User login

Trading in work-life balance for a well-balanced life

My residency supervisor candidly asked me today – Isn’t stressing out about writing an article on work-life balance kind of missing the point? Well, yeah, that’s why she’s my supervisor. This brings me to one of the lesser advertised tips to avoiding burnout, which is: Get yourself a great mensch. But I’m getting ahead of myself here. The plan was to have 10 perfectly delineated rules, because if it worked for Letterman and Moses, it should work for residency. More to come on that.

Another part of the plan was to have this article finished by last weekend, but long call was Saturday. This was followed by long call recovery consisting of sleeping in so late my dad texted and left a voicemail asking, what happened? I haven’t heard from you all weekend. Then there was the obligatory run on the treadmill so the gooey cinnamon rolls the nurses baked and generously invited me to on Thursday would not stick around long enough for my husband to wonder if this was the beginning of me letting myself go. Isn’t that a lovely phrase?

Monday was Monday. How does anyone get anything done on Mondays? I had a new team, two new patients to learn and discharge. Plus, it was the first day that cracked 50 degrees in 5 months. I had to meet up with a friend, grab some coffee, and gossip walk around the lake. This was before we found out another friend was being slammed with consults in the emergency room. So there I was right back at the hospital Monday night with a cream cheese cherry pastry to cheer up my compatriot in the struggle.

This brings me to Tuesday. I had planned to be at the editing stage of this article on Tuesday. But didactics ran long due to everyone being so engaged in our formulations lecture, I didn’t have a shot at looking at this thing until lunchtime. Lunchtime came, and as I opened Microsoft Word among my dollar turkey sandwich and mini Purell bottles stationed around me like glorious little sergeants, I heard the gingerly utterings of a medical student: Um, if you have a moment, could you tell me the difference between the side-effect profile of first-generation and second-generation antipsychotics?

An hour later, I was informed that an admit was on the way and was traveling from out of state, set to arrive a half-hour before shift’s end. Did I mention he arrived with two family members in tow who wanted to talk about how things went wrong starting 20 years ago? Then there was the patient to see who I knew would pout if I didn’t spend at least a half-hour checking in. You know, the one the nurses always try to save me from even though I secretly never wanted to be saved.

I finally drove home 2 hours later than anticipated with a smile on my face. I should repeat that, WITH A SMILE ON MY FACE. I felt good because I’d done good. After all, there’s even a little sunlight left. When I walk in the front door, I kiss my husband and then immediately delve into a new story from the day. We laugh. We warm up leftovers, sit on the couch with our bare feet on the table, and catch an hour of American Idol (talent never gets old). Then it’s time to meet this maker.

The strange thing is, the person who began this column with all of her well-intentioned plans feels very different from the person who has made it to the deadline. There is a whole life lived in between. All of the readings I had done, notations I had made, seem kind of beside the point. I could pepper you with statistics and evidence-based outcomes warning of divorce, substance abuse, physician suicide, patient errors, and the like, which are all very real outcomes of poorly balanced lives. But I think we know all of that. It’s the in between space, the living part where so many of us lose our way. So instead of referenced journals, I offer you my journey. Because I can truly say that for the last 3 months of the most difficult year of residency, I have been happy. May this piece be also with you.

Dr. Schmidt, a second-year psychiatry resident at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., is interested in psychodynamic therapy and in pursuing a fellowship in addictions. After obtaining a bachelor of arts at the University of California, Berkeley, she earned a master of arts degree in philosophy and humanities at the University of Chicago. She attended medical school at the University of Illinois College of Medicine at Peoria.

My residency supervisor candidly asked me today – Isn’t stressing out about writing an article on work-life balance kind of missing the point? Well, yeah, that’s why she’s my supervisor. This brings me to one of the lesser advertised tips to avoiding burnout, which is: Get yourself a great mensch. But I’m getting ahead of myself here. The plan was to have 10 perfectly delineated rules, because if it worked for Letterman and Moses, it should work for residency. More to come on that.

Another part of the plan was to have this article finished by last weekend, but long call was Saturday. This was followed by long call recovery consisting of sleeping in so late my dad texted and left a voicemail asking, what happened? I haven’t heard from you all weekend. Then there was the obligatory run on the treadmill so the gooey cinnamon rolls the nurses baked and generously invited me to on Thursday would not stick around long enough for my husband to wonder if this was the beginning of me letting myself go. Isn’t that a lovely phrase?

Monday was Monday. How does anyone get anything done on Mondays? I had a new team, two new patients to learn and discharge. Plus, it was the first day that cracked 50 degrees in 5 months. I had to meet up with a friend, grab some coffee, and gossip walk around the lake. This was before we found out another friend was being slammed with consults in the emergency room. So there I was right back at the hospital Monday night with a cream cheese cherry pastry to cheer up my compatriot in the struggle.

This brings me to Tuesday. I had planned to be at the editing stage of this article on Tuesday. But didactics ran long due to everyone being so engaged in our formulations lecture, I didn’t have a shot at looking at this thing until lunchtime. Lunchtime came, and as I opened Microsoft Word among my dollar turkey sandwich and mini Purell bottles stationed around me like glorious little sergeants, I heard the gingerly utterings of a medical student: Um, if you have a moment, could you tell me the difference between the side-effect profile of first-generation and second-generation antipsychotics?

An hour later, I was informed that an admit was on the way and was traveling from out of state, set to arrive a half-hour before shift’s end. Did I mention he arrived with two family members in tow who wanted to talk about how things went wrong starting 20 years ago? Then there was the patient to see who I knew would pout if I didn’t spend at least a half-hour checking in. You know, the one the nurses always try to save me from even though I secretly never wanted to be saved.

I finally drove home 2 hours later than anticipated with a smile on my face. I should repeat that, WITH A SMILE ON MY FACE. I felt good because I’d done good. After all, there’s even a little sunlight left. When I walk in the front door, I kiss my husband and then immediately delve into a new story from the day. We laugh. We warm up leftovers, sit on the couch with our bare feet on the table, and catch an hour of American Idol (talent never gets old). Then it’s time to meet this maker.

The strange thing is, the person who began this column with all of her well-intentioned plans feels very different from the person who has made it to the deadline. There is a whole life lived in between. All of the readings I had done, notations I had made, seem kind of beside the point. I could pepper you with statistics and evidence-based outcomes warning of divorce, substance abuse, physician suicide, patient errors, and the like, which are all very real outcomes of poorly balanced lives. But I think we know all of that. It’s the in between space, the living part where so many of us lose our way. So instead of referenced journals, I offer you my journey. Because I can truly say that for the last 3 months of the most difficult year of residency, I have been happy. May this piece be also with you.

Dr. Schmidt, a second-year psychiatry resident at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., is interested in psychodynamic therapy and in pursuing a fellowship in addictions. After obtaining a bachelor of arts at the University of California, Berkeley, she earned a master of arts degree in philosophy and humanities at the University of Chicago. She attended medical school at the University of Illinois College of Medicine at Peoria.

My residency supervisor candidly asked me today – Isn’t stressing out about writing an article on work-life balance kind of missing the point? Well, yeah, that’s why she’s my supervisor. This brings me to one of the lesser advertised tips to avoiding burnout, which is: Get yourself a great mensch. But I’m getting ahead of myself here. The plan was to have 10 perfectly delineated rules, because if it worked for Letterman and Moses, it should work for residency. More to come on that.

Another part of the plan was to have this article finished by last weekend, but long call was Saturday. This was followed by long call recovery consisting of sleeping in so late my dad texted and left a voicemail asking, what happened? I haven’t heard from you all weekend. Then there was the obligatory run on the treadmill so the gooey cinnamon rolls the nurses baked and generously invited me to on Thursday would not stick around long enough for my husband to wonder if this was the beginning of me letting myself go. Isn’t that a lovely phrase?

Monday was Monday. How does anyone get anything done on Mondays? I had a new team, two new patients to learn and discharge. Plus, it was the first day that cracked 50 degrees in 5 months. I had to meet up with a friend, grab some coffee, and gossip walk around the lake. This was before we found out another friend was being slammed with consults in the emergency room. So there I was right back at the hospital Monday night with a cream cheese cherry pastry to cheer up my compatriot in the struggle.

This brings me to Tuesday. I had planned to be at the editing stage of this article on Tuesday. But didactics ran long due to everyone being so engaged in our formulations lecture, I didn’t have a shot at looking at this thing until lunchtime. Lunchtime came, and as I opened Microsoft Word among my dollar turkey sandwich and mini Purell bottles stationed around me like glorious little sergeants, I heard the gingerly utterings of a medical student: Um, if you have a moment, could you tell me the difference between the side-effect profile of first-generation and second-generation antipsychotics?

An hour later, I was informed that an admit was on the way and was traveling from out of state, set to arrive a half-hour before shift’s end. Did I mention he arrived with two family members in tow who wanted to talk about how things went wrong starting 20 years ago? Then there was the patient to see who I knew would pout if I didn’t spend at least a half-hour checking in. You know, the one the nurses always try to save me from even though I secretly never wanted to be saved.

I finally drove home 2 hours later than anticipated with a smile on my face. I should repeat that, WITH A SMILE ON MY FACE. I felt good because I’d done good. After all, there’s even a little sunlight left. When I walk in the front door, I kiss my husband and then immediately delve into a new story from the day. We laugh. We warm up leftovers, sit on the couch with our bare feet on the table, and catch an hour of American Idol (talent never gets old). Then it’s time to meet this maker.

The strange thing is, the person who began this column with all of her well-intentioned plans feels very different from the person who has made it to the deadline. There is a whole life lived in between. All of the readings I had done, notations I had made, seem kind of beside the point. I could pepper you with statistics and evidence-based outcomes warning of divorce, substance abuse, physician suicide, patient errors, and the like, which are all very real outcomes of poorly balanced lives. But I think we know all of that. It’s the in between space, the living part where so many of us lose our way. So instead of referenced journals, I offer you my journey. Because I can truly say that for the last 3 months of the most difficult year of residency, I have been happy. May this piece be also with you.

Dr. Schmidt, a second-year psychiatry resident at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., is interested in psychodynamic therapy and in pursuing a fellowship in addictions. After obtaining a bachelor of arts at the University of California, Berkeley, she earned a master of arts degree in philosophy and humanities at the University of Chicago. She attended medical school at the University of Illinois College of Medicine at Peoria.

The patient refuses to cooperate. What can you do? What should you do?

The real estate business embraces the concept of ownership using the term “bundle of rights.” Real estate agents view full, unaffected ownership of a real property as complete (ie, undivided) and, when ownership is shared, talk about percentages of that bundle.

The same principle can be applied to guardianship. Because we are our own guardians, we own a full, undivided bundle of rights, including all our constitutional rights and the right to make decisions— even bad ones. Of course, an undivided bundle also means that we are fully responsible for the decisions we make.

When a patient requires representation

There may be a situation when we would give someone else the authority to represent us for a specific reason. In this case we would authorize this person to act on our behalf as we would do ourselves—yet we still retain 100% ownership of the “bundle,” and therefore can revoke this authorization at any time. The person we hire (appoint) to represent us will become our power of attorney (POA), and because we appoint this person for a specific situation (handle certain medical affairs, manage some financial affairs, sign real estate documents, etc.), this kind or POA is called “specific” or “special.” When we give someone the right to represent us in any or all of our affairs, this POA is called “general” or “durable.”

It is important to mention that as long as we continue to have psychological capacity and are willing to continue to be our own guardians (own 100% of the bundle of rights), we can terminate any POA we have appointed previously or designate another person to represent us as a “special” or “general” POA. Because of this, if an older patient—who is legally competent but physically unable to live on his (her) own— refuses to enter a long-term care facility, he (she) cannot be sent there against his will, even if the POA insists on it. Because of this, if the patient’s primary team strongly disagrees with this patient’s decision, his (her) “decision-making capacity” should be assessed and, if necessary, a competency hearing will need to be conducted. The court will then decide if this person is able (or unable) to handle his own affairs, and if the court decides that the person cannot be responsible to provide himself with food, health care, housing, and other necessities, the guardian (relative, friend, public administrator, etc.) will be appointed to do so.

Evaluating decision-making capacity

Determining “decision-making capacity” should not be confused with the legal concept of “competence.” We, physicians, often are called to evaluate a patient and give our opinion of the current level of this patient’s functioning (including his [her] decision-making capacity), and we—ourselves and a requesting team—need to be clear that it is merely our opinion and should be used as such. We need to remember that even if a patient is judged to be legally incompetent to handle financial affairs, he (she) might retain sufficient ability to make decisions about treatments.

We also need to remember that decision-making capacity can change, depending on medical conditions (severe anxiety, delirium), successful treatments, substance intoxication, etc. Because of this, we need to communicate to the requesting team that “decision-making ability” is situation-specific and time-specific, and that failure to make a decision on one issue should not be generalized to other aspects of the patient’s life.

Any physician can evaluate patient’s decision-making ability, but traditionally the psychiatry team is called to do so. It usually happens because the primary medical team needs us to provide “a third-party validation,” or because of the common misperception that only the psychiatric team can initiate a civil involuntary detention when necessary.

In any case, regardless of who evaluates the patient, specific points need to be addressed and the following questions need to be answered:

• Does the patient understand the nature of his (her) condition?

• Does the patient understand what treatment we are proposing or what he should do?

• Does the patient understand the consequences (good or bad) if he rejects our proposed action or treatment?

When information (discharge plan, treatment plan, etc.) is presented to patients, we should ask them to repeat it in their own words. We should not expect them to understand all of the technical aspects. We should consider patients’ intelligence level and their ability to communicate; if they can clearly verbalize their understanding of information and be consistent in their wish to continue with their decision, we have to declare that they have decision-making capability and able to proceed with their chosen treatment.

More matters that need to be mentioned

Restrictions on the patient. We need to remember that, even if a patient is thought to be able to make his own decisions, there may be some situations when he can be held in the hospital against his will. These usually are the cases when the patient is psychiatrically or medically unstable (unable to care of himself), but also if the patient is at risk of harming himself or others, subject of elder abuse, or suspected of being an abuser.

Restrictions on the practitioner. Even if the patient is determined to be lacking decision-making capacity, we, physicians, cannot perform tests, procedures, or do the placements without the patient’s agreement.

Informed consent doctrine is applicable in this case, and if performing a test or procedure is necessary (except life- or limb-saving emergencies, when doctrine of physician prerogative applies), or if there a disagreement in post-discharge placement, the emergency guardianship may need to be pursued.

Disclosure

Dr. Graypel reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

The real estate business embraces the concept of ownership using the term “bundle of rights.” Real estate agents view full, unaffected ownership of a real property as complete (ie, undivided) and, when ownership is shared, talk about percentages of that bundle.

The same principle can be applied to guardianship. Because we are our own guardians, we own a full, undivided bundle of rights, including all our constitutional rights and the right to make decisions— even bad ones. Of course, an undivided bundle also means that we are fully responsible for the decisions we make.

When a patient requires representation

There may be a situation when we would give someone else the authority to represent us for a specific reason. In this case we would authorize this person to act on our behalf as we would do ourselves—yet we still retain 100% ownership of the “bundle,” and therefore can revoke this authorization at any time. The person we hire (appoint) to represent us will become our power of attorney (POA), and because we appoint this person for a specific situation (handle certain medical affairs, manage some financial affairs, sign real estate documents, etc.), this kind or POA is called “specific” or “special.” When we give someone the right to represent us in any or all of our affairs, this POA is called “general” or “durable.”

It is important to mention that as long as we continue to have psychological capacity and are willing to continue to be our own guardians (own 100% of the bundle of rights), we can terminate any POA we have appointed previously or designate another person to represent us as a “special” or “general” POA. Because of this, if an older patient—who is legally competent but physically unable to live on his (her) own— refuses to enter a long-term care facility, he (she) cannot be sent there against his will, even if the POA insists on it. Because of this, if the patient’s primary team strongly disagrees with this patient’s decision, his (her) “decision-making capacity” should be assessed and, if necessary, a competency hearing will need to be conducted. The court will then decide if this person is able (or unable) to handle his own affairs, and if the court decides that the person cannot be responsible to provide himself with food, health care, housing, and other necessities, the guardian (relative, friend, public administrator, etc.) will be appointed to do so.

Evaluating decision-making capacity

Determining “decision-making capacity” should not be confused with the legal concept of “competence.” We, physicians, often are called to evaluate a patient and give our opinion of the current level of this patient’s functioning (including his [her] decision-making capacity), and we—ourselves and a requesting team—need to be clear that it is merely our opinion and should be used as such. We need to remember that even if a patient is judged to be legally incompetent to handle financial affairs, he (she) might retain sufficient ability to make decisions about treatments.

We also need to remember that decision-making capacity can change, depending on medical conditions (severe anxiety, delirium), successful treatments, substance intoxication, etc. Because of this, we need to communicate to the requesting team that “decision-making ability” is situation-specific and time-specific, and that failure to make a decision on one issue should not be generalized to other aspects of the patient’s life.

Any physician can evaluate patient’s decision-making ability, but traditionally the psychiatry team is called to do so. It usually happens because the primary medical team needs us to provide “a third-party validation,” or because of the common misperception that only the psychiatric team can initiate a civil involuntary detention when necessary.

In any case, regardless of who evaluates the patient, specific points need to be addressed and the following questions need to be answered:

• Does the patient understand the nature of his (her) condition?

• Does the patient understand what treatment we are proposing or what he should do?

• Does the patient understand the consequences (good or bad) if he rejects our proposed action or treatment?

When information (discharge plan, treatment plan, etc.) is presented to patients, we should ask them to repeat it in their own words. We should not expect them to understand all of the technical aspects. We should consider patients’ intelligence level and their ability to communicate; if they can clearly verbalize their understanding of information and be consistent in their wish to continue with their decision, we have to declare that they have decision-making capability and able to proceed with their chosen treatment.

More matters that need to be mentioned

Restrictions on the patient. We need to remember that, even if a patient is thought to be able to make his own decisions, there may be some situations when he can be held in the hospital against his will. These usually are the cases when the patient is psychiatrically or medically unstable (unable to care of himself), but also if the patient is at risk of harming himself or others, subject of elder abuse, or suspected of being an abuser.

Restrictions on the practitioner. Even if the patient is determined to be lacking decision-making capacity, we, physicians, cannot perform tests, procedures, or do the placements without the patient’s agreement.

Informed consent doctrine is applicable in this case, and if performing a test or procedure is necessary (except life- or limb-saving emergencies, when doctrine of physician prerogative applies), or if there a disagreement in post-discharge placement, the emergency guardianship may need to be pursued.

Disclosure

Dr. Graypel reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

The real estate business embraces the concept of ownership using the term “bundle of rights.” Real estate agents view full, unaffected ownership of a real property as complete (ie, undivided) and, when ownership is shared, talk about percentages of that bundle.

The same principle can be applied to guardianship. Because we are our own guardians, we own a full, undivided bundle of rights, including all our constitutional rights and the right to make decisions— even bad ones. Of course, an undivided bundle also means that we are fully responsible for the decisions we make.

When a patient requires representation

There may be a situation when we would give someone else the authority to represent us for a specific reason. In this case we would authorize this person to act on our behalf as we would do ourselves—yet we still retain 100% ownership of the “bundle,” and therefore can revoke this authorization at any time. The person we hire (appoint) to represent us will become our power of attorney (POA), and because we appoint this person for a specific situation (handle certain medical affairs, manage some financial affairs, sign real estate documents, etc.), this kind or POA is called “specific” or “special.” When we give someone the right to represent us in any or all of our affairs, this POA is called “general” or “durable.”

It is important to mention that as long as we continue to have psychological capacity and are willing to continue to be our own guardians (own 100% of the bundle of rights), we can terminate any POA we have appointed previously or designate another person to represent us as a “special” or “general” POA. Because of this, if an older patient—who is legally competent but physically unable to live on his (her) own— refuses to enter a long-term care facility, he (she) cannot be sent there against his will, even if the POA insists on it. Because of this, if the patient’s primary team strongly disagrees with this patient’s decision, his (her) “decision-making capacity” should be assessed and, if necessary, a competency hearing will need to be conducted. The court will then decide if this person is able (or unable) to handle his own affairs, and if the court decides that the person cannot be responsible to provide himself with food, health care, housing, and other necessities, the guardian (relative, friend, public administrator, etc.) will be appointed to do so.

Evaluating decision-making capacity

Determining “decision-making capacity” should not be confused with the legal concept of “competence.” We, physicians, often are called to evaluate a patient and give our opinion of the current level of this patient’s functioning (including his [her] decision-making capacity), and we—ourselves and a requesting team—need to be clear that it is merely our opinion and should be used as such. We need to remember that even if a patient is judged to be legally incompetent to handle financial affairs, he (she) might retain sufficient ability to make decisions about treatments.

We also need to remember that decision-making capacity can change, depending on medical conditions (severe anxiety, delirium), successful treatments, substance intoxication, etc. Because of this, we need to communicate to the requesting team that “decision-making ability” is situation-specific and time-specific, and that failure to make a decision on one issue should not be generalized to other aspects of the patient’s life.

Any physician can evaluate patient’s decision-making ability, but traditionally the psychiatry team is called to do so. It usually happens because the primary medical team needs us to provide “a third-party validation,” or because of the common misperception that only the psychiatric team can initiate a civil involuntary detention when necessary.

In any case, regardless of who evaluates the patient, specific points need to be addressed and the following questions need to be answered:

• Does the patient understand the nature of his (her) condition?

• Does the patient understand what treatment we are proposing or what he should do?

• Does the patient understand the consequences (good or bad) if he rejects our proposed action or treatment?

When information (discharge plan, treatment plan, etc.) is presented to patients, we should ask them to repeat it in their own words. We should not expect them to understand all of the technical aspects. We should consider patients’ intelligence level and their ability to communicate; if they can clearly verbalize their understanding of information and be consistent in their wish to continue with their decision, we have to declare that they have decision-making capability and able to proceed with their chosen treatment.

More matters that need to be mentioned

Restrictions on the patient. We need to remember that, even if a patient is thought to be able to make his own decisions, there may be some situations when he can be held in the hospital against his will. These usually are the cases when the patient is psychiatrically or medically unstable (unable to care of himself), but also if the patient is at risk of harming himself or others, subject of elder abuse, or suspected of being an abuser.

Restrictions on the practitioner. Even if the patient is determined to be lacking decision-making capacity, we, physicians, cannot perform tests, procedures, or do the placements without the patient’s agreement.

Informed consent doctrine is applicable in this case, and if performing a test or procedure is necessary (except life- or limb-saving emergencies, when doctrine of physician prerogative applies), or if there a disagreement in post-discharge placement, the emergency guardianship may need to be pursued.

Disclosure

Dr. Graypel reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Should the use of ‘endorse’ be endorsed in writing in psychiatry?

The word “endorse” often appears in the medical literature and is heard in oral presentations; psychiatrists use the term to mean that a person is reporting psychiatric symptoms or problems. However, such usage may be a stylistic catachresis—one that has the potential for misinterpretation or misunderstanding.

Finding ‘endorse’ in the psychiatric literature

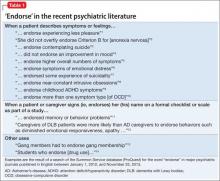

We conducted a literature search to identify instances of “endorse” in scholarly articles published in psychiatric journals between January 1, 2012, and November 25, 2013. Table 11-14 shows examples of typical uses of “endorse” in recent publications.

Even when “endorse” is used as a synonym for “report” or “describe,” use of the word in that context can seem out of place. We could not find any rationale in the medical literature for using “endorse” as a synonym for “report” or “describe.”

The definition of “endorse” in Merriam-Webster15 and Oxford Dictionaries16 includes:

• inscribing or signing a legal document, check, or bill

• approving or recommending an idea, product, or candidate.

We believe that using “endorse” in a psychiatric context could create confusion among medical trainees and professionals who are familiar with the correct meanings of the word.

Survey: Some residents use ‘endorse’ in oral presentations

We asked residents in the Department of Psychiatry at Drexel University College of Medicine to respond to a questionnaire regarding their understanding of the use of “endorse.” Their responses are summarized in Table 2.

What is wrong with using ‘endorse’? Except when “endorse” describes a patient formally affixing her (his) signature to a document for the purpose of (1) certification or (2) giving or showing one’s support for a cause, we think that use of the word in psychiatry is not in keeping with its formal, accepted definition. Furthermore, residents’ responses to our survey suggest that there is the danger of causing confusion in using the word“endorse” when “report” or “describe” is meant.

For example, if a patient “endorses” antisocial behavior, is she stating that she feels justified in exhibiting such behavior? Do students who “endorse” drug use approve of drug use? Another example: Youth who “endorse” gang membership have merely confirmed that they belonged to a gang at some time.

The intended meaning of “endorse” in these examples is probably closer to “admit” or “acknowledge.” The patient replies “yes” when the physician asks if she uses drugs or has had behavior problems; she is not necessarily recommending or approving these behaviors.

Usage is shifting. In the past, “complain” was common medical parlance for a patient’s report of symptoms or other health-related problems. In fact, medical, surgical, and psychiatric evaluations still begin with a “chief complaint” section. It’s possible that, because “complaint” might suggest that the patient is whining, the word fell out of favor in the medical lexicon and was replaced in the scholarly literature by the construction “the patient reports….”

Avoid jargon. Employ accurate terminology

We propose that “endorse,” like “complain,” is a cant of psychiatrists. We recommend that, when describing a patient’s statement or report of symptoms or experiences, practitioners should avoid “endorse” and write or say “report,” “express,” “exhibit,” or similar words. Using accurate terminology and avoiding imprecise or misleading jargon is not only linguistically appropriate but also can help avoid misunderstanding and improve patient care.

Acknowledgment

Diana Winters, Academic Publishing Services, Drexel University College of Medicine, provided editorial assistance in preparing the manuscript of this article and offered comment on the use of medical jargon.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Strauss GP, Gold JM. A new perspective on anhedonia in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(4):364-373.

2. Thomas JJ, Weigel TJ, Lawton RK, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of body image disturbance in a congenitally blind patient with anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(1):16-20.

3. Purcell B, Heisel MJ, Speice J, et al. Family connectedness moderates the association between living alone and suicide ideation in a clinical sample of adults 50 years and older. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(8):717-723.

4. Dakin EK, Areán P. Patient perspectives on the benefits of psychotherapy for late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(2):155-163.

5. Mezuk B, Lohman M, Dumenci, L, et al. Are depression and frailty overlapping syndromes in mid- and late-life? A latent variable analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(6):560-569.

6. Boindala NS, Tucker P, Trautman RP. “Culture and psychiatry”: a course for second-year psychiatry residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(1):46-50.

7. Henry A, Kisicki MD, Varley C. Efficacy and safety of antidepressant drug treatment in children and adolescents. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(12):1186-1193.

8. Rodriguez CI, Kegeles LS, Levinson A, et al. A randomized controlled crossover trial of ketamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder (abstract W7). Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;38:S317.

9. Whelan R, Garavan H. Fractionating the impulsivity construct in adolescence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(1):250-251.

10. Rück C, Larsson KJ, Mataix-Cols D. Predictors of medium and long-term outcome following capsulotomy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: one site may not fit all. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;22(6):406-414.

11. Mausbach BT, Chattillion EA, Roepke SK, et al. A comparison of psychosocial outcomes in elderly Alzheimer caregivers and noncaregivers. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(1):5-13.

12. Peavy GM, Salmon DP, Edland SD, et al. Neuropsychiatric features of frontal lobe dysfunction in autopsy-confirmed patients with lewy bodies and “pure” Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(6):509-519.

13. Coid JW, Ullrich S, Keers R, et al. Gang membership, violence, and psychiatric morbidity. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):985-993.

14. Choi D, Tolova V, Socha E, et al. Substance use and attitudes on professional conduct among medical students: a single-institution study. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(3):191-195.

15. Endorse. Merriam-Webster. http://www.merriam-webster. com/dictionary/endorse. Accessed January 14, 2014.

16. Endorse. Oxford Dictionaries. http://www.oxforddictionaries. com/definition/english/endorse. Accessed January 14, 2014.

The word “endorse” often appears in the medical literature and is heard in oral presentations; psychiatrists use the term to mean that a person is reporting psychiatric symptoms or problems. However, such usage may be a stylistic catachresis—one that has the potential for misinterpretation or misunderstanding.

Finding ‘endorse’ in the psychiatric literature

We conducted a literature search to identify instances of “endorse” in scholarly articles published in psychiatric journals between January 1, 2012, and November 25, 2013. Table 11-14 shows examples of typical uses of “endorse” in recent publications.

Even when “endorse” is used as a synonym for “report” or “describe,” use of the word in that context can seem out of place. We could not find any rationale in the medical literature for using “endorse” as a synonym for “report” or “describe.”

The definition of “endorse” in Merriam-Webster15 and Oxford Dictionaries16 includes:

• inscribing or signing a legal document, check, or bill

• approving or recommending an idea, product, or candidate.

We believe that using “endorse” in a psychiatric context could create confusion among medical trainees and professionals who are familiar with the correct meanings of the word.

Survey: Some residents use ‘endorse’ in oral presentations

We asked residents in the Department of Psychiatry at Drexel University College of Medicine to respond to a questionnaire regarding their understanding of the use of “endorse.” Their responses are summarized in Table 2.

What is wrong with using ‘endorse’? Except when “endorse” describes a patient formally affixing her (his) signature to a document for the purpose of (1) certification or (2) giving or showing one’s support for a cause, we think that use of the word in psychiatry is not in keeping with its formal, accepted definition. Furthermore, residents’ responses to our survey suggest that there is the danger of causing confusion in using the word“endorse” when “report” or “describe” is meant.

For example, if a patient “endorses” antisocial behavior, is she stating that she feels justified in exhibiting such behavior? Do students who “endorse” drug use approve of drug use? Another example: Youth who “endorse” gang membership have merely confirmed that they belonged to a gang at some time.

The intended meaning of “endorse” in these examples is probably closer to “admit” or “acknowledge.” The patient replies “yes” when the physician asks if she uses drugs or has had behavior problems; she is not necessarily recommending or approving these behaviors.

Usage is shifting. In the past, “complain” was common medical parlance for a patient’s report of symptoms or other health-related problems. In fact, medical, surgical, and psychiatric evaluations still begin with a “chief complaint” section. It’s possible that, because “complaint” might suggest that the patient is whining, the word fell out of favor in the medical lexicon and was replaced in the scholarly literature by the construction “the patient reports….”

Avoid jargon. Employ accurate terminology

We propose that “endorse,” like “complain,” is a cant of psychiatrists. We recommend that, when describing a patient’s statement or report of symptoms or experiences, practitioners should avoid “endorse” and write or say “report,” “express,” “exhibit,” or similar words. Using accurate terminology and avoiding imprecise or misleading jargon is not only linguistically appropriate but also can help avoid misunderstanding and improve patient care.

Acknowledgment

Diana Winters, Academic Publishing Services, Drexel University College of Medicine, provided editorial assistance in preparing the manuscript of this article and offered comment on the use of medical jargon.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

The word “endorse” often appears in the medical literature and is heard in oral presentations; psychiatrists use the term to mean that a person is reporting psychiatric symptoms or problems. However, such usage may be a stylistic catachresis—one that has the potential for misinterpretation or misunderstanding.

Finding ‘endorse’ in the psychiatric literature

We conducted a literature search to identify instances of “endorse” in scholarly articles published in psychiatric journals between January 1, 2012, and November 25, 2013. Table 11-14 shows examples of typical uses of “endorse” in recent publications.

Even when “endorse” is used as a synonym for “report” or “describe,” use of the word in that context can seem out of place. We could not find any rationale in the medical literature for using “endorse” as a synonym for “report” or “describe.”

The definition of “endorse” in Merriam-Webster15 and Oxford Dictionaries16 includes:

• inscribing or signing a legal document, check, or bill

• approving or recommending an idea, product, or candidate.

We believe that using “endorse” in a psychiatric context could create confusion among medical trainees and professionals who are familiar with the correct meanings of the word.

Survey: Some residents use ‘endorse’ in oral presentations

We asked residents in the Department of Psychiatry at Drexel University College of Medicine to respond to a questionnaire regarding their understanding of the use of “endorse.” Their responses are summarized in Table 2.

What is wrong with using ‘endorse’? Except when “endorse” describes a patient formally affixing her (his) signature to a document for the purpose of (1) certification or (2) giving or showing one’s support for a cause, we think that use of the word in psychiatry is not in keeping with its formal, accepted definition. Furthermore, residents’ responses to our survey suggest that there is the danger of causing confusion in using the word“endorse” when “report” or “describe” is meant.

For example, if a patient “endorses” antisocial behavior, is she stating that she feels justified in exhibiting such behavior? Do students who “endorse” drug use approve of drug use? Another example: Youth who “endorse” gang membership have merely confirmed that they belonged to a gang at some time.

The intended meaning of “endorse” in these examples is probably closer to “admit” or “acknowledge.” The patient replies “yes” when the physician asks if she uses drugs or has had behavior problems; she is not necessarily recommending or approving these behaviors.

Usage is shifting. In the past, “complain” was common medical parlance for a patient’s report of symptoms or other health-related problems. In fact, medical, surgical, and psychiatric evaluations still begin with a “chief complaint” section. It’s possible that, because “complaint” might suggest that the patient is whining, the word fell out of favor in the medical lexicon and was replaced in the scholarly literature by the construction “the patient reports….”

Avoid jargon. Employ accurate terminology

We propose that “endorse,” like “complain,” is a cant of psychiatrists. We recommend that, when describing a patient’s statement or report of symptoms or experiences, practitioners should avoid “endorse” and write or say “report,” “express,” “exhibit,” or similar words. Using accurate terminology and avoiding imprecise or misleading jargon is not only linguistically appropriate but also can help avoid misunderstanding and improve patient care.

Acknowledgment

Diana Winters, Academic Publishing Services, Drexel University College of Medicine, provided editorial assistance in preparing the manuscript of this article and offered comment on the use of medical jargon.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Strauss GP, Gold JM. A new perspective on anhedonia in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(4):364-373.

2. Thomas JJ, Weigel TJ, Lawton RK, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of body image disturbance in a congenitally blind patient with anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(1):16-20.

3. Purcell B, Heisel MJ, Speice J, et al. Family connectedness moderates the association between living alone and suicide ideation in a clinical sample of adults 50 years and older. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(8):717-723.

4. Dakin EK, Areán P. Patient perspectives on the benefits of psychotherapy for late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(2):155-163.

5. Mezuk B, Lohman M, Dumenci, L, et al. Are depression and frailty overlapping syndromes in mid- and late-life? A latent variable analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(6):560-569.

6. Boindala NS, Tucker P, Trautman RP. “Culture and psychiatry”: a course for second-year psychiatry residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(1):46-50.

7. Henry A, Kisicki MD, Varley C. Efficacy and safety of antidepressant drug treatment in children and adolescents. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(12):1186-1193.

8. Rodriguez CI, Kegeles LS, Levinson A, et al. A randomized controlled crossover trial of ketamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder (abstract W7). Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;38:S317.

9. Whelan R, Garavan H. Fractionating the impulsivity construct in adolescence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(1):250-251.

10. Rück C, Larsson KJ, Mataix-Cols D. Predictors of medium and long-term outcome following capsulotomy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: one site may not fit all. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;22(6):406-414.

11. Mausbach BT, Chattillion EA, Roepke SK, et al. A comparison of psychosocial outcomes in elderly Alzheimer caregivers and noncaregivers. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(1):5-13.

12. Peavy GM, Salmon DP, Edland SD, et al. Neuropsychiatric features of frontal lobe dysfunction in autopsy-confirmed patients with lewy bodies and “pure” Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(6):509-519.

13. Coid JW, Ullrich S, Keers R, et al. Gang membership, violence, and psychiatric morbidity. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):985-993.

14. Choi D, Tolova V, Socha E, et al. Substance use and attitudes on professional conduct among medical students: a single-institution study. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(3):191-195.

15. Endorse. Merriam-Webster. http://www.merriam-webster. com/dictionary/endorse. Accessed January 14, 2014.

16. Endorse. Oxford Dictionaries. http://www.oxforddictionaries. com/definition/english/endorse. Accessed January 14, 2014.

1. Strauss GP, Gold JM. A new perspective on anhedonia in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(4):364-373.

2. Thomas JJ, Weigel TJ, Lawton RK, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of body image disturbance in a congenitally blind patient with anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(1):16-20.

3. Purcell B, Heisel MJ, Speice J, et al. Family connectedness moderates the association between living alone and suicide ideation in a clinical sample of adults 50 years and older. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(8):717-723.

4. Dakin EK, Areán P. Patient perspectives on the benefits of psychotherapy for late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(2):155-163.

5. Mezuk B, Lohman M, Dumenci, L, et al. Are depression and frailty overlapping syndromes in mid- and late-life? A latent variable analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(6):560-569.

6. Boindala NS, Tucker P, Trautman RP. “Culture and psychiatry”: a course for second-year psychiatry residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(1):46-50.

7. Henry A, Kisicki MD, Varley C. Efficacy and safety of antidepressant drug treatment in children and adolescents. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(12):1186-1193.

8. Rodriguez CI, Kegeles LS, Levinson A, et al. A randomized controlled crossover trial of ketamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder (abstract W7). Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;38:S317.

9. Whelan R, Garavan H. Fractionating the impulsivity construct in adolescence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(1):250-251.

10. Rück C, Larsson KJ, Mataix-Cols D. Predictors of medium and long-term outcome following capsulotomy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: one site may not fit all. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;22(6):406-414.

11. Mausbach BT, Chattillion EA, Roepke SK, et al. A comparison of psychosocial outcomes in elderly Alzheimer caregivers and noncaregivers. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(1):5-13.

12. Peavy GM, Salmon DP, Edland SD, et al. Neuropsychiatric features of frontal lobe dysfunction in autopsy-confirmed patients with lewy bodies and “pure” Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(6):509-519.

13. Coid JW, Ullrich S, Keers R, et al. Gang membership, violence, and psychiatric morbidity. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):985-993.

14. Choi D, Tolova V, Socha E, et al. Substance use and attitudes on professional conduct among medical students: a single-institution study. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(3):191-195.

15. Endorse. Merriam-Webster. http://www.merriam-webster. com/dictionary/endorse. Accessed January 14, 2014.

16. Endorse. Oxford Dictionaries. http://www.oxforddictionaries. com/definition/english/endorse. Accessed January 14, 2014.

Discharging your patient: A complex process

Let me begin with a story.

A few years ago, when I was hoping to get into a psychiatry residency program, I did a month-long rotation in the intensive care unit (ICU) of a local hospital. One of our patients was a long-term resident of a nearby assisted living facility, who was treated for exacerbation of a chronic medical illness. Eventually this patient was stabilized to the point at which he could be discharged.

When the ICU physician decided to discharge this patient, he told the team that the man would need to be “sent back to a nursing home.” The social worker, assuming that the physician wanted to place the patient in a skilled nursing facility, spent several hours trying to place the man in one of the local facilities. When the patient’s daughter arrived to visit her father and began asking questions about why he was being placed in a nursing home, staff immediately realized that the physician had simply meant for him to go back “home”—that is, to the facility from which he had come and where he had been living for several years.

Being the only person in the ICU who was a licensed nursing home administrator, with more than 10 years experience in a long-term care, I should have pointed out this miscommunication or, at least, should have raised the question to clarify the physician’s intent. At the time, however, I wasn’t comfortable expressing my concern because I was “just an FMG observer” trying to stay on the attending’s good side.

I made a commitment to myself, however, to always talk about patients’ long-term care options and discharge planning algorithm with medical students, fellow residents, and other medical professionals I meet in my work. The following is an expression of that commitment.

Why focus on discharge when care is still underway?

Discharge planning usually begins on the first day of hospitalization. Before we are ready to discharge any patient, we, the physicians, usually have had many conversations with members of the multidisciplinary team and, always, with the patient and his (her) guardian(s). Why do we do all of this? The answer is simple: Physicians make the ultimate decision about what kind of environment (clinical, social, etc.) the patient is safe to be discharged to; after that decision is made, everything else is the patient’s choice. Our decision should be based on, first, global assessment of functioning—the ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental (non-essential) ADL—and, second, essential input from members of multidisciplinary team.

Here is an example to illustrate this point: If we (the multidisciplinary team) believe that a patient who has lived alone and, up to this point, was able to handle his own affairs, will not be safe if he is discharged to his home (based on observation of his overall daily functioning) but he refuses to be institutionalized, we can evaluate his competency and initiate a motion to obtain a temporary guardianship.

If, on the other hand, we think that a patient needs to be placed in a skilled nursing facility and he, being fully aware of his condition, agrees with the decision of the multidisciplinary team, we cannot place him in a facility of our choosing (if it is against his will). Rather, we must give him options of facilities with similar services that meet his needs and let him or his guardian select the facility in which he’s to be placed.

How do we decide on the best course?

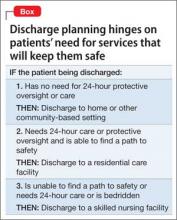

To choose what kind of environment a patient needs to be placed in after discharge, we can apply a simple algorithm (Box):

The patient does not need 24-hour protective oversight or needs some, but not 24-hour, care. Discharge him to a home-and community-based care setting—with arrangements for home health agency services or a home-modification program. The patient would either live independently or in a group home setting, depending on how much assistance he requires.

The patient does need 24-hour protective oversight and more than minimal assistance with ADL but doesn’t need 24-hour care, IV medication, etc.). In this case, the patient can be discharged to an assisted living or residential care facility, assuming that he is able to 1) find a so-called path to safety in an emergency (this why facilities are required to perform 1 fire drill per shift per month) and 2) afford rent, because Medicaid, Medicare, and many private insurance policies do not cover housing expenses (see “Keep financing in mind,” in the next section).

The patient is bed-bound or needs 24-hour treatment (eg, receives IV medication or needs total nursing care) or is not bed-bound but is unable to find a path to safety (eg, a person with dementia). This kind of patient must be placed in a skilled nursing facility

Keep financing in mind

The patient’s ability to pay, as well as having access to insurance or a financial assistance program, is a major contributing factor in discharge planning. All financial options need to be considered by the physicians leading the discharge planning team.

Neither Medicaid nor Medicare benefits are available to pay rent; these insurance programs pay for medical services only. Medicaid does provide some money for assistance with ADL in home- and community-based settings (such assistance is arranged through, and provided by, home health care agencies) and to Medicaid-eligible residents of an assisted living facility.

Medicaid covers 100% of a nursing home stay for an eligible resident. Medicare might cover the cost of skilled-nursing facility care if the placement falls under the criterion of an “episode of care.”

It is worth mentioning that some Veterans’ Administration money might be available to a veteran or his (her) surviving spouse for assistance with ADL in home- and community-based settings or if he (she) is institutionalized. Other local programs might provide eligible recipients with long-term care services; discharge social workers, as members of the multidisciplinary team, usually are resourceful at identifying such programs.

All in all, a complex project

Discharge planning is almost as important as the treatment given to the patient. It can be difficult to put all the pieces of the discharge plan together; sometimes, unclear disposition is the only reason a patient is kept in the hospital after being stabilized.

Above all, our ability to work with the multidisciplinary team and our knowledge of these simple steps will help us navigate our patients’ care plan successfully.

Disclosure

Dr. Graypel reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Let me begin with a story.

A few years ago, when I was hoping to get into a psychiatry residency program, I did a month-long rotation in the intensive care unit (ICU) of a local hospital. One of our patients was a long-term resident of a nearby assisted living facility, who was treated for exacerbation of a chronic medical illness. Eventually this patient was stabilized to the point at which he could be discharged.

When the ICU physician decided to discharge this patient, he told the team that the man would need to be “sent back to a nursing home.” The social worker, assuming that the physician wanted to place the patient in a skilled nursing facility, spent several hours trying to place the man in one of the local facilities. When the patient’s daughter arrived to visit her father and began asking questions about why he was being placed in a nursing home, staff immediately realized that the physician had simply meant for him to go back “home”—that is, to the facility from which he had come and where he had been living for several years.

Being the only person in the ICU who was a licensed nursing home administrator, with more than 10 years experience in a long-term care, I should have pointed out this miscommunication or, at least, should have raised the question to clarify the physician’s intent. At the time, however, I wasn’t comfortable expressing my concern because I was “just an FMG observer” trying to stay on the attending’s good side.

I made a commitment to myself, however, to always talk about patients’ long-term care options and discharge planning algorithm with medical students, fellow residents, and other medical professionals I meet in my work. The following is an expression of that commitment.

Why focus on discharge when care is still underway?

Discharge planning usually begins on the first day of hospitalization. Before we are ready to discharge any patient, we, the physicians, usually have had many conversations with members of the multidisciplinary team and, always, with the patient and his (her) guardian(s). Why do we do all of this? The answer is simple: Physicians make the ultimate decision about what kind of environment (clinical, social, etc.) the patient is safe to be discharged to; after that decision is made, everything else is the patient’s choice. Our decision should be based on, first, global assessment of functioning—the ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental (non-essential) ADL—and, second, essential input from members of multidisciplinary team.

Here is an example to illustrate this point: If we (the multidisciplinary team) believe that a patient who has lived alone and, up to this point, was able to handle his own affairs, will not be safe if he is discharged to his home (based on observation of his overall daily functioning) but he refuses to be institutionalized, we can evaluate his competency and initiate a motion to obtain a temporary guardianship.

If, on the other hand, we think that a patient needs to be placed in a skilled nursing facility and he, being fully aware of his condition, agrees with the decision of the multidisciplinary team, we cannot place him in a facility of our choosing (if it is against his will). Rather, we must give him options of facilities with similar services that meet his needs and let him or his guardian select the facility in which he’s to be placed.

How do we decide on the best course?

To choose what kind of environment a patient needs to be placed in after discharge, we can apply a simple algorithm (Box):

The patient does not need 24-hour protective oversight or needs some, but not 24-hour, care. Discharge him to a home-and community-based care setting—with arrangements for home health agency services or a home-modification program. The patient would either live independently or in a group home setting, depending on how much assistance he requires.

The patient does need 24-hour protective oversight and more than minimal assistance with ADL but doesn’t need 24-hour care, IV medication, etc.). In this case, the patient can be discharged to an assisted living or residential care facility, assuming that he is able to 1) find a so-called path to safety in an emergency (this why facilities are required to perform 1 fire drill per shift per month) and 2) afford rent, because Medicaid, Medicare, and many private insurance policies do not cover housing expenses (see “Keep financing in mind,” in the next section).

The patient is bed-bound or needs 24-hour treatment (eg, receives IV medication or needs total nursing care) or is not bed-bound but is unable to find a path to safety (eg, a person with dementia). This kind of patient must be placed in a skilled nursing facility

Keep financing in mind

The patient’s ability to pay, as well as having access to insurance or a financial assistance program, is a major contributing factor in discharge planning. All financial options need to be considered by the physicians leading the discharge planning team.

Neither Medicaid nor Medicare benefits are available to pay rent; these insurance programs pay for medical services only. Medicaid does provide some money for assistance with ADL in home- and community-based settings (such assistance is arranged through, and provided by, home health care agencies) and to Medicaid-eligible residents of an assisted living facility.

Medicaid covers 100% of a nursing home stay for an eligible resident. Medicare might cover the cost of skilled-nursing facility care if the placement falls under the criterion of an “episode of care.”

It is worth mentioning that some Veterans’ Administration money might be available to a veteran or his (her) surviving spouse for assistance with ADL in home- and community-based settings or if he (she) is institutionalized. Other local programs might provide eligible recipients with long-term care services; discharge social workers, as members of the multidisciplinary team, usually are resourceful at identifying such programs.

All in all, a complex project

Discharge planning is almost as important as the treatment given to the patient. It can be difficult to put all the pieces of the discharge plan together; sometimes, unclear disposition is the only reason a patient is kept in the hospital after being stabilized.

Above all, our ability to work with the multidisciplinary team and our knowledge of these simple steps will help us navigate our patients’ care plan successfully.

Disclosure

Dr. Graypel reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Let me begin with a story.

A few years ago, when I was hoping to get into a psychiatry residency program, I did a month-long rotation in the intensive care unit (ICU) of a local hospital. One of our patients was a long-term resident of a nearby assisted living facility, who was treated for exacerbation of a chronic medical illness. Eventually this patient was stabilized to the point at which he could be discharged.

When the ICU physician decided to discharge this patient, he told the team that the man would need to be “sent back to a nursing home.” The social worker, assuming that the physician wanted to place the patient in a skilled nursing facility, spent several hours trying to place the man in one of the local facilities. When the patient’s daughter arrived to visit her father and began asking questions about why he was being placed in a nursing home, staff immediately realized that the physician had simply meant for him to go back “home”—that is, to the facility from which he had come and where he had been living for several years.

Being the only person in the ICU who was a licensed nursing home administrator, with more than 10 years experience in a long-term care, I should have pointed out this miscommunication or, at least, should have raised the question to clarify the physician’s intent. At the time, however, I wasn’t comfortable expressing my concern because I was “just an FMG observer” trying to stay on the attending’s good side.

I made a commitment to myself, however, to always talk about patients’ long-term care options and discharge planning algorithm with medical students, fellow residents, and other medical professionals I meet in my work. The following is an expression of that commitment.

Why focus on discharge when care is still underway?

Discharge planning usually begins on the first day of hospitalization. Before we are ready to discharge any patient, we, the physicians, usually have had many conversations with members of the multidisciplinary team and, always, with the patient and his (her) guardian(s). Why do we do all of this? The answer is simple: Physicians make the ultimate decision about what kind of environment (clinical, social, etc.) the patient is safe to be discharged to; after that decision is made, everything else is the patient’s choice. Our decision should be based on, first, global assessment of functioning—the ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental (non-essential) ADL—and, second, essential input from members of multidisciplinary team.

Here is an example to illustrate this point: If we (the multidisciplinary team) believe that a patient who has lived alone and, up to this point, was able to handle his own affairs, will not be safe if he is discharged to his home (based on observation of his overall daily functioning) but he refuses to be institutionalized, we can evaluate his competency and initiate a motion to obtain a temporary guardianship.

If, on the other hand, we think that a patient needs to be placed in a skilled nursing facility and he, being fully aware of his condition, agrees with the decision of the multidisciplinary team, we cannot place him in a facility of our choosing (if it is against his will). Rather, we must give him options of facilities with similar services that meet his needs and let him or his guardian select the facility in which he’s to be placed.

How do we decide on the best course?

To choose what kind of environment a patient needs to be placed in after discharge, we can apply a simple algorithm (Box):

The patient does not need 24-hour protective oversight or needs some, but not 24-hour, care. Discharge him to a home-and community-based care setting—with arrangements for home health agency services or a home-modification program. The patient would either live independently or in a group home setting, depending on how much assistance he requires.

The patient does need 24-hour protective oversight and more than minimal assistance with ADL but doesn’t need 24-hour care, IV medication, etc.). In this case, the patient can be discharged to an assisted living or residential care facility, assuming that he is able to 1) find a so-called path to safety in an emergency (this why facilities are required to perform 1 fire drill per shift per month) and 2) afford rent, because Medicaid, Medicare, and many private insurance policies do not cover housing expenses (see “Keep financing in mind,” in the next section).

The patient is bed-bound or needs 24-hour treatment (eg, receives IV medication or needs total nursing care) or is not bed-bound but is unable to find a path to safety (eg, a person with dementia). This kind of patient must be placed in a skilled nursing facility

Keep financing in mind

The patient’s ability to pay, as well as having access to insurance or a financial assistance program, is a major contributing factor in discharge planning. All financial options need to be considered by the physicians leading the discharge planning team.

Neither Medicaid nor Medicare benefits are available to pay rent; these insurance programs pay for medical services only. Medicaid does provide some money for assistance with ADL in home- and community-based settings (such assistance is arranged through, and provided by, home health care agencies) and to Medicaid-eligible residents of an assisted living facility.

Medicaid covers 100% of a nursing home stay for an eligible resident. Medicare might cover the cost of skilled-nursing facility care if the placement falls under the criterion of an “episode of care.”

It is worth mentioning that some Veterans’ Administration money might be available to a veteran or his (her) surviving spouse for assistance with ADL in home- and community-based settings or if he (she) is institutionalized. Other local programs might provide eligible recipients with long-term care services; discharge social workers, as members of the multidisciplinary team, usually are resourceful at identifying such programs.

All in all, a complex project

Discharge planning is almost as important as the treatment given to the patient. It can be difficult to put all the pieces of the discharge plan together; sometimes, unclear disposition is the only reason a patient is kept in the hospital after being stabilized.

Above all, our ability to work with the multidisciplinary team and our knowledge of these simple steps will help us navigate our patients’ care plan successfully.

Disclosure

Dr. Graypel reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

In the drafty call room, a miracle unfolds

I’ve found that, as a resident in psychiatry, it’s rare to experience a moment of truly unbridled achievement while on call. Manning the revolving door of acute psychiatric admissions can be frustrating, not to mention unfulfilling. Maybe that’s why accomplishing a small miracle, you might say, while on call recently felt so satisfying.

Broken window = workplace woes

When working a 12-hour shift, especially overnight, it’s important to have an environment that is conducive to work. As fatigue and stress build, physical comfort means a lot.

Our problem finding physical comfort in the psychiatry resident call room at Saint Louis University was that a fixture on one of the windows had been broken for several years. You could push the window open, but you could not close it. If you called the janitor, he would come and close the window, but there was no guarantee when he’d show up. You might end up typing your notes all evening in the path of a chilly stream of air.

The residents had made a formal request to have the window repaired in a more permanent manner, but this resulted in it being bolted shut. That was a solution, but an imperfect one: Now we had no way to cool the call room in the winter, and it was beginning to smell of body odor.

The psychiatry resident call room is one of the nicer ones I’ve seen, but the building it occupies is a few decades old, and no replacement parts were available for the fixtures. We were stuck with a closed window—so I thought.

That miraculous morning

I was supervising an intern one Saturday, and she had not been paged yet to see patients. The call room was a mess; I telephoned housekeeping to have the beds changed, and maintenance to unclog the sink. When the maintenance man (I’ll call him “Tom”) arrived and fixed the sink, I praised him and asked him to take a look at the window.

“It’s my dream,” I said to no one in particular, “to have a window we can open and shut.”

I didn’t get angry or exert pressure. Tom explained to me that there were no replacement parts.

“Hmm… I see…,” I said.

To my delight, Tom seemed excited to be given a problem to solve. He left to pilfer parts from other windows on the floor.

No luck. The parts were all gone. Tom apologized and suggested we purchase a suction cup, with a cord attached, to pull the window closed.

“Good idea!” I said, thanking him as he went on his way.

But 2 hours later, our maintenance hero, Tom reappeared in the doorway.

“I’ve been thinking about your window all morning,” he announced.

Tom approached the window, unbolted it, and screwed one end of a chain into the frame, creating a makeshift handle. He demonstrated how to pull the window shut.

Voilà! A window we could open and close. The intern’s jaw dropped in amazement. I turned to dance a little jig.

Satisfaction

It’s important to be able to control the temperature in the call room; even more important to have a comfortable, healthy work environment. But knowing I can influence my surroundings to get what I need at work? That’s more important than anything else at all.

Disclosure

Dr. Jennings reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

I’ve found that, as a resident in psychiatry, it’s rare to experience a moment of truly unbridled achievement while on call. Manning the revolving door of acute psychiatric admissions can be frustrating, not to mention unfulfilling. Maybe that’s why accomplishing a small miracle, you might say, while on call recently felt so satisfying.

Broken window = workplace woes

When working a 12-hour shift, especially overnight, it’s important to have an environment that is conducive to work. As fatigue and stress build, physical comfort means a lot.

Our problem finding physical comfort in the psychiatry resident call room at Saint Louis University was that a fixture on one of the windows had been broken for several years. You could push the window open, but you could not close it. If you called the janitor, he would come and close the window, but there was no guarantee when he’d show up. You might end up typing your notes all evening in the path of a chilly stream of air.

The residents had made a formal request to have the window repaired in a more permanent manner, but this resulted in it being bolted shut. That was a solution, but an imperfect one: Now we had no way to cool the call room in the winter, and it was beginning to smell of body odor.

The psychiatry resident call room is one of the nicer ones I’ve seen, but the building it occupies is a few decades old, and no replacement parts were available for the fixtures. We were stuck with a closed window—so I thought.

That miraculous morning

I was supervising an intern one Saturday, and she had not been paged yet to see patients. The call room was a mess; I telephoned housekeeping to have the beds changed, and maintenance to unclog the sink. When the maintenance man (I’ll call him “Tom”) arrived and fixed the sink, I praised him and asked him to take a look at the window.

“It’s my dream,” I said to no one in particular, “to have a window we can open and shut.”

I didn’t get angry or exert pressure. Tom explained to me that there were no replacement parts.

“Hmm… I see…,” I said.

To my delight, Tom seemed excited to be given a problem to solve. He left to pilfer parts from other windows on the floor.

No luck. The parts were all gone. Tom apologized and suggested we purchase a suction cup, with a cord attached, to pull the window closed.

“Good idea!” I said, thanking him as he went on his way.

But 2 hours later, our maintenance hero, Tom reappeared in the doorway.

“I’ve been thinking about your window all morning,” he announced.

Tom approached the window, unbolted it, and screwed one end of a chain into the frame, creating a makeshift handle. He demonstrated how to pull the window shut.

Voilà! A window we could open and close. The intern’s jaw dropped in amazement. I turned to dance a little jig.

Satisfaction

It’s important to be able to control the temperature in the call room; even more important to have a comfortable, healthy work environment. But knowing I can influence my surroundings to get what I need at work? That’s more important than anything else at all.

Disclosure

Dr. Jennings reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

I’ve found that, as a resident in psychiatry, it’s rare to experience a moment of truly unbridled achievement while on call. Manning the revolving door of acute psychiatric admissions can be frustrating, not to mention unfulfilling. Maybe that’s why accomplishing a small miracle, you might say, while on call recently felt so satisfying.

Broken window = workplace woes

When working a 12-hour shift, especially overnight, it’s important to have an environment that is conducive to work. As fatigue and stress build, physical comfort means a lot.

Our problem finding physical comfort in the psychiatry resident call room at Saint Louis University was that a fixture on one of the windows had been broken for several years. You could push the window open, but you could not close it. If you called the janitor, he would come and close the window, but there was no guarantee when he’d show up. You might end up typing your notes all evening in the path of a chilly stream of air.