User login

Mentally ill and behind bars

The measure of a country’s greatness, Mahatma Gandhi said, should be based on how well it cares for its most vulnerable. Recently, I had the opportunity to work with members of a vulnerable population: men and women who have a mental illness and languish in jails and prisons around the country. My experience was eye-opening and heartbreaking.

Widespread incarceration of the mentally ill in a developed country such as the United States should be a national embarrassment. But this tragedy, which has reached an epidemic level, has been effectively shut out of the national conversation.

The problem has grown, and is enormous

By the estimate of the U.S. Department of Justice, more than one-half of people incarcerated in the United States are mentally ill and approximately 20% suffer from a serious mental illness.1,2 In fact, there are now 3 times as many mentally ill people in jail and prison as there are occupying psychiatric beds in hospitals.3 These numbers represent a considerable increase over the past 6 decades, and can be attributed to 2 major factors:

- A program of deinstitutionalization set in motion by the federal government in the 1950s called for shuttering of state psychiatric facilities around the country. This was a period of renewed national discourse on civil rights; for many people, the practice of institutionalization was considered a violation of civil rights. (Coincidentally, chlorpromazine was introduced about this time, and many experts believed that the drug would revolutionize outpatient management of psychiatric disorders.)

- More recently, heavy criminal penalties have been attached to convictions for possession and distribution of illegal substances—part of the government’s “war on drugs.”

As a consequence of these programs and policies, the United States has come full circle—routinely incarcerating the mentally ill as it did in the early 19th century, before reforms were initiated in response to the lobbying efforts of activist Dorothea Dix and her contemporaries.

My distressing, eye-opening experience

The time I spent with the incarcerated mentally ill was limited to a 6-month period at a county jail during residency. Yet the contrast between services provided to this population and those that are available to people in the community was immediately evident—and stark. The sheer number of adults in jails and prisons who require mental health care is such that the ratio of patients to psychiatrists, psychologists, and other mental health clinicians is shockingly skewed.

It does not take years of experience to figure out that a brief interview with an 18-year-old who is being jailed for the first time, has never seen a psychiatrist, and suffers panic attacks (or hallucinations, or suicidal thoughts) is a less-than-ideal clinical situation. Making that situation even more hazardous is that inmates have a high risk of suicide, particularly in the first 24 to 48 hours of incarceration.4

Other ethical issues arose during my stint in the correctional system: My patients frequently would be charged with prison-rule violations (there is evidence that mentally ill inmates are more likely to be charged with such violations2); on many such occasions, they would be placed in solitary confinement (“the hole”), a practice the United Nations has called “cruel, inhuman, and degrading: for the mentally ill5 and that, in turn, exacerbates the inmate’s psychiatric illness.6-11

Last, there are restrictions on the types of formulations of medications that can be prescribed, involuntary treatment, and other critical aspects of care that make the experience of providing care in this system frustrating for mental health providers.

Are there solutions?

One way to tackle this crisis might be to insert more psychiatrists and psychologists into the correctional system. A more sensible approach, however, would be to tackle the root cause and divert the mentally ill away from incarceration and into treatment—moving from a model of retribution and incapacitation to one of rehabilitation. For example:

- Several counties nationwide have adopted diversion programs that include so-called mental health courts and drug courts, with encouraging results12

- Police departments are establishing Crisis Intervention Teams

- Assisted outpatient treatment programs are growing in popularity.

Far more needs to be done, however. In the absence of a national debate on the problem of the incarcerated mentally ill, there is real risk that this population will continue to be ignored and that our mental health care infrastructure will remain inadequate for meeting their need for services.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Psychiatric services in jails and prisons: a task force report of the American Psychiatric Association. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000:XIX.

2. U.S. Department of Justice. Bureau of Justice Statistics: special report. Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mhppji.pdf. Updated December 14, 2006. Accessed April 8, 2016.|

3. Torrey FE, Kennard AD, Eslinger D, et al. More mentally ill persons are in jails and prisons than hospitals: a survey of the states. http://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/storage/documents/final_jails_v_hospitals_study.pdf. Published May 2010. Accessed April 8, 2016.

4. U.S. Department of Justice. National study of jail suicide: 20 years later. http://static.nicic.gov/Library/024308.pdf. Published April 2010. Accessed April 8, 2016.

5. Méndez JE. Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. http://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Torture/SRTorture/Pages/SRTortureIndex.aspx. Published 2011. Accessed April 8, 2016.

6. Daniel AE. Preventing suicide in prison: a collaborative responsibility of administrative, custodial, and clinical staff. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2006;34(2):165-175.

7. White TW, Schimmel DJ, Frickey R. A comprehensive analysis of suicide in federal prisons: a fifteen-year review. J Correct Health Care. 2002;9(3):321-345.

8. Smith PS. The effects of solitary confinement on prison inmates: a brief history and review of the literature, crime and justice. Crime and Justice. 2006;34(1):441-528.

9. Grassian S. Psychopathological effects of solitary confinement. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140(11):1450-1454.

10. Patterson RF, Hughes K. Review of completed suicides in the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, 1999 to 2004. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(6):676-682.

11. Kaba F, Lewis A, Glowa-Kollisch S, et al. Solitary confinement and risk of self-harm among jail inmates. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):442-447.

12. McNiel DE, Binder RL. Effectiveness of a mental health court in reducing criminal recidivism and violence. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(9):1395-1403.

The measure of a country’s greatness, Mahatma Gandhi said, should be based on how well it cares for its most vulnerable. Recently, I had the opportunity to work with members of a vulnerable population: men and women who have a mental illness and languish in jails and prisons around the country. My experience was eye-opening and heartbreaking.

Widespread incarceration of the mentally ill in a developed country such as the United States should be a national embarrassment. But this tragedy, which has reached an epidemic level, has been effectively shut out of the national conversation.

The problem has grown, and is enormous

By the estimate of the U.S. Department of Justice, more than one-half of people incarcerated in the United States are mentally ill and approximately 20% suffer from a serious mental illness.1,2 In fact, there are now 3 times as many mentally ill people in jail and prison as there are occupying psychiatric beds in hospitals.3 These numbers represent a considerable increase over the past 6 decades, and can be attributed to 2 major factors:

- A program of deinstitutionalization set in motion by the federal government in the 1950s called for shuttering of state psychiatric facilities around the country. This was a period of renewed national discourse on civil rights; for many people, the practice of institutionalization was considered a violation of civil rights. (Coincidentally, chlorpromazine was introduced about this time, and many experts believed that the drug would revolutionize outpatient management of psychiatric disorders.)

- More recently, heavy criminal penalties have been attached to convictions for possession and distribution of illegal substances—part of the government’s “war on drugs.”

As a consequence of these programs and policies, the United States has come full circle—routinely incarcerating the mentally ill as it did in the early 19th century, before reforms were initiated in response to the lobbying efforts of activist Dorothea Dix and her contemporaries.

My distressing, eye-opening experience

The time I spent with the incarcerated mentally ill was limited to a 6-month period at a county jail during residency. Yet the contrast between services provided to this population and those that are available to people in the community was immediately evident—and stark. The sheer number of adults in jails and prisons who require mental health care is such that the ratio of patients to psychiatrists, psychologists, and other mental health clinicians is shockingly skewed.

It does not take years of experience to figure out that a brief interview with an 18-year-old who is being jailed for the first time, has never seen a psychiatrist, and suffers panic attacks (or hallucinations, or suicidal thoughts) is a less-than-ideal clinical situation. Making that situation even more hazardous is that inmates have a high risk of suicide, particularly in the first 24 to 48 hours of incarceration.4

Other ethical issues arose during my stint in the correctional system: My patients frequently would be charged with prison-rule violations (there is evidence that mentally ill inmates are more likely to be charged with such violations2); on many such occasions, they would be placed in solitary confinement (“the hole”), a practice the United Nations has called “cruel, inhuman, and degrading: for the mentally ill5 and that, in turn, exacerbates the inmate’s psychiatric illness.6-11

Last, there are restrictions on the types of formulations of medications that can be prescribed, involuntary treatment, and other critical aspects of care that make the experience of providing care in this system frustrating for mental health providers.

Are there solutions?

One way to tackle this crisis might be to insert more psychiatrists and psychologists into the correctional system. A more sensible approach, however, would be to tackle the root cause and divert the mentally ill away from incarceration and into treatment—moving from a model of retribution and incapacitation to one of rehabilitation. For example:

- Several counties nationwide have adopted diversion programs that include so-called mental health courts and drug courts, with encouraging results12

- Police departments are establishing Crisis Intervention Teams

- Assisted outpatient treatment programs are growing in popularity.

Far more needs to be done, however. In the absence of a national debate on the problem of the incarcerated mentally ill, there is real risk that this population will continue to be ignored and that our mental health care infrastructure will remain inadequate for meeting their need for services.

The measure of a country’s greatness, Mahatma Gandhi said, should be based on how well it cares for its most vulnerable. Recently, I had the opportunity to work with members of a vulnerable population: men and women who have a mental illness and languish in jails and prisons around the country. My experience was eye-opening and heartbreaking.

Widespread incarceration of the mentally ill in a developed country such as the United States should be a national embarrassment. But this tragedy, which has reached an epidemic level, has been effectively shut out of the national conversation.

The problem has grown, and is enormous

By the estimate of the U.S. Department of Justice, more than one-half of people incarcerated in the United States are mentally ill and approximately 20% suffer from a serious mental illness.1,2 In fact, there are now 3 times as many mentally ill people in jail and prison as there are occupying psychiatric beds in hospitals.3 These numbers represent a considerable increase over the past 6 decades, and can be attributed to 2 major factors:

- A program of deinstitutionalization set in motion by the federal government in the 1950s called for shuttering of state psychiatric facilities around the country. This was a period of renewed national discourse on civil rights; for many people, the practice of institutionalization was considered a violation of civil rights. (Coincidentally, chlorpromazine was introduced about this time, and many experts believed that the drug would revolutionize outpatient management of psychiatric disorders.)

- More recently, heavy criminal penalties have been attached to convictions for possession and distribution of illegal substances—part of the government’s “war on drugs.”

As a consequence of these programs and policies, the United States has come full circle—routinely incarcerating the mentally ill as it did in the early 19th century, before reforms were initiated in response to the lobbying efforts of activist Dorothea Dix and her contemporaries.

My distressing, eye-opening experience

The time I spent with the incarcerated mentally ill was limited to a 6-month period at a county jail during residency. Yet the contrast between services provided to this population and those that are available to people in the community was immediately evident—and stark. The sheer number of adults in jails and prisons who require mental health care is such that the ratio of patients to psychiatrists, psychologists, and other mental health clinicians is shockingly skewed.

It does not take years of experience to figure out that a brief interview with an 18-year-old who is being jailed for the first time, has never seen a psychiatrist, and suffers panic attacks (or hallucinations, or suicidal thoughts) is a less-than-ideal clinical situation. Making that situation even more hazardous is that inmates have a high risk of suicide, particularly in the first 24 to 48 hours of incarceration.4

Other ethical issues arose during my stint in the correctional system: My patients frequently would be charged with prison-rule violations (there is evidence that mentally ill inmates are more likely to be charged with such violations2); on many such occasions, they would be placed in solitary confinement (“the hole”), a practice the United Nations has called “cruel, inhuman, and degrading: for the mentally ill5 and that, in turn, exacerbates the inmate’s psychiatric illness.6-11

Last, there are restrictions on the types of formulations of medications that can be prescribed, involuntary treatment, and other critical aspects of care that make the experience of providing care in this system frustrating for mental health providers.

Are there solutions?

One way to tackle this crisis might be to insert more psychiatrists and psychologists into the correctional system. A more sensible approach, however, would be to tackle the root cause and divert the mentally ill away from incarceration and into treatment—moving from a model of retribution and incapacitation to one of rehabilitation. For example:

- Several counties nationwide have adopted diversion programs that include so-called mental health courts and drug courts, with encouraging results12

- Police departments are establishing Crisis Intervention Teams

- Assisted outpatient treatment programs are growing in popularity.

Far more needs to be done, however. In the absence of a national debate on the problem of the incarcerated mentally ill, there is real risk that this population will continue to be ignored and that our mental health care infrastructure will remain inadequate for meeting their need for services.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Psychiatric services in jails and prisons: a task force report of the American Psychiatric Association. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000:XIX.

2. U.S. Department of Justice. Bureau of Justice Statistics: special report. Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mhppji.pdf. Updated December 14, 2006. Accessed April 8, 2016.|

3. Torrey FE, Kennard AD, Eslinger D, et al. More mentally ill persons are in jails and prisons than hospitals: a survey of the states. http://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/storage/documents/final_jails_v_hospitals_study.pdf. Published May 2010. Accessed April 8, 2016.

4. U.S. Department of Justice. National study of jail suicide: 20 years later. http://static.nicic.gov/Library/024308.pdf. Published April 2010. Accessed April 8, 2016.

5. Méndez JE. Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. http://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Torture/SRTorture/Pages/SRTortureIndex.aspx. Published 2011. Accessed April 8, 2016.

6. Daniel AE. Preventing suicide in prison: a collaborative responsibility of administrative, custodial, and clinical staff. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2006;34(2):165-175.

7. White TW, Schimmel DJ, Frickey R. A comprehensive analysis of suicide in federal prisons: a fifteen-year review. J Correct Health Care. 2002;9(3):321-345.

8. Smith PS. The effects of solitary confinement on prison inmates: a brief history and review of the literature, crime and justice. Crime and Justice. 2006;34(1):441-528.

9. Grassian S. Psychopathological effects of solitary confinement. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140(11):1450-1454.

10. Patterson RF, Hughes K. Review of completed suicides in the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, 1999 to 2004. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(6):676-682.

11. Kaba F, Lewis A, Glowa-Kollisch S, et al. Solitary confinement and risk of self-harm among jail inmates. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):442-447.

12. McNiel DE, Binder RL. Effectiveness of a mental health court in reducing criminal recidivism and violence. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(9):1395-1403.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Psychiatric services in jails and prisons: a task force report of the American Psychiatric Association. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000:XIX.

2. U.S. Department of Justice. Bureau of Justice Statistics: special report. Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mhppji.pdf. Updated December 14, 2006. Accessed April 8, 2016.|

3. Torrey FE, Kennard AD, Eslinger D, et al. More mentally ill persons are in jails and prisons than hospitals: a survey of the states. http://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/storage/documents/final_jails_v_hospitals_study.pdf. Published May 2010. Accessed April 8, 2016.

4. U.S. Department of Justice. National study of jail suicide: 20 years later. http://static.nicic.gov/Library/024308.pdf. Published April 2010. Accessed April 8, 2016.

5. Méndez JE. Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. http://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Torture/SRTorture/Pages/SRTortureIndex.aspx. Published 2011. Accessed April 8, 2016.

6. Daniel AE. Preventing suicide in prison: a collaborative responsibility of administrative, custodial, and clinical staff. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2006;34(2):165-175.

7. White TW, Schimmel DJ, Frickey R. A comprehensive analysis of suicide in federal prisons: a fifteen-year review. J Correct Health Care. 2002;9(3):321-345.

8. Smith PS. The effects of solitary confinement on prison inmates: a brief history and review of the literature, crime and justice. Crime and Justice. 2006;34(1):441-528.

9. Grassian S. Psychopathological effects of solitary confinement. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140(11):1450-1454.

10. Patterson RF, Hughes K. Review of completed suicides in the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, 1999 to 2004. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(6):676-682.

11. Kaba F, Lewis A, Glowa-Kollisch S, et al. Solitary confinement and risk of self-harm among jail inmates. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):442-447.

12. McNiel DE, Binder RL. Effectiveness of a mental health court in reducing criminal recidivism and violence. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(9):1395-1403.

Don’t assume that psychiatric patients lack capacity to make decisions about care

Some practitioners of medicine—including psychiatrists—might equate “psychosis” with incapacity, but that isn’t necessarily true. Even patients who, by most measures, are deemed psychotic might be capable of making wise and thoughtful decisions about their life. The case I describe in this article demonstrates that fact.

While rotating on a busy consultation service, I was asked to evaluate the capacity of a woman who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia and was being seen for worsening auditory hallucinations and progressive weight loss. She had a complicated medical course that eventually led to multiple requests to the consult team for a capacity evaluation.

The question of capacity in this patient, and in the psychiatric population generally, motivated me to review the literature, because the assumption by many on the medical teams involved in this patient’s care was that psychiatric patients do not have the capacity to participate in their own care. My goal here is to clarify the misconceptions in regard to this situation.

CASE REPORT

Schizophrenia, weight loss, back pain

Ms. V, age 67, a resident of a group home for the past 6 years, was brought to the emergency department (ED) because of weight loss and auditory hallucinations that had developed during the past few months. She had a history of paranoid schizophrenia that included several psychiatric hospitalizations but no known medical history.

The patient appeared cachectic and dehydrated. When approached, she was pleasant and reported hearing voices of the “devil.”

“They are not scary,” she confided. “They talk to me about art and literature.”

Over the past 6 months, Ms. V had lost 60 lb; she was now bedridden because of back pain. Collateral information obtained from staff members at the group home indicated that she had refused to get out of bed, and only intermittently took her medications or ate meals during the past few months. In general, however, she had been relatively stable over the course of her psychiatric illness, was adherent to psychiatric treatment, and had had no psychiatric hospitalizations in the past 3 decades.

Ominous development. Although the ED staff was convinced that Ms. V needed psychiatric admission, we (the consult team) first requested a detailed medical workup, including imaging studies. A CT scan showed multiple metastatic foci throughout her spine. She was admitted to the medical service.

Respiratory distress developed; her condition deteriorated. Numerous capacity consults were requested because she refused a medical workup or to sign do-not-resuscitate and do-not-intubate orders. Each time an evaluation was performed, Ms. V was deemed by various clinicians on the consult service to have decision-making capacity.

The patient grew unhappy with the staff’s insistence that she undergo more tests regardless of her stated wishes. The palliative care service determined that further workup would not benefit her medically: Ms. V’s condition would be grave and her prognosis poor regardless of what treatment she received.

The medical team continued to believe that, because that this patient had a mental illness and was actively hallucinating, she did not have the capacity to refuse any proposed treatments and tests.

What is capacity?

Capacity is an assessment of a person’s ability to make rational decisions. This includes the ability to understand, appreciate, and manipulate information in reaching such decisions. Determining whether a patient has the capacity to accept or refuse treatment is a medical decision that any physician can make; however, consultation−liaison psychiatrists are the experts who often are involved in this activity, particularly in patients who have a psychiatric comorbidity.

Capacity is evaluated by assessing 4 standards; that is, whether a patient can:

- communicate choice about proposed treatment

- understand her (his) medical situation

- appreciate the situation and its consequences

- manipulate information to reach a rational decision.1-3

- manipulate information to reach a rational decision.

CASE REPORT continued

Although Ms. V’s health was deteriorating and her auditory hallucinations were becoming worse, she appeared insightful about her medical problems, understood her prognosis, and wanted comfort care. She understood that having multiple metastases meant a poor prognosis, and that a biopsy might yield a medical diagnosis. She stated, “If it were caught earlier and I was better able to tolerate treatment, it would make sense to know for sure, but now it doesn’t make sense. I just want to have no pain in my end.”

Misconceptions

In a study by Ganzini et al,4,5 395 consultation−liaison psychiatrists, geriatricians, and geriatric psychologists responded to a survey in which they rated types of misunderstandings by clinicians who refer patients for assessment of decision-making capacity. Seventy percent reported that it is common that, when a patient has a mental illness such as schizophrenia, practitioners think that the patient lacks capacity to make medical decisions. However, results of a meta-analysis by Jeste et al,6 in which the magnitude of impairment of decisional capacity in patients with schizophrenia was assessed in comparison to that of normal subjects, suggest that the presence of schizophrenia does not necessarily mean the patient has impaired capacity.

Voluntary participation in research. Many patients with schizophrenia volunteer to participate in clinical trials even when they are acutely psychotic and admitted to a psychiatric hospital. Given the importance placed on participants’ voluntary informed consent as a prerequisite for ethical conduct of research, the cognitive and emotional impairments associated with schizophrenia raise questions about patients’ capacity to consent.

As is true in other areas of functional capacity, the ability of patients with schizophrenia to make competent decisions relates more to their overall cognitive functioning than to the presence or absence of specific symptoms of the disorder.7 Documentation of longitudinal consent-related abilities among research participants with schizophrenia in the long-term Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness study indicated that most participants had stable or improved consent-related abilities. Although almost 25% of participants experienced substantial worsening, only 4% fell below the study’s capacity threshold for enrollment.8

What I learned from Ms. V

A diagnosis of schizophrenia does not automatically render a person unable to make decisions about medical care. Even patients who have severe mental illness might have significant intact areas of reality testing. Ethically, it is important to at least consider that the chronically mentally ill can understand treatment options and express consistent choices.

Healthcare providers might tend to exclude psychiatric patients from end-of-life decisions because they (1) are worried about the emotional fragility of such patients and (2) assume that patients lack capacity to participate in making such important decisions. The case presented here is an example of a patient with a severe psychiatric diagnosis being able to participate in her care despite her mental state.

1. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(25):1635-1638.

2. Leo RJ. Competency and the capacity to make treatment decisions: a primer for primary care physicians. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;1(5):131-141.

3. White MM, Lofwall MR. Challenges of the capacity evaluation for the consultation-liaison psychiatrist. J Psychiatr Pract. 2015;21(2):160-170.

4. Ganzini L, Volicer L, Nelson W, et al. Pitfalls in assessment of decision-making capacity. Psychosomatics. 2003;44(3):237-243.

5. Ganzini L, Volicer L, Nelson WA, et al. Ten myths about decision-making capacity. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2005;6(3):S100-S104.

6. Jeste DV, Depp CA, Palmer BW. Magnitude of impairment in decisional capacity in people with schizophrenia compared to normal subjects: an overview. Schizophr Bull. 2005;32(1):121-128.

7. Appelbaum PS. Decisional capacity of patients with schizophrenia to consent to research: taking stock. Schizophr Bull. 2005;32(1):22-25.

8. Stroup TS, Appelbaum PS, Gu H, et al. Longitudinal consent-related abilities among research participants with schizophrenia: results from the CATIE study. Schizophr Res. 2011;130(1-3):47-52.

Some practitioners of medicine—including psychiatrists—might equate “psychosis” with incapacity, but that isn’t necessarily true. Even patients who, by most measures, are deemed psychotic might be capable of making wise and thoughtful decisions about their life. The case I describe in this article demonstrates that fact.

While rotating on a busy consultation service, I was asked to evaluate the capacity of a woman who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia and was being seen for worsening auditory hallucinations and progressive weight loss. She had a complicated medical course that eventually led to multiple requests to the consult team for a capacity evaluation.

The question of capacity in this patient, and in the psychiatric population generally, motivated me to review the literature, because the assumption by many on the medical teams involved in this patient’s care was that psychiatric patients do not have the capacity to participate in their own care. My goal here is to clarify the misconceptions in regard to this situation.

CASE REPORT

Schizophrenia, weight loss, back pain

Ms. V, age 67, a resident of a group home for the past 6 years, was brought to the emergency department (ED) because of weight loss and auditory hallucinations that had developed during the past few months. She had a history of paranoid schizophrenia that included several psychiatric hospitalizations but no known medical history.

The patient appeared cachectic and dehydrated. When approached, she was pleasant and reported hearing voices of the “devil.”

“They are not scary,” she confided. “They talk to me about art and literature.”

Over the past 6 months, Ms. V had lost 60 lb; she was now bedridden because of back pain. Collateral information obtained from staff members at the group home indicated that she had refused to get out of bed, and only intermittently took her medications or ate meals during the past few months. In general, however, she had been relatively stable over the course of her psychiatric illness, was adherent to psychiatric treatment, and had had no psychiatric hospitalizations in the past 3 decades.

Ominous development. Although the ED staff was convinced that Ms. V needed psychiatric admission, we (the consult team) first requested a detailed medical workup, including imaging studies. A CT scan showed multiple metastatic foci throughout her spine. She was admitted to the medical service.

Respiratory distress developed; her condition deteriorated. Numerous capacity consults were requested because she refused a medical workup or to sign do-not-resuscitate and do-not-intubate orders. Each time an evaluation was performed, Ms. V was deemed by various clinicians on the consult service to have decision-making capacity.

The patient grew unhappy with the staff’s insistence that she undergo more tests regardless of her stated wishes. The palliative care service determined that further workup would not benefit her medically: Ms. V’s condition would be grave and her prognosis poor regardless of what treatment she received.

The medical team continued to believe that, because that this patient had a mental illness and was actively hallucinating, she did not have the capacity to refuse any proposed treatments and tests.

What is capacity?

Capacity is an assessment of a person’s ability to make rational decisions. This includes the ability to understand, appreciate, and manipulate information in reaching such decisions. Determining whether a patient has the capacity to accept or refuse treatment is a medical decision that any physician can make; however, consultation−liaison psychiatrists are the experts who often are involved in this activity, particularly in patients who have a psychiatric comorbidity.

Capacity is evaluated by assessing 4 standards; that is, whether a patient can:

- communicate choice about proposed treatment

- understand her (his) medical situation

- appreciate the situation and its consequences

- manipulate information to reach a rational decision.1-3

- manipulate information to reach a rational decision.

CASE REPORT continued

Although Ms. V’s health was deteriorating and her auditory hallucinations were becoming worse, she appeared insightful about her medical problems, understood her prognosis, and wanted comfort care. She understood that having multiple metastases meant a poor prognosis, and that a biopsy might yield a medical diagnosis. She stated, “If it were caught earlier and I was better able to tolerate treatment, it would make sense to know for sure, but now it doesn’t make sense. I just want to have no pain in my end.”

Misconceptions

In a study by Ganzini et al,4,5 395 consultation−liaison psychiatrists, geriatricians, and geriatric psychologists responded to a survey in which they rated types of misunderstandings by clinicians who refer patients for assessment of decision-making capacity. Seventy percent reported that it is common that, when a patient has a mental illness such as schizophrenia, practitioners think that the patient lacks capacity to make medical decisions. However, results of a meta-analysis by Jeste et al,6 in which the magnitude of impairment of decisional capacity in patients with schizophrenia was assessed in comparison to that of normal subjects, suggest that the presence of schizophrenia does not necessarily mean the patient has impaired capacity.

Voluntary participation in research. Many patients with schizophrenia volunteer to participate in clinical trials even when they are acutely psychotic and admitted to a psychiatric hospital. Given the importance placed on participants’ voluntary informed consent as a prerequisite for ethical conduct of research, the cognitive and emotional impairments associated with schizophrenia raise questions about patients’ capacity to consent.

As is true in other areas of functional capacity, the ability of patients with schizophrenia to make competent decisions relates more to their overall cognitive functioning than to the presence or absence of specific symptoms of the disorder.7 Documentation of longitudinal consent-related abilities among research participants with schizophrenia in the long-term Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness study indicated that most participants had stable or improved consent-related abilities. Although almost 25% of participants experienced substantial worsening, only 4% fell below the study’s capacity threshold for enrollment.8

What I learned from Ms. V

A diagnosis of schizophrenia does not automatically render a person unable to make decisions about medical care. Even patients who have severe mental illness might have significant intact areas of reality testing. Ethically, it is important to at least consider that the chronically mentally ill can understand treatment options and express consistent choices.

Healthcare providers might tend to exclude psychiatric patients from end-of-life decisions because they (1) are worried about the emotional fragility of such patients and (2) assume that patients lack capacity to participate in making such important decisions. The case presented here is an example of a patient with a severe psychiatric diagnosis being able to participate in her care despite her mental state.

Some practitioners of medicine—including psychiatrists—might equate “psychosis” with incapacity, but that isn’t necessarily true. Even patients who, by most measures, are deemed psychotic might be capable of making wise and thoughtful decisions about their life. The case I describe in this article demonstrates that fact.

While rotating on a busy consultation service, I was asked to evaluate the capacity of a woman who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia and was being seen for worsening auditory hallucinations and progressive weight loss. She had a complicated medical course that eventually led to multiple requests to the consult team for a capacity evaluation.

The question of capacity in this patient, and in the psychiatric population generally, motivated me to review the literature, because the assumption by many on the medical teams involved in this patient’s care was that psychiatric patients do not have the capacity to participate in their own care. My goal here is to clarify the misconceptions in regard to this situation.

CASE REPORT

Schizophrenia, weight loss, back pain

Ms. V, age 67, a resident of a group home for the past 6 years, was brought to the emergency department (ED) because of weight loss and auditory hallucinations that had developed during the past few months. She had a history of paranoid schizophrenia that included several psychiatric hospitalizations but no known medical history.

The patient appeared cachectic and dehydrated. When approached, she was pleasant and reported hearing voices of the “devil.”

“They are not scary,” she confided. “They talk to me about art and literature.”

Over the past 6 months, Ms. V had lost 60 lb; she was now bedridden because of back pain. Collateral information obtained from staff members at the group home indicated that she had refused to get out of bed, and only intermittently took her medications or ate meals during the past few months. In general, however, she had been relatively stable over the course of her psychiatric illness, was adherent to psychiatric treatment, and had had no psychiatric hospitalizations in the past 3 decades.

Ominous development. Although the ED staff was convinced that Ms. V needed psychiatric admission, we (the consult team) first requested a detailed medical workup, including imaging studies. A CT scan showed multiple metastatic foci throughout her spine. She was admitted to the medical service.

Respiratory distress developed; her condition deteriorated. Numerous capacity consults were requested because she refused a medical workup or to sign do-not-resuscitate and do-not-intubate orders. Each time an evaluation was performed, Ms. V was deemed by various clinicians on the consult service to have decision-making capacity.

The patient grew unhappy with the staff’s insistence that she undergo more tests regardless of her stated wishes. The palliative care service determined that further workup would not benefit her medically: Ms. V’s condition would be grave and her prognosis poor regardless of what treatment she received.

The medical team continued to believe that, because that this patient had a mental illness and was actively hallucinating, she did not have the capacity to refuse any proposed treatments and tests.

What is capacity?

Capacity is an assessment of a person’s ability to make rational decisions. This includes the ability to understand, appreciate, and manipulate information in reaching such decisions. Determining whether a patient has the capacity to accept or refuse treatment is a medical decision that any physician can make; however, consultation−liaison psychiatrists are the experts who often are involved in this activity, particularly in patients who have a psychiatric comorbidity.

Capacity is evaluated by assessing 4 standards; that is, whether a patient can:

- communicate choice about proposed treatment

- understand her (his) medical situation

- appreciate the situation and its consequences

- manipulate information to reach a rational decision.1-3

- manipulate information to reach a rational decision.

CASE REPORT continued

Although Ms. V’s health was deteriorating and her auditory hallucinations were becoming worse, she appeared insightful about her medical problems, understood her prognosis, and wanted comfort care. She understood that having multiple metastases meant a poor prognosis, and that a biopsy might yield a medical diagnosis. She stated, “If it were caught earlier and I was better able to tolerate treatment, it would make sense to know for sure, but now it doesn’t make sense. I just want to have no pain in my end.”

Misconceptions

In a study by Ganzini et al,4,5 395 consultation−liaison psychiatrists, geriatricians, and geriatric psychologists responded to a survey in which they rated types of misunderstandings by clinicians who refer patients for assessment of decision-making capacity. Seventy percent reported that it is common that, when a patient has a mental illness such as schizophrenia, practitioners think that the patient lacks capacity to make medical decisions. However, results of a meta-analysis by Jeste et al,6 in which the magnitude of impairment of decisional capacity in patients with schizophrenia was assessed in comparison to that of normal subjects, suggest that the presence of schizophrenia does not necessarily mean the patient has impaired capacity.

Voluntary participation in research. Many patients with schizophrenia volunteer to participate in clinical trials even when they are acutely psychotic and admitted to a psychiatric hospital. Given the importance placed on participants’ voluntary informed consent as a prerequisite for ethical conduct of research, the cognitive and emotional impairments associated with schizophrenia raise questions about patients’ capacity to consent.

As is true in other areas of functional capacity, the ability of patients with schizophrenia to make competent decisions relates more to their overall cognitive functioning than to the presence or absence of specific symptoms of the disorder.7 Documentation of longitudinal consent-related abilities among research participants with schizophrenia in the long-term Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness study indicated that most participants had stable or improved consent-related abilities. Although almost 25% of participants experienced substantial worsening, only 4% fell below the study’s capacity threshold for enrollment.8

What I learned from Ms. V

A diagnosis of schizophrenia does not automatically render a person unable to make decisions about medical care. Even patients who have severe mental illness might have significant intact areas of reality testing. Ethically, it is important to at least consider that the chronically mentally ill can understand treatment options and express consistent choices.

Healthcare providers might tend to exclude psychiatric patients from end-of-life decisions because they (1) are worried about the emotional fragility of such patients and (2) assume that patients lack capacity to participate in making such important decisions. The case presented here is an example of a patient with a severe psychiatric diagnosis being able to participate in her care despite her mental state.

1. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(25):1635-1638.

2. Leo RJ. Competency and the capacity to make treatment decisions: a primer for primary care physicians. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;1(5):131-141.

3. White MM, Lofwall MR. Challenges of the capacity evaluation for the consultation-liaison psychiatrist. J Psychiatr Pract. 2015;21(2):160-170.

4. Ganzini L, Volicer L, Nelson W, et al. Pitfalls in assessment of decision-making capacity. Psychosomatics. 2003;44(3):237-243.

5. Ganzini L, Volicer L, Nelson WA, et al. Ten myths about decision-making capacity. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2005;6(3):S100-S104.

6. Jeste DV, Depp CA, Palmer BW. Magnitude of impairment in decisional capacity in people with schizophrenia compared to normal subjects: an overview. Schizophr Bull. 2005;32(1):121-128.

7. Appelbaum PS. Decisional capacity of patients with schizophrenia to consent to research: taking stock. Schizophr Bull. 2005;32(1):22-25.

8. Stroup TS, Appelbaum PS, Gu H, et al. Longitudinal consent-related abilities among research participants with schizophrenia: results from the CATIE study. Schizophr Res. 2011;130(1-3):47-52.

1. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(25):1635-1638.

2. Leo RJ. Competency and the capacity to make treatment decisions: a primer for primary care physicians. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;1(5):131-141.

3. White MM, Lofwall MR. Challenges of the capacity evaluation for the consultation-liaison psychiatrist. J Psychiatr Pract. 2015;21(2):160-170.

4. Ganzini L, Volicer L, Nelson W, et al. Pitfalls in assessment of decision-making capacity. Psychosomatics. 2003;44(3):237-243.

5. Ganzini L, Volicer L, Nelson WA, et al. Ten myths about decision-making capacity. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2005;6(3):S100-S104.

6. Jeste DV, Depp CA, Palmer BW. Magnitude of impairment in decisional capacity in people with schizophrenia compared to normal subjects: an overview. Schizophr Bull. 2005;32(1):121-128.

7. Appelbaum PS. Decisional capacity of patients with schizophrenia to consent to research: taking stock. Schizophr Bull. 2005;32(1):22-25.

8. Stroup TS, Appelbaum PS, Gu H, et al. Longitudinal consent-related abilities among research participants with schizophrenia: results from the CATIE study. Schizophr Res. 2011;130(1-3):47-52.

Intellectual disability impedes decision-making in organ transplantation

CASE REPORT Evaluation for renal transplant

Mr. B, age 21, who has a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder and an IQ comparable to that of a 4-year-old, is referred for evaluation of his candidacy for renal transplant.

A few months earlier, Mr. B pulled out his temporary dialysis catheter. Now, he receives hemodialysis through an arteriovenous fistula in the arm, but requires constant supervision during dialysis.

At evaluation, Mr. B is accompanied by his parents and his older sister, who have been providing day-to-day care for him. They appear fully committed to his well-being.

Mr. B does not have a living donor.

Needed: Assessment of adaptive functioning

DSM-5 defines intellectual disability as a disorder with onset during the developmental period. It includes deficits of intellectual and adaptive functioning in conceptual, social, and practical domains.

Regrettably, many authors focus exclusively on intellectual functioning and IQ, classifying patients as having intellectual disability based on intelligence tests alone.1,2 Adaptive capabilities are insufficiently taken into consideration; there is an urgent need to supplement IQ testing with neuropsychological testing of a patient’s cognitive and adaptive functioning.

Landmark case

In 1995, Sandra Jensen, age 34, with trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) was denied a heart and lung transplant at 2 prominent academic institutions. The denial created a national debate; Jensen’s advocates persuaded one of the hospitals to reconsider.3,4

In 1996, Jensen received the transplant, but she died 18 months later from complications of immunosuppressive therapy. Her surgery was a landmark event; previously, no patient with trisomy 21 or intellectual disability had undergone organ transplantation.

Although attitudes and practices have changed in the past 2 decades, intellectual disability is still considered a relative contraindication to certain organ transplants.5

Why is intellectual disability still a contraindication?

Allocation of transplant organs is based primarily on the ethical principle of utilitarianism: ie, a morally good action is one that helps the greatest number of people. “Benefit” might take the form of the number of lives saved or the number of years added to a patient’s life.

There is little consensus on the definition of quality of life, with its debatable ideological standpoint that stands, at times, in contrast to distributive justice. Studies have shown that the long-term outcome for patients with intellectual disability who received a kidney transplant is comparable to the outcome after renal transplant for patients who are not intellectually disabled. In other studies, patients with intellectual disability and their caregivers report improvement in quality of life after transplant.

The goal of successful transplantation is improvement in quality of life and an increase in longevity. Compliance with all aspects of post-transplant treatment is essential—which is why intellectual disability remains a relative contraindication to heart transplantation in the guidelines of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The society’s position is based on a theoretical rationale: ie, “concerns about compliance.”

Only 7 cases of successful long-term outcome after cardiac transplantation have been reported in patients with intellectual disability, and these were marked by the presence of the social and cognitive support necessary for post-transplant compliance with treatment.5 One of these 7 patients had a lengthy hospitalization 4 years after transplantation because of poor adherence to his medication regimen, following the functional decline of his primary caregiver.

Two-pronged evaluation is needed. Most patients undergoing organ transplantation receive a psychosocial assessment that varies from institution to institution. Intellectual disability can add complexity to the task of assessing candidacy for transplantation, however. In these patients, the availability and adequacy of caregivers is as important a part of decision-making as assessment of the patients themselves—yet studies of the assessment of caregivers are limited. The patient’s caregivers should be present during evaluation so that their knowledge, ability, and willingness to take on post-transplant responsibilities can be assessed. More research is needed on long-term outcomes of successful transplantation in patients with intellectual disability.

CASE CONTINUED Placement on hold

The transplant committee decides to postpone placing Mr. B on the transplant waiting list. Consensus is to revisit the question of placing him on the list at a later date.

What led to this decision?

The committee had several concerns about approving Mr. B for a transplant:

- His history of pulling out the catheter meant that he would require closer postoperative monitoring, because he would likely have drains and a urinary catheter inserted.

- Maintaining adequate oral hydration with a new kidney could be a challenge because Mr. B would not be able to comprehend how dehydration can destroy a new kidney.

- His parents believed that, after transplant, Mr. B would not be dependent on them; they failed to understand that he requires lifelong supervision to ensure compliance with immunosuppressive medications and return for follow-up.

The committee’s decision was aided by the rationale that dialysis is readily available and is a sustainable alternative to transplantation.

Mr. B’s case raises an ethical question

We speculate what the team’s decision about transplantation would have been if Mr. B (1) had a living donor or (2) was being considered for a heart, lung, or liver transplant—for which there is no analogous procedure to dialysis to sustain the patient.

1. Arciniegas DB, Filley CM. Implications of impaired cognition for organ transplant candidacy. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 1999;4(2):168-172.

2. Dobbels F. Intellectual disability in pediatric transplantation: pitfalls and opportunities. Pediatr Transplant. 2014;18(7):658-660.

3. Martens MA, Jones L, Reiss S. Organ transplantation, organ donation and mental retardation. Pediatr Transplant. 2006;10(6):658-664.

4. Panocchia N, Bossola M, Vivanti G. Transplantation and mental retardation: what is the meaning of a discrimination? Am J Transplant. 2010;10(4):727-730.

5. Samelson-Jones E, Mancini D, Shapiro PA. Cardiac transplantation in adult patients with mental retardation: do outcomes support consensus guidelines? Psychosomatics. 2012;53(2):133-138.

CASE REPORT Evaluation for renal transplant

Mr. B, age 21, who has a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder and an IQ comparable to that of a 4-year-old, is referred for evaluation of his candidacy for renal transplant.

A few months earlier, Mr. B pulled out his temporary dialysis catheter. Now, he receives hemodialysis through an arteriovenous fistula in the arm, but requires constant supervision during dialysis.

At evaluation, Mr. B is accompanied by his parents and his older sister, who have been providing day-to-day care for him. They appear fully committed to his well-being.

Mr. B does not have a living donor.

Needed: Assessment of adaptive functioning

DSM-5 defines intellectual disability as a disorder with onset during the developmental period. It includes deficits of intellectual and adaptive functioning in conceptual, social, and practical domains.

Regrettably, many authors focus exclusively on intellectual functioning and IQ, classifying patients as having intellectual disability based on intelligence tests alone.1,2 Adaptive capabilities are insufficiently taken into consideration; there is an urgent need to supplement IQ testing with neuropsychological testing of a patient’s cognitive and adaptive functioning.

Landmark case

In 1995, Sandra Jensen, age 34, with trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) was denied a heart and lung transplant at 2 prominent academic institutions. The denial created a national debate; Jensen’s advocates persuaded one of the hospitals to reconsider.3,4

In 1996, Jensen received the transplant, but she died 18 months later from complications of immunosuppressive therapy. Her surgery was a landmark event; previously, no patient with trisomy 21 or intellectual disability had undergone organ transplantation.

Although attitudes and practices have changed in the past 2 decades, intellectual disability is still considered a relative contraindication to certain organ transplants.5

Why is intellectual disability still a contraindication?

Allocation of transplant organs is based primarily on the ethical principle of utilitarianism: ie, a morally good action is one that helps the greatest number of people. “Benefit” might take the form of the number of lives saved or the number of years added to a patient’s life.

There is little consensus on the definition of quality of life, with its debatable ideological standpoint that stands, at times, in contrast to distributive justice. Studies have shown that the long-term outcome for patients with intellectual disability who received a kidney transplant is comparable to the outcome after renal transplant for patients who are not intellectually disabled. In other studies, patients with intellectual disability and their caregivers report improvement in quality of life after transplant.

The goal of successful transplantation is improvement in quality of life and an increase in longevity. Compliance with all aspects of post-transplant treatment is essential—which is why intellectual disability remains a relative contraindication to heart transplantation in the guidelines of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The society’s position is based on a theoretical rationale: ie, “concerns about compliance.”

Only 7 cases of successful long-term outcome after cardiac transplantation have been reported in patients with intellectual disability, and these were marked by the presence of the social and cognitive support necessary for post-transplant compliance with treatment.5 One of these 7 patients had a lengthy hospitalization 4 years after transplantation because of poor adherence to his medication regimen, following the functional decline of his primary caregiver.

Two-pronged evaluation is needed. Most patients undergoing organ transplantation receive a psychosocial assessment that varies from institution to institution. Intellectual disability can add complexity to the task of assessing candidacy for transplantation, however. In these patients, the availability and adequacy of caregivers is as important a part of decision-making as assessment of the patients themselves—yet studies of the assessment of caregivers are limited. The patient’s caregivers should be present during evaluation so that their knowledge, ability, and willingness to take on post-transplant responsibilities can be assessed. More research is needed on long-term outcomes of successful transplantation in patients with intellectual disability.

CASE CONTINUED Placement on hold

The transplant committee decides to postpone placing Mr. B on the transplant waiting list. Consensus is to revisit the question of placing him on the list at a later date.

What led to this decision?

The committee had several concerns about approving Mr. B for a transplant:

- His history of pulling out the catheter meant that he would require closer postoperative monitoring, because he would likely have drains and a urinary catheter inserted.

- Maintaining adequate oral hydration with a new kidney could be a challenge because Mr. B would not be able to comprehend how dehydration can destroy a new kidney.

- His parents believed that, after transplant, Mr. B would not be dependent on them; they failed to understand that he requires lifelong supervision to ensure compliance with immunosuppressive medications and return for follow-up.

The committee’s decision was aided by the rationale that dialysis is readily available and is a sustainable alternative to transplantation.

Mr. B’s case raises an ethical question

We speculate what the team’s decision about transplantation would have been if Mr. B (1) had a living donor or (2) was being considered for a heart, lung, or liver transplant—for which there is no analogous procedure to dialysis to sustain the patient.

CASE REPORT Evaluation for renal transplant

Mr. B, age 21, who has a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder and an IQ comparable to that of a 4-year-old, is referred for evaluation of his candidacy for renal transplant.

A few months earlier, Mr. B pulled out his temporary dialysis catheter. Now, he receives hemodialysis through an arteriovenous fistula in the arm, but requires constant supervision during dialysis.

At evaluation, Mr. B is accompanied by his parents and his older sister, who have been providing day-to-day care for him. They appear fully committed to his well-being.

Mr. B does not have a living donor.

Needed: Assessment of adaptive functioning

DSM-5 defines intellectual disability as a disorder with onset during the developmental period. It includes deficits of intellectual and adaptive functioning in conceptual, social, and practical domains.

Regrettably, many authors focus exclusively on intellectual functioning and IQ, classifying patients as having intellectual disability based on intelligence tests alone.1,2 Adaptive capabilities are insufficiently taken into consideration; there is an urgent need to supplement IQ testing with neuropsychological testing of a patient’s cognitive and adaptive functioning.

Landmark case

In 1995, Sandra Jensen, age 34, with trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) was denied a heart and lung transplant at 2 prominent academic institutions. The denial created a national debate; Jensen’s advocates persuaded one of the hospitals to reconsider.3,4

In 1996, Jensen received the transplant, but she died 18 months later from complications of immunosuppressive therapy. Her surgery was a landmark event; previously, no patient with trisomy 21 or intellectual disability had undergone organ transplantation.

Although attitudes and practices have changed in the past 2 decades, intellectual disability is still considered a relative contraindication to certain organ transplants.5

Why is intellectual disability still a contraindication?

Allocation of transplant organs is based primarily on the ethical principle of utilitarianism: ie, a morally good action is one that helps the greatest number of people. “Benefit” might take the form of the number of lives saved or the number of years added to a patient’s life.

There is little consensus on the definition of quality of life, with its debatable ideological standpoint that stands, at times, in contrast to distributive justice. Studies have shown that the long-term outcome for patients with intellectual disability who received a kidney transplant is comparable to the outcome after renal transplant for patients who are not intellectually disabled. In other studies, patients with intellectual disability and their caregivers report improvement in quality of life after transplant.

The goal of successful transplantation is improvement in quality of life and an increase in longevity. Compliance with all aspects of post-transplant treatment is essential—which is why intellectual disability remains a relative contraindication to heart transplantation in the guidelines of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The society’s position is based on a theoretical rationale: ie, “concerns about compliance.”

Only 7 cases of successful long-term outcome after cardiac transplantation have been reported in patients with intellectual disability, and these were marked by the presence of the social and cognitive support necessary for post-transplant compliance with treatment.5 One of these 7 patients had a lengthy hospitalization 4 years after transplantation because of poor adherence to his medication regimen, following the functional decline of his primary caregiver.

Two-pronged evaluation is needed. Most patients undergoing organ transplantation receive a psychosocial assessment that varies from institution to institution. Intellectual disability can add complexity to the task of assessing candidacy for transplantation, however. In these patients, the availability and adequacy of caregivers is as important a part of decision-making as assessment of the patients themselves—yet studies of the assessment of caregivers are limited. The patient’s caregivers should be present during evaluation so that their knowledge, ability, and willingness to take on post-transplant responsibilities can be assessed. More research is needed on long-term outcomes of successful transplantation in patients with intellectual disability.

CASE CONTINUED Placement on hold

The transplant committee decides to postpone placing Mr. B on the transplant waiting list. Consensus is to revisit the question of placing him on the list at a later date.

What led to this decision?

The committee had several concerns about approving Mr. B for a transplant:

- His history of pulling out the catheter meant that he would require closer postoperative monitoring, because he would likely have drains and a urinary catheter inserted.

- Maintaining adequate oral hydration with a new kidney could be a challenge because Mr. B would not be able to comprehend how dehydration can destroy a new kidney.

- His parents believed that, after transplant, Mr. B would not be dependent on them; they failed to understand that he requires lifelong supervision to ensure compliance with immunosuppressive medications and return for follow-up.

The committee’s decision was aided by the rationale that dialysis is readily available and is a sustainable alternative to transplantation.

Mr. B’s case raises an ethical question

We speculate what the team’s decision about transplantation would have been if Mr. B (1) had a living donor or (2) was being considered for a heart, lung, or liver transplant—for which there is no analogous procedure to dialysis to sustain the patient.

1. Arciniegas DB, Filley CM. Implications of impaired cognition for organ transplant candidacy. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 1999;4(2):168-172.

2. Dobbels F. Intellectual disability in pediatric transplantation: pitfalls and opportunities. Pediatr Transplant. 2014;18(7):658-660.

3. Martens MA, Jones L, Reiss S. Organ transplantation, organ donation and mental retardation. Pediatr Transplant. 2006;10(6):658-664.

4. Panocchia N, Bossola M, Vivanti G. Transplantation and mental retardation: what is the meaning of a discrimination? Am J Transplant. 2010;10(4):727-730.

5. Samelson-Jones E, Mancini D, Shapiro PA. Cardiac transplantation in adult patients with mental retardation: do outcomes support consensus guidelines? Psychosomatics. 2012;53(2):133-138.

1. Arciniegas DB, Filley CM. Implications of impaired cognition for organ transplant candidacy. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 1999;4(2):168-172.

2. Dobbels F. Intellectual disability in pediatric transplantation: pitfalls and opportunities. Pediatr Transplant. 2014;18(7):658-660.

3. Martens MA, Jones L, Reiss S. Organ transplantation, organ donation and mental retardation. Pediatr Transplant. 2006;10(6):658-664.

4. Panocchia N, Bossola M, Vivanti G. Transplantation and mental retardation: what is the meaning of a discrimination? Am J Transplant. 2010;10(4):727-730.

5. Samelson-Jones E, Mancini D, Shapiro PA. Cardiac transplantation in adult patients with mental retardation: do outcomes support consensus guidelines? Psychosomatics. 2012;53(2):133-138.

The view from my office: How psychiatry residency programs have changed

As I approach my twentieth year as Residency Program Coordinator in the Department of Psychiatry at Saint Louis University School of Medicine, I’ve been reflecting on the many changes that have occurred: within our residency program; in the requirements that all residency programs must meet to continue as an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)-accredited program; and in the overall scope of psychiatry residency training.

What has changed

During my time as Residency Program Coordinator, I have assisted 5 program directors and 3 associate program directors with day-to-day details of residency training. Our residency program has had couples, and a father and son; some residents even married each other while still in training.

The Electronic Residency Application System was not available until 2001; before that, applicants interested in being invited for an interview with a psychiatry residency program had to mail in their applications for review. This was a time-consuming, tedious process. In addition, residency programs today are required to use the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN) PreCERT credentialing program to verify training—instead of (as in the past) simply submitting a letter to ABPN that detailed the rotations and clinical skills examinations completed.

Residency programs have gone from evaluating residents by using the 6 competencies to the Milestones requirement from ACGME, which is the newest system of measuring residents’ competencies. Every month, the program faculty meets to discuss the progress of 1 of the classes of residents and the residents who are completing an individual self-assessment. Milestone scores for each resident are then reported to ACGME.

At one time, a resident’s files could be stored in a 2-inch binder; now, we need a 4-inch binder to accommodate required documentation! I am relieved—as, I am sure, many other residency program coordinators are—that residency programs are no longer required to prepare a Program Information Form but, instead, perform a self-study and, every 10 years, have a site visit. Last, every academic year, the Residency Program Coordinator is required to enter the incoming residents’ information into the graduate medical education track, ACGME, and PreCERT Web site systems.

Rewards of my position

As Residency Program Coordinator, I’ve had the rewarding experience of meeting physicians from all over the world without having to travel to other countries. Because I have a 3- or 4-year relationship with residents, I serve them in various roles: mentor, mother, confidante, motivator, and friend. As much as the job is rewarding, being the Residency Program Coordinator can, on some days, be overwhelming, particularly because I need to think “out of the box” to streamline decisions and thus avoid conflicts with program rotations and didactic schedules.

As I approach my twentieth year as Residency Program Coordinator in the Department of Psychiatry at Saint Louis University School of Medicine, I’ve been reflecting on the many changes that have occurred: within our residency program; in the requirements that all residency programs must meet to continue as an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)-accredited program; and in the overall scope of psychiatry residency training.

What has changed

During my time as Residency Program Coordinator, I have assisted 5 program directors and 3 associate program directors with day-to-day details of residency training. Our residency program has had couples, and a father and son; some residents even married each other while still in training.

The Electronic Residency Application System was not available until 2001; before that, applicants interested in being invited for an interview with a psychiatry residency program had to mail in their applications for review. This was a time-consuming, tedious process. In addition, residency programs today are required to use the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN) PreCERT credentialing program to verify training—instead of (as in the past) simply submitting a letter to ABPN that detailed the rotations and clinical skills examinations completed.

Residency programs have gone from evaluating residents by using the 6 competencies to the Milestones requirement from ACGME, which is the newest system of measuring residents’ competencies. Every month, the program faculty meets to discuss the progress of 1 of the classes of residents and the residents who are completing an individual self-assessment. Milestone scores for each resident are then reported to ACGME.

At one time, a resident’s files could be stored in a 2-inch binder; now, we need a 4-inch binder to accommodate required documentation! I am relieved—as, I am sure, many other residency program coordinators are—that residency programs are no longer required to prepare a Program Information Form but, instead, perform a self-study and, every 10 years, have a site visit. Last, every academic year, the Residency Program Coordinator is required to enter the incoming residents’ information into the graduate medical education track, ACGME, and PreCERT Web site systems.

Rewards of my position

As Residency Program Coordinator, I’ve had the rewarding experience of meeting physicians from all over the world without having to travel to other countries. Because I have a 3- or 4-year relationship with residents, I serve them in various roles: mentor, mother, confidante, motivator, and friend. As much as the job is rewarding, being the Residency Program Coordinator can, on some days, be overwhelming, particularly because I need to think “out of the box” to streamline decisions and thus avoid conflicts with program rotations and didactic schedules.

As I approach my twentieth year as Residency Program Coordinator in the Department of Psychiatry at Saint Louis University School of Medicine, I’ve been reflecting on the many changes that have occurred: within our residency program; in the requirements that all residency programs must meet to continue as an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)-accredited program; and in the overall scope of psychiatry residency training.

What has changed

During my time as Residency Program Coordinator, I have assisted 5 program directors and 3 associate program directors with day-to-day details of residency training. Our residency program has had couples, and a father and son; some residents even married each other while still in training.

The Electronic Residency Application System was not available until 2001; before that, applicants interested in being invited for an interview with a psychiatry residency program had to mail in their applications for review. This was a time-consuming, tedious process. In addition, residency programs today are required to use the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN) PreCERT credentialing program to verify training—instead of (as in the past) simply submitting a letter to ABPN that detailed the rotations and clinical skills examinations completed.

Residency programs have gone from evaluating residents by using the 6 competencies to the Milestones requirement from ACGME, which is the newest system of measuring residents’ competencies. Every month, the program faculty meets to discuss the progress of 1 of the classes of residents and the residents who are completing an individual self-assessment. Milestone scores for each resident are then reported to ACGME.

At one time, a resident’s files could be stored in a 2-inch binder; now, we need a 4-inch binder to accommodate required documentation! I am relieved—as, I am sure, many other residency program coordinators are—that residency programs are no longer required to prepare a Program Information Form but, instead, perform a self-study and, every 10 years, have a site visit. Last, every academic year, the Residency Program Coordinator is required to enter the incoming residents’ information into the graduate medical education track, ACGME, and PreCERT Web site systems.

Rewards of my position

As Residency Program Coordinator, I’ve had the rewarding experience of meeting physicians from all over the world without having to travel to other countries. Because I have a 3- or 4-year relationship with residents, I serve them in various roles: mentor, mother, confidante, motivator, and friend. As much as the job is rewarding, being the Residency Program Coordinator can, on some days, be overwhelming, particularly because I need to think “out of the box” to streamline decisions and thus avoid conflicts with program rotations and didactic schedules.

Changing trends in diet pill use, from weight loss agent to recreational drug

The prevalence of obesity and obesity-related conditions in the United States is increasing. Many weight-loss products and dietary supplements are used in an attempt to combat this epidemic, but little evidence exists of their efficacy and safety.

We present a case report of a middle-age woman who developed severe psychotic symptoms while taking phentermine hydrochloride (HCl), a psychostimulant similar to amphetamine that is used as a weight-loss agent and for recreational purposes. Phentermine has been associated with mood and psychotic symptoms and has a tendency to cause psychological dependence and tolerance.

To investigate the risks and potential effects of using this drug, we searched OVID and PubMed databases using the search string “phentermine + psychosis.” We conclude that there is a need for awareness about early detection and treatment of reversible psychotic and mood symptoms caused by what might appear to be harmless weight-loss and energy pills.

Obesity epidemic, wide-ranging weight-loss effortsThere has been a dramatic increase in obesity in the United States in the past 20 years: More than one-third of adults and approximately 17% of children and adolescents are obese. Obesity-related conditions, such as heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes mellitus, are leading causes of preventable death.1 Weight monitoring, a healthy lifestyle, surgical intervention, traditional herbs, and diet-pill supplements are some of the modalities used to address this epidemic.

Most so-called supplements for weight loss are exempt from FDA regulation. They do not undergo rigorous testing for safety. Furthermore, many contain controlled substances; some supplements are anti-seizure medications or other prescription drugs; and some are drugs not approved in the United States.2 Since the 1930s, such drugs as dinitrophenol, ephedrine, amphetamine, fenfluramine, and phentermine have flooded the market with the promise of quick weight loss.3,4

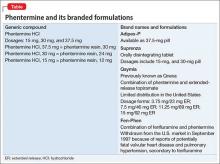

Phentermine, a contraction of “phenyltertiary-butylamine,” and its various types (Table) is a psychostimulant of the phenethylamine class, with a pharmacologic profile similar to that of amphetamine. It is known to yield false-positive immunoassay screening results for amphetamines.

CASE REPORT Acute psychotic break

Ms. B, age 37, with a history of postpartum depression, arrives at the emergency room reporting auditory hallucinations of her son and boyfriend; vivid visual hallucinations; and persecutory ideas toward her boyfriend, whom she believes had kidnapped her son. She also complains of insomnia and intermittent confusion for the past week.

Speech is pressured, fast, and difficult to comprehend at times; affect is labile and irritable. Ms. B denies suicidal ideation and is oriented to time, place, and person.

A urine drug screen is positive for amphetamine.

Pre-admission medications include alprazolam, 1 mg as needed, and zolpidem, 10 mg at bedtime, prescribed by Ms. B’s primary care physician for anxiety and insomnia. She discontinued these medications 3 weeks ago because of increased drowsiness at work. She denies other substance use and is unable to account for the positive urine drug screen.

Her medical history, physical examination, and a CT scan of the head are unremarkable. The components of a comprehensive metabolic panel and complete blood count are within normal limits.