwhile, wrote a lengthy separate opinion, agreeing with the court’s decision, but expressing concern over the use of abortion as a “tool of modern-day eugenics.”

“The court will soon need to confront the constitutionality of laws like Indiana’s,” Justice Thomas wrote. “Enshrining a constitutional right to an abortion based solely on the race, sex or disability of an unborn child, as Planned Parenthood advocates, would constitutionalize the views of the 20th-century eugenics movement.”

The Supreme Court’s decision on the Indiana law comes just weeks after two other stringent state abortion measures were signed into law. On May 7, 2019, Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp (R) signed into law a statute that bars physicians from performing an abortion after a heartbeat is detected – usually at about 6 weeks of pregnancy. On May 15, Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey (R) signed a law that would ban abortion at every pregnancy stage and penalize physicians with a Class A felony for performing an abortion and charge them with a Class C felony for attempting to perform an abortion.

Analysts say the Alabama law, in particular, could land in front of the Supreme Court as a direct challenge to Roe v. Wade. Abortion critics have been encouraged by the Supreme Court appointment of right-leaning Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh and hope the Alabama measure will drive the Supreme Court to reconsider its central holding in Roe, court watchers said.

In a three-page, unsigned opinion issued May 28, justices wrote that Indiana has a legitimate interest in proper disposition of fetal remains and that the state’s burial/cremation mandate is rational. However, justices said they would not take up the second part of the law regarding abortions based on race, sex, or disability because not enough appeals courts have decided the issue. The court emphasized it was not expressing any view on the merits of the second question.

The opinion stems from an antiabortion measure signed into law by then–Indiana Governor Mike Pence (R) in 2016. According to the law, the health facility where an abortion occurred is required to dispose of fetal remains either by cremation or internment unless the woman or an associated party take possession of the remains. The measure allows the woman or associated party to choose a location of final disposition provided that the parties pay the costs for such arrangements. The second part of the law prohibits an abortion from being performed solely because of the fetus’s expected race, sex, diagnosis, or disability.

Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky sued over the law, arguing that the measure was unconstitutional. Indiana officials countered the disposal requirements provided fetuses dignity in death and that the law’s abortion restrictions prevented discrimination of particular fetuses in light of technological advances in genetic screening. In 2018, a three-judge panel of the Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit struck down the entire law. The panel wrote that well-established Supreme Court precedent allows a woman to terminate her pregnancy for any reason and that the Indiana law invaded a woman’s privacy by examining the underlying basis of her decision for an abortion.

In the Supreme Court’s May 28 filing, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote separately, each stating they would have upheld the lower court’s ban of the entire law. Justice Clarence Thomas, meanwhile, wrote a lengthy separate opinion, agreeing with the court’s decision, but expressing concern over the use of abortion as a “tool of modern-day eugenics.”

“The court will soon need to confront the constitutionality of laws like Indiana’s,” Justice Thomas wrote. “Enshrining a constitutional right to an abortion based solely on the race, sex or disability of an unborn child, as Planned Parenthood advocates, would constitutionalize the views of the 20th-century eugenics movement.”

The Supreme Court’s decision on the Indiana law comes just weeks after two other stringent state abortion measures were signed into law. On May 7, 2019, Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp (R) signed into law a statute that bars physicians from performing an abortion after a heartbeat is detected – usually at about 6 weeks of pregnancy. On May 15, Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey (R) signed a law that would ban abortion at every pregnancy stage and penalize physicians with a Class A felony for performing an abortion and charge them with a Class C felony for attempting to perform an abortion.

Analysts say the Alabama law, in particular, could land in front of the Supreme Court as a direct challenge to Roe v. Wade. Abortion critics have been encouraged by the Supreme Court appointment of right-leaning Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh and hope the Alabama measure will drive the Supreme Court to reconsider its central holding in Roe, court watchers said.

In a three-page, unsigned opinion issued May 28, justices wrote that Indiana has a legitimate interest in proper disposition of fetal remains and that the state’s burial/cremation mandate is rational. However, justices said they would not take up the second part of the law regarding abortions based on race, sex, or disability because not enough appeals courts have decided the issue. The court emphasized it was not expressing any view on the merits of the second question.

The opinion stems from an antiabortion measure signed into law by then–Indiana Governor Mike Pence (R) in 2016. According to the law, the health facility where an abortion occurred is required to dispose of fetal remains either by cremation or internment unless the woman or an associated party take possession of the remains. The measure allows the woman or associated party to choose a location of final disposition provided that the parties pay the costs for such arrangements. The second part of the law prohibits an abortion from being performed solely because of the fetus’s expected race, sex, diagnosis, or disability.

Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky sued over the law, arguing that the measure was unconstitutional. Indiana officials countered the disposal requirements provided fetuses dignity in death and that the law’s abortion restrictions prevented discrimination of particular fetuses in light of technological advances in genetic screening. In 2018, a three-judge panel of the Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit struck down the entire law. The panel wrote that well-established Supreme Court precedent allows a woman to terminate her pregnancy for any reason and that the Indiana law invaded a woman’s privacy by examining the underlying basis of her decision for an abortion.

In the Supreme Court’s May 28 filing, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote separately, each stating they would have upheld the lower court’s ban of the entire law. Justice Clarence Thomas, meanwhile, wrote a lengthy separate opinion, agreeing with the court’s decision, but expressing concern over the use of abortion as a “tool of modern-day eugenics.”

“The court will soon need to confront the constitutionality of laws like Indiana’s,” Justice Thomas wrote. “Enshrining a constitutional right to an abortion based solely on the race, sex or disability of an unborn child, as Planned Parenthood advocates, would constitutionalize the views of the 20th-century eugenics movement.”

The Supreme Court’s decision on the Indiana law comes just weeks after two other stringent state abortion measures were signed into law. On May 7, 2019, Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp (R) signed into law a statute that bars physicians from performing an abortion after a heartbeat is detected – usually at about 6 weeks of pregnancy. On May 15, Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey (R) signed a law that would ban abortion at every pregnancy stage and penalize physicians with a Class A felony for performing an abortion and charge them with a Class C felony for attempting to perform an abortion.

Analysts say the Alabama law, in particular, could land in front of the Supreme Court as a direct challenge to Roe v. Wade. Abortion critics have been encouraged by the Supreme Court appointment of right-leaning Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh and hope the Alabama measure will drive the Supreme Court to reconsider its central holding in Roe, court watchers said.

Team sports may mitigate tough childhoods

Individuals who experienced adverse childhood experiences but also played team sports as teens were less likely to have mental health problems in adulthood than those with childhood challenges who did not play sports, based on data from nearly 5,000 individuals.

Physical and mental health problems are more prominent throughout life among those exposed to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), and physical activity in general and team sports in particular have been shown to improve mental health, wrote Molly C. Easterlin, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, and colleagues.

In a study published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers used data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health to compare the development of depression, anxiety, or depressive symptoms among those with childhood ACEs who did and did not participate in team sports in adolescence.

Overall, team sports participation was significantly associated with reduced odds of depression (adjusted odds ratio, 0.76), anxiety (aOR, 0.70), and depressive symptoms (aOR, 0.85) in young adulthood for individuals with ACEs, compared with those with ACEs who did not play team sports.

Of 9,668 adolescents in the study, 4,888 individuals reported one or more ACEs and 2,084 reported two or more ACEs. The researchers compared data from the 1994-1995 school year when participants were in grades 7-12 and in 2008 to assess their mental health as young adults (aged 24-32 years).

No significant differences in associations appeared between sports participation and mental health between males and females.

The results were limited by several factors including the study design that did not allow for causality and the potential social desirability bias that might lead to underreporting ACEs, Dr. Easterlin and associates noted.

Nonetheless, “given that participation in team sports was associated with improved adult mental health among those with ACEs, and parents might consider enrolling their children with ACEs in team sports,” they wrote.

Dr. Easterlin is supported by the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center via the UCLA National Clinician Scholars Program. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Easterlin MC et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 May 28. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1212.

Approximately half of children suffer an adverse childhood experience (ACE) that can negatively affect their mental health throughout life, and “team sports can be an avenue to interrupt these negative sequelae and address the important public health burden of depression,” wrote Amanda E. Paluch, PhD; Nia Heard-Garris, MD, MSc; and Mercedes R. Carnethon, PhD.

However, a significant socioeconomic disparity in team sports for children continues to grow in the United States, driven in part by a youth sports industry and culture that caters to high-income families looking to improve their children’s performance. “Although unintentional, these expenses leave behind lower-income children,” many of whom may be at increased risk for ACEs, the editorialists noted. Many inexpensive, community-based recreation leagues, especially in low-income areas, are often underfunded and unable to update facilities and attract more participants.

The benefits of team sports appear to go beyond the physical, as the study by Easterlin et al. suggests that feeling accepted and connected as part of a team has an impact on mental health. Also, the winning and losing of sports helps build emotional resilience that carries over to other areas of life, the editorialists added.

“Optimizing the opportunities for sports during adolescence requires relatively few resources and is a low-cost way to improve quality of life and reduce the population burden of mental health disorders, especially for adolescents and young adults with histories of ACEs,” they concluded.

Dr. Paluch and Dr. Carnethon are affiliated with the department of preventive medicine and Dr. Heard-Garris is affiliated with the department of pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago. They commented on the study by Easterlin et al (JAMA Pediatr. 2019 May 28. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1209). They reported no conflicts of interest.

Approximately half of children suffer an adverse childhood experience (ACE) that can negatively affect their mental health throughout life, and “team sports can be an avenue to interrupt these negative sequelae and address the important public health burden of depression,” wrote Amanda E. Paluch, PhD; Nia Heard-Garris, MD, MSc; and Mercedes R. Carnethon, PhD.

However, a significant socioeconomic disparity in team sports for children continues to grow in the United States, driven in part by a youth sports industry and culture that caters to high-income families looking to improve their children’s performance. “Although unintentional, these expenses leave behind lower-income children,” many of whom may be at increased risk for ACEs, the editorialists noted. Many inexpensive, community-based recreation leagues, especially in low-income areas, are often underfunded and unable to update facilities and attract more participants.

The benefits of team sports appear to go beyond the physical, as the study by Easterlin et al. suggests that feeling accepted and connected as part of a team has an impact on mental health. Also, the winning and losing of sports helps build emotional resilience that carries over to other areas of life, the editorialists added.

“Optimizing the opportunities for sports during adolescence requires relatively few resources and is a low-cost way to improve quality of life and reduce the population burden of mental health disorders, especially for adolescents and young adults with histories of ACEs,” they concluded.

Dr. Paluch and Dr. Carnethon are affiliated with the department of preventive medicine and Dr. Heard-Garris is affiliated with the department of pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago. They commented on the study by Easterlin et al (JAMA Pediatr. 2019 May 28. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1209). They reported no conflicts of interest.

Approximately half of children suffer an adverse childhood experience (ACE) that can negatively affect their mental health throughout life, and “team sports can be an avenue to interrupt these negative sequelae and address the important public health burden of depression,” wrote Amanda E. Paluch, PhD; Nia Heard-Garris, MD, MSc; and Mercedes R. Carnethon, PhD.

However, a significant socioeconomic disparity in team sports for children continues to grow in the United States, driven in part by a youth sports industry and culture that caters to high-income families looking to improve their children’s performance. “Although unintentional, these expenses leave behind lower-income children,” many of whom may be at increased risk for ACEs, the editorialists noted. Many inexpensive, community-based recreation leagues, especially in low-income areas, are often underfunded and unable to update facilities and attract more participants.

The benefits of team sports appear to go beyond the physical, as the study by Easterlin et al. suggests that feeling accepted and connected as part of a team has an impact on mental health. Also, the winning and losing of sports helps build emotional resilience that carries over to other areas of life, the editorialists added.

“Optimizing the opportunities for sports during adolescence requires relatively few resources and is a low-cost way to improve quality of life and reduce the population burden of mental health disorders, especially for adolescents and young adults with histories of ACEs,” they concluded.

Dr. Paluch and Dr. Carnethon are affiliated with the department of preventive medicine and Dr. Heard-Garris is affiliated with the department of pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago. They commented on the study by Easterlin et al (JAMA Pediatr. 2019 May 28. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1209). They reported no conflicts of interest.

Individuals who experienced adverse childhood experiences but also played team sports as teens were less likely to have mental health problems in adulthood than those with childhood challenges who did not play sports, based on data from nearly 5,000 individuals.

Physical and mental health problems are more prominent throughout life among those exposed to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), and physical activity in general and team sports in particular have been shown to improve mental health, wrote Molly C. Easterlin, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, and colleagues.

In a study published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers used data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health to compare the development of depression, anxiety, or depressive symptoms among those with childhood ACEs who did and did not participate in team sports in adolescence.

Overall, team sports participation was significantly associated with reduced odds of depression (adjusted odds ratio, 0.76), anxiety (aOR, 0.70), and depressive symptoms (aOR, 0.85) in young adulthood for individuals with ACEs, compared with those with ACEs who did not play team sports.

Of 9,668 adolescents in the study, 4,888 individuals reported one or more ACEs and 2,084 reported two or more ACEs. The researchers compared data from the 1994-1995 school year when participants were in grades 7-12 and in 2008 to assess their mental health as young adults (aged 24-32 years).

No significant differences in associations appeared between sports participation and mental health between males and females.

The results were limited by several factors including the study design that did not allow for causality and the potential social desirability bias that might lead to underreporting ACEs, Dr. Easterlin and associates noted.

Nonetheless, “given that participation in team sports was associated with improved adult mental health among those with ACEs, and parents might consider enrolling their children with ACEs in team sports,” they wrote.

Dr. Easterlin is supported by the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center via the UCLA National Clinician Scholars Program. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Easterlin MC et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 May 28. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1212.

Individuals who experienced adverse childhood experiences but also played team sports as teens were less likely to have mental health problems in adulthood than those with childhood challenges who did not play sports, based on data from nearly 5,000 individuals.

Physical and mental health problems are more prominent throughout life among those exposed to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), and physical activity in general and team sports in particular have been shown to improve mental health, wrote Molly C. Easterlin, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, and colleagues.

In a study published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers used data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health to compare the development of depression, anxiety, or depressive symptoms among those with childhood ACEs who did and did not participate in team sports in adolescence.

Overall, team sports participation was significantly associated with reduced odds of depression (adjusted odds ratio, 0.76), anxiety (aOR, 0.70), and depressive symptoms (aOR, 0.85) in young adulthood for individuals with ACEs, compared with those with ACEs who did not play team sports.

Of 9,668 adolescents in the study, 4,888 individuals reported one or more ACEs and 2,084 reported two or more ACEs. The researchers compared data from the 1994-1995 school year when participants were in grades 7-12 and in 2008 to assess their mental health as young adults (aged 24-32 years).

No significant differences in associations appeared between sports participation and mental health between males and females.

The results were limited by several factors including the study design that did not allow for causality and the potential social desirability bias that might lead to underreporting ACEs, Dr. Easterlin and associates noted.

Nonetheless, “given that participation in team sports was associated with improved adult mental health among those with ACEs, and parents might consider enrolling their children with ACEs in team sports,” they wrote.

Dr. Easterlin is supported by the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center via the UCLA National Clinician Scholars Program. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Easterlin MC et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 May 28. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1212.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

When adolescents visit the ED, 10% leave with an opioid

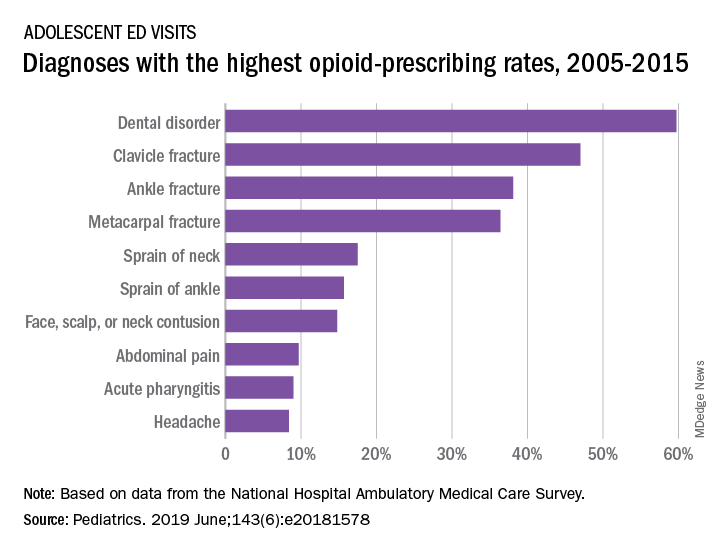

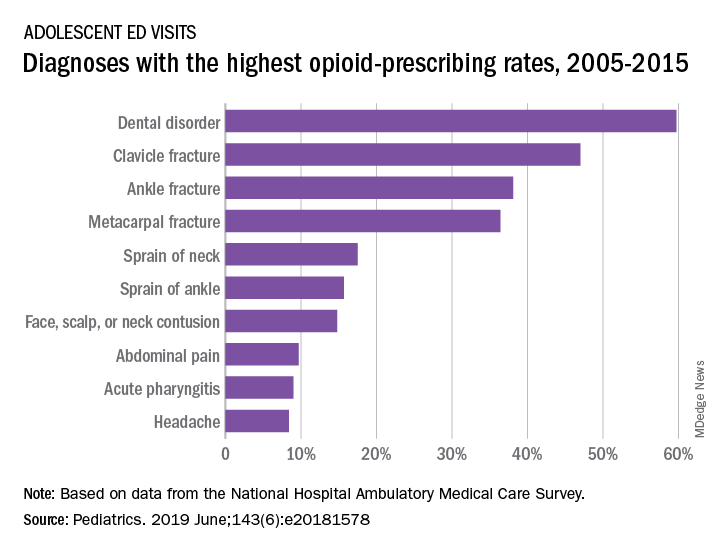

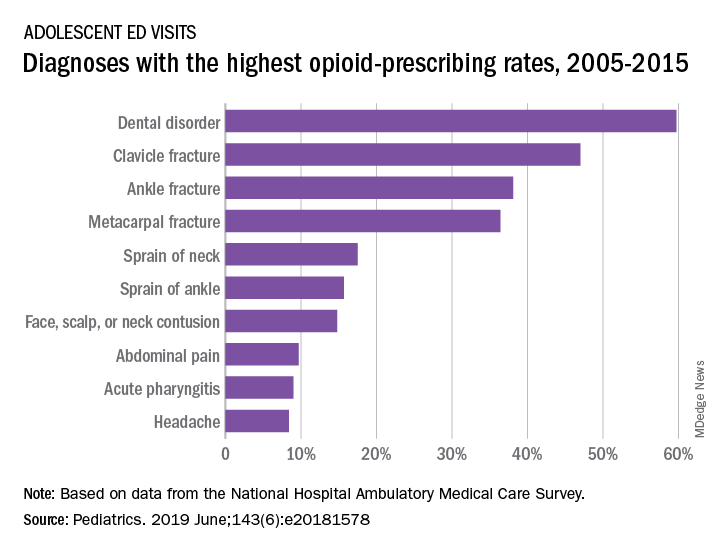

although there was a small but significant decrease in prescriptions over that time, according to an analysis of two nationwide ambulatory care surveys.

For adolescents aged 13-17 years, 10.4% of ED visits were associated with a prescription for an opioid versus 1.6% among outpatient visits. There was a slight but significant decrease in the rate of opioid prescriptions in the ED setting over the study period, with an odds ratio of 0.95 (95% confidence interval, 0.92-0.97), but there was no significant change in the trend over time in the outpatient setting (OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.99-1.09), Joel D. Hudgins, MD, and associates reported in Pediatrics.

“Opioid prescribing in ambulatory care visits is particularly high in the ED setting and … certain diagnoses appear to be routinely treated with an opioid,” said Dr. Hudgins and associates from Boston Children’s Hospital.

The highest rates of opioid prescribing among adolescents visiting the ED involved dental disorders (60%) and acute injuries such as fractures of the clavicle (47%), ankle (38%), and metacarpals (36%). “However, when considering the total volume of opioid prescriptions dispensed [over 7.8 million during 2005-2015], certain common conditions, including abdominal pain, acute pharyngitis, urinary tract infection, and headache, contributed large numbers of prescriptions as well,” they added.

The study involved data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (hospital-based EDs) and the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (office-based practices), which both are conducted annually by the National Center for Health Statistics.

The senior investigator is supported by an award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund by the Harvard-MIT Center for Regulatory Science. The authors said that they have no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Hudgins JD et al. Pediatrics. 2019 June. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1578.

although there was a small but significant decrease in prescriptions over that time, according to an analysis of two nationwide ambulatory care surveys.

For adolescents aged 13-17 years, 10.4% of ED visits were associated with a prescription for an opioid versus 1.6% among outpatient visits. There was a slight but significant decrease in the rate of opioid prescriptions in the ED setting over the study period, with an odds ratio of 0.95 (95% confidence interval, 0.92-0.97), but there was no significant change in the trend over time in the outpatient setting (OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.99-1.09), Joel D. Hudgins, MD, and associates reported in Pediatrics.

“Opioid prescribing in ambulatory care visits is particularly high in the ED setting and … certain diagnoses appear to be routinely treated with an opioid,” said Dr. Hudgins and associates from Boston Children’s Hospital.

The highest rates of opioid prescribing among adolescents visiting the ED involved dental disorders (60%) and acute injuries such as fractures of the clavicle (47%), ankle (38%), and metacarpals (36%). “However, when considering the total volume of opioid prescriptions dispensed [over 7.8 million during 2005-2015], certain common conditions, including abdominal pain, acute pharyngitis, urinary tract infection, and headache, contributed large numbers of prescriptions as well,” they added.

The study involved data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (hospital-based EDs) and the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (office-based practices), which both are conducted annually by the National Center for Health Statistics.

The senior investigator is supported by an award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund by the Harvard-MIT Center for Regulatory Science. The authors said that they have no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Hudgins JD et al. Pediatrics. 2019 June. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1578.

although there was a small but significant decrease in prescriptions over that time, according to an analysis of two nationwide ambulatory care surveys.

For adolescents aged 13-17 years, 10.4% of ED visits were associated with a prescription for an opioid versus 1.6% among outpatient visits. There was a slight but significant decrease in the rate of opioid prescriptions in the ED setting over the study period, with an odds ratio of 0.95 (95% confidence interval, 0.92-0.97), but there was no significant change in the trend over time in the outpatient setting (OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.99-1.09), Joel D. Hudgins, MD, and associates reported in Pediatrics.

“Opioid prescribing in ambulatory care visits is particularly high in the ED setting and … certain diagnoses appear to be routinely treated with an opioid,” said Dr. Hudgins and associates from Boston Children’s Hospital.

The highest rates of opioid prescribing among adolescents visiting the ED involved dental disorders (60%) and acute injuries such as fractures of the clavicle (47%), ankle (38%), and metacarpals (36%). “However, when considering the total volume of opioid prescriptions dispensed [over 7.8 million during 2005-2015], certain common conditions, including abdominal pain, acute pharyngitis, urinary tract infection, and headache, contributed large numbers of prescriptions as well,” they added.

The study involved data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (hospital-based EDs) and the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (office-based practices), which both are conducted annually by the National Center for Health Statistics.

The senior investigator is supported by an award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund by the Harvard-MIT Center for Regulatory Science. The authors said that they have no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Hudgins JD et al. Pediatrics. 2019 June. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1578.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Beyond symptom improvement: Practicing happiness

Kailah is a 13-year-old cisgender female with two working parents, two younger siblings, and a history of mild asthma and overweight who recently presented for a problem-focused visit related to increasing anxiety. An interview of Kailah and her parents led to a diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder, and she was referred for cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and started on a low-dose SSRI. She now presents 3 months later with decreased anxiety and is compliant with the SSRI and CBT. What next?

Positive psychology and psychiatry have emerged as scientific disciplines since Seligman et al.1 charged the field of psychology with reclaiming its stake in helping everyday people to thrive, as well as cultivating strengths and talents at each level of society – individual, family, institutional, and beyond. This call to action revealed the shift over time from mental health care toward a focus only on mental illness. And study after study confirmed that being “not depressed,” “not anxious” and so on was not the same as flourishing.2

Returning to Kailah, from a mental-health-as-usual approach, your job may be done. Her symptoms have responded to first-line treatments. Perhaps you even tracked her symptoms with a freely available standardized assessment tool like the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED)3 and noted a significant drop in her generalized anxiety score.

After a couple decades of research, the science of well-being has led to some consistent findings that can be translated into office practice with children and families. As with any new science, the first steps to building well-being are defining and measuring what we are talking about. I recommend the Flourishing Scale4 for its brevity, availability, and ease of use. It covers the domains included in Seligman’s formula for thriving: PERMA. This acronym represents a consolidation of the first decades of research on well-being, and stands for Positive Emotions, Engagement, (Positive) Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishments. For a readable but deeper look at the science behind this, check out Seligman’s “Flourish.”5

With the Flourishing Scale total score as a starting point, the acronym PERMA itself can be a good rubric to guide assessment and treatment planning in the office. You can query each of the elements to understand a youth’s current status and areas for building strengths. What brings positive emotions? What activities bring a sense of harmonious engagement without self-consciousness or awareness of time (such as a flow state)? What supportive relationships exist? Where does the youth find meaning or purpose – connection to something larger than themselves (family, work, community, teams, religion, and so on)? And where does the youth derive a sense of competence or self-esteem – something they are good at (accomplishment)?

Your clinical recommendations can flow from this assessment discussion, melding the patient’s and family’s strengths and priorities with evidence-based interventions. “The Resilience Drive,” by Alexia Michiels,6 is a good source for the latter – each chapter has segments relating research to straightforward happiness practices. The Growing Happy card deck (available online) also has brief and usable recommendations suitable for many young people. You can use these during office visits, loan out cards, gift them to families, or recommend families purchase a deck.

To build relationships, I recommend the StoryCorps and 36 Questions To Fall In Love apps. They are free and can be used with parents, peers, or others to build relationship supports and positive intimacy. Try them out yourself first; they essentially provide a platform to generate vulnerable conversations.

Mindfulness is a great antidote to lack of engagement, and it can be practiced in a variety of forms. Card decks make good office props or giveaways, including Growing Mindful (mindfulness practices for all ages) and the YogaKids Toolbox. Plus, there’s an app for that – in fact, many. Two that are free and include materials accessible for younger age groups are Smiling Mind (a nonprofit) and Insight Timer (searchable). This can build engagement and counter negative emotions.

For increasing engagement and flow, I recommend patients and family members assess their character strengths at Strengths-Based Resilience by the University of Toronto SSQ72. Research shows that using your strengths in novel ways lowers depression risk, increases happiness,7 and may be a key to increasing engagement in everyday activities.

When Kailah came in for her next visit, a discussion of PERMA led to identifying time with her family and time with her dog as significant relationship supports that bring positive emotions. However, she struggled to identify a realm where she felt some sense of mastery or competence. Taking the strengths survey (SSQ72) brought out her strengths of love of learning and curiosity. This led to her volunteering at her local library – assisting with programs and eventually creating and leading a teens’ book group. Her CBT therapist supported her through these challenges, and she was able to taper the frequency of therapy sessions so that Kailah only returns for a booster session now every 6 months or so. While she still identifies as an anxious person, Kailah has broadened her self-image to include her resilience and love of learning as core strengths.

Dr. Andrew J. Rosenfeld is an assistant professor in the departments of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont Medical Center, Burlington. He said he has no relevant disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):5-14.

2. Am Psychol. 2007 Feb-Mar;62(2):95-108.

3. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999 Oct;38(10):1230-6.

4. Soc Indic Res. 2009; 39:247-66.

5. “Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being” (New York: Free Press, 2011).

6. “The Resilience Drive” (Switzerland: Favre, 2017).

7. Am Psychol. 2005 Jul-Aug;60(5):410-21.

Kailah is a 13-year-old cisgender female with two working parents, two younger siblings, and a history of mild asthma and overweight who recently presented for a problem-focused visit related to increasing anxiety. An interview of Kailah and her parents led to a diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder, and she was referred for cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and started on a low-dose SSRI. She now presents 3 months later with decreased anxiety and is compliant with the SSRI and CBT. What next?

Positive psychology and psychiatry have emerged as scientific disciplines since Seligman et al.1 charged the field of psychology with reclaiming its stake in helping everyday people to thrive, as well as cultivating strengths and talents at each level of society – individual, family, institutional, and beyond. This call to action revealed the shift over time from mental health care toward a focus only on mental illness. And study after study confirmed that being “not depressed,” “not anxious” and so on was not the same as flourishing.2

Returning to Kailah, from a mental-health-as-usual approach, your job may be done. Her symptoms have responded to first-line treatments. Perhaps you even tracked her symptoms with a freely available standardized assessment tool like the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED)3 and noted a significant drop in her generalized anxiety score.

After a couple decades of research, the science of well-being has led to some consistent findings that can be translated into office practice with children and families. As with any new science, the first steps to building well-being are defining and measuring what we are talking about. I recommend the Flourishing Scale4 for its brevity, availability, and ease of use. It covers the domains included in Seligman’s formula for thriving: PERMA. This acronym represents a consolidation of the first decades of research on well-being, and stands for Positive Emotions, Engagement, (Positive) Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishments. For a readable but deeper look at the science behind this, check out Seligman’s “Flourish.”5

With the Flourishing Scale total score as a starting point, the acronym PERMA itself can be a good rubric to guide assessment and treatment planning in the office. You can query each of the elements to understand a youth’s current status and areas for building strengths. What brings positive emotions? What activities bring a sense of harmonious engagement without self-consciousness or awareness of time (such as a flow state)? What supportive relationships exist? Where does the youth find meaning or purpose – connection to something larger than themselves (family, work, community, teams, religion, and so on)? And where does the youth derive a sense of competence or self-esteem – something they are good at (accomplishment)?

Your clinical recommendations can flow from this assessment discussion, melding the patient’s and family’s strengths and priorities with evidence-based interventions. “The Resilience Drive,” by Alexia Michiels,6 is a good source for the latter – each chapter has segments relating research to straightforward happiness practices. The Growing Happy card deck (available online) also has brief and usable recommendations suitable for many young people. You can use these during office visits, loan out cards, gift them to families, or recommend families purchase a deck.

To build relationships, I recommend the StoryCorps and 36 Questions To Fall In Love apps. They are free and can be used with parents, peers, or others to build relationship supports and positive intimacy. Try them out yourself first; they essentially provide a platform to generate vulnerable conversations.

Mindfulness is a great antidote to lack of engagement, and it can be practiced in a variety of forms. Card decks make good office props or giveaways, including Growing Mindful (mindfulness practices for all ages) and the YogaKids Toolbox. Plus, there’s an app for that – in fact, many. Two that are free and include materials accessible for younger age groups are Smiling Mind (a nonprofit) and Insight Timer (searchable). This can build engagement and counter negative emotions.

For increasing engagement and flow, I recommend patients and family members assess their character strengths at Strengths-Based Resilience by the University of Toronto SSQ72. Research shows that using your strengths in novel ways lowers depression risk, increases happiness,7 and may be a key to increasing engagement in everyday activities.

When Kailah came in for her next visit, a discussion of PERMA led to identifying time with her family and time with her dog as significant relationship supports that bring positive emotions. However, she struggled to identify a realm where she felt some sense of mastery or competence. Taking the strengths survey (SSQ72) brought out her strengths of love of learning and curiosity. This led to her volunteering at her local library – assisting with programs and eventually creating and leading a teens’ book group. Her CBT therapist supported her through these challenges, and she was able to taper the frequency of therapy sessions so that Kailah only returns for a booster session now every 6 months or so. While she still identifies as an anxious person, Kailah has broadened her self-image to include her resilience and love of learning as core strengths.

Dr. Andrew J. Rosenfeld is an assistant professor in the departments of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont Medical Center, Burlington. He said he has no relevant disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):5-14.

2. Am Psychol. 2007 Feb-Mar;62(2):95-108.

3. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999 Oct;38(10):1230-6.

4. Soc Indic Res. 2009; 39:247-66.

5. “Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being” (New York: Free Press, 2011).

6. “The Resilience Drive” (Switzerland: Favre, 2017).

7. Am Psychol. 2005 Jul-Aug;60(5):410-21.

Kailah is a 13-year-old cisgender female with two working parents, two younger siblings, and a history of mild asthma and overweight who recently presented for a problem-focused visit related to increasing anxiety. An interview of Kailah and her parents led to a diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder, and she was referred for cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and started on a low-dose SSRI. She now presents 3 months later with decreased anxiety and is compliant with the SSRI and CBT. What next?

Positive psychology and psychiatry have emerged as scientific disciplines since Seligman et al.1 charged the field of psychology with reclaiming its stake in helping everyday people to thrive, as well as cultivating strengths and talents at each level of society – individual, family, institutional, and beyond. This call to action revealed the shift over time from mental health care toward a focus only on mental illness. And study after study confirmed that being “not depressed,” “not anxious” and so on was not the same as flourishing.2

Returning to Kailah, from a mental-health-as-usual approach, your job may be done. Her symptoms have responded to first-line treatments. Perhaps you even tracked her symptoms with a freely available standardized assessment tool like the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED)3 and noted a significant drop in her generalized anxiety score.

After a couple decades of research, the science of well-being has led to some consistent findings that can be translated into office practice with children and families. As with any new science, the first steps to building well-being are defining and measuring what we are talking about. I recommend the Flourishing Scale4 for its brevity, availability, and ease of use. It covers the domains included in Seligman’s formula for thriving: PERMA. This acronym represents a consolidation of the first decades of research on well-being, and stands for Positive Emotions, Engagement, (Positive) Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishments. For a readable but deeper look at the science behind this, check out Seligman’s “Flourish.”5

With the Flourishing Scale total score as a starting point, the acronym PERMA itself can be a good rubric to guide assessment and treatment planning in the office. You can query each of the elements to understand a youth’s current status and areas for building strengths. What brings positive emotions? What activities bring a sense of harmonious engagement without self-consciousness or awareness of time (such as a flow state)? What supportive relationships exist? Where does the youth find meaning or purpose – connection to something larger than themselves (family, work, community, teams, religion, and so on)? And where does the youth derive a sense of competence or self-esteem – something they are good at (accomplishment)?

Your clinical recommendations can flow from this assessment discussion, melding the patient’s and family’s strengths and priorities with evidence-based interventions. “The Resilience Drive,” by Alexia Michiels,6 is a good source for the latter – each chapter has segments relating research to straightforward happiness practices. The Growing Happy card deck (available online) also has brief and usable recommendations suitable for many young people. You can use these during office visits, loan out cards, gift them to families, or recommend families purchase a deck.

To build relationships, I recommend the StoryCorps and 36 Questions To Fall In Love apps. They are free and can be used with parents, peers, or others to build relationship supports and positive intimacy. Try them out yourself first; they essentially provide a platform to generate vulnerable conversations.

Mindfulness is a great antidote to lack of engagement, and it can be practiced in a variety of forms. Card decks make good office props or giveaways, including Growing Mindful (mindfulness practices for all ages) and the YogaKids Toolbox. Plus, there’s an app for that – in fact, many. Two that are free and include materials accessible for younger age groups are Smiling Mind (a nonprofit) and Insight Timer (searchable). This can build engagement and counter negative emotions.

For increasing engagement and flow, I recommend patients and family members assess their character strengths at Strengths-Based Resilience by the University of Toronto SSQ72. Research shows that using your strengths in novel ways lowers depression risk, increases happiness,7 and may be a key to increasing engagement in everyday activities.

When Kailah came in for her next visit, a discussion of PERMA led to identifying time with her family and time with her dog as significant relationship supports that bring positive emotions. However, she struggled to identify a realm where she felt some sense of mastery or competence. Taking the strengths survey (SSQ72) brought out her strengths of love of learning and curiosity. This led to her volunteering at her local library – assisting with programs and eventually creating and leading a teens’ book group. Her CBT therapist supported her through these challenges, and she was able to taper the frequency of therapy sessions so that Kailah only returns for a booster session now every 6 months or so. While she still identifies as an anxious person, Kailah has broadened her self-image to include her resilience and love of learning as core strengths.

Dr. Andrew J. Rosenfeld is an assistant professor in the departments of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont Medical Center, Burlington. He said he has no relevant disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):5-14.

2. Am Psychol. 2007 Feb-Mar;62(2):95-108.

3. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999 Oct;38(10):1230-6.

4. Soc Indic Res. 2009; 39:247-66.

5. “Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being” (New York: Free Press, 2011).

6. “The Resilience Drive” (Switzerland: Favre, 2017).

7. Am Psychol. 2005 Jul-Aug;60(5):410-21.

Risk of suicide attempt is higher in children of opioid users

according to an evaluation of a medical claims database from which a sample of more than 200,00 privately insured parents was evaluated.

Based on data collected between the years 2010 and 2016, the study raises the possibility that rising rates of opioid prescriptions and rising rates of suicide in adolescents and children are linked, said David A. Brent, of the University of Pittsburgh, and associates.

The relationship was considered sufficiently strong that the authors recommended clinicians consider mental health screening of children whose parents are known to have had extensive opioid exposure.

Addressing both opioid use in parents and the mental health in their children “may help, at least in part, to reverse the current upward trend in mortality due to the twin epidemics of suicide and opioid overdose,” said Dr. Brent and associates, whose findings were published in JAMA Psychiatry.

From a pool of more than 1 million parents aged 30-50 years in the claims database, 121,306 parents with extensive opioid use – defined as receiving opioid prescriptions for more than 365 days between 2010 and 2016 – were matched with 121,306 controls in the same age range. Children aged 10-19 years in both groups were compared for suicide attempts.

Overall, the rate of prescription opioid use as defined for inclusion in this study was 5% in the target parent population evaluated in this claims database.

Of the 184,142 children with parents exposed to opioids, 678 (0.37%) attempted suicide versus 212 (0.14%) of the 148,395 children from the nonopioid group. Expressed as a rate per 10,000 person years, the figures were 11.7 and 5.9 for the opioid and nonopioid groups, respectively.

When translated into an odds ratio (OR), the increased risk of suicide was found to be almost twice as high (OR 1.99) among children with parents meeting the study criteria for prescription opioid use. The OR was only slightly reduced (OR 1.85) after adjustment for sex and age.

Suicide attempts overall were higher in daughters than sons and in older children (15 years of age or older) than younger (ages 10 to less than 15 years) whether or not parents were taking opioids, but the relative risk remained consistently higher across all these subgroups when comparing those whose parents were taking prescription opioids with those whose parents were not.

As in past studies, children were more likely to make a suicide attempt if they had a parent who had a history of attempting suicide. However, the authors reported a significantly elevated risk of a suicide attempt for children of prescription opioid users after adjustment for this factor as well as for child depression, parental depression, and parental substance use disorder (OR, 1.45).

The OR of a suicide attempt was not significantly higher for a suicide attempt among those children with both parents taking prescription opioids relative to opioid use in only one parent (OR 1.05).

Dr. Brent and associates acknowledged that these data do not confirm that the rising rate of prescription opioid use is linked to the recent parallel rise in suicide attempts among children. However, they did conclude that children of parents using opioid prescriptions are at risk and might be an appropriate target for suicide prevention.

“Recognition and treatment of patients with opioid use disorder, attendance to comorbid conditions in affected parents, and screening and appropriate referral of their children may help” address both major public health issues, they maintained.

The study was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant. Dr Brent reported receiving royalties from Guilford Press, eRT, and UpToDate. Dr. Gibbons has served as an expert witness in cases related to suicide involving pharmaceutical companies, such as Pfizer and GlaxoSmithKline.

SOURCE: Brent DA et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 May 22 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0940.

according to an evaluation of a medical claims database from which a sample of more than 200,00 privately insured parents was evaluated.

Based on data collected between the years 2010 and 2016, the study raises the possibility that rising rates of opioid prescriptions and rising rates of suicide in adolescents and children are linked, said David A. Brent, of the University of Pittsburgh, and associates.

The relationship was considered sufficiently strong that the authors recommended clinicians consider mental health screening of children whose parents are known to have had extensive opioid exposure.

Addressing both opioid use in parents and the mental health in their children “may help, at least in part, to reverse the current upward trend in mortality due to the twin epidemics of suicide and opioid overdose,” said Dr. Brent and associates, whose findings were published in JAMA Psychiatry.

From a pool of more than 1 million parents aged 30-50 years in the claims database, 121,306 parents with extensive opioid use – defined as receiving opioid prescriptions for more than 365 days between 2010 and 2016 – were matched with 121,306 controls in the same age range. Children aged 10-19 years in both groups were compared for suicide attempts.

Overall, the rate of prescription opioid use as defined for inclusion in this study was 5% in the target parent population evaluated in this claims database.

Of the 184,142 children with parents exposed to opioids, 678 (0.37%) attempted suicide versus 212 (0.14%) of the 148,395 children from the nonopioid group. Expressed as a rate per 10,000 person years, the figures were 11.7 and 5.9 for the opioid and nonopioid groups, respectively.

When translated into an odds ratio (OR), the increased risk of suicide was found to be almost twice as high (OR 1.99) among children with parents meeting the study criteria for prescription opioid use. The OR was only slightly reduced (OR 1.85) after adjustment for sex and age.

Suicide attempts overall were higher in daughters than sons and in older children (15 years of age or older) than younger (ages 10 to less than 15 years) whether or not parents were taking opioids, but the relative risk remained consistently higher across all these subgroups when comparing those whose parents were taking prescription opioids with those whose parents were not.

As in past studies, children were more likely to make a suicide attempt if they had a parent who had a history of attempting suicide. However, the authors reported a significantly elevated risk of a suicide attempt for children of prescription opioid users after adjustment for this factor as well as for child depression, parental depression, and parental substance use disorder (OR, 1.45).

The OR of a suicide attempt was not significantly higher for a suicide attempt among those children with both parents taking prescription opioids relative to opioid use in only one parent (OR 1.05).

Dr. Brent and associates acknowledged that these data do not confirm that the rising rate of prescription opioid use is linked to the recent parallel rise in suicide attempts among children. However, they did conclude that children of parents using opioid prescriptions are at risk and might be an appropriate target for suicide prevention.

“Recognition and treatment of patients with opioid use disorder, attendance to comorbid conditions in affected parents, and screening and appropriate referral of their children may help” address both major public health issues, they maintained.

The study was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant. Dr Brent reported receiving royalties from Guilford Press, eRT, and UpToDate. Dr. Gibbons has served as an expert witness in cases related to suicide involving pharmaceutical companies, such as Pfizer and GlaxoSmithKline.

SOURCE: Brent DA et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 May 22 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0940.

according to an evaluation of a medical claims database from which a sample of more than 200,00 privately insured parents was evaluated.

Based on data collected between the years 2010 and 2016, the study raises the possibility that rising rates of opioid prescriptions and rising rates of suicide in adolescents and children are linked, said David A. Brent, of the University of Pittsburgh, and associates.

The relationship was considered sufficiently strong that the authors recommended clinicians consider mental health screening of children whose parents are known to have had extensive opioid exposure.

Addressing both opioid use in parents and the mental health in their children “may help, at least in part, to reverse the current upward trend in mortality due to the twin epidemics of suicide and opioid overdose,” said Dr. Brent and associates, whose findings were published in JAMA Psychiatry.

From a pool of more than 1 million parents aged 30-50 years in the claims database, 121,306 parents with extensive opioid use – defined as receiving opioid prescriptions for more than 365 days between 2010 and 2016 – were matched with 121,306 controls in the same age range. Children aged 10-19 years in both groups were compared for suicide attempts.

Overall, the rate of prescription opioid use as defined for inclusion in this study was 5% in the target parent population evaluated in this claims database.

Of the 184,142 children with parents exposed to opioids, 678 (0.37%) attempted suicide versus 212 (0.14%) of the 148,395 children from the nonopioid group. Expressed as a rate per 10,000 person years, the figures were 11.7 and 5.9 for the opioid and nonopioid groups, respectively.

When translated into an odds ratio (OR), the increased risk of suicide was found to be almost twice as high (OR 1.99) among children with parents meeting the study criteria for prescription opioid use. The OR was only slightly reduced (OR 1.85) after adjustment for sex and age.

Suicide attempts overall were higher in daughters than sons and in older children (15 years of age or older) than younger (ages 10 to less than 15 years) whether or not parents were taking opioids, but the relative risk remained consistently higher across all these subgroups when comparing those whose parents were taking prescription opioids with those whose parents were not.

As in past studies, children were more likely to make a suicide attempt if they had a parent who had a history of attempting suicide. However, the authors reported a significantly elevated risk of a suicide attempt for children of prescription opioid users after adjustment for this factor as well as for child depression, parental depression, and parental substance use disorder (OR, 1.45).

The OR of a suicide attempt was not significantly higher for a suicide attempt among those children with both parents taking prescription opioids relative to opioid use in only one parent (OR 1.05).

Dr. Brent and associates acknowledged that these data do not confirm that the rising rate of prescription opioid use is linked to the recent parallel rise in suicide attempts among children. However, they did conclude that children of parents using opioid prescriptions are at risk and might be an appropriate target for suicide prevention.

“Recognition and treatment of patients with opioid use disorder, attendance to comorbid conditions in affected parents, and screening and appropriate referral of their children may help” address both major public health issues, they maintained.

The study was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant. Dr Brent reported receiving royalties from Guilford Press, eRT, and UpToDate. Dr. Gibbons has served as an expert witness in cases related to suicide involving pharmaceutical companies, such as Pfizer and GlaxoSmithKline.

SOURCE: Brent DA et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 May 22 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0940.

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

Addressing the sexual and reproductive health needs of trans and gender nonconforming patients

Separating gender identity from sexual identity to allow for more comprehensive history-taking

Grouping the term “transgender” in the abbreviation LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender) has historically been empowering for trans and gender nonconforming (GNC) persons. However, it also has contributed to the misunderstanding that gender identity is interchangeable with sexual identity. This common misconception can be a barrier to trans and GNC patients seeking care from ob.gyns. for their reproductive health needs.

By definition, gender identity refers to an internal experience of one’s gender, of one’s self.1 While gender identity has social implications, it ultimately is something that a person experiences independently of interactions with others. By contrast, sexual orientation has an explicitly relational underpinning because sexual orientation involves attraction to others. The distinction between gender identity and sexual orientation is similar to an internal-versus-external, or a self-versus-other dichotomy. A further nuance to add is that sexual behavior does not always reflect sexual orientation, and sexual behavior can vary along a wide spectrum when gender identity is added to the equation.

Overall, When approaching a sexual history with any patient, but especially a transgender or GNC patient, providers should think deeply about what information is medically relevant.2 The purpose of a sexual history is to identify behaviors that contribute to health risk, including pregnancy, sexually transmitted infection, and social problems such as sex-trafficking or intimate partner violence. The health care provider’s job is to ask questions that will uncover these risk factors.

With the advent of a more inclusive attitude toward gay and lesbian partnership, many providers already have learned to collect the sexual history without assuming the gender of a person’s sexual contacts. Still, when a provider is taking the sexual history, gender often is inappropriately used as proxy for the type of sex that a patient may be having. For example, a provider asking a cisgender woman about her sexual activity may ask, “how many sexual partners have you had in the last year?” But then, the provider may follow-up her response of “three sexual partners in the last year” by asking “men, women, or both?” By asking a patient if the patient’s sexual partners are “men, women, or both,” providers fail to accurately elucidate the risk factors that they are actually seeking when taking a sexual history. The cisgender woman from the above scenario may reply that she has been sleeping only with women for the last year, but if the sexual partners are transgender women, aka a woman who was assigned male at birth and therefore still may use her penis/testes for sexual purposes, then the patient actually may be at risk for pregnancy and may also have a different risk factor profile for sexually transmitted infections than if the patient were sexually active with cisgender women.

A different approach to using gender in taking the sexual history is to speak plainly about which sex organs come into contact during sexual activity. When patients identify as transgender or GNC, a provider first should start by asking them what language they would like providers to use when discussing sex organs.3 One example is that many trans men, both those who have undergone mastectomy as well as those who have not, may not use the word “breasts” to describe their “chests.” This distinction may make the difference between gaining and losing the trust of a trans/GNC patient in your clinic. After identifying how a patient would like to refer to sex organs, a provider can continue by asking which of the patient’s sex partners’ organs come into contact with the patient’s organs during sexual activity. Alternatively, starting with an even more broad line of questioning may be best for some patients, such as “how do you like to have sex?”

Carefully identifying the type of sex and what sex organs are involved has concrete medical implications. Patients assigned female at birth who are on hormone therapy with testosterone may need supportive care if they continue to use their vaginas in sexual encounters because testosterone can lead to a relatively hypoestrogenic state. Patients assigned male at birth who have undergone vaginoplasty procedures may need counseling about how to use and support their neovaginas as well as adjusted testing for dysplasia. Patients assigned female at birth who want to avoid pregnancy may need a nuanced consultation regarding contraception. These are just a few examples of how obstetrician-gynecologists can better support the sexual health of their trans/GNC patients by having an accurate understanding of how a trans/GNC person has sex.

Dr. Joyner is an assistant professor at Emory University, Atlanta, and is the director of gynecologic services in the Gender Center at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta. Dr. Joyner identifies as a cisgender female and uses she/hers/her as her personal pronouns. Dr. Joey Bahng is a PGY-1 resident physician in Emory University’s gynecology & obstetrics residency program. Dr. Bahng identifies as nonbinary and uses they/them/their as their personal pronouns. Dr. Bahng and Dr. Joyner reported no relevant financial disclosures

References

1. Sexual orientation and gender identity definitions. Human Rights Campaign.

2. Taking a sexual history from transgender people. Transforming Health at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

3. Sexual health history: Talking sex with gender non-conforming and trans patients. National LGBT Health Education Center at The Fenway Institute.

Separating gender identity from sexual identity to allow for more comprehensive history-taking

Separating gender identity from sexual identity to allow for more comprehensive history-taking

Grouping the term “transgender” in the abbreviation LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender) has historically been empowering for trans and gender nonconforming (GNC) persons. However, it also has contributed to the misunderstanding that gender identity is interchangeable with sexual identity. This common misconception can be a barrier to trans and GNC patients seeking care from ob.gyns. for their reproductive health needs.

By definition, gender identity refers to an internal experience of one’s gender, of one’s self.1 While gender identity has social implications, it ultimately is something that a person experiences independently of interactions with others. By contrast, sexual orientation has an explicitly relational underpinning because sexual orientation involves attraction to others. The distinction between gender identity and sexual orientation is similar to an internal-versus-external, or a self-versus-other dichotomy. A further nuance to add is that sexual behavior does not always reflect sexual orientation, and sexual behavior can vary along a wide spectrum when gender identity is added to the equation.

Overall, When approaching a sexual history with any patient, but especially a transgender or GNC patient, providers should think deeply about what information is medically relevant.2 The purpose of a sexual history is to identify behaviors that contribute to health risk, including pregnancy, sexually transmitted infection, and social problems such as sex-trafficking or intimate partner violence. The health care provider’s job is to ask questions that will uncover these risk factors.

With the advent of a more inclusive attitude toward gay and lesbian partnership, many providers already have learned to collect the sexual history without assuming the gender of a person’s sexual contacts. Still, when a provider is taking the sexual history, gender often is inappropriately used as proxy for the type of sex that a patient may be having. For example, a provider asking a cisgender woman about her sexual activity may ask, “how many sexual partners have you had in the last year?” But then, the provider may follow-up her response of “three sexual partners in the last year” by asking “men, women, or both?” By asking a patient if the patient’s sexual partners are “men, women, or both,” providers fail to accurately elucidate the risk factors that they are actually seeking when taking a sexual history. The cisgender woman from the above scenario may reply that she has been sleeping only with women for the last year, but if the sexual partners are transgender women, aka a woman who was assigned male at birth and therefore still may use her penis/testes for sexual purposes, then the patient actually may be at risk for pregnancy and may also have a different risk factor profile for sexually transmitted infections than if the patient were sexually active with cisgender women.

A different approach to using gender in taking the sexual history is to speak plainly about which sex organs come into contact during sexual activity. When patients identify as transgender or GNC, a provider first should start by asking them what language they would like providers to use when discussing sex organs.3 One example is that many trans men, both those who have undergone mastectomy as well as those who have not, may not use the word “breasts” to describe their “chests.” This distinction may make the difference between gaining and losing the trust of a trans/GNC patient in your clinic. After identifying how a patient would like to refer to sex organs, a provider can continue by asking which of the patient’s sex partners’ organs come into contact with the patient’s organs during sexual activity. Alternatively, starting with an even more broad line of questioning may be best for some patients, such as “how do you like to have sex?”

Carefully identifying the type of sex and what sex organs are involved has concrete medical implications. Patients assigned female at birth who are on hormone therapy with testosterone may need supportive care if they continue to use their vaginas in sexual encounters because testosterone can lead to a relatively hypoestrogenic state. Patients assigned male at birth who have undergone vaginoplasty procedures may need counseling about how to use and support their neovaginas as well as adjusted testing for dysplasia. Patients assigned female at birth who want to avoid pregnancy may need a nuanced consultation regarding contraception. These are just a few examples of how obstetrician-gynecologists can better support the sexual health of their trans/GNC patients by having an accurate understanding of how a trans/GNC person has sex.

Dr. Joyner is an assistant professor at Emory University, Atlanta, and is the director of gynecologic services in the Gender Center at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta. Dr. Joyner identifies as a cisgender female and uses she/hers/her as her personal pronouns. Dr. Joey Bahng is a PGY-1 resident physician in Emory University’s gynecology & obstetrics residency program. Dr. Bahng identifies as nonbinary and uses they/them/their as their personal pronouns. Dr. Bahng and Dr. Joyner reported no relevant financial disclosures

References

1. Sexual orientation and gender identity definitions. Human Rights Campaign.

2. Taking a sexual history from transgender people. Transforming Health at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

3. Sexual health history: Talking sex with gender non-conforming and trans patients. National LGBT Health Education Center at The Fenway Institute.

Grouping the term “transgender” in the abbreviation LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender) has historically been empowering for trans and gender nonconforming (GNC) persons. However, it also has contributed to the misunderstanding that gender identity is interchangeable with sexual identity. This common misconception can be a barrier to trans and GNC patients seeking care from ob.gyns. for their reproductive health needs.

By definition, gender identity refers to an internal experience of one’s gender, of one’s self.1 While gender identity has social implications, it ultimately is something that a person experiences independently of interactions with others. By contrast, sexual orientation has an explicitly relational underpinning because sexual orientation involves attraction to others. The distinction between gender identity and sexual orientation is similar to an internal-versus-external, or a self-versus-other dichotomy. A further nuance to add is that sexual behavior does not always reflect sexual orientation, and sexual behavior can vary along a wide spectrum when gender identity is added to the equation.

Overall, When approaching a sexual history with any patient, but especially a transgender or GNC patient, providers should think deeply about what information is medically relevant.2 The purpose of a sexual history is to identify behaviors that contribute to health risk, including pregnancy, sexually transmitted infection, and social problems such as sex-trafficking or intimate partner violence. The health care provider’s job is to ask questions that will uncover these risk factors.

With the advent of a more inclusive attitude toward gay and lesbian partnership, many providers already have learned to collect the sexual history without assuming the gender of a person’s sexual contacts. Still, when a provider is taking the sexual history, gender often is inappropriately used as proxy for the type of sex that a patient may be having. For example, a provider asking a cisgender woman about her sexual activity may ask, “how many sexual partners have you had in the last year?” But then, the provider may follow-up her response of “three sexual partners in the last year” by asking “men, women, or both?” By asking a patient if the patient’s sexual partners are “men, women, or both,” providers fail to accurately elucidate the risk factors that they are actually seeking when taking a sexual history. The cisgender woman from the above scenario may reply that she has been sleeping only with women for the last year, but if the sexual partners are transgender women, aka a woman who was assigned male at birth and therefore still may use her penis/testes for sexual purposes, then the patient actually may be at risk for pregnancy and may also have a different risk factor profile for sexually transmitted infections than if the patient were sexually active with cisgender women.

A different approach to using gender in taking the sexual history is to speak plainly about which sex organs come into contact during sexual activity. When patients identify as transgender or GNC, a provider first should start by asking them what language they would like providers to use when discussing sex organs.3 One example is that many trans men, both those who have undergone mastectomy as well as those who have not, may not use the word “breasts” to describe their “chests.” This distinction may make the difference between gaining and losing the trust of a trans/GNC patient in your clinic. After identifying how a patient would like to refer to sex organs, a provider can continue by asking which of the patient’s sex partners’ organs come into contact with the patient’s organs during sexual activity. Alternatively, starting with an even more broad line of questioning may be best for some patients, such as “how do you like to have sex?”

Carefully identifying the type of sex and what sex organs are involved has concrete medical implications. Patients assigned female at birth who are on hormone therapy with testosterone may need supportive care if they continue to use their vaginas in sexual encounters because testosterone can lead to a relatively hypoestrogenic state. Patients assigned male at birth who have undergone vaginoplasty procedures may need counseling about how to use and support their neovaginas as well as adjusted testing for dysplasia. Patients assigned female at birth who want to avoid pregnancy may need a nuanced consultation regarding contraception. These are just a few examples of how obstetrician-gynecologists can better support the sexual health of their trans/GNC patients by having an accurate understanding of how a trans/GNC person has sex.

Dr. Joyner is an assistant professor at Emory University, Atlanta, and is the director of gynecologic services in the Gender Center at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta. Dr. Joyner identifies as a cisgender female and uses she/hers/her as her personal pronouns. Dr. Joey Bahng is a PGY-1 resident physician in Emory University’s gynecology & obstetrics residency program. Dr. Bahng identifies as nonbinary and uses they/them/their as their personal pronouns. Dr. Bahng and Dr. Joyner reported no relevant financial disclosures

References

1. Sexual orientation and gender identity definitions. Human Rights Campaign.

2. Taking a sexual history from transgender people. Transforming Health at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

3. Sexual health history: Talking sex with gender non-conforming and trans patients. National LGBT Health Education Center at The Fenway Institute.

Diabetes, hypertension remission more prevalent in adolescents than adults after gastric bypass

according to two related studies of 5-year outcomes after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

However, despite adolescents’ better outcomes for diabetes and hypertension, their rate of abdominal reoperations was significantly higher during the 5-year follow-up period, and at 2 years post surgery, they were found to have low ferritin levels. The rates of death were similar in the two groups at 5 years.

“We have documented similar and durable weight loss after gastric bypass in adolescents and adults, but important differences between these cohorts were observed in specific health outcomes,” wrote Thomas H. Inge, MD, PhD, of the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and his coauthors. The study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

To evaluate and compare outcomes after bariatric surgery, the researchers undertook the Teen–Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (Teen-LABS) study and the LABS study. The two were related but independent observational studies of postsurgery patient cohorts. The Teen-LABS study included 161 adolescents with severe obesity, and the LABS study included 396 adults who reported becoming obese during adolescence.

At 5-year follow-up, there was no significant difference in mean percentage weight change between adolescents (−26%; 95% confidence interval, −29 to −23) and adults (−29%; 95% CI, −31 to −27; P = .08). Adolescents were more likely than were adults to have remission of type 2 diabetes (86% vs. 53%, respectively; risk ratio, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.57; P = .03) as well as hypertension (68% vs. 41%; risk ratio, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.21 to 1.88; P less than .001).

In addition, 20% of adolescents and 16% of adults underwent intra-abdominal procedures within 5 years of surgery, with cholecystectomy being the most common, followed by surgery for bowel obstruction or hernia repair, and gastrostomy. At 2 years, ferritin levels were lower in adolescents than in adults (48% of patients vs. 29%, respectively). Five-year ferritin levels were not assessed.

In all, three adolescents (1.9%) and seven adults (1.8%) died over the 5-year period. Among the adolescents, one patient with type 1 diabetes died 3 years after surgery from complications after a hypoglycemic episode, and the other two deaths, both 4 years after surgery, were consistent with overdose. Among the adults, three of the deaths occurred within 3 weeks of surgery and were related to gastric bypass, two were of indeterminate cause (at 11 months and 5 years after surgery), one was by suicide at 3 years, and one was from colon cancer at 4 years.