User login

Lithium, valproate, and suicide risk: Analysis of 98,831 cases

The current academic psychiatry paradigm reinforces that lithium reduces suicide risk, more so than other medications, including valproate. However, data from multiple sources contradict this “evidence-based” belief.

Data do not support lithium’s supposed advantage

An 8-year prospective study in Sweden by Song et al1 tracked 51,535 patients with bipolar disorder from 2005 to 2013. In their conclusions, the authors of this study omitted some surprising numbers that contradict the dominant paradigm. There were 230 (1.089%) completed suicides in the lithium group (N = 21,129), 99 (1.177%) in the valproate group (N = 8,411), and 308 (1.195%) in the “other medication” group (N = 25,780). This difference of .088% is too small (95% CI, -.180% to .358%) to substantiate the purported advantage of lithium over valproate. More important is that in terms of suicide-related events, the medication group excluding lithium and valproate had 2,018 (7.8%) events vs lithium 2,142 (10.1%) and valproate 1,105 (13.1%). The difference of 2.3% is statistically significant (95% CI, 1.8% to 2.8%). These numbers reflect fewer suicide-related events with psychiatric medications other than lithium and valproate. Compounding the problem is a design flaw in which 3,785 patients were counted twice in the lithium and valproate groups (21,129 + 8,411 + 25,780 = 55,320, which is more than the 51,535 patients in the study). By falsely inflating the denominator (N) for the lithium and valproate groups, the respective published rates are deceptively lower than the actual rates. Song et al1 did not provide an adequate explanation for these findings and omitted them from their conclusions.

In Schatzberg’s Manual of Clinical Psychopharmacology, the authors cited Song et al1 but omitted these findings as well, and stated “lithium is clearly effective in preventing suicide attempts and completions in bipolar patients.”2 In Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology, the author wrote “lithium actually reduces suicide in patients with bipolar disorder.”3 In a review article,

In an overlapping period, National Poison Data System (NPDS) data of single substance exposures painted a different picture in the United States.6 During 2006-2013, the lithium group (N = 26,144) had 32 deaths (all causes) (.122%), and the valproate group (N = 25,630) had 16 deaths (.062%). During 2006-2020, the lithium group (N = 52,262) had 55 deaths (.105%), and the valproate group (N = 46,569) had 31 deaths (.067%). Clearly there is a major disconnect between lithium’s advertised ability to reduce suicide risk and the actual mortality rate, as evidenced by 98,831 cases reported to NPDS during 2006-2020. One would expect a lower rate in the lithium group, but data show it is higher than in the valproate group. This underscores the common fallacy of most lithium studies: each is based on a very small sample (N < 100), and the statistical inference about the entire population is tenuous. If lithium truly reduces suicide risk 5-fold, it would be seen in a sample of 98,831. The law of large numbers and central limit theorem state that as N increases, the variability of the rate progressively decreases. This can be easily demonstrated with computer simulation models and simple Python code, or on the average fuel economy display of most cars.

What about the relative lethality?

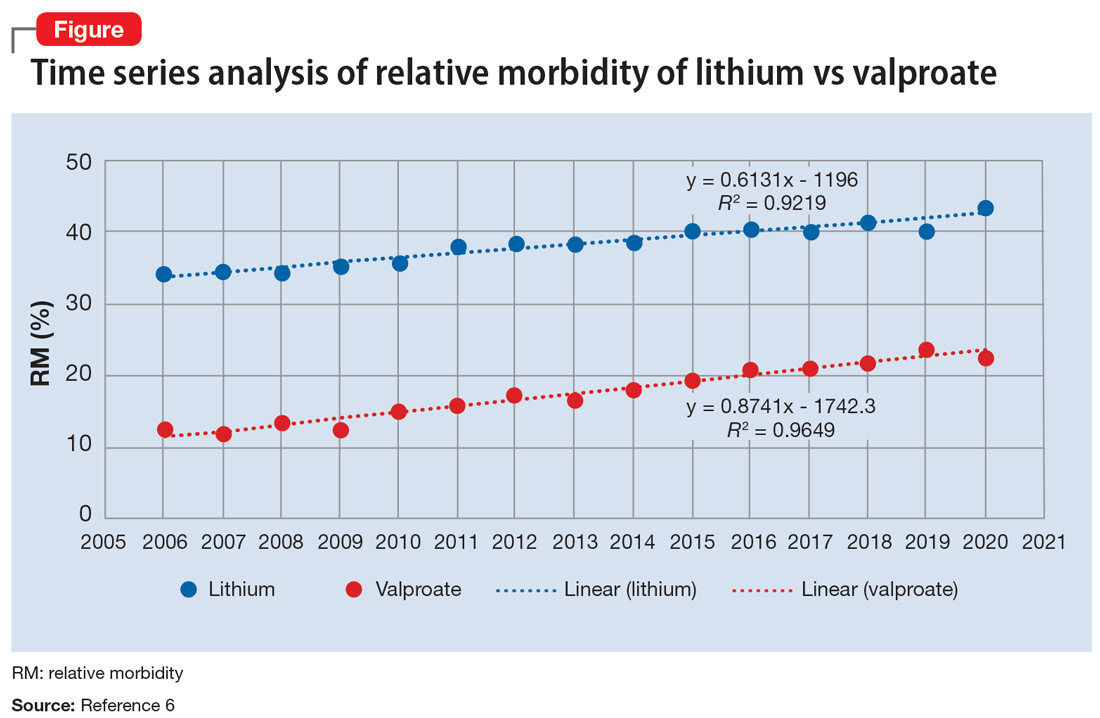

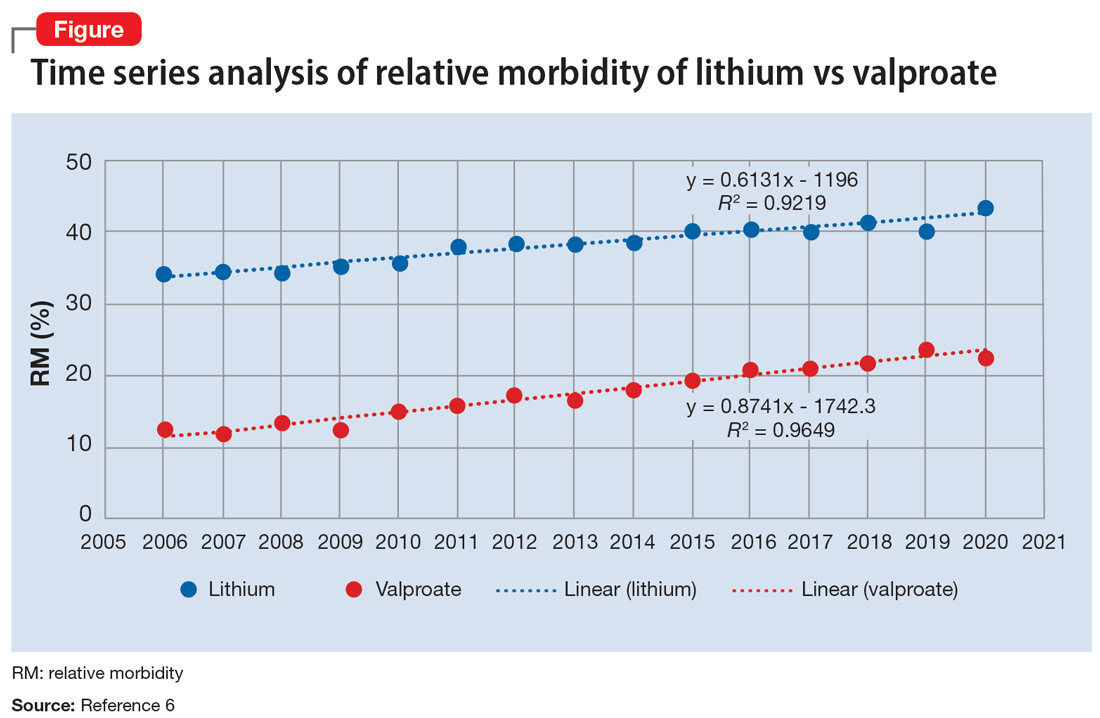

The APA Textbook of Suicide Risk Assessment and Management stated that it is important to consider the relative lethality (RL) of prescription medications.7 The RL equation (RL = 310x / LD50) represents the ratio of a 30-day supply of medication to the human equivalent LD50 for a 60-kg person (x is the daily dose and LD50 is the rat oral lethal dose 50).8 Time series analysis shows that the lithium relative morbidity (RM) is consistently double that of valproate (Figure6). Regression models have shown high correlation and causality between RL and RM.9-11 It is surprising that valproate (RL = 1,666%) has a lower RM than lithium (RL = 1,063%). This paradox can be easily explained with clinical insight. The RL equation compares medications at the maximum daily dose, but in routine practice valproate is commonly prescribed at 1,000 mg/d (28% of the maximum 3,600 mg/d). Lithium is commonly prescribed at 1,200 mg/d (67% of the maximum 1,800 mg/d). Within these dosing parameters, the effective RL is valproate 463% and lithium 709%. The 2020 RM is valproate 22% and lithium 43%.12 The COVID-19 pandemic did not affect the predicted RM. Confirming these numbers, Song et al1 acknowledged “greater safety in case of overdose for valproate in clinical practice.” Baldessarini et al4 asserted “the fatality risk of lithium overdose is only moderate, and very similar to modern antidepressants and second-generation antipsychotics.”4 This claim is contradicted by the RL equation and regression models.7-11 Lithium’s RL is 19 times higher than that of fluoxetine, and 30 times higher than that of olanzapine.8 Lithium’s RM is nearly identical to amitriptyline (42%), vs fluoxetine (12%).12

Data-driven analysis shows that lithium has higher rates of morbidity and mortality than valproate, as evidenced by 98,831 NPDS cases during 2006-2020. These hard numbers speak for themselves and contradict the dominant paradigm, which proclaims lithium’s superiority in reducing suicide risk.

1. Song J, Sjölander A, Joas E, et al. Suicidal behavior during lithium and valproate treatment: a within-individual 8-year prospective study of 50,000 patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(8):795-802.

2. Schatzberg AF, DeBattista C. Schatzberg’s Manual of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 9th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019:335.

3. Stahl SM. Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology. 4th ed. Cambridge University Press; 2013:372.

4. Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Davis P, et al. Decreased risk of suicides and attempts during long-term lithium treatment: a meta-analytic review. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(5 Pt 2):625-639.

5. Oquendo MA, Galfalvy HC, Currier D, et al. Treatment of suicide attempters with bipolar disorder: a randomized clinical trial comparing lithium and valproate in the prevention of suicidal behavior. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(10):1050-1056.

6. American Association of Poison Control Centers. Annual reports. Accessed August 25, 2022. https://aapcc.org/annual-reports

7. Gold LH, Frierson RL (eds). The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Suicide Risk Assessment and Management. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2020:17-19.

8. Giurca D. Decreasing suicide risk with math. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(2):57-59,A,B.

9. Giurca D. Data-driven prescribing. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(10):e6-e8.

10. Giurca D. Time series analysis of poison control data. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(6):e5-e9.

11. Giurca D, Hodgman MJ. Relative lethality of hypertension drugs. J Med Toxicol. 2022;18(2):81. 2022 American College of Medical Toxicology Annual Scientific Meeting abstract 020.

12. Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Beuhler MD, et al. 2020 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 38th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2021;59(12):1282-1501.

The current academic psychiatry paradigm reinforces that lithium reduces suicide risk, more so than other medications, including valproate. However, data from multiple sources contradict this “evidence-based” belief.

Data do not support lithium’s supposed advantage

An 8-year prospective study in Sweden by Song et al1 tracked 51,535 patients with bipolar disorder from 2005 to 2013. In their conclusions, the authors of this study omitted some surprising numbers that contradict the dominant paradigm. There were 230 (1.089%) completed suicides in the lithium group (N = 21,129), 99 (1.177%) in the valproate group (N = 8,411), and 308 (1.195%) in the “other medication” group (N = 25,780). This difference of .088% is too small (95% CI, -.180% to .358%) to substantiate the purported advantage of lithium over valproate. More important is that in terms of suicide-related events, the medication group excluding lithium and valproate had 2,018 (7.8%) events vs lithium 2,142 (10.1%) and valproate 1,105 (13.1%). The difference of 2.3% is statistically significant (95% CI, 1.8% to 2.8%). These numbers reflect fewer suicide-related events with psychiatric medications other than lithium and valproate. Compounding the problem is a design flaw in which 3,785 patients were counted twice in the lithium and valproate groups (21,129 + 8,411 + 25,780 = 55,320, which is more than the 51,535 patients in the study). By falsely inflating the denominator (N) for the lithium and valproate groups, the respective published rates are deceptively lower than the actual rates. Song et al1 did not provide an adequate explanation for these findings and omitted them from their conclusions.

In Schatzberg’s Manual of Clinical Psychopharmacology, the authors cited Song et al1 but omitted these findings as well, and stated “lithium is clearly effective in preventing suicide attempts and completions in bipolar patients.”2 In Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology, the author wrote “lithium actually reduces suicide in patients with bipolar disorder.”3 In a review article,

In an overlapping period, National Poison Data System (NPDS) data of single substance exposures painted a different picture in the United States.6 During 2006-2013, the lithium group (N = 26,144) had 32 deaths (all causes) (.122%), and the valproate group (N = 25,630) had 16 deaths (.062%). During 2006-2020, the lithium group (N = 52,262) had 55 deaths (.105%), and the valproate group (N = 46,569) had 31 deaths (.067%). Clearly there is a major disconnect between lithium’s advertised ability to reduce suicide risk and the actual mortality rate, as evidenced by 98,831 cases reported to NPDS during 2006-2020. One would expect a lower rate in the lithium group, but data show it is higher than in the valproate group. This underscores the common fallacy of most lithium studies: each is based on a very small sample (N < 100), and the statistical inference about the entire population is tenuous. If lithium truly reduces suicide risk 5-fold, it would be seen in a sample of 98,831. The law of large numbers and central limit theorem state that as N increases, the variability of the rate progressively decreases. This can be easily demonstrated with computer simulation models and simple Python code, or on the average fuel economy display of most cars.

What about the relative lethality?

The APA Textbook of Suicide Risk Assessment and Management stated that it is important to consider the relative lethality (RL) of prescription medications.7 The RL equation (RL = 310x / LD50) represents the ratio of a 30-day supply of medication to the human equivalent LD50 for a 60-kg person (x is the daily dose and LD50 is the rat oral lethal dose 50).8 Time series analysis shows that the lithium relative morbidity (RM) is consistently double that of valproate (Figure6). Regression models have shown high correlation and causality between RL and RM.9-11 It is surprising that valproate (RL = 1,666%) has a lower RM than lithium (RL = 1,063%). This paradox can be easily explained with clinical insight. The RL equation compares medications at the maximum daily dose, but in routine practice valproate is commonly prescribed at 1,000 mg/d (28% of the maximum 3,600 mg/d). Lithium is commonly prescribed at 1,200 mg/d (67% of the maximum 1,800 mg/d). Within these dosing parameters, the effective RL is valproate 463% and lithium 709%. The 2020 RM is valproate 22% and lithium 43%.12 The COVID-19 pandemic did not affect the predicted RM. Confirming these numbers, Song et al1 acknowledged “greater safety in case of overdose for valproate in clinical practice.” Baldessarini et al4 asserted “the fatality risk of lithium overdose is only moderate, and very similar to modern antidepressants and second-generation antipsychotics.”4 This claim is contradicted by the RL equation and regression models.7-11 Lithium’s RL is 19 times higher than that of fluoxetine, and 30 times higher than that of olanzapine.8 Lithium’s RM is nearly identical to amitriptyline (42%), vs fluoxetine (12%).12

Data-driven analysis shows that lithium has higher rates of morbidity and mortality than valproate, as evidenced by 98,831 NPDS cases during 2006-2020. These hard numbers speak for themselves and contradict the dominant paradigm, which proclaims lithium’s superiority in reducing suicide risk.

The current academic psychiatry paradigm reinforces that lithium reduces suicide risk, more so than other medications, including valproate. However, data from multiple sources contradict this “evidence-based” belief.

Data do not support lithium’s supposed advantage

An 8-year prospective study in Sweden by Song et al1 tracked 51,535 patients with bipolar disorder from 2005 to 2013. In their conclusions, the authors of this study omitted some surprising numbers that contradict the dominant paradigm. There were 230 (1.089%) completed suicides in the lithium group (N = 21,129), 99 (1.177%) in the valproate group (N = 8,411), and 308 (1.195%) in the “other medication” group (N = 25,780). This difference of .088% is too small (95% CI, -.180% to .358%) to substantiate the purported advantage of lithium over valproate. More important is that in terms of suicide-related events, the medication group excluding lithium and valproate had 2,018 (7.8%) events vs lithium 2,142 (10.1%) and valproate 1,105 (13.1%). The difference of 2.3% is statistically significant (95% CI, 1.8% to 2.8%). These numbers reflect fewer suicide-related events with psychiatric medications other than lithium and valproate. Compounding the problem is a design flaw in which 3,785 patients were counted twice in the lithium and valproate groups (21,129 + 8,411 + 25,780 = 55,320, which is more than the 51,535 patients in the study). By falsely inflating the denominator (N) for the lithium and valproate groups, the respective published rates are deceptively lower than the actual rates. Song et al1 did not provide an adequate explanation for these findings and omitted them from their conclusions.

In Schatzberg’s Manual of Clinical Psychopharmacology, the authors cited Song et al1 but omitted these findings as well, and stated “lithium is clearly effective in preventing suicide attempts and completions in bipolar patients.”2 In Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology, the author wrote “lithium actually reduces suicide in patients with bipolar disorder.”3 In a review article,

In an overlapping period, National Poison Data System (NPDS) data of single substance exposures painted a different picture in the United States.6 During 2006-2013, the lithium group (N = 26,144) had 32 deaths (all causes) (.122%), and the valproate group (N = 25,630) had 16 deaths (.062%). During 2006-2020, the lithium group (N = 52,262) had 55 deaths (.105%), and the valproate group (N = 46,569) had 31 deaths (.067%). Clearly there is a major disconnect between lithium’s advertised ability to reduce suicide risk and the actual mortality rate, as evidenced by 98,831 cases reported to NPDS during 2006-2020. One would expect a lower rate in the lithium group, but data show it is higher than in the valproate group. This underscores the common fallacy of most lithium studies: each is based on a very small sample (N < 100), and the statistical inference about the entire population is tenuous. If lithium truly reduces suicide risk 5-fold, it would be seen in a sample of 98,831. The law of large numbers and central limit theorem state that as N increases, the variability of the rate progressively decreases. This can be easily demonstrated with computer simulation models and simple Python code, or on the average fuel economy display of most cars.

What about the relative lethality?

The APA Textbook of Suicide Risk Assessment and Management stated that it is important to consider the relative lethality (RL) of prescription medications.7 The RL equation (RL = 310x / LD50) represents the ratio of a 30-day supply of medication to the human equivalent LD50 for a 60-kg person (x is the daily dose and LD50 is the rat oral lethal dose 50).8 Time series analysis shows that the lithium relative morbidity (RM) is consistently double that of valproate (Figure6). Regression models have shown high correlation and causality between RL and RM.9-11 It is surprising that valproate (RL = 1,666%) has a lower RM than lithium (RL = 1,063%). This paradox can be easily explained with clinical insight. The RL equation compares medications at the maximum daily dose, but in routine practice valproate is commonly prescribed at 1,000 mg/d (28% of the maximum 3,600 mg/d). Lithium is commonly prescribed at 1,200 mg/d (67% of the maximum 1,800 mg/d). Within these dosing parameters, the effective RL is valproate 463% and lithium 709%. The 2020 RM is valproate 22% and lithium 43%.12 The COVID-19 pandemic did not affect the predicted RM. Confirming these numbers, Song et al1 acknowledged “greater safety in case of overdose for valproate in clinical practice.” Baldessarini et al4 asserted “the fatality risk of lithium overdose is only moderate, and very similar to modern antidepressants and second-generation antipsychotics.”4 This claim is contradicted by the RL equation and regression models.7-11 Lithium’s RL is 19 times higher than that of fluoxetine, and 30 times higher than that of olanzapine.8 Lithium’s RM is nearly identical to amitriptyline (42%), vs fluoxetine (12%).12

Data-driven analysis shows that lithium has higher rates of morbidity and mortality than valproate, as evidenced by 98,831 NPDS cases during 2006-2020. These hard numbers speak for themselves and contradict the dominant paradigm, which proclaims lithium’s superiority in reducing suicide risk.

1. Song J, Sjölander A, Joas E, et al. Suicidal behavior during lithium and valproate treatment: a within-individual 8-year prospective study of 50,000 patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(8):795-802.

2. Schatzberg AF, DeBattista C. Schatzberg’s Manual of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 9th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019:335.

3. Stahl SM. Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology. 4th ed. Cambridge University Press; 2013:372.

4. Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Davis P, et al. Decreased risk of suicides and attempts during long-term lithium treatment: a meta-analytic review. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(5 Pt 2):625-639.

5. Oquendo MA, Galfalvy HC, Currier D, et al. Treatment of suicide attempters with bipolar disorder: a randomized clinical trial comparing lithium and valproate in the prevention of suicidal behavior. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(10):1050-1056.

6. American Association of Poison Control Centers. Annual reports. Accessed August 25, 2022. https://aapcc.org/annual-reports

7. Gold LH, Frierson RL (eds). The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Suicide Risk Assessment and Management. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2020:17-19.

8. Giurca D. Decreasing suicide risk with math. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(2):57-59,A,B.

9. Giurca D. Data-driven prescribing. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(10):e6-e8.

10. Giurca D. Time series analysis of poison control data. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(6):e5-e9.

11. Giurca D, Hodgman MJ. Relative lethality of hypertension drugs. J Med Toxicol. 2022;18(2):81. 2022 American College of Medical Toxicology Annual Scientific Meeting abstract 020.

12. Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Beuhler MD, et al. 2020 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 38th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2021;59(12):1282-1501.

1. Song J, Sjölander A, Joas E, et al. Suicidal behavior during lithium and valproate treatment: a within-individual 8-year prospective study of 50,000 patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(8):795-802.

2. Schatzberg AF, DeBattista C. Schatzberg’s Manual of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 9th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019:335.

3. Stahl SM. Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology. 4th ed. Cambridge University Press; 2013:372.

4. Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Davis P, et al. Decreased risk of suicides and attempts during long-term lithium treatment: a meta-analytic review. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(5 Pt 2):625-639.

5. Oquendo MA, Galfalvy HC, Currier D, et al. Treatment of suicide attempters with bipolar disorder: a randomized clinical trial comparing lithium and valproate in the prevention of suicidal behavior. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(10):1050-1056.

6. American Association of Poison Control Centers. Annual reports. Accessed August 25, 2022. https://aapcc.org/annual-reports

7. Gold LH, Frierson RL (eds). The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Suicide Risk Assessment and Management. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2020:17-19.

8. Giurca D. Decreasing suicide risk with math. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(2):57-59,A,B.

9. Giurca D. Data-driven prescribing. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(10):e6-e8.

10. Giurca D. Time series analysis of poison control data. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(6):e5-e9.

11. Giurca D, Hodgman MJ. Relative lethality of hypertension drugs. J Med Toxicol. 2022;18(2):81. 2022 American College of Medical Toxicology Annual Scientific Meeting abstract 020.

12. Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Beuhler MD, et al. 2020 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 38th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2021;59(12):1282-1501.

Hold or not to hold: Navigating involuntary commitment

CASE Depressed and suicidal

Police arrive at the home of Mr. H, age 50, after his wife calls 911. She reports he has depression and she saw him in bed brandishing a firearm as if he wanted to hurt himself. Upon arrival, the officers enter the house and find Mr. H in bed without a firearm. Mr. H says little to the officers about the alleged events, but acknowledges he has depression and is willing to go the hospital for further evaluation. Neither his wife nor the officers locate a firearm in the home.

EVALUATION Emergency detention

In the emergency department (ED), Mr. H’s laboratory results and physical examination findings are normal. He acknowledges feeling depressed over the past 2 weeks. Though he cannot identify any precipitants, he says he has experienced anhedonia, lack of appetite, decreased energy, and changes in his sleep patterns. When asked about the day’s events concerning the firearm, Mr. H becomes guarded and does not give a clear answer regarding having thoughts of suicide.

The evaluating psychiatrist obtains collateral from Mr. H’s wife and reviews his medical records. There are no active prescriptions on file and the psychiatrist notices that last year there was a suicide attempt involving a firearm. Following that episode, Mr. H was hospitalized, treated with sertraline 50 mg/d, and discharged with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. There was no legal or substance abuse history.

In the ED, the psychiatrist conducts a psychiatric evaluation, including a suicide risk assessment, and determines Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life. Mr. H’s psychiatrist explains there are 2 treatment options: to be admitted to the hospital or to be discharged. The psychiatrist recommends hospital admission to Mr. H for his safety and stabilization. Mr. H says he prefers to return home.

Because the psychiatrist believes Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life and there is no less restrictive setting for treatment, he implements an emergency detention. In Ohio, this allows Mr. H to be held in the hospital for no more than 3 court days in accordance with state law. Before Mr. H’s emergency detention periods ends, the psychiatrist will need to decide whether Mr. H can be safely discharged. If the psychiatrist determines that Mr. H still needs treatment, the court will be petitioned for a civil commitment hearing.

[polldaddy:11189291]

The author’s observations

In some cases, courts allow information a psychiatrist does not directly obtain from a patient to be admitted as testimony in a civil commitment hearing. However, some jurisdictions consider sources of information not obtained directly from the patient as hearsay and thus inadmissible.1 Though each source listed may provide credible information that could be presented at a hearing, the psychiatrist should discuss with the patient the information obtained from these sources to ensure it is admissable.2 A discussion with Mr. H about the factors that led to his hospital arrival will avoid the psychiatrist’s reliance on what another person has heard or seen when providing testimony. Even when a psychiatrist is not faced with an issue of admissibility, caution must be taken with third-party reports.3

TREATMENT Civil commitment hearing

Before the emergency detention period expires, Mr. H’s psychiatrist determines that he remains at imminent risk of self-harm. To continue hospitalization, the psychiatrist files a petition for civil commitment and testifies at the commitment hearing. He reports that Mr. H suffers from a substantial mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The psychiatrist also testifies that the least restrictive environment for treatment continues to be inpatient hospitalization, because Mr. H is still at imminent risk of harming himself.

Continue to: Following the psychiatrist's...

Following the psychiatrist’s testimony, the magistrate finds that Mr. H is a mentally ill person subject to hospitalization given his mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The magistrate orders that Mr. H be civilly committed to the hospital.

[polldaddy:11189293]

The author’s observations

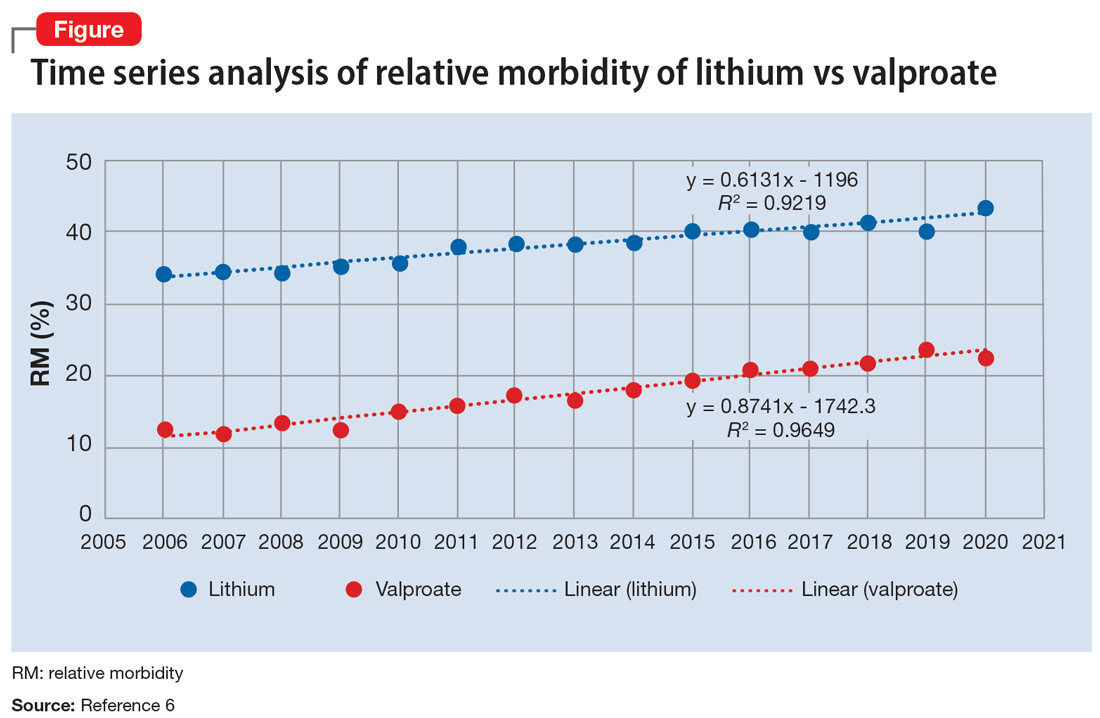

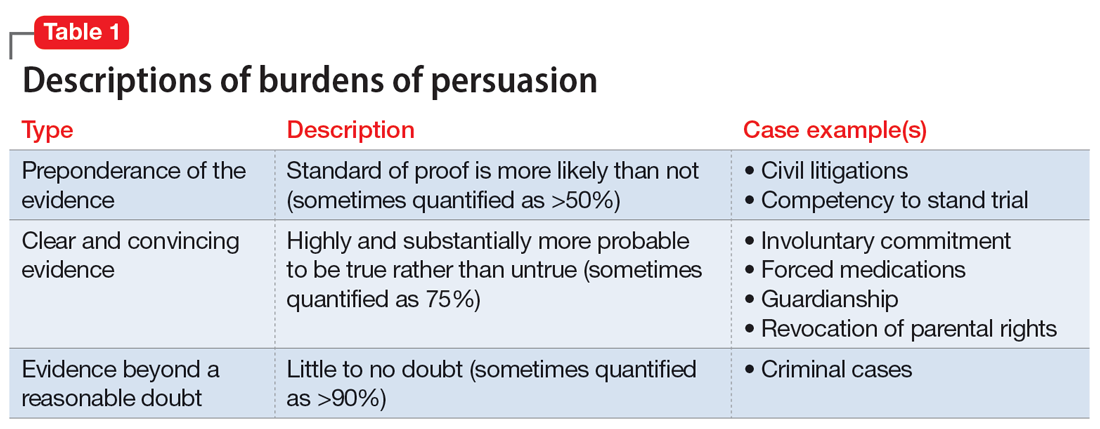

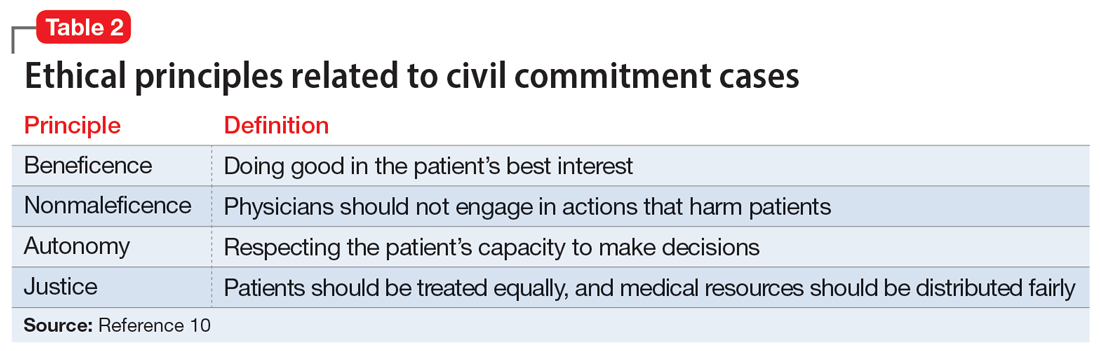

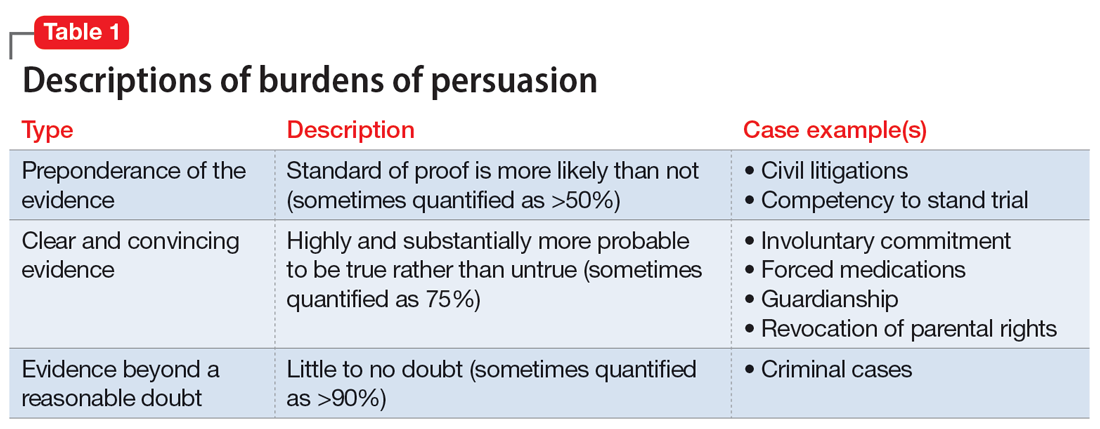

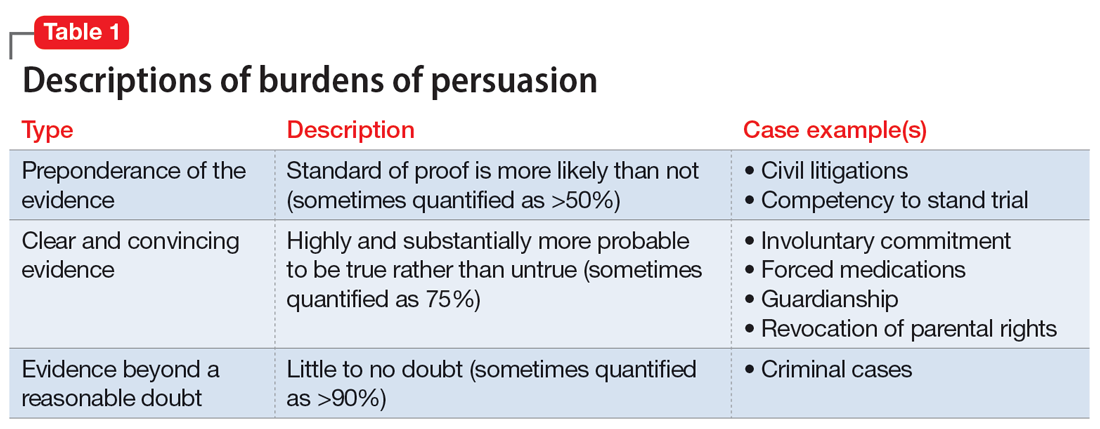

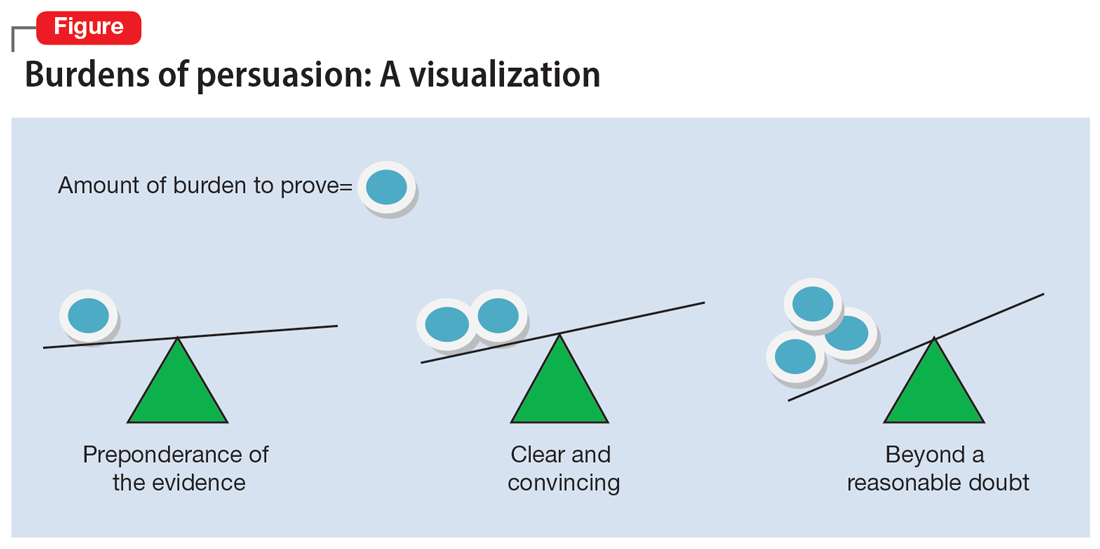

The psychiatrist’s testimony mirrors the language regarding civil commitment in the Ohio Revised Code.4 Other elements considered for mental illness in Ohio are a substantial disorder of memory, thought, orientation, or perception that grossly impairs one’s capacity to recognize reality or meet the demands of life.4 The definition of what constitutes a mental disorder varies by state, but the burden of persuasion—the standard by which the court must be convinced—is generally uniform.5 In the 1979 case Addington v Texas, the United States Supreme Court concluded that in a civil commitment hearing, the minimum standard of proof for involuntary commitment must be clear and convincing evidence.6 Neither medical certainty nor substantial probability are burdens of persuasions.6 Instead, these terms may be presented in a forensic report when an examiner outlines their opinion. Table 1 and the Figure provide more detail on burdens of persuasion.

TREATMENT Civil commitment and patient rights

At a regularly scheduled treatment team meeting, the team informs Mr. H that he has been civilly committed for further treatment. Mr. H becomes upset and tells the team the decision is a complete violation of his rights. After a long rant, Mr. H walks out of the room, saying, “I did not even know when this hearing was.” A member of the treatment team becomes concerned that Mr. H may not have been notified of the hearing.

[polldaddy:11189294]

The author’s observations

It is not clear if Mr. H had been notified of his civil commitment hearing. If Mr. H had not been notified, his rights would have been compromised. Lessard v Schmidt (1972) outlined that individuals involved in a civil commitment hearing should be afforded the same rights as those involved in criminal proceedings.7 Mr. H should have been notified of his hearing and afforded the opportunity to have the assignment of counsel, the right to appear, the right to testify, the right to present witnesses and other evidence, and the right to confront witnesses.

Without notification of the hearing, the only right that would have remained intact for Mr. H would have been the assignment of counsel in his absence and without his knowledge. If Mr. H had been notified of the hearing and did not want to attend, yet still desired legal counsel, he could have waived his presence voluntarily after discussing this option with his attorney.8,9

Continue to: OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

During his 10-day stay, Mr. H is treated with sertraline 50 mg/d and engages in individual and group therapy. He shows noticeable improvement in his depressive symptoms and reports having no thoughts of suicide or self-harm. The treatment team determines it is appropriate to discharge him home (the firearm was never found) and involves his wife in safety planning and follow-up care. On the day of his discharge, Mr. H reflects on his treatment and civil commitment. He says, “I did not know a judge could order me to be hospitalized.”

[polldaddy:11189297]

The author’s observations

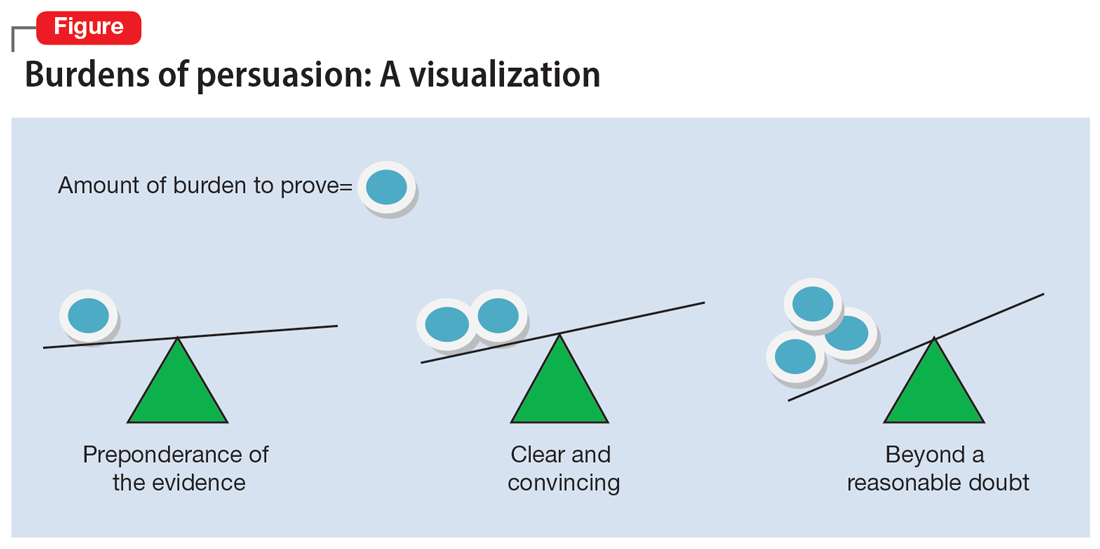

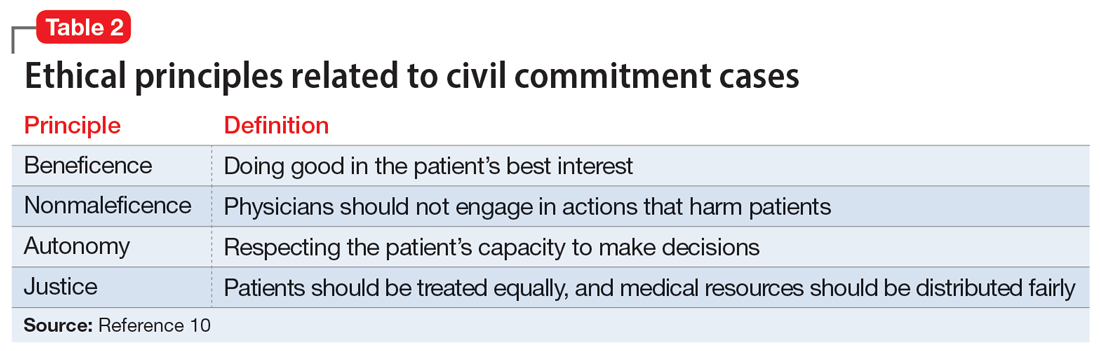

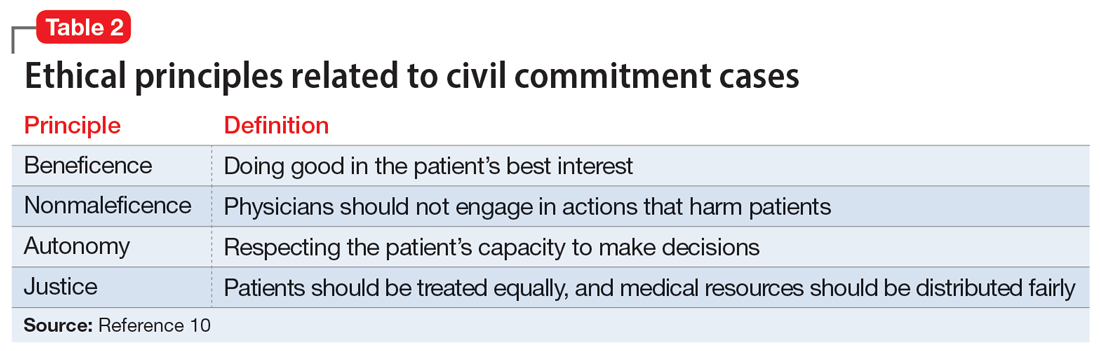

The physician’s decision to pursue civil commitment is best described by the legal doctrines of police powers and parens patriae. Other relevant ethical principles are described in Table 2.10

Though ethical principles may play a role in civil commitment, parens patriae and police powers is the answer with respect to the State.11Parens patriae is Latin for the “parent of the country” and grants the State the power to protect those residents who are most vulnerable. Police power is the authority of the State to enact and enforce rules that limit the rights of individuals for the greater good of ensuring health, safety, and welfare of all citizens.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists are entrusted with recognizing when a patient, due to mental illness, is a danger to themselves or others and in need of treatment. After an emergency detention period, if the patient remains a danger to themselves or others and does not want to voluntarily receive treatment, a court hearing is required. As an expert witness, the treating psychiatrist should know the factors of law in their jurisdiction that determine civil commitment.

Related Resources

- Extreme Risk Protection Orders. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. https://www.jhsph.edu/research/ centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-center-for-gun-violenceprevention-and-policy/research/extreme-risk-protectionorders/

- Gutheil TG. The Psychiatrist as Expert Witness. 2nd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2009.

- Landmark Cases 2014. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. https://www.aapl.org/landmark-cases

Drug Brand Names

Sertraline • Zoloft

1. Pinals DA, Mossman D. Evaluation for Civil Commitment. Oxford University Press; 2012.

2. Thatcher BT, Mossman D. Testifying for civil commitment: help unwilling patients get the treatment they need. Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(11):51-56.

3. Marett CP, Mossman D. What is your liability for involuntary commitment based on faulty information? Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):21-25,33.

4. Ohio Rev Code § 5122.01 (2018).

5. The Burden of Proof. University of Minnesota. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://open.lib.umn.edu/criminallaw/chapter/2-4-the-burden-of-proof/

6. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Forensic Psychiatry. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018.

7. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Suicide Assessment and Management. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2020.

8. Cook J. Good lawyering and bad role models: the role of respondent’s counsel in a civil commitment hearing. Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics. 2000;14(1):179-195.

9. Ferris CE. The search for due process in civil commitment hearings: how procedural realities have altered substantive standards. Vanderbilt Law Rev. 2008;61(3):959-981.

10. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Civil Commitment and the Mental Health Care Continuum: Historical Trends and Principles for Law and Practice. 2019. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/ebp/civil-commitment-mental-health-care-continuum-historical-trends-principles-law

11. Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological Evaluations for the Courts: A Handbook for Mental Health Profession. 4th ed. Guilford Press; 2018.

CASE Depressed and suicidal

Police arrive at the home of Mr. H, age 50, after his wife calls 911. She reports he has depression and she saw him in bed brandishing a firearm as if he wanted to hurt himself. Upon arrival, the officers enter the house and find Mr. H in bed without a firearm. Mr. H says little to the officers about the alleged events, but acknowledges he has depression and is willing to go the hospital for further evaluation. Neither his wife nor the officers locate a firearm in the home.

EVALUATION Emergency detention

In the emergency department (ED), Mr. H’s laboratory results and physical examination findings are normal. He acknowledges feeling depressed over the past 2 weeks. Though he cannot identify any precipitants, he says he has experienced anhedonia, lack of appetite, decreased energy, and changes in his sleep patterns. When asked about the day’s events concerning the firearm, Mr. H becomes guarded and does not give a clear answer regarding having thoughts of suicide.

The evaluating psychiatrist obtains collateral from Mr. H’s wife and reviews his medical records. There are no active prescriptions on file and the psychiatrist notices that last year there was a suicide attempt involving a firearm. Following that episode, Mr. H was hospitalized, treated with sertraline 50 mg/d, and discharged with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. There was no legal or substance abuse history.

In the ED, the psychiatrist conducts a psychiatric evaluation, including a suicide risk assessment, and determines Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life. Mr. H’s psychiatrist explains there are 2 treatment options: to be admitted to the hospital or to be discharged. The psychiatrist recommends hospital admission to Mr. H for his safety and stabilization. Mr. H says he prefers to return home.

Because the psychiatrist believes Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life and there is no less restrictive setting for treatment, he implements an emergency detention. In Ohio, this allows Mr. H to be held in the hospital for no more than 3 court days in accordance with state law. Before Mr. H’s emergency detention periods ends, the psychiatrist will need to decide whether Mr. H can be safely discharged. If the psychiatrist determines that Mr. H still needs treatment, the court will be petitioned for a civil commitment hearing.

[polldaddy:11189291]

The author’s observations

In some cases, courts allow information a psychiatrist does not directly obtain from a patient to be admitted as testimony in a civil commitment hearing. However, some jurisdictions consider sources of information not obtained directly from the patient as hearsay and thus inadmissible.1 Though each source listed may provide credible information that could be presented at a hearing, the psychiatrist should discuss with the patient the information obtained from these sources to ensure it is admissable.2 A discussion with Mr. H about the factors that led to his hospital arrival will avoid the psychiatrist’s reliance on what another person has heard or seen when providing testimony. Even when a psychiatrist is not faced with an issue of admissibility, caution must be taken with third-party reports.3

TREATMENT Civil commitment hearing

Before the emergency detention period expires, Mr. H’s psychiatrist determines that he remains at imminent risk of self-harm. To continue hospitalization, the psychiatrist files a petition for civil commitment and testifies at the commitment hearing. He reports that Mr. H suffers from a substantial mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The psychiatrist also testifies that the least restrictive environment for treatment continues to be inpatient hospitalization, because Mr. H is still at imminent risk of harming himself.

Continue to: Following the psychiatrist's...

Following the psychiatrist’s testimony, the magistrate finds that Mr. H is a mentally ill person subject to hospitalization given his mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The magistrate orders that Mr. H be civilly committed to the hospital.

[polldaddy:11189293]

The author’s observations

The psychiatrist’s testimony mirrors the language regarding civil commitment in the Ohio Revised Code.4 Other elements considered for mental illness in Ohio are a substantial disorder of memory, thought, orientation, or perception that grossly impairs one’s capacity to recognize reality or meet the demands of life.4 The definition of what constitutes a mental disorder varies by state, but the burden of persuasion—the standard by which the court must be convinced—is generally uniform.5 In the 1979 case Addington v Texas, the United States Supreme Court concluded that in a civil commitment hearing, the minimum standard of proof for involuntary commitment must be clear and convincing evidence.6 Neither medical certainty nor substantial probability are burdens of persuasions.6 Instead, these terms may be presented in a forensic report when an examiner outlines their opinion. Table 1 and the Figure provide more detail on burdens of persuasion.

TREATMENT Civil commitment and patient rights

At a regularly scheduled treatment team meeting, the team informs Mr. H that he has been civilly committed for further treatment. Mr. H becomes upset and tells the team the decision is a complete violation of his rights. After a long rant, Mr. H walks out of the room, saying, “I did not even know when this hearing was.” A member of the treatment team becomes concerned that Mr. H may not have been notified of the hearing.

[polldaddy:11189294]

The author’s observations

It is not clear if Mr. H had been notified of his civil commitment hearing. If Mr. H had not been notified, his rights would have been compromised. Lessard v Schmidt (1972) outlined that individuals involved in a civil commitment hearing should be afforded the same rights as those involved in criminal proceedings.7 Mr. H should have been notified of his hearing and afforded the opportunity to have the assignment of counsel, the right to appear, the right to testify, the right to present witnesses and other evidence, and the right to confront witnesses.

Without notification of the hearing, the only right that would have remained intact for Mr. H would have been the assignment of counsel in his absence and without his knowledge. If Mr. H had been notified of the hearing and did not want to attend, yet still desired legal counsel, he could have waived his presence voluntarily after discussing this option with his attorney.8,9

Continue to: OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

During his 10-day stay, Mr. H is treated with sertraline 50 mg/d and engages in individual and group therapy. He shows noticeable improvement in his depressive symptoms and reports having no thoughts of suicide or self-harm. The treatment team determines it is appropriate to discharge him home (the firearm was never found) and involves his wife in safety planning and follow-up care. On the day of his discharge, Mr. H reflects on his treatment and civil commitment. He says, “I did not know a judge could order me to be hospitalized.”

[polldaddy:11189297]

The author’s observations

The physician’s decision to pursue civil commitment is best described by the legal doctrines of police powers and parens patriae. Other relevant ethical principles are described in Table 2.10

Though ethical principles may play a role in civil commitment, parens patriae and police powers is the answer with respect to the State.11Parens patriae is Latin for the “parent of the country” and grants the State the power to protect those residents who are most vulnerable. Police power is the authority of the State to enact and enforce rules that limit the rights of individuals for the greater good of ensuring health, safety, and welfare of all citizens.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists are entrusted with recognizing when a patient, due to mental illness, is a danger to themselves or others and in need of treatment. After an emergency detention period, if the patient remains a danger to themselves or others and does not want to voluntarily receive treatment, a court hearing is required. As an expert witness, the treating psychiatrist should know the factors of law in their jurisdiction that determine civil commitment.

Related Resources

- Extreme Risk Protection Orders. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. https://www.jhsph.edu/research/ centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-center-for-gun-violenceprevention-and-policy/research/extreme-risk-protectionorders/

- Gutheil TG. The Psychiatrist as Expert Witness. 2nd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2009.

- Landmark Cases 2014. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. https://www.aapl.org/landmark-cases

Drug Brand Names

Sertraline • Zoloft

CASE Depressed and suicidal

Police arrive at the home of Mr. H, age 50, after his wife calls 911. She reports he has depression and she saw him in bed brandishing a firearm as if he wanted to hurt himself. Upon arrival, the officers enter the house and find Mr. H in bed without a firearm. Mr. H says little to the officers about the alleged events, but acknowledges he has depression and is willing to go the hospital for further evaluation. Neither his wife nor the officers locate a firearm in the home.

EVALUATION Emergency detention

In the emergency department (ED), Mr. H’s laboratory results and physical examination findings are normal. He acknowledges feeling depressed over the past 2 weeks. Though he cannot identify any precipitants, he says he has experienced anhedonia, lack of appetite, decreased energy, and changes in his sleep patterns. When asked about the day’s events concerning the firearm, Mr. H becomes guarded and does not give a clear answer regarding having thoughts of suicide.

The evaluating psychiatrist obtains collateral from Mr. H’s wife and reviews his medical records. There are no active prescriptions on file and the psychiatrist notices that last year there was a suicide attempt involving a firearm. Following that episode, Mr. H was hospitalized, treated with sertraline 50 mg/d, and discharged with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. There was no legal or substance abuse history.

In the ED, the psychiatrist conducts a psychiatric evaluation, including a suicide risk assessment, and determines Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life. Mr. H’s psychiatrist explains there are 2 treatment options: to be admitted to the hospital or to be discharged. The psychiatrist recommends hospital admission to Mr. H for his safety and stabilization. Mr. H says he prefers to return home.

Because the psychiatrist believes Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life and there is no less restrictive setting for treatment, he implements an emergency detention. In Ohio, this allows Mr. H to be held in the hospital for no more than 3 court days in accordance with state law. Before Mr. H’s emergency detention periods ends, the psychiatrist will need to decide whether Mr. H can be safely discharged. If the psychiatrist determines that Mr. H still needs treatment, the court will be petitioned for a civil commitment hearing.

[polldaddy:11189291]

The author’s observations

In some cases, courts allow information a psychiatrist does not directly obtain from a patient to be admitted as testimony in a civil commitment hearing. However, some jurisdictions consider sources of information not obtained directly from the patient as hearsay and thus inadmissible.1 Though each source listed may provide credible information that could be presented at a hearing, the psychiatrist should discuss with the patient the information obtained from these sources to ensure it is admissable.2 A discussion with Mr. H about the factors that led to his hospital arrival will avoid the psychiatrist’s reliance on what another person has heard or seen when providing testimony. Even when a psychiatrist is not faced with an issue of admissibility, caution must be taken with third-party reports.3

TREATMENT Civil commitment hearing

Before the emergency detention period expires, Mr. H’s psychiatrist determines that he remains at imminent risk of self-harm. To continue hospitalization, the psychiatrist files a petition for civil commitment and testifies at the commitment hearing. He reports that Mr. H suffers from a substantial mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The psychiatrist also testifies that the least restrictive environment for treatment continues to be inpatient hospitalization, because Mr. H is still at imminent risk of harming himself.

Continue to: Following the psychiatrist's...

Following the psychiatrist’s testimony, the magistrate finds that Mr. H is a mentally ill person subject to hospitalization given his mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The magistrate orders that Mr. H be civilly committed to the hospital.

[polldaddy:11189293]

The author’s observations

The psychiatrist’s testimony mirrors the language regarding civil commitment in the Ohio Revised Code.4 Other elements considered for mental illness in Ohio are a substantial disorder of memory, thought, orientation, or perception that grossly impairs one’s capacity to recognize reality or meet the demands of life.4 The definition of what constitutes a mental disorder varies by state, but the burden of persuasion—the standard by which the court must be convinced—is generally uniform.5 In the 1979 case Addington v Texas, the United States Supreme Court concluded that in a civil commitment hearing, the minimum standard of proof for involuntary commitment must be clear and convincing evidence.6 Neither medical certainty nor substantial probability are burdens of persuasions.6 Instead, these terms may be presented in a forensic report when an examiner outlines their opinion. Table 1 and the Figure provide more detail on burdens of persuasion.

TREATMENT Civil commitment and patient rights

At a regularly scheduled treatment team meeting, the team informs Mr. H that he has been civilly committed for further treatment. Mr. H becomes upset and tells the team the decision is a complete violation of his rights. After a long rant, Mr. H walks out of the room, saying, “I did not even know when this hearing was.” A member of the treatment team becomes concerned that Mr. H may not have been notified of the hearing.

[polldaddy:11189294]

The author’s observations

It is not clear if Mr. H had been notified of his civil commitment hearing. If Mr. H had not been notified, his rights would have been compromised. Lessard v Schmidt (1972) outlined that individuals involved in a civil commitment hearing should be afforded the same rights as those involved in criminal proceedings.7 Mr. H should have been notified of his hearing and afforded the opportunity to have the assignment of counsel, the right to appear, the right to testify, the right to present witnesses and other evidence, and the right to confront witnesses.

Without notification of the hearing, the only right that would have remained intact for Mr. H would have been the assignment of counsel in his absence and without his knowledge. If Mr. H had been notified of the hearing and did not want to attend, yet still desired legal counsel, he could have waived his presence voluntarily after discussing this option with his attorney.8,9

Continue to: OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

During his 10-day stay, Mr. H is treated with sertraline 50 mg/d and engages in individual and group therapy. He shows noticeable improvement in his depressive symptoms and reports having no thoughts of suicide or self-harm. The treatment team determines it is appropriate to discharge him home (the firearm was never found) and involves his wife in safety planning and follow-up care. On the day of his discharge, Mr. H reflects on his treatment and civil commitment. He says, “I did not know a judge could order me to be hospitalized.”

[polldaddy:11189297]

The author’s observations

The physician’s decision to pursue civil commitment is best described by the legal doctrines of police powers and parens patriae. Other relevant ethical principles are described in Table 2.10

Though ethical principles may play a role in civil commitment, parens patriae and police powers is the answer with respect to the State.11Parens patriae is Latin for the “parent of the country” and grants the State the power to protect those residents who are most vulnerable. Police power is the authority of the State to enact and enforce rules that limit the rights of individuals for the greater good of ensuring health, safety, and welfare of all citizens.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists are entrusted with recognizing when a patient, due to mental illness, is a danger to themselves or others and in need of treatment. After an emergency detention period, if the patient remains a danger to themselves or others and does not want to voluntarily receive treatment, a court hearing is required. As an expert witness, the treating psychiatrist should know the factors of law in their jurisdiction that determine civil commitment.

Related Resources

- Extreme Risk Protection Orders. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. https://www.jhsph.edu/research/ centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-center-for-gun-violenceprevention-and-policy/research/extreme-risk-protectionorders/

- Gutheil TG. The Psychiatrist as Expert Witness. 2nd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2009.

- Landmark Cases 2014. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. https://www.aapl.org/landmark-cases

Drug Brand Names

Sertraline • Zoloft

1. Pinals DA, Mossman D. Evaluation for Civil Commitment. Oxford University Press; 2012.

2. Thatcher BT, Mossman D. Testifying for civil commitment: help unwilling patients get the treatment they need. Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(11):51-56.

3. Marett CP, Mossman D. What is your liability for involuntary commitment based on faulty information? Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):21-25,33.

4. Ohio Rev Code § 5122.01 (2018).

5. The Burden of Proof. University of Minnesota. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://open.lib.umn.edu/criminallaw/chapter/2-4-the-burden-of-proof/

6. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Forensic Psychiatry. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018.

7. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Suicide Assessment and Management. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2020.

8. Cook J. Good lawyering and bad role models: the role of respondent’s counsel in a civil commitment hearing. Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics. 2000;14(1):179-195.

9. Ferris CE. The search for due process in civil commitment hearings: how procedural realities have altered substantive standards. Vanderbilt Law Rev. 2008;61(3):959-981.

10. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Civil Commitment and the Mental Health Care Continuum: Historical Trends and Principles for Law and Practice. 2019. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/ebp/civil-commitment-mental-health-care-continuum-historical-trends-principles-law

11. Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological Evaluations for the Courts: A Handbook for Mental Health Profession. 4th ed. Guilford Press; 2018.

1. Pinals DA, Mossman D. Evaluation for Civil Commitment. Oxford University Press; 2012.

2. Thatcher BT, Mossman D. Testifying for civil commitment: help unwilling patients get the treatment they need. Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(11):51-56.

3. Marett CP, Mossman D. What is your liability for involuntary commitment based on faulty information? Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):21-25,33.

4. Ohio Rev Code § 5122.01 (2018).

5. The Burden of Proof. University of Minnesota. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://open.lib.umn.edu/criminallaw/chapter/2-4-the-burden-of-proof/

6. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Forensic Psychiatry. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018.

7. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Suicide Assessment and Management. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2020.

8. Cook J. Good lawyering and bad role models: the role of respondent’s counsel in a civil commitment hearing. Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics. 2000;14(1):179-195.

9. Ferris CE. The search for due process in civil commitment hearings: how procedural realities have altered substantive standards. Vanderbilt Law Rev. 2008;61(3):959-981.

10. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Civil Commitment and the Mental Health Care Continuum: Historical Trends and Principles for Law and Practice. 2019. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/ebp/civil-commitment-mental-health-care-continuum-historical-trends-principles-law

11. Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological Evaluations for the Courts: A Handbook for Mental Health Profession. 4th ed. Guilford Press; 2018.

Preparing patients with serious mental illness for extreme HEAT

Climate change is causing intense heat waves that threaten human health across the globe.

A confluence of factors increases risk

Thermoregulatory dysfunction is thought to be intrinsic to patients with schizophrenia partly due to dysregulated dopaminergic neurotransmission.2 This is compounded by these patients’ higher burden of chronic medical comorbidities such as cardiovascular and respiratory illnesses, which together with psychotropic (ie, antipsychotics, antidepressants, lithium, benzodiazepines) and medical medications (ie, certain antihypertensives, diuretics, treatment for urinary incontinence) further disrupt the body’s cooling strategies and increase vulnerability to heat-related illnesses.1,3 Antipsychotics commonly prescribed to patients with SMI increase hyperthermia risk largely by 2 mechanisms: central and peripheral thermal dysregulation, and anticholinergic properties (ie, olanzapine, clozapine, chlorpromazine).2,3 Other anticholinergic medications prescribed to treat extrapyramidal symptoms (ie, diphenhydramine, benztropine, trihexyphenidyl), anxiety, depression, and insomnia (ie, paroxetine, trazodone, doxepin) further add insult to injury because they impair sweating, which decreases the body’s ability to eliminate heat through evaporation.2,3 Additionally, high temperature exacerbates psychiatric symptoms in patients with SMI, resulting in increased hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

How to keep patients safe

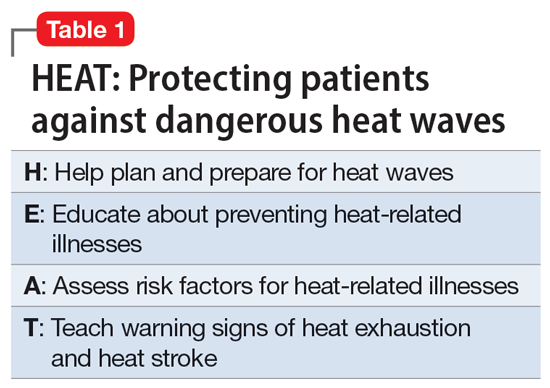

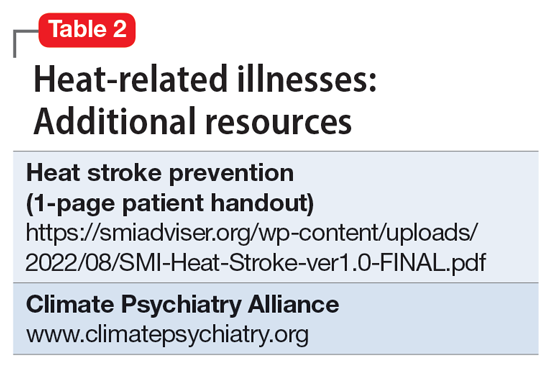

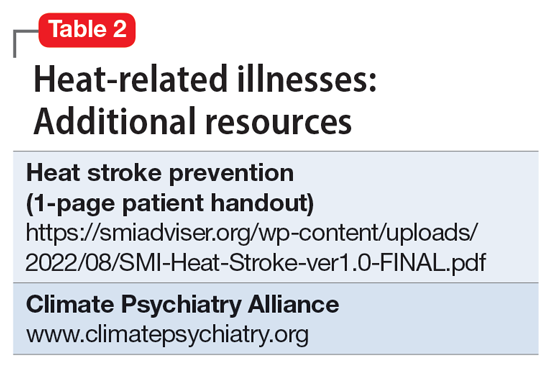

The acronym HEAT provides a framework that psychiatrists can use to highlight the importance of planning for heat waves in their institution and guiding discussions with individual patients about heat-related illnesses (Table 1).

Help the health care system where you work plan and prepare for heat waves. In-service training in mental health settings such as outpatient clinics, shelters, group homes, and residential programs can help staff identify patients at particular risk and reinforce key prevention messages.

Educate patients and their caregivers on strategies for preventing heat-related illness. Informational materials can be distributed in clinics, residential settings, and day programs. A 1-page downloadable pamphlet available at https://smiadviser.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/SMI-Heat-Stroke-ver1.0-FINAL.pdf summarizes key prevention messages of staying hydrated, staying cool, and staying safe.

Assess personalized heat-related risks. Inquire about patients’ daily activities, access to air conditioning, and water intake. Minimize the use of anticholinergic medications. Identify who patients can turn to for assistance, especially for those who struggle with cognitive impairment and social isolation.

Teach patients, caregivers, and staff the signs and symptoms of heat exhaustion and heat stroke and how to respond in such situations.

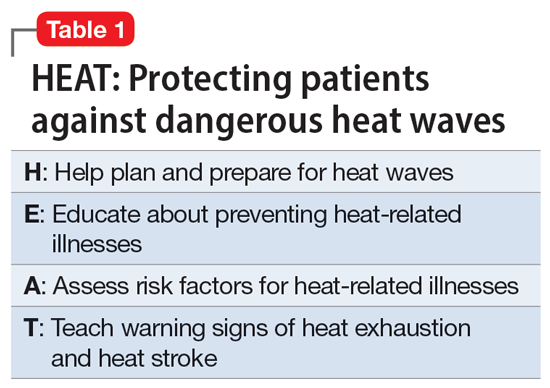

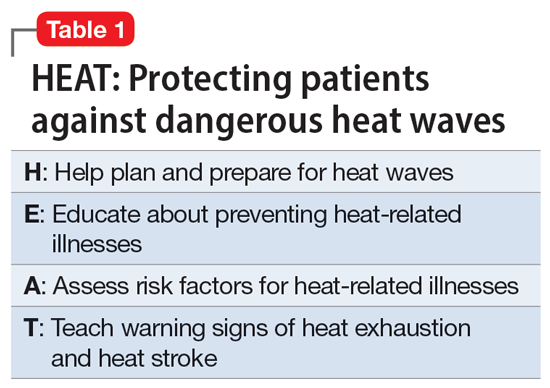

HEAT focuses psychiatric clinicians on preparing and protecting patients with SMI against dangerous heat waves. Clinicians can take a proactive leadership role in disseminating basic principles of heat-related illness prevention and heat-wave toolkits by using resources available from organizations such as the Climate Psychiatry Alliance (Table 2). They can also initiate advocacy efforts to raise awareness about the elevated risks of heat-related illnesses in this vulnerable population.

1. Schmeltz MT, Gamble JL. Risk characterization of hospitalizations for mental illness and/or behavioral disorders with concurrent heat-related illness. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186509. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0186509

2. Lee CP, Chen PJ, Chang CM. Heat stroke during treatment with olanzapine, trihexyphenidyl, and trazodone in a patient with schizophrenia. Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 2015;27(6):380-385.

3. Bongers KS, Salahudeen MS, Peterson GM. Drug-associated non-pyrogenic hyperthermia: a narrative review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;76(1):9-16.

Climate change is causing intense heat waves that threaten human health across the globe.

A confluence of factors increases risk

Thermoregulatory dysfunction is thought to be intrinsic to patients with schizophrenia partly due to dysregulated dopaminergic neurotransmission.2 This is compounded by these patients’ higher burden of chronic medical comorbidities such as cardiovascular and respiratory illnesses, which together with psychotropic (ie, antipsychotics, antidepressants, lithium, benzodiazepines) and medical medications (ie, certain antihypertensives, diuretics, treatment for urinary incontinence) further disrupt the body’s cooling strategies and increase vulnerability to heat-related illnesses.1,3 Antipsychotics commonly prescribed to patients with SMI increase hyperthermia risk largely by 2 mechanisms: central and peripheral thermal dysregulation, and anticholinergic properties (ie, olanzapine, clozapine, chlorpromazine).2,3 Other anticholinergic medications prescribed to treat extrapyramidal symptoms (ie, diphenhydramine, benztropine, trihexyphenidyl), anxiety, depression, and insomnia (ie, paroxetine, trazodone, doxepin) further add insult to injury because they impair sweating, which decreases the body’s ability to eliminate heat through evaporation.2,3 Additionally, high temperature exacerbates psychiatric symptoms in patients with SMI, resulting in increased hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

How to keep patients safe

The acronym HEAT provides a framework that psychiatrists can use to highlight the importance of planning for heat waves in their institution and guiding discussions with individual patients about heat-related illnesses (Table 1).

Help the health care system where you work plan and prepare for heat waves. In-service training in mental health settings such as outpatient clinics, shelters, group homes, and residential programs can help staff identify patients at particular risk and reinforce key prevention messages.

Educate patients and their caregivers on strategies for preventing heat-related illness. Informational materials can be distributed in clinics, residential settings, and day programs. A 1-page downloadable pamphlet available at https://smiadviser.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/SMI-Heat-Stroke-ver1.0-FINAL.pdf summarizes key prevention messages of staying hydrated, staying cool, and staying safe.

Assess personalized heat-related risks. Inquire about patients’ daily activities, access to air conditioning, and water intake. Minimize the use of anticholinergic medications. Identify who patients can turn to for assistance, especially for those who struggle with cognitive impairment and social isolation.

Teach patients, caregivers, and staff the signs and symptoms of heat exhaustion and heat stroke and how to respond in such situations.

HEAT focuses psychiatric clinicians on preparing and protecting patients with SMI against dangerous heat waves. Clinicians can take a proactive leadership role in disseminating basic principles of heat-related illness prevention and heat-wave toolkits by using resources available from organizations such as the Climate Psychiatry Alliance (Table 2). They can also initiate advocacy efforts to raise awareness about the elevated risks of heat-related illnesses in this vulnerable population.

Climate change is causing intense heat waves that threaten human health across the globe.

A confluence of factors increases risk

Thermoregulatory dysfunction is thought to be intrinsic to patients with schizophrenia partly due to dysregulated dopaminergic neurotransmission.2 This is compounded by these patients’ higher burden of chronic medical comorbidities such as cardiovascular and respiratory illnesses, which together with psychotropic (ie, antipsychotics, antidepressants, lithium, benzodiazepines) and medical medications (ie, certain antihypertensives, diuretics, treatment for urinary incontinence) further disrupt the body’s cooling strategies and increase vulnerability to heat-related illnesses.1,3 Antipsychotics commonly prescribed to patients with SMI increase hyperthermia risk largely by 2 mechanisms: central and peripheral thermal dysregulation, and anticholinergic properties (ie, olanzapine, clozapine, chlorpromazine).2,3 Other anticholinergic medications prescribed to treat extrapyramidal symptoms (ie, diphenhydramine, benztropine, trihexyphenidyl), anxiety, depression, and insomnia (ie, paroxetine, trazodone, doxepin) further add insult to injury because they impair sweating, which decreases the body’s ability to eliminate heat through evaporation.2,3 Additionally, high temperature exacerbates psychiatric symptoms in patients with SMI, resulting in increased hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

How to keep patients safe

The acronym HEAT provides a framework that psychiatrists can use to highlight the importance of planning for heat waves in their institution and guiding discussions with individual patients about heat-related illnesses (Table 1).

Help the health care system where you work plan and prepare for heat waves. In-service training in mental health settings such as outpatient clinics, shelters, group homes, and residential programs can help staff identify patients at particular risk and reinforce key prevention messages.

Educate patients and their caregivers on strategies for preventing heat-related illness. Informational materials can be distributed in clinics, residential settings, and day programs. A 1-page downloadable pamphlet available at https://smiadviser.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/SMI-Heat-Stroke-ver1.0-FINAL.pdf summarizes key prevention messages of staying hydrated, staying cool, and staying safe.

Assess personalized heat-related risks. Inquire about patients’ daily activities, access to air conditioning, and water intake. Minimize the use of anticholinergic medications. Identify who patients can turn to for assistance, especially for those who struggle with cognitive impairment and social isolation.

Teach patients, caregivers, and staff the signs and symptoms of heat exhaustion and heat stroke and how to respond in such situations.

HEAT focuses psychiatric clinicians on preparing and protecting patients with SMI against dangerous heat waves. Clinicians can take a proactive leadership role in disseminating basic principles of heat-related illness prevention and heat-wave toolkits by using resources available from organizations such as the Climate Psychiatry Alliance (Table 2). They can also initiate advocacy efforts to raise awareness about the elevated risks of heat-related illnesses in this vulnerable population.

1. Schmeltz MT, Gamble JL. Risk characterization of hospitalizations for mental illness and/or behavioral disorders with concurrent heat-related illness. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186509. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0186509

2. Lee CP, Chen PJ, Chang CM. Heat stroke during treatment with olanzapine, trihexyphenidyl, and trazodone in a patient with schizophrenia. Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 2015;27(6):380-385.

3. Bongers KS, Salahudeen MS, Peterson GM. Drug-associated non-pyrogenic hyperthermia: a narrative review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;76(1):9-16.

1. Schmeltz MT, Gamble JL. Risk characterization of hospitalizations for mental illness and/or behavioral disorders with concurrent heat-related illness. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186509. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0186509

2. Lee CP, Chen PJ, Chang CM. Heat stroke during treatment with olanzapine, trihexyphenidyl, and trazodone in a patient with schizophrenia. Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 2015;27(6):380-385.

3. Bongers KS, Salahudeen MS, Peterson GM. Drug-associated non-pyrogenic hyperthermia: a narrative review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;76(1):9-16.

Lithium for bipolar disorder: Which patients will respond?

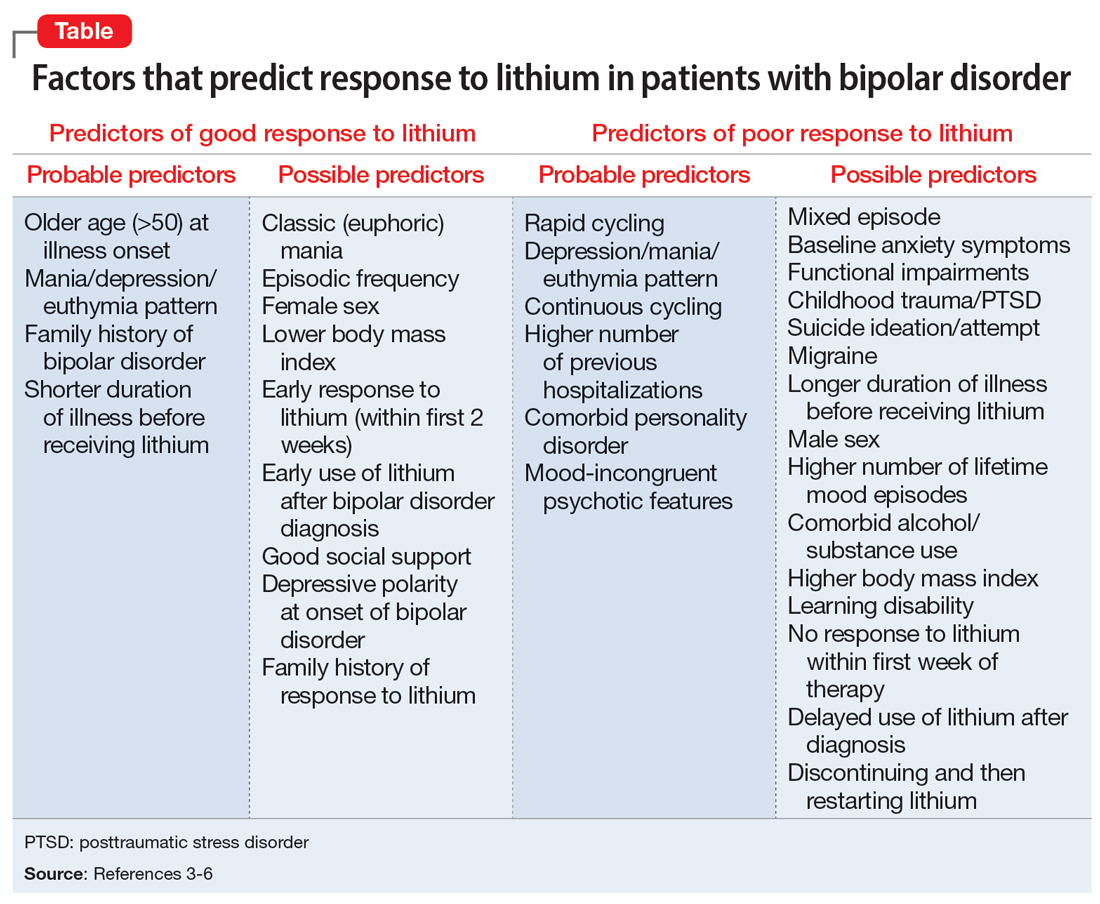

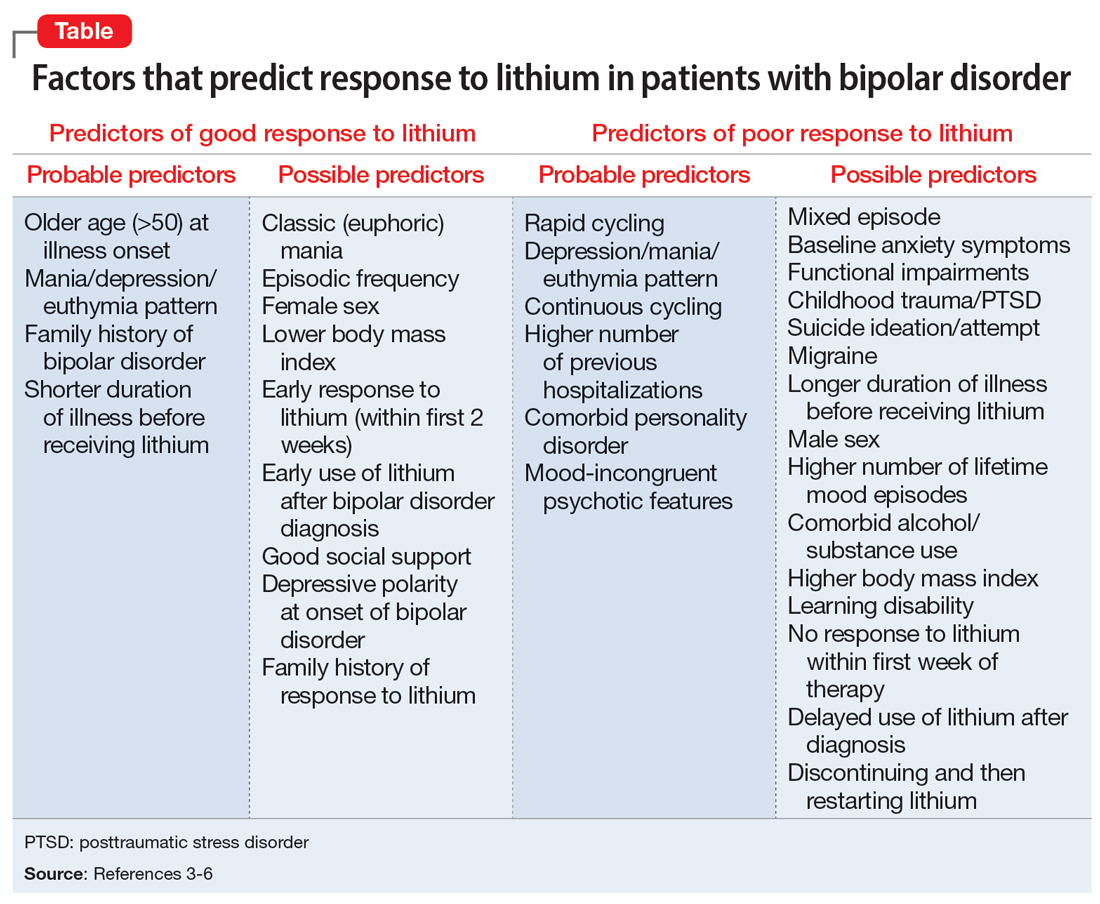

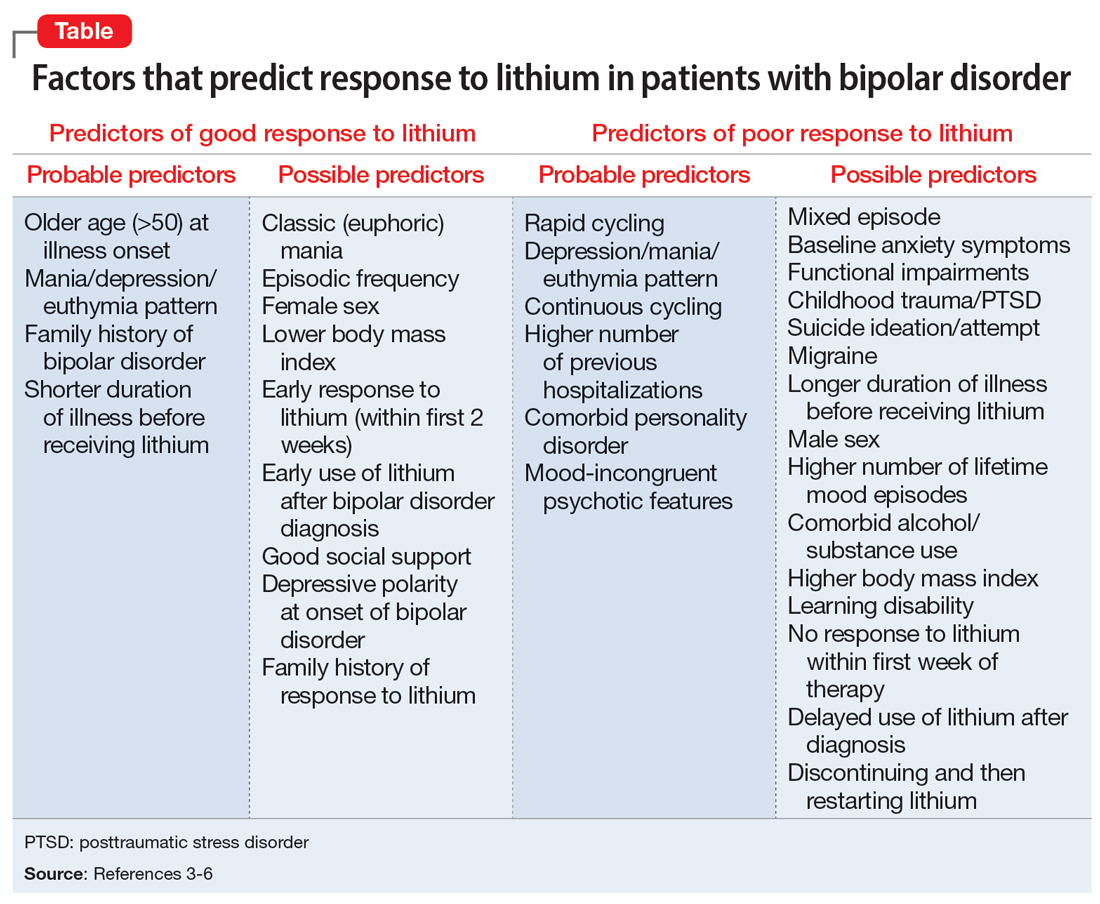

Though Cade discovered it 70 years ago, lithium is still considered the gold standard treatment for preventing manic and depressive phases of bipolar disorder (BD). In addition to its primary indication as a mood stabilizer, lithium has demonstrated efficacy as an augmenting medication for unipolar major depressive disorder.1 While lithium is a first-line agent for BD, it does not improve symptoms in every patient. In a 2004 meta-analysis of 5 randomized controlled trials of patients with BD, Geddes et al2 found lithium was more effective than placebo in preventing the recurrence of mania, with 60% in the lithium group remaining stable compared to 40% in the placebo group. Being able to predict which patients will respond to lithium is crucial to prevent unnecessary exposure to lithium, which can produce significant adverse effects, including somnolence, nausea, diarrhea, and hypothyroidism.2

Several studies have investigated various clinical factors that might predict which patients with BD will respond to lithium. In a review, Kleindienst et al3 highlighted 3 factors that predicted a positive response to lithium:

- fewer hospitalizations prior to treatment

- an episodic course characterized sequentially by mania, depression, and then euthymia

- a later age (>50) at onset of BD.

Recent studies and reviews have isolated additional positive predictors, including having a family history of BD and a shorter duration of illness before receiving lithium, as well as negative predictors, such as rapid cycling, a large number of previous hospitalizations, a depression/mania/euthymia pattern, mood-incongruent psychotic features, and the presence of residual symptoms between mood episodes.3,4

The Table provides a list of probable and possible positive and negative predictors for therapeutic response to lithium in patients with BD.3-6 While relevant, the factors listed as possible predictors may not carry as much influence on lithium responsivity as those categorized as probable predictors.

Because of heterogeneity among studies, clinicians should consider their patient’s presentation as a whole, rather than basing medication choice on independent factors. Ultimately, more studies are required to fully determine the most relevant clinical parameters for lithium response. Overall, however, it appears these clinical factors could be extremely useful to guide psychiatrists in the optimal use of lithium while caring for patients with BD.

1. Crossley NA, Bauer M. Acceleration and augmentation of antidepressants with lithium for depressive disorders: two meta-analyses of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(6):935-940.

2. Geddes JR, Burgess S, Hawton K, et al. Long-term lithium therapy for bipolar disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;1m61(2):217-222.

3. Kleindienst N, Engel RR, Greil W. Which clinical factors predict response to prophylactic lithium? A systematic review for bipolar disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7(5):404-417.

4. Kleindienst N, Engel RR, Greil W. Psychosocial and demographic factors associated with response to prophylactic lithium: a systematic review for bipolar disorders. Psychol Med. 2005;35(12):1685-1694.

5. Hui TP, Kandola A, Shen L, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical predictors of lithium response in bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019;140(2):94-115.

6. Grillault Laroche D, Etain B, Severus E, et al. Socio-demographic and clinical predictors of outcome to long-term treatment with lithium in bipolar disorders: a systematic review of the contemporary literature and recommendations from the ISBD/IGSLI Task Force on treatment with lithium. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2020;8(1):40.

Though Cade discovered it 70 years ago, lithium is still considered the gold standard treatment for preventing manic and depressive phases of bipolar disorder (BD). In addition to its primary indication as a mood stabilizer, lithium has demonstrated efficacy as an augmenting medication for unipolar major depressive disorder.1 While lithium is a first-line agent for BD, it does not improve symptoms in every patient. In a 2004 meta-analysis of 5 randomized controlled trials of patients with BD, Geddes et al2 found lithium was more effective than placebo in preventing the recurrence of mania, with 60% in the lithium group remaining stable compared to 40% in the placebo group. Being able to predict which patients will respond to lithium is crucial to prevent unnecessary exposure to lithium, which can produce significant adverse effects, including somnolence, nausea, diarrhea, and hypothyroidism.2

Several studies have investigated various clinical factors that might predict which patients with BD will respond to lithium. In a review, Kleindienst et al3 highlighted 3 factors that predicted a positive response to lithium:

- fewer hospitalizations prior to treatment

- an episodic course characterized sequentially by mania, depression, and then euthymia

- a later age (>50) at onset of BD.

Recent studies and reviews have isolated additional positive predictors, including having a family history of BD and a shorter duration of illness before receiving lithium, as well as negative predictors, such as rapid cycling, a large number of previous hospitalizations, a depression/mania/euthymia pattern, mood-incongruent psychotic features, and the presence of residual symptoms between mood episodes.3,4

The Table provides a list of probable and possible positive and negative predictors for therapeutic response to lithium in patients with BD.3-6 While relevant, the factors listed as possible predictors may not carry as much influence on lithium responsivity as those categorized as probable predictors.

Because of heterogeneity among studies, clinicians should consider their patient’s presentation as a whole, rather than basing medication choice on independent factors. Ultimately, more studies are required to fully determine the most relevant clinical parameters for lithium response. Overall, however, it appears these clinical factors could be extremely useful to guide psychiatrists in the optimal use of lithium while caring for patients with BD.

Though Cade discovered it 70 years ago, lithium is still considered the gold standard treatment for preventing manic and depressive phases of bipolar disorder (BD). In addition to its primary indication as a mood stabilizer, lithium has demonstrated efficacy as an augmenting medication for unipolar major depressive disorder.1 While lithium is a first-line agent for BD, it does not improve symptoms in every patient. In a 2004 meta-analysis of 5 randomized controlled trials of patients with BD, Geddes et al2 found lithium was more effective than placebo in preventing the recurrence of mania, with 60% in the lithium group remaining stable compared to 40% in the placebo group. Being able to predict which patients will respond to lithium is crucial to prevent unnecessary exposure to lithium, which can produce significant adverse effects, including somnolence, nausea, diarrhea, and hypothyroidism.2

Several studies have investigated various clinical factors that might predict which patients with BD will respond to lithium. In a review, Kleindienst et al3 highlighted 3 factors that predicted a positive response to lithium:

- fewer hospitalizations prior to treatment

- an episodic course characterized sequentially by mania, depression, and then euthymia

- a later age (>50) at onset of BD.

Recent studies and reviews have isolated additional positive predictors, including having a family history of BD and a shorter duration of illness before receiving lithium, as well as negative predictors, such as rapid cycling, a large number of previous hospitalizations, a depression/mania/euthymia pattern, mood-incongruent psychotic features, and the presence of residual symptoms between mood episodes.3,4

The Table provides a list of probable and possible positive and negative predictors for therapeutic response to lithium in patients with BD.3-6 While relevant, the factors listed as possible predictors may not carry as much influence on lithium responsivity as those categorized as probable predictors.

Because of heterogeneity among studies, clinicians should consider their patient’s presentation as a whole, rather than basing medication choice on independent factors. Ultimately, more studies are required to fully determine the most relevant clinical parameters for lithium response. Overall, however, it appears these clinical factors could be extremely useful to guide psychiatrists in the optimal use of lithium while caring for patients with BD.

1. Crossley NA, Bauer M. Acceleration and augmentation of antidepressants with lithium for depressive disorders: two meta-analyses of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(6):935-940.

2. Geddes JR, Burgess S, Hawton K, et al. Long-term lithium therapy for bipolar disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;1m61(2):217-222.

3. Kleindienst N, Engel RR, Greil W. Which clinical factors predict response to prophylactic lithium? A systematic review for bipolar disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7(5):404-417.

4. Kleindienst N, Engel RR, Greil W. Psychosocial and demographic factors associated with response to prophylactic lithium: a systematic review for bipolar disorders. Psychol Med. 2005;35(12):1685-1694.

5. Hui TP, Kandola A, Shen L, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical predictors of lithium response in bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019;140(2):94-115.

6. Grillault Laroche D, Etain B, Severus E, et al. Socio-demographic and clinical predictors of outcome to long-term treatment with lithium in bipolar disorders: a systematic review of the contemporary literature and recommendations from the ISBD/IGSLI Task Force on treatment with lithium. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2020;8(1):40.

1. Crossley NA, Bauer M. Acceleration and augmentation of antidepressants with lithium for depressive disorders: two meta-analyses of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(6):935-940.

2. Geddes JR, Burgess S, Hawton K, et al. Long-term lithium therapy for bipolar disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;1m61(2):217-222.

3. Kleindienst N, Engel RR, Greil W. Which clinical factors predict response to prophylactic lithium? A systematic review for bipolar disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7(5):404-417.

4. Kleindienst N, Engel RR, Greil W. Psychosocial and demographic factors associated with response to prophylactic lithium: a systematic review for bipolar disorders. Psychol Med. 2005;35(12):1685-1694.

5. Hui TP, Kandola A, Shen L, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical predictors of lithium response in bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019;140(2):94-115.

6. Grillault Laroche D, Etain B, Severus E, et al. Socio-demographic and clinical predictors of outcome to long-term treatment with lithium in bipolar disorders: a systematic review of the contemporary literature and recommendations from the ISBD/IGSLI Task Force on treatment with lithium. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2020;8(1):40.

Melatonin as a sleep aid: Are you prescribing it correctly?

Difficulty achieving regular restorative sleep is a common symptom of many psychiatric illnesses and can pose a pharmaceutical challenge, particularly for patients who have contraindications to benzodiazepines or sedative-hypnotics. Melatonin is commonly used to treat insomnia and circadian rhythm disorders in hospitalized patients because it is largely considered safe, nonhabit forming, unlikely to interact with other medications, and possibly protective against delirium.1 We support its short-term use in patients with sleep disruption, even if they do not meet the diagnostic criteria for insomnia or a circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorder. However, this use should be guided by consideration of the known physiological actions of melatonin, and not by an assumption that it acts as a simple sedative-hypnotic.

How melatonin works